Abstract

Objective

To describe the daily variability and patterns of pain, fatigue, depressed mood, and cognitive function in persons with multiple sclerosis (MS).

Design

Repeated-measures observational study of seven consecutive days of home monitoring, including ecological momentary assessment (EMA) of symptoms. Multilevel mixed models were used to analyze data.

Setting

General community.

Participants

Ambulatory adults (N=107) with MS recruited through [Masked] and surrounding community.

Interventions

Not applicable.

Main Outcome Measure(s)

EMA measures of pain, fatigue, depressed mood, and cognitive function rated on a 0–10 scale, collected five times a day for seven days.

Results

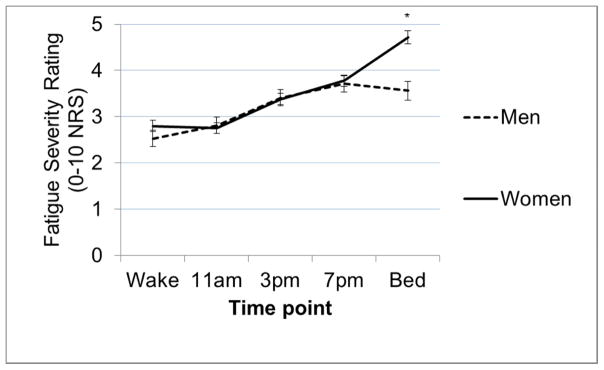

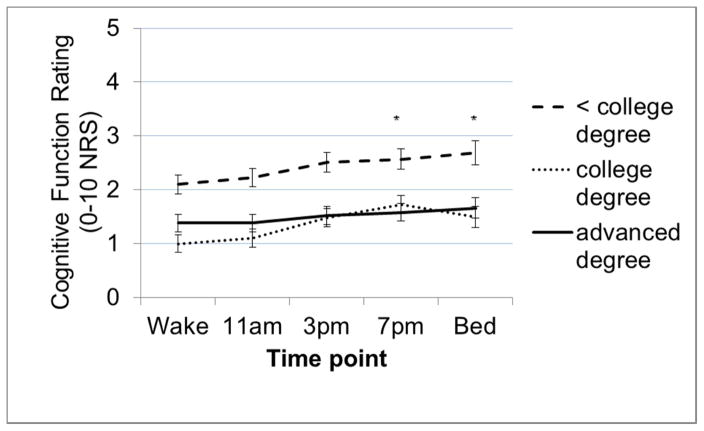

Cognitive function and depressed mood exhibited more stable within-person patterns compared to pain and fatigue, which varied considerably within-person. All symptoms increased in intensity across the day (all p<0.02) with fatigue showing the most substantial increase. Notably, this diurnal increase varied by sex and age; women showed a continuous increase from wake to bedtime, whereas fatigue plateaued after 7PM for men (wake-bed B=1.04, p=0.004). For the oldest subgroup, diurnal increases were concentrated to the middle of the day compared to younger subgroups, which showed an earlier onset of fatigue increase and sustained increases until bed time (wake-3pm B=0.04, p=0.01; wake-7pm B=0.03, p=0.02). Diurnal patterns of cognitive function varied by education; those with advanced college degrees showed a more stable pattern across the day, with significant differences compared to those with bachelor-level degrees in the evening (wake-7pm B=−0.47, p=0.02; wake-bed B=−.45, p=0.04).

Conclusions

Findings suggest that chronic symptoms in MS are not static, even over a short time frame; rather, symptoms –fatigue and pain in particular - vary dynamically across and within days. Incorporation of EMA methods should be considered in the assessment of these chronic MS symptoms to enhance assessment and treatment strategies.

Keywords: multiple sclerosis ecological momentary assessment, diurnal, pain, fatigue, depressed mood, cognitive function

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic, progressive neurological disease that causes inflammation, myelin damage and axonal destruction of the brain and spinal cord1–3. In addition to physical impairment, people with MS experience a constellation of symptoms, including chronic pain4–7, fatigue8–13, depression14–16, and cognitive dysfunction17–22. Although efforts to manage symptoms and improve functioning are mainstays of MS care, the ability to provide optimal treatment for symptoms is stymied by a poor understanding of the nature of symptoms.

Depressive symptoms23, pain24,25, and cognitive dysfunction26–28 can change over the long term in MS. Symptom variability over time is associated with emotional distress29, which has been attributed to symptom uncertainty30,31. Few studies have examined short-term (e.g. moment-to-moment) symptom variability. Studies that examined daily symptoms in MS have shown significant within-person variability in fatigue and depressed mood, with less variability for pain intensity32,33, significant individual differences in diurnal fluctuations in fatigue34, and significant daily fatigue fluctuations that are more related to physical exertion in those with compared to those without MS35. While these studies provide initial evidence as to daily symptom variability in MS, they are somewhat limited by small sample sizes32,33,35 and a focus on fatigue33,34. Greater understanding of the variability of MS symptoms could provide insight into how symptoms are experienced in daily life, inform approaches to measuring symptoms, and optimize behavioral and pharmacological treatments for symptoms in MS.

The objective of this study was to assess temporal patterns of four common symptoms (pain, fatigue, depressed mood, and cognitive function) in persons with MS using ecological momentary assessment (EMA)36,37 – real-time assessment of symptoms. EMA offers benefits over recall surveys, including improved reliability, and the ability to examine within-person dynamics36,37. In this study, we examined within-person variability and diurnal patterns in pain, fatigue, depressed mood, and cognitive function over 7 days. Based on previous findings32,34,35, we hypothesized that fatigue and depressed mood would demonstrate relatively higher levels of within-person variability compared to other symptoms and that all symptoms would exhibit a diurnal increase in severity throughout the day. We explored whether age, sex, MS subtype, MS duration, work status, and education level were related to different diurnal symptom patterns.

