Abstract

Aim:

The aim of the present study was to determine the prevalence and subtype distribution of Blastocystis and its relation with demographic data and symptoms in humans referred to medical centers in Ahvaz 2014-2015.

Background:

Infections with intestinal parasites are one of the most important threats to human health worldwide, especially in tropical and subtropical areas. Blastocystis sp. is a common parasite of humans with a vast variety of non-human hosts. We aimed to study the prevalence and subtypes of Blastocystis sp. in individuals referred to medical laboratories in Ahvaz city, southwest Iran.

Methods:

From September 2014 to September 2015, 618 stool samples were collected from 16 medical laboratories in Ahvaz, and examined using direct wet mount, formalin-ether concentration, a modified version of the Ziehl–Neelsen staining technique, and cultivation in xenic HSr + S medium. Subtypes of positive Blastocysts sp. were obtained using the “barcoding” method. The results were analyzed using SPSS software, version 16, with Chi-square and Fisher’s exact test.

Results:

Totally, 325 (52.6%) of the referred individuals were men and 293 (47.4%) were women. Blastocystis sp. was observed in 146 (23.6%) samples. Co-infections with other intestinal parasites were found in 32 (5.17%) cases. Out of the 146 positive isolates, 20.83%, 20.83% and 58.34% belonged to ST1, ST2, ST3 respectively.

Conclusion:

Blastocystis sp. was quite common in the study population, with a carrier rate corresponding to nearly one in every four individuals. The subtype distribution identified in the present study was largely identical to that reported from other studies in Iran, with ST3 being the most common.

Key Words: Blastocystis, Prevalence, Subtypes. South western Iran

Introduction

Blastocystis is a common anaerobic unicellular eukaryotic parasite of humans with a large variety of non-human hosts with a more or less global distribution. The genus comprises at least 17 ribosomal lineages, the so-called “subtypes”, which are arguably separate species (1). Nine of these subtypes, ST1-ST9, have been detected in humans, with ST1-ST4 being the most common (2). Molecular epidemiological surveys have been carried out in several countries to elucidate the genetic diversity of Blastocystis in different hosts, primarily to identify the level of host specificity, the possibility of zoonotic transmission, and whether certain subtypes could be linked to diseases in humans (1). However, only few countries outside Europe have published data on the genetic diversity of Blastocystis in different hosts (3, 4); Iran is among these countries.

To our knowledge, few Iranian studies have been published to date aiming to elucidate the distribution of Blastocystis subtypes in humans (5-14). These studies used different methodologies for identifying and differentiating Blastocystis subtypes. State-of-the-art subtyping of Blastocystis involves barcoding its original methods to detect Blastocystis subtypes (15). We aimed to expand the knowledge on Blastocystis subtypes existing in humans in southwest of Iran using state-of-the-art subtyping.

Methods

Subjects

Prior to the sample collection, all participants were informed about the procedures. After taking a written consent, a personal information questionnaire was administered to each participant to inquire about age, sex, signs and symptoms, such as abdominal pain, diarrhea, dysentery, vomiting, nausea and constipation. The names of the admitted individuals in the medical laboratories and the results of used methods (Direct slide smear, culture and PCR) were written daily in check-list.

A total of 618 stool samples were collected from individuals referred to 16 medical laboratories of Ahvaz over a period of one year from September 2014 to September 2015.

Parasitological and Statistical Analysis

All 618 fecal samples were examined by direct smear (wet mount with Lugol’s staining), formalin ether concentration technique, Ziehl-Neelsen and trichrome staining in order to enable detection of Cryptosporidium spp. and Entamoeba. sp, respectively, and were also processed by xenic in vitro culture in HSr +S medium [Horse serum, ringer & starch rice (Razi Serum Institute, Iran)] (16). After 5-7 days, sediments of cultures were studied by microscopic examination. Data were analyzed using SPSS software, version 16 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA), with Chi-square and Fisher’s exact test.

