Abstract

Background

Evidence regarding the efficacy of nutritional supplementation to enhance exercise training responses in COPD patients with low muscle mass is limited.

The objective was to study if nutritional supplementation targeting muscle derangements enhances outcome of exercise training in COPD patients with low muscle mass.

Methods

Eighty‐one COPD patients with low muscle mass, admitted to out‐patient pulmonary rehabilitation, randomly received oral nutritional supplementation, enriched with leucine, vitamin D, and omega‐3 fatty acids (NUTRITION) or PLACEBO as adjunct to 4 months supervised high intensity exercise training.

Results

The study population (51% males, aged 43–80) showed moderate airflow limitation, low diffusion capacity, normal protein intake, low plasma vitamin D, and docosahexaenoic acid. Intention‐to‐treat analysis revealed significant differences after 4 months favouring NUTRITION for body mass (mean difference ± SEM) (+1.5 ± 0.6 kg, P = 0.01), plasma vitamin D (+24%, P = 0.004), eicosapentaenoic acid (+91%,P < 0.001), docosahexaenoic acid (+31%, P < 0.001), and steps/day (+24%, P = 0.048). After 4 months, both groups improved skeletal muscle mass (+0.4 ± 0.1 kg, P < 0.001), quadriceps muscle strength (+12.3 ± 2.3 Nm,P < 0.001), and cycle endurance time (+191.4 ± 34.3 s, P < 0.001). Inspiratory muscle strength only improved in NUTRITION (+0.5 ± 0.1 kPa, P = 0.001) and steps/day declined in PLACEBO (−18%,P = 0.005).

Conclusions

High intensity exercise training is effective in improving lower limb muscle strength and exercise performance in COPD patients with low muscle mass and moderate airflow obstruction. Specific nutritional supplementation had additional effects on nutritional status, inspiratory muscle strength, and physical activity compared with placebo.

Keywords: Emphysema, Nutrient supplementation, Physical activity, Pulmonary rehabilitation, Muscle function

Introduction

It is well established that extra‐pulmonary pathology enhances the disease burden and mortality risk in patients with COPD. Muscle wasting is common, in particular in emphysema, and associated with a high prevalence of osteoporosis, impaired exercise performance, and higher mortality risk.1 Furthermore muscle wasting often coincides with a decreased oxidative metabolism due to a shift in muscle fibre type composition.2 Treatment of muscle dysfunction to alleviate progressive disability has been subject of intensive research in COPD. Exercise training is considered as cornerstone of pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) for improving lower limb muscle function.3 The latest Cochrane meta‐analysis by Ferreira et al. 4 concludes that nutritional supplementation promotes weight gain and fat‐free mass as proxy of muscle mass among patients with COPD, especially if undernourished and when combined with exercise training. However, the potential of nutritional supplementation to enhance efficacy of exercise training is not well established. Limited studies are available that differ in COPD target population and nutrient composition, and most of them are underpowered.5 In this randomized placebo‐controlled multi‐centre NUTRAIN‐trial, we aimed to determine the efficacy of specific nutritional supplementation targeting muscle derangements as adjunct to exercise training in COPD patients with low muscle mass. Based on available evidence regarding the mode of action of specific nutrients on skeletal muscle maintenance combined with reported deficiencies in COPD, we chose a multimodal approach including high quality protein enriched with leucine,6, 7 vitamin D,8 and omega‐3 (n‐3) poly‐unsaturated fatty acids (PUFA).9 We hypothesize that COPD patients with low muscle mass, eligible for out‐patient PR, show more pronounced improvement in muscle strength, endurance, and nutritional status after an exercise training program including targeted nutritional support.

Methods

A detailed methodology can be found in the Supporting Information.

Study design

This double blind placebo controlled multi‐centre NUTRAIN‐trial was integrated in the out‐patient PR program performed in seven hospitals of the Centre of Expertise for Chronic Organ failure (CIRO) network in the South East of the Netherlands. The study was registered at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT01344135) and the Medical Ethics Committee from Maastricht University Medical Centre granted ethical approval (NL34927068.10/MEC 11‐3‐004). The NUTRAIN‐trial also comprised an exploratory maintenance program with a wider scope which will be reported separately.

Patients

Patients with COPD (post‐bronchodilator FEV1/FVC <0.7) referred for PR between September 2011–April 2014 were eligible for participation when they had low muscle mass (defined as FFMI under the sex‐ and age‐specific 25th percentile FFMI values10), were admitted to out‐patient PR, did not meet any of the exclusion criteria (see Supporting Information), and gave written informed consent. The target sample size (alpha 0.05, power 80%) was based on data from the INTERCOM‐study11 assuming a 10% difference in peak torque between the groups assuming maintenance of skeletal muscle strength in PLACEBO during follow‐up and a SD of 5 Nm in peak torque, revealing n = 60 in each group including 25% drop‐out. Patient inclusion was prematurely discontinued because the test product could not be produced within the appropriate quality specifications due to discontinuation of the supply of one of the ingredients, but justifiable based on other RCTs published in the meantime as argued in the discussion.

To explore if the nutrient supplementation treated a deficient status or not, baseline plasma nutrient status was compared with a healthy control group (see Supporting Information for details).

Procedures

The nutritional intervention was integrated in a 4 month standardized outpatient PR program (see Supporting Information for PR components). Patients from both the PLACEBO and NUTRITION group were advised to consume two to three portions of the supplement daily. Randomization and masking procedures are described in the Supporting Information. Per volume serving of 125 mL unit, the NUTRITION product provided 187.5 kCal in a distribution of 20 energy percent (EN%) protein, 60EN% carbohydrate (CHO), and 20EN% fat, and was enriched with leucine, n‐3 PUFA, and vitamin D (Nutricia NV, Zoetermeer, the Netherlands, for details see table E1). The PLACEBO product did not comprise the investigated active components but consisted of a flavoured non‐caloric aqueous solution.

