Abstract

Population genetic approaches have uncovered a strong association between kidney diseases and two sequence variants of the APOL1 gene, called APOL1 risk variant G1 and variant G2, compared with the nonrisk G0 allele. However, the mechanism whereby these variants lead to disease manifestation and, in particular, whether this involves an intracellular or extracellular pool of APOL1 remains unclear. Herein, we show a predominantly intracellular localization of APOL1 G0 and the renal risk variants, which localized to membranes of the endoplasmic reticulum in podocyte cell lines. This localization did not depend on the N-terminal signal peptide that mediates APOL1 secretion into the circulation. Additionally, a fraction of these proteins localized to structures surrounding mitochondria. In vitro overexpression of G1 or G2 lacking the signal peptide inhibited cell viability, triggered phosphorylation of stress-induced kinases, increased the phosphorylation of AMP-activated protein kinase, reduced intracellular potassium levels, and reduced mitochondrial respiration rates. These findings indicate that functions at intracellular membranes, specifically those of the endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria, are crucial factors in APOL1 renal risk variant–mediated cell injury.

Keywords: APOL1, renal risk variant, podocyte, endoplasmic reticulum, mitochondria, energy depletion

The strong associations of kidney disease with common DNA sequence variants in the human Apolipoprotein L1 gene (APOL1) were first reported in two independent studies in 2010.1,2 These two APOL1 risk variants—designated G1 and G2 (in contrast to the ancestral nonrisk allele, termed G0)—have risen to very high allele frequency in populations of Sub-Saharan African ancestry. This occurred in response to past evolutionary pressure related to extended protection from pathogens including a subtype of Trypanosoma brucei.1–4 Whereas even a single parentally inherited APOL1 G1 or G2 allele variant confers protection from these pathogens, two copies are associated with a very markedly elevated risk for a wide spectrum of glomerular diseases, such as hypertension-attributed kidney disease (hypertension with nephrosclerosis),1,5 primary nonmonogenic FSGS,6 or HIV-associated nephropathy.6,7 Moreover, renal risk variants (RRVs) were associated with the progression of lupus nephritis,8,9 associated with collapsing glomerulopathy in patients with SLE7 and patients with membranous nephropathy.10 The odds ratios range from approximately 7 to >80 and depend on underlying kidney disease etiology. Notwithstanding this impressive association and the compelling but circumstantial evidence for causality,11 there is still a gap of knowledge about how the APOL1 protein contributes to kidney diseases at the cellular level. Data from previous studies suggest the involvement of APOL1 in apoptosis, autophagy-associated cell death,12–16 endo-lysosomal disturbances,17–19 mitochondrial dysfunction,20 and increased potassium (K+) efflux at the plasma membrane (PM) coupled to an activation of stress-activated protein kinases.21

Interestingly, APOL1 is the most recently evolved member of the six-strong protein family—APOL1–APOL6—exhibiting similar domain architecture. APOL1 contains a pore-forming domain (PFD), a membrane-addressing domain (MAD), and the C-terminal SRA protein–binding domain (SRA-BD), which contains the RRV mutations G1 (S342G/I384M) and G2 (Δ388N389Y). The PFDs of APOL protein family members share some structural features with α-helical pore-forming bacterial toxins (e.g., Colicin A) and contain a Bcl-2 homology 3 (BH3) domain–like sequence motif. The MAD is assumed to mediate membrane targeting together with the PFD.4,22 The physiologic functions of the SRA-BD are unclear.1,23

APOL1 contains a putative N-terminal signal peptide (SP), which mediates its secretion into human serum where it circulates in two multiprotein trypanolytic factor complexes (TLF1 and TLF224–26) and provides protection during parasite infection via mechanisms that have been comprehensively investigated.23

Whereas the mechanisms of APOL1 trypanolytic activity have been studied extensively,3,27,28 less is known about the mechanisms of APOL1-mediated cell injury, in particular of APOL1 risk variants. Remarkably, all APOL protein family members, except APOL1, lack an SP and are not secreted, suggesting that common and evolutionarily conserved functions of APOL proteins are most probably linked to intracellular localization.22 Moreover, even among the different documented splice-variants of APOL1 some lack an SP, indicating the existence of at least two APOL1 pools in the cell: one in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) lumen which is released into the circulation via the secretory pathway and a nonsecreted intracellular pool.29

In this study, we focus on the intracellular nonsecreted APOL1 pool and show a prominent pool of APOL1 localized to the ER along with partial colocalization with mitochondrial membranes, independent of the SP. Moreover, we could not detect APOL1 at the PM. Although lacking the SP, expression of APOL1 G1 and G2 resulted in a strong cytotoxicity, activation of stress kinases, accumulation of autophagy markers, and was accompanied by reduced intracellular ATP levels and mitochondrial respiration rates. Hence, our results indicate an important role for APOL1 RRVs in energy depletion during APOL1-associated cell injury.

Results

Intracellular APOL1 Is Predominantly Targeted to the ER

APOL1-associated kidney disease requires both risk allele genotypes and a second nongenetic trigger.30 The latter include triggers which act through immune modulatory signals (e.g., IFN-γ) that markedly increase APOL1 expression.17,31 Because kidney transplantation studies strongly point to an intrarenal rather than systemic pool of APOL1 in kidney disease association, we consider that cell injury is not mediated by APOL1 following the classic secretory pathway.31–36 This formulation has received further confirmation by recently reported findings in whole-organism model systems.16,37

So far, there is limited data about the intracellular distribution of APOL1 in living cells.38,39 Hence, we addressed this aspect in more detail by immunofluorescence (IF) analysis of AB8 podocyte cell lines expressing untagged full-length APOL1 or its RRVs. We found a strong colocalization of all three APOL1 variants with the ER resident protein Calnexin (Supplemental Figure 1). No or very low colocalization was detected with markers of early (EEA1) and late (Lamp2a) endosomes or the proteasome and autophagosome marker p62 (Supplemental Figure 2). To visualize ER structures in IF and live cell imaging experiments, we used the mCherry-tagged ER resident protein Sec61β (mCh-Sec61β).40 Indeed, transient transfection of AB8 cells expressing untagged APOL1 or C-terminal EGFP-tagged APOL1 with mCh-Sec61β confirmed the predominant localization of all APOL1 variants at the ER (Supplemental Figure 3, A and B).

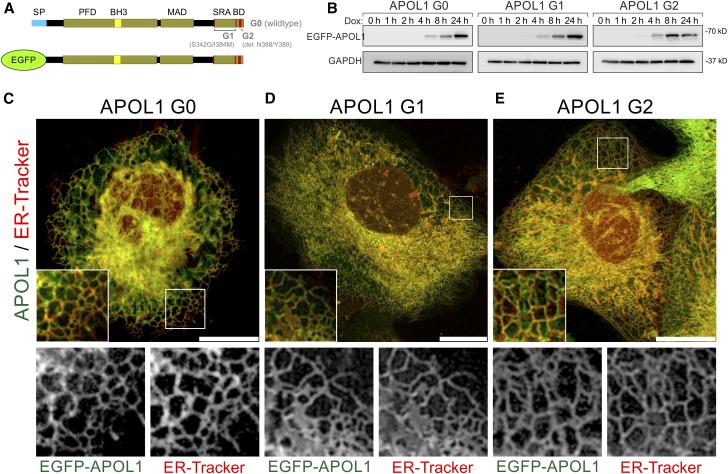

Next, we investigated the role of the putative SP (aa 1–27) for the intracellular APOL1 distribution. For that purpose, we replaced the SP by EGFP and established stable doxycycline inducible cell lines expressing EGFP-APOL1 G0, and RRVs G1 and G2 (Figure 1A). These cell lines showed similar expression levels and did not alter endogenous APOL1 expression (Figure 1, Supplemental Figure 4). Live cell imaging of EGFP-APOL1 expressing cell lines (Supplemental Material) costained with ER-Tracker (Figure 1, C–E) or transiently transfected with mCherry-Sec61β (Supplemental Figure 5) revealed again a strong colocalization of APOL1 with ER markers, indicating that APOL1 ER localization is independent of an SP.

Figure 1.

EGFP-tagged APOL1 lacking the SP is targeted to the ER in podocytes. (A) Scheme of EGFP APOL1 fusion proteins used, in which the endogenous N-terminal SP (blue) was replaced by EGFP (green). All variants include the PFD and MAD. APOL1 RRV–associated G1 point (S342G/I384M) and G2 deletion (Δ388N389Y) mutants are localized in the C-terminal SRA-BD. (B) Western blot analyses demonstrated that expression of APOL1 G0 and RRVs G1 and G2 starts 4 hours after adding doxycycline to the cell culture medium. Expression reached a maximum after 24 hours. (C–E) Live cell image analyses of EGFP-tagged APOL1 (green, Dox induction 24 hours) in combination with ER-Tracker (red) revealed a predominant localization of APOL1 to tubular-like and perinuclear localized membrane structures (C–E, details) of the ER. Noncytotoxic EGFP-APOL1 G0 and RRVs APOL1 G1 (D) and G2 (E) showed a similar intracellular distribution. Scale bar and square length of details are 20 and 10 µm, respectively.