DNA extraction and PCR amplification

After 5-7 days of cultivation, DNA of positive cultures were extracted from 200 µLit of the HSr + S culture medium using a commercial DNA extraction kit (Yekta-Tajhiz Azma stool mini kit, Iran) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA was also extracted from stool deemed positive for Blastocystis by microscopy. A 620 bp fragment from 18S rRNA gene was amplified using the DNA barcoding method using RD5 and BhRDr primers as previously described (15). PCR was performed using the Taq DNA Polymerase Master Mix Red (Amplicon, Denmark). The reaction mixture contained 5 µL of distilled water, 7.5 µL master mix, 20 pmoL forward and reverse primers and about 100-500 ng/µL of extracted DNA in a final volume of 15 µL. DNA from a known Blastocystis and a blank containing all PCR reagents but no DNA were included in each set of PCR as positive and negative controls, respectively. PCR products were electrophoresed and visualized with 1.5% agarose gels stained with ethidium bromide.

Sequence analysis and accessions

Ab1 files available from sequencing were manually edited and sequences were queried using the standard nucleotide BLAST algorithm provided by NCBI (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), the Blastocystis subtype [18S rRNA] and Sequence Typing (MLST) database (http://pubmlst.org/blastocystis/), to obtain information on subtype and subtype alleles, whenever applicable (17). The nucleotide sequence of 24 reported data in the present study were submitted to the GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ database under accession number KY312690 to KY312705 and MF072942 to MF072949.

Ethical clearance

All procedures of this study were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Science (SBMU), Iran, before the beginning of the study. All participants were informed about the study procedures and written informed consents were obtained from all of them prior to sample collection.

Results

Out of 618 collected stool samples, 325 (52.6%) were from men and 293 (47.4%) were from women. Samples were randomly collected from individuals referred to the 16 laboratories of Medical centers in 8 regions of Ahvaz and Blastocystis sp was seen in 146 (23.62%) samples (Table 1). Table 2 shows the frequency of positive Blastocystis isolates based on demographic variable of sex, age, and different seasons. In this study, 40.29% of the participants (249/618) were infected by one or more pathogenic or non-pathogenic intestinal parasites. Single parasites were seen in 198 (32.03%) of the specimens, while only 3 (0.48%) of the patients were infected with helminthes. Table 3 shows the prevalence of different intestinal parasites in the collected samples. Co-infections with two or three parasites were found in 32 (5.17%) of positive samples. Frequency of infection was higher in spring and summer and the correlation between season and presence of Blastocystis was significant (P≤0.001). However, no significant correlation was found between sex and infection (Table 2).

Table 1.

Frequency of Blastocystis in 16 medical laboratories in Ahvaz, southwest Iran

| Medical laboratory | No. of Samples | Positive N (Percent) |

Negative N (Percent) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baghaii hospital | 25 | 13 (52.0) | 12 (48.0) |

| Abozar | 43 | 9 (21.0) | 34 (79.0) |

| Pastour | 38 | 6 (15.7) | 32 (84.3) |

| Golestan | 42 | 8 (19.0) | 34 (81.0) |

| Razi | 44 | 9 (20.4) | 35 (79.6) |

| Imam Khomeini | 24 | 5 (21.0) | 19 (79.0) |

| Amir al moemenin | 31 | 11 (35.4) | 20 (64.6) |

| Naft | 54 | 16 (29.6) | 38 (70.4) |

| Shahid Rajaii. | 100 | 22 (22.0) | 78 (78.0) |

| Jihad daneshgahi | 57 | 7 (12.2) | 50 (87.8) |

| DR Jalali | 46 | 11 (24.0) | 35 (76.0) |

| Amir Kabir | 25 | 4 (16.0) | 21 (84.0) |

| Mehr. | 16 | 5 (31.2) | 11 (68.8) |

| DR Naghash | 45 | 7 (15.5) | 38 (84.5) |

| Shahid Karami | 23 | 12 (52.2) | 11 (47.8) |

| Shafa | 5 | 1 (20.0) | 4 (80.0) |

| Total | 618 | 146 (23.62) | 472 (76.38) |

Table 2.

