Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Some of the excitatory neurotransmitters including glutamate have been suggested to be involved in headache pathophysiology. To our knowledge, there is a lack of publication about flunarizine efficacy in chronic tension-type headache (CTTH) treatments and the roles of glutamate in CTTH pathophysiology.

AIM:

This study aimed to investigate the flunarizine effect on serum levels of glutamate and its correlation with headache intensity based on the Numeric Rating Scale for pain (NRS) scores in CTTH patients.

METHOD:

In a prospective randomised, double-blind study with pre and post-test design, seventy-three CTTH patients were randomly allocated with flunarizine 5 mg, flunarizine 10 mg and amitriptyline 12.5 mg groups. The serum levels of glutamate and NRS scores were measured before and after 15-day treatment.

RESULTS:

Flunarizine 5 mg was more effective than flunarizine 10 mg and amitriptyline 12.5 mg in reducing serum glutamate levels, whereas amitriptyline 12.5 mg was the most effective in reducing headache intensity. There was found nonsignificant, but very weak negative correlation between headache intensity and serum glutamate levels after flunarizine 5 mg administration (r = -0.062; P = 0.385), nonsignificant very weak negative correlation after flunarizine 10 mg administration (r = -0.007; P = 0.488) and there was found a significant moderate positive correlation (r = 0.508; P = 0.007) between headache intensity and serum glutamate levels after amitriptyline 12.5 mg administration.

CONCLUSION:

Since there was no significant correlation found between serum glutamate and headache intensity after treatment with flunarizine, it is suggested that decreasing of headache intensity after flunarizine treatment occurred not through glutamate pathways in CTTH patients.

Keywords: flunarizine, glutamate, headache intensity, chronic tension-type headache

Introduction

Headache disorders are one of the most common problems seen in the medical practice. Among all types of headache disorders, tension-type headache (TTH) is the most frequent in adults. Epidemiological studies reveal that 20–30% of the Asian population suffer from TTH and the global prevalence of TTH in the adult population is 42% [1]. A hospital-based study in Indonesia reported the prevalence of episodic tension-type headache (ETTH) and chronic tension-type headache (CTTH) to be 31% and 24% respectively [2]. There are no helpful investigations in diagnosing TTH so that the definition relies exclusively on clinical symptoms [3]. According to the International Classification of Headache Disorders, third edition beta version (ICHD-3 beta), CTTH is defined as the occurrence of TTH at a frequency of ≥15 days per month, with typically bilateral, pressing, or tightening in quality, and of mild to moderate intensity, lasting hours to days, or unremitting. The pain does not worsen with routine physical activity but may be associated with mild nausea, photophobia, or phonophobia [4]. Despite its high prevalence and socioeconomic impact, our understanding of TTH pathogenesis is surprisingly limited. One proposed hypothesis is that nociception from pericranial muscles, sensitisation of pain transmission circuits at the trigeminal nucleus/dorsal horn, and dysregulation of central pain modulation have each been postulated to play a significant role in the pathophysiology of CTTH [5, 6].

Glutamate, like serotonin and dopamine, is a prominent neurotransmitter in the CNS that mediates fast excitatory synaptic neurotransmission via ionotropic and metabotropic receptors [7]. Glutamate is stored intracellularly inside synaptic vesicles where the concentration may be as high as 100 millimolar and is inactive until released into the synapse. Glutamate is believed to be required to activate the trigeminovascular system and central sensitisation. Glutamatergic receptors are the molecular mediators through which glutamate acts and are found in the trigeminovascular system and its structures. The activation of NMDA receptors by glutamate has been hypothesised to play a role in primary headache disorders. Pain perception in CTTH as one of primary headache disorders might be activated through these pathways. By blocking NMDA receptors and, therefore, inhibiting these pathways, memantine could prevent primary headaches [8]. Previous studies reported that plasma glutamate levels monitoring in migraine patients might serve as a biomarker of response to treatments and as an objective measure of disease status [9].

Flunarizine, a long-acting calcium channel blocker, was originally introduced in the 1970s for the treatment of occlusive vascular diseases. The mechanism of action of flunarizine in a migraine is unclear, although its calcium and dopaminergic antagonism may offer some insights into possible subcortical brain targets. It has been reported that flunarizine can also cause inhibition of transmission along the trigeminovascular system [10]. Several studies have demonstrated its efficacy in migraine prophylaxis in adults [11]. However, to our knowledge, there is lack of publications about its efficacy in CTTH treatment.

