ABSTRACT

Upstream binding factor (UBF) is a member of the high-mobility group (HMG) box protein family, characterized by multiple HMG boxes and a C-terminal acidic region (AR). UBF is an essential transcription factor for rRNA genes and mediates the formation of transcriptionally active chromatin in the nucleolus. However, it remains unknown how UBF is specifically localized to the nucleolus. Here, we examined the molecular mechanisms that localize UBF to the nucleolus. We found that the first HMG box (HMG box 1), the linker region (LR), and the AR cooperatively regulate the nucleolar localization of UBF1. We demonstrated that the AR intramolecularly associates with and attenuates the DNA binding activity of HMG boxes and confers the structured DNA preference to HMG box 1. In contrast, the LR was found to serve as a nuclear localization signal and compete with HMG boxes to bind the AR, permitting nucleolar localization of UBF1. The LR sequence binds DNA and assists the stable chromatin binding of UBF. We also showed that the phosphorylation status of the AR does not clearly affect the localization of UBF1. Our results strongly suggest that associations of the AR with HMG boxes and the LR regulate UBF nucleolar localization.

KEYWORDS: HMG box, nucleolus, ribosome biogenesis, transcription factors

INTRODUCTION

Ribosome biogenesis underlies cell growth and proliferation (1). The primary transcription of precursor rRNA is mediated by RNA polymerase I (Pol I) in the nucleolus (2). Nucleoli are formed at specific chromosome loci that contain rRNA gene repeats called nucleolar organizer regions (NORs). Diploid human cells contain about 400 copies of tandemly repeated rRNA genes that are distributed among the acrocentric chromosomes. Only half of rRNA genes are active, and the numbers of active and inactive genes are likely to determine cell growth. Active NORs have been defined by upstream binding factor (UBF), which is a Pol I transcription factor. UBF is highly concentrated in the rRNA gene repeats (3–6). Ectopic UBF recruits the Pol I machineries to remodel chromatin in a way similar to that of NORs (7–9). Furthermore, UBF expression determines the number of transcriptionally active rRNA genes (10). These observations strongly suggest that UBF plays a fundamental role in defining active NORs.

UBF is a member of the high-mobility group (HMG) box protein family, which contains conserved HMG box DNA binding domains (11) and a C-terminal acidic region (AR). The C-terminal AR of UBF mediates the recruitment of SL1 complex, which is required for Pol I-mediated transcription at the rRNA gene promoter (12, 13). The AR also may be responsible for modulating the DNA binding activity of HMG boxes (14, 15). UBF has five or six HMG boxes. Mammalian UBF exists in two forms: UBF1, with a molecular size of ∼97 kDa, and UBF2, with a size of ∼94 kDa. UBF2 is an alternative splicing product lacking 37 amino acids in the second HMG box (HMG box 2) (16). The first HMG box (HMG box 1) is sufficient for the association of UBF with DNA, and the other HMG boxes enhance this association (1, 12, 17). No consensus binding sequence of UBF has been reported, although it exhibits a preference for GC-rich sequences (18). UBF localizes to the nucleolus and preferentially associates with rRNA genes. Previous studies have suggested that the nucleolar localization of UBF depends on the N-terminal dimerization domain, HMG box 1, and the C-terminal AR (19). In addition, a 24-amino-acid sequence between HMG box 5 and the AR was found to be required for the nuclear localization of Xenopus UBF1 (20). However, it is currently not well understood how the HMG boxes and AR mediate the nucleolar localization of UBF.

Given the essential function of UBF in rRNA transcription and nucleolar chromatin organization, we investigated the molecular mechanism by which UBF is localized to the nucleolus. We demonstrated that HMG box 1, the linker region between the HMG boxes and AR, and the AR cooperatively regulate the nucleolar localization of UBF. In addition, the other HMG boxes help to determine the stable association of UBF with DNA. We propose that internal associations of AR regulate the nuclear and nucleolar localization of UBF.

RESULTS

Functions of the UBF acidic region in nucleolar localization.

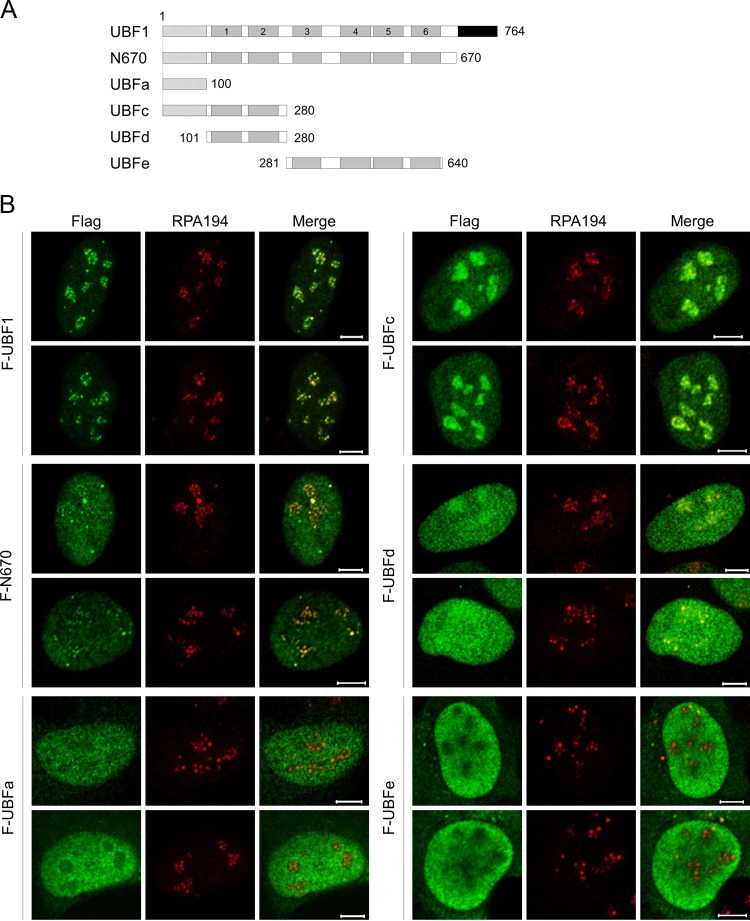

To clarify the mechanism by which UBF localizes to the nucleolus, we first examined the localization of a series of UBF mutants (Fig. 1A). Flag-tagged UBF proteins were expressed in U2OS cells, and their localization was examined by immunofluorescence analyses (Fig. 1B). Full-length UBF was localized to the nucleoli and colocalized with the RNA polymerase I subunit (RPA194). Upon deletion of the AR, the protein (N670; amino acids 1 to 670) was distributed throughout the nucleus with slight accumulation in the nucleoli. The mutant protein UBFc (amino acids 1 to 280), lacking the AR and HMG boxes 3, 4, 5, and 6, showed nucleolar localization, suggesting that HMG boxes 3 to 6 play an inhibitory role in the nucleolar localization of UBF. Consistent with this, the HMG boxes 3 to 6 (UBFe; amino acids 281 to 640) did not show any preference for the nucleoli. It also should be noted that UBFc localized not only to the sites where Pol I had accumulated but also to the periphery of the nucleoli, suggesting that UBFc binds both DNA and RNA accumulated in the periphery of the nucleolus. In addition, we found that HMG boxes 1 and 2 alone (UBFd; amino acids 101 to 280) were not sufficient for the efficient nucleolar localization of UBF, although the N-terminal region (UBFa; amino acids 1 to 100) did not show nucleolar localization. In addition, UBF2 lacking a part of HMG box 2 localizes to the nucleoli, as does UBF1 (see Fig. 6B), indicating that HMG box 2 is dispensable for the nucleolar localization of UBF. From these results, it is suggested that the N-terminal region, HMG box 1, and AR of UBF are required for the efficient nucleolar localization of UBF, whereas HMG boxes 3 to 6 are inhibitory for UBF nucleolar localization.

FIG 1.

Multiple regions are required for efficient nucleolar localization of UBF. (A) Schematic diagram of truncated UBF mutants. The dotted, gray, and black boxes represent the dimerization domain, HMG boxes (1 to 6), and acidic region (AR), respectively. The numbers shown represent the positions of amino acids. (B) Immunofluorescence analysis. U2OS cells transiently expressing F-UBF1, -N670, -UBFc, -UBFa, -UBFd, and -UBFe were subjected to immunofluorescence assays 16 h after transfection with anti-Flag and anti-RPA194 (red) antibodies as indicated at the top of the panels. Bars indicate 5 μm.

FIG 6.

Functions of the linker region in nuclear localization and the DNA binding activity of UBF1. (A) Schematic diagram of cloned UBF proteins. (B) Localization of the UBF proteins. U2OS cells transiently expressing Flag-UBF1, -UBF2, -UBFm1, or -UBFm2 were subjected to immunofluorescence assays with anti-Flag (green) and anti-NPM1 (red) antibodies as indicated at the top. (C) Amino acid sequences lacking in human UBFm2 and corresponding sequences of mouse and Xenopus UBF (UniProtKB accession numbers P17480, P25976, and P25980). (D) Localization of Flag-tagged UBFm2 in the presence of leptomycin B (LMB). U2OS cells transiently expressing Flag-UBFm2 were incubated in the absence or presence of 100 nM LMB for 3 h, and then immunofluorescence assays were performed with anti-Flag (green) and anti-NF-κB p65 (red) antibodies as indicated. (E) Localization of GFP and GFP fused with the 24-amino-acid sequence deleted in UBFm2 (GFP-LR). In panels C to E, DNA was counterstained with TO-PRO-3 iodide (blue). Bars indicate 5 μm. (F) Purified Flag-UBF1 and -UBFm2. Each protein (300 ng) was separated by SDS-PAGE and visualized by CBB staining. Positions of molecular size markers are shown at the left. (G) DNA binding activity of UBF1 and UBFm2. The 154-bp DNA fragment (0.03 μM) incubated with Flag-UBF1 or -UBFm2 (0, 0.09, 0.18, 0.27, 0.36, and 0.45 μM) was separated by native PAGE and visualized by GelRed staining. The position of the free DNA fragment is shown at the left.

