Abstract

Pancreatic-type ribonucleases (ptRNases) comprise a class of highly conserved secretory endoribonucleases in vertebrates. The prototype of this enzyme family is ribonuclease 1 (RNase 1). Understanding the physiological roles of RNase 1 is becoming increasingly important, as engineered forms of the enzyme progress through clinical trials as chemotherapeutic agents for cancer. Here we present an in-depth biochemical characterization of RNase 1 homologs from a broad range of mammals (human, bat, squirrel, horse, cat, mouse, and cow) and non-mammalian species (chicken, lizard, and frog). We discover that the human homolog of RNase 1 has a pH optimum for catalysis, ability to degrade double-stranded RNA, and affinity for cell-surface glycans that are distinctly higher than those of its homologs. These attributes have relevance for human health. Moreover, the functional diversification of the ten RNase 1 homologs illuminates the regulation of extracellular RNA and other aspects of vertebrate evolution.

Keywords: enzyme, exRNA, glycosaminoglycan, molecular evolution, ribonuclease A

Introduction

Vertebrate animals possess a distinct, conserved family of secreted ribonucleases (RNases) not known to occur in any other taxon. This unique group of enzymes is termed the pancreatic-type RNases (ptRNases) or, alternatively, the vertebrate secretory RNases. They are not homologous to any other class of eukaryotic RNases, and together constitute an extensive superfamily of proteins that has been the subject of intense biochemical, structural, and evolutionary studies for over half a century. With compact structures, high stability, and a shared ability to catalyze the non-specific degradation of RNA, these small and hardy enzymes are purported to serve a variety of diverse biological roles in vivo, including supporting host defense and innate immunity [1, 2]. Indeed, numerous phylogenetic reconstructions and other analyses indicate that the family is evolving and expanding rapidly, and that many members are under positive selection for increased functional diversification, as is common with immunity-related protein families [3-6]. The various activities of ptRNases are regulated by the cytosolic ribonuclease inhibitor (RI) protein, which is conserved across various species and can bind extremely tightly to ptRNases, inhibiting their catalytic activity [7, 8].

The most well-known member of the ptRNase family is RNase 1. (Cow RNase 1 is also known as RNase A, and has served as a model protein for countless advances in biological chemistry [9-11].) Of all the ptRNases, RNase 1 has the highest catalytic activity, as well as the most diverse and robust expression [1, 12]. In addition to its broad tissue expression, RNase 1 has been isolated from a large variety of bodily fluids [12, 13]. In humans and mice, RNase 1 circulates freely in the blood and serum at a concentration of ∼0.5 μg/mL, and is the only known ribonuclease in plasma with high, nonspecific ribonucleolytic activity [14-17]. Secreted RNase 1 also possesses the ability to enter the cytosol of other cells via endocytosis and translocation. This remarkable ability has been exploited to create variants of RNase 1 that can act as chemotherapeutic agents against cancer cells [8, 18-20], including prototypes now in clinical trials [21, 22].

Despite its widespread conservation in mammals and unique properties, the biological role of RNase 1 is poorly understood. Due to the high level of expression of RNase A in the cow pancreas, RNase 1 was historically known as a digestive enzyme and was thought to serve little purpose in non-ruminant mammals, including humans [23]. That impression began to change as studies compiled diverse data suggesting a non-digestive role for RNase 1 in species apart from cattle [24-26]. Correspondingly, phylogenetic analyses have predicted that RNase A diverged relatively recently through gene duplication in ruminants, and might represent a specialized digestive form of the RNase 1 enzyme that arose simultaneously with foregut fermentation [27, 28]. Intriguingly, cattle express two other RNase 1 paralogs, which have been shown to have properties distinct from that of RNase A [29, 30]. A similar phenomenon is known to have occurred in leaf-eating monkeys, where a secondary form of RNase 1 evolved to participate in ruminant-like digestion [31]. Analogously, modern whales and dolphins, which share a common ancestor with cattle, seemingly lost their extra copies of RNase 1 concurrent to switching from a herbivorous to a carnivorous diet [32]. Taken together, extant evidence suggests that cow RNase A—the original so-called “pancreatic ribonuclease”—might be a functional outlier among RNase 1 homologs, with the true physiological role of RNase 1 in other vertebrates still to be unveiled.

Previous functional studies of RNase 1 enzyme homologs have uncovered biochemical differences across a limited subset of species [27, 30, 31, 33]. Broader functional differences across species have been predicted through phylogenetic analyses of RNase1 genes. For example, RNase1 gene duplication events and differential selection pressures have been uncovered in rodent, carnivore, and bat families, suggesting that new functional roles may be emerging [34-37]. Nonetheless, knowledge of the actual behavior of the RNase 1 enzyme from diverse species represents a critical gap in our understanding of RNase 1 biology.

Comparative functional analyses can illuminate conserved or derived protein functions [38-41]. Such analyses, which bridge the divide between structural biology, biochemistry, and molecular evolution, are critical for advancing our understanding of RNase 1. Here we present the broadest and most in-depth study to date of the function of RNase 1 proteins across a vertebrate evolutionary spectrum, including seven mammalian homologs and three non-mammalian homologs. We build upon an existing framework of phylogenetic analyses by probing the functional diversification of these homologs, as well as speculate on key amino acid changes that might have led to pronounced differences in both biochemical properties and biological function.

Materials and methods

Materials and instrumentation

E. coli BL21(DE3) cells and plasmid pET22b(+) were from EMD Millipore. 6‐FAM–dArUdAdA–6-TAMRA, 5,6-FAM–d(CGATC)(rU)d(ACTGCAACGGCAGTAGATCG), and DNA oligonucleotides for PCR, sequencing, and mutagenesis were from Integrated DNA Technologies. Poly(A:U) was from Sigma Chemical; low-molecular-weight poly(I:C) was from InvivoGen. Sulfatides, phosphatidylserine, and cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) were from Avanti Polar Lipids.

Protein purification columns were from GE Healthcare. Restriction and PCR enzymes were from Promega. 96-Well plates were from Corning. 2-(N-Morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid (MES) was purified to be free of oligo(vinylsulfonic acid) [42]. All other chemicals were of commercial grade or better, and were used without further purification.

The molecular mass of each ribonuclease was determined by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-time-of-flight (MALDI–TOF) mass spectrometry with a Voyager-DE-PRO Biospectrometry Workstation from Applied Biosystems at the campus Biophysics Instrumentation Facility. All fluorescence and absorbance measurements were made with a M1000 fluorimeter plate reader from Tecan, unless stated otherwise. All data were fitted and analyzed using Prism 5 software from GraphPad, unless stated otherwise.

Ribonuclease cloning and purification

Genes encoding human RNase 1 [43], cow RNase 1 [43], mouse RNase 1 [8], chicken RNase A-1 [8], anole RNase [8], and frog RNase [44] had been inserted previously into the pET22b expression vector for tagless expression in BL21(DE3) E. coli. A gene encoding bat RNase 1 (GenBank Accession No. AEF13449) was amplified from little brown bat (Myotis lucifugus) skin cDNA and inserted into pET22b. Genes encoding cat RNase 1 (GenBank Accession No. XP_003987441) and horse RNase 1 (GenBank Accession No. NP_001296341) were, respectively, amplified from cat and horse liver cDNA libraries (Zyagen Life Sciences) and inserted in pET22b. A gene encoding squirrel RNase 1 (GenBank Accession No. ACV70066) was amplified from Scurius carolinensis liver cDNA and inserted into pET22b. The program Signal P was used to predict and exclude peptide leader sequences for all proteins. The nucleotide sequence for each primer used for cloning is listed in Supplementary Table S1.

To enable site-specific fluorophore-labeling of the RNase 1 homologs, cysteine residues were introduced via site-directed mutagenesis into loop regions distal to the enzymic active site. The ensuing variants were P19C human RNase 1, S19C mouse RNase 1, A19C cow RNase 1, S19C horse RNase 1, T18C cat RNase 1, P18C bat RNase 1, S19C squirrel RNase 1, T17C chicken RNase A-1, S20C anole RNase 1, and S61C frog RNase. Recombinant wild-type ptRNases and their variants were purified as inclusion bodies from E. coli, and free-cysteine protein variants were labeled with BODIPY FL (Molecular Probes) as described previously [45, 46]. Following purification, protein solutions were dialyzed against PBS and filtered prior to use. The molecular masses of ribonuclease conjugates were confirmed by MALDI–TOF mass spectrometry. Protein concentration was determined by using a bicinchoninic acid assay kit (Pierce) with wild-type RNase A as a standard.