Methods

Participants

Adults with a clinical diagnosis of MS were recruited. Inclusion criteria were: 1) ≥ 18 years of age; 2) able to speak/read English at 6th grade level; and 3) able to ambulate with minimal assistance (use of cane/walker permitted). Exclusion criteria were: 1) MS exacerbation within the past 30 days; 2) atypical sleep/wake pattern (e.g. shift work); 3) diagnosis of rheumatologic disease or fibromyalgia; and 4) change in disease-modifying therapy during study.

Study Procedures

This study utilized baseline surveys, EMA of symptoms, and end-of-day (EOD) diaries from a study that also measured physical activityand was conducted at [masked] between October 2014 and March 2016. Medical Institutional Review Board approval was granted prior to study initiation. Participants were recruited through physician referrals, flyers placed in [masked] medical clinics and community locations, outreach at community events, electronic medical records queries, existing participant registries, and the [masked] human subjects recruitment website. Screening was conducted via telephone; eligible volunteers were scheduled for a baseline visit where they underwent informed consent, completed surveys online via Qualtrics38, and were trained to use the PRO-Diary wrist-worn monitor and complete EOD diaries through Qualtrics. The 7-day home monitoring period commenced the day following the baseline visit.

During home monitoring, participants wore the PRO-Diarya (CamNTech, Cambridge, United Kingdom) on their non-dominant wrist continuously and entered self-reported ratings of pain, fatigue, depressed mood, and cognitive function 5 times a day: upon waking, 11AM, 3PM, 7PM, and bedtime. An audible alarm alerted participants to enter ratings during the day and participant initiated ratings at wake and bed times. As detailed in the companion paper39, participants completed a brief EOD diary of validated surveys each night via a Qualtrics link. After the home monitoring period, participants returned their PRO-Diary to the lab, where data were downloaded. Participants received compensation based on the number of days that they completed.

Measures

Baseline Measures

Surveys of demographic (age, sex, race, education) and clinical (year of diagnosis) variables were administered. Physician diagnosis and MS subtype were confirmed through medical record review. Validated self-report measures were used to characterize the sample. Fatigue severity was assessed with the Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS)40, a validated 9-item measure; average scores of ≥4 are suggestive of fatigue40–44. Depressive symptoms were measured with the Patient Health Questionnaire–9 (PHQ-9)45 which assesses frequency of 9 depressive symptoms in the past 2 weeks. The PHQ-9 has been validated in MS46,47 and provides clinical cut-points. On the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI)48–51 participants rated their current, worst, and average pain intensity on a scale from 0 (no pain at all) to 10 (pain as bad as it can be). A composite score, “characteristic pain,” was calculated by multiplying the mean of these three items by ten to better captures a reliable hierarchy of pain intensity 52. Perceived cognitive functioning was assessed with the Perceived Deficits Questionnaire (PDQ)53, which asks respondents to rate how often they experienced different types of cognitive dysfunction in the past 4 weeks, on a scale from 0 (never) to 4 (almost always). Higher scores indicate greater perceived cognitive dysfunction.

Ecological Momentary Assessment

Four EMA symptom items were developed for the study due to a lack of available validated measures. Pain and fatigue items were based on the “right now” items of the BPI48–51 and the Brief Fatigue Inventory54. Items for depressive and cognitive symptoms were developed with parallel response scales to limit response burden and make for straightforward statistical comparisons.

Pain intensity was assessed with the question: “What is your level of pain right now?” rated on a scale from 0 = “no pain” to 10 = “worst pain imaginable.”

Fatigue intensity, defined as tiredness or weariness55, was assessed with the question: “What is your level of fatigue right now?” rated on a scale from 0 = “no fatigue” to 10 = “extremely severe fatigue.”

Depressed mood assessed with the question: “What is your level of depression right now?” rated on a scale from 0 = “not at all depressed” to 10 = “extremely depressed.”

Cognitive function (perceived) was assessed with the question: “What is your level of cognitive functioning right now?” rated on a scale from 0 = “good: my thinking is sharp and quick” to 10= “bad: my thinking is very difficult or slow.”

End-of-Day Diaries

Four short-forms from the Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS)56–58 or the Quality of Life in Neurological Disorders (Neuro-QoL) measurement system59,60, were adapted for daily use by changing the recall format from the past 7-days to “Today”.61 Daily Pain was assessed with the PROMIS pain intensity 3-item short-form 61,62 which has demonstrated validity across conditions63,64. Respondents rated their daily worst, average, and current pain on a 1 (no pain) to 5 (very severe) scale.

Daily Fatigue was assessed with the PROMIS fatigue 6-item short-form, which has demonstrated validity across conditions63,65,66 and ecological validity when administered in diary format67, and has been linked to legacy fatigue measures in MS66. Respondents rated general, mental, and physical fatigue, and fatigue impact on a 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much) scale.

Daily Depressed Mood was assessed with the PROMIS 8-item short-form, which has been validated in MS46. Respondents rated eight depressed feelings on a scale from 1 (never) to 5 (always).

Daily Cognitive Function was assessed with the Neuro-QoL 6-item applied cognition-general concerns short-form. Respondents rated perceived cognitive difficulty on a scale of 1 (never) to 5 (always).

Data Analyses

Preliminary Data Analyses

Descriptive statistics for all variables and missing data rates were calculated. To examine convergent validity of EMA items, we used multilevel modeling (MLM), regressing the EOD diary score on the corresponding EMA symptom variable (daily aggregate) and calculating the amount of shared variance (pseudo-R2) between the measures for each symptom68. Shared variance ≥49% (roughly corresponding to r=0.70) was considered evidence of convergent validity of the EMA items.

