Abstract

Background

Communication with health care providers during diagnosis and treatment planning is of special importance because it can influence a patient’s emotional state, attitude, and decisions about their care. Qualitative evidence suggests that some patients experience poor communication with health care providers and have negative experiences when receiving their cancer diagnosis. Here, we use survey data from 8 provinces to present findings about the experiences of Canadian patients, specifically with respect to patient–provider communication, during the diagnosis and treatment planning phases of their cancer care.

Methods

Data from the Ambulatory Oncology Patient Satisfaction Survey, representing 17,809 survey respondents, were obtained for the study.

Results

Most respondents (92%) felt that their care provider told them of their cancer diagnosis in a sensitive manner. Most respondents (95%) also felt that they were provided with enough information about their planned cancer treatment. In contrast, more than half the respondents who had emotional concerns upon diagnosis (56%) were not referred to services that could help with their anxieties and fears. Also, 18% of respondents reported that they were not given the opportunity to discuss treatment options with a care provider, and 17% reported that their care providers did not consider their travel concerns while planning for treatment.

Conclusions

Measuring the patient experience allows for an understanding of how well the cancer control system is addressing the physical, emotional, and practical needs of patients during diagnosis and treatment planning. Although results suggest high levels of patient satisfaction with some aspects of care, quality improvement efforts are still needed to provide person-centred care.

Keywords: Cancer diagnosis, patient experiences, treatment planning, communication, Canadian health system

INTRODUCTION

A cancer diagnosis can be an unexpected life-changing event for patients and families. While learning about the diagnosis, they might experience various reactions such as shock, disbelief, confusion, sadness, anger, guilt, and resignation1. The moment is recalled vividly by patients for years to come, given that it represents a disruptive milestone and an unexpected turn in life. In addition to the emotional turmoil, patients often have to quickly gain new knowledge so that they understand their care options when discussing treatment plans with their provider, while trying to cope with the news. Communication with health care providers during diagnosis and treatment planning is therefore of particular sensitivity and importance, and it can influence a patient’s emotional state, attitude, and decisions about treatment2,3.

The relevance of the patient–provider relationship, including effective communication, is recognized as a critical aspect of the patient experience. The patient experience framework developed by the National Health Service in the United Kingdom highlights emotional support; respect for patient-centred values, preferences, and expressed needs; and information about clinical status and progress as key elements in the patient experience4. Within the context of cancer care, the U.S. National Cancer Institute conducted an extensive literature review to identify key functions involved in effective patient-centred communication. That review highlighted the importance of fostering clinician–patient relationships, exchanging information, and responding to the emotions of patients, among other functions5,6. During the diagnostic period in particular, all those elements should materialize in the initial interaction between patients and health care providers.

Despite the importance of the patient experience, studies of that experience during cancer diagnosis and treatment planning in the Canadian context are scarce. However, some available qualitative evidence suggests that patients can encounter poor communication and have negative experiences when receiving their diagnosis2. Here, we use survey data from 8 provinces to present findings about the experiences of Canadian patients during the diagnosis and treatment planning phases of their cancer journey. Measuring the patient experience nationally and provincially allows for an understanding of how well the cancer control system is delivering high-quality care while addressing patient needs and supporting a positive experience for patients and their families.

METHODS

This descriptive study used results from the Ambulatory Oncology Patient Satisfaction Survey (aopss) to explore the experiences of Canadian patients during diagnosis and treatment planning. The aopss is designed to capture the experiences of patients who have received outpatient cancer treatment in the preceding 6 months. Surveys were mailed by the survey administrator (National Research Corporation–NRC Health, Lincoln, NE, U.S.A.) between 2012 and 2016 to a random selection of cancer patients in British Columbia (2012), Alberta (2015), Saskatchewan (2013), Manitoba (2016), Ontario (2015–2016 fiscal year), Nova Scotia (2016), Newfoundland and Labrador (2016), and Prince Edward Island (2013). Patients were included in the present study if they had received active treatment in an ambulatory setting in the 6 months preceding survey completion, if they had a confirmed diagnosis of cancer, and if they were 18 years of age or older (based on date of birth when the data were extracted).

