Abstract

Hindered O-tert-alkyl N-arylcarbamates were conveniently prepared by treating arylamines with aryl tert-alkyl carbonates in the presence of a strong base. The new method avoids the use of sensitive and difficult-to-access dialkyl dicarbonates and isocyanates, which are most commonly used in known methods. Instead, the stable and readily accessible alkyl aryl carbonates are used. Therefore, the new method is particularly suitable for the synthesis of N-arylcarbamates that contain a complex O-alkyl moiety. Using the method, electron-rich and electron-poor, and primary and secondary arylamines can all be conveniently converted to their carbamates with acceptable yields. The method was also found equally effective for the synthesis of the less hindered O-secondary and O-primary alkyl N-arylcarbamates.

Keywords: amines, carbamates, carbamylation, protecting groups, synthetic methods

Introduction

Carbamate is a common functionality that appears in numerous organic compounds including those that have various biological activities.1 It is also widely used as protecting groups in organic synthesis2 and as linkers in solid phase synthesis3 and bioconjugate chemistry.4 Carbamates can be synthesized using a variety of methods.5 Examples include linking an alcohol and amine with 1,1′-carbonyldiimidazole,6 carbonylation of an amine with dialkyl azodicarboxylate,7 addition of a hypochlorite to isocyanate,8 Curtius rearrangement,9 Hoffmann rearrangement,10 La(III)-catalyzed transesterification of methyl carbonates with alcohols,11 reaction of an amine with carbon dioxide followed by esterification,12 and reaction of an amine with a carbonate salt followed by esterification.13

Despite of the availability of many options, two methods are most widely used for the formation of carbamates. One of them involves using phosgene or triphosgene to link an amine and alcohol through the intermediate chloroformate or isocyanate.5b The major drawback of this method is the toxicity of phosgene and triphosgene although the latter is significantly safer. In addition, when the amine is electron deficient and the alcohol is hindered, the reaction may be slow, give low yield or even not work at all.14 In cases in which isocyanates are involved, in addition to an additional step to prepare the isocyanates, a catalyst and long reaction time are usually needed for the formation of hindered carbamates.15 The other method is to use dialkyl dicarbonates. Even the most hindered O-tertiary carbamate can be readily prepared using the method.16 Electron deficient arylamines are equally good substrates as electron rich ones although in some cases special means such as high temperature, long reaction time, catalysts and microwave irradiation were used for the former.17 The major drawback is the difficulty to prepare the dialkyl dicarbonates, which requires multiple step synthesis and involves using toxic phosgene or triphosgene.18 In addition, the product is moisture sensitive and thus difficult to purify by chromatography. Therefore, the method is only widely used to prepare O-tert-butyl-carbamates because the required di-tert-butyl dicarbonate (commonly called Boc anhydride) is commercially available.

Recently, we needed to protect the exo-amino groups of nucleoside analogues in the form of O-tert-alkyl-carbamate, in which the alkyl group was more complex than the butyl group. Possibly due to the steric hindrance of the tert-alkyl group, the sensitivity of the glycosidic bond under acidic conditions, and the low reactivity of exo-amino groups of nucleosides, known methods including those using triphosgene, isocyanates and 1,1′-carbonyldiimidazole all did not give the desired products. The method using dialkyl dicarbonate was not considered due to the difficulty to synthesize and purify the reagents. Therefore, we decided to develop a new method for the synthesis of carbamates that could be used to synthesize the most challenging O-tert-alkyl N-arylcarbamates.

