Abstract

Objective:

The purpose of the current study was to compare the renoprotective effects of continuous infusion of dexmedetomidine and dopamine in high-risk renal patients undergoing cardiac surgery.

Design:

A double-blind randomized study.

Setting:

Cardiac Centers.

Patients:

One hundred and fifty patients with baseline serum creatinine level ≥1.4 mg/dl were scheduled for cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass.

Intervention:

The patients were classified into two groups (each = 75): Group Dex – the patients received a continuous infusion of dexmedetomidine 0.4 μg/kg/h without loading dose during the procedure and the first 24 postoperative hours and Group Dopa – the patients received a continuous infusion of dopamine 3 μg/kg/min during the procedure and the first 24 postoperative hours.

Measurements:

The monitors included serum creatinine, creatinine clearance, blood urea nitrogen, and urine output.

Main Results:

The creatinine levels and blood urea nitrogen decreased at days 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 in Dex group and increased in patients of Dopa group (P < 0.05). The creatinine clearance increased at days 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 in Dex group and decreased in patients of Dopa group (P < 0.05). The amount of urine output was too much higher in the Dex group than the Dopa group (P < 0.05).

Conclusions:

The continuous infusion of dexmedetomidine during cardiac surgery has a renoprotective effect and decreased the deterioration in the renal function in high-risk renal patients compared to the continuous infusion of dopamine.

Keywords: Blood urea nitrogen, creatinine clearance, dexmedetomidine, dopamine, renal dysfunction, serum creatinine, urine output

Introduction

The incidence of acute renal failure is 5%–30% of patients undergoing cardiac surgery, and the postoperative renal dysfunction is associated with a high incidence of complicated clinical course.[1,2,3,4,5]

The risk factors include patients with impaired left ventricular function, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, generalized atherosclerosis, preoperative kidney dysfunction, advanced age, or prolonged cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB).[6,7,8]

The pathophysiology of acute renal failure in cardiac surgery includes many factors such as hemodynamic disturbance, especially intraoperative hypoperfusion of the kidney, effects of nephrotoxic drugs, the results of the systemic inflammatory reaction induced by CPB, and the interactions of blood components and artificial membranes.[9,10] During CPB, the release of vasoconstrictors, such as catecholamines, vasopressin, or thromboxane, is enhanced, and the renin–angiotensin system is activated; therefore, the renal perfusion is compromised.[11] Moreover, CPB also induces tubular damage, as suggested by the persistence of microalbuminuria up to the 6th day after cardiac surgery.[12]

Early prevention of acute kidney injury is very important to improve the outcome of cardiac surgery with CPB. Recent studies have focused on the preventive strategies, which could be used for the high-risk patients for acute renal failure.[13] The use of low-dose dopamine infusion has been used for renal protection in high-risk renal patients during cardiac surgery,[14] as results of the ability to induce receptor-mediated renal artery vasodilation,[15] increases renal perfusion, decreases renal metabolism, and results in dieresis.[16]

Dexmedetomidine is a highly selective α2-adrenoceptor agonist and it has a positive effect on renal function. It decreases the norepinephrine level in the blood and thus it induces renal artery vasodilatation and increases renal blood flow and urine output.[17,18] Furthermore, it decreases the secretion of vasopressin and increases the release of atrial natriuretic peptide resulting in natriuresis.[19]

The purpose of the current study was to compare the renoprotective effects of continuous infusion of dexmedetomidine and dopamine in high-risk renal patients undergoing cardiac surgery.

Methods

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the incidence of acute renal failure diagnosed by serum creatinine level, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine clearance, and the amount of urine output.

The secondary outcome was the safety of the study medications, which was assessed by the occurrence of any adverse events.

Sample size calculation

Power analysis was performed using the Chi-square test for independent samples on the incidence of acute renal failure because it was the main outcome variable in the present study. A pilot study was done before starting this study because there are no available data in the literature for the comparison of continuous infusion of dexmedetomidine and dopamine in high-risk renal patients undergoing cardiac surgery. The results of the pilot study showed that the incidence of acute renal injury was of 15% in dexmedetomidine group and 35% in dopamine group. Taking power 0.8, alpha error 0.05, and beta 0.2, a minimum sample size of 72 patients was calculated for each group. A total of patients in each group 75 were included to compensate for possible dropouts.

Patients

After obtaining informed consent and approval of local ethics, a double-blind randomized study included 150 high-risk renal patients undergoing cardiac surgery using CPB (2010–2017) with preoperative plasma creatinine values ≥1.4 mg/dL and scheduled for elective coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery or valvular surgery with CPB. Exclusion criteria included patients with emergent CABG, cardiac transplantation, known allergy to study medication, acute renal failure, chronic renal replacement therapy, prior renal transplantation, or aortic aneurysm surgery. The patients were randomly allocated (using simple randomization through a process of coin-tossing) into two equal groups (n = 75 each) and the study medication was prepared in 50 ml syringe by nursing staff and given to the anesthetist blindly:

Group Dex (dexmedetomidine group): The patients received after induction a continuous infusion of dexmedetomidine 0.4 μg/kg/h without loading dose during the procedure and the first 24 postoperative hours

Group Dopa (dopamine group): The patients received after induction a continuous infusion of dopamine 3 μg/kg/min during the procedure and the first 24 postoperative hours.