Outcomes

Measurements were performed at CIRO before entering PR, as part of a 3 day baseline assessment and after completion of the PR during a 2 day outcome assessment3 with quadriceps muscle strength (QMS) as primary outcome. Secondary outcomes included body composition measured by dual energy X‐ray absorptiometry (DEXA), cycle endurance time (CET), inspiratory muscle strength (IMS), and daily steps by a tri‐axial GT3X Actigraph accelerometer (Health One Technology, Fort Walton Beach, FL) worn on an elastic belt firmly attached around the waist for 7 consecutive days before and after the intervention period, habitual dietary intake using a validated cross‐check dietary history method and fasting plasma levels of vitamin D (25‐hydroxycholecalciferol), branched‐chain amino acids (BCAAs), and fatty acid profile in phospholipids. Furthermore, post‐bronchodilator forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1), forced vital capacity (FVC), static lung volumes, and diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO) were assessed. Exploratory outcomes included 6 min walk distance (6MWD) and mood assessment (HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression scale).

Statistical analyses

Intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS version 20.0 for Windows, Inc.), using all available change‐values (every subject completing the PR and outcome assessment), independently of dropping out of the nutritional intervention. Within group treatment outcomes were compared by paired samples T‐test for continuous normally distributed data or Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test for continuous non‐normally distributed data. Between‐group differences were compared by ANCOVA taking pre‐treatment value as covariate, the 4 month post‐treatment value as response, and considering treatment as a factor.12 Two‐sided P‐values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Results are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM).

Results

Patients

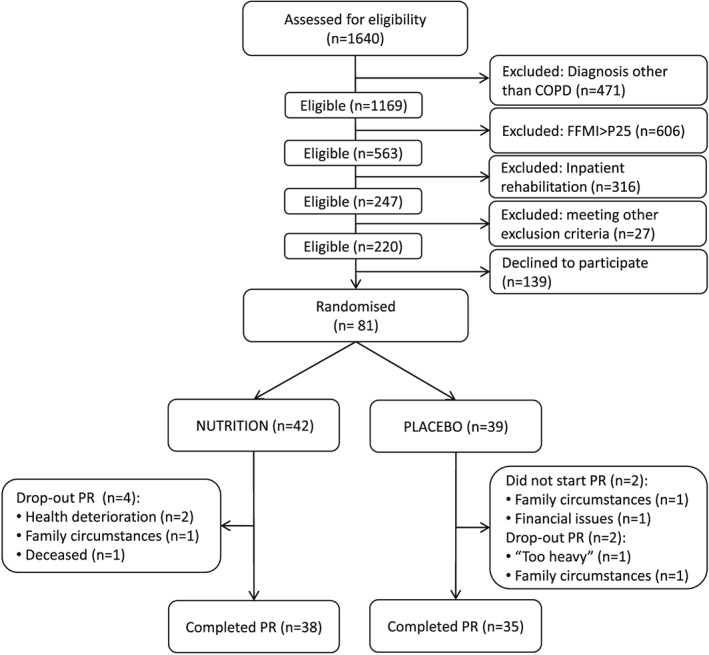

Between September 2011 and April 2014, 81 patients were enrolled in the trial and randomized to NUTRITION or PLACEBO. A patient flowchart is shown in (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

NUTRAIN flowchart. A total of 1640 patients referred for pulmonary rehabilitation were assessed for trial eligibility. COPD patients (post‐bronchodilator FEV1/FVC <0.7) were eligible when they had low muscle mass (FFMI < sex‐ and age‐specific 25th percentile FFMI values) and referred for outpatient rehabilitation. A total of 1420 patients were excluded and 139 eligible patients declined to participate; 81 patients were enrolled in the trial and randomized to NUTRITION or PLACEBO. Two of the 81 randomized patients did not start the treatment. During the PR, the drop‐out rate was 9.5% (4 patients) in NUTRITION and 5.4% (2 patients) in PLACEBO.

