Abstract

BACKGROUND

Immunisations are one of the most cost-effective public health interventions available and South Africa (SA) has implemented a comprehensive immunisation schedule. However, there is disagreement about the level of immunisation coverage in the country and few studies document the immunisation coverage in rural areas.

OBJECTIVE

To examine the successful and timely delivery of immunisations to children during the first 2 years of life in a deeply rural part of the Eastern Cape Province ot SA.

METHODS

From January to April 2013, a cohort of sequential births (N=470) in the area surrounding Zithulele Hospital in the OR Tambo District of the Eastern Cape was recruited and followed up at home at 3, 6, 9,12 and 24 months post birth, up to May 2015. Immunisation coverage was determined using Road-to-Health cards.

RESULTS

The percentages of children with all immunisations up to date at the time of interview were: 48.6% at 3 months, 73.3% at 6 months, 83.9% at 9 months, 73.3% at 12 months and 73.2% at 24 months. Incomplete immunisations were attributed to stock-outs (56%), lack of awareness of the immunisation schedule or of missed immunisations by the mother (16%) and lack of clinic attendance by the mother (19%). Of the mothers who had visited the clinic for baby immunisations, 49.8% had to make multiple visits because of stock-outs. Measles coverage (of at least one dose) was 85.2% at 1 year and 96.3% by 2 years, but 20.6% of babies had not received a second measles dose (due at 18 months) by 2 years. Immunisations were often given late, particularly the 14-week immunisations.

CONCLUSIONS

Immunisation rates in the rural Eastern Cape are well below government targets and indicate inadequate provision of basic primary care. Stock-outs of basic childhood immunisations are common and are, according to mothers, the main reason for their childrens immunisations not being up to date. There is still much work to be done to ensure that the basics of disease prevention are being delivered at rural clinics in the Eastern Cape, despite attempts to re-engineer primary healthcare in SA.

Keywords: Immunisation coverage at 1 year, rural South Africa, Primary Health Care (PHC), Re-engineering of Primary Health Care, Eastern Cape, measles coverage, prospective longitudinal cohort study, stock-outs, timeliness of routine childhood immunisations

Introduction

Immunisation coverage of children is a cornerstone of primary health care (PHC) and an important gauge of the quality of the health service in a country,[1] but is also a good indicator of how far a country is from preventable disease outbreaks, such as the measles outbreak that occurred in South Africa in 2010[2].

South Africa’s immunisation schedule has been significantly expanded since 1994, with the recent addition of the pneumococcal (PCV) and rotavirus (RV) vaccines in 2009[3], and is the most comprehensive in Africa [4]. As part of the 2010 “Re-engineering of Primary Health Care” policy, the South African National Department of Health (NDOH) has emphasised the importance of doing the basics of PHC right[5]. However, there has been disagreement about how well the schedule has been implemented on the ground and the NDOH has disputed low WHO/UNICEF immunisation coverage figures [3,6]. After the 2011 census provided revised estimates of the number of children under the age of one year, the NDOH immunisation indicators were adjusted downwards, but were still significantly higher that WHO/UNICEF estimates [4,7].

The quality of NDOH immunisation data gathered through the District Health Information System (DHIS) is poor[6] and apart from one study,[8] there are limited data on immunisation coverage in rural areas of South Africa and to the best of our knowledge nothing about coverage in rural Eastern Cape.

In this study, we assessed immunisation coverage of the South African Expanded Programme of Immunisations (EPI-SA) during the first two years of life and the timeliness of immunisations in the first year of life. The study formed part of the Zithulele Births Follow up Study (ZiBFUS), a prospective, longitudinal cohort study, initiated in January 2013.

