Abstract

Purpose of Review

The liver is the largest internal organ and performs both exocrine and endocrine function that is necessary for survival. Liver failure is among the leading causes of death and represents a major global health burden. Liver transplantation is the only effective treatment for end-stage liver diseases. Animal models advance our understanding of liver disease etiology and hold promise for the development of alternative therapies. Zebrafish has become an increasingly popular system for modeling liver diseases and complements the rodent models.

Recent Findings

The zebrafish liver contains main cell types that are found in mammalian liver and exhibits similar pathogenic responses to environmental insults and genetic mutations. Zebrafish have been used to model neonatal cholestasis, cholangiopathies, such as polycystic liver disease, alcoholic liver disease, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. It also provides a unique opportunity to study the plasticity of liver parenchymal cells during regeneration.

Summary

In this review, we summarize the recent work of building zebrafish models of liver diseases. We highlight how these studies have brought new knowledge of disease mechanisms. We also discuss the advantages and challenges of using zebrafish to model liver diseases.

Keywords: Cholestasis, Steatosis, Alcoholic liver disease, Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, Fibrosis, Liver regeneration

Introduction

The liver is the largest gland in the body and plays vital roles in maintaining normal homeostasis. Metabolically, the liver is the prime site for detoxification, glycogen storage, and production of serum proteins, lipids, and hormone. It also generates bile that is critical for digestion and absorption of fat and vitamins in the small intestine. Whereas toxin exposure, viral infection, autoimmune responses, and genetic mutations can all serve as triggers, the resulting liver diseases often progress in a similar fashion [1]. Inflammation is observed first, followed by fibrosis as the liver forms scar tissue. Extensive scarring, distortion of the liver architecture, and loss of liver function are the characteristics of cirrhosis, which is the end stage of chronic liver diseases. Being constantly exposed to toxins, the liver has superior ability to repair itself. However, in cirrhosis, the extent of damage exceeds the self-regenerative capacity of the liver and liver failure occurs. Cirrhosis is among the leading causes of death worldwide [2], and the only available effective treatment is liver transplantation.

A better understanding of the mechanisms causing chronic liver diseases is key to improve diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. Although rodent models have been used extensively in liver research, it has become evident that no single animal model is capable of recapitulating every aspect of human liver diseases. Incorporating multiple animal models is more likely to yield complementary insights. The teleost zebrafish (Danio rerio) is a favorite vertebrate model organism in developmental biology. As the development and function of zebrafish organs are strikingly similar to those of humans, they have been successfully used to model hematopoietic disorders, cancer, cardiovascular diseases, muscle diseases, neurological disorders, kidney diseases, etc. [reviewed in 3]. In this review, we highlight the recent advances in establishing zebrafish models of liver diseases. We focus on cholestasis, alcoholic liver disease, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, and liver regeneration. Zebrafish models of liver cancer have been recently reviewed elsewhere [4]. We demonstrate the technical advantages of using zebrafish to study liver biology. We also discuss the necessity to gain deeper knowledge of zebrafish liver homeostasis and physiology in order to define which aspects of different liver diseases can be modeled in fish.

Comparison of liver anatomy between zebrafish and mammals

The basic functional unit of mammalian liver is the liver lobule [5]. Each lobule has a hexagonal shape, composed of cords of hepatocytes that radiate from the central vein in the center of the lobule to the portal vein in the vertex. Hepatocytes can be divided into three different groups along the portocentral axis by their metabolic activities [6]. This so-called liver zonation is crucial for organ function. Hepatocytes secrete bile on the apical side through small channels known as bile canaliculi [5]. Bile fluid is then drained to the intrahepatic bile duct that is located within the portal triad along with portal vein and hepatic artery. On the basal side of hepatocytes are sinusoidal capillaries. Kupffer cells, the resident macrophages in the liver, also reside in these sinusoids. Vitamin A-storing hepatic stellate cells are located in the space of Disse that is between sinusoids and hepatocytes.

