Abstract

Rationale

AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) is a heterotrimeric protein that plays an important role in energy homeostasis and cardioprotection. Two isoforms of each subunit are expressed in the heart but the isoform-specific function of AMPK remains unclear.

Objective

We sought to determine the role of γ2-AMPK in cardiac stress response using bioengineered cell lines and mouse models containing either isoform of the γ-subunit in the heart.

Methods and Results

We found that γ2 but not γ1 or γ3 subunit translocated into nucleus upon AMPK activation. Nuclear accumulation of AMPK complexes containing γ2-subunit phosphorylated and inactivated RNA Pol I-associated transcription factor TIF-IA at Ser-635, precluding the assembly of transcription initiation complexes for rDNA. The subsequent down-regulation of pre-rRNA level led to attenuated ER stress and cell death. Deleting γ2-AMPK led to increases in pre-rRNA level, ER stress markers and cell death during glucose deprivation, which could be rescued by inhibition of rRNA processing or ER stress. To study the function of γ2-AMPK in the heart, we generated a mouse model with cardiac specific deletion of γ2-AMPK (cKO). Although the total AMPK activity was unaltered in cKO hearts due to upregulation of γ1-AMPK, the lack of γ2-AMPK sensitizes the heart to myocardial ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury. The cKO failed to suppress pre-rRNA level during I/R, and showed a greater infarct size. Conversely, cardiac-specific overexpression of γ2-AMPK decreased ribosome biosynthesis and ER stress during I/R insult, and the infarct size was reduced.

Conclusions

The γ2-AMPK translocates into the nucleus to suppress pre-rRNA transcription and ribosome biosynthesis during stress, thus ameliorating ER stress and cell death. Increased γ2-AMPK activity is required to protect against I/R injury. Our study reveals an isoform-specific function of γ2-AMPK in modulating ribosome biosynthesis, cell survival and cardioprotection.

Keywords: γ2-AMPK, pre-rRNA, nuclear translocation, ER stress, cell death, ischemia/reperfusion injury

Subject Terms: Chronic Ischemic Heart Disease, Ischemia, Cell Biology/Structural Biology, Basic Science Research

INTRODUCTION

AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) is a crucial energy sensor and a master regulator of cell metabolism that has been implicated in a number of pathological conditions including cardiovascular diseases.1, 2 The AMPK is a heterotrimeric complex, containing one catalytic and two regulatory subunits. In mammalians, two or three isoforms of the catalytic (α1, α2) and the regulatory (β1, β2, γ1, γ2, and γ3) subunits have been identified, each encoded by a separate gene. Previous studies showed no preferential binding among the isoforms of the three subunits.3, 4 The composition of the AMPK complex is thus likely determined by cell-type specific expression profile and subcellular localization of the isoforms. The heterotrimeric composition is, however, biologically meaningful as recent studies show that these combinations determine the regulation of AMPK activity and function. For example, phosphorylation of acetyl-CoA carboxylase in skeletal muscle during exercise is mostly attributed to the selective activation of α2/β2/γ3.5 AMPK complex containing γ1-subunit is localized to Z-line while γ2-AMPK is involved in mitotic process.6–8 In the heart, all isoforms except γ3 are present resulting in 8 possible AMPK heterotrimers but the isoform-specific function is poorly understood. Although not a major isoform in the heart, human mutations in the γ2 subunit causes an unique form of cardiomyopathy again raising the issue of isoform-specific function of AMPK.9–11

It is known that activation of AMPK during stress exerts cardioprotective effects. Increased AMPK activity during ischemia functions to maintain energy homeostasis and promote cell survival12–15 while activation of AMPK during chronic stress improves the outcome of heart failure.16 The exciting observations in the laboratory, however, have not been successfully translated into therapy. Several gaps in our knowledge of AMPK are in the way. For example, most prior studies focused on the overall AMPK activity without addressing the role of the isoform composition of the AMPK complex. Chronic activation of γ2-AMPK in the absence of stress, due to point mutations of Prkag2 gene that encodes the γ2 subunit, causes metabolic cardiomyopathy and obesity.9–11, 17 It is not clear whether these effects are due to changes in the total AMPK activity or γ2-specific activity. Furthermore, AMPK substrates have been identified in the nucleus but the isoform-specificity of nuclear AMPK has been poorly understood.18, 19 To determine the isoform-specific role of the AMPK, here we created cellular and mouse models in which the total AMPK activity was kept unaltered but the complex contained only one isoform of the γ-subunit. Using these models, we showed that γ2-AMPK translocated to the nucleus during stress to suppress ribosomal RNA transcription. Such a response in the heart reduced ER stress and cell death during ischemia/reperfusion injury.

METHODS

Animals

Transgenic mice with cardiac-specific overexpression of wildtype γ2-AMPK were previously described.20 Mice with cardiac specific deletion of γ2-AMPK (cKO) were generated using the Cre/loxP system. The I/R injury was imposed by ligation of the left anterior descending coronary artery (LAD) with 7–0 suture threaded through a snare for 30 minutes followed by withdrawal of the snare for 24 hours.21 All animal experiments in this study were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the University of Washington.

Stable cell lines

We used both plasmid transfection and lentiviral infection methods to establish stable cell lines. For plasmid transfection, plasmids expressing full length EV, γ1 or γ2 were transfected into HEK293 cells using Lipofectamine-2000 (Invitrogen) and single colonies were picked and selected using hygromycin B. For lentiviral infection, CON or γ2 KO plasmid was co-transfected with helper plasmids into HEK293T cells and viral particles were collected to infect HEK293 cells.

Nucleoli staining and cell imaging

For nucleoli staining, 60,000 cells were seeded onto poly-L-lysine coated glass coverslip 24 hours prior to staining. Nucleoli were stained using CytoPainter Nucleolar Staining Kit (Abcam) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For cell imaging, cells were plated onto coverslips within a cell chamber (Thermo Fisher). Images were captured using Zeiss LSM 510 Meta Confocal Microscope.

Cell death measurement

10,000 cells were plated onto 96-well plate 24h prior to treatment. Cell death was measured using CellTox™ Green Cytotoxicity Assay (Promega).

RNA extraction and qRT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from tissue or cells using a QIAGEN RNeasy Kit and was converted to cDNA using iScript Reverse Transcription Supermix (Bio-Rad). qRT-PCR was performed using SYBR Green Supermix on the 7500 fast real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems). Gene expression was normalized to β-actin. Primers used in this study are listed in Online Table I.

Statistical analysis

All data were presented as mean ± SD. Student’s T-test was used for comparisons of two groups and two-way ANOVA was used for multiple comparisons. P<0.05 was considered significant.

See Online Supplement for additional details.