The N-terminal region of UBF was shown to be required for dimer formation to enhance the DNA binding activity of UBF. In fact, the DNA binding activity of UBFc (amino acids 1 to 280) was much higher than that of UBFd (amino acids 101 to 280) (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). This different affinity for DNA may explain the specific nucleolar localization of UBF, although it is currently not known how the HMG boxes 1 and 2 specifically recognize the nucleolar chromatin.

The AR has already been implicated in the nucleolar localization of UBF (19), although its function in the nucleolar localization of UBF is elusive. Our results demonstrated that the N670 protein lacking the AR was partially colocalized with RPA194. It was possible that N670 was localized to the nucleolus by forming a dimer with endogenous UBF. To test this possibility, the endogenous UBF protein was depleted by short interfering RNA (siRNA) and the exogenous Flag-UBF proteins were expressed (Fig. S3). Upon treatment with siRNA for UBF, the signal for UBF was decreased and almost undetectable. The localization of the nucleolar protein DKC1 was also changed upon depletion of UBF1 (Fig. S3B). We demonstrated that exogenous Flag-N670 localized to both the nucleoplasm and the nucleolus independent of the expression level of endogenous UBF1 (Fig. S3C). In addition, the N-terminal dimer formation domain alone (UBFa; amino acids 1 to 100) was not accumulated to the nucleoli (Fig. 1B). Thus, it is unlikely that the nucleolar accumulation of N670 depends on the endogenous protein. These results indicate that AR is not essential but is required for efficient nucleolar localization of UBF.

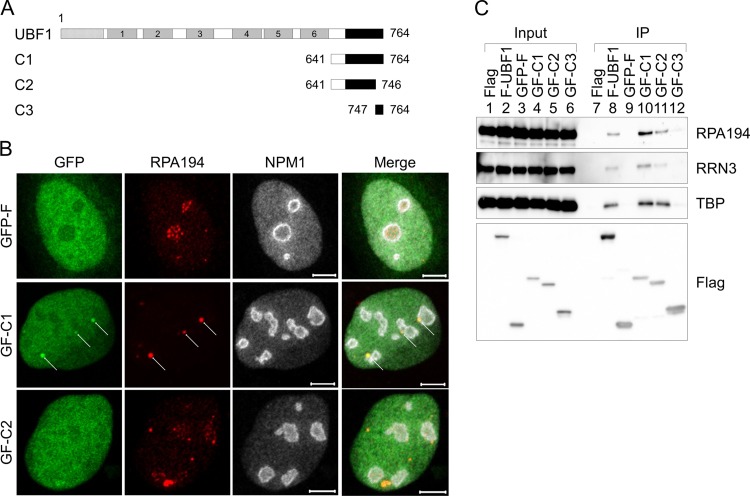

To test whether AR is sufficient for localization to the nucleolus, we examined the localization of green fluorescent protein (GFP)-Flag (GF)-tagged AR (C1; amino acids 641 to 764) (Fig. 2A and B). Interestingly, we found that GF-C1 was diffused throughout the nucleus but showed weak accumulation in the nucleolus and colocalized with RPA194. The nucleolar accumulation and colocalization with RPA194 were decreased when the C-terminal 19 amino acids of AR were deleted (C2). We noted that the localization pattern of RPA194 was slightly changed upon the expression of GF-C1 (foci in the nucleoli were decreased), although the nucleolar localization of NPM1 was not clearly changed by GFP-Flag, GF-C1, and GF-C2 (Fig. 2B). AR was shown to associate with the SL1 complex to recruit it to the nucleoli (7, 8, 13, 21–23); therefore, we investigated whether this interaction mediates the nucleolar localization of UBF1. TBP (a component of the SL1 complex), RRN3 (a factor that mediates the association between the SL1 complex and Pol I) (24), and RPA194 were coimmunoprecipitated with F-UBF1, GF-C1, and GF-C2 but not with GF-C3 (amino acids 747 to 764) (Fig. 2C). Consistent with the low accumulation ability to the Pol I site of GF-C2, the association of GF-C2 with the Pol I machineries was lower than that of GF-C1 (Fig. 2C, lanes 10 and 11). These results suggest that the nucleolar localization of GF-C1 and -C2 is mediated by its interaction with the Pol I machineries, although the efficiency of GF-C1 nucleolar accumulation was low.

FIG 2.

AR of UBF shows potential ability to localize to the nucleoli. (A) Schematic diagram of truncated UBF1 mutants. (B) Localization of GFP-Flag (GF)-tagged AR mutants C1 and C2. U2OS cells transiently expressing GF, GF-C1, or GF-C2 were subjected to immunofluorescence assays 16 h after transfection with anti-RPA194 (red) and anti-B23 (NPM1) (white) antibodies as indicated at the top. Arrows represent the accumulated foci. Bars indicate 5 μm. (C) Association of the AR with the Pol I machineries. Flag (F), F-UBF1, GF, GF-C1, GF-C2, or GF-C3 was transiently expressed in 293T cells, and immunoprecipitation (IP) assays were performed with anti-Flag M2 affinity gel. Input (lanes 1 to 6) and immunoprecipitated (lanes 7 to 12) proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and subjected to Western blotting with anti-RPA194, -RRN3, -TBP, and -Flag antibodies.

AR binds to HMG boxes to attenuate its DNA binding activity.

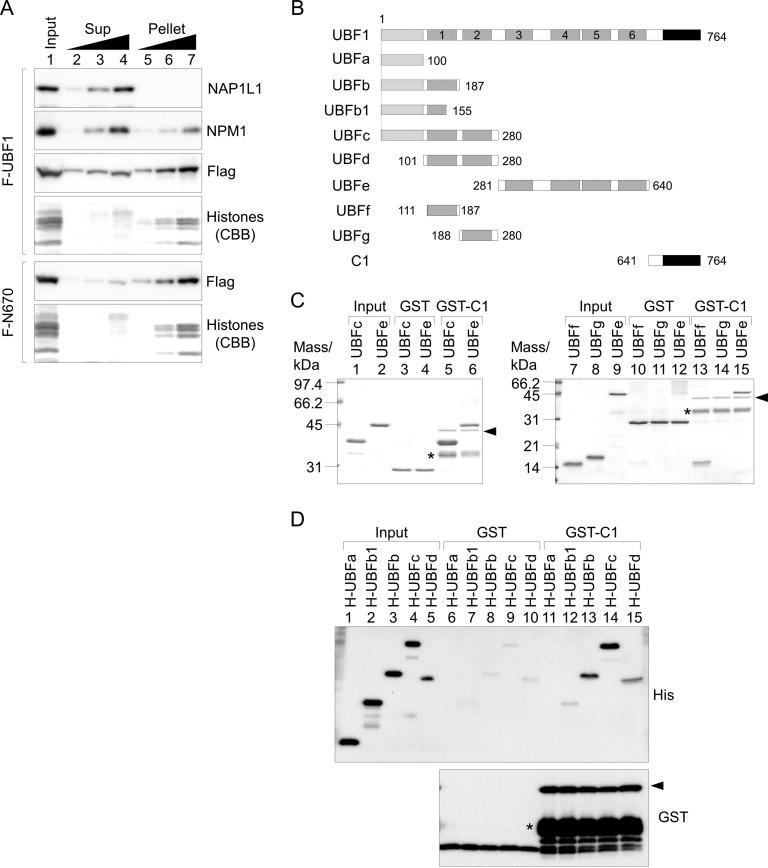

It was previously reported that the AR decreases DNA binding activity of the HMG boxes (14, 15). Thus, we speculated that UBF nucleolar localization requires AR-mediated suppression of nonspecific DNA binding of HMG boxes. To test whether the AR affects the association between UBF and DNA/chromatin, we performed subcellular fractionation assays using HeLa cells expressing Flag-UBF1 or Flag-N670 (Fig. 3A). Cells were treated with detergent and separated into supernatant (Sup) and pellet fractions. A cytoplasmic protein, nucleosome assembly protein 1-like 1 (NAP1L1), was detected in the Sup fraction, a nucleolar protein, NPM1, was detected in the Sup and pellet fractions, and core histones were found only in the pellet fraction. Flag-UBF1 was equally fractionated into the Sup and pellet fractions, whereas Flag-N670 was mainly fractionated into the pellet fraction. These results supported the idea that binding of UBF to DNA is regulated by AR.

FIG 3.

AR affects the localization of UBF by its association with HMG boxes. (A) Subcellular fractionation assay. HeLa cells transiently expressing Flag-UBF1 or -N670 were subjected to subcellular fractionation assays as described in Materials and Methods. Input (lane 1; 3 × 104 cells), supernatant (Sup), and pellet fractions (lanes 2 to 4 and 5 to 7; 0.6 × 104, 1.5 × 104, and 3 × 104 cells) were separated by SDS-PAGE and subjected to Western blotting with anti-Flag, anti-NAP1L1, and anti-NPM1 antibodies. Core histones were visualized by CBB staining. Two independent experiments showed similar results. (B) Schematic diagram of truncated UBF1 mutants used in panels C and D. The numbers shown represent the positions of amino acids. (C and D) Association of AR with the UBF mutants. GST, GST-C1, and His-tagged UBF mutants were expressed in E. coli and purified, and GST pulldown assays were performed using the purified proteins. Input and pulldown proteins with GST or GST-C1, as indicated, were separated by SDS-PAGE and subjected to CBB staining (C) or Western blotting with anti-His and -GST antibodies (top and bottom, respectively) (D). Positions of the full-length GST-C1 are indicated by arrowheads, and the bands shown by asterisks likely are premature translation termination products.

