Abstract

Background

The goal of the present study was to evaluate the expression and serine 9 phosphorylation of glycogen synthase kinase (GSK-3β) within the adult hippocampal dentate gyrus (DG) in a preclinical mouse model of fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD). GSK-3β is a multifunctional kinase that modulates many hippocampal processes affected by gestational alcohol, including synaptic plasticity and adult neurogenesis. GSK-3β is a constitutively active kinase that is negatively regulated by phosphorylation at the serine-9 residue.

Methods

We utilized a well-characterized limited access “drinking-in-the-dark” paradigm of prenatal alcohol exposure (PAE) and measured p(Ser9)GSK-3β and total GSK-3β within adult dentate gyrus by western blot analysis. In addition, we evaluated the expression pattern of both p(Ser9)GSK-3β and total GSK-3β within the adult hippocampal dentate of PAE and control mice using high resolution confocal microscopy.

Results

Our findings demonstrate a marked 2.0-fold elevation of p(Ser9)GSK-3β in PAE mice, concomitant with a more moderate 36% increase in total GSK-3β. This resulted in an approximate 63% increase in the p(Ser9)GSK-3β/GSK-3β ratio. Immunostaining revealed robust GSK-3β expression within Cornu Amonis (CA) pyramidal neurons, hilar mossy cells and a subset of GABAergic interneurons, with low levels of expression within hippocampal progenitors and dentate granule cells (DGCs).

Conclusions

These findings suggest that PAE may lead to a long-term disruption of GSK-3β signaling within the dentate gyrus, and implicate mossy cells, GABAergic interneurons and CA primary neurons as major targets of this dysregulation.

Keywords: FASD, GSK, hippocampal neurogenesis, hippocampal plasticity, hilar mossy cells

INTRODUCTION

Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD) is a highly prevalent condition (2–5% in the US) associated with a broad range of neurobehavioral deficits, from mental retardation following high dose gestational alcohol exposure (fetal alcohol syndrome) to more subtle behavioral problems following moderate gestational exposure (Guerri et al., 2009, Streissguth and O’Malley, 2000). Common behavioral problems in clinical FASD include those associated with cognition and mood (Mattson et al., 2011), which may be due in part to the teratogenic effects of alcohol on the developing hippocampus, a brain region known to play a pivotal role in cognition, stress and mood regulation (Berman and Hannigan, 2000). Preclinical studies in rodent models have demonstrated that exposure to even moderate levels of alcohol during gestation results in long-term impairments of hippocampal function. These include persistent alterations in hippocampal synaptic plasticity (Fontaine et al., 2016, Krawczyk et al., 2016) as well as impaired capacity for adult hippocampal neurogenesis (Gil-Mohapel et al., 2010). Despite the high prevalence of FASD, there are few therapeutic options for mitigating the neurobehavioral consequences of this disorder.

The hippocampal dentate gyrus represents one of few brain regions where neurogenesis continues throughout life. New dentate granule neurons are continuously generated from a pool of neural stem and progenitor cells located within the dentate subgranular zone (SGZ), a region bordering the dentate granule cell layer and hilar region. Adult-generated, immature dentate granule neurons display unique connectivity, hyper-excitability and plasticity during a critical period of maturation between 4–8 weeks of cellular age, and confer an extreme form of structural plasticity that can modify the hippocampal trisynaptic network (Piatti et al., 2013, Sailor et al., 2017). Although immature dentate granule cells only constitute an estimated 5–6% of the total dentate granule cell population, these cells exert profound effects on hippocampal network activity, and are critical for encoding certain forms of episodic memory (Gu et al., 2012, Nakashiba et al., 2012), in addition to regulating stress and mood (Cameron and Glover, 2015).

Many studies in various preclinical rodent models of FASD have demonstrated that prenatal alcohol exposure (PAE) exerts long-lasting impairments in adult hippocampal neurogenesis (Boehme et al., 2011, Choi et al., 2005, Gil-Mohapel et al., 2010, Ieraci and Herrera, 2007, Kajimoto et al., 2013, Klintsova et al., 2007, Redila et al., 2006, Uban et al., 2010). Using voluntary drinking paradigms to model PAE in mice, we previously demonstrated that exposure to moderate levels of alcohol during gestation has no effect on the production of adult-generated dentate granule neurons when mice are housed under standard conditions, but leads to marked impairment in the ability to mount a neurogenic response to enriched environment (Choi et al., 2005, Kajimoto et al., 2013). This outcome equates to approximately 50% fewer adult-generated dentate granule neurons in PAE compared to control mice under enriched living conditions. Interestingly, this neurogenic defect is not due to a change in the size of the SGZ progenitor pool but is primarily due to impaired activity-dependent survival and integration of newborn dentate granule neurons into the hippocampal network (Choi et al., 2005, Kajimoto et al., 2013), and is correlated with altered synaptic activity in newborn cells (Kajimoto et al., 2016). Although it is unknown whether postnatal neurogenic capacity is impaired in clinical FASD, studies using structural neuroimaging techniques in FASD individuals have demonstrated reductions in hippocampal volume (Autti-Ramo et al., 2002, Riikonen et al., 1999, Willoughby et al., 2008) and impaired temporal lobe network function (Sowell et al., 2007) that are correlated with hippocampal-related memory deficits. Recent confirmation that robust hippocampal neurogenesis also occurs throughout life within human brain (Spalding et al., 2013) further underscores the need to elucidate how gestational alcohol exposure impacts postnatal neurogenesis and hippocampal neurogenic function.

In the present study, we asked whether dysregulation of glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK-3β) may contribute to impaired neurogenic function in PAE mice by measuring GSK-3β expression and serine 9 phosphorylation status in our PAE model under conditions of enriched environment, a condition in which hippocampal neurogenesis is known to be impaired. GSK-3β is a constitutively active serine protein kinase highly expressed in the brain, that is negatively regulated by phosphorylation at the Ser9 residue (Kaidanovich-Beilin and Woodgett, 2011). GSK3 activity plays an essential role in neurogenesis during embryonic development (Kim et al., 2009). Although many studies have also demonstrated an important role of GSK-3β in adult hippocampal neurogenesis, the nature of this regulation under physiological conditions remains ambiguous. For example, genetic overexpression of GSK-3β within the hippocampus during postnatal development can promote or impair adult hippocampal neurogenesis in mice, depending on the transcriptional promoter used to drive genetic overexpression (Fuster-Matanzo et al., 2013, Jurado-Arjona et al., 2016). Similarly, enriched environment and voluntary exercise, which both increase neurogenesis in normal mouse hippocampus, drive GSK-3β activity in opposite directions (Hu et al., 2013, Zang et al., 2017). Therapeutically, abnormally high GSK-3β activity has been implicated as a causal factor in many neurological disorders, and pharmacological inhibition of GSK-3β has been shown to rescue impaired neurogenesis in a mouse model of Fragile X syndrome (Guo et al., 2012).

