Abstract

Background:

Stigmatization and overall scarcity of psychiatrists and other mental health-care professionals remain a huge public health challenge in low- and middle-income countries, more specifically in India. Most patients seek help from faith healers, and awareness about psychiatrists and treatment methods is often lacking. Our study aims to explore public attitudes toward psychiatrists and psychiatric medication in five Indian metropolitan cities and to identify factors that could influence these attitudes.

Materials and Methods:

Explorative surveys in the context of public attitudes toward psychiatrists and psychiatric medication were conducted using five convenience samples from the general population in Chennai (n = 166), Kolkata (n = 158), Hyderabad (n = 139), Lucknow (n = 183), and Mumbai (n = 278). We used a quota sample with respect to age, gender, and religion using the census data from India as a reference.

Results:

Mean scores indicate that attitudes toward psychiatrists and psychiatric medication are overall negative in urban India. Negative attitudes toward psychiatrists were associated with lower age, lower education, and strong religious beliefs. Negative attitudes toward psychotropic medication were associated with lower age, male gender, lower education, and religion.

Conclusion:

In line with the National Mental Health Policy of India, our results support the perception that stigma is widespread. Innovative public health strategies are needed to improve the image of psychiatrists and psychiatric treatment in society and ultimately fill the treatment gap in mental health.

Key words: Attitudes toward psychiatric medication, attitudes toward psychiatrists, India, mental health stigma, South Asia

INTRODUCTION

Resources for mental health care are inequitably distributed between high- and low-income countries. It is estimated that 76%-85% of people with severe mental disorders receive no treatment of their disease in low- and middle-income countries.[1] According to the latest Mental Health Atlas released by the World Health Organization, the reported number of psychiatrists has increased by 25% between 2011 and 2014 in South-East Asian and African regions.[2] However, taking the large population in these areas into account, mental healthcare coverage remains low. Specifically, there are 6.6 psychiatrists for every 100,000 people in high-income countries, but only 0.5 psychiatrists for every 100,000 people in low- and middle-income countries. For India, a country with a population of over 1.3 billion,[3] this number is even lower with only 0.3 psychiatrists available for 100,000 people. The number of psychologists (0.07 per 100,000) and nurses (0.1 per 100,000) working with mental health care is even lower making it difficult for them to fill this treatment gap in India.[2]

While previous studies estimated the prevalence of mental disorders in India at 6.5%,[4] the data from the latest mental health survey suggest that it might be much higher at 10.6%.[5] These results imply that about 150 million patients in India are in need of psychiatric treatment. It is estimated that the small number of psychiatrists in India are only able to cover 10% of the patients in need of psychiatric treatment.[6] A significant number of patients seek help from general practitioners, faith healers, alternative medicine practitioners, and primary health-care centers. Various studies from India have indicated that only a small percentage of psychiatric patients consult a psychiatrist at the onset of symptoms.[7,8] Referrals to tertiary care centers have also been shown to take place predominantly through faith healers.[9] Naik et al.[10] reported that help-seeking behavior of caregivers followed a similar pattern; initial contact with a faith healer followed by a psychiatric consult was the most common pathway in two cities, which are geographically and culturally distinct from each other. Another study reported that almost 75% of caregivers attributed symptoms of schizophrenia to supernatural beliefs and that this subgroup was more likely to seek help from faith healers.[11] On similar lines, it has been reported that patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder who believed in supernatural causes were more likely to consult faith healers.[12]

Patients' stigma in consulting a psychiatrist often extends to psychiatric medication as well.[13] Negative attitudes of patients toward medication can result in poor compliance.[14] For patients and caregivers, familiarity with the illness and treatment could help develop positive attitudes toward psychiatric medication.[15,16] From a global perspective, a recent meta-analysis found that psychotherapy was preferred over medication by a majority of the respondents as a treatment for depression or schizophrenia.[17] Comparisons have shown, for example, that public attitudes toward psychiatric medication are more favorable in the USA than in Germany.[18] The authors propose that social, cultural, and health-care system differences might explain these differing attitudes. Data from India dealing with public attitudes toward psychiatric medication are lacking.