NRC Health provided national- and provincial-level data for select questions pertaining to the patient experience with diagnosis and treatment planning (Table i). National-level findings are presented.

TABLE I.

Diagnosis and treatment planning questions from the Ambulatory Oncology Patient Satisfaction Survey

| Topic | Question |

|---|---|

| Diagnosis |

|

| Treatment planning |

|

RESULTS

The 17,809 survey respondents who met the study criteria were almost evenly distributed between men and women. Most respondents had received a first-time cancer diagnosis, half held a postsecondary degree, and 39.8% had been diagnosed for less than a year when they answered the survey. Table ii outlines the characteristics of the sample.

TABLE II.

Characteristics of the 17,809 study participants

| Variable | Value [n (%)] |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Men | 7,578 (42.6) |

| Women | 9,362 (52.6) |

| Unknown | 869 (4.9) |

| Education | |

| Less than secondary school | 4,131 (23.2) |

| Secondary school graduate | 4,016 (22.6) |

| Postsecondary graduate | 8,639 (48.5) |

| Unknown or missing | 1,023 (5.7) |

| Time since diagnosis | |

| <6 months | 2,883 (16.2) |

| 6 Months to <1 year | 5,878 (33.0) |

| 1 Year to <2 years | 3,616 (20.3) |

| 2 Years to <5 years | 3,095 (17.4) |

| ≥5 Years | 2,113 (11.9) |

| Unknown or missing | 224 (1.3) |

| Type of cancer diagnosis | |

| First-time diagnosis | 11,342 (63.7) |

| Repeat diagnosis | 5,463 (30.7) |

| Unknown or missing | 1,004 (5.6) |

| Cancer site | |

| Breast | 4,379 (24.6) |

| Lung | 1,383 (7.8) |

| Colon, rectum, or bowel | 1,407 (7.9) |

| Cervix, uterus, ovary | 766 (4.3) |

| Prostate, testes | 2,154 (12.1) |

| Other, unknown, or missing | 7,720 (43.3) |

Health Care Providers Involved with Diagnosis and Treatment Planning

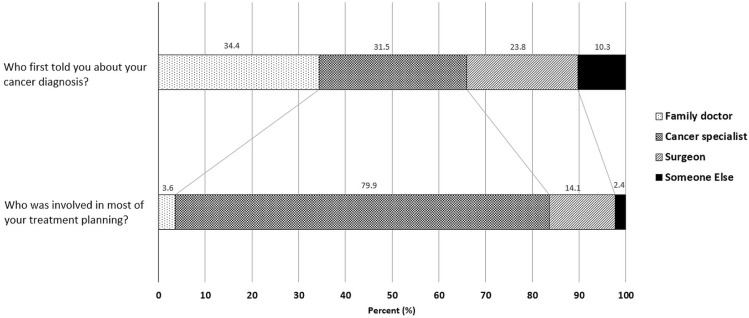

Based on responses to the aopss, family doctors (34.4%) and cancer specialists (31.5%) were the main care providers who communicated with patients about their cancer diagnosis; surgeons were less involved (23.8%). The landscape changed during treatment planning: treatment planning more often involved cancer specialists (79.9%) than surgeons (14.1%) or family doctors (3.6%, Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Health care provider in charge of communicating a cancer diagnosis and treatment planning, 2012–2016 (most recent year available for each province, combined). Includes data from British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario, Nova Scotia, Newfoundland and Labrador, and Prince Edward Island.