Here, we tested the hypothesis that gestational alcohol exposure disrupts GSK-3β expression and serine-9 phosphorylation within the adult hippocampal dentate gyrus under conditions of enriched environment. For these studies we utilized a well-characterized limited access voluntary consumption paradigm, in which average daily peak maternal blood alcohol levels reach ~80 mg/dl throughout gestation, without alterations in litter size, pup weights or maternal care (Brady et al., 2012). Adult PAE offspring generated using this model display impaired hippocampal-dependent learning (Brady et al., 2012), impaired NMDA-dependent LTP (Brady et al., 2013) and an impaired neurogenic response to environmental enrichment (Kajimoto et al., 2013, Kajimoto et al., 2016). GSK-3β expression and phosphorylation were evaluated within the dentate gyrus of the PAE offspring using Nestin-CreERT2:tdTomato bitransgenic mice, in which adult hippocampal progenitors and their progeny were visually identified by reporter gene expression (Kajimoto et al., 2013). We compared total GSK-3β and p(Ser9)GSK-3β levels by western blot analysis and cellular expression patterns by high resolution confocal fluorescence microscopy. Our findings demonstrate marked elevation of p(Ser9)GSK-3β, concomitant with a moderate increase in total GSK-3β and significant elevation of the p(Ser9)GSK-3β/total GSK-3β ratio in PAE mice. Based on the cellular pattern of GSK-3β expression, the increased Ser9 phosphorylation of GSK-3β likely occurs primarily within hilar mossy cells, GABAergic interneurons, or CA3/4 neurons, and not in adult-generated DGCs where expression appears relatively weak. These observations suggest that GSK-3β may be an important therapeutic target in PAE, and warrant further investigation regarding its causal role underlying impaired neurogenic function in this preclinical mouse model of FASD.

METHODS

Animals

All animal procedures were performed in accordance with the University of New Mexico Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines. Mice were housed under reverse 12-hr dark/12-hr light cycle (lights off at 08:00 h). Experiments were performed using Nestin-CreERT2: tdTomato bitransgenic mice for identification of adult hippocampal progenitors and their downstream progeny. These mice are homozygous at both the Nestin-CreERT2 (Lagace et al., 2007) and Ai9 (RCL-tdT) transgene loci (Madisen et al., 2010) maintained on the C57BL/6J background strain. The mice harbor a loxP-flanked STOP cassette at the Gt(Rosa)26Sor locus, which prevents transcription of CAG promoter-driven red fluorescent variant (tdTomato) except following Cre-mediated recombination. Tamoxifen administration to Nestin-CreERT2:tdTomato bitransgenic mice results in Cre-mediated recombination and reporter expression within nestin+ hippocampal progenitors and all subsequent progeny (Lagace et al., 2007). In separate experiments, we utilized (VGAT)-Venus transgenic mice, which express a green fluorescent variant (Venus) reporter gene under transcriptional control of the endogenous mouse vesicular GABA transporter (VGAT) promoter (Wang et al., 2009).

Prenatal Alcohol Exposure

PAE offspring were generated using a limited access “drinking-in-the-dark” gestational ethanol exposure paradigm as previously described (Brady et al., 2012). Briefly, 60 day old nestin-CreERT2:tdTomato female mice were subjected to 5 day ramp up period in which the normal drinking water was replaced with 0.066% saccharin containing 0% (2 days), 5% (2 days) and 10% ethanol for 4 hrs per day from 10:00–14:00. The mice were maintained on this drinking regimen for 2 weeks prior to pregnancy and throughout pregnancy. Female mice offered 0.066% saccharin without ethanol during the same periods were used as controls. After one week of drinking 10% ethanol, females were placed into the cage of a singly housed male for 2 hr per day from 14:00–16:00 for 5 consecutive days and returned to home cage after the 2 hr mating session. At birth, ethanol and saccharin concentrations were halved every two days with a return to normal drinking water on day 5. Consumption volume during the 4 hr access period, as determined for each dam beginning after one week of drinking 10% alcohol, was 5.64 ± 0.885 gm EtOH/kg body weight, n=5. We previously demonstrated that blood alcohol concentrations are directly correlated to the amount of ethanol consumed over the 4 hr drinking period (Brady et al., 2012). Based on this correlation, we estimate average daily BACs of 80–90 mg/dL throughout gestation for the current study. All offspring were sex-segregated at weaning. One week after weaning, all mice received daily intraperitoneal (i.p.) injections of tamoxifen (TAM; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) at the dose of 180 mg/kg (dissolved in 10% EtOH/90% sunflower oil) for five consecutive days as previously described (Kajimoto et al., 2013). Five days following the final TAM injection, gender-segregated pups were placed in enriched environment (EE) for 8 weeks, as described previously (Kajimoto et al., 2013). Mice were then sacrificed at the end of the 8 weeks of EE for biochemical and histological analysis of GSK-3β expression. All mice were approximately 3 months of age at the time of sacrifice. Offspring from five EtOH and four Sac litters were used for western blot analysis across two separate experiments. Four littermates for each treatment group were used for histology, across two EtOH and four Sac litters.