Anesthetic technique

On arrival to the operating room, intravenous midazolam premedication (0.03–0.1 mg/kg) was administered 10 min before induction of anesthesia. A radial arterial cannula and central venous line were inserted before operation to enable continuous hemodynamic monitoring, and a pulmonary artery catheter was inserted after induction. Induction was done by fentanyl (3–5 μg/kg), etomidate (0.3 mg/kg), and rocuronium (0.6 mg/kg). After tracheal intubation, the lungs were mechanically ventilated with an oxygen–air mixture (50%–50%). The urinary bladder catheter and probes for the measurement of nasopharyngeal and bladder temperature were also inserted after induction of anesthesia. Anesthesia was maintained with sevoflurane (1%–3%), fentanyl infusion (1–3 μg/kg/h), and cisatracurium infusion (1–2 μg/kg/min). CPB used centrifugal pumps with 1–1.5 L prime of ringer lactate, in addition to antibiotics, Solu-Medrol, and mannitol. Both antegrade and retrograde blood cardioplegia were used. All patients received 4 mg/kg of heparin before bypass, aiming to provide an activated clotting time (ACT) >480 s. CPB was established with the cannulation of the right atrium and the ascending aorta. During the CPB, the anesthesia was maintained by propofol infusion (1–3 mg/kg/h). Cooling was passive to around 34°C or active to 22°C. After bypass, heparin was reversed with protamine which was titrated to achieve an ACT <140 s. After surgery, all patients were admitted to the postoperative cardiac surgical intensive care unit with full hemodynamic monitoring and managed according to the standard protocol. All patients were continuously monitored, including electrocardiography, arterial blood pressure, arterial blood gases, and pulmonary artery catheter for monitoring the hemodynamic variables. Acute renal failure was diagnosed according to RIFLE criteria.[20]

Patients monitoring

For all patients, the following variables were closely monitored: the heart rate, mean arterial pressure, central venous pressure, mean pulmonary artery pressure, pulmonary artery wedge pressure, cardiac index, serum creatinine, creatinine clearance, blood urea nitrogen urine output, arterial oxygen saturation, and arterial blood gases. Furthermore, the amount of blood loss, transfused packed RBC, and fluids were recorded.

The statistical paragraph in material and methods

Data were statistically described in terms of mean ± standard deviation or frequencies (number of cases) and percentages when appropriate. Comparison of numerical variables between the study groups was done using the Student's t-test for independent samples. Within-group comparison of numerical variables was done using paired t-test. For comparing categorical data, Chi-square test was performed. Fisher's exact test was used instead when the expected frequency is <5. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical calculations were done using computer programs Statistical Package for the Social Science SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA Version 15 for Microsoft Windows.

Results

Table 1 shows no significant differences regarding the demographic data, comorbidities, preoperative medications, the American Society of Anesthesiologists’ physical status score, and the surgical procedures (P > 0.05).

Table 1.

Preoperative data of patients

| Variable | Group Dex (n=75) | Group Dopa (n=75) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 53.54±10.25 | 52.62±9.70 | 0.573 |

| Weight (kg) | 84.20±11.15 | 85.58±10.44 | 0.435 |

| Gender (male:female) | 40:35 | 36:39 | 0.513 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 48 | 42 | 0.317 |

| Hypertension | 39 | 43 | 0.511 |

| Ischemic heart diseases | 58 | 61 | 0.545 |

| Ejection fraction (%) | 44.64±4.32 | 45.36±3.85 | 0.283 |

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors | 43 | 38 | 0.412 |

| Beta-blockers | 58 | 54 | 0.452 |

| Calcium channels-blockers | 36 | 42 | 0.326 |

| Aspirin | 58 | 61 | 0.545 |

| Statins | 39 | 31 | 0.190 |

| Stroke | 4 | 2 | 0.404 |

| Smoking | |||

| Current smokers | 29 | 33 | 0.983 |

| Ex-smokers | 34 | 26 | 0.182 |

| ASA | |||

| II | 10 | 13 | 0.496 |

| III | 45 | 40 | 0.410 |

| IV | 20 | 22 | 0.716 |

| Euroscore (%) | 15.65±4.75 | 14.70±6.68 | 0.317 |

| Body surface area (m2) | 1.74±0.18 | 1.75±0.16 | 0.719 |

| CABG | 41 | 39 | 0.743 |

| Valvular surgery | 17 | 14 | 0.545 |

| CABG + valvular surgery | 17 | 22 | 0.352 |

Data are presented as mean±SD, n (%). ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists, CABG: Coronary artery bypasses grafting, SD: Standard deviation, Group Dex: Dexmedetomidine group, Group Dopa: Dopamine group