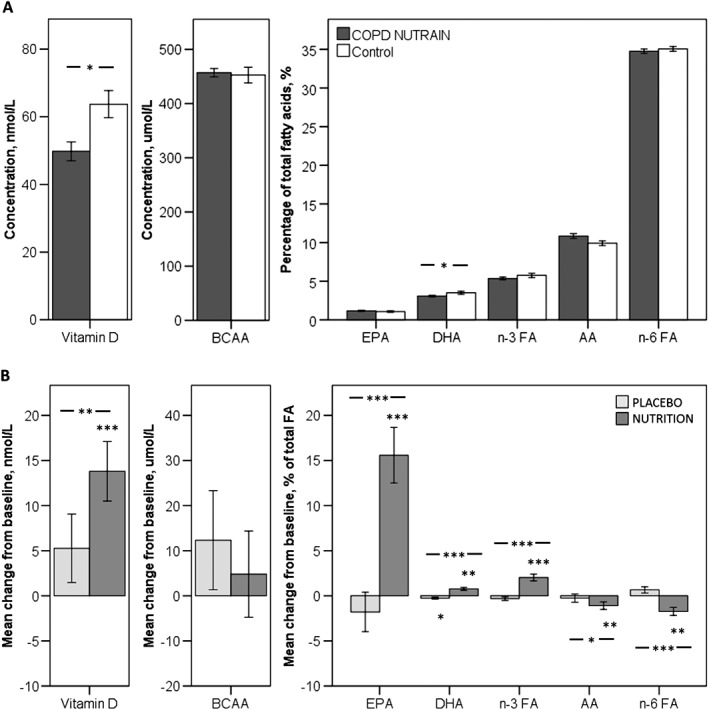

At baseline, the study population (51% male, aged 43–80) were characterized by low diffusion capacity (DLCO: 49.4 ± 1.7%), on average moderate airflow limitation (FEV1: 55.1 ± 2.2%predicted), a BMI of 22.7 ± 0.3 kg/m2, and fat‐free mass index (FFMI) of 15.8 ± 0.2 kg/m2. The majority of the patients (88.8%) had vitamin D insufficiency/deficiency, and average plasma DHA level was decreased compared with controls (−12.4%), but the plasma level of total BCAA was comparable with healthy age matched volunteers (Figure 2a). Mean protein intake was well above recommended daily intake (RDI) (1.4 ± 0.1 g/kg BW), whereas intake of vitamin D and calcium were below RDI in, respectively, 92.4 and 72.2% of the participants. Although baseline CET and 6MWD tended to be higher in NUTRITION, no significant differences in baseline characteristics were found between the NUTRITION and PLACEBO group (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Plasma status of supplemented nutrients. A: Baseline plasma nutrient levels compared with healthy controls. Dark grey bars represent NUTRAIN patients with COPD. White bars represent healthy controls. B: Mean change from baseline in plasma concentrations of supplemented nutrients. Light grey bars represent patients that received PLACEBO. Mid grey bars represent patients that received NUTRITION. * P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the randomized study population

| PLACEBO (n = 39) | NUTRITION (n = 42) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean ± SEM | N | Mean ± SEM | ||

| General | Gender, % male | 59.0% | 42.9% | ||

| Current smokers, % | 31.6% | 19.0% | |||

| Age, years | 39 | 62.2 ± 1.3 | 42 | 62.8 ± 1.3 | |

| Self‐reported co‐morbidities, n | 39 | 2.5 ± 0.3 | 42 | 2.5 ± 0.2 | |

| Exacerbations in last 12 months, n | 39 | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 42 | 1.1 ± 0.2 | |

| Lung function | DLCO, %predicted | 36 | 47.1 ± 2.5 | 42 | 51.4 ± 2.2 |

| FEV1, %predicted | 39 | 53.0 ± 2.8 | 42 | 57.0 ± 3.3 | |

| FVC, %predicted | 39 | 100.6 ± 2.7 | 42 | 102.8 ± 2.9 | |

| FEV1/FVC, % | 39 | 41.6 ± 1.8 | 42 | 44.4 ± 2.0 | |

| FRC, %predicted | 36 | 146.7 ± 5.9 | 42 | 139.1 ± 4.3 | |

| Residual volume, %predicted | 36 | 153.1 ± 8.5 | 42 | 143.4 ± 6.3 | |

|

Plasma nutrient

levels |

BCAA, μmol/L | 39 | 466.6 ± 10.9 | 41 | 448.0 ± 10.8 |

| Vitamin D, nmol/L | 39 | 45.3 ± 3.1 | 41 | 54.0 ± 4.5 | |

| Vitamin D insufficiency, % | 23.1% | 39.0% | |||

| Vitamin D deficiency, % | 69.2% | 46.3% | |||

| AA, % of total FA | 37 | 11.3 ± 0.4 | 36 | 10.4 ± 0.4 | |

| EPA, % of total FA | 37 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 36 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | |

| DHA, % of total FA | 37 | 3.2 ± 0.2 | 36 | 2.9 ± 0.2 | |

| N‐3 FA, % of total FA | 37 | 5.5 ± 0.3 | 36 | 5.2 ± 0.2 | |

| N‐6 FA, % of total FA | 37 | 34.8 ± 0.4 | 36 | 34.7 ± 0.4 | |

| Body composition | Total body mass, kg | 39 | 65.0 ± 1.7 | 42 | 64.3 ± 1.6 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 39 | 22.6 ± 0.5 | 42 | 22.9 ± 0.4 | |

| FM, kg | 39 | 19.0 ± 1.3 | 42 | 20.0 ± 1.0 | |

| Lean mass, kg | 39 | 43.6 ± 1.2 | 42 | 42.0 ± 1.3 | |

| SMM, kg | 39 | 18.4 ± 0.6 | 42 | 17.4 ± 0.6 | |

| BMC, g | 39 | 2414.7 ± 82.3 | 42 | 2331.3 ± 73.0 | |

| Dietary intake | Total energy, kcal/day | 39 | 2361.7 ± 161.3 | 40 | 2188.8 ± 111.4 |

| Protein, g/kg BW/day | 39 | 1.4 ± 0.1 | 40 | 1.4 ± 0.1 | |

| Protein <1.0 g/kg BW/day | 25.6% | 25.0% | |||

| Vitamin D, μg/day | 39 | 5.1 ± 0.5 | 40 | 5.7 ± 0.5 | |

| Vitamin D < RDI, % | 89.7% | 95.0% | |||

| Calcium, mg/day | 39 | 947.8 ± 62.4 | 40 | 998.1 ± 56.9 | |

| Calcium <RDI, % | 74.4% | 70.0% | |||

| Lower limb muscle strength | QMS, Nm | 37 | 118.0 ± 6.6 | 39 | 121.5 ± 6.4 |

| Exercise performance | Peak workload, Wmax | 39 | 72.5 ± 3.8 | 42 | 84.6 ± 5.2 |

| Peak workload, %predicted | 39 | 57.0 ± 3.4 | 42 | 69.5 ± 3.3** | |

| CET, s | 37 | 231.5 ± 12.0 | 41 | 319.0 ± 35.2 | |

| 6MWD, m | 39 | 484.30 ± 13.0 | 42 | 501.4 ± 13.1 | |

| 6MWD, %predicted | 39 | 72.1 ± 1.8 | 42 | 77.2 ± 1.7* | |

| Respiratory muscle strength | IMS, kPa | 38 | 7.0 ± 0.3 | 42 | 6.8 ± 0.4 |

| IMS, %predicted | 38 | 77.3 ± 2.7 | 42 | 79.4 ± 3.8 | |

| Physical activity level | PAL, steps/day | 37 | 4516.6 ± 379.3 | 38 | 4716.7 ± 327.2 |

Data are mean ± SEM or %. BCAA, branched‐chain amino acids; AA, arachidonic acid; EPA, eicosapentaenoic acid; DHA, docosahexaenoic acid; n‐3 FA, omega 3 fatty acids; n‐6 FA, omega 6 fatty acids; BMC, bone mineral content; SMM, skeletal muscle mass; FM, fat mass; QMS, quadriceps muscle strength; CET, cycle endurance time; 6MWD, 6 minwalking distance; IMS, inspiratory muscle strength; PAL, physical activity level.

