Abstract

Background:

Health care involves taking care of other peoples' lives. Professionals in the field of health care are expected to be at their best all the time because mistakes or errors could be costly and sometimes irreversible.

Aim:

This study assessed the quality of sleep and well-being of health workers in Najran city, Saudi Arabia.

Materials and Methods:

It was a cross-sectional study done among health workers from different hospitals within the kingdom of Najran, Saudi Arabia. The subjects were administered questionnaire that contained sections on demographic and clinical characteristics, sleep quality, and section relating to well-being.

Results:

One hundred and twenty-three health workers comprising 29 (23.6%) males and 94 (76.4%) females participated in this study. The majority of the workers 74 (60.2%) were nurses; a quarter were doctors while the remaining 13.6% accounted for other categories of health workers such as the pharmacist and laboratory technicians. Fifty-two (42.3%) of the workers were poor sleepers. Significantly (χ2 = 23.98, P = 0.000), majority of the subjects that were poor sleepers (84.6%) compared with the 42.3% of the good sleepers rated the last 12 months of their profession as a bit stressful or quite a bit stressful. Similarly, 46.2% of the workers that were poor sleepers significantly (χ2 = 24.69, P = 0.000) rated their ability to handle unexpected and difficult problems in their life as fair or poor compared with 14.1% of the good sleepers

Conclusion:

Health workers expressed some level of stress in their professional life, and a good proportion of the subjects were poor sleepers. There is, therefore, the need to establish a program within the health-care organization to address social, physical, and psychological well-being at work.

Key words: Health care, health workers, sleep quality, well-being

INTRODUCTION

Health-care workers are health-care professionals within medicine, nursing, or allied health professions that provide preventive, curative, promotional, or rehabilitative health-care services in a systematic way to individuals, families, or communities.[1,2] In the World Health Report 2006, the WHO defined health workers as “all people primarily engaged in actions with the primary intent of enhancing health.”[3] The global profile indicated that there are more than 59 million health workers in the world, distributed unequally between and within countries.[3,4]

Many jurisdictions reported shortfalls in the number of trained health workers to meet health needs of the population. At international level, world health organization estimated a shortage of almost 4.3 million doctors, midwives, nurses, and support workers worldwide to meet target coverage levels of essential primary health-care interventions.[3] In Uganda, the ministry of health reported that as many as 50% of staffing positions for health workers in rural and underserved areas remain vacant.[5] Without adequate numbers of trained and employed health workers, people cannot access the care they need, particularly the global poor.

The impact of shortage of health workers for populations is lack of access to essential health services such as prevention, information, drug distribution, emergencies, clinical care, and life-saving interventions. For health-care workers, the effect is an overwhelming workload and stress, which can lead to lack of motivation, fatigue, absenteeism, breakdowns, illness, migration, or even career change outside of the health field.[6,7]

Stress in the workplace is pervasive in the health-care industry because of inadequate staffing level, long work hours, exposure to infectious diseases and hazardous substances leading to illness or death, and in some countries, threat of malpractice and litigations.[6,7,8] The national institute of occupational safety and health, USA and a national report in Canada expressed that health-care workers have higher rates of substance abuse and suicide than other professions and elevated levels of depression and anxiety linked to job stress.[9,10] Elevated levels of stress were also linked to high rates of burnout, absenteeism and diagnostic errors, and to reduced patients' satisfaction.

Work-related stress is a growing problem worldwide. It affects not only the health and well-being of employees but also the productivity of organizations. Work-related stress arises where work demands of various types and combinations exceed the person's capacity and capability to cope.[11] Some of the many causes of work-related stress include long hours, heavy workload, job insecurity, and conflicts with co-workers or bosses. Symptoms include a drop in work performance, depression, anxiety, and sleeping difficulties. Sleep problems, apart from leading to a wide range of health disorders,[12] also have issues with safety concerns because they are associated with occupational injuries.[13,14]

There is paucity of research on stress and well-being of health workers in this region of the world. This becomes necessary bearing the challenges of health workers and the need to address them. This study, therefore, aims to assess the well-being and quality of sleep of health workers in Najran city, Saudi Arabia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Setting

The study was conducted in the Psychiatric hospital, Najran, among health workers that attended a conference organized by the hospital as part of the mental health day celebration. The hospital is a mental health institution that has facilities for both inpatient and outpatient services coupled with rehabilitation facility. There are also functioning laboratory and radiological services. The hospital has a consultation-liason service that it renders to neighboring hospitals like King Khalid Hospital, Maternal and Child hospital and Najran General Hospital, all within the city of Najran. Furthermore, the hospital extends its services to the prisons, etc.