Recently, we compared two Indian metropolitan cities, Chennai and Kolkata, and found significant differences in attitudes toward psychiatrists.[19] Results showed that strong religious beliefs and lower education level correlated significantly with negative attitudes. Investigating these attitudes in various populations and identifying potential factors that might influence them could be critical in developing public health strategies to reducing stigma and positively modifying the image of psychiatrists in society. Considering the religious, cultural, linguistic, and social diversity in India, we extended our survey to include five metropolitan cities and investigated attitudes toward psychiatrists as well as psychiatric medication in the general population. We chose five capital cities from different states of India, belonging to distinct geographical regions and having a population of at least one million each.[20]

Chennai is the capital of the southern state of Tamil Nadu and the most widely spoken language there is Tamil. Kolkata is the capital city of West Bengal in East India and the predominant language there is Bengali. Hyderabad is the joint capital of the states of Andhra Pradesh and Telangana; Urdu and Telugu are mainly spoken here. Mumbai is located on the west coast of India and is the capital city of Maharashtra; Marathi and Hindi are widely spoken here. Lucknow is the capital of Uttar Pradesh, and Hindi is the dominant language spoken there.[20] To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study reporting attitudes toward psychiatrists and psychiatric medication in the general population from multiple Indian cities.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

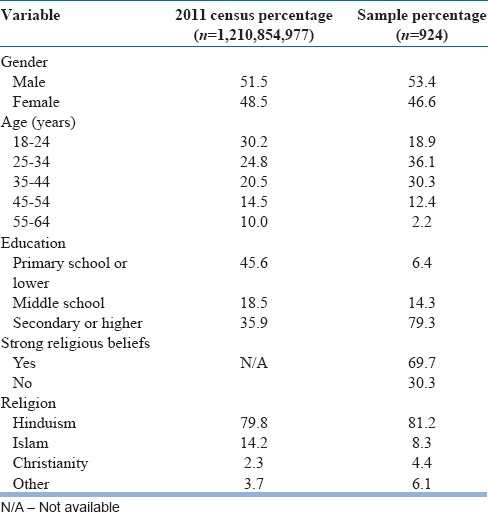

Data collection took place in 2014 between the months of April and July. The data collection process was conducted with assistance from a market research firm, Panoramix™. The assistance of the market research firm ensured the accurate and consistent completion of the questionnaires, resulting in a 100% completion rate. Since the participants who took part in completing the survey belonged to a pool registered with the market research firm, this resulted in a convenience sample. Data collection was first performed in Chennai and Kolkata; samples of these cities were additionally matched to each other since a direct comparison was conducted.[19] For the other three cities in the second round of data collection, we followed quota sampling with respect to gender, age, and religion using the census data as a reference.[20] Data collection did not involve a probability-based selection method. Participants were recruited from Chennai (n = 151), Kolkata (n = 149), Hyderabad (n = 139), Mumbai (n = 297), and Lucknow (n = 184). Recruited participants were aged 18–65 years. Detailed demographic characteristics of our sample and comparisons with the 2011 census data are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sociodemographics of the sample (n=924)

Questionnaire

As no validated questionnaire is currently available for determining attitudes toward psychiatrists in India, we used a slightly modified version of the validated questionnaire published by Gaebel et al.[21] Since our goal was to study public attitudes rather than awareness, the items on our questionnaire were framed to find out subjective opinions of the participants about psychiatrists and medication and not just factual knowledge. As the questionnaire was primarily created in the context of western societies, the wording had to be changed in some cases to be better understood culturally by the local population. These instances included religious, spiritual, and educational contexts. Other studies, for example,[22] have also used a modified version of this questionnaire. All questionnaires in English were translated into the local languages spoken in various cities and then back translated into English according to the recommended guidelines.[23] All versions were controlled for consistency and semantics by two independent certified translators.[24] The fully structured questionnaire was administered by a psychologist using a combination of guided self-report and interview methods, depending on the literacy and preferences of the respondents. The survey took about 15 min to complete. The questionnaire consisted of eight items related to attitudes toward psychiatrists and six items related to attitudes toward psychiatric medication. The responses were indicated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “definitely true” to “definitely not true.”