Frequency of Blastocystis sp. isolated from humans based on demographic variables of age, sex and season in subjects referred to the medical laboratories of Ahvaz, southwest Iran

| Variables | Examined individuals (N) | Infected with Blastocystis N (%) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex Male Female |

325 293 |

85 (26.15%) 61 (20.81%) |

0.141 |

| Age group 10≥ 11-25 26-40 41-55 56-70 ≤71 |

131 78 39 87 145 138 |

23 (17.55) 12 (15.4) 16 (41) 22 (25.3) 38 (26.2) 35 (25.3) |

0.023 |

| Season Spring Summer Autumn Winter |

152 150 164 152 |

47 (30.92%) 44 (29.33%) 37 (22.56%) 18 (11.84%) |

0.001 |

Table 3.

Frequency of intestinal parasites from individuals referred to the medicallaboratories, in Ahvaz, Khuzestan province, Southwest Iran (2014-2015)

| Parasite | NO. | % |

| Blastocystissp. | 146 | 23.78 |

| Endolimax nana | 34 | 5.5 |

| Entamoeba coli | 32 | 5.17 |

| Giardia lambelia | 26 | 4.2 |

| Chilomastix mesnelii | 3 | 0.48 |

| Cryptosporidium.spp. | 2 | 0.32 |

| E.histolytica/E.dispar | 2 | 0.32 |

| Dientamoeba fragilis | 1 | 0.16 |

| Total protozoa | 246 | 39.80 |

| Hymenolepis nana | 2 | 0.32 |

| Oxyur | 1 | 0.16 |

| Total parasites | 249* | 40.29* |

Co-infections with two or three parasites were found in 32 (5.17%) of the positive samples

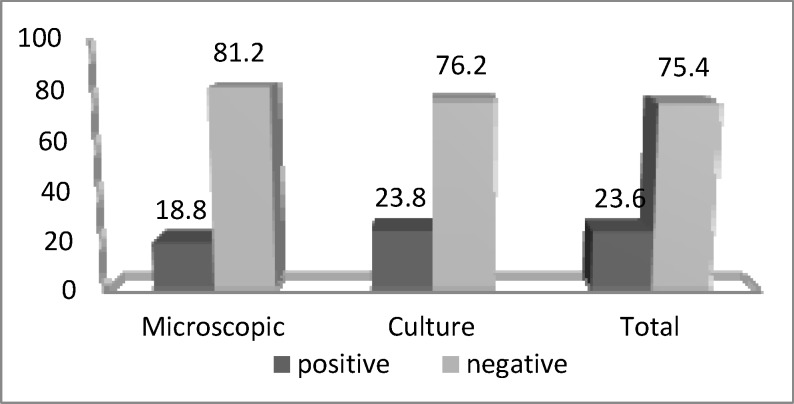

In microscopic study, Blastosistis sp. was seen in 116 (18.77%) samples, while 146 (23.6%) samples grew in culture media (Figure1).

Figure 1.

Frequency of Blastocystis sp. identified by microscopy and culture media from individuals who referred to the medical laboratories in Ahvaz (2014-2015

Among the participants, 256 (41.42%) who were referred to the medical laboratories for checkup had no symptoms and 362 (58.58%) individuals suffered from at least one gastrointestinal symptom. In the symptomatic patients, totally 96 (26.51%) Blastocystis sp were isolated (Table 4). A significant correlation was found between stomach pain, diarrhea and Blastocystis infection (P≤0.01).

Table 4.