Methods

This was a cross-sectional study done among health workers from different hospitals within the kingdom of Najran, Saudi Arabia. All participants provided informed consent. Ethical approval of this study was given by the management of the hospital. The subjects were administered questionnaire that contained sections on demographic and clinical characteristics, sleep quality, and section relating to well-being. The demographic and clinical characteristic section fielded questions on age, sex, marital status, profession, place of work, duration of practice, and nationality. The blood pressure (BP), weight, and height of the subjects were also included in this section.

The subjects were requested to rest for 15 min before the BP was taken. The BP was measured using a mercury sphygmomanometer with appropriately sized cuff. The first tapping sound heard (Korotkoff Phase 1) was taken as the systolic BP while the diastolic BP was recorded as pressure at disappearance (Phase 5) of the Korotkoff sounds. Hypertension was defined using the Joint National Committee classification.[15]

Basal mass index (BMI) was calculated using the formula– weight (kg)/height2 (m2). The BMI was classified according to the WHO classification.[16] Underweight is BMI <18.5, normal range– BMI 18.5–24.9, overweight– BMI 25–29.9 while obesity is BMI >30.

Sleep quality was determined using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality index which is an effective instrument used to measure the quality and pattern of sleep.[17] It differentiates poor from good sleep by measuring seven domains: subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, use of medication, and daytime dysfunction over the last month. The seven domains are then added to yield a total score. A global score of five or greater indicates a “poor” sleeper.

The last section of the questionnaire fielded questions relating to the ability of the subjects to handle day-to-day demands, unexpected or difficult demands, stress relating to their profession in the last 12 months, and the most important thing contributing to stress in their life.

Data analysis

The data were analyzed using the statistical package for social sciences (SPSS) software version 16. Percentages or mean and standard deviations were computed for baseline characteristics. Comparisons of categorical data were done using Chi-square test while Student's t-test was used to determine the statistical difference between means. The corresponding P values were found to determine the level of significance. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

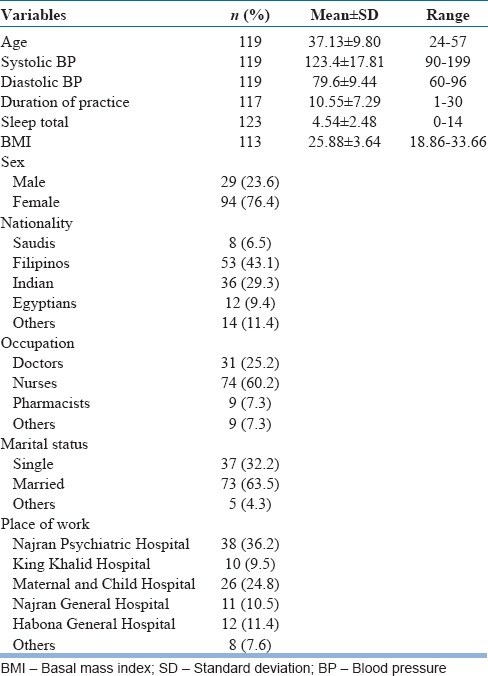

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the subjects were as shown in Table 1. One hundred and twenty-three health workers comprising 29 (23.6%) males and 94 (76.4%) females participated in this study. The age ranged between 24 and 57 years with a mean age of 37.13 ± 9.80. There is significant difference (t = 3.95, P = 0.002) between the ages of male subjects (mean = 43.03 ± 11.71 years) and the female subjects (mean 35.23 ± 8.33 years). The average duration of practice for the doctors, nurses, and pharmacists were 16.84 ± 8.65, 7.66 ± 4.87, and 8.56 ± 6.33 years, respectively.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of subjects

Thirty eight (36.2%) of the subjects were health workers from Najran Psychiatric Hospital, 26 (24.8%) from Maternal and Child Hospital, 12 (11.4%) from Habona General Hospital, 11 (10.5%) from Najran General Hospital, 10 (9.5%) from King Khalid Hospital, and 8 (7.6%) from other Hospitals, all within the province of Najran in Saudi Arabia. The Filipinos (43.1%) and the Indians (29.3%) constituted more than two-thirds of the nationalities of the subjects. Close to three-quarter of the subjects were married. The majority of the subjects 74 (60.2%) were nurses; a quarter were doctors while the remaining 13.6% accounted for other categories of health workers such as the pharmacists, laboratory technicians.