Primary Data Analyses

To calculate within- and between-person variability, we ran “null” MLMs (i.e., SAS PROC MIXED) for each of the four symptoms, with no covariates and the symptom variable under consideration as criterion. We calculated the proportion of variance accounted for by the intercept, indicating between-person variance (i.e., intraclass correlation), and residual variance, indicating within-person variance. We created a ratio of these variance estimates. In MLMs that examined diurnal symptom changes across the day; we tested the effects of time point, treated as a categorical variable with wake as the reference, to determine whether symptoms changed between wake and bed times. To test whether diurnal symptom patterns varied based on age, sex. MS subtype (relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS) versus progressive subtypes), MS duration, work status, or education level, interaction terms were created and entered as predictor variables into MLMs where the criterion was one of the EMA symptoms. Significant interactions were graphed to aid interpretation. Analyses were completed using SASb version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Critical alpha level was 0.05.

Results

One hundred and eight participants enrolled and completed the baseline surveys. One participant withdrew before starting home monitoring; data from the remaining 107 were analyzed. Descriptive statistics (Table 1) indicate that the sample, on average, was middle-aged and most were female, white, and had RRMS. Data were adequately normally-distributed for parametric statistical analyses. For EMA measures, 83.4% (3,145/3,745[35*107]) of the data were complete; 17 participants had no missing data and 55 had ≤3 missing data points. Mean number of missing EMA data points was 5.79 ± 6.35.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for demographic and baseline study variables (N = 107)

| Variable (possible range) | N (%) | Mean (SD) | Min-Max |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years | 45.16 (11.73) | 23–67 | |

| MS Duration in years | 9.49 (8.36) | <1 –44 | |

| FSS (1–7) | 4.94 (1.53) | 1–7 | |

| Significant fatigue; scores 4–7 | 85 (79.4%) | ||

| BPI worst pain (0–10) | 4.09 (2.92) | 0–10 | |

| BPI average pain (0–10) | 3.09 (2.17) | 0–7 | |

| BPI current pain (0–10) | 2.67 (2.48) | 0–8 | |

| Characteristic Pain (0–100) | 32.99 (23.56) | 0–80 | |

| Significant pain; scores 40–100 | 46 (42.9%) | ||

| PDQ (0–80) | 28.92 (17.53) | 0–74 | |

| PHQ-9 Total Score (0–27) | 7.61 (5.91) | 0–22 | |

| PHQ-9 categories | |||

| Minimal depression | 42 (39.3%) | ||

| Mild depression | 29 (27.1%) | ||

| Moderate depression | 21 (19.6%) | ||

| Moderately severe depression | 10 (9.3%) | ||

| Severe depression | 5 (4.7%) | ||

| Sex (Female) | 74 (69.2%) | ||

| MS Subtype | |||

| Relapsing Remitting | 78 (72.9%) | ||

| Primary Progressive | 14 (13.1%) | ||

| Progressive Relapsing | 2 (1.9%) | ||

| Secondary Progressing | 13 (12.1%) | ||

| Race | |||

| White | 88 (82.2%) | ||

| Black | 10 (10.7%) | ||

| Asian | 6 (5.6%) | ||

| Native | 2 (1.9%) | ||

| Biracial (Black/White) | 1 (0.9%) | ||

| Hispanic | 1 (0.9%) | ||

| Employment | |||

| Employed Full-time | 41 (38.3%) | ||

| Employed Part-Time | 19 (17.8%) | ||

| Unemployed | 47 (43.9%) | ||

| Education | |||

| Some high school | 1 (0.9%) | ||

| HS grad/GED | 13 (12.1%) | ||

| Vocational or Tech school | 2 (1.9%) | ||

| Some College | 26 (24.3%) | ||

| College Grad | 41 (38.3%) | ||

| Graduate school/Prof school | 24 (22.4%) | ||

Note. GED = General educational development; FSS = Fatigue Severity Scale; BPI = Brief Pain Inventory; PHQ-9 = Patient Health Questionnaire – 9; Perceived Deficits Questionnaire.

All EMA measures showed high levels of shared variance with EOD diary measures of the same constructs, supporting convergent validity of the EMA items (Table 2.).

Table 2.

Results of multilevel models examining the association and shared between-person variance for daily EMA symptom ratings (daily aggregates) and EOD diary survey scores of the same symptom construct

| beta | SE | p | Shared variance* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Pain (df = 101, 516) | ||||

| EMA pain (daily aggregate) | 0.91 | 0.05 | <0.0001 | 79.8% |

| EOD diary PROMIS pain intensity (criterion) | ||||

| Fatigue (df = 101, 516) | ||||

| EMA fatigue (daily aggregate) | 1.35 | 0.09 | <0.0001 | 63.3% |

| EOD diary PROMIS fatigue (criterion) | ||||

| Depressed mood (df = 101, 515) | ||||

| EMA depressed mood (daily aggregate) | 2.05 | 0.30 | <0.0001 | 59.2% |

| EOD diary PROMIS depressive symptoms (criterion) | ||||

| Cognitive function (df = 101, 511) | ||||

| EMA cognitive function (daily aggregate) | 1.27 | 0.17 | <0.0001 | 54.2% |

| EOD diary Neuro-QoL applied cognition-concerns | ||||

Note. EMA = ecological momentary assessment; EOD = end-of-day; PROMIS = Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System; Neuro-QoL = Quality of Life in Neurological Disorders measurement system; df = degrees of freedom between and within-person; beta = unstandardized beta; SE=standard error; p = significance level;

pseudo-R2 calculated according to the recommendations of Singer & Willett65;

Examination of between- and within-person variance components of symptoms

As shown in Table 3, the proportion of within-person and between-person variance in fatigue was equal (50%/50%). In contrast, the between-person variance for pain accounted for a relatively larger proportion of the variance (59%), as compared to within-person variance (41%). For cognitive function, within-person variance accounted for only 36% (64% between-person variance) of the total variance. Depressed mood had the smallest proportion of within-person variance (31%), with 69% of the variance being between-person. While all symptoms demonstrated notable levels of within-person variability, fatigue demonstrated the largest proportion and depressed mood the smallest proportion of within-person variability.

Table 3.

Within- and between-person variance in momentary ratings of fatigue, pain, depressed mood, and cognitive functioning

| Pain | Fatigue | Depressed mood | Cognitive Functioning | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Between-person | 2.89 | 3.54 | 2.54 | 2.99 |

|

|

||||

| Within-person | 1.99 | 3.60 | 1.15 | 1.68 |

| Percent Between-person | 59% | 50% | 69% | 64% |

| Percent Within-person | 41% | 50% | 31% | 36% |

Diurnal symptom patterns

As expected, all symptoms increased steadily and significantly from wake to bed time (See Figure 1 and Table 4). In Figure 2, a single illustrative case demonstrates both the differences in proportion of between-and within-person variance components as well as the diurnal effects of symptoms.

Figure 1.

Diurnal patterns of symptom ratings across the day represented by sample averages for symptoms at each time point, showing a steady increase in all symptoms from wake to bedtime across the sample.

Note. error bars = standard error of the mean

Table 4.

Results of multilevel model tests of diurnal effects of time in symptom ratings, showing significant increases at each time point relative to the wake time point (reference)

| Time point | Pain | Fatigue | Depressed mood | Cognitive function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (unstandardized beta, p) | ||||

|

| ||||

| Wake (reference) | - | - | - | - |

| 11AM | 0.16, 0.13 | −.11, 0.47 | 0.22, 0.0002 | 0.05, 0.56 |

| 3PM | 0.26, 0.02 | 0.48, 0.006 | 0.33, <0.0001 | 0.30, 0.008 |

| 7PM | 0.51, < 0.0001 | 0.85, <0.0001 | 0.42, <0.0001 | 0.39, 0.0009 |

| Bed time | 0.29, 0.03 | 1.75, <0.0001 | 0.29, 0.0002 | 0.43, 0.005 |

Figure 2.

Single case example (25 year old female with relapsing-remitting MS) of variability in momentary symptoms across 7 days

Note. Fatigue (red line) shows the most obvious within-person fluctuations, with peak values around bed time (corresponding to every fifth tick mark, marked with “B” on horizontal axis). In comparison, pain (blue line) shows slightly less variation across the days, but more variation than cognitive function (purple line) and depressed mood (green line), which shows almost no variability across the entire study period. This single-case example demonstrates both the differences between the symptoms in degree of within-person variability as well as the diurnal effects (evidenced by symptom peaks at bedtime (“B”) and symptom valleys at wake (“W”).

Individual differences in diurnal symptom patterns

Diurnal symptom patterns did not differ by MS subtype/duration or work status (all p>0.13). There was a significant difference by age in change in fatigue ratings from wake to 3PM (ageXtime B=0.04, SE=0.01, t=2.44, p=0.01) and from wake to 7PM (ageXtime B=0.03, SE=0.01, t=2.29, p=0.02). A graph of fatigue ratings across the day (Figure 3) shows that among the youngest (23–38 years; 33% of sample) and middle-aged (39–52yrs; 33%) groups, fatigue largely plateaus from wake to 11AM, followed by a modest, steady increase toward bed time. In contrast, among the oldest group (53–67 years; 33%), fatigue ratings were relatively stable from wake to 3PM, but then steeply increased from 3PM to 7PM before stabilizing. There was one significant finding for sex; there was a significant difference between men and women in terms of the change from waking to bedtime fatigue (sexXtime B=1.04, SE=0.36, t =2.92, p=0.004). A graph of fatigue ratings across the day (Figure 4) shows that while fatigue rises steadily across the day and peaks at bedtime for women, fatigue ratings plateau at 7PM and decline toward bedtime for men. There was a significant difference in the diurnal pattern of cognitive function by education level; those with an advanced degree were significantly different from those with a college education in terms of changes from wake to 7PM (educationXtime B=−0.47, SE=0.22, p=0.02) and from wake to bedtime (educationXtime B=−0.45, SE=0.22, p=0.04). A graph of cognitive function ratings (Figure 5) shows that in the context of overall very modest diurnal effects for all levels of education, those with advanced degrees showed the most stable and those with a college education the most variable diurnal pattern.

Figure 3.

Difference by age categories (youngest = 23–38 years; middle = 39–52 years; oldest = 53–67 years) in the diurnal pattern (change across the day) of fatigue ratings. Lines depict average fatigue ratings at each time point for the different age groups.

Note. error bars = standard error of the mean: * = time point at which change in fatigue from wake time point is significantly different by sex.

Figure 4.

Differences between men and women in the diurnal pattern (change across the day) of fatigue ratings. Lines depict average fatigue ratings at each time point for men and women.

Note. error bars = standard error of the mean; * = time points at which change in fatigue from wake time point is significantly different by age.

Figure 5.

Differences by education categories (<college degree = 38.9%, college degree = 28.9%, advanced degree = 22.2%) in the diurnal pattern (change across the day) of cognitive function ratings. Lines depict average cognitive functioning ratings (higher scores indicate worse function) at each time point for each education level category.

Note. error bars = standard error of the mean; * = time points at which change in cognitive function from wake time point is significantly different by education.