Results and Discussion

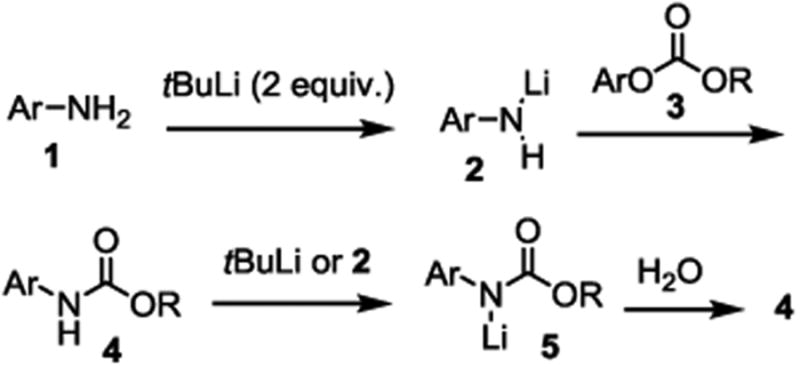

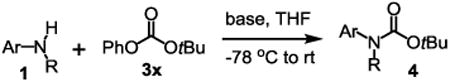

The new method involves reacting an arylamine with an alkyl aryl carbonate in the presence of a strong base to give the desired carbamate in one step. As shown in Scheme 1, the primary arylamine 1 is treated with two equivalents of a strong base such as tBuLi (the case for secondary amine is simpler and only one equivalent base is needed) to give the lithium arylamide 2, which reacts with the alkyl aryl carbonate 3 to give the carbamate product 4. What makes the reaction complicated is that the amide hydrogen in 4 becomes much more acidic than those in 1, and therefore 4 will undoubtedly react with tBuLi or 2 to give 5, and that is why two equivalents tBuLi is needed. With two equivalents tBuLi, 4 will likely react with tBuLi instead of 2. Even if 2 is reacted to give 1, it can be regenerated by deprotonating 1 with the remaining tBuLi. After the reaction is complete, product 4 is obtained when 5 is exposed to water. The advantages of this method for arylcarbamate formation can be easily seen from the Scheme. Amide 2 is a highly reactive species, which will overcome the problems caused be lower reactivity of arylamines compared with alkylamines. This is especially important with electron deficient arylamines. In addition, the stable alkyl aryl carbonates 3 (instead of phosgene or dialkyl dicarbonates) are used as the carbamylation reagents. These compounds can be easily prepared and purified. Further, due to the high reactivity of 2, the reaction is unlikely to be negatively affected by the steric hindrance of 3, and therefore is suitable for the formation of the most challenging O-tert-alkyl N-arylcarbamates.

Scheme 1. Formation of O-alkyl N-arylcarbamates using alkyl aryl carbonates under highly reactive conditions.

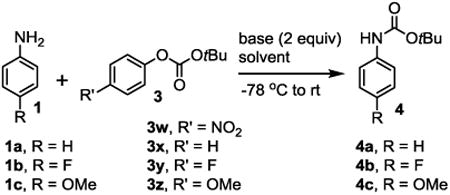

Even though our major goal is to develop a method for the synthesis of O-tert-alkyl N-arylcarbamates with the alkyl group more complex than the butyl group, at the initial stage of the study, we still used the butyl group because most of the O-tert-butyl arylcarbamates are known and therefore it was easier for us to monitor the reactions and identify the products. We first selected tert-butyl 4-nitrophenyl carbonate (3w) as the carbamylation reagent because 4-nitrophenoxide is a well-known good leaving group. Aniline (1a) was used as the arylamine substrate. We treated 1a with two equivalents of tBuLi in THF at −78 °C followed by adding one equivalent 3w. However, no desired product (4a) was obtained and the starting amine 1a was not significantly consumed (entry 1, Table 1). This was surprising because we were successful to carbamylate the exo-amino groups of nucleoside derivatives using a similar tert-alkyl 4-nitrophenyl carbonate under the same conditions with high yields.19 We carefully purified aniline with vacuum distillation and tested the reaction multiple times, still no product could be obtained. Because aniline is more electron rich than the nucleoside bases, we wondered if the less electron rich 4-fluoroaniline (1b) could be a suitable substrate for the reaction (entry 2). Indeed, under the same conditions, with 1b as substrate, the arylcarbamate 4b was obtained in 26% isolated yield. When the base was changed from tBuLi to LDA, similar positive results were obtained (entry 3).

Table 1.

Optimization of reaction conditions.a

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| entry | 1 | 3 | base | solvent | 4 | yield |

