Abstract

Background:

The ideal anaesthetic technique for management of paediatric patients scheduled to undergo cardiac catheterisation is still not standardised.

Aim:

To compare the effects of ketamine-propofol and ketamine-dexmedetomidine combinations on hemodynamic parameters and recovery time in paediatric patients undergoing minor procedures and cardiac catheterisation under sedation for various congenital heart diseases.

Material and Methods:

60 children of either sex undergoing cardiac catheterisation were randomly assigned into two groups Dexmedetomidine-ketamine group (DK) and Propofol-ketamine (PK) of 30 patients each. All patients were premedicated with glycopyrrolate and midazolam (0.05mg/kg) intravenously 5-10 min before anaesthetic induction. Group ‘DK’received dexmedetomidineiv infusion 1 μg/kg over 10 min + ketamine1mg/kg bolus, followed by iv infusion of dexmedetomidine 0.5μg/kg/hr and of ketamine1 mg/kg/hr. Group ‘PK’ received propofol 1mg/kg and ketamine 1mg/kg/hr for induction followed by iv infusion of propofol 100 μg/kg/hr and ketamine 1 mg/kg/hr for maintenance. Haemodynamic parameters and recovery time was recorded postoperatively.

Statistical Analysis:

Independent sample t test was used to compare the statistical significance of continuous variables of both the groups. Chi square test was used for numerical data like gender. Fischer exact test was applied for non parametric data like ketamine consumption.

Results:

We observed that heart rate in dexmedetomidine (DK) group was significantly lower during the initial 25 mins after induction compared to the propofol (PK) group. Recovery was prolonged in the DK group compared to the PK group (40.88 vs. 22.28 min). Even ketamine boluses consumption was higher in DK group.

Conclusion:

Use of dexmedetomidine-ketamine combination is a safe alternative, without any hemodynamic orrespiratory effects during the cardiac catheterization procedure but with some delayed recovery.

Keywords: Cardiac catheterization, children, dexmeditomidine, ketamine, propofol

Introduction

The ideal anesthetic technique for management of pediatric patients scheduled to undergo cardiac catheterization should be safe, easy to administer, provide adequate sedation, amnesia, immobility, cardiovascular stability, and fast recovery without residual complications. Management of children with congenital heart disease has been a great challenge for anesthesiologists especially during cardiac catheterization. General anesthesia with positive pressure ventilation can alter the intracardiac pressures as well as shunt fraction. Therefore, deep sedation with pain-free and spontaneously breathing patient on room air is preferred by the cardiac interventionist.

A wide variety of anesthetic agents such as propofol,[1,2] ketamine,[3,4] and dexmedetomidine[5,6] are used for this purpose. The goals of anesthesia for catheterization are analgesia, anxiolysis, amnesia for the patient, and easy separation from parents. At the same time, maintenance of airway, ventilation, acid-base balance, and temperature management are equally important. The anesthetic agent should optimize hemodynamic status before, during, and after the procedure tailored to the specific physiology of the individual patient and ensure smooth recovery.[7]

The commonly performed cardiac catheterization laboratory procedures include diagnostic catheterization and Interventional procedures such as pulmonary artery angioplasty, aortic-coarctation angioplasty, patent ductus arteriosus occlusion or stenting, ventricular septal defect closure, atrial septostomy, atrial septal defect closure, and aortic/pulmonary/mitral valve dilation.[8]

This study was undertaken with an aim to compare the effects of dexmedetomidine-ketamine (DK) and propofol ketamine (PK) combinations on hemodynamic parameters and recovery time in pediatric patients undergoing minor cardiac procedures in cardiac catheterization laboratory.

Methods and Material

A prospective, randomized, controlled study was undertaken in a large tertiary teaching hospital from December 2013 to January 2015. After obtaining Institutional Ethical Committee approval, informed written consent was taken from all the patients’ guardians before the procedure. The patients were randomly assigned into two groups: DK and PK with 30 children in each group by using sealed envelope method. All children between the age group of 1 month to 10 years of either sex undergoing cardiac catheterization lab procedures were included in the study. Children with chromosomal abnormalities or other multiple congenital anomalies, drug allergy, patients requiring mechanical ventilation or inotropic support, and patients with hepatic or renal dysfunction were excluded from the study.

