Abstract

The Chicago Follow-up Study has followed the course of severe mental illness among psychiatric patients for over 20 years after their index hospitalization. Among these patients are 97 schizophrenia patients, 45 patients with schizoaffective disorders, 102 patients with unipolar nonpsychotic depression, and 53 patients with a bipolar disorder. Maximum suicidal activity (suicidal ideation, suicidal attempts and suicide completions) generally declines over the three time periods (early, middle, and late follow-ups) following discharge from the acute psychiatric hospitalization for both males and females across diagnostic categories with two exceptions: female schizophrenia patients and female bipolar patients. A weighted mean suicidal activity score tended to decrease across follow-ups for male patients in the schizophrenia, schizoaffective and depressive diagnostic groups with an uneven trend in this direction for the male bipolars. No such pattern emerges for our female patients except for female depressives. Males’ suicidal activity seems more triggered by psychotic symptoms and potential chronic disability while females’ suicidal activity seems more triggered by affective symptoms.

Introduction

The Chicago Follow-up Study is a unique longitudinal study following the course of severe mental illness among initially hospitalized patients for over 20 years (Harrow, Grossman, Jobe & Herbener, 2005; Harrow, Jobe & Faull, 2012). As such it offers a unique opportunity to study the course of suicidality (suicidal ideation, suicidal attempts and completed suicides) over a significant part of one’s life span.

In an initial series of studies, Kaplan and Harrow (1996, 1999) explored whether risk factors for suicidal activity were general across diagnoses or whether they were diagnosis-specific. We should comment briefly on our measurement of “suicidal activity.” In some ways, suicide ideation, suicide attempts, and suicide represent discrete variables. However, a continuum of suicidal activity is recognized in some of the main scales used in the field (Endicott & Spitzer, 1978; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 2002; Posner et al., 2011). Within a given sequence of events, suicide ideation, suicide attempts, and suicide completions do represent points on a continuum of severity, with a positive score on a more severe index almost by definition requiring a positive score on a less severe index. We will discuss this issue in more detail in the Methods section.

Kaplan and Harrow (1996, 1999) prospectively followed 70 patients diagnosed with schizophrenia, 35 patients diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder, and 97 patients diagnosed with non-psychotic depression at index hospitalization and at periodic follow-ups. Positive symptoms, negative symptoms, and post-hospital functioning were assessed at a 2-year follow-up; suicidal activity was assessed at the 7.5-year follow-up. The results of this study support an interactive model of suicide risk. Adequacy of overall functioning predicted later suicidal activity for all three diagnostic groups. Psychotic symptoms (i.e., hallucinations, delusions) predicted later suicidal activity (completions, attempts and ideation) for the schizophrenia and schizoaffective patients. However, there is one difference. Psychotic symptoms remained a risk factor for later suicidal activity for schizoaffective patients even when functioning is partialled out. This is in contrast to the schizophrenia patients, for whom functioning seems to mediate the effects of psychosis on later suicidal activity. Cognitive symptoms (processing speed, concreteness) predicted later suicidal activity only for the depressive group.

The differential rate of suicidal activity has been established in the demographic statistics described previously. What made the Kaplan and Harrow (1996, 1999) study unique was the study of some differential risk factors for suicidal activity for schizophrenia, schizoaffective and non-psychotic depressive patients (see Hendin, 1986).

A recent study by our research team (Kaplan, Harrow & Faull, 2012) addressed this question. Seventy-four schizophrenia patients (51 men, 23 women) and 77 unipolar nonpsychotic depressed patients (26 men, 51 women) from our Chicago Follow-up Study were studied prospectively at 2 years post-index hospitalization and again at 7.5 years. Poor early post-index hospital global functioning was significantly associated with later suicidal activity only for men. Early display of psychotic symptoms was associated with later suicidal activity among male schizophrenia patients. Early cognitive impairment was not significantly associated with later suicidal activity.

These above studies have focused on the predictive effects of psychiatric risk factors at the first post-hospital follow-up (2 years post-hospitalization) on suicidal activity (suicidal ideation, suicide attempts and completed suicides) at the third post-hospital follow-up (7.5 years post-hospitalization).

What has not yet been addressed is a description of the full longitudinal course of suicidal activity across twenty years, including six follow-ups (2 years, 4.5 years, 7.5 years, 10 years, 15 years, and 20 years post-hospitalization). The present study addresses these issues across four diagnostic groups: male and female patients diagnosed with schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, non-psychotic unipolar depression, and bipolar disorder. Specifically, we ask the following questions:

Is there a gender difference in suicidal activity within and across diagnostic categories?