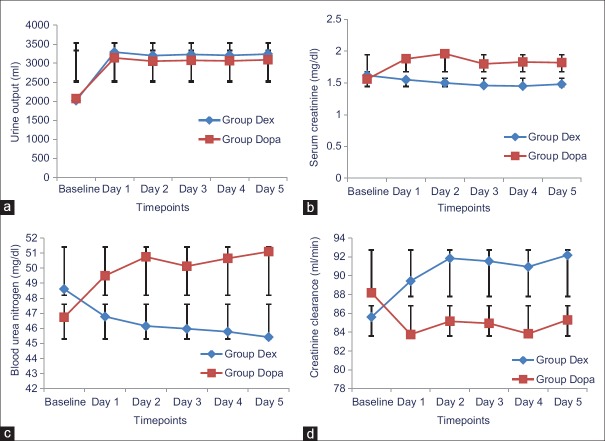

Table 2 shows the changes in the urine output, serum creatinine levels, and creatinine clearance of patients. There is no significant difference in the preoperative urine output between the two groups (P > 0.05), but the urine output increased significantly after the administration of the study medications in the patients of the two groups, but the increase was more in patients of Dex group than the Dopa group (P < 0.05) [Figure 1a]. There was no significant difference in the preoperative serum creatinine levels and blood urea nitrogen between the two groups (P > 0.05), but the levels decreased after administration of the study medications in patients of Dex group and increased in the patients of Dopa group and the difference between the two groups was statistically significant (P < 0.05) [Figure 1b and c]. There is no significant difference in the preoperative creatinine clearance between the two groups (P > 0.05), but the creatinine clearance increased after administration of the study medications in patients of Dex group and decreased in patients of Dopa group and the difference between the two groups was statistically significant (P < 0.05) [Figure 1d].

Table 2.

Urine output, serum creatinine levels, blood urea nitrogen, and creatinine clearance of patients

| Variable | Group Dex (n=75) | Group Dopa (n=75) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Urine output (mL) | |||

| Baseline | 2018.54±255.30 | 2070.41±280.27 | 0.238 |

| Day 1 | 3290.68±410.40 | 3140.35±390.73 | 0.023* |

| Day 2 | 3200.35±350.74 | 3053.63±360.48 | 0.012* |

| Day 3 | 3230.75±358.16 | 3075.63±382.25 | 0.011* |

| Day 4 | 3208.68±358.16 | 3062.95±373.60 | 0.015* |

| Day 5 | 3240.23±360.45 | 3090.50±380.58 | 0.014* |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | |||

| Baseline | 1.62±0.23 | 1.56±0.21 | 0.097 |

| Day 1 | 1.55±0.78 | 1.88±0.89† | 0.017* |

| Day 2 | 1.50±0.82† | 1.96±0.94† | 0.002* |

| Day 3 | 1.46±0.80† | 1.80±0.85† | 0.012* |

| Day 4 | 1.45±0.81† | 1.83±0.89† | 0.007* |

| Day 5 | 1.48±0.83† | 1.82±0.89† | 0.016* |

| Blood urea nitrogen (mg/dL) | |||

| Baseline | 48.61±7.44 | 46.74±6.89 | 0.112 |

| Day 1 | 46.78±6.20 | 49.50±8.17 | 0.023* |

| Day 2 | 46.15±8.73 | 50.75±11.84† | 0.007* |

| Day 3 | 45.97±8.57 | 50.13±9.45† | 0.005* |

| Day 4 | 45.78±8.45 | 50.65±10.50† | 0.002* |

| Day 5 | 45.42±9.24 | 51.10±12.15† | 0.002* |

| Creatinine clearance (mL/min) | |||

| Baseline | 85.60±15.48 | 88.18±14.32 | 0.291 |

| Day 1 | 89.43±15.19 | 83.75±18.48† | 0.041* |

| Day 2 | 91.85±15.72† | 85.15±17.10 | 0.013* |

| Day 3 | 91.54±14.86† | 84.94±16.77† | 0.011* |

| Day 4 | 90.94±16.33† | 83.83±17.60† | 0.011* |

| Day 5 | 92.18±15.40† | 85.30±17.62 | 0.012* |

Data are presented as mean±SD. *P<0.05 significant comparison between the two groups, †P<0.05 significant compared to the preoperative reading within the same group. Baseline: Preoperative values, Day 1: First postoperative day, Day 2: Second postoperative day, Day 3: Third postoperative day, Day 4: Fourth postoperative day, Day 5: Fifth postoperative day, SD: Standard deviation, Group Dex: Dexmedetomidine group, Group Dopa: Dopamine group

Figure 1.

