Abstract

Overactivation of Src has been linked to the pathogenesis of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD). This phase 2, multisite study assessed the efficacy and safety of bosutinib, an oral dual Src/Bcr-Abl tyrosine kinase inhibitor, in patients with ADPKD. Patients with ADPKD, eGFR≥60 ml/min per 1.73 m2, and total kidney volume ≥750 ml were randomized 1:1:1 to bosutinib 200 mg/d, bosutinib 400 mg/d, or placebo for ≤24 months. The primary endpoint was annualized rate of kidney enlargement in patients treated for ≥2 weeks who had at least one postbaseline magnetic resonance imaging scan that was preceded by a 30-day washout (modified intent-to-treat population). Of 172 enrolled patients, 169 received at least one study dose. Per protocol amendment, doses for 24 patients who initially received bosutinib at 400 mg/d were later reduced to 200 mg/d. The annual rate of kidney enlargement was reduced by 66% for bosutinib 200 mg/d versus placebo (1.63% versus 4.74%, respectively; P=0.01) and by 82% for pooled bosutinib versus placebo (0.84% versus 4.74%, respectively; P<0.001). Over the treatment period, patients receiving placebo or bosutinib had similar annualized eGFR decline. Gastrointestinal and liver-related adverse events were the most frequent toxicities. In conclusion, compared with placebo, bosutinib at 200 mg/d reduced kidney growth in patients with ADPKD. The overall gastrointestinal and liver toxicity profile was consistent with the profile in prior studies of bosutinib; no new toxicities were identified. (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT01233869).

Keywords: bosutinib, ADPKD, total kidney volume, clinical trial, Src

Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) is a hereditary disorder that affects up to one in 1000 people and is characterized by the development of cysts in the kidney and other organs.1 Disease progression leads to the gradual loss of renal function, reaching ESRD in many cases.2 Clinical approaches to managing ADPKD are primarily supportive, such as focusing on hypertension and other secondary complications.2,3

ADPKD results from germ-line mutations in the PKD1 (85% of cases) or PKD2 (15% of cases) genes, with subsequent dysfunction of the gene products polycystin (PC)-1 and PC-2.1 PC-1 participates in multiprotein complexes within cell-cell adherens junctions, desmosomes, and focal adhesions that transduce intracellular signals triggered by α2β1-integrin−mediated cell matrix interactions.4–6 Dysregulation of associated signaling networks can result in epithelial cell proliferation and anomalous cell polarity/migration characteristic of renal cyst expansion.7–9 Src is a key regulator of cell matrix– and growth factor receptor–mediated signaling and is overexpressed and activated in several epithelial cancers, whereby Src inhibition results in decreased proliferation, adhesion, and migration.10–12 Src activation, specifically phosphorylation of tyrosine 418, and polycystic kidney disease (PKD) progression has been demonstrated in mouse and rat models of PKD with the degree of correlation related to disease progression.13 Thus, it has been hypothesized that Src might be a therapeutic target for the treatment of ADPKD.14

Bosutinib (SKI-606) is an oral dual Src/Bcr-Abl tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) approved for the treatment of Philadelphia chromosome–positive chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) in patients resistant/intolerant to prior imatinib.15 In mouse and rat models of PKD, bosutinib reduced kidney size and the number of renal cysts and reduced tyrosine 418 phosphorylation as indicated on immunoblots of extracts prepared from the kidneys of bosutinib-treated animals.13 Subsequent observations confirmed that Src activity is increased in human kidneys and that bosutinib reduces epithelial cell matrix adhesion.14

This phase 2 study assessed the efficacy and safety of bosutinib in patients with ADPKD.

Results

Patients

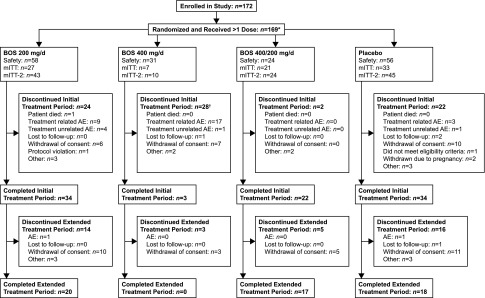

Among 172 patients enrolled, 169 received ≥1 study dose (mean [SD] age, 38.5 [7.4] years; median [range] total kidney volume [TKV], 1376.30 [751.55–7329.00] ml; median [range] eGFR, 85.90 [53.19–130.50] ml/min per 1.73 m2; Table 1). Among the safety population, 58, 31, and 56 patients received bosutinib 200, 400 mg/d, or placebo, respectively (Figure 1); 24 patients who initially received bosutinib 400 mg/d reduced the dose to 200 mg/d (per protocol amendment). Ninety-three (55%) completed and 75 (44%) discontinued from the initial treatment period, primarily owing to treatment-related adverse events (AEs; n=29 of 75 [39%]) and/or consent withdrawal (n=23 of 75 [31%]). An additional subject discontinued before the end of the initial treatment period for a total of 76 discontinuations; however, this patient had a status of “ongoing” because of an error with the subject’s summary page on the case report form. The median (range) duration of therapy for the initial treatment period was 686.0 (28–761) days for bosutinib 200 mg/d, 49.0 (5–724) days for 400 mg/d, 703.0 (537–727) days for 400/200 mg/d, and 691.5 (1–747) days for placebo. The median (range) duration of therapy for the total (initial plus extended) treatment periods was 713.5 (28–1032), 49.0 (5–724), 746.5 (537–1067), and 698.0 (1–1028) days, respectively.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristicsa

| Characteristic | Bosutinib | Placebo (n=56) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 200 mg/d (n=58) | 400 mg/d (n=31) | 400/200 mg/d (n=24) | ||

| Mean (range) age, yr | 37.9 (21–50) | 41.3 (31–50) | 36.4 (18–47) | 38.5 (20–50) |

| Women, n (%) | 28 (48) | 14 (45) | 15 (63) | 35 (63) |

| Race, n (%) | ||||

| White | 53 (91) | 30 (97) | 21 (88) | 53 (95) |

| Black | 1 (2) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Asian | 3 (5) | 1 (3) | 3 (13) | 3 (5) |

