Abstract

Introduction

The marketing expenditure and sale of e-cigarettes increased sharply in the United States in recent years. However, little is known about neighborhood characteristics of point-of-sale (POS) e-cigarette advertising among tobacco stores. The purpose of this study was to examine socio-demographic characteristics of POS e-cigarette advertising among tobacco stores in the Omaha metropolitan area of Nebraska, USA.

Methods

Between April – June 2014, trained fieldworkers completed marketing audits of all stores that sell tobacco (n=463) in the Omaha metropolitan area and collected comprehensive e-cigarette advertising data of these stores. Based on the auditing information, we categorized tobacco stores based on e-cigarette advertising status. Logistic regression was used to examine the association between neighborhood socio-demographic factors and e-cigarette advertising among tobacco stores.

Results

251 (54.2%) of the 463 tobacco stores had e-cigarette advertisements. We found that neighborhoods of stores with POS e-cigarette advertising had higher per capita income (p<0.05), higher percentage of non-Hispanic Whites (p<0.005), and higher percentage of individuals with high school education (p<0.005) than neighborhoods of stores without POS e-cigarette advertising. There were negative associations between e-cigarette advertising and number of adolescents or number of middle/high school students. After adjusting for covariates, only percentage of non-Hispanic Whites remained a significant factor for e-cigarette advertising.

Conclusions

POS e-cigarette advertising among tobacco stores is related with neighborhood socioeconomic and demographic characteristics. Future studies are needed to understand how these characteristics are related with e-cigarette purchasing and e-cigarette prevalence among social groups.

Keywords: electronic cigarette, point-of-sale marketing, GIS, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status

INTRODUCTION

Electronic cigarettes (‘e-cigarettes’) are electronic devices that use electronic heating to generate smoke-liked aerosol for users to inhale. The aerosol generally contains nicotine and other added chemicals to simulate the flavor of tobacco smoke. Marketing expenditure of e-cigarette products has increased rapidly in recently years in the United States (Kim, Arnold, & Makarenko, 2014; Kornfield, Huang, Vera, & Emery, 2015). For example, media-based e-cigarette advertising expenditure increased from minimum in 2010 to $12 million in 2011, and skyrocketed to $124 million in 2014 (Kornfield et al., 2015). Although the U.S. Food and Drug Administration extended its tobacco regulations to e-cigarettes in 2016, there is no sign that the marketing momentum of e-cigarettes is going to be significantly influenced. Corresponding to the extensive marketing is the sharply increasing prevalence of e-cigarette use among various US population groups, including vulnerable groups such as adolescents (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2013; Corey et al., 2013; King, Alam, Promoff, Arrazola, & Dube, 2013; Rigotti et al., 2015; Vivek, Murthy, & Surgeon General, 2016; Zhu et al., 2013). For example, for middle-school and high-school students, the rates of ever e-cigarette use and past-30-day e-cigarette use have more than tripled from 2011 to 2015 (Singh, 2016).

Although e-cigarettes are becoming increasingly popular, there is lack of thorough understanding on their safety as well as benefits and harms to population health (Glynn, 2014; Lam, Nana, & Eastwood, 2014). Claimed benefits of e-cigarettes include their less harmful vapor than smoke from cigarette combustions, and their potential in helping current smokers quit and in avoiding exposure to secondhand cigarette smoke (Cahn & Siegel, 2011; Glynn, 2014; Wagener, Siegel, & Borrelli, 2012). However, previous studies were inconclusive on the effectiveness of e-cigarettes in smoking cessation (Adkison et al., 2013; Siegel, Tanwar, & Wood, 2011). At the same time, there are growing concerns on e-cigarettes’ potential harms to public health. For example, using e-cigarettes may exert negative effects in adolescent brain development and they could lure nicotine addicts to use conventional tobacco products (Barrington-Trimis et al., 2016; Corey et al., 2013; Dwyer, McQuown, & Leslie, 2009). E-cigarettes may also be used as a starting product by youths, young adults, and those who never smoked (Pearson, Richardson, Niaura, Vallone, & Abrams, 2012; Pokhrel et al., 2016; Vivek et al., 2016), which may increase the risk of nicotine addiction or tobacco smoking in the future (Dutra & Glantz, 2014; Gostin & Glasner, 2014; Grana, 2013). In the absence of evidence-based knowledge of benefits and harms of e-cigarettes, the exploding advertising may promote beliefs and behaviors that are detrimental to public health. Information on population exposure to e-cigarette marketing is therefore of great importance for understanding this potential public health problem.