(a) Urine output of patients; (b) Serum creatinine of patients; (c) Blood urea nitrogen of patients; (d) Creatinine clearance of patients. Group Dex: Dexmedetomidine group, Group Dopa: Dopamine group, Baseline: Preoperative values, Day 1: First postoperative day, Day 2: Second postoperative day, Day 3: Third postoperative day, Day 4: Fourth postoperative day, Day 5: Fifth postoperative day

Table 3 shows the changes in the heart rate, mean arterial blood pressure, and central venous pressure of patients. There was no significant difference in the preoperative heart rate between the two groups (P > 0.05). The heart rate decreased during the surgery and 1st and 2nd days in the patients of Dex group and increased in the patients of Dopa group and the difference between the two groups was statistically significant (P < 0.05). There are no significant differences in the heart rate through the 3rd, 4th, and 5th days between the two groups (P > 0.05). There are no significant differences in the mean arterial blood pressure and central venous pressure through the study between the two groups (P > 0.05).

Table 3.

Heart rate of patients, mean arterial blood pressure, and central venous pressure of patients

| Variable | Group Dex (n=75) | Group Dopa (n=75) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heart rate (bpm) | |||

| T0 | 78.49±10.43 | 76.93±9.22 | 0.333 |

| T1 | 74.46±10.55† | 78.57±11.22 | 0.022* |

| T2 | 73.50±13.29† | 79.42±15.87 | 0.014* |

| T3 | 74.21±12.67† | 79.18±15.38† | 0.032* |

| T4 | 76.21±10.46 | 80.18±12.80† | 0.039* |

| T5 | 78.15±12.70 | 82.30±13.62† | 0.055 |

| T6 | 77.57±12.70 | 81.24±14.90† | 0.106 |

| T7 | 78.75±13.50 | 83.10±15.61† | 0.070 |

| Mean arterial blood pressure (mmHg) | |||

| T0 | 102.15±15.41 | 105.10±13.50 | 0.214 |

| T1 | 99.80±14.35 | 104.33±15.40 | 0.273 |

| T2 | 97.75±11.80 | 99.68±12.16 | 0.325 |

| T3 | 95.43±12.60 | 96.85±14.57 | 0.524 |

| T4 | 98.90±13.46 | 101.37±15.70 | 0.302 |

| T5 | 103.52±12.30 | 102.37±13.47 | 0.585 |

| T6 | 105.10±9.75 | 105.53±11.28 | 0.803 |

| T7 | 107.47±11.76 | 104.53±10.44 | 0.107 |

| Central venous pressure (mmHg) | |||

| T0 | 10.95±1.68 | 11.35±1.75 | 0.155 |

| T1 | 12.66±1.73 | 12.35±1.65 | 0.263 |

| T2 | 13.16±1.25 | 12.89±1.46 | 0.225 |

| T3 | 12.65±1.80 | 13.00±1.32 | 0.176 |

| T4 | 13.22±1.50 | 13.37±1.28 | 0.511 |

| T5 | 13.12±1.64 | 13.50±1.25 | 0.112 |

| T6 | 12.90±1.74 | 13.38±1.40 | 0.064 |

| T7 | 12.57±1.80 | 12.70±1.55 | 0.636 |

Data are presented as mean±SD. *P<0.05 significant comparison between the two groups, †P<0.05 significant compared to the preoperative reading within the same group. T0: Baseline reading, T1: Reading before cardiopulmonary bypass, T2: Reading after cardiopulmonary bypass, T3: Reading first postoperative day, T4: Reading second postoperative day, T5: Reading third postoperative day, T6: Reading fourth postoperative day, T7: Reading fifth postoperative day, SD: Standard deviation, Group Dex: Dexmedetomidine group, Group Dopa: Dopamine group

There was no significant difference in the cardiac index, mean pulmonary arterial blood pressure, and pulmonary artery wedge pressure through the study between the two groups (P > 0.05) [Table 4].

Table 4.

Cardiac index, mean pulmonary arterial blood pressure, and pulmonary artery wedge pressure

| Variable | Group Dex (n=75) | Group Dopa (n=75) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiac index (L/min/m2) | |||