| Other | 1 (2) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Median (range) TKV, ml | 1436.40 (751.55–7329.00) | 1265.95 (793.40–5688.45) | 1453.45 (803.70–2771.55) | 1392.15 (767.95–3702.00) |

| >1500 ml, n (%) | 26 (45) | 12 (39) | 12 (50) | 25 (45) |

| ≥750–1500 ml, n (%) | 32 (55) | 19 (61) | 12 (50) | 31 (55) |

| Median (range) eGFR, ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 85.86 (64.63–128.02) | 83.32 (57.46–113.54) | 95.01 (56.87–129.11) | 86.94 (53.19–130.50) |

| Median (range) duration since diagnosis, yr | 10.2 (0–28.2) | 12.2 (0.3–37.3) | 6.2 (0–31.7) | 10.2 (0.3–29.9) |

Data represent the safety population. TKV, total kidney volume; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate.

Figure 1.

Subject disposition. *Three patients were not administered study treatment: two were randomized but discontinued before treatment, and one did not receive any study treatment and was reassigned a new randomization number because of accidental unblinding. †Includes one patient with a status of “ongoing” but who discontinued before the end of the initial treatment period because the summary page from this patient’s case report form was not recorded. BOS, bosutinib; mITT, modified intent-to-treat population.

Efficacy

Annualized Rate of Kidney Enlargement

In the modified intent-to-treat (mITT) population (bosutinib 200 mg/d, n=27; 400 mg/d, n=7; 400/200 mg/d, n=21; placebo, n=33), the annualized rate of kidney enlargement (primary endpoint) was lower (66% reduction) with bosutinib 200 mg/d versus placebo (1.63% versus 4.74% per year; P=0.01; Table 2). The annualized rate of kidney enlargement was also lower with bosutinib 400/200 mg/d versus placebo (−0.20% versus 4.74%; P<0.001); this decrease was greater than with bosutinib 200 mg/d (104% versus 66%), suggesting a dose-dependent response. Changes in TKV from baseline over the 25-month study duration are shown in Supplemental Table 1; across treatment groups, these changes were generally smaller in patients with baseline TKV≥750–1500 versus >1500 ml (Supplemental Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparisons of annualized rates of kidney enlargement and eGFR decline and composite measures of disease progression

| Comparison, Reference versus Test | Annualized Rate, % | Rate Difference (95% CI) | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference | Test | ||||

| Kidney enlargement ratea | |||||

| Placebo versus BOS 200 | 4.74 | 1.63 | 3.06 (0.93 to 5.23) | 0.01 | |

| Placebo versus BOS 400 | 4.74 | 1.29 | 3.41 (−1.03 to 8.05) | 0.13 | |

| Placebo versus BOS 400/200 | 4.74 | −0.20 | 4.95 (2.65 to 7.30) | <0.001 | |

| Placebo versus pooled BOS | 4.74 | 0.84 | 3.86 (2.02 to 5.74) | <0.001 | |

| BOS 200 versus 400/200 | 1.63 | −0.20 | 1.83 (−0.50 to 4.22) | 0.12 | |

| eGFR decline ratea | |||||

| Placebo versus BOS 200 | −2.54 | −3.09 | 0.55 (−2.32 to 3.43) | 0.71 | |

| Placebo versus BOS 400 | −2.54 | −7.43 | 4.90 (−1.25 to 11.04) | 0.12 | |

| Placebo versus BOS 400/200 | −2.54 | −4.76 | 2.23 (−0.78 to 5.24) | 0.15 | |

| Placebo versus pooled BOS | −2.54 | −4.05 | 1.51 (−0.94 to 3.96) | 0.23 | |

| BOS 200 versus 400/200 | −3.09 | −4.76 | 1.67 (−1.48 to 4.83) | 0.30 | |

| Composite measures of disease progressionb | |||||

| Time to multiple occurrence of clinical progressionc | |||||

| BOS 200 versus placebo | 0.93 (0.70 to 1.23) | 0.59 | |||

| BOS 400 versus placebo | 1.16 (0.72 to 1.87) | 0.56 | |||

| BOS 400/200 versus placebo | 1.00 (0.71 to 1.42) | 0.99 | |||

| Time to earliest onset/worsening of hypertensiond | |||||

| BOS 200 versus placebo | 1.69 (0.73 to 3.93) | 0.22 | |||

| BOS 400 versus placebo | 0.76 (0.09 to 6.11) | 0.79 | |||

| BOS 400/200 versus placebo | 0.82 (0.27 to 2.50) | 0.72 | |||

95% CI, 95% confidence interval; BOS, bosutinib (dose expressed as milligrams per day).

Data represent the mITT population (bosutinib, 200 mg/d, n=27; 400 mg/d, n=7; 400/200 mg/d, n=21; placebo, n=33).

Data represent the mITT-2 population (bosutinib, 200 mg/d, n=43; 400 mg/d, n=10; 400/200 mg/d, n=24; placebo, n=45).

On the basis of the Andersen–Gill extended Cox model.

On the basis of Cox regression analysis (categoric baseline TKV covariate).

eGFR

The annualized rate of eGFR decline (mITT population) was similar for placebo versus bosutinib 200, 400, or 400/200 mg/d (−2.54 versus −3.09, −7.43, and −4.76 ml/min per 1.73 m2 per year, respectively; Table 2). eGFR declined from baseline over time for all treatment groups; there was a general trend toward dose-dependent worsening of eGFR with increasing bosutinib dose that was partially reversible during the 30-day washout after the initial treatment period. However, differences in eGFR from baseline at month 24 or 25/end of initial treatment period were not significant (Supplemental Table 1).