P < 0.05.

P < 0.01.

Two of the 81 randomized patients did not start the treatment. During the PR, the drop‐out rate was 9.5% (four patients) in NUTRITION and 5.4% (two patients) in PLACEBO. Mean supplement intake reached 2.1 ± 0.1 portions/day. Reported side‐effects included stomach‐ache (n = 3 in NUTRITION, n = 1 in PLACEBO), constipation (n = 2 in NUTRITION), and undesirable weight loss (n = 5 in PLACEBO). Nonetheless, neutral or positive product rating was revealed in the majority of patients regarding taste, sweetness, mouthfeel, and thickness of the NUTRITION and PLACEBO supplement. The aftertaste of the NUTRITION supplement was equally rated pleasant or unpleasant. A high satiety after consuming the supplement was reported by ±70% in NUTRITION vs. ±17% in PLACEBO (P < 0.001). Outcomes of the intervention are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Outcomes of the intervention

| PLACEBO (n = 35) | NUTRITION (n = 38) |

Between group differences (NUTRITION − PLACEBO) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | |||

| Mean ± SEM | Mean ± SEM | Mean ± SEM | Mean ± SEM | Adj. difference ± SEM a | ||

| Plasma nutrient levels | BCAA, μmol/L | 471.6 ± 11.6 | 483.9 ± 15.5 | 445.3 ± 11.6 | 450.1 ± 10.3 | −14.4 ± 14.2 |

| Vitamin D, nmol/L | 44.6 ± 3.3 | 49.9 ± 4.0 | 54.2 ± 4.9 | 68.0 ± 3.6*** | 12.8 ± 4.3** | |

| AA, % of total FA | 11.3 ± 0.4 | 11.0 ± 0.5 | 10.6 ± 0.5 | 9.5 ± 0.3* | −1.2 ± 0.5* | |

| EPA, % of total FA | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 2.1 ± 0.2*** | 1.0 ± 0.2*** | |

| DHA, % of total FA | 3.2 ± 0.2 | 2.9 ± 0.1* | 3.0 ± 0.2 | 3.8 ± 0.1*** | 0.9 ± 0.2*** | |

| N‐3 FA, % of total FA | 5.5 ± 0.3 | 5.2 ± 0.2 | 5.3 ± 0.3 | 7.3 ± 0.3*** | 2.2 ± 0.4*** | |

| N‐6 FA, % of total FA | 34.8 ± 0.4 | 35.5 ± 0.4 | 35.1 ± 0.3 | 33.4 ± 0.5*** | −2.2 ± 0.5*** | |

| Body composition | Total body mass, kg | 65.7 ± 1.7 | 66.0 ± 1.7 | 63.8 ± 1.7 | 65.7 ± 1.7*** | 1.5 ± 0.6* |

| BMC, g | 2427.2 ± 85.9 | 2428.5 ± 84.1 | 2326.7 ± 78.7 | 2339.2 ± 80.3 | 10.0 ± 17.7 | |

| SMM, kg | 18.5 ± 0.6 | 18.8 ± 0.6** | 17.2 ± 0.6 | 17.8 ± 0.7** | 0.3 ± 0.2 | |

| FM, kg | 19.4 ± 1.4 | 19.2 ± 1.4 | 19.8 ± 1.1 | 21.0 ± 1.1*** | 1.6 ± 0.5** | |

| Lower limb muscle function | QMS, Nm | 121.2 ± 6.9 | 132.0 ± 7.2** | 121.7 ± 6.9 | 135.3 ± 8.2*** | 2.8 ± 4.6 |

| Exercise performance | CET, s | 237.9 ± 12.3 | 482.4 ± 62.5*** | 323.2 ± 38.8 | 467.2 ± 54.7*** | −109.7 ± 70.4 |

| 6MWD, m | 492.5 ± 14.0 | 492.0 ± 16.6 | 504.0 ± 14.5 | 500.3 17.9 | −3.9 ± 12.2 | |

| Respiratory muscle function | IMS, kPa | 7.1 ± 0.3 | 7.5 ± 0.3 | 6.7 ± 0.4 | 7.2 ± 0.4** | 0.0 ± 0.3 |

| Physical activity level | PAL, steps/day | 4664.7 ± 415.9 | 3841.9 ± 393.4** | 4790.1 ± 352.2 | 4866.4 ± 479.0 | 929.5 ± 459.2* |

| Mood | HADS total score | 11.1 ± 1.2 | 8.5 ± 0.9** | 12.2 ± 1.0 | 9.2 ± 1.1*** | −0.2 ± 1.0 |

| HADS anxiety score | 6.0 ± 0.7 | 4.1 ± 0.5** | 6.3 ± 0.7 | 4.8 ± 0.6*** | 0.4 ± 0.6 | |

| HADS depression score | 5.1 ± 0.6 | 4.4 ± 0.5 | 5.9 ± 0.5 | 4.4 ± 0.6** | −0.5 ± 0.6 | |

Data are mean ± SEM or %. BCAA, branched‐chain amino acids; AA, arachidonic acid; EPA, eicosapentaenoic acid; DHA, docosahexaenoic acid; n‐3 FA, omega 3 fatty acids; n‐6 FA, omega 6 fatty acids; BMC, bone mineral content; SMM, skeletal muscle mass; FM, fat mass; QMS, quadriceps muscle strength; CET, cycle endurance time; 6MWD, 6 min walking distance; IMS, inspiratory muscle strength; PAL, physical activity level; HADS, Hospital anxiety and depression scale.