This study examined socio-demographic characteristics of point-of-sale (POS) e-cigarette advertising among tobacco retail stores. Specifically, we wanted to understand if tobacco retail stores with POS e-cigarette advertising differ from those without POS e-cigarette advertising in terms of neighborhood socioeconomic and demographic factors, hoping to identify the trend of e-cigarette marketing among tobacco retail stores. We focused on retail stores because, although internet dominates the sale of e-cigarettes (Etter & Bullen, 2011) in recent years, retail sources are taking an increasing share of the market (Khan, Baker, Huang, & Chaloupka, 2014). It is projected that retail sources will account for 50% of e-cigarette sales in the near future (Robehmed, 2013). In addition, retail stores have been the major factor for e-cigarette marketing exposure among US youth (Mantey, Cooper, Clendennen, Pasch, & Perry, 2016). Therefore, understanding the characteristics of e-cigarette marketing among tobacco stores has important implications for e-cigarette prevalence studies and policy making works.

METHODOLOGY AND DATA

Tobacco Store Data

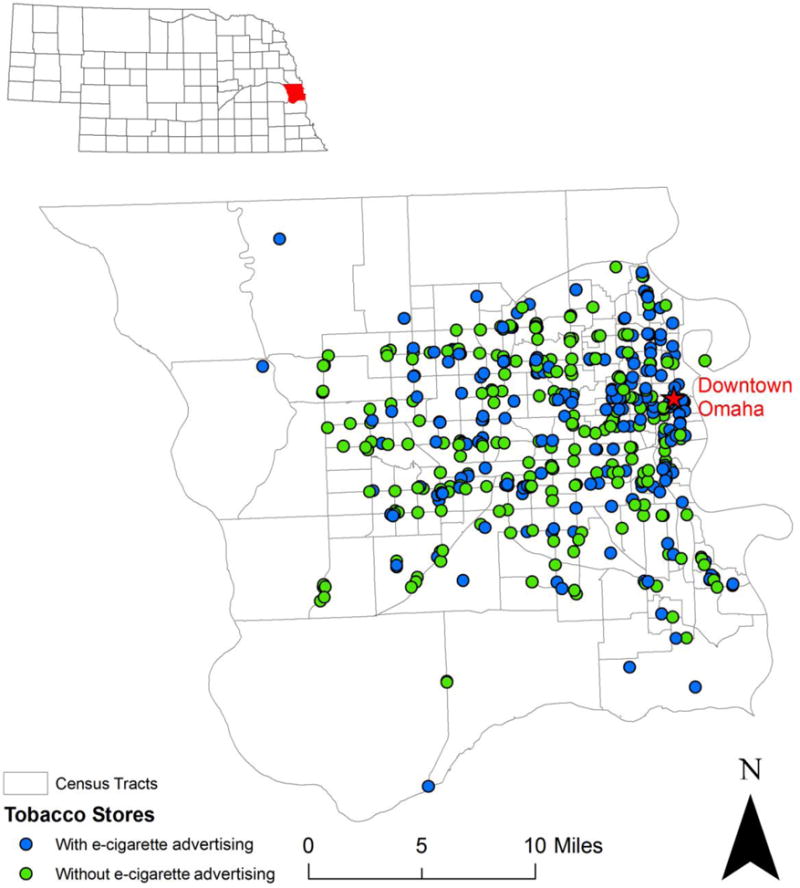

Our study site is the Omaha metropolitan area of Nebraska (shown in Figure 1) which includes Douglas and Sarpy counties, the two most populous counties of the state. We first obtained from the county/city licensing authorities a list of all stores (n=426) with tobacco licenses in 2013. The original table includes detailed information for each listed store, including store type, name, store address, phone number, and headquarter address (for chain stores). Following Rose et al. (2014), we classified the store types into seven categories, including gas and convenient store, supermarket and other grocery, tobacco store, liquor store, pharmacy and drug store, bar and pub, and others. We did not include stand-alone vape/e-cigarette stores in the study because these stores are not required to have a tobacco license in Nebraska and therefore are not included in the licensing database. In order to adjust for changes of tobacco license and tobacco availability of stores, we used Google Earth and Yellow Page to find all stores in the study area that fell in the store categories mentioned above but were not listed in the original table. This round of inspection allowed us to find an additional 58 stores in the study area. The phone number of each store was also collected from similar sources (e.g., Google, Yellow Page, and chain store websites). Then, a project coordinator called each store to verify if it currently sells tobacco or not. Stores in the original list were also called to verify current tobacco availability. This screening procedure confirmed a total of 463 stores that currently sell tobaccos, including 410 (96% of the original list) stores on the license list and 53 (91% of the original list) stores obtained from Google Earth/Yellow Page.

Figure 1.

Geographical distribution of e-cigarette marketing among tobacco-selling stores in the Omaha metropolitan area (Douglas and Sarpy counties) in 2014 (Note: a store was determined as having e-cigarette advertising if there is any evidence of total or exterior e-cigarette advertisement for that store)

E-cigarette Advertising Data