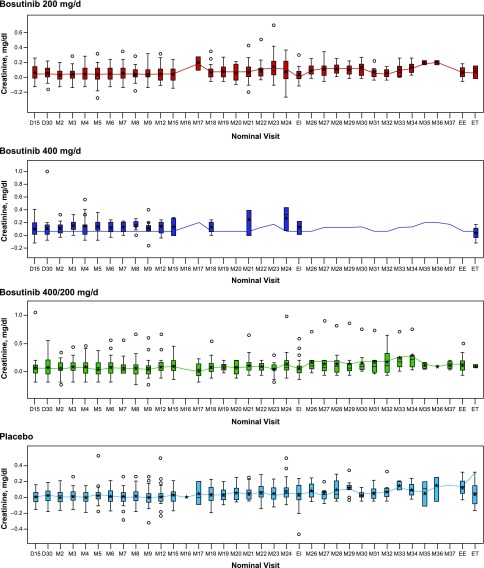

Changes in Serum Creatinine from Baseline over Time

Mean serum creatinine values were increased in all bosutinib groups at day 15; these remained stable over the 24-month initial treatment period and then returned close to baseline after a 30-day washout at the end of this period (Figure 2). Small increases in serum creatinine were also observed with bosutinib 200 and 400/200 mg/d at month 26 during the extended treatment period; these levels again returned close to baseline after a 30-day washout at the end of this period.

Figure 2.

No significant change in serum creatinine over time. Boxes represent the 25th, 50th, and 75th percentiles; whiskers represent an extension of 1.5× the interquartile range; stars represent mean value; circles represent individual values out of interquartile range. D, day; EE, end of extended treatment; EI, end of initial treatment; ET, early termination; M, month.

Composite Measures of Disease Progression

For the mITT-2 population (bosutinib, 200 mg/d, n=43; 400 mg/d, n=10; 400/200 mg/d, n=24; placebo, n=45), the hazard ratio for the multiple occurrence of four components of ADPKD progression was similar for all bosutinib treatment groups versus placebo (Table 2).

The Kaplan–Meier estimated median time to onset/worsening was not reached for individual measures of ADPKD progression in any treatment group (Supplemental Figures 1–4). The hazard ratio for worsening of hypertension was similar for all bosutinib groups versus placebo (Table 2). However, onset/worsening of hypertension (postrandomization) generally occurred later with bosutinib versus placebo (days 15, 180, 90 for bosutinib 200, 400, 200/400 mg/d, respectively, versus day 30 for placebo), as did PKD-related chronic back/flank (renal) pain (day 30 for 200 and 400 mg/d and day 270 for 400/200 mg/d versus day 15 for placebo) and hematuria (day 330 for 200 mg/d and day 180 for 400 and 400/200 mg/d versus day 45 for placebo). Treatment differences in the earliest onset/worsening of proteinuria were not apparent (day 360 for 200 mg/d and day 270 for 400/200 mg/d versus day 540 for placebo [no events observed for 400 mg/d]). For each treatment group, urine protein-to-creatinine ratio values remained constant over the 24-month initial treatment period (Supplemental Figure 5). No patients developed ESRD during the study period.

Safety

Overall, treatment-emergent AEs (TEAEs; any causality) occurred more frequently with bosutinib 400 and 400/200 mg/d versus bosutinib 200 mg/d and placebo (Table 3). TEAEs (incidence≥30% in any treatment group) were most commonly gastrointestinal, primarily diarrhea, which occurred more frequently with bosutinib versus placebo (200 mg/d, 45%; 400 mg/d, 84%; 400/200 mg/d, 75%; placebo, 20%). Liver-related TEAEs were also more common with bosutinib versus placebo; these were primarily events of increased alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and were generally of mild severity (Table 3). Increases in ALT and AST levels from baseline were greatest with bosutinib 400 mg/d; these increases were transient, returning close to baseline by the end of the initial treatment period (Supplemental Figures 6 and 7). Overall, treatment-related TEAEs followed a similar pattern (Supplemental Table 3).

Table 3.

All-cause TEAEs occurring in ≥5% of the safety population

| TEAE, n (%) | Bosutinib | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 200 mg/d (n=58) | 400 mg/d (n=31) | 400/200 mg/d (n=24) | Placebo (n=56) | Total (N=169) | ||||||

| Any Grade | Grade ≥3 | Any Grade | Grade ≥3 | Any Grade | Grade ≥3 | Any Grade | Grade ≥3 | Any Grade | Grade ≥3 | |

| Diarrhea | 26 (45) | 1 (2) | 26 (84) | 3 (10) | 18 (75) | 0 | 11 (20) | 2 (4) | 81 (48) | 6 (4) |

| Nausea | 21 (36) | 0 | 15 (48) | 0 | 13 (54) | 0 | 9 (16) | 0 | 58 (34) | 0 |

| ALT increased | 19 (33) | 4 (7) | 16 (52) | 4 (13) | 12 (50) | 2 (8) | 4 (7) | 1 (2) | 51 (30) | 11 (7) |

| AST increased | 17 (29) | 0 | 11 (36) | 4 (13) | 6 (25) | 0 | 3 (5) | 1 (2) | 37 (22) | 5 (3) |

| Nasopharyngitis | 12 (21) | 0 | 3 (10) | 0 | 8 (33) | 0 | 8 (14) | 0 | 31 (18) | 0 |

| Vomiting | 6 (10) | 0 | 11 (36) | 2 (7) | 9 (38) | 0 | 4 (7) | 0 | 30 (18) | 2 (1) |

| Headache | 9 (16) | 1 (2) | 3 (10) | 0 | 2 (8) | 0 | 12 (21) | 0 | 26 (15) | 1 (1) |

| Abdominal pain upper | 5 (9) | 0 | 7 (23) | 0 | 8 (33) | 0 | 5 (9) | 0 | 25 (15) | 0 |

| Blood CPK increased | 11 (19) | 2 (3) | 3 (10) | 0 | 6 (25) | 1 (4) | 5 (9) | 2 (4) | 25 (15) | 5 (3) |