Western Blot Analysis

Mice were sacrificed by decapitation following light isoflurane anesthesia. Brains were immediately removed from calvaria and placed in cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Using a dissecting microscope, the dentate gyrus was microdissected from the hippocampus bilaterally and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen (Hagihara et al., 2009). Tissue was homogenized in 100 μl of buffer containing the following components: 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH7.4, 1 mM EDTA, 320 mM sucrose, 20 mM β-glycerophosphate, 20 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 10 mM sodium fluoride, 200 μM sodium orthovanadate, and protease inhibitor cocktail (1:1000, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). The homogenates were centrifuged twice at 1000 × g for 6 min at 4°C) and the supernatants were combined as a “post-nuclear lysate”. Protein concentrations were determined using the Bradford protein assay (BioRad, Hercules, CA) and subjected to analysis by routine western immunoblotting as previously described (Diaz et al., 2014, Goggin et al., 2014). Briefly, samples were diluted in NuPAGE LDS Sample Buffer (#NP0007, InVitrogen, Grand Island, NY), heated at 70°C for 5 minutes and loaded (10 or 20 μg protein/well) into 4–12% Bis-Tris precast gels (#NP0336, InVitrogen). Proteins were separated by electrophoresis at 150V for 50 minutes and electro-blotted onto Immunobilon-FL membranes overnight at 30V. Membranes were blocked using Odyssey™ blocking buffer (#927–40000, LI-CORE Biosciences, Lincoln, NE) for 1 hr at room temperature, washed with PBS containing 0.1% Tween-20 (4 × 5 minutes) and incubated in primary antibodies for 4–5 hr at room temperature. The membranes were washed with PBS-0.1% Tween-20 (4 × 5 minutes) and incubated with fluorescently labeled secondary antibodies for 1 hr at room temperature. The following primary antibodies were used in this study: Anti-GSK-3β (3D10) mouse mAB (1:1000 dilution; #9832, Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA), Anti-phospho-GSK-3β (Ser9) (D85E12) XP rabbit mAb (1:1000 dilution; #5558, Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA). Simultaneous detection of total and phosphorylated GSK-3β were performed on each blot using IRDye 680RD goat anti-mouse (1:10,000 dilution; #926–6807, LI-COR Biosciences) and 800CW goat anti-rabbit antibody (1:10,000 dilution; #926–32211, LI-COR Biosciences), respectively. The blots were scanned using two-channel infrared direct detection (Odyssey Imaging System, LI-COR Biosciences) and quantified using Image Studio (version 3.1, LI-COR Biosciences). Coomassie staining was performed as a within-lane loading control as previously described (Goggin et al., 2014). Following immunodetection, membranes were stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250 (#161–0400, Bio-Rad) and quantified using Quantity One 1-D analysis software (Bio-Rad). For each lane, the target protein signal was corrected against the Coomassie stain to account for any loading discrepancies. Each individual immunoblot included samples from at least 3 separate control and 3 separate PAE mice. All data are expressed as means ± SEM, normalized to within blot controls. Sample size was defined as the number of animals taken across separate litters for each treatment group, because statistical variance was greatest across individual pups compared to that across individual litters (s2pups = 4264, s2litters = 3357). Both sexes were included in all analyses (3 males and 8 females for EtOH; 3 males and 7 females for SAC). All data were statistically analyzed by two-tailed Student’s t-test with Welch’s correction for unequal variance using Graphpad PRISM Software version 6.03.

Immunohistochemistry

Mice were deeply anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (150 mg kg−1, i.p.; Fort Dodge Animal Health, Fort Dodge, IA), followed by transcardial perfusion with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing procaine (0.1%) and heparin (2 U mL−1) and 4% paraformaldehyde (w/v) in 0.1 M PBS. Brains were postfixed overnight, cryoprotected with 30% sucrose (w/v) in 0.1 M PBS and sectioned in the coronal plane (30 μm thickness) using a freezing sliding knife microtome (AO Instrument Co., Buffalo, NY). Immunostaining was performed on floating sections using anti-GSK-3β (3D10) mouse mAB (1:500 dilution; #9832, Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA), or anti-phospho-GSK-3β (Ser9) (D85E12) XP rabbit mAb (1:500 dilution; #5558, Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA). Immunofluorescence was visualized using biotinylated goat anti-mouse or biotinylated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody with tyramide amplification using the Tyramide-Plus amplification system (PerkinElmer Life Sciences, Boston, MA) as previously described (Lagace et al., 2007, Li et al., 2010). All images represent z-stack projection images acquired using LASX acquisition software with a Leica DMi8 TCS SP8 confocal microscope (Buffalo Grove, IL). Images were tiled using a 20X objective, and stitched using Leica LASC software or using Adobe Photoshop. Single higher power z-stack projection images were acquired with a 63X objective.

RESULTS

PAE leads to increased phosphorylation of GSK3β-Ser9 in dentate gyrus of adult mice

To evaluate the expression levels of p(Ser9)GSK-3β relative to total GSK-3β, western immunoblot analysis was performed using antibodies that detect endogenous GSK-3β only when phosphorylated at Ser9 or that detect endogenous GSK-3β independent of phosphorylation status (p(Ser9)GSK-3β vs. total GSK-3β, respectively). Each primary antibody was produced in a distinct species, allowing for the analysis of both p(Ser9)GSK-3β and total GSK-3β within the same membrane using species-specific secondary antibodies conjugated to distinct fluorophores. The immunoblots displayed distinct single bands at the appropriate molecular weight confirming lack of cross-reactivity with GSK-3α, as previously documented by others (Chao et al., 2014, Hui et al., 2014, Mirlashari et al., 2012, Pardo et al., 2016). As shown in Figure 1, PAE mice displayed a significant 36% increase in total GSK-3β expression within dentate gyrus (t=2.38, df=10.83, p=0.037), and a more marked 100% increase in the level of p(Ser9)GSK-3β (t=3.55, df=16.36, p=0.003). This resulted in an approximate 63% increase in the mean ratio of inactive p(Ser9)GSK-3β to total GSK-3β in PAE mice compared to controls (t=2.14, df=18.01, p=0.045).

Fig. 1. Increased p(Ser9) GSK-3β in adult hippocampal dentate gyrus from PAE mice.

Comparison of total GSK-3β (A) and p(Ser9)GSK-3β (B) as assayed by Western immunoblot analysis of DG homogenates from control vs. PAE mice. Representative immunoblot obtained from 3 separate mice per treatment group is depicted below each graph. (C) Ratio of p(Ser9)GSK-3β/total GSK-3β in control vs. PAE adult DG homogenates. *p=0.04, **p=0.003. Pups from individual litters are color coded for each treatment group (n=11 PAE across 5 litters; n=10 SAC across 4 litters).

GSK-3β expression pattern within the hippocampal dentate of PAE and control mice

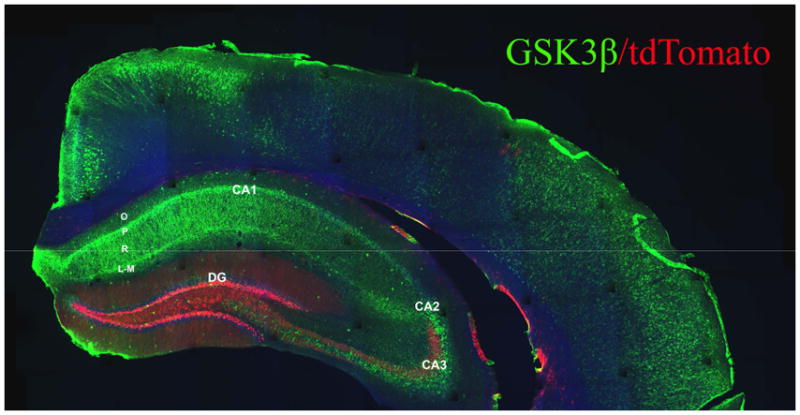

High resolution confocal microscopy was used to assess the distribution of GSK-3β immunofluorescence within the dentate gyrus of PAE and control mice. For this analysis, we utilized Nestin-CreERT2:tdTomato mice in which adult-generated DGCs were visualized by tamoxifen-induced reporter gene expression in hippocampal progenitors and their progeny. Figure 2 depicts the overall pattern of total GSK3β immunofluorescence and tdTomato reporter expression throughout a coronal brain section at the level of the dorsal hippocampus of a control mouse. As anticipated, tdTomato fluorescence intensely labeled a subset of hippocampal DGCs within the dentate gyrus. However, GSK-3β immunofluorescence appeared relatively faint within the dentate granule cell layer, compared to CA hippocampal pyramidal neurons and fibers of the stratum radiatum and lacunosum-moleculare which were intensely GSK-3β+. GSK-3β expression was also intense within neurons in the outer layers of the cerebral cortex.

