Abstract

The circadian clock refers to the inherent biological rhythm of an organism, which, is accurately regulated by numerous clock genes. Studies in recent years have reported that the abnormal expression of clock genes is ubiquitous in common abdominal malignant tumors, including liver, colorectal, gastric and pancreatic cancer. In addition, the abnormal expression of certain clock genes is closely associated with clinical tumor parameters or patient prognosis. Studies in clock genes may expand the knowledge about the mechanism of occurrence and development of tumors, and may provide a new approach for tumor therapy. The present study summarizes the research progress in this field.

Keywords: circadian clock, abdominal surgery, malignant tumor, cancer

1. Introduction

The earliest finding of a circadian clock was the change in position of plant leaves, which spread during the day and droop at night, corresponding to an oscillation with a 24-h period (1,2). Subsequently, circadian clocks were also identified in the form of clear circadian rhythms in the eclosion of insects (3–6), hibernation of animals (7–9), and body temperature, blood pressure and pulse in humans (10–13). The circadian clock is an inherent rhythm developed by life on the earth's surface during the long-term evolutionary process to adapt to ambient and external environments (particularly, to the sunrise and sunset) (14,15).

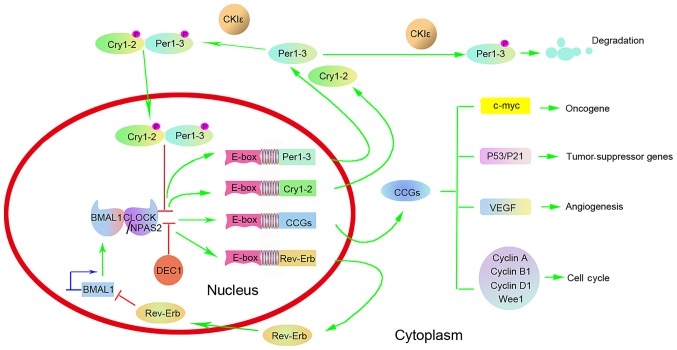

Multiple clock genes, including circadian locomotor output cycles kaput (CLOCK), brain and muscle arylhydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator (ARNT)-like 1 (BMAL1), period (Per)1, Per2, Per3, cryptochrome (Cry)1, Cry2, neuronal Per-Arnt-Sim (PAS) domain protein 2 (NPAS2), casein kinase Iε (CKIε), timeless (Tim), nuclear receptor subfamily 1, group D, member 1 (NR1D1, also known as Rev-Erb-α) and differentiated embryo-chondrocyte expressed gene (DEC), accurately regulate the human circadian clock at the molecular level (16–18). These genes constitute two important feedback loops. CLOCK is the core factor of the circadian clock and combines with BMAL1 to form a heterodimer through its basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH)-PAS structural domain. The heterodimer combines with the E-box on the promoter of the Per1-3 and Cry1-2 genes, and activates their transcription. The coding products, the Per1-3 and Cry1-2 proteins, are transported from the cytoplasm to the nucleus, where they directly combine with CLOCK/BMAL1, which inhibits their activities and further blocks the transcription of Per1-3 and Cry1-2. In addition to activating the transcription of Per1-3 and Cry1-2, the CLOCK/BMAL1 heterodimer also activates the transcription of the orphan nuclear receptor Rev-Erb gene (17,19) (Fig. 1). The protein encoded by the Rev-Erb gene can combine with the BMAL1 promoter and block its transcription (17). Since genetic transcription, translation and protein transport from the cytoplasm to the nucleus lasts a certain time, the oscillation of the biological rhythm proceeds with a periodic length of ~24 h via self-induction (18,19). Such a negative feedback cycle of the clock genes forms a precise endogenous ‘molecular clock’ in the body. Clock genes output the rhythm signal of a circadian clock through downstream clock controlled genes (CCGs). Thereby, molecular activity within the cell also exhibits a temporal rhythm (18,19).

Figure 1.

Representation of the circadian clock network. CLOCK or NPAS2 combines with BMAL1 to form a core CLOCK/BMAL1 or NPAS2/BMAL1 transcriptional complex, which subsequently activates the transcription of Per1-3 and Cry1-2 via E-box elements on their promoters. DEC1 can compete with CLOCK/BMAL1 or NPAS2/BMAL1 heterodimers for E-box binding and therefore inhibit CLOCK/BMAL1-mediated transactivation. The coding products, the Per1-3 and Cry1-2 proteins, form a multimeric complex, translocate from the cytoplasm to the nucleus and inhibit CLOCK/BMAL1-mediated transcription. Degradation of Per1-3 and Cry1-2 proteins prompts a new circadian cycle whereby CLOCK/BMAL1 transcription is reinitiated. The CLOCK/BMAL1 heterodimer also activates the transcription of the orphan nuclear receptor Rev-Erb gene. The protein encoded by the Rev-Erb gene can combine with the BMAL1 promoter and block its transcription. Besides transcriptional regulation, post-translational modifications are also involved in the modulation of circadian proteins. CKIε can phosphorylate Per1-3 and Cry1-2 proteins, and enable Per1-3 and Cry1-2 proteins to be translocated from the cytoplasm to the nucleus. In addition, CKIε-mediated phosphorylation can also destabilize Per1-3 proteins. Finally, the CLOCK/BMAL1 complex regulates the expression of CCGs, including oncogenes (c-myc), tumor-suppressor genes (P53 and P21), genes involved in the regulation of the cell cycle (cyclins A, B1 and D1, and WEE1 G2 checkpoint kinase) and VEGF. These target genes regulated by the biological clock genes are involved in DNA repair, cell proliferation and apoptosis. Therefore, circadian clock disorders may lead to uncontrolled cell growth and malignant transformation. CLOCK, circadian locomotor output cycles kaput; NPAS2, neuronal Per-Arnt-Sim domain-containing protein 2; BMAL1, brain and muscle arylhydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator-like 1; Per, period; Cry, cryptochrome; DEC, differentiated embryo-chondrocyte expressed gene; CKIε, casein kinase Iε; CCG, circadian-clock-controlled gene; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