Methods

Setting

Zithulele Hospital is a 146-bed district hospital, serving a catchment area with a population of approximately 130 000[9] and fourteen clinics, and is situated in the King Sabata Dalindyebo (KSD) sub-district of the O.R. Tambo District in the Eastern Cape, an NHI pilot district. It is one of the two poorest municipalities in South Africa[10]. There has been a sustained and significant improvement to the quality of healthcare delivered at Zithulele Hospital and its feeder clinics since 2005[9, 11, 12]. Outpatient numbers and in-facility deliveries at Zithulele Hospital tripled between July 2005 and July 2015, whilst peri-natal mortality rates decreased from 42 per 1000 live births to below 20 per 1000, paediatric in-hospital mortality decreased from 10% to 2.5% and more than 5000 patients were started on ARVs *. The hospital clinical team also invested significantly in 10 primary health care feeder clinics, by sending doctors, occupational- and physiotherapists, dentists, dieticians, speech therapists and audiologists to these clinics on a regular rotation. As a result, the level of support received by PHC clinics in the Zithulele Hospital catchment area is better than in most rural areas of South Africa.

Sample

We recruited a cohort at birth from Zithulele Hospital and the area covered by its closest primary health care clinics between 14 January 2013 and 15 April 2013. All women who gave birth at Zithulele Hospital, at one of the ten closest clinics, on the way to a health facility, or at home in the area covered by the clinics during this time period were included in the study. Women who travelled to the hospital from outside this catchment area to give birth at the hospital were excluded, due to lack of resources for regular follow-up. Informed consent was obtained from all women; in cases where a participant was under 18 years of age, informed consent was obtained from her and a parent or guardian as well. Ethical approval was obtained from the Health Research Ethics Committee at Stellenbosch University (N12/08/046) and permission for the recruitment to occur in government health facilities was granted by the Eastern Cape Department of Health through the Office of Epidemiological Research and Surveillance Management.

Most women were recruited from the Maternity Ward of Zithulele Hospital where a field worker (FW) was stationed every day of the week (including weekends). To identify women who gave birth at home or in one of the feeder clinics, the research team relied on nurses at the clinics to identify these cases, and offered nurses a small airtime reimbursement to contact the FWs with the woman’s telephone number. The principal investigator, having previously worked as a medical officer in all of the feeder clinics, had built good relationships with the nurses there over many years. Links were also established with traditional leaders in the community, with the hope that they could help us to identify mothers giving birth at home. The majority of home births were referred to us by nurses at the time of the mother’s first visit to the clinic. We believe that virtually all home births during the recruitment period were identified in this way, due to the strong incentive for mothers to visit a clinic or hospital soon after birth to acquire a Road to Health Card (RtHC) for their baby. Not only is the RtHC a type of health “passport” and an extremely important health record, but it is also used to apply for a child support grant (R250 per month in 2013) from the South African Social Security Agency (SASSA)[13].

Field workers were recruited locally and were trained by experienced facilitators from Stellenbosch University for a period of 6 weeks. Interview techniques, the use of cell phones as a data collection tool, research ethics, and confidentiality were covered, and the birth questionnaire was piloted in the field. For each of the subsequent surveys, in-house training and piloting was performed. Questionnaires were initially written in English, and then translated into isiXhosa by the FWs who are all proficient in English and familiar with the type of isiXhosa spoken in the part of the rural Eastern Cape where the study was performed. Questionnaires were then loaded onto cell phones using the programme Mobenzi Researcher[14], and all data entered into the Mobenzi Researcher platform in the field were checked by the research co-ordinator or on-site principal investigator in the presence of the relevant data capturer within a few days of entry. All interviews were voice-recorded, and an experienced isiXhosa-speaking researcher at Stellenbosch University reviewed a select number of interviews per field worker each month, for further quality control and verification of the data’s accuracy. The project co-ordinator also conducted field visits on a weekly basis for the first year to further ensure the quality of data collected.

Birth interviews were usually performed within one to two days of birth at the hospital, and within 1–2 weeks if the child was born at home or at the clinic. Mother-infant pairs were then followed up at 3, 6, 9, 12 and 24 months. Ninety-two percent of follow-up interviews were conducted at the child’s home, although some were performed at another convenient location for the mother, such as a clinic, trading store or the hospital.

Immunisation status was checked at each follow-up visit, and FWs assessed whether all immunisations that should have been given by the relevant age had indeed been given. (For the immunisations checked at each interview, see Table 2). If a single immunisation was missing, a child’s immunisations were classified as incomplete. If the mother or caregiver gave consent, the FW took a photo of the immunisation page in the RtHC, which allowed for confirmation of the immunisation status at each visit, and also enabled us to assess whether immunisations had been given at the correct time, as the date each immunisation is administered is noted on the card by the clinic nurse.