HMG boxes are major DNA binding domains of UBF; therefore, we explored the interaction between the AR and HMG boxes by glutathione S-transferase (GST) pulldown assays using recombinant proteins. GST or GST-tagged C1 (amino acids 641 to 764) was incubated with His-tagged UBF1 mutants (Fig. 3B) and subjected to pulldown assays (Fig. 3C and D). His-UBFb, -UBFc, -UBFd, -UBFe, and -UBFf (amino acids 1 to 187, 1 to 280, 101 to 280, 281 to 640, and 111 to 187, respectively), but not His-UBFa and -UBFg (amino acids 1 to 100 and 188 to 280, respectively), were efficiently pulled down with GST-C1, suggesting that AR associates with HMG box 1 and HMG boxes 3 to 6. Considering the different associations of UBFb (amino acids 1 to 187) and UBFb1 (amino acids 1 to 155) with AR (Fig. 3D, lanes 12 and 13), it is likely that AR associates with the properly structured HMG box 1.

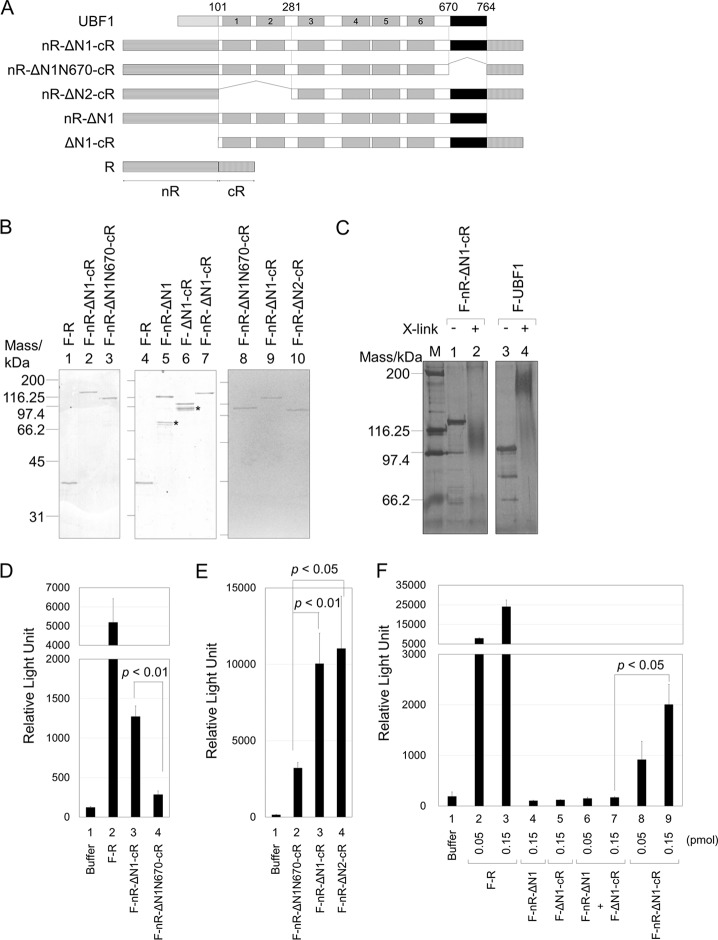

We next examined whether the AR associates with HMG boxes inter- or intramolecularly by the split Renilla luciferase complementation assay (Fig. 4). In this assay, the N- and C-terminal Renilla luciferase fragments (amino acids 1 to 229 [nR] and amino acids 230 to 311 [cR], respectively) were independently expressed, and luciferase activity was detected only when the two fragments were in close proximity (25). To detect the intramolecular interaction between the AR and HMG box 1, the nR and cR fragments were fused to the N terminus of HMG box 1 (nR-ΔN1-cR) or HMG box 3 (nR-ΔN2-cR) and the C terminus of the AR, respectively, and the fusion proteins were purified (Fig. 4A and B). We also expressed UBF protein lacking AR fused with nR and cR (nR-ΔN1N670-cR) to examine the effect of AR. We first verified that the UBF proteins did not form dimers when the N-terminal region (amino acids 1 to 100) was removed by chemical cross-link assay (Fig. 4C). When wild-type UBF1 was cross-linked by glutaraldehyde, the band at about 180 kDa was clearly detected (lanes 3 and 4). However, the band corresponding to the dimer or oligomer was hardly detected when the N-terminal region was removed (lanes 1 and 2), ensuring that the N-terminal region is required for oligomer formation of UBF. Luminescence was clearly detected when purified full-length luciferase was examined (Fig. 4D, lane 2). Interestingly, the nR-ΔN1-cR protein also showed clear luminescence (lane 3), although the intensity was much lower than that of full-length Renilla luciferase. Importantly, we also found that luminescence of the nR-ΔN1N670-cR protein lacking AR was significantly lower than that of nR-ΔN1-cR (lanes 3 and 4). We also demonstrated that nR-ΔN1-cR and nR-ΔN2-cR showed similar luciferase activity (Fig. 4E). These results supported our conclusion that the AR associates with HMG boxes. We were not able to discriminate whether the interaction between the AR and HMG boxes occurs intermolecularly or intramolecularly. To clarify this point, the N- or C-terminal region of ΔN1 (amino acids 101 to 764) was fused with either nR or cR (Fig. 4A). The two proteins were mixed and the luciferase activity was examined. Neither nR-ΔN1 nor ΔN1-cR alone showed luminescence, and luciferase activity was not detected even when the two proteins were mixed (Fig. 4F, lanes 4 to 7). In contrast, intensity was detected in a dose-dependent manner when the nR-ΔN1-cR protein was examined (lanes 8 and 9). These results strongly suggest that the AR and HMG boxes associate with each other intramolecularly.

FIG 4.

Associations between AR and HMG boxes occur intramolecularly. (A) Schematic diagram of the fusion proteins of the split Renilla luciferase fragments and UBF mutants. The boxes with horizontal and vertical lines represent N- and C-terminal Renilla luciferase (nR and cR, amino acids 1 to 229 and 230 to 311, respectively). The numbers shown represent the positions of amino acids. (B) Purified proteins. The fusion proteins purified from 293T cells (50 ng) were separated by SDS-PAGE and visualized by CBB staining. Positions of molecular size markers are shown at the left. Asterisks indicate contaminated or truncated proteins. (C) Chemical cross-link assay. F-nR-ΔN1-cR and F-UBF1, left untreated or treated with 0.05% glutaraldehyde, were separated by 7.5% SDS-PAGE and visualized with silver staining. (D and E) Detection of the interaction between AR and HMG boxes by the split Renilla luciferase complementation assay. Buffer alone, F-R, F-nR-ΔN1-cR, F-nR-ΔN1N670-cR, or F-nR-ΔN2-cR (0.15 and 0.3 pmol for D and E, respectively), as indicated, was mixed with the substrate of Renilla luciferase and the luminescence intensity was measured. (F) Inter- or intramolecular interaction between the AR and HMG boxes. Buffer alone, F-R, F-nR-ΔN1, F-ΔN1-cR, or F-nR-ΔN1-cR (0.05 or 0.15 pmol, as indicated) was mixed with the substrate of Renilla luciferase and luminescence intensity was measured. Equal amounts of F-nR-ΔN1 and F-ΔN1-cR (0.05 and 0.15 pmol of each protein) were mixed and luminescence intensity was measured (lanes 6 and 7). Error bars in panels D to F indicate ± standard deviations (SD) (n = 3). Statistical analyses were performed by two-tailed Student's t test.

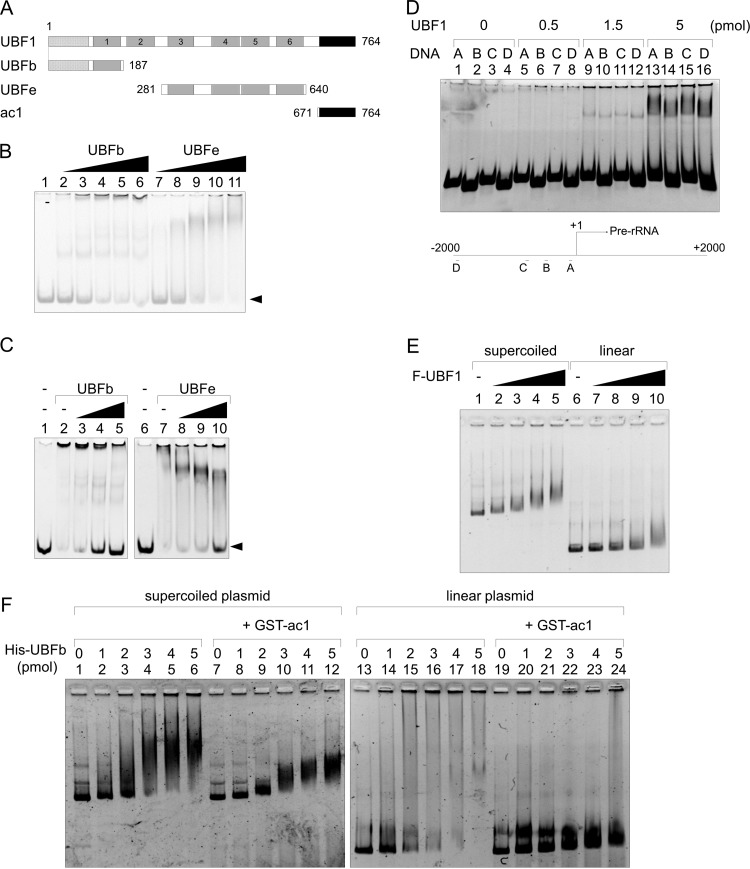

UBF HMG box 1 was shown to be necessary and sufficient for binding to the human rRNA gene promoter (1, 12). Thus, we examined whether AR modulates the affinity of HMG box 1 (UBFb; amino acids 1 to 187) binding to DNA. In parallel, we also examined the effect of AR on the DNA binding activity of HMG boxes 3 to 6 (UBFe; amino acids 281 to 640) (Fig. 5A). GST-UBFb and -UBFe nonspecifically bound to linear DNA with similar affinity (Fig. 5B). Interestingly, we demonstrated that GST-ac1 (amino acids 671 to 764) inhibited the binding of both UBFb and UBFe to DNA (Fig. 5C, lanes 3 to 5 and 8 to 10). These results indicate that the AR of UBF1 binds to HMG boxes and attenuates their DNA binding.

