Abstract

Infections caused by non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) is increasing wordwide. Due to the difference in treatment of NTM infections and tuberculosis, rapid species identification of mycobacterial clinical isolates is necessary for the effective management of mycobacterial diseases treatment and their control strategy. In this study, a cost-effective technique, real-time PCR coupled with high-resolution melting (HRM) analysis, was developed for the differentiation of Mycobacterial species using a novel rpoBC sequence. A total of 107 mycobacterial isolates (nine references and 98 clinical isolates) were subjected to differentiation using rpoBC locus sequence in a real-time PCR-HRM assay scheme. From 98 Mycobacterium clinical isolates, 88 species (89.7%), were identified at the species level by rpoBC locus sequence analysis as a gold standard method. M. simiae was the most frequently encountered species (41 isolates), followed by M. fortuitum (20 isolates), M. tuberculosis (15 isolates), M. kansassi (10 isolates), M. abscessus group (5 isolates), M. avium (5 isolates), and M. chelonae and M. intracellulare one isolate each. The HRM analysis generated six unique specific groups representing M. tuberculosis complex, M. kansasii, M. simiae, M. fortuitum, M. abscessus–M. chelonae group, and M. avium complex. In conclusion, this study showed that the rpoBC-based real-time PCR followed by HRM analysis could differentiate the majority of mycobacterial species that are commonly encountered in clinical specimens.

Keywords: non-tuberculous mycobacteria, HRM assay, PCR, rpoBC locus, melting curve

Introduction

The genus Mycobacterium encompass several acid-fast bacilli (AFB), including Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex, Mycobacterium leprae, and non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) (Bottai et al., 2014). The number of NTM species is increasing dramatically with the number of more than 190 species and subspecies in 20171, mainly due to the progresses in identification techniques (Tortoli, 2014). Despite the fact that NTM are typically environmental organisms, several species have been known to be important human pathogens, and recently their infections have been increasingly reported (Johnson and Odell, 2014). According to the American Thoracic Society (ATS) guideline, clinically isolated NTM should be identified to the species level to determine their clinical significance, infection control, epidemiological analysis, and patient management (Griffith et al., 2007). Traditional methods including the phenotypic tests are slow, cumbersome and often not definitive (Kent and Kubica, 1985; Springer et al., 1996; Tortoli, 2003). The PCR-based sophisticated techniques such as sequencing, PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis (PRA) and microarray analysis are still time-consuming, need cumbersome process and occasionally lead to inaccurate species identification (Lim et al., 2008; Li et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2010; Dai et al., 2011). Several multiplex real time PCR have been used for rapid identification of mycobacterial species but species identification is restricted to the number of species-specific primers (Tobler et al., 2006; Richardson et al., 2009; Ngan et al., 2011; Reddington et al., 2011). High-resolution melting curve (HRM) analysis is a homogeneous, closed-tube post-PCR method for identifying single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), novel mutations, methylation patterns, and species identification. Recently, HRM assay has been used as a simple, low cost and rapid method in mycobacterial research works such as investigation of drug resistance among M. tuberculosis (Pietzka et al., 2009; Ramirez et al., 2010), or mycobacterial species identification (Perng et al., 2012; Issa et al., 2014; Chen et al., 2017). However, most of the latter analyses could only discriminate NTM into group or complex level. In this study, we developed a rapid real-time PCR- HRM assay targeting rpoBC locus. This target is used for the first time for species identification of mycobacteria.

Materials and Methods

Sample Collection and Bacterial Strains

In this experimental study, eight reference strains including laboratory standard strains (M. tuberculosis H37Rv ATCC 27294, M. bovis BCG Pasteur ATCC 35734, M. abscessus ATCC 19977, M. chelonae ATCC 35752, M. fortuitum ATCC 49403, M. kansasii DSM 44162, M. simiae ATCC, M. avium ATCC 25291), and 98 clinical isolates suspected to NTM were tested. Clinical isolates were recovered from the pulmonary specimens at the selected Regional TB Reference laboratories of Iran, from January 2014 to May 2016. The study was approved by Institutional Ethics and Review Board (Code: IR.AJUMS.REC.1395.223), after submission of preliminary proposal and necessary permission for sample collection was granted. All isolates were recovered from clinical specimens containing acid fast bacilli on direct smear. For initial identification, conventional phenotypic and biochemical tests such as growth at 25, 37, and 42°C, pigment production, semi-quantitative catalase test, Tween 80 hydrolysis, arylsulfatase test (3 and 14 days), heat-stable catalase (pH 7, 68°C), pyrazinamidase (4 and 7 days), urease, nitrate reduction test and colony morphology were performed (Mahon et al., 2014). The contaminated samples or the isolates not matching with the ATS criteria for definition of NTM disease were excluded from the study.