| Hypertension | 8 (14) | 0 | 3 (10) | 1 (3) | 5 (21) | 1 (4) | 9 (16) | 2 (4) | 25 (15) | 4 (2) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 6 (10) | 1 (2) | 4 (13) | 0 | 7 (29) | 0 | 7 (13) | 0 | 24 (14) | 1 (1) |

| Abdominal pain | 4 (7) | 2 (3) | 8 (26) | 0 | 2 (8) | 0 | 7 (13) | 0 | 21 (12) | 2 (1) |

| Lipase increased | 5 (9) | 2 (3) | 7 (23) | 3 (10) | 6 (25) | 0 | 3 (5) | 1 (2) | 21 (12) | 6 (4) |

| Back pain | 9 (16) | 1 (2) | 2 (7) | 0 | 1 (4) | 0 | 8 (14) | 1 (2) | 20 (12) | 2 (1) |

| Fatigue | 4 (7) | 0 | 8 (26) | 0 | 2 (8) | 0 | 6 (11) | 0 | 20 (12) | 0 |

| Flank pain | 10 (17) | 2 (3) | 5 (16) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 (9) | 1 (2) | 20 (12) | 3 (2) |

| Urinary tract infection | 8 (14) | 1 (2) | 2 (7) | 0 | 2 (8) | 0 | 8 (14) | 0 | 20 (12) | 1 (1) |

| Anemia | 7 (12) | 0 | 4 (13) | 0 | 5 (21) | 1 (4) | 2 (4) | 0 | 18 (11) | 1 (1) |

| Dizziness | 7 (12) | 0 | 2 (7) | 0 | 4 (17) | 0 | 3 (5) | 0 | 16 (10) | 0 |

| Dyspepsia | 6 (10) | 0 | 2 (7) | 0 | 3 (13) | 0 | 3 (5) | 0 | 14 (8) | 0 |

| Cough | 2 (3) | 0 | 3 (10) | 0 | 3 (13) | 0 | 4 (7) | 0 | 12 (7) | 0 |

| Hematuria | 4 (7) | 0 | 3 (10) | 0 | 1 (4) | 0 | 4 (7) | 2 (4) | 12 (7) | 2 (1) |

| Influenza-like illness | 2 (3) | 0 | 1 (3) | 0 | 3 (13) | 0 | 6 (11) | 0 | 12 (7) | 0 |

| Amylase increased | 2 (3) | 0 | 5 (16) | 0 | 3 (13) | 0 | 1 (2) | 0 | 11 (7) | 0 |

| Arthralgia | 5 (9) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (4) | 0 | 5 (9) | 0 | 11 (7) | 0 |

| Abdominal distension | 3 (5) | 0 | 2 (7) | 0 | 2 (8) | 0 | 3 (5) | 0 | 10 (6) | 0 |

| Bronchitis | 3 (5) | 1 (2) | 2 (7) | 0 | 2 (8) | 0 | 3 (5) | 0 | 10 (6) | 1 (1) |

| Decreased appetite | 2 (3) | 0 | 4 (13) | 0 | 4 (17) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 (6) | 0 |

| Oropharyngeal pain | 5 (9) | 0 | 2 (7) | 0 | 1 (4) | 0 | 2 (4) | 0 | 10 (6) | 0 |

| Alopecia | 2 (3) | 0 | 1 (3) | 0 | 3 (13) | 0 | 3 (5) | 0 | 9 (5) | 0 |

Data for any grade and grade ≥3 all-cause TEAEs are n (%). TEAE, treatment-emergent adverse event; CPK, creatine phosphokinase.

Six patients experienced treatment-related serious AEs (increased ALT, increased AST, acute hepatitis, abnormal pancreatic enzymes, acute renal failure, and anemia); these were confined to the bosutinib groups (200 mg/d, n=3 [5%]; 400 mg/d, n=2 [7%]; 200/400 mg/d, n=1 [4%]) and all resolved. One patient receiving bosutinib 200 mg/d died on study owing to sepsis deemed not treatment related.

More discontinuations due to treatment-related AEs occurred with bosutinib 400 mg/d versus 200 mg/d (94% [n=17 of 18] versus 60% [n=9 of 15]); both rates were higher than placebo (43% [n=3 of 7]). Treatment discontinuation that occurred was most commonly the result of increased ALT (bosutinib 200 mg/d, n=6; 400 mg/d, n=5; placebo, n=1). All events resolved without sequelae except one, and the status of another was unknown (both bosutinib 400 mg/d). Permanent discontinuation due to treatment-related grade 4 AEs occurred in four patients receiving bosutinib 400 mg/d (lipase increased, n=1; ALT increased, n=2; acute hepatitis, n=1) and two receiving bosutinib 200 mg/d (ALT increased, n=1; hepatotoxicity, n=1).

Pharmacokinetics

Increases in bosutinib exposure were dose-proportional, with maximal observed concentrations of 32.6, 74.9, and 84.6 ng/ml, and area under the concentration versus time profiles from time 0 to τ (where τ = dosing interval = 24 hours) of 437, 1040, and 1149 ng×h/ml achieved for 200, 400, and 400/200 mg/d, respectively, on day 1. Plasma accumulation was approximately two-fold after 15 days of dosing.