| 1 | 1a | 3w | tBuLi | THF | 4a | 0% |

| 2 | 1b | 3w | tBuLi | THF | 4b | 26% |

| 3 | 1b | 3w | LDA | THF | 4b | 23% |

| 4 | 1a | 3x | tBuLi | THF | 4a | 54% |

| 5 | 1b | 3x | tBuLi | THF | 4b | 35% |

| 6 | 1c | 3x | tBuLi | THF | 4c | 31% |

| 7 | 1a | 3x | LDA | THF | 4a | 23% |

| 8 | 1a | 3x | nBuLi | THF | 4a | 55% |

| 9 | 1a | 3x | sBuLi | THF | 4a | 54% |

| 10 | 1a | 3x | tBuLi | Et2O | 4a | 31% |

| 11 | 1a | 3x | tBuLi | 1,4-dioxane | 4a | <5% |

| 12 | 1a | 3x | tBuLi | PhMe | 4a | 71% |

| 13 | 1a | 3y | tBuLi | THF | 4a | 21% |

| 14 | 1a | 3z | tBuLi | THF | 4a | 36% |

Reaction conditions: 1 (1 equiv), 3 (1 equiv), base (2 equiv), solvent, −78 °C to rt, 12 h. Isolated yields were reported except for entries 1 and 11, in which cases the yields were estimated according to TLC.

One possible explanation for the above observations could be that the lithium amide 2 might be more reactive toward the electron deficient 4-nitrophenolic moiety of 3w through nucleophilic aromatic addition than toward the carbonyl group of 3w. The adduct prevented the desired reaction, and when the reaction mixture was exposed to water, aniline was regenerated. With this consideration, we used the carbonate 3x, in which the electron withdrawing nitro group was replaced with hydrogen. Indeed, with aniline (1a) as substrate, under the same reaction conditions, the desired product 4a was obtained in 54% yield (entry 4). We next tested if the carbonate 3x was suitable for carbamylation of electron deficient and electron rich arylamines. With 4-fluoroaniline (1b) and 4-methoxyaniline (1c) as substrates, the reactions worked well although the yields were modest (entries 5-6). To see if bases other than tBuLi could give better yields, LDA, nBuLi and sBuLi were screened. With 1a as the substrate, LDA gave lower yields while nBuLi and sBuLi gave similar yields compared to tBuLi (entries 7-9). For screening solvents, the reaction was carried out in diethyl ether, 1,4-dioxane and toluene using tBuLi as base and 1a as substrate, the yields were 31%, less than 5% and 71%, respectively (entries 10-12).

To see if carbonates other than 3w and 3x could be better carbamylation reagents for the reaction, 3y and 3z, in which the phenolic leaving group carries an electron withdrawing fluorine and an electron donating methoxy group, respectively, were tested. Under the similar conditions, the yields remained modest (entries 13-14). Among all the conditions screened, those for entry 12 gave the best yield (71%). However, considering that many substrates might not be soluble in toluene, and results might vary widely with different substrates, we still choose THF as the solvent for our substrate scope studies. For researchers who need to use the reaction, it is suggested to try the reaction in toluene as well. Therefore, our standard conditions for the new carbamylation reaction are to treat one equivalent primary arylamine with two equivalents nBuLi or tBuLi (for secondary amines, one equivalent only) and one equivalent carbonate in THF at −78 °C followed by warming to room temperature gradually.