The mean BMI was 25.88 ± 3.64 kg/m2 with a range of 18.86–33.66 kg/m2. Forty-two (34.1%) of the subjects were overweighed while 23 (18.7%) were obese (i.e., more than 50% had BMI above normal values). The male had statistically higher BMI than the females (male 29.25 ± 3.20, female 24.71 ± 3.02, t = 6.88, P = 0.000). Using the diastolic BP, 26 (21.1%) of the subjects were hypertensive.

Fifty-two (42.3%) of the subjects were poor sleepers. A breakdown by profession indicated that a quarter of the doctors were poor sleeper while 36 (48.6%) of the nurses and 3 (33.3%) of the pharmacists were poor sleeper. The nurses were significantly poor sleeper compared with the doctors (χ2 = 4.68, P = 0.03). There was no statistical difference in total sleep between male and female subjects (χ2 = 0.29, P = 0.59).

Sixty-seven (54.5%) of the subjects rated most days of their life as being “a bit stressful to quite a bit stressful.” In the last 12 months of their profession, 74 (60.2%) of the subjects found this period to be “a bit stressful to quite a bit stressful.” However, majority of the subjects (82.9%) rated their ability to handle the day-to-day demands in their life as good or excellent while 72.1% rated their ability to handle unexpected and difficult problems in their life as good or excellent. For the most stressful thing contributing to the feeling of stress, the subjects indicated work situation/professional responsibility (36.6%), own health situation (26%), financial situation (11.4%), personal relationship (9.8%), time pressure (8.1%), and others (8.1%). However, only 9.7% expressed been dissatisfied with life generally.

Significantly (χ2 = 23.98, P = 0.000), majority of the subjects that were poor sleepers (84.6%) compared with the 42.3% of the good sleepers rated the last 12 months of their profession as a bit stressful or quite a bit stressful. Similarly, 46.2% of the subjects that were poor sleepers significantly (χ2 = 24.69, P = 0.000) rated their ability to handle unexpected and difficult problems in their life as fair or poor compared with 14.1% of the good sleepers.

DISCUSSION

This study set out to assess the well-being and quality of sleep of health workers in Najran city of Saudi Arabia. Findings from this study indicated that health workers expressed some level of stress in their professional life and in their ability to handle unexpected and difficult problems. This is in keeping with reports that modern medical practice is extremely demanding and stressful.[18]

Health care involves taking care of other peoples' lives and mistakes or errors could be costly and sometimes irreversible. Thus, professionals in the field of health care are expected to be at their best all the time. This could be physically and mentally challenging as these professionals face a lot of stressors that include work overload, excessive working hours, sleep deprivation, repeated exposure to emotionally charged situations, dealing with difficult patients, inappropriate capacity utilization, delays in promotion, and conflicts with other staff.[6,7,19] In addition to this work-related stress, irregular social and family life have been reported as a component of ongoing burn out process in these professionals.[20,21] The stress experienced by medical professionals results in high rates of marital problems, which sometimes end in divorce, physical illness, social isolation, decreasing satisfaction with work, suicide, substance abuse, and depression.[21,22,23,24] Stress, especially due to work or family, has been linked to disturbed sleep.[25]

It is therefore, not surprising that report from this study demonstrated that a good proportion of the subjects were poor sleepers. Furthermore, the poor sleepers significantly rated the last 12 months of their profession as stressful and their ability to handle unexpected and difficult problems in their life as not good. This is consistent with study that reported less sleep problems in subjects satisfied with their work.[26] Sleep is a basic and necessary biological process that demands to be satisfied as much as our need for food and drink. Good quality sleep is essential for good health and well-being. Sleep difficulties are associated with chronic diseases, mental disorders, health-risk behaviors, limitations of daily functioning, injury, and mortality.[12,27] Furthermore, sleep loss can lead to disturbances in cognitive and psychomotor function including mood, thinking, concentration, memory, learning, vigilance, and reaction times.[12,28] These disturbances have adverse effects on well-being, productivity, and safety. Insufficient sleep is a direct contributor to injury and death from motor vehicle and workplace accidents.[29]

