Abstract

Background

The past decade of research has seen considerable interest in computer-based approaches designed to directly target cognitive mechanisms of anxiety, such as Attention Bias Modification (ABM).

Methods

By pooling patient-level datasets from randomized controlled trials of ABM that utilized a dot-probe training procedure, we assessed the impact of training ‘dose’ on relevant outcomes among a pooled sample of 693 socially anxious adults.

Results

A paradoxical effect of the number of training trials administered was observed for both post-training social anxiety symptoms and behavioral attentional bias (AB) towards threat (the target mechanism of ABM). Studies administering a large (>1280) number of training trials showed no benefit of ABM over control conditions, while those administering fewer training trials showed significant benefit for ABM in reducing social anxiety (p=.02). These moderating effects of dose were not better explained by other examined variables and previously identified moderators, including patient age, training setting (lab vs. home), or type of anxiety assessment (clinician vs. self-report).

Conclusions

Findings inform the optimal dosing for future dot-probe-style ABM applications in both research and clinical settings, and suggest several novel avenues for further research.

Keywords: attention bias modification, attention training, social anxiety, patient-level meta-analysis, dose-response

Introduction

Anxiety disorders are characterized by altered information processing patterns, including preferential allocation of attention towards threat-relevant information (henceforth, ‘attentional bias’; AB). Biased attention towards disorder-relevant cues is a highly transdiagnostic construct, present across a very wide range of psychopathology spanning internalizing and externalizing conditions [e.g., anxiety (Bar-Haim, Lamy, Pergamin, Bakermans-Kranenburg, & van IJzendoorn, 2007), depression (Peckham, McHugh, & Otto, 2010), trauma (Naim et al., 2014), suicidality (Cha, Najmi, Park, Finn, & Nock, 2010), substance use (Waters, Marhe, & Franken, 2012), abuse perpetration (Smith & Waterman, 2004), unhealthy eating (Calitri, Pothos, Tapper, Brunstrom, & Rogers, 2010)]. Patterns of AB also appear fairly well-preserved across the life span; for instance, anxious individuals from pediatric (Price et al., 2013) to geriatric (Mohlman, Price, & Vietri, 2013; Price, Siegle, & Mohlman, 2012) samples show similar patterns of AB. Broadly, modifying the focus of attention is a core feature or posited mechanism of treatments as diverse as cognitive-behavioral therapy, Eastern meditation practices, and serotonergic medications (Harmer, Goodwin, & Cowen, 2009), suggesting a possible common pathway to symptom relief.

The past decade has seen growing interest in the development of automated, mechanistic treatments designed to modulate attentional patterns directly (MacLeod & Clarke, 2015). Such interventions take advantage of technology in order to increase patient access, reduce cost, and minimize aversive consequences (Mohr, Burns, Schueller, Clarke, & Klinkman, 2013). In disorders of negative affect in particular (e.g., anxiety), hypervigilance towards negative information is seen as a key factor in the etiology and maintenance of affective dysfunction. Initial data strongly supported a causal role for AB in contributing to anxiety vulnerability (MacLeod, Rutherford, Campbell, Ebsworthy, & Holker, 2002) and the therapeutic potential of Attention Bias Modification (ABM) interventions in clinical populations (Amir, Beard, Burns, & Bomyea, 2009; Amir, Beard, Taylor, et al., 2009). However, more recent studies have lessened enthusiasm, reporting null or clinically insignificant effects (e.g., Beard, Sawyer, & Hofmann, 2012; Carlbring et al., 2012). Critically, the extant literature suggests that if and when interventions are effective in modulating attentional patterns, symptoms are reduced in turn (Clarke, Notebaert, & Macleod, 2014; MacLeod & Clarke, 2015; Price, Wallace, et al., 2016). Thus, the mechanistic target itself—AB—has been well validated, while the ability to manipulate the target remains inconsistent, hindering clinical translation.

The current study extends a prior metaanalytic report where we used a pooled patient-level meta-analysis approach (Price, Wallace, et al., 2016). We compiled raw, per-patient data from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of ABM, administered to adults with elevated levels of anxiety (according to clinical diagnosis or symptom scale distributions). This approach offers unique advantages over standard meta-analytic techniques, including an order-of-magnitude increase in data points analyzed on each variable (many per study rather than one summary measure per study)—which substantially increases power, particularly for testing moderators and mediators (Riley, Lambert, & Abo-Zaid, 2010)—and the ability to test hypotheses not reported in original studies. Our previous report suggested that ABM is efficacious in reducing clinical symptoms under specific circumstances—namely, for patients who were younger (≤37y), trained in the lab (rather than at home/via Internet), and/or assessed by clinicians (rather than via self-report). Furthermore, our mediational analyses supported posited mechanistic links between AB and anxiety reduction, validating ABM’s theoretical basis by suggesting ABM exerts effects on anxiety via its target mechanism. However, we previously focused narrowly on a constrained set of a priori hypotheses and did not assess the influence of additional design decisions made by investigators. Here, we aimed to leverage this unique dataset to answer a simple yet critical question that faces every researcher or clinician wishing to apply ABM to a clinical population: how many trials (repetitions) of ABM are optimal in order to achieve symptom reduction?