2. CLOCK

In May 1997, the Takahashi research group of Northwestern University (Evanston, USA) successfully cloned the murine CLOCK gene (20). This represented a milestone in the study of the molecular mechanism of circadian clocks in mammals. In 1999, this group reported the cloning of the human CLOCK gene, which is located on the long arm of chromosome 4 (4q12) and comprises a protein-coding sequence of 2,538 bp. The CLOCK gene belongs to the bHLH-PAS family of transcriptional regulatory factors (21). The containing bHLH domain participates in protein-protein interactions for the formation of protein dimers (21). Two PAS structural domains (PAS-A and PAS-B) mediate the combination of the protein with DNA. Furthermore, the glutamine-rich C-terminus of the CLOCK protein also participates in transcriptional activation (21). The CLOCK gene is a necessary regulator of the circadian rhythm and serves a central role in the circadian clock system. Homozygote mice with CLOCK mutations develop both circadian clock rhythm and feeding rhythm disorders (22,23).

3. BMAL1

BMAL1, also called ARNT3, was identified by Ikeda and Nomura in 1997 (24). BMAL1 is 32-kb long and its coding product belongs to the bHLH-PAS family (24). A clear circadian rhythm was observed in the expression pattern of BMAL1 in suprachiasmatic nuclei (SCN) of mice (25). BMAL1 knockout mice completely lose their circadian rhythm in constant darkness (25). In addition to participating in the regulation of the circadian clock, BMAL1 is also associated with glucose metabolism (26–28), energy conservation (26–28) and aging (29,30).

4. Per1, Per2 and Per3

In 1971, Konopka and Benzer located the Per gene in the X chromosome of Drosophila when observing the influence of gene mutations on the circadian rhythm (31). The Per gene of Drosophila has three mutant types: PerO, PerL and PerS. These mutant phenotypes exhibit circadian rhythm disappearance, extension and shortening, respectively. Subsequently, similar genes to the Per gene of Drosophila with genotypes Per1 Per2 and Per3 were also identified in mice and humans (31). The Per1-3 genes not only participate in the regulation of the circadian clock, but also inhibit the growth and proliferation of tumor cells, and induce apoptosis, thus being considered as potential tumor-suppressor genes (32–36).

5. Cry1 and Cry2

The Cry gene was initially discovered in plants (37). It encodes the photoreception molecule of blue light and participates in the circadian rhythm reaction guided by blue light in plants. Although this gene also is present in mammals in the mutant forms Cry1 and Cry2, it is unable to act as a photoreceptor in mammals (38). The mutation of mouse (m)Cry2 leads to a 1-h extension of free-motion period. However, the Cry1 mutant manifests the reverse phenotype. The mutant of both mCry1 and mCry2 manifests circadian rhythm disorders, which indicates that mCry1 and mCry2 are core elements of the circadian rhythm (38).

6. NPAS2

NPAS2, also known as member of PAS protein 4 (MOP4), is located on the human chromosome 2p11.2–2q13. Similar to CLOCK, NPAS2 also belongs to the bHLH-PAS family. NPAS2 exhibits the bHLH structural domain at its N-terminus, and two PAS structural domains (PAS-A and PAS-B) in addition to a nuclear receptor-joining region at its C-terminus (39). NPAS2 can regulate the circadian clock rhythm by forming an NPAS/BMAL1 heterodimer with BMAL1, combining with the target gene promoter E-box, and regulating the expression of the Per and Cry genes (40). NPAS2 is an essential gene to maintain a normal biological rhythm. Disorders of the circadian rhythm could be caused by mutation or deletion of NPAS2 (40). In addition, NPAS2 also regulates and interferes with oncogenes, tumor-suppressor genes, and genes associated with the cell cycle, cell proliferation and apoptosis (41–43). Furthermore, NPAS2 is important in cell cycle regulation, DNA damage repair response and tumor growth inhibition, and may also act as a tumor-suppressor gene (41–43).

7. CKIε

CKIε was cloned in 1995 (44). Its protein product, CKIε, belongs to the serine/threonine kinase family, has a relative molecular weight of 43.7 kDa and is widely distributed in its monomeric form (44). CKIε can phosphorylate BMAL1, Per1, Per2, Per3, Cry1 and Cry2 proteins, thus regulating their activity and stability. In addition, CKIε can regulate clock genes at the post-translational level (45–47).

8. Rev-Erb-α and Rev-Erb-β

Rev-Erb-α (identified in 1989) and Rev-Erb-β (identified in 1994) are members of the nuclear receptor superfamily of ligand-inducible transcription factors (48,49). Both receptors possess a DNA-binding domain with a conservative zinc finger and a ligand-binding domain. The DNA-binding domain contains the sequence coding the nuclear localization signal. Depending on the circadian rhythm, these domains are expressed in the human supraoptic nuclei, liver and heart (48,49). Rev-Erb-α can inhibit the expression of CLOCK (50), BMAL1 (51) and NPAS2 (52). The SCN of Rev-Erb-α knockout mice do not periodically express BMAL1 and their active phase is shortened. This indicates that Rev-Erb-α is required for maintaining the accuracy of the circadian clock (53). A previous study indicated that Rev-Erb-α and Rev-Erb-β coordinated to protect against major perturbations in circadian and metabolic physiology (54). The periodic expression of the core circadian clock and the lipid metabolism network were observed to be markedly dysregulated in Rev-Erb-α and Rev-Erb-β knockout mice, which indicates that Rev-Erb-α and Rev-Erb-β are also important components of the circadian clock core mechanism (17,55,56).