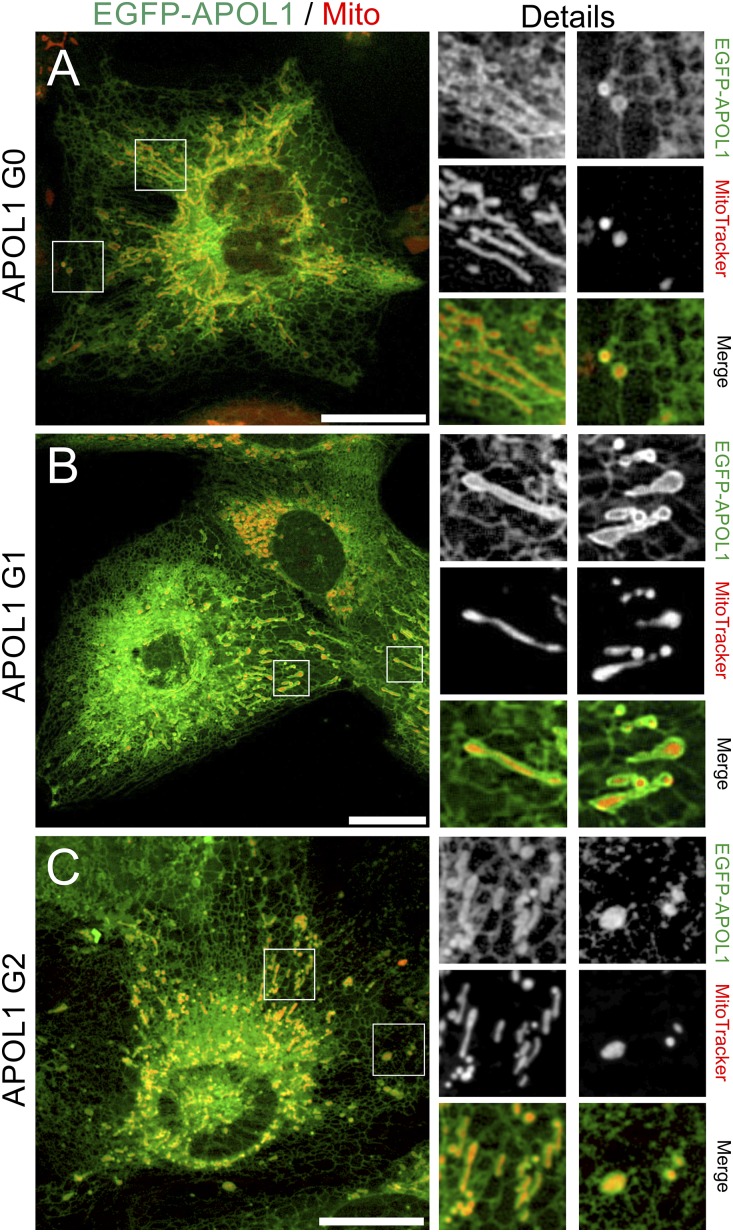

Costaining of EGFP-APOL1–expressing cells with MitoTracker also revealed structures that surround mitochondria (Figure 2, A–C), suggesting that a fraction of intracellular APOL1 is targeted to mitochondrial membranes or to ER-mitochondrial contact sites. However, we observed no or partial colocalization of EGFP-APOL1 with early and late endosomes (Supplemental Figure 6), autophagic structures (Supplemental Figure 7), or membranes of the Golgi apparatus (Supplemental Figure 7). We were unable to detect APOL1 at the PM (Supplemental Figure 8).

Figure 2.

APOL1 partially colocalizes with mitochondrial membranes in podocytes. (A–C) Live cell image analyses of EGFP-tagged APOL1 (green, Dox induction 24 hours) in combination with MitoTracker (red) revealed EGFP-APOL1–positive structures colocalize with mitochondria. Again, all EGFP-APOL1 variants, G0 (A), and RRVs G1 (B) and G2 (C), showed a similar intracellular distribution. Scale bar and square length of details are 20 and 10 µm, respectively.

When expressed in CV-1 cells (renal cell line from African green monkey Cercopithecus aethiops), which endogenously lack APOL1,22 all APOL1 variants localized to ER (data not shown) or MitoTracker-positive tubule-like and perinuclear structures, which partially encircled mitochondria (Supplemental Figure 9). The conserved intracellular localization of APOL1 variants (G0 and RRVs), even in cells of nonhuman origin, indicate that cytotoxic effects (see below) of RRVs are linked to altered functions at these membranes.

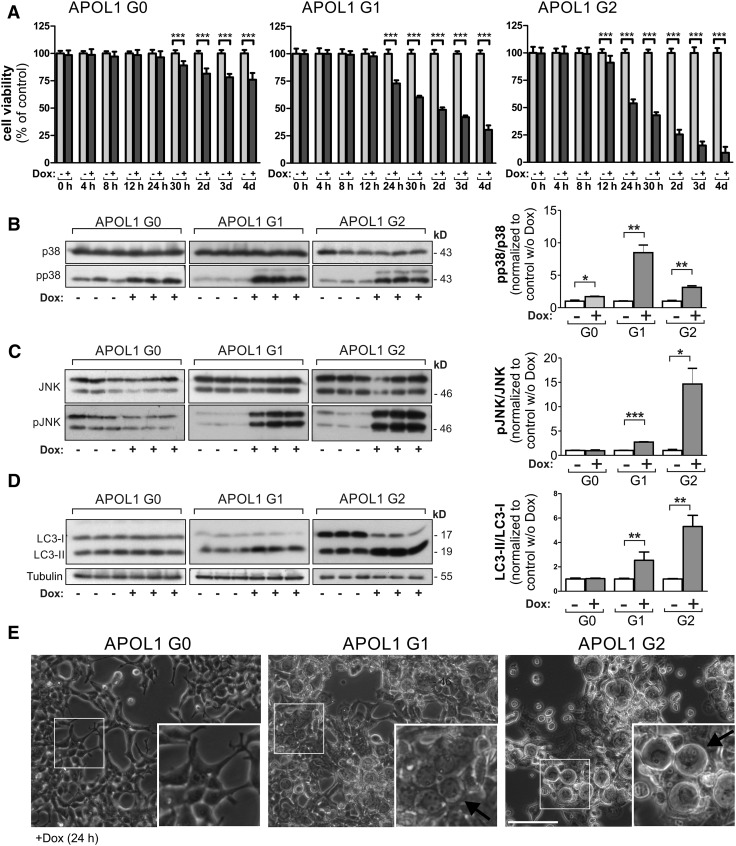

APOL1 RRVs Lacking the SP Cause Reduced Cell Viability and Activate Cellular Stress Pathways

Next, we analyzed if expression of EGFP-APOL1 G1 and G2 is linked to decreased viability as was previously shown for full-length APOL1 (variant A).12–14,17,18,21,41 Indeed, induced expression of EGFP-tagged APOL1 RRVs resulted in reduced cell viability, or increased cytotoxicity, which was strongest for the APOL1 G2 variant in HEK293T (Figure 3A, Supplemental Figure 10). The reduced cell viability caused by APOL1 RRVs was accompanied by an activation of stress kinases JNK/SAPK and p38 MAPK (Figure 3, B and C). We also observed increased levels of the autophagy marker LC3-II, as well as increased cell swelling (Figure 3D, Supplemental Figure 11).

Figure 3.

APOL1 RRVs lacking the SP cause reduced cell viability in HEK293T cells. (A) Cytotoxicity analyses with stable HEK293T cell lines, allowing a doxycycline-dependent overexpression of EGFP-APOL1 G0 and RRVs revealed that APOL1 RRVs, lacking the SP, were still able to cause a significant reduction of the cell viability in HEK293T cells. In HEK293T cells, decreased cell viability was even detectable in G0-overexpressing cells but the effect was much stronger for APOL1 RRVs G1 and G2 overexpressing cells. (B–D) Western blot analysis (left) and quantifications (right). Lysates from EGFP-APOL1–overexpressing HEK293T (Dox induction 24 hours) cells elucidated a significantly elevated phosphorylation of stress kinases pJNK/pSAPK (B), p-p38 (C), and an accumulation of the autophagy marker protein LC3-II (increased LC3-II/LC3-I ratio) in cells overexpressing RRVs (D). (E) Transmitted light bright-field images of HEK293T cells overexpressing RRVs (Dox induction 24 hours) showed an increased number of cells with swollen morphology. Data are shown as mean±SEM of at least three independent experiments; *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.005. w/o, without.