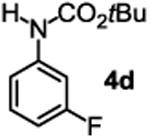

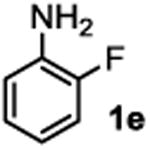

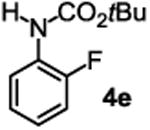

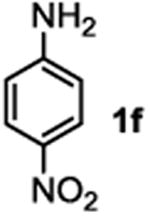

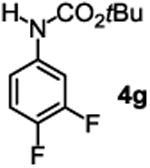

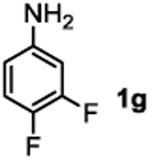

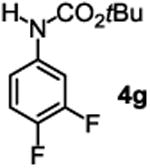

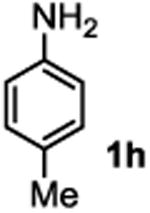

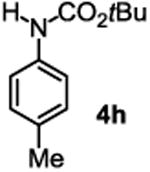

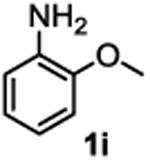

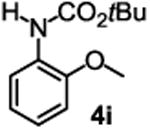

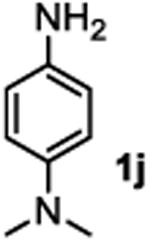

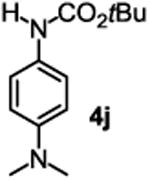

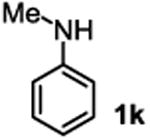

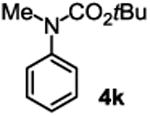

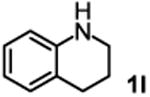

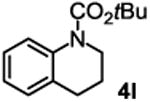

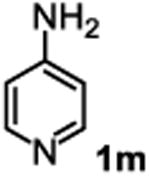

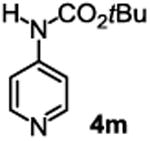

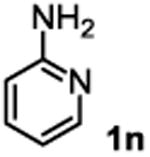

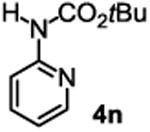

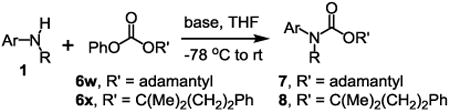

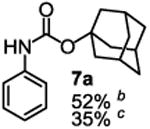

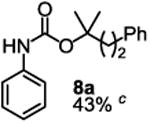

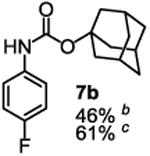

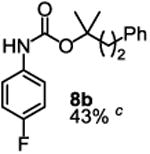

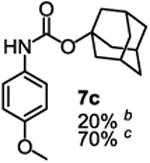

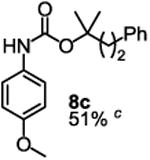

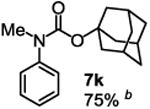

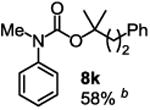

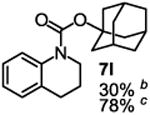

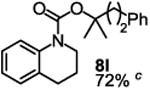

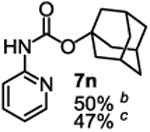

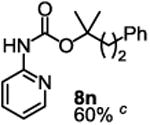

The substrate scope studies are summarized in Tables 2 and 3. With those in Table 2, we tested the reaction on arylamine substrates with different electronic properties using the carbonate carbamylation reagent 3x. In Table 3, the carbonates 6w and 6x, which contained the more complex adamantyl and 2-methyl-4-phenylbutan-2-yl groups, respectively, were tested for preparing the more challenging carbamates 7-8. As shown in Table 2, the electron deficient arylamines 1d, 1e, 1f and 1g all gave acceptable isolated yields comparable with the electron neutral aniline for the reaction (entries 1-4). For electron rich arylamines, we used 1h, 1i and 1j as substrates, similar yields were obtained in all the cases (entries 5-7). It is noted that the steric hindrance imposed by the ortho-methoxy group in arylamine 1i did not negatively affect the reaction (entry 6). We also tested the reaction on the secondary arylamines 1k and 1l. In these cases, only one equivalent base was used. Acceptable yields of 4k and 4l were obtained (entries 8-9). The reaction also worked well with aminopyridines despite that pyridine could potentially undergo nucleophilic addition reactions at their aromatic rings under strongly nucleophilic conditions. For 4-aminopyridine (1m), the product 4m was obtained in 67% yield (entry 10). For 2-aminopyridine (1n), the yield of 4n was more close to those of aniline derivatives (entry 11).

Table 2.

Substrate scope studies using different arylamines.a

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| entry | 1 | 4 | yield |

| 1 |

|

|

39%c |

| 2 |

|

|

38%b 40%c |

| 3 |

|

|

47%b 47%c |

| 4 |

|

|

41%c |

| 5 |

|

|

50%b 41%c |

| 6 |

|

|

27%b 39%c |

| 7 |

|

|

27%b 38%c |

| 8 |

|

|

60%b |

| 9 |

|

|

79%b 40%c |

| 10 |

|

|

39%b 67%c |

| 11 |

|

|

26%b 45%c |

Reaction conditions: 1 (1 equiv), 3x (1 equiv), base (2 equiv nBuLi bor tBuLi c except for entries 8-9, for which 1 equiv was used), THF (except for entry 7, for which PhMe was used), −78 °C to rt, 12 h. Isolated yields were reported in all cases.

Yields obtained using nBuLi as the base.

Yields obtained using tBuLi as the base.

Table 3.

Substrate scope studies using different tert-alkyl carbonates. a

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| entry | 1 | 7 (yield) | 8 (yield) |

| 1 | 1a |

|

|

| 2 | 1b |

|

|

| 3 | 1c |

|

|

| 4 | 1k |

|

|

| 5 | 1l |

|

|

| 6 | 1n |

|

|

Reaction conditions: 1 (1 equiv), 6w or 6x (1 equiv), base (2 equiv nBuLi b or tBuLi c except for entries 4-5, for which 1 equiv was used), THF, −78 °C to rt, 12 h. Isolated yields were reported in all cases.