| T0 | 2.50±0.30 | 2.44±0.35 | 0.261 |

| T1 | 2.42±0.28 | 2.48±0.37 | 0.264 |

| T2 | 2.55±0.24 | 2.50±0.35 | 0.309 |

| T3 | 2.62±0.26 | 2.55±0.29 | 0.121 |

| T4 | 2.70±0.20 | 2.66±0.23 | 0.257 |

| T5 | 2.63±0.22 | 2.68±0.25 | 0.195 |

| T6 | 2.60±0.31 | 2.63±0.28 | 0.534 |

| T7 | 2.64±0.26 | 2.58±0.29 | 0.184 |

| Mean pulmonary arterial blood pressure (mmHg) | |||

| T0 | 21.72±2.80 | 22.10±2.40 | 0.373 |

| T1 | 20.55±2.90 | 21.23±2.60 | 0.132 |

| T2 | 19.90±1.71 | 20.40±2.80 | 0.189 |

| T3 | 23.16±2.42 | 22.65±2.21 | 0.178 |

| T4 | 21.71±2.32 | 22.25±2.38 | 0.161 |

| T5 | 22.66±3.15 | 21.87±2.93 | 0.113 |

| T6 | 22.85±2.40 | 23.27±2.68 | 0.313 |

| T7 | 20.78±2.18 | 21.36±2.45 | 0.127 |

| Pulmonary artery wedge pressure (mmHg) | |||

| T0 | 12.55±2.17 | 13.10±2.43 | 0.145 |

| T1 | 14.60±3.42 | 13.75±3.80 | 0.152 |

| T2 | 15.35±3.48 | 14.87±3.65 | 0.411 |

| T3 | 15.65±3.22 | 15.15±3.45 | 0.360 |

| T4 | 14.90±3.46 | 15.28±3.72 | 0.518 |

| T5 | 14.72±3.20 | 15.00±3.51 | 0.610 |

| T6 | 14.29±3.37 | 14.63±3.58 | 0.550 |

| T7 | 13.80±3.42 | 14.18±3.50 | 0.502 |

Data are presented as mean±SD. T0: Baseline reading; T1: Reading before cardiopulmonary bypass, T2: Reading after cardiopulmonary bypass, T3: Reading first postoperative day, T4: Reading second postoperative day, T5: Reading third postoperative day, T6: Reading fourth postoperative day, T7: Reading fifth postoperative day. SD: Standard deviation, Group Dex: Dexmedetomidine group, Group Dopa: Dopamine group

Table 5 shows the changes in the intraoperative data and outcome of patients. There was no significant difference in the CPB time, aortic cross-clamping, cooling temperature, requirement for intra-aortic balloon pump, pacing, nitroglycerine dose, hematocrit value, transfused-packed red blood cells, and the blood loss between the two groups (P > 0.05). The required dose for epinephrine and norepinephrine was higher in the patients of Dex group than the Dopa group (P = 0.015 and P = 0.017, respectively). The required intraoperative and postoperative fluids were higher in the patients of Dex group than the Dopa group (P < 0.05). The incidence of acute renal impairment and acute renal failure was higher in the patients of Dopa group than the Dex group (P = 0.034 and P = 0.049, respectively). The requirement for temporary postoperative dialysis was higher in the patients of Dopa group than the Dex group (P = 0.049), and the incidence of the permanent dialysis was higher in the patients of Dopa group than the Dex group, but it was statistically insignificant (P = 0.310). The ICU and hospital length of stay prolonged in the patients of the Dopa group than Dex group (P < 0.05). The incidence of mortality between the two groups was statistically insignificant (P = 0.559).

Table 5.

Intraoperative data and outcome of patients

| Variable | Group Dex (n=75) | Group Dopa (n=75) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| CPB time (min) | 120.90±25.37 | 117.54±20.60 | 0.374 |

| Cross clamping time (min) | 97.48±12.25 | 94.85±11.74 | 0.181 |

| Cooling temperature (°C) | |||

| 34 | 58 | 63 | 0.408 |

| 22 | 17 | 12 | 0.408 |

| Intra-aortic balloon pump | 8 | 5 | 0.384 |

| Pacing | 15 | 9 | 0.181 |

| Epinephrine (µg/kg/min) | 0.08±0.05 | 0.06±0.03 | 0.015* |

| Norepinephrine (µg/kg/min) | 0.05±0.02 | 0.04±0.03 | 0.017* |

| Nitroglycerine (µg/kg/min) | 0.72±0.35 | 0.69±0.40 | 0.625 |

| Transfused P-RBC (unit) | 3.75±0.62 | 3.58±0.72 | 0.123 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 38.65±3.36 | 37.81±3.20 | 0.119 |

| Blood loss (mL) | |||

| Intraoperative (mL) | 2350.73±246.80 | 2320.40±225.17 | 0.433 |

| Postoperative (mL/24 h) | 775.38±156.69 | 748.85±138.00 | 0.272 |

| Intraoperative fluids | |||

| Crystalloids (mL) | 3470.75±775.40 | 3050.42±685.50 | 0.001 |

| Hesteril 6 (%) | 705.50±140.43 | 630.85±165. 30 | 0.003 |

| Postoperative fluids 24 h | |||

| Crystalloids (ml) | 4300.16±915.63 | 4000.60±938.73 | 0.049 |

| Hesteril 6 (%) | 1100.35±325.70 | 955.42±380.80 | 0.013 |

| Acute renal impairment | 4 | 12 | 0.034 |

| Acute renal failure | 2 | 8 | 0.049* |

| Postoperative dialysis | |||

| Temporarily | 2 | 8 | 0.049* |

| Permanent | 1 | 3 | 0.310 |

| ICU length of stay (days) | 4.38±1.35 | 5.03±1.89 | 0.016* |

| Hospital length of stay (days) | 6.88±2.64 | 8.03±2.85 | 0.011* |

| Mortality | 1 | 2 | 0.559 |

Data are presented as mean±SD, n (%). *P<0.05 significant comparison between the two groups. CPB: Cardiopulmonary bypass, P-RBC: Packed red blood cells, ICU: Intensive Care Unit, Group Dex: Dexmedetomidine group, Group Dopa: Dopamine group, SD: Standard deviation

Discussion

Many articles were reviewed for the pharmacological renal protection in high-risk renal patients who did cardiac surgery, but there was no article compared the continuous infusion of dexmedetomidine and dopamine during cardiac surgery, and therefore, the present study was done to assess the perioperative renal protection of these medications.