Discussion

The results of this study demonstrate that bosutinib reduced kidney growth rate in patients with ADPKD (66% slower with bosutinib 200 mg/d versus placebo annually). Notably, the change in median kidney volume from baseline to end of treatment was approximately 100 ml smaller with bosutinib 200 mg/d versus placebo (62.7 [range, −168.7 to 1004.8] ml versus 168.1 [−147.6 to 558.9] ml). The four-component composite measure of disease progression was similar for all bosutinib doses versus placebo. Over the treatment period, there was no significant change in kidney function, as measured by eGFR, with bosutinib 200 mg/d versus placebo. Observed changes in eGFR were at least partially reversible with interruption of bosutinib treatment. TKI-induced nephrotoxicity has been observed with imatinib, dasatinib, and nilotinib in patients with CML, but the exact mechanism for this toxicity is unknown.16,17 It has been suggested that inhibition of platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) plays a role in renal injury,18 and imatinib,19 dasatinib,20 and nilotinib21 all inhibit PDGF. In contrast, bosutinib has minimal to no activity against PDGF.19,20 Additional studies are needed to assess any true nephrotoxic effects of bosutinib because, in this study and others, increased creatinine levels after TKI treatment were reversible after a washout period or a cessation of/switching to another TKI, respectively.17 One potential mechanism for the reversible serum creatinine elevation observed with TKI treatment is blockade of renal tubular secretion.22 Preclinical evidence showing TKI-induced inhibition of renal transport proteins, organic cation transporter, and multidrug and toxic compound extrusion proteins (MATE), has been reported.23 Evidence of MATE-1/2K inhibition has been demonstrated with tesavatinib in patients with ADPKD24; however, whether this phenomenon applies to bosutinib is unknown. To further understand the effects of bosutinib on renal function, additional and/or combined measures of renal function such as cystatin C may be of benefit, especially in patients with CKD.25

The fact that eGFR data were collected at only four time points (baseline and months 12, 24, and 25/end of initial treatment) may limit interpretation. Future randomized studies with longer follow-up and suitably powered to assess treatment differences in these secondary endpoints may allow evaluation of the association of bosutinib with renal function and disease progression parameters in ADPKD.

Recent studies demonstrate that TKV increases are attenuated by rigorous blood pressure control in hypertensive patients with ADPKD26 as well as by use of the vasopressin V2–receptor antagonist tolvaptan.27,28 The phase 3 Tolvaptan Efficacy and Safety in Management of Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease and Its Outcomes (TEMPO) 3:4 trial demonstrated significantly slowed kidney enlargement rate (2.8% versus 5.5% per year; P<0.001) and significantly improved secondary outcomes with tolvaptan versus placebo.28 The change in mean kidney volume from baseline to the end of 3 years of tolvaptan treatment was approximately 144 ml (50 ml/yr) smaller versus placebo. This is in keeping with the present finding of an approximately 100-ml (50-ml/yr) smaller change in median kidney volume from baseline to the end of 2 years of bosutinib 200-mg/d treatment versus placebo. A recent exploratory analysis of data from the TEMPO 3:4 trial demonstrated that increased baseline albuminuria is associated with a more rapid loss of kidney function (eGFR) and, notably, that tolvaptan decreased albuminuria compared with placebo.29 This contrasts with the apparent lack of change in proteinuria over time observed here. However, study design differences, including the larger sample size (n=1445) and longer study treatment period (36 months) in the TEMPO 3:4 trial, make comparisons difficult. Notably, contrasting with this study, patients in the TEMPO 3:4 trial were advised to drink extra water,27 which is known to suppress vasopressin levels.

A recent meta-analysis of preventive interventions for ADPKD progression, including the TEMPO 3:4 trial and 29 other studies across 11 therapeutic classes (e.g., antihypertensives, mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors, somatostatin analogs), concluded that current treatments are associated with frequent AEs and that significant unmet need remains.3 The observed safety profile of bosutinib was generally consistent with that previously observed in CML trials.30 Gastrointestinal and liver-related AEs were the most frequent toxicities; incidences of diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting appeared to be dose dependent, with frequencies being higher with bosutinib 400 and 400/200 mg/d versus bosutinib 200 mg/d and placebo. AEs and serious AEs that could cause kidney injury were carefully monitored throughout the study. Additional studies are needed to determine if gastrointestinal AEs leading to volume depletion increase risk of kidney injury. Dose reductions and continued monitoring or limited use of bosutinib may be required to mitigate the occurrence of these AEs and prevent adverse effects on the kidney. Of note, the frequency of hematologic toxicities in bosutinib and placebo groups was similar and markedly less than reported previously in the CML setting.30

ADPKD is a slowly progressive disease and patients would require long-term treatment. Similarly, patients with chronic phase CML (CP CML) require treatment over several years. Studies examining long-term (2–4 years) use of bosutinib in patients with CP CML resistant or intolerant to prior therapy indicate that bosutinib is well tolerated despite the high frequency of diarrhea.31,32 Most diarrhea events are transient and can be effectively managed with a combination of dose reductions/interruptions and/or antidiarrheal medications.31,32 Long-term treatment tolerability, evidenced by patient-reported measures of quality of life, has also been shown in patients who received up to 5 years of treatment with bosutinib.33 Quality of life was largely maintained, indicating a patient’s capacity to manage their disease over the long-term, and that the toxicity profile of bosutinib is manageable and does not compromise quality of life. Because these studies were conducted in patients with CP CML resistant or intolerant to prior therapy, the results should be interpreted cautiously and may not be applicable to patients with ADPKD. However, they demonstrate the tolerability and long-term effects of bosutinib treatment in a patient population with a chronic disease.

The bosutinib exposures observed here are consistent with those reported previously in a phase 1 trial in healthy volunteers.34 However, this study recruited only patients with mildly reduced kidney function; pharmacokinetics in patients with moderate or severe ADPKD remain to be determined. In this regard, bosutinib exposure has been shown to be increased by 60% and 35% in patients with severe and moderate renal disease, respectively, compared with patients with normal renal function.15 In conclusion, the primary endpoint of this study was met, with reduced kidney growth in the bosutinib 200 mg/d versus placebo groups. Although the study was not powered to detect treatment differences in eGFR, there was no evidence for beneficial effects of bosutinib on eGFR versus placebo over the 2-year treatment period. No new toxicities were identified relative to prior experience with bosutinib in other patient populations. The study offers evidence that Src kinase inhibitors may have the potential to retard the growth of cysts and kidney volume in ADPKD but the long-term benefit remains to be determined.

Concise Methods

Study Design and Patients

This phase 2, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study enrolled patients at 47 study sites in 17 countries (ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT01233869). Eligible patients were aged 18–50 years with a documented ADPKD diagnosis on the basis of renal ultrasound cyst criteria per Unified Criteria for Ultrasonographic Diagnosis of ADPKD35 or PKD1 or PKD2 genotype findings as documented in the medical record; centrally interpreted magnetic resonance image (MRI)–confirmed TKV≥750 ml; and eGFR≥60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (additional eligibility requirements can be found in the Supplemental Material). Patients were ineligible if they had biopsy-proven renal disease other than ADPKD or a severe acute or chronic medical condition (e.g., liver impairment).

Patients were stratified at randomization by baseline TKV≥750–1500 ml versus >1500 ml (central imaging reader) and were concurrently randomized (1:1:1) to bosutinib 200, 400 mg/d, or placebo. Dose selection was on the basis of a number of observations, including those from a phase 1 study in healthy volunteers showing that these doses result in exposures that overlap with those that elicit clinical effects in rat models of PKD (i.e., reduction in both kidney weight and levels of activated Src phosphorylation,34 Pfizer Inc, unpublished data); the treatment-emergent toxicities profile from clinical studies involving patients with advanced malignant solid tumors36 and with CML37; and the volume of distribution of bosutinib.15

The study was approximately 50 months in duration. During the first 24 months patients were recruited to achieve the necessary sample size (n=140). All patients underwent a 4-week screening period. After the screening period, patients began the initial treatment period and received bosutinib or placebo with food once daily in the morning. Treatment continued for up to 24 months or until ESRD onset requiring dialysis for ≥56 days. After completion of the initial treatment period, patients underwent a post-treatment assessment at month 25 and could then continue their assigned treatment for up to approximately 13 months in an extended treatment period.

An interim review of ongoing safety data by an independent external data monitoring committee approximately 1 year after the last patient’s enrollment noted slightly increased serum creatinine levels at month 15 and more frequent AEs with bosutinib 400 mg/d versus placebo and bosutinib 200 mg/d (notably, gastrointestinal AEs leading to discontinuation or dose reduction). The external data monitoring committee recommended a protocol amendment (October 7, 2013) to reduce bosutinib dose from 400 to 200 mg/d. Patients were then divided between the original bosutinib 400-, 200-mg/d, and placebo groups and an additional mixed 400/200-mg/d group consisting of all patients originally randomized to 400 mg/d but reducing to 200 mg/d.

The protocol was approved by each site’s ethics committee; informed consent was obtained in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The authors vouch for data accuracy and adherence to the protocol.

Endpoints

The primary efficacy endpoint was the annualized rate of kidney enlargement versus placebo. Rationale for using TKV as a surrogate for ADPKD progression was provided by previous studies showing a correlation between TKV, renal cyst volume, and clinical markers of ADPKD progression (eGFR decline, hypertension, hematuria, and albuminuria).38–40 TKV was determined by central MRI assessment. Key secondary endpoints included eGFR decline rate versus placebo (using the CKD Epidemiology Collaboration equation41) and time to first occurrence (or worsening) of clinical measures of disease progression (back and/or flank pain, hypertension, hematuria, proteinuria, or ESRD requiring dialysis for ≥56 days). A four-component composite disease progression endpoint was also assessed, including onset/worsening of hypertension, renal pain, proteinuria, and renal function (defined as a 25% change from baseline in reciprocal serum creatinine levels). Efficacy analyses for TKV and eGFR were performed after 24 months of treatment. Safety was assessed from TEAEs, laboratory tests, liver function testing (including total protein, albumin, total bilirubin, direct bilirubin, lactate dehydrogenase, alkaline phosphatase, AST, ALT), physical examinations and vital signs, 12-lead electrocardiograms, echocardiogram, and multigated acquisition scan. All safety analyses were performed using the initial and post-treatment periods (frequency of assessments can be found in the Supplemental Material). Pharmacokinetics were also assessed from blood samples collected predose (0 hour) and postdose on days 1 (1, 3, 5, and 24 hours) and 15 (1–4, 6, 8, and 24 hours).

Statistical Analysis

The primary endpoint sample size was derived using a group sequential design with one interim analysis. On the basis of previously reported annual rates of TKV increase (5.27% in a study by the Consortium for Radiologic Imaging Studies of Polycystic Kidney Disease38; 5.36% in a study at the University Hospital of Zürich39), it was assumed that the increase in TKV over a 24-month treatment period would approach 11% in the placebo group. With an SD of 8% for growth rate and one-sided 0.05 significance level, a sample size of 32 patients/cohort was required for 80% power to detect a clinically meaningful reduction (50%) in the annualized rate of kidney enlargement over 24 months in favor of bosutinib. The study was not powered for eGFR decline rate or other secondary endpoints.

For the primary analysis, log-transformed TKV data were fit to a longitudinal regression model. Treatment-by-time interaction was evaluated using a global F-test (type I error 0.05); treatment effect on annualized rate of kidney enlargement over time was evaluated using the Wald t test. Efficacy analyses were on the basis of the mITT population (all patients randomized receiving ≥2 weeks of treatment and ≥1 postrandomization follow-up MRI assessment preceded by ≥1-month washout) or the mITT-2 population (identical to the mITT but without the ≥1-month washout), which are consistent with a per-protocol analysis. Missing efficacy data were imputed using a longitudinal linear mixed model. Time to first event occurrence corresponded to the duration from randomization to first occurrence of that event in a treatment group. Safety was assessed in all patients receiving ≥1 study dose.

Disclosures

V.T. was a paid consultant of Pfizer Inc at the time of this study; K.C., Y.P., I.B., and A.S. report no disclosures; M.S., R.L., J.H.W., and S.A. are employees of Pfizer Inc. M.L. was an employee of Pfizer Inc at the time of this study.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the contributions of Dr. Daniel Levy (Pfizer Inc, Collegeville, PA) for critically reviewing this manuscript and Fang Yuan (Pfizer Inc China, Shanghai City, China) for her expert programming assistance.

This study was sponsored by Pfizer Inc. Editorial support for this manuscript was provided by Simon J. Slater, PhD, of Complete Healthcare Communications, LLC, and was funded by Pfizer Inc.

Content from this manuscript was presented at the American Society of Nephrology Kidney Week 2015, November 5–8, in San Diego, CA.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2016111232/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Torres VE, Harris PC, Pirson Y: Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Lancet 369: 1287–1301, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Santoro D, Pellicanò V, Visconti L, Trifirò G, Cernaro V, Buemi M: Monoclonal antibodies for renal diseases: Current concepts and ongoing treatments. Expert Opin Biol Ther 15: 1119–1143, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bolignano D, Palmer SC, Ruospo M, Zoccali C, Craig JC, Strippoli GF: Interventions for preventing the progression of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 7: CD010294, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huan Y, van Adelsberg J: Polycystin-1, the PKD1 gene product, is in a complex containing E-cadherin and the catenins. J Clin Invest 104: 1459–1468, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Silberberg M, Charron AJ, Bacallao R, Wandinger-Ness A: Mispolarization of desmosomal proteins and altered intercellular adhesion in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 288: F1153–F1163, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilson PD, Geng L, Li X, Burrow CR: The PKD1 gene product, “polycystin-1,” is a tyrosine-phosphorylated protein that colocalizes with alpha2beta1-integrin in focal clusters in adherent renal epithelia. Lab Invest 79: 1311–1323, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shibazaki S, Yu Z, Nishio S, Tian X, Thomson RB, Mitobe M, Louvi A, Velazquez H, Ishibe S, Cantley LG, Igarashi P, Somlo S: Cyst formation and activation of the extracellular regulated kinase pathway after kidney specific inactivation of Pkd1. Hum Mol Genet 17: 1505–1516, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Du J, Wilson PD: Abnormal polarization of EGF receptors and autocrine stimulation of cyst epithelial growth in human ADPKD. Am J Physiol 269: C487–C495, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilson PD, Hreniuk D, Gabow PA: Abnormal extracellular matrix and excessive growth of human adult polycystic kidney disease epithelia. J Cell Physiol 150: 360–369, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wiener JR, Nakano K, Kruzelock RP, Bucana CD, Bast RC Jr, Gallick GE: Decreased Src tyrosine kinase activity inhibits malignant human ovarian cancer tumor growth in a nude mouse model. Clin Cancer Res 5: 2164–2170, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Verbeek BS, Vroom TM, Adriaansen-Slot SS, Ottenhoff-Kalff AE, Geertzema JG, Hennipman A, Rijksen G: c-Src protein expression is increased in human breast cancer. An immunohistochemical and biochemical analysis. J Pathol 180: 383–388, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsao AS, He D, Saigal B, Liu S, Lee JJ, Bakkannagari S, Ordonez NG, Hong WK, Wistuba I, Johnson FM: Inhibition of c-Src expression and activation in malignant pleural mesothelioma tissues leads to apoptosis, cell cycle arrest, and decreased migration and invasion. Mol Cancer Ther 6: 1962–1972, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sweeney WE Jr, von Vigier RO, Frost P, Avner ED: Src inhibition ameliorates polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 19: 1331–1341, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elliott J, Zheleznova NN, Wilson PD: c-Src inactivation reduces renal epithelial cell-matrix adhesion, proliferation, and cyst formation. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 301: C522–C529, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.BOSULIF (bosutinib). Full Prescribing Information, Pfizer Labs, New York, NY, 2015

- 16.Yilmaz M, Lahoti A, O’Brien S, Nogueras-González GM, Burger J, Ferrajoli A, Borthakur G, Ravandi F, Pierce S, Jabbour E, Kantarjian H, Cortes JE: Estimated glomerular filtration rate changes in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia treated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Cancer 121: 3894–3904, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gafter-Gvili A, Ram R, Gafter U, Shpilberg O, Raanani P: Renal failure associated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors--case report and review of the literature. Leuk Res 34: 123–127, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakagawa T, Sasahara M, Haneda M, Kataoka H, Nakagawa H, Yagi M, Kikkawa R, Hazama F: Role of PDGF B-chain and PDGF receptors in rat tubular regeneration after acute injury. Am J Pathol 155: 1689–1699, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Puttini M, Coluccia AM, Boschelli F, Cleris L, Marchesi E, Donella-Deana A, Ahmed S, Redaelli S, Piazza R, Magistroni V, Andreoni F, Scapozza L, Formelli F, Gambacorti-Passerini C: In vitro and in vivo activity of SKI-606, a novel Src-Abl inhibitor, against imatinib-resistant Bcr-Abl+ neoplastic cells. Cancer Res 66: 11314–11322, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Remsing Rix LL, Rix U, Colinge J, Hantschel O, Bennett KL, Stranzl T, Müller A, Baumgartner C, Valent P, Augustin M, Till JH, Superti-Furga G: Global target profile of the kinase inhibitor bosutinib in primary chronic myeloid leukemia cells. Leukemia 23: 477–485, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rix U, Colinge J, Blatt K, Gridling M, Remsing Rix LL, Parapatics K, Cerny-Reiterer S, Burkard TR, Jäger U, Melo JV, Bennett KL, Valent P, Superti-Furga G: A target-disease network model of second-generation BCR-ABL inhibitor action in Ph+ ALL. PLoS One 8: e77155, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vidal-Petiot E, Rea D, Serrano F, Stehlé T, Gardin C, Rousselot P, Peraldi MN, Flamant M: Imatinib increases serum creatinine by inhibiting its tubular secretion in a reversible fashion in chronic myeloid leukemia. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk 16: 169–174, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Minematsu T, Giacomini KM: Interactions of tyrosine kinase inhibitors with organic cation transporters and multidrug and toxic compound extrusion proteins. Mol Cancer Ther 10: 531–539, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tonra J, Isringhausen C, Hashizume K, Patel J, Ryan J, Schueller O, Eiznhamer D, Berger M, Rastogi A: Implications of transporter studies on development of tesevatinib for polycystic kidney disease: multidrug and toxin extrusion (MATE)1/2-K inhibition [Abstract]. J Am Soc Nephrol 27: 770A, 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stevens LA, Coresh J, Schmid CH, Feldman HI, Froissart M, Kusek J, Rossert J, Van Lente F, Bruce RD 3rd, Zhang YL, Greene T, Levey AS: Estimating GFR using serum cystatin C alone and in combination with serum creatinine: A pooled analysis of 3,418 individuals with CKD. Am J Kidney Dis 51: 395–406, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schrier RW, Abebe KZ, Perrone RD, Torres VE, Braun WE, Steinman TI, Winklhofer FT, Brosnahan G, Czarnecki PG, Hogan MC, Miskulin DC, Rahbari-Oskoui FF, Grantham JJ, Harris PC, Flessner MF, Bae KT, Moore CG, Chapman AB; HALT-PKD Trial Investigators : Blood pressure in early autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. N Engl J Med 371: 2255–2266, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Irazabal MV, Torres VE, Hogan MC, Glockner J, King BF, Ofstie TG, Krasa HB, Ouyang J, Czerwiec FS: Short-term effects of tolvaptan on renal function and volume in patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Kidney Int 80: 295–301, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Torres VE, Chapman AB, Devuyst O, Gansevoort RT, Grantham JJ, Higashihara E, Perrone RD, Krasa HB, Ouyang J, Czerwiec FS; TEMPO 3:4 Trial Investigators : Tolvaptan in patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. N Engl J Med 367: 2407–2418, 2012. 23121377 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gansevoort RT, Meijer E, Chapman AB, Czerwiec FS, Devuyst O, Grantham JJ, Higashihara E, Krasa HB, Ouyang J, Perrone RD, Torres VE, TEMPO 3:4 Investigators: Albuminuria and tolvaptan in autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease: Results of the TEMPO 3:4 Trial. Nephrol Dial Transplant 31: 1887–1894, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gambacorti-Passerini C, Cortes JE, Lipton JH, Dmoszynska A, Wong RS, Rossiev V, Pavlov D, Gogat Marchant K, Duvillié L, Khattry N, Kantarjian HM, Brümmendorf TH: Safety of bosutinib versus imatinib in the phase 3 BELA trial in newly diagnosed chronic phase chronic myeloid leukemia. Am J Hematol 89: 947–953, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brümmendorf TH, Cortes JE, Khoury HJ, Kantarjian HM, Kim DW, Schafhausen P, Conlan MG, Shapiro M, Turnbull K, Leip E, Gambacorti-Passerini C, Lipton JH: Factors influencing long-term efficacy and tolerability of bosutinib in chronic phase chronic myeloid leukaemia resistant or intolerant to imatinib. Br J Haematol 172: 97–110, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gambacorti-Passerini C, Brümmendorf TH, Kim DW, Turkina AG, Masszi T, Assouline S, Durrant S, Kantarjian HM, Khoury HJ, Zaritskey A, Shen ZX, Jin J, Vellenga E, Pasquini R, Mathews V, Cervantes F, Besson N, Turnbull K, Leip E, Kelly V, Cortes JE: Bosutinib efficacy and safety in chronic phase chronic myeloid leukemia after imatinib resistance or intolerance: Minimum 24-month follow-up. Am J Hematol 89: 732–742, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cortes JE, Mamolo C, Su Y, Reisman A, Shapiro M, Lipton JH: Patient-reported outcomes from an open-label safety and efficacy study of bosutinib in Philadelphia chromosome–positive chronic myeloid leukemia resistant or intolerant to prior therapy. Haematologia (Budap) 101: 1–881, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abbas R, Hug BA, Leister C, Gaaloul ME, Chalon S, Sonnichsen D: A phase I ascending single-dose study of the safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics of bosutinib (SKI-606) in healthy adult subjects. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 69: 221–227, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pei Y, Obaji J, Dupuis A, Paterson AD, Magistroni R, Dicks E, Parfrey P, Cramer B, Coto E, Torra R, San Millan JL, Gibson R, Breuning M, Peters D, Ravine D: Unified criteria for ultrasonographic diagnosis of ADPKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 205–212, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Daud AI, Krishnamurthi SS, Saleh MN, Gitlitz BJ, Borad MJ, Gold PJ, Chiorean EG, Springett GM, Abbas R, Agarwal S, Bardy-Bouxin N, Hsyu PH, Leip E, Turnbull K, Zacharchuk C, Messersmith WA: Phase I study of bosutinib, a src/abl tyrosine kinase inhibitor, administered to patients with advanced solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res 18: 1092–1100, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cortes JE, Kantarjian HM, Brümmendorf TH, Kim DW, Turkina AG, Shen ZX, Pasquini R, Khoury HJ, Arkin S, Volkert A, Besson N, Abbas R, Wang J, Leip E, Gambacorti-Passerini C: Safety and efficacy of bosutinib (SKI-606) in chronic phase Philadelphia chromosome-positive chronic myeloid leukemia patients with resistance or intolerance to imatinib. Blood 118: 4567–4576, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grantham JJ, Torres VE, Chapman AB, Guay-Woodford LM, Bae KT, King BF Jr, Wetzel LH, Baumgarten DA, Kenney PJ, Harris PC, Klahr S, Bennett WM, Hirschman GN, Meyers CM, Zhang X, Zhu F, Miller JP; CRISP Investigators : Volume progression in polycystic kidney disease. N Engl J Med 354: 2122–2130, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kistler AD, Poster D, Krauer F, Weishaupt D, Raina S, Senn O, Binet I, Spanaus K, Wüthrich RP, Serra AL: Increases in kidney volume in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease can be detected within 6 months. Kidney Int 75: 235–241, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chapman AB, Bost JE, Torres VE, Guay-Woodford L, Bae KT, Landsittel D, Li J, King BF, Martin D, Wetzel LH, Lockhart ME, Harris PC, Moxey-Mims M, Flessner M, Bennett WM, Grantham JJ: Kidney volume and functional outcomes in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 7: 479–486, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF 3rd, Feldman HI, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Greene T, Coresh J; CKD-EPI (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration) : A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 150: 604–612, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.