Thermostability measurements

The thermal denaturation of RNase 1 homologs was monitored in the presence of a fluorescent dye using differential scanning fluorimetry (DSF). DSF was performed using a ViiA 7 Real-Time PCR machine (Applied Biosystems) as described previously [47, 48]. Briefly, a solution of protein (30 μg) was placed in the wells of a MicroAmp optical 96-well plate, and SYPRO Orange dye (Sigma Chemical) was added to a final dye dilution of 1:166 in relation to the stock solution of the manufacturer. The temperature was increased from 20°C to 96°C at 1°C/min in steps of 1°C. Fluorescence intensity was measured at 578 nm, and a solution with no protein was used for background correction. Values of Tm were calculated by fitting the ∂fluorescence/∂T data to a two-state Boltzmann model with Protein Thermal Shift software (Applied Biosystems).

pH-Dependence of enzyme activity against ssRNA

The pH dependence of kcat/KM for the cleavage of ssRNA by RNase 1 homologs was determined with a fluorogenic substrate in which a single ribonucleotide residue was embedded in a DNA oligonucleotide with a fluorophore at its 5′ terminus and a quencher at its 3′ terminus: 6-FAM–dArUdAdA–6-TAMRA [49]. Assays were performed at 25 °C in solutions of an RNase 1 and 6‐FAM–dArUdAdA–6-TAMRA (0.2 μM) in a ribonuclease-free buffer: 0.10 M NaOAc, 0.10 M NaCl (pH 4.0–5.5); 0.10 M Bis–Tris, 0.10 M NaCl (pH 6.0–6.5); 0.10 M Tris, 0.10 M NaCl (pH 7.0–9.0). All assays were performed in triplicate with three different enzyme preparations. Values of optimal pH were calculated by fitting of normalized initial velocity data from solutions of various pH to a bell-shaped distribution. Values of kcat/KM at the optimal pH were determined from initial velocity data, as described previously [49].

Degradation of double-stranded RNA

The value of kcat/KM for the cleavage of a double-stranded (ds)RNA by RNase 1 homologs was determined with polymeric substrates by UV spectroscopy, as described previously [33]. Briefly, poly(A:U) (Sigma Chemical) and low molecular weight poly(I:C) (InvivoGen) were dissolved in H2O to a concentration of 20 mg/mL. Prior to use, 25 μL of a poly(A:U) or poly(I:C) solution was added to 0.50 mL of 0.10 M MES–HCl buffer, pH 7.4, containing NaCl (0.10 M). The resulting solution was added to the wells of a 96-well plate in twofold serial dilutions. After equilibration at 25°C, a baseline at A260 was established, and the initial substrate concentration was determined by using ε260 nm = 6.5 mM–1cm–1 for poly(A:U) and ε260 nm = 4.4 mM–1cm–1 for poly(I:C). Ribonucleases were added to the wells, and the change in absorbance at 260 nm was monitored over time. Initial reaction velocities were determined by using Δε260 nm = 3.4 mM‐1cm‐1 for poly(A:U) and Δε260 nm = 1.8 mM–1cm–1 for poly(I:C). All assays were performed in triplicate with three different enzyme preparations. Values of kcat/KM were calculated by fitting data to the Michaelis–Menten equation.

The degradation of dsRNA was also assessed with a well-defined substrate, as described previously [30]. As in the ssRNA substrate, a single ribonucleotide residue was embedded in a DNA oligonucleotide with a fluorophore at its 5′ terminus: 5,6-FAM–d(CGATC)(rU)d(ACTGCAACGGCAGTAGATCG). Briefly, the substrate was dissolved in water and allowed to form a hairpin by heating to 95°C and then cooling slowly to room temperature. Assay solutions contained a ribonuclease (1.0 μM) and substrate (50 nM) in 0.10 M MES–HCl buffer, pH 7.4, containing NaCl (0.10 M). Reactions were allowed to proceed for 5 min at 25°C. Reactions were quenched by the addition of 40 units of rRNasin (Promega), and products were subjected to electrophoresis at 10 mAmp on a native polyacrylamide (20% w/v) gel. The formation of cleavage product was measured by excitation of FAM at 495 nm and emission at 515 nm with a Typhoon FLA 9000 scanner (GE Healthcare). Band density was quantified from FAM fluorescence with ImageQuant software (GE Healthcare). The gel was then incubated in SYBR Gold stain (Invitrogen) and imaged for total nucleic acid. All assays were performed in triplicate with three different enzyme preparations.

Native gel-shift analysis of RI·RNase complexes

Human RI and various ribonucleases from endogenous species were incubated in a 1:1.2 molar ratio in PBS at 25°C for 20 min to allow for complex formation. A 10-μL aliquot of protein solution was combined with 2 μL of a 6× loading dye, and the resulting mixtures were loaded immediately onto a non-denaturing 12% w/v polyacrylamide gel (BioRad). Gels were run in the absence of SDS at 20–25 mA for ∼3 h at 4°C and stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250 dye (Sigma Chemical).

Cellular internalization of ribonucleases

The uptake of RNase 1 homologs by mammalian cells was monitored by flow cytometry, as described previously [45]. Human K-562 cells were grown in RPMI medium (Invitrogen) containing fetal bovine serum (10% v/v) and pen/strep (Invitrogen). Cells were maintained at 37°C under 5% v/v CO2(g). Cells were plated at 2 × 106 cells/mL in a 96-well plate. RNase 1–BODIPY conjugates in PBS were added to a concentration of 5 μM, and the resulting solutions were incubated for 4 h. Cells were collected by centrifugation at 1000 rpm for 5 min, washed twice with PBS, exchanged into fresh medium, and collected on ice. The total fluorescence of live cells was measured with a FacsCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). Fluorescence data between experiments were normalized by calibrating each run with fluorescent beads and subtracting the background fluorescence upon treatment with PBS lacking an RNase 1 homolog. Data were analyzed with FlowJo software (Tree Star).

Binding of ribonucleases to cell-surface glycans

The affinity of RNase 1 homologs for mammalian cell-surface glycans was assessed with fluorescence polarization, as described previously [30]. Briefly, solutions of heparin, chondroitin sulfate A, and chondroitin sulfate C in PBS, pH 7.4, were added to the wells of a 96-well plate in 5-fold serial dilutions. RNase 1–BODIPY conjugates were added to a concentration of 50 nM, and the resulting solutions were incubated for 30 min at room temperature to achieve equilibrium. Fluorescence polarization was monitored by excitation at 470 nm and emission at 535 nm, and data were normalized to a solution lacking glycan and fitted by nonlinear regression to the equation:

| (1) |

where B is the normalized fluorescence, Bmax is the maximum fluorescence, and h is a Hill coefficient.

1H,15N-HSQC NMR spectroscopy with RNase 1

[15N]-RNase 1 was produced in Escherichia coli as described previously, using a double-growth procedure in minimal medium containing [15N]-NH4Cl after induction with IPTG [50]. Growth conditions yielded an average of 15 mg of RNase 1 from 1 L of medium. Protein purification was monitored by using SDS–PAGE, and purified protein was analyzed by mass spectrometry using an Applied Biosystems/MDS SCIEX 4800 MALDI TOF/TOF instrument. The observed mass of 14790.1 Da indicated that isotope incorporation had been 100% × (14790 – 14,604)/192 = 97%.

1H,15N-HSQC NMR spectroscopy [51] was performed on 600 μL of 100 mM KH2PO4 buffer, pH 6.5 or pH 4.7, containing [15N]-RNase 1 (250 μM), D2O (10% v/v), and a molar equivalent of sulfatides, which mimic heparan sulfate (HS; pH 6.5), or phosphatidylserine (PS; pH 4.7) within CTAB micelles (25 mM). NMR spectra were acquired at 25°C with a Bruker Avance III 600 MHz spectrometer. 1H,15N-HSQC NMR data were quantified and peak assignments were made with the program Sparky 3 (T. D. Goddard and D. G. Kneller, University of California, San Francisco) using the assignments determined from the solution structure of RNase 1 [52]. The vector changes of chemical shift (ΔΔδ) were determined with the equation:

| (2) |

where 1H and 15N chemical shifts (Δδ) were the peak chemical shifts of [15N]-RNase 1 in the presence minus the absence of HS or PS.

Sequence alignment and phylogenetic analyses

Protein sequence alignments were made with the program MUSCLE [53] with manual adjustments. A neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree based on amino acid sequences was generated in MEGA6 using the Jones–Taylor–Thornton (JTT) substitution model with a discrete Gamma (+G) distribution to model evolutionary rate differences among sites [54] and 1000 bootstrap replicates [55]. The evolutionary model (JTT+G) was inferred according to the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) statistics obtained with the jModelTest program run with MEGA6 software.

The evolutionary rate of each site in the aligned amino acid sequences of 30 RNase 1 homologs [55] was also calculated with MEGA6 software and the JTT+G evolutionary model. (For a list of GenBank Accession numbers, see: Supplementary Table S2.) The calculated rates were scaled such that the average evolutionary rate across all sites was 1. Hence, sites with a rate <1 are evolving slower than average, and sites with a rate >1 are evolving faster than average. To visualize these evolutionary rates in the context of protein structure, an image of PDB entry 1z7x for human RNase 1 [56] was created with the program PyMOL (Schrödinger) in which the evolutionary rate of each residue was inserted as its β-factor.

Results

For our analysis, we chose ten RNase 1 homologs that span the vertebrate subphylum. These ten include four mammalian homologs that had not been studied previously (bat, cat, horse, and squirrel). We cloned genes encoding these ten ribonucleases, expressed these genes in Escherichia coli, and purified the ensuing ribonucleases to >99% purity (Supplementary Figure S1A). All of the RNase 1 homologs share a small size, net positive charge, and high thermostability (Supplementary Table S3). Additionally, we found that the four novel mammalian RNase 1 homologs used in this study bind tightly to the mammalian ribonuclease inhibitor protein (Supplementary Figure S1B), in accord with homologs characterized previously [43, 8].

RNase 1 homologs exhibit pronounced differences in catalysis

We sought to probe properties of enzymatic function. Previous studies have shown that homologous ribonucleases can exhibit different pH optima for catalysis, and such differences can provide clues regarding biological localization and function [30, 31]. We found similar distinctions. Using a small fluorogenic substrate that enables a continuous assay of single-stranded (ss)RNA hydrolysis, we established a pH–rate profile for each enzyme (Supplementary Figure S2). We found that cow RNase 1 manifested the highest catalytic activity, but did so at the lowest pH optimum (6.1). Other mammalian homologs demonstrated a range of increasingly lower enzymatic activities at increasingly higher pH optima. Human RNase 1 was at the opposite end of the spectrum from cow RNase 1, with ∼5-fold lower activity at a much higher optimal pH (7.3) (Table 1). Non-mammalian homologs (chicken, anole lizard, and frog) all demonstrated very low catalytic activity at relatively low pH.

Table 1. Steady-state kinetic parameters of homologous ribonucleases.

| Species | pH-optimum for ssRNA | kcat/KM (106 M–1s–1) for ssRNA at pH-optimuma | kcat/KM (103 mM–1min–1) for poly(A:U) at pH 7.4a | kcat/KM (103 mM–1min–1) for poly(I:C) at pH 7.4a | Product (%) from hairpin at pH 7.4b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human (Homo sapiens) | 7.3 | 3 ± 1 | 12 ± 3 | 0.7 ± 0.2 | 89 ± 11 |

| Bat (Myotis lucifugus) | 7.3 | 3 ± 1 | 10 ± 3 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 89 ± 6 |

| Squirrel (Sciurus carolinensis) | 6.8 | 6 ± 1 | 3.4 ± 0.7 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 54 ± 6 |

| Horse (Equus ferus caballus) | 6.5 | 8 ± 1 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 0.4 ± 0.2 | 33 ± 4 |

| Cat (Felic catus) | 6.5 | 6.9 ± 0.1 | 0.023 ± 0.006 | 0.16 ± 0.08 | 24 ± 11 |

| Mouse (Mus musculus) | 6.4 | 8 ± 3 | 0.006 ± 0.002 | 0.05 ± 0.01 | 17 ± 2 |

| Cow (Bos taurus) | 6.1 | 13 ± 2 | 0.007 ± 0.002 | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 13 ± 3 |

| Chicken (Gallus gallus) | 6.2 | 0.7 ± 0.4 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 6 ± 2 |

| Anole (Anolis carolinensis) | 6.2 | 0.04 ± 0.01 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 5 ± 3 |

| Frog (Rana pipiens) | 6.2 | 0.03 ± 0.01 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 2 ± 2 |

Values are the mean ± SD from 4–7 independent experiments.

Values are the mean ± SD from 3–7 independent native gels like that in Supplementary Figure S3.

Although all ptRNases can degrade ssRNA substrates, only a small subset display high activity toward double-stranded (ds)RNA substrates [33]. Such a feature is consistent with a role in host defense, as antigenic dsRNAs can be produced or released by viruses and bacteria, and are known to activate inflammatory responses [57]. We determined the ability of RNase 1 homologs to degrade poly(I:C) and poly(A:U), two synthetic analogs of viral RNA. Intriguingly, human, bat, squirrel, and horse homologs displayed a pronounced ability to degrade dsRNA. For poly(A:U), human and bat RNase 1 showed the highest activity, with catalytic efficiencies ∼1800-fold higher and ∼1400‐fold higher, respectively, than that of cow RNase 1 (Table 1). Human RNase 1 demonstrated significantly higher activity than all other homologs, except for bat RNase 1. For poly(I:C), the trend was similar though less robust, with human RNase 1 showing ∼18-fold higher and bat RNase 1 showing ∼14-fold higher, catalytic efficiency than did cow RNase 1 (Table 1). Cat RNase 1 was moderately active against both substrates, whereas cow and mouse RNase 1 exhibited the lowest activity of the mammalian homologs. These trends are in line with previous studies that probed the differential ability of RNase 1 homologs to degrade dsRNA [27, 30, 31, 33]. The non-mammalian homologs showed no measureable activity against either dsRNA substrate (Table 1). The catalytically inactive H12A variant of human RNase 1 was used as a negative control and did not exhibit detectable activity against either substrate.

To confirm that the measured activity was specific for a double-stranded RNA substrate—and not confounded by the potentially heterogeneous nature of poly(A:U) and poly(I:C)—we employed an RNA/DNA hairpin substrate that contains a single ribonucleotide embedded within the sequence of a DNA oligonucleotide and that is labeled on the 5′ end with a fluorophore. We monitored the formation of the fluorescent 6-mer cleavage product of ribonuclease catalysis by electrophoresis using a native polyacrylamide gel (Supplemenary Figure S3). Densitometric analysis of substrate and cleavage products mirrored the same trend observed with the poly(A:U) and poly(I:C) substrates. Specifically, human and bat RNase 1 demonstrated the most product formation (∼90% for both), followed by squirrel RNase 1 (∼54%) and then the enzymes from horse, cat, mouse, and cow (Table 1). Again, human RNase 1 showed significantly higher activity than did other homologs, with the exception of bat RNase 1. As with the previous dsRNA substrates, H12A human RNase 1 and the non-mammalian homologs demonstrated negligible activity.

RNase 1 orthologs differ in their cellular entry and affinity for cell-surface components

RNase 1 homologs can enter human cells via endosomal translocation, a surprising trait that might be related to endogenous function. The association of RNase 1 with cell-surface glycans could aids this process [44, 50]. We were curious to know if the enzymes in our study have a similar ability to enter cells, and if this ability correlates with affinity for cell-surface moieties.

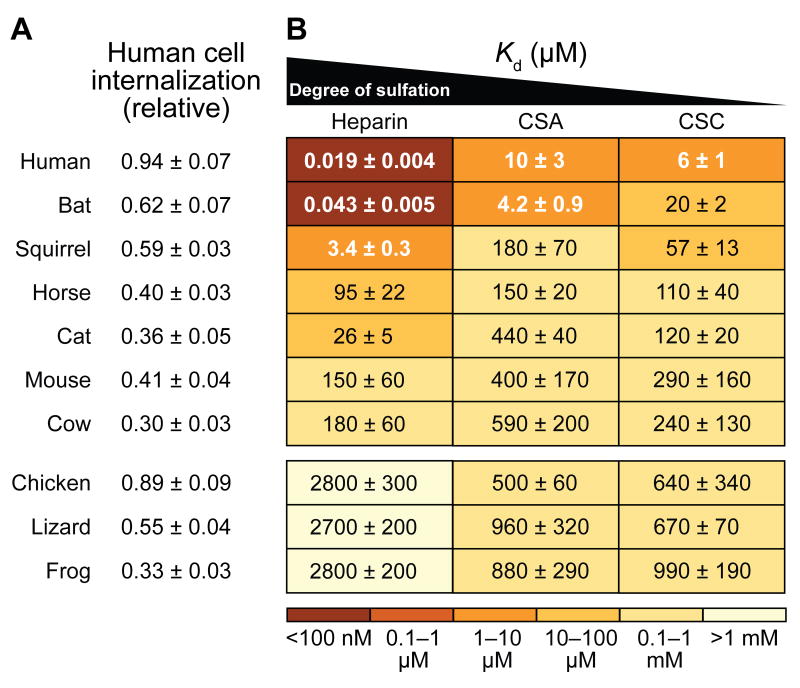

We measured the cellular uptake of fluorophore-labeled RNase 1 homologs by a non-adherent human cell-line (K-562) using flow cytometry. Interestingly, we found that all of the proteins in our study, both mammalian and non-mammalian, were taken-up readily by cells (Figure 1A). Of the mammalian orthologs, human RNase 1 demonstrated the highest level of cellular internalization, followed by bat and squirrel RNase 1. Anole RNase 1 was internalized similarly to human RNase, with chicken RNase also showing appreciable internalization. Cow and frog RNase showed the lowest levels of internalization.

Figure 1. Cellular binding and entry.

(A) Values of relative fluorescence for K-562 cells treated with an RNase 1–BODIPY conjugate (5 μM) for 4 h and then washed twice with PBS. Values are the mean ± SEM from 5–9 independent flow cytometry experiments.

(B) Values of Kd (μM) for the complex of RNase 1–BODIPY conjugates and cell-surface glycosaminoglycans, which have different levels of sulfation. Values are the mean ± SEM from 3–6 independent fluorescence polarization experiments, and are overlayed on a heatmap depicting relative affinity. CSA refers to chondroitin sulfate A; CSC refers to chondroitin sulfate C.

We hypothesized that those RNase orthologs with the highest levels of cellular uptake might bind more tightly to cell-surface glycans. We used fluorescence polarization to determine the affinities of fluorophore-labeled RNase 1 homologs for common cell-surface glycosaminoglycans, including heparan sulfate (approximated with heparin in our study; Supplementary Figure S4), as well as two forms of chondroitin sulfate. We found that the observed trend in cellular uptake of mammalian RNase 1 homologs was mirrored by their affinity for glycans: human and bat RNase 1 showed extremely tight (nanomolar) affinity for each glycan, and squirrel RNase 1 demonstrated moderately tight glycan binding (Figure 1). Of the mammalian proteins, cow and mouse RNase 1 exhibited the weakest binding, mirroring their lower levels of cellular uptake. For the non-mammalian orthologs, however, cellular uptake did not match glycan binding. Indeed, all of the non-mammalian homologs showed weak and, perhaps, physiologically irrelevant affinity for cell-surface glycans (Figure 1). These results are consistent with the uptake of non-mammalian homologs relying more on overall cationicity than on specific interactions with cell-surface components [46].

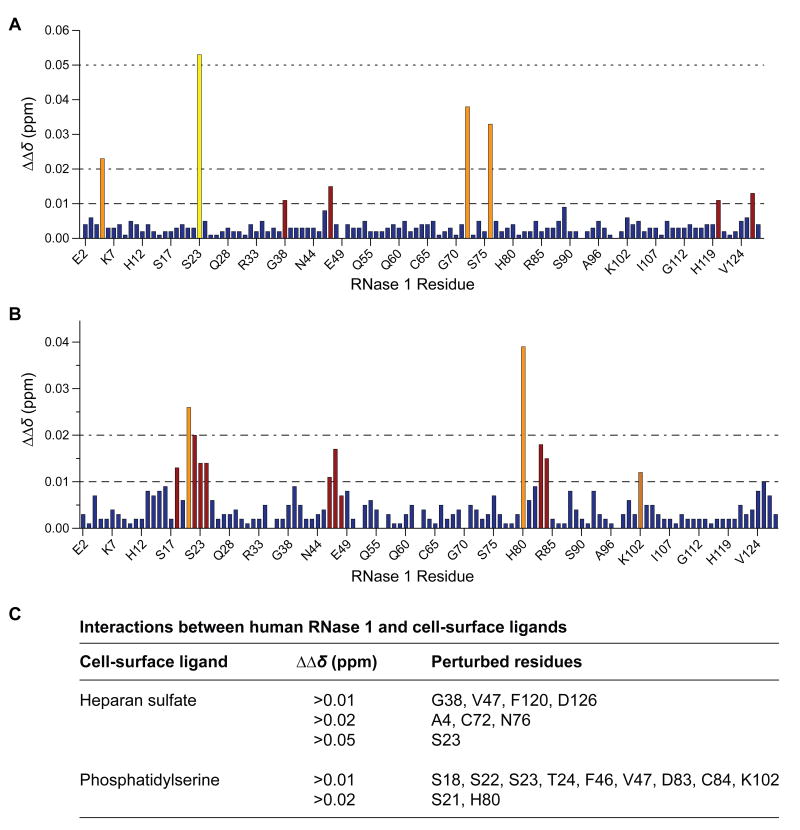

To provide high resolution on the binding of human RNase 1 to cell-surface moieties, we employed 1H,15N-HSQC NMR spectroscopy [51] to identify those residues in the human enzyme that interact with HS and PS, two prevalent membrane components. The backbone 1H and 15N NMR assignments for human RNase 1 were determined previously [52]. We found that the presence of zwitterionic CTAB micelles elicited few changes in the 1H and 15N chemical shifts. In contrast, these shifts were perturbed markedly by micelles containing an HS mimic or PS at one molar equivalent relative to RNase 1 (Figure 2). Major shift perturbations for both HS and PS were found throughout the amino acid sequence, with large perturbations clustered predominantly to a polar serine-rich loop, Ser18–Thr24, as well as at Cys72, Asn76, and His80.

Figure 2. Interaction of human RNase 1 with cell-surface ligands.

(A,B) Bar graphs of perturbations to the NMR chemical shifts of human [15N]-RNase 1 induced by a cell-surface ligand. A solution of human [15N]-RNase 1 was incubated with CTAB micelles that contained a molar equivalent of a mimic of heparan sulfate (panel A) or phosphatidylserine (panel B).

(C) List of human RNase 1 residues that had the largest perturbations induced by a mimic of heparan sulfate or phosphatidylserine.

Rapidly evolving RNase 1 residues are associated with novel functions

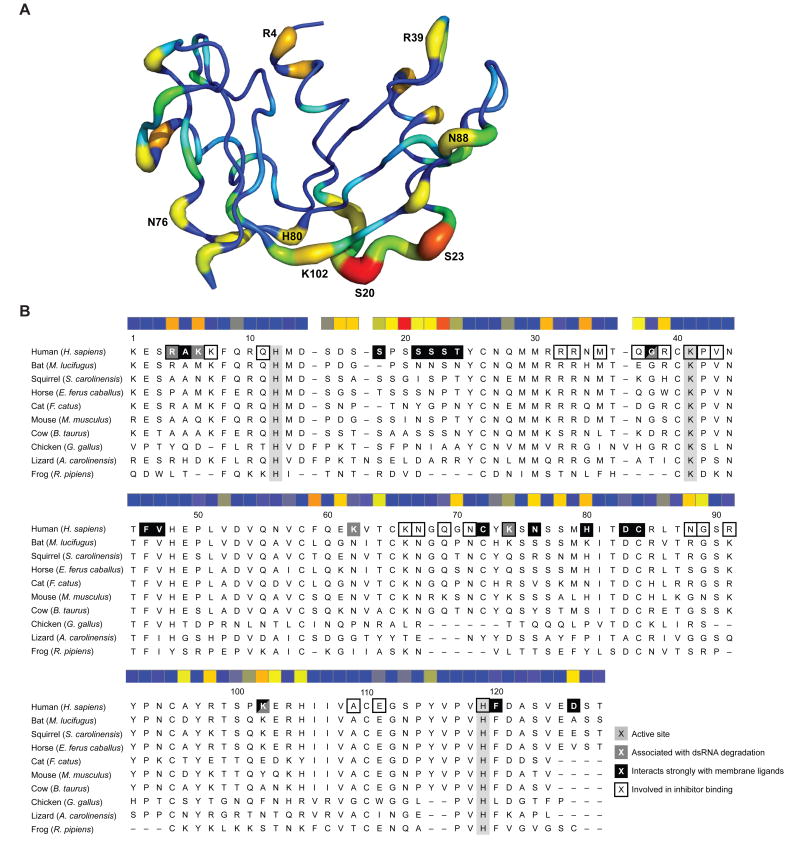

Mammalian RNase 1 orthologs share a high degree of identity and similarity in their amino acid sequences (Supplementary Table S4). Still, due to the significant functional differences uncovered in our study, we were curious to know if certain regions of the proteins were changing more quickly over time. We aligned the protein sequences of 30 mammalian RNase 1 homologs and used the program MEGA6 to estimate the mean (relative) evolutionary rate for each amino acid position. To visualize the relative evolutionary rates of specific residues in the context of protein structure, we created an image of human RNase 1 in which values of relative evolutionary rate were inserted as the β-factor for each atom (Figure 3A). We found that the majority of rapidly evolving residues were on the protein surface, whereas many residues considered integral for protein structure, as well as for enzymatic activity, were highly conserved across species.

Figure 3. Predicted evolution of RNase 1 enzymes.

(A) Three-dimensional structure of human RNase 1 in which residues predicted to be evolving at a faster rate are depicted with both a thicker backbone and a hotter color (red > orange > yellow > green > aqua > blue). The eight residues predicted to be evolving at the fastest rate are labeled explicitly.

(B) Protein sequence alignment for the ten RNase 1 homologs used in this study. A heatmap in which the predicted evolutionary rates of residues are depicted with colors as in panel A. The three key active-site residues are highlighted in light gray; residues in human RNase 1 known to correspond to various functions are labeled as indicated in the legend. Asn34, Asn76, and Asn88 in human RNase 1 are known to be N-glycosylated.

We also linearly mapped the relative evolutionary rates as a heatmap corresponding to a protein sequence alignment for the various RNase 1 homologs used in our study (Figure 3B). Previous structure–function analyses of RNase 1 variants have identified amino acid residues predicted to be involved in a variety of functions, including residues involved in the cleavage of ssRNA [10, 58, 59], residues associated with the degradation of dsRNA [27, 60, 61], and residues involved in binding to the ribonuclease inhibitor [56]. We found a dramatic correlation between residues predicted to be evolving faster and those residues associated with properties such as dsRNA-degradation (e.g., Arg4, Lys6, and Lys102) and cell-surface binding (e.g., Ser21, Ser22, Ser 23, Asn76, and His80). We note as well that asparagine residues that can undergo N-linked glycosylation prior to protein secretion were also predicted to be rapidly evolving sites (Asn34, Asn76, and Asn88). The recombinant proteins in our study lacked N-glycosylation, which could have effects on their function in their native environment.

Interestingly, we found that the key residues in the enzymic active site (His12, Lys41, and His119), along with those required for binding to ribonuclease inhibitor (including Lys7, Arg33, Met35, Pro42, Val43, Lys66, Asn71, Ala109, and Glu111), are generally conserved across species, consistent with stabilizing selection to retain these properties in all homologs.

Discussion

RNase 1 is an efficacious ribonucleolytic enzyme that circulates freely through biological fluids in all vertebrate animals. Despite its evolutionary conservation and robust presence in vivo, the physiological role of this enzyme is only beginning to be appreciated fully. To narrow this deficit, we have performed a comparative functional analysis of RNase 1 homologs from a broad subset of species, representing six orders of eutherian mammals, as well as the avian, reptilian and amphibian classes. This analysis, which is the first to quantify relevant biochemical properties of a large variety of homologous vertebrate ribonucleases, reveals pronounced functional differences not only between mammalian and non-mammalian proteins, but also between proteins from various mammalian species. We have uncovered differences in catalytic activity against both single-stranded and double-stranded RNA, as well as differential pH optima for maximum catalytic efficiency. We have also observed that certain RNase 1 homologs can enter cells much more readily than others, and that this ability correlates with enhanced cell-surface binding. Taken together, our functional characterization adds further evidence to the supposition that, apart from specially evolved variants of RNase 1 that exist in ruminant animals, the broader physiological role of RNase 1 has little to do with digestion.

We uncovered stark differences between the characteristics of mammalian versus non-mammalian RNase 1 homologs, which could illuminate the origins of the ptRNase family. Interestingly, ptRNases have been found only in vertebrates, and database searches against the genomes of invertebrates such as flies, worms, and ascidians did not yield any significant matches [4]. Nonetheless, ptRNase family members have been identified in a host of amphibian, avian, reptile and fish species, and select members of these groups have been found to have novel properties. For example, non-mammalian ptRNases display much lower ribonucleolytic activity against ssRNA substrates [62, 63]. Yet, several non-mammalian enzymes possess antimicrobial and angiogenic properties [64-66]. These properties are notable because RNase 5, also known as angiogenin, is a prominent and well-studied mammalian ptRNase. Angiogenin is known to promote angiogenesis, has demonstrated antimicrobial activity and other functions [67-69], and operates by a unique mechanism [70]. Like the non-mammalian RNases in our study, human angiogenin exhibits extremely low catalytic activity against ssRNA substrates and virtually no activity against dsRNA substrates (data not shown). Correspondingly, large-scale phylogenetic analyses of many non-mammalian and mammalian ptRNases indicate that the non-mammalian homologs are most evolutionarily similar to angiogenin, predicting a common ancestral enzyme [4]. Given the shared attributes of many non-mammalian ptRNases to the mammalian angiogenins, it is likely that RNase 5 represents the most ancient form of the mammalian enzyme, and that all other members arose from RNase 5 during mammalian evolution. An intriguing hypothesis is that the superfamily originated as a host-defense/pro-growth mechanism during early vertebrate evolution and underwent massive functional expansion in mammals, resulting in the current diversity of the family. The number of ptRNase genes in mammals is quite large (typically, 13–20), whereas avian and amphibian species lack such diversity [4]. This coincides with adaptive radiation of mammalian diversity occurring during the Cenozoic era.

Our data indicate that various RNase 1 homologs have optimal activity at vastly different pHs. For example, cow RNase 1 (i.e., RNase A) was the most active enzyme against ssRNA at the lowest pH. These results align well with the observation that RNase A is secreted in abundance from the bovine exocrine pancreas into the rumen, which is a harsh environment with a normal pH range of 5.8–6.4. There, RNase A is believed to degrade mRNA from symbiotic bacteria to assist with foregut fermentation and digestion [23]. Yet, we found that in non-ruminant animals, there is a distinct shift in pH optima. For example, human and bat RNase 1 enzymes have a pH optimum of 7.3, which is indistinguishable from the pH of many human biological fluids, including blood (pH 7.4). These findings suggest that, aside from digestion-specific homologs in ruminants, mammalian RNase 1 has adapted to circulate widely in vivo and to operate outside of the digestive tract.

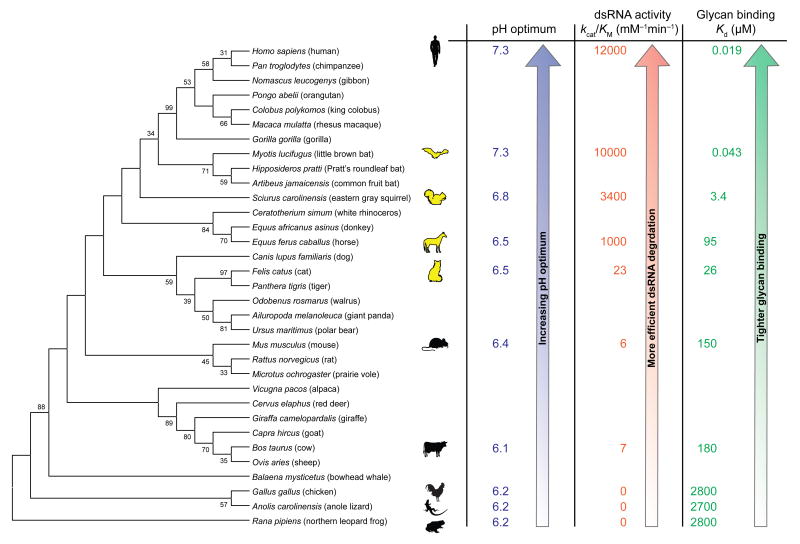

A striking finding from our study was the different ability of various homologs to degrade dsRNA. We found that the ptRNases from human and bat had the highest activity by a large margin (Table 1 and Figure 4). Degradation of dsRNA could have profound implications in vivo. Recent work has identified extracellular RNA (exRNA) as a heterogeneous class of secreted cofactors in bodily fluids that can contribute to coagulation, blood vessel permeability, cell–cell signaling, tumor progression, and inflammation. They can be single or double-stranded, and can originate from internal cells or from antigenic sources, such as invading bacteria or viruses [71, 72]. As the only known ribonuclease in bodily fluids with high, nonspecific ribonucleolytic activity, RNase 1 might be a natural regulator of exRNA. Additionally, exRNAs are recognized by toll-like receptors 3, 7, and 8, which are expressed inside the endosomes of endothelial and immune cells [73]. Significantly, we found that some mammalian RNase 1 homologs not only degrade dsRNA efficiently, but also enter endosomes readily, potentially mediated by interactions with cell-surface glycans. Human RNase 1, in particular, might be especially well adapted to degrade antigenic exRNA both within endosomes and in the extracellular space, suggesting an important role for human RNase 1 in regulating processes like coagulation and inflammation [72]. The amino acid sequence of human RNase 1 is identical to that of the Neanderthal enzyme [74], indicative of its biological role being established in a common ancestor at least 550,000 years ago.

Figure 4. Schematic summary of the diverse function of RNase 1 homologs across an evolutionary spectrum.

A neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree shows the evolutionary relationship of homologous ribonucleases (bootstrap values >30 are shown). Functional data obtained from this study, including pH optimum for catalysis, ability to catalyze the cleavage of a dsRNA [poly(A:U)], and affinity for a glycan (heparin), are mapped onto the tree and indicate an increasingly refined phenotype for the human homolog. The RNase 1 homologs from bat, squirrel, horse, and cat (yellow) had not been characterized previously and fill a large gap between the human and mouse enzymes.

Remarkably, many of the key residues that are predicted to be important for RNase 1 function—including dsRNA digestion and binding to cell-surface moieties—appear to be evolving at a faster rate than other residues (Figure 3). Not surprisingly, the most conserved residues across vertebrate RNase 1 homologs appear to be those involved in the catalytic active site, as well as those involved with binding to ribonuclease inhibitor, suggesting that such properties have been maintained throughout diversification. Taken together, our findings indicate that although the core structure and function of RNase 1 has remained consistent throughout evolution, the adaptation of various surface residues has contributed to distinct functional differences across species. Moreover, our study underscores the notion that a few changes to surface residues can manifest as markedly different biochemical and physiological properties.

Some of the functional data herein were predicted by previous studies in molecular genetics. Using phylogenetic analysis, Rosenberg and coworkers demonstrated that squirrel RNase1 genes emerged as a distinct cluster apart from RNase1 genes from mouse or rat [35]. They also predicted that some distinct surface substitutions might be impactful for biological function. Our results show that the biochemical properties of squirrel RNase 1 are indeed different from those of mouse RNase 1, and the squirrel enzyme appears to function more similarly to human or bat RNase 1 than to the rodent enzyme. Yu and Zhang analyzed RNase1 genes across a large spectrum of carnivores and detected positive selection toward greater cationicity, suggesting the onset of novel functional adaptations not related to digestion [75]. Similarly, our study found that cat RNase 1 possesses distinct properties from digestion-specific RNase A. Zhang and coworkers screened for the RNase1 gene in more than 20 bat species and detected evidence of adaptive gene duplication events that did not correlate to feeding habits. Their work, along with analyses by Goo and Cho, highlighted the rapid expansion of RNase1 genes in bat species, suggesting that RNase 1 might play other roles in bats unrelated to digestion [6, 36]. Our work supports this hypothesis, as we found that bat RNase 1 displays markedly different properties from RNase A, and is indeed much more similar to human RNase 1 than to any other homolog. We note, however, that the version of bat RNase 1 tested in our current study represents only a single version of many paralogous RNase1 genes found in the little brown bat genome [6].

Another ongoing mystery is how N-glycosylation of RNase 1 influences or regulates its endogenous function. Residues in human RNase 1 that undergo N‐linked glycoslyation are evolving more quickly than other residues (Figure 3). Analyses of human tissues and fluids indicate that various sources produce differentially glycosylated forms of RNase 1 [76, 77]. Differences in the function of these variously glycosylated forms of RNase 1 are not clear, though one hypothesis is that heavily glycosylated RNase 1 might be able to evade the ribonuclease inhibitor, serving as a natural mimic of the engineered form of RNase 1 currently in clinical trials for various types of cancer [21, 22]. Support for this hypothesis comes from recent data that showed a significant increase in the serum levels of RNase 1 containing N-glycosylated Asn88 in patients with pancreatic cancer [78]. In effect, the glycosylation of RNase 1 could constitute an unappreciated natural anti-cancer mechanism.

Proteins are subjected to natural selection as a result of evolutionary pressures on the organisms that contain them. As novel attributes often evolve incrementally, comparative functional analyses of a protein in related species can yield an enhanced understanding of biology and physiology [38-41]. From our data, we speculate that RNase 1 in humans and other mammals serves a broad regulatory role via the degradation of serum RNA, potentially mediating critical processes such as hemostasis, inflammation, and innate immunity (including anti-cancer activity).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. David S. Blehert and Elizabeth A. Bohuski of the USGS National Wildlife Health Center (Madison, Wisconsin, USA) for providing little brown bat tissue; Dr. Angela J. Gruber, Benjamin W. Gruber, and Emily R. Garnett (University of Wisconsin–Madison) for providing squirrel tissue; Drs. W. Milo Westler and Marco Tonelli (University of Wisconsin–Madison) for advice with HSQC NMR spectroscopy; and Dr. Trish T. Hoang for contributive discussions.

Funding: JEL was supported by an National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship. This work was supported by Grant R01 CA073808 (NIH) and made use of the National Magnetic Resonance Facility at Madison, which was supported by Grant P41 GM103399 (NIH).

Abbreviations

- CTAB

cetyltrimethylammonium bromide

- ds

double stranded

- DSF

differential scanning fluorimetry

- exRNA

extracellular RNA

- HS

heparan sulfate

- MES

2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid

- PS

phosphatidylserine

- ptRNases

pancreatic-type ribonucleases

- RI

RNase inhibitor

- RNase 1

ribonuclease 1

- ss

single stranded

Footnotes

Author Contribution: JEL and CHH conceived the project, performed experiments, and acquired the data. All authors analyzed and interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript.

Competing Interests: The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): R.T.R. is a founder of Quintessence Biosciences, Inc. (Madison, WI), which is developing cancer chemotherapeutic agents based on ribonucleases.

References

- 1.Sorrentino S. The eight human “canonical” ribonucleases: Molecular diversity, catalytic properties, and special biological actions of the enzyme proteins. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:2194–2200. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koczera P, Martin L, Marx G, Schuerholz T. The ribonuclease A superfamily in humans: Canonical RNases as the buttress of innate immunity. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17:1278. doi: 10.3390/ijms17081278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beintema JJ, Breukelman HJ, Carsana A, Furia A. Evolution of vertebrate ribonucleases: ribonuclease A superfamily. In: D'Alessio G, Riordan JF, editors. Ribonucleases: Structures and Functions. Academic Press; New York: 1997. pp. 245–269. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cho S, Beintema JJ, Zhang J. The ribonuclease A superfamily of mammals and birds: Identifying new members and tracing evolutionary histories. Genomics. 2005;85:208–220. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2004.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dyer KD, Rosenberg HF. The RNase A superfamily: generation of diversity and innate host defense. Mol Divers. 2006;10:585–597. doi: 10.1007/s11030-006-9028-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goo SM, Cho S. The expansion and functional diversification of the mammalian ribonuclease a superfamily epitomizes the efficiency of multigene families at generating biological novelty. Genome Biol Evol. 2013;5:2124–2140. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evt161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dickson KA, Haigis MC, Raines RT. Ribonuclease inhibitor: Structure and function. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 2005;80:349–374. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6603(05)80009-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lomax JE, Bianchetti CM, Chang A, Phillips GN, Jr, Fox BG, Raines RT. Functional evolution of ribonuclease inhibitor: insights from birds and reptiles. J Mol Biol. 2014;426:3041–3056. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2014.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.D'Alessio G, Riordan JF, editors. Ribonucleases: Structures and Functions. Academic Press; New York: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raines RT. Ribonuclease A. Chem Rev. 1998;98:1045–1065. doi: 10.1021/cr960427h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marshall GR, Feng JA, Kuster DJ. Back to the future: Ribonuclease A. Biopolymers. 2008;90:259–277. doi: 10.1002/bip.20845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Su AI, Wiltshire T, Batalov S, Lapp H, Ching KA, Block D, Zhang J, Soden R, Hayakawa M, Kreiman G, Cooke MP, Walker JR, Hogenesch JB. A gene atlas of the mouse and human protein-encoding transcriptomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:6062–6067. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400782101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morita T, Niwata Y, Ohgi K, Ogawa M, Irie M. Distribution of two urinary ribonuclease-like enzymes in human organs and body fluids. J Biochem. 1986;99:17–25. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a135456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kurihara M, Ogawa M, Ohta T, Kurokawa K, Kitahara T. Purification and immunological characterization of human pancreatic ribonuclease. Cancer Res. 1982;42:4836–4841. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beintema JJ, Wietzes P, Weickmann JL, Glitz DG. The amino acid sequence of human pancreatic ribonuclease. Anal Biochem. 1984;136:48–64. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(84)90306-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weickmann JL, Olson EM, Glitz DG. Immunological assay of pancreatic ribonuclease in serum as an indicator of pancreatic cancer. Cancer Res. 1984;44:1682–1687. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fischer S, Nishio M, Dadkhahi S, Gansler J, Saffarzadeh M, Shibamiyama A, Kral N, Baal N, Koyama T, Deindl E, Preissner KT. Expression and localisation of vascular ribonucleases in endothelial cells. Thromb Haemost. 2011;105:345–355. doi: 10.1160/TH10-06-0345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leland PA, Raines RT. Cancer chemotherapy—ribonucleases to the rescue. Chem Biol. 2001;8:405–413. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(01)00030-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Benito A, Ribó M, Vilanova M. On the track of antitumor ribonucleases. Mol Biosyst. 2005;1:294–302. doi: 10.1039/b502847g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee JE, Raines RT. Ribonucleases as novel chemotherapeutics: The ranpirnase example. BioDrugs. 2008;22:53–58. doi: 10.2165/00063030-200822010-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Strong LE, Kink JA, Pensinger D, Mei B, Shahan M, Raines RT. Efficacy of ribonuclease QBI-139 in combination with standard of care therapies. Cancer Res. 2012;72(Suppl. 1):1838. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Strong LE, Kink JA, Mei B, Shahan MN, Raines RT. First in human phase I clinical trial of QBI-139, a human ribonuclease variant, in solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(Suppl):TPS3113. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barnard EA. Biological function of pancreatic ribonuclease. Nature. 1969;221:340–344. doi: 10.1038/221340a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Snook JT. Dietary regulation of pancreatic enzyme synthesis, secretion and inactivation in the rat. J Nutr. 1965;87:297–305. doi: 10.1093/jn/87.3.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peterson LM. Serum RNase in the diagnosis of pancreatic carcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:2630–2634. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.6.2630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schein CH. From housekeeper to microsurgeon: The diagnostic and therapeutic potential of ribonucleases. Nat Biotechnol. 1997;15:529–536. doi: 10.1038/nbt0697-529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jermann TM, Opitz JG, Stackhouse J, Benner SA. Reconstructing the evolutionary history of the artiodactyl ribonuclease superfamily. Nature. 1995;374:57–59. doi: 10.1038/374057a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beintema JJ, Benner SA. Ribonucleases in ruminants. Science. 2002;297:1121–1122. doi: 10.1126/science.297.5584.1121b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Antignani A, Naddeo M, Cubellis MV, Russo A, D'Alessio G. Antitumor action of seminal ribonuclease, its dimeric structure, and its resistance to the cytosolic ribonuclease inhibitor. Biochemistry. 2001;40:3492–3496. doi: 10.1021/bi002781m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eller CH, Lomax JE, Raines RT. Bovine brain ribonuclease is the functional homolog of human ribonuclease 1. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:25996–26006. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.566166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang J, Zhang YP, Rosenberg HF. Adaptive evolution of a duplicated pancreatic ribonuclease gene in a leaf-eating monkey. Nat Genet. 2002;30:411–415. doi: 10.1038/ng852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang Z, Xu S, Du K, Huang F, Chen Z, Zhou K, Ren W, Yang G. Evolution of digextive enzymes and RNASE1 provides insights into dietary switch of cetaceans. Mol Biol Evol. 2016;33:3144–3157. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Libonati M, Sorrentino S. Degradation of double-stranded RNA by mammalian pancreatic-type ribonucleases. Methods Enzymol. 2001;341:234–248. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(01)41155-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dubois JY, Jekel PA, Mulder PP, Bussink AP, Catzeflis FM, Carsana A, Beintema JJ. Pancreatic-type ribonuclease 1 gene duplications in rat species. J Mol Evol. 2002;55:522–533. doi: 10.1007/s00239-002-2347-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Siegel SJ, Percopo CM, Dyer KD, Zhao W, Roth VL, Mercer JM, Rosenberg HF. RNase 1 genes from the family Sciuridae define a novel rodent ribonuclease cluster. Mamm Genome. 2009;20:749–757. doi: 10.1007/s00335-009-9215-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu H, Liu Y, Meng F, He B, Han N, Li G, Rossiter SJ, Zhang S. Multiple bursts of pancreatic ribonuclease gene duplication in insect-eating bats. Gene. 2013;526:112–117. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2013.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu J, Wang XP, Cho S, Lim BK, Irwin DM, Ryder OA, Zhang YP, Yu L. Evolutionary and functional novelty of pancreatic ribonuclease: A study of Musteloidea (order Carnivora) Sci Rep. 2014;4:5070. doi: 10.1038/srep05070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dean AM, Thornton JW. Mechanistic approaches to the study of evolution: The functional synthesis. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8:675–688. doi: 10.1038/nrg2160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Soskine M, Tawfik DS. Mutational effects and the evolution of new protein functions. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11:572–582. doi: 10.1038/nrg2808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liberles DA, Teichmann SA, Bahar I, Bastolla U, Bloom J, Bornberg-Bauer E, Colwell LJ, de Koning AP, Dokholyan NV, Echave J, Elofsson A, Gerloff DL, Goldstein RA, Grahnen JA, Holder MT, Lakner C, Lartillot N, Lovell SC, Naylor G, Perica T, Pollock DD, Pupko T, Regan L, Roger A, Rubinstein N, Shakhnovich E, Sjolander K, Sunyaev S, Teufel AI, Thorne JL, Thornton JW, Weinreich DM, Whelan S. The interface of protein structure, protein biophysics, and molecular evolution. Protein Sci. 2012;21:769–785. doi: 10.1002/pro.2071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Harms MJ, Thornton JW. Evolutionary biochemistry: revealing the historical and physical causes of protein properties. Nat Rev Genet. 2013;14:559–571. doi: 10.1038/nrg3540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smith BD, Soellner MB, Raines RT. Potent inhibition of ribonuclease A by oligo(vinylsulfonic acid) J Biol Chem. 2003;278:20934–20938. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301852200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Johnson RJ, Lavis LD, Raines RT. Intraspecies regulation of ribonucleolytic activity. Biochemistry. 2007;46:13131–13140. doi: 10.1021/bi701521q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chao TY, Lavis LD, Raines RT. Cellular uptake of ribonuclease A relies on anionic glycans. Biochemistry. 2010;49:10666–10673. doi: 10.1021/bi1013485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lomax JE, Eller CH, Raines RT. Rational design and evaluation of mammalian ribonuclease cytotoxins. Methods Enzymol. 2012;502:273–290. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-416039-2.00014-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sundlass NK, Eller CH, Cui Q, Raines RT. Contribution of electrostatics to the binding of pancreatic-type ribonucleases to membranes. Biochemistry. 2013;52:6304–6312. doi: 10.1021/bi400619m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Niesen FH, Berglund H, Vedadi M. The use of differential scanning fluorimetry to detect ligand interactions that promote protein stability. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:2212–2221. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Menzen T, Friess W. High-throughput melting-temperature analysis of a monoclonal antibody by differential scanning fluorimetry in the presence of surfactants. J Pharm Sci. 2013;102:415–428. doi: 10.1002/jps.23405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kelemen BR, Klink TA, Behlke MA, Eubanks SR, Leland PA, Raines RT. Hypersensitive substrate for ribonucleases. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:3696–3701. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.18.3696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Eller CH, Chao TY, Singarapu KK, Ouerfelli O, Yang G, Markley JL, Danishefsky SJ, Raines RT. Human cancer antigen Globo H Is a cell-surface ligand for human ribonuclease 1. ACS Cent Sci. 2015;1:181–190. doi: 10.1021/acscentsci.5b00164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ziarek JJ, Peterson FC, Lytle BL, Volkman BF. Binding site identification and structure determination of protein–ligand complexes by NMR. Methods Enzymol. 2011;493:241–275. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-381274-2.00010-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kover KE, Bruix M, Santoro J, Batta G, Laurents DV, Rico M. The solution structure and dynamics of human pancreatic ribonuclease determined by NMR spectroscopy provide insight into its remarkable biological activities and inhibition. J Mol Biol. 2008;379:953–965. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.04.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Edgar RC. MUSCLE: Multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:1792–1797. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jones DT, Taylor WR, Thornton JM. The rapid generation of mutation data matrices from protein sequences. Comput Appl Biosci. 1992;8:275–282. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/8.3.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A, Kumar S. MEGA6: molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 6.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30:2725–2729. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Johnson RJ, McCoy JG, Bingman CA, Phillips GN, Jr, Raines RT. Inhibition of human pancreatic ribonuclease by the human ribonuclease inhibitor protein. J Mol Biol. 2007;367:434–449. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tatematsu M, Seya T, Matsumoto M. Beyond dsRNA: Toll-like receptor 3 signalling in RNA-induced immune responses. Biochem J. 2014;458:195–201. doi: 10.1042/BJ20131492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Findlay D, Herries DG, Mathias AP, Rabin BR, Ross CA. The active site and mechanism of action of bovine pancreatic ribonuclease. Nature. 1961;190:781–784. doi: 10.1038/190781a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cuchillo CM, Nogués MV, Raines RT. Bovine pancreatic ribonuclease: Fifty years of the first enzymatic reaction mechanism. Biochemistry. 2011;50:7835–7841. doi: 10.1021/bi201075b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sorrentino S, Naddeo M, Russo A, D'Alessio G. Degradation of double-stranded RNA by human pancreatic ribonuclease: Crucial role of noncatalytic basic amino acid residues. Biochemistry. 2003;42:10182–10190. doi: 10.1021/bi030040q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dey P, Islam A, Ahmad F, Batra JK. Role of unique basic residues of human pancreatic ribonuclease in its catalysis and structural stability. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;360:809–814. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.06.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lee JE, Raines RT. Contribution of active-site residues to the function of onconase, a ribonuclease with antitumoral activity. Biochemistry. 2003;42:11443–11450. doi: 10.1021/bi035147s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pizzo E, Merlino A, Turano M, Russo Krauss I, Coscia F, Zanfardino A, Varcamonti M, Furia A, Giancola C, Mazzarella L, Sica F, D'Alessio G. A new RNase sheds light on the RNase/angiogenin subfamily from zebrafish. Biochem J. 2011;433:345–355. doi: 10.1042/BJ20100892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nitto T, Dyer KD, Czapiga M, Rosenberg HF. Evolution and function of leukocyte RNase A ribonucleases of the avian species, Gallus gallus. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:25622–25634. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604313200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pizzo E, Buonanno P, Di Maro A, Ponticelli S, De Falco S, Quarto N, Cubellis MV, D'Alessio G. Ribonucleases and angiogenins from fish. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:27454–27460. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605505200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cho S, Zhang J. Zebrafish ribonucleases are bactericidal: implications for the origin of the vertebrate RNase A superfamily. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:1259–1268. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hooper LV, Stappenbeck TS, Hong CV, Gordon JI. Angiogenins: A new class of microbicidal proteins involved in innate immunity. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:269–273. doi: 10.1038/ni888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Li S, Hu Gf. Emerging role of angiogenin in stress response and cell survival under adverse conditions. J Cell Physiol. 2012;227:2822–2826. doi: 10.1002/jcp.23051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lyons SM, Fay MM, Akiyama Y, Anderson PJ, Ivanov P. RNA biology of angiogenin: Current state and perspectives. RNA Biol. 2017;14:171–178. doi: 10.1080/15476286.2016.1272746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hoang TT, Raines RT. Molecular basis for the autonomous promotion of cell proliferation by angiogenin. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;45:818–831. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Preissner KT. Extracellular RNA: A new player in blood coagulation and vascular permeability. Hamostaseologie. 2007;27:373–377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zernecke A, Preissner KT. Extracellular ribonucleic acids (RNA) enter the stage in cardiovascular disease. Circ Res. 2016;118:469–479. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.307961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lester SN, Li K. Toll-like receptors in antiviral innate immunity. J Mol Biol. 2014;426:1246–1264. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2013.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Prüfer K, Racimo F, Patterson N, Jay F, Sankararaman S, Sawyer S, Heinze A, Renaud G, Sudmant PH, de Filippo C, Li H, Mallick S, Dannemann M, Fu Q, Kircher M, Kuhlwilm M, Lachmann M, Meyer M, Ongyerth M, Siebauer M, Theunert C, Tandon A, Moorjani P, Pickrell J, Mullikin JC, Vohr SH, Green RE, Hellmann I, Johnson PLF, Blanche H, Cann H, Kitzman JO, Shendure J, Eichler EE, Lein ES, Bakken TE, Golovanova LV, Doronichev VB, Shunkov MV, Dereviano AP, Viola B, Slatkin M, Reich D, Kelso J, Pääbo S. The complete genome sequence of a Neanderthal from the Altai Mountains. Nature. 2014;505:43–49. doi: 10.1038/nature12886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yu L, Zhang YP. The unusual adaptive expansion of pancreatic ribonuclease gene in carnivora. Mol Biol Evol. 2006;23:2326–2335. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msl101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ribó M, Beintema JJ, Osset M, Fernández E, Bravo J, de Llorens R, Cuchillo CM. Heterogeneity in the glycosylation pattern of human pancreatic ribonuclease. Biol Chem Hoppe-Seyler. 1994;375:357–363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Barrabés S, Pagès-Pons L, Radcliffe CM, Tabarés G, Fort E, Royle L, Harvey DJ, Moenner M, Dwek RA, Rudd PM, De Llorens R, Peracaula R. Glycosylation of serum ribonuclease 1 indicates a major endothelial origin and reveals an increase in core fucosylation in pancreatic cancer. Glycobiology. 2007;17:388–400. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwm002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Nakata D. Increased N-glycosylation of Asn88 in serum pancreatic ribonuclease 1 is a novel diagnostic marker for pancreatic cancer. Sci Rep. 2014;4:6715. doi: 10.1038/srep06715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.