9. DEC1 and DEC2

The genes DEC1 and DEC2 were identified in 1997 (57) and 2001 (58), respectively. Both transcription factors contain the bHLH structure, but not the PAS domain. The level of homology of DEC1 and DEC2 in the bHLH region is 97%, while that in the orange region (a motif of ~35 amino acids located C-terminally of the bHLH domain, providing an additional protein-protein interaction interface) is only 52% (59). In contrast to DEC1, the DEC2 transcription factor is rich in alanine and glycine, which may be one of the main reasons for their functional difference (59,60). DEC1 is widely expressed in multiple tissues, while the expression of DEC2 is highly tissue-dependent (59,60). DEC1 can downregulate and inhibit the activity of DEC2. Following combination with E-box functional elements (CACGTG) located on the clock gene promoter, DEC1 and DEC2 regulate the circadian clock rhythm through inhibiting the transcriptional activation process mediated by the CLOCK/BMAL1 heterodimer (61,62). Both transcription factors, particularly DEC2, are closely associated with sleep disorders (61). In addition, DEC1 and DEC2 also participate in regulating the expression of factors associated with tumor growth and apoptosis, and are linked to tumor occurrence and development (63–66).

10. Tim

In 1994, Sehgal et al screened a new mutant influencing the biological rhythm of Drosophila in a similar manner than PerO. The corresponding wild-type gene of this mutant gene was named Tim (67). Since the identification of the Tim gene occurred on the 1990s, in-depth studies are still required at present to elucidate its role in the regulation of the human circadian clock (68).

11. Conclusions

In recent years, due to the accelerated pace of life and an increased pressure for competition, a large number of people stay awake until late, lose sleep and miss meals, causing a circadian clock disorder and an increase in circadian clock disorder-related diseases (69–71). Epidemiologic studies revealed that circadian rhythm disorders (mainly caused by the influence of light) are correlated with breast, ovarian and prostate cancer. Working on night or rotating shifts is linked to a greatly increased risk for women to develop breast and ovarian cancer, and for men to develop prostate cancer (69–71). Clock genes contribute to the occurrence and development of tumors by regulating and interfering with oncogenes (c-myc), tumor-suppressor genes (P53 and P21), genes involved in the regulation of the cell cycle (cyclins A, B1 and D1, and WEE1 G2 checkpoint kinase) and vascular endothelial growth factor, as well as affecting the internal secretion pathway (72–81) (Fig. 1). These target genes regulated by the biological clock genes are involved in DNA damage repair, cell proliferation and apoptosis. Thus, biological clock disorders are likely to lead to uncontrolled cell growth and malignant transformation (73).

Although the exact association between clock genes and common abdominal malignant tumors, including liver cancer (82,83), colorectal cancer (84–92), gastric cancer (93,94) and pancreatic cancer (95), is not clear yet, it has been demonstrated that an abnormal expression of clock genes is ubiquitous in these tumors. Abnormal expression of the CLOCK gene may be one of the important reasons for occurrence and development of these tumors. The relevant articles are summarized in Tables I and II.

Table I.

Expression of clock genes in liver, colorectal, gastric and pancreatic cancer.

| Clock gene expression | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author, year | Cancer type | Country | Carcinoma/peritumoral tissue cases, n | Detection method | CLOCK | BMAL1 | Per1 | Per2 | Per3 | Cry1 | Cry2 | CKIε | Tim | (Refs.) |

| Lin et al, 2008 | Liver | Taiwan | 46/46 | RT-qPCR and IHC | NS | NS | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | NS | ↓ | NS | ↓ | (82) |

| Yang et al, 2014 | Liver | China | 30/30 | RT-qPCR | NS | NS | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | NS | ↓ | NS | ND | (83) |

| Krugluger, et al 2007 | Colorectal | Austria | 30/30 | RT-qPCR | NS | ND | ↓ | NS | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | (84) |

| Wang et al, 2011 | Colorectal | China | 38/38 | RT-qPCR and IHC | ND | ND | ND | ↓ | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | (85) |

| Mazzoccoli et al, 2011 | Colorectal | Italy | 19/19 | RT-qPCR | NS | ND | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | NS | ↓ | NS | ↑ | (86) |

| Oshima et al, 2011 | Colorectal | Japan | 202/202 | RT-qPCR | ↑ | NS | ↓ | NS | ↓ | NS | NS | ↑ | ND | (87) |

| Wang et al, 2012 | Colorectal | China | 203/203 | RT-qPCR and IHC | ND | ND | ND | ND | ↓ | ND | ND | ND | ND | (88) |

| Karantanos et al, 2013 | Colorectal | China | 30/30 | RT-qPCR and IF | ↑ | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | (89) |

| Wang et al, 2013 | Colorectal | China | 168/10 | RT-qPCR and IHC | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ↑ | ND | ND | ND | (90) |

| Yu et al, 2013 | Colorectal | Greece | 42/42 | RT-qPCR | ↑ | ↑ | ↓ | NS | ↓ | ND | ND | ND | ND | (91) |

| Wang et al, 2015 | Colorectal | China | 203/203 | RT-qPCR and IHC | ND | ND | ↓ | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | (92) |

| Zhao et al, 2014 | Gastric | China | 246/45 | IHC | ND | ND | ↓ | ND | ↓ | ND | ND | ND | ND | (93) |

| Hu et al, 2014 | Gastric | Taiwan | 29/29 | RT-qPCR and IHC | NS | NS | NS | ↑ | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | (94) |

| Relles et al, 2013 | Pancreatic | USA | 65/50 | RT-qPCR | NS | NS | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | NS | ↓ | ↓ | NS | (95) |

CLOCK, circadian locomotor output cycles kaput; BMAL1, brain and muscle arylhydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator-like 1; Per, period; Cry, cryptochrome; CKIε, casein kinase Iε; CCG, circadian-clock-controlled gene; Tim, timeless; RT-qPCR, reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction; IHC, immunohistochemistry; IF, immunofluorescence; NS, no significant difference between expression in carcinoma and para-carcinoma tissues; ↓, decreased expression in carcinoma tissue; ↑, increased expression in carcinoma tissue; ND, not detected.