According to hospital policy, all children were kept fasting for at least 6 h before procedure. The patients were premedicated with glycopyrrolate (10 μg/kg) and midazolam (50 μg/kg) intravenously (IV) 10 min before taking the child inside the catheterization laboratory where appropriate measures to prevent hypothermia to child were undertaken. Standard monitors including electrocardiogram and pulse-oximeter were attached. Group (DK) received: dexmedetomidine IV infusion 1 μg/kg over 10 min + ketamine 1 mg/kg IV bolus for induction and then maintenance by IV infusion of 0.5 μg/kg/h of dexmedetomidine and 1 mg/kg/h of ketamine. Group (PK) received propofol 1mg/kg and ketamine 1 mg/kg IV for induction and then maintenance by IV infusion of 100 μg/kg/min of propofol and 1 mg/kg/h of ketamine. Additional doses of ketamine 0.5 mg/kg IV bolus were administered when a child showed discomfort in both groups. Heart rate, mean blood pressure (BP), oxygen saturation (SpO2), and respiratory rate were recorded every 5 min during the procedure. Postoperatively, heart rate and SpO2 were recorded every 10 min. Recovery time was noted. Scores were assigned on admission to postanesthetic room where the routine vital signs were measured. Repeated scoring was performed every 10 min till the patient recovered up to score of 6 according to the Stewards Simplified Postanesthetic Recovery Score[9] [Table 1].

Table 1.

Stewards scoring system for post-op recovery

| Score | |

|---|---|

| Consciousness | |

| Awake | 2 |

| Responding to stimuli | 1 |

| Not responding | 0 |

| Airway | |

| Coughing on command or crying | 2 |

| Maintaining good airway | 1 |

| Airway requires maintenance | 0 |

| Movement | |

| Moving limbs purposefully | 2 |

| Non-purposeful movements | 1 |

| Not moving | 0 |

For statistical analysis, a sample size of 30 in each group was calculated with an alpha error of 5% (confidence interval 95%) and power of study of 80% and data analysis was done using statistical software version 17.0. This mean and standard deviation were used for continuous data such as age, weight, duration of surgery, heart rate, BP, respiratory rate, and recovery time. Independent sample t-test was used to compare the statistical significance of continuous variables of both the groups. Chi-square test was used for numerical data like gender. Fischer exact test was applied for nonparametric data like ketamine consumption.

Results

A total of 60 children were recruited in this study. There was no significant difference between the two groups with respect to patient characteristics, type and mean duration of surgery.

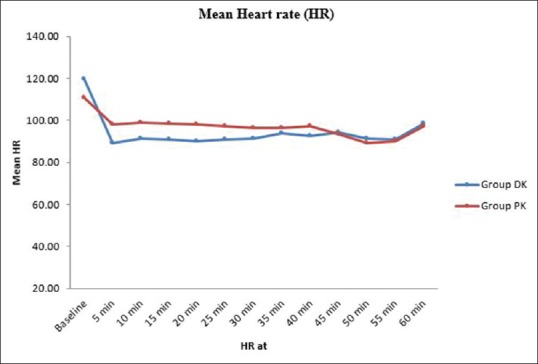

The patient's age and weight were comparable in two groups [Tables 2 and 3]. The mean age in DK group was 4.84 (±2.61) years and in PK group was 5.08 (±2.22) years with P = 0.627. The mean weight in DK group was 15.52 (±6.26) kg and in PK group was 16.56 (±5.35) kg with P = 0.541. By using two independent sample t-test, P > 0.05, therefore there was no significant difference between mean age and weight between the two groups. Mean duration of surgery/procedure in group DK and group PK was 44.04 ± 10.81 min and 39.20 ± 11.70, and there was no significant difference in duration of surgery (P ≥ 0.05). The two groups were comparable with respect to type of surgery/procedure [Table 4]. Heart rate was significantly lower in DK group at 5, 10, 15, 20, 25 min postinduction in comparison to PK group. Later on, the heart rate continued to be lower in both the groups but it was not statistically significant [Figure 1].

Table 2.

Comparison of mean age (years) in group DK and PK

| Group | No | Age (years) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | |||

| Group DK | 30 | 4.84 | 2.61 | 0.627 |

| Group PK | 30 | 5.08 | 2.22 | |

Table 3.

Comparison of weight (kgs) in group DK and PK

| Group | Number of patients | Weight (kg) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | |||

| Group DK | 30 | 15.52 | 6.26 | 0.541 |

| Group PK | 30 | 16.56 | 5.35 | |

Table 4.

Comparison of type of procedure in group DK and PK

| S.no | Type of procedure | Group DK | Group PK | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | ASD for device closure | 9 | 8 | 17 |

| 2. | VSD for device closure | 6 | 6 | 12 |

| 3. | PDA for device closure | 8 | 8 | 16 |

| 4 | Cath study | 6 | 7 | 13 |

| 5 | Bicuspid aortic valve with severe AS | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Total | 30 | 30 | 60 |

Figure 1.

Comparison of mean heart rate in the two groups

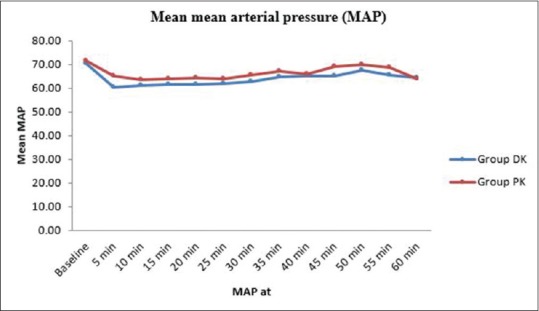

There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups in mean BP [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Comparison of mean blood pressure in the two groups

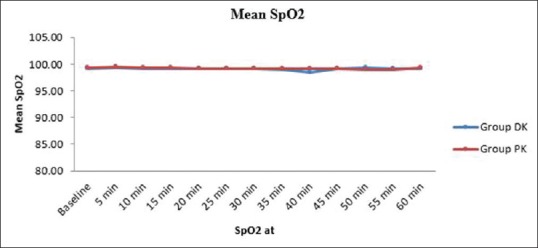

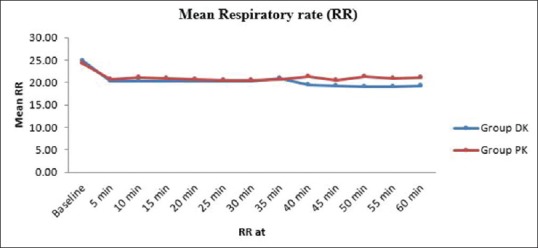

There was no significant difference between mean SpO2 in group DK and group PK from baseline to 60th min [Figure 3]. There was no significant difference between the respiratory rate in group DK and group PK from baseline to 60th min [Figure 4]. Recovery was significantly delayed in DK group (40.88 ± 8.19) versus 22.28 ± 3.63 min in PK group (P ≤ 0.05) [Table 5]. Actual ketamine consumption was (2.02 mg/kg/h) in DK group, whereas in PK group, it was (1.25 mg/kg/h). Ketamine boluses consumption was significantly higher in DK group (09 patients in DK vs. 02 patients in PK) (P ≤ 0.05) [Table 6].

Figure 3.

Comparison of mean oxygen saturation in the two groups

Figure 4.

Comparison of mean respiratory rate in the two groups

Table 5.

Comparison of mean recovery time (mins) in group DK and PK

| Group | Number of patients | Recovery time (min) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | |||

| Group DK | 30 | 40.88 | 8.19 | <0.001 |

| Group PK | 30 | 22.28 | 3.63 | |

Table 6.

Comparison of ketamine boluses consumption (n) in group DK and PK

| Ketamine used | Group | Total | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group DK | Group PK | |||

| Yes | 21 | 28 | 49 | 0.037 |

| No | 9 | 2 | 11 | |

| Total | 30 | 30 | 60 | |

Discussion

Pediatric cardiac catheterization procedures are different from adults in several ways including different types of disease pattern in the patient, different requirements for the procedure, mandatory sedation or general anesthesia so as to prevent movement in almost all patients and a need of complete evaluation of structurally abnormal heart. Commonly performed procedures are angioplasty, valvuloplasty, coil embolization, atrial septostomy, device closure, diagnostic cath studies, and electrophysiological studies.