Frequency of Blastocystis sp. according to clinical manifestation among individuals who referred to the medical laboratories in Ahvaz (N=618

| Clinical features | Examined individuals (N) | Infected with Blastocystis sp N (%) | P. value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stomach pain | |||

| Yes No |

181 437 |

51 (28.2%) 94 (21.5%) |

0.094 |

| Diarrhea | |||

| Yes No |

61 557 |

22 (36.1%) 123 (22.1%) |

0.014 |

| Dysentery | |||

| Yes No |

6 612 |

3 (50%) 142 (23.2%) |

0.145 |

| Vomiting | |||

| Yes No |

31 586 |

6 (19.4%) 138 (23.5%) |

0.749 |

| Nausea | |||

| Yes No |

90 528 |

28 (31.1%) 117 (22.2%) |

0.086 |

| Constipation | |||

| Yes No |

18 600 |

5 (27.8%) 140 (23.3%) |

0.876 |

| In appetence | |||

| Yes No |

209 409 |

61 (29.2%) 84 (20.5%) |

0.21 |

| Group study | |||

| Patients Asymptomatic individuals Total |

362 256 618 |

96 (26.51%) 50 (19.53%) 146 (23.6%) |

0.017 |

In molecular study, all 146 (23.62%) positive culture isolates were given expected amplicon. From those positive isolates, 24 positive PCR samples were randomly sequenced. Three subtypes, including ST1 (5/20.83%), ST2 (5/20.83%), and ST3 (14/58.34%), were identified. While most patients suffered from abdominal pain and diarrhea, no significant correlation was found between symptoms and subtypes (Table 5).

Table 5.

Frequency of Blastocystis sp. according to gastrointestinal disorders and subtypes among individuals who referred to the medical laboratories in Ahvaz

| P-Value | Subtypes ST1 ST2 * ST3* |

Symptom* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.486 | 4 | 3 | 3 | Stomach pain, Inappetence |

| 0.967 | 1 | 4 | 0 | Stomach pain, Nausea |

| 0.87 | 2 | 1 | 0 | Stomach pain, Constipation |

| 0.758 | 4 | 1 | 1 | Stomach pain, Diarrhea |

| 0.967 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Stomach pain, Vomiting |

| 0.967 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Diarrhea, Vomiting |

| 0.967 | 0 | 0 | 1 | Nausea, Vomiting |

| 0.967 | 3 | 0 | 0 | Inappetence, Constipation |

| 1.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Dysentery |

| 14 | 5 | 5 | Total subtypes | |

Subtypes were seen sometimes in two or more symptoms

Discussion

Blastocystis is the most common parasite that infects the gastrointestinal tract of humans and a wide range of animals, including mammals, birds, reptiles, and arthropods, with a worldwide distribution. The purpose of this study was to improve our understanding of the molecular epidemiology of human Blastocystis, focusing on 618 randomly stool collected from 16 medical laboratory of Ahvaz in one year.

In the present study, the prevalence rate of Blastocystis was 23.62%. In developing countries, Blastocystis has a higher prevalence (30-50%) compared to developed countries (1.5-10%) (17). A noticeable result was obtained (30/20.54% out of 146 positive) in comparison to positive microscopy results when all studied isolates were cultivated in HSr + S medium (16). Therefore, cultivation not only increases positive samples, but the positive culture media is very useful for DNA extraction. Our findings corroborate results from other studies although it is generally assumed that sex is not a risk factor for infection with Blastocystis (18).

We sought to elucidate the distribution of Blastocystis subtypes in humans in southwest of Iran. ST1, ST2 and ST3 were identified, confirming the trend observed in other studies carried out in countries outside Europe. Hence, no cases of other subtypes were found. ST4 is common in humans in Europe, but appears to be rare in countries outside Europe (19). In this study, ST3 was the most prevalent (58.34%), as the pre-dominant subtype in most parts of the world such as Japan, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Germany, Singapore, Greece, Turkey, Makkah, Thailand and Iran (2, 5, 7-9, 10, 11, 17, 19-24). It is believed that ST3 is the main human subtype and has no relation to geographic area (25-27). Moosavi and colleagues (2012) also identified ST1, ST2, and ST3 in humans; however, these authors also found a few cases of ST7 (5), which has been found sporadically in humans in other studies (4, 26, 27). ST5 is the subtype seen in cattle and pigs (28), and human infection with this subtype has been rarely reported (25, 28). Since Blastocystis is a zoonotic parasite, the impact of geographical terms on infection should be considered.