Does suicidal activity increase or decrease across the six follow-ups over 20 years? Is there a gender difference and diagnostic difference in this regard?

Methods

Subjects

The total of 97 schizophrenia patients (66 men and 31 women), 45 patients with schizoaffective disorders (24 men and 21 women), 102 patients with unipolar nonpsychotic depression (37 men and 65 women) and 53 bipolar patients (24 men and 29 women) from the Chicago Follow-up Study (Harrow, Grossman, Jobe, & Herbener, 2005; Harrow & Jobe, 2007, 2010; Kaplan & Harrow, 2007) and a closely associated research program (Grossman et. al. 1984). The RDC diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder is similar to that of the ICD-10 (World Health Organization, 1992) diagnosis, with both diagnoses requiring the simultaneous presence of pronounced mood disorders (or full affective syndromes) and psychotic schizophrenic symptoms. All bipolar patients had a full manic syndrome either in the current hospitalization or previously, and all unipolar depressive patients had a full depressive syndrome without a current or previous manic syndrome.

Patients were studied prospectively while in the hospital and then followed up at six periodic intervals over 20 years (at 2 years (F1), 4.5 years (F2), 7.5 years (F3), 10 years (F4), 15 years (F5), and 20 years (F6) post initial hospitalization). Our total sample included 164 instances of suicide ideation (72 males, 92 females), 49 instances of suicide attempts (15 males, 34 females), and 30 cases of suicide completions (17 males, 13 females). The entire group of patients represented a young, relatively early-phase sample of patients ranging in age at index hospitalization between 16 and 32 years, with a mean age of 23.4 years at index. 48.7 percent of the total sample were men and 51.3% were women. This ratio differed across diagnoses. About half of the sample (51%) was first admissions, and an additional 32% had only one or two hospitalizations prior to index hospitalization. The mean score for Social-Economic Status (using the Hollingshead-Redlich Five-Point Scale (Hollingshead & Redlich, 1958)) was 2.96.

Using the Research Diagnostic Criterion (RDC; (Spitzer, Endicott, & Robins, 1978)) the diagnosis for each patient was based on the information obtained from the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (SADS). The SADS is a structured research interview which was conducted with each subject during the period of index hospital admission (Endicott & Spitzer, 1978). Diagnosis also was based on information accrued from the Schizophrenia State Interview ESSII, a semi-structured tape-recorded interview (Grinker & Harrow, 1987), as well as detailed admission interviews summarized in the patient charts. Satisfactory inter-rater reliability for diagnosis was obtained (e.g., a kappa of 0.88 for patients diagnosed with schizophrenia).

Measures of Suicidal Activity at Follow-ups

In some ways, suicide ideation, suicide attempts, and suicide represent discrete variables. A subject was classified as showing suicidal activity at a given follow-up if he or she completed suicide, attempted suicide, or showed serious suicidal ideation in the period before each respective follow-up. The criterion for completed suicide was either: (1) report of suicide on a death certificate from an autopsy report or from the National Death Index or (2) the presence of both a family report of suicide and a method of death was likely to have been suicide. The criteria for attempted suicide was based on responses by the patients affirming suicide attempts to questions of the SADS (Schedule for Affective Disorder and Schizophrenia), such as “When a person gets upset, depressed, or feels hopeless, he may think about dying or even killing himself, have you?” (Endicott & Spitzer, 1978). These included a response scored a “7” (i.e., suicidal attempt with definite intent to die or potentially medically harmful) or scored a “6” (i.e., has made preparations for a potentially serious suicidal attempt). The criterion for serious suicidal ideation was based on a response of “5” (i.e., often thinks of suicide and has thoughts of or has mentally rehearsed a specific plan, often thinks of suicide or has thought of specific method) to the same question on the SADS. A certain percentage of people who die by suicide do so without ever having attempted suicide. Thus, suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and suicide completions can be treated as discrete variables.

Nevertheless, a continuum of suicidal activity is recognized in some of the main scales used in the field (Endicott & Spitzer, 1978; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 2002; Posner et. al., 2011). Posner et. al. (2011) report that worst-point suicide ideation on the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS) predicted suicide attempts. Within a given sequence of events, suicide ideation, suicide attempts, and suicide completions do represent points on a continuum of severity, with a positive score on a more severe index almost by definition requiring a positive score on a less severe index. For example, within a specific behavioral sequence, one must first attempt suicide in order to complete suicide. In other words, within that particular suicidal sequence, a suicide represents a concluded suicide attempt. Likewise, within that sequence of actions, an attempted suicide represents a concretized suicide ideation.