Between April–June 2014, two fieldworkers visited each of the 463 stores and collected comprehensive e-cigarette advertising data for each store. Before the data collection, the fieldworkers were trained using the website ‘StoreALERT’ developed by the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids and the Battelle Memorial Institute (Battelle Memorial Institute). Training procedures include learning training guides as well as practicing on a comprehensive virtual tour of a store with extensive tobacco advertising. During the training, fieldworkers learned how to use the ‘StoreALERT Report Card’ to record all aspects of e-cigarette advertising, including ads, promotions, placement and industry shelving. They were also instructed to record these e-cigarette specific advertising items from both the exterior and the interior of each store, enabling measurement of binary exterior and interior e-cigarette advertising variables for subsequent analyses. Questions listed in the ‘StoreALERT Report Card’ have been widely used in POS tobacco store auditing (Lee, Henriksen, Myers, Dauphinee, & Ribisl, 2014).

After entering a store, a fieldworker first introduced themselves to the clerk or manager and explained the purpose of the study. Then, information of all dimensions of e-cigarette marketing were recorded using the ‘StoreALERT Report Card’ which allowed us to calculate two indicators to reflect different dimensions of e-cigarette advertising: total exterior advertising and total advertising. Specifically, total exterior advertising was defined as the sum of all binary exterior advertising measures; and total advertising was calculated as the sum of total exterior advertising and total interior advertising.

Statistical Analysis

The major purpose of this study was to analyze neighborhood characteristics of e-cigarette advertising among tobacco stores. We wanted to examine if neighborhood socio-economic status (SES) and demographic factors differ between tobacco stores with e-cigarette advertising and those without e-cigarette advertising and, based on that information, to understand socio-demographic patterns of POS e-cigarette marketing among tobacco stores. Specifically, total advertising was used to examine if integrated e-cigarette advertising was related with neighborhood characteristics; and total exterior advertising was used to examine if exterior advertisements was placed to attract more passerby, especially vulnerable population groups. For each of the outcome variables, univariate logistic regression was first implemented to assess its relationship with individual neighborhood indicators. Then, a multivariate logistic regression was implemented to investigate the joint effect of factors that exhibited significant associations with e-cigarette advertising in the univariate analyses. For these regression analyses, the dependent variable was a binary indicator indicating the existence of total or exterior e-cigarette advertising of a store. For each store, the neighborhood is defined as a 2.5km-buffer area around the store. We used census tracts as the basic unit to comprise the neighborhood. Specifically, a census tract is considered within a store’s neighborhood if its population-weighted centroid (Wan, Zhan, Zou, & Chow, 2012) falls within the 2.5km-buffer area of that store. 2.5 km was used because this distance allows most of the stores to have at least one census tract within the buffer area. Then, socio-demographic indicators of all included census tracts are aggregated to represent neighborhood characteristics.