RESULTS

The γ2-subunit translocated to nucleus under stress condition

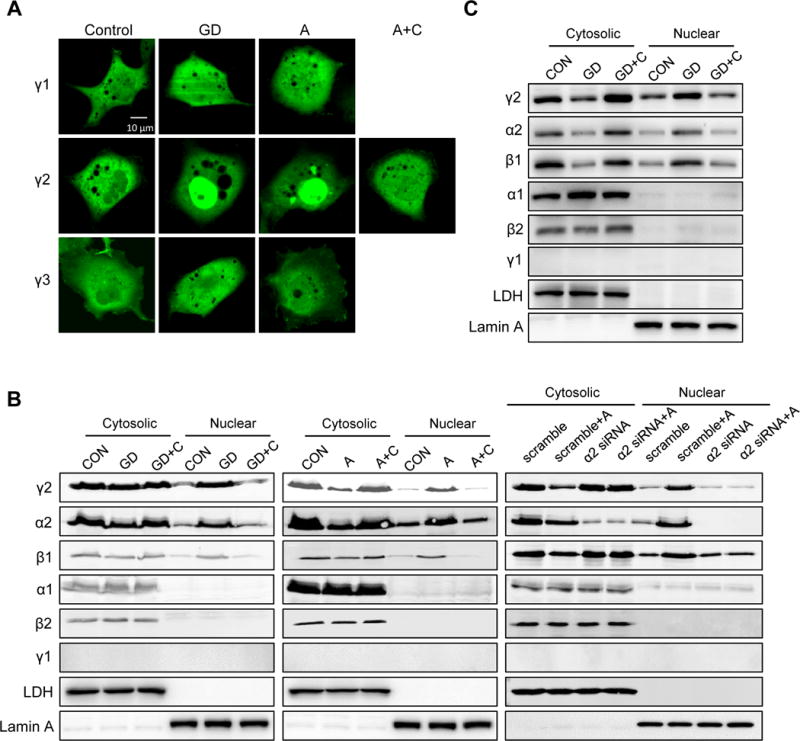

To investigate the isoform-specific role of the AMPK γ subunit in cellular stress response, we transfected COS7 cells with GFP tagged γ1, γ2 or γ3 subunit. The three γ subunit isoforms showed uniform distribution in the cell under normal condition (Figure 1A). Upon glucose deprivation (GD) or treatment with A769662, an AMPK activator, GFP-γ2 subunit but not GFP-γ1 or -γ3 accumulated in the nucleus (Figure 1A). The accumulation was reversed by the treatment of compound C, an inhibitor of AMPK (Figure 1A). These results suggested that activation of AMPK under these conditions selectively translocated the γ2-subunit into nucleus. Subsequent primary amino acid sequence analysis identified nuclear localization sequence (NLS) and nuclear export sequence (NES) in γ2 and γ3 subunits (Online Figure I). We thus generated GFP-tagged-γ2 subunit lacking either NLS or NES and expressed them in COS7 cells. Deletion of NLS resulted in cytosolic distribution and deletion of NES caused nuclear accumulation of γ2 subunit, suggesting that NLS and NES are required for shuttling the subunit between nucleus and cytosol (Online Figure II). To rule out the potential artifacts of transient transfection, we established stable lines with γ1 and γ2 overexpression (OE) in HEK293 cells (Online Figure III). Treatment of γ2 OE cells with GD or A769662 induced accumulation of γ2-subunit in the nuclear fraction, along with α2- and β1-subunit (Figure 1B, left and middle panel). The accumulation was abrogated by addition of compound C or knockdown of α2 subunit, suggesting that activation of AMPK under these conditions led to the formation of α2β1γ2 complex in the nucleus (Figure 1B, right panel). Similar treatment of γ1 OE cells did not result in nuclear accumulation of γ1-subunit (data not shown). To test if nuclear accumulation of γ2-subunit under stress condition could also be observed in cardiomyocytes, we over-expressed γ2-AMPK in neonatal rat ventricular myocytes (NRVM) using adenovirus (Online Figure IVA). As expected, GD stimulated nuclear accumulation of AMPK complexes containing γ2-subunit and compound C abrogated this effect (Figure 1C).

Figure 1. γ2-AMPK translocates into nucleus under stress condition.

A, COS7 cells transfected with GFP-tagged γ1, γ2 or γ3 subunit were subjected to glucose deprivation (GD; 2h), A769662 supplementation (A; 0.3 mmol/L; 2h) or A769662 plus Compound C (A+C; Compound C 40 μmol/L; 2h). Scale bar, 10 μm. B, HEK293 cells stably expressing γ2-AMPK or further transfected with α2-AMPK siRNA (α2 siRNA) were subjected to GD, GD+C, A or A+C. Cytosolic and nuclear fractions were isolated to measure protein level of AMPK subunits. LDH and Lamin A serve as loading control for cytosolic and nuclear fraction, respectively. C, NRVM stably expressing γ2-AMPK were subjected to GD or GD+C. Cytosolic and nuclear fractions were isolated to measure protein level of AMPK subunits. LDH and Lamin A serve as loading control for cytosolic and nuclear fraction, respectively.