FIG 5.

AR attenuates the DNA binding activity of HMG boxes and confers DNA structure preference to HMG box 1. (A) Schematic diagram of UBF1 mutants. (B) DNA binding activity of His-tagged UBFb and UBFe. The 154-bp DNA fragment (0.04 μM) mixed and incubated alone or with increasing amounts of His-tagged proteins (0, 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, and 0.4 μM) was separated by native PAGE and visualized by GelRed staining. (C) DNA binding activities of UBFb and UBFe are attenuated by the AR. His-UBFb (lanes 2 to 5) or His-UBFe (lanes 7 to 10) (0.3 μM) incubated without or with GST-ac1 (0.3, 1, and 3 μM) was mixed with 154 bp DNA (0.04 μM) and separated by native PAGE, and DNA was visualized by GelRed staining. Positions of free DNA are indicated by arrowheads. (D) UBF1 binds linear DNA fragments without specificity. Increasing amounts of Flag-UBF1 purified from 293T cells were mixed with 0.05 μM DNA fragments (150, 129, 150, and 124 bp, for panels A to D, respectively) harboring the rRNA gene promoter region and separated by native PAGE. DNA was visualized by GelRed staining. Positions of the DNA fragments relative to the transcription start site of rRNA (+1) are schematically shown at the bottom. The positions of the DNA are also shown in Fig. S4A in the supplemental material. (E) UBF1 preferentially binds to structured DNA. Supercoiled or linear pBluescript SKII plasmid (100 ng, 0.05 pmol) mixed with increasing amounts of Flag-UBF1 (0, 3, 6, 12, and 18 pmol for lanes 1 to 5 and 6 to 10) was separated by 0.8% agarose gel and visualized with GelRed staining. (F) AR confers DNA structure preference on UBFb. Supercoiled (lanes 1 to 12) and linear (lanes 13 to 24) DNA was mixed with His-UBFb (0, 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 pmol as indicated) alone or preincubated with GST-ac1 (40 pmol). The mixture was separated and DNA was visualized as described for panel E.

Given that UBF preferentially binds to the promoter region of the rRNA gene in cells and shows preferential binding to structured DNA in vitro (26), we wondered whether the AR affects the DNA binding preferences of UBF. We first confirmed the preferential binding of UBF to the rRNA gene promoter region in cells by chromatin immunoprecipitation assay (Fig. S4). We previously demonstrated that UBF binding to A′ (−40 to +11 region relative to transcription start site [+1]) (Fig. S4A) was much higher than that of the D (−1987 to −864) region (27). In addition, we found that the enrichment of UBF to the B′ region was significantly higher than that of the A′ and C′ regions (Fig. S4B). We next tested the DNA sequence preference of full-length UBF in vitro. DNA fragments A to D, harboring the upstream region of the rRNA gene transcription start site (Fig. 5D; Fig. S4A), were amplified and used for the binding assay with UBF1. Flag-UBF1 bound to all DNA fragments in a dose-dependent manner with no preference (Fig. 5D). We also tested the Flag-UBF binding to linear and supercoiled plasmid DNA (Fig. 5E). Flag-UBF bound both supercoiled and linear DNA in a dose-dependent manner and showed higher affinity for supercoiled DNA (compare lanes 2 to 5 and 7 to 10), ensuring that full-length UBF shows DNA structure preference as previously reported (26). His-tagged UBFb (amino acids 1 to 187) (Fig. 5A) similarly bound both supercoiled and linear DNAs (Fig. 5F, lanes 1 to 6 and 13 to 18). Although the migration pattern of supercoiled and linear DNA bound by UBFb was different, HMG box 1 alone cannot discriminate DNA structure in vitro. We found that the binding of UBFb to linear DNA was efficiently inhibited by AR (ac1; amino acids 671 to 764) and free linear DNA was increased (lanes 19 to 24). GST-ac1 changed the migration pattern of the supercoiled DNA-UBFb complexes but did not increase free supercoiled DNA (lanes 7 to 12). To test that GST-ac1 was included in the DNA-UBFb complex, Western blotting was performed after separation of the DNA-protein complexes by agarose gel electrophoresis (Fig. S5). The DNA-UBFb complex was detected even in the presence of GST-ac1 (lanes 4 to 6), whereas GST-ac1 was not detected at the DNA-UBFb position. This result indicates that AR confers DNA structure preference on the HMG box 1 without being a part of the DNA-UBFb complex. We also confirmed that supercoiled plasmid DNA structure was not clearly changed by incubation with UBFb and GST-ac1 when analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis (Fig. S5B).

The LR between the HMG boxes and AR plays a crucial role in the nuclear and nucleolar localization of UBF.

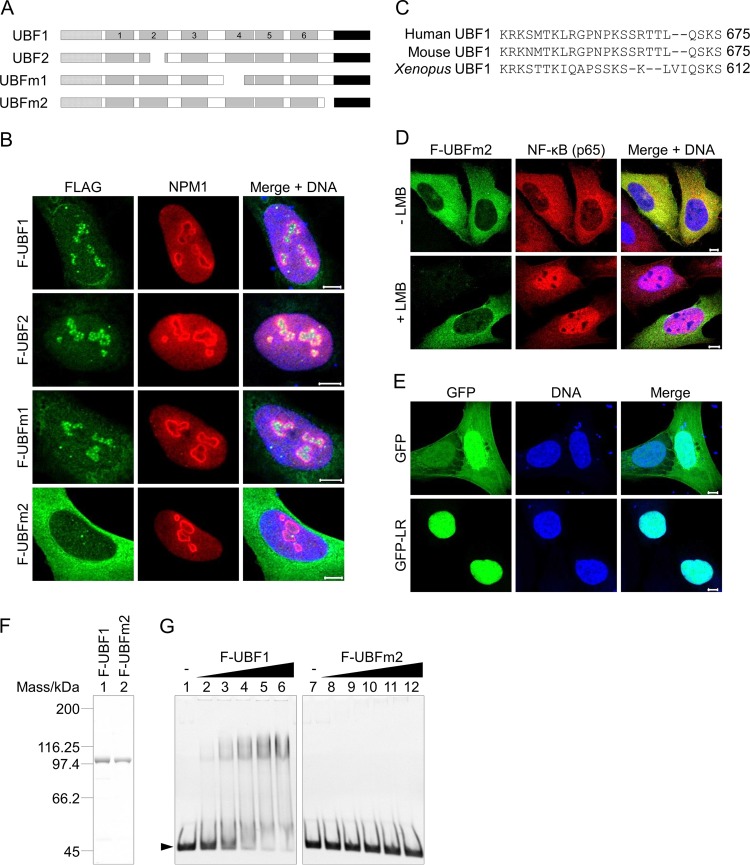

We cloned two UBF mutants (named UBFm1 and UBFm2) in addition to two splicing variants of UBF, UBF1 and UBF2. DNA sequencing revealed that UBFm1 and UBFm2 lack the 52-amino-acid segment within HMG box 4 (amino acids 402 to 453, corresponding to exon 13 of the UBF gene) and the 24-amino-acid segment between HMG box 6 and the AR (amino acids 652 to 675, corresponding to exon 19 of the UBF gene), respectively (Fig. 6A). However, we did not detect cDNAs corresponding to UBFm1 and UBFm2 by reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) using primer sets harboring exons 13 and 19 (Fig. S6), suggesting that they were generated by unknown errors. We could not exclude the possibility that these mutants were generated by alternative splicing with a very small population and selectively amplified during the cDNA cloning process. To examine the effect of the deficient regions in these mutant proteins on the nucleolar localization of UBF, we performed immunofluorescence assays. The results revealed that Flag-UBFm2 was localized to the cytoplasm, whereas Flag-UBFm1 was localized to the nucleolus, as were UBF1 and UBF2, suggesting that the 24-amino-acid segment deleted in UBFm2 functions as a nuclear localization signal (NLS) (Fig. 6B). The 24-amino-acid LR is well conserved between species and contains many basic amino acids (Fig. 6C). Consistent with this observation, previous study has shown that the Xenopus UBF sequence between HMG boxes and the AR is an NLS (20). To exclude the possibility that UBFm2 is efficiently exported from the nucleus to the cytoplasm by deleting LR, immunofluorescence assays were performed in the absence or presence of leptomycin B (LMB), an inhibitor of nuclear export (Fig. 6D). NF-κB (p65) shuttles between the nucleus and the cytoplasm and is detected mainly in the cytoplasm of control cells. However, p65 accumulated in the nucleus after LMB treatment. Under the same assay conditions, Flag-UBFm2 localized to the cytoplasm, indicating that cytoplasmic localization was a consequence of loss of nuclear import. Indeed, when the LR sequence was fused to GFP, GFP-LR localized to the nucleus (Fig. 6E). Taking these results together, we concluded that the LR sequence of human UBF functions as an NLS.

To characterize the function of UBFm2, we examined the DNA binding activity of UBF1 and UBFm2 using purified proteins and DNA (Fig. 6F and G). Flag-UBF1 bound to DNA in a dose-dependent manner. Surprisingly, binding of Flag-UBFm2 to DNA was not detected under our assay conditions. This result raised two possibilities: one is that LR can bind to DNA, and the other is that LR attenuates AR binding to the HMG boxes by competitive binding to the AR. These possibilities were examined using purified proteins (Fig. 7A). We first examined the DNA binding activity of LR and demonstrated that GST-LR, but not GST alone, bound to DNA in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 7B). We next tested whether AR bound to LR by GST pulldown assay. GST-ac1, but not GST, bound to LR tagged with maltose binding protein (MBP), whereas MBP alone did not bind to GST-ac1 (Fig. 7C). These results suggest that LR enhances the DNA binding activity of UBF via two independent functions: (i) LR enhances the DNA binding activity of UBF through its own DNA binding activity, and (ii) LR increases the binding of HMG boxes to DNA by competitive binding to the AR.