Hearing About the Cancer Diagnosis

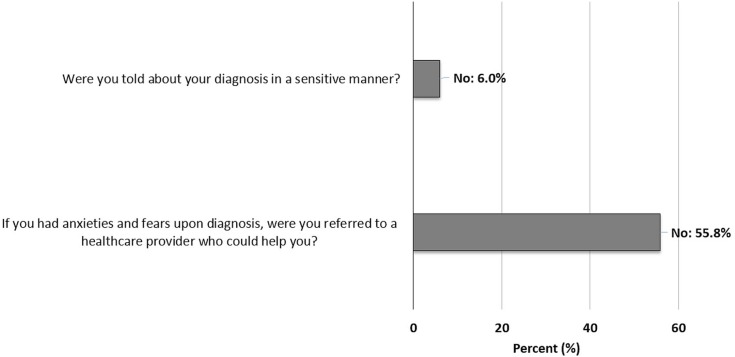

Almost all patients felt that they had been told about their diagnosis in a sensitive manner, but 6.0% of patients did express dissatisfaction about how they had been told (interprovincial range: 2.9%–6.8%). Patients with a postsecondary or graduate degree were less likely to say that they had been told of their diagnosis in a sensitive manner, with a response of “no” being given by 7.0% of that group compared with 5.1% of patients holding a secondary school degree and 4.8% of those with less education.

At least half the patients who had anxieties and fears upon diagnosis were not referred to a health care provider who could help address their emotional needs (55.8% not referred, Figure 2). Notably, wide variation was evident across Canada (not referred: 49.3%–67.7%) and across cancer sites, with prostate cancer patients being less likely to be referred for emotional support, even though they reported having anxieties and fears upon diagnosis (63.1% not referred).

FIGURE 2.

Percentage of patients who answered “no” to questions about diagnosis, 2012–2016 (most recent year available for each province, combined). Includes data from British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario, Nova Scotia, Newfoundland and Labrador, and Prince Edward Island.

Planning for Cancer Treatment

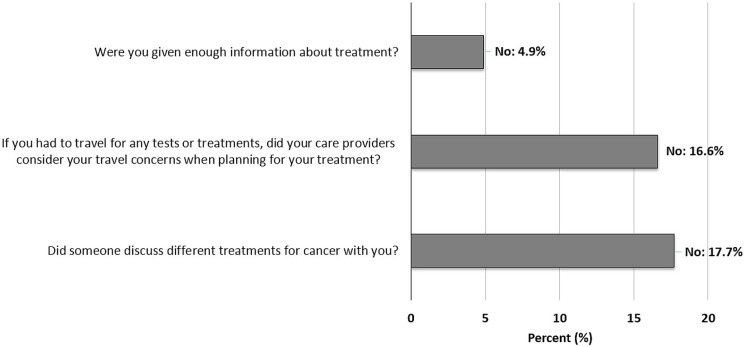

The survey included three key person-centred factors in treatment planning (Figure 3):

■ Receiving enough information about treatment

■ Having the opportunity to discuss treatment options with the health care provider

■ Having travel concerns considered during treatment planning

FIGURE 3.

Percentage of patients who answered “no” to questions about treatment planning, 2012–2016 (most recent year available for each province, combined). Includes data from British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario, Nova Scotia, Newfoundland and Labrador, and Prince Edward Island.

With respect to information received during treatment planning, only 4.9% of patients expressed dissatisfaction (interprovincial range: 3.1%–6.9%). In contrast, dissatisfaction with respect to discussion with the health care provider about the various treatment options for their cancer was reported by 17.7% of patients (interprovincial range: 13.2%–20.4%). That dissatisfaction registered especially high for patients with gynecologic cancers (26.2%); patients with prostate or testicular cancers were less dissatisfied (10.4%).

Practical considerations concerning travel arise for patients during planning for cancer treatment. Some patients live farther away from regional cancer treatment centres, which can place financial and practical strains on patients and families7. Of patients who had to travel to the treatment centre, 16.6% reported that their care providers did not consider their travel concerns during planning for treatment (interprovincial range: 11.4%–17.6%).

DISCUSSION

The results of the present study show high levels of patient satisfaction with some aspects of care during diagnosis and treatment planning. For instance, findings suggest that, in most cases, care professionals across Canada communicate with patients about the cancer diagnosis in a sensitive manner. Even though delivery of this news might not have a direct impact on disease management or outcomes, the manner in which physicians communicate about a cancer diagnosis can affect the level of patient distress8. If the delivery is reassuring and empathetic, it can help to alleviate the emotional turmoil that patients and families go through when receiving the news for the first time3. Moreover, initial interactions with patients have a long-lasting effect in the patient–provider relationship. Patients and care givers who perceive care interactions as supportive will tend to trust the care provider’s recommendations for treatment and will tend to feel less apprehensive about the future9. In contrast, negative verbal or nonverbal behaviour can discourage patients from participating in discussions about their care10,11.

Another important aspect of a good patient experience is receiving enough information about treatment. Effective information exchange during this phase of care has been identified as critical to patients with cancer, and it contributes to a good relationship with care providers2,12. Most respondents in the present study felt that they had been provided with enough information about their planned cancer treatment. It is important to note that the concept of receiving “sufficient information” can vary from one patient to the next and that sometimes, for some individuals, the amount of information provided can be overwhelming. Thus, it becomes essential to estimate the level of information that patients want to receive and to check back with them once they have had a chance to review it so that any outstanding questions can be addressed13.

In contrast, the patient experience could, in some areas, be bettered through quality improvement efforts. For example, more than half the survey respondents who had emotional concerns upon diagnosis were not referred to services that could help with their anxieties and fears. Those feelings (of anxiety, fear, anger, hopelessness) are common in patients and families who learn about a cancer diagnosis for the first time and can intensify over time if they remained unaddressed. The wide interprovincial range observed in the survey results indicate that practices in some high-performing provinces (or even from international jurisdictions) could be adopted more broadly.

During treatment planning, some patients reported they were not given the opportunity to discuss treatment options with a care provider. Evidence shows that even when patients tend to expect an active (or shared) role in decision-making, their actual involvement does not match their expectations14. In addition, the results showed that a patient’s travel concerns are sometimes overlooked by care providers when planning for treatment. Travelling long distances to receive treatment entails practical and financial challenges (for example, a need to make childcare arrangements and to take unpaid time off work) for both patients and families, who have little time to plan, rearrange tasks, and reach out for help before treatment starts15,16. Given this potential barrier to treatment, care providers should address the prospective travel burden while discussing treatment with patients and families—and especially when treatment will extend over a long period of time.

Finally, it is important to keep in mind that one size does not fit all. For example, demographic characteristics such as sex, age, and education level can influence the desire for participation in decision-making, with some patients being eager to actively participate in their care, and others perhaps preferring to be less involved17. Results from the aopss indicate that differences in patient satisfaction between selected disease sites and education levels can be a possibility that merits further investigation in future studies.

Limitations

As with any survey, the aopss carries a risk of recall bias (especially in patients who had been told about their diagnosis several years before they completed the survey) and self-report bias. The aopss patient satisfaction data included 8 of 10 provinces. Because not all provinces and territories were represented in the results, findings might not be fully generalizable to the country as a whole. As explained in the Methods section, data from the most recent available year for each province were used. Because the data represent multiple years, cautious interpretation of interprovincial ranges is advised. Finally, the effects of personal factors—including immigration status and cultural background, income, place of residence (for example, remote, urban, or rural)—were not addressed in the study. Now that the present study has identified some communication gaps between patients and health care providers during the diagnostic and treatment planning phases, the influence of social determinants of health such as those already listed—and others—warrants further investigation.

CONCLUSIONS

The experiences of patients with cancer could be improved in several areas. Findings point to a need for clinicians to identify and address the emotional needs of patients who have received the news about their diagnosis, including making proper referrals to support services. During treatment planning, enabling open discussion with patients about treatment options and addressing practical concerns or potential barriers to receiving treatment (for example, travel concerns) is critical. Lastly, continued reporting about the patient experience at the system level allows for a better understanding of how well the cancer control system is delivering high-quality care.