Nuclear translocation of γ2-AMPK led to downregulation of pre-rRNA level

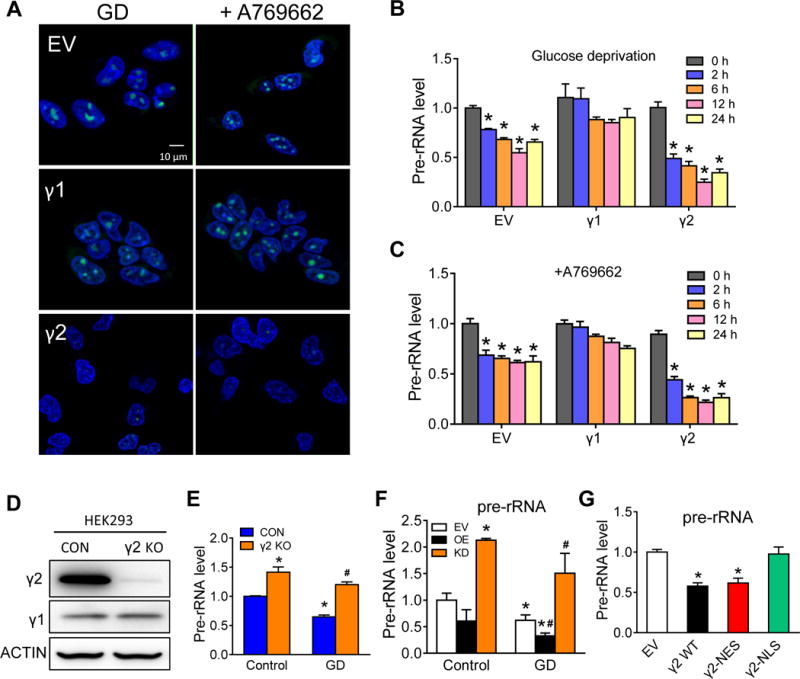

In γ2 but not γ1 OE cells subjected to glucose starvation or A769662 treatment we found a significant decrease of nucleoli staining (Figure 2A), suggesting a reduction of rRNA under these conditions. Since the initial step of rRNA synthesis involves the transcription of rDNA to pre-rRNA, we then measured pre-rRNA levels in these cells. As expected, γ2 OE cells showed a greater decrease of pre-rRNA level during glucose deprivation (GD, Figure 2B). This effect was also observed upon activation of AMPK by A769662 (Figure 2C). To determine the isoform specificity of our observation, we deleted γ2-subunit in HEK293 cells using CRISPR-Cas9 system (Figure 2D). Deletion of γ2 (γ2 KO), although did not affect the γ1 level, increased pre-rRNA level and abolished the downregulation of pre-rRNA during glucose deprivation (Figure 2E). Similarly, γ2 overexpression suppressed whereas γ2 knockdown enhanced pre-rRNA level upon GD in NRVM (Figure 2F; Online Figure IVA and IVB). To test whether the nuclear translocation of γ2-AMPK is essential for pre-rRNA inhibition, we over-expressed wildtype γ2 with or without NLS into HEK293 cells. Under glucose deprivation condition, γ2 with NLS (γ2 WT) suppressed pre-rRNA level while γ2 lacking NLS (γ2-NLS) did not (Figure 2F). These effects are dependent on AMPK activity as knockdown of the α2-catalytic subunit abolished the downregulation of pre-rRNA during GD (Online Figure IVC and IVD). This is also consistent with the observation that activation of α2-AMPK led to nuclear accumulation of AMPK (Figure 1B).22, 23 These data collectively indicate that the inhibition of rRNA synthesis during stress is attributable to the formation of AMPK complex containing γ2-AMPK in the nucleus.

Figure 2. γ2-AMPK downregulates pre-rRNA.

A, Live cell nucleoli staining of COS7 cells expressing empty vector (EV), γ1 or γ2 with confocal microscope. Cells were treated with GD or A769662 for 2h. Nucleoli (green) were stained with cytopainter nucleolar staining kit and nuclei (blue) were stained with Hoechst 33342. Scale bar, 10 μm. B,C, HEK293 cells stably expressing EV, γ1 or γ2 were subjected to glucose deprivation (B) or A769662 treatment (C). RNA samples were harvested 0, 2, 6, 12 and 24h after treatment and pre-rRNA levels were determined by qRT-PCR analysis. *P<0.05 vs. 0h in each group, n=4. D, Western blot shows knockout of γ2-AMPK (γ2 KO) in HEK293 cells using RNA-guided CRISPR Cas9 system, n=5. E, Relative pre-rRNA level in control (CON) and γ2 KO HEK293 cells under control and GD condition (24h). *P<0.05 vs. CON/Control, #P<0.05 vs. CON/GD, n=4. F, Relative pre-rRNA level in NRVM expressing EV, γ2 overexpression (OE) or γ2 knockdown (KD) under control and GD condition (24h). *P<0.05 vs. EV/Control, #P<0.05 vs. EV/GD, n=4. G, Relative pre-rRNA level in HEK293 cells transfected with EV, γ2 (γ2 WT), γ2 lacking nuclear export sequence (γ2-NES) or lacking nuclear localization sequence (γ2-NLS) under GD condition (24h). *P<0.05 vs. EV, n=4.

Activation of γ2-AMPK inhibited the Pol I transcription complex

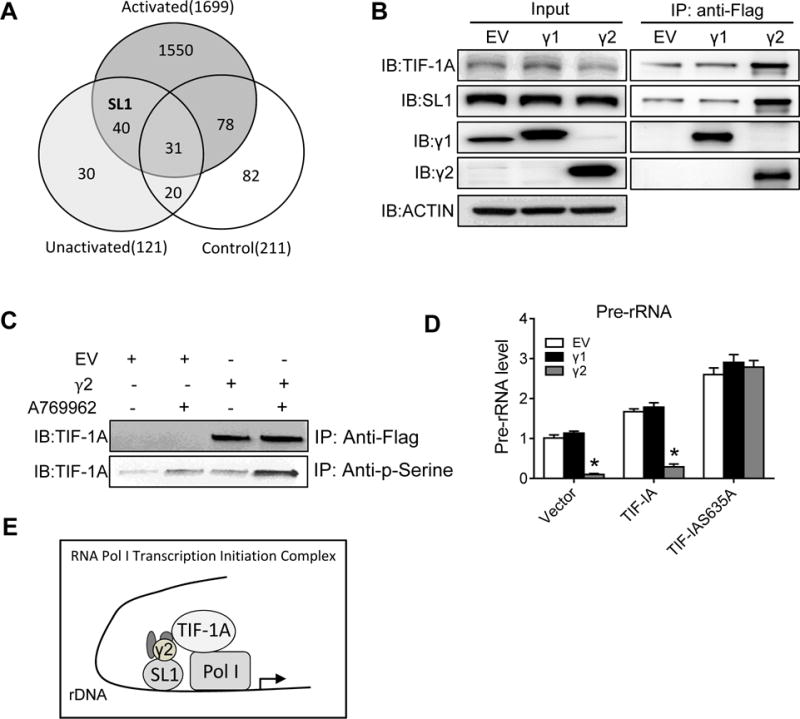

To understand the mechanism(s) underlying the suppression of pre-rRNA level by γ2-AMPK, we performed pull-down experiments with anti-Flag antibody in protein extracts of HEK293 cells stably expressing Flag tag (Control) or Flag-γ2 (γ2 OE). Mass-spectrometry analysis identified more than 1600 proteins in the pull-down of γ2 OE cells that do not present in the control cells (Figure 3A; Online Table II). Among the 40 proteins that were present under both baseline and AMPK activated conditions we identified selectivity factor 1 (SL1), a transcription factor that bound to RNA Pol I to initiate the transcription of rDNA. Further immunoprecipitation (IP) assay showed that SL1 and TIF-IA, another Pol I-associated transcription factor, were among proteins immunoprecipitated with γ2- but not γ1-AMPK (Figure 3B). Furthermore, phosphorylated TIF-1A in the γ2-pulldown increased significantly after AMPK activation (Figure 3C). TIF-IA was reported to be phosphorylated by AMPK at serine 635, a residue conserved within its C-terminal domain, causing its inactivation and release of the Pol I from the transcription initiation complex.19 Our findings thus suggested that γ2-AMPK was the isoform involved in the regulation of RNA Pol I transcription initiation complex assembly. To test whether the inhibition of pre-rRNA was due to TIF-IA phosphorylation at S635, we transfected γ1- or γ2-overexpressed cells with wildtype or mutant TIF-1A that was resistant to phosphorylation (TIF-IAS635A), and subjected these cells to glucose deprivation. TIF-IAS635A abrogated the inhibition of pre-rRNA by γ2 overexpression (Figure 3D), suggesting that γ2-AMPK suppresses pre-rRNA synthesis under stress condition by phosphorylating TIF-IA at Ser-635. These results collectively suggest that γ2-AMPK interacts with the rDNA transcription complex and once activated disassemble the complex through phosphorylation of TIF-1A (Figure 3E).

Figure 3. γ2-AMPK interaction with TIF-IA suppresses ribosome biogenesis.