We aim to see the flunarizine effect on serum levels of glutamate and its correlation with headache intensity based on the Numeric Rating Scale for pain (NRS) scores in CTTH patients.

Materials and Methods

Subjects and procedures

We studied 73 subjects (Table 1) suffering from CTTH according to the International Classification of Headache Disorders, 2nd edition (ICHD-II) criteria [12]. Chronic tension-type headache patients were recruited among those attended the outpatient clinic of the Adam Malik General Hospital Medan, Puteri Hijau Hospital and Medan Johor Primary Health Center Medan, Indonesia, during April and August 2016. Seventy-three patients out of ninety-five initially recruited had completed the study protocol until the end of the study and 22 drop out. Of 22 subjects drop out, one female patient discontinued consuming the prophylactic drug given due to an allergic reaction; twenty-one of them did not come back for the second blood samples. They were randomly allocated into three interventional groups to receive one of the following drugs for 15 days (flunarizine 5 mg/day, flunarizine 10 mg/day and amitriptyline12.5 mg/day). We included both male and female patients, between 18-65 years old. We excluded CTTH patients receiving or having received a prophylactic treatment in the previous 4-weeks, patients with neurological deficits related to his/her headache, serious somatic or psychiatric diseases including depression, extrapyramidal disorders, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), bronchial asthma, heart failure, diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, malignancy, pregnancy, lactation and hypersensitive to flunarizine or amitriptyline.

Table 1.

Chronic tension-type headache patient characteristics

| Characteristics | All Patients | Flunarizine 5 mg group (N = 25) | Flunarizine 10 mg group (N=25) | Amitriptyline 12.5 mg group (N=23) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | 73 (100) | 25(34.2) | 25(34.2) | 23(31.5) |

| Gender | ||||

| Male (%) | 13 (17.8) | 4 (16) | 5 (20) | 4 (17.4) |

| Female (%) | 60 (82.2) | 21 (84) | 20 (80) | 19 (82.6) |

| Mean age ± S.D. (years) | 44.6 ± 13.47 | 41.56 ± 14.90 | 45.12 ± 12.17 | 47.35 ± 13.06 |

| Marital Status | ||||

| Married N(%) | 57 (78.1) | 17 (68) | 22 (88) | 18 (78.3) |

| Single N(%) | 16 (21.9) | 8 (32) | 3 (12) | 5 (21.7) |

| History of CTTH (years, mean ± S.D) | 4.78 ± 2.29 | 4.76 ± 2.33 | 4.80 ± 2.08 | 4.78 ± 2.56 |

| Psychiatric disorders | None | None | None | None |

N= number of patients; S.D = standard deviation; CTTH= chronic tension-type headache.

All subjects agreed to participate and signed informed consent voluntarily after receiving a detailed description of the study procedures and purposes. The study was approved by the Health Research Ethical Committee of North Sumatera/RSUP H Adam Malik Medan, c/o Medical School, Universitas Sumatera Utara. Patients’ characteristics were recorded by medical examination, and headache intensity was measured using the Numeric Rating Scale for Pain (NRS) scores. The NRS scores consist of 4 levels of pain perception (0 = no pain, 1-3 = mild pain, 4-7 = moderate pain and 8-10 = severe pain). Chronic tension-type headache patients were studied before and after 15-day treatment. Venous blood samples for the assay of glutamate concentration were taken after data collection completed.

Assay of glutamate

Blood samples were collected in vacutainer tubes. Serum separation was isolated by centrifugation at 1000 g over 15 minutes. The serum samples should always be pre-diluted 1:5 (100 µl serum + 400 µl water) and stored at 2-80C until the time of analysis.

Glutamate concentrations in serum samples were analysed using Glutamate ELISA Kit (KA1909-Abnova) according to manufacturers’ instructions and Chemwell 2910 analyser. There are three steps of the glutamate assay procedures: extraction, derivatisation and ELISA. Extraction procedures were performed manually, whereas derivatisation and ELISA were done robotically using Chemwell 2910 analyser. Limit of detection of Glutamate Elisa Kit (KA1909-Abnova) is 0.3 µg/ml or equals 2.04 µmol/L.

Data analysis

Serum glutamate levels and NRS scores before and after 15-days treatment were analysed by using T-test for paired data. Kruskal-Wallis test followed by post hoc analysis with Mann-Whitney test was used to determine the most significant treatment effects between groups. All data were expressed as mean ± S.D. P < 0.05 was considered to be significant

Results

Characteristics of CTTH patients in this study are based on sociodemographic characteristics that include gender, age, history of CTTH and psychiatric evaluation. Majority of patients were female, married and the mean history of CTTH (4.78 ± 2.29) years. None of the patients has a psychiatric disorder.