Socio-demographic indicators involved in the analyses include population size, racial/ethnic compositions (i.e., numbers and percentages of non-Hispanic Whites (NHW), non-Hispanic Blacks (NHB), and Hispanics), per capita income, percentage of individuals with at least high school education, age group (i.e., numbers and percentages of adolescents and young adults), number of middle-and-high schools, and number of middle-and-high school students. We used both numbers and percentages for some indicators because we wanted to understand if absolute numbers or relative percentages were related with e-cigarette advertising. Socioeconomic indicators were derived from the American Community Survey 2009–2013 five-year average dataset (U.S. Census Bureau, 2015). Demographic indicators were derived from the 2010 Census data (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010). We obtained the location and student number of each middle/high school from the school directory database of Nebraska (Nebraska Department of Education, 2014). Based on these indicators, we hoped to identify factors that are significantly associated with e-cigarette advertising. The entire project was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Nebraska Medical Center.

RESULTS

The in-store auditing found that more than a half (i.e., 251 out of 463, 54.2%) of the stores had e-cigarette advertising (shown in Figure 1). Table 1 shows the store-type composition of e-cigarette advertising. Convenience stores (with or without a gas station), ranked first in both number (n=128) and percentage (77.1%) for e-cigarette advertising. Only 51.6% of tobacco stores had e-cigarette advertising. 73% of pharmacies or drug stores that sold tobaccos had e-cigarette advertising.

Table 1.

E-cigarette advertising by store type in the Omaha metropolitan area

| Store Type | Number of stores | Number of stores with e-cigarette advertising |

|---|---|---|

| Gas and convenient store | 166 | 129 (77.7%) |

| Supermarket and other grocery | 124 | 60 (48.4%) |

| Tobacco store | 62 | 32 (51.6%) |

| Bar and pub | 55 | 3 (5.5%) |

| Pharmacy and drug stores | 37 | 27 (73%) |

| Liquor store | 7 | 0 (0%) |

| Other | 12 | 0 (0%) |

Table 2 shows neighborhood characteristics of stores with e-cigarette advertising and those without e-cigarette advertising. Generally, neighborhoods of stores with e-cigarette advertising have higher SES (i.e., per capital income and percent of high school graduates; p<0.05 for both indicators), higher percentage of NHWs and lower percentage of racial/ethnic minorities (p<0.05 for all three indicators). Other indicators (e.g., number and percentage of adolescents/young-adults, number of high schools, number of high school students) also vary slightly between the two categories of stores but t-test did not reveal any significant differences.

Table 2.

Neighborhood characteristics of stores with e-cigarette advertising and those without e-cigarette advertising in the Omaha metropolitan area (note: neighborhood average was calculated for population, numbers of high school graduates, adolescents, young adults, and racial/ethnic groups)

| Neighborhood Variables | Stores with e-cigarette advertising | Stores without e-cigarette advertising |

|---|---|---|

| Population | 24,789 | 26,487 |

| SES | ||

| Per Capita Income (in dollars)* | 26,201 | 24,521 |

| Number of high school graduates | 14,135 | 14,333 |

| Percentage of high school graduates* | 0.877 | 0.751 |

| Age | ||

| Number of adolescents | 1,587 | 1,687 |

| Number of young Adults | 7,295 | 8,188 |

| Percentage of adolescents (%) | 6.4 | 6.4 |

| Percentage of young adults (%) | 29.4 | 30.9 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic Whites (NHW) | 17,142 | 16,841 |

| Hispanics (H) | 3,469 | 4,448 |

| Non-Hispanic Blacks (NHB) | 2,783 | 3,636 |

| Percentage of NHW (%)* | 69.2 | 63.6 |

| Percentage of H (%)* | 14.0 | 16.8 |

| Percentage of NHB (%)* | 11.2 | 13.7 |

| School zone | ||

| Number of High Schools | 2.3 | 2.3 |

| Number of High School Students | 1,921 | 2,076 |

t-test: p < 0.05

Table 3 shows the result of univariate and multivariate logistic regressions for total advertising. As can be seen from the table, the regression results are generally consistent with the trends revealed in Table 2, as higher SES and proportion of NHWs corresponding to higher level of e-cigarette advertising. For example, e-cigarette advertising was related with higher per capita income (p<0.05), higher percentage of high school graduates (p<0.005), higher percentage of NHWs (p<0.005), and lower number and percentage of Hispanics and NHBs (p<0.05). We also found a weak, negative association between e-cigarette advertising and the number of adolescents (coefficient: −0.31, p<0.05), indicating that this age group is less exposed to POS e-cigarette advertisements than other age groups.