Our total sample of suicidal activity included 164 instances of suicide ideation (72 males, 92 females), 49 instances of suicide attempts (15 males, 34 females), and 29 cases of suicide completions (17 males, 12 females). It is important to mention that since each patient was assessed at multiple follow-ups over the years, the total number of individuals who qualified as having either suicidal ideation or as making a suicide attempt is not mutually exclusive, therefore those who endorsed having suicidal ideation or a suicide attempt or a combination of both at several follow-ups were counted as multiple occurrences of suicidal ideation.

We performed two types of analyses to examine the differential trajectories of suicidal activity by diagnosis and gender across the six follow-ups over twenty years. First, we categorized the follow-ups into three distinct time periods. The early time period was defined as either the 2 year (F1) or 4.5 year (F2) follow-up, the middle time period was defined as either the 7.5 year (F3) or 10 year (F4) follow-up, and the late time period was defined as either the 15 year (F5) or 20 year (F6) follow-up. We then specified the follow-up category at which the maximum suicide score occurred for each patient.

However, a sizeable percentage of patients from the sample did not fit into these categories. More specifically, those with consistent suicide scores across follow-ups and those with a bimodal occurrence of highest suicide score could not be included in this section of our analysis. Therefore we conducted a second analysis in which we generated and analyzed the weighted mean index of suicidal activity for each diagnostic category and for both genders at each follow-up. In this weighted mean, “suicide completion” was scored 4, “suicide attempt” was scored 3, a “suicidal ideation” was scored 2 and “no suicidal activity” was scored 1. Past research supports the validity of using this overall index of suicidal activity for these analyses (Kaplan, Harrow, and Faull, 2012).

Results

1: Is there a gender difference in suicidal activity within and across diagnostic categories?

We first examined whether gender differences in suicidal activity emerged between the four diagnostic categories. We compared the percentage of male and female patients who showed suicidal activity at any of the six follow-ups within each diagnostic category. Over all diagnoses, 44.4% of men and 50.0% of women showed some suicidal activity (suicidal ideation, suicide attempt, or suicide completion) over the twenty year period. The overall patterns are presented in Tables 1 and 2.

TABLE 1.

SUICIDAL BEHAVIOR ACROSS 6 FOLLOWUPS MALES

| 2.5 Year Followup N (%) | 4.5 Year Followup N (%) | 7.5 Year Followup N (%) | 10 Year Followup N (%) | 15 Year Followup N (%) | 20 Year Followup N (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suicide Completions | ||||||

| Schizophrenia Patients | 6 (10.5%) | 4 ( 7.3%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (2.8%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Schizoaffective Patients | 3 (13.6%) | 0 (0.0 %) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Nonpsychotic Depressive Patients | 1 (3.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Bipolar Patients | 1 (4.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (4.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Suicide Attempts | ||||||

| Schizophrenia Patients | 2 (3.5%) | 1 (1.8%) | 1 (2.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (2.9%) |

| Schizoaffective Patients | 2 (9.1%) | 1 (5.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (5.9%) | 1 (6.7%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Nonpsychotic Depressive Patients | 3 (9.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Bipolar Patients | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Suicidal Ideation | ||||||

| Schizophrenia Patients | 5 (8.8%) | 4 (7.3%) | 8 (17.8%) | 9 (20.0%) | 2 (5.6%) | 3 (8.6%) |

| Schizoaffective Patients | 1 (4.5%) | 4 (22.2%) | 5 (33.3%) | 4 (23.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (6.7%) |

| Nonpsychotic Depressive Patients | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (12.1%) | 3 (11.5%) | 2 (6.3%) | 1 (3.4%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Bipolar Patients | 3 (13.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (14.3%) | 1 (4.8%) | 2 (13.3%) | 1 (6.7%) |

| No Suicidal Activity | ||||||

| Schizophrenia Patients | 44 (77.2%) | 51 (83.6%) | 36 (80.0%) | 36 (80.0%) | 37 (91.7%) | 32 (88.6%) |

| Schizoaffective Patients | 16 (72.7%) | 13 (72.2%) | 10 (66.7%) | 12 (70.6%) | 14 (93.3%) | 14 (93.3%) |

| Nonpsychotic Depressive Patients | 28 (87.5%) | 29 (87.9%) | 23 (88.5%) | 30 (93.8%) | 28 (96.6%) | 26 (100%) |

| Bipolar Patients | 19 (82.6%) | 21 (100%) | 18 (85.7%) | 19 (90.5%) | 13 (86.7%) | 14 (93.3%) |

TABLE 2.