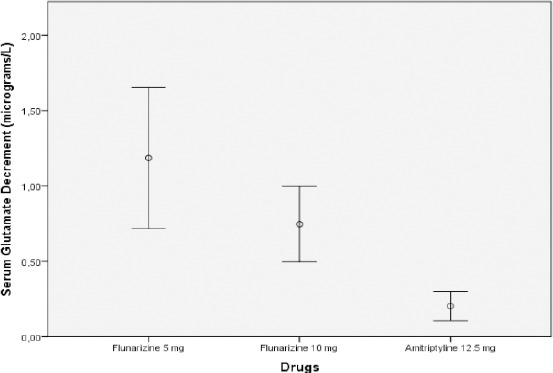

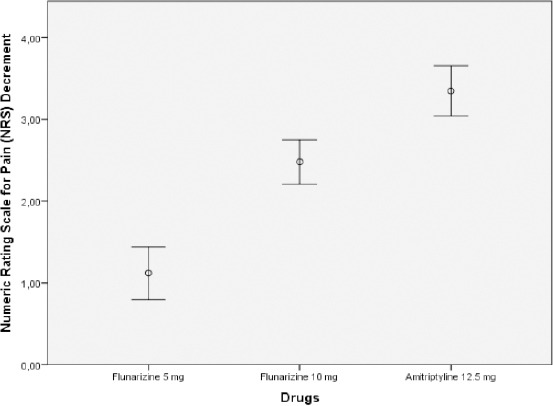

Both serum glutamate levels and NRS scores were significantly lower after 15 days treatment with 5 mg and 10 mg flunarizine as well as with 12.5 mg amitriptyline. Serum glutamate decrement levels continued to be significantly higher in flunarizine 5 mg group (1.19 ± 1.13 µg/L) than in flunarizine 10 mg group (0.75 ± 0.60 µg/L) and amitriptyline 12.5 mg group (0.20 ± 0.23 µg/L) (P < 0.001, Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Mann-Whitney post hoc testing). Decreased NRS score was found significantly in all three groups (flunarizine 5 mg, 1.12 ± 0.78 µg/L; flunarizine 10 mg, 2.48 ± 0.65 µg/L and amitriptyline 12.5 mg, 3.35 ± 0.71 µg/L) (P < 0.001, Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Mann-Whitney post hoc testing) compared before and after treatment (Table 2).

Table 2.

Serum concentration (Mean ± S.D.) of glutamate (μg/L) and NRS score

| Drugs | Serum Glutamate | P | NRS Score | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before | After | Before | After | |||

| Flunarizine | ||||||

| 5 mg | 12.04 ± 3.02 | 10.86 ± 2.89 | <0.001 | 4.64 ± 0.64 | 3.52 ± 0.65 | <0.001 |

| Flunarizine | ||||||

| 10 mg | 11.60 ± 2.38 | 10.86 ± 2.49 | <0.001 | 4.92 ± 0.57 | 2.44 ± 0.65 | <0.001 |

| Amitriptyline | ||||||

| 12.5 mg | 11.89 ± 1.76 | 11.69 ± 1.81 | <0.001 | 5.09 ± 0.51 | 1.74 ± 0.62 | <0.001 |

Before vs. after 15-day treatment: P < 0.05 (t - test for paired data)

The most significant decrement of NRS was found in amitriptyline 12.5 mg group, whereas the most decrement of serum glutamate concentration was found in flunarizine 5 mg group. (Figure 1 and Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Serum concentration decrement (Mean ± S.D.) of glutamate (µg/L) in CTTH patients, before and after 15-day of treatment

Figure 2.

Numeric Rating Scale for Pain (NRS Scores) decrement (mean ± S.D.) in CTTH patients, before and after 15-day treatment

After flunarizine 5 mg administration the NRS scores showed very weak negative and non-significant correlation (R = - 0.062; P = 0.385) with serum glutamate concentration.

The NRS scores also showed very weak negative and non-significant correlation (R = - 0.007; P = 0.488) after flunarizine 10 mg administration. Moderate positive correlation (R = 0.508; P = 0.007) was found between NRS scores and serum glutamate concentration after amitriptyline 12.5 mg administration (Table 3).

Table 3.