Table 3.

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression results for total advertising of e-cigarette among tobacco stores (note: for both types of regressions, the dependent variable is a binary variable indicating the existence of e-cigarette advertisement in the tobacco store; the neighborhood of a store is defined as the 2500 m radius around that store)

| Independent Variable | Univariate Regression | Multivariate Regression | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Coefficient | 95% CI | Coefficient | 95% CI | |

| Population (in 1,000) | −0. 02 | −0.03, 0.002 | ||

| SES | ||||

| Per Capita Income (in $1000) | 0.02* | 0.002, 0.05 | −0.03 | −0.08, 0.01 |

| Number of high school graduates (in 1,000) | −0.007 | −0.04, 0.03 | ||

| Percentage of high school graduates | 2.65** | 0.93, 4.37 | 1.03 | −2.33, 4.41 |

| Age Group | ||||

| Number of adolescents (in 1,000) | −0.31* | −0.60, −0.02 | 0.09 | −0.29, 0.48 |

| Number of young adults (in 1,000) | −0.04 | −0.09, 0.002 | ||

| Percentage of adolescents | −6.30 | −20.69, 8.10 | ||

| Percentage of young adults | −2.46 | −5.58, 0.65 | ||

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| Number of NHWs (in 1,000) | 0.005 | −0.02, 0.03 | ||

| Number of Hispanics (H) (in 1,000) | −0.04* | −0.08, −0.007 | ||

| Number of NHBs (NHB) (in 1,000) | −0.05* | −0.09, −0.002 | ||

| Percentage of NHW | 1.61** | 0.64, 2.57 | 2.50* | 0.03, 4.97 |

| Percentage of Hispanics | −1.58* | −2.91, −0.24 | ||

| Percentage of NHB | −1.43* | −2.75, −0.11 | ||

| School Zone | ||||

| Number of high schools | −0.03 | −0.14, 0.09 | ||

| Number of high school students (in 1,000) | −0.16* | −0.31, −0.02 | −0.14 | −0.31, 0.02 |

p<0.05

p<0.005

For the multivariate regression result in Table 3, independent variables include per capita income, percentage of high school graduates, number of adolescents, and percentage of NHW. Percentages and numbers of Hispanics and NHB were excluded to avoid multi-collinearity. As shown in Table 3, after incorporating all individual factors in the regression, only percentage of NHW remained significantly related with e-cigarette advertising (p<0.05).

Regressions based on exterior e-cigarette advertising found that only number of high school graduates (p<0.05) and percent of NHWs (p<0.01) are significantly related with exterior marketing (results not shown here but available upon request). After incorporating both factors into the regression, the significance disappeared for both of them.

DISCUSSION

This study analyzed the socio-demographic characteristics of e-cigarette marketing among tobacco-selling stores in the Omaha metropolitan area of Nebraska. To the best of our knowledge, this is among the first studies to investigate POS e-cigarette advertising in the United States and also the first study to audit a comprehensive list of tobacco stores for a large area. This comprehensive data revealed significant associations between e-cigarette advertising and race/ethnicity and SES. We also found that percentage of non-Hispanic Whites might be the most important factor for POS e-cigarette advertising in Omaha.

Our store auditing revealed that more than a half of tobacco stores had e-cigarette advertising. This percentage is higher than those reported by any studies. For example, a national study found that 31–34% of tobacco retail outlets sold e-cigarettes in 2012 (Rose et al., 2014). Ganz et al. (Ganz et al., 2014) found that 45% of tobacco stores in Central Harlem of New York City sold e-cigarettes. Although the three studies have different covering areas (e.g., national versus Central Harlem versus the Omaha metropolitan area), the increasing e-cigarette availability might be a reflection of the rapid growth of e-cigarette marketing among retail stores in the United States, which in turn highlights the importance of monitoring population exposure to POS e-cigarette advertising of tobacco stores.