A, Venn diagram of mass-spectrometry analysis. Protein extracts of HEK293 cells stably expressing Flag-EV (Control) or Flag-γ2 under either normal (Unactivated) or A769662 treatment (Activated) condition were immunoprecipitated with anti-Flag antibody and immunoprecipitates were subjected to mass-spectrometry. Protein numbers were shown in each circle. B, Immunoprecipitation (IP) assay. Total cell lysates from HEK293 cells stably expressing Flag-tagged EV, γ1 or γ2 were subjected to IP with Flag antibody. Western blot analysis of immunoprecipitates with γ1, γ2, SL1 and TIF-IA antibodies. Input shows protein abundance in total extracts. ACTIN serves as loading control. C, IP assay. HEK293 cells with Flag-tagged EV or γ2 were treated with or without A769662. Protein extracts were immunoprecipitated with Flag or p-Serine antibody and western blot analysis was then performed with TIF-IA antibody. D, HEK293 cells stably expressing EV, γ1 or γ2 were transfected with empty vector (Vector), wildtype TIF-IA (TIF-IA) or mutant (TIF-IAS635A) accompanied by glucose deprivation. Pre-rRNA levels were determined using qRT-PCR. *P<0.05 vs. EV in each group, n=4. E, Transcription initiation complexes. SL1 binds to promoter region and recruits preinitiation complex. Then TIF-IA helps Pol I bind to the SL1 complex and start transcription. AMPK complexes containing γ2 binds to both SL1 and TIF-IA and disassemble the complex through phosphorylation of TIF-1A.

Activation of γ2-AMPK protected against ER stress and cell death

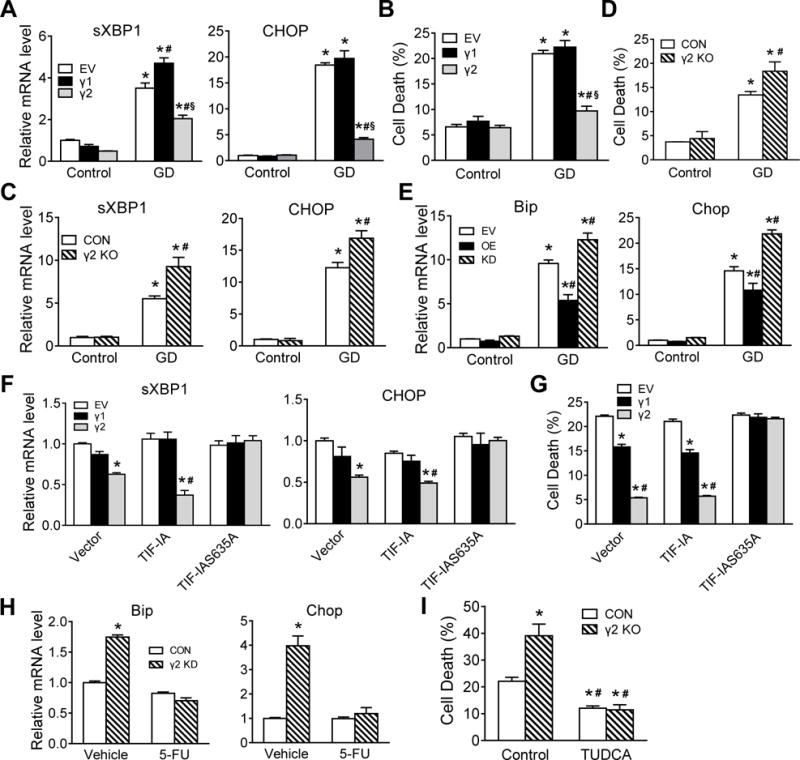

We next tested whether suppression of rRNA synthesis contributed to attenuated ER stress. Upregulations of spliced X-box binding protein-1 (XBP1) and C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP), hallmarks of ER stress and unfolded protein response,24 were suppressed by overexpression of γ2-AMPK during GD (Figure 4A). Similarly, GD-induced cell death was also reduced by γ2-AMPK overexpression (Figure 4B). Conversely, γ2-AMPK knockout exacerbated the upregulation of spliced XBP1 and CHOP, and increased cell death upon GD (Figure 4C and 4D). In NRVM, γ2 overexpression suppressed whereas γ2 knockdown enhanced ER stress markers Bip and Chop upon GD (Figure 4E). To determine whether the inhibition of ER stress and cell death is mediated by reduced rRNA synthesis, we transfected stable cell lines expressing γ1- or γ2-AMPK with wildtype TIF-IA or TIF-IAS635A and incubated the cells with glucose-free medium. Overexpression of γ2 but not γ1-AMPK suppressed spliced XBP1 and CHOP expression in control (vector) or TIF-IA group, and the effect was abolished in TIF-IAS635A group (Figure 4F). Consistent with these observations, a greater reduction of cell death was achieved by γ2 overexpression during glucose deprivation, and the protection was abrogated by TIF-IAS635A (Figure 4G). To determine if γ2 attenuates ER stress in a ribosome biogenesis-dependent way, NRVM with γ2 knockdown were treated with 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), an inhibitor of ribosomal RNA synthesis.25 Upon GD, 5-FU treatment abrogated the upregulation of Bip and Chop induced by γ2 knockdown, suggesting that γ2-AMPK attenuates ER stress through suppressing ribosome biogenesis (Figure 4H). Moreover, treatment with sodium tauroursodeoxycholate (TUDCA), a chemical chaperone that reduces ER stress,26 inhibited glucose deprivation-induced cell death to the same extent in control and γ2 KO cells (Figure 4I), further supporting the notion that activation of γ2-AMPK reduced ER stress. These data collectively indicate that γ2-AMPK protects against ER stress and cell death through inhibiting rRNA synthesis.

Figure 4. γ2-AMPK protects against ER stress and cell death under stress.

A,B, Relative spliced XBP1 and CHOP mRNAs (A) and cell death (B) in HEK293 cells stably expressing EV, γ1 or γ2 under control or GD condition (24h). *P<0.05 vs. EV/Control, #P<0.05 vs. EV/GD, §P<0.05 vs. γ1/GD, n=4–5. C,D, Relative spliced XBP1 and CHOP mRNAs (C) and cell death (D) in control (CON) and γ2 knockout (γ2 KO) HEK293 cells under control or GD condition (24h). *P<0.05 vs. CON/Control, #P<0.05 vs. CON/GD, n=4. E, Relative Bip and Chop mRNAs in NRVM expressing EV, γ2 OE or γ2 KD under control or GD condition (24h). *P<0.05 vs. EV/Control, #P<0.05 vs. EV/GD, n=5. F,G, HEK293 cells stably expressing EV, γ1 or γ2 were transfected with empty vector (Vector), wildtype TIF-IA (TIF-IA) or mutant (TIF-IAS635A) accompanied by GD (24h). Relative spliced XBP1 and CHOP levels (F) and cell death (G) were determined. *P<0.05 vs. EV in each group, #P<0.05 vs. γ1 in each group, n=4. H, NRVM expressing CON or γ2 KD were subjected to GD (24h) with or without 25 μmol/L 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) treatment (6h). Relative Bip and Chop mRNAs were determined using qRT-PCR. *P<0.05 vs. CON/Vehicle, n=4. I, HEK293 cells stably expressing CON or γ2 KO were subjected to GD with or without 0.5 mmol/L Sodium tauroursodeoxycholate (TUDCA) treatment for 24h. Cell death was determined using CellTox Green Cytotoxicity Assay. *P<0.05 vs. CON/Control, #P<0.05 vs. γ2 KO/Control, n=4.

The γ2-AMPK was required for protection against ischemia/reperfusion injury in vivo

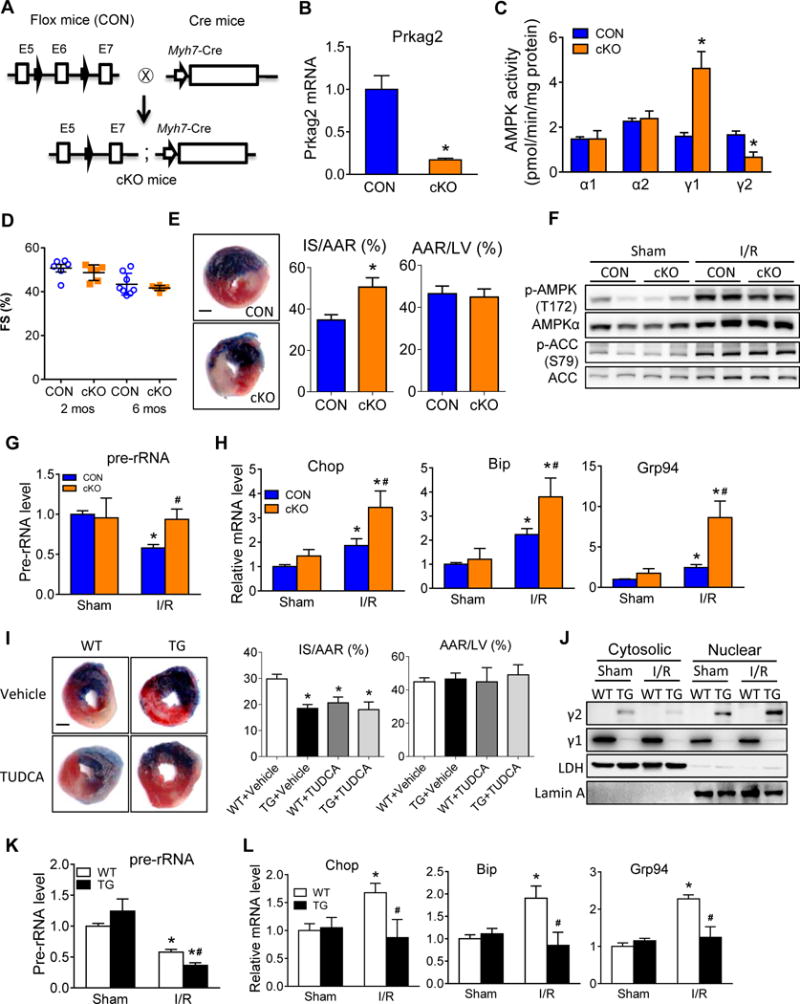

To test the role of γ2-AMPK in cardiac stress response we generated a mouse model with cardiac specific deletion of the γ2-subunit (cKO) by targeting the exon 6 of the Prkag2 gene using the Cre/loxP system. Deletion of exon 6 introduced a frameshift mutation in exon 7 resulting in a null mutation in Prkag2 (Figure 5A). The mRNA level and activity of γ2-AMPK in cKO hearts were significantly reduced compared to littermate control hearts (Figure 5B and 5C). Immunoprecipitation with anti-γ2 antibody in the cKO yielded no detectable α subunit, further confirming the successful deletion of the γ2-AMPK isoform in the heart (Online Figure VA). Increases in the γ1-AMPK activity in cKO hearts maintain the total AMPK activity (Figure 5C). The cKO mice were born normal and remained indistinguishable from their control mice in terms of heart weight and cardiac function for up to 6 months (Figure 5D; Online Figure VB and VC). When the mice were subjected to 30-minute ischemia followed by 24-hour reperfusion, cKO hearts showed larger infarct size (Figure 5E). The total AMPK activity in cKO heart was normal at baseline and it increased after I/R injury to the same extent as that of the controls (Figure 5F). However, ischemia failed to induce TIF-1A phosphorylation in the area at risk or suppress pre-rRNA level in cKO (Online Figure VD; Figure 5G). Moreover, I/R injury induced a significantly greater increase of Chop, Bip and Grp94 mRNA measured in the ischemic area at risk of cKO (Figure 5H) suggesting elevated ER stress in these hearts. Conversely, γ2-AMPK transgenic mice (TG) showed smaller infarct size after I/R injury (Figure 5I). Inhibition of ER stress by TUDCA27 reduced infarct size in WT mice, but didn’t further reduce infarct size in TG mice, suggesting that reduction of ER stress mimics the effects of γ2-AMPK overexpression (Figure 5I). Nuclear accumulation of γ2-subunit was shown in TG hearts after I/R injury (Figure 5J) accompanied by further suppression of pre-rRNA (Figure 5K) and reduced ER stress markers (Figure 5L). Consistent with previous report, we found that the total AMPK activity was unaltered in TG heart (Online Figure VE and VF).28 Taken together, our results identified isoform-specific functions of γ2-AMPK in regulating rRNA synthesis and ER stress that are critical for cardiac response to I/R injury.

Figure 5. γ2-AMPK cKO sensitizes the heart to ischemia/reperfusion injury in vivo.

A, Strategy of targeting of the Prkag2 gene (encodes γ2 subunit of AMPK) to generate mice with cardiac specific deletion of γ2-AMPK (cKO). B, Relative Prkag2 mRNA level in heart tissue harvested from control (CON) and cKO mice. *P<0.05 vs. CON, n=9. C, Activity of AMPK subunits in heart tissue harvested from CON and cKO mice. *P<0.05 vs. CON in each group, n=4. D, Echocardiographic data depicting fractional shortening (FS) in CON and cKO mice at 2 and 6 months (n=3–4). E, CON and cKO mice were subjected to 30-minute ischemia and 24-hour reperfusion. Representative images (left), infarct size relative to area at risk (IS/AAR; middle) and AAR relative to left ventricle (AAR/LV, right) were shown from Evans blue and Triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC) double-stained heart sections. Blue, remote area; white, infarct area; red and white, area at risk; whole section, left ventricle; Scale bar, 1 mm. *P<0.05 vs. CON, n=8. F, Phosphorylated AMPK α subunits at residue T172 (p-AMPK(T172)), total AMPK α subunits (AMPKα), phosphorylated ACC at residue S79 (p-ACC(S79)) and total ACC levels in whole heart lysates of CON and cKO mice after sham or I/R surgery. G, Relative pre-rRNA levels in ischemic border area of CON and cKO hearts after sham or I/R surgery. *P<0.05 vs. CON/Sham, #P<0.05 vs. CON/I/R, n=4. H, Relative expression of Chop, Bip and Grp94 in CON and cKO hearts after sham or I/R surgery. Tissue from ischemic border area was collected for RNA extraction. *P<0.05 vs. CON/Sham, #P<0.05 vs. CON/I/R, n=4. I, WT and TG mice treated with Vehicle or TUDCA were subjected to 30-minute ischemia and 24-hour reperfusion. Representative images (left), average IS/AAR (middle) and AAR/LV (right) of Evans blue and TTC double-stained heart sections were shown. Scale bar, 1 mm. *P<0.05 vs. WT, n=8. J, Cytosolic and nuclear fractions were isolated from WT and TG hearts after sham or I/R surgery. Protein levels of γ subunits were measured by western blot. LDH and Lamin A serve as loading control for cytosolic and nuclear fraction, respectively (n=4). K, Relative expression of pre-rRNA in WT and TG hearts after sham or I/R surgery. *P<0.05 vs. WT/Sham, #P<0.05 vs. WT/I/R, n=4. L, Relative expression of Chop, Bip and Grp94 in WT and TG hearts after sham or I/R surgery. Tissue from ischemic area at risk was collected for RNA extraction. *P<0.05 vs. WT/Sham, #P<0.05 vs. WT/I/R, n=3–4.