SUICIDAL BEHAVIOR ACROSS 6 FOLLOWUPS FEMALES

| 2.5 Year Followup N (%) | 4.5 Year Followup N (%) | 7.5 Year Followup N (%) | 10 Year Followup N (%) | 15 Year Followup N (%) | 20 Year Followup N (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suicide Completions | ||||||

| Schizophrenia Patients | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (4.0%) | 1 (4.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (9.1%) | 0 (0%) |

| Schizoaffective Patients | 1 (5.6%) | 1 (5.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Nonpsychotic Depressive Patients | 1 (1.8%) | 2 (3.8%) | 1 (1.9%) | 1 (1.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Bipolar Patients | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Suicide Attempts | ||||||

| Schizophrenia Patients | 1 (4.3%) | 2 (8.0%) | 1 (4.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Schizoaffective Patients | 1 (5.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Nonpsychotic Depressive Patients | 8 (14.0%) | 4 (7.7%) | 3 (5.7%) | 3 (5.6%) | 1 (2.3%) | 1 (2.9%) |

| Bipolar Patients | 1 (3.8%) | 1 (3.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (4.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Suicidal Ideation | ||||||

| Schizophrenia Patients | 3 (13.0%) | 3 (12.0%) | 4 (16.0%) | 3 (12.5%) | 4 (18.2%) | 2 (11.8%) |

| Schizoaffective Patients | 2 (11.1%) | 1 (5.3%) | 5 (33.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (8.3%) | 1 (8.3%) |

| Nonpsychotic Depressive Patients | 11 (19.3%) | 7 (13.5%) | 5 (9.4%) | 5 (9.3%) | 7 (16.3%) | 6 (17.1%) |

| Bipolar Patients | 4 (15.4%) | 1 (3.7%) | 1 (3.8%) | 4 (17.4%) | 4 (16.7%) | 1 (5.0%) |

| No Suicidal Activity | ||||||

| Schizophrenia Patients | 19 (82.6%) | 19 (76.0%) | 19 (76.0%) | 21 (87.5%) | 16 (72.7%) | 15 (88.2%) |

| Schizoaffective Patients | 14 (77.8%) | 17 (89.5%) | 10 (66.7%) | 14 (100.0%) | 11 (91.7%) | 11 (91.7%) |

| Nonpsychotic Depressive Patients | 50 (64.9%) | 39 (75.0%) | 44 (83.0%) | 45 (83.3%) | 35 (81.4%) | 28 (80.0%) |

| Bipolar Patients | 21 (80.8%) | 25 (92.6%) | 25 (96.2%) | 18 (78.3%) | 20 (83.3%) | 19 (95.0%) |

Overall Suicide Activity

Among schizophrenic patients, there was no difference in overall suicidal activity (suicidal ideation, suicide attempt, suicide completion) over the six follow-ups between males (53.0%) and females (51.6%). Among schizoaffective patients, a trend, though statistically nonsignificant, toward gender difference emerged; 62.5% of males showed suicidal activity, while only 42.9% of females showed suicidal activity, (Chi-Square= 1.74). Among non-psychotic depressive patients, a significant gender difference emerged in the opposite direction, females showed greater frequency of suicidal activity (58.5%) than males (24.3%), (Chi-Square=11.06, p<01). Among bipolar patients, no significant gender differences emerged in overall suicidal activity (33.3% of males versus 34.5 % of females).

Suicide Completions

An important aspect of the data is that the pattern of completed suicides across the six follow-ups over twenty years also shows gender differences within and between the diagnostic groups. Among male schizophrenic patients, there was a significant difference between males and females regarding time of completed suicide. Ten of the 11 males completed suicides occurred within the first 4.5 years (F1 and F2) following index hospitalization. For female schizophrenia patients, in contrast, 4 of the 5 completed suicides occurred after the first 4.5 years following index hospitalization (between F3 and F6) (Chi Square= 8.04, 1 df, p<01). This significant trend was not found among the female depressives, 3 of the 5 completed suicides for females in the depressive group occurred within the first 4.5 years following index hospitalization (F1 and F2), as does the single completed suicide for males. This delayed suicide effect does not occur among either males or females in any our other two diagnostic groups. For schizoaffective patients, all completed suicides for males and females occurred within the first 4.5 years following index hospitalization. For the depressive patients, 3 of the 5 completed suicides occurred within the first 4.5 years after hospitalization as does the single completed suicide for males. No time effect emerges for the 2 suicides among the bipolar patients, both of which are male.