Fig. 2. Hippocampal expression pattern of GSK-3β.

Montage confocal image of coronal section from tamoxifen-treated nestin-CreERT2:tdTomato mouse immunofluorescently labeled for GSK-3β (green). Adult-generated DGCs are tdTomato+ (red). Note pattern of intense GSK-3β expression within hippocampal CA pyramidal cell layers, within processes of stratum radiatum and stratum lacunosum-moleculare, and within interneurons scattered throughout all regions of hippocampus. Intense GSK-3β immunofluorescence is also observed within pyramidal neurons of the cerebral cortex. GSK-3β immunofluorescence was only dimly visable within the granule cell layer of the dentate gyrus. Note the presence of tdTomato+ mossy fibers from adult-generated DGCs within the hilar/CA3 regions of DG. Abbreviations: DG, dentate gyrus; O, stratum oriens; P, CA pyramidal layer; R, stratum radiatum; L-M, stratum lacunosum-moleculare.

The relationship of tdTomato reporter expression and GSK-3β immunofluorescence within the dentate gyrus of PAE and control mice is shown at higher power magnification in Figure 3. Consistent with our previous reports, the overall number of adult-generated DGCs (tdTomato+) appeared much lower in PAE mice compared to controls (Choi et al., 2005, Kajimoto et al., 2013). GSK-3β immunofluorescence only faintly labeled DGCs, and was only barely detectable within tdTomato+ DGCs. However, GSK-3β immunofluorescence was readily detectable within interneurons scattered throughout the hilus and within scattered cells along the dentate granule cell layer-hilus border. There were no apparent differences in the distribution patterns of GSK-3β expression between PAE vs. control mice. As shown in Figure 4, the pattern of p(Ser9)GSK-3β immunofluorescence was similar to that of total GSK3β, although fewer immunofluorescent cells were detectable overall. Similarly, there were no apparent differences in the distribution patterns of p(Ser9)GSK-3β immunofluorescence between PAE vs. control mice, although p(Ser9)GSK-3β immunofluorescence appeared visibly more intense in PAE mice, consistent with the western blot data (Figure 4A and B).

Fig. 3. Distribution of GSK-3β immunofluorescence in adult DG of control and PAE mice.

Confocal images through DG of dorsal hippocampus from control (A) and PAE (B) mice. GSK-3β immunofluorescence is depicted in green, whereas tdTomato fluorescence in adult-generated DGCs is depicted in red. Cell nuclei are depicted in blue (DAPI nuclear stain). tdTomato+ mossy fibers can also be seen in hilar region at this magnification. Boxed areas in A and B are shown at higher magnification in A1 and B1, respectively. Intense GSK-3β expression is observed in scattered cells throughout the hilus, SGZ and granule cell layer (arrows) with little expression apparent within tdTomato+ adult-generated DGCs. Note that the overall distribution of GSK-3β appears unchanged by PAE, whereas the number of adult-generated DGCs appears less in PAE mice. Abbreviations: GCL, dentate granule cell layer; SGZ, subgranular zone; H, hilus.

Fig. 4. Distribution of p(Ser9)GSK-3β immunofluorescence in adult DG of control and PAE mice.

Confocal images through DG of dorsal hippocampus from Control (A) and PAE (B) mice. P(Ser9)GSK-3β immunofluorescence is depicted in green, whereas tdTomato fluorescence in adult-generated DGCs is depicted in red. Cell nuclei are depicted in blue (DAPI). Boxed areas in A and B are shown at higher magnification in A1 and B1, respectively. p(Ser9)GSK-3β immunofluorescence is primarily observed within scattered cells of the hilus, granule cell layer and within tdTomato− cells in the vicinity of the SGZ, but is not highly expressed in tdTomato+ adult-generated DGCs. The overall distribution of p(Ser9)GSK-3β expression appears unchanged by PAE. Abbreviations: GCL, dentate granule cell layer; SGZ, subgranular zone; H, hilus

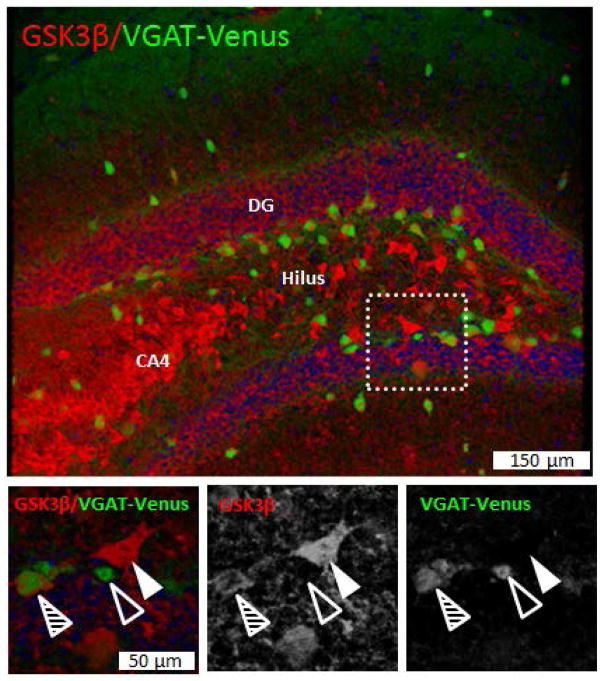

GSK3β is expressed in mossy cells and a subpopulation of hilar inhibitory interneurons

To begin to determine the phenotype of GSK-3β+ cells within the dentate hilar region of normal mice, we utilized (VGAT)-Venus transgenic mice that were not exposed to gestational alcohol. These mice express a green fluorescent variant (Venus) reporter gene under transcriptional control of the endogenous mouse vesicular GABA transporter (VGAT) promoter, resulting in genetic fluorescence labeling of inhibitory interneurons. As shown in Figure 5, GSK-3β immunofluorescence intensely labeled many large neurons that were negative for Venus reporter expression. These cells are most likely glutamatergic hilar mossy cells. However, we also observed many GSK-3β+/Venus+ co-labeled interneurons as well as many neurons that were GSK-3β−/Venus+ within the hilus and adjacent dentate granule cell layer. These results suggest that GSK-3β is expressed in both hilar mossy cells and a subset of dentate GABAergic interneurons. It is important to note that these reporter mice were not exposed to alcohol, so it is not known whether PAE might alter the pattern of Venus reporter expression.