Table II.

Association between expression of clock genes and clinical parameters of liver, colorectal, gastric and pancreatic cancer.

| Author, year | Cancer type | Country | Association | (Refs.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lin et al, 2008 | Liver | Taiwan | Per2 and Per3 were correlated with the size of liver cancer; Tim was correlated with the pathological grade of liver cancer | (82) |

| Yang et al, 2014 | Liver | China | Association of clock genes with clinical parameters was not analyzed | (83) |

| Krugluger et al, 2007 | Colorectal | Austria | Per1 expression in poorly differentiated tumors was significantly decreased, particularly in female patients | (84) |

| Wang et al, 2011 | Colorectal | China | Per2 expression was correlated with the degree of tumor differentiation, TNM stage and depth of infiltration | (85) |

| Mazzoccoli et al, 2011 | Colorectal | Italy | Per1 and Per3 were correlated with patients' survival time; Tim was correlated with TNM stage | (86) |

| Oshima et al, 2011 | Colorectal | Japan | High expression of BMAL1 and low expression of Per1 were correlated with liver metastasis; patients with high Per2 expression had a better prognosis | (87) |

| Wang et al, 2012 | Colorectal | China | Per3 was correlated with tumor differentiation, degree of differentiation and TNM stage; Per3-negative patients exhibited a higher mortality and shorter survival time | (88) |

| Karantanos et al, 2013 | Colorectal | China | High CLOCK expression was positively correlated with poor tumor differentiation, advanced stage and lymphatic metastasis | (89) |

| Wang et al, 2013 | Colorectal | China | High Cry1 expression was correlated with lymphatic metastasis, TNM stage and poor prognosis | (90) |

| Yu et al, 2013 | Colorectal | Greece | No association was observed between CLOCK, BMAL1 or Per1-3 and clinical parameters of colorectal cancer | (91) |

| Wang et al, 2015 | Colorectal | China | The expression of Per1 was significantly associated with distant metastasis, but not with patients' prognosis | (92) |

| Zhao et al, 2014 | Gastric | China | Per1 and Per2 were correlated with the clinical stage of gastric cancer and depth of infiltration; Per1 was also correlated with lymphatic metastasis and degree of pathological differentiation; patients with high Per2 expression had a better prognosis | (93) |

| Hu et al, 2014 | Gastric | Taiwan | High Cry1 expression was positively correlated with advanced gastric cancer | (94) |

| Relles et al, 2013 | Pancreatic | USA | Low expression of clock genes was associated with short survival time | (95) |

Per, period; TNM, tumor-node-metastasis; Tim, timeless; BMAL1, brain and muscle arylhydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator-like 1; CLOCK, circadian locomotor output cycles kaput; Cry, cryptochrome.

As shown in these tables, only a few articles focus on clock genes in abdominal tumors. The majority of them are single-center and small-sample studies, mainly focusing on colon cancer and genes such as CLOCK, BMAL1, Per1, Per2, Per3, Cry1, Cry2, CKIε and Tim, whereas only a few studies focus on NPAS2, Rev-Erb and DEC (83–91,93–95). Low expression of Per1 and Per3 in liver, colon and pancreatic cancer has been observed, and Per1 and Per3 are closely associated with prognosis (83–91,93–95) (Tables I and II).

Currently, the reason and mechanism of low expression of clock genes in abdominal tumors are not clear. Preliminary studies indicate that, in liver cancer, hypoxia, hypoxia inducible factor (HIF)-1α, HIF-2α and hepatitis B virus X protein (HBx) can disrupt the expression of circadian clock genes (83,96). Besides HBx, hepatitis C virus can also modulate the hepatic clock gene machinery (97). Therefore, it can be hypothesized that the tumor microenvironment and virus infections may contribute to circadian clock disorders in hepatocellular carcinoma cells (83,96).

The new interdiscipline generated by the integration of chronobiology and onco-molecular biology is expected to expand the knowledge about tumor occurrence and development, and may provide a new approach for tumor therapy (98–102). Tumor chronotherapy, which is the selection of the optimum treatment time to achieve the maximum curative effect and the minimum toxic and side effects based on the rhythm characteristics of tumor growth, has achieved satisfactory results in clinical practice (98–102). However, the association between clock genes and tumors remains to be fully understood. The circadian clock system of Drosophila is well understood, but this knowledge cannot be completely transferred to the human circadian clock, as this is more complex than that of Drosophila and large individual differences exist. Numerous factors in the natural and social environments that can influence the human circadian clock and the formation of tumors have not yet been fully elucidated. However, future findings in this field will lead to an increased knowledge in the disciplines of tumor and circadian clock research.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 81702885), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities: the Independent Innovation Fund of Huazhong University of Science and Technology (HUST: 2016YXMS241), Chinese Foundation for Hepatitis Prevention and Control ‘Tian Qing’ Liver Research Fund and China Postdoctoral Science Foundation funded project (2017M613001).

References

- 1.Montenegro-Montero A, Canessa P, Larrondo LF. Around the fungal clock: Recent advances in the molecular study of circadian clocks in neurospora and other fungi. Adv Genet. 2015;92:107–184. doi: 10.1016/bs.adgen.2015.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Endo M. Tissue-specific circadian clocks in plants. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2016;29:44–49. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2015.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Di Cara F, King-Jones K. How clocks and hormones act in concert to control the timing of insect development. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2013;105:1–36. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-396968-2.00001-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tomioka K. Chronobiology of crickets: A review. Zoolog Sci. 2014;31:624–632. doi: 10.2108/zs140024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Numata H, Miyazaki Y, Ikeno T. Common features in diverse insect clocks. Zoological Lett. 2015;1:10. doi: 10.1186/s40851-014-0003-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Uryu O, Ameku T, Niwa R. Recent progress in understanding the role of ecdysteroids in adult insects: Germline development and circadian clock in the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster. Zoological Lett. 2015;1:32. doi: 10.1186/s40851-015-0031-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heller HC, Ruby NF. Sleep and circadian rhythms in mammalian torpor. Annu Rev Physiol. 2004;66:275–289. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.66.032102.115313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ruby NF. Hibernation: When good clocks go cold. J Biol Rhythms. 2003;18:275–286. doi: 10.1177/0748730403254971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coomans CP, Ramkisoensing A, Meijer JH. The suprachiasmatic nuclei as a seasonal clock. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2015;37:29–42. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2014.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leslie M. Circadian rhythms. Sleep study suggests triggers for diabetes and obesity. Science. 2012;336:143. doi: 10.1126/science.336.6078.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bass J. Circadian topology of metabolism. Nature. 2012;491:348–356. doi: 10.1038/nature11704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Richards J, Diaz AN, Gumz ML. Clock genes in hypertension: Novel insights from rodent models. Blood Press Monit. 2014;19:249–254. doi: 10.1097/MBP.0000000000000060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McLoughlin SC, Haines P, FitzGerald GA. Clocks and cardiovascular function. Methods Enzymol. 2015;552:211–228. doi: 10.1016/bs.mie.2014.11.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Robinson I, Reddy AB. Molecular mechanisms of the circadian clockwork in mammals. FEBS Lett. 2014;588:2477–2483. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li S, Zhang L. Circadian control of global transcription. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:187809. doi: 10.1155/2015/187809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang N, Chelliah Y, Shan Y, Taylor CA, Yoo SH, Partch C, Green CB, Zhang H, Takahashi JS. Crystal structure of the heterodimeric CLOCK:BMAL1 transcriptional activator complex. Science. 2012;337:189–194. doi: 10.1126/science.1222804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cho H, Zhao X, Hatori M, Yu RT, Barish GD, Lam MT, Chong LW, DiTacchio L, Atkins AR, Glass CK, et al. Regulation of circadian behaviour and metabolism by REV-ERB-α and REV-ERB-β. Nature. 2012;485:123–127. doi: 10.1038/nature11048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bersten DC, Sullivan AE, Peet DJ, Whitelaw ML. bHLH-PAS proteins in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13:827–841. doi: 10.1038/nrc3621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mazzoccoli G, Pazienza V, Vinciguerra M. Clock genes and clock-controlled genes in the regulation of metabolic rhythms. Chronobiol Int. 2012;29:227–251. doi: 10.3109/07420528.2012.658127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.King DP, Zhao Y, Sangoram AM, Wilsbacher LD, Tanaka M, Antoch MP, Steeves TD, Vitaterna MH, Kornhauser JM, Lowrey PL, et al. Positional cloning of the mouse circadian clock gene. Cell. 1997;89:641–653. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80245-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Steeves TD, King DP, Zhao Y, Sangoram AM, Du F, Bowcock AM, Moore RY, Takahashi JS. Molecular cloning and characterization of the human CLOCK gene: Expression in the suprachiasmatic nuclei. Genomics. 1999;57:189–200. doi: 10.1006/geno.1998.5675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Naylor E, Bergmann BM, Krauski K, Zee PC, Takahashi JS, Vitaterna MH, Turek FW. The circadian clock mutation alters sleep homeostasis in the mouse. J Neurosci. 2000;20:8138–8143. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-21-08138.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee J, Lee S, Chung S, Park N, Son GH, An H, Jang J, Chang DJ, Suh YG, Kim K. Identification of a novel circadian clock modulator controlling BMAL1 expression through a ROR/REV-ERB-response element-dependent mechanism. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2016;469:580–586. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ikeda M, Nomura M. cDNA cloning and tissue-specific expression of a novel basic helix-loop-helix/PAS protein (BMAL1) and identification of alternatively spliced variants with alternative translation initiation site usage. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;233:258–264. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bunger MK, Wilsbacher LD, Moran SM, Clendenin C, Radcliffe LA, Hogenesch JB, Simon MC, Takahashi JS, Bradfield CA. Mop3 is an essential component of the master circadian pacemaker in mammals. Cell. 2000;103:1009–1017. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)00205-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Young ME, Brewer RA, Peliciari-Garcia RA, Collins HE, He L, Birky TL, Peden BW, Thompson EG, Ammons BJ, Bray MS, et al. Cardiomyocyte-specific BMAL1 plays critical roles in metabolism, signaling, and maintenance of contractile function of the heart. J Biol Rhythms. 2014;29:257–276. doi: 10.1177/0748730414543141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kennaway DJ, Varcoe TJ, Voultsios A, Boden MJ. Global loss of bmal1 expression alters adipose tissue hormones, gene expression and glucose metabolism. PLoS One. 2013;8:e65255. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rudic RD, McNamara P, Curtis AM, Boston RC, Panda S, Hogenesch JB, Fitzgerald GA. BMAL1 and CLOCK, two essential components of the circadian clock, are involved in glucose homeostasis. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:e377. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khapre RV, Kondratova AA, Patel S, Dubrovsky Y, Wrobel M, Antoch MP, Kondratov RV. BMAL1-dependent regulation of the mTOR signaling pathway delays aging. Aging (Albany NY) 2014;6:48–57. doi: 10.18632/aging.100633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ali AA, Schwarz-Herzke B, Stahr A, Prozorovski T, Aktas O, von Gall C. Premature aging of the hippocampal neurogenic niche in adult Bmal1-deficient mice. Aging (Albany NY) 2015;7:435–449. doi: 10.18632/aging.100764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Konopka RJ, Benzer S. Clock mutants of Drosophila melanogaster. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1971;68:2112–2116. doi: 10.1073/pnas.68.9.2112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lengyel Z, Lovig C, Kommedal S, Keszthelyi R, Szekeres G, Battyáni Z, Csernus V, Nagy AD. Altered expression patterns of clock gene mRNAs and clock proteins in human skin tumors. Tumour Biol. 2013;34:811–819. doi: 10.1007/s13277-012-0611-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhao N, Yang K, Yang G, Chen D, Tang H, Zhao D, Zhao C. Aberrant expression of clock gene period1 and its correlations with the growth, proliferation and metastasis of buccal squamous cell carcinoma. PLoS One. 2013;8:e55894. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hsu CM, Lin PM, Lai CC, Lin HC, Lin SF, Yang MY. PER1 and CLOCK: Potential circulating biomarkers for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Head Neck. 2014;36:1018–1026. doi: 10.1002/hed.23402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cadenas C, van de Sandt L, Edlund K, Lohr M, Hellwig B, Marchan R, Schmidt M, Rahnenführer J, Oster H, Hengstler JG. Loss of circadian clock gene expression is associated with tumor progression in breast cancer. Cell Cycle. 2014;13:3282–3291. doi: 10.4161/15384101.2014.954454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu B, Xu K, Jiang Y, Li X. Aberrant expression of Per1, Per2 and Per3 and their prognostic relevance in non-small cell lung cancer. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:7863–7871. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Larkin JC, Woolford JL., Jr Molecular cloning and analysis of the CRY1 gene: A yeast ribosomal protein gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 1983;11:403–420. doi: 10.1093/nar/11.2.403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kume K, Zylka MJ, Sriram S, Shearman LP, Weaver DR, Jin X, Maywood ES, Hastings MH, Reppert SM. mCRY1 and mCRY2 are essential components of the negative limb of the circadian clock feedback loop. Cell. 1999;98:193–205. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81014-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhou YD, Barnard M, Tian H, Li X, Ring HZ, Francke U, Shelton J, Richardson J, Russell DW, McKnight SL. Molecular characterization of two mammalian bHLH-PAS domain proteins selectively expressed in the central nervous system. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:713–718. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.2.713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McNamara P, Seo SB, Rudic RD, Sehgal A, Chakravarti D, FitzGerald GA. Regulation of CLOCK and MOP4 by nuclear hormone receptors in the vasculature: A humoral mechanism to reset a peripheral clock. Cell. 2001;105:877–889. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00401-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yuan P, Wang S, Zhou F, Wan S, Yang Y, Huang X, Zhang Z, Zhu Y, Zhang H, Xing J. Functional polymorphisms in the NPAS2 gene are associated with overall survival in transcatheter arterial chemoembolization-treated hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Cancer Sci. 2014;105:825–832. doi: 10.1111/cas.12428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xue X, Liu F, Han Y, Li P, Yuan B, Wang X, Chen Y, Kuang Y, Zhi Q, Zhao H. Silencing NPAS2 promotes cell growth and invasion in DLD-1 cells and correlated with poor prognosis of colorectal cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;450:1058–1062. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.06.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rana S, Shahid A, Ullah H, Mahmood S. Lack of association of the NPAS2 gene Ala394Thr polymorphism (rs2305160:G>A) with risk of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15:7169–7174. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2014.15.17.7169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fish KJ, Cegielska A, Getman ME, Landes GM, Virshup DM. Isolation and characterization of human casein kinase I epsilon (CKI), a novel member of the CKI gene family. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:14875–14883. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.25.14875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Camacho F, Cilio M, Guo Y, Virshup DM, Patel K, Khorkova O, Styren S, Morse B, Yao Z, Keesler GA. Human casein kinase Idelta phosphorylation of human circadian clock proteins period 1 and 2. FEBS Lett. 2001;489:159–165. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(00)02434-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tsuchiya Y, Akashi M, Matsuda M, Goto K, Miyata Y, Node K, Nishida E. Involvement of the protein kinase CK2 in the regulation of mammalian circadian rhythms. Sci Signal. 2009;2:ra26. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee H, Chen R, Lee Y, Yoo S, Lee C. Essential roles of CKIdelta and CKIepsilon in the mammalian circadian clock. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:21359–21364. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906651106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bonnelye E, Vanacker JM, Desbiens X, Begue A, Stehelin D, Laudet V. Rev-erb beta, a new member of the nuclear receptor superfamily, is expressed in the nervous system during chicken development. Cell Growth Differ. 1994;5:1357–1365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lazar MA, Hodin RA, Darling DS, Chin WW. A novel member of the thyroid/steroid hormone receptor family is encoded by the opposite strand of the rat c-erbA alpha transcriptional unit. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:1128–1136. doi: 10.1128/MCB.9.3.1128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Crumbley C, Burris TP. Direct regulation of CLOCK expression by REV-ERB. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17290. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dardente H, Fustin JM, Hazlerigg DG. Transcriptional feedback loops in the ovine circadian clock. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol. 2009;153:391–398. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2009.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Crumbley C, Wang Y, Kojetin DJ, Burris TP. Characterization of the core mammalian clock component, NPAS2, as a REV-ERBalpha/RORalpha target gene. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:35386–35392. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.129288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Takeda Y, Kang HS, Angers M, Jetten AM. Retinoic acid-related orphan receptor gamma directly regulates neuronal PAS domain protein 2 transcription in vivo. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:4769–4782. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bugge A, Feng D, Everett LJ, Briggs ER, Mullican SE, Wang F, Jager J, Lazar MA. Rev-erbα and Rev-erbβ coordinately protect the circadian clock and normal metabolic function. Genes Dev. 2012;26:657–667. doi: 10.1101/gad.186858.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mazzoccoli G, Cai Y, Liu S, Francavilla M, Giuliani F, Piepoli A, Pazienza V, Vinciguerra M, Yamamoto T, Takumi T. REV-ERBα and the clock gene machinery in mouse peripheral tissues: A possible role as a synchronizing hinge. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2012;26:265–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bhargava A, Herzel H, Ananthasubramaniam B. Mining for novel candidate clock genes in the circadian regulatory network. BMC Syst Biol. 2015;9:78. doi: 10.1186/s12918-015-0227-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shen M, Kawamoto T, Yan W, Nakamasu K, Tamagami M, Koyano Y, Noshiro M, Kato Y. Molecular characterization of the novel basic helix-loop-helix protein DEC1 expressed in differentiated human embryo chondrocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;236:294–298. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fujimoto K, Shen M, Noshiro M, Matsubara K, Shingu S, Honda K, Yoshida E, Suardita K, Matsuda Y, Kato Y. Molecular cloning and characterization of DEC2, a new member of basic helix-loop-helix proteins. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;280:164–171. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.4133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Noshiro M, Furukawa M, Honma S, Kawamoto T, Hamada T, Honma K, Kato Y. Tissue-specific disruption of rhythmic expression of Dec1 and Dec2 in clock mutant mice. J Biol Rhythms. 2005;20:404–418. doi: 10.1177/0748730405280195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wu T, Ni Y, Zhuge F, Sun L, Xu B, Kato H, Fu Z. Significant dissociation of expression patterns of the basic helix-loop-helix transcription factors Dec1 and Dec2 in rat kidney. J Exp Biol. 2011;214:1257–1263. doi: 10.1242/jeb.052100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Honma S, Kawamoto T, Takagi Y, Fujimoto K, Sato F, Noshiro M, Kato Y, Honma K. Dec1 and Dec2 are regulators of the mammalian molecular clock. Nature. 2002;419:841–844. doi: 10.1038/nature01123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Li Y, Xie M, Song X, Gragen S, Sachdeva K, Wan Y, Yan B. DEC1 negatively regulates the expression of DEC2 through binding to the E-box in the proximal promoter. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:16899–16907. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300596200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Seino H, Wu Y, Morohashi S, Kawamoto T, Fujimoto K, Kato Y, Takai Y, Kijima H. Basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor DEC1 regulates the cisplatin-induced apoptotic pathway of human esophageal cancer cells. Biomed Res. 2015;36:89–96. doi: 10.2220/biomedres.36.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jinhua H, Zhao M, Wei S, Haitao Y, Yuwen W, Lili W, Wei L, Jian Y. Down regulation of differentiated embryo-chondrocyte expressed gene 1 is related to the decrease of osteogenic capacity. Curr Drug Targets. 2014;15:432–441. doi: 10.2174/1389450114666140102133719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.You J, Lin L, Liu Q, Zhu T, Xia K, Su T. The correlation between the expression of differentiated embryo-chondrocyte expressed gene l and oral squamous cell carcinoma. Eur J Med Res. 2014;19:21. doi: 10.1186/2047-783X-19-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bi H, Li S, Qu X, Wang M, Bai X, Xu Z, Ao X, Jia Z, Jiang X, Yang Y, Wu H. DEC1 regulates breast cancer cell proliferation by stabilizing cyclin E protein and delays the progression of cell cycle S phase. Cell Death Dis. 2015;6:e1891. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2015.247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sehgal A, Price JL, Man B, Young MW. Loss of circadian behavioral rhythms and per RNA oscillations in the Drosophila mutant timeless. Science. 1994;263:1603–1606. doi: 10.1126/science.8128246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mazzoccoli G, Laukkanen MO, Vinciguerra M, Colangelo T, Colantuoni V. A timeless link between circadian patterns and disease. Trends Mol Med. 2016;22:68–81. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2015.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Parent MÉ, El-Zein M, Rousseau MC, Pintos J, Siemiatycki J. Night work and the risk of cancer among men. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;176:751–759. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bhatti P, Cushing-Haugen KL, Wicklund KG, Doherty JA, Rossing MA. Nightshift work and risk of ovarian cancer. Occup Environ Med. 2013;70:231–237. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2012-101146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ijaz S, Verbeek J, Seidler A, Lindbohm ML, Ojajärvi A, Orsini N, Costa G, Neuvonen K. Night-shift work and breast cancer-a systematic review and meta-analysis. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2013;39:431–447. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.3371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhao L, Isayama K, Chen H, Yamauchi N, Shigeyoshi Y, Hashimoto S, Hattori MA. The nuclear receptor REV-ERBα represses the transcription of growth/differentiation factor 10 and 15 genes in rat endometrium stromal cells. Physiol Rep. 2016;4:pii:e12663. doi: 10.14814/phy2.12663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Canaple L, Kakizawa T, Laudet V. The days and nights of cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2003;63:7545–7552. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Schibler U. The daily timing of gene expression and physiology in mammals. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2007;9:257–272. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2007.9.3/uschibler. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kornmann B, Schaad O, Bujard H, Takahashi JS, Schibler U. System-driven and oscillator-dependent circadian transcription in mice with a conditionally active liver clock. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e34. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Walker JR, Hogenesch JB. RNA profiling in circadian biology. Methods Enzymol. 2005;393:366–376. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)93016-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Storch KF, Lipan O, Leykin I, Viswanathan N, Davis FC, Wong WH, Weitz CJ. Extensive and divergent circadian gene expression in liver and heart. Nature. 2002;417:78–83. doi: 10.1038/nature744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Panda S, Antoch MP, Miller BH, Su AI, Schook AB, Straume M, Schultz PG, Kay SA, Takahashi JS, Hogenesch JB. Coordinated transcription of key pathways in the mouse by the circadian clock. Cell. 2002;109:307–320. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00722-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.McCarthy JJ, Andrews JL, McDearmon EL, Campbell KS, Barber BK, Miller BH, Walker JR, Hogenesch JB, Takahashi JS, Esser KA. Identification of the circadian transcriptome in adult mouse skeletal muscle. Physiol Genomics. 2007;31:86–95. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00066.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kornmann B, Preitner N, Rifat D, Fleury-Olela F, Schibler U. Analysis of circadian liver gene expression by ADDER, a highly sensitive method for the display of differentially expressed mRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:E51–E61. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.11.e51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Duffield GE, Best JD, Meurers BH, Bittner A, Loros JJ, Dunlap JC. Circadian programs of transcriptional activation, signaling, and protein turnover revealed by microarray analysis of mammalian cells. Curr Biol. 2002;12:551–557. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(02)00765-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lin YM, Chang JH, Yeh KT, Yang MY, Liu TC, Lin SF, Su WW, Chang JG. Disturbance of circadian gene expression in hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol Carcinog. 2008;47:925–933. doi: 10.1002/mc.20446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yang SL, Yu C, Jiang JX, Liu LP, Fang X, Wu C. Hepatitis B virus X protein disrupts the balance of the expression of circadian rhythm genes in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncol Lett. 2014;8:2715–2720. doi: 10.3892/ol.2014.2570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Krugluger W, Brandstaetter A, Kállay E, Schueller J, Krexner E, Kriwanek S, Bonner E, Cross HS. Regulation of genes of the circadian clock in human colon cancer: Reduced period-1 and dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase transcription correlates in high-grade tumors. Cancer Res. 2007;67:7917–7922. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wang Y, Hua L, Lu C, Chen Z. Expression of circadian clock gene human Period2 (hPer2) in human colorectal carcinoma. World J Surg Oncol. 2011;9:166. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-9-166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Mazzoccoli G, Panza A, Valvano MR, Palumbo O, Carella M, Pazienza V, Biscaglia G, Tavano F, Di Sebastiano P, Andriulli A, Piepoli A. Clock gene expression levels and relationship with clinical and pathological features in colorectal cancer patients. Chronobiol Int. 2011;28:841–851. doi: 10.3109/07420528.2011.615182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Oshima T, Takenoshita S, Akaike M, Kunisaki C, Fujii S, Nozaki A, Numata K, Shiozawa M, Rino Y, Tanaka K, et al. Expression of circadian genes correlates with liver metastasis and outcomes in colorectal cancer. Oncol Rep. 2011;25:1439–1446. doi: 10.3892/or.2011.1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wang X, Yan D, Teng M, Fan J, Zhou C, Li D, Qiu G, Sun X, Li T, Xing T, et al. Reduced expression of PER3 is associated with incidence and development of colon cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:3081–3088. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2279-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Karantanos T, Theodoropoulos G, Gazouli M, Vaiopoulou A, Karantanou C, Lymberi M, Pektasides D. Expression of clock genes in patients with colorectal cancer. Int J Biol Markers. 2013;28:280–285. doi: 10.5301/jbm.5000033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wang L, Chen B, Wang Y, Sun N, Lu C, Qian R, Hua L. hClock gene expression in human colorectal carcinoma. Mol Med Rep. 2013;8:1017–1022. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2013.1643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Yu H, Meng X, Wu J, Pan C, Ying X, Zhou Y, Liu R, Huang W. Cryptochrome 1 overexpression correlates with tumor progression and poor prognosis in patients with colorectal cancer. PLoS One. 2013;8:e61679. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Wang Y, Xing T, Huang L, Song G, Sun X, Zhong L, Fan J, Yan D, Zhou C, Cui F, et al. Period 1 and estrogen receptor-beta are downregulated in Chinese colon cancers. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:8178–8188. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Zhao H, Zeng ZL, Yang J, Jin Y, Qiu MZ, Hu XY, Han J, Liu KY, Liao JW, Xu RH, Zou QF. Prognostic relevance of period1 (Per1) and period2 (Per2) expression in human gastric cancer. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:619–630. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hu ML, Yeh KT, Lin PM, Hsu CM, Hsiao HH, Liu YC, Lin HY, Lin SF, Yang MY. Deregulated expression of circadian clock genes in gastric cancer. BMC Gastroenterol. 2014;14:67. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-14-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Relles D, Sendecki J, Chipitsyna G, Hyslop T, Yeo CJ, Arafat HA. Circadian gene expression and clinicopathologic correlates in pancreatic cancer. J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;17:443–450. doi: 10.1007/s11605-012-2112-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Yu C, Yang SL, Fang X, Jiang JX, Sun CY, Huang T. Hypoxia disrupts the expression levels of circadian rhythm genes in hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol Med Rep. 2015;11:4002–4008. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2015.3199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Benegiamo G, Mazzoccoli G, Cappello F, Rappa F, Scibetta N, Oben J, Greco A, Williams R, Andriulli A, Vinciguerra M, Pazienza V. Mutual antagonism between circadian protein period 2 and hepatitis C virus replication in hepatocytes. PLoS One. 2013;8:e60527. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kondratov R. Circadian clock and cancer therapy: An unexpected journey. Ann Med. 2014;46:189–190. doi: 10.3109/07853890.2014.920213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Innominato PF, Roche VP, Palesh OG, Ulusakarya A, Spiegel D, Lévi FA. The circadian timing system in clinical oncology. Ann Med. 2014;46:191–207. doi: 10.3109/07853890.2014.916990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Akgun Z, Saglam S, Yucel S, Gural Z, Balik E, Cipe G, Yildiz S, Kilickap S, Okyar A, Kaytan-Saglam E. Neoadjuvant chronomodulated capecitabine with radiotherapy in rectal cancer: A phase II brunch regimen study. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2014;74:751–756. doi: 10.1007/s00280-014-2558-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Zarogoulidis P, Darwiche K, Huang H, Spyratos D, Yarmus L, Li Q, Kakolyris S, Syrigos K, Zarogoulidis K. Time recall; future concept of chronomodulating chemotherapy for cancer. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2013;14:632–642. doi: 10.2174/13892010113146660229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Chen D, Cheng J, Yang K, Ma Y, Yang F. Retrospective analysis of chronomodulated chemotherapy versus conventional chemotherapy with paclitaxel, carboplatin, and 5-fluorouracil in patients with recurrent and/or metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Onco Targets Ther. 2013;6:1507–1514. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S53098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]