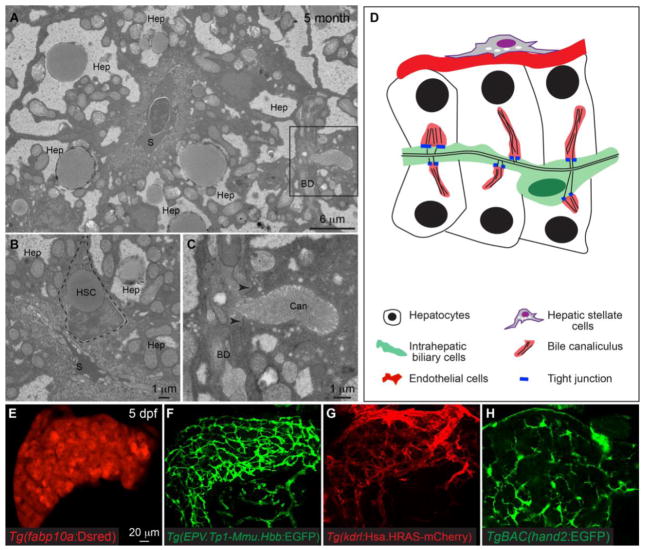

With the exception of Kupffer cells, all counterparts of major mammalian liver cell types have been reported in zebrafish (Table 1). At first glance, zebrafish liver anatomy seems very different from the mammals as the blood vessels are randomly distributed throughout the organ and there are no morphologically distinguishable central veins or portal veins [7]. Hepatocytes are arranged in tubules and the bile duct is located in the center. Metabolic zonation has not been described in the zebrafish liver. There are no portal triads. Instead, intrahepatic bile ducts and blood vessels are separated by hepatocytes (Fig. 1A,D). Histological analyses and transmission electron microscopy reveal the conservation and distinction of zebafish and mammalian liver anatomy. Similar to mammals, zebrafish hepatocytes secrete bile through bile canaliculi on the apical side. In mammals, bile canaliculi are located in between hepatocytes and are sealed by tight junctions to prevent leakage of bile [8]. In zebrafish, bile canaliculi are invaginations of the apical hepatocyte membrane that connect to biliary ductules (Fig. 1C,D). Bile canaliculi are also sealed by tight junctions, except that in zebrafish, tight junctions form between hepatocytes and biliary ductules. The blood vessels on the basal side of hepatocytes resemble the sinusoid capillaries in mammalian liver. Hepatic stellate cells also reside in between hepatocytes and endothelial cells and store lipid droplets (Fig. 1B). Lastly, whereas intrahepatic bile ducts in mammalian liver are often composed of multiple cholangiocytes with apparent epithelial morphology, most of the intrahepatic bile ducts in zebrafish liver are made up of one or two cholangiocytes (Fig. 1A,C). Only the cholangiocytes in the few large bile ducts that connect to the extrahepatic bile duct exhibit the typical columnar epithelial morphology [7, 9].

Table 1.

Tools to study zebrafish liver biology

| A. Transgenic lines that label different liver cell types. | ||

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Transgenic line | Cell type labeled | Reference |

| Tg(fabp10a:dsred) | Hepatocytes | [1] |

| Tg(EPV.TP1-Mmu.Hbb:EGFP) | Intrahepatic biliary cells | [2, 3] |

| Tg(krt18:EGFP) | Intrahepatic biliary cells, extrahepatic biliary cells, gallbladder | [4] |

| Tg(kdrl:Hsa.HRAS-mCherry) | Endothelial cells | [5] |

| TgBAC(hand2:EGFP) | Hepatic stellate cells | [6] |

| Tg(wt1b:EGFP) | Hepatic stellate cells | [7, 6] |

|

| ||

| B. Antibodies that label different liver cell types or subcellular structures. | ||

|

| ||

| Antibody | Cell type/structure labeled | Reference |

|

| ||

| Prox1 | Hepatoblasts, hepatocytes, intrahepatic biliary cells | [8] |

| Hnf4a | Hepatocytes | [8] |

| Alcam/Activated leukocyte cell adhesion molecule | Intrahepatic biliary network | [9] |

| 2F11/Annexin A4 | Intrahepatic biliary network | [10, 8] |

| Cytokeratin18 | Intrahepatic biliary cells including the terminal ductules | [11] |

| Abcb11/BSEP | Bile canaliculus | [12, 9] |

| Mdr1 | Bile canaliculus | [2, 13] |

| Desmin | Hepatic stellate cells | [6, 14] |

| GFAP/Glial fibrillary acidic protein | Hepatic stellate cells | [15, 6] |

|

| ||

| C. Histological stains. | ||

|

| ||

| Histology | Purpose | Reference |

|

| ||

| Hematoxylin and eosin | Overview of liver histology | [16] |

| Mason’s Trichrome | Type 1 collagen/Fibrosis | [17] |

| Oil red o | Neutral triglycerides and lipids/Steatosis | [18] |

| Nile red | Neutral lipid droplets/Steatosis | [19] |

| Periodic Acid-Schiff stain | Glycogen deposition | [20] |

|

| ||

| D. Assays to examine liver function. | ||

|

| ||

| Assay | Purpose | Reference |

|

| ||

| PED6 | Lipid uptake and transport | [21, 22] |

| BODIPY-conjugated fatty acids | Lipid metabolism and transport | [23] |

Reference:

Her GM, Chiang CC, Chen WY, Wu JL. In vivo studies of liver-type fatty acid binding protein (L-FABP) gene expression in liver of transgenic zebrafish (Danio rerio). FEBS Lett. 2003;538(1–3):125–33.

Lorent K, Moore JC, Siekmann AF, Lawson N, Pack M. Reiterative use of the notch signal during zebrafish intrahepatic biliary development. Dev Dyn. 2010;239(3):855–64. