Abstract

OBJECTIVE

Evaluate the association between surgical (SM) versus natural menopause (NM) in relation to later left ventricular (LV) structure and function, while taking into account the LV parameters and other cardiovascular disease risk factor (CVDRF) levels that predates the menopausal transition.

METHODS

We studied 825 premenopausal women from the CARDIA study in 1990–1991 (baseline, mean age: 32 years) who later reached menopause by 2010–2011 and had echocardiograms at these two time points.

RESULTS

During 20 years of follow up, 508 women reached NM while 317 underwent SM (34% had bilateral oophorectomy (BSO)). At baseline, women who later underwent SM were more likely to be black, younger, have greater parity and higher mean values of systolic blood pressure, body mass index as well as lower mean HDL cholesterol and physical activity than women who reached NM. No significant differences in LV structure/function were found between groups. In 2010–2011, SM women had significantly higher LV mass, LV mass/volume ratio, E/e′ ratio, and impaired longitudinal and circumferential strain than NM women. SM women with BSO had adverse LV measures than women with hysterectomy with ovarian conservation. Controlling for baseline echocardiographic parameters and CVDRF in linear regression models eliminated these differences between groups. Further adjustment for age at menopause/surgery and hormone therapy use did not change these results.

CONCLUSION

In this study, the adverse LV structure and function observed among women with SM compared to NM were explained by their unfavorable presurgical CVDRF profiles, suggesting that premenopausal CVDRF rather than gynecologic surgery predispose SM women to elevated future cardiovascular disease risk.

Keywords: Left ventricles, echocardiography, epidemiology, menopause, women

INTRODUCTION

The association of surgical menopause (SM) with cardiovascular disease (CVD) outcomes is unclear. SM, defined as menstrual cessation due to hysterectomy with ovarian conservation (HOC) or bilateral oophorectomy (HBSO), reduces a woman’s exposure to endogenous estrogen when prior to age of natural menopause (NM)1, 2. Some studies have proposed that this estrogen deficiency may explain the elevated CVD risk among women with SM especially women with HBSO3, 4. However, evidence suggests that women who undergo SM tend to have adverse cardiovascular disease risk factors (CVDRF) long before the onset of menopause, which may account for their elevated risk of CVD events in later life5, 6.

Findings from the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study5 and the Study of Women’s Health across the Nation (SWAN)6 showed that accounting for pre-surgical CVDRF levels attenuated the observed significant differences in postmenopausal CVDRF levels between women with NM and SM.

Left ventricular (LV) structure and function is a strong predictor of several future CVD events7–9, but evidence for the long-term association of SM with cardiac structure and function is lacking. Reports based on rodent models suggest acute adverse effects of SM on cardiac structure and function, namely increased in LV filling pressures and myocardial remodeling leading to diastolic dysfunction10–12. Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate the association of SM compared to NM with echocardiographic parameters of LV structure and function, accounting for antecedent CVDRF levels.

METHODS

Study population

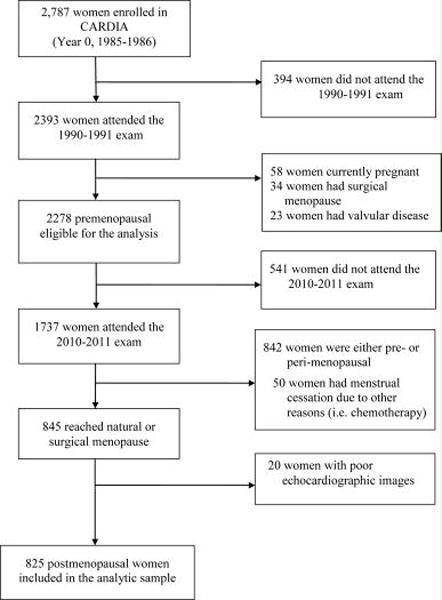

The CARDIA Study is a multi-center longitudinal study of 5,115 (2,787 women) adults aged 18–30 years who were recruited in 1985–1986 from four U.S. urban centers (Birmingham, Alabama; Chicago, Illinois; Minneapolis, Minnesota; and Oakland, California) to examine cardiovascular risk factor trends in young adults. The sample was recruited to be balanced on sex, race (white or black), age (18–24 or 25–30 years) and education (≤12, >12 years). To date, seven follow-up examinations have occurred after baseline with 72% of the surviving cohort attending the year 25 exam. Details of the study design and methods have been described elsewhere13. Of the 2278 eligible non-pregnant women without surgical menopause or valvular disease at the year 5 exam (baseline for this analysis), 1737 of them also attended the year 25 exams (follow-up exam for this analysis). Women who did not attend year 25 visit were more likely to be of black race, younger, and current smokers and to have fewer years of education at baseline. These two time points were chosen since echocardiography was performed on the entire cohort at years 5 (1990–1991) and 25 (2010–2011) exams. Among the 1737 women, we excluded those who were pre- or perimenopausal at year 25 exams (n=842) or who reported menstrual cessation due to other reasons (n=50) as well as women who had poor echocardiographic images. This resulted in an analytic sample of 825 women (figure 1). All participants provided written informed consent with data collection and cohort follow-up protocols approved by the Institutional Review Boards of each field center as well as the Coordinating Center.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of study sample selection; CARDIA: Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults study

Measures

At every CARDIA exam, standardized protocols were used to collect information on demographics, anthropometrics, lifestyle and behavioral factors, medical history, biomarkers, and medication use from participants. Women were additionally asked if they were currently pregnant or breastfeeding, age at menarche, regularity of their menstrual period, gynecological surgeries and use of oral contraceptives or hormone therapy for menopausal symptoms. Women reporting no menstrual cycles within the previous 12 months prior to their follow-up exam were considered postmenopausal in accordance with the World Health Organization criteria14. Among postmenopausal women, those who reported cessation of menstrual bleeding not preceded by hysterectomy, radiation or chemotherapy were classified as having NM while those who reported menstrual cessation due to hysterectomy with or without self-reported bilateral oophorectomy were classified as having SM. Age at final menstrual period (FMP) was defined as self-reported age at natural cessation of menstrual flow or age at surgery to remove the uterus and/or ovaries. When the FMP was unknown, it was set to the age at clinic visit at which participant first reported having undergone NM or SM.

At baseline, blood pressure was measured using a random-zero sphygmomanometer with participants seated and after 5 minutes of rest. At the 20-year follow-up exam, blood pressure was measured using an Omron aneroid device (Omron Healthcare Inc., Lake Forest, Illinois) and calibrated to the random zero measures15. The average of the second and third consecutive measurements was used for analysis. Cigarette smoking was assessed by means of an interviewer-administered tobacco questionnaire16. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated by dividing weight in kilograms by height in meters squared. Waist circumference was measured to the nearest 0.5 cm at the level of the umbilicus. Physical activity level was assessed using a modified version of the Minnesota Leisure Time Physical Activity Questionnaire, with total scores representing total moderate-to-vigorous activity expressed in exercise units. Family history of coronary heart disease was defined as a positive parental history of heart attack. Alcohol Intake was defined as consumption of any alcoholic beverages in the past year. Lipid levels were assessed from fasting blood. Plasma total cholesterol, triglycerides and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol were measured enzymatically by Northwest Lipid Research Laboratories (Seattle, Washington). Diabetes was defined by one or more of the following: elevated fasting serum glucose levels ≥ 126 mg/dL, oral glucose tolerance test ≥ 200 mg/dL, hemoglobin A1C ≥ 6.5%; or reported use of diabetes medications (e.g. insulin or oral hypoglycemics).

Echocardiography

Echocardiography was performed using an ACUSON cardiac ultrasound system (Siemens) at baseline and Artida cardiac ultrasound scanner (Toshiba Medical Systems, Otawara, Japan) at the follow-up exam by trained sonographers. A reliability study conducted in a subset of the cohort showed good agreement between repeated echocardiographic measures17. Left ventricular mass (LVM) was calculated using the Devereux formula18 and indexed to body surface area. LV mass-to-volume ratio (LVMVR) was calculated by dividing LVM by LV end-diastolic volume. Cardiac output was determined as the product of stroke volume and heart rate. LV ejection fraction (LVEF) was calculated as the ratio of stroke volume to end-diastolic volume. E/A ratio was calculated as the ratio of mitral peak early (E) to late (A) diastolic filling velocity. Peak early diastolic mitral annular velocity (e´) was calculated from the average of the septal and lateral mitral annular velocities.

At the follow-up exam, two-dimensional speckle-tracking echocardiography (STE) for myocardial strain was also performed and analyzed using two-dimensional wall motion tracking software (UltraExtend Version 2.7, Toshiba Medical Systems, Otawara, Japan). Strain was calculated as the change in segment length relative to its end-diastolic length from peak systolic values19. Global strain values were calculated as the average of segmental peak systolic strain. More negative values of global longitudinal and circumferential peak strain indicate greater shortening or better function. Quality control and reproducibility profile of the CARDIA echocardiography and STE exams have been previously described20

Statistical Analyses

Analytic sample characteristics at baseline, stratified by menopausal status at the follow-up exam, were compared using χ2 test for categorical variables and t test for continuous variables. For analyses in which SM was further stratified by ovarian status, analysis of variance was used for quantitative measures. Differences in echocardiography parameters at the follow-up exam were determined between SM and NM using unadjusted and adjusted general linear regression models. Models were adjusted for covariates measured at baseline (age, race, education, center, BMI, waist girth, physical activity, parity, smoking status, oral contraceptives, alcohol intake, family history of CHD, systolic blood pressure, diabetes, age at menarche, HDL and total cholesterol) as well as each respective baseline echocardiographic parameter. Additional models adjusting for age at FMP and the use of hormone therapy or anti-hypertensive medication during 20 years of follow up were examined. Tests for interaction between type of menopause and race for each echocardiography parameter were undertaken. P values were adjusted for multiple comparisons using Tukey-Kramer method. All statistical tests were two-sided and performed at the 0.05 level of significance using SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Description of study participants at baseline (1990–1991)

Descriptive statistics for the cohort are presented in Table 1. Approximately 38% of women reported having undergone surgical menopause by year 25, with a third of them reporting HBSO. At baseline, when all participants were premenopausal, those who later had SM during follow-up were younger with a greater proportion of them being black and having high school education or less compared to women who later reached NM. Additionally, at year 5, women who later had SM reached menarche at an earlier age, had higher systolic blood pressure, body mass index, waist circumference and lower levels of HDL cholesterol and physical activity. Among women who later had SM, those who had HOC were younger with a greater proportion of them being black compared to women with HBSO (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the 825 women in the analytic sample according to menopausal status at follow-up exam, The CARDIA study, 1990–1991a

| Natural | Surgical | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| NM (n=508) |

HOC (n=210) |

HBSO (n=107) |

HOC + HBSO (N=317) |

P valueb | P valuec | P valued | |

| Age (years) | 32.6 (2.5) | 29.9 (3.3) | 31.1 (3.3) | 30.3 (3.3) | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.002 |

| Race (%) | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.010 | ||||

| Black | 36.6 | 74.3 | 59.8 | 69.4 | |||

| White | 63.4 | 25.7 | 40.2 | 30.6 | |||

| High school graduate or less (%) | 26.2 | 37.1 | 34.6 | 36.3 | 0.008 | 0.002 | 0.71 |

| Current smoking status (%) | 24.6 | 27.1 | 25.2 | 26.5 | 0.78 | 0.54 | 0.79 |

| Current birth control pill use (%) | 20.7 | 21.9 | 17.8 | 20.5 | 0.69 | 0.96 | 0.46 |

| Current alcohol use (%) | 83.1 | 77.6 | 68.2 | 74.4 | 0.002 | 0.003 | 0.07 |

| Parity (%) | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.12 | ||||

| None | 45.7 | 33.9 | 29.0 | 32.2 | |||

| One | 20.7 | 21.9 | 32.7 | 25.6 | |||

| Two | 20.3 | 25.2 | 26.2 | 25.6 | |||

| Three or more | 13.4 | 19.0 | 12.1 | 16.7 | |||

| Family history of CHD (%) | 20.5 | 21.0 | 23.4 | 21.8 | 0.80 | 0.66 | 0.67 |

| Diabetes (%) | 0.2 | 1.0 | 1.9 | 1.3 | 0.10 | 0.06 | 0.61 |

| Systolic Blood pressure (mmHg) | 103.6 (11.3) | 106.8 (10.7) | 105.3 (10.2) | 106.3 (10.6) | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.24 |

| Antihypertensive medication (%) | 2.2 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 0.97 | 0.79 | 0.98 |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | 25.8 (6.8) | 27.7 (6.6) | 27.1 (5.9) | 27.5 (6.4) | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.42 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 77.6 (13.2) | 81.2 (12.8) | 80.1 (12.3) | 80.8 (12.6) | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.48 |

| Physical activity (exercise units) | 324.6 (241) | 267.6 (222) | 261.7 (238) | 265.6 (227) | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.83 |

| HDL cholesterol (mmol/l) | 1.5 (0.3) | 1.4 (0.3) | 1.4 (0.4) | 1.4 (0.3) | 0.042 | 0.012 | 0.94 |

| LDL cholesterol (mmol/l) | 2.7 (0.8) | 2.7 (0.7) | 2.8 (0.6) | 2.7 (0.7) | 0.79 | 0.90 | 0.46 |

| Total Cholesterol (mmol/l) | 4.6 (0.8) | 4.5 (0.7) | 4.5 (0.6) | 4.5 (0.7) | 0.56 | 0.35 | 0.58 |

| Lipid-lowering medication use (%) | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.73 | 0.43 | – |

| Age at menarche (years) | 12.6 (1.7) | 12.2 (1.8) | 12.3 (1.3) | 12.2 (1.6) | 0.006 | 0.002 | 0.68 |

CHD: Coronary heart disease. HDL: High-density lipoprotein. HOC: Hysterectomy with ovarian conservation; HBSO: Hysterectomy with Bilateral Oophorectomy.

Values are mean (standard deviation) for continuous variables and percentages for categorical variables.

P value for group differences in type of menopause (NM vs. HOC vs. HBSO)

P value comparing women with NM to surgical menopause (HOC + HBSO)

P value comparing women with HOC to women with HBSO

Description of study participants at follow-up exam (2010–2011)

The differences in CVDRF levels observed between women with NM and SM at year 5 women persisted at year 25 (Table 2) with SM women, on average, reaching FMP at earlier age compared to NM women (41.8 vs. 48.6 years). Compared to women with NM, a greater proportion of women with SM were on antihypertensive medications (44.5 vs. 26.6). Although there was no significant difference in lipid-lowering medication between women with NM and SM, the latter were observed to have lower total cholesterol levels (5.0 vs. 5.2 mmol/l). With regard to women with SM, those with HOC reported an earlier age at FMP than women with HBSO. The use of hormone therapy was higher among women with HBSO (26%) compared to women with HOC (11%) or NM (9%) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics at the follow-up exam for the 825 women who reached natural or surgical menopause, The CARDIA study, 2010–2011a

| Natural | Surgical | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| NM (n=508) |

HOC (n=210) |

HBSO (n=107) |

HOC + HBSO (N=317) |

P valueb | P valuec | P valued | |

| Age (years) | 52.7 (2.5) | 49.9 (3.3) | 51.2 (3.3) | 50.3 (3.3) | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| Race (%) | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.010 | ||||

| Black | 36.6 | 74.3 | 59.8 | 69.4 | |||

| White | 63.4 | 25.7 | 40.2 | 30.6 | |||

| High school graduate or less (%) | 18.7 | 27.6 | 25.2 | 26.8 | 0.021 | 0.006 | 0.69 |

| Current smoking status (%) | 15.2 | 15.2 | 15.9 | 15.5 | 0.98 | 0.91 | 0.87 |

| Current hormone therapy use (%) | 9.4 | 10.5 | 25.2 | 15.5 | 0.001 | 0.009 | 0.006 |

| Current alcohol use (%) | 80.7 | 70.0 | 66.4 | 68.8 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.52 |

| Parity (%) | 0.017 | 0.042 | 0.07 | ||||

| None | 29.5 | 22.4 | 17.8 | 20.8 | |||

| One | 20.1 | 21.9 | 29.9 | 24.6 | |||

| Two | 28.9 | 29.5 | 36.4 | 31.9 | |||

| Three or more | 21.5 | 26.2 | 15.9 | 22.7 | |||

| Family history of CHD (%) | 33.9 | 32.4 | 40.2 | 35.0 | 0.36 | 0.73 | 0.17 |

| Diabetes (%) | 11.4 | 19.0 | 24.3 | 20.8 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.26 |

| Systolic Blood pressure (mmHg) | 116.8 (17.0) | 121.4 (16.8) | 117.9 (16.5) | 120.2 (16.8) | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.80 |

| Antihypertensive medication (%) | 26.6 | 42.4 | 48.6 | 44.5 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.34 |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | 29.8 (8.0) | 32.9 (7.6) | 33.1 (7.5) | 33.0 (7.5) | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.88 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 90.0 (16.6) | 95.4 (14.9) | 95.7 (16.3) | 95.5 (15.3) | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.87 |

| Physical activity (exercise units) | 309.5 (255) | 237 (221) | 197.7 (183) | 223.5 (210) | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.12 |

| HDL cholesterol (mmol/l) | 1.7 (0.5) | 1.6 (0.5) | 1.5 (0.5) | 1.6 (0.5) | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.27 |

| LDL cholesterol (mmol/l) | 3.0 (0.9) | 2.9 (0.8) | 2.8 (0.9) | 2.9 (0.9) | 0.23 | 0.11 | 0.55 |

| Total Cholesterol (mmol/l) | 5.2 (1.0) | 5.1 (1.0) | 5.0 (0.9) | 5.0 (1.0) | 0.012 | 0.007 | 0.51 |

| Lipid-lowering medication use (%) | 16.3 | 18.6 | 20.6 | 19.2 | 0.51 | 0.29 | 0.65 |

| Age at FMP/surgery (years) | 48.6 | 40.6 | 44.3 | 41.8 (5.5) | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

CHD: Coronary heart disease. HDL: High-density lipoprotein. FMP: Final menstrual period; HOC: Hysterectomy with ovarian conservation; HBSO: Hysterectomy with Bilateral Oophorectomy.

Values are mean (standard deviation) for continuous variables and percentages for categorical variables.

P value for group differences in type of menopause (NM vs. HOC vs. HBSO)

P value comparing women with NM to surgical menopause (HOC + HBSO)

P value comparing women with HOC to women with HBSO

Echocardiographic parameters among study participants

Differences in parameters of LV structure and function namely, LVM, LVMVR, cardiac output, LVEF and E/A ratio, at year 5 between women who later reached NM or SM were not statistically significant (data not shown). However, at the follow-up exam, women with SM had higher LV mass (158 vs. 147 g), LVMVR (1.7 vs. 1.5), cardiac output (4.2 vs. 4.0), impaired longitudinal and circumferential strain indicative of lower LV systolic function, and higher LV filling pressures assessed by the ratio of early mitral inflow velocity to early mitral annular diastolic velocity (E/e′) (Supplemental Figure S1. Supplemental Digital Content 1). Among SM women, these adverse differences appeared to be greater in women with HBSO than women with HOC (Supplemental Figure S2. Supplemental Digital Content 2).Adjustment for baseline echocardiographic measures and CVDRF levels eliminated the adverse associations of SM with future LV structure and function (Table 3). Additional adjustment for age at FMP as well as hormone therapy and anti-hypertensive medication use during the 20-year follow-up did not significantly influence these findings. These results remained consistent when women with HOC or HBSO were compared to women with NM (Table 4). Additionally, among women with SM, there were no significant differences by ovarian status for all measures of LV structure and function after accounting for antecedent CVDRF (Table 4). Finally, we failed to identify any significant interactions between race (black/white) and type of menopause for all the parameters of LV structure and function (Supplemental Table S1. Supplemental Digital Content 3).

Table 3.

Adjusted mean (standard error) echocardiographic measures of left ventricular structure and function among women with natural or surgical menopause, the CARDIA study, 2010–2011

| Model 1

|

Model 2

|

Model 3

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NM | SM | P | NM | SM | P | NM | SM | P | |

| Left ventricular structure | |||||||||

| LV mass (g) | 146.6 (1.9) | 157.4 (2.4) | 0.001 | 153.0 (2.2) | 151.5 (2.7) | 0.65 | 152.7 (2.3) | 152.3 (3.0) | 0.91 |

| LV mass index (g/m2) | 80.0 (0.9) | 81.8 (1.2) | 0.06 | 82.2 (1.1) | 80.4 (1.4) | 0.28 | 82.3 (1.2) | 80.1 (1.5) | 0.25 |

| LV mass/volume ratio | 1.56 (0.04) | 1.63 (0.05) | 0.28 | 1.68 (0.05) | 1.67 (0.06) | 0.96 | 1.69 (0.05) | 1.65 (0.06) | 0.63 |

| Left ventricular systolic function | |||||||||

| Cardiac Output (L/min) | 3.91 (0.07) | 4.16 (0.10) | 0.044 | 3.94 (0.09) | 4.00 (0.12) | 0.67 | 4.09 (0.10) | 3.90 (0.13) | 0.25 |

| Global longitudinal straina | −15.4 (0.1) | −14.7 (0.2) | 0.001 | −15.2 (0.1) | −15.0 (0.2) | 0.61 | −15.2 (0.2) | −15.0 (0.2) | 0.58 |

| Circumferential peak Straina | −15.7 (0.1) | −15.2 (0.2) | 0.036 | −15.5 (0.2) | −15.3 (0.2) | 0.54 | −15.5 (0.2) | −15.4 (0.2) | 0.75 |

| LV ejection fraction (%) | 62.0 (0.5) | 62.2 (0.6) | 0.77 | 62.5 (0.6) | 61.8 (0.8) | 0.43 | 62.3 (0.6) | 62.2 (0.8) | 0.87 |

| Left ventricular Diastolic function | |||||||||

| E/A ratio | 1.24 (0.02) | 1.22 (0.02) | 0.41 | 1.22 (0.02) | 1.21 (0.02) | 0.77 | 1.22 (0.02) | 1.20 (0.03) | 0.77 |

| E/e′a | 8.12 (0.1) | 8.58 (0.1) | 0.025 | 8.34 (0.1) | 8.46 (0.2) | 0.56 | 8.34 (0.1) | 8.50 (0.2) | 0.46 |

NM: Natural menopause, SM: Surgical menopause. LV: Left ventricular. E/A: mitral ratio of peak early (E) to late (A) diastolic filling velocity

Echo parameters measured only at year 25

Model 1 adjusted for each year 5 respective echo measures

Model 2, Model 1 and additional adjustment for year 5 covariates [age (continuous), race (black, white), education (less than high school, high school or more), center (Birmingham, Chicago, Minneapolis, Oakland), BMI (continuous), waist girth (continuous), physical activity (continuous), parity (none, one, two, three or more), current smoking status (yes, no), current oral contraceptives (yes, no), current alcohol use (yes, no), family history of CHD (yes, no), systolic blood pressure (continuous), diabetes (yes, no), age at menarche (continuous), HDL (continuous) and total cholesterol (continuous)].

Model 3, model 2 and additional adjustment for age at final menstrual period (continuous), current hormone therapy use (yes, no) and antihypertensive medication use (yes, no) and diabetes during follow up (yes, no).

Table 4.

Adjusted mean echocardiographic measures of left ventricular structure and function among women who reached natural menopause or underwent hysterectomy with or without bilateral oophorectomy, the CARDIA study, 2010–2011

| Unadjusted

|

Adjusted

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | NM | HOC | HBSO | Pb | Pc | Pd | NM | HOC | HBSO | Pb | Pc | Pd |

| LV Structure | ||||||||||||

| LV Mass, g | 146.9 | 157.4 | 160.1 | 0.001 | 0.006 | 0.65 | 153.2 | 150.3 | 155.4 | 0.54 | 0.91 | 0.62 |

| LV Mass Index, g/m2 | 79.2 | 81.6 | 83.0 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.61 | 82.1 | 80.0 | 81.9 | 0.31 | 0.93 | 0.32 |

| LV Mass/Volume Ratio | 1.54 | 1.65 | 1.67 | 0.28 | 0.018 | 0.82 | 1.67 | 1.64 | 1.76 | 0.60 | 0.79 | 0.54 |

| LV Systolic Function | ||||||||||||

| Cardiac Output, L/min | 3.99 | 4.25 | 4.17 | 0.044 | 0.13 | 0.55 | 3.95 | 4.05 | 3.99 | 0.74 | 0.99 | 0.62 |

| Longitudinal Straina | −15.4 | −14.9 | −14.3 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.10 | −15.1 | −15.3 | −14.5 | 0.72 | 0.14 | 0.06 |

| Circumferential Straina | −15.7 | −15.3 | −15.1 | 0.036 | 0.041 | 0.47 | −15.5 | −15.4 | −15.0 | 0.57 | 0.53 | 0.62 |

| LV Ejection Fraction,% | 64.5 | 63.5 | 63.8 | 0.77 | 0.87 | 0.70 | 62.5 | 61.6 | 62.6 | 0.73 | 0.99 | 0.73 |

| LV Diastolic Function | ||||||||||||

| E/A Ratio | 1.24 | 1.23 | 1.20 | 0.41 | 0.26 | 0.54 | 1.22 | 1.20 | 1.21 | 0.78 | 0.99 | 0.76 |

| E/E′ Ratioa | 8.18 | 8.47 | 8.79 | 0.025 | 0.023 | 0.30 | 8.34 | 8.35 | 8.72 | 0.64 | 0.42 | 0.44 |

NM: Natural menopause, HOC: hysterectomy with ovarian conservation, HBSO: Hysterectomy with bilateral oophorectomy, LV: Left ventricular. E/A: mitral ratio of peak early (E) to late (A) diastolic filling velocity

Model adjusted for each respective year 5 echocardiographic parameter and covariates [age (continuous), race (black, white), education (less than high school, high school or more), center (Birmingham, Chicago, Minneapolis, Oakland), BMI (continuous), waist girth (continuous), physical activity (continuous), parity (none, one, two, three or more), current smoking status (yes, no), current oral contraceptives (yes, no), current alcohol use (yes, no), family history of CHD (yes, no), systolic blood pressure (continuous), diabetes (yes, no), age at menarche (continuous), HDL (continuous) and total cholesterol (continuous)].

Echo parameters measured only at year 25

P value comparing women with natural menopause to surgical menopause (HOC + HBSO)

P value comparing women with HBSO to women with natural menopause

P value comparing women with HOC to women with HBSO

P values were adjusted for multiple comparisons using Tukey-Kramer method

DISCUSSION

In this population-based cohort study of young adult women followed for 20 years, we observed that those who underwent surgical menopause during follow up had more adverse CVDRF levels at baseline, prior to surgery, compared to women who reached natural menopause at follow-up. However, controlling for baseline CVDRF and echocardiographic parameters assessed before surgery attenuated the adverse associations of surgical menopause with future LV structure and function. These data suggest that premenopausal CVDRF levels rather than gynecologic surgery predispose women with SM to elevated future CVD risk compared to women with NM.

Menopause is characterized by physiological changes that influence several systems and organs including the cardiovascular system. Previous small studies observed that postmenopausal women had more LV systolic and diastolic dysfunction than premenopausal women21–23. Similarly, other case-control studies observed higher relative wall thickness and concentric LV geometric remodeling independent of high blood pressure24 as well as lower peak early diastolic velocity E wave and mitral E/A ratio indicative of impaired LV diastolic filling25 in postmenopausal women compared to premenopausal women. Among postmenopausal women, those who reached menopause before age 40 years have also been reported to have significant impairment in LV systolic function compared to women with onset of menopause at ages ≥50 years23. A limitation of all these studies is the inability to assess differences in cardiac structure and function among postmenopausal women by type of menopause as well as antecedent risk factors levels.

The long-term association of SM compared to NM with cardiac function has not been well characterized. Results from experimental studies10–12 in adult female rats show that the onset of SM leads to perivascular fibrosis with associated increases in LV filling pressures, myocardial remodeling characterized by LV hypertrophy, and substantial increase in LV dilatation. In evaluating LV performance using systolic time intervals assessed by electrocardiogram and carotid artery pulse tracings in 50 postmenopausal women (25 with NM and 25 with SM), Kaur et al26 observed, in unadjusted models, impaired systolic function among women with SM compared to women with NM. While there was no difference in LV ejection time between groups, SM women had longer isovolumetric contraction time and showed signs of diminished cardiac performance indicated by elevated ratio of pre-ejection period to LV ejection time; a parameter that is known to be inversely correlated with the ejection fraction measured by echocardiography26. Consistent with these findings, we observed in the present study lower LV systolic function by means of impaired longitudinal and circumferential peak strain assessed by 2D speckle tracking echocardiography, and higher LV filling pressures in women with SM compared to NM women in unadjusted models. However, these differences in LV function together with variations in parameters of LV structure between women with NM and SM were observed to be explained by differences in CVDRF occurring long before the onset of menopause.

Some prior studies report that the elevated risk of CVD events in women with SM may be due to the reduction in exposure to ovarian estrogen. Estrogen deficiency after menopause has been reported to be associated with adverse levels of CVDRF in women27–29. Evidence from experimental studies suggests that reduced estrogen levels may directly or indirectly contribute to diastolic dysfunction and hypertensive heart diseases in postmenopausal women30, 31. Conversely, other studies report no difference in the circulating levels of estradiol and estrone2, 32 among women with SM compared to women with NM. Furthermore, results from trials33–35 assessing the influence of hormone therapy on atherosclerosis progression in recently menopausal women are equivocal which casts doubts on a cardio-protective role for estrogen in CVD development among postmenopausal women. It is possible that other processes besides ovarian estrogen deficiency contribute to both menopause and CVD incidence, and thus the observed association between SM and CVD may not be causal but may reflect residual confounding of unmeasured variables.

Different lines of evidence indicate that CVDRF, namely obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia and smoking in young adulthood, influence both the age at NM or indications for SM36–40. A growing body of research from CARDIA and the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation suggest that women who undergo SM tend to have adverse CVDRF levels long before the onset of menopause, and that accounting for these premenopausal CVDRF levels attenuate the significant differences in postmenopausal CVDRF levels between women with NM and SM5, 6. Accordingly, when we controlled for premenopausal CVDRF in the present study, postmenopausal differences in cardiac structure and function between women with NM and SM were eliminated. This observation suggests that perhaps the underlying pathology for the higher incidence of CVD events reported in some prior studies among women with SM may have existed long before the onset of menopause. In the present study as well as others, women with SM had adverse CVDRF profiles long before undergoing surgery compared to women who later on reach NM.

The strengths of this study include the use of a large population-based biracial sample, extensive assessment of CVDRF, and repeated echocardiography measurements coupled with good retention during 20 years of follow-up. Potential limitations of this study warrant consideration. First, menopausal status, type and age at onset of menopause were all self-reported, which may be subject to recall error. However, self-reported SM data have been found to have good validity in other studies (sensitivity, 64%; positive predictive value, 100%), with a woman’s accuracy in recalling age at SM surpassing recall of age at NM41. Second, STE for myocardial strain was only performed at year 25. Third, echocardiograms were done 20 years apart using different equipment, sonographers and reading centers, which may affect comparability of the indices of LV structure and function. However, a reliability study conducted in this cohort showed good agreement between repeated echocardiographic measures17. Fourth, while LV structure and function are associated with increased risk of some types of cardiovascular events, they do not entirely represent clinical endpoints. Fifth, due to the lack of information on serially measured endogenous hormones such as estrogen and androgens during the menopausal transition, their influence on the association of type of menopause with LV structure and function could not be evaluated. Finally, results of the present study may or may not be generalizable beyond black and white women.

CONCLUSION

We observed no significant difference in LV structure and function between women with SM or NM after accounting for antecedent CVDRF levels. Our results have important clinical and public health implications as they provides evidence that premenopausal CVDRF predispose SM women to adverse LV structure and function during the postmenopausal period rather than gynecologic surgery resulting in SM. Therefore, implementation of risk factor management should begin early in a woman’s life to reduce the risk of CVD in the postmenopausal period regardless of the type of menopause.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Digital Content 1. Image that illustrate differences in LV structure and function parameters among women with natural and surgical menopause. tif

Supplemental Digital Content 2. Image that illustrate differences in LV structure and function parameters among women with natural menopause, hysterectomy with ovarian conservation and hysterectomy with bilateral oophorectomy. tif

Supplemental Digital Content 3. Table that illustrates the no significant race and type of menopause interaction. doc

Acknowledgments

FUNDING SOURCES

The Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults Study (CARDIA) is supported by contracts HHSN268201300025C, HHSN268201300026C, HHSN268201300027C, HHSN268201300028C, HHSN268201300029C, and HHSN268200900041C from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Aging (NIA), an intra-agency agreement between NIA and NHLBI (AG0005). Dr. Appiah was supported by NHLBI training grant T32HL007779.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES: None

References

- 1.Laughlin GA, Barrett-Connor E, Kritz-Silverstein D, von Muhlen D. Hysterectomy, oophorectomy, and endogenous sex hormone levels in older women: the Rancho Bernardo Study. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. [The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism] 2000;85(2):645–51. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.2.6405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kotsopoulos J, Shafrir AL, Rice M, et al. The relationship between bilateral oophorectomy and plasma hormone levels in postmenopausal women. Horm Cancer. 2015;6(1):54–63. doi: 10.1007/s12672-014-0209-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lobo RA. Surgical menopause and cardiovascular risks. Menopause. 2007;14(3 Pt 2):562–6. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e318038d333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Colditz GA, Willett WC, Stampfer MJ, Rosner B, Speizer FE, Hennekens CH. Menopause and the risk of coronary heart disease in women. The New England journal of medicine. [The New England journal of medicine] 1987;316(18):1105–10. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198704303161801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Appiah D, Schreiner PJ, Bower JK, Sternfeld B, Lewis CE, Wellons MF. Is Surgical Menopause Associated With Future Levels of Cardiovascular Risk Factor Independent of Antecedent Levels? The CARDIA Study. American journal of epidemiology. 2015;182(12):991–9. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwv162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matthews KA, Gibson CJ, El Khoudary SR, Thurston RC. Changes in Cardiovascular Risk Factors by Hysterectomy Status With and Without Oophorectomy: Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2013;62(3):191–200. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.04.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kane GC, Karon BL, Mahoney DW, et al. Progression of left ventricular diastolic dysfunction and risk of heart failure. JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association. 2011;306(8):856–63. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuznetsova T, Herbots L, Jin Y, Stolarz-Skrzypek K, Staessen JA. Systolic and diastolic left ventricular dysfunction: from risk factors to overt heart failure. Expert review of cardiovascular therapy. 2010;8(2):251–8. doi: 10.1586/erc.10.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bluemke DA, Kronmal RA, Lima JA, et al. The relationship of left ventricular mass and geometry to incident cardiovascular events: the MESA (Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis) study. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2008;52(25):2148–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brower GL, Gardner JD, Janicki JS. Gender mediated cardiac protection from adverse ventricular remodeling is abolished by ovariectomy. Mol Cell Biochem. 2003;251(1–2):89–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jessup JA, Zhang L, Presley TD, et al. Tetrahydrobiopterin restores diastolic function and attenuates superoxide production in ovariectomized mRen2.Lewis rats. Endocrinology. 2011;152(6):2428–36. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-0061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang H, Jessup JA, Lin MS, Chagas C, Lindsey SH, Groban L. Activation of GPR30 attenuates diastolic dysfunction and left ventricle remodelling in oophorectomized mRen2.Lewis rats. Cardiovascular research. 2012;94(1):96–104. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvs090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Friedman GD, Cutter GR, Donahue RP, et al. CARDIA: study design, recruitment, and some characteristics of the examined subjects. Journal of clinical epidemiology. [Journal of clinical epidemiology] 1988;41(11):1105–16. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(88)90080-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Research on the menopause in the 1990s. Report of a WHO Scientific Group. World Health Organization technical report series [Technical Report] 1996;866:1–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pletcher MJ, Bibbins-Domingo K, Lewis CE, et al. Prehypertension during young adulthood and coronary calcium later in life. Annals of internal medicine. 2008;149(2):91–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-2-200807150-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wagenknecht LE, Cutter GR, Haley NJ, et al. Racial differences in serum cotinine levels among smokers in the Coronary Artery Risk Development in (Young) Adults study. American journal of public health. [American journal of public health] 1990;80(9):1053–6. doi: 10.2105/ajph.80.9.1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gidding SS, Liu K, Colangelo LA, et al. Longitudinal determinants of left ventricular mass and geometry: the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study. Circulation Cardiovascular imaging. 2013;6(5):769–75. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.112.000450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Devereux RB, Alonso DR, Lutas EM, et al. Echocardiographic assessment of left ventricular hypertrophy: comparison to necropsy findings. The American journal of cardiology. 1986;57(6):450–8. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(86)90771-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kishi S, Armstrong AC, Gidding SS, et al. Association of Obesity in Early Adulthood and Middle Age With Incipient Left Ventricular Dysfunction and Structural Remodeling: The CARDIA Study (Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults) JACC Heart failure. 2014;2(5):500–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2014.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Armstrong AC, Ricketts EP, Cox C, et al. Quality Control and Reproducibility in M-Mode, Two-Dimensional, and Speckle Tracking Echocardiography Acquisition and Analysis: The CARDIA Study, Year 25 Examination Experience. Echocardiography. 2015;32(8):1233–40. doi: 10.1111/echo.12832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Duzenli MA, Ozdemir K, Sokmen A, et al. The effects of hormone replacement therapy on myocardial performance in early postmenopausal women. Climacteric: the journal of the International Menopause Society. 2010;13(2):157–70. doi: 10.3109/13697130902929567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Duzenli MA, Ozdemir K, Sokmen A, et al. Effects of menopause on the myocardial velocities and myocardial performance index. Circulation journal: official journal of the Japanese Circulation Society. 2007;71(11):1728–33. doi: 10.1253/circj.71.1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaur M, Singh H, Ahuja GK. Cardiac performance in relation to age of onset of menopause. Journal of the Indian Medical Association. 2011;109(4):234–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schillaci G, Verdecchia P, Borgioni C, Ciucci A, Porcellati C. Early cardiac changes after menopause. Hypertension. 1998;32(4):764–9. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.32.4.764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kangro T, Henriksen E, Jonason T, et al. Effect of menopause on left ventricular filling in 50-year-old women. The American journal of cardiology. 1995;76(14):1093–6. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)80310-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaur M, Ahuja GK, Singh H, Walia L, Avasthi KK. Evaluation of left ventricular performance in menopausal women. Indian journal of physiology and pharmacology. 2010;54(1):80–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laughlin-Tommaso SK, Khan Z, Weaver AL, Schleck CD, Rocca WA, Stewart EA. Cardiovascular risk factors and diseases in women undergoing hysterectomy with ovarian conservation. Menopause. 2016;23(2):121–8. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000000506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Luoto R, Kaprio J, Reunanen A, Rutanen EM. Cardiovascular morbidity in relation to ovarian function after hysterectomy. Obstetrics and gynecology. 1995;85(4):515–22. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(94)00456-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosano GM, Vitale C, Marazzi G, Volterrani M. Menopause and cardiovascular disease: the evidence. Climacteric: the journal of the International Menopause Society. 2007;10(Suppl 1):19–24. doi: 10.1080/13697130601114917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhao Z, Wang H, Jessup JA, Lindsey SH, Chappell MC, Groban L. Role of estrogen in diastolic dysfunction. American journal of physiology Heart and circulatory physiology. 2014;306(5):H628–40. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00859.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gardner JD, Brower GL, Voloshenyuk TG, Janicki JS. Cardioprotection in female rats subjected to chronic volume overload: synergistic interaction of estrogen and phytoestrogens. American journal of physiology Heart and circulatory physiology. 2008;294(1):H198–204. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00281.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Endogenous H, Breast Cancer Collaborative G. Key TJ, et al. Circulating sex hormones and breast cancer risk factors in postmenopausal women: reanalysis of 13 studies. British journal of cancer. 2011;105(5):709–22. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kling JM, Lahr BA, Bailey KR, Harman SM, Miller VM, Mulvagh SL. Endothelial function in women of the Kronos Early Estrogen Prevention Study. Climacteric: the journal of the International Menopause Society. 2015;18(2):187–97. doi: 10.3109/13697137.2014.986719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harman SM, Black DM, Naftolin F, et al. Arterial imaging outcomes and cardiovascular risk factors in recently menopausal women: a randomized trial. Annals of internal medicine. 2014;161(4):249–60. doi: 10.7326/M14-0353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hodis HN, Mack WJ, Henderson VW, et al. Vascular Effects of Early versus Late Postmenopausal Treatment with Estradiol. The New England journal of medicine. 2016;374(13):1221–31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1505241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Terry KL, De Vivo I, Hankinson SE, Spiegelman D, Wise LA, Missmer SA. Anthropometric characteristics and risk of uterine leiomyoma. Epidemiology. [Research Support, NIH Extramural] 2007;18(6):758–63. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181567eed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Laughlin SK, Schroeder JC, Baird DD. New directions in the epidemiology of uterine fibroids. Seminars in reproductive medicine [Review] 2010;28(3):204–17. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1251477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kok HS, van Asselt KM, van der Schouw YT, et al. Heart disease risk determines menopausal age rather than the reverse. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2006;47(10):1976–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.12.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boynton-Jarrett R, Rich-Edwards J, Malspeis S, Missmer SA, Wright R. A prospective study of hypertension and risk of uterine leiomyomata. American journal of epidemiology. 2005;161(7):628–38. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.He Y, Zeng Q, Li X, Liu B, Wang P. The association between subclinical atherosclerosis and uterine fibroids. PloS one. [Research Support, Non-US Gov’t] 2013;8(2):e57089. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Phipps AI, Buist DS. Validation of self-reported history of hysterectomy and oophorectomy among women in an integrated group practice setting. Menopause. [Research Support, NIH Extramural Validation Studies] 2009;16(3):576–81. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31818ffe28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Digital Content 1. Image that illustrate differences in LV structure and function parameters among women with natural and surgical menopause. tif

Supplemental Digital Content 2. Image that illustrate differences in LV structure and function parameters among women with natural menopause, hysterectomy with ovarian conservation and hysterectomy with bilateral oophorectomy. tif

Supplemental Digital Content 3. Table that illustrates the no significant race and type of menopause interaction. doc