There has been debate on the pathogenicity of Blastocystis. A few studies found that expatriates with traveler’s diarrhea had a high prevalence of Blastocystis, whereas some studies found that 25%–75% of those with Blastocystis have a history of recent foreign travel (29-32). Some studies suggest an association between the parasite and symptoms (32-34), while others do not (35, 36).

Blastocystis can be isolated from individuals with gastrointestinal and extra-intestinal symptoms (e.g. diarrhea, nausea, abdominal pain, bloating, vomiting or anorexia) and asymptomatic individuals with an almost equal prevalence (32). In some studies, higher prevalence can be found in asymptomatic compared to symptomatic individuals. Many researchers classify Blastocystis as a commensal or opportunistic pathogen (37). In this study, we compared clinical signs and infection with Blastocystis. A significant correlation was found between Blastocystis infection with diarrhea and stomach pain. However, no significant correlation was observed between different subtype and clinical signs. Scanlan suggested that studies about the clinical relevance of different Blastocystis subtypes, their virulence, and the zoonotic potential within and between humans and animals can fill the gaps of incomplete knowledge about the pathogenicity of Blastocystis (38).

Clinical symptoms are diverse, ranging from acute diarrhea to mild chronic abdominal pain. Although the parasite is noninvasive, it might complicate the pathogenicity of other invasive pathogens. The diversity in pathogenesis between variant parasite subtypes is suspected to be responsible for diverse clinical symptoms and presentations of Blastocystis infections (39).

The results of the present study implicated that more than one third of referred individuals (40.29%) were infected with one or more intestinal parasites. Our findings showed that protozoa infections (39.80%) were remarkably more common compared to helminthes infections (0.49%) and except Blastocystis, Endolimax nana, Entamoeba coli and Giardia lamblia were the most frequently detected protozoan parasites.

One of the limitations of our study was that PCR was not performed on DNAs extracted from negative samples by the two screening methods, both of which have reduced sensitivity compared with PCR (37, 40). To this end, it should be emphasized that the numbers of positive samples identified in the current study should by no means be interpreted as prevalence figures. We acknowledge the limitations related to methods used for Blastocystis screening (microscopy and culture), one of which is related to the possibility that for instance avian Blastocystis sp isolates may not establish in cultures kept at 37oC.

Acknowledgment

This work was part of the PhD thesis of Roya Salehi Kahyesh which was supported financially by Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences (Grant No. code: 6443). We thank the scientists and personnel of Medical Parasitology and Mycology department in Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, especially Dr. SJ Seyyed Tabaei, Mrs. N. Taghipour. Mr. A. Rostami, and Mr. H. Kiani for their helpful comments and collaborations.

Conflict of interests

The authors do not have any conflict of interest to report with for this manuscript.