The System Performance Initiative at the Canadian Partnership Against Cancer will, in early 2018, be releasing a report about the patient experience. It will be the first pan-Canadian report about the experience of patients throughout their cancer journey that uses quantitative and qualitative data to describe that experience, while providing relevant interjurisdictional comparisons. More information about the system performance reports can be found at http://systemperformance.ca.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

We have read and understood Current Oncology’s policy on disclosing conflicts of interest, and we declare that we have none.

REFERENCES

- 1.Canadian Cancer Society . Emotions and cancer [Web page] Toronto, ON: Canadian Cancer Society; [Available at: http://www.cancer.ca/en/cancer-information/cancer-journey/recently-diagnosed/emotions-and-cancer/?region=on; cited 11 April 2017] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thorne S, Armstrong EA, Harris SR, et al. Patient real-time and 12-month retrospective perceptions of difficult communications in the cancer diagnostic period. Qual Health Res. 2009;19:1383–94. doi: 10.1177/1049732309348382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walsh D, Nelson KA. Communication of a cancer diagnosis: patients’ perceptions of when they were first told they had cancer. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2003;20:52–6. doi: 10.1177/104990910302000112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.United Kingdom, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (nice) Patient Experience in Adult NHS Services: Improving the Experience of Care for People Using Adult NHS Services. London, U.K.: NICE; 2012. Clinical guideline 138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCormack LA, Treiman K, Rupert D, et al. Measuring patient-centered communication in cancer care: a literature review and the development of a systematic approach. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72:1085–95. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Epstein RM, Street RL., Jr . Patient-Centered Communication in Cancer Care: Promoting Healing and Reducing Suffering. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Payne S, Jarrett N, Jeffs D. The impact of travel on cancer patients’ experiences of treatment: a literature review. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2000;9:197–203. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2354.2000.00225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schofield PE, Butow PN, Thompson JF, Tattersall MH, Beeney LJ, Dunn SM. Psychological responses of patients receiving a diagnosis of cancer. Ann Oncol. 2003;14:48–56. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdg010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schaepe KS. Bad news and first impressions: patient and family caregiver accounts of learning the cancer diagnosis. Soc Sci Med. 2011;73:912–21. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.06.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sainio C, Lauri S, Eriksson E. Cancer patients’ views and experiences of participation in care and decision making. Nurs Ethics. 2001;8:97–113. doi: 10.1177/096973300100800203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Joseph-Williams N, Elwyn G, Edwards A. Knowledge is not power for patients: a systematic review and thematic synthesis of patient-reported barriers and facilitators to shared decision making. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;94:291–309. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2013.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mazor KM, Beard RL, Alexander GL, et al. Patients’ and family members’ views on patient-centered communication during cancer care. Psychooncology. 2013;22:2487–95. doi: 10.1002/pon.3317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thorne S, Oliffe J, Kim-Sing C, et al. Helpful communications during the diagnostic period: an interpretive description of patient preferences. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2010;19:746–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2009.01125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tariman JD, Berry DL, Cochrane B, Doorenbos A, Schepp K. Preferred and actual participation roles during health care decision making in persons with cancer: a systematic review. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:1145–51. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Loughery J, Woodgate RL. Supportive care needs of rural individuals living with cancer: a literature review. Can Oncol Nurs J. 2015;25:157–78. doi: 10.5737/23688076252157166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zucca A, Boyes A, Newling G, Hall A, Girgis A. Travelling all over the countryside: travel-related burden and financial difficulties reported by cancer patients in New South Wales and Victoria. Aust J Rural Health. 2011;19:298–305. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1584.2011.01232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gaston CM, Mitchell G. Information giving and decision-making in patients with advanced cancer: a systematic review. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61:2252–64. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]