Abstract

AIM

To determine percentage of patients of necrotizing pancreatitis (NP) requiring intervention and the types of interventions performed. Outcomes of patients of step up necrosectomy to those of direct necrosectomy were compared. Operative mortality, overall mortality, morbidity and overall length of stay were determined.

METHODS

After institutional ethics committee clearance and waiver of consent, records of patients of pancreatitis were reviewed. After excluding patients as per criteria, epidemiologic and clinical data of patients of NP was noted. Treatment protocol was reviewed. Data of patients in whom step-up approach was used was compared to those in whom it was not used.

RESULTS

A total of 41 interventions were required in 39% patients. About 60% interventions targeted the pancreatic necrosis while the rest were required to deal with the complications of the necrosis. Image guided percutaneous catheter drainage was done in 9 patients for infected necrosis all of whom required further necrosectomy and in 3 patients with sterile necrosis. Direct retroperitoneal or anterior necrosectomy was performed in 15 patients. The average time to first intervention was 19.6 d in the non step-up group (range 11-36) vs 18.22 d in the Step-up group (range 13-25). The average hospital stay in non step-up group was 33.3 d vs 38 d in step up group. The mortality in the step-up group was 0% (0/9) vs 13% (2/15) in the non step up group. Overall mortality was 10.3% while post-operative mortality was 8.3%. Average hospital stay was 22.25 d.

CONCLUSION

Early conservative management plays an important role in management of NP. In patients who require intervention, the approach used and the timing of intervention should be based upon the clinical condition and local expertise available. Delaying intervention and use of minimal invasive means when intervention is necessary is desirable. The step-up approach should be used whenever possible. Even when the classical retroperitoneal catheter drainage is not feasible, there should be an attempt to follow principles of step-up technique to buy time. The outcome of patients in the step-up group compared to the non step-up group is comparable in our series. Interventions for bowel diversion, bypass and hemorrhage control should be done at the appropriate times.

Keywords: Necrotizing pancreatitis, Nerosectomy, Morbidity and mortality in necrotizing pancreatitis, Step-up approach

Core tip: Necrotizing pancreatitis is a clinical challenge which requires aggressive conservative management in the early part of the attack. About 60% patients respond to conservative management. Patients who develop infection in the necrosis may require intervention. Delay, drain and debride if required, are the principles of step-up approach. Percutaneous drainage should be performed to be followed later by a step-up necrosectomy if required. If percutaneous drainage is not available or is technically unfeasible, surgical necrosectomy can yield equally good results when performed after an appropriate delay at least of 2 wk. With advent of minimally invasive modalities, infected as well as symptomatic sterile necrosis can be treated variably with radiological, surgical or endoscopic means. The modality selected depends upon the local morphology of the inflamed pancreas and availability of expertise.

INTRODUCTION

Necrotizing pancreatitis (NP) evolves in 15% to 25% of cases of acute pancreatitis[1-3]. It is a challenging clinical problem and despite great advances in the understanding of pathophysiology and management, the mortality rates in pancreatitis especially those with infected necrosis (IN) remain high[4-6]. Traditionally, open necrosectomy was the only tool available for surgical treatment of pancreatic necrosis. This was found to be associated with high mortality rates up to 40%[7]. With the understanding of the biphasic nature of the illness, the treatment of pancreatitis has undergone a paradigm change from early operative intervention to aggressive conservative management with avoidance of intervention as much as possible. The landmark paper by Besselink et al[8] in 2006 laid out the principles of “step up “approach to pancreatic necrosis. “Delay” the intervention, “drain” where possible by minimally invasive means and “debride” only when necessary became the pillars of management[9]. A multidisciplinary approach is now becoming the key to managing these patients[10]. These patients have long hospital stay and are a drain on the economic resources of the hospital as well as family. Morbidity can be extreme and happens in various forms.

On the background of the changes that have happened in the management of NP over the last decade we planned to review our prospective database to evaluate management of patients of NP. The aim was to determine percentage of patients in whom intervention was performed and the types of interventions they underwent. We attempted to identify the overall success rate of percutaneous catheter drainage (PCD) and to compare the outcomes of patients of step up necrosectomy to those of direct necrosectomy. Operative mortality, overall mortality, various forms of morbidity and treatment offered for the same, and overall length of stay was determined.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

After taking clearance from the institutional review board with a waiver of consent, a retrospective review of a prospective database of patients diagnosed to have acute pancreatitis admitted over a 7 years period between 2008 to 2014 was carried out. All patients having pancreatic necrosis were included in the study. Patients who had non-necrotizing acute pancreatitis, pancreatic pseudocysts, acute-on-chronic pancreatitis, those who took discharge against medical advice and in whom the data was incomplete, were excluded. We also excluded the patients who were referred late in the course of their illness from other hospitals after multiple interventions.