Our findings regarding racial/ethnic and socioeconomic patterns of e-cigarette advertising echo previous findings on e-cigarette availability and perception (Khan et al., 2014; King et al., 2013; Pearson et al., 2012; Rigotti et al., 2015; Rose et al., 2014). For example, Khan et al. (Khan et al., 2014) found that POS e-cigarette is more prominent in neighborhoods with predominant white residents. NHWs and individuals with higher education attainment are more likely to know about e-cigarettes (King et al., 2013) and to consider e-cigarettes as less harmful than regular cigarettes (Pearson et al., 2012). Our studies, although focused on e-cigarette advertising instead of availability, found a similar focus on NHWs and high SES groups. These findings reveal a consistent marketing strategy of e-cigarettes in the United States.

Encouragingly, we did not find any sign of POS e-cigarette advertising (either total or exterior) towards adolescents or young adults. However, this does not necessarily mean this age group is free of excessive exposure to e-cigarette marketing. Recent studies showed that e-cigarette use among students in grades 6–12 has increased by 10 times during 2011–2015 (Lippert, 2015; Singh, 2016). Compared to store advertisements, media based exposure (e.g., television, Internet) to e-cigarette advertisements may had more influence on this vulnerable group (Duke et al., 2014). For example, youth and young adult exposure to television advertisements increased 256% and 321% respectively from 2011 to 2013 (Duke et al., 2014). Both media-based advertisements and retail store marketing have been related with e-cigarette use among youth in the United States (Mantey et al., 2016; Singh et al., 2016). All these evidences point to the necessity of continuous monitoring of youths’ exposure to e-cigarette marketing from both retail stores and the media.

With the absence of relevant data, few studies have explored the mechanism of how exposure to e-cigarette marketing influences e-cigarette use. Findings from studies on traditional tobacco may help ascertain this relationship. For example, exposure to POS marketing of tobacco is related with susceptibility to smoking (Feighery, Henriksen, Wang, Schleicher, & Fortmann, 2006), positive attitudes towards smoking (Paynter & Edwards, 2009), desire to use the advertised product (Wakefield, Germain, & Henriksen, 2008), and lower probability of smoking cessation (Germain, McCarthy, & Wakefield, 2010). These mechanisms may also apply to e-cigarettes. Since e-cigarettes are claimed to be less harmful than traditional tobacco products and effective in helping quit smoking, the levels of susceptibility, positive attitude, and desire to use advertised e-cigarettes might be even higher, which may lead to increased prevalence of e-cigarettes, especially among vulnerable population groups. Given this trend and the unproven benefits and potential harms of e-cigarettes, regulations on e-cigarette marketing are needed.

CONCLUSION

This study found significant associations between tobacco store e-cigarette advertising and neighborhood SES and racial/ethnic factors. Unlike the advertising of traditional cigarettes, POS e-cigarette advertising was not targeted at racial/ethnic minorities or low SES neighborhoods. However, given the rapid increase of e-cigarette advertising among retail stores, it is necessary to monitor POS e-cigarettes advertising, its sale, and its use among different social groups.

Acknowledgments

Sources of financial support: NIH (R01CA166156)

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethnical Standards:

Conflicts of interest: The authors identify no conflicts of interest in this work.

Contributor Information

Neng Wan, Assistant Professor, University of Utah, 332 S 1400 E, RM. 217, Salt Lake City, UT 84112-9155, USA, Tel: 801-585-3972, Fax: 801-581-8218.

Mohammad Siahpush, Professor, University of Nebraska Medical Center, 984365 Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE 68198-4365, USA, Tel: 402-559-3437, Fax: 402-559-3773.

Raees A. Shaikh, University of Oklahoma Health Science Center, 1100 N. Lindsay, Oklahoma City, OK 73104, USA, Tel: 405-271-8001, Fax: 405-271-2808.

Molly McCarthy, University of Nebraska Medical Center, 984365 Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE 68198-4365, USA, Tel: 402-559-3437, Fax: 402-559-3773.