Discussion

This study is the first to use EMA to examine daily variability and temporal patterns of pain, fatigue, depressed mood, and perceived cognitive function in MS. Consistent with previous research32,34,35, these data show that in ambulatory people with MS, symptoms are not static, but are experienced dynamically. Fatigue emerged as the most variable symptom, with a high ratio of within- to between-person variability, and the greatest change from wake to bed time. Unexpectedly, depressed mood was the most static symptom; it is plausible that this lack of variability may be due to low levels of depressed mood in the sample. However, levels of other symptoms were also modest and yet demonstrated higher within-person variability. People with MS often experience considerable disease course-variability and illness uncertainty, which are associated with emotional distress29–31,69. Whether daily symptom variability and uncertainty could add to distress associated with illness uncertainty across longer time spans has yet to be explored. Our findings highlight a potential role for assessment and integration of thoughts, behaviors, and emotions related to symptom variability and unpredictability, which may need to be incorporated into self-management interventions for MS symptoms.

As anticipated, all symptoms showed a significant worsening across the day, although, on average, diurnal increases were modest. Diurnal fatigue patterns varied by age and sex/Older individuals showed a delay in the onset of fatigue worsening, and women showed a continuous worsening of fatigue that peaked at the end of the day. In contrast, men’s fatigue plateaued at 7PM. Different fatigue patterns by age may be due to increased use of planning and activity pacing70 in older individuals, to account for greater fatigability71. These findings are consistent with a previous study suggesting significant individual differences in diurnal fatigue patterns34 and suggest a need to further explore individual differences in the experiences of symptoms, and identification of prototypical symptom profiles, which could offer the ability to tailor treatments based on a person’s “symptom phenotype”. These data have implications for energy conservation, a common behavioral strategy based on the premise that people need to “budget” energy, suggesting that that clinicians should consider individual differences by age and sex in daily fatigue and the potential that pacing may be naturally occurring, especially in older persons with MS72. Diurnal cognitive functioning patterns differed by education with those with advanced degrees showing almost no change in perceived cognition across the day; in contrast, those with lower education showed worsening of cognitive function across the day, although these increases are modest and significantly different only in the evening for those with college degrees vs. advanced degrees. Notably, those with at least a college degree reported lower levels of cognitive problems across the day compared with those with less than a college education. This finding is somewhat consistent with previous findings supporting the cognitive reserve hypothesis, that higher education mitigates cognitive problems associated with MS73–75.

Average EMA ratings were low, particularly when compared to scores on standardized symptom measures that suggest a higher symptom burden. This incongruity between EMA and baseline survey scores could be due to a number of factors. Methodological studies of EMA of symptoms demonstrate surveys that rely on respondent recall, such as the baseline measures in this study, are biased toward peak (worst) and recent symptoms76–78; EMA ratings may provide a more valid estimate of true symptom intensity compared to standardized surveys. Additionally, people may respond differently to an in-the-moment compared to a recall question about symptoms, such that responding in real-time shifts or constricts the range of responses or reflects a different construct altogether. These possibilities warrant further examination to improve the psychometric characteristics and clinical usefulness (e.g. comparability to screening measures) of EMA measures.

These novel findings warrant replication in larger and more diverse MS samples and call for a number of future directions, some of which we are examining in these data, including moment-to-moment and day-to-day covariation of symptoms 79, daily association of symptoms to functional and affective outcomes39, and the association between symptoms and physical activity.

Study Limitations

Because this study focused on symptoms that are common targets of behavioral self-management interventions, evaluation of other MS symptoms, such as weakness and sensory disturbances were not included. Only ambulatory individuals were included due to the use of an accelerometer;exclusion of the most disabled individuals could limit our ability to generalize findings to the broader MS population. Use of single item measures that have not been validated to assess momentary symptoms is a limitation of this study. Although there are examples of 0–10 numerical rating scale use in EMA studies of pain80–82 and fatigue33,35,82, to our knowledge there are no standard, validated EMA measures of the symptoms examined in this study. Convergent validity of the EMA items, relative to more robust daily measures of each construct, was supported in this study. Further work to psychometrically evaluate EMA symptom measures is needed, with the goal of developing standard validated EMA items and brief scales that could be used across studies. Examination of individual differences in symptom experience (versus group-level analyses) as well as how total symptom burden (versusindividual symptoms) in future research could better reflect the true experience of symptoms in MS; unfortunately, our relatively small sample precludes the type of data modeling that would be required to examine these question. Comparing daily symptom experience and impact in MS to other clinical conditions or to healthy individuals could provide additional insights as to how the symptoms experience is unique in MS, similar to a recent study showing that physical exertion is related to fatigue in MS whereas sleep quality is related to fatigue in healthy controls35.

Conclusions

Findings add to the growing body of evidence that chronic symptoms in MS are not static, but change daily within a person. Improved knowledge of symptom patterns in MS could help refine interventions to target the most severe or impactful symptoms, minimize treatments when they are not needed, develop new interventions and prevention strategies, and guide timing of medications and selection of self-management strategies83. Results highlight the potential of EMA to provide a reliable real-time assay of MS symptoms, which could increase our understanding of MS symptoms, and gauge effectiveness of symptomatic therapies for some of the most common and consequential MS symptoms.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding: Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Nursing Research of the National Institutes of Health under award number R03NR014515; PI: Kratz. Dr. Kratz was supported during manuscript preparation by a grant from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (award number 1K01AR064275). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The manuscript submitted does not contain information about medical device(s).

Abbreviations

- EMA

ecological momentary assessment

- EOD

end-of-day

- MS

multiple sclerosis

- RRMS

Relapsing-Remitting MS

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

CamNtech Ltd., Upper Pendrill Court, Ermine Street North, Papworth Everard, Cambridge, CB23 3UY, United Kingdom

SAS, SAS Campus Drive, Building T, Cary, NC 27513

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hauser SL, Oksenberg JR. The neurobiology of multiple sclerosis: genes, inflammation, and neurodegeneration. Neuron. 2006 Oct 5;52(1):61–76. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Noseworthy JH. Progress in determining the causes and treatment of multiple sclerosis. Nature. 1999 Jun 24;399(6738 Suppl):A40–47. doi: 10.1038/399a040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Noseworthy JH, Lucchinetti C, Rodriguez M, Weinshenker BG. Multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2000 Sep 28;343(13):938–952. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200009283431307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ehde DM, Gibbons LE, Chwastiak L, Bombardier CH, Sullivan MD, Kraft GH. Chronic pain in a large community sample of persons with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2003 Dec;9(6):605–611. doi: 10.1191/1352458503ms939oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ehde DM, Osborne TL, Hanley MA, Jensen MP, Kraft GH. The scope and nature of pain in persons with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2006 Oct;12(5):629–638. doi: 10.1177/1352458506071346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ehde DM, Osborne TL, Jensen MP. Chronic pain in persons with multiple sclerosis. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2005 May;16(2):503–512. doi: 10.1016/j.pmr.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hirsh AT, Turner AP, Ehde DM, Haselkorn JK. Prevalence and impact of pain in multiple sclerosis: physical and psychologic contributors. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009 Apr;90(4):646–651. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2008.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kos D, Kerckhofs E, Nagels G, D’Hooghe MB, Ilsbroukx S. Origin of fatigue in multiple sclerosis: review of the literature. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2008 Jan-Feb;22(1):91–100. doi: 10.1177/1545968306298934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krupp LB. Fatigue in multiple sclerosis: definition, pathophysiology and treatment. CNS Drugs. 2003;17(4):225–234. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200317040-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krupp LB, Alvarez LA, LaRocca NG, Scheinberg LC. Fatigue in multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol. 1988 Apr;45(4):435–437. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1988.00520280085020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krupp LB, Christodoulou C. Fatigue in multiple sclerosis. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2001 May;1(3):294–298. doi: 10.1007/s11910-001-0033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krupp LB, Serafin DJ, Christodoulou C. Multiple sclerosis-associated fatigue. Expert Rev Neurother. 2010 Sep;10(9):1437–1447. doi: 10.1586/ern.10.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.MacAllister WS, Krupp LB. Multiple sclerosis-related fatigue. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2005 May;16(2):483–502. doi: 10.1016/j.pmr.2005.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Joy JE, Johnston RB. Multiple Sclerosis: Current Status and Strategies for the Future. National Academies Press; The National Academies: 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hadjimichael O, Kerns RD, Rizzo MA, Cutter G, Vollmer T. Persistent pain and uncomfortable sensations in persons with multiple sclerosis. Pain. 2007 Jan;127(1–2):35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khan F, Pallant J. Chronic pain in multiple sclerosis: prevalence, characteristics, and impact on quality of life in an Australian community cohort. J Pain. 2007 Aug;8(8):614–623. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Amato MP, Ponziani G, Siracusa G, Sorbi S. Cognitive dysfunction in early-onset multiple sclerosis: a reappraisal after 10 years. Arch Neurol. 2001 Oct;58(10):1602–1606. doi: 10.1001/archneur.58.10.1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bagert B, Camplair P, Bourdette D. Cognitive dysfunction in multiple sclerosis: natural history, pathophysiology and management. CNS Drugs. 2002;16(7):445–455. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200216070-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chiaravalloti ND, DeLuca J. Cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis. Lancet Neurol. 2008 Dec;7(12):1139–1151. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70259-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huijbregts SC, Kalkers NF, de Sonneville LM, de Groot V, Reuling IE, Polman CH. Differences in cognitive impairment of relapsing remitting, secondary, and primary progressive MS. Neurology. 2004 Jul 27;63(2):335–339. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000129828.03714.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kesselring J, Klement U. Cognitive and affective disturbances in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol. 2001 Mar;248(3):180–183. doi: 10.1007/s004150170223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lazeron RH, Boringa JB, Schouten M, et al. Brain atrophy and lesion load as explaining parameters for cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2005 Oct;11(5):524–531. doi: 10.1191/1352458505ms1201oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arnett PA, Randolph JJ. Longitudinal course of depression symptoms in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006 May;77(5):606–610. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2004.047712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brochet B, Deloire MS, Ouallet JC, et al. Pain and quality of life in the early stages after multiple sclerosis diagnosis: a 2-year longitudinal study. The Clinical journal of pain. 2009 Mar-Apr;25(3):211–217. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e3181891347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khan F, Amatya B, Kesselring J. Longitudinal 7-year follow-up of chronic pain in persons with multiple sclerosis in the community. J Neurol. 2013 Aug;260(8):2005–2015. doi: 10.1007/s00415-013-6925-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Amato MP, Zipoli V, Portaccio E. Multiple sclerosis-related cognitive changes: a review of cross-sectional and longitudinal studies. J Neurol Sci. 2006 Jun 15;245(1–2):41–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2005.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Piras MR, Magnano I, Canu ED, et al. Longitudinal study of cognitive dysfunction in multiple sclerosis: neuropsychological, neuroradiological, and neurophysiological findings. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003 Jul;74(7):878–885. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.74.7.878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Denney DR, Lynch SG, Parmenter BA. A 3-year longitudinal study of cognitive impairment in patients with primary progressive multiple sclerosis: speed matters. J Neurol Sci. 2008 Apr 15;267(1–2):129–136. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Randolph JJ, Arnett PA. Depression and fatigue in relapsing-remitting MS: the role of symptomatic variability. Mult Scler J. 2005;11(2):186–190. doi: 10.1191/1352458505ms1133oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kroencke DC, Denney DR, Lynch SG. Depression during exacerbations in multiple sclerosis: the importance of uncertainty. Mult Scler. 2001 Aug;7(4):237–242. doi: 10.1177/135245850100700405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kroencke DC, Denney DR. Stress and coping in multiple sclerosis: exacerbation, remission and chronic subgroups. Mult Scler. 1999 Apr;5(2):89–93. doi: 10.1177/135245859900500204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kasser SL, Goldstein A, Wood PK, Sibold J. Symptom variability, affect and physical activity in ambulatory persons with multiple sclerosis: Understanding patterns and time-bound relationships. Disabil Health J. 2016 Oct 17; doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2016.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim E, Lovera J, Schaben L, Melara J, Bourdette D, Whitham R. Novel method for measurement of fatigue in multiple sclerosis: Real-Time Digital Fatigue Score. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2010;47(5):477–484. doi: 10.1682/jrrd.2009.09.0151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heine M, van den Akker LE, Blikman L, et al. Real-Time Assessment of Fatigue in Patients With Multiple Sclerosis: How Does It Relate to Commonly Used Self-Report Fatigue Questionnaires? Arch Phys Med Rehab. 2016 Nov;97(11):1887–1894. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2016.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Powell DJ, Liossi C, Schlotz W, Moss-Morris R. Tracking daily fatigue fluctuations in multiple sclerosis: ecological momentary assessment provides unique insights. J Behav Med. 2017 Mar 09; doi: 10.1007/s10865-017-9840-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shiffman S, Stone AA, Hufford MR. Ecological momentary assessment. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2008;4:1–32. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stone AA, Shiffman S. Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) in behavioral medicine. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 1994;16(3):199–202. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Qualtrics. Qualtrics Security White Paper: Why should I trust Qualtrics with my Sensitive Data? [pdf] 2011. [Accessed July 3, 2014]. Version 1.0. [Google Scholar]