In examining this question, previous standard (study-level) meta-analyses have typically quantified dose as the number of discrete sessions of training given. However, learning opportunities both within and between sessions are important in ABM (Abend et al., 2013; Abend, Pine, Fox, & Bar-Haim, 2014), which can be quantified succinctly by calculating the total number of training trials given (i.e. number of sessions * training trials/session). Only one previous meta-analysis explored the impact of dose among clinical intervention studies, and failed to reveal significant effects of dose on clinical anxiety symptoms (Heeren, Mogoase, Philippot, & McNally, 2015). Meta-analyses combining clinical and non-clinical samples have also sought to address this question, but these analyses typically include many studies where only a single session of ABM is given (in contrast to clinical intervention studies, where some degree of cross-session repetition is assumed to be critical, and almost always included), and have also sometimes combined diverse forms of cognitive bias modification (ABM, interpretation bias training) and clinical measures (depression, anxiety), complicating interpretation. When examining dose as a potential moderator, these meta-analyses in combined (clinical+non-clinical) samples have reported quite mixed results, ranging from no significant moderating effect on anxiety measures (Hakamata et al., 2010; Mogoaşe, David, & Koster, 2014), to an enhanced effect of ABM on subjective post-training outcomes when more sessions are given (Beard et al., 2012), to equivocal findings driven by a binary distinction for single vs. multiple sessions (Hallion & Ruscio, 2011), to a paradoxical inverse relationship between number of sessions and clinical measures (Cristea, Kok, & Cuijpers, 2015). Thus, meta-analyses to date have failed to resolve the crucial question of how to optimize ABM dose in order to achieve maximal clinical benefit. We sought to address this fundamental question with increased power and precision in our pooled patient-level dataset, focusing on a precise quantification of dose (total number of training trials), one specific intervention (dot-probe-based ABM), and one specific, clinical outcome (social anxiety symptoms).

Methods

Study Identification and Selection

All details of the metaanalytic methods have been described previously (Price, Wallace, et al., 2016). The metaanalytic protocol was pre-registered at: http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/ (CRD42015019558). Briefly, PubMed, PsychINFO, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) were searched over the period 01/01/2002-05/01/2015 using search terms and synonyms representing ABM (“attention* bias modification,” “attention* *training,” “ABM”) and anxiety (“anxiety”/exp, anxi*). A stand-alone ABM intervention was required, defined as any automated procedure designed to directly alter attention towards threat. An RCT design was required to minimize bias. Allowable control conditions included sham or inverse (towards threat) variants of the same computer task. A constraint in patient-level metaanalysis is the use of uniform outcome measures, as there is no validated method to put individual patient scores, obtained on non-identical scales, into the same ‘space,’ and the assumptions that would be required in order to standardize disparate scales (e.g., that all scales measure the same construct; that all studies had a similar distribution of scores across their full sample) were deemed statistically inappropriate. Thus, for the dataset analyzed here, the use of the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (LSAS) as an outcome (in either clinician-rated or self-report format, which are identical questionnaires producing highly convergent scores (Fresco et al., 2001)) was required, as the literature review revealed this was the most commonly used anxiety outcome measure amongst otherwise-eligible studies. Finally, in order to measure ABM’s target mechanism (AB) using reasonably uniform procedures, a dot-probe task (described below) was required at the start and end of the intervention (either as a distinct pre/post-training assessment, or as a first and last ABM training session; see details below). Raw trial-by-trial reaction time and accuracy data were requested for each participant to allow uniform methods to be applied in calculating AB indices [see (Price, Wallace, et al., 2016)]. In cases where trial-level data were not retained, pre-calculated AB scores per-participant were requested. Of thirteen eligible studies, eleven studies (Table 1) contributed at least one endpoint. See (Price, Wallace, et al., 2016) for study quality assessments and additional methodological details.

Table 1.

Description of included studies

| Study | Sample | Age | Control condition(s)b |

Total # Training Trials |

Training Protocol |

Approximate pre-post assessment interval |

Training Setting |

Stimulus modality |

Outcome variables received |

Completer Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Amir, Beard, Taylor, et al., 2009) | Social Anxiety Disorder (n=48) | mean=29.4, SD=10.8, range=19–62 | Sham training | 1280 (“low” dose) | 2x/week for 4 weeks | 4 weeks | Laboratory | Facial expressions (disgust and neutral) | LSAS-CR, raw AB data (training) | 92% |

| (Boettcher, Berger, & Renneberg, 2012) | Social Anxiety Disorder (n=68) | mean=37.9, SD=11.2, range=18–69 | Sham training | 1280 (“low” dose) | 2x/week for 4 weeks | 4 weeks | Home | Facial expressions (disgust and neutral) | LSAS-SR | 94% |

| (Boettcher et al., 2013) | Social Anxiety Disorder (n=129) | mean=38.3, SD=12.3, range=18–65 | Sham training; Inverse training [Stimuli presented for 1000ms (first half of trials each session), 500ms (second half of trials each session)] | 2688 (“high” dose) | 1x/day for 2 weeks | 2 weeks | Home | Two conditions (collapsed for present analyses): words only or mixed trials of words and pictures | LSAS-SR, raw AB data (assessment) | 96% |

| (Boettcher, Hasselrot, Sund, Andersson, & Carlbring, 2014) | Social Anxiety Disorder (n=133) | mean=33.4, SD=10.4, range=18–59 | Sham training; Inverse trainingc [Stimuli presented for 1000ms (first half of trials each session), 500ms (second half of trials each session)] | 2688 (“high” dose) | 1x/day for 2 weeks | 2 weeks | Home | Mixed trials of words and pictures | LSAS-SR, pre-calculated AB scores (assessment) | 95.5% |

| (Britton et al., 2015) | High Social Anxiety (n=53) | mean=22, SD=3.1, range=18–30 | Sham training | 1728 (“high” dose) | 2x/week for 4 weeks + 1 extra training session in fMRI scanner | 4 weeks | Laboratory | Facial expressions (angry and neutral) | LSAS-CR, raw AB data (assessment) | 83% |