Epidemiological details regarding age, sex, etiology, interval between onset of attack and hospitalization, were noted. The APACHE II scores and the percentage of necrosis was noted. The severity of the episode was categorized as per the revised Atlanta guidelines into moderately severe or severe[11]. The computed tomography severity index (CTSI) was noted[12].

The management of patients was reviewed. Patients responding to conservative management with no further admissions were identified. In the rest, total interventions performed and indications for the interventions were noted. Intervention for abdominal compartment syndrome and endoscopic retrograde cholangiography with sphincterotomy and stenting if any was excluded. Interventions were categorized as those directed to pancreatic and perpancreatic necrosis and those performed for complications associated with necrosis or treatment. Timing of the primary intervention for the necrosis from the onset of illness was recorded. Patients undergoing necrosectomy were categorized into those with step-up necrosectomy and those with direct retroperitoneal or anterior necrosectomy. These two categories were compared for timing of intervention, mortality and hospital stay. Mortality in operated patients and the overall mortality was studied. Cause of death and timing of death in relation to onset of the attack was noted. The morbidity was recorded in terms of bowel fistulation, bowel obstruction and hemorrhage. The interventions required for the same were noted. Total duration of hospital stay was noted.

Treatment protocol

Intensive early management is instituted in all patients suspected to have severe acute pancreatitis. Adequate fluid resuscitation, oxygenation, electrolyte maintenance, pain relief are given. Great emphasis is placed on caloric support and early naso-jejunal feeding is instituted as soon as possible. In addition, chest physiotherapy and supplemental tapping of pleural fluid when necessary are used as measures to keep the oxygen saturation above 97%-98%. Ventilatory support is used whenever necessary.

Interventions for the pancreatic necrosis are avoided in the early period. Release of abdominal compartment is performed in the early phase when indicated, but there is no attempt to open the lesser sac at this stage. If patients respond to conservative management, no further intervention is planned. They are discharged once they are hemodynamically stable and enteral nutrition is established.

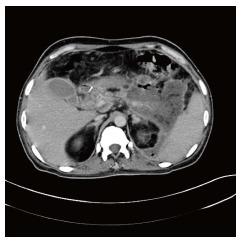

If there is suggestion of IN in the form of rising white cell count, febrile episodes not related to other sources (central venous catheters or pulmonary consolidation), tachycardia, tachypnea, sicker patient with weight loss, or evidence of gas in the area of necrosis on contrast enhanced computed tomography (CECT) scan (Figure 1), then intervention is planned based upon the principles of step-up approach. The approach to IN in order of preference is: (1) Image guided catheter through the flank directly into the retroperitoneum with step-up to retroperitoneal necrosectomy, if required; (2) direct retroperitoneal necrosectomy (video 1); (3) image guided catheter through anterior abdominal wall followed by focused anterior necrosectomy, if required (4) direct anterior laparotomy with necrosectomy and closed lavage of lesser sac. Open Abdomen approach is used in extreme cases. Irrespective of the approach, we try to enter the necrosis through minimal dissection. During necrosectomy, the loose necrotic tissue is removed and sharp dissection is avoided. The necrotic tissue sometimes is delivered as a cast (Figure 2) or piecemeal (Figure 3). The cavity is flushed with copious amount of warm saline which removes as much nonviable tissue as possible. This is followed by placement of an indigenously created irrigation system where a 12 Fr Ryle’s tube is inserted into a 32 Fr abdominal tube drain through a side cut near its outer end. The number of drains depends upon the space available. The necrotic cavity can be irrigated through the Ryles’ tube and the fluid is allowed to return through the tube drain. Because the drain is placed deep within the cavity, general peritoneal contamination is avoided even in anterior necrosectomy. Any overflow of fluid into the peritoneal cavity is removed by another drain placed in the pelvic cavity. Postoperatively, the intra-cavitary Ryles’ tube is used to lavage the cavity till all the solid necrotic elements are removed with further liquefaction. The lavage is performed either continuously or at intervals. The irrigation is discontinued when the drain stops showing pieces of solid debris or purulent fluid.

Figure 1.

Air in pancreatic necrosis.

Figure 2.

Cast of pancreatic necrosis.

Figure 3.

Piecemeal pancreatic necrosis.

When patients with presumed sterile walled off necrosis (WON) have symptoms like gastric outlet obstruction, failure to thrive or pain, depending upon the thickness of the wall of the necrotic sac, percutaneous drainage by catheters or trans-gastric debridement with cysto-gastrostomy for internal drainage is performed. In some cases, intervention is required due to obstruction of the bowel or suspected bowel fistulation. Bypass of the obstructed bowel and proximal diverting enterostomy is performed accordingly. Hemorrhage within the necrotic area is another indication for intervention. Trans-catheter embolization is used as the first choice of treatment for such cases.