Another factor that could have contributed to the poor sleep of health workers is the nature of work which involves shift or call duties. Studies have consistently shown that individuals engaged in such duties experience disturbed sleep and excessive sleepiness relative to day workers.[25,30,31] These symptoms are likely due to the fact that shift workers' behavioral sleep-wake schedules are out of phase and often in direct opposition to their endogenous circadian rhythms.[32,33] The most immediate consequence of shift work is impaired alertness, which has widespread effects on core brain functions — reaction time, decision making, information processing, and the ability to maintain attention. This impairment leads to preventable errors, accidents, and injuries, especially in high-risk environments. Furthermore, relationships have been demonstrated between shortened sleep and a range of health problems including hypertension,[34] Type 2 diabetes,[35] obesity,[36] and cardiovascular disease.[37,38] It is not surprising then that more than half of the subjects were either overweight or obese while about one-fifth were hypertensive. This is worrisome because large proportions (85%) of the subjects were nurses and doctors who are suppose to be of higher health literacy and education. It has been largely assumed that health-care workers take better care of themselves than the patients they treat because they have greater knowledge of appropriate health-care choices than the general public and because of their position as role models for patients. However, Helfand and Mukamal reported that despite their perceived status as role models, health-care workers frequently fail to adopt behavior that is healthier than the rest of the population.[39]

It is worth mentioning that majority of the respondents in this study were not of Saudi origin. This has implication on the well-being of immigrant workers. Studies have shown that the main factors pulling health workers to migrate are attractive salaries and benefits, better working environments, or improved quality of life for the worker and the family.[40,41] In particular, they can save large sums of money and take or send them home, often significantly stimulating the economy in their own countries. However, been a foreigner in another country has its own challenges.