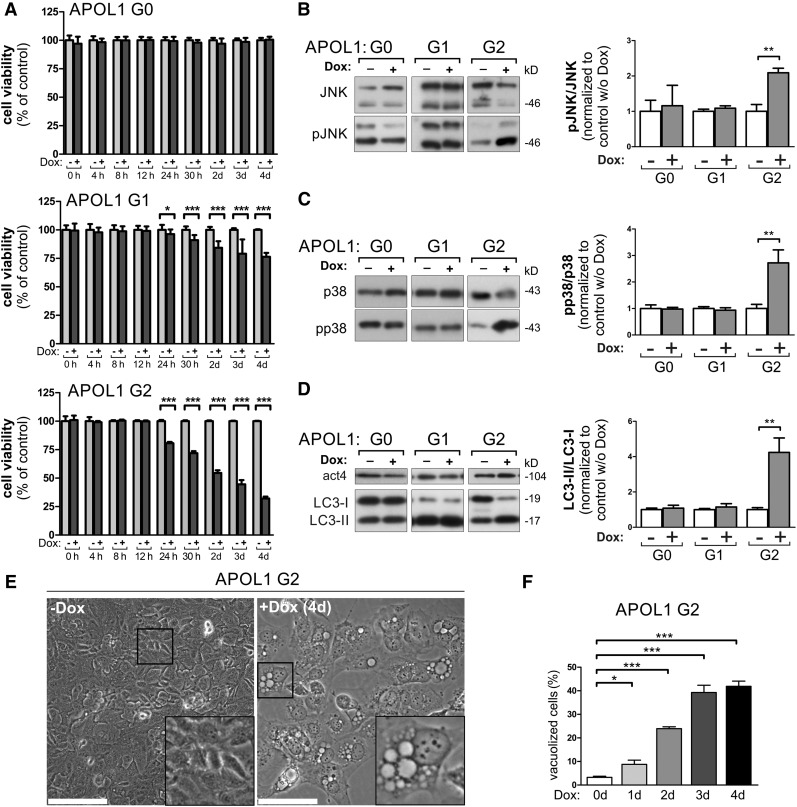

We found that AB8 podocytes were more resistant to APOL1 RRV–linked cytotoxicity, because APOL1 G0 showed no and G1 only minor effects after 24 hours in the cell viability assays, whereas the strongest cytotoxicity was observed in APOL1 G2 cells (Figure 4A, Supplemental Figure 10B). Similar to HEK293T cells, reduced cell viability was accompanied by activation of JNK/SAPK and p38 (Figure 4, B and C), an increased LC3-II/LC3-I ratio (Figure 4D), and the formation of intracellular vacuoles (Figure 4, E and F).

Figure 4.

APOL1 RRVs lacking the SP cause reduced cell viability in podocytes. (A) Cytotoxicity analyses with stable podocyte cell lines, enabling the doxycycline-dependent overexpression of EGFP-APOL1 G0 and RRVs, revealed that APOL1 RRVs were able to cause a significant reduction of the cell viability. Podocytes were less susceptible to an APOL1-linked reduced viability than HEK293T cells (see Figure 3A), because the effect is not detectable in G0-overexpressing cells. Thus, AB8 podocytes were more resistant against APOL1-linked cytotoxic effects. In all experiments, the effect was stronger in APOL1 G2–overexpressing cells. (B–D) Western blot analysis (left) and quantifications (right). Lysates from EGFP-APOL1–overexpressing podocyte (Dox induction 24 hours) cells elucidated an elevated phosphorylation of stress kinases pJNK/pSAPK (B), and p-p38 (C), and an accumulation of the autophagy marker protein LC3-II (increased LC3-II/LC3-I ratio) (D) in cells overexpressing APOL1 G2. (E) Transmitted light bright-field images of podocytes expressing APOL1 G2 for 4 days show a strong vacuolization phenotype. Scale bars represent 100 µm. (F) Quantification over 4 days of doxycycline induction indicates progressive cellular vacuolization induced by APOL1 G2 in podocytes. Data are shown as mean±SEM of at least three independent experiments; *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.005. w/o, without.

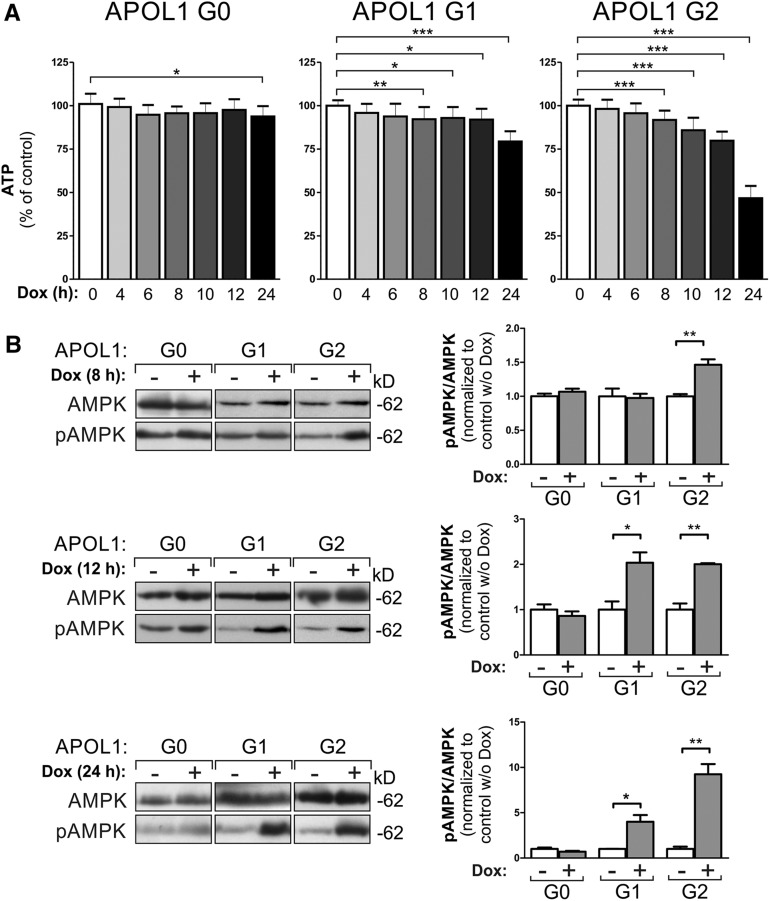

APOL1 Risk Variants Result in ATP Depletion

Activation of stress pathways and autophagic processes can be a consequence of intracellular ATP depletion.42 To address this, we used a luciferase assay in which the enzymatic activity only depends on the intracellular ATP concentration. These experiments revealed reduced ATP concentrations in APOL1 RRV–expressing cells 8 hours after induction. Earlier time points showed a trend in this direction but did not reach significance (Figure 5A). Next, we analyzed the expression and phosphorylation levels of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK). AMPK phosphorylation is increased if the intracellular ATP/AMP ratio drops.43,44 Indeed, Figure 5B demonstrates significantly increased pAMPK levels only in EGFP-APOL1 G1 and G2 (here already after 8 hours)–expressing HEK293T cells. In podocytes, this effect is only detectable in APOL1 G2–overexpressing cells (Supplemental Figure 12).

Figure 5.

APOL1 risk variant expression results in ATP depletion and activation of the AMPK. (A) HEK293T cells overexpressing APOL1 RRVs showed decreased intracellular ATP levels in a luciferase assay in which the enzymatic activity depends only on the intracellular ATP concentration. Data are shown as mean±SD, n≥3. (B) RRV-expressing HEK293T cells furthermore showed significantly increased pAMPK levels (pAMPK/AMPK ratio) already, after 8 hours of Dox induction for variant G2 and after 12 for variant G1. Data are shown as mean±SEM of at least three independent experiments; *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.005. w/o, without.

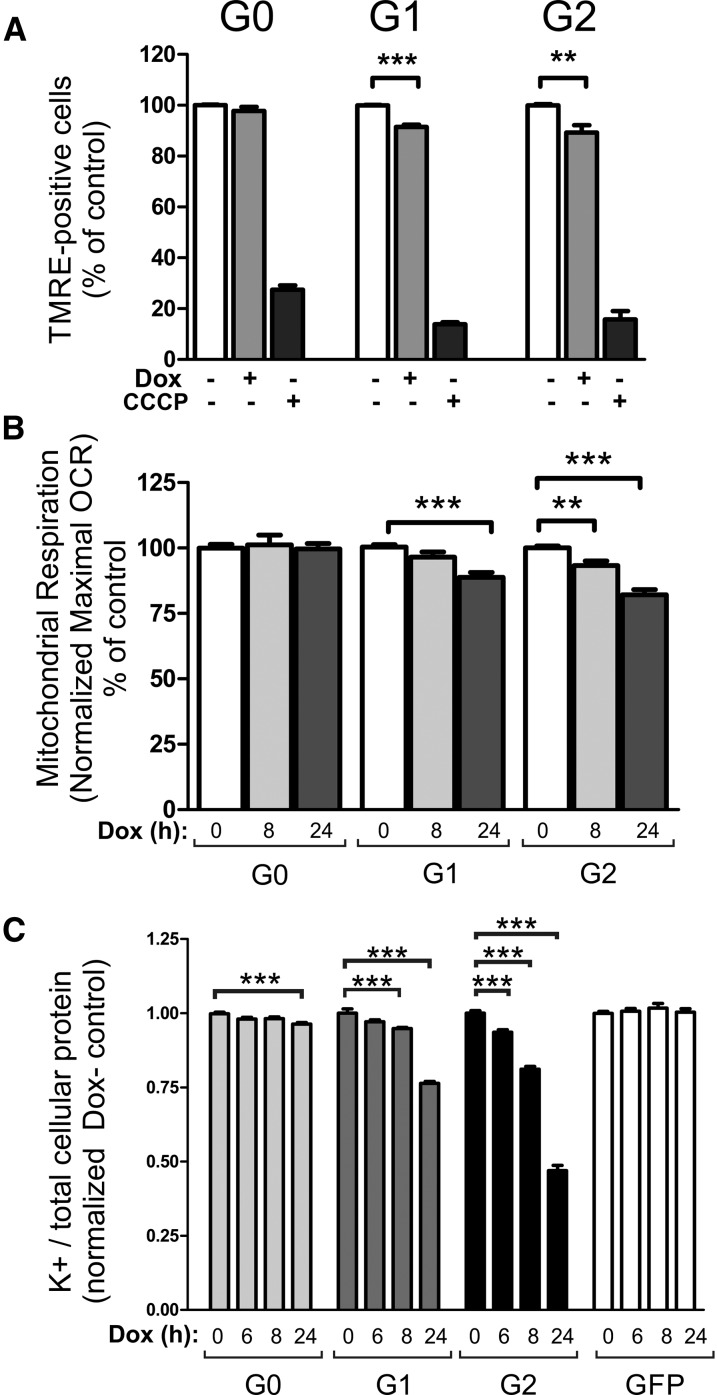

APOL1 RRVs Cause Mitochondrial Dysfunction and K+ Depletion

The low energy level which precedes reduced cell viability indicated reduced mitochondrial function in APOL1 RRV–overexpressing cells. We tested this assumption by a flow cytometry–based method in combination with tetramethylrhodamine ethyl ester (TMRE), because depolarized mitochondria with a decreased membrane potential fail to sequester this dye in living cells. As a control, we used carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenyl hydrazine (CCCP), which eliminates mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) as well as TMRE staining. The experiments demonstrated a significant decrease of TMRE-accumulating cells only in EGFP-APOL1 RRVs but not in APOL1 G0–expressing or control (Dox-) cells (Figure 6A). Measurements of the oxygen consumption rates in HEK293T and AB8 cells confirmed the effect of APOL1 RRV on mitochondrial activity (Figure 6B, Supplemental Figure 13) and demonstrated that high levels of APOL1 G1 and especially G2 are linked to reduced maximal mitochondrial respiration rates. These findings are in line with recent data,20 and moreover demonstrate that ATP depletion and mitochondrial dysfunction are caused by APOL1 RRVs independent of the N-terminal SP.

Figure 6.

APOL1 risk variant expression mediates mitochondrial dysfunction and K+ efflux. (A) Flow cytometry–based TMRE assay demonstrated an increased number of depolarized (inactive) mitochondria in GFP-APOL1 G1 and G2 but not in APOL1 G0–expressing or control cells. (B) Metabolic measurements of maximal mitochondrial respiration (OCR; oxygen consumption rate) of EGFP-APOL1–overexpressing HEK293T cells, measured with Mito Stress Test Kit using a Seahorse extracellular flux analyzer (Agilent Technologies). Basal respiration was set at 100% and baseline corrected values were normalized to noninduced control (Dox-). Overexpression of EGFP-APOL1 G1 and G2 resulted in significantly reduced maximal respiration rates after 24 hours of Dox induction. Variant G2 showed already a decreased respiration rate after 8 hours of Dox induction. APOL1 G0 overexpression had no effect on mitochondrial respiration rates (n≥12). (C) Measurement of intracellular K+ levels. EGFP-APOL1 expression results in intracellular K+ depletion detectable after 6 hours of Dox induction for variant G2 and after 8 hours for variant G1. Variant G0 expression also showed reduced cellular K+ levels after 24 hours of Dox induction. GFP-expressing cells served as additional control (n≥10).

APOL1 cytotoxicity has also been linked to K+ efflux at the PM, which leads to decreased intracellular K+ levels.21 To address this aspect, we used HEK293T cells overexpressing APOL1 G0 and RRV because these cell lines are more susceptible to APOL1-linked cellular injury (see Figures 3–5). EGFP-APOL1 expression (G0 and RRVs) was induced by administration of doxycycline at different time points and noninduced cells, or cells that only express EGFP, were used as control. This time course analysis demonstrated a significant reduction in K+/protein levels at 6 hours (G2) or 8 hours (G1) after RRV expression, suggesting that intracellular K+ depletion should be considered as an early event in APOL1-linked cytotoxicity (Figure 6).

Discussion

From an evolutionary point of view the majority of APOL proteins are not secreted, suggesting that the common endogenous functions of APOL proteins are related to an intracellular localization.22 Given the different postulated mechanisms and multiple subdomains of the APOL1 gene product,12–15,17,18,20,21,41 and the presence of a classic SP in the predominant splice isoforms, it becomes important to determine whether the intracellular APOL1, responsible for cytotoxicity, is cytosolic or membrane associated. We therefore wanted to characterize which organelle compartments are involved and determine whether differences between the kidney risk (G1 and G2) and nonrisk (G0) variants can be attributed to differential intracellular localization. Our data show an association of APOL1 G0 and RRV mutants predominantly to membranes of the ER. The similar APOL1 distribution in cells of nonhuman origin argues for evolutionarily conserved mechanisms that target APOL1 to these membranes. Hence, APOL1-mediated cell toxicity with a differential effect of the RRVs emanates at least in part from a membrane-associated or a membrane-spanning protein, rather than from a classic secreted protein, which is directed by SP cleavage to the ER lumen and then released into the circulation by fusion of exocytic vesicles with the PM.

This is consistent with observations in kidney transplantation, “that the risk to the kidney allograft travels with the donor kidney genotype.”32–36 This is also consistent with recently reported research results from Drosophila melanogaster,19,45 demonstrating that local intracellular rather than systemic APOL1 causes cell and organ injury, and likewise with results in a murine model in which APOL1 nonrisk and risk variants were specifically expressed in the glomerular podocyte.16 Taken together, this supports the formulation that predominantly intracellular membrane pools of APOL1 contribute to the observed increased risk for renal diseases.1,2,35

It is of interest to consider these findings in light of those naturally occurring APOL1 splice isoforms which lack predicted SP sequences.29,31 It is also noteworthy that cells in culture, including human hepatic cells, demonstrate little or no capacity for high-level secretion of APOL1, even under a strong SP, whereas the murine transgene with the SP shows robust secretion into the circulation.24 Thus, it appears that the intact classic secretory capacity provides a pathway for secretion without cell injury, whereas intracellular APOL1 membrane-association to the ER or mitochondria is associated with cell injury wherein the RRVs are more toxic than G0, without any discernible difference in membrane localization. This conclusion is also in line with previous in vitro studies showing that bacterially expressed APOL1 lacking the SP bind to synthetic planar lipid bilayers or purified mitochondria,23,46 and fits with earlier in silico predictions that postulated up to three hydrophobic putative membrane-spanning helices in the APOL1 protein sequence.3

The activation of cellular stress pathways, increased levels of autophagic marker LC3-II, decreased cell viability, as well as reduced intracellular K+ and mitochondrial respiration, are independent of the SP.

A recent study suggested that the above-mentioned cellular effects are accompanied by elevated K+ efflux out of the cell via an ion channel activity of APOL1 RRVs at the PM.21,46 In contrast, our data demonstrated a predominant ER and mitochondrial localization of all APOL1 variants. This rather suggests that APOL1 RRV–linked cell-damaging effects (e.g., cell swelling, endolysosomal disturbances, or increased PM permeability) are early but secondary consequences of altered functions of APOL1 RRVs at the ER and mitochondria. Strikingly, accumulating evidence identified the ER and mitochondria as signaling hubs, which control the crosstalk between cellular rescue or programmed cell death (for review see40,47,48). Therefore, it is of interest that especially membranes of the ER are functionally connected to other cellular organelles by ER-mitochondria, ER-Golgi, ER-endosome, or even ER-PM contact sites.40,47

APOL1 localization to the ER and mitochondria offers the intriguing possibility that increased APOL1 expression modulates the activity of biosynthesis, protein processing, and the intracellular energy level. Previous studies showed that mitochondrial dysfunction associates with cytotoxicity of the RRV.20,49 Indeed, the activation of AMPK signaling identified herein, reduction of ATP levels, and altered mitochondrial function in cells expressing APOL1 G1 and G2, seem to favor a mechanism in which reduced cell viability is caused by an APOL1-mediated cellular energy crisis. The energy-sensing AMP-activated kinase might play a key role in these processes, because AMPK controls both the destruction of defective, as well as the biogenesis of novel, mitochondria.43

Ma et al. have questioned the primacy of K+ efflux in temporal comparisons of the relationship of cellular K+ depletion to mitochondrial dysfunction.20 This study identified activation of stress kinases, energy depletion, and K+ reduction as early events in APOL1-linked cellular injury. Thus, it remains open what are first initial and what are consequent events in APOL1 cytotoxicity. In this context, it should be considered that the elucidation of primary and secondary steps in APOL1-associated cell injury is also a question of the sensitivity of the assays utilized, the methods, and the applied experimental cell systems.

In this regard also, it is important to note that ATP depletion could also be a consequence of increased ATP consumption. AMPK activation, for example, triggers autophagic inactivation of mitochondria (mitophagy), which in turn could result in reduced cellular respiration rates. On the other hand, a reduced cellular energy supply may in turn influence many cellular processes, including intracellular vesicular trafficking, the homeostasis of membrane potentials, or protein and membrane biosynthesis.43,44

We and others observed no obvious differences between the localization of APOL1 G0 and RRVs G1 and G2.20 Therefore, we hypothesize that APOL1 G0 and RRV must have differential molecular properties at these membranes themselves, most probably via altered APOL1 protein-protein or protein-lipid interactions. Taken together, these observations suggest that APOL1-associated cellular injury is exacerbated especially in RRVs as a consequence of decreasing ER- and mitochondria-associated functions and its subsequent downstream consequences such as programmed cell death or, as recently shown, pyroptosis.16,18,24 This would be consistent with the notion of signal 1 and signal 2 in activation of inflammatory cascades, in response to K+ efflux, which might also play a role in APOL1 injury of podocytes.50 The current findings are also consistent with a gain-of-function model for cell injury, as per previous formulations.7,51 However, future cell biologic studies are needed to decipher the molecular details of APOL1 at these membranes, and to understand why cells that express high levels of APOL1 RRV are probably less resistant to viral or nonviral second hits and why RRVs are associated with such a broad spectrum of glomerular diseases.

Concise Methods

Cloning and Constructs

The mCherry-Sec61β (addgene #49155), -Rab5 (addgene #49201), and -Rab7 plasmids (addgene #61804) were kind gifts from Gia Voeltz.52–54 The pmRFP-LC3 (addgene #21075) plasmid was a gift from Tamotsu Yoshimori55 and the plasmid encoding mCherry-tagged N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase2 (GalNac) was a gift of Brian Storrie.56 The plasmid encoding mCherry-tagged N-acetyl-galactosaminyltransferase 2 (GalNac) is a gift of Brian Storrie and has been used as described before.56 The coding sequence of human APOL1 (variant A, aa 1–398) was amplified using a human cDNA library derived from AB8 podocytes57 and cloned into pEGFP-N1 (BD Clontech) and pENTR-D/TOPO vectors according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Thermo Fisher Scientific). APOL1 wildtype (G0 variant) cDNA was mutagenized to generate the APOL1 G1 point (S342G/I384M) and APOL1 G2 deletion (Δ388N389Y) mutants. Untagged APOL1 cDNA inserts or APOL1 variants lacking the SP (aa 1–27) were cloned into pENTR, or pENTR-EGFP, respectively, and shuttled into a modified pInducer21-Puro destination vector58 via LR Clonase according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Thermo Fisher Scientific). All constructs were verified by DNA sequencing. Details concerning constructs are summarized in Supplemental Table 1 and primer sequences are available from D.G. and T.W.

Generation of Stable Cell Lines

Stable cell lines were generated as described previously.58 Briefly, a lentiviral containing supernatant was produced by transfection of HEK293T cells with psPAX2 and pMD2.G helper plasmids and modified pINDUCER2159 pInd21P-plasmids encoding APOL1 G0/G1/G2, EGFP, or EGFP-APOL1 G0/G1/G2, respectively. Next, the virus-containing supernatant was collected and filtered through a sterile 0.45 µm syringe-driven filter unit (EMD Millipore). Subsequently, the HEK293T and AB8 podocyte cells (grown in six-well dishes) were infected for 24 hours using one volume (up to 2 ml) of fresh DMEM medium and one volume of the virus-containing filtrate supplemented with polybrene (final concentration 8 µg/ml). Thereafter, the virus-containing medium was replaced by fresh medium and cells were regenerated for 24 hours. Afterward, cells were selected by puromycin treatment (4 µg/ml, HEK293T; 2 µg/ml, AB8). Overexpression of ectopic GFP-tagged APOL1 variants in the stable cell populations were verified by western blot, IF analysis, and qRT-PCR.58,60

Cell Culture and Transient Transfection of Cell Lines

HEK293T and CV1 cells were cultivated in standard DMEM medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with 10% FCS and 1% antibiotics (penicillin/streptomycin). Stable human immortalized podocytes (AB8 cells) were cultivated in standard RPMI 1640 medium (Sigma-Aldrich) containing 10% FCS, supplements, and 1% antibiotics (Pen/Strep).61 Transient transfection of cell lines was performed as described previously,58 or according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Lipofectamine 2000; Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Real-Time PCR

APOL1 gene expression of profiles in cells was analyzed by real-time PCR. Total RNA from HEK293T cells and HEK293T cell lines expressing EGFP-APOL1 variants were isolated using RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). For cDNA synthesis, 2 µg total RNA was used with the SuperScript-III First-Strand Synthesis SuperMix (Invitrogen, Darmstadt, Germany). Real-time PCR was performed using SYBR Green PCR Master Mix on an ABI PRISM 7700 Sequence Detection System. Specific primer pairs for APOL1 (APOL1_F: 5′-TGATAATGAGGCCTGGAACG-3′; APOL1_R: 5′-TACTGCTGGCCTTTATCGTG-3′) and 18rRNA (18S_F: 5′-ATCAACTTTCGATGGTAGTCG-3′; 18S_R: 5′-TCCTTGGATGTGGTAGCCG-3′) were used. All instruments and reagents were purchased from Applied Biosystems (Darmstadt, Germany). Relative gene expression values were evaluated with the 2−ΔΔCt method62 using 18S rRNA standard.

Western Blot Analysis and Antibodies

Western blot analysis was performed as described previously.58 After boiling for 5 minutes, equal volumes of cell lysates were separated using 8%–15% SDS-PAGE gels (Bio-Rad). Proteins were transferred to a PVDF membrane (EMD Millipore) and incubated for 1 hour at room temperature (RT) in blocking buffer (5% skim milk powder dissolved in TBS containing 0.05% Tween-20 [TBS-T]). The monoclonal JL-8 antibody against GFP (#632380) was from Takara Bio Europe (Clontech). The rabbit antibody against APOL1 was from Sigma-Aldrich (HPA018885). SAPK/JNK (#4631), phospho-SAPK/JNK (#9252), p38 (#8690), phospho-p38 (#4631), AMPK (#5832), and phospho-AMPK (#2535) were from Cell Signaling Technologies. The rabbit antibodies against LC3-I/-II (#NB100–2200) were purchased from Novus, and against α-Actinin 4 (#ALX-210–356) from Enzo/Alexis, respectively. The monoclonal murine antibody against Calnexin (#610523) was from BD Transduction Laboratories, and against β-Tubulin from Sigma-Aldrich (#T8328). All primary antibodies were used in a 1:1000 dilution in blocking buffer and incubated at 4°C overnight. After washing three times with TBS-T, the membrane was incubated with horseradish peroxidase–coupled secondary antibodies (Jackson Immunoresearch) diluted 1:5000 in blocking buffer for 45 minutes at RT. After washing three times, the western blot was developed using a chemiluminescence detection reagent (Roche).

Imaging of Cell Lines and IF Analysis of Cells

Living cells, expressing EGFP-APOL1 fusion proteins, were grown on µ-dishes (Ibidi) or cover slips and photographed directly. Labeling of cells with ER-Tracker Red Dye (Ex 587 nm/Em 615 nm; #E34250), MitoTracker Red CMXRos (Ex 579 nm/Em 599 nm; #M7512), or MitoTracker Red FM (Ex 581 nm/Em 644 nm; #M22425) was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Images were obtained using an Observer Z1 microscope with Apotome, Axiocam MRm (Zeiss), and EC Plan Apochromat 63×/1.40 Oil M27, or EC Plan-Neofluar 40×/1.30 Oil DIC M27 objectives, respectively. For detecting GFP-tagged fusion proteins we used the filter set 38 HE eGFP shift free (Zeiss). Filter sets 43 HE Cy3 shift free (Zeiss) or 64 HE mPlum shift free (Zeiss) were used to detect red or far red labeling.

Live cell imaging movies were performed on a fully automated iMIC-based microscope from FEI/Till Photonics, using an Olympus 100×1.4 NA objective and a DPSS laser at 488 nm (Cobolt Calypso, 75 mW) as light source, selected and through an AOTF and directed through a broadband fiber to the microscope. A galvanometer-driven two-axis scan head was used to adjust laser incidence TIRF angles. Images were collected every 150 or 200 milliseconds using an Imago-QE Sensicam camera using typical filter settings for excitation and emission for GFP fluorescence. Acquisition was controlled by LiveAcquisition software (Till Photonics). Image series were processed using Fiji: First, images were averaged to obtain comparable time intervals of 600 milliseconds. Next, images were background-subtracted using the respective algorithm in Fiji (radius 220 px) and smoothened using a Gauss Filter (radius=1). Finally, the image series were contrast-adjusted and combined to one movie. AB8 podocytes expressing ApoL1-GFP variants G0, G1, or G2 were followed over time for 30 seconds using TIRF microscopy. Zoomed areas of the cell peripheries are shown.

For indirect IF analysis, AB8 podocytes, HEK293T, or CV1 cells growing on coverslips were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde supplemented with 4% sucrose in PBS at RT for 20 minutes. Samples were washed with PBS and then incubated for 10 minutes in 50 mM NH4Cl in PBS to quench reactive amino groups. After washing with PBS, cells were permeabilized in PBS containing 0.2% Triton-X-100 for 5 minutes and washed three times in PBS containing 0.2% Triton-X-100 and 0.2% gelatin (PBS-TG). Samples were blocked with 10% goat serum diluted in PBS-TG for 20 minutes at RT. IF staining was performed by incubating cells for 1 hour at RT with primary antibodies diluted in PBS-TG containing 2% goat serum. After antibody incubation in PBS-TG, cells were washed and incubated for 45 minutes at RT with secondary goat anti-mouse, or goat anti-rabbit IgGs (1:1000) conjugated to Alexa 594 or Alexa 647 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) diluted in PBS-TG containing 2% goat serum. After washing in PBS, samples were rinsed in water and mounted in Mowiol or Crystal Clear Mount Medium (Sigma-Aldrich), respectively. Image files in ZVI format (Zeiss Axiovision software 4.8) were further processed by ImageJ (http://imagej.nih.gov/ij/). After that, final images were mounted to complex figures by CorelDRAW Graphics suite ×6 software (Adobe).

Measurements of Metabolic Activity

Metabolic measurements were performed using the XFp or XF96 Extracellular Flux Analyzer (Seahorse Biosciences) in combination with the Mito stress test kit (Seahorse Biosciences). HEK293T cells (50,000 cells/well) or human cultured podocytes (AB8; 20,000 cells/well) were seeded on XFp or XFe96 plates and incubated with or without doxycycline (125 ng/ml) for 8 and 24 hours before starting the measurements. For HEK293T cells, the XFp/XF96 plates were coated with poly-D-lysine before seeding. The culture medium was replaced 1 hour before start of the assay by Seahorse Medium (DMEM XF Base Medium; Seahorse Bioscience; supplemented with 10 mM Glucose, 1 mM Pyruvate, 2 mM Glutamine, pH 7.4). The cells were incubated for 1 hour at 37°C in a CO2-free atmosphere. Afterward, the oxygen consumption rate was measured before and after treatments with oligomycin (2 µM), FCCP (carbonyl cyanide 4-[trifluoromethoxy]phenylhydrazone; 0.5 µM), antimycin A, and rotenone (0.5 µM each), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Mitochondrial membrane potential Measurements

Depolarized or inactive mitochondria have a decreased membrane potential and fail to sequester TMRE (tetramethylrhodamine ethyl ester). Therefore, TMRE fluorescence was used to monitor mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) measured by flow cytometry. As setup control, cells were treated with CCCP, which is an “ionophore uncoupler” of oxidative phosphorylation and therefore eliminates MMP and TMRE staining. CCCP controls were pretreated with CCCP (10 µM; Sigma-Aldrich) 10 minutes before TMRE addition. To determine MMP of EGFP-APOL1 G0–, G1–, and G2–expressing cells, APOL1 expression was induced for 24 hours and cells were treated with TMRE (100 nM; Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 minutes at 37°C in 5% CO2, by adding TMRE directly to the culture medium. Medium was removed and cells were detached by Accutase treatment (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 5 minutes. Cells were washed in PBS, centrifuged (5 minutes, 1200 rpm), and resuspended in PBS. TMRE-fluorescence signal was determined by FACS in a BD FACSCalibur analyzer and analyzed with BD CellQuest Pro Software. TMRE values of at least 20,000 living EGFP-APOL1–expressing cells were normalized to noninduced controls and shown as TMRE-positive cells (% of control).

Determination of Cell Viability and Cytotoxicity

Realtime cell viability measurements were performed via the RealTime-Glo MT Cell Viability Assay (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 10,000 HEK cells in 50 µl medium were seeded on 96-well plates with a white bottom (Nunc). After adherence of the cells, 50 µl 1× RealTime-Glo enzyme-substrate mix diluted in medium was added to the cells. Cells were treated with or without 125 ng/ml doxycycline, respectively. Before measuring cell viability, plates were incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 10 minutes. After addition of the RealTime-Glo enzyme-substrate mix, the cell viability was measured at the indicated time points. The luminescence was measured using a microplate reader (TECAN).

For determination of cell viability via MTT assay: 10,000 HEK cells were seeded in a volume of 100 µl on a 96-well plate with transparent bottom (Greiner). Cells were treated with or without doxycycline (125 ng/ml) for indicated time periods. Afterward, cells were treated with 10 µl MTT solution (5 mg/ml Thiazolyl Blue Tetrazolium Bromide in PBS; Sigma) for 3 hours at 37°C. The medium was removed and cells were treated with 100 µl lysis reagent (40% DMF [N,N-Dimethylformamide; Sigma] in H20 with 10% SDS) for 15 minutes on an orbital shaker. The absorbance of the formazan solution was measured via a microplate reader (TECAN) at a wavelength of 550 nm.

For determination of cytotoxicity: cytotoxicity measurements were performed via the CytoTox-Glo Cytotoxicity Assay (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s manual. Twenty thousand HEK cells were seeded in a volume of 100 µl on a 96-well plate with white bottom (Nunc). Cells were treated with or without doxycycline (125 ng/ml) for 24 hours before AAF-Glo reagent (4× reagent) was added, and incubated for 15 minutes at 37°C, to measure the luminescence of dead cells. Afterward, the cells were treated with lysis reagent for 15 minutes at 37°C to measure the total cell luminescence. The relative proportion of dead cells compared with total cells was calculated. The luminescence was measured via a microplate reader (TECAN).

ATP Measurements

Cellular ATP levels were measured via the CellTiter-Glo Luminescent Cell Viability Assay (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 20,000 HEK cells were seeded on 96-well plates with a white bottom in 100 µl medium (Nunc). Cells were treated with 125 ng/ml doxycycline for indicated times. Before addition of the reaction reagent the plate was equilibrated at RT for 30 minutes. The cells were treated with 100 µl of CellTiter-Glo Reagent and mixed for 2 minutes on an orbital shaker to induce cell lysis. The plate was incubated at RT for 10 minutes before the luminescence was measured using a microplate reader (TECAN).

K+ Assays

HEK293T cells (that show the more robust cytotoxic effects) were seeded on 12-well plates and EGFP-APOL1 (G0 and RRVs) expression was induced by administration of doxycycline for 6, 8, and 24 hours. Noninduced cells and cells only expressing GFP were used as controls. After induction, cells were washed, and medium was replaced by 200 µl pure water (Aqua Bidest) to cause osmotic lysis of the cells, and frozen at −80°C. The supernatant that now contained all soluble components of the cells (ions, proteins, etc.) was collected and centrifuged (14,000 rpm, 5 minutes) to clear supernatant from cell debris. Subsequently, protein and K+ concentrations of the cell supernatants were determined, according to the standard operation urine application procedure recommended by the manufacturer, with an automated Cobas 8000 analyzer system (Roche).

Statistical Analyses

Tests for statistical significance of normally distributed data were performed with GraphPad PRISM software with a t test for comparison of two groups of data, or one-way ANOVA with a Bonferroni correction for comparing three or more groups of data. If not otherwise indicated, all data are given as mean of at least three independent measurements.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Gia Voeltz, Tamotsu Yoshimori, and Brian Storrie for plasmids; Truc Van Le, Beate Surmann, Katrin Beul, Ute Neugebauer, Giovanna Di Marco, Manfred Fobker, Veronika Simon, and Simona Lüttgenau for excellent technical support; and all members of the contributing laboratories for fruitful discussions. We thank Karin Busch, Heinz Wiendl, and Luisa Klotz for access to the Seahorse Analyzer.