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the IBM program SPSS Statistics for Mac OS X Version 21 (IBM, USA). First, a mean score for all the eight items on the questionnaire for attitudes on psychiatrists was calculated for each participant. This mean score was calculated by dividing the total of the participants' responses by eight, resulting in a mean score ranging from one to five for each participant. Five of the eight items were reversed to account for negatively worded questions. In the case of this study, the figure one represented highly positive attitudes toward psychiatrists, while a figure of five indicated a high level of negative attitudes toward psychiatrists. On similar lines, for attitudes toward medication, a mean score was calculated for the six items on the questionnaire by dividing the total of the participants' responses by six resulting in a mean score ranging from one to five for each participant. Two of the six items were reversed to account for negatively worded questions.

First, a linear regression was performed with mean score for attitudes toward psychiatrists as the dependent variable and age, gender, education, strength of religious beliefs, and religion as the independent variables. Further, we performed a second linear regression with the mean score for attitudes toward psychiatric medication as the dependent variable and age, gender, education, strength of religious beliefs, and religion as the independent variables. A mean score of five indicates highly negative attitudes, whereas a score of one indicates highly positive attitudes toward psychiatrists or psychiatric medication.

RESULTS

The results of the first linear regression show a high overall mean score (2.69) indicating negative attitudes toward psychiatrists. Age (P < 0.001), education (P < 0.05), religion (P < 0.05), and strength of religious beliefs (P < 0.05) had a significant effect on attitudes toward psychiatrists [Table 2]. Higher negative attitudes toward psychiatrists correlated with lower age, lower education, and strong religious beliefs. Hinduism closely followed by Islam was associated with more negative attitudes toward psychiatrists. The results for individual items related to attitudes toward psychiatrists are presented in Table 3.

Table 2.

Public attitudes toward psychiatrists: Linear regression (n=924)

Table 3.

Public attitudes toward psychiatrists: Individual items (n=924)

The results of the second linear regression also show a similarly high overall mean score (2.68) indicating negative attitudes toward psychiatric medication. Age (P < 0.01), gender (P ≤ 0.001), education (P < 0.01), and religion (P ≤ 0.001) had a significant effect on attitudes toward psychiatric medication [Table 4]. Higher negative attitudes toward psychiatric medication correlated with lower age, male gender, lower education, and Hinduism. The results for individual items related to attitudes toward psychiatric medication are presented in Table 5.

Table 4.

Public attitudes toward psychiatric medication: Linear regression (n=924)

Table 5.

Public attitudes toward psychiatric medication: Idividual items (n=924)

DISCUSSION

Our survey results revealed negative attitudes toward psychiatrists as well as psychiatric medication in our sample comprising participants from the general population in five metropolitan cities in India. Negative attitudes toward psychiatrists correlated with lower age, lower education, strong religious beliefs, and religion; more negative attitudes were associated with the two major religions in India: Hinduism and Islam. Negative attitudes toward psychiatric medication were associated with lower age, male gender, lower education, and Hinduism.

The correlation of lower age with more negative attitudes toward both psychiatrists as well as toward psychiatric medication is a surprising and rather alarming finding since India has a much higher proportion of its population consisting of younger individuals compared to western countries.[20] Van der Auwera et al.[25] reported recently that approval toward both psychotherapy and medication increased with age in Germany. Previous studies investigating younger groups of the population in India, such as medical students, have also reported high levels of negative attitudes toward psychiatrists and psychiatry as a career choice.[26] Perhaps, the portrayal of psychiatrists in the modern media, for example, movies, has also contributed to this negative image among the younger population.[27] Interestingly, in line with our findings, the WHO mental health survey found that male gender and low education are among the sociodemographic variables associated with undertreatment.[28] High negative attitudes also correlated with the two predominant religions in India: Hinduism and Islam, which is possibly due to traditional belief systems and help-seeking attitudes that consider nonbiomedical therapies as more effective treatment methods than psychiatrists and psychiatric medication. Previous studies have shown that a high percentage of patients believe that prayer alone is sufficient treatment for psychiatric disorders.[29] The same study found that two-thirds of psychiatric patients attributed their symptoms of schizophrenia to magical or religious causes. At the same time, it is important to consider that religion can also have a positive impact on mental health by motivating patients to seek professional help; positive religious coping has been associated with better mental health outcomes.[30]