Table 2.

Follow up and immunisation rates at the 3, 6, 9,12 and 24-month interviews

| 3 months | 6 months | 9 months | 12 months | 24 months | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Follow up rate | 84.7% (390/460) | 92.1% (420/456) | 88.3% (401/454) | 91.3% (411/450) | 88% (396/450) |

| Number of RtHC available at interview | 96.4% (376/390) | 95.7% (401/420) | 91.2% (366/401) | 89.5% (368/411) | 89.4% (354/396) |

| All immunisations up to date at interview (%) | 48.6% (175/360) | 73.3% (294/401) | 83.9% (307/366) | 73.3% (269/367) | 73.2% (259/354) |

| Number of deaths during time period | 10 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 0 |

| Immunisations assessed at interview | Birth, 6wk, 10wk | Birth, 6wk, 10wk, 14wk | Birth, 6wk, 10wk, 14wk | Birth, 6wk, 10wk, 14wk, 9months | Birth, 6wk, 10wk, 14wk, 9monts, 18 months |

Participants who did not have RtHC were not included in the assessment of immunisation status. At the 3- and 6-month interviews, mothers and caregivers who had been to the clinic were asked whether they had been instructed to return after a routine (immunisation) visit due the unavailability of one or more immunisations. Furthermore, if the child’s immunisations were incomplete, mothers and caregivers were asked why this was the case.

Data were analysed using SAS v9.4.

Results

A total of 493 women fulfilled the inclusion criteria. Of this sample, 23 women (5%) refused or were unable to provide informed consent due to intellectual impairment, hearing impairment or psychiatric illness, and were therefore excluded from the study. There were 9 sets of twins, but the second twin was excluded from this analysis and therefore 470 mother-infant pairs were evaluated. The age range of the women was from 14 to 52 and 77 of the women were under 18 years old. The HIV prevalence rate of 28.5% was slightly lower that the prevalence rate of 29.8% for the OR Tambo District in the 2012† National Antenatal Sentinel HIV Prevalence Survey[15].

The women enrolled into the study reflect a poor rural population with little access to municipal services such as electricity and water (Table 1). Whilst 56% had passed grade 9, only 7% had completed 12 years of schooling, 1% had a post-school qualification and nearly 5% of mothers had never attended school. Over 90% of households received some kind of government grant at the time of the birth survey. Less than a fifth of households had access to electricity at baseline, with two-thirds using wood as their primary fuel source. Only 30% had access to a communal water tap, with 48% relying on unsafe river water. At the two-year follow-up, 36% of mothers had access to communal taps, 27% had access to mains electricity, and another 7% had gained access to government-supplied solar panels, indicating a modest extension of municipal services in the area surveyed. The vast majority of births were in a health facility (86%), and of those who delivered at home, only one woman had intended to do so. By 2 years, 34% of the children were being primarily cared for by someone other than their mother, with maternal grandmothers caring for these children in 55% of cases; this shift was mostly due to mothers returning to school or working.

Table 1.

Descriptors of a consecutive series of women giving birth in the rural Eastern Cape and their babies (N = 470)

| Demographic characteristics (mother) | |

| Mean age (SD#) | 24.9 (7.03) |

| Mean highest education level attained (in grade) (SD) | 8.19 (2.98) |

| Median household size before arrival of new baby (IQR*) | 7 (4) |

| Primiparous (%) | 39 |

| HIV positive (%) | 29 |

| Mother lives with father of child (%) | 18 |

| Electricity in home (%) | 16 |

| Water source (%) | |

| River water | 48 |

| Communal tap | 27 |

| Water tank | 16 |

| Well | 9 |

| Employment status (%) | |

| Employed | 4 |

| Schooling | 16 |

| Unemployed | 80 |

| Baby characteristics | |

| Sex – female (%) | 44 |

| Birth-weight mean Z scores (SD) | −0.73 (1.21) |

| Low birth weight (<2500g) (%) | 16 |

| Place born (%) | |

| At home | 10 |

| On way to health facility | 4 |

| At community health centre | 9 |

| At hospital | 77 |

Standard deviation

Interquartile range

Follow-up rates were between 84.7 and 92.1%, and were 88% at 2 years (Table 2). Twelve month follow-up rates were bolstered by the 2014 platinum mining strike, which started in January and lasted five months. During this strike, most men employed in the mines (and also the mother-infant pairs partaking in the study) were back from the North West Province. Twenty-two infants died in the first year, two of which were the second twin and therefore are not included in this analysis. No deaths were recorded the second year of the study.

A high proportion (between 89 and 96 %) of mothers or caregivers had the children’s RtHC available at the interview (see table 2), and at 2 years only 2% reported that the child’s RtHC had been either lost or destroyed. Immunisation rates at the 3-month interview were less than 50%, but this had improved by 6 and 9 months (Table 2). At 12 months, the fully immunised group was again smaller, due to some of the children in the study missing either their Measles Containing Vaccine 1 (MCV 1) or Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine 3 (PCV 3) (or both), which is due at 9 months. MVC 1 had an 85% coverage rate at 1 year and MCV 2 vaccine a 79.4% coverage rate at 2 years. Just less than 4% of children had received neither MCV1 nor MVC2 by the time of the 2-year interview.

Fifty-six percent of women whose children did not have all their immunisations up to date blamed stock-outs at the clinic (51.9 % at 3 months and 62.6% at 6 months), 19% said that they had not gone to the clinic yet, while 16% said that they were unaware of the fact that the immunisations were incomplete. In these cases, some participants went for immunisations and were given one, but not all, of the required immunisations for the relevant date, and were not informed that the immunisations were incomplete; others were simply unaware that they needed to go for further immunisations. By 6 months, 49.8% of women in the study who had gone for immunisations, including those whose children had all immunisations up to date at the time of the interview, reported that they had to return to the clinic for an immunisation that was out of stock at least once.

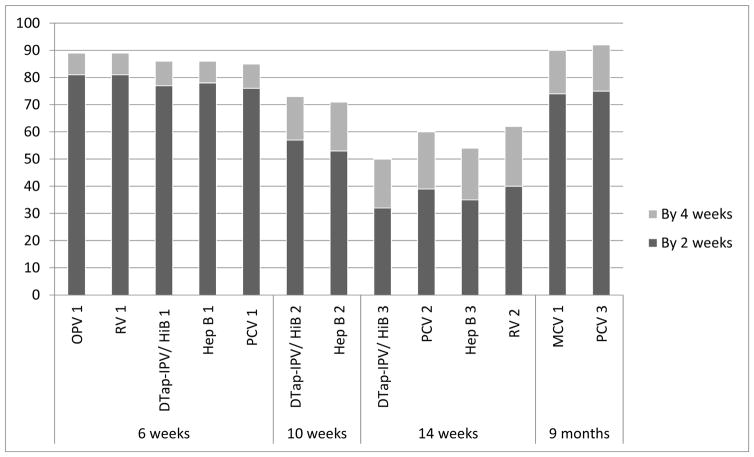

Finally, as can be seen in Figure 1, a significant proportion of immunisations that were given were administered more than two weeks after they were due. This trend was most prominent at 14 weeks, when between 60–68% of the immunisations were given more than two weeks after their due-date, while 50% of DTap-IPV/HiB 3 immunisations were given more than four weeks late.

Figure 1. Of the immunisations that were given, percentage that given on time (within 2 weeks and 4 weeks of expected date) at 6wks, 10wks, 14wk and 9 months.

OPV = Oral Polio Vaccine; RV = Rotavirus Vaccine; DTap-IPV/HiB = Diptheria, Tetanus, acellular Pertussis, Inactivated Polio Vaccine and Haemophylis influenza type B combined; Hep B = Hepatitis B Vaccine; PCV = Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine; MCV = Measles Containing Vaccine.