References

- 1.Alfellani MA, Stensvold CR, Vidal-Lapiedra A, Uche Onuoha ES, Fagbenro-Beyioku AF, Clark CG. Variable geographic distribution of Blastocystis subtypes and its potential implications. Acta Tropica. 2013;126:11–18. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2012.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Popruk S, Pintong AR, Radomyos P. Diversity of Blastocystis Subtypes in Humans. J Trop Med Parasitol. 2013;36:88–97. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abdulsalam AM, Ithoi I, Al-Mekhlafi HM, Ahmed A, Johar , Surin J. Subtype Distribution of Blastocystis Isolates in Sebha, Libya. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e84372. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.El Safadi D, Meloni D, Poirier P, Osman M, Cian A, Gaayeb L, et al. Molecular Epidemiology of Blastocystis in Lebanon and Correlation between Subtype 1 and Gastrointestinal Symptoms. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2013;88:1203–6. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.12-0777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moosavi A, Haghighi A, Mojarad EN, Zayeri F, Alebouyeh M, Khazan H, et al. Genetic variability of Blastocystis sp isolated from symptomatic and asymptomatic individuals in Iran. Parasitol Res. 2012;111:2311–15. doi: 10.1007/s00436-012-3085-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Badparva E, Fallahi Sh, Arab-Mazar Z. Blastocystis: Emerging Protozoan Parasite with High Prevalence in Iran. Novelty in Biomedicine. 2015;3:214–21. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Badparva E, Sadraee J, Kheirandish F, Frozandeh M. Genetic Diversity of Human Blastocystis Isolates in Khorramabad, Central Iran. Iran J Parasitol. 2014;9:44–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sardarian K, Hajilooi M, Maghsood A, Moghimbeigi A, Alikhani MA. Study of The Genetic Variability of Blastocystis hominis Isolates in Hamadan, West of Iran. Jundishapur J Microbiol. 2012;5:555–9. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khoshnood S, Rafiei A, Saki J, Alizadeh K. Prevalence and genotype characterization of Blastocystis hominis among the baghmalek people in southwestern Iran in 2013-2014. Jundishapur J Microbiol. 2015;8:e23930. doi: 10.5812/jjm.23930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Badparva E, Ezatpour , Mahmoudvand H, Behzadifar M, Behzadifar M, Kheirandish K. Prevalence and Genotype Analysis of Blastocystis hominis in Iran: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Arch Clin Infect Dis. 2016:e36648. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Azizian M, Basati G, Abangah G, Mahmoudi MR, Mirzaei A. Contribution of Blastocystis hominis subtypes and associated inflammatory factors in development of irritable bowel syndrome. Parasitology Research. 2016;115:2003–9. doi: 10.1007/s00436-016-4942-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Motazedian H, Ghasemi H, Sadjjadi SM. Genomic diversity of Blastocystis hominis from patients in southern Iran. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2008;102:85–8. doi: 10.1179/136485908X252197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alinaghizade A, Mirjalali H, Mohebali M, Stensvold CR, Rezaeian M. Inter- and intra-subtype variation of Blastocystis subtypes isolated from diarrheic and non-diarrheic patients in Iran. Infect Genet Evol. 2017;50:77–82. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2017.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jalallou N, Iravani S, Rezaeian M, Alinaghizadeh A, Mirjalali H. Subtypes Distribution and Frequency of Blastocystis sp Isolated from Diarrheic and Non-diarrheic Patients. Iranian Journal of Parasitology. 2017;12:63–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stephanie M, Scicluna , Blessing Tawari C, Graham Clark. DNA Barcoding of Blastocystis. Protist. 2006;157:77–85. doi: 10.1016/j.protis.2005.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dobell C, Laidlaw PP. On the cultivation of Entamoeba histolytica and some other entozoic amoebae. Parasitology. 1926;18:283–318. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beyhan YE, Yilmaz H, Cengiz ZT, Ekici A. Clinical significance and prevalence of Blastocystis hominis in Van, Turkey. Saudi Med J. 2015;36:1118–21. doi: 10.15537/smj.2015.9.12444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stenzel DJ, Boreham PF. Blastocystis hominis revisited. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1996;9:563–84. doi: 10.1128/cmr.9.4.563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mohamed R, El-Bali MA, Mohamed A, Abdel-Fatah M, EL-Malky MA, Mowafy N, et al. Subtyping of Blastocystis sp isolated from symptomatic and asymptomatic individuals in Makkah, Saudi Arabia. Parasites & Vectors. 2017;10:174. doi: 10.1186/s13071-017-2114-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Popruk S, Udonsom R, Koompapong R, Mahittikorn A, Kusolsuk T, Ruangsittichai J, et al. Subtype Distribution of Blastocystis in Thai-Myanmar Border, Thailand. Korean J Parasitol. 