2: Does suicidal activity increase or decrease across the six follow-ups over 20 years? Is there a gender difference and diagnostic difference?

As we described in the Methods sections, we approached this second question utilizing two different techniques.

Analysis One: Maximum Suicidal Activity per Early, Middle and Late Follow-ups for Males and Females in the Four Diagnostic Groups

First, we examined whether the maximum suicidal activity score for the patients in this study occurred within the year before the early (2.0 or 4.5 years post-index hospitalization), the middle (7.5 or 10 years post-index hospitalization), or later (15 or 20 years post-index hospitalization) follow-up assessments. We should emphasize that this analysis only included patients whose scores fit into one of the above three groups.

Schizophrenia patients

The percentage of male schizophrenia patients with suicidal activity declined monotonically over time, 59% showing a maximum suicide score within the early two follow-up assessments,32% showed a maximum suicide score within the middle follow-ups, and 9% showed a maximum score within the last two follow-ups. Females did not show this trend. (See Figure 1a). It should be noted that a crossover trend emerged over time between males and females, where a higher percentage of males showed a maximum suicide score early (59% vs. 44%), and a higher percentage of females showed a maximum suicide score late (33% vs. 9%).

Figure 1.

Suicidal Activity Trajectories for Male and Female Patients

Schizoaffective patients

For schizoaffective patients, both males and females showed a downward monotonic slope in percentages; 50% of males showed their maximum suicide score within the early two follow-ups, 40% showed a maximum suicide score within the middle two follow-ups, and 10% showed a maximum suicide score within the last two follow-ups. For females, 50% showed a maximum suicide score within the early two follow-ups, 50% showed a maximum suicide score within the middle two follow-ups, and none showed a maximum suicide score within the late two follow-ups (See Figure 1b).

Non-psychotic depressive patients

For the depressive patients, the percentage of both males and females with suicidal activity also declined monotonically over time. For females, 65% showed a maximum suicide score within the early two follow-ups, 25% showed a maximum suicide score within the middle two follow-ups, and 10% showed a maximum suicide score within the last two follow-ups. For males, 80% showed a maximum suicide score within the early two follow-ups, 20% showed a maximum suicide score within the middle two follow-ups, and none showed a maximum suicide score within the late two follow-ups. (See Figure 1c).

Bipolar patients

For bipolar patients, males and females showed slight opposite patterns, with maximum suicidal activity declining mildly between the early and middle follow-ups for males and remaining constant for the later two follow-ups. For bipolar females, in contrast, maximum suicidal activity is lowest during the early two follow-ups and increases for the middle two and later two follow-ups. (see Figure 1d).

To summarize, maximum suicidal activity generally declines over the three time periods (early, middle, and late follow-ups) following discharge from the acute psychiatric hospitalization for males in our sample across all of our diagnostic groups. The pattern is more varied for females.

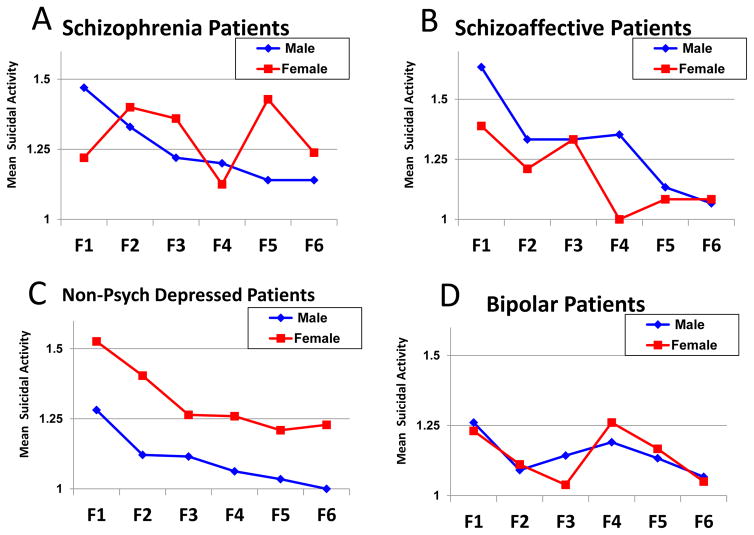

Analysis Two: Weighted Suicide Scores across the Six Follow-ups for Males and Females in the Four Diagnostic Groups