Athena Ramos, University of Nebraska Medical Center, 984365 Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE 68198-4365, USA, Tel: (402) 559-2095, Fax: 402-559-3773.

Antonia Correa, University of Nebraska Medical Center, 984365 Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE 68198-4365, USA., Tel: (402) 559-3670, Fax: 402-559-3773.

References

- Adkison SE, O’Connor RJ, Bansal-Travers M, Hyland A, Borland R, Yong H-H, Hammond D. Electronic nicotine delivery systems: international tobacco control four-country survey. American journal of preventive medicine. 2013;44(3):207–215. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrington-Trimis JL, Berhane K, Unger JB, Cruz TB, Urman R, Chou CP, McConnell R. The E-cigarette Social Environment, E-cigarette Use, and Susceptibility to Cigarette Smoking. The Journal of adolescent health: official publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. 2016;59(1):75–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battelle Memorial Institute. StoreALERT report card: Advocates Limiting Exposure to Retail Tobacco [Google Scholar]

- Cahn Z, Siegel M. Electronic cigarettes as a harm reduction strategy for tobacco control: a step forward or a repeat of past mistakes? Journal of public health policy. 2011;32(1):16–31. doi: 10.1057/jphp.2010.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Notes from the Field: Electronic Cigarette Use Among Middle and High School Students — United States, 2011–2012: MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly RepNotes from the Field: Electronic Cigarette Use Among Middle and High School Students — United States, 2011–2012: MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corey C, Wang B, Johnson SE, Apelberg B, Husten C, King BA, Dube SR. Electronic Cigarette Use Among Middle and High School Students - United States, 2011–2012. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2013;62(35):729–730. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duke JC, Lee YO, Kim AE, Watson KA, Arnold KY, Nonnemaker JM, Porter L. Exposure to Electronic Cigarette Television Advertisements Among Youth and Young Adults. Pediatrics. 2014;134(1):E29–E36. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-0269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutra LM, Glantz SA. Electronic cigarettes and conventional cigarette use among US adolescents: a cross-sectional study. JAMA pediatrics. 2014;168(7):610–617. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.5488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer JB, McQuown SC, Leslie FM. The dynamic effects of nicotine on the developing brain. Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2009;122(2):125–139. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etter JF, Bullen C. Electronic cigarette: users profile, utilization, satisfaction and perceived efficacy. Addiction. 2011;106(11):2017–2028. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03505.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feighery EC, Henriksen L, Wang Y, Schleicher NC, Fortmann SP. An evaluation of four measures of adolescents’ exposure to cigarette marketing in stores. Nicotine & tobacco research: official journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco. 2006;8(6):751–759. doi: 10.1080/14622200601004125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganz O, Cantrell J, Moon-Howard J, Aidala A, Kirchner TR, Vallone D. Electronic cigarette advertising at the point-of-sale: a gap in tobacco control research. Tobacco control, tobaccocontrol-2013-051337. 2014 doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germain D, McCarthy M, Wakefield M. Smoker sensitivity to retail tobacco displays and quitting: a cohort study. Addiction. 2010;105(1):159–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glynn TJ. E-cigarettes and the future of tobacco control. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2014;64(3):164–168. doi: 10.3322/caac.21226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gostin LO, Glasner AY. E-cigarettes, vaping, and youth. Jama. 2014;312(6):595–596. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.7883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grana RA. Electronic cigarettes: a new nicotine gateway. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52(2):135–136. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan T, Baker D, Huang J, Chaloupka F. Changes in E-Cigarette Availability over Time in the United States: 2010–2012 - A BTG Research Brief. 2014 Retrieved from Chicago, IL. [Google Scholar]