DISCUSSION

In this study we have demonstrated novel functional characteristics of γ2-AMPK in the heart. First, activation of AMPK during stress promotes nuclear translocation of the γ2 subunit forming a complex of α2/β1/γ2. Second, nuclear accumulation of the γ2-AMPK complex is responsible for the phosphorylation and inactivation of TIF-IA, precluding the assembly of transcription initiation complexes for rDNA. Third, γ2-AMPK mediated suppression of rRNA synthesis attenuates ER stress and reduces cell death, and finally, the activity of γ2-AMPK is required for the reduction of ER stress and protection against ischemia/reperfusion in mouse heart.

The γ subunit of the AMPK contains two pairs of the cystathionine β-synthase (CBS) domains in its C-terminus that bind AMP or ATP, thus functions as a sensor of the intracellular energy status.29 Among the three isoforms, γ1 and γ2 are widely expressed while γ3 is only detected in skeletal muscle. In majority of tissues, including the heart, γ1 is the most abundant isoform and AMPK complex containing γ1 subunit likely contributes more than 80% of total AMPK activity in adult cells.8, 30 Previous studies on AMPK function primarily focused on the overall kinase activity and most of them used complexes containing the γ1-subunit. Structurally, the three isoforms of the γ-subunit bear high similarity in the C-terminus but differ in the length of the N-terminus. As shown here, the γ2/3 isoforms possess a nucleus localization sequence in their N-terminus which is not present in the γ1-subunit that has a short N-terminus sequence before the CBS domains. Results of our study further suggest that the isoform composition is an important determinant of AMPK activity in specific subcellular compartment. The present findings corroborate with recent reports showing that γ1-AMPK is largely detected in the cytoskeleton while γ2-AMPK is present in the nucleus during mitosis.6, 8 These observations collectively identify a novel role of γ-subunit in addition to its sensor function, and provide a mechanism for isoform-specific function of the AMPK.

It has been increasingly recognized that AMPK maintains energy homeostasis by regulating both ATP production and consumption. AMPK is a negative regulator of protein synthesis, a highly energy-consuming process, through repressing mTOR activity31, 32 and subsequent downregulation of eukaryotic protein translation initiation factor 4E-binding protein (4E-BP) and p70 ribosomal protein S6 kinase (S6K). AMPK also inactivates eukaryotic elongation factor-2 (eEF2), another important player in protein synthesis by activating eEF2 kinase.33 In contrast to this well-established notion, both mTOR activity and S6 phosphorylation are increased in mouse models with predominant activation of γ2-AMPK17, 34 suggesting that the AMPK effect on this pathway is dependent on the γ isoform. Here we demonstrate a distinct mechanism by which γ2-AMPK regulates protein synthesis via transient nuclear translocation and suppression of rRNA synthesis during acute stress. It is thus likely that coordinated effects in the nucleus, by γ2-AMPK, and in the cytosol, likely mediated by γ1-AMPK, are required for the downregulation of protein synthesis under these conditions.

Previous studies have identified multiple mechanisms through which activation of AMPK leads to cardioprotection.12, 13, 15, 35, 36 Although AMPK activity is very low in normal heart, it is activated rapidly and robustly by stresses, including ischemia. By stimulating glucose uptake and glycolysis, AMPK prevents cardiac dysfunction and apoptosis caused by ischemia and reperfusion.12 Consistently, inhibition of AMPK α2 activity in mouse hearts by overexpressing dominant negative α2 subunit leads to accelerated ATP depletion and exacerbated dysfunction during ischemia.15 Activation of AMPK in neonatal rat cardiomyocytes attenuates hypoxia-induced ER stress and protein synthesis in an eEF2 kinase-dependent mechanism.37 However, studies thus far have attributed the benefit of AMPK to its total activity rather than isoform-specific function. Here our results unveil a novel mechanism of cardioprotection specifically mediated by AMPK containing the γ2-subunit through nuclear translocation and repression of rRNA synthesis. In mouse heart, deletion of γ2-subunit does not reduce the total AMPK activity under normal or stressed conditions. The failure to suppress rRNA transcription in the cKO heart is thus attributable to the loss of the γ2-specific function.

The concept of targeting isoform-specific function of AMPK has long been proposed in drug development. This is particularly attractive for cardioprotection since human mutations of PRKAG2 cause chronic activation of γ2-AMPK and metabolic cardiomyopathy. Results from the present study has added critical knowledge for the isoform-selective approach in targeting AMPK. We show that γ2-AMPK activity is dispensable under normal condition but plays an important role in cardioprotection not compensated by the upregulation of γ1-AMPK activity. Selective increase of γ1-AMPK activity, hence, may not achieve the desired outcome in protection against I/R injury. It remains to be determined whether chronic activation of γ1-AMPK activity would avoid the development of cardiomyopathy caused by Prkag2 mutation. Nevertheless, the γ2-KO mouse model described here provides an excellent tool for future studies in this direction.

In summary, we show that nuclear translocation of γ2-AMPK plays a critical role in protecting myocardium from ischemia/reperfusion injury via reducing rRNA synthesis and ER stress. Revelation of the isoform-specificity of this function expands our knowledge of AMPK beyond total kinase activity, which is highly significant for future drug development targeting the AMPK complex.

Supplementary Material

NOVELTY AND SIGNIFICANCE.

What Is Known?

AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) is a heterotrimeric protein (αβγ) that functions to maintain energy homeostasis during stress.

Activation of AMPK during myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury is cardioprotective.

Two isoforms of each subunit are expressed in the heart but the isoform-specific function of AMPK remains unclear.

What New Information Does This Article Contribute?

Activation of AMPK causes rapid translocation of the γ2-subunit into the nucleus and the formation of a α2β1γ2 complex.

Nuclear accumulation γ2-AMPK reduces ribosomal biosynthesis through suppression of the preribosomal RNA (pre-rRNA) transcription.