RESULTS

During the 7 year period amongst all patients of acute pancreatitis (n = 276), 84 were identified as NP. Seven patients were excluded as per the exclusion criteria. The baseline characteristics of the patients included in the study (n = 77) are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Epidemiologic and Radiologic characteristics of patients n (%)

| Total patients | 77 |

| Age range | 15-65 |

| Average age | 35.65 |

| M:F | 6:01 |

| Etiology | |

| Alcohol | 55 (71.5) |

| Gall stones | 16 (20.8) |

| Ascariasis | 1 (1.2) |

| Idiopathic | 5 (6.5) |

| Severity | |

| Moderately severe | 59 (76.6) |

| Severe | 18 (23.4) |

| Extent of involvement | |

| > 90% | 27 (35.06) |

| 50%-90% | 38 (49.35) |

| 30%-50% | 9 (11.68) |

| Peripancreatic necrosis | 3 (3.89) |

| APACHE II score range | 8-19 |

| Average APACHE score | 12.4 |

| CTSI range | 6-10 |

| CTSI average | 8 |

CTSI: Computed tomography severity index. M: Male; F: Female.

Forty-seven patients (61%) responded to conservative management and required no further intervention during that admission or later.

A total of 41 interventions were carried out in 30 (39%) patients. The details of intervention are given in Table 2. Of these 41 interventions, 32 interventions targeted the pancreatic necrosis while 9 were required for dealing with the complications of the necrosis.

Table 2.

Details of interventions done in 30 patients

| Name of procedure | No. of patients |

| Percutaneous catheter drainage | 12 |

| Step-up retroperitoneal necrosectomy | 3 |

| Direct retroperitoneal necrosectomy | 3 |

| Direct anterior necrosectomy | 12 |

| Transgastric debridement with internal drainage (Cystogastrostomy) | 2 |

| Diverting stoma | 6 |

| Duodenojejunal bypass | 1 |

| Embolisation for bleeding pseudoaneurysms | 2 |

Indications for intervention were infection (n = 30), bowel obstruction (n = 1), bowel fistulization (n = 6), hemorrhage (n = 2), persistent organ failure (n = 1), pain, failure to thrive (n = 4). The interventions were chiefly surgical and radiological. Image guided PCD and embolization were the radiologic interventions.

PCD was performed in 9 patients for IN based upon the inclusion criteria. In all these patients a step-up necrosectomy was required. In 3 patients PCD was performed for indication other than infection where a 100% result was achieved and no other intervention was required. Thus the overall success rate for PCD was 25% (3/12).

Direct retroperitoneal necrosectomy (n = 3) or anterior necrosectomy (n = 12) was performed in 15 patients. Thus necrosectomy was required in 24 patients in all, 9 following PCD (step-up) and 15 without prior catheter drainage (Non step-up). All these were cases of IN. On comparing these two groups, the average time to first intervention was 19.6 d in the non step-up group (range 11-36) vs 18.22 d in the step-up group (range 13-25). The average hospital stay in non step-up group was 33.3 d vs 38 d in step up group.The difference between the two groups using the T-test was non significant for both these parameters. The mortality in the step-up group was 0% (0/9) vs 13% (2/15) in the non step up group. Using the fischer’s exact test, the difference was statistically not significant (P = 0.5). In all, 6 interventions were performed in first 2 wk compared to 18 in over 2 wk. Both the operative deaths occurred in patients undergoing direct necrosectomy within the first 2 wk though the difference was not statistically significant. In all patients after necrosectomy, closed lavage of the lesser sac was performed for an average duration of 16.5 d with a range of 12 to 32 d.

In 5 patients intervention was required for large persistent symptomatic WON without evidence of infection. Depending on the wall maturity they underwent either trans-gastric debridement and internal drainage of the necrosis in the form of cysto-gastrostomy (n = 2, 1 laparoscopic) or PCD (n = 3) (Figure 2) under image guidance. The average time for intervention in these patients was 60 d with a range of 42-90 d. These patients had an average post- intervention stay of 7.4 d.

Morbidity was seen in the form of bowel obstruction in 3 patients. In 2 cases, transient colonic obstruction occurred with air fluid levels on X-ray Abdomen. In both cases, it resolved with extended conservative management. One patient of duodenal obstruction required a duodenojenunostomy.

Bowel fistulation was apparent in 4 patients spontaneously and in 2 patients after a necrosectomy (one each from the retroperitoneal and anterior necrosectomy group). A proximal diversion was carried out in all these patients. The diverting stoma was closed in all patients 5-6 mo later without any further morbidity. Hemorrhage of visceral artery pseudoaneurysm occurred in 2 patients which was treated by radiologic embolization.

Overall mortality 10.38%. Five patients succumbed within first 4 d due to fulminant respiratory failure (n = 4) and sudden severe hemorrhage within pancreatic necrosis (n = 1). In the remaining 3 patients, the cause of death was new onset respiratory failure in the second week (n = 1) and sepsis with multi-organ failure (n = 2). The timing of death in these patients was 14th, 18th and 32nd day respectively. Excluding the early deaths, the mortality was 4.1%. Two out of these 3 patients were subjected to operative necrosectomy. Mortality in all patients undergoing necrosectomy (step-up or non step-up) was 2/24, i.e., 8.3%.