We conducted an alternative analysis in which we generated and analyzed a weighted mean index of suicidal activity for each diagnostic category and for both genders at each follow-up. In this weighted mean, a completed suicide was weighted 4 “suicide completion,” 3 “suicide attempt,” 2 “suicide ideation,” and 1 “no suicidal activity.” In other words, the higher the weighted mean, the higher the overall suicidality. Past research supports the validity of using this overall index of suicidal activity for these analyses (Kaplan, Harrow, and Faull, 2012).

Schizophrenia patients

As can be seen in Figure 2a, the weighted mean suicide score for male schizophrenia patients tended to decrease over all six follow ups (1.47 at the two-year follow-up and 1.14 at the twenty-year follow-up). These differences were accentuated by the high early suicide rate of male schizophrenic patients mentioned previously (10 of the 11 suicide completions). This trend did not occur for female schizophrenia patients.

Figure 2.

Mean Suicidal Activity for Male and Female Patients (NEW SAMPLE)

Schizoaffective patients

Similar to the male schizophrenia group, the weighted mean suicide score for male schizoaffective patients tended to decrease over all six follow ups from 1.63 at the two-year follow-up to 1.07 at the twenty year follow-up (see Figure 2b). The decline for the female schizoaffective group is less consistent.

Non-psychotic depressive patients

As can be seen in Figure 2c, the weighted mean suicide score for male depressive patients decreased significantly over time from 1.27 at the two-year follow-up to 0 at the twenty-year follow-up (t [2,81]=3.82, p=.00). The weighted mean score for female depressives decreased over the first three follow-ups and remained consistent afterwards. It is important to emphasize female depressive patients displayed a consistently higher weighted mean than males over the twenty years.

Bipolar patients

The smaller group of bipolar patients did not show a consistent trend for either males or females, though the weighed mean suicide score for both was lower at the 20-year follow-up than at the 2 year follow-up post-acute hospitalization.

To summarize, the weighted suicide score tended to decrease across follow-ups for male patients in the schizophrenia, schizoaffective and depressive diagnostic groups with an uneven trend in this direction for the male bipolar patients. No such pattern emerges for our female patients except for the female depressives.

Discussion

Why Does Severity of Suicidal Activity Decrease over Time after Index Hospitalization?

A major result of this study is that severity of suicidality decreases over time beginning with the period after acute hospitalization for male schizophrenia patents, and for male unipolar, non-psychotic depressive patients. In particular these data indicate that clinicians should be alerted that the risk of completed suicide for male schizophrenic patients is quite high during early phases of their disorders. As previously reported, 10 of the 11 completed suicides for male schizophrenic patients occurred within the first 4.5 years (F1 and F2) following index hospitalization; however, 4 of the 5 completed suicides for female patients occurred after the first 4.5 years following index hospitalization (between F3 and F6) (Chi Square= 8.04, 1 df, p<01). A decline of suicidal activity over time occurred for female depressive patients. These trends are consistent with previous literature that suggests suicide risk for psychiatric patients may be highest near index hospitalization or in early follow-ups after discharge and may decrease over time (Caldwell & Gottesman, 1990; Harkavy-Friedman, Tatarelli, Pompili, & Girardi, 2007; Qin & Nordendoft, 2005; Thong, Su, Chan, and Chia, 2008). However our data suggests that the rate of completed suicides for our female schizophrenic trend may not follow this pattern. It might be expected that suicidal activity for many diagnostic groups, whether completions, attempts, or ideation, would decrease following index hospitalization, given most individuals are at the most acute phase of their mental illness at time of hospitalization. With proper treatment we would expect suicidality to decrease.

Why is there a Difference in the Relative Proportion of Males and Females Showing Suicidal Activity Across Diagnostic Groups?

The difference in the relative proportion of males and females showing suicidal activity across diagnostic groups has important clinical implications. The greater preponderance of completed suicides among schizophrenic males as opposed to schizophrenic females was expected. However, the higher rate of nonlethal suicidal activity among our male schizophrenia and schizoaffective patients was unexpected, given the greater degree of nonlethal suicidal activity among females in the United States (Canetto & Sakinofsky, 1998).