| (Bunnell, Beidel, & Mesa, 2013) | Social Anxiety Disorder (n=32) | mean=24.3, SD=7.5, range=18–45 | Sham training | 1280 (“low” dose) | 2x/week for 4 weeks | 4 weeks | Laboratory | Facial expressions (disgust and neutral) | LSAS-SR | 97% |

| (Carlbring et al., 2012) | Social Anxiety Disorder (n=79) | mean=36.5, SD=12.7, range=18–73 | Sham training | 1280 (“low” dose) | 2x/week for 4 weeks | 4 weeks | Home | Facial expressions (disgust and neutral) | LSAS-SR, raw AB data (training) | 96% |

| (Fang, Sawyer, Aderka, & Hofmann, 2013) | Social Anxiety Disorder (n=32) | mean=25.1, SD=9.1, range=18–60 | Sham training | 1280 (“low” dose) | 2x/week for 4 weeks | 4 weeks | Laboratory | Facial expressions (disgust and neutral) | LSAS-CR | 97% |

| (Heeren et al., 2012) | Social Anxiety Disorder (n=60) | mean=21.9, SD=3.1, range=18–35 | Sham training; Inverse training | 768 (“low” dose) | 1x/day for 4 days | 4 days | Laboratory | Facial expressions (disgust and happy) | LSAS-SR, pre-calculated AB scores (assessment) | 95% |

| (Maoz et al., 2013) | High Social Anxiety (n=51) | mean=22.7, SD=1.7, range=19–27 | Sham training [subliminal (17ms) presentations] | 640 (“low” dose) | 2x/week for 2 weeks | 2 weeks | Laboratory | Facial expressions (disgust and neutral) | LSAS-SR, raw AB data (assessment) | 100% |

| (McNally, Enock, Tsai, & Tousian, 2013) | High Social Anxiety (n=90) | mean=36.5, SD=13.6, range=18–65 | Sham training; Inverse training | 1536 (“high” dose) | 1–2x/week for 4 weeks | 4 weeks | Laboratory | Facial expressions (disgust and happy) | LSAS-SR, raw AB data (assessment) | 63% |

Note: ABM=Attention Bias Modification; AB=Attention Bias; LSAS=Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale; SR=self-report; CR=clinician-rated. All studies contributing data used a dot-probe task for ABM intervention.

N=number randomized.

Stimulus presentation times for ABM and control training were 500ms unless otherwise noted.

Study did not administer standard ABM away from threat. Data from sham and inverse training groups was used to aid power and precision of estimates for control conditions. No findings were altered excluding this study.

AB Assessment and Modification

In the dot-probe task, a widely-used reaction time (RT) measure of AB (MacLeod, Mathews, & Tata, 1986), two stimuli are presented simultaneously (one threat-related and one comparison—typically neutral or positive). After a specific interval (e.g., 500ms), both items are removed and a neutral ‘probe’ appears in one of the two locations. The probe (but not the neutral/threat images that preceded it) requires a response (e.g., indicate via button press whether the letter ‘E’ or ‘F’ is shown). In “incongruent” trials, the probe replaces the non-threat item in the pair, while in “congruent” trials, the probe replaces the threat item. AB towards threat is inferred when an individual’s mean RT to incongruent trials is longer than the mean RT to congruent trials, suggesting attention was more likely to be allocated towards the threat cue location at the moment the probe appeared.

All studies in the current analysis used a training variant of the dot-probe as the ABM intervention (MacLeod et al., 2002). Although this was not explicitly required by inclusion/exclusion criteria, the dot-probe approach to ABM has been predominant in the literature to date. Only 2 studies meeting most of the eligibility criteria were found during the literature review that used alternate automated training procedures, and these were excluded because they did not include a dot-probe assessment measure (prohibiting pooling with other studies to test primary hypotheses regarding AB).

In the ABM variant of the dot-probe, the probe replaces the less threatening item in the stimulus pair with greater likelihood than the threat-related item, systematically drawing attention away from threat. Typically, sessions are ≤20min and involve minimal-to-no contact with personnel. All contributing studies included a sham control group completing an identical task, except that there was no systematic contingency regarding the probe location (probes appeared with equal likelihood in the threat or non-threat location). A subset of studies included an additional control group: inverse training drawing attention towards threat (3 studies; see Table 1). The modal stimulus type was facial expressions, with only two exceptions (see Table 1). All but one study incorporated 500ms presentations (although two studies began with 1000ms presentations for the first half of each session), while a single study utilized subliminal (17ms) presentations (i.e., presentation times too brief to be consciously perceived).

Dosing

The Methods sections of contributing studies were reviewed by two independent raters in order to extract the total number of training trials/repetitions delivered across the course of all sessions in the experiment (i.e., number of training trials/session * total number of sessions; see Table 1). 100% inter-rater reliability was obtained. Within each study, dosing was always equivalent for the ABM and control conditions. Only per-protocol completers were included in analyses (94% of all randomized participants), ensuring all participants received the full intended dose. Due to the small number of studies and over-representation of studies using certain specific dosing parameters (e.g., 1280 trials; see Table 1), primary analyses used a dichotomized dosing variable based on a median split. Median splits are robust and can enhance power given an uneven, skewed, or suboptimal linear distribution, and also provide a parsimonious and readily interpretable cut-point for practical decision-making (Iacobucci, Posavac, Kardes, Schneider, & Popovich, 2015). Secondary analyses utilized continuous numerical dose values to assess for convergence of findings across analytic strategies.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were first conducted comparing ABM vs. all control conditions (collapsed into one group); follow-up analyses compared ABM to specific control conditions (sham and inverse training). Predictors were: treatment condition, dose (dichotomized or continuous), and their interaction. Outcomes were: post-training LSAS score (covarying pre-training LSAS) and post-training AB (covarying pre-training AB). One-step individual patient data analyses (Riley et al., 2008) were completed using linear mixed effects regression models, including a random study effect to account for clustering within study. Patient-level data was considered level 1 and study-level data was considered level 2. Analyses were performed using R version 3.1.