The work was supported by the Medical Faculty of the University of Muenster (I-SC121320, U.M. and T.W.), the Israel Science Foundation (182/15, K.S.), the German Research Foundation (SFB1009-B10, R.W.-S. and H.P.; and WE 3551/3-1, T.W.), and the Ernest and Bonnie Beutler Foundation (K.S.).

This work contains parts of the thesis of D.G. and the masters’ thesis of D.M.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2016111220/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Genovese G, Friedman DJ, Ross MD, Lecordier L, Uzureau P, Freedman BI, Bowden DW, Langefeld CD, Oleksyk TK, Uscinski Knob AL, Bernhardy AJ, Hicks PJ, Nelson GW, Vanhollebeke B, Winkler CA, Kopp JB, Pays E, Pollak MR: Association of trypanolytic ApoL1 variants with kidney disease in African Americans. Science 329: 841–845, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tzur S, Rosset S, Shemer R, Yudkovsky G, Selig S, Tarekegn A, Bekele E, Bradman N, Wasser WG, Behar DM, Skorecki K: Missense mutations in the APOL1 gene are highly associated with end stage kidney disease risk previously attributed to the MYH9 gene. Hum Genet 128: 345–350, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thomson R, Genovese G, Canon C, Kovacsics D, Higgins MK, Carrington M, Winkler CA, Kopp J, Rotimi C, Adeyemo A, Doumatey A, Ayodo G, Alper SL, Pollak MR, Friedman DJ, Raper J: Evolution of the primate trypanolytic factor APOL1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111: E2130–E2139, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pays E, Vanhollebeke B, Vanhamme L, Paturiaux-Hanocq F, Nolan DP, Pérez-Morga D: The trypanolytic factor of human serum. Nat Rev Microbiol 4: 477–486, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Freedman BI, Kopp JB, Langefeld CD, Genovese G, Friedman DJ, Nelson GW, Winkler CA, Bowden DW, Pollak MR: The apolipoprotein L1 (APOL1) gene and nondiabetic nephropathy in African Americans. J Am Soc Nephrol 21: 1422–1426, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kopp JB, Nelson GW, Sampath K, Johnson RC, Genovese G, An P, Friedman D, Briggs W, Dart R, Korbet S, Mokrzycki MH, Kimmel PL, Limou S, Ahuja TS, Berns JS, Fryc J, Simon EE, Smith MC, Trachtman H, Michel DM, Schelling JR, Vlahov D, Pollak M, Winkler CA: APOL1 genetic variants in focal segmental glomerulosclerosis and HIV-associated nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 22: 2129–2137, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kasembeli AN, Duarte R, Ramsay M, Mosiane P, Dickens C, Dix-Peek T, Limou S, Sezgin E, Nelson GW, Fogo AB, Goetsch S, Kopp JB, Winkler CA, Naicker S: APOL1 risk variants are strongly associated with HIV-associated nephropathy in black South Africans. J Am Soc Nephrol 26: 2882–2890, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Larsen CP, Beggs ML, Saeed M, Walker PD: Apolipoprotein L1 risk variants associate with systemic lupus erythematosus-associated collapsing glomerulopathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 24: 722–725, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Freedman BI, Langefeld CD, Andringa KK, Croker JA, Williams AH, Garner NE, Birmingham DJ, Hebert LA, Hicks PJ, Segal MS, Edberg JC, Brown EE, Alarcón GS, Costenbader KH, Comeau ME, Criswell LA, Harley JB, James JA, Kamen DL, Lim SS, Merrill JT, Sivils KL, Niewold TB, Patel NM, Petri M, Ramsey-Goldman R, Reveille JD, Salmon JE, Tsao BP, Gibson KL, Byers JR, Vinnikova AK, Lea JP, Julian BA, Kimberly RP; Lupus Nephritis–End‐Stage Renal Disease Consortium : End-stage renal disease in African Americans with lupus nephritis is associated with APOL1. Arthritis Rheumatol 66: 390–396, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Larsen CP, Beggs ML, Walker PD, Saeed M, Ambruzs JM, Messias NC: Histopathologic effect of APOL1 risk alleles in PLA2R-associated membranous glomerulopathy. Am J Kidney Dis 64: 161–163, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Genovese G, Friedman DJ, Pollak MR: APOL1 variants and kidney disease in people of recent African ancestry. Nat Rev Nephrol 9: 240–244, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vanhollebeke B, Pays E: The function of apolipoproteins L. Cell Mol Life Sci 63: 1937–1944, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhaorigetu S, Wan G, Kaini R, Jiang Z, Hu CAA: ApoL1, a BH3-only lipid-binding protein, induces autophagic cell death. Autophagy 4: 1079–1082, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wan G, Zhaorigetu S, Liu Z, Kaini R, Jiang Z, Hu CA: Apolipoprotein L1, a novel Bcl-2 homology domain 3-only lipid-binding protein, induces autophagic cell death. J Biol Chem 283: 21540–21549, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lan X, Wen H, Lederman R, Malhotra A, Mikulak J, Popik W, Skorecki K, Singhal PC: Protein domains of APOL1 and its risk variants. Exp Mol Pathol 99: 139–144, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beckerman P, Bi-Karchin J, Park ASD, Qiu C, Dummer PD, Soomro I, Boustany-Kari CM, Pullen SS, Miner JH, Hu CA, Rohacs T, Inoue K, Ishibe S, Saleem MA, Palmer MB, Cuervo AM, Kopp JB, Susztak K: Transgenic expression of human APOL1 risk variants in podocytes induces kidney disease in mice. Nat Med 23: 429–438, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taylor HE, Khatua AK, Popik W: The innate immune factor apolipoprotein L1 restricts HIV-1 infection. J Virol 88: 592–603, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lan X, Jhaveri A, Cheng K, Wen H, Saleem MA, Mathieson PW, Mikulak J, Aviram S, Malhotra A, Skorecki K, Singhal PC: APOL1 risk variants enhance podocyte necrosis through compromising lysosomal membrane permeability. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 307: F326–F336, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kruzel-Davila E, Shemer R, Ofir A, Bavli-Kertselli I, Darlyuk-Saadon I, Oren-Giladi P, Wasser WG, Magen D, Zaknoun E, Schuldiner M, Salzberg A, Kornitzer D, Marelja Z, Simons M, Skorecki K: APOL1-mediated cell injury involves disruption of conserved trafficking processes. J Am Soc Nephrol 28: 1117–1130, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ma L, Chou JW, Snipes JA, Bharadwaj MS, Craddock AL, Cheng D, Weckerle A, Petrovic S, Hicks PJ, Hemal AK, Hawkins GA, Miller LD, Molina AJ, Langefeld CD, Murea M, Parks JS, Freedman BI: APOL1 renal-risk variants induce mitochondrial dysfunction. J Am Soc Nephrol 28: 1093–1105, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Olabisi OA, Zhang J-Y, VerPlank L, Zahler N, DiBartolo S 3rd, Heneghan JF, Schlöndorff JS, Suh JH, Yan P, Alper SL, Friedman DJ, Pollak MR: APOL1 kidney disease risk variants cause cytotoxicity by depleting cellular potassium and inducing stress-activated protein kinases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 113: 830–837, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith EE, Malik HS: The apolipoprotein L family of programmed cell death and immunity genes rapidly evolved in primates at discrete sites of host-pathogen interactions. Genome Res 19: 850–858, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vanwalleghem G, Fontaine F, Lecordier L, Tebabi P, Klewe K, Nolan DP, Yamaryo-Botté Y, Botté C, Kremer A, Burkard GS, Rassow J, Roditi I, Pérez-Morga D, Pays E: Coupling of lysosomal and mitochondrial membrane permeabilization in trypanolysis by APOL1. Nat Commun 6: 8078, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cheng D, Weckerle A, Yu Y, Ma L, Zhu X, Murea M, Freedman BI, Parks JS, Shelness GS: Biogenesis and cytotoxicity of APOL1 renal risk variant proteins in hepatocytes and hepatoma cells. J Lipid Res 56: 1583–1593, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weckerle A, Snipes JA, Cheng D, Gebre AK, Reisz JA, Murea M, Shelness GS, Hawkins GA, Furdui CM, Freedman BI, Parks JS, Ma L: Characterization of circulating APOL1 protein complexes in African Americans. J Lipid Res 57: 120–130, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hajduk SL, Moore DR, Vasudevacharya J, Siqueira H, Torri AF, Tytler EM, Esko JD: Lysis of Trypanosoma brucei by a toxic subspecies of human high density lipoprotein. J Biol Chem 264: 5210–5217, 1989 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vanhamme L, Paturiaux-Hanocq F, Poelvoorde P, Nolan DP, Lins L, Van Den Abbeele J, Pays A, Tebabi P, Van Xong H, Jacquet A, Moguilevsky N, Dieu M, Kane JP, De Baetselier P, Brasseur R, Pays E: Apolipoprotein L-I is the trypanosome lytic factor of human serum. Nature 422: 83–87, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Molina-Portela MP, Samanovic M, Raper J: Distinct roles of apolipoprotein components within the trypanosome lytic factor complex revealed in a novel transgenic mouse model. J Exp Med 205: 1721–1728, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khatua AK, Cheatham AM, Kruzel ED, Singhal PC, Skorecki K, Popik W: Exon 4-encoded sequence is a major determinant of cytotoxicity of apolipoprotein L1. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 309: C22–C37, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Freedman BI, Skorecki K: Gene-gene and gene-environment interactions in apolipoprotein L1 gene-associated nephropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 9: 2006–2013, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nichols B, Jog P, Lee JH, Blackler D, Wilmot M, D’Agati V, Markowitz G, Kopp JB, Alper SL, Pollak MR, Friedman DJ: Innate immunity pathways regulate the nephropathy gene Apolipoprotein L1. Kidney Int 87: 332–342, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Freedman BI, Pastan SO, Israni AK, Schladt D, Julian BA, Gautreaux MD, Hauptfeld V, Bray RA, Gebel HM, Kirk AD, Gaston RS, Rogers J, Farney AC, Orlando G, Stratta RJ, Mohan S, Ma L, Langefeld CD, Bowden DW, Hicks PJ, Palmer ND, Palanisamy A, Reeves-Daniel AM, Brown WM, Divers J: APOL1 genotype and kidney transplantation outcomes from deceased African American donors. Transplantation 100: 194–202, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Freedman BI, Julian BA, Pastan SO, Israni AK, Schladt D, Gautreaux MD, Hauptfeld V, Bray RA, Gebel HM, Kirk AD, Gaston RS, Rogers J, Farney AC, Orlando G, Stratta RJ, Mohan S, Ma L, Langefeld CD, Hicks PJ, Palmer ND, Adams PL, Palanisamy A, Reeves-Daniel AM, Divers J: Apolipoprotein L1 gene variants in deceased organ donors are associated with renal allograft failure. Am J Transplant 15: 1615–1622, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reeves-Daniel AM, DePalma JA, Bleyer AJ, Rocco MV, Murea M, Adams PL, Langefeld CD, Bowden DW, Hicks PJ, Stratta RJ, Lin JJ, Kiger DF, Gautreaux MD, Divers J, Freedman BI: The APOL1 gene and allograft survival after kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant 11: 1025–1030, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Friedman DJ, Pollak MR: Apolipoprotein L1 and kidney disease in African Americans. Trends Endocrinol Metab 27: 204–215, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee BT, Kumar V, Williams TA, Abdi R, Bernhardy A, Dyer C, Conte S, Genovese G, Ross MD, Friedman DJ, Gaston R, Milford E, Pollak MR, Chandraker A: The APOL1 genotype of African American kidney transplant recipients does not impact 5-year allograft survival. Am J Transplant 12: 1924–1928, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kruzel-Davila E, Wasser WG, Aviram S, Skorecki K: APOL1 nephropathy: From gene to mechanisms of kidney injury. Nephrol Dial Transplant 31: 349–358, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Madhavan SM, O’Toole JF, Konieczkowski M, Ganesan S, Bruggeman LA, Sedor JR: APOL1 localization in normal kidney and nondiabetic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 22: 2119–2128, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ma L, Shelness GS, Snipes JA, Murea M, Antinozzi PA, Cheng D, Saleem MA, Satchell SC, Banas B, Mathieson PW, Kretzler M, Hemal AK, Rudel LL, Petrovic S, Weckerle A, Pollak MR, Ross MD, Parks JS, Freedman BI: Localization of APOL1 protein and mRNA in the human kidney: Nondiseased tissue, primary cells, and immortalized cell lines. J Am Soc Nephrol 26: 339–348, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Phillips MJ, Voeltz GK: Structure and function of ER membrane contact sites with other organelles. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 17: 69–82, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kruzel-Davila E, Shemer R, Ofir A, Bavli-Kertselli I, Darlyuk-Saadon I, Oren-Giladi P, Wasser WG, Magen D, Zaknoun E, Schuldiner M, Salzberg A, Kornitzer D, Marelja Z, Simons M, Skorecki K. APOL1–Mediated Cell Injury Involves Disruption of Conserved Trafficking Processes. J Am Soc Nephrol 28: 1117–1130, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Senft D, Ronai ZA: UPR, autophagy, and mitochondria crosstalk underlies the ER stress response. Trends Biochem Sci 40: 141–148, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mihaylova MM, Shaw RJ: The AMPK signalling pathway coordinates cell growth, autophagy and metabolism. Nat Cell Biol 13: 1016–1023, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hardie DG, Ross FA, Hawley SA: AMPK: A nutrient and energy sensor that maintains energy homeostasis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 13: 251–262, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fu Y, Zhu JY, Richman A, Zhang Y, Xie X, Das JR, Li J, Ray PE, Han Z: APOL1-G1 in hephrocytes induces hypertrophy and accelerates cell death. J Am Soc Nephrol 28: 1106–1116, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thomson R, Finkelstein A: Human trypanolytic factor APOL1 forms pH-gated cation-selective channels in planar lipid bilayers: Relevance to trypanosome lysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112: 2894–2899, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Marchi S, Patergnani S, Pinton P: The endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria connection: One touch, multiple functions. Biochim Biophys Acta 1837: 461–469, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Galluzzi L, Kepp O, Kroemer G: Mitochondria: Master regulators of danger signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 13: 780–788, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Granado D, Schulze U, Müller D, Lüttgenau S, Popik W, Skorecki K, Pavenstädt H, and Weide T: Renal risk variants of ApoL1 mediate mitochondrial dysfunction and cell death in podocytes [Abstract]. Nephron 132: 245–291, 2016. 27029049 [Google Scholar]