The present study showed that the perioperative continuous infusion of dexmedetomidine resulted in a decrease in the serum creatinine level and blood urea nitrogen, and also, there was an increase in the creatinine clearance and urine output in high-risk renal patients compared to the continuous infusion of dopamine. The incidence of acute renal failure decreased in the dexmedetomidine group compared to the dopamine group. The number of required patient for postoperative dialysis decreased in the dexmedetomidine group compared to the dopamine group.

These findings correlate with the study done by Niu et al.[21] that showed the renal blood flow volume increased significantly during and after CPB with administration of dexmedetomidine throughout the surgery. Ji et al.[22] showed in a retrospective analysis of 1133 patients that postbypass dexmedetomidine infusion is associated with a significant reduction in the incidence of acute renal injury after cardiac surgery. Cho et al.[23] conducted a placebo-controlled randomized controlled trial in 200 patients undergoing valvular heart disease and found that dexmedetomidine infusion reduced the incidence and severity of acute kidney injury. Furthermore, Dai et al.[24] found that small dose of dopamine (2 μg/kg/min) did not increase the renal blood flow or improve the postoperative renal function in the elderly patients undergoing cardiac valve replacement under CPB, and another study showed the occurrence of renal vasoconstriction and impairment of renal perfusion with low-dose dopamine in patients with acute renal failure.[25]

Furthermore, other studies showed no role of low-dose dopamine in renal protection.[26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35] Many randomized studies showed that the dose of dopamine (3 μg/kg/min) failed to demonstrate an improvement in the creatinine clearance, urine output and incidence of renal failure during liver transplant,[36] vascular,[37] and obstructive jaundice surgery.[38]

Dexmedetomidine induces diuresis through the following mechanisms: (1) It decreases the norepinephrine level in the blood, and thus, it induces renal artery vasodilatation and increases renal blood flow and urine output;[17,18] (2) α2-adrenoceptors exist widely in the renal peritubular vasculatures and proximal and distal tubules,[39] and therefore, it can improve the perfusion of the renal tissues; (3) it decreases the secretion of vasopressin and increases the release of atrial natriuretic peptide resulting in natriuresis;[19] (4) it induces sympatholysis attenuated sodium reabsorption in tubular cells through α 2-adrenergic action;[40] (5) it has an anti-inflammatory effect;[41,42] and (6) it has a renoprotective effect of against the ischemic and reperfusion renal injury.[43,44,45,46]

Contrary to the result of the present study, some studies showed no effect of dexmedetomidine on the serum creatinine and creatinine clearance, although the urinary output increased significantly during the first 24 h after cardiac surgery.[41,47,48] Göksedef et al.[49] found no effect of low-dose dexmedetomidine on urine output and renal indices such as urea, creatinine, and creatinine clearances. Davis et al.[14] showed that the infusion of dopamine at small doses caused a significant improvement in renal function, improving the urinary output without deleterious effects on hemodynamics. In addition, Sumeray et al.[50] showed that low-dose dopamine infusion reduces significantly the renal tubular injury following CPB surgery.

The present study did not include a control group as the dopamine was commonly used for the renoprotection during cardiac surgery, it was considered as the standard medication during the study, and the dexmedetomidine as a new medication for renoprotection was compared to dopamine.

The present study recognizes some limitations such as a being single center study as well as the small number of patients, and there was no control group.

Conclusion

The continuous infusion of dexmedetomidine during cardiac surgery has a renoprotective effect and decreased the deterioration in the renal function in high-risk renal patients compared to the continuous infusion of dopamine.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all staff nurses in the operative rooms and cardiac surgical ICU for their efforts and performance during the study.