FIG 7.

LR associates with both DNA and AR. (A) Schematic diagram of truncated UBF1 mutants. Hatched boxes represent the LR, the 24-amino-acid segment deleted in UBFm2. Numbers shown are the positions of amino acids. (B) DNA binding activity of LR. The 154-bp DNA fragment incubated with GST or GST-LR (0, 0.06, 0.12, 0.18, 0.24, and 0.3 μM) was separated by native PAGE and visualized by GelRed staining. The position of free DNA is indicated by an arrowhead. (C) The LR associates with AR. GST, GST-ac1, MBP, and MBP-LR were expressed and purified, and GST pulldown assays were performed using the purified proteins. Input (lanes 1 and 2) and pulldown proteins with GST and GST-ac1 (lanes 3 to 6) were separated by SDS-PAGE and visualized by CBB staining. Positions of molecular size markers and those of GST and MBP are indicated. (D) Purified proteins. GST-ac1, His-UBFb, and GST-LR (300 ng) were separated by SDS-PAGE and visualized by CBB staining. Positions of molecular size markers are shown at the left. (E) The AR-binding activity of HMG box 1 and LR. GST-ac1 (1 μM) incubated with His-UBFb or GST-LR (0, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 μM) was separated by native PAGE and visualized by CBB staining. (F) Localization of Flag-N670 and -N640. U2OS cells transiently expressing Flag-N670 or -N640 were subjected to immunofluorescence assays with anti-Flag (green) and anti-NCL (red) antibodies. DNA was counterstained with TO-PRO-3 iodide (blue). Bars indicate 5 μm.

The AR associates with the HMG boxes and LR; therefore, we compared the affinities of HMG box 1 and LR for the AR. Purified GST-ac1 was incubated with increasing amounts of His-UBFb or GST-LR and separated by native PAGE (Fig. 7D and E). GST-ac1 is an acidic protein; therefore, it migrates to the cathode on native PAGE (Fig. 7E, lanes 1 and 7). Free GST-ac1 decreased with increasing amounts of UBFb or LR (lanes 2 to 6 and 8 to 12). The affinity of UBFb (HMG box 1) for the AR (GST-ac1) was much higher than that of the LR, suggesting that the AR preferentially associates with the HMG box 1 in full-length UBF1.

We next sought to clarify the effect of LR on the nuclear or nucleolar localization of UBF1 by examining the localization of N670 and N640, which lacks the LR sequence from N670 (Fig. 7A and F). Consistent with the data shown in Fig. 1B, Flag-N670 localized to both the nucleoplasm and nucleolus where NCL was localized. Flag-N640 localized to the cytoplasm because the NLS in LR was lacking, and it was also detected in the nucleolus, suggesting that an additional NLS sequence exists in UBF1. We also found that the nucleolar localization of F-N670 and -N640 was detected in cells depleted with endogenous UBF, suggesting that both N670 and N640 have the ability to localize to the nucleolus independent of dimer formation with endogenous UBF1 (Fig. S3C). Furthermore, it was suggested that the nonspecific DNA/chromatin binding of N640 was decreased by deletion of the LR sequence; therefore, the N640 protein can localize to the nucleoli once it enters the nucleus.

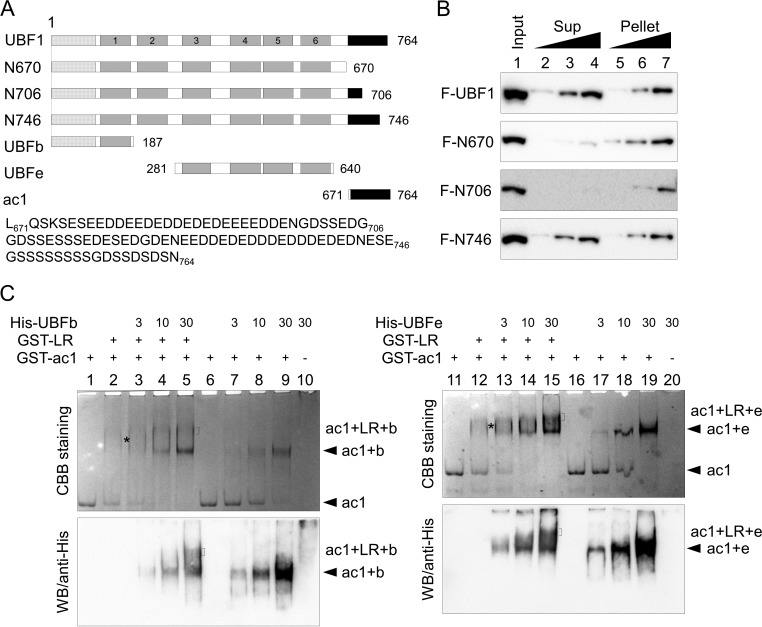

The AR is a long acidic region and associates with multiple sites intramolecularly (Fig. 3 and 4). This raised a possibility that AR concomitantly associates with multiple sites to allow efficient nucleolar localization of UBF. To test this possibility, we examined the importance of the long AR on the fractionation pattern of UBF in cells (Fig. 8A and B). Consistent with the data shown in Fig. 3A, Flag-UBF was fractionated to both Sup and pellet fractions, whereas N670 was mainly in the pellet fraction. The N706 protein was mainly fractionated to the pellet fraction, as was N670, and N746 was fractionated to both Sup and pellet fractions, as was the wild type. These results suggested that the length of the acidic region contributes to regulate the DNA binding activities of multiple DNA binding sites of UBF. We next tested whether AR shows potential ability to bind simultaneously to two DNA binding regions of UBF in vitro (Fig. 8C). GST-ac1 (amino acids 671 to 764) was first mixed with GST-LR (amino acids 652 to 675), and increasing amounts of His-UBFb (amino acids 1 to 187) or UBFe (amino acids 281 to 640) were added to the complex, followed by electrophoresis on native PAGE. GST-ac1 was migrated to the cathode and was shifted upon addition of GST-LR (lanes 1, 2, 11, and 12), ensuring the direct interaction between the ac1 and LR sequences. The addition of His-UBFb and His-UBFe further decreased the mobility of the complexes, and His-tagged proteins were detected in the complexes by Western blotting (Fig. 8C, bottom). These results indicate that the long acidic region of UBF has the ability to bind simultaneously to multiple DNA binding sites of UBF.

FIG 8.

Long acidic tail interacts with multiple DNA binding domains of UBF. (A) Schematic diagram of truncated UBF1 mutants. (B) Subcellular fractionation assay. HeLa cells transiently expressing Flag-UBF1, -N670, -N706, or -N746 were subjected to subcellular fractionation assays. Input (lane 1; 3 × 104 cells), supernatant (Sup), and pellet fractions (lanes 2 to 4 and 5 to 7; 0.6 × 104, 1.5 × 104, and 3 × 104 cells) were separated by SDS-PAGE and subjected to Western blotting (WB) with anti-Flag antibody. Two independent experiments showed similar results. (C) AR associates simultaneously with two DNA binding domains. His-tagged UBFb (3, 10, and 30 pmol for lanes 3 to 5 and 7 to 9) or UBFe (3, 10, and 30 pmol for lanes 13 to 15 and 17 to 19) was added to GST-ac1 (10 pmol) and left unmixed (lanes 7 to 9 and 17 to 19) or mixed with LR (40 pmol) (lanes 2 to 5 and 12 to 15), and the complexes were separated by native PAGE and visualized with CBB staining. His-tagged proteins were detected by Western blotting with anti-His antibody. GST-ac1 alone (10 pmol, lanes 1 and 6), His-UBFb alone (30 pmol, lane 10), and His-UBFe alone (30 pmol, lane 20) were also separated as controls. Positions of free ac1, ac1-LR complex, ac1-LR-His-UBFb complex, or ac1-LR-His-UBFe complex are indicated.

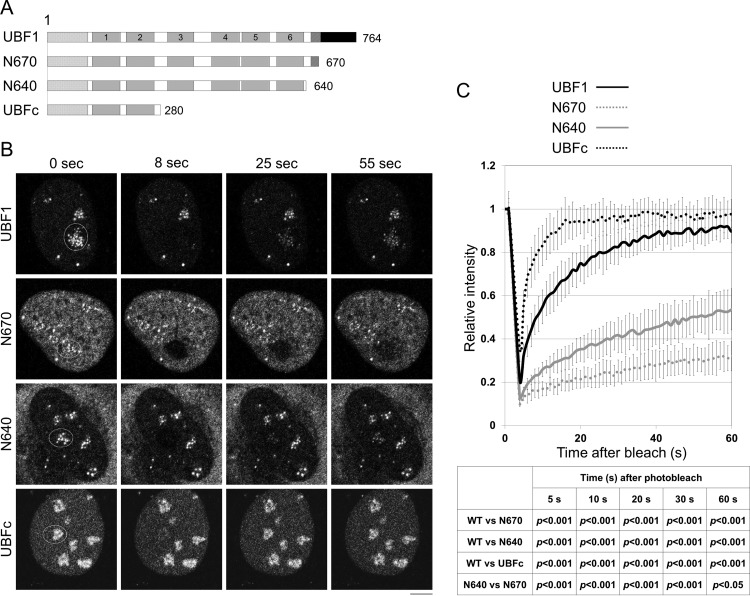

Our results suggest that UBF localizes to the nucleoli through multiple DNA binding sites, and HMG box 1 plays a critical role in the nucleolar localization. To clarify the functions of HMG boxes 3 to 6 and the LR on the nucleolar localization of UBF, we performed fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) assays with cells transiently expressing GFP-UBF1, -N670, -N640, and -UBFc (amino acids 1 to 280) (Fig. 9A and B). GFP signals in the nucleolus were bleached, and the intensities at the bleached area were measured every 1 s for 60 s (Fig. 9B and C). Consistent with a previous report, UBF1 was dynamic and quickly recovered in the nucleolus after photobleaching (28). However, deletion of the AR (N670) significantly reduced the recovery rate of UBF1 (Fig. 9C), suggesting that the AR decreases the stable binding of UBF1 to chromatin. This was consistent with the fractionation experiments shown in Fig. 3A and 8B. The recovery rate of N640 in the nucleolus was significantly increased, although it was much lower than that of full-length UBF1. When HMG boxes 3 to 6 were deleted from N640, the recovery rate of GFP-UBFc was dramatically increased. These results indicate that the LR and HMG boxes 3 to 6 contribute to the stable binding of UBF to nucleolar chromatin once UBF reaches the nucleolus.