- 50.Muñoz-Planillo R, Kuffa P, Martínez-Colón G, Smith BL, Rajendiran TM, Núñez G: K+ efflux is the common trigger of NLRP3 inflammasome activation by bacterial toxins and particulate matter. Immunity 38: 1142–1153, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Limou S, Dummer PD, Nelson GW, Kopp JB, Winkler CA: APOL1 toxin, innate immunity, and kidney injury. Kidney Int 88: 28–34, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shibata Y, Voss C, Rist JM, Hu J, Rapoport TA, Prinz WA, Voeltz GK: The reticulon and DP1/Yop1p proteins form immobile oligomers in the tubular endoplasmic reticulum. J Biol Chem 283: 18892–18904, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rowland AA, Chitwood PJ, Phillips MJ, Voeltz GK: ER contact sites define the position and timing of endosome fission. Cell 159: 1027–1041, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zurek N, Sparks L, Voeltz G: Reticulon short hairpin transmembrane domains are used to shape ER tubules. Traffic 12: 28–41, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kimura S, Noda T, Yoshimori T: Dissection of the autophagosome maturation process by a novel reporter protein, tandem fluorescent-tagged LC3. Autophagy 3: 452–460, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schuberth CE, Tängemo C, Coneva C, Tischer C, Pepperkok R: Self-organization of core Golgi material is independent of COPII-mediated endoplasmic reticulum export. J Cell Sci 128: 1279–1293, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Duning K, Schurek E-M, Schlüter M, Bayer M, Reinhardt H-C, Schwab A, Schaefer L, Benzing T, Schermer B, Saleem MA, Huber TB, Bachmann S, Kremerskothen J, Weide T, Pavenstädt H: KIBRA modulates directional migration of podocytes. J Am Soc Nephrol 19: 1891–1903, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schulze U, Vollenbröker B, Braun DA, Van Le T, Granado D, Kremerskothen J, Fränzel B, Klosowski R, Barth J, Fufezan C, Wolters DA, Pavenstädt H, Weide T: The Vac14-interaction network is linked to regulators of the endolysosomal and autophagic pathway. Mol Cell Proteomics 13: 1397–1411, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Meerbrey KL, Hu G, Kessler JD, Roarty K, Li MZ, Fang JE, Herschkowitz JI, Burrows AE, Ciccia A, Sun T, Schmitt EM, Bernardi RJ, Fu X, Bland CS, Cooper TA, Schiff R, Rosen JM, Westbrook TF, Elledge SJ: The pINDUCER lentiviral toolkit for inducible RNA interference in vitro and in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: 3665–3670, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Duning K, Rosenbusch D, Schlüter MA, Tian Y, Kunzelmann K, Meyer N, Schulze U, Markoff A, Pavenstädt H, Weide T: Polycystin-2 activity is controlled by transcriptional coactivator with PDZ binding motif and PALS1-associated tight junction protein. J Biol Chem 285: 33584–33588, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schulze U, Vollenbröker B, Kühnl A, Granado D, Bayraktar S, Rescher U, Pavenstädt H, Weide T: Cellular vacuolization caused by overexpression of the PIKfyve-binding deficient Vac14 L156R is rescued by starvation and inhibition of vacuolar-ATPase. Biochim Biophys Acta 1864: 749–759, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD: Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Δ Δ C(T)) Method. Methods 25: 402–408, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.