References

- 1.Zanardo G, Michielon P, Paccagnella A, Rosi P, Caló M, Salandin V, et al. Acute renal failure in the patient undergoing cardiac operation. Prevalence, mortality rate, and main risk factors. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1994;107:1489–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levy EM, Viscoli CM, Horwitz RI. The effect of acute renal failure on mortality. A cohort analysis. JAMA. 1996;275:1489–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuitunen A, Vento A, Suojaranta-Ylinen R, Pettilä V. Acute renal failure after cardiac surgery: Evaluation of the RIFLE classification. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;81:542–6. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.07.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bastin AJ, Ostermann M, Slack AJ, Diller GP, Finney SJ, Evans TW. Acute kidney injury after cardiac surgery according to Risk/Injury/Failure/Loss/End-stage, Acute Kidney Injury Network, and Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes classifications. J Crit Care. 2013;28:389–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2012.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robert AM, Kramer RS, Dacey LJ, Charlesworth DC, Leavitt BJ, Helm RE, et al. Cardiac surgery-associated acute kidney injury: A comparison of two consensus criteria. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;90:1939–43. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chertow GM, Lazarus JM, Christiansen CL, Cook EF, Hammermeister KE, Grover F, et al. Preoperative renal risk stratification. Circulation. 1997;95:878–84. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.4.878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lema G, Urzua J, Jalil R, Canessa R, Moran S, Sacco C, et al. Renal protection in patients undergoing cardiopulmonary bypass with preoperative abnormal renal function. Anesth Analg. 1998;86:3–8. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199801000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weerasinghe A, Hornick P, Smith P, Taylor K, Ratnatunga C. Coronary artery bypass grafting in non-dialysis-dependent mild-to-moderate renal dysfunction. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2001;121:1083–9. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2001.113022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Verrier ED, Boyle EM., Jr Endothelial cell injury in cardiovascular surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 1996;62:915–22. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(96)00528-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gailiunas P, Jr, Chawla R, Lazarus JM, Cohn L, Sanders J, Merrill JP. Acute renal failure following cardiac operations. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1980;79:241–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sladen R, Prough D. Perioperative renal protection. Crit Care Clin. 1997;9:314–31. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ip-Yam PC, Murphy S, Baines M, Fox MA, Desmond MJ, Innes PA. Renal function and proteinuria after cardiopulmonary bypass: The effects of temperature and mannitol. Anesth Analg. 1994;78:842–7. doi: 10.1213/00000539-199405000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mangos GJ, Brown MA, Chan WY, Horton D, Trew P, Whitworth JA. Acute renal failure following cardiac surgery: Incidence, outcomes and risk factors. Aust N Z J Med. 1995;25:284–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.1995.tb01891.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davis RF, Lappas DG, Kirklin JK, Buckley MJ, Lowenstein E. Acute oliguria after cardiopulmonary bypass: Renal functional improvement with low-dose dopamine infusion. Crit Care Med. 1982;10:852–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jose PA, Raymond JR, Bates MD, Aperia A, Felder RA, Carey RM. The renal dopamine receptors. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1992;2:1265–78. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V281265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sirivella S, Gielchinsky I, Parsonnet V. Mannitol, furosemide, and dopamine infusion in postoperative renal failure complicating cardiac surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2000;69:501–6. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(99)01298-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ebert TJ, Hall JE, Barney JA, Uhrich TD, Colinco MD. The effects of increasing plasma concentrations of dexmedetomidine in humans. Anesthesiology. 2000;93:382–94. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200008000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taoda M, Adachi YU, Uchihashi Y, Watanabe K, Satoh T, Vizi ES. Effect of dexmedetomidine on the release of [3H]-noradrenaline from rat kidney cortex slices: Characterization of alpha2-adrenoceptor. Neurochem Int. 2001;38:317–22. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0186(00)00096-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Venn RM, Bryant A, Hall GM, Grounds RM. Effects of dexmedetomidine on adrenocortical function, and the cardiovascular, endocrine and inflammatory responses in post-operative patients needing sedation in the Intensive Care Unit. Br J Anaesth. 2001;86:650–6. doi: 10.1093/bja/86.5.650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bellomo R, Ronco C, Kellum JA, Mehta RL, Palevsky P Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative Workgroup. Acute renal failure-definition, outcome measures, animal models, fluid therapy and information technology needs: The Second International Consensus Conference of the Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative (ADQI) Group. Crit Care. 2004;8:R204–12. doi: 10.1186/cc2872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Niu J, Wang L, Liu X, Pan Y, Zhang Z, Qin G, et al. CPB and 30 min after the end of CPB. Chin J Anesthesiol. 2015;5:529–32. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ji F, Li Z, Young JN, Yeranossian A, Liu H. Post-bypass dexmedetomidine use and postoperative acute kidney injury in patients undergoing cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass. PLoS One. 2013;8:e77446. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cho JS, Shim JK, Soh S, Kim MK, Kwak YL. Perioperative dexmedetomidine reduces the incidence and severity of acute kidney injury following valvular heart surgery. Kidney Int. 2016;89:693–700. doi: 10.1038/ki.2015.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dai S, Li H, Qi J. Effects of small dose of dopamine on renal blood flow in elderly patients undergoing cardiac valve replacement under cardiopulmonary bypass. Chin J Anesthesiol. 2014;34:809–11. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lauschke A, Teichgräber UK, Frei U, Eckardt KU. ‘Low-dose’ dopamine worsens renal perfusion in patients with acute renal failure. Kidney Int. 2006;69:1669–74. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kellum JA, M Decker J. Use of dopamine in acute renal failure: A meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:1526–31. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200108000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Friedrich JO, Adhikari N, Herridge MS, Beyene J. Meta-analysis: Low-dose dopamine increases urine output but does not prevent renal dysfunction or death. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:510–24. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-7-200504050-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Padmanabhan R. Renal dose dopamine – It's myth and the truth. J Assoc Physicians India. 2002;50:571–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yavuz S, Ayabakan N, Goncu MT, Ozdemir IA. Effect of combined dopamine and diltiazem on renal function after cardiac surgery. Med Sci Monit. 2002;8:PI45–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lassnigg A, Donner E, Grubhofer G, Presterl E, Druml W, Hiesmayr M. Lack of renoprotective effects of dopamine and furosemide during cardiac surgery. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2000;11:97–104. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V11197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tang AT, El-Gamel A, Keevil B, Yonan N, Deiraniya AK. The effect of ‘renal-dose’ dopamine on renal tubular function following cardiac surgery: Assessed by measuring retinol binding protein (RBP) Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1999;15:717–21. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(99)00081-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Woo EB, Tang AT, el-Gamel A, Keevil B, Greenhalgh D, Patrick M, et al. Dopamine therapy for patients at risk of renal dysfunction following cardiac surgery: Science or fiction? Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2002;22:106–11. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(02)00246-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yavuz S, Ayabakan N, Dilek K, Ozdemir A. Renal dose dopamine in open heart surgery. Does it protect renal tubular function? J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino) 2002;43:25–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bakgün S, Tuncel SA, Kudsioʇlu ST, Aykac Z. Effect of low-dose dopamine on renal function and electrolyte extraction during cardiopulmonary bypass. Turk Nephrol. 2015;24:32–46. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pass LJ, Eberhart RC, Brown JC, Rohn GN, Estrera AS. The effect of mannitol and dopamine on the renal response to thoracic aortic cross-clamping. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1988;95:608–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Swygert TH, Roberts LC, Valek TR, Brajtbord D, Brown MR, Gunning TC, et al. Effect of intraoperative low-dose dopamine on renal function in liver transplant recipients. Anesthesiology. 1991;75:571–6. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199110000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baldwin L, Henderson A, Hickman P. Effect of postoperative low-dose dopamine on renal function after elective major vascular surgery. Ann Intern Med. 1994;120:744–7. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-120-9-199405010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Parks RW, Diamond T, McCrory DC, Johnston GW, Rowlands BJ. Prospective study of postoperative renal function in obstructive jaundice and the effect of perioperative dopamine. Br J Surg. 1994;81:437–9. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800810338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Harada T, Constantinou CE. The effect of alpha 2 agonists and antagonists on the lower urinary tract of the rat. J Urol. 1993;149:159–64. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)36030-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rouch AJ, Kudo LH, Hébert C. Dexmedetomidine inhibits osmotic water permeability in the rat cortical collecting duct. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;281:62–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Leino K, Hynynen M, Jalonen J, Salmenperä M, Scheinin H, Aantaa R Dexmedetomidine in Cardiac Surgery Study Group. Renal effects of dexmedetomidine during coronary artery bypass surgery: A randomized placebo-controlled study. BMC Anesthesiol. 2011;23(11):9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2253-11-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Khan ZP, Ferguson CN, Jones RM. alpha-2 and imidazoline receptor agonists. Their pharmacology and therapeutic role. Anaesthesia. 1999;54:146–65. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2044.1999.00659.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kocoglu H, Ozturk H, Ozturk H, Yilmaz F, Gulcu N. Effect of dexmedetomidine on ischemia-reperfusion injury in rat kidney: A histopathologic study. Ren Fail. 2009;31:70–4. doi: 10.1080/08860220802546487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.İnci F, Varlık Doğan I, Eti Z, Deniz M, Yılmaz Gogus F, Yagmur F. The effects of dexmedetomidine infusion on the formation of reactive oxygen species during mesenteric ischemia-reperfusion injury in rats. Marmara Med J. 2007;20:154–60. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Si Y, Bao H, Han L, Shi H, Zhang Y, Xu L, et al. Dexmedetomidine protects against renal ischemia and reperfusion injury by inhibiting the JAK/STAT signaling activation. J Transl Med. 2013;11:141. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-11-141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ammar AS, Mahmoud KM, Kasemy ZA, Helwa MA. Cardiac and renal protective effects of dexmedetomidine in cardiac surgeries: A randomized controlled trial. Saudi J Anaesth. 2016;10:395–401. doi: 10.4103/1658-354X.177340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Salah M, El-Tawil T, Nasr S, Nosser T. Does dexmedetomidine affect renal outcome in patients with renal impairment undergoing CABG? Egypt J Cardiothorac Anesth. 2013;7:7–12. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Balkanay OO, Goksedef D, Omeroglu SN, Ipek G. The dose-related effects of dexmedetomidine on renal functions and serum neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin values after coronary artery bypass grafting: A randomized, triple-blind, placebo-controlled study. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2015;20:209–14. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivu367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Göksedef D, Balkanay OO, Ömeroğlu SN, Talas Z, Arapi B, Junusbekov Y, et al. The effects of dexmedetomidine infusion on renal functions after coronary artery bypass graft surgery: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Turkish J of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 2013;21:594–602. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sumeray M, Robertson C, Lapsley M, Bomanji J, Norman AG, Woolfson RG. Low dose dopamine infusion reduces renal tubular injury following cardiopulmonary bypass surgery. J Nephrol. 2001;14:397–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]