The average duration of stay was 22.25 d with a range of 7 to 110 d. The patients who responded to conservative management required an average 11.26 d of hospitalization. In the patients requiring intervention, the average hospital stay increased to 31.76 d.

DISCUSSION

Gallstones and alcohol are the commonest causes of pancreatitis worldwide, with gallstones having a larger role in the western population[13]. In Indian population alcohol is a more common etiological factor as seen in previous studies[14]. The revised Atlanta guideline of 2012 stratifies patients in three categories: Mild, moderately severe and severe depending upon the presence or absence of necrosis and transient or persistent organ failure. Moderately severe pancreatitis was proposed by Vege et al[15] who identified the large group of such patients in their patient population. We find similar distribution in our patients, with a nearly 77% of patients in the moderately severe category.

At the onset of the attack, it is difficult to determine the subgroup of patients likely to develop significant pancreatic necrosis. Since pancreatic necrosis increases mortality significantly, diagnosing it is imperative in management. CECT is the gold standard for diagnosing NP and is especially helpful if done after the 4th to 5th day of onset[13]. Studies have demonstrated that AP patients with a CTSI higher than 5 had 8 times higher mortality, 17 times more likelihood of a prolonged hospital course and were 10 times more likely to require necrosectomy than those with CTSI score < 5[16]. In our study group, more than 50% of pancreatic necrosis was seen in 38 patients and in additional 27 patients it was near total necrosis. This is also indicated by the high CTSI (average 8) in our patients. Clinically, this can lead to more local complications. Exclusively Peri-pancreatic necrosis was seen in 3 of our cases.

Due to better understanding of the initial systemic inflammatory response phase, the focus of initial management has shifted to an aggressive conservative one. Standard protocol for management should be established for all suspected cases of acute pancreatitis even before stratifying the patients. A significant number of patients respond to this management. In our series, 61% patients completely settled with conservative treatment and did not need any intervention either in the same admission or later. The role of intervention in NP is becoming more refined. With studies showing that early surgery is associated with higher mortality and that a large number of patients will respond to conservative management[1,17], the current recommendation is to delay the intervention to as late as possible.

Early intervention is required most often for IN. The mortality increases from 5%-25% in patients with sterile necrosis to 15%-28% when infection occurs[13]. Issues in managing IN are threefold. First issue is establishing the diagnosis of infection. A definite diagnosis requires Fine needle aspiration from the necrosis with gram staining. However with many studies showing recovery of some patients of IN with conservative management, the role of FNA is increasingly limited[18]. We have never used FNA to detect infection in the necrosis. Clinical signs can raise suspicion of infection and the CT scan may sometimes reveal air inside the necrotic area.

The second issue is the timing of intervention. IAP guidelines of 2002 recommended avoiding intervention till 14 d for better outcomes[19]. Subsequent studies have recommended further delaying this to the 28th or 29th day[20]. This is highly desirable as by this time the systemic inflammatory response subsides and patients are in a better condition to withstand interventions. The risk of iatrogenic injuries and hemorrhage becomes less as the necrosis is well separated from viable tissue[21]. The definition of delay varies between studies[19,22]. However, prolonging intervention beyond a certain time may entail overuse of antibiotics, increased incidence of resistant organisms as well as fungal superinfections[23,24]. In our patients, the average time to first intervention for IN whether radiological or surgical was 19.21 d, with the earliest intervention being the 12th day. Balancing this decision to intervene at the right time before the patient becomes too ill for any recovery is a clinical challenge. Though we have not found statistically significant difference between the mortality when intervention was performed below 2 wk and over 2 wk, it is still important to note that both the operative deaths occurred when procedure was performed in the first 2 wk.

The third issue in managing IN is the approach. IN till recently was considered as an indication for a traditional necrosectomy. However, this approach also has the reputation of being very morbid with a high mortality rate upto 40%[7]. Newer minimally invasive modalities have evolved over the last few years with an aim to reduce this morbidity and mortality. The step-up approach described by Santvoort et al[25], has changed the management of IN. Image guided PCD either through the retroperitoneal or transabdominal route now plays an important role as the first line drainage in IN. The success rate of PCD in IN varies and ranges from 0% to 78%[25,26]. In a meta-analysis, including 384 patients from 11 studies of PCD as a primary treatment for NP, surgical necrosectomy could be avoided in 56% of the patients and the overall mortality rate was 17%[27]. The incidence of IN in this group was 71%. Thus, PCD either causes sepsis reversal or allows complete recovery avoiding surgical intervention[23]. In 9 patients with clinically suspected IN we used PCD as the first line of management. In all these patients, a step-up necrosectomy was later required. So, our success rate for complete drainage was 0% in IN. However sepsis control was achieved and it allowed delay of surgery. The catheter tracts were used to perform focused necrosectomies. This allowed smaller incisions and prevented contamination of the general peritoneal cavity. The average time to insertion of PCD in the 9 patients with IN was 18.22 d.