P < 0.05.

P < 0.01.

P < 0.001.

Between‐group differences were compared by ANCOVA (taking pre‐treatment value as covariate, the 4 month post‐treatment value as response, and considering treatment as a factor in the statistical model).

Outcome assessment

Change in plasma status of supplemented nutrients is shown in Figure 2B. Compared with baseline, plasma levels of vitamin D, EPA, DHA, and total n‐3 FA significantly increased in NUTRITION (respectively, +26%, P < 0.001; +91%, P < 0.001; +27%, P = 0.001; and +38%, P < 0.001), while AA and total n‐6 FA significantly decreased (−10%, P = 0.012 and −5%, P < 0.001). In PLACEBO, DHA significantly decreased (−9%, P = 0.030), resulting in significant between‐group difference in favour of NUTRITION in plasma vitamin D (+24%, P = 0.004), EPA (+91%, P < 0.001), DHA (+31%, P < 0.001), and n‐3 FA (+42%, P < 0.001). Arachidonic acid and n‐6 FA were significantly lower in NUTRITION than PLACEBO (−1.2 ± 0.5 (−11%), P = 0.019; and −6%, P < 0.001). No differences were found in plasma BCAAs.

Body composition results showed significantly increased body mass, skeletal muscle mass (SMM,) and FM in NUTRITION compared with baseline (Table 2). Also in PLACEBO, SMM increased significantly. After PR, NUTRITION showed significantly higher body mass and FM than PLACEBO. No between‐group differences were found in SMM.

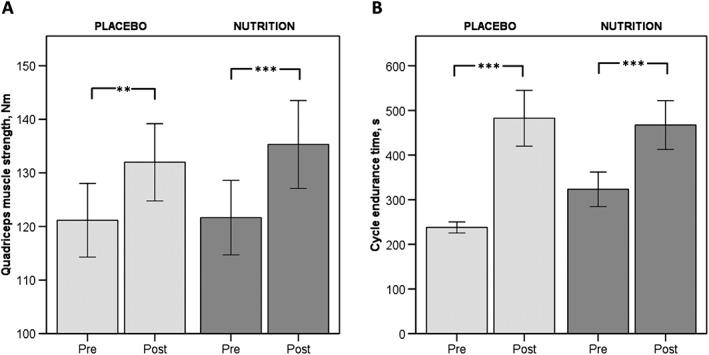

Assessment of lower limb muscle strength and exercise performance showed comparable improvements in quadriceps muscle strength and CET after PR (Figure 3). No differences were found in 6MWD within or between groups (Table 2).

Figure 3.

Mean pre‐ and post‐ values of A: Lower limb muscle strength; B: Exercise performance. Light grey bars represent patients that received PLACEBO. Mid grey bars represent patients that received NUTRITION. * P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001.

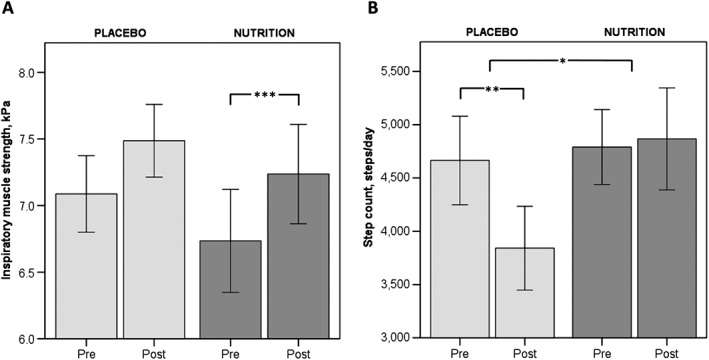

Inspiratory muscle strength improved significantly only in NUTRITION (Figure 4). After PR, daily steps decreased significantly in PLACEBO by 822.8 ± 283.8 steps/day (−18%; P = 0.005) but remained stable in NUTRITION (76.4 ± 385.1 steps/day, P = 0.767). This resulted in a significant between‐group difference in favour of NUTRITION. Assessment of mood showed significantly improved HADS depression score in NUTRITION but not in PLACEBO (Table 2).

Figure 4.

Mean pre‐ and post‐ values of A: Respiratory muscle strength; B: Physical activity level. Light grey bars represent patients that received PLACEBO. Mid grey bars represent patients that received NUTRITION. * P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

Discussion

The NUTRAIN‐trial showed that COPD patients with low muscle mass and moderate airflow obstruction respond well to high intensity exercise training. In this population, no additional effect of nutritional intervention was shown on lower limb muscle strength as primary outcome measure, but respiratory muscle strength (which was not a training target) improved in NUTRITION only. Between‐group differences favouring NUTRITION were shown in body weight, plasma nutrient status, and physical activity.