Fig. 5. GSK-3β is expressed within mossy cells a subset of DG hilar interneurons.

Confocal image through DG of dorsal hippocampus from adult naïve VGAT-Venus mouse. GSK-3β immunofluorescence is depicted in red, whereas GABAergic inhibitory interneurons are depicted by green (Venus reporter expression under transcriptional control of endogenous vesicular GABA transporter (VGAT) promotor sequences). Higher power images of boxed area are depicted in lower panels. Note that intense GSK-3β immunofluorescence is observed within CA4 pyramidal neurons (CA4, upper panel), and in scattered cells throughout all regions of the dentate gyrus. Lower panels demonstrate GSK-3β expression in mossy cell interneurons (large Venus− neurons indicated by filled arrowheads) and within a subset of Venus+ GABAergic interneurons within the hilus (hatched arrowheads). Not all Venus+ GABAergic interneurons express GSK3β (open arrowhead depicts Venus+/GSK3β− interneuron). Less intense, but detectable, GSK-3β immunoreactivity is also observed in granule neurons throughout the dentate granule cell layer (DG).

DISCUSSION

GSK-3β is a multifunctional kinase implicated in the regulation of many CNS processes, including adult hippocampal neurogenesis (Pardo et al., 2016) and synaptic plasticity (Bradley et al., 2012). Abnormal GSK-3β signaling has been implicated in many neurological disorders, making it an attractive therapeutic target (Beurel et al., 2015). In the present study, we asked whether GSK-3β may play role in FASD, using a well-characterized mouse model of PAE previously shown to display long-term impairments in hippocampal-dependent learning, plasticity and EE-induced adult neurogenesis (Brady et al., 2012, Brady et al., 2013, Kajimoto et al., 2013, Kajimoto et al., 2016, Roitbak et al., 2011). Our results suggest suppression of GSK-3β signaling in PAE mice under EE conditions, as indicated by an approximate 63% increase in the ratio of p(Ser9)GSK-3β (inactive form)/total GSK-3β in hippocampal dentate of PAE mice compared to controls. Although we did not directly measure GSK-3β catalytic activity in this study, it is likely substantially suppressed since GSK-3β is a constitutively active kinase predominantly regulated via inactivation through phosphorylation at Ser9 (Doble and Woodgett, 2003). These findings corroborate prior observations of elevated p(Ser9)GSK-3β in whole hippocampus of adolescent PAE mice exposed to an identical gestational drinking paradigm, but without EE (Goggin et al., 2014). Taken together, these studies demonstrate that exposure to even moderate levels of alcohol during gestation leads to long-term elevation of p(Ser9)GSK-3β through young adulthood.

Our prior findings of impaired EE-mediated neurogenesis in the hippocampal dentate of adult PAE mice (Choi et al., 2005, Kajimoto et al., 2013, Kajimoto et al., 2016), coupled with evidence in the literature that GSK-3β regulates adult hippocampal neurogenesis (Morales-Garcia et al., 2012, Fuster-Matanzo et al., 2013, Jurado-Arjona et al., 2016, Llorens-Martin et al., 2016, Sirerol-Piquer et al., 2011), provided impetus for the current study. As mentioned previously, we have demonstrated impaired hippocampal neurogenesis in PAE mice resulting in approximately 50% fewer adult-generated DGCs compared to control mice under conditions of EE. Although many studies implicate GSK-3β in the regulation of adult hippocampal neurogenesis, the nature of this regulation remains ambiguous. For example, pan-neuronal overexpression of GSK-3β to induce excessive activation of GSK-3β throughout neurons of the adult hippocampus and cortex using CamKIIα-tTA/Tet-GSK-3β dual transgenic mice was found to impair normal adult hippocampal neurogenesis (Fuster-Matanzo et al., 2013, Llorens-Martin et al., 2016, Sirerol-Piquer et al., 2011). Conversely, GSK-3β overexpression in astrocytes and neural stem cells throughout development using GFAP-tTA/Tet-GSK-3β dual transgenic mice was found to promote neurogenesis by expanding the hippocampal progenitor pool (Jurado-Arjona et al., 2016). Another report indicated that GSK-3β inhibition using stereotactic lentiviral delivery of GSK-3β shRNA in which GSK-3β knockdown was restricted to the dentate gyrus had no effect on the number of adult-generated DGCs (Chew et al., 2015). Studies performed under more physiological conditions have linked neurogenesis stimulated by voluntary exercise or enriched environment to either enhanced or diminished GSK-3β activity, respectively (Hu et al., 2013, Zang et al., 2017). Finally. previous work in a mouse model of fragile X syndrome demonstrated that impaired hippocampal neurogenesis was associated with a marked decrease in the ratio of p(Ser9)GSK-3β/GSK-3β, and that neurogenesis could be rescued using a specific pharmacological inhibitor of GSK-3β (Guo et al., 2012). Although we did not evaluate the effects of EE per se on GSK-3β activity in this study, prior work has demonstrated an increased p(Ser9)GSK-3β/total GSK-3β ratio within hippocampus from healthy mice (Hu et al., 2013). Thus, we might have anticipated gestational alcohol to block this increase. However, our findings of increased ratio of p(Ser9)GSK-3β/GSK-3β in adult PAE-EE mice compared to control-EE mice suggest an exacerbated p(Ser9)GSK-3β response to EE following gestational alcohol exposure, which could represent a compensatory mechanisms triggered by an impaired neurogenic response. Future studies will be required to determine whether GSK-3β activity is reduced in PAE mice and if so, how this might be mechanistically linked to neurogenesis under standard vs. enriched housing conditions.

If enhanced Ser9 phosphorylation of GSK-3β is involved in the suppression of the neurogenic response to EE in PAE mice, we might anticipate this to be an indirect effect, based on our observation that GSK-3β expression within tdTomato+ hippocampal precursors and adult-generated DGCs appears weak compared that in hilar interneurons, mossy cells and CA pyramidal neurons. This cellular distribution is consistent with previous work demonstrating intense expression in hippocampal CA pyramidal neurons, neuronal cell bodies within the hilar region of the dentate gyrus and within processes throughout the stratum radiatum and lacunosum-moleculare, with much fainter expression within the dentate granule neurons (Perez-Costas et al., 2010). Our study extends that work to demonstrate GSK-3β expression in a subpopulation of GABAergic interneurons within the hilus and dentate granule cell layer and within hilar mossy cells. Both GABAergic interneurons and glutamatergic hilar mossy cells play important roles in the maturation and functional integration of adult-generated DGCs. GABA signaling has a depolarizing influence on immature DGCs in the early stages of neurogenesis, which is required for further maturation and integration of adult-born DGCs into the hippocampal network. Specifically, parvalbumin GABAergic interneurons have been shown to be critical for adult neurogenesis (Song et al., 2013) and may be important for priming newborn DGCs for subsequent activity-dependent integration via a disynaptic circuit involving more mature DGCs in response to hippocampal activation by EE (Alvarez et al., 2016). GABA depolarization is also required for experience-dependent synapse unsilencing of glutamatergic transmission in adult-born immature DGCs (Chancey et al., 2013). Indeed, hilar mossy cells provide the first direct glutamatergic synapses, as well as disynaptic GABAergic input to adult-born DGCs, and have been implicated in regulating activity-dependent neurogenesis (Chancey et al., 2014). Clearly, any potential impact of GSK-3β signaling on adult neurogenesis must be considered in the context of a broader hippocampal network regulation (Sailor et al., 2017).

GSK-3β is constitutively active in resting neurons (Hur and Zhou, 2010), and the primary mechanisms for regulating its enzyme activity is via phosphorylation at Ser9, resulting in the suppression of kinase activity (Doble and Woodgett, 2003). Many upstream signaling pathways inactivate GSK-3β by phosphorylating Ser9 in neurons. These include pathways that activate Akt, CaMKII, PKC, PKA, PrkG1, RSK and ILK (reviewed by (Bradley et al., 2012)). Similarly GSK-3β is a pleiotropic kinase with many downstream targets, including glycogen synthase, MAP1B, Tau, presenilin, CREB and β-catenin (Bradley et al., 2012, Peineau et al., 2008). GSK-3β plays a prominent role in hippocampal synaptic plasticity. Knockdown of GSK-3β expression in the adult dentate granule cell layer by lentiviral delivery of GSK-3β shRNA results in severe impairment of contextual fear discrimination and impaired synaptic plasticity in this region (Chew et al., 2015). This is consistent with other studies demonstrating impairment of hippocampal-dependent memory in heterozygous GSK-3β knockout mice (Kimura et al., 2008) where GSK-3β activity is reduced. GSK-3β activity is known to potently regulate LTP/LTD balance, as well as AMPA and GABA receptor subunit trafficking in adult CNS (Bradley et al., 2012).

Although excessive GSK-3β activity has been implicated as a causal factor in many neurological disorders, the current study suggests that the hippocampal deficits in PAE mice may be related to excessive suppression of GSK-3β through enhanced Ser9 phosphorylation. Future studies to demonstrate this will require direct measurement of GSK-3β enzymatic activity and downstream signaling. Given that GSK-3β regulates many aspects of neuronal plasticity, it will be important to investigate the functional implications of elevated p(Ser9)GSK-3β as a causal factor underlying the long-term impairments in hippocampal neurogenesis, particularly in the broader context of hippocampal network function.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by the NIH-NIAAAA [P50-AA022534]

Images in this paper were generated in the University of New Mexico & Cancer Center Fluorescence Microscopy Shared Resource, funded as detailed on: http://hsc.unm.edu/crtc/microscopy/acknowledgement.shtml