FIG 9.

HMG boxes and LR contribute to stable chromatin binding of UBF. (A) Schematic diagram of UBF mutants. (B and C) FRAP analyses of the UBF proteins. U2OS cells transiently expressing GFP-UBF1, -N670, -N640, or -UBFc were grown on glass-based dishes and subjected to FRAP assays. Cells showing similar GFP intensity were picked up and examined. Elliptical regions in the nucleus shown on the left (before bleach) were bleached with a 488-nm laser line, and the GFP intensity before and after photobleach was measured. (C) The recovery curves for GFP-UBF1, GFP-N670, GFP-N640, and GFP-UBFc were plotted as a function of time. Error bars of recovery curves indicate ±SD (n = 10). Statistical analyses were performed by two-tailed Student's t test for the data 5, 10, 20, 30, and 60 s after photobleach, and the P values are shown at the bottom of the graph. Typical images for GFP-UBF1, -N670, -N640, and -UBFc before and after photobleach are shown in panel B. The bar (B) indicates 5 μm.

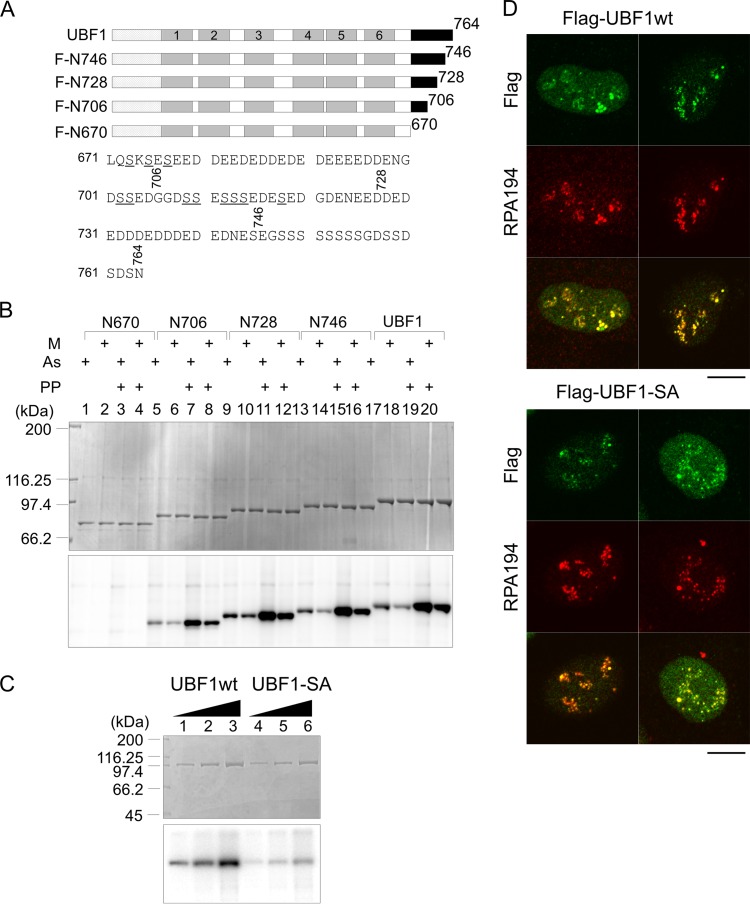

Finally, we tested the effect of phosphorylation of UBF on its nucleolar localization, because it was previously demonstrated that the phosphorylation status of UBF1 affects its localization and the C-terminal region is heavily phosphorylated (29, 30). To identify the phosphorylation sites of UBF1, Flag-tagged proteins were expressed in 293T cells, purified, and subjected to phosphorylation assay using asynchronous and mitotic cell extracts (Fig. 10A and B). We also used purified proteins pretreated with lambda phosphatase to remove phosphor groups added to 293T cells. Wild-type UBF1 was efficiently phosphorylated by both asynchronous and mitotic cell extracts (lanes 17 to 20). Phosphorylation efficiency was increased when the protein was pretreated with lambda phosphatase. This indicates that the phosphorylation sites in vivo at least in part overlapped those in vitro. Importantly, given the much lower phosphorylation level of N670 (lanes 1 to 4) than that of wild-type UBF1, the phosphorylation sites are located at the C-terminal acidic region. The phosphorylation of wild-type UBF1, N746, and N728 was very similar, whereas that of N706 was about half of that of UBF1, N746, and N728. These results suggest that phosphorylation sites are between amino acids 671 and 728. To test the effect of UBF phosphorylation on its localization, the 11 serine residues between 671 and 728 (underlined in the bottom panel of Fig. 10A) all were replaced by alanines. These serine residues were ensured to be phosphorylation sites by in vitro phosphorylation assay (Fig. 10C). Immunofluorescence assay showed that UBF1-SA localized to the nucleoli, as did wild-type UBF1 (Fig. 10D), suggesting that phosphorylation at the C-terminal region does not strongly affect the localization of UBF1.

FIG 10.

Phosphorylation of AR does not clearly affect the nucleolar localization of UBF. (A) Schematic diagram of UBF mutants and the sequence of AR. Serine residues replaced by alanines are underlined at the bottom. (B) Phosphorylation of Flag-tagged UBF mutants. Flag-N670, -N706, -N728, -N748, and full-length UBF1, as indicated at the top, were expressed and purified from 293T cells, left untreated or treated with lambda phosphatase (PP), phosphorylated with asynchronous (As) or mitotic (M) cell extracts in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP, and separated on 7.5% SDS-PAGE, followed by CBB staining and autoradiography (top and bottom, respectively). Positions of molecular mass markers are shown at the top left. (C) Phosphorylation of wild-type and mutant UBF1 in vitro. Flag-UBF1-SA contains substitution mutations at all serine residues between 671 and 728 as shown in panel A. Flag-UBF1 and Flag-UBF1-SA were expressed in 293T cells and purified with anti-Flag affinity gel. The purified proteins (100, 200, and 400 ng) were phosphorylated with asynchronous cell extracts and analyzed as described for panel B. (D) Localization of wild-type and phosphorylation mutant UBF. Flag-UBF1 and -UBF1-SA were expressed in U2OS cells, and their localization was examined by immunofluorescence assay with anti-Flag and anti-RPA194 antibodies. Bars indicate 10 μm.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we investigated why the transcription factor UBF specifically localizes to the nucleolus. Our results suggest that the HMG boxes, LR, and AR cooperatively regulate the nucleolar localization of UBF. The AR is required for the efficient nucleolar localization of UBF, possibly through its intramolecular associations with HMG boxes and the LR sequence. After synthesis of UBF1 in the cytoplasm, the C-terminal acidic region strongly associates with HMG boxes 1 and 3 to 6, exposing the NLS sequence in LR to nuclear import machineries. Upon translocation to the nucleus, the LR sequence is released and competes with HMG boxes to bind to AR. The ability of HMG box 1 to associate with nucleolar chromatin, possibly in combination with other HMG boxes, mediates the nucleolar localization of UBF. In addition, the AR may contribute to the nucleolar localization of UBF, because it localizes to the nucleolus possibly through its association with nucleolar transcription factors (Fig. 2). The AR also attenuates binding of UBF to rRNA genes through interactions with HMG boxes and the LR. The stability of the association between UBF and chromatin may be important for the formation of proper chromatin structure and the stimulation of Pol I-mediated transcription.

UBFm2 localizes to the cytoplasm and nucleolus upon deletion of the AR (the N640 protein) (Fig. 6 and 7), suggesting that an additional NLS exists in the HMG boxes. In UBFm2, the AR is associated with HMG boxes and blocks its activities. Consistent with this idea, the HMG box proteins SRY and SOX9 have highly conserved NLSs within the HMG boxes (31). In addition, a previous study suggested that the basic amino acid sequence located in HMG box 4 of mouse UBF is an NLS (19).

We demonstrated that the AR plays multiple roles in the nucleolar localization of UBF1. The AR (amino acids 671 to 764) consists of two acidic clusters (amino acids 671 to 706 and 707 to 746) and a serine-rich region (amino acids 747 to 764) (Fig. 8A). The binding of AR with the Pol I machineries was decreased by deletion of 19 C-terminal amino acids (Fig. 2C). These results suggest that multiple interactions of the AR with the Pol I machineries, including the SL1 complex, are required for the stable association between UBF1 and the Pol I machineries in vivo. We also noted that the localization of RPA194 was slightly changed upon expression of AR (GFP-C1) (Fig. 2B), and excess AR expression decreased the intensity of RPA194 foci. This could be because the nucleoplasmic AR induces the translocation of the Pol I machineries from the nucleolus to the nucleoplasm. This supports previous findings that UBF is required for the recruitment of the Pol I machineries to the nucleolus (8). We also could not exclude the possibility that the interaction between AR and the Pol I machineries contributes to stabilizing the nucleolar localization of UBF.