Though it is desirable to use step-up approach in all patients of IN, it is sometimes not feasible to do so due to the morphology of the local area or lack of expertise. In such an event direct necrosectomy (retroperitoneal or anterior) may sometimes be necessary. We had to perform a direct necrosectomy in 15 patients. We prefer the retroperitoneal route to access the necrosis through the lienorenal ligament. The video assisted (VARD) or minimal access (MARPN) retroperitoneal necrosectomy is widely described mode for retroperitoneal necrosectomy. We have used the direct retroperitoneal access via a flank incision. This is possible when the inflammatory fluid tracks along the lienorenal ligament. This approach has the advantage of avoiding incisions on the abdominal wall thus reducing the chances of later wound dehiscence, hernia and pulmonary complications[28]. A retrospective analysis of 394 patients undergoing minimal access retroperitoneal necrosectomy compared with open necrosectomy showed MARPN to be superior in terms of postoperative complications and outcome[29]. Both MARPN and VARD have been shown at times to need open necrosectomy for better drainage. We have performed retroperitoneal necrosectomy in 3 patients as a step-up procedure and in 3 patients primarily and there was no further need for traditional necrosectomy in any of these patients. This approach should be used whenever feasible.

When the retroperitoneal route is not possible, anterior necrosectomy is performed. Historically traditional necrosectomy is associated with high morbidity and mortality rates. However, this needs to be reviewed in view of newer concepts of delaying intervention to at least 3rd week[27]. The average timing from onset to direct necrosectomy (both retroperitoneal and anterior) in our group of patients was 19.67 d.

Direct Endoscopic trans-gastric necrosectomy (DEN) is now performed across various centres to treat infected WON[30]. Using DEN, a stoma is created endoscopically between the enteric lumen and the necrotic collection, which allows for an endoscopic necrosectomy. There is no clarity in literature about the patients selected for this intervention. Current literature suggests that DEN is a less invasive and less risky alternative to open surgical necrosectomy for managing infected WON and infected pseudocyst with solid debris[31]. Two randomized trials have resulted in a high success rate at the beginning[32,33].

We have not used endoscopy as a modality in any of our cases. We are skeptical about transgressing the gastric lumen to enter into an area of IN with inadequate demarcation and increased vascularity. There are other limitations of endoscopic procedure as well, namely inadequate drainage and closure of the communication.

Our results with direct necrosectomy with postoperative lavage have been very good. We have performed anterior necrosectomy in 12 patients with no prior PCD with a mortality of 16.66%. The overall mortality in all patients undergoing necrosectomy with or without prior catheter drainage is 8.3%. This shows that inspite of newer minimal invasive modalities, there is still a role for traditional surgical intervention as also voiced by Gou et al[34].

The best sub-group of patients is those who respond to conservative management and then follow-up later after a period of 2-3 mo with a persistent symptomatic WON. In this group, a trans-gastric necrosectomy with internal drainage by cysto-gastrostomy offers a perfect single step cure if the wall is mature. This internal drainage can be performed by standard open technique, laparoscopically or by endoscopic route depending upon the local expertise available[35,36]. The results from any of these modalities are comparable[36]. We had the opportunity to perform this procedure for WON only in 2 of our 77 patients. In one of them, it was performed laparoscopically. In the same subset, when the wall of WON is not mature and the content is more fluid, PCD can effectively drain most of the necrotic fluid. In three of our patients, we used this approach. Whether such cases with intermediate characteristics can be treated with endoscopic cysto-gastrostomy is question which may need randomized controlled trials to establish the answers[1]. In sterile necrosis, the mortality has been shown to be time dependent after intervention and nearing 0% by the stage of sterile WON[35].

The mortality of NP has a bimodal pattern[37]. Early deaths (within the first week) occur due to severe systemic inflammatory response leading to organ failure. In our series there were 4 early deaths related to uncontrolled respiratory failure. One death occurred due to sudden severe hemorrhage in the pancreatic necrosis on day 6 of admission. Late mortality (occurs after 2 to 3 wk) is secondary to sepsis related organ failure. Three of our patients succumbed to multi-organ failure secondary to sepsis late in the course of illness.

In one patient there was a new onset respiratory failure on day 12 which led to death. This new onset organ failure led us to intervene in this patient with a traditional necrosectomy, which was probably avoidable. All the patients who died were severe pancreatitis. The overall mortality rate is 10.38% in our patient group. Patients of NP have high morbidity. This exists in terms of bowel obstruction, fistulation, hemorrhage, extended hospitalization. Colonic complications associated with pancreatitis occur infrequently (< 1% of cases). These can vary from reactive ileus to severe obstruction, necrosis or perforation[10]. Two of our patients had colonic obstruction with air fluid levels and both these patients responded to conservative management. Duodenal obstruction was encountered in one patient which persisted even after necrosectomy and required duodeno-jejunal bypass.

Bowel fistulation was seen in 6 patients requiring diversion stoma. Fistulation into the bowel can happen spontaneously due to severe inflammation or can be iatrogenic after extensive debridement. It is imperative that the necrosectomy is done with utmost care to prevent iatrogenic injury to bowel. Sharp dissection should be avoided and only loose nonviable tissue should be removed. Hydro-dissection is a good way to improve scope of necrosectomy compared to sharp dissection. High index of suspicion is required for the possibility of bowel fistulation. Early decision for proximal diversion helps reduce the morbidity.

Gastroduodenal or pancreaticoduodenal artery pseudo-aneurysms occur after significant inflammation of the pancreas and can lead to hemorrhage, which has been reported in 2.4% to 10% of cases[38]. Embolization is the treatment of choice. This was seen in two patients and radiologic embolization was successful in both. Patients of NP pose a significant financial burden on the healthcare systems. Multiple interventions may be required and this increases the hospital stay significantly.

In management of NP, early conservative management plays an important role. Having a standard management protocol is essential. In about 60% cases, conservative management is successful. In the rest, multidisciplinary management is required for the best outcome. Approach used, timing of intervention is based upon the clinical condition and local expertise available. Delayed intervention using minimally invasive techniques is desirable. The step-up approach should be used whenever possible. Using image guided PCD to reduce the sepsis followed by necrosectomy is desirable. The outcome of step up approach and direct surgical approach is comparable if intervention is delayed. Interventions for bowel diversion, bypass and hemorrhage control should be done at the appropriate times. An overall mortality of 10.38% is achieved by following all the above principles which is a very low figure. Good outcome of the patient is the primary objective.

COMMENTS

Background

Necrotizing pancreatitis is a challenging clinical condition. At present, avoiding surgical intervention whenever possible and using various minimally invasive modalities if intervention is absolutely necessary are the chief practice guidelines. Different centres have their own protocol for treating these patients and the modality that a particular centre will follow depends upon the expertise available. The outcome of the patient is most important. It is essential to have published data from various centres in order to know the different modalities followed.

Research frontiers

Currently, minimal invasive retroperitoneal necrosectomy and endoscopic approach to pancreatic necrosis are being researched widely. Also, the subgroup of patients with infected necrosis who can be treated without intervention is also an area of research. There are papers evaluating outcomes with operative necrosectomy and comparing them with minimal invasive necrosectomy.

Innovations and breakthroughs

Most of the techniques are standard techniques described in literature. One essential modification the development of an indigenous sump drain system whereby small ryles’ tube is inserted into the larger drain which is then used as a continuous irrigation system. Also, the focused abdominal necrosectomy, which uses the previously placed pigtail catheter is used to enter the area of necrosis is an important advance to keep the procedure less invasive.

Applications

Every patient of pancreatitis needs to be approached with a tailored management. Initial conservative management should be standardized. Whenever intervention is required, one should apply the various minimally invasive modalities whenever feasible. Operative necrosectomy should not be withheld in case such expertise is not available. Principles of appropriate delay should be followed strictly. If local conditions are not conducive for minimal invasive procedures, in such cases also operative necrosectomy may be offered. Comparative studies between minimal invasive necrosectomy and operative necrosectomy may be planned as multicenter studies.

Terminology

All terms used in the paper are standard terms well known to physicians dealing in patients of acute pancreatitis.

Peer-review

This manuscript shows the valuable experience of a tertiary referral center on severe acute pancreatitis.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We wish to thank Dr. Supe AN, Director (ME and MH) and Dean, Seth G.S.Medical College and KEM Hospital, Parel, Mumbai-12, for allowing us to publish hospital data.

Footnotes

Institutional review board statement: This was a retrospective review of existing database of patients hence a waiver from Institutional review board was requested for and was granted. Statement of the same is uploaded.

Informed consent statement: No informed consent document is available as this is a retrospective review of database. Care has been taken not to disclose identity of any patient.

Conflict-of-interest statement: None.

Data sharing statement: As this is a retrospective analysis of an existing database, there is no data sharing statement.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: India

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

Peer-review started: December 28, 2016

First decision: January 14, 2017

Article in press: August 17, 2017

P- Reviewer: Gonzalez NB, Manenti A, Neri V S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

Contributor Information

Deshpande Aparna, Department of Surgery, Seth G.S.Medical College and K.E.M. Hospital, Parel, Mumbai 400012, India. aparnadeshpande@kem.edu.

Sunil Kumar, Department of Surgery, Seth G.S.Medical College and K.E.M. Hospital, Parel, Mumbai 400012, India.

Shukla Kamalkumar, Department of Surgery, Seth G.S.Medical College and K.E.M. Hospital, Parel, Mumbai 400012, India.