In this study, we compared the DK versus propofol ketamine combinations on hemodynamic stability and recovery time in 60 spontaneously breathing children undergoing cardiac catheterization. We observed decrease in the heart rate after induction in both the groups, but the decrease was statistically significant in the dexmedetomidine-ketamine group in the first 25 min after induction. Later on, the decrease in heart rate was persistent in both the groups till the end of procedure but it was not statistically significant. In a similar study by Tosun et al., the effects of DK and PK combinations on hemodynamics, sedation level, and the recovery period in pediatric patients undergoing cardiac catheterization were studied.[10] The heart rate in Group 1 was significantly lower (average 10–20 beats/min) than Group 2 after induction and throughout the procedure. We found a similar decrease in the heart rate in the dexmedetomidine-ketamine group. Systolic, diastolic, and mean BP were reduced after induction in both the groups, but there was no statistically significant difference in the mean BP between the two groups during the procedure. In a similar study by Ali et al. which compared DK and PK as anesthetic agents in pediatric cardiac catheterization, clinical outcome of both groups was similar and there was no significant difference in the recovery patterns and hemodynamic status.[11] In our study, we had similar results in terms of BP, SpO2 and Respiratory rate between the two groups.

Propofol has been recommended for pediatric cardiac catheterization because of rapid emergence it produces. Gozal et al. studied the effects of propofol on the systemic and pulmonary circulations on the pediatric patients scheduled for cardiac catheterization.[12] The patients were given 1 μg/kg fentanyl and 1–2 mg/kg propofol by bolus and then a 100 μg/kg/min infusion of propofol. They reported that propofol seemed to an adequate sedative agent for pediatric patients undergoing cardiac catheterization, including those with intracardiac shunts. Morray JP et al. assessed the hemodynamic effects of ketamine in children with congenital heart disease.[13] Pulmonary and systemic vascular responses to ketamine (2 mg/kg, intravenously) were studied during cardiac catheterization in 20 children with congenital heart lesions. It was concluded that the hemodynamic alterations after ketamine administration in children undergoing cardiac catheterization were small and did not alter the clinical status of the patients or the information obtained by cardiac catheterization.

The alpha 2 agonist dexmedetomidine is a new sedative, analgesic, and anxiolytic agent. Its intraoperative administration reduces anesthetic requirements, speeds postoperative recovery, and blunts the sympathetic nervous system response to surgical stimulation. Munro et al. reported their experience using dexmedetomidine in 20 children aged 3 months to 10 years undergoing cardiac catheterization.[14] A loading dose of 1 μg/kg dexmedetomidine was administered over 10 min followed by an initial infusion rate of 1 μg/kg/h. Hemodynamic parameters, bispectral index score, and sedation score were measured every 5 min. Their initial experience showed dexmedetomidine, with or without the addition of propofol, may be a suitable alternative for sedation in spontaneously breathing patients undergoing cardiac catheterization.

In this study, the recovery time was significantly longer in DK group compared to the PK group (40.88 ± 8.19 vs. 22.28 ± 3.63 min) P ≤ 0.05. The study conducted by Heard et al. which compared the Dexmedetomidine-Midazolam with propofol for maintenance of anesthesia in children undergoing magnetic resonance imaging suggested that the time to full recovery was significantly longer after dexmedetomidine administration than after propofol by 15 min.[15] In a study conducted by Thimmarayappa et al., airway patency was measured objectively during dexmedetomidine sedation under radiographic guidance in spontaneously breathing pediatric patients scheduled for cardiac catheterization procedures.[16] The average recovery time from dexmedetomidine sedation after stopping the infusion was 39.86 ± 12.22 min with maximum being 70 min.

Ketamine boluses consumption was more in DK group than the PK group. Nine children in DK group required additional boluses of ketamine when compared to 2 children in PK group. Similar study by Tosun et al. which compared the same drugs for children undergoing minor cardiac procedures in cardiac catheterization laboratory, showed that ketamine consumption in dexmedetomidine group was more than the propofol group (2.03 vs. 1.25 mg/kg/h).[10] Our study showed similar high utilization of ketamine in dexmedetomidine group compared to the propofol group. None of the children in both the groups showed any side effects like bradycardia, oxygen desaturation, hypotension requiring any treatment, convulsions, laryngospasm, agitation, hiccups, shivering, increased oral secretions, nausea, and vomiting.