We showed that the AR attenuates nonspecific DNA binding of HMG boxes and confers DNA structural preferences to HMG box 1. Similar observations have been reported for HMG box proteins (32, 33). The acidic region was shown to mask the DNA binding faces of HMG boxes of HMGB1 (34). Our results suggest that the AR of UBF also covers the multiple HMG boxes and LR to inhibit nonspecific DNA binding of UBF (Fig. 8C). It should also be mentioned that AR contains many serine residues targeted by casein kinase 2 (CK2). In fact, it was previously reported that the AR of UBF is highly phosphorylated by CK2, and this phosphorylation regulates the function of UBF (21, 30). In addition, phosphorylation of the acidic region of the insect HMG proteins was reported to affect the DNA binding specificity (35). However, we demonstrated that the phosphorylation at the AR was not required for the nucleolar localization of UBF1 (Fig. 10). Further analysis is required to determine the effect of phosphorylation at the AR on the stable nucleolar chromatin binding and the intramolecular associations with HMG boxes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid construction, cell cultures, transfection of plasmids, and antibodies.

Construction of plasmid vectors is described in the supplemental material. All UBF truncated mutant proteins constructed and used in this study are schematically shown in Fig. S1 in the supplemental material. U2OS, 293T, and HeLa cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Nacalai Tesque) supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) fetal bovine serum (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 1× penicillin-streptomycin solution (Nacalai Tesque), and 2.5 μg/ml plasmocin (InvivoGen). For leptomycin B (LMB) treatment, U2OS cells were incubated in the presence of 100 nM LMB (LC Laboratories) for 3 h. Transfection of plasmids was performed using GeneJuice (Merck Millipore) or polyethylenimine. The following antibodies were used in this study: anti-Flag (M2; Sigma-Aldrich) for Western blotting or immunofluorescence assay and anti-DDDDK-tag (PM020; Medical and Biological Laboratories) for immunofluorescence assay; anti-RPA194 (C-1; Santa Cruz Biotechnology); anti-RRN3 (ab112052; Abcam); anti-TBP (mAbcam 51841; Abcam); anti-NAP1L1 (2609C3a; Santa Cruz Biotechnology); anti-NPM1 (SPM207; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for Western blotting and anti-NPM1 (polyclonal antibody generated by injecting the C-terminal region of NPM1 to rabbits) and anti-NPM1 (FC-61991; Thermo Fisher Scientific) for immunofluorescence assay; antipolyhistidine (His) (HIS-1; Sigma-Aldrich); anti-GST (GS019;Nacalai Tesque); anti-NF-κB (p65) (ab7970; Abcam); and anti-C23 (NCL) (D-6; Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

Immunofluorescence and FRAP assay.

U2OS cells grown on coverslips were fixed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 3% (wt/vol) paraformaldehyde for 10 min, permeabilized for 5 min in cytoskeleton buffer [10 mM piperazine-N,N′-bis(2-ethanesulfonic acid)–KOH (pH 7.0), 100 mM NaCl, 3 mM MgCl2, and 300 mM sucrose] containing 0.5% (vol/vol) Triton X-100 and incubated with Tris-buffered saline (TBS) containing 0.1% (wt/vol) fat-free milk (Morinaga) and 0.1% (vol/vol) Tween 20. The cells were incubated with primary antibody for 1 h, washed with TBS containing 0.1% (vol/vol) Tween 20, and incubated with secondary antibodies (Alexa Fluor 488– or 568–goat anti-mouse or anti-rabbit IgG antibody; Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 30 min. DNA was stained with TO-PRO-3 iodide (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 10 min. The coverslips were set on an inverted microscope (LSM Exciter; Carl Zeiss Microscopy) with a Plan Apochromat 63×, 1.4-numeric-aperture oil immersion objective lens.

For FRAP assay, U2OS cells were transfected with pEGFP-C1-UBF1, -N670, -N640, or -UBFc and grown in 35-mm glass-based dishes (AGC Techno Glass). The dish was set on an inverted microscope (LSM Exciter; Carl Zeiss Microscopy) 16 h after transfection in an air chamber containing 5% CO2 at 37°C. The mobility of proteins was analyzed by photobleaching with a 488-nm argon laser (50 iterations), and images were collected (512 by 512 pixels; zoom, 3.0; scan speed, 9; pinhole, 1 airy unit; LP505 emission filter; 10% transmission of a 488-nm argon laser) every 1 s. The fluorescence intensity of the bleached area was measured using ZEN2009 software (Carl Zeiss Microscopy). Background and reference intensities first were subtracted from all intensities measured, and relative fluorescence intensity (RFI) was calculated as RFI = (Ta − Ba)/(T0 − B0) × (R0 − B0)/(Ra − Ba), where Ta, Ba, and Ra and T0, B0, and R0 are the fluorescence intensities of bleached, background, and reference areas at each time point and initial intensities, respectively. Background and reference areas are the area outside the cell and the nonbleached nucleolus in the same cell, respectively.

Immunoprecipitation.

293T cells expressing Flag-tagged proteins were suspended in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.9], 0.2 mM EDTA, and 0.1% [vol/vol] Triton X-100) containing 150 mM NaCl and sonicated. After centrifugation, the supernatants were mixed with anti-Flag M2 affinity gel (Sigma-Aldrich) and incubated at 4°C for 2 h with rotation. The resins were washed with lysis buffer containing 150 mM NaCl. The bound proteins were eluted with TBS containing 150 μg/ml Flag peptide and separated by SDS-PAGE followed by Western blotting.

Subcellular fractionation.

HeLa cells were suspended and incubated in fractionation buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.9], 150 mM NaCl, 0.2 mM EDTA, and 0.5% [vol/vol] Triton X-100) on ice for 10 min. After centrifugation, the supernatants (Sup) were collected. The pellets were suspended in SDS sample buffer (62.5 mM Tris-HCl [pH 6.8], 10% [vol/vol] glycerol, 145 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 2.5% [vol/vol] SDS, and 0.005% [vol/vol] bromophenol blue) containing 150 mM NaCl and sonicated (pellet). Each fraction was separated by SDS-PAGE followed by Western blotting or Coomassie brilliant blue (CBB) staining.

Purification of recombinant proteins.

To express the recombinant proteins, Escherichia coli strain BL21(DE3) or BL21(DE3)pLysS transformed with appropriate plasmids was grown at 37°C until the optical density at 600 nm reached 0.3. Expression of the recombinant proteins was induced by addition of 0.1 mM isopropyl-β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside at 18°C for 12 to 16 h. Bacterial cell pellets were sonicated in His binding buffer (50 mM Na2HPO4, 50 mM NaH2PO4, 500 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, and 0.1% [vol/vol] Triton X-100), GST binding buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.9], 150 mM NaCl, 0.2 mM EDTA, and 0.1% [vol/vol] Triton X-100), or MBP binding buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.9], 200 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 1 mM dithiothreitol [DTT]). The proteins were purified with HIS-Select nickel affinity gel (Sigma-Aldrich), glutathione-Sepharose 4B (GE Healthcare), or amylose resin (New England BioLabs) according to the manufacturers' instructions. The resins were treated with nuclease S7 (Roche Diagnostics) before elution of the proteins to remove DNA and RNA nonspecifically bound to the recombinant proteins. To purify Flag-tagged proteins, 293T cells expressing Flag-tagged proteins were suspended in hypotonic buffer (10 mM HEPES-NaOH [pH 8.0], 1.5 mM MgCl2, and 10 mM KCl) containing 0.2% (vol/vol) Triton X-100 and 400 mM NaCl and incubated at 4°C for 30 min with rotation. The supernatants mixed with equal volumes of hypotonic buffer were centrifuged, mixed with anti-Flag M2 affinity gel, and incubated at 4°C for 2 h with rotation. The bound proteins were eluted with TBS containing 150 μg/ml Flag peptide after extensive washing with the buffer containing 300 mM NaCl. Purified proteins were dialyzed against dialysis buffer (20 mM HEPES-NaOH [pH 8.0], 50 mM NaCl, 10% [vol/vol] glycerol, and 0.5 mM DTT) at 4°C for 4 h with stirring.

GST pulldown and mobility shift assays.

For Fig. 3C and D, purified GST or GST-C1 was mixed with glutathione-Sepharose 4B in dialysis buffer containing 1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin (BSA) (F-V; Nacalai Tesque) and 0.1% (vol/vol) Triton X-100 and incubated at 4°C for 1 h with rotation. The protein-bound resins were mixed with purified His-tagged proteins in binding buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.9], 0.2 mM EDTA, and 0.1% [vol/vol] Triton X-100) containing 50 mM NaCl, incubated at 4°C for 1 h with rotation, and washed with the same buffer. For Fig. 7C, the E. coli lysates expressing GST or GST-ac1 were mixed with glutathione-Sepharose 4B in binding buffer containing 50 mM NaCl and incubated at 4°C for 30 min with rotation. The protein-bound resin was washed with binding buffer containing 500 mM NaCl, mixed with purified MBP or MBP-LR in binding buffer containing 50 mM NaCl, incubated at 4°C for 1 h with rotation, and washed with the same buffer. The bound proteins were eluted with SDS sample buffer and separated by SDS-PAGE followed by Western blotting or CBB staining.

For protein mobility shift assay, purified GST-ac1 and His-UBFb or GST-LR were mixed in dialysis buffer and incubated at 30°C for 30 min. The mixtures were separated by 5% native PAGE in 1× Tris-glycine buffer followed by CBB staining.

For DNA mobility shift assay, the 154-bp DNA fragment was amplified from pcDNA3 vector (Thermo Fisher Scientific) by PCR with primer set T7pro and Sp6pro (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). DNA and purified proteins were mixed in dialysis buffer containing 50 μg/ml BSA and incubated at 30°C for 30 min. The mixtures were separated by 4% native PAGE in 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA buffer. DNA was visualized by GelRed (Biotium) staining. pBluescript II SK(+) plasmid DNA was used as supercoiled DNA, and the same DNA was linearized by BamHI treatment. DNA-protein mixtures were separated by 0.8% agarose gel in 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA buffer and visualized by GelRed staining.

Split Renilla luciferase complementation assay.

