Abstract

The first asymmetric [3+1]-cycloaddition was successfully achieved by copper(I) triflate/double-sidearmed bisoxazoline complex catalyzed reactions of β-triisopropyl-silyl-substituted enoldiazo compounds with sulfur ylides. This methodology delivered a series of chiral cyclobutenes in good yields with high enantio- and diastereoselectivities (up to 99% ee, and >20:1 d.r.). Additionally, the [3+1]-cycloaddition of catalytically generated metallo-enolcarbenes was successfully extended to reaction with a stable benzylidene dichlororuthenium complex.

Keywords: asymmetric catalysis, cycloaddition, cyclobutenes, diazo compounds, ylides

The combination of two or more unsaturated structural units to form cyclic organic compounds is among the most useful synthetic constructions in organic chemistry.[1] The development of [4+2]-cycloaddition reactions have provided the most advantageous scheme for the formation of organic compounds having six-membered rings,[2] and recently available [3+3]-cycloaddition processes have added complimentary methodologies.[3] Dipolar cycloaddition reactions, especially those that combine a 1,3-dipole with an alkene or alkyne, have offered access to five- and seven-membered-ring systems.[4] The synthesis of four-membered rings have used [2+2]-cycloaddition,[5] but alternative [3+1]-cycloaddition processes have rarely been reported.[6]

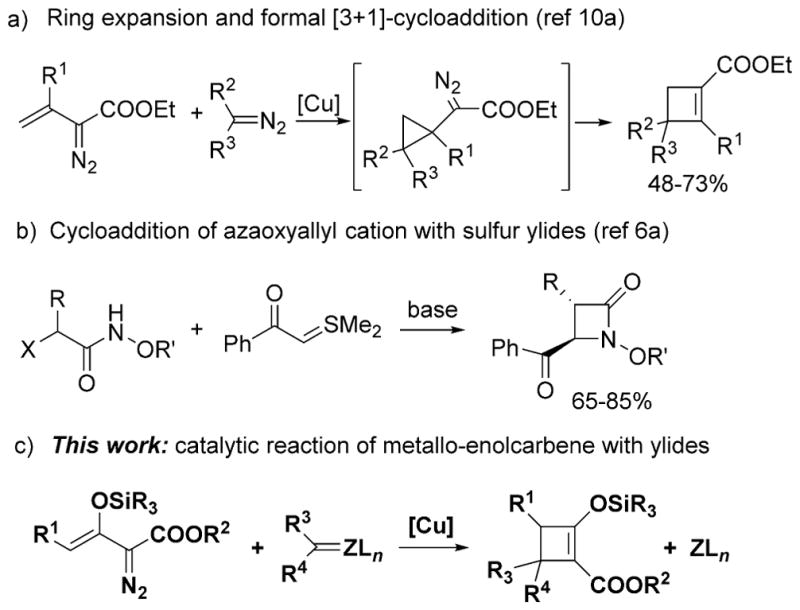

The four-membered all-carbon ring is an important structural motif that is present in natural products and biologically active compounds, but is less accessible than are other ring structures.[7] Furthermore, cyclobutanes and cyclobutenes are integral to synthetic strategies involving facile ring-expansion or ring-cleavage reactions.[8] Traditionally, [2+2]-cycloadditions with alkenes or alkynes have been the preferred synthetic route to cyclobutanes and cyclobutenes, but only recently has high enantiocontrol been achieved using chiral Lewis acid catalysis in these transformations.[9] [3+1]-Cycloaddition presents an attractive strategy for the construction of structurally diverse four-membered all-carbon rings; however, this approach has only recently been recognized and is underexploited.[6] A ring expansion catalytic methodology has been reported in which vinyldiazo esters and either another diazo compound[10a] or iminoiodinanes[10b] formed cyclobutenes or 2-azetines in what is a formal [3+1]-cycloaddition process (Scheme 1a). An alternative cycloaddition between azaoxyallyl cations and sulfur ylides has been reported to form β-lactams (Scheme 1b),[6a] but neither of these approaches to formal [3+1]-cycloaddition occurred in high yield or were suitable to high levels of enantiocontrol. We now report a general methodology for highly stereoselective [3+1]-cycloaddition between enoldiazoacetates and ylides, especially conveniently prepared stable sulfur ylides (Scheme 1c).

Scheme 1.

[3+1]-Cycloaddition reactions.

Metallo-enolcarbenes generated catalytically from stable enoldiazo compounds exhibit electrophilic character at the vinylogous carbon and nucleophilic character at the metal carbene carbon, making them metallo-1,3-dipole equivalents.[3a,11] These versatile intermediates have emerged as a synthetically useful class of three-carbon adducts when paired with a broad spectrum of dipoles and nucleophilic unsaturated compounds to construct cyclic molecules through [3+3]-cycloaddition[3a,11a,b] or by [3+2]-cycloaddition.[11c–f] Our intent was now to use these versatile intermediates for [3+1]-cycloaddition reactions by addition/elimination with stable ylides whose nucleophilic reactivity would allow bond formation at the electrophilic vinylogous position of metallo-enolcarbenes that, with displacement of a leaving group from the intermediate adduct, would form the desired [3+1]-cycloaddition product. To initiate this investigation, we selected benzoyl sulfur ylides that have been utilized as one-carbon units in [2+1]- and [4+1]-cycloaddition reactions.[12]

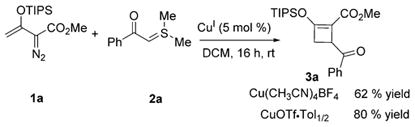

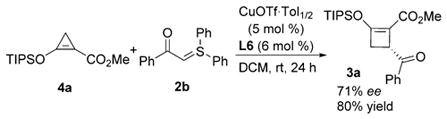

Our previous studies have demonstrated the advantages of copper catalysts for carbene transfer reactions of enoldiazo compounds.[11a,13] Additionally, recent investigations[14] reported the unique compatibility of copper catalysts in cycloaddition reactions of sulfur ylides. Our inquiry began with the reaction of triisopropylsilyl (TIPS)-substituted enoldiazoacetate 1a with easily accessible and stable α-benzoyl dimethylsulfur ylide 2a at room temperature in the presence of a catalytic amount Cu(CH3CN)4BF4 in dichloromethane (DCM). As proposed, the 1-carbomethoxy-2-triisopropylsilyloxy-4-benzoylcyclobutene 3a was generated smoothly in 62% yield [Eq. (1)], and its structure was confirmed by X-ray analysis. No reaction occurred in the absence of catalyst. Further screening of reaction conditions showed that nonligated CuOTf·Tol1/2 could improve yield of the [3+1]-cycloaddition to 80% [Eq. (1)]. The reactions catalyzed by copper(II) triflate and allylpalladium(II) also produced the desired cyclobutene product, however, with low yields (48% and 16%, respectively). Neither dirhodium tetraacetate, silver (AgSbF6) catalysts, nor cationic gold(I) ([PPh3]AuCl]/AgSbF6) were effective catalysts for this transformation.

|

(1) |

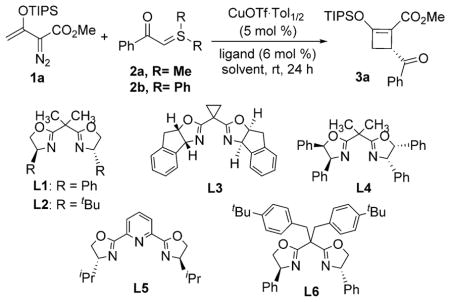

Encouraged by these results, we sought to perform this transformation enantioselectively by employing chiral copper complexes for the reaction between 1a and α-benzoyl sulfur ylide 2 (Table 1). Promising initial results were provided by copper catalysts generated in situ from CuOTf·Tol1/2 and C2-symmetric bisoxazolines (BOX); 3a was generated with low to moderate enantiomeric excess in various yields (Table 1, entries 1–4). No reaction occurred when the 2,6-pyridinebi-s(oxazoline) L5 was employed (Table 1, entry 5). Further ligand screening found that the double-sidearmed bisoxazoline[15] L6 [(S)-BTBBPh-SaBOX] stood out as the superior choice (Table 1, entry 6). To further improve the enantioselectivity, diphenylsulfur ylide 2b was employed, and its use gave 3a in 81% yield and 71% ee (Table 1, entry 11). Decreasing the reaction temperature to −20°C further improved enantioselectivity to 83% at a prolonged reaction time (Table 1, entry 13). Alternative use of the acetonitrile-coordinated copper(I) catalyst, Cu(MeCN)4BF4, with L6 also gave 3a with comparable enantioselectivity, but in lower yield (Table 1, entry 12). The absolute configuration of 3a was unambiguously determined to be 3R through X-ray single-crystal analysis (Figure 1).[16]

Table 1.

Selected conditions for optimization of the asymmetric [3+1]-cycloaddition reaction of 1a with 2.[a]

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Catalyst | Ligand | 2 | Solvent | Yield[b] [%] | ee[c] [%] |

| 1 | CuOTf·Tol1/2 | L1 | 2a | DCM | 48 | 11 |

| 2 | CuOTf·Tol1/2 | L2 | 2a | DCM | 14 | 29 |

| 3 | CuOTf·Tol1/2 | L3 | 2a | DCM | 51 | 45 |

| 4 | CuOTf·Tol1/2 | L4 | 2a | DCM | 70 | 7 |

| 5 | CuOTf·Tol1/2 | L5 | 2a | DCM | 0 | – |

| 6 | CuOTf·Tol1/2 | L6 | 2a | DCM | 74 | 55 |

| 7 | CuOTf·Tol1/2 | L6 | 2a | DCE | 68 | 53 |

| 8 | CuOTf·Tol1/2 | L6 | 2a | CHCl3 | 46 | 33 |

| 9[e] | CuOTf·Tol1/2 | L6 | 2a | toluene | 34 | 33 |

| 10[e] | CuOTf·Tol1/2 | L6 | 2a | Et2O | 51 | 0 |

| 11 | CuOTf·Tol1/2 | L6 | 2b | DCM | 81 | 71 |

| 12 | Cu(MeCN)4BF4 | L6 | 2b | DCM | 61 | 70 |

| 13[d,e] | CuOTf·Tol1/2 | L6 | 2b | DCM | 72 | 83 |

Reaction conditions: 1 (0.24 mmol, 1.2 equiv) in dry DCM (1.0 mL) was added to a 1.0 mL DCM solution of 2 (0.20 mmol, 1.50 equiv), CuOTf·Tol1/2 (0.01 mmol), and ligand (0.012 mmol) under N2 within 1 h.

Yield of isolated product 3 based on the limiting reagent 2.

Enantiomeric excesses were determined by HPLC analysis with a chiral stationary phase.

Reaction was performed at −20 °C.

Reaction time was 36 h.

Figure 1.

ORTEP diagram of the X-ray crystal structure of (R)-methyl 4-benzoyl-2-(triisopropylsilyloxy)cyclobut-1-ene-carboxylate 3a.

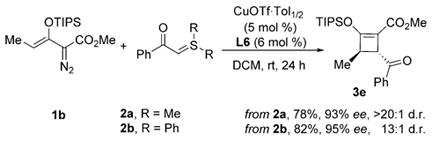

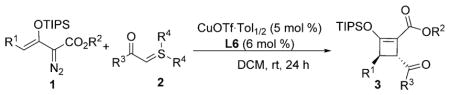

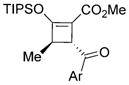

A γ-methyl substituent on the enoldiazoacetate markedly increased the enantioselectivity in reactions with sulfur ylides 2a or 2b performed at room temperature [Eq. (2)]. In these reactions, a second stereocenter is generated. Excellent diastereoselectivity was observed in the reaction with dimethyl-substituted sulfur ylide 2a (d.r. >20:1), while lower diastereoselectivity occurred from reactions with the diphenyl analog 2b (d.r. 13:1). However, no reaction occurred with γ-phenylenoldiazoacetate (1c), suggesting steric congestion in the cycloaddition process. The trans configuration of 4-benzoyl-3-methyl-2-triisopropylsilyloxy-cyclobutene 3e was determined by a 1D-NOESY experiment. Chemical shift differences between trans and cis isomers of 3e were distinguishable.

|

(2) |

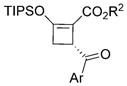

Substrate generality was investigated by changing the aryl groups of sulfur ylides 2 (Table 2). Those with electron-rich and halogen substituents on the aromatic ring of the acyl group reacted smoothly with 1b, generating the corresponding cyclized products in good yields (72–86%, 3e–3k) with excellent enantioselectivities (93–99% ee) and good to excellent diastereoselectivities. High enantiocontrol (97% ee) was achieved with the electron-withdrawing cyano group at the para-position of the aryl group (R3) of sulfur ylide 2 albeit with a lower % conversion of 2l and a lower yield of isolated cyclobutene 3l. This screening also confirmed that the presence of a methyl group at C4 of the enoldiazoacetate (R1) significantly improved enantioselectivity (93–99% ee) (3a–3c vs. 3e, 3i, and 3j). The products 4-aroyl-3-methyl-2-triisopropylsilyloxy-cyclobutene 3e–3l were assigned to be 3R,4R based on X-ray single-crystal analysis of 3a and NMR analysis of 3e–3l.

Table 2.

Scope of the asymmetric [3+1]-cycloaddition reaction of enoldiazoacetate 1 with sulfur ylides 2.[a]

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Yield(%)[b] | ee(%)[c] | |||

| 3a[e,f]: | 72 | 83 | (R2 = Me, Ar = Ph, R4 = Ph) | |

| 3b: | 81 | 72 | (R2 = Me, Ar = 4-ClC6H4, R4 = Ph) | |

| 3c: | 82 | 70 | (R2 = Me, Ar = 4-BrC6H4, R4 = Ph) | |

| 3d: | 73 | 73 | (R2= tBu, Ar = Ph, R4 = Ph) | |

| ||||

| Yield(%)[b] | ee(%)[c] | d.r.[d] | ||

| 3e: | 74 | 93 | >20:1 | (Ar = Ph, R4 = Me) |

| 3f: | 80 | 93 | 16:1 | (Ar = 4-MeC6H4, R4 = Me) |

| 3g: | 82 | 98 | 14:1 | (Ar = 4-MeOC6H4, R4 = Me) |

| 3h: | 72 | 99 | >20:1 | (Ar = naphthyl, R4 = Me) |

| 3i: | 80 | 95 | 18:1 | (Ar = 4-ClC6H4, R4 = Me) |

| 3j: | 74 | 97 | >20:1 | (Ar = 4-BrC6H4, R4 = Me) |

| 3k: | 86 | 96 | 15:1 | (Ar = 2-thiophenyl, R4 = Me) |

| 3l: | 58 | 97 | 16:1 | (Ar = 4-CNC6H4, R4 = Ph) |

Reaction conditions: 1 (0.24 mmol, 1.2 equiv) in dry DCM (1.0 mL) was added to a 1.0 mL DCM solution of 2 (0.20 mmol, 1.0 equiv), CuOTf·Tol1/2 (0.01 mmol), and L6 (0.012 mmol) under N2 within 1 h.

Yield of isolated product 3 based on the limiting reagent 2.

Enantiomeric excesses determined by HPLC analysis with a chiral stationary phase.

Diastereomeric ratios were determined by 1H NMR analysis of the reaction mixtures.

Reactions performed at −20°C.

Reactions performed for 48 hours.

Recently, donor–acceptor-substituted cyclopropenes generated from enoldiazo compounds by dinitrogen extrusion have been identified as the first-formed intermediates in many metal carbene reactions,[17] and they have proven to be efficient metallo-vinylcarbene precursors in cycloaddition reactions.[18] A close spectroscopic inspection of the reaction of 1a with 2b demonstrated the formation of donor–acceptor-substituted cyclopropene 4a under standard reaction conditions. Furthermore, the reaction of pre-prepared cyclopropene 4a with sulfur ylide 2b [Eq. (3)] delivered identical enantioselectivity (71% ee) and similar yield (80%) as the outcome from the reaction with enoldiazoacetate 1a (Table 1, entry 11) that was performed under identical conditions. These results are consistent with the donor–acceptor-substituted cyclopropene being a principal metallo-enolcarbene precursor along the pathway to product formation.

|

(3) |

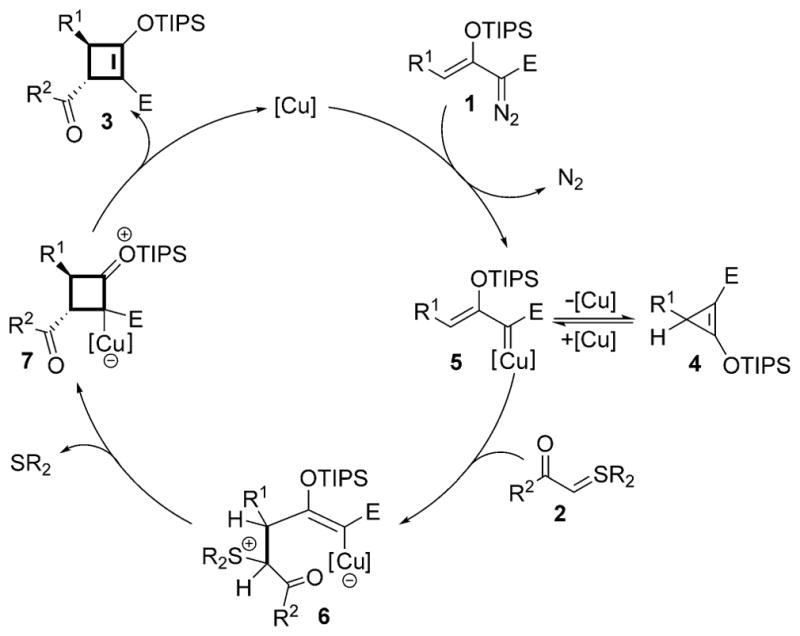

The probable mechanism for this cycloaddition reaction is described in Scheme 2. The donor–acceptor-substituted cyclopropene maintains a constant source of the reactant copper-enolcarbene intermediate (5). Nucleophilic addition of the sulfur ylide onto the electrophilic vinylogous carbon of the metal carbene generates the proposed vinylcopper intermediate (6). A striking feature of this pathway, and one not seen in previously reported metallo-vinylcarbene cycloaddition reactions, is the requirement for displacement of the R2S leaving group (6→7) rather than addition–elimination that occurs in [3+3]- and [3+2]-cycloaddition processes,[3a] which opens a new cycloaddition reaction pathway and also suggests leaving group requirements.

Scheme 2.

Mechanism of [3+1]-cycloaddition with enoldiazoacetates.

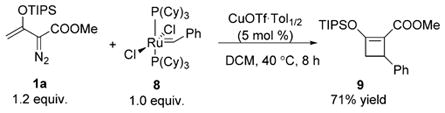

The [3+1]-cycloaddition of the metallo-enolcarbenes with sulfur ylides should be but one example of this class of reactions, dependent on the leaving group. The simple phosphorus ylide, Ph3P═CH2, is unsuitable because of the formation of triphenylphosphine. However, we envisioned that this reaction could be extended to other stable ylides, one class of which is stable metal carbenes. The [3+1]-cycloaddition of metallo-enolcarbenes was examined with a stoichiometric amount of the first-generation Grubbs catalyst 8, which is a stable metallo-benzylidene ylide.[19] As indicated in Equation (4), the [3+1]-cycloaddition of enoldiazoacetate 1a and 8 proceeded smoothly, catalyzed by copper(I) triflate, generating cyclobutene 9 in 71% yield, while no reaction with 1a occurred in the absence of catalyst. The success of the transformations of catalytically generated metallo-enolcarbenes with sulfur ylides and with stable metal carbene 8 demonstrates the potential generality of [3+1]-cycloaddition reactions between a reactive dipole and a stable ylide.

|

(4) |

In conclusion, we have established the viability of highly stereoselective [3+1]-cycloaddition processes. The reaction between β-TIPS-protected enoldiazo compounds and nucleophilic sulfur ylides, catalyzed by a chiral copper(I) triflate/double-sidearmed bisoxazoline complex catalyst, produces highly functionalized cyclobutene products with high enantio- and diastereocontrol in good yields, and we have shown that this [3+1]-cycloaddition strategy between a reactive dipole and a stable ylides has a promising generality.

Acknowledgments

Support for this research from the National Science Foundation (CHE-1464690) is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Dedicated to Professor Qilin Zhou on the occasion of his 60th birthday

Supporting information and the ORCID identification number(s) for the author(s) of this article can be found under: https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201704069.

Contributor Information

Dr. Yongming Deng, Department of Chemistry, The University of Texas at San Antonio One UTSA Circle, San Antonio, TX 78249 (USA)

Lynée A. Massey, Department of Chemistry, The University of Texas at San Antonio One UTSA Circle, San Antonio, TX 78249 (USA)

Dr. Peter Y. Zavalij, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of Maryland College Park, MD 20742 (USA)

Prof. Dr. Michael P. Doyle, Department of Chemistry, The University of Texas at San Antonio One UTSA Circle, San Antonio, TX 78249 (USA)

References

- 1.Nishiwaki N. Methods and applications of cycloaddition reactions in organic syntheses. Wiley; Hoboken: 2014. Kobayashi S, Jørgensen KA. Cycloaddition reactions in organic synthesis. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2002. Moyano A, Rios R. Chem Rev. 2011;111:4703–4832. doi: 10.1021/cr100348t.Gothelf KV, Jørgensen KA. Chem Rev. 1998;98:863–910. doi: 10.1021/cr970324e.

- 2.Fringuelli F, Taticchi A. The Diels – Alder reaction: selected practical methods. Wiley; New York: 2002. Jiang X, Wang R. Chem Rev. 2013;113:5515–5546. doi: 10.1021/cr300436a.Reymond S, Cossy J. Chem Rev. 2008;108:5359–5406. doi: 10.1021/cr078346g.Takao K-i, Munakata R, Tadano K-i. Chem Rev. 2005;105:4779–4807. doi: 10.1021/cr040632u.

- 3.a) Xu X, Doyle MP. Acc Chem Res. 2014;47:1396–1405. doi: 10.1021/ar5000055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Deng J, Wang X-N, Hsung RP. Methods and Applications of Cycloaddition Reactions in Organic Syntheses. Wiley; Hoboken: 2014. pp. 283–354. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suga H, Itoh K. Methods and Applications of Cycloaddition Reactions in Organic Syntheses. Wiley; Hoboken: 2014. pp. 175–204.Wenzel Tornøe C, Meldal M. Organic Azides. Wiley; Hoboken: 2010. pp. 285–310.Pellissier H. Tetrahedron. 2007;63:3235–3285.Hashimoto T, Maruoka K. Chem Rev. 2015;115:5366–5412. doi: 10.1021/cr5007182.

- 5.Poplata S, Tröster A, Zou Y-Q, Bach T. Chem Rev. 2016;116:9748–9815. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.a) Li C, Jiang K, Ouyang Q, Liu TY, Chen YC. Org Lett. 2016;18:2738–2741. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.6b01194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Schwarz DE, Rauchfuss TB. Chem Commun. 2000:1123–1124. [Google Scholar]

- 7.a) Dembitsky VM. J Nat Med. 2008;62:1–33. doi: 10.1007/s11418-007-0166-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Yoon TP. ACS Catal. 2013;3:895–902. doi: 10.1021/cs400088e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Dembitsky VM. Phytomedicine. 2014;21:1559–1581. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2014.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.a) Namyslo JJC, Kaufmann DE. Chem Rev. 2003;103:1485–1538. doi: 10.1021/cr010010y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Lee-Ruff E, Mladenova G. Chem Rev. 2003;103:1449–1484. doi: 10.1021/cr010013a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xu Y, Conner ML, Brown MK. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2015;54:11918–11928;. doi: 10.1002/anie.201502815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem. 2015;127:12086–12097. [Google Scholar]

- 10.a) Barluenga J, Riesgo L, Lopez LA, Rubio E, Tomas M. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:7569–7572. doi: 10.1002/anie.200903902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem. 2009;121:7705–7708. [Google Scholar]; b) Barluenga J, Riesgo L, Lonzi G, Tomas M, Lopez LA. Chem Eur J. 2012;18:9221–9224. doi: 10.1002/chem.201200998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.For recent examples, see: Cheng QQ, Yedoyan J, Arman H, Doyle MP. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:44–47. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b10860.Shved AS, Tabolin AA, Novikov RA, Nelyubina YV, Timofeev VP, Ioffe SL. Eur J Org Chem. 2016;2016:5569–5578.Smith AG, Davies HML. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:18241–18244. doi: 10.1021/ja3092399.Deng Y, Yglesias MV, Arman H, Doyle MP. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2016;55:10108–10112. doi: 10.1002/anie.201605438.Angew Chem. 2016;128:10262–10266.López E, Lonzi G, González J, López LA. Chem Commun. 2016;52:9398–9401. doi: 10.1039/c6cc04106j.Jing C, Cheng QQ, Deng Y, Arman H, Doyle MP. Org Lett. 2016;18:4550–4553. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.6b02192.Lee DJ, Ko D, Yoo EJ. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2015;54:13715–13718. doi: 10.1002/anie.201506764.Angew Chem. 2015;127:13919–13922.Zhu C, Xu G, Sun J. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2016;55:11867–11871. doi: 10.1002/anie.201606139.Angew Chem. 2016;128:12046–12050.

- 12.For recent reviews, see: Aggarwal VK, Winn CL. Acc Chem Res. 2004;37:611–620. doi: 10.1021/ar030045f.Lu LQ, Chen JR, Xiao WJ. Acc Chem Res. 2012;45:1278–1293. doi: 10.1021/ar200338s.Sun XL, Tang Y. Acc Chem Res. 2008;41:937–948. doi: 10.1021/ar800108z.Chen JR, Hu XQ, Lu LQ, Xiao WJ. Chem Rev. 2015;115:5301–5365. doi: 10.1021/cr5006974.

- 13.Qian Y, Xu X, Wang X, Zavalij PJ, Hu W, Doyle MP. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2012;51:5900–5903;. doi: 10.1002/anie.201202525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem. 2012;124:6002–6005. [Google Scholar]

- 14.a) Chen JR, Dong WR, Candy M, Pan FF, Jörres M, Bolm C. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:6924–6927. doi: 10.1021/ja301196x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Wang Q, Li TR, Lu LQ, Li MM, Zhang K, Xiao WJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:8360–8363. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b04414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.For reviews, see: Desimoni G, Faita G, Jørgensen KA. Chem Rev. 2006;106:3561–3651. doi: 10.1021/cr0505324.Liao S, Sun XL, Tang Y. Acc Chem Res. 2014;47:2260–2272. doi: 10.1021/ar800104y.

- 16.CCDC 1530514 (3a) contains the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre.

- 17.Deng Y, Jing C, Arman H, Doyle MP. Organometallics. 2016;35:3413–3420. [Google Scholar]

- 18.a) Xu X, Zavalij PY, Doyle MP. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:12439–12447. doi: 10.1021/ja406482q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Xu X, Deng Y, Yim DN, Zavalij PY, Doyle MP. Chem Sci. 2015;6:2196–2201. doi: 10.1039/c4sc03991b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Deng Y, Jing C, Doyle MP. Chem Commun. 2015;51:12924–12927. doi: 10.1039/c5cc05006e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.a) Grubbs RH. Tetrahedron. 2004;60:7117–7140. [Google Scholar]; b) Schrock RR. Chem Rev. 2002;102:145–180. doi: 10.1021/cr0103726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Dixneuf PH, Bruneau C. Handbook of Metathesis. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2015. pp. 389–416. [Google Scholar]