Conclusion

This study which compared the dexmedetomidine and ketamine versus propofol and ketamine combinations on hemodynamic stability, respiratory variables, and recovery time in children undergoing minor cardiac procedures in cardiac catheterization laboratory concludes that the use of DK combination is a safe, practical alternative, without any hemodynamic or respiratory effects during the cardiac catheterization laboratory procedure but with some delayed recovery.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Williams GD, Jones TK, Hanson KA, Morray JP. The hemodynamic effects of propofol in children with congenital heart disease. Anesth Analg. 1999;89:1411–6. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199912000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hertzog JH, Campbell JK, Dalton HJ, Hauser GJ. Propofol anesthesia for invasive procedures in ambulatory and hospitalized children: Experience in the pediatric Intensive Care Unit. Pediatrics. 1999;103:E30. doi: 10.1542/peds.103.3.e30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berman W, Jr, Fripp RR, Rubler M, Alderete L. Hemodynamic effects of ketamine in children undergoing cardiac catheterization. Pediatr Cardiol. 1990;11:72–6. doi: 10.1007/BF02239565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Akin A, Esmaoglu A, Guler G, Demircioglu R, Narin N, Boyaci A. Propofol and propofol-ketamine in pediatric patients undergoing cardiac catheterization. Pediatr Cardiol. 2005;26:553–7. doi: 10.1007/s00246-004-0707-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tobias JD. Dexmedetomidine and ketamine: An effective alternative for procedural sedation? Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2012;13:423–7. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e318238b81c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhana N, Goa KL, McClellan KJ. Dexmedetomidine. Drugs. 2000;59:263–8. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200059020-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bernard PA, Ballard H, Schneider D. Current approaches to pediatric heart catheterizations. Pediatr Rep. 2011;3:e23. doi: 10.4081/pr.2011.e23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abbas SM, Rashid A, Latif H. Sedation for children undergoing cardiac catheterization: A review of literature. J Pak Med Assoc. 2012;62:159–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steward DJ. A simplified scoring system for the post-operative recovery room. Can Anaesth Soc J. 1975;22:111–3. doi: 10.1007/BF03004827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tosun Z, Akin A, Guler G, Esmaoglu A, Boyaci A. Dexmedetomidine-ketamine and propofol-ketamine combinations for anesthesia in spontaneously breathing pediatric patients undergoing cardiac catheterization. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2006;20:515–9. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2005.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ali NP, Kanchi M, Singh S, Prasad A, Kanase N. Dexmedetomedine-Ketamine versus Propofol-Ketamine as anaesthetic agents in paediatric cardiac catheterization. J Armed Forces Med Coll Bangladesh. 2015;10:19–24. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gozal D, Rein AJ, Nir A, Gozal Y. Propofol does not modify the hemodynamic status of children with intracardiac shunts undergoing cardiac catheterization. Pediatr Cardiol. 2001;22:488–90. doi: 10.1007/s002460010280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morray JP, Lynn AM, Stamm SJ, Herndon PS, Kawabori I, Stevenson JG. Hemodynamic effects of ketamine in children with congenital heart disease. Anesth Analg. 1984;63:895–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Munro HM, Tirotta CF, Felix DE, Lagueruela RG, Madril DR, Zahn EM, et al. Initial experience with dexmedetomidine for diagnostic and interventional cardiac catheterization in children. Paediatr Anaesth. 2007;17:109–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2006.02031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heard C, Burrows F, Johnson K, Joshi P, Houck J, Lerman J. A comparison of dexmedetomidine-midazolam with propofol for maintenance of anesthesia in children undergoing magnetic resonance imaging. Anesth Analg. 2008;107:1832–9. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e31818874ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thimmarayappa A, Chandrasekaran N, Jagadeesh AM, Joshi SS. Pediatric cardiac catheterization procedure with dexmedetomidine sedation: Radiographic airway patency assessment. Ann Card Anaesth. 2015;18:29–33. doi: 10.4103/0971-9784.148318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]