Why, however should male schizophrenia and schizoaffective patients (schizophrenia spectrum patients) show a greater risk for suicidal activity than females and why should female non-psychotic depressive patients show greater suicidal risk than males? The reaction of females to depression may be one factor.

This question becomes more salient in our previous analysis of the pattern of completed suicide across the six follow-ups over twenty years. Our data showed that 10 of the 11 completed suicides for male schizophrenic patients occurred within the first 4.5 years, while 4 of the 5 completed suicides for female schizophrenic patients occurred after the 4.5 year follow-up (p<01). This late suicide pattern of the female schizophrenia patients stands in contrast with the early suicide pattern of female nonpsychotic depressive patients, for whom 3 of the 5 completed suicides occurred within the first 4.5 years following index hospitalization.

Why Are Psychotic Symptoms More of a Risk Factor for Suicidal Activity for Men, Why are Affective Symptoms More of a Risk Factor for Suicidal Activity for Women?

Is there something about the nature of a particular psychiatric disorder that is differentially linked to completed suicide for men and women? The mood component involved in non-psychotic depressive disorder may play a larger role in suicidal activity for females; however the psychotic component and the prospects of a long-term decrease in functioning involved in schizophrenia may play a larger role in suicidal activity for males. Generally, mood disorder may be a larger suicidal risk factor for females, and schizophrenia may be a larger suicidal risk factor for males. More females are diagnosed with depressive disorder and more males (especially younger males) are diagnosed with schizophrenia (Piccinelli & Wilkinson, 2000). When comparing data by percentages, males diagnosed with schizophrenia show greater suicidal activity than females (Caldwell & Gottesman, 1990). Our present data agrees with this trend, both with regard to completed suicide and overall suicidal activity. In contrast our data suggests that female depressive patients are at greater risk than male depressives for both completed suicide and overall suicidal activity.

A possible factor contributing to this for this may be the potentially differentiating implications of these diagnoses for this cohort’s generation. More men of this generation may have measured their worth largely in terms of economic success and social status in accordance with this view. Zhang et. al. (2005) reports that low income is associated with attempted suicide among men but not women while Stack (2000) reports evidence that unemployment increases male but not female suicide risk.

A diagnosis of psychosis and possible prospects of chronic disability may have initially shattered many males’ sense of self-worth and hopes for future success. However, over time, males who do not attempt suicide early may be more willing and/or able to adjust to their diminished life style, and therefore may be at lower risk for later suicide. In contrast, women diagnosed with a psychotic disorder may not have initially felt their lifestyle was as impaired, and may have seen their future status as more defined by their marriage partner, home and family life. Over time, the realization for some of these women that their psychosis hampered them in their quest for a secure family life may become more salient, and therefore increase their propensity for suicide. It is important to note, however, that affective impairment seems more detrimental to women early, as much of their psychological life may be more determined by their emotions. The data indicate that over time they may adjust more adequately to such an affective disturbance.

Limitations

A limitation of the present study is the moderate sample size. However, it is probably unrealistic to expect a larger sample in a group of patients studied longitudinally at multiple different time points over 20 years, and thus a study of suicidal activity over time. Another possible limitation is our use of the term “suicidal activity”, which may be somewhat unfamiliar to some readers. As we have used it, suicidal activity represents a weighted incremental index of severity of suicidal tendencies, varying from no suicidal ideation to suicidal ideation to suicide attempts to suicide completions. As such, it represents a summary index of suicidal tendencies, an issue which can be quite useful and important in a study of psychiatric patients.

Conclusions

Overall, this current data offers a portal into suicidal activity over 20 years following initial hospitalization for mental illness. Furthermore, it has allowed for differentiation of these effects for different diagnostic groups, for men and women among these diagnostic groups, and attempted analysis of suicidal ideation, suicidal attempts, and suicidal completion. The availability of a prospectively-designed twenty year follow-up study of suicidal activity allows one to ask questions regarding the time sequence of suicidal activity, especially suicide completions. Hopefully this study will alert clinicians to the differential vulnerabilities over time with regard to suicidal activity between males and females with different psychiatric diagnoses.

Acknowledgments

Supported, in part, by USPHS Grants MH-26341 and MH-068688 from the National Institute of Mental Health, USA (Dr. Harrow) and a grant from the Foundation for Excellence in Mental Health Care (Dr. Harrow).