DNA Extraction

The DNA was extracted using the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Germany). In brief, colonies grown on Lowen-Stein Jenson (LJ) medium were harvested and re-suspended in 0.5 ml of sterile double-distilled water and inactivated at 80°C for 20 min. After thermal inactivation, 5 μl lysozyme (10 mg/ml in 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0) was added and incubated for 15 min at 37°C. Other steps of extraction were performed according to manufacturer’s instructions. DNA concentrations and purity were determined using Nano Drop one (Thermo Scientific NanoDrop, United States) at 260 nm. Purified DNA was stored at -70°C for subsequent experiments.

Nucleotide Sequencing

For definitive identification, nearly a 500-bp fragment of the rpoBC locus was amplified using a set of primers of rpoBCF1 (5′-GAGATGGAGTGCTGGGCCATGC-3′) and rpoBCR1 (5′-CCGAAGATCTTCTCGCAGAACAG-3′) as previously described (Dai et al., 2011). The cycling condition was 95°C for 1 min, followed by 30 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, 72°C for 30 s with a final 72°C for 5 min. The amplified PCR products of rpoBC locus for each isolate were purified with the Gene JETTM Gel Extraction Kit (Fermentas, Lithuania) as per manufacturer’s instructions. The sequences of the products were determined using an ABI PRISM 7500 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, United States) according to the standard protocol of the supplier.

Sequence Data and Phylogenetic Analysis

The sequences of rpoBC locus for each isolate were confirmed by BLAST separately, and multiple sequence alignment (MSA) were done for our sequences and all existing relevant sequences of mycobacteria recovered from GenBank database, using MEGA6 program (Tamura et al., 2013). Percentages of similarity between sequences of rpoBC locus were determined by comparing sequences to an in-house database of rpoBC sequences. Phylogenetic trees were obtained from DNA sequences based on 500 bp fragments using the Neighbor-Joining (NJ) method and Kimura’s two parameter (K2P) distance correction model with 1000 bootstrap replications supported by the MEGA6 software.

Primer Design for Real-Time PCR-HRM Assay

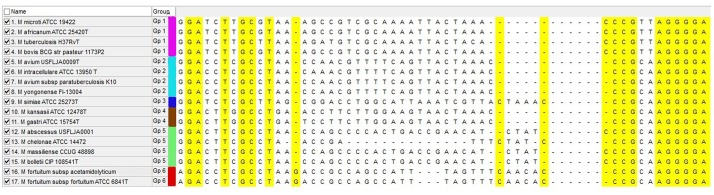

According to the MSA result, we found a hypervariable region flanked by conserved area, suitable for genus specific universal primer designing. Based on this suitable region, a forward primer (5′-AAT CAA CCT GTC GCG CAA CGA-3′) and a reverse primer (5′-GTT CAT CGA AGA AGT TGA CGT-3′) were designed by using Gene runner 3.05 software. Sequence lengths ranged from 115 bp in the M. chelonae species ATCC 35752T to 126 bp in M. abscessus ATCC 19977T. This length variability was due to the variances in the intergenic region between rpoB and rpoC genes (Figure 1). The specificity of the primers were checked by BLAST against the non-mycobacterial genus in GenBank. Primers were not bonded to any non-mycobacterial genus and had a 100% specificity for the Mycobacterium genus.

FIGURE 1.

Multiple sequence alignment of rpoBC locus for mycobacterial species that are frequently present in clinical specimens. Yellow sequences show conserved region that are suitable for primer designing and central region show hyper variable sequences (intergenic region) that are variable between species. Each HRM group is marked with separate color.

Real-Time PCR-HRM Assay

Real-time PCR was performed with a Type-it HRM PCR Kit (QIAGEN, Germany) on a Light Cycler 480 system (Roche Diagnostics, Switzerland). Each PCR analysis contained one primer pair. The amplification was performed using the following conditions: a pre-incubation step at 95°C for 10 min, followed by 45 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 10 s, annealing at 65°C for 30 s, and extension at 72°C for 10 s followed by the Tm analysis with increasing temperatures from 60 to 95°C in a 0.2°C s-1 slope increment for 10 s. The HRM analysis was performed using Gene Scanning Software Version 1.5.0 (Roche Instrument Centre, Switzerland). The clustering of the melting curves was based on the regions of the melting curve corresponding to the pre-melting, melting, and post-melting regions. The sensitivity assay was performed using a 10-fold serial dilution of the M. avium DNA template (107 to 101 genome equivalents ∼50 ng to ∼5 fg respectively) and each set of assays was performed in duplicate samples. The specificity of the assay was evaluated on eight standard non-mycobacterial isolates, including Legionella pneumophila (ATCC 33153), Nocardia farcinica (ATCC 3318), Streptococcus pneumoniae (ATCC 6303), Mycoplasma pneumoniae (ATCC 15293), Bacillus subtilis (ATCC 6633), Klebsiella pneumoniae subsp. pneumoniae (ATCC 13883), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (ATCC 10145), Enterobacter aerogenes (ATCC 13048). Distilled water was used to replace the DNA template for the non-template control (NTC).

Nucleotide Sequence Accession Numbers

The GenBank accession numbers of some investigated isolates of NTM determined in this work are MF109740-109780 (M. simiae isolates), MF109782-MF109786 (M. abscessus group isolates), MF109787-MF109790 (M. avium complex isolates), MF109791-MF109807 (M. fortuitum isolates), MF109808-MF109817 (M. kansasii isolates), MF109735 (M. intracellulare isolate), MF109738 (M. thermoresistable isolate), and MF004241 (M. chelonae isolate) for rpoBC locus.

Results

The primers which were specifically designed for this assay, successfully amplified all Mycobacterium species. The specific products of mycobacteria were distinguished at the temperature of 83.0–89.0°C. When the assay applied on a range of non-mycobacterial species, the primers always yielded Cq values above 30 (below the detection threshold, with no detectable band on agarose gel electrophoresis).

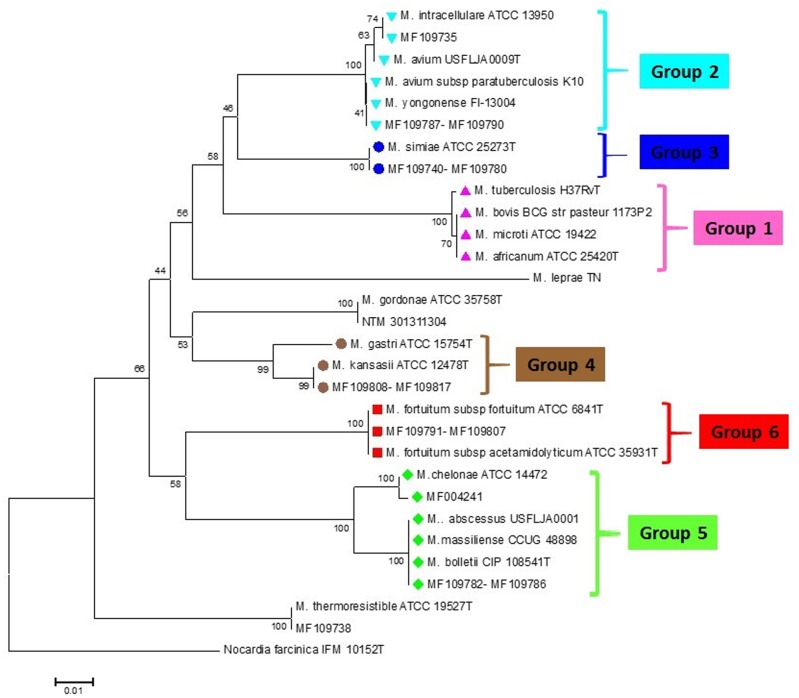

From 98 mycobacterial clinical isolates identified on the basis of phenotypic and biochemical criteria, 88 (89.7%) isolates were identified at the species level by rpoBC locus sequences analysis as a standard method. The neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree based on rpoBC sequences of isolates is shown in Figure 2. The sequence from N. farcinica IFM 10152 was used as an outgroup to construct a rooted tree. The phylogenetic tree based on rpoBC was characterized by high robustness within our isolates (almost 80% of the nodes had bootstrap percentages greater than 75%). M. simiae was the most frequently encountered (41 isolates), following by M. fortuitum (20 isolates), M. tuberculosis (15 isolates), and M. kansassi (10 isolates). The remaining strains were mostly rare mycobacteria comprising one to five isolates including M. abscessus group (5 isolates), M. avium complex (5 isolates), and M. chelonae and M. intracellulare one isolate each. The rpoBC locus provided low discrimination within M. abscessus subspecies and members of M. avium complex, as M. abscessus subsp. abscessus, M. abscessus subsp. bolletii and M. abscessus subsp. massiliense had identical sequences. Also M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis and M. yongonense, belonging to M. avium complex, classified in one group.

FIGURE 2.

rpoBC sequence-based phylogenetic tree of the clinical isolates of NTM with those of closely related species which computed by the NJ analyses and K2P model. The support of each branch, as determined from 1000 bootstrap samples, is indicated by percentages at each node. Bar 0.01 substitutions per nucleotide position. The corresponding HRM groups are specified in the tree.

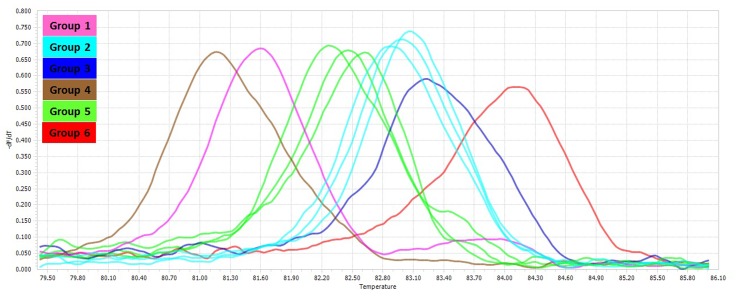

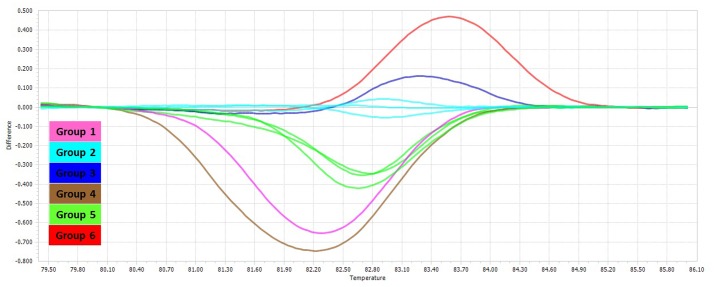

The PCR-HRM assay was performed for differentiation of the mycobacterial species using a designed primer set as shown in Figure 1. The analytical sensitivity for HRM assay were conducted on M. fortuitum DNAs, assuming that results would be comparable for the other species, since the use of equivalent DNA concentrations yielded almost similar Cq values for all the tested species. The detection threshold was set at 30 cycles, because Cq values of negative controls were always between 30 and 35, probably because of a slight primer–dimer formation that was undetectable by agarose gel electrophoresis and by melting curve analysis. Using this threshold, the assay was able to accurately and reproducibly detect as few as 10 copies of M. fortuitum. All 88 clinical strains were classified into six distinct groups. Of these 88 prevalent mycobacterial isolates, 81 mycobacteria (92%) could be identified correctly by real-time PCR-HRM assay. The individual sensitivity and specificity of groups were 90–100 and 97–100% on average respectively. Each HRM groups demonstrated different melting temperature and plot pattern (Figure 3). For type categorization, isolates with difference plots within the ±0.2 relative fluorescence unit cut offs, were considered as the “same” type, while isolates with difference plot outside of the ±0.2 RFU cutoffs were denoted as “different.” According to this criteria, M. tuberculosis (H37Rv, Ra) and M. bovis of the MTBC with 81.60 ± 0.00°C were placed together in group 1. M. avium, M. intracellulare, and M. yongonense of the M. avium complex (MAC) (83.00 ± 0.00, 82.90 ± 0.00, and 83.05 ± 0.00°C, respectively), based on the defined cut off, were placed in a single group (group 2). M. simiae (83.25 ± 0.00°C), M. kansasii (81.15 ± 0.00°C), M. fortuitum (84.12 ± 0.00°C) were placed in groups 3, 4, and 6 respectively. M. chelonae (82.60 ± 0.00°C) and M. abscessus (82.50 ± 0.00°C) with difference plots within 0.2, were categorized together in group 5 (Figure 4).

FIGURE 3.

Comparison of melting curves of different non-tuberculosis mycobacteria. Melting curves corresponding to the HRM groups for the mycobacterial rpoBC locus.

FIGURE 4.

Comparison of HRM different plots of different non-tuberculosis mycobacteria. Difference plot comparison of the six HRM groups for the mycobacterial rpoBC locus.

Discussion

Although sequence based methods are recommended for definitive identification of mycobacterial species (Devulder et al., 2005; Mignard and Flandrois, 2008; Dai et al., 2011; Hashemi-Shahraki et al., 2013; Shahraki et al., 2015), rapid and cost effective techniques such as real time PCR, can be helpful in control and treatment strategies of mycobacterial diseases. In several studies, multiplex real time PCR technique has been used for identification of mycobacterial species (Mokaddas and Ahmad, 2007; Richardson et al., 2009; Ngan et al., 2011; Nasr Esfahani et al., 2012), which a three or four species could be identified in a reaction at maximum. In this study, we developed an in-house PCR-HRM assay targeting rpoBC locus, which could successfully differentiate the predominant Iranian clinical mycobacterial species, including M. tuberculosis, M. avium complex, M. fortuitum, M. kansasii, M. simiae, and M. abscessus–M. chelonae group. Although in theory, HRM assay has high discriminatory power (Yang et al., 2009), in our study, the amplicons of different NTM species (based on rpoBC locus sequence) showed the same or similar melting curves. Similarly, the members of M. tuberculosis complex, except M. tuberculosis, have the same melting curves. Also, members of M. avium complex, M. abscessus, and M. chelonae with different rpoBC locus sequence, had difference plots within the ±0.2 relative fluorescence unit cut offs, that could not be categorized them in distinct groups (Figures 2, 3). Similar findings have been reported in the literature (Yang et al., 2009; Perng et al., 2012). In this study, of six HRM groups, three (groups 3, 4, 6) were in accordance with the phylogenetic tree obtained from rpoBC locus sequences. Perng et al. (2012), evaluated the real time PCR-HRM analysis targeting 16S rRNA gene and ITS region for identification of 134 NTM isolates. Out of 134 isolated isolates, 101 isolates were divided into four groups (M. avium complex, M. chelonae group, M. gordonae, and M. fortuitum group). In compare to our results, they could differentiate fewer distinct groups, occasionally with lower sensitivity and specificity. In Malaysia, Issa et al. (2014), developed a qPCR-HRM analysis using 16S rRNA as target gene for the differentiation of the Mycobacterium species. However, they could not identify some of the species that are frequently present in clinical specimens such as M. simiae, M. fortuitum, M. abscessus, and M. kansasii by their applied method. In a recent study, Chen et al. (2017), high number of clinical NTM species were identified using dual target PCR-HRM analysis. In their study, analysis of the combined 16S rRNA and hsp65 genes HRM types led to 12 unique HRM patterns, representing 15 different species including M. avium, M. intracellulare, M. gordonae, M. kansasii, M. marinum, M. parascrofulaceum, M. scrofulaceum, M. szulgai, M. terrae, M. abscessus, M. chelonae, M. fortuitum, M. mucogenicum, M. neoaurum, M. smegmatis. In contrast to our study, high sensitivity and specificity were seen in Chen et al. (2017) study, so that they could differentiate closely related species such as M. abscessus and M. chelonae. However, we targeted a single locus for species differentiation with the lowest cost.

In current study, the rpoBC locus were used for the first time for mycobacterial species identification in a real time PCR-HRM scheme. This assay is reported previously as a robust technique with high discriminatory power (Dai et al., 2011). In contrast, all other similar studies employed 16S rRNA, ITS (Internal Transcribed spacer) or hsp65 genes as a target gene for PCR-HRM analysis (Douarre et al., 2012; Perng et al., 2012; Phung et al., 2013; Thomson et al., 2013; Issa et al., 2014; Chen et al., 2017).