Despite the small sample size and cross-sectional design of the study, the fact remains that the field of medicine can be quite stressful and is both emotionally demanding and logistically rigorous. Health workers, apart from being affected by the same variables that impose stress on the general population, are also prone to stress because of the peculiarities of their work situation and the expectation of the society at large. Health-care workers are notorious for neglecting their own care and not taking time for their own well-being. The workers who are treating patients can sometimes be left out of the well-being equation. There is, therefore, the need to establish a well-being program within the health-care organization to give workers the energy, focus, and adaptability they need to be their best every day. Such program should be comprehensive enough to address social, physical, and psychological well-being at work.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Orvill AB, Dal Poz MR, Shengelia B, Kwankam S, Issakov A, Stilwell B, et al. Human, physical, and intellectual resource generation: Proposals for monitoring. In: Murray CJ, Evans D, editors. Health Systems Performance Assessment: Debates, Methods and Empiricism. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003. pp. 273–87. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Diallo K, Zurn P, Gupta N, Dal Poz M. Monitoring and evaluation of human resources for health: An international perspective. Hum Resour Health. 2003;1:3. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-1-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. The World Health Report 2006: Working Together for Health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Speybroeck N, Ebener S, Sousa A, Paraje G, Evans DB, Prasad A. Inequality in access to human resources for health: Measurement issues. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rockers P, Jaskiewicz W, Wurts L, Mgomella G. Capacity Plus Project. Washington, DC: 2011. Feb, Determining Priority Retention Packages to Attract and Retain Health Workers in Rural and Remote Areas in Uganda. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marzabadi EA, Tarjhorani H. Job stress, job satisfaction and mental health. J Clin Diagn Res. 2007;4:224–34. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lambrou P, Kontodimopoulos N, Niakas D. Motivation and job satisfaction among medical and nursing staff in a Cyprus public general hospital. Hum Resour Health. 2010;8:26. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-8-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andrew LB. Suicide in Physicians. Medscape. 2003;4:5–7. [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). Exposure to stress: Occupational hazards in hospitals. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Canada's Health Care Providers. Ottawa: Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2007. Canadian Institute for Health Information. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liam V. Moderating the effects of work-based support on the relationship between job insecurity and its consequences. Work Stress. 1997;11:231–66. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sleep Disorders and Sleep Deprivation: Anunmet Public Health Problem. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2006. Committee on Sleep Medicine and Research, Institute of Medicine of the National Academy of Sciences. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kling RN, McLeod CB, Koehoorn M. Sleep problems and workplace injuries in Canada. Sleep. 2010;33:611–8. doi: 10.1093/sleep/33.5.611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salminen S, Oksanen T, Vahtera J, Sallinen M, Härmä M, Salo P, et al. Sleep disturbances as a predictor of occupational injuries among public sector workers. J Sleep Res. 2010;19(1 Pt 2):207–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2009.00780.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL, et al. Seventh report of Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Hypertension. 2003;42:1206–52. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000107251.49515.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organization. Report of a WHO Expect Committee. WHO Technical Report Series 854. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1995. Physical Status: The Use and Interpretation of Anthropometry. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28:193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kakunje A. Stress among health care professionals – The need for resiliency. Online J Health Allied Sci. 2011;10:1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Familoni OB. An overview of stress in medical practice. Afr Health Sci. 2008;8:6–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Couper I. How to cope with stress and avoid burnout. In: Mash B, Blitz-Lindeque J, editors. South African Family Practice Manual. 2nd ed. Pretoria: Van Schaik; 2006. pp. 379–80. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Olkinuora M, Asp S, Juntunen J, Kauttu K, Strid L, Aärimaa M. Stress symptoms, burnout and suicidal thoughts in Finnish physicians. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1990;25:81–6. doi: 10.1007/BF00794986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hawton K, Malmberg A, Simkin S. Suicide in doctors. A psychological autopsy study. J Psychosom Res. 2004;57:1–4. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00372-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gaede B. Burnout: A personal journey. S Afr Fam Pract. 2005;47:5–6. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Firth-Cozens J. Doctors, their wellbeing and their stress. BMJ. 2003;326:670–1. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7391.670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Akerstedt T, Fredlund P, Gillberg M, Jansson B. Work load and work hours in relation to disturbed sleep and fatigue in a large representative sample. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53:585–8. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00447-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuppermann M, Lubeck DP, Mazonson PD, Patrick DL, Stewart AL, Buesching DP, et al. Sleep problems and their correlates in a working population. J Gen Intern Med. 1995;10:25–32. doi: 10.1007/BF02599573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ram S, Seirawan H, Kumar SK, Clark GT. Prevalence and impact of sleep disorders and sleep habits in the United States. Sleep Breath. 2010;14:63–70. doi: 10.1007/s11325-009-0281-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dinges DF, Pack F, Williams K, Gillen KA, Powell JW, Ott GE, et al. Cumulative sleepiness, mood disturbance, and psychomotor vigilance performance decrements during a week of sleep restricted to 4-5 hours per night. Sleep. 1997;20:267–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stutts JC, Wilkins JW, Scott Osberg J, Vaughn BV. Driver risk factors for sleep-related crashes. Accid Anal Prev. 2003;35:321–31. doi: 10.1016/s0001-4575(02)00007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ohayon MM, Lemoine P, Arnaud-Briant V, Dreyfus M. Prevalence and consequences of sleep disorders in a shift worker population. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53:577–83. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00438-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Akerstedt T. Shift work and disturbed sleep/wakefulness. Occup Med (Lond) 2003;53:89–94. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqg046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Richardson GS, Malin HV. Circadian rhythm sleep disorders: Pathophysiology and treatment. J Clin Neurophysiol. 1996;13:17–31. doi: 10.1097/00004691-199601000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Akerstedt T, Torsvall L, Gillberg M. Sleepiness in shiftwork. A review with emphasis on continuous monitoring of EEG and EOG. Chronobiol Int. 1987;4:129–40. doi: 10.3109/07420528709078519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vgontzas AN, Liao D, Bixler EO, Chrousos GP, Vela-Bueno A. Insomnia with objective short sleep duration is associated with a high risk for hypertension. Sleep. 2009;32:491–7. doi: 10.1093/sleep/32.4.491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spiegel K, Knutson K, Leproult R, Tasali E, Van Cauter E. Sleep loss: A novel risk factor for insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. J Appl Physiol. 2005;99:2008–19. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00660.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Watanabe M, Kikuchi H, Tanaka K, Takahashi M. Association of short sleep duration with weight gain and obesity at 1-year follow-up: A large-scale prospective study. Sleep. 2010;33:161–7. doi: 10.1093/sleep/33.2.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sabanayagam C, Shankar A. Sleep duration and cardiovascular disease: Results from the National Health Interview Survey. Sleep. 2010;33:1037–42. doi: 10.1093/sleep/33.8.1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bagai K. Obstructive sleep apnea, stroke, and cardiovascular diseases. Neurologist. 2010;16:329–39. doi: 10.1097/NRL.0b013e3181f097cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Helfand BK, Mukamal KJ. Healthcare and lifestyle practices of healthcare workers: Do healthcare workers practice what they preach? JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:242–4. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamainternmed.1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stilwell B, Diallo K, Zurn P, Dal Poz MR, Adams O, Buchan J. Developing evidence-based ethical policies on the migration of health workers: Conceptual and practical challenges. Hum Resour Health. 2003;1:8. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-1-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Trinidad and Tobago: A Case Study. Port of Spain: ECLAC; 2003. Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC). Emigration of Nurses from the Caribbean: Causes and Consequences for the Socio-economic Welfare of the Country. [Google Scholar]