Correlation between NRS scores and serum Glutamate concentration (g/L) after treatment with Flunarizine 5 mg, Flunarizine 10 mg and Amitriptyline 12.5 mg

| NRS SCORE AFTER TREATMENT | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flunarizine 5 mg | Flunarizine 10 mg | Amitriptyline 12.5 mg | |||||||

| R | P | N | R | P | N | R | P | N | |

| Glutamate (g/L) | - 0.062 | 0.385 | 25 | - 0.007 | 0.488 | 25 | 0.508 | 0.007 | 23 |

NRS = Numeric Rating Scale for pain (Headache Intensity); r = correlation; P = significance; N = number of patients.

Discussion

In this study, the administration of flunarizine for 15 days was followed by a significant reduction of serum glutamate levels and headache intensity in CTTH patients. The relationship between the reduction of serum glutamate concentration and headache intensity after treatment with flunarizine in the present study was more likely an association than a causal one since there was no significant correlation found between serum glutamate levels and headache intensity in CTTH patients.

The mechanism which makes most prophylactic drugs effective in CTTH is not completely understood. Our results support the hypothesis that there might be a commonality or overlap of a signal barrage to the spinal or brainstem in chronic pain or chronic headache states. The glutamate system might be the point of amplification or reinforcement of the pain transmission cascade in these clinical conditions. Flunarizine, a calcium channel blocker, can cross blood brain barrier and could inhibit the release of glutamate just blocking the voltage-dependent calcium channel. It blocks calcium influx so that suppression of neuron hyper-excitability results in reducing headache intensity [6, 13, 14]. In this study, there were found significant reductions of serum glutamate levels followed by decreased headache intensity after flunarizine treatment. However, there was found non-significant very weak negative correlation (r = -0.062; P = 0.385) between serum glutamate and headache intensity. It revealed that decrease headache intensity after flunarizine treatment occurred not through the reduction of serum glutamate levels in CTTH patients. After amitriptyline treatment, there were found significant reductions of serum glutamate levels followed by decreased headache intensity. There was also found moderate positive correlations (r = 0.508; P = 0.007) between serum glutamate and headache intensity. It revealed that the decreased headache intensity after amitriptyline treatment might be related to serum glutamate reduction. Amitriptyline blocks the neuronal reuptake of serotonin and noradrenaline, although this is not the only mode of action of its antinociceptive properties. N-methyl- D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonism and blockade of muscarinic receptors and ion channels may play a role as well [15, 16].

Accumulated evidence has demonstrated that amitriptyline likely affects multiple receptors associated with pain modulation. For example, amitriptyline has been found to interact with opioids receptors, to inhibit the cellular uptake of adenosine, and to block N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors [15].

The reduction of serum glutamate levels after 15-day flunarizine treatment reveals that flunarizine influence the glutamatergic transmission in the pathogenesis of a tension-type headache. Although glutamate is thought not to readily cross the blood-brain barrier, the levels of glutamate in the blood are positively correlated with the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) levels of glutamate in humans. McGale et al. 1977 reported that the concentration of 13 amino acids in CSF had been shown to be directly related to the plasma concentration [17]. Alfredsson et.al. 1988 found that the serum and CSF levels of glutamate were positively correlated (R = 0.67, P < 0.05) [18]. Thus, the peripheral glutamate levels can be postulated to reflect the glutamate levels in the brain per se. In fact, increased plasma levels of glutamate have been reported in some neuropsychiatric disorders, such as epilepsy, Alzheimer’s disease and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, in which glutamate excitotoxicity is thought to play a role in the pathophysiology [19-21].

Our results have shown that decreased serum glutamate levels followed by reduction of headache intensity in the treatment with amitriptyline in CTTH patients. It is suggested that the reduction of headache intensity in CTTH patients after amitriptyline administration occurs through the pathway of decreasing serum glutamate since there was significant correlation found between serum glutamate levels and pain intensity in CTTH patients. Conversely, since there was no significant correlation found between serum glutamate and headache intensity after treatments with flunarizine, it is suggested that decreasing of headache intensity occur not through glutamate pathways. However, our data must be interpreted cautiously, considering the limited size of the sample.

Footnotes

Funding: This research did not receive any financial support.