References

- 1.Karakayali FY. Surgical and interventional management of complications caused by acute pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:13412–13423. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i37.13412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lowenfels AB, Maisonneuve P, Sullivan T. The changing character of acute pancreatitis: epidemiology, etiology, and prognosis. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2009;11:97–103. doi: 10.1007/s11894-009-0016-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Freeman ML, Werner J, van Santvoort HC, Baron TH, Besselink MG, Windsor JA, Horvath KD, vanSonnenberg E, Bollen TL, Vege SS; International Multidisciplinary Panel of Speakers and Moderators. Interventions for necrotizing pancreatitis: summary of a multidisciplinary consensus conference. Pancreas. 2012;41:1176–1194. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e318269c660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maheshwari R, Subramanian RM. Severe Acute Pancreatitis and Necrotizing Pancreatitis. Crit Care Clin. 2016;32:279–290. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2015.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haney JC, Pappas TN. Necrotizing pancreatitis: diagnosis and management. Surg Clin North Am. 2007;87:1431–1446, ix. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2007.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frossard JL, Steer ML, Pastor CM. Acute pancreatitis. Lancet. 2008;371:143–152. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60107-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bugiantella W, Rondelli F, Boni M, Stella P, Polistena A, Sanguinetti A, Avenia N. Necrotizing pancreatitis: A review of the interventions. Int J Surg. 2016;28 Suppl 1:S163–S171. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2015.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Besselink MG, van Santvoort HC, Nieuwenhuijs VB, Boermeester MA, Bollen TL, Buskens E, Dejong CH, van Eijck CH, van Goor H, Hofker SS, et al. Minimally invasive ‘step-up approach’ versus maximal necrosectomy in patients with acute necrotising pancreatitis (PANTER trial): design and rationale of a randomised controlled multicenter trial [ISRCTN13975868] BMC Surg. 2006;6:6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2482-6-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kokosis G, Perez A, Pappas TN. Surgical management of necrotizing pancreatitis: an overview. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:16106–16112. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i43.16106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aranda-Narváez JM, González-Sánchez AJ, Montiel-Casado MC, Titos-García A, Santoyo-Santoyo J. Acute necrotizing pancreatitis: Surgical indications and technical procedures. World J Clin Cases. 2014;2:840–845. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v2.i12.840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Banks PA, Bollen TL, Dervenis C, Gooszen HG, Johnson CD, Sarr MG, Tsiotos GG, Vege SS; Acute Pancreatitis Classification Working Group. Classification of acute pancreatitis--2012: revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut. 2013;62:102–111. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Balthazar EJ, Robinson DL, Megibow AJ, Ranson JH. Acute pancreatitis: value of CT in establishing prognosis. Radiology. 1990;174:331–336. doi: 10.1148/radiology.174.2.2296641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tonsi AF, Bacchion M, Crippa S, Malleo G, Bassi C. Acute pancreatitis at the beginning of the 21st century: the state of the art. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:2945–2959. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.2945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barreto SG, Rodrigues J. Acute pancreatitis in Goa--a hospital-based study. J Indian Med Assoc. 2008;106:575–576, 578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vege SS, Gardner TB, Chari ST, Munukuti P, Pearson RK, Clain JE, Petersen BT, Baron TH, Farnell MB, Sarr MG. Low mortality and high morbidity in severe acute pancreatitis without organ failure: a case for revising the Atlanta classification to include “moderately severe acute pancreatitis”. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:710–715. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2008.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Werner J, Uhl W, Hartwig W, Hackert T, Müller C, Strobel O, Büchler MW. Modern phase-specific management of acute pancreatitis. Dig Dis. 2003;21:38–45. doi: 10.1159/000071338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Amano H, Takada T, Isaji S, Takeyama Y, Hirata K, Yoshida M, Mayumi T, Yamanouchi E, Gabata T, Kadoya M, et al. Therapeutic intervention and surgery of acute pancreatitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2010;17:53–59. doi: 10.1007/s00534-009-0211-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.da Costa DW, Boerma D, van Santvoort HC, Horvath KD, Werner J, Carter CR, Bollen TL, Gooszen HG, Besselink MG, Bakker OJ. Staged multidisciplinary step-up management for necrotizing pancreatitis. Br J Surg. 2014;101:e65–e79. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Uhl W, Warshaw A, Imrie C, Bassi C, McKay CJ, Lankisch PG, Carter R, Di Magno E, Banks PA, Whitcomb DC, et al. IAP Guidelines for the Surgical Management of Acute Pancreatitis. Pancreatology. 2002;2:565–573. doi: 10.1159/000071269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Besselink MG, van Santvoort HC, Boermeester MA, Nieuwenhuijs VB, van Goor H, Dejong CH, Schaapherder AF, Gooszen HG; Dutch Acute Pancreatitis Study Group. Timing and impact of infections in acute pancreatitis. Br J Surg. 2009;96:267–273. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bello B, Matthews JB. Minimally invasive treatment of pancreatic necrosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:6829–6835. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i46.6829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hungness ES, Robb BW, Seeskin C, Hasselgren PO, Luchette FA. Early debridement for necrotizing pancreatitis: is it worthwhile? J Am Coll Surg. 2002;194:740–744; discussion 744-745. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(02)01182-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De Waele JJ, Blot SI, Vogelaers D, Colardyn F. High infection rates in patients with severe acute necrotizing pancreatitis. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30:1248. doi: 10.1007/s00134-004-2232-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.De Waele JJ, Vogelaers D, Blot S, Colardyn F. Fungal infections in patients with severe acute pancreatitis and the use of prophylactic therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:208–213. doi: 10.1086/375603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Santvoort HC, Besselink MG, Bakker OJ, Hofker HS, Boermeester MA, Dejong CH, van Goor H, Schaapherder AF, van Eijck CH, Bollen TL, et al. A step-up approach or open necrosectomy for necrotizing pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1491–1502. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee JK, Kwak KK, Park JK, Yoon WJ, Lee SH, Ryu JK, Kim YT, Yoon YB. The efficacy of nonsurgical treatment of infected pancreatic necrosis. Pancreas. 2007;34:399–404. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e318043c0b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Baal MC, van Santvoort HC, Bollen TL, Bakker OJ, Besselink MG, Gooszen HG; Dutch Pancreatitis Study Group. Systematic review of percutaneous catheter drainage as primary treatment for necrotizing pancreatitis. Br J Surg. 2011;98:18–27. doi: 10.1002/bjs.7304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Babu RY, Gupta R, Kang M, Bhasin DK, Rana SS, Singh R. Predictors of surgery in patients with severe acute pancreatitis managed by the step-up approach. Ann Surg. 2013;257:737–750. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318269d25d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gomatos IP, Halloran CM, Ghaneh P, Raraty MG, Polydoros F, Evans JC, Smart HL, Yagati-Satchidanand R, Garry JM, Whelan PA, et al. Outcomes From Minimal Access Retroperitoneal and Open Pancreatic Necrosectomy in 394 Patients With Necrotizing Pancreatitis. Ann Surg. 2016;263:992–1001. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seewald S, Groth S, Omar S, Imazu H, Seitz U, de Weerth A, Soetikno R, Zhong Y, Sriram PV, Ponnudurai R, et al. Aggressive endoscopic therapy for pancreatic necrosis and pancreatic abscess: a new safe and effective treatment algorithm (videos) Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:92–100. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(05)00541-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ang TL, Kwek AB, Tan SS, Ibrahim S, Fock KM, Teo EK. Direct endoscopic necrosectomy: a minimally invasive endoscopic technique for the treatment of infected walled-off pancreatic necrosis and infected pseudocysts with solid debris. Singapore Med J. 2013;54:206–211. doi: 10.11622/smedj.2013074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seifert H, Biermer M, Schmitt W, Jürgensen C, Will U, Gerlach R, Kreitmair C, Meining A, Wehrmann T, Rösch T. Transluminal endoscopic necrosectomy after acute pancreatitis: a multicentre study with long-term follow-up (the GEPARD Study) Gut. 2009;58:1260–1266. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.163733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gardner TB, Coelho-Prabhu N, Gordon SR, Gelrud A, Maple JT, Papachristou GI, Freeman ML, Topazian MD, Attam R, Mackenzie TA, et al. Direct endoscopic necrosectomy for the treatment of walled-off pancreatic necrosis: results from a multicenter U.S. series. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:718–726. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.10.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gou S, Xiong J, Wu H, Zhou F, Tao J, Liu T, Wang C. Five-year cohort study of open pancreatic necrosectomy for necotizing pancreatitis suggests it is a safe and effective operation. J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;17:1634–1642. doi: 10.1007/s11605-013-2288-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gibson SC, Robertson BF, Dickson EJ, McKay CJ, Carter CR. ‘Step-port’ laparoscopic cystgastrostomy for the management of organized solid predominant post-acute fluid collections after severe acute pancreatitis. HPB (Oxford) 2014;16:170–176. doi: 10.1111/hpb.12099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khreiss M, Zenati M, Clifford A, Lee KK, Hogg ME, Slivka A, Chennat J, Gelrud A, Zeh HJ, Papachristou GI, et al. Cyst Gastrostomy and Necrosectomy for the Management of Sterile Walled-Off Pancreatic Necrosis: a Comparison of Minimally Invasive Surgical and Endoscopic Outcomes at a High-Volume Pancreatic Center. J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;19:1441–1448. doi: 10.1007/s11605-015-2864-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fu CY, Yeh CN, Hsu JT, Jan YY, Hwang TL. Timing of mortality in severe acute pancreatitis: experience from 643 patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:1966–1969. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i13.1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martin RF, Hein AR. Operative management of acute pancreatitis. Surg Clin North Am. 2013;93:595–610. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2013.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]