India's new mental health policy recognizes that patients with psychiatric illnesses face discrimination and stigmatization in society. It also acknowledges the lack of mental health-care services as well as reluctance from patients, families, and caregivers to seek help from mental health-care professionals.[31] Our findings are on similar lines; one-third of the participants we surveyed believed that psychiatrists specialize in psychiatry because they are not good enough for other specialties. Over half of the respondents endorsed that psychiatrists prescribe medication only to calm down their patients. About 45% of participants endorsed that psychiatric medication is harmful. These results show that perceived misconceptions regarding psychiatrists and their treatment methods including medication are widespread in society. To modify these negative public attitudes, it is critical that relevant recommendations of the new mental health policy are implemented. These recommendations include universal mental health care for all, increasing funding for mental health, and reducing the gap between requirement and availability of mental health-care professionals including psychiatrists and nurses. Sizeable steps were made toward addressing these, and other issues with the passing of the Mental Health Care Bill 2016, by the Government of India in March 2017. This progressive bill brought about a series of changes including redefining mental illness, ensuring that every person has the right to access mental healthcare, decriminalizing attempted suicide, and giving increased rights to persons suffering from mental illness with regard to treatment and who their nominated representative should be.[32,33] One of the main aims in the passing of the bill was to reduce the overall social stigma associated with mental illness in India.[34] While seen as a big step forward and progressive in aiming to provide an international standard of healthcare, there has been some criticism of the bill.[32,35] For one, it is felt that it could be a challenge to implement changes on such a sudden, drastic level. Furthermore, it is thought that dangerous consequences could arise if patients are given a total capacity in making mental healthcare and treatment decisions, especially under the circumstances of absent insight by the patients, or their symptoms coming in the way of their decision-making ability. A lack of resources could prove to be a major setback for the implementation of the bill. This is especially relevant in semiurban and rural areas, where there is poor infrastructure and an inadequate mental health workforce. While one of the main aims of the bill is to reduce the stigma of mental illness, there are fears that the difficulties faced in implementing the bill could work against this goal.[32,35]

It is also important to acknowledge further innovative strategies that aim to address the massive treatment gap. The health activity program delivered by lay counselors is one such step which has shown promising results.[36,37] Another possible strategy could be coordinating with and offering training programs for alternative medicine practitioners.[38] The WHO Mental Health Care Action Plan 2013–2020 emphasizes the importance of actively involving informal mental health-care providers in mental health-care programs.[1] The China–India mental health alliance has suggested an innovative collaboration between biomedical practitioners and traditional or alternative practitioners by creating a mental health community of practice. Specifically for India, practitioners of Ayurveda, Yoga, and Naturopathy; Unani; Siddha; Sowa-Rigpa and Homoeopathy could be integrated into the universal mental health-care model. Eventually, even faith healers and religious institutes could be incorporated into this model.[39] This approach might also have limitations, especially if the disease model of the patient and the faith healer is directly opposite to the biopsychosocial model of disease proposed by the psychiatrist. Convincing patients and faith healers to accept an alternative model might be challenging in some cases, for example, if the patient is convinced that he is guilty of causing his symptoms and these beliefs have perhaps been reinforced by the faith healer.

Our study is limited by the convenience sampling method which restricted our sample to five metropolitan cities in India. Considering that India has a large rural population, where availability and awareness of psychiatrists are even scarcer, further surveys are needed before our results can be generalized. Although our sample was broadly representative when compared to the 2011 census data for gender, age, and religion, it included a high number of participants who had completed secondary school. To the best of our knowledge, there are no validated questionnaires investigating attitudes toward psychiatrists and medication specifically developed for India. Therefore, we adapted this questionnaire from a validated questionnaire published by Gaebel et al., 2015.[21] Because there are no previous studies from India that can be compared to our results, it is difficult to definitively conclude from our data that our mean scores are high since such conclusions would have to be made in relative terms. Finally, although we controlled for possible confounding factors such as age, gender, and religion and other social and cultural factors may cause bias in our results.

CONCLUSION

Our survey in five urban metropolitan cities of India reports highly negative attitudes toward psychiatrists and psychiatric medication. We discuss the sociodemographic factors that correlate with negative attitudes and also recommend steps to modify these stigmatizing attitudes; this, in turn, could lead to patients getting evidence-based treatment at an early stage of disease manifestation.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. Mental Health Action Plan 2013-2020. WHO Library Cat DataLibrary Cat Data. 2013:1–44. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Mental Health Atlas 2014. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3.United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World Population Prospects: The 2015 Revision, Key Findings and Advance Tables. Working Paper No. ESA/P/WP. 241. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 4.NCMH Background Papers – Burden of Disease in India, National Commission of Macroeconomics and Health. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gururaj G, Varghese M, Benegal V, Rao GN, Pathak K, Singh LK, et al. National Mental Health Survey of India, 2015-2016: Summary. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patel V. The future of psychiatry in low- and middle-income countries. Psychol Med. 2009;39:1759–62. doi: 10.1017/s0033291709005224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chadda RK, Agarwal V, Singh MC, Raheja D. Help seeking behaviour of psychiatric patients before seeking care at a mental hospital. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2001;47:71–8. doi: 10.1177/002076400104700406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pradhan SC, Singh MM, Singh RA, Das J, Ram D, Patil B, et al. First care givers of mentally ill patients: A multicenter study. Indian J Med Sci. 2001;55:203–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jain N, Gautam S, Jain S, Gupta ID, Batra L, Sharma R, et al. Pathway to psychiatric care in a tertiary mental health facility in Jaipur, India. Asian J Psychiatr. 2012;5:303–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2012.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Naik SK, Pattanayak S, Gupta CS, Pattanayak RD. Help-seeking behaviors among caregivers of schizophrenia and other psychotic patients: A hospital-based study in two geographically and culturally distinct Indian cities. Indian J Psychol Med. 2012;34:338–45. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.108214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grover S, Nebhinani N, Chakrabarti S, Shah R, Avasthi A. Relationship between first treatment contact and supernatural beliefs in caregivers of patients with schizophrenia. East Asian Arch Psychiatry. 2014;24:58–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grover S, Patra BN, Aggarwal M, Avasthi A, Chakrabarti S, Malhotra S. Relationship of supernatural beliefs and first treatment contact in patients with obsessive compulsive disorder: An exploratory study from India. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2014;60:818–27. doi: 10.1177/0020764014527266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Loganathan S, Murthy SR. Experiences of stigma and discrimination endured by people suffering from schizophrenia. Indian J Psychiatry. 2008;50:39–46. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.39758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chandra IS, Kumar KL, Reddy MP, Reddy CM. Attitudes toward Medication and Reasons for Non-Compliance in Patients with Schizophrenia. Indian J Psychol Med. 2014;36:294–8. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.135383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grover S, Chakrabarti S, Sharma A, Tyagi S. Attitudes toward psychotropic medications among patients with chronic psychiatric disorders and their family caregivers. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2014;5:374–83. doi: 10.4103/0976-3147.139989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith CM, Barzman D, Pristach CA. Effect of patient and family insight on compliance of schizophrenic patients. J Clin Pharmacol. 1997;37:147–54. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1997.tb04773.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Angermeyer MC, van der Auwera S, Carta MG, Schomerus G. Public attitudes towards psychiatry and psychiatric treatment at the beginning of the 21st century: A systematic review and meta-analysis of population surveys. World Psychiatry. 2017;16:50–61. doi: 10.1002/wps.20383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schomerus G, Matschinger H, Baumeister SE, Mojtabai R, Angermeyer MC. Public attitudes towards psychiatric medication: A comparison between United States and Germany. World Psychiatry. 2014;13:320–1. doi: 10.1002/wps.20169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mungee A, Zieger A, Schomerus G, Ta TM, Dettling M, Angermeyer MC, et al. Attitude towards psychiatrists: A comparison between two metropolitan cities in India. Asian J Psychiatr. 2016;22:140–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2016.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Government of India, Census of India. 2011. [Last accessed on 25.04.17]. Available from: http://censusindia.gov.in .

- 21.Gaebel W, Zäske H, Zielasek J, Cleveland HR, Samjeske K, Stuart H, et al. Stigmatization of psychiatrists and general practitioners: Results of an international survey. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2015;265:189–97. doi: 10.1007/s00406-014-0530-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Catthoor K, Hutsebaut J, Schrijvers D, De Hert M, Peuskens J, Sabbe B. Preliminary study of associative stigma among trainee psychiatrists in Flanders, Belgium. World J Psychiatry. 2014;4:62–8. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v4.i3.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brislin RW. Back translation for cross-cultural research. J Cross Cult Psychol. 1970;1:185–216. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sartorius N, Kuyken W. Translation of Health Status Instruments. In: Orley J, Kuyken W, editors. Quality of Life Assessment: International Perspectives: Proceedings of the Joint-Meeting Organized by the World Health Organization and the Fondation IPSEN in Paris, July 2 – 3, 1993. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 1994. pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Van der Auwera S, Schomerus G, Baumeister SE, Matschinger H, Angermeyer M. Approval of psychotherapy and medication for the treatment of mental disorders over the lifespan. An age period cohort analysis. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2017;26:61–9. doi: 10.1017/S2045796015001134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lingeswaran A. Psychiatric curriculum and its impact on the attitude of Indian undergraduate medical students and interns. Indian J Psychol Med. 2010;32:119–27. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.78509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Swaminath G, Bhide A. 'Cinemadness': In search of sanity in films. Indian J Psychiatry. 2009;51:244–6. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.58287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang PS, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Angermeyer MC, Borges G, Bromet EJ, et al. Use of mental health services for anxiety, mood, and substance disorders in 17 countries in the WHO world mental health surveys. Lancet. 2007;370:841–50. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61414-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kate N, Grover S, Kulhara P, Nehra R. Supernatural beliefs, aetiological models and help seeking behaviour in patients with schizophrenia. Ind Psychiatry J. 2012;21:49–54. doi: 10.4103/0972-6748.110951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Behere PB, Das A, Yadav R, Behere AP. Religion and mental health. Indian J Psychiatry. 2013;55:187–94. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.105526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 31.Ministry of Health, Government of India; National Mental Health Policy of India: New Pathways, New Hope. 2014. [Last accessed on 2017 Apr 25]. Available from: https://www.nhp.gov.in/sites/default/files/pdf/national%20mental%20health%20policy%20of%20india%202014.pdf .

- 32.Rao GP, Math SB, Raju MS, Saha G, Jagiwala M, Sagar R, et al. Mental Health Care Bill, 2016: A boon or bane? Indian J Psychiatry. 2016;58:244–9. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.192015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Deepalakshmi K. All you Need to know about the Mental Healthcare Bill. 2017. [Last accessed on 2017 Apr 25]. Available from: http://www.thehindu.com/news/national/all-you-need-to-know-about-the-mental-healthcare-bill/article17662163.ece .

- 34.Kedia S. The Ambitious Mental Healthcare Bill is a Step Closer to a Progressive India. 2017. [Last accessed on 2017 Apr 25]. Available from: http://www.Yourstory.com .

- 35.Antony JT. Mental Health Care Bill-2016: An illusory boon; on close reading it is mostly bane. Indian J Psychiatry. 2016;58:363–5. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.196721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chowdhary N, Anand A, Dimidjian S, Shinde S, Weobong B, Balaji M, et al. The healthy activity program lay counsellor delivered treatment for severe depression in India: Systematic development and randomised evaluation. Br J Psychiatry. 2016;208:381–8. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.114.161075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Patel V, Weobong B, Weiss HA, Anand A, Bhat B, Katti B, et al. The Healthy Activity Program (HAP), a lay counsellor-delivered brief psychological treatment for severe depression, in primary care in India: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;389:176–85. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31589-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Holikatti PC, Kar N. Views of practitioners of alternative medicine toward psychiatric illness and psychiatric care: A study from Solapur, India. Educ Health (Abingdon) 2015;28:87–91. doi: 10.4103/1357-6283.161923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thirthalli J, Zhou L, Kumar K, Gao J, Vaid H, Liu H, et al. Traditional, complementary, and alternative medicine approaches to mental health care and psychological wellbeing in India and China. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3:660–72. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30025-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]