- 39.masked. How do pain, fatigue, depressive, and cognitive symptoms relate to well-being and social and physical functioning in the daily lives of in individuals with multiple sclerosis? Arch Phys Med Rehab. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2017.07.004. under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Krupp LB, LaRocca NG, Muir-Nash J, Steinberg AD. The fatigue severity scale. Application to patients with multiple sclerosis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Arch Neurol. 1989 Oct;46(10):1121–1123. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1989.00520460115022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Learmonth YC, Dlugonski D, Pilutti LA, Sandroff BM, Klaren R, Motl RW. Psychometric properties of the Fatigue Severity Scale and the Modified Fatigue Impact Scale. Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 2013 Aug 15;331(1–2):102–107. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2013.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lerdal A, Johansson S, Kottorp A, von Koch L. Psychometric properties of the Fatigue Severity Scale: Rasch analyses of responses in a Norwegian and a Swedish MS cohort. Mult Scler J. 2010 Jun;16(6):733–741. doi: 10.1177/1352458510370792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mills RJ, Young CA, Nicholas RS, Pallant JF, Tennant A. Rasch analysis of the Fatigue Severity Scale in multiple sclerosis. Multiple Sclerosis. 2009 Jan;15(1):81–87. doi: 10.1177/1352458508096215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mills RJ, Nicholas RS, Malik O, Young CA. Rasch analysis of the fatigue severity scale in multiple sclerosis. European Journal of Neurology. 2007 Aug;14:285–285. doi: 10.1177/1352458508096215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of general internal medicine. 2001 Sep;16(9):606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Amtmann D, Kim J, Chung H, et al. Comparing CESD-10, PHQ-9, and PROMIS depression instruments in individuals with multiple sclerosis. Rehabil Psychol. 2014 May;59(2):220–229. doi: 10.1037/a0035919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sjonnesen K, Berzins S, Fiest KM, et al. Evaluation of the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) as an assessment instrument for symptoms of depression in patients with multiple sclerosis. Postgraduate medicine. 2012 Sep;124(5):69–77. doi: 10.3810/pgm.2012.09.2595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cleeland CS. Measurement of pain by subjective report. In: Chapman CR, Loeser JD, editors. Advances in Pain Research and Therapy. Vol. 12. New York, NY: Raven Press; 1989. pp. 391–403. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cleeland CS, Ryan KM. Pain assessment: global use of the Brief Pain Inventory. Annals of the Academy of Medicine, Singapore. 1994 Mar;23(2):129–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Osborne TL, Jensen MP, Ehde DM, Hanley MA, Kraft G. Psychosocial factors associated with pain intensity, pain-related interference, and psychological functioning in persons with multiple sclerosis and pain. Pain. 2007 Jan;127(1–2):52–62. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Osborne TL, Raichle KA, Jensen MP, Ehde DM, Kraft G. The reliability and validity of pain interference measures in persons with multiple sclerosis. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2006 Sep;32(3):217–229. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Von Korff M, Ormel J, Keefe FJ, Dworkin SF. Grading the severity of chronic pain. Pain. 1992 Aug;50(2):133–149. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(92)90154-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sullivan JJL, Edgley K, Dehoux E. A survey of multiple sclerosis. Part 1: Perceived cognitive problems and compensatory strategy use. Canadian Journal of Rehabilitation. 1990;4:99–105. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mendoza TR, Wang XS, Cleeland CS, et al. The rapid assessment of fatigue severity in cancer patients: use of the Brief Fatigue Inventory. Cancer. 1999 Mar 01;85(5):1186–1196. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19990301)85:5<1186::aid-cncr24>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wolfe F, Hawley DJ, Wilson K. The prevalence and meaning of fatigue in rheumatic disease. J Rheumatol. 1996 Aug;23(8):1407–1417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cella D, Riley W, Stone A, et al. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005–2008. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2010 Nov;63(11):1179–1194. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cook KF, Jensen SE, Schalet BD, et al. PROMIS measures of pain, fatigue, negative affect, physical function, and social function demonstrated clinical validity across a range of chronic conditions. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2016 May;73:89–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.08.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rothrock NE, Hays RD, Spritzer K, Yount SE, Riley W, Cella D. Relative to the general US population, chronic diseases are associated with poorer health-related quality of life as measured by the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2010 Nov;63(11):1195–1204. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cella D, Lai JS, Nowinski CJ, et al. Neuro-QOL: brief measures of health-related quality of life for clinical research in neurology. Neurology. 2012 Jun 05;78(23):1860–1867. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318258f744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gershon RC, Lai JS, Bode R, et al. Neuro-QOL: quality of life item banks for adults with neurological disorders: item development and calibrations based upon clinical and general population testing. Qual Life Res. 2012 Apr;21(3):475–486. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-9958-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schneider S, Choi SW, Junghaenel DU, Schwartz JE, Stone AA. Psychometric characteristics of daily diaries for the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS(R)): a preliminary investigation. Qual Life Res. 2012 Nov 23; doi: 10.1007/s11136-012-0323-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chen WH, Revicki DA, Amtmann D, Jensen MP, Keefe FJ, Cella D. Development and Analysis of PROMIS Pain Intensity Scale. Qual Life Res. 2012 Jan;20:18–18. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cook KF, Jensen SE, Schalet BD, et al. PROMIS measures of pain, fatigue, negative affect, physical function, and social function demonstrated clinical validity across a range of chronic conditions. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2016 May;73:89–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.08.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cook KF, Schalet BD, Kallen MA, Rutsohn JP, Cella D. Establishing a common metric for self-reported pain: linking BPI Pain Interference and SF-36 Bodily Pain Subscale scores to the PROMIS Pain Interference metric. Qual Life Res. 2015 Oct;24(10):2305–2318. doi: 10.1007/s11136-015-0987-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Christodoulou C, Schneider S, Junghaenel DU, Broderick JE, Stone AA. Measuring daily fatigue using a brief scale adapted from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS (R)) Qual Life Res. 2014 May;23(4):1245–1253. doi: 10.1007/s11136-013-0553-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Noonan VK, Cook KF, Bamer AM, Choi SW, Kim J, Amtmann D. Measuring fatigue in persons with multiple sclerosis: creating a crosswalk between the Modified Fatigue Impact Scale and the PROMIS Fatigue Short Form. Qual Life Res. 2012 Sep;21(7):1123–1133. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-0040-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Stone AA, Broderick JE, Junghaenel DU, Schneider S, Schwartz JE. PROMIS fatigue, pain intensity, pain interference, pain behavior, physical function, depression, anxiety, and anger scales demonstrate ecological validity. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2016 Jun;74:194–206. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Singer JD, Willett JB. Applied longitudinal data analysis: Modeling change and event occurrence. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mullins LL, Cote MP, Fuemmeler BF, Jean VM, Beatty WW, Paul RH. Illness intrusiveness, uncertainty, and distress in individuals with multiple sclerosis. Rehabilitation Psychology. 2001 May;46(2):139–153. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dilorenzo TA, Becker-Feigeles J, Halper J, Picone MA. A qualitative investigation of adaptation in older individuals with multiple sclerosis. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2008;30(15):1088–1097. doi: 10.1080/09638280701464256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Eldadah BA. Fatigue and fatigability in older adults. PM & R: the journal of injury, function, and rehabilitation. 2010 May;2(5):406–413. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2010.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Murphy SL, Kratz AL. Activity pacing in daily life: A within-day analysis. Pain. 2014 Dec;155(12):2630–2637. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2014.09.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sumowski JF, Wylie GR, Deluca J, Chiaravalloti N. Intellectual enrichment is linked to cerebral efficiency in multiple sclerosis: functional magnetic resonance imaging evidence for cognitive reserve. Brain. 2010 Feb;133(Pt 2):362–374. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sumowski JF, Chiaravalloti N, Wylie G, Deluca J. Cognitive reserve moderates the negative effect of brain atrophy on cognitive efficiency in multiple sclerosis. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2009 Jul;15(4):606–612. doi: 10.1017/S1355617709090912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sumowski JF, Leavitt VM. Cognitive reserve in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2013 Aug;19(9):1122–1127. doi: 10.1177/1352458513498834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Schneider S, Stone AA, Schwartz JE, Broderick JE. Peak and End Effects in Patients’ Daily Recall of Pain and Fatigue: A Within-Subjects Analysis. Journal of Pain. 2011 Feb;12(2):228–235. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Stone AA, Schwartz JE, Broderick JE, Shiffman SS. Variability of momentary pain predicts recall of weekly pain: A consequence of the peak (or salience) memory heuristic. Pers Soc Psychol B. 2005 Oct;31(10):1340–1346. doi: 10.1177/0146167205275615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Stone AA, Broderick JE, Kaell AT, DelesPaul PAEG, Porter LE. Does the peak-end phenomenon observed in laboratory pain studies apply to real-world pain in rheumatoid arthritics? Journal of Pain. 2000 Fal;1(3):212–217. doi: 10.1054/jpai.2000.7568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.masked. Temporal associations between pain, fatigue, depressive, and cognitive symptoms within- and across-days in multiple sclerosis. Arch Phys Med Rehab. under review. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Heapy A, Dziura J, Buta E, Goulet J, Kulas JF, Kerns RD. Using multiple daily pain ratings to improve reliability and assay sensitivity: how many is enough? J Pain. 2014 Dec;15(12):1360–1365. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2014.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kratz AL, Ehde DM, Bombardier CH, Kalpakjian CZ, Hanks RA. Pain Acceptance Decouples the Momentary Associations Between Pain, Pain Interference, and Physical Activity in the Daily Lives of People With Chronic Pain and Spinal Cord Injury. J Pain. 2016 Dec 02; doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2016.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Murphy SL, Smith DM, Clauw DJ, Alexander NB. The impact of momentary pain and fatigue on physical activity in women with osteoarthritis. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2008;59(6):849–856. doi: 10.1002/art.23710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Allen KD. The value of measuring variability in osteoarthritis pain. J Rheumatol. 2007 Nov;34(11):2132–2133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]