Discussion

The NDOH has set ambitious targets for immunization rates in the Health Ministry’s “Annual Performance Plan 2014/2015 – 2016/7”, with the stated aim of 95% coverage for immunisations by 1 year and 85% coverage for measles second dose (MCV2)[16]. The Zithulele Births Follow-Up Study (ZiBFUS) demonstrates that in rural areas, clinics are falling short of national targets for immunisation coverage, even in a NHI pilot district with a well-functioning district hospital. The ZiBFUS data shows one-year immunization coverage of 73.3%, in comparison to the target of 95%, and measles 2nd dose coverage of 79.4%, as compared to the 85% target. It is encouraging that 96.3% of babies had received at least one measles immunisation by 2 years. However MCV 1 immunisation coverage still falls well below the NDOH target of 95% at one year, which is also the level required for the development of herd immunity[17]. It is important to note that we were only able to assess immunisation status on children who had Road to Health Cards available. Although RtHC availability was high, 96.4% at 3 months and 89.4% at 24 months – we are probably underestimating immunisation coverage slightly, as children without RtHC are less likely to have been immunised, with clinic nurses requiring these for vaccinations to be given.

As a point of comparison, and not unexpectedly for an underserved rural area, our figures for 1 year immunisation coverage are lower that the NDOH national estimates for 2012/13, which very between 94% (Annual Performance Plan) [16] and 83.4% (2014/15 District Health Barometer)[3]. Interestingly, our figures are higher than WHO/UNICEF national estimates for 2012/3, which indicate that immunisation coverage was at around 69%[7].

In light of the prevention imperative of immunisations and the risk to herd immunity of poor coverage, it is notable that that stock-outs of immunisations had affected nearly 50% of the all the women and children participating in the study by the 6 month interview, necessitating one or more subsequent visits to ensure adequate coverage. Furthermore, 56% of women whose children did not have up-to-date immunisations attributed this to stock-outs, while only 19% of women indicated that they had not yet gone to their clinic for the required routine vaccinations. There may be some reporting bias here, in that women might try to justify their children’s incomplete immunisations by blaming nurses or clinics. However, the fact that 45% of the women who said they had been asked to return to the clinic at least once had children whose immunisations were all up-to-date indicates that stock-outs are not simply being used as an excuse, but that this is indeed an extensive problem. There is a tendency for healthcare workers to blame mothers for incomplete immunisations[18], but our data indicates that nearly three-quarters missed immunisations were due to a health system failure – either a stock-out (56%) or lack of information to women about their baby’s immunisations being incomplete(16%).

Furthermore, the knock-on effect of stock-outs, which delay routine immunisations and therefore cause other scheduled immunisations to also be delayed is well demonstrated, with 38–50% of the 14-week immunisations given more than one month late. This finding, coupled with the difficulty that many mothers have in accessing rural clinics, means that young infants are left potentially vulnerable to dangerous preventable diseases, and resultant malnutrition and developmental delay[19].

Our data cannot be generalised to the whole of South Africa, but gives and indication of the immunisation coverage and timeliness of routine childhood immunisations in poor rural communities. It is clear that, despite South Africa’s impressive immunisation policies and the emphasis on the basics of primary health care under the “Re-engineering of Primary Health Care” strategy, immunisations are not always available to infants in the rural Eastern Cape. This places an unnecessary burden on rural women and their children and puts poor rural communities at risk of preventable disease outbreaks.

Acknowledgments

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. Funding for the study was provided by the ELMA Foundation through a grant to Philani Centers Nutrition Trust. MT is a lead investigator with the Centre of Excellence in Human Development, University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa and is supported by the National Research Foundation, South Africa.

Footnotes

Personal email communication with Dr. C.B. Gaunt, Clinical Manager, Zithulele Hospital, 27 October 2015

76% of women in the study who remembered their antenatal care initiation date, initiated antenatal care in 2012, which is when blood for syphilis and the Sentinel HIV Prevalence Survey would have been taken.

