Introduction

Prostate cancer remains the most commonly diagnosed non-cutaneous malignancy among Canadian men and is the third leading cause of cancer-related death. In 2016, an estimated 21 600 men were diagnosed with prostate cancer and 4000 men died from the disease;1 however, prostate cancer is a heterogeneous disease with a clinical course ranging from indolent to life-threatening.

Identifying and treating men with clinically significant prostate cancer while avoiding the over-diagnosis and over-treatment of indolent disease remains a significant challenge. Several professional associations have developed guidelines on prostate cancer screening and early diagnosis, but there are conflicting recommendations on how best to approach these issues. With recent updates from several large, randomized, prospective trials, as well as the emergence of several new diagnostic tests, the Canadian Urological Association (CUA) has developed these evidence-based recommendations to guide clinicians on prostate cancer screening and early diagnosis for Canadian men. The aim of these recommendations is to provide guidance on the current best prostate cancer screening and early diagnosis practices and to provide information on new and emerging diagnostic modalities.

Evidence synthesis and recommendations development

In order to develop these recommendations, the following questions related to prostate cancer screening and diagnosis were defined, a priori, to guide the specific literature searches and evidence synthesis:

Should Canadian men undergo prostate cancer screening?

At what age should prostate cancer screening begin?

When can prostate cancer screening be stopped?

How frequently should prostate cancer screening be performed?

What diagnostic tests, in addition to prostate-specific antigen (PSA), are available for the early diagnosis of prostate cancer?

The aim of answering the first four questions is to provide guidance on prostate cancer screening in general. The aim of the fifth question is to provide information on additional available tests. Therefore, a different search strategy was used for these questions. For the first four questions, we employed a two-step approach in order to synthesize the best available evidence to develop these recommendations. First, recognizing that several other professional organizations have developed evidence-based guidelines on prostate cancer screening and diagnosis, a complete bibliographic review of existing guidelines on prostate cancer screening and diagnosis was performed. Studies related to questions 1–4 were reviewed at full length. Second, in order to identify studies not captured by existing guidelines, a search of the literature was conducted using MEDLINE to identify articles related to the screening and diagnosis of prostate cancer that were published between January 1, 2016 and February 2, 2017. To identify articles not yet indexed, a search was also performed using PubMed without MEDLINE filters (see Appendix 1 for search strategy). For the fifth question related to additional diagnostic tests beyond PSA, which can potentially aid in the early detection of prostate cancer, a systematic search was performed in a similar fashion with no date restriction for tests not covered by existing guidelines.

Appendix 1.

Search string relating to prostate-specific antigen screening

|

Case series, case reports, non-systematic reviews, editorials, and letters to the editor were excluded and the search strategy was restricted to English language articles. Trained methodologists implemented the specific search strategy and two authors reviewed the titles and abstracts of potential studies to identify their relevance for full-text review. Levels of evidence and grades of recommendation are provided according to the International Consultation on Urologic Diseases modification of the 2009 Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine grading system.2

PSA screening

1. The CUA suggests offering PSA screening to men with a life expectancy greater than 10 years. The decision of whether or not to pursue PSA screening should be based on shared decision-making after the potential benefits and harms associated with screening have been discussed (Level of evidence: 1; Grade of recommendation: B).

Justification

Prostate cancer screening is one of the most controversial issues in urology and preventative medicine. With varying recommendations on PSA screening, no consensus is established among several professional and government organizations (Supplementary Table 1). Many professional associations, including the American Urological Association,3 National Comprehensive Cancer Network,4 European Association of Urology,5 and the American College of Physicians6 recommend offering PSA screening to interested men after a thorough discussion of the benefits and harms. In addition, the United States Preventative Services Task Force (USPSTF) recently recommended a similar shared decision-making approach in men aged 55–69 (currently in draft form at the time of this publication) after previously recommending against screening.7 Conversely, the Canadian Task Force on Preventative Health Care (CTFPHC) weakly recommends against PSA screening in men of any age;8 however, several important updates of large, population-based studies have been released since the time of this task force publication and herein we include a summary of the evidence for and against screening for prostate cancer.

There have been six randomized, controlled trials investigating the role of PSA screening in adult men;9–14 however, three of these studies are at significant risk of bias and are generally not considered when weighing the evidence for or against prostate cancer screening. Thus, three randomized, controlled trials, all with recent updates, constitute the credible Level 1 evidence concerning prostate cancer screening; the Prostate, Lung, Colon, and Ovarian screening trial (PLCO),9 the European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC),10 and the Goteborg randomized trial of PSA screening (Table 1).11

Table 1.

Most recent results from three randomized, controlled trials investigating PSA screening

| PLCO (2017 update)15 | ERSPC (2014 update)16 | Goteborg (2014 update)17 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 76 683 | 162 243 | 20 000 |

|

| |||

| Age | 55–74 | 55–69 | 50–64 |

|

| |||

| Site | 10 US centres | 8 European countries | 1 city (Goteborg, Sweden) |

|

| |||

| Intervention | PSA annually × 6 years Annual DRE × 4 years | PSA q4 years (in most centres) Some centres offered DRE | PSA q2 years |

|

| |||

| Current median followup | 15 years | 13 years | 18 years |

|

| |||

| Definition of positive test | PSA >4 ng/ml Abnormal DRE | PSA>3 ng/ml (most centres) | PSA >2.5 ng/ml (from 2005 on) PSA >2.9 ng/ml (from 1999–2004) PSA>3.4 ng/ml (from 1995–98) |

|

| |||

| Prostate cancer deaths | Control: 244 | Control: 545 | Control: 122 |

| Screened: 255 | Screened: 355 | Screened: 79 | |

|

| |||

| 0.79 (0.69–0.91) | 79 0.58 (0.46–0.72) | ||

| Rate ratio for CSS (95% CI) | 1.04 (0.87–1.24) | 21% relative risk reduction in favour of screening | 42% relative risk reduction in favour of screening |

|

| |||

| NNS | N/A | 1:781 | 1:139 |

| NND | N/A | 1:27 | 1:13 |

CSS: Prostate cancer-specific survival; DRE: digital rectal exam; ERSPC: European

Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer; NNS: number needed to screen; NND: number needed to diagnose; PLCO: Prostate, Lung, Colon, and Ovarian screening trial; PSA: prostate-specific antigen.

The PCLO was a North American trial including 76 683 men aged 55–74 accrued from 10 centres where subjects were randomized to organized screening or standard care.9 In the recently published update, with 15 years of followup, there continues to be no difference in prostate cancer-specific mortality between patients in the intervention (screening) and control arms;15 however, several important limitations may mitigate this finding. Foremost, there was considerable contamination between study arms, with over 80% of subjects in the control arm having at least one PSA measurement during the study period. This high contamination rate biases the result toward finding no difference in mortality from prostate cancer.

The ERSPC study is a collection of randomized trials conducted across eight European countries and includes 162 243 men aged 55–69. While there were some differences between the individual trials, men were randomized to organized PSA screening or standard care.10 With 13 years of followup, there was a 21% relative risk reduction in prostate cancer mortality.16 In terms of absolute risk reduction, this equates to 1.28 less prostate cancer deaths for every 1000 men screened or 781 men undergoing screening and 27 men undergoing treatment to prevent one prostate cancer death. In the Swedish Goteborg study of 20 000 patients aged 50–64 at enrollment, a similar reduction in prostate cancer mortality was seen at up to 18 years of followup, with a relative risk reduction of 42% and 139 patients being invited for screening to prevent one prostate cancer death.17 Although there was also contamination of the control arms in both the ERSPC and Goteborg trials, the estimated proportion of control patients receiving PSA testing is significantly lower than those in the PLCO trial.11,18,19 Overall, based on currently available evidence from randomized, controlled trials, it appears as though organized PSA screening results in a reduction in prostate cancer mortality. To add to these currently available studies, the initial results from the cluster randomized trial of PSA testing for prostate cancer (CAP trial), a large randomized trial including over 400 000 patients in the U.K. randomized to PSA screening or standard care, will likely provide further information on the effects of PSA screening in the near future.20

There is also weaker evidence from epidemiological studies on the effect of PSA screening. Prostate cancer mortality has declined since the introduction of PSA screening in North America.21–23 While we cannot know with certainty why mortality has declined, modelling studies indicate that the most plausible and largest contribution to mortality reduction is from screening.23–27 Additionally, there has been a decrease in the incidence of prostate cancer diagnosis in recent years in the U.S., which is likely a result of decreased screening use.28–30 This has been associated with a stage migration towards higher stage and more frequent metastatic disease.30,31 While more time is required to determine whether this recent stage migration will result in an increase in prostate cancer mortality, we believe that reducing the morbidity of advanced and metastatic prostate cancer is in itself an important outcome. Although these observations were not directly used by the guideline panel when considering recommendation for PSA screening, the underlying risk of under-diagnosis of high-risk disease remains a concern.

Although the available evidence suggests there are benefits to prostate cancer screening in terms of reduction in mortality, there are also significant potentials harms of over-diagnosis and over-treatment. Indeed, up to 67% of men diagnosed with prostate cancer by screening will be identified as having clinically insignificant prostate cancer, which, if never detected, would be unlikely to lead to increased morbidity or mortality.32–36 Thus, if screened, men with insignificant disease may be unnecessarily exposed to the potential harms of both prostate biopsy and treatment in addition to the psychological effects accompanying a prostate cancer diagnosis. The increased use of active surveillance for low-risk prostate cancer in Canada has been an important step in reducing the over-treatment of prostate cancer; however, active surveillance does not eliminate the issue of over-diagnosis and itself is associated with significant potential detriments to quality of life.37 With these risks in mind, it is imperative that we not only separate the diagnosis of prostate cancer from the treatment of prostate cancer, but that we institute improved screening and early detection practices to decrease the risk of detecting clinically insignificant disease.

The CUA recognizes that PSA screening may not be the best option for all men. Balancing the known benefits and risks of PSA screening is difficult and is significantly influenced by personal values. As such, the decision of whether or not to undergo prostate cancer screening is, and will likely remain, an individualized decision. In order to reach this decision, the CUA recommends that healthcare providers engage in a thorough discussion on the potential risks and benefits of PSA screening with their patients and that shared decision-making be performed.

Best screening practices

When prostate cancer screening is performed, the overarching goal should be the early detection of clinically significant prostate cancer in healthy men while minimizing the detection and treatment of low-risk disease. Screening studies are challenging to conduct because of the large numbers of participants required, risk of contamination, loss to followup, and many other pitfalls. It is not feasible to evaluate most questions regarding timing and administration of PSA directly. In this context, the CUA provides the following recommendations based upon the inclusion criteria of randomized trials and high-quality observational studies to encourage “smart” screening. Our aims are to maintain benefits and mitigate potential harms associated with screening.

2. For men electing to undergo PSA screening, we suggest starting PSA testing at age 50 in most men and at age 45 in men at an increased risk of prostate cancer (Level of evidence: 3; Grade of recommendation: C).

Justification

Although the optimal age for starting PSA screening has not been vigorously studied, our recommendation for starting PSA screening at age 50 comes from the Goteborg trial, which provides randomized data on the benefits of screening in men starting at this age;11 however, evidence from observational studies suggests that certain men may benefit from PSA screening at an earlier age, with a nearly 5% risk of developing lethal prostate cancer within 15 years for men aged 45–49 with a PSA >4 ng/ml.38,39 Although it remains unclear which men will benefit from early PSA screening, family history imparts a substantially increased risk of prostate cancer diagnosis at a younger age. Particularly, men aged <50 with a family history of prostate cancer in a first- or second-degree relative have an approximately five-fold and two-fold increased risk of receiving a prostate cancer diagnosis, respectively.38

The potential benefits and harms of PSA screening for men less than age 45 has not been prospectively studied; however, a recently published case-control study nested within the Physicians Health Study cohort identified that the risk of developing metastatic prostate cancer within 15 years among men in this age group was very low, even among men with PSA levels in the top decile.38 Thus, PSA testing in these men may lead to biopsies and diagnoses that are unlikely to provide benefit. The potential delay in diagnosis in the small proportion of men at this age with clinically significant prostate cancer seems unlikely to lead to a missed opportunity for curative treatment.

These recommendations are not directed towards men with known germ-line mutations associated with prostate cancer development (e.g., BRCA1, BRCA2, HOXB13). In these cases, an individualized testing strategy after consultation with a clinical geneticist is most appropriate.

-

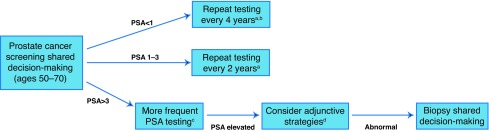

3. For men electing to undergo PSA screening, we suggest that the intervals between testing should be individualized based on previous PSA levels (Fig. 1).

For men with PSA <1 ng/ml, repeat PSA testing every four years (Level of evidence: 3; Grade of recommendation: C).

For men with PSA 1–3 ng/ml, repeat PSA testing every two years (Level of evidence: 3; Grade of recommendation: C).

For men with PSA >3 ng/ml, consider more frequent PSA testing intervals or adjunctive testing strategies (Level of evidence: 4; Grade of recommendation: C).

Fig. 1.

Prostate cancer screening pathway. aDiscontinue screening if life expectancy <10 years; bconsider discontinuation of screening if age >60 and PSA <1 ng/ml; cmore frequent testing interval can be considered; the optimal frequency is unknown; di.e., risk calculators, % free PSA, etc. PSA: prostate-specific antigen.

Justification

Although the frequency at which PSA screening should be performed has not been rigorously studied to date, we can extrapolate from the existing clinical trials and observational studies to provide some guidance on this issue. In particular, men in the screening arms of the ERSPC trial and Goteborg trial underwent testing at intervals of four and two years, respectively, providing the basis for our recommendations.

For men with a PSA level <1ng/ml, longer intervals between PSA testing are appropriate. Indeed, a large prospective cohort study including men undergoing annual PSA screening identified that men with a PSA <1 ng/ml had a 10-year prostate cancer detection rate of only 3.4%, of which 90% were considered low-risk.40 Furthermore, the nested case-control study referenced above identified that the risk of developing metastatic disease within 15 years for a man of any age with PSA <1 ng/ml is very low.39 As such, allowing a longer interval between PSA testing for these men is unlikely to result in an increase in prostate cancer morbidity or mortality and will potentially reduce the risk of over-detection as a result of lead-time bias or natural fluctuations in PSA levels.

On the other hand, as baseline PSA levels rise above 1 ng/ml, the intermediate-term risk of developing both any prostate cancer and clinically significant prostate cancer increases substantially.39–41 As such, we recommend that these men, if electing PSA screening, should undergo testing every two years. The ERSPC trial considered a positive test to be a PSA level of 3 ng/ml, while the Goteborg trial considered a positive test to be between 2.5 and 3.4 ng/ml (depending on the year of study). Thus, the optimal frequency of PSA testing in men above these levels is unknown. For men with PSA >3 ng/ml, more frequent PSA testing intervals can be considered. In addition, adjunctive testing strategies that estimate the risk of clinically significant disease may be helpful for biopsy decision-making in these men (see below).

-

4. For men electing to undergo PSA screening, we suggest that the age at which to discontinue PSA screening should be based on current PSA level and life expectancy.

For men aged 60 with a PSA <1 ng/ml, consider discontinuing PSA screening (Level of evidence: 2; Grade of recommendation: C).

For all other men, discontinue PSA screening at age 70 (Level of evidence: 2; Grade of recommendation: C).

For men with a life expectancy less than 10 years, discontinue PSA screening (Level of evidence: 4; Grade of recommendation: C).

Justification

For men at age 60 with a PSA level <1 ng/ml, the risk of developing or dying from metastatic prostate cancer is low.39,42,43 In a large, population-based study comparing two cohorts of men (one screened and one unscreened), the 15-year cumulative incidence of metastatic prostate cancer was low in both cohorts among men with a PSA <1ng/ml at age 60 (0.4% and 0%, respectively).42 In addition, a case-control study nested within the unscreened cohort found that the risk of being diagnosed with metastatic prostate cancer by age 85 was 0.5% for men with a PSA <1 ng/ml at age 60.43 In contrast, for men at this age with a PSA above 1 ng/ml, the risk of developing potentially lethal prostate cancer increases substantially according to PSA level and thus screening can reasonably be continued.

Men at age >70 have the highest incidence of prostate cancer over-diagnosis and several studies have suggested that screening in this age group is likely not beneficial.16,27,44 Indeed, a large population-based study identified that the risk of prostate cancer over-diagnosis increases substantially with age and is highest in men greater than age 70. Additionally, the ERSPC trial identified that starting screening at age >70 did not result in a reduction in prostate cancer mortality.16 Furthermore, a well-performed modelling study using data from the ERSPC found that any potential benefit to screening in men over 70 was offset by the detriments to quality of life.27 Thus, we recommend that PSA testing in asymptomatic men be discontinued at age 70; however, for interested men in excellent health at age 70, PSA testing can be considered, recognizing the lack of empirical data in this age group. As such, for these men, continued PSA testing is a matter of clinical judgment and personal preferences.

For men with a high risk of mortality from competing causes, PSA testing is unlikely to provide benefit.45 The CUA recognizes that estimating life expectancy is challenging.46 Nonetheless, it is recommended that physicians take into account a patient’s general health status and competing risks of mortality when considering whether or not to offer PSA testing. If life expectancy is limited by other serious illnesses or comorbidities, PSA screening should not be initiated or can be discontinued.

Adjunctive strategies for improving prostate cancer early diagnosis

The past two decades have seen the development or evaluation of several potential adjunctive measures that may increase the benefits or reduce the harms associated with screening in addition to PSA. Specifically, PSA kinetics, PSA density, percent free PSA, biomarker panels, and prostate risk calculators may help select patients at higher or lower risk of significant cancer. The refinement of prostate multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging (mpMRI) may also benefit selected individuals. Below we provide a summary of the most commonly used modalities currently available.

mpMRI

Recently, Cancer Care Ontario (CCO) published recommendations on the use of mpMRI in the initial diagnosis of prostate cancer based on a systematic review of the literature.47 The CUA endorses these guidelines and their recommendations are summarized below.

5a. In patients with an elevated risk of clinically significant prostate cancer (according to PSA levels and/ or nomograms) who are biopsy-naive, mpMRI followed by targeted biopsy (biopsy directed at cancer-suspicious foci detected with mpMRI) should not be considered the standard of care.

Qualifying statement

The CCO guidelines panel identified that there is limited evidence on the utility of mpMRI in the biopsy-naive setting and that the studies that do exist are of poor- to moderate-quality. In addition, they found that the currently available studies indicate that that the diagnostic characteristics of mpMRI in this setting are poor to moderate (particular with regards to specificity and positive predictive value).

Since the publication of the CCO guidelines, an additional large, multicentre, prospective cohort study has been published evaluating the diagnostic utility of mpMRI in men at risk for prostate cancer.48 The PROMIS study compared the accuracy of mpMRI with transrectal ultrasound (TRUS) biopsy to determine the utility of mpMRI as a triage test to decide which men with an elevated PSA may be able to avoid biopsy. In total, 576 men with a clinical suspicion of prostate cancer (PSA ≤15 ng/ml) underwent mpMRI followed by TRUS and template prostate mapping biopsy. Overall, mpMRI displayed a moderate sensitivity and negative predictive value for predicting Gleason ≥3+4 disease (88% and 76%, respectively), but the specificity and positive predictive value were poor (45% and 65%, respectively). Overall, we believe that the results of this study do not modify the conclusions of the CCO, and the CUA guidelines committee agrees with the recommendation that mpMRI should not be routinely used in the biopsy-naive setting.

5b. In men who had a prior negative TRUS-guided systematic biopsy who demonstrate an increasing risk of having clinically significant prostate cancer since prior biopsy (e.g., continued rise in PSA and/ or change in findings from digital rectal examination [DRE]), mpMRI followed by targeted biopsy may be considered to help in detecting more clinically significant prostate cancer patients compared with repeated TRUS-guided systematic biopsy.

Qualifying statement

The CCO guidelines panel identified that patients with a prior negative TRUS-guided systematic biopsy who demonstrate increasing risk of clinically significant prostate cancer may benefit from undergoing mpMRI prior to repeat biopsy. Although the quality of evidence again ranged from poor to moderate, a persistent trend emerged showing that mpMRI followed by targeted biopsy detects a higher number of clinically significant prostate cancers relative to repeat systematic TRUS biopsy alone. Thus, we agree with the CCO that mpMRI can be considered prior to undergoing repeat prostate biopsy; however, the CUA acknowledges that there may be practical limitations to this approach, such as timely access to MRI and variations in quality and interpretation.

PSA kinetics

Annual PSA velocity (PSAV) or PSA doubling time (PSADT) can be established from serial measurements of PSA over time. Historical reports have identified that a PSAV greater than 0.75ng/ml/year may indicate an increased risk of prostate cancer.49 Additionally, data from longitudinal studies have illustrated that PSAV greater than 0.35ng/ml/year (when total PSA is <4.0 ng/ml) is associated with a higher relative risk of prostate cancer death,50 suggesting that PSAV can be used as potential prognostic marker for aggressive disease; however, other studies, including a large systematic review of 64 articles, identified that there is conflicting evidence on the incremental value of PSAV over absolute PSA level alone.51–53 It is clear that a sustained and substantial rise in PSA over time is a concerning finding and warrants investigation. Furthermore, a stable or declining PSA is reassuring in men with PSA levels that slightly exceed PSA thresholds. The CUA does not recommend using PSAV alone for clinical decision-making in men undergoing routine screening; however, PSAV can provide additional information about a patient’s risk of prostate cancer.

PSA density

PSA density (PSAD) is the serum PSA divided by prostate volume. A PSAD threshold of >0.15 ng/ml/cm3 has been suggested to distinguish men at risk from prostate cancer, and studies have also linked higher PSAD with adverse pathological features at the time of prostatectomy;54,55 however, others have failed to validate these findings.56,57 Substantial inter-observer variability from the estimation of prostate volume on ultrasound also raises further questions regarding the reliability of PSAD.58,59 Due to the lack of empirical validation, the use of PSAD alone for clinical decision-making is discouraged; however, use of PSAD can be considered adjunctively in men with known prostate volumes.

Percent free PSA

The measurement of percent free PSA has been studied as a risk-stratifying tool aimed at distinguishing men at risk from prostate cancer vs. those with elevations in PSA from benign causes. Several studies have illustrated the potential utility of percent free PSA for identifying men with disease.60–64 In a large, multicentre, prospective study, prostate cancer (all grades) was detected in 56% of men with a free-to-total PSA ratio of less than 0.10 (for men with a PSA between 4 and 10 ng/ml), whereas cancer was detected in 8% of men with a ratio greater than 0.25.65 In a recent publication, a total of 6982 percent free and total PSA measurements were obtained over a 12-year time span from a single institution. Percent free PSA used as a reflex marker demonstrated high levels of performance, with the capability of sparing 66% of unnecessary prostate biopsies.66 Additionally, it was identified that similar to PSA, percent free PSA can also fluctuate, therefore stressing the need for repeat confirmatory testing prior to clinical decision-making. The use of percent free PSA alone for clinical decision-making is not recommended; however, percent free PSA can be useful in estimating the risk of underlying disease in men with elevations in PSA (Level of evidence: 2; Grade of recommendation : C).

Biomarkers

1. Four-kallikrein panel (4Kscore®)

The four-kallikrein panel, or 4Kscore is a commercially available test combining total PSA, free PSA, intact PSA, and human kallikrein 2 with age, DRE results, and prior biopsy status in order to generate a risk estimate of harbouring Gleason ≥7 disease. Originally developed using data from the ERSPC and the Prostate Testing for Cancer and Treatment (ProtecT) studies,67–69 there is evidence of clinical utility over PSA alone for predicting the presence of high-grade prostate cancer. The test has been validated in several subsequent studies evaluating previously screened men, unscreened men, and men with a prior negative biopsy67,68,70–73 (area under the curve [AUC] of 0.71–0.82). The 4Kscore was also validated in a large, prospective study of 1012 men from 26 different centres in the U.S.74 The 4Kscore demonstrated a better discrimination in predicting Gleason ≥7 cancer compared to the modified Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial Risk Calculator 2.0 model (AUC 0.82 vs. 0.74; p<0.0001).

The potential clinical impact of the 4K on biopsy decision-making has also been assessed. The test influenced biopsy decision-making in 89% of men and reduced biopsies by 65% in 611 men that were evaluated by both academic and community urologists.75 Originally developed for use in men with a PSA <10 ng/ml, its use has also been extended and validated in men with a PSA up to 25ng/ml.76

2. Prostate Health Index (PHI®)

The Prostate Health Index (PHI) is a commercially available test derived from PSA and its isoforms (total PSA, free PSA, and [−2] pro PSA) originally developed to estimate the risk of harbouring Gleason 7 or greater disease in men with a PSA between 2 and 10 ng/ml.77 Use of the test was initially validated in a multi-institutional, prospective trial evaluating 892 men for the presence of Gleason ≥4+3 prostate cancer, which found that PHI could improve the discrimination of patients with or without clinically significant disease compared with PSA and free-to-total PSA (AUC 0.72 vs. 0.67).78 Subsequent validation studies have confirmed this finding, showing that PHI can outperform total and percent free PSA in predicting high-risk disease, including in biopsy-naive men.79,80 Additionally, in a large, multicentre, prospective study, PHI significantly improved the performance of the PCPT and ERSPC risk calculators (see below) in men with a PSA between 2 and 10 ng/ml for predicting the risk of Gleason ≥7 prostate cancer.81 A multicentre cohort study evaluating the clinical utility of PHI found that it reduced unnecessary biopsies by 36% and only missed 2.5% of high-grade cancers.80

When comparing PHI and the 4K score, the two tests appear to demonstrate similar discriminatory ability in predicting high-risk prostate cancer in men with a PSA between 3 and 15 ng/ml (AUC 4Kscore 0.718 vs. PHI 0.711).82

3. Prostate cancer antigen 3 (PCA3) score

Prostate cancer antigen 3 (PCA3) is a non-coding RNA gene that is only expressed in the prostate and is overexpressed in prostate cancer. Unlike the 4Kscore and PHI, which are based on serum measurements, PCA3 is measured from a urine sample that is obtained after DRE.

Multiple studies evaluating the PCA3 in men undergoing repeat biopsy have demonstrated an improved diagnostic accuracy for prostate cancer detection relative to PSA alone.83–86 In a multicentre, prospective study of 466 men with a history of a negative biopsy, those with a score of less than 25 were almost five times more likely to have a negative repeat biopsy compared to those with a score ≥25;86 however, the role of PCA3 in men with no history of a prior biopsy is uncertain. In a prospective validation study conducted by the National Cancer Institute, the performance of PCA3 was assessed in 859 men that were enrolled from 11 centres.87 In the biopsy-naive setting, there was a high rate of undiagnosed high-grade cancers (13%) using a PCA3 score <20, compared to 3% in the repeat setting.87

In men with a moderately elevated PSA, the 4Kscore, PHI, and PCA3 may improve the prediction of clinically significant prostate cancer and provide additional information over PSA alone; however, the CUA recognizes that these are expensive tests that are not currently publicly funded in Canada. At the present time, based upon the available data, the CUA does not encourage the widespread use of these tests.

Prostate risk calculators

Several prostate cancer risk nomograms have been developed to aid in the detection of clinically significant prostate cancer.88 One well-performed systematic review and meta-analysis has examined the diagnostic accuracy of multiple prostate cancer risk nomograms;88 however, most of the available nomograms remained untested or inadequately validated. In the six nomograms with adequate validation across several study populations, the discrimination properties for prostate cancer detection were moderate (AUC 0.66–0.79) and most did not assess calibration.88 In addition, most nomograms were not validated for the prediction of clinically significant disease.

Currently, the most widely used calculators for the prediction of clinically significant disease include the PCPT prostate cancer risk calculator (PCPT-RC)89,90 and the ERSPC prostate cancer risk calculator (ERSPC-RC).91 The PCPT-RC uses clinical factors, including age, PSA level, ethnic background, family history, DRE results, and prior biopsy results in order to estimate the risk of both low-risk and high-risk (biopsy Gleason ≥7) prostate cancer, separately. Similarly, the ERSPC-RC uses PSA level, DRE results, prior biopsy results, prostate volume, and TRUS findings in order to determine the risk of both any prostate cancer and clinically significant prostate cancer (pT stage >T2b and/or biopsy Gleason ≥7). In addition, there is a prostate risk calculator that was developed using data from Canadian men.92 This calculator uses PSA level, free-to-total PSA, age, voiding symptoms, ethnicity, family history, and DRE results in order to estimate the risk of both any prostate cancer and high-risk (Gleason ≥7) prostate cancer. Although all of these calculators can be used to estimate the risk of harbouring clinically significant prostate cancer prior to prostate biopsy, they again display only moderate predictive accuracy, which varies across different study populations.88,93–96 Nonetheless, their online availability, ease of use, and improvement upon PSA alone make them attractive adjuncts when counselling patients considering undergoing prostate biopsy. Thus, prostate risk calculators can be used to estimate the risk of clinically significant prostate cancer in men presenting with an elevated PSA.

Prostate biopsy decision-making

Determining the threshold for performing a prostate biopsy should be an individualized process. Although various single PSA thresholds, as well as age-97–99 and race-specific97,100 PSA thresholds have been proposed for biopsy decision-making, no uniform cutoff for PSA can be recommended for all men. Additionally, a single PSA measurement should not be used to guide biopsy decision-making. Numerous studies have documented the measured changes and fluctuations in PSA levels over time.101,102 In a Canadian study that evaluated over 1000 men with elevated PSA (>4 ng/ml), it was demonstrated that by repeating PSA testing, 25% of the cohort had resolution to low levels that did not require further investigation.102 For these reasons, it is recommended that PSA should be repeated and confirmed before proceeding to prostate biopsy.

The decision to proceed with prostate biopsy should take into account several factors, including PSA level, results from adjunct tests or risk calculators, competing comorbidities, and patient preferences. In addition, a suspicious finding on DRE may warrant consideration of prostate biopsy in healthy men. Although the added utility of DRE in addition to PSA is controversial, DRE may increase the detection of clinically significant disease103–105 and men undergoing prostate cancer screening should have DRE performed at the same interval as PSA testing.

The CUA acknowledges that the implementation of a successful screening program must also consider individual variations in patient preferences. Men undergoing screening should be involved in the decision-making regarding prostate biopsy. The decision to pursue biopsy should be based upon a discussion of the best evidence for estimating the risk for aggressive prostate cancer (Expert opinion).

Conclusion

Population-based screening has demonstrated benefits in reducing prostate cancer mortality; however, decisions to proceed with screening should be based upon shared decision-making, recognizing that each patient has a different perspective with regards to the potential benefits and harms of prostate cancer screening and treatment. These recommendations summarize the best available evidence for conducting prostate cancer screening in a Canadian context, with an emphasis placed on maximizing the detection of aggressive and potentially lethal disease and minimizing the harms associated with unnecessary prostate biopsy and discovery of clinically insignificant prostate cancer. We hope that these recommendations will help promote initiatives for improving the health of Canadian men.

Supplementary materials

Supplementary Table 1.

Prostate cancer screening guidelines by other organizations

| Association (year) | Age (years) | Screening recommended (yes/no) | Additional details on recommendations | Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| United States Preventative Services Task Force (Recommendation Statement)a (2017)7 | 55–69 | Yesb |

|

NR |

|

| ||||

| ≥70 | No |

|

NR | |

|

| ||||

| European Association of Urology (2016)5 | >50 |

|

|

|

| >45 if at elevated riskc,d | Yesb | |||

|

| ||||

| <15 years life expectancy | No |

|

NA | |

|

| ||||

| National Comprehensive Cancer Network (2016)4 | 45–75 | Yesb |

|

|

| >75 | Yesj | |||

|

| ||||

| Canadian Task Force on Preventative Health (2014)8 | <55 | No | Based on:

|

NR |

|

| ||||

| 55–69 | No | This recommendation places:

|

NR | |

| ≥70 | No | This recommendation reflects:

|

NR | |

|

| ||||

| American Urological Association (2013)3 | <40 | No |

|

NR |

|

|

||||

| 40–54 | Yesb |

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| 55–69 | Yesb |

|

||

|

|

||||

| ≥70 | No |

|

NR | |

|

| ||||

| American College of Physicians (2013)6 | <50 | No |

|

|

|

| ||||

| 50–69 | Yesb | ACP recommends that clinicians:

|

||

|

| ||||

| ≥70 | No |

|

||

Draft recommendation statement was available for public comment until May 8, 2017; final statement in development;

on case-by-case basis after discussion of risks and benefits;

African-American men and/or family history of prostate cancer;

men with prior PSA assessment and a PSA level of >1 ng/mL at 40 years of age or >2 ng/mL at 60 years of age;

including prior PSA and/ or isoforms, exams, and biopsies;

African-American men have a higher incidence of prostate cancer, increased prostate cancer mortality, and earlier age of diagnosis compared to Caucasian-American men; however, the effects of earlier or more intensive screening on cancer outcomes and on screening-related harms in African-American men remain unclear. Although they may require a higher level of vigilance and different considerations when analyzing the results of screening tests, current data do not support separate screening recommendations for African-American men;

the best evidence supports the use of serum PSA for the early detection of prostate cancer. DRE should not be used as a stand-alone test, but should be performed in those with an elevated serum PSA. DRE may be considered as a baseline test in all patients as it may identify high-grade cancers associated with “normal” serum PSA values. Consider referral for biopsy if DRE is very suspicious. Medications such as 5α-reductase inhibitors (finasteride and dutasteride) are known to decrease PSA by approximately 50%, and PSA values in these men should be corrected accordingly;

men age ≥60 years with serum PSA <1.0 ng/mL have a very low risk of metastases or death due to prostate cancer and may not benefit from further testing. A PSA cut point of 3.0 ng/mL at age 75 years also low risk of poor outcome;

the reported median PSA values for men aged 40–49 years range from 0.5–0.7 ng/mL, and the 75th percentile values range from 0.7–0.9 ng/mL. Therefore, the PSA value of 1.0 ng/mL selects for the upper range of PSA values. Men who have a PSA above the median for their age group are at a higher risk for prostate cancer and for the aggressive form of the disease. The higher above the median, the greater the risk;

testing above the age of 75 years should be done with caution and only in very healthy men with little or no comorbidity, as a large proportion may harbour cancer that would be unlikely to affect their life expectancy, and screening in this population would substantially increase rates of over-detection; however, a clinically significant number of men in this age group may present with high-risk cancers that pose a significant risk if left undetected until signs or symptoms develop. One could consider increasing the PSA threshold for biopsy in this group (i.e., >4 ng/mL). Very few men above the age of 75 years benefit from PSA testing. ACP: American College of Physicians; BRCA1/2: breast cancer type 1/2 susceptibility gene; DRE: digital rectal exam; NA: not applicable; NR: not reported; PSA: prostate-specific antigen.

Footnotes

See related editorial on page 295

Competing interests: The authors report no competing personal or financial interests.

This paper has been peer-reviewed.

References

- 1.Canadian Cancer Statistics 2015. Canadian Cancer Society; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abrams P, Khoury S. International Consultation on Urological Diseases: Evidence-based medicine overview of the main steps for developing and grading guideline recommendations. Neurourol Urodyn. 2010;29:116–8. doi: 10.1002/nau.20845. https://doi.org/10.1002/nau.20845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carter HB, Albertsen PC, Barry MJ, et al. Early detection of prostate cancer: AUA guideline. J Urol. 2013;190:419–26. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.04.119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2013.04.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Prostate Cancer Early Detection, Version 2.2016. Apr 28, 2016. [Accessed May 9, 2017]. Available at https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/prostate_detection.pdf.

- 5.Mottet N, Bellmunt J, Bolla M, et al. EAU-ESTRO-SIOG guidelines on prostate cancer. Part 1: Screening, diagnosis, and local treatment with curative intent. Eur Urol. 2017;71:618–29. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2016.08.003. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2016.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Qaseem A, Barry MJ, Denberg TD, et al. Screening for prostate cancer: A guidance statement from the Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Annals Int Med. 2013;158:761–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-10-201305210-00633. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-158-10-201305210-00633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.United States Preventative Services Task Force. Draft recommendation statement on prostate cancer screening. [Accessed May 9, 2017]. Available at https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementDraft/prostate-cancer-screening1.

- 8.Bell N, Connor Gorber S, Shane A, et al. Recommendations on screening for prostate cancer with the prostate-specific antigen test. Can Med Assoc J. 2014;186:1225–34. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.140703. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.140703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andriole GL, Crawford ED, Grubb RL, 3rd, et al. Mortality results from a randomized prostate-cancer screening trial. N Eng J Med. 2009;360:1310–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810696. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0810696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schroder FH, Hugosson J, Roobol MJ, et al. Screening and prostate-cancer mortality in a randomized European study. N Eng J Med. 2009;360:1320–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810084. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0810084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hugosson J, Carlsson S, Aus G, et al. Mortality results from the Goteborg randomized, population-based prostate-cancer screening trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:725–32. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70146-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70146-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kjellman A, Akre O, Norming U, et al. 15-year followup of a population-based prostate cancer screening study. J Urol. 2009;181:1615–21. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.11.115. discussion 21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2008.11.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Labrie F, Candas B, Cusan L, et al. Screening decreases prostate cancer mortality: 11-year followup of the 1988 Quebec prospective, randomized, controlled trial. Prostate. 2004;59:311–8. doi: 10.1002/pros.20017. https://doi.org/10.1002/pros.20017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sandblom G, Varenhorst E, Rosell J, et al. Randomized prostate cancer screening trial: 20-year followup. BMJ. 2011;342:d1539. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d1539. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d1539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pinsky PF, Prorok PC, Yu K, et al. Extended mortality results for prostate cancer screening in the PLCO trial with median followup of 15 years. Cancer. 2017;123:592–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30474. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.30474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schroder FH, Hugosson J, Roobol MJ, et al. Screening and prostate cancer mortality: Results of the European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC) at 13 years of followup. Lancet. 2014;384:2027–35. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60525-0. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60525-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arnsrud Godtman R, Holmberg E, Lilja H, et al. Opportunistic testing vs. organized prostate-specific antigen screening: Outcome after 18 years in the Goteborg randomized, population-based prostate cancer screening trial. Eur Urol. 2015;68:354–60. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.12.006. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2014.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Otto SJ, van der Cruijsen IW, Liem MK, et al. Effective PSA contamination in the Rotterdam section of the European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer. Int J Cancer. 2003;105:394–9. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11074. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.11074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lujan M, Paez A, Pascual C, et al. Extent of prostate-specific antigen contamination in the Spanish section of the European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC) Eur Urol. 2006;50:1234–40. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2006.04.015. discussion 9–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2006.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Turner EL, Metcalfe C, Donovan JL, et al. Design and preliminary recruitment results of the Cluster randomized triAl of PSA testing for Prostate cancer (CAP) Br J Cancer. 2014;110:2829–36. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.242. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2014.242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bartsch G, Horninger W, Klocker H, et al. Prostate cancer mortality after introduction of prostate-specific antigen mass screening in the Federal State of Tyrol, Austria. Urology. 2001;58:417–24. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(01)01264-x. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0090-4295(01)01264-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roberts RO, Bergstralh EJ, Katusic SK, et al. Decline in prostate cancer mortality from 1980 to 1997, and an update on incidence trends in Olmsted County, Minnesota. J Urol. 1999;161:529–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-5347(01)61941-4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Collin SM, Martin RM, Metcalfe C, et al. Prostate-cancer mortality in the USA and UK in 1975–2004: An ecological study. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:445–52. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70104-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70104-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oliver SE, Gunnell D, Donovan JL. Comparison of trends in prostate-cancer mortality in England and Wales and the USA. Lancet. 2000;355:1788–9. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02269-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02269-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Etzioni R, Tsodikov A, Mariotto A, et al. Quantifying the role of PSA screening in the US prostate cancer mortality decline. Cancer Causes Control. 2008;19:175–81. doi: 10.1007/s10552-007-9083-8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-007-9083-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gulati R, Gore JL, Etzioni R. Comparative effectiveness of alternative prostate-specific antigen-based prostate cancer screening strategies: Model estimates of potential benefits and harms. Annals Int Med. 2013;158:145–53. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-3-201302050-00003. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-158-3-201302050-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heijnsdijk EA, Wever EM, Auvinen A, et al. Quality-of-life effects of prostate-specific antigen screening. N Eng J Med. 2012;367:595–605. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1201637. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1201637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bhindi B, Mamdani M, Kulkarni GS, et al. Impact of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendations against prostate-specific antigen screening on prostate biopsy and cancer detection rates. J Urol. 2015;193:1519–24. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2014.11.096. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2014.11.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barocas DA, Mallin K, Graves AJ, et al. Effect of the USPSTF Grade D recommendation against screening for prostate cancer on incident prostate cancer diagnoses in the United States. J Urol. 2015;194:1587–93. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2015.06.075. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2015.06.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hoffman RM, Meisner AL, Arap W, et al. Trends in United States prostate cancer incidence rates by age and stage, 1995–2012. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016;25:259–63. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0723. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hu JC, Nguyen P, Mao J, et al. Increase in prostate cancer distant metastases at diagnosis in the United States. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:705–7. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.5465. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.5465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Epstein JI, Walsh PC, Carmichael M, et al. Pathological and clinical findings to predict tumor extent of nonpalpable (stage T1c) prostate cancer. JAMA. 1994;271:368–74. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1994.03510290050036. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Etzioni R, Penson DF, Legler JM, et al. Overdiagnosis due to prostate-specific antigen screening: Lessons from U.S. prostate cancer incidence trends. J Nat Canc Inst. 2002;94:981–90. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.13.981. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/94.13.981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Draisma G, Boer R, Otto SJ, et al. Lead times and overdetection due to prostate-specific antigen screening: Estimates from the European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer. J Nat Canc Inst. 2003;95:868–78. doi: 10.1093/jnci/95.12.868. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/95.12.868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Loeb S, Bjurlin MA, Nicholson J, et al. Overdiagnosis and overtreatment of prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2014;65:1046–55. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.12.062. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2013.12.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wever EM, Draisma G, Heijnsdijk EA, et al. Prostate-specific antigen screening in the United States vs. in the European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer-Rotterdam. J Nat Canc Inst. 2010;102:352–5. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp533. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djp533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Latini DM, Hart SL, Knight SJ, et al. The relationship between anxiety and time to treatment for patients with prostate cancer on surveillance. J Urol. 2007;178:826–31. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.05.039. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2007.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Albright F, Stephenson RA, Agarwal N, et al. Prostate cancer risk prediction based on complete prostate cancer family history. Prostate. 2015;75:390–8. doi: 10.1002/pros.22925. https://doi.org/10.1002/pros.22925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Preston MA, Batista JL, Wilson KM, et al. Baseline prostate-specific antigen levels in midlife predict lethal prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:2705–11. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.66.7527. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2016.66.7527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gelfond J, Choate K, Ankerst DP, et al. Intermediate-term risk of prostate cancer is directly related to baseline prostate-specific antigen: Implications for reducing the burden of prostate-specific antigen screening. J Urol. 2015;194:46–51. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2015.02.043. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2015.02.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vickers AJ, Ulmert D, Sjoberg DD, et al. Strategy for detection of prostate cancer based on relation between prostate-specific antigen at age 40–55 and long-term risk of metastasis: Case-control study. BMJ. 2013;346:f2023. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f2023. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.f2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Carlsson S, Assel M, Sjoberg D, et al. Influence of blood prostate-specific antigen levels at age 60 on benefits and harms of prostate cancer screening: Population-based cohort study. BMJ. 2014;348:g2296. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g2296. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g2296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vickers AJ, Cronin AM, Bjork T, et al. Prostate-specific antigen concentration at age 60 and death or metastasis from prostate cancer: Case-control study. BMJ. 2010;341:c4521. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c4521. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.c4521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vickers AJ, Sjoberg DD, Ulmert D, et al. Empirical estimates of prostate cancer overdiagnosis by age and prostate-specific antigen. BMC Med. 2014;12:26. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-12-26. https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-12-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hamdy FC, Donovan JL, Lane JA, et al. 10-year outcomes after monitoring, surgery, or radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer. N Eng J Medicine. 2016;375:1415–24. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1606220. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1606220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sammon JD, Abdollah F, D’Amico A, et al. Predicting life expectancy in men diagnosed with prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2015;68:756–65. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.03.020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2015.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Haider MA, Yao X, Loblaw A, et al. Evidence-based guideline recommendations on multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of prostate cancer: A Cancer Care Ontario clinical practice guideline. Can Urol Assoc J. 2017;11:E1–7. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.3968. https://doi.org/10.5489/cuaj.3968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ahmed HU, El-Shater Bosaily A, Brown LC, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of multiparametric MRI and TRUS biopsy in prostate cancer (PROMIS): A paired validating confirmatory study. Lancet. 2017;389:815–22. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32401-1. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32401-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Carter HB, Pearson JD, Metter EJ, et al. Longitudinal evaluation of prostate-specific antigen levels in men with and without prostate disease. JAMA. 1992;267:2215–20. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1992.03480160073037. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Carter HB, Ferrucci L, Kettermann A, et al. Detection of life-threatening prostate cancer with prostate-specific antigen velocity during a window of curability. J Nat Canc Inst. 2006;98:1521–7. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj410. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djj410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.O’Brien MF, Cronin AM, Fearn PA, et al. Pretreatment prostate-specific antigen (PSA) velocity and doubling time are associated with outcome but neither improves prediction of outcome beyond pretreatment PSA alone in patients treated with radical prostatectomy. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3591–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.9794. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2008.19.9794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vickers AJ, Savage C, O’Brien MF, et al. Systematic review of pretreatment prostate-specific antigen velocity and doubling time as predictors for prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:398–403. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.1685. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2008.18.1685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Roobol MJ, Kranse R, de Koning HJ, et al. Prostate-specific antigen velocity at low prostate-specific antigen levels as screening tool for prostate cancer: Results of second screening round of ERSPC (ROTTERDAM) Urology. 2004;63:309–13. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2003.09.083. discussion 13–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2003.09.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Allan RW, Sanderson H, Epstein JI. Correlation of minute (0.5 MM or less) focus of prostate adenocarcinoma on needle biopsy with radical prostatectomy specimen: Role of prostate-specific antigen density. J Urol. 2003;170:370–2. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000074747.72993.cb. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ju.0000074747.72993.cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Radwan MH, Yan Y, Luly JR, et al. Prostate-specific antigen density predicts adverse pathology and increased risk of biochemical failure. Urology. 2007;69:1121–7. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.01.087. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2007.01.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lujan M, Paez A, Llanes L, et al. Prostate-specific antigen density. Is there a role for this parameter when screening for prostate cancer? Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2001;4:146–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.pcan.4500509. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.pcan.4500509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Djavan B, Remzi M, Zlotta AR, et al. Complexed prostate-specific antigen, complexed prostate-specific antigen density of total and transition zone, complexed/total prostate-specific antigen ratio, free-to-total prostate-specific antigen ratio, density of total and transition zone prostate-specific antigen: Results of the prospective multicentre European trial. Urology. 2002;60:4–9. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(02)01896-4. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0090-4295(02)01896-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Augustin H, Graefen M, Palisaar J, et al. Prognostic significance of visible lesions on transrectal ultrasound in impalpable prostate cancers: Implications for staging. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2860–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.11.130. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2003.11.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Resnick MI, Smith JA, Jr, Scardino PT, et al. Transrectal prostate ultrasonography: Variability of interpretation. J Urol. 1997;158:856–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-5347(01)64336-2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Etzioni R, Falcon S, Gann PH, et al. Prostate-specific antigen and free prostate-specific antigen in the early detection of prostate cancer: Do combination tests improve detection? Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13:1640–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bruzzese D, Mazzarella C, Ferro M, et al. Prostate health index vs percent free prostate-specific antigen for prostate cancer detection in men with “gray” prostate-specific antigen levels at first biopsy: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Transl Res. 2014;164:444–51. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2014.06.006. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trsl.2014.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liang Y, Ankerst DP, Ketchum NS, et al. Prospective evaluation of operating characteristics of prostate cancer detection biomarkers. J Urol. 2011;185:104–10. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.08.088. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2010.08.088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lee R, Localio AR, Armstrong K, et al. A meta-analysis of the performance characteristics of the free prostate-specific antigen test. Urology. 2006;67:762–8. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.10.052. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2005.10.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Partin AW, Brawer MK, Subong EN, et al. Prospective evaluation of percent free-PSA and complexed-PSA for early detection of prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 1998;1:197–203. doi: 10.1038/sj.pcan.4500232. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.pcan.4500232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Catalona WJ, Partin AW, Slawin KM, et al. Use of the percentage of free prostate-specific antigen to enhance differentiation of prostate cancer from benign prostatic disease: A prospective, multicentre clinical trial. JAMA. 1998;279:1542–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.19.1542. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.279.19.1542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ankerst DP, Gelfond J, Goros M, et al. Serial percent free prostate-specific antigen in combination with prostate-specific antigen for population-based early detection of prostate cancer. J Urol. 2016;196:355–60. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2016.03.011. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2016.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Vickers AJ, Cronin AM, Aus G, et al. A panel of kallikrein markers can reduce unnecessary biopsy for prostate cancer: Data from the European Randomized Study of Prostate Cancer Screening in Goteborg, Sweden. BMC Med. 2008;6:19. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-6-19. https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-6-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vickers A, Cronin A, Roobol M, et al. Reducing unnecessary biopsy during prostate cancer screening using a four-kallikrein panel: An independent replication. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2493–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.1968. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2009.24.1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bryant RJ, Sjoberg DD, Vickers AJ, et al. Predicting high-grade cancer at 10-core prostate biopsy using four kallikrein markers measured in blood in the ProtecT study. J Nat Canc Inst. 2015;107 doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Vickers AJ, Cronin AM, Roobol MJ, et al. A four-kallikrein panel predicts prostate cancer in men with recent screening: Data from the European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer, Rotterdam. Clinical Cancer Research. 2010;16:3232–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0122. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Vickers AJ, Cronin AM, Aus G, et al. Impact of recent screening on predicting the outcome of prostate cancer biopsy in men with elevated prostate-specific antigen: Data from the European Randomized Study of Prostate Cancer Screening in Gothenburg, Sweden. Cancer. 2010;116:2612–20. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25010. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.25010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Benchikh A, Savage C, Cronin A, et al. A panel of kallikrein markers can predict outcome of prostate biopsy following clinical workup: An independent validation study from the European Randomized Study of Prostate Cancer screening, France. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:635. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-635. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-10-635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gupta A, Roobol MJ, Savage CJ, et al. A four-kallikrein panel for the prediction of repeat prostate biopsy: Data from the European Randomized Study of Prostate Cancer screening in Rotterdam, Netherlands. Br J Cancer. 2010;103:708–14. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605815. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6605815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Parekh DJ, Punnen S, Sjoberg DD, et al. A multi-institutional prospective trial in the USA confirms that the 4Kscore accurately identifies men with high-grade prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2015;68:464–70. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.10.021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2014.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Konety B, Zappala SM, Parekh DJ, et al. The 4Kscore(R) test reduces prostate biopsy rates in community and academic urology practices. Rev Urol. 2015;17:231–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Vickers A, Vertosick EA, Sjoberg DD, et al. Properties of the 4-Kallikrein panel outside the diagnostic gray zone: Meta-analysis of patients with positive digital rectal examination or prostate-specific antigen 10 ng/ ml and above. J Urol. 2017;197:607–13. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2016.09.086. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2016.09.086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Jansen FH, van Schaik RH, Kurstjens J, et al. Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) isoform p2PSA in combination with total PSA and free PSA improves diagnostic accuracy in prostate cancer detection. Eur Urol. 2010;57:921–7. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2010.02.003. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Catalona WJ, Partin AW, Sanda MG, et al. A multicentre study of [-2]pro-prostate-specific antigen combined with prostate-specific antigen and free prostate-specific antigen for prostate cancer detection in the 2.0–10.0 ng/ml prostate-specific antigen range. J Urol. 2011;185:1650–5. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.12.032. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2010.12.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Loeb S, Sanda MG, Broyles DL, et al. The Prostate Health Index selectively identifies clinically significant prostate cancer. J Urol. 2015;193:1163–9. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2014.10.121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2014.10.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.de la Calle C, Patil D, Wei JT, et al. Multicentre evaluation of the Prostate Health Index to detect aggressive prostate cancer in biopsy-naive men. J Urol. 2015;194:65–72. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2015.01.091. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2015.01.091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Loeb S, Shin SS, Broyles DL, et al. Prostate Health Index improves multivariable risk prediction of aggressive prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2017;12:61–8. doi: 10.1111/bju.13676. https://doi.org/10.1111/bju.13676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Nordstrom T, Vickers A, Assel M, et al. Comparison between the four-kallikrein panel and Prostate Health Index for predicting prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2015;68:139–46. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.08.010. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2014.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Aubin SM, Reid J, Sarno MJ, et al. PCA3 molecular urine test for predicting repeat prostate biopsy outcome in populations at risk: Validation in the placebo arm of the dutasteride REDUCE trial. J Urol. 2010;184:1947–52. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.06.098. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2010.06.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Auprich M, Bjartell A, Chun FK, et al. Contemporary role of prostate cancer antigen 3 in the management of prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2011;60:1045–54. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.08.003. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bradley LA, Palomaki GE, Gutman S, et al. Comparative effectiveness review: Prostate cancer antigen 3 testing for the diagnosis and management of prostate cancer. J Urol. 2013;190:389–98. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.02.005. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2013.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Gittelman MC, Hertzman B, Bailen J, et al. PCA3 molecular urine test as a predictor of repeat prostate biopsy outcome in men with previous negative biopsies: A prospective, multicentre clinical study. J Urol. 2013;190:64–9. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.02.018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2013.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wei JT, Feng Z, Partin AW, et al. Can urinary PCA3 supplement PSA in the early detection of prostate cancer? J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:4066–72. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.52.8505. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2013.52.8505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Louie KS, Seigneurin A, Cathcart P, et al. Do prostate cancer risk models improve the predictive accuracy of PSA screening? A meta-analysis. Annals Oncol. 2015;26:848–64. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu525. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdu525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ankerst DP, Hoefler J, Bock S, et al. Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial risk calculator 2.0 for the prediction of low- vs. high-grade prostate cancer. Urology. 2014;83:1362–7. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2014.02.035. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2014.02.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Thompson IM, Ankerst DP, Chi C, et al. Assessing prostate cancer risk: Results from the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial. J Nat Canc Inst. 2006;98:529–34. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj131. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djj131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Roobol MJ, Steyerberg EW, Kranse R, et al. A risk-based strategy improves prostate-specific antigen-driven detection of prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2010;57:79–85. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2009.08.025. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2009.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Nam RK, Toi A, Klotz LH, et al. Assessing individual risk for prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3582–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.10.6450. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2007.10.6450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Poyet C, Nieboer D, Bhindi B, et al. Prostate cancer risk prediction using the novel versions of the European Randomized Study for Screening of Prostate Cancer (ERSPC) and Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial (PCPT) risk calculators: Independent validation and comparison in a contemporary European cohort. BJU Int. 2016;117:401–8. doi: 10.1111/bju.13314. https://doi.org/10.1111/bju.13314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Trottier G, Roobol MJ, Lawrentschuk N, et al. Comparison of risk calculators from the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial and the European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer in a contemporary Canadian cohort. BJU Int. 2011;108:E237–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10207.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Foley RW, Maweni RM, Gorman L, et al. European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC) risk calculators significantly outperform the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial (PCPT) 2.0 in the prediction of prostate cancer: A multi-institutional study. BJU Int. 2016;118:706–13. doi: 10.1111/bju.13437. https://doi.org/10.1111/bju.13437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Nam RK, Kattan MW, Chin JL, et al. Prospective multi-institutional study evaluating the performance of prostate cancer risk calculators. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2959–64. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.6371. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2010.32.6371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Oesterling JE, Jacobsen SJ, Chute CG, et al. Serum prostate-specific antigen in a community-based population of healthy men. Establishment of age-specific reference ranges. JAMA. 1993;270:860–4. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1993.03510070082041. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.DeAntoni EP, Crawford ED, Oesterling JE, et al. Age- and race-specific reference ranges for prostate-specific antigen from a large community-based study. Urology. 1996;48:234–9. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(96)00091-x. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0090-4295(96)00091-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Dalkin BL, Ahmann FR, Kopp JB. Prostate-specific antigen levels in men older than 50 years without clinical evidence of prostatic carcinoma. J Urol. 1993;150:1837–9. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)35910-4. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-5347(17)35910-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Morgan TO, Jacobsen SJ, McCarthy WF, et al. Age-specific reference ranges for serum prostate-specific antigen in black men. N Eng J Med. 1996;335:304–10. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199608013350502. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199608013350502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Eastham JA, Riedel E, Scardino PT, et al. Variation of serum prostate-specific antigen levels: An evaluation of year-to-year fluctuations. JAMA. 2003;289:2695–700. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.20.2695. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.289.20.2695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Lavallee LT, Binette A, Witiuk K, et al. Reducing the harm of prostate cancer screening: Repeated prostate-specific antigen testing. Mayo Clinic Proc. 2016;91:17–22. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.07.030. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Okotie OT, Roehl KA, Han M, et al. Characteristics of prostate cancer detected by digital rectal examination only. Urology. 2007;70:1117–20. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.07.019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2007.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Carvalhal GF, Smith DS, Mager DE, et al. Digital rectal examination for detecting prostate cancer at prostate-specific antigen levels of 4 ng/ml or less. J Urol. 1999;161:835–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-5347(01)61785-3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Gosselaar C, Roobol MJ, Roemeling S, et al. Screening for prostate cancer at low PSA range: The impact of digital rectal examination on tumour incidence and tumour characteristics. Prostate. 2007;67:154–61. doi: 10.1002/pros.20501. https://doi.org/10.1002/pros.20501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table 1.

Prostate cancer screening guidelines by other organizations

| Association (year) | Age (years) | Screening recommended (yes/no) | Additional details on recommendations | Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| United States Preventative Services Task Force (Recommendation Statement)a (2017)7 | 55–69 | Yesb |

|

NR |

|

| ||||

| ≥70 | No |

|

NR | |

|

| ||||

| European Association of Urology (2016)5 | >50 |

|

|

|

| >45 if at elevated riskc,d | Yesb | |||

|

| ||||

| <15 years life expectancy | No |

|

NA | |

|

| ||||

| National Comprehensive Cancer Network (2016)4 | 45–75 | Yesb |

|

|

| >75 | Yesj | |||

|

| ||||

| Canadian Task Force on Preventative Health (2014)8 | <55 | No | Based on:

|

NR |

|

| ||||

| 55–69 | No | This recommendation places:

|

NR | |

| ≥70 | No | This recommendation reflects:

|

NR | |

|

| ||||

| American Urological Association (2013)3 | <40 | No |

|

NR |

|

|

||||

| 40–54 | Yesb |

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| 55–69 | Yesb |

|

||

|

|

||||

| ≥70 | No |

|

NR | |

|

| ||||

| American College of Physicians (2013)6 | <50 | No |

|

|

|

| ||||

| 50–69 | Yesb | ACP recommends that clinicians:

|

||

|

| ||||

| ≥70 | No |

|

||

Draft recommendation statement was available for public comment until May 8, 2017; final statement in development;

on case-by-case basis after discussion of risks and benefits;

African-American men and/or family history of prostate cancer;

men with prior PSA assessment and a PSA level of >1 ng/mL at 40 years of age or >2 ng/mL at 60 years of age;

including prior PSA and/ or isoforms, exams, and biopsies;

African-American men have a higher incidence of prostate cancer, increased prostate cancer mortality, and earlier age of diagnosis compared to Caucasian-American men; however, the effects of earlier or more intensive screening on cancer outcomes and on screening-related harms in African-American men remain unclear. Although they may require a higher level of vigilance and different considerations when analyzing the results of screening tests, current data do not support separate screening recommendations for African-American men;

the best evidence supports the use of serum PSA for the early detection of prostate cancer. DRE should not be used as a stand-alone test, but should be performed in those with an elevated serum PSA. DRE may be considered as a baseline test in all patients as it may identify high-grade cancers associated with “normal” serum PSA values. Consider referral for biopsy if DRE is very suspicious. Medications such as 5α-reductase inhibitors (finasteride and dutasteride) are known to decrease PSA by approximately 50%, and PSA values in these men should be corrected accordingly;

men age ≥60 years with serum PSA <1.0 ng/mL have a very low risk of metastases or death due to prostate cancer and may not benefit from further testing. A PSA cut point of 3.0 ng/mL at age 75 years also low risk of poor outcome;