The lack of γ2-AMPK failes to suppress pre-rRNA level and ER stress, thus sensitizing the heart to myocardial ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury.

Using both in vitro and in vivo models we show that AMPK complex containing γ2 subunit translocates into the nucleus to suppress pre-rRNA transcription and ribosome biosynthesis under stress conditions, which ameliorates ER stress response and cell death. In mice with cardiac specific deletion of γ2-AMPK, the total AMPK activity is unaltered but the lack of γ2-AMPK results in elevated ER stress and a greater infarct size upon ischemia/reperfusion insult. In contrast, overexpression of γ2-AMPK in the heart reduces ER stress and infarct size in mice. Thus, our study reveals an isoform-specific function of γ2-AMPK in cell survival and cardioprotection through nuclear translocation and repression of rRNA synthesis. This is distinct from previously known function of AMPK in modulating energy metabolism and growth signaling. Revelation of the isoform-specificity of this function expands our knowledge of AMPK beyond total kinase activity, which provides an important basis for future drug development targeting the AMPK complex.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Tamas Balla (NIH) for providing the pEGFP-C1-TK vector and University of Washington’s Proteomics Resource (UWPR) for proteomics technology platform.

SOURCES OF FUNDING

This study was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health HL067970, HL088634, HL118989, and HL129510 (to R.T.).

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- AMPK

AMP-activated protein kinase

- pre-rRNA

preribosomal RNA

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- I/R

ischemia/reperfusion

- NLS

nuclear localization sequence

- NES

nuclear export sequence

- GD

glucose deprivation

- SL1

selectivity factor 1

- TIF-IA

RNA Pol I-associated transcription factor

- UPR

unfolded protein response

- XBP1

X-box binding protein-1

- CHOP

C/EBP homologous protein

- GRP94

glucose regulated protein 94

- Bip

binding immunoglobulin protein

- TUDCA

sodium tauroursodeoxycholate

- CBS

cystathionine β-synthase

- S6K

ribosomal protein S6 kinase

- 4E-BP

translation initiation factor 4E-binding protein

- eEF2

eukaryotic elongation factor-2

- mTOR

mammalian target of rapamycin

- NRVM

neonatal rat ventricular myocytes

- 5-FU

5-fluorouracil

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

R.T., Y.C., N.B. and M.K. designed all experiments. Y.C., N.B., M.K., T.L. and P.Z. performed the experiments. R.T. and J.S. supervised the study. R.D.P supervised cKO mice generation. Y.C., N.B., M.K., T.L. and N.N. analyzed the data. R.T., N.B. and Y.C. wrote the manuscript.

DISCLOSURES

None.