References

- ALVAREZ DD, GIACOMINI D, YANG SM, TRINCHERO MF, TEMPRANA SG, BUTTNER KA, BELTRAMONE N, SCHINDER AF. A disynaptic feedback network activated by experience promotes the integration of new granule cells. Science. 2016;354:459–465. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf2156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AUTTI-RAMO I, AUTTI T, KORKMAN M, KETTUNEN S, SALONEN O, VALANNE L. MRI findings in children with school problems who had been exposed prenatally to alcohol. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2002;44:98–106. doi: 10.1017/s0012162201001748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BERMAN RF, HANNIGAN JH. Effects of prenatal alcohol exposure on the hippocampus: spatial behavior, electrophysiology, and neuroanatomy. Hippocampus. 2000;10:94–110. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(2000)10:1<94::AID-HIPO11>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BEUREL E, GRIECO SF, JOPE RS. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK3): regulation, actions, and diseases. Pharmacology & therapeutics. 2015;148:114–31. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2014.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOEHME F, GIL-MOHAPEL J, COX A, PATTEN A, GILES E, BROCARDO PS, CHRISTIE BR. Voluntary exercise induces adult hippocampal neurogenesis and BDNF expression in a rodent model of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. The European journal of neuroscience. 2011;33:1799–811. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2011.07676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRADLEY CA, PEINEAU S, TAGHIBIGLOU C, NICOLAS CS, WHITCOMB DJ, BORTOLOTTO ZA, KAANG BK, CHO K, WANG YT, COLLINGRIDGE GL. A pivotal role of GSK-3 in synaptic plasticity. Frontiers in molecular neuroscience. 2012;5:13. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2012.00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRADY ML, ALLAN AM, CALDWELL KK. A limited access mouse model of prenatal alcohol exposure that produces long-lasting deficits in hippocampal-dependent learning and memory. Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research. 2012;36:457–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01644.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRADY ML, DIAZ MR, IUSO A, EVERETT JC, VALENZUELA CF, CALDWELL KK. Moderate prenatal alcohol exposure reduces plasticity and alters NMDA receptor subunit composition in the dentate gyrus. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2013;33:1062–7. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1217-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CAMERON HA, GLOVER LR. Adult neurogenesis: beyond learning and memory. Annu Rev Psychol. 2015;66:53–81. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010814-015006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHANCEY JH, ADLAF EW, SAPP MC, PUGH PC, WADICHE JI, OVERSTREET-WADICHE LS. GABA depolarization is required for experience-dependent synapse unsilencing in adult-born neurons. J Neurosci. 2013;33:6614–22. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0781-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHANCEY JH, POULSEN DJ, WADICHE JI, OVERSTREET-WADICHE L. Hilar mossy cells provide the first glutamatergic synapses to adult-born dentate granule cells. J Neurosci. 2014;34:2349–54. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3620-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHAO J, YANG L, YAO H, BUCH S. Platelet-derived growth factor-BB restores HIV Tat -mediated impairment of neurogenesis: role of GSK-3beta/beta-catenin. Journal of neuroimmune pharmacology : the official journal of the Society on NeuroImmune Pharmacology. 2014;9:259–68. doi: 10.1007/s11481-013-9509-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHEW B, RYU JR, NG T, MA D, DASGUPTA A, NEO SH, ZHAO J, ZHONG Z, BICHLER Z, SAJIKUMAR S, GOH EL. Lentiviral silencing of GSK-3beta in adult dentate gyrus impairs contextual fear memory and synaptic plasticity. Frontiers in behavioral neuroscience. 2015;9:158. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2015.00158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHOI IY, ALLAN AM, CUNNINGHAM LA. Moderate fetal alcohol exposure impairs the neurogenic response to an enriched environment in adult mice. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29:2053–62. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000187037.02670.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DIAZ MR, JOTTY K, LOCKE JL, JONES SR, VALENZUELA CF. Moderate Alcohol Exposure during the Rat Equivalent to the Third Trimester of Human Pregnancy Alters Regulation of GABAA Receptor-Mediated Synaptic Transmission by Dopamine in the Basolateral Amygdala. Frontiers in pediatrics. 2014;2:46. doi: 10.3389/fped.2014.00046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DOBLE BW, WOODGETT JR. GSK-3: tricks of the trade for a multi-tasking kinase. Journal of cell science. 2003;116:1175–86. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FONTAINE CJ, PATTEN AR, SICKMANN HM, HELFER JL, CHRISTIE BR. Effects of pre-natal alcohol exposure on hippocampal synaptic plasticity: Sex, age and methodological considerations. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews. 2016;64:12–34. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FUSTER-MATANZO A, LLORENS-MARTIN M, SIREROL-PIQUER MS, GARCIA-VERDUGO JM, AVILA J, HERNANDEZ F. Dual effects of increased glycogen synthase kinase-3beta activity on adult neurogenesis. Human molecular genetics. 2013;22:1300–15. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GIL-MOHAPEL J, BOEHME F, KAINER L, CHRISTIE BR. Hippocampal cell loss and neurogenesis after fetal alcohol exposure: insights from different rodent models. Brain research reviews. 2010;64:283–303. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2010.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GOGGIN SL, CALDWELL KK, CUNNINGHAM LA, ALLAN AM. Prenatal alcohol exposure alters p35, CDK5 and GSK3beta in the medial frontal cortex and hippocampus of adolescent mice. Toxicology reports. 2014;1:544–553. doi: 10.1016/j.toxrep.2014.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GU Y, ARRUDA-CARVALHO M, WANG J, JANOSCHKA SR, JOSSELYN SA, FRANKLAND PW, GE S. Optical controlling reveals time-dependent roles for adult-born dentate granule cells. Nature neuroscience. 2012;15:1700–6. doi: 10.1038/nn.3260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GUERRI C, BAZINET A, RILEY EP. Foetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders and alterations in brain and behaviour. Alcohol and alcoholism. 2009;44:108–14. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agn105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GUO W, MURTHY AC, ZHANG L, JOHNSON EB, SCHALLER EG, ALLAN AM, ZHAO X. Inhibition of GSK3beta improves hippocampus-dependent learning and rescues neurogenesis in a mouse model of fragile X syndrome. Human molecular genetics. 2012;21:681–91. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAGIHARA H, TOYAMA K, YAMASAKI N, MIYAKAWA T. Dissection of hippocampal dentate gyrus from adult mouse. Journal of visualized experiments : JoVE. 2009 doi: 10.3791/1543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HU YS, LONG N, PIGINO G, BRADY ST, LAZAROV O. Molecular mechanisms of environmental enrichment: impairments in Akt/GSK3beta, neurotrophin-3 and CREB signaling. PloS one. 2013;8:e64460. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUI J, ZHANG J, KIM H, TONG C, YING Q, LI Z, MAO X, SHI G, YAN J, ZHANG Z, XI G. Fluoxetine regulates neurogenesis in vitro through modulation of GSK-3beta/beta-catenin signaling. The international journal of neuropsychopharmacology. 2014:18. doi: 10.1093/ijnp/pyu099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUR EM, ZHOU FQ. GSK3 signalling in neural development. Nature reviews. Neuroscience. 2010;11:539–51. doi: 10.1038/nrn2870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IERACI A, HERRERA DG. Single alcohol exposure in early life damages hippocampal stem/progenitor cells and reduces adult neurogenesis. Neurobiology of disease. 2007;26:597–605. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2007.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JURADO-ARJONA J, LLORENS-MARTIN M, AVILA J, HERNANDEZ F. GSK3beta Overexpression in Dentate Gyrus Neural Precursor Cells Expands the Progenitor Pool and Enhances Memory Skills. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2016;291:8199–213. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.674531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAIDANOVICH-BEILIN O, WOODGETT JR. GSK-3: Functional Insights from Cell Biology and Animal Models. Frontiers in molecular neuroscience. 2011;4:40. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2011.00040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAJIMOTO K, ALLAN A, CUNNINGHAM LA. Fate analysis of adult hippocampal progenitors in a murine model of fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD) PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e73788. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAJIMOTO K, VALENZUELA CF, ALLAN AM, GE S, GU Y, CUNNINGHAM LA. Prenatal alcohol exposure alters synaptic activity of adult hippocampal dentate granule cells under conditions of enriched environment. Hippocampus. 2016;26:1078–87. doi: 10.1002/hipo.22588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KIM WY, WANG X, WU Y, DOBLE BW, PATEL S, WOODGETT JR, SNIDER WD. GSK-3 is a master regulator of neural progenitor homeostasis. Nature neuroscience. 2009;12:1390–7. doi: 10.1038/nn.2408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KIMURA T, YAMASHITA S, NAKAO S, PARK JM, MURAYAMA M, MIZOROKI T, YOSHIIKE Y, SAHARA N, TAKASHIMA A. GSK-3beta is required for memory reconsolidation in adult brain. PloS one. 2008;3:e3540. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KLINTSOVA AY, HELFER JL, CALIZO LH, DONG WK, GOODLETT CR, GREENOUGH WT. Persistent impairment of hippocampal neurogenesis in young adult rats following early postnatal alcohol exposure. Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research. 2007;31:2073–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00528.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KRAWCZYK M, RAMANI M, DIAN J, FLOREZ CM, MYLVAGANAM S, BRIEN J, REYNOLDS J, KAPUR B, ZOIDL G, POULTER MO, CARLEN PL. Hippocampal hyperexcitability in fetal alcohol spectrum disorder: Pathological sharp waves and excitatory/inhibitory synaptic imbalance. Experimental neurology. 2016;280:70–9. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2016.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAGACE DC, WHITMAN MC, NOONAN MA, ABLES JL, DECAROLIS NA, ARGUELLO AA, DONOVAN MH, FISCHER SJ, FARNBAUCH LA, BEECH RD, DILEONE RJ, GREER CA, MANDYAM CD, EISCH AJ. Dynamic contribution of nestin-expressing stem cells to adult neurogenesis. J Neurosci. 2007;27:12623–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3812-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LI L, HARMS KM, VENTURA PB, LAGACE DC, EISCH AJ, CUNNINGHAM LA. Focal cerebral ischemia induces a multilineage cytogenic response from adult subventricular zone that is predominantly gliogenic. Glia. 2010;58:1610–9. doi: 10.1002/glia.21033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LLORENS-MARTIN M, TEIXEIRA CM, JURADO-ARJONA J, RAKWAL R, SHIBATO J, SOYA H, AVILA J. Retroviral induction of GSK-3beta expression blocks the stimulatory action of physical exercise on the maturation of newborn neurons. Cellular and molecular life sciences : CMLS. 2016;73:3569–82. doi: 10.1007/s00018-016-2181-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MADISEN L, ZWINGMAN TA, SUNKIN SM, OH SW, ZARIWALA HA, GU H, NG LL, PALMITER RD, HAWRYLYCZ MJ, JONES AR, LEIN ES, ZENG H. A robust and high-throughput Cre reporting and characterization system for the whole mouse brain. Nature neuroscience. 2010;13:133–40. doi: 10.1038/nn.2467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MIRLASHARI MR, RANDEN I, KJELDSEN-KRAGH J. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK-3) inhibition induces apoptosis in leukemic cells through mitochondria-dependent pathway. Leukemia research. 2012;36:499–508. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2011.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MORALES-GARCIA JA, LUNA-MEDINA R, ALONSO-GIL S, SANZ-SANCRISTOBAL M, PALOMO V, GIL C, SANTOS A, MARTINEZ A, PEREZ-CASTILLO A. Glycogen synthase kinase 3 inhibition promotes adult hippocampal neurogenesis in vitro and in vivo. ACS chemical neuroscience. 2012;3:963–71. doi: 10.1021/cn300110c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NAKASHIBA T, CUSHMAN JD, PELKEY KA, RENAUDINEAU S, BUHL DL, MCHUGH TJ, RODRIGUEZ BARRERA V, CHITTAJALLU R, IWAMOTO KS, MCBAIN CJ, FANSELOW MS, TONEGAWA S. Young dentate granule cells mediate pattern separation, whereas old granule cells facilitate pattern completion. Cell. 2012;149:188–201. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PARDO M, ABRIAL E, JOPE RS, BEUREL E. GSK3beta isoform-selective regulation of depression, memory and hippocampal cell proliferation. Genes, brain, and behavior. 2016;15:348–55. doi: 10.1111/gbb.12283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PEINEAU S, BRADLEY C, TAGHIBIGLOU C, DOHERTY A, BORTOLOTTO ZA, WANG YT, COLLINGRIDGE GL. The role of GSK-3 in synaptic plasticity. British journal of pharmacology. 2008;153(Suppl 1):S428–37. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PEREZ-COSTAS E, GANDY JC, MELENDEZ-FERRO M, ROBERTS RC, BIJUR GN. Light and electron microscopy study of glycogen synthase kinase-3beta in the mouse brain. PloS one. 2010;5:e8911. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PIATTI VC, EWELL LA, LEUTGEB JK. Neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus: carrying the message or dictating the tone. Frontiers in neuroscience. 2013;7:50. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2013.00050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REDILA VA, OLSON AK, SWANN SE, MOHADES G, WEBBER AJ, WEINBERG J, CHRISTIE BR. Hippocampal cell proliferation is reduced following prenatal ethanol exposure but can be rescued with voluntary exercise. Hippocampus. 2006;16:305–11. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RIIKONEN R, SALONEN I, PARTANEN K, VERHO S. Brain perfusion SPECT and MRI in foetal alcohol syndrome. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology. 1999;41:652–659. doi: 10.1017/s0012162299001358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROITBAK T, THOMAS K, MARTIN A, ALLAN A, CUNNINGHAM LA. Moderate fetal alcohol exposure impairs neurogenic capacity of murine neural stem cells isolated from the adult subventricular zone. Experimental neurology. 2011;229:522–5. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2011.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAILOR KA, SCHINDER AF, LLEDO PM. Adult neurogenesis beyond the niche: its potential for driving brain plasticity. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2017;42:111–117. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2016.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SIREROL-PIQUER M, GOMEZ-RAMOS P, HERNANDEZ F, PEREZ M, MORAN MA, FUSTER-MATANZO A, LUCAS JJ, AVILA J, GARCIA-VERDUGO JM. GSK3beta overexpression induces neuronal death and a depletion of the neurogenic niches in the dentate gyrus. Hippocampus. 2011;21:910–22. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SONG J, SUN J, MOSS J, WEN Z, SUN GJ, HSU D, ZHONG C, DAVOUDI H, CHRISTIAN KM, TONI N, MING GL, SONG H. Parvalbumin interneurons mediate neuronal circuitry-neurogenesis coupling in the adult hippocampus. Nature neuroscience. 2013;16:1728–30. doi: 10.1038/nn.3572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SOWELL ER, LU LH, O’HARE ED, MCCOURT ST, MATTSON SN, O’CONNOR MJ, BOOKHEIMER SY. Functional magnetic resonance imaging of verbal learning in children with heavy prenatal alcohol exposure. Neuroreport. 2007;18:635–9. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e3280bad8dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SPALDING KL, BERGMANN O, ALKASS K, BERNARD S, SALEHPOUR M, HUTTNER HB, BOSTROM E, WESTERLUND I, VIAL C, BUCHHOLZ BA, POSSNERT G, MASH DC, DRUID H, FRISEN J. Dynamics of hippocampal neurogenesis in adult humans. Cell. 2013;153:1219–27. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STREISSGUTH AP, O’MALLEY K. Neuropsychiatric implications and long-term consequences of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Seminars in clinical neuropsychiatry. 2000;5:177–90. doi: 10.1053/scnp.2000.6729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UBAN KA, SLIWOWSKA JH, LIEBLICH S, ELLIS LA, YU WK, WEINBERG J, GALEA LA. Prenatal alcohol exposure reduces the proportion of newly produced neurons and glia in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus in female rats. Hormones and behavior. 2010;58:835–43. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2010.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WANG Y, KAKIZAKI T, SAKAGAMI H, SAITO K, EBIHARA S, KATO M, HIRABAYASHI M, SAITO Y, FURUYA N, YANAGAWA Y. Fluorescent labeling of both GABAergic and glycinergic neurons in vesicular GABA transporter (VGAT)-venus transgenic mouse. Neuroscience. 2009;164:1031–43. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WILLOUGHBY KA, SHEARD ED, NASH K, ROVET J. Effects of prenatal alcohol exposure on hippocampal volume, verbal learning, and verbal and spatial recall in late childhood. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2008;14:1022–33. doi: 10.1017/S1355617708081368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZANG J, LIU Y, LI W, XIAO D, ZHANG Y, LUO Y, LIANG W, LIU F, WEI W. Voluntary exercise increases adult hippocampal neurogenesis by increasing GSK-3beta activity in mice. Neuroscience. 2017;354:122–135. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2017.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.