Conclusion

Our finding showed that this PCR-HRM assay using rpoBC locus as a target, could identify predominant Iranian NTM species in a quick, low-cost and simple method. The total processing time and cost for PCR-HRM assay is significantly much less than PCR-sequencing method. Furthermore, more than 100 samples could be identified simultaneously. Nevertheless, although we investigated prevalent NTM species in clinical samples, it seems that this assay comprise the ability to analyze more NTM species in future studies.

Author Contributions

AK: substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; final approval of the version to be published; agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. AHS: substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. MH: acquisition, analysis, interpretation of data for the work; final approval of the version to be published. AT: analysis, interpretation of data for the work.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We are greatly thankful to staff of Regional TB reference laboratories for their collaboration in sample collection.

Funding. This work is part of Ph.D. thesis of MH, which was approved in Infectious and Tropical Diseases Research Center, and was financially supported by a grant (TB-12) from Research affairs, Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences, Ahvaz, Iran.

References

- Bottai D., Stinear T. P., Supply P., Brosch R. (2014). Mycobacterial Pathogenomics and Evolution. Microbiol Spectr 2:MGM2-0025-2013. 10.1128/microbiolspec.MGM2-0025-2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J. H., Cheng V. C., She K. K., Yam W. C., Yuen K. Y. (2017). Application of a dual target PCR-high resolution melting (HRM) method for rapid nontuberculous mycobacteria identification. J. Microbiol. Methods 132 1–3. 10.1016/j.mimet.2016.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai J., Chen Y., Dean S., Morris J. G., Salfinger M., Johnson J. A. (2011). Multiple-genome comparison reveals new loci for Mycobacterium species identification. J. Clin. Microbiol. 49 144–153. 10.1128/JCM.00957-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devulder G., de Montclos M. P., Flandrois J. P. (2005). A multigene approach to phylogenetic analysis using the genus Mycobacterium as a model. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 55 293–302. 10.1099/ijs.0.63222-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douarre P. E., Cashman W., Buckley J., Coffey A., O’Mahony J. M. (2012). High resolution melting PCR to differentiate Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis“cattle type” and “sheep type.” J. Microbiol. Methods 88 172–174. 10.1016/j.mimet.2011.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith D. E., Aksamit T., Brown-Elliott B. A., Catanzaro A., Daley C., Gordin F., et al. (2007). An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 175 367–416. 10.1164/rccm.200604-571ST [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashemi-Shahraki A., Bostanabad S. Z., Heidarieh P., Titov L. P., Khosravi A. D., Sheikhi N., et al. (2013). Species spectrum of nontuberculous mycobacteria isolated from suspected tuberculosis patients, identification by multi locus sequence analysis. Infect. Genet. Evol. 20 312–324. 10.1016/j.meegid.2013.08.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Issa R., Abdul H., Hashim S. H., Seradja V. H., Shaili N., Hassan N. A. (2014). High resolution melting analysis for the differentiation of Mycobacterium species. J. Med. Microbiol. 63 1284–1287. 10.1099/jmm.0.072611-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson M. M., Odell J. A. (2014). Nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary infections. J. Thorac. Dis. 6 210–220. 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2013.12.24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent P. T., Kubica G. P. (1985). Public Health Mycobacteriology. A Guide for the Level III Laboratory. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Turhan V., Chokhani L., Stratton C. W., Dunbar S. A., Tang Y. (2009). Identification and differentiation of clinically relevant Mycobacterium Species directly from acid-fast bacillus-positive culture broth. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47 3814–3820. 10.1128/JCM.01534-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim S. Y., Kim B. J., Lee M. K., Kim K. (2008). Development of a real-time PCR-based method for rapid differential identification of Mycobacterium species. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 46 101–106. 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2007.02278.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahon C. R., Lehman D. C., Manuselis G., Jr. (2014). Textbook of Diagnostic Microbiology. St. Louis, MI: Saunders. [Google Scholar]