Earlier research on nutritional rehabilitation has mainly focused on providing enough energy and protein to improve or maintain body weight and muscle mass. Recent research has shifted towards the quality of dietary protein in terms of protein sources and supplementation of specific anabolic amino acids. Casein and whey, both high‐quality proteins because of their high essential amino acid (EAA) content, are shown to comparably and efficiently stimulate muscle protein synthesis.13 Leucine is one of the BCAAs known to increase insulin secretion and influence molecular regulation of muscle protein synthesis (via the mTOR pathway), thereby stimulating anabolism and muscle protein synthesis, provided sufficient supply of essential amino acids (EAA) to the muscles.6 The current supplement therefore provided equal amounts of casein and whey (4.2 g) for a balanced amino acid profile, enriched with 1.8 g leucine per serving volume of 125 mL. Skeletal muscle mass increased after exercise training, but this response was not augmented by protein supplementation. Possibly, protein supplementation is mainly effective in subjects with a deficient state of protein. Indeed, patients with advanced COPD and muscle wasting are reported to have low plasma levels of BCAAs (especially leucine) compared with age‐matched controls,7, 14 which could reflect a deficient state in muscle,7 but no evidence for a deficient BCAA state was found in our NUTRAIN patients with less advanced COPD. In a sample of 88 patients with severe COPD (GOLD 3–4) and BMI <23 kg/m2 not receiving exercise training, 12 weeks of supplementation with an EAA (4 g/day) mixture high in leucine led to higher FFM and muscle strength compared with an isocaloric placebo.15 Nonetheless, these patients were characterized by lower protein intake at baseline (1.0 ± 0.2 g/kg) than the current study population (1.4 ± 0.1 g/kg BW). Constantin et al. 16 randomly allocated 59 COPD patients (FEV1: 46.9 ± 17.8%predicted) to receive 19 g protein and 49 g carbohydrate or placebo supplements during 8 weeks of resistance training. They found a strong response to the training component (lean mass and strength gain), but nutritional supplementation did not augment functional responses to resistance training. In line, we found a strong response to the exercise training in the present trial, reflected as significantly increased muscle mass, lower limb muscle strength, and CET in both groups. All in all, it might be concluded that the augmenting value of protein fortification on skeletal muscle mass and quadriceps muscle strength is minimal in COPD with less advanced airflow obstruction when habitual protein intake is already adequate. Moreover, previous literature has suggested that further improvements on top of the effects of exercise training via ‘add‐on’ modalities may be challenging to obtain. Particularly, muscle composition and function may have realistic ceilings in terms of the magnitude of expected improvement within a short time period.17

So‐called pharmaco‐nutrients have recently been proposed to enhance efficacy of nutritional supplementation on physical performance by targeting muscle metabolism.5 Poly‐unsaturated fatty acids are the natural ligands of peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptors (PPARs) and PPAR‐gamma coactivator (PGC)‐1α, which are involved in regulation of skeletal muscle morphology and oxidative metabolism. A decreased expression of these regulators is reported in the skeletal muscle of advanced COPD patients compared with healthy controls.18 Broekhuizen et al. 9 demonstrated that PUFA modulation during an 8 week inpatient rehabilitation program was able to improve exercise capacity (peak workload and CET) to a larger extent than placebo in patients with severe COPD independent of lower limb muscle mass and strength. In the current NUTRAIN‐trial peak workload was not assessed post‐PR, but no group differences were found in CET. However, a comparison between studies is limited because of differences in CET protocol. Furthermore, the population by Broekhuizen et al. consisted of patients with more advanced disease (FEV1 37.3 ± 13.8%predicted) and with severe exercise impairment (41.3 ± 19.3%predicted).

The majority of the NUTRAIN patients were vitamin D insufficient/deficient (88.8%) providing a clear rationale for supplementation. In line with our study, a published post‐hoc subgroup analysis of 50 patients with COPD and vitamin D deficiency following a 3 month outpatient PR,19 reported a similar dissociation between improvements in peripheral and respiratory muscle strength after vitamin D supplementation. Patients receiving a monthly dose of 100.000 IU vitamin D had significantly larger improvements in inspiratory muscle strength and peak exercise tolerance, but not in quadriceps strength and 6 min walking distance (6MWD) compared with placebo. Median 25‐hydroxycholecalciferol level increased from 15 ng/mL (37.4 nmol/L) to 51 ng/mL (127.3 nmol/L), which exceeded the increase observed in the NUTRAIN trial (+25%), presumably by the 5–6 times higher administered dose. As respiratory muscle training was not part of the PR program in both trials, this might suggest a differential response of respiratory muscle following vitamin D and/or n‐3 fatty acids supplemented nutrients than peripheral muscle possibly related to maintenance of muscle oxidative phenotype in respiratory muscles.20

Exercise training significantly increased quadriceps muscle strength and CET in both groups. Cycle endurance time tended to increase to a smaller extent after supplementation, presumably because of a trend towards higher baseline value compared with the placebo group. Still, the increase in CET exceeded the proposed minimal clinically important difference of 100–105 s.21 No changes were observed in 6MWD in the current study, but average 6MWD did not seem rigorously impaired at baseline (almost 500 m) and also in the INTERCOM trial, investigating a comparable group of COPD patients with less advanced disease, 6MWD maintained similar in the intervention group but deteriorated in muscle wasted patients receiving usual care.11 That was also the reason why 6MWD was only included as exploratory outcome in this trial.