Yields obtained using nBuLi as the base.

Yields obtained using tBuLi as the base.

To demonstrate the suitability of the new reaction to prepare N-arylcarbamates with an O-tert-alkyl group more complex than the tBu group, we selected the carbonates 6w and 6x as the carbamylation reagents. Preparation of these carbonates were simple and were conveniently achieved by reacting the commercially available phenyl chloroformate with the corresponding tertiary alcohols in dichloromethane using pyridine as the base at room temperature. The compounds were stable and were readily purified with flash column chromatography (see experimental section). Carbamylation of arylamines using these reagents were carried out on substrates with different electronic properties. As shown in Table 3, electron neutral (1a), poor (1b) and rich (1c) arylamines all gave positive results, and the products (7a-c and 8a-c) were obtained in acceptable to good isolated yields (entries 1-3). The reaction also worked well with the secondary arylamines 1k and 1l, in which cases one equivalent base was used, giving products 7k, 8k and 7l, 8l in good yields, respectively (entries 4-5). The more complex carbonates (6w and 6x) were also tested on aminopyridine 1n. Products 7n and 8n were obtained in 47% and 60% yields, respectively (entry 6).

All the carbamates in Table 3 would be difficult to synthesize using known methods. The method using dialkyl dicarbonates would be a good choice to prepare them but the reagents are inconvenient to synthesize and purify as discussed earlier. The method involving aryl isocyanate is also expected inconvenient because an additional step is needed for synthesizing the isocyanate, which may be unstable and difficult to purify in some cases, and the most commonly used method for preparing isocyanates uses the toxic phosgene or triphosgene20 although other methods are available.21 In addition, adding a tertiary alcohol to isocyanate can be difficult due to steric hindrance and usually a catalyst is needed. Nonetheless, among the compounds, 7a had been synthesized by transesterification of methyl carbamate with adamantyl alcohol. Potential drawbacks of the method include an additional step to prepare the methyl carbamate, the need of La(OiPr)3 catalyst, azeotropic reflux to remove methanol and long reaction time.11 Other similar hindered carbamates also appeared in the literature. Most of them were prepared by first converting an arylamine to an isocyanate and reacting the intermediate with a tertiary alcohol. For example, 3-methylpent-1-yn-3-yl phenylcarbamate was synthesized by adding 3-methylpent-1-yn-3-ol to phenyl isocyanate in the presence of BF3·Et2O.22 Many other examples used various catalysts including dibutyltin diacetate and lithium tert-butoxide to facilitate the addition of a tertiary alcohol to the isocyanate.23

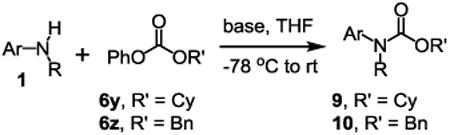

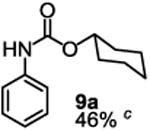

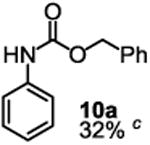

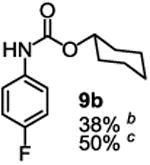

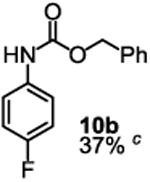

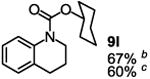

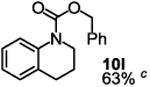

Besides its applications for the synthesis of the most difficult O-tert-alkyl N-arylcarbamates, some researchers might also prefer to use the method to prepare the less hindered O-secondary and O-primary alkyl N-arylcarbamates even though these compounds are much easier to access using other methods. Therefore, we briefly studied the scope of the reaction for preparing these compounds. As shown in Table 4, under the same conditions used for preparation of O-tert-alkyl N-arylcarbamates, both primary and secondary arylamines reacted readily with secondary (6y) and primary (6z) alkyl phenyl carbonates giving the corresponding arylcarbamates 9 and 10 in acceptable to good isolated yields.

Table 4.