Results

ABM vs. all control groups

LSAS

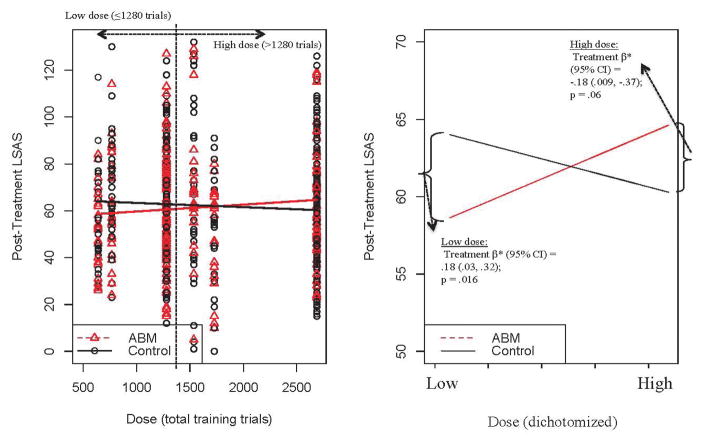

There was a significant moderating effect of dose [dichotomized as <=1280 trials, producing 7 “low dose” (N=348) and 4 “high dose” studies (N=345)] on post-training LSAS [dose*treatment β=8.75;p=.003]. A beneficial effect of ABM over control on post-training LSAS was observed in studies with a low-dose (treatment β=−8.41;p=.016), while in studies with a high-dose, there was a non-significant trend in favor of control (treatment β=4.37;p=.0626; Figure 1). This moderating effect was upheld in secondary analyses where total number of trials was included as a continuous measure (dose*treatment β=.0047;p=.030).

Figure 1.

Moderating effect of dose (total training trials) on Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (LSAS) scores. Left panel displays observed data points for continuous dose variable; right panel displays regression prediction lines and statistics for dichotomized (low vs. high) dose. Reported beta weights are standardized. Regression prediction lines based on models predicting LSAS post-training, controlling for baseline LSAS, with a random effect for study.

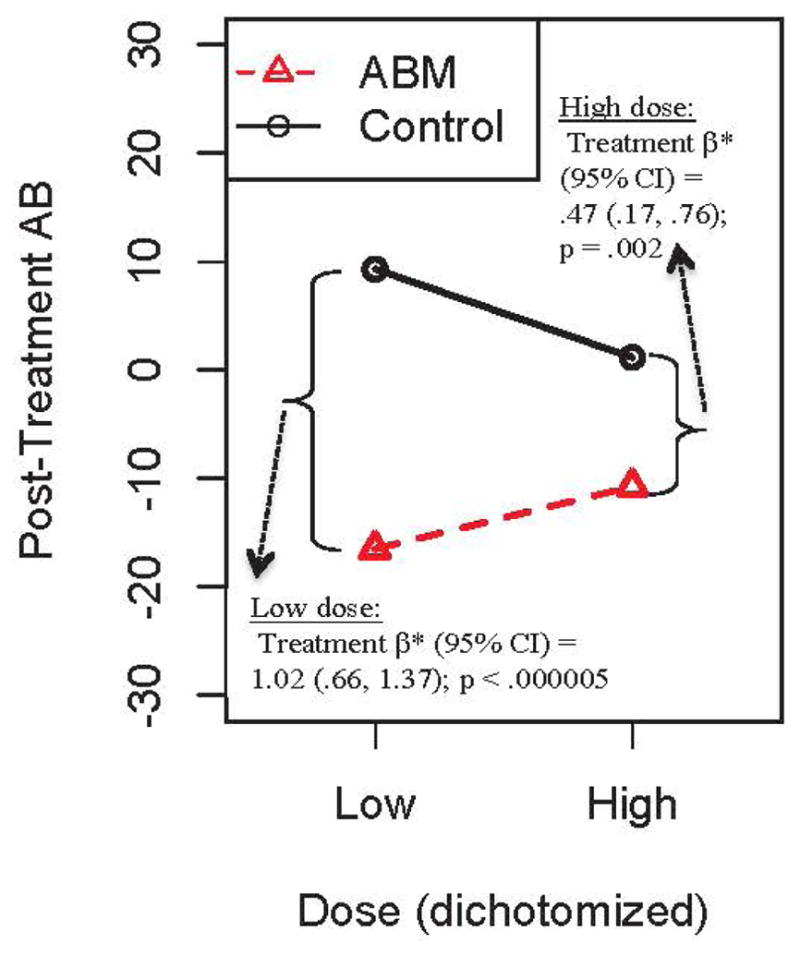

AB

There was a similar significant moderating effect of dose (dichotomized: 4 “low dose” (N=159) and 4 “high dose” studies (N=297)]) on post-training AB [dose*treatment β=13.90;p=.020; Figure 2]. Compared to control, ABM more robustly decreased AB across all studies [treatment β=−23.66;p<.00005], but the effect was stronger among studies with a low dose [treatment β=−25.80;p<.00005] than those with a high dose (treatment β=−11.90;p=.002). However, the moderating effect was not upheld treating dose as a continuous variable [dose*treatment β=0.002;p=.651].

Figure 2.

Moderating effect of dose (dichotomized as low vs. high) on attention bias (AB) scores. Reported beta weights are standardized. Regression prediction lines based on models predicting AB post-training, controlling for baseline AB, with a random effect for study.

Sensitivity analyses

ABM vs. specific control groups

Sensitivity analyses were conducted to assess whether observed dosing effects were influenced by the type of control group used (sham or inverse training). Moderating effects of dose (dichotomized) on LSAS were upheld for both comparisons of sham training vs. ABM (dose*treatment β=6.53;p=.0366) and comparisons of inverse training vs. ABM (dose*treatment β=23.09;p=.0001). Moderating effects of dose on AB were upheld in comparisons of inverse training vs. ABM (dose*treatment β=23.09;p<.00005) but not in comparisons of sham vs. ABM (dose*treatment β=7.56;p=.1644).

Alternative explanations/confounds

Table 2 shows that dose did not appear to be confounded with other possible explanatory variables, including other known moderators of post-training LSAS in this sample (Price, Wallace, et al., 2016). Furthermore, the significant dose*treatment interaction effect on LSAS was retained after controlling for main and moderating effects of the length of the pre-post assessment interval (dose*treatment:β=9.07;p=.0025) and three known moderators of post-training LSAS in this sample: age (dose*treatment:β=7.67;p=.0116), training location (dose*treatment:β=7.84;p=.0088), and LSAS rater (dose*treatment:β=8.80;p=.0030). Furthermore, when constricting the sample to studies that delivered ABM in the laboratory (n=7 studies)—a group of studies where significant main effects of ABM on the LSAS and AB were observed in our previous analyses—significant dose*treatment interaction effects were nevertheless retained for both LSAS (dose*treatment:β=13.76;p=.0011) and AB (dose*treatment:β=23.80;p=.0001).

Table 2.

Comparisons of high and low dose studies on possible other explanatory/confounding variables

| Variable | Low dose studies | High dose studies | Comparison statistic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-post assessment interval (weeks) | mean=3.22, SD=1.39, Nstudies=7 | mean=3.00, SD=1.15, Nstudies=4 | t9=.27, p=.79 |

| Age | mean=28.24, SD=6.65, Nstudies=7 | mean=32.91, SD=7.31, Nstudies=4 | t9=1.08, p=.31 |

| LSAS Rater (self-report vs. clinician) | Self-report: N=5/7 studies (71.4%) | Self-report: N=3/4 studies (75%) | χ2=.02, p=.90 |

| Training location (laboratory vs. home) | Laboratory: N=5/7 studies (71.4%) | Laboratory: N=2/4 studies (50%) | χ2=.51, p=.48 |

| Performance across all dot-probe assessment trials at post-treatment |

RT: mean=626.37ms, mean of within-subject SD=782.79ms Error rate: mean=2.6%, SD=1.2, Nstudies=3 |

RT: mean=621.10ms, mean of within-subject SD=181.28ms Error rate: mean=3.7%, SD=2.4, Nstudies=3 |

Mean RT: t4=0.12, p=.91 SD of RT: t4=1.04, p=.36 Mean error rate: t4=0.70, p=.52 |

Note: LSAS=Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale; RT=reaction time

In a subset of the data (n=327; 3 “high” and 3 “low” dose studies) where raw dot-probe performance data were available, we assessed whether moderating effects of dose might be explained by decreased motivation or increased fatigue at post-test (which could be amplified by increasing doses of preceding training trials/repetitions). For each participant at each assessment point (pre and post-test), this was quantified behaviorally across all dot-probe assessment trials as: overall mean RT, standard deviation of RT, and error rate. There was no evidence that training dose (dichotomized or continuous) was related to any of these performance/motivation indices, either at post-test (p’s>.36; (Table 2) or expressed as a change score from pre-to-post test (p’s>.293), and controlling for these performance variables did not alter the significance of any finding.

Studies with supraliminal presentation

Only one included study utilized subliminal presentation procedures (Maoz, Abend, Fox, Pine, & Bar-Haim, 2013), while all other studies used supraliminal (i.e., above the threshold for conscious perception) presentations. Excluding this study from analysis maintained or strengthened all reported findings (LSAS: dichotomized dose*treatment β=9.42;p=.003; continuous dose*treatment β=.0063;p=.01; AB: dichotomized dose*treatment β=44.32;p<.00005; continuous dose*treatment β=.013;p=.0042).

Discussion

Considerable research resources have been devoted over the last decade to the question of whether ABM, a low-cost, fully automated, mechanistic intervention has ameliorating effects on clinical anxiety. Previous metaanalyses, including those using the present dataset, have suggested that ABM is indeed an efficacious treatment (Heeren et al., 2015; Linetzky, Pergamin-Hight, Pine, & Bar-Haim, 2015; Price, Wallace, et al., 2016), yielding clinically significant improvements (e.g., remission of clinical diagnosis) in up to 35% of patients. However, effects are robust only when certain conditions are met, helping to explain notably mixed findings in the literature. The present analyses reveal, paradoxically, that one of the conditions promoting beneficial effects of ABM (apparent across both dichotomized and continuous analyses of dose) may be to restrict the total training trials administered to a relatively low dose (specifically, <=1280 repetitions over the course of the entire experiment). If confirmed in randomized studies holding all other variables constant, this finding would have immediate practical implications for researchers and clinicians interested in applying this specific form of ABM (the dot-probe task, which is widely used and publically available) to the problem of social anxiety, suggesting that ABM can be delivered extremely efficiently [i.e., in as few as 768 trials delivered over 4 consecutive days (Heeren, Reese, McNally, & Philippot, 2012)] without sacrificing clinical potency. However, it is important to note that all included studies offered repeated sessions of training, whereas previous meta-analyses have suggested that single-session training protocols are less effective (Beard et al., 2012; Hallion & Ruscio, 2011), potentially due to the lack of critical between-session consolidation effects (Abend et al., 2013; Abend et al., 2014). The field has been previously left in the dark with respect to proper empirical guidance for this type of very basic intervention design decision. The counter-intuitive nature of the present findings suggests intuition may not be an adequate guide for such decision-making, and strongly suggests the need for empirically derived guidelines.

Findings further suggest several avenues for continuing to refine and improve upon ABM’s effects. One possible explanation for the observed pattern is that a larger dose of control conditions—which match active ABM on many salient features (e.g., repeated exposure to threat stimuli; completion of a cognitive task that encourages flexible or attentional allocation)—might have exhibited larger effects at higher doses, washing out effects of ABM in comparison to control. Indeed, these control conditions have sometimes been suggested to constitute useful training interventions themselves (Badura-Brack et al., 2015; Boettcher et al., 2013) via similar, but not identical, mechanisms—e.g., flexible attentional allocation in the context of threat, decreased avoidance of threat. However, here, the data suggested that ABM itself was also less beneficial in studies delivering a larger number of trials (Figure 1). The dosing effect did not appear to be due to differential passage of time, as the total duration of the experiments (i.e. the pre-post assessment interval) was orthogonal to dose (Table 1) and did not reduce the effect when included as a covariate. Nor was there evidence that greater training doses increased fatigue or lowered task motivation (see Sensitivity Analyses). Thus, it may be that there is a ‘sweet spot’ for the number of repetitions of the ABM paradigm that produces a clinically beneficial effect, potentially consistent with well-established findings in the perceptual discrimination literature which suggest that over-repetition can become detrimental to learning (Harris, Gliksberg, & Sagi, 2012; Mednick, Arman, & Boynton, 2005). Furthermore, excessive repetition of a task that encourages constant avoidance of threat (i.e., attentional allocation away from threat) might ‘over-correct’ patterns of vigilance towards threat, paradoxically encouraging attentional rigidity, thereby reversing any beneficial effect that a lower, ‘weaker’ dose would have had. This suggestion is consistent with the notion that rigid attentional preferences in either direction (towards or away from threat) may be detrimental (e.g., Price, Rosen, et al., 2015), while the ability to flexibly allocate attention (e.g., based on context, current demands and goals) (Badura-Brack et al., 2015; Price et al., 2013) may represent an optimal cognitive state. Possibly, ABM might best achieve such flexibility with a smaller number of trials, when rigid patterns of vigilance to threat have just begun to shift, but prior to the firm instantiation of a new, rigid pattern of allocating attention away from threat. Novel training paradigms could be designed to increase flexibility itself, e.g., through alternating trials or blocks of training either towards or away from threat, or through feedback-based attentional conditioning paradigms (Price, Greven, Siegle, Koster, & De Raedt, 2016) that could be designed to operationalize a goal state of attentional flexibility.

A metaanalytic approach cannot conclusively rule out alternative study-level parameters that may have covaried with dosing and explain the observed effect, given that dosing decisions will necessarily be made in the context of numerous other procedural variables that vary across studies. However, the effect on social anxiety was robust after controlling for previously identified moderators (participant age, training setting, LSAS rater) and for pre-post assessment interval and motivation/fatigue-related behavioral indices, and dose did not appear to be confounded with these variables (Table 2). Furthermore, the effect was present even among laboratory-based studies alone, a subset of ABM studies that has consistently shown robust clinical effects in meta-analyses (Heeren et al., 2015; Linetzky et al., 2015; Mogoaşe et al., 2014; Price, Wallace, et al., 2016). Our findings stand in contrast to one previous, standard (study-level) metaanalysis in social anxiety (Heeren et al., 2015), where significant moderating effects of dose on clinical anxiety symptoms could not be established. Furthermore, in a subset of previous metaanalyses, an increasing number of sessions/visits (Hakamata et al., 2010) or training trials within each session (but conversely, not the number of sessions) (Heeren et al., 2015) were associated with a larger decrease in AB following ABM. The most salient distinction is our use of raw patient-level and trial-level data, enabling standardized scoring and outlier rescaling procedures, previously shown to improve reliability (Price, Kuckertz, et al., 2015), to be applied to quantify AB levels based on a uniform task (the dot-probe task), and enabling individual differences in LSAS and AB trajectories (one per participant) to be modeled rather than relying on group means and effect sizes (one per study) to represent all individuals in a given study. We also captured dose both within and across sessions concurrently by quantifying the total number of training trials delivered across all sessions. In light of our findings and these discrepancies within the literature, future dose-response studies, holding all other parameters constant, are urgently needed to conclusively delineate the impact of dosing.

Limitations

We were constrained by certain aspects of the available published datasets, including lack of follow-up data and poor reliability of reaction time measurements of AB, even when methods to improve stability are applied (Price, Kuckertz, et al., 2015). Effect sizes were small, suggesting substantial variability in outcomes remained unexplained by the examined moderator, although moderators collectively identified across this and previous examinations (Price, Wallace, et al., 2016) may help to define a combination of relatively independent factors that together promote greater intervention benefit. Though the present pooled dataset represents a 10-fold increase in sample size over the mean of previously published ABM trials, the number of contributing studies, and hence the variability in dosing across studies, was limited. Present findings await verification in dosing studies holding all study parameters (other than dose) constant.

Conclusions

ABM has shown promise as a fully automated intervention for anxiety, but mixed findings have prompted considerable debate, suggesting that procedures must be iteratively refined in order to produce reliable clinical potential. Here we report paradoxical effects of one fundamental, yet poorly understood, factor—the dose (number of training trials) administered. The clinical significance of ABM shows much room for improvement (Price, Wallace, et al., 2016). Further attention to the role of dosing may help to optimize its potential, and to clarify the precise attentional mechanisms (e.g., flexibility vs. rigidity) that account for its effects.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Dr. Amir was formerly a part owner of Cognitive Retraining Technologies, LLC (“CRT”), a company that marketed computer-based anxiety relief products similar to those studied here. Dr. Amir’s ownership interest in CRT was extinguished on January 29, 2016, when CRT was acquired by another entity. Dr. Amir has an interest in royalty income generated by the marketing of anxiety relief products by this entity. All other authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Authors supported by National Institute of Mental Health Career Development grants K23MH100259 (RBP) and K01MH096944 (MW). We gratefully acknowledge Johanna Boettcher, Jennifer Britton, Brian Bunnell, Sharon Eldar, Angela Fang, Phil Enock, Alexandre Heeren, Keren Maoz, Richard McNally, and Alice Ty Sawyer for providing data used in these analyses.

Footnotes

Dr. Amir was formerly a part owner of Cognitive Retraining Technologies, LLC (“CRT”), a company that marketed computer-based anxiety relief products similar to those studied here. Dr. Amir’s ownership interest in CRT was extinguished on January 29, 2016, when CRT was acquired by another entity. Dr. Amir has an interest in royalty income generated by the marketing of anxiety relief products by this entity. All other authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abend R, Karni A, Sadeh A, Fox NA, Pine DS, Bar-Haim Y. Learning to attend to threat accelerates and enhances memory consolidation. PloS one. 2013;8(4):e62501. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abend R, Pine DS, Fox NA, Bar-Haim Y. Learning and memory consolidation processes of attention-bias modification in anxious and nonanxious individuals. Clinical Psychological Science. 2014;2(5):620–627. [Google Scholar]

- Amir N, Beard C, Burns M, Bomyea J. Attention modification program in individuals with generalized anxiety disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2009;118:28–33. doi: 10.1037/a0012589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amir N, Beard C, Taylor CT, Klumpp H, Elias J, Burns M, et al. Attention training in individuals with generalized social phobia: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77(5):961–973. doi: 10.1037/a0016685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badura-Brack AS, Naim R, Ryan TJ, Levy O, Abend R, Khanna MM, et al. Effect of attention training on attention bias variability and PTSD Symptoms: Randomized controlled trials in Israeli and U.S. combat veterans. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2015;172(12):1233–1241. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.14121578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Haim Y, Lamy D, Pergamin L, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van IJzendoorn MH. Threat-related attentional bias in anxious and nonanxious individuals: a meta-analytic study. Psychological Bulletin. 2007;133(1):1–24. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beard C, Sawyer AT, Hofmann SG. Efficacy of attention bias modification using threat and appetitive stimuli: a meta-analytic review. Behavior Therapy. 2012;43(4):724–740. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2012.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boettcher J, Berger T, Renneberg B. Internet-based attention training for social anxiety: A randomized controlled trial. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2012;36:522–536. [Google Scholar]

- Boettcher J, Hasselrot J, Sund E, Andersson G, Carlbring P. Combining attention training with internet-based cognitive-behavioural self-help for social anxiety: A randomised controlled trial. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. 2014;43(1):34–48. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2013.809141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boettcher J, Leek L, Matson L, Holmes EA, Browning M, MacLeod C, et al. Internet-based attention bias modification for social anxiety: A randomised controlled comparison of training towards negative and training towards positive cues. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(9):e71760. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britton J, Suway J, Clementi M, Fox N, Pine D, Bar-Haim Y. Neural changes with attention bias modification for anxiety: a randomized trial. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2015;10(7):913–920. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsu141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunnell BE, Beidel DC, Mesa F. A randomized trial of attention training for generalized social phobia: Does attention training change social behavior? Behavior Therapy. 2013;44(4):662–673. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2013.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calitri R, Pothos EM, Tapper K, Brunstrom JM, Rogers PJ. Cognitive biases to healthy and unhealthy food words predict change in BMI. Obesity. 2010;18(12):2282–2287. doi: 10.1038/oby.2010.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlbring P, Apelstrand M, Sehlin H, Amir N, Rousseau A, Hofmann SG, et al. Internet-delivered attention bias modification training in individuals with social anxiety disorder - A double blind randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12(1):66. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-12-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cha CB, Najmi S, Park JM, Finn CT, Nock MK. Attentional bias toward suicide-related stimuli predicts suicidal behavior. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2010;119(3):616–622. doi: 10.1037/a0019710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke PJ, Notebaert L, Macleod C. Absence of evidence or evidence of absence: reflecting on therapeutic implementations of attentional bias modification. BioMed Central Psychiatry. 2014;14(1):8. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-14-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cristea IA, Kok RN, Cuijpers P. Efficacy of cognitive bias modification interventions in anxiety and depression: meta-analysis. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2015;206(1):7–16. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.114.146761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang A, Sawyer A, Aderka I, Hofmann S. Psychological treatment of social anxiety disorder improves body dysmorphic concerns. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2013;27(7):684–691. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2013.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fresco DM, Coles ME, Heimberg RG, Liebowitz MR, Hami S, Stein MB, et al. The Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale: a comparison of the psychometric properties of self-report and clinician-administered formats. Psychological Medicine. 2001;31(6):1025–1035. doi: 10.1017/s0033291701004056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakamata Y, Lissek S, Bar-Haim Y, Britton JC, Fox Na, Leibenluft E, et al. Attention bias modification treatment: a meta-analysis toward the establishment of novel treatment for anxiety. Biological Psychiatry. 2010;68:982–990. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallion LS, Ruscio AM. A meta-analysis of the effect of cognitive bias modification on anxiety and depression. Psychological Bulletin. 2011;137(6):940–958. doi: 10.1037/a0024355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmer CJ, Goodwin GM, Cowen PJ. Why do antidepressants take so long to work? A cognitive neuropsychological model of antidepressant drug action. The British journal of psychiatry : the journal of mental science. 2009;195:102–108. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.051193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris H, Gliksberg M, Sagi D. Generalized perceptual learning in the absence of sensory adaptation. Current Biology. 2012;22(19):1813–1817. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.07.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heeren A, Mogoase C, Philippot P, McNally RJ. Attention bias modification for social anxiety: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review. 2015;40:76–90. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heeren A, Reese HE, McNally RJ, Philippot P. Attention training toward and away from threat in social phobia: effects on subjective, behavioral, and physiological measures of anxiety. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2012;50:30–39. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2011.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacobucci D, Posavac SS, Kardes FR, Schneider MJ, Popovich DL. Toward a more nuanced understanding of the statistical properties of a median split. Journal of Consumer Psychology. 2015;25(4):652–665. [Google Scholar]