Recently, a more active lifestyle, reflected by objective assessment via accelerometry, has been proposed as novel and clinically important outcome measure of PR. According to the sparse literature available, the effects of current PR programs in terms of physical activity level are heterogeneous, which could be related to differences in studied population, type, and intensity of the exercise training and incorporation of other interventions like nutritional or psychological interventions.22 The exercise training part of the NUTRAIN trial primarily focused on high intensity resistance and endurance exercises, but no standardized behavioural change intervention for physical activity was incorporated. Despite concomitant increase in exercise capacity, the number of steps/day decreased in the placebo group, indicating a compensatory response to recover from the intensive exercise training sessions in daily physical activity. The observed dissociation between physical performance and daily physical activity has previously been reported in studies evaluating the effect of PR on daily physical activity22 and suggests that changing physical activity behaviour requires a more comprehensive approach than only targeting exercise capacity.23 In contrast to the placebo group, no adaptive decrease in daily steps was shown by patients receiving nutritional supplementation. This could be related to specific nutrient effects on lower limb muscle metabolism resulting in decreased muscle fatigue or via the observed improvement in respiratory muscle function. Dal Negro et al. 15 reported increased number of steps after EAA supplementation in domiciliary severe COPD patients. Alternatively, a positive effect of n‐3 fatty acid enriched protein‐dense supplements could be implicated as in cachectic patients with pancreatic cancer n‐3 FA supplementation also increased physical activity level assessed by doubly labelled water independent of muscle mass.24 Next to exercise, n‐3 FA additionally stimulate the PGC‐1α‐PPARα/δ pathway in muscle resulting not only in enhanced muscle (fat) oxidative metabolism25 and decreased muscle fatigue, but also in enhanced conversion of peripheral kynurenine into kynurenic acid, which is unable to cross the blood–brain barrier.26 Reducing plasma kynurenine protects the brain by mediating resilience to stress induced depression. Some evidence for this hypothesis was provided in this trial by the HADS depression score, which improved significantly in NUTRITION but not in PLACEBO. Based on previous research, nutritional supplementation consisted of two to three portions of 125 mL/day, which in the current trial proved to be the maximal feasible dosage. Intention‐to‐treat analysis revealed an average supplement intake of 2.1 portions/day, accompanied by significantly increased percentages of EPA and DHA, which are suggested to be useful blood biomarkers for determining adherence in clinical studies because of the linear response to its intakes.27 No changes were found in habitual dietary intake after PR (table E2), suggesting that patients in the NUTRITION group did not compensate for NS. Patients in the placebo group also did not compensate by increasing their energy intake for increased energy costs caused by the intensive exercise training, possibly implying that energy costs were compensated during the remainder of the day by an adaptive decreased number of daily steps. While the increase in FM resulting from extra caloric support may be protective in COPD patients prone to weight loss, it could be argued that attention should shift from macro‐ to targeted nutrient supplementation in weight stable COPD patients with low muscle mass. This may likely also improve compliance to nutritional support in some patients.

Based on the primary outcome measure the study was negative. There may have been a difference in muscle strength between the groups that was not detected as the study is potentially underpowered. It could also be argued that the studied population was too fit, because they had a moderate level of airflow obstruction, a mean 6MWD around 500 m, and a well above recommended daily protein intake. The criterion applied for muscle wasting (FFMI‐P25) was broader than defined by the ERS statement on nutritional assessment and therapy in COPD1 but derived from the IRAD‐2 trial. This trial showed favourable effects of 3 months of home rehabilitation combining health education, oral nutritional supplements, exercise and oral testosterone on body composition and exercise tolerance compared with usual care in muscle wasted patient with chronic respiratory failure.28 Nevertheless, to explore potential deviating intervention responses following the applied criteria for muscle wasting, we performed a post‐hoc subgroup analysis in which we compared outcomes between n = 44 patients with a FFMI < 10th percentile values (according to the ERS statement) and n = 37 a FFMI 10th–25th percentile values. ANCOVA did not show differences in any of the outcomes between the groups. Although the NUTRAIN trial did not reach the targeted sample size (n = 120) and was not designed to disentangle the mechanism behind the observed dissociation between physical performance and daily physical activity, it does provide new interesting leads for further research regarding the potential of nutritional modulation in COPD beyond skeletal muscle maintenance. Furthermore, adequate clinical trials in COPD are needed to explore nutritional strategies for maintaining the effects of exercise training after a pulmonary rehabilitation program. Data of the exploratory maintenance program of the NUTRAIN trial will be reported separately.

In conclusion, this RCT shows that exercise training is successful in improving lower limb muscle strength and cycle exercise performance in COPD patients with low muscle mass, moderate airflow obstruction, and a sufficient protein intake. Additional specific nutritional supplementation had beneficial effects on nutritional status and inspiratory muscle strength and positively influenced physical activity.

Author contributions

Each author has made substantial contributions to the current study. The contribution of the authors to the manuscript is as follows: CvdB: acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data, drafting the manuscript. ER, AvH, FF, EW: design of the study, interpretation of data, revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. AS: design of the study, interpretation of data, drafting and revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. All authors gave final approval of the version submitted for publication and take accountability for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work were appropriately investigated and resolved.

Conflict of interest

E.R., F.F., and E.W. declare that they have no conflict of interest regarding the present manuscript. A.vH. is employed by Nutricia Research. C.vdB. and A.S. report grants from Netherlands Lung Foundation and Nutricia Research, during the conduct of the study. A.S. is a member of International Scientific Advisory Board of Nutricia Advanced Medical Nutrition.

Supporting information

Data S1. Table E1: Nutrient composition of NUTRITION and PLACEBO products per 125 mL serving.

Table E2: Habitual dietary intake.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the participating patients as well as the team of treatment officers of the CIRO network who carefully delivered the intervention to the participating patients. The authors certify that they comply with the ethical guidelines for authorship and publishing of the Journal of Cachexia, Sarcopenia, and Muscle: update 2015.29

This study was financially supported by a Public–Private Consortium of Maastricht University/NUTRIM, CIRO+ BV Horn, Lung Foundation Netherlands (grant 3.4.09.003), and Nutricia Research.

van de Bool, C. , Rutten, E. P. A. , van Helvoort, A. , Franssen, F. M. E. , Wouters, E. F. M. , and Schols, A. M. W. J. (2017) A randomized clinical trial investigating the efficacy of targeted nutrition as adjunct to exercise training in COPD. Journal of Cachexia, Sarcopenia and Muscle, 8: 748–758. doi: 10.1002/jcsm.12219.