References

- 1.Burton A, Monasch R, Lautenbach B. WHO and UNICEF estimates of national infant immunization coverage: methods and processes. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2009 Jul 1;87(7):535–41. doi: 10.2471/BLT.08.053819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Le Roux DM, Le Roux SM, Nuttall JJ, Eley BS. South African measles outbreak 2009 – 2010 as experienced by a paediatric hospital. South African Medical Journal. 2012 Aug 22;102(9):760–4. doi: 10.7196/samj.5984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bamford L. Immunisations (Chapter 7) In: Massyn N, Peer N, Padarath A, Barron P, Day C, editors. District Health Barometer 2014/15. Durban: Health Systems Trust; Oct, 2015. Available from: http://www.hst.org.za/publications/district-health-barometer-201415-1. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wiysonge CS, Ngcobo NJ, Jeena PM, Madhi SA, Schoub BD, Hawkridge A, et al. Advances in childhood immunisation in South Africa: where to now? Programme managers’ views and evidence from systematic reviews. BMC Public Health. 2012 Jul 31;12:578. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barron P, Shasha W, Schneider H, et al. Discussion document. Department of Health; 2010. Re-engineering of Primary Health Care in South Africa. [cited 2016 Jun 27]. Available from: http://docslide.us/documents/draft-2010-document-on-the-re-engineering-of-primary-health-care-in-south-africa.html. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bateman C. Vaccines: SA’s immunisation programme debunked. South African Medical Journal [Internet] 2016 Mar 17;106(4):318–9. [cited 2016 Jun 27]. Available at http://www.samj.org.za/index.php/samj/article/view/10765. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.UNICEF. Country Statistics: South Africa [Internet] UNICEF; [cited 2016 May 4]. Available from: http://www.unicef.org/infobycountry/southafrica_statistics.html. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fadnes LT, Jackson D, Engebretsen IM, Zembe W, Sanders D, Sommerfelt H, et al. Vaccination coverage and timeliness in three South African areas: a prospective study. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:404. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baleta A. Rural hospital beats the odds in South Africa. The Lancet. 2009 Sep;374(9692):771–2. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61577-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deprivation index shows Alfred Nzo municipality is the worst in SA. [Internet] Business Day Live. 2016 Jun 7; [cited 2016 Jun 27]. Available from: http://www.bdlive.co.za/national/2016/06/07/deprivation-index-shows-alfred-nzo-municipality-is-the-worst-in-sa.

- 11.Gaunt CB. Are we winning? Improving perinatal outcomes at a deeply rural district hospital in South Africa. SAMJ. 2010 Feb;100(2):101–4. doi: 10.7196/samj.3699. Online ISSN 2078-5135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Young C, Gaunt B. Southern African Journal of HIV Medicine. 1. Vol. 15. 2014. Jan, Providing high-quality HIV care in a deeply rural setting - the Zithulele experience; pp. 28–9. [cited 2016 Feb 8] Available from: http://www.scielo.org.za/scielo.php?script=sci_abstract&pid=S2078-67512014000100013&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=en. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Child support grant. South African Government; [Internet]. [cited 2016 Sep 16]. Available from: http://www.gov.za/services/child-care-social-benefits/child-support-grant. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tomlinson M, Solomon W, Singh Y, Doherty T, Chopra M, Ijumba P, et al. The use of mobile phones as a data collection tool: A report from a household survey in South Africa. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making. 2009;9(1):51. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-9-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.The 2012 National Antenatal Sentinel HIV and Herpes Simplex type-2 prevalence Survey. South Africa, National Department of Health; [Last accessed 16 September 2016]. Available from: http://www.hst.org.za/publications/2012-national-antenatal-sentinel-hiv-herpes-simplex-type-2-prevalence-survey. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Department of Health, South Africa. Annual Performance Plan 2014/5–2016/7 - Ministry of Health. 2014. [Cited 2016 April 26]. Available at http://www.hst.org.za/publications/national-department-health-annual-performance-plan-201415-201617.; Fine P, Eames K, Heymann DL. “Herd Immunity”: A Rough Guide. Clin Infect Dis. 2011 Apr 1;52(7):911–6. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guerra FA. Delays in Immunization Have Potentially Serious Health Consequences Pediatr-Drugs. 2007;9:143. doi: 10.2165/00148581-200709030-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Salsberry PJ, Nickel JT, Mitch R. Why Aren’t Preschoolers Immunized? A Comparison of Parents’ and Providers’ Perceptions of the Barriers to Immunizations. Journal of Community Health Nursing. 1993 Dec 1;10(4):213–24. doi: 10.1207/s15327655jchn1004_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]