2015;53:13–19. doi: 10.3347/kjp.2015.53.1.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Devi Ragavan N, Govind SK, Chye TT, Mahadeva S. Phenotypic variation in Blastocystis sp ST3. Parasites & Vectors. 2014;7:404. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-7-404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Forsell J. Genetic subtypes in unicellular intestinal parasites with special focus on Blastocystis. Umeå University Medical Dissertations, New Series No 1889; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Albrecht H, Stellbrink HJ, Koperski K, Greten H. Blastocystis hominis in human immunodeficiency virus-related diarrhea. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1995;30:909–14. doi: 10.3109/00365529509101600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roberts T, Stark D, Harkness J, Ellis J. Update on the Molecular Epidemiology and Diagnostic Tools for Blastocystis sp. Medical Microbiology & Diagnosis. 2014;3:1. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stensvold CR, Alfellani M, Clark CG. Levels of genetic diversity vary dramatically between Blastocystis subtypes. Infection, Genetics and Evolution. 2012;12:263–73. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2011.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arisue N, Hashimoto T, Yoshikawa H, Nakamura Y, Nakamura G, Nakamura F, et al. Phylogenetic Position of Blastocystis hominis and of Stramenopiles Inferred from Multiple Molecular Sequence Data. Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology. 2002;49:42–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.2002.tb00339.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clark CG, van der Giezen M, Alfellani MA, Stensvold CR. Recent development in Blastocystis research. Adv Parasitol. 2013;82:1–32. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-407706-5.00001-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Santín M, Gómez-Muñoz MT, Solano-Aguilar G, Fayer R. Development of a new PCR protocol to detect and subtype Blastocystis spp from humans and animals. Parasitol Res. 2011;109:205–12. doi: 10.1007/s00436-010-2244-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Andersen LO, Stensvold CR. Blastocystis in Health and Disease: Are We Moving from a Clinical to a Public Health Perspective? J Clin Microbiol. 2016;54:524–8. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02520-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Babcock D, Houston R, Kumaki D, Shlim D. Blastocystis hominis in Kathmandu, Nepal. N Engl J Med. 1985;313:1419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keystone JS. Blastocystis hominis and traveler’s diarrhea. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21:102–3. doi: 10.1093/clinids/21.1.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tan KS. New insights on classification, identification and clinical relevance of Blastocystis spp. Clin Microb Rev. 2008;21:639–65. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00022-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yunus E B, Hasan Y, ZeynepT , Abdurrahman E. Clinical significance and prevalence of Blastocystis hominis in Van, Turkey. Saudi Med J. 2015;36:1118–21. doi: 10.15537/smj.2015.9.12444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Clark CG. Extensive genetic diversity in Blastocystis hominis. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1997;87:79–83. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(97)00046-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Udkow MP, Markell EK. Blastocystis hominis: prevalence in asymptomatic versus symptomatic hosts. J Infect Dis. 1993;168:242–4. doi: 10.1093/infdis/168.1.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grossman I, Weiss LM, Simon D, Tanowitz HB, Wittner M. Blastocystis hominis in hospital employees. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992;87:729–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stensvold CR, Nielsen HV, Mølbak K, Smith HV. Pursuing the clinical significance of Blastocystis – diagnostic limitations. Trends Parasitol. 2009;25:23–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2008.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scanlan PD. Blastocystis: past pitfalls and future perspectives. Trends Parasitol. 2012;28:327–34. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2012.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mehlhorn H, Tan KSW, Yoshikawa H. Blastocystis: Pathogen or Passenger An Evaluation of 101 Years of Research. Heidelberg: Springer; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang W, Bielefeldt-Ohmann H, Traub RJ, Cuttell L, Owen H. Location and Pathogenic Potential of Blastocystis in the Porcine Intestine. Plos one. 2014;9:e103962. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]