References

- 1. Schols AM, Ferreira IM, Franssen FM, Gosker HR, Janssens W, Muscaritoli M, et al. Nutritional assessment and therapy in COPD: a European Respiratory Society statement. Eur Respir J 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. van de Bool C, Gosker HR, van den Borst B, Op den Kamp CM, Slot IG, Schols AM. Muscle quality is more impaired in sarcopenic patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2016;17:415–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Spruit MA, Singh SJ, Garvey C, ZuWallack R, Nici L, Rochester C, et al. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: key concepts and advances in pulmonary rehabilitation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2013;188:e13–e64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ferreira IM, Brooks D, White J, Goldstein R. Nutritional supplementation for stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;12: CD000998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. van de Bool C, Steiner MC, Schols AM. Nutritional targets to enhance exercise performance in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2012;15:553–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Drummond MJ, Rasmussen BB. Leucine‐enriched nutrients and the regulation of mammalian target of rapamycin signalling and human skeletal muscle protein synthesis. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2008;11:222–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Engelen MP, Wouters EF, Deutz NE, Menheere PP, Schols AM. Factors contributing to alterations in skeletal muscle and plasma amino acid profiles in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Clin Nutr 2000;72:1480–1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Romme EA, Rutten EP, Smeenk FW, Spruit MA, Menheere PP, Wouters EF. Vitamin D status is associated with bone mineral density and functional exercise capacity in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Med 2013;45:91–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Broekhuizen R, Wouters EF, Creutzberg EC, Weling‐Scheepers CA, Schols AM. Polyunsaturated fatty acids improve exercise capacity in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax 2005;60:376–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Schutz Y, Kyle UU, Pichard C. Fat‐free mass index and fat mass index percentiles in Caucasians aged 18–98 y. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2002;26:953–960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. van Wetering CR, Hoogendoorn M, Broekhuizen R, Geraerts‐Keeris GJ, De Munck DR, Rutten‐van Molken MP, et al. Efficacy and costs of nutritional rehabilitation in muscle‐wasted patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in a community‐based setting: a prespecified subgroup analysis of the INTERCOM trial. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2010;11:179–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bland JM, Altman DG. Best (but oft forgotten) practices: testing for treatment effects in randomized trials by separate analyses of changes from baseline in each group is a misleading approach. Am J Clin Nutr 2015;102:991–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jonker R, Deutz NE, Erbland ML, Anderson PJ, Engelen MP. Hydrolyzed casein and whey protein meals comparably stimulate net whole‐body protein synthesis in COPD patients with nutritional depletion without an additional effect of leucine co‐ingestion. Clin Nutr 2014;33:211–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ubhi BK, Riley JH, Shaw PA, Lomas DA, Tal‐Singer R, MacNee W, et al. Metabolic profiling detects biomarkers of protein degradation in COPD patients. Eur Respir J 2012;40:345–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dal Negro RW, Testa A, Aquilani R, Tognella S, Pasini E, Barbieri A, et al. Essential amino acid supplementation in patients with severe COPD: a step towards home rehabilitation. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis 2012;77:67–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Constantin D, Menon MK, Houchen‐Wolloff L, Morgan MD, Singh SJ, Greenhaff P, et al. Skeletal muscle molecular responses to resistance training and dietary supplementation in COPD. Thorax 2013;68:625–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Camillo CA, Osadnik CR, van Remoortel H, Burtin C, Janssens W, Troosters T. Effect of “add‐on” interventions on exercise training in individuals with COPD: a systematic review. ERJ Open Res 2016;2:00078‐2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Remels A, Schrauwen P, Broekhuizen R, Willems J, Kersten S, Gosker H, et al. Expression and content of PPARs is reduced in skeletal muscle of COPD patients. Eur Respir J 2007; 09031936.0144106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hornikx M, Van Remoortel H, Lehouck A, Mathieu C, Maes K, Gayan‐Ramirez G, et al. Vitamin D supplementation during rehabilitation in COPD: a secondary analysis of a randomized trial. Respir Res 2012;13:84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Caron MA, Debigare R, Dekhuijzen PN, Maltais F. Comparative assessment of the quadriceps and the diaphragm in patients with COPD. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2009;107:952–961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Casaburi R. Factors determining constant work rate exercise tolerance in COPD and their role in dictating the minimal clinically important difference in response to interventions. COPD 2005;2:131–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Watz H, Pitta F, Rochester CL, Garcia‐Aymerich J, ZuWallack R, Troosters T, et al. An official European Respiratory Society statement on physical activity in COPD. Eur Respir J 2014;44:1521–1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Thorpe O, Johnston K, Kumar S. Barriers and enablers to physical activity participation in patients with COPD: a systematic review. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev 2012;32:359–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Moses AW, Slater C, Preston T, Barber MD, Fearon KC. Reduced total energy expenditure and physical activity in cachectic patients with pancreatic cancer can be modulated by an energy and protein dense oral supplement enriched with n‐3 fatty acids. Br J Cancer 2004;90:996–1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Schoonjans K, Staels B, Auwerx J. The peroxisome proliferator activated receptors (PPARS) and their effects on lipid metabolism and adipocyte differentiation. Biochim Biophys Acta 1996;1302:93–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Agudelo LZ, Femenia T, Orhan F, Porsmyr‐Palmertz M, Goiny M, Martinez‐Redondo V, et al. Skeletal muscle PGC‐1alpha1 modulates kynurenine metabolism and mediates resilience to stress‐induced depression. Cell 2014;159:33–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Patterson AC, Chalil A, Aristizabal Henao JJ, Streit IT, Stark KD. Omega‐3 polyunsaturated fatty acid blood biomarkers increase linearly in men and women after tightly controlled intakes of 0.25, 0.5, and 1 g/d of EPA + DHA. Nutr Res 2015;35:1040–1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pison CM, Cano NJ, Cherion C, Caron F, Court‐Fortune I, Antonini MT, et al. Multimodal nutritional rehabilitation improves clinical outcomes of malnourished patients with chronic respiratory failure: a randomised controlled trial. Thorax 2011;66:953–960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. von Haehling S, Morley JE, Coats AJ, Anker SD. Ethical guidelines for publishing in the Journal of Cachexia, Sarcopenia and Muscle: update 2015. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2015;6:315–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1. Table E1: Nutrient composition of NUTRITION and PLACEBO products per 125 mL serving.

Table E2: Habitual dietary intake.