- Mignard S., Flandrois J. P. (2008). A seven-gene, multilocus, genus-wide approach to the phylogeny of mycobacteria using supertrees. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 58 1432–1441. 10.1099/ijs.0.65658-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mokaddas E., Ahmad S. (2007). Development and evaluation of a multiplex PCR for rapid detection and differentiation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex members from non-tuberculous mycobacteria. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 60 140–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasr Esfahani B., Rezaei Yazdi H., Moghim S., Ghasemian Safaei H., Zarkesh Esfahani H. (2012). Rapid and accurate identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex and common non-tuberculous mycobacteria by multiplex real-time PCR targeting different housekeeping genes. Curr. Microbiol. 65 493–499. 10.1007/s00284-012-0188-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngan G. J., Ng L. M., Jureen R., Lin R. T., Teo J. W. (2011). Development of multiplex PCR assays based on the 16S-23S rRNA internal transcribed spacer for the detection of clinically relevant nontuberculous mycobacteria. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 52 546–554. 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2011.03045.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perng C., Chen H., Chiueh T., Wang W., Huang C., Sun J. (2012). Identification of non-tuberculous mycobacteria by real-time PCR coupled with a high-resolution melting system. J. Med. Microbiol. 61 944–951. 10.1099/jmm.0.042424-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phung T. N., Caruso D., Godreuil S., Keck N., Vallaeys T., Avarre J. C. (2013). Rapid detection and identification of nontuberculous mycobacterial pathogens in fish by using high-resolution melting analysis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79 7837–7845. 10.1128/AEM.00822-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietzka A. T., Indra A., Stöger A., Zeinzinger J., Konrad M., Hasenberger P., et al. (2009). Rapid identification of multidrug resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates by rpoB gene scanning using high-resolution melting curve PCR analysis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 63 1121–1127. 10.1093/jac/dkp124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez M. V., Cowart K. C., Campbell P. J., Morlock G. P., Sikes D., Winchell J. M., et al. (2010). Rapid detection of multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis by use of real-time PCR and high-resolution melt analysis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 48 4003–4009. 10.1128/JCM.00812-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddington K., O’Grady J., Dorai-Raj S., Maher M., Van Soolingen D., Barry T. (2011). Novel multiplex real-time PCR diagnostic assay for identification and differentiation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Mycobacterium canettii, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex strains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 49 651–657. 10.1128/JCM.01426-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson E. T., Samson D., Banaei N. (2009). Rapid identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and nontuberculous mycobacteria by multiplex, real-time PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47 1497–1502. 10.1128/JCM.01868-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahraki A. H., Çavuşoğlu C., Borroni E., Heidarieh P., Koksalan O. K., Cabibbe A. M., et al. (2015). Mycobacterium celeriflavum sp. nov., a rapidly growing scotochromogenic bacterium isolated from clinical specimens. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 65 510–515. 10.1099/ijs.0.064832-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springer B., Stockman L., Teschner K., Roberts G. D., Bottger E. C. (1996). Two-laboratory collaborative study on identification of Mycobacteria: molecular versus phenotypic methods. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34 296–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K., Stecher G., Peterson D., Filipski A., Kumar S. (2013). MEGA6: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30 2725–2729. 10.1093/molbev/mst197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson R., Tolson C., Carter R., Coulter C., Huygens F., Hargreaves M. (2013). Isolation of nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) from household water and shower aerosols in patients with pulmonary disease caused by NTM. J. Clin. Microbiol. 51 3006–3011. 10.1128/JCM.00899-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobler N. E., Pfunder M., Herzog K., Frey J. E., Altwegg M. (2006). Rapid detection and species identification of Mycobacterium spp. using real-time PCR and DNA-Microarray. J. Microbiol. Methods 66 116–124. 10.1016/j.mimet.2005.10.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tortoli E. (2003). Impact of genotypic studies on mycobacterial taxonomy: the new Mycobacteria of the 1990s. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 16 319–354. 10.1128/CMR.16.2.319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tortoli E. (2014). Microbiological features and clinical relevance of new species of the genus Mycobacterium. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 27 727–752. 10.1128/CMR.00035-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Yue J., Han M., Yang J., Zhao Y. (2010). Rapid method for identification of six common species of mycobacteria based on Multiplex SNP analysis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 48 247–250. 10.1128/JCM.01084-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S., Ramachandran P., Rothman R., Hsieh Y. H., Hardick A., Won H., et al. (2009). Rapid identification of biothreat and other clinically relevant bacterial species by use of universal PCR coupled with High-Resolution Melting Analysis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47 2252–2255. 10.1128/JCM.00033-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]