Contributor Information

Kalman J. Kaplan, Professor of Clinical Psychology, Department of Psychiatry, University of Illinois College of Medicine, Chicago

Martin Harrow, Professor Emeritus, Department of Psychiatry, University of Illinois College of Medicine, Chicago

Kelsey Clews, Chicago School of Professional Psychology

References

- Caldwell CB, Gottesman II. Schizophrenics kill themselves too: A review of risk factors for suicide. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1990;16(4):571. doi: 10.1093/schbul/16.4.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canetto SS, Sakinofsky I. The gender paradox in suicide. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 1998;28(1):1–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endicott J, Spitzer R. A diagnostic interview. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1978;35:837–844. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1978.01770310043002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First M, Spitzer R, Gibbon M, et al. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV-TR axis I disorders, research version, patient edition. new york: Biometrics research, new york state psychiatric institute; 2002. (SCID-I/P) [Google Scholar]

- Grinker R, Harrow M, editors. Clinical research in schizophrenia: A multidimensional approach. Springfield IL: Thomas CC; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Grossman L, Harrow M, Fudala J, et al. The longitudinal course of schizoaffective disorders: A prospective followup study. journal of nervous and mental disease. 1984;172:140–149. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198403000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harkavy-Friedman J, Tatarelli R, Pompili M, et al. Depression and suicidal behavior in schizophrenia. Suicide in Schizophrenia. 2007:99–112. [Google Scholar]

- Harrow M, Grossman L, Jobe T, et al. Do patients with schizophrenia ever show periods of recovery?: A 15 year multi-followup study. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2005;31:723–734. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbi026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrow M, Jobe TH, Faull RN. Do all schizophrenia patients need antipsychotic treatment continuously throughout their lifetime? A 20-year longitudinal study. Psychological Medicine. 2012;42(10):2145–2155. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712000220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrow M, Jobe T. Factors involved in outcome and recovery in schizophrenia patients not on antipsychotic medications: A 15-year multi-followup study. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2007;195(5):406–414. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000253783.32338.6e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrow M, Jobe T. How frequent is chronic multiyear delusional activity and recovery in schizophrenia: A 20-year multi-followup. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2010;36:192–204. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendin H. Suicide: A review of new directions in research. Hospital & Community Psychiatry. 1986 doi: 10.1176/ps.37.2.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead A, Redlich F. Social class and mental illness. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan KJ, Harrow M. Positive and negative symptoms as risk factors for later suicidal activity in schizophrenics versus depressives. Suicide and Life Threatening Behavior. 1996;26:105–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan KJ, Harrow M. Psychosis and functioning as risk factors for later suicidal activity among schizophrenia and schizoaffective patients: An interactive model. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 1999;29:10–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan KJ, Harrow M, Faull R. Early positive and negative symptoms and poor functioning and later suicidal activity among schizophrenia, schizoaffective and depressive patients. In: Tatarelli R, Pompili M, Girardi P, editors. Suicide in psychiatric disorders. New York: Nova Publishers, Inc; 2007. pp. 57–76. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan KJ, Harrow M, Faull R. Are there Gender-Specific risk factors for suicidal activity among patients with schizophrenia and depression? Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2012;42(6):614–627. doi: 10.1111/j.1943-278X.2012.00116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piccinelli M, Wilkinson G. Gender differences in depression. critical review. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science. 2000;177:486–492. doi: 10.1192/bjp.177.6.486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner K, Brown GK, Stanley B, et al. The Columbia–Suicide severity rating scale: Initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2011;168(12):1266–1277. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10111704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin P, Nordentoft M. Suicide risk in relation to psychiatric hospitalization: Evidence based on longitudinal registers. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62(4):427. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.4.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Endicott J, Robins E. Research diagnostic criteria: Rationale and reliability. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1978;35:773–782. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1978.01770300115013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stack S. Suicide: A 15-Year review of the sociological literature part I: Cultural and economic factors. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2000;30(2):145–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thong JY, Su AH, Chan YH, et al. Suicide in psychiatric patients: Case-control study in Singapore. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;42(6):509–519. doi: 10.1080/00048670802050553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders: clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Mckeown RE, Hussey JR, et al. Gender differences in risk factors for attempted suicide among young adults: Findings from the third national health and nutrition examination survey. Annals of Epidemiology. 2005;15(2):167–174. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2004.07.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]