Substrate scope studies using secondary and primary alkyl carbonates.a

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| entry | 1 | 9 (yield) | 10 (yield) |

| 1 | 1a |

|

|

| 2 | 1b |

|

|

| 3 | 1l |

|

|

Reaction conditions: 1 (1 equiv), 6y or 6z (1 equiv), base (2 equiv nBuLi b or tBuLi c except for entry 3, for which 1 equiv was used), THF, −78 °C to rt, 12 h. Isolated yields were reported in all cases.

Yields obtained using nBuLi as the base.

Yields obtained using tBuLi as the base.

Conclusions

In summary, we have developed a new method for the preparation of the hindered O-tert-alkyl N-arylcarbamates. The method converts arylamines directly to the desired carbamate in one step. No toxic phosgene or triphosgene, isocyanates, and dialkyl dicarbonates are needed. Instead, the stable and easily accessible alkyl phenyl carbonates are used. The reactions can be performed at low temperature, and there is no need of Lewis acid or other catalysts. Electron rich, electron poor and electron neutral arylamines, primary and secondary arylamines, and an aminopyridine have been demonstrated to be suitable substrates for the reaction. The method was also found suitable for the preparation of O-secondary and O-primary N-arylcarbamates. Acceptable to good isolated yields were obtained for the selected substrates. We expect the method to find wide usage for the preparation of carbamates in organic synthesis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial support from NIH (R15GM109288), NSF (CHE1111192), PHF Graduate Assistantship (S.S.) and MTU SURF (J.G. and T.W.); the assistance from D. W. Seppala (electronics), J. L. Lutz (NMR), L. R. Mazzoleni (MS), M. Khaksari (MS), and A. Galerneau (MS); and NSF equipment grants (CHE1048655, CHE9512455, MRI1531454); are gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Summary: Experimental details, compound characterization and images of 1H and 13C NMR spectra are presented in supporting information.

References

- 1.a) Dhouib IB, Annabi A, Jallouli M, Marzouki S, Gharbi N, Elfazaa S, Lasram MM. J Appl Biomed. 2016;14:85–90. [Google Scholar]; b) Ray S, Pathak SA, Chaturvedi D. Drug Future. 2005;30:161–180. [Google Scholar]; c) Forkert PG. Drug Metab Rev. 2010;42:551–589. doi: 10.3109/03602531003611915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Vacondio F, Silva C, Mor M, Testa B. Drug Metab Rev. 2010;42:551–589. doi: 10.3109/03602531003745960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Husar B, Liska R. Chem Soc Rev. 2012;41:2395–2405. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15232g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Dhouib I, Jallouli M, Annabi A, Marzouki S, Gharbi N, Elfazaa S, Lasram MM. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2016;23:9448–9458. doi: 10.1007/s11356-016-6418-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.a) Suarez-Castillo OR, Montiel-Ortega LA, Melendez-Rodriguez M, Sanchez-Zavala M. Tetrahedron Lett. 2007;48:17–20. [Google Scholar]; b) Sun S, Tirotta I, Zia N, Hutton CA. Aust J Chem. 2014;67:411–415. [Google Scholar]; c) Roychoudhury R, Pohl NLB. Org Lett. 2014;16:1156–1159. doi: 10.1021/ol500023y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Snider EJ, Wright SW. Tetrahedron Lett. 2011;52:3171–3174. [Google Scholar]; e) Annese C, D'Accolti L, De Zotti M, Fusco C, Toniolo C, Williard PG, Curci R. J Org Chem. 2010;75:4812–4816. doi: 10.1021/jo100855h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Shchegravina ES, Knyazev DI, Beletskaya IP, Svirshchevskaya EV, Schmalz HG, Fedorov AY. Eur J Org Chem. 2016:5620–5623. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hernandez AS, Hodges JC. J Org Chem. 1997;62:3153–3157. doi: 10.1021/jo9700890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Poole LB, Klomsiri C, Knaggs SA, Furdui CM, Nelson KJ, Thomas MJ, Fetrow JS, Daniel LW, King SB. Bioconjugate Chem. 2007;18:2004–2017. doi: 10.1021/bc700257a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.a) Carafa M, Quaranta E. Mini Rev Org Chem. 2009;6:168–183. [Google Scholar]; b) Chaturvedi D, Mishra N, Mishra V. Curr Org Synth. 2007;4:308–320. [Google Scholar]