References

- 1.Hardie DG. Amp-activated protein kinase: An energy sensor that regulates all aspects of cell function. Genes & development. 2011;25:1895–1908. doi: 10.1101/gad.17420111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carling D, Mayer FV, Sanders MJ, Gamblin SJ. Amp-activated protein kinase: Nature’s energy sensor. Nature chemical biology. 2011;7:512–518. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stapleton D, Woollatt E, Mitchelhill KI, Nicholl JK, Fernandez CS, Michell BJ, Witters LA, Power DA, Sutherland GR, Kemp BE. Amp-activated protein kinase isoenzyme family: Subunit structure and chromosomal location. FEBS letters. 1997;409:452–456. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00569-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stapleton D, Mitchelhill KI, Gao G, Widmer J, Michell BJ, Teh T, House CM, Fernandez CS, Cox T, Witters LA, Kemp BE. Mammalian amp-activated protein kinase subfamily. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1996;271:611–614. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.2.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Birk JB, Wojtaszewski JF. Predominant alpha2/beta2/gamma3 ampk activation during exercise in human skeletal muscle. The Journal of physiology. 2006;577:1021–1032. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.120972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pinter K, Jefferson A, Czibik G, Watkins H, Redwood C. Subunit composition of ampk trimers present in the cytokinetic apparatus: Implications for drug target identification. Cell cycle. 2012;11:917–921. doi: 10.4161/cc.11.5.19412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scott JW, Hawley SA, Green KA, Anis M, Stewart G, Scullion GA, Norman DG, Hardie DG. Cbs domains form energy-sensing modules whose binding of adenosine ligands is disrupted by disease mutations. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2004;113:274–284. doi: 10.1172/JCI19874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheung PC, Salt IP, Davies SP, Hardie DG, Carling D. Characterization of amp-activated protein kinase gamma-subunit isoforms and their role in amp binding. The Biochemical journal. 2000;346(Pt 3):659–669. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gollob MH, Seger JJ, Gollob TN, Tapscott T, Gonzales O, Bachinski L, Roberts R. Novel prkag2 mutation responsible for the genetic syndrome of ventricular preexcitation and conduction system disease with childhood onset and absence of cardiac hypertrophy. Circulation. 2001;104:3030–3033. doi: 10.1161/hc5001.102111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arad M, Benson DW, Perez-Atayde AR, McKenna WJ, Sparks EA, Kanter RJ, McGarry K, Seidman JG, Seidman CE. Constitutively active amp kinase mutations cause glycogen storage disease mimicking hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2002;109:357–362. doi: 10.1172/JCI14571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blair E, Redwood C, Ashrafian H, Oliveira M, Broxholme J, Kerr B, Salmon A, Ostman-Smith I, Watkins H. Mutations in the gamma(2) subunit of amp-activated protein kinase cause familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: Evidence for the central role of energy compromise in disease pathogenesis. Human molecular genetics. 2001;10:1215–1220. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.11.1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Russell RR, 3rd, Li J, Coven DL, Pypaert M, Zechner C, Palmeri M, Giordano FJ, Mu J, Birnbaum MJ, Young LH. Amp-activated protein kinase mediates ischemic glucose uptake and prevents postischemic cardiac dysfunction, apoptosis, and injury. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2004;114:495–503. doi: 10.1172/JCI19297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim AS, Miller EJ, Wright TM, Li J, Qi D, Atsina K, Zaha V, Sakamoto K, Young LH. A small molecule ampk activator protects the heart against ischemia-reperfusion injury. Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology. 2011;51:24–32. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Young LH, Li J, Baron SJ, Russell RR. Amp-activated protein kinase: A key stress signaling pathway in the heart. Trends in cardiovascular medicine. 2005;15:110–118. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xing Y, Musi N, Fujii N, Zou L, Luptak I, Hirshman MF, Goodyear LJ, Tian R. Glucose metabolism and energy homeostasis in mouse hearts overexpressing dominant negative alpha2 subunit of amp-activated protein kinase. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2003;278:28372–28377. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303521200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gundewar S, Calvert JW, Jha S, Toedt-Pingel I, Ji SY, Nunez D, Ramachandran A, Anaya-Cisneros M, Tian R, Lefer DJ. Activation of amp-activated protein kinase by metformin improves left ventricular function and survival in heart failure. Circulation research. 2009;104:403–411. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.190918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yavari A, Stocker CJ, Ghaffari S, Wargent ET, Steeples V, Czibik G, Pinter K, Bellahcene M, Woods A, Martinez de Morentin PB, Cansell C, Lam BY, Chuster A, Petkevicius K, Nguyen-Tu MS, Martinez-Sanchez A, Pullen TJ, Oliver PL, Stockenhuber A, Nguyen C, Lazdam M, O’Dowd JF, Harikumar P, Toth M, Beall C, Kyriakou T, Parnis J, Sarma D, Katritsis G, Wortmann DD, Harper AR, Brown LA, Willows R, Gandra S, Poncio V, de Oliveira Figueiredo MJ, Qi NR, Peirson SN, McCrimmon RJ, Gereben B, Tretter L, Fekete C, Redwood C, Yeo GS, Heisler LK, Rutter GA, Smith MA, Withers DJ, Carling D, Sternick EB, Arch JR, Cawthorne MA, Watkins H, Ashrafian H. Chronic activation of gamma2 ampk induces obesity and reduces beta cell function. Cell metabolism. 2016;23:821–836. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oakhill JS, Steel R, Chen ZP, Scott JW, Ling N, Tam S, Kemp BE. Ampk is a direct adenylate charge-regulated protein kinase. Science. 2011;332:1433–1435. doi: 10.1126/science.1200094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoppe S, Bierhoff H, Cado I, Weber A, Tiebe M, Grummt I, Voit R. Amp-activated protein kinase adapts rrna synthesis to cellular energy supply. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:17781–17786. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909873106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luptak I, Shen M, He H, Hirshman MF, Musi N, Goodyear LJ, Yan J, Wakimoto H, Morita H, Arad M, Seidman CE, Seidman JG, Ingwall JS, Balschi JA, Tian R. Aberrant activation of amp-activated protein kinase remodels metabolic network in favor of cardiac glycogen storage. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2007;117:1432–1439. doi: 10.1172/JCI30658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li T, Zhang Z, Kolwicz SC, Jr, Abell L, Roe ND, Kim M, Zhou B, Cao Y, Ritterhoff J, Gu H, Raftery D, Sun H, Tian R. Defective branched-chain amino acid catabolism disrupts glucose metabolism and sensitizes the heart to ischemia-reperfusion injury. Cell metabolism. 2017;25:374–385. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Steinberg GR, Watt MJ, McGee SL, Chan S, Hargreaves M, Febbraio MA, Stapleton D, Kemp BE. Reduced glycogen availability is associated with increased ampkalpha2 activity, nuclear ampkalpha2 protein abundance, and glut4 mrna expression in contracting human skeletal muscle. Applied physiology, nutrition, and metabolism = Physiologie appliquee, nutrition et metabolisme. 2006;31:302–312. doi: 10.1139/h06-003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McGee SL, Howlett KF, Starkie RL, Cameron-Smith D, Kemp BE, Hargreaves M. Exercise increases nuclear ampk alpha2 in human skeletal muscle. Diabetes. 2003;52:926–928. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.4.926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Schadewijk A, van’t Wout EF, Stolk J, Hiemstra PS. A quantitative method for detection of spliced x-box binding protein-1 (xbp1) mrna as a measure of endoplasmic reticulum (er) stress. Cell stress & chaperones. 2012;17:275–279. doi: 10.1007/s12192-011-0306-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pyrko P, Schonthal AH, Hofman FM, Chen TC, Lee AS. The unfolded protein response regulator grp78/bip as a novel target for increasing chemosensitivity in malignant gliomas. Cancer research. 2007;67:9809–9816. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xie Q, Khaoustov VI, Chung CC, Sohn J, Krishnan B, Lewis DE, Yoffe B. Effect of tauroursodeoxycholic acid on endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced caspase-12 activation. Hepatology. 2002;36:592–601. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.35441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li Y, Zhu W, Tao J, Xin P, Liu M, Li J, Wei M. Fasudil protects the heart against ischemia-reperfusion injury by attenuating endoplasmic reticulum stress and modulating serca activity: The differential role for pi3k/akt and jak2/stat3 signaling pathways. PloS one. 2012;7:e48115. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zou L, Shen M, Arad M, He H, Lofgren B, Ingwall JS, Seidman CE, Seidman JG, Tian R. N488i mutation of the gamma2-subunit results in bidirectional changes in amp-activated protein kinase activity. Circulation research. 2005;97:323–328. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000179035.20319.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Day P, Sharff A, Parra L, Cleasby A, Williams M, Horer S, Nar H, Redemann N, Tickle I, Yon J. Structure of a cbs-domain pair from the regulatory gamma1 subunit of human ampk in complex with amp and zmp. Acta crystallographica. Section D, Biological crystallography. 2007;63:587–596. doi: 10.1107/S0907444907009110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim M, Shen M, Ngoy S, Karamanlidis G, Liao R, Tian R. Ampk isoform expression in the normal and failing hearts. Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology. 2012;52:1066–1073. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2012.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Inoki K, Zhu T, Guan KL. Tsc2 mediates cellular energy response to control cell growth and survival. Cell. 2003;115:577–590. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00929-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gwinn DM, Shackelford DB, Egan DF, Mihaylova MM, Mery A, Vasquez DS, Turk BE, Shaw RJ. Ampk phosphorylation of raptor mediates a metabolic checkpoint. Molecular cell. 2008;30:214–226. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Horman S, Browne G, Krause U, Patel J, Vertommen D, Bertrand L, Lavoinne A, Hue L, Proud C, Rider M. Activation of amp-activated protein kinase leads to the phosphorylation of elongation factor 2 and an inhibition of protein synthesis. Current biology: CB. 2002;12:1419–1423. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)01077-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim M, Hunter RW, Garcia-Menendez L, Gong G, Yang YY, Kolwicz SC, Jr, Xu J, Sakamoto K, Wang W, Tian R. Mutation in the gamma2-subunit of amp-activated protein kinase stimulates cardiomyocyte proliferation and hypertrophy independent of glycogen storage. Circulation research. 2014;114:966–975. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.302364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zarrinpashneh E, Carjaval K, Beauloye C, Ginion A, Mateo P, Pouleur AC, Horman S, Vaulont S, Hoerter J, Viollet B, Hue L, Vanoverschelde JL, Bertrand L. Role of the alpha2-isoform of amp-activated protein kinase in the metabolic response of the heart to no-flow ischemia. American journal of physiology. Heart and circulatory physiology. 2006;291:H2875–2883. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01032.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Paiva MA, Rutter-Locher Z, Goncalves LM, Providencia LA, Davidson SM, Yellon DM, Mocanu MM. Enhancing ampk activation during ischemia protects the diabetic heart against reperfusion injury. American journal of physiology. Heart and circulatory physiology. 2011;300:H2123–2134. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00707.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Terai K, Hiramoto Y, Masaki M, Sugiyama S, Kuroda T, Hori M, Kawase I, Hirota H. Amp-activated protein kinase protects cardiomyocytes against hypoxic injury through attenuation of endoplasmic reticulum stress. Molecular and cellular biology. 2005;25:9554–9575. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.21.9554-9575.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.