- Linetzky M, Pergamin-Hight L, Pine DS, Bar-Haim Y. Quantitative evaluation of the clinical efficacy of attention bias modification treatment for anxiety disorders. Depression and Anxiety. 2015;32(6):383–391. doi: 10.1002/da.22344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod C, Clarke PJF. The attentional bias modification approach to anxiety intervention. Clinical Psychological Science. 2015;3(1):58–78. [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod C, Mathews A, Tata P. Attentional bias in emotional disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1986;95(1):15–20. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.95.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod C, Rutherford E, Campbell L, Ebsworthy G, Holker L. Selective attention and emotional vulnerability: assessing the causal basis of their association through the experimental manipulation of attentional bias. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111(1):107–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maoz K, Abend R, Fox NA, Pine DS, Bar-Haim Y. Subliminal attention bias modification training in socially anxious individuals. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 2013;7:389. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2013.00389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNally RJ, Enock PM, Tsai C, Tousian M. Attention bias modification for reducing speech anxiety. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2013;51(12):882–888. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2013.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mednick SC, Arman AC, Boynton GM. The time course and specificity of perceptual deterioration. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2005;102(10):3881–3885. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407866102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mogoaşe C, David D, Koster EHW. Clinical efficacy of attentional bias modification procedures: An updated meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2014;70(12):1133–1157. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohlman J, Price RB, Vietri J. Attentional bias in older adults : Effects of generalized anxiety disorder and cognitive behavior therapy. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2013;27:585–591. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2013.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr DC, Burns MN, Schueller SM, Clarke G, Klinkman M. Behavioral intervention technologies: evidence review and recommendations for future research in mental health. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2013;35(4):332–338. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2013.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naim R, Wald I, Lior A, Pine DS, Fox NA, Sheppes G, et al. Perturbed threat monitoring following a traumatic event predicts risk for post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychological medicine. 2014;44(10):2077–2084. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713002456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peckham AD, McHugh RK, Otto MW. A meta-analysis of the magnitude of biased attention in depression. Depression and Anxiety. 2010;27(12):1135–1142. doi: 10.1002/da.20755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price RB, Greven IM, Siegle GJ, Koster EH, De Raedt R. A novel attention training paradigm based on operant conditioning of eye gaze: Preliminary findings. Emotion. 2016;16(1):110–116. doi: 10.1037/emo0000093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price RB, Kuckertz JM, Siegle GJ, Ladouceur CD, Silk JS, Ryan ND, et al. Empirical recommendations for improving the stability of the dot-probe task in clinical research. Psychological Assessment. 2015;27(2):365–376. doi: 10.1037/pas0000036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price RB, Rosen D, Siegle GJ, Ladouceur CD, Tang K, Allen KB, et al. From anxious youth to depressed adolescents: Prospective prediction of 2-year depression symptoms via attentional bias measures. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2015;125(2):267–278. doi: 10.1037/abn0000127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price RB, Siegle G, Mohlman J. Emotional Stroop performance in older adults: Effects of habitual worry. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2012;20(9):798–805. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e318230340d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price RB, Siegle G, Silk JS, Ladouceur CD, McFarland A, Dahl RE, et al. Sustained neural alterations in anxious youth performing an attentional bias task: A pupilometry study. Depression and Anxiety. 2013;30:22–30. doi: 10.1002/da.21966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price RB, Wallace M, Kuckertz JM, Amir N, Graur S, Cummings L, et al. Pooled patient-level metaanalysis of children and adults completing a computer-based anxiety intervention targeting attentional bias. Clinical Psychology Review. 2016;50:37–49. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2016.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley RD, Lambert PC, Abo-Zaid G. Meta-analysis of individual participant data: rationale, conduct, and reporting. British Journal of Medicine. 2010;340:c221. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley RD, Lambert PC, Staessen JA, Wang J, Gueyffier F, Thijs L, et al. Meta-analysis of continuous outcomes combining individual patient data and aggregate data. Statistics in Medicine. 2008;27(11):1870–1893. doi: 10.1002/sim.3165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith P, Waterman M. Processing bias for sexual material: the emotional stroop and sexual offenders. Sex Abuse. 2004;16(2):163–171. doi: 10.1177/107906320401600206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters AJ, Marhe R, Franken IH. Attentional bias to drug cues is elevated before and during temptations to use heroin and cocaine. Psychopharmacology (Berlin) 2012;219(3):909–921. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2424-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.