- 6.a) Pothukanuri S, Pianowski Z, Winssinger N. Eur J Org Chem. 2008:3141–3148. [Google Scholar]; b) Grzyb JA, Shen M, Yoshina-Ishii C, Chi W, Brown RS, Batey RA. Tetrahedron. 2005;61:7153–7175. [Google Scholar]; c) Vaillard VA, Gonzalez M, Perotti JP, Grau RJA, Vaillard SE. RSC Adv. 2014;4:13012–13017. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Usman M, Ren ZH, Wang YY, Guan ZH. RSC Adv. 2016;6:107542–107546. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yamada H, Wada Y, Tanimoto S, Okano M. Bull Chem Soc Jpn. 1982;55:2480–2483. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Richter LS, Andersen S. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998;39:8747–8750. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang XC, Keillor JW. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997;38:313–316. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hatano M, Kamiya S, Moriyama K, Ishihara K. Org Lett. 2011;13:430–433. doi: 10.1021/ol102754y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.a) Aresta M, Quaranta E. Tetrahedron. 1992;48:1515–1530. [Google Scholar]; b) Feroci M, Casadei MA, Orsini M, Palombi L, Inesi A. J Org Chem. 2003;68:1548–1551. doi: 10.1021/jo0266036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Chaturvedi D, Kumar A, Ray S. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003;44:7637–7639. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inesi A, Mucciante V, Rossi L. J Org Chem. 1998;63:1337–1338. [Google Scholar]

- 14.a) Langanke J, Arfsten N, Buskens P, Habets R, Klankermayer J, Leitner W. J Sol-Gel Sci Techn. 2013;67:282–287. [Google Scholar]; b) Lopez-Lezama JC, Cabeza M, Mayorga I, Soriano J, Sainz T, Bratoeff E. Arch Pharm. 2014;347:320–326. doi: 10.1002/ardp.201300067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Chavez-Riveros A, Garrido M, Apan MTR, Zambrano A, Diaz M, Bratoeff E. Eur J Med Chem. 2014;82:498–505. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2014.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stock C, Bruckner R. Adv Synth Catal. 2012;354:2309–2330. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Urbanaite A, Jonusis M, Buksnaitiene R, Balkaitis S, Cikotiene I. Eur J Org Chem. 2015:7091–7113. [Google Scholar]

- 17.a) Dighe SN, Jadhav HR. Tetrahedron Lett. 2012;53:5803–5806. [Google Scholar]; b) Kessler A, Coleman CM, Charoenying P, O'Shea DF. J Org Chem. 2004;69:7836–7846. doi: 10.1021/jo048723e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Youn SW, Kim YH. Org Lett. 2016;18:6140–6143. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.6b03151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.a) Pope BM, Yamamoto Y, Tarbell DS. Org Synth. 1977;57:45. [Google Scholar]; b) Hillebrandt S, Adermann T, Alt M, Schinke J, Glaser T, Mankel E, Hernandez-Sosa G, Jaegermann W, Lemmer U, Pucci A, Kowalsky W, Mullem K, Lovrincic R, Hamburger M. ACS Appl Mater Inter. 2016;8:4940–4945. doi: 10.1021/acsami.5b10901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Naddo T, Che YK, Zhang W, Balakrishnan K, Yang XM, Yen M, Zhao JC, Moore JS, Zang L. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:6978–6979. doi: 10.1021/ja070747q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Results to be published.

- 20.a) Lei F, Sun CY, S Xu, Wang QQ, OuYang YQ, Chen C, Xia H, Wang LX, Zheng PW, Zhu WF. Eur J Med Chem. 2016;116:27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2016.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Chen Y, Su L, Yang XY, Pan WY, Fang H. Tetrahedron. 2015;71:9234–9239. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bast K, Behrens M, Durst T, Grashey R, Huisgen R, Schiffer R, Temme R. Eur J Org Chem. 1998:379–385. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haak E. Eur J Org Chem. 2008:788–792. [Google Scholar]

- 23.a) Villhauer EB, Brinkman JA, Naderi GB, Burkey BF, Dunning BE, Prasad K, Mangold BL, Russell ME, Hughes TE. J Med Chem. 2003;46:2774–2789. doi: 10.1021/jm030091l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Stevens AC, Pagenkopf BL. Org Lett. 2010;12:3658–3661. doi: 10.1021/ol101453e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Gwon D, Hwang H, Kim HK, Marder SR, Chang S. Chem Eur J. 2015;21:17200–17204. doi: 10.1002/chem.201503511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.