- Kim AE, Arnold KY, Makarenko O. E-cigarette Advertising Expenditures in the US, 2011–2012. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2014;46(4):409–412. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King BA, Alam S, Promoff G, Arrazola R, Dube SR. Awareness and ever-use of electronic cigarettes among US adults, 2010–2011. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2013;15(9):1623–1627. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornfield R, Huang J, Vera L, Emery SL. Rapidly increasing promotional expenditures for e-cigarettes. Tobacco control. 2015;24(2):110–111. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam DCL, Nana A, Eastwood PR. Electronic cigarettes:‘Vaping’ has unproven benefits and potential harm. Respirology. 2014;19(7):945–947. doi: 10.1111/resp.12374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JGL, Henriksen L, Myers AE, Dauphinee AL, Ribisl KM. A systematic review of store audit methods for assessing tobacco marketing and products at the point of sale. Tobacco control. 2014;23(2):98–106. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippert AM. Do adolescent smokers use e-cigarettes to help them quit? The sociodemographic correlates and cessation motivations of US adolescent e-cigarette use. American Journal of Health Promotion. 2015;29(6):374–379. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.131120-QUAN-595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantey DS, Cooper MR, Clendennen SL, Pasch KE, Perry CL. E-Cigarette Marketing Exposure Is Associated With E-Cigarette Use Among US Youth. The Journal of adolescent health: official publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. 2016;58(6):686–690. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nebraska Department of Education. School Directory, 2014–2015. 2014 http://educdirsrc.education.ne.gov/QuickMain.aspx.

- Paynter J, Edwards R. The impact of tobacco promotion at the point of sale: a systematic review. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2009;11(1):25–35. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntn002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson JL, Richardson A, Niaura RS, Vallone DM, Abrams DB. e-Cigarette Awareness, Use, and Harm Perceptions in US Adults. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102(9):1758–1766. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2011.300526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pokhrel P, Fagan P, Herzog TA, Chen Q, Muranaka N, Kehl L, Unger JB. E-cigarette advertising exposure and implicit attitudes among young adult non-smokers. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2016;163:134–140. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigotti NA, Harrington KF, Richter K, Fellows JL, Sherman SE, Grossman E, Ylioja T. Increasing Prevalence of Electronic Cigarette Use Among Smokers Hospitalized in 5 US Cities, 2010–2013. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2015;17(2):236–244. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robehmed N. E-cigarette sales surpass $1 billion as Big Tobacco moves in. 2013 http://www.forbes.com/sites/natalierobehmed/2013/09/17/e-cigarette-sales-surpass-1-billion-as-big-tobacco-moves-in/#c16ab75548e9.

- Rose SW, Barker DC, D’Angelo H, Khan T, Huang J, Chaloupka FJ, Ribisl KM. The availability of electronic cigarettes in U.S. retail outlets, 2012: results of two national studies. Tobacco control. 2014;23(Suppl 3):iii 10–16. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel MB, Tanwar KL, Wood KS. Electronic cigarettes as a smoking-cessation tool: results from an online survey. American journal of preventive medicine. 2011;40(4):472–475. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh T. Tobacco use among middle and high school students—United States, 2011–2015. MMWR Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2016;65 doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6514a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh T, Agaku IT, Arrazola RA, Marynak KL, Neff LJ, Rolle IT, King BA. Exposure to Advertisements and Electronic Cigarette Use Among US Middle and High School Students. Pediatrics. 2016;137(5):e20154155. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-4155. Article No.: e20154155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U. S. C. Bureau, editor. U.S. Census Bureau. Census Data 2010. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. Five Year Estimates. U.S. Census Bureau; 2015. American Community Survey 2009–2013. [Google Scholar]

- Vivek H, Murthy MD, Surgeon General, U. S. E-Cigarette Use Among Youth and Young Adults A Major Public Health Concern. 2016 doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.4662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagener TL, Siegel M, Borrelli B. Electronic cigarettes: achieving a balanced perspective. Addiction. 2012;107(9):1545–1548. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.03826.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakefield M, Germain D, Henriksen L. The effect of retail cigarette pack displays on impulse purchase. Addiction. 2008;103(2):322–328. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan N, Zhan FB, Zou B, Chow E. A relative spatial access assessment approach for analyzing potential spatial access to colorectal cancer services in Texas. Applied Geography. 2012;32(2):291–299. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu SH, Gamst A, Lee M, Cummins S, Yin L, Zoref L. The Use and Perception of Electronic Cigarettes and Snus among the US Population. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e79332. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079332. Article No.: e79332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]