Purified Flag-tagged split Renilla luciferase-UBF fusion proteins were mixed in dialysis buffer. The Renilla luciferase assay was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions (Promega). The relative luminescence intensity was measured for 10 s with a Mini Lumat (Berthold Technologies).

In vitro phosphorylation assay.

Flag-tagged proteins were expressed in 293T cells and purified with anti-Flag affinity gel as described above. The gel bound with the Flag-tagged proteins was mixed with 10 μg of cell extracts and [γ-32P]ATP (2 μCi; PerkinElmer) in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) and 10 mM MgCl2, incubated at 37°C for 30 min, and washed with 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.9), 0.2 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, and 0.1% (vol/vol) Triton X-100. The bound proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and visualized by CBB staining. The gel was dried and protein phosphorylation was detected by autoradiography. Cell extracts were prepared as described previously. For Fig. 10B, the Flag-tagged proteins were treated with lambda phosphatase (New England BioLabs) and used for phosphorylation assay.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Béla Gyurcsik (University of Szeged, Hungary) for the pMAL plasmid. We thank Enago (www.enago.jp) for English language review.

This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan to K.N. (24115001 and 25291001) and M.O. (26440021 and 17K07300).

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/MCB.00218-17.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jantzen HM, Admon A, Bell SP, Tjian R. 1990. Nucleolar transcription factor hUBF contains a DNA-binding motif with homology to HMG proteins. Nature 344:830–836. doi: 10.1038/344830a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Henras AK, Soudet J, Gerus M, Lebaron S, Caizergues-Ferrer M, Mougin A, Henry Y. 2008. The post-transcriptional steps of eukaryotic ribosome biogenesis. Cell Mol Life Sci 65:2334–2359. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8027-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roussel P, Andre C, Masson C, Geraud G, Hernandez-Verdun D. 1993. Localization of the RNA polymerase I transcription factor hUBF during the cell cycle. J Cell Sci 104(Part 2):327–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roussel P, Andre C, Comai L, Hernandez-Verdun D. 1996. The rDNA transcription machinery is assembled during mitosis in active NORs and absent in inactive NORs. J Cell Biol 133:235–246. doi: 10.1083/jcb.133.2.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jordan P, Mannervik M, Tora L, Carmo-Fonseca M. 1996. In vivo evidence that TATA-binding protein/SL1 colocalizes with UBF and RNA polymerase I when rRNA synthesis is either active or inactive. J Cell Biol 133:225–234. doi: 10.1083/jcb.133.2.225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O'Sullivan AC, Sullivan GJ, McStay B. 2002. UBF binding in vivo is not restricted to regulatory sequences within the vertebrate ribosomal DNA repeat. Mol Cell Biol 22:657–668. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.2.657-668.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen D, Belmont AS, Huang S. 2004. Upstream binding factor association induces large-scale chromatin decondensation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101:15106–15111. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404767101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mais C, Wright JE, Prieto JL, Raggett SL, McStay B. 2005. UBF-binding site arrays form pseudo-NORs and sequester the RNA polymerase I transcription machinery. Genes Dev 19:50–64. doi: 10.1101/gad.310705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prieto JL, McStay B. 2007. Recruitment of factors linking transcription and processing of pre-rRNA to NOR chromatin is UBF-dependent and occurs independent of transcription in human cells. Genes Dev 21:2041–2054. doi: 10.1101/gad.436707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sanij E, Poortinga G, Sharkey K, Hung S, Holloway TP, Quin J, Robb E, Wong LH, Thomas WG, Stefanovsky V, Moss T, Rothblum L, Hannan KM, McArthur GA, Pearson RB, Hannan RD. 2008. UBF levels determine the number of active ribosomal RNA genes in mammals. J Cell Biol 183:1259–1274. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200805146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stros M, Launholt D, Grasser KD. 2007. The HMG-box: a versatile protein domain occurring in a wide variety of DNA-binding proteins. Cell Mol Life Sci 64:2590–2606. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-7162-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jantzen HM, Chow AM, King DS, Tjian R. 1992. Multiple domains of the RNA polymerase I activator hUBF interact with the TATA-binding protein complex hSL1 to mediate transcription. Genes Dev 6:1950–1963. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.10.1950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tuan JC, Zhai W, Comai L. 1999. Recruitment of TATA-binding protein-TAFI complex SL1 to the human ribosomal DNA promoter is mediated by the carboxy-terminal activation domain of upstream binding factor (UBF) and is regulated by UBF phosphorylation. Mol Cell Biol 19:2872–2879. doi: 10.1128/MCB.19.4.2872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leblanc B, Read C, Moss T. 1993. Recognition of the Xenopus ribosomal core promoter by the transcription factor xUBF involves multiple HMG box domains and leads to an xUBF interdomain interaction. EMBO J 12:513–525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bazett-Jones DP, Leblanc B, Herfort M, Moss T. 1994. Short-range DNA looping by the Xenopus HMG-box transcription factor, xUBF. Science 264:1134–1137. doi: 10.1126/science.8178172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O'Mahony DJ, Rothblum LI. 1991. Identification of two forms of the RNA polymerase I transcription factor UBF. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 88:3180–3184. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.8.3180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McStay B, Frazier MW, Reeder RH. 1991. xUBF contains a novel dimerization domain essential for RNA polymerase I transcription. Genes Dev 5:1957–1968. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.11.1957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Copenhaver GP, Putnam CD, Denton ML, Pikaard CS. 1994. The RNA polymerase I transcription factor UBF is a sequence-tolerant HMG-box protein that can recognize structured nucleic acids. Nucleic Acids Res 22:2651–2657. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.13.2651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maeda Y, Hisatake K, Kondo T, Hanada K, Song CZ, Nishimura T, Muramatsu M. 1992. Mouse rRNA gene transcription factor mUBF requires both HMG-box1 and an acidic tail for nucleolar accumulation: molecular analysis of the nucleolar targeting mechanism. EMBO J 11:3695–3704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dimitrov SI, Bachvarov D, Moss T. 1993. Mapping of a sequence essential for the nuclear transport of the Xenopus ribosomal transcription factor xUBF using a simple coupled translation-transport and acid extraction approach. DNA Cell Biol 12:275–281. doi: 10.1089/dna.1993.12.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin CY, Navarro S, Reddy S, Comai L. 2006. CK2-mediated stimulation of Pol I transcription by stabilization of UBF-SL1 interaction. Nucleic Acids Res 34:4752–4766. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beckmann H, Chen JL, O'Brien T, Tjian R. 1995. Coactivator and promoter-selective properties of RNA polymerase I TAFs. Science 270:1506–1509. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5241.1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hempel WM, Cavanaugh AH, Hannan RD, Taylor L, Rothblum LI. 1996. The species-specific RNA polymerase I transcription factor SL-1 binds to upstream binding factor. Mol Cell Biol 16:557–563. doi: 10.1128/MCB.16.2.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller G, Panov KI, Friedrich JK, Trinkle-Mulcahy L, Lamond AI, Zomerdijk JC. 2001. hRRN3 is essential in the SL1-mediated recruitment of RNA polymerase I to rRNA gene promoters. EMBO J 20:1373–1382. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.6.1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paulmurugan R, Gambhir SS. 2003. Monitoring protein-protein interactions using split synthetic renilla luciferase protein-fragment-assisted complementation. Anal Chem 75:1584–1589. doi: 10.1021/ac020731c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hu CH, McStay B, Jeong SW, Reeder RH. 1994. xUBF, an RNA polymerase I transcription factor, binds crossover DNA with low sequence specificity. Mol Cell Biol 14:2871–2882. doi: 10.1128/MCB.14.5.2871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ueshima S, Nagata K, Okuwaki M. 2014. Upstream binding factor-dependent and pre-rRNA transcription-independent association of pre-rRNA processing factors with rRNA gene. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 443:22–27. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen D, Dundr M, Wang C, Leung A, Lamond A, Misteli T, Huang S. 2005. Condensed mitotic chromatin is accessible to transcription factors and chromatin structural proteins. J Cell Biol 168:41–54. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200407182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O'Mahony DJ, Xie WQ, Smith SD, Singer HA, Rothblum LI. 1992. Differential phosphorylation and localization of the transcription factor UBF in vivo in response to serum deprivation. In vitro dephosphorylation of UBF reduces its transactivation properties. J Biol Chem 267:35–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Voit R, Schnapp A, Kuhn A, Rosenbauer H, Hirschmann P, Stunnenberg HG, Grummt I. 1992. The nucleolar transcription factor mUBF is phosphorylated by casein kinase II in the C-terminal hyperacidic tail which is essential for transactivation. EMBO J 11:2211–2218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sudbeck P, Scherer G. 1997. Two independent nuclear localization signals are present in the DNA-binding high-mobility group domains of SRY and SOX9. J Biol Chem 272:27848–27852. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.44.27848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stros M, Stokrova J, Thomas JO. 1994. DNA looping by the HMG-box domains of HMG1 and modulation of DNA binding by the acidic C-terminal domain. Nucleic Acids Res 22:1044–1051. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.6.1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wisniewski JR, Szewczuk Z, Petry I, Schwanbeck R, Renner U. 1999. Constitutive phosphorylation of the acidic tails of the high mobility group 1 proteins by casein kinase II alters their conformation, stability, and DNA binding specificity. J Biol Chem 274:20116–20122. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.40.28175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Watson M, Stott K, Thomas JO. 2007. Mapping intramolecular interactions between domains in HMGB1 using a tail-truncation approach. J Mol Biol 374:1286–1297. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.09.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ribeiro FS, de Abreu da Silva IC, Carneiro VC, Belgrano Fdos S, Mohana-Borges R, de Andrade Rosa I, Benchimol M, Souza NR, Mesquita RD, Sorgine MH, Gazos-Lopes F, Vicentino AR, Wu W, de Moraes Maciel R, da Silva-Neto MA, Fantappie MR. 2012. The dengue vector Aedes aegypti contains a functional high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) protein with a unique regulatory C-terminus. PLoS One 7:e40192. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.