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

References

- 1.Stovner LJ, Hagen K, Jensen R, Katsarava Z, Lipton RB, Scher A, et al. The global burden of headache:a documentation of headache prevalence and disability worldwide. Cephalalgia. 2007;27:193–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2007.01288.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2982.2007.01288.x PMid:17381554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sjahrir H. Nyeri Kepala. Vol. 1. Medan: USU Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sacco S, Ricci S, Carolei A. Tension-type Headache and Systemic Medical Disorders. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2011;15:438–443. doi: 10.1007/s11916-011-0222-2. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11916-011-0222-2 PMid:21861098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society. The International Classification of Headache Disorders:3rd edition. Cephalalgia. 2013;33(9):629–808. doi: 10.1177/0333102413485658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bendtsen L. Central sensitization in tension-type headache - possible pathophysiological mechanisms. Cephalalgia. 2000;20:486–508. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.2000.00070.x. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1468-2982.2000.00070.x PMid:11037746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen Y. Advances in the Pathophysiology of Tension-type Headache:From Stress to Central Sensitization. Current Pain & Headache Reports. 2009;13:484–494. doi: 10.1007/s11916-009-0078-x. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11916-009-0078-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gasparini CF, Smith RA, Griffiths LR. Biochemical Studies of the Neurotransmitter Glutamate:A Key Player in Migraine. Austin J Clin Neurol. 2015;2(9):1079. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang L, Bocek M, Jordan JK, Sheehan AH. Memantine for the Prevention of Primary Headache Disorders. Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 2014:1–5. doi: 10.1177/1060028014548872. https://doi.org/10.1177/1060028014548872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferrari A, Spaccapelo L, Pinetti D, Tacchi R, Bertolini A. Effective prophylactic treatments of migraine lower plasma glutamate levels. Cephalalgia. 2008;29:423–429. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2008.01749.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2982.2008.01749.x PMid:19170689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clauhan S, Devi P, Nidhi Pharmacological profile of flunarizine:A calcium channel blocker. International Journal of Innovative Pharmaceutical Sciences and Research. 2014;2(6):1260–1269. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mohammed BP, Goadsby PJ, Prabhakar P. Safety and efficacy of flunarizine in childhood migraine:11-year experience with emphasis on its hemiplegic migraine. 2011. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/J.1469-8749.2011.04152.x . [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache Society. The International Classification of headache Disorders. Cephalalgia. 2004;24(Suppl. 1):1–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2003.00824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cousin MD, Nicholls DG, Pocock JM. Flunarizine inhibits both calcium- dependent and -independent release of glutamate from synaptosomes and cultured neurones. Brain Research. 1993;606:227–236. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90989-z. https://doi.org/10.1016/0006-8993(93)90989-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kataki MS, Kumar KTMS, Rajkumari A. Neuropsycho-pharmacological Profiling of Flunarizine:A Calcium Channel Blocker. Int.J. PharmTech Res. 2010;2(3):1703–11713. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Su M, Liang L, and Yu S. Amitriptyline Therapy in Chronic Pain. Int Arch Clin Pharmacol. 2015;1(1):1–5. https://doi.org/10.23937/2572-3987.1510001. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tomkins GE, Jackson JL, O'Malley PG, Balden E, Santoro JE. Treatment of Chronic Headache with Antidepressants:A Meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2001;111:54–63. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(01)00762-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9343(01)00762-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McGale EH, Pye IF, Stonier C, Hutchinson EC, Aber GM. Studies of the inter- relationship between cerebrospinal fluid and plasma amino acid concentrations in normal individuals. J Neurochem. 1977;29:291–297. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1977.tb09621.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-4159.1977.tb09621.x PMid:886334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alfredsson G, Wiesel FA, Tylec A. Relationships between glutamate and monoamine metabolites in cerebrospinal fluid and serum in healthy volunteers. Biol Psychiatry. 1988;23:689–697. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(88)90052-2. https://doi.org/10.1016/0006-3223(88)90052-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martinez M, Frank A, Diez-Tejedar E, Hernanz A. Amino acids concentration in cerebrospinal fluid and serum in Alzheimer disease and vascular dementia. J Neural Transm [P-D Sect] 1993;6:1–9. doi: 10.1007/BF02252617. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02252617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rainesalo S, Keränen T, Palmio J, Peltola J, Oja SS, Saransaari P. Plasma and Cerebrospinal Fluid Amino Acids in Epileptic Patients. Neurochemical Research. 2004;29(1):319–324. doi: 10.1023/b:nere.0000010461.34920.0c. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:NERE.0000010461.34920.0c PMid:14992292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ilzecka J, Stelmasiak Z, Solski J, Wawrzycki S, Szpetnar M. Plasma amino acids concentration in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients. Amino Acids. 2003;25:69–73. doi: 10.1007/s00726-002-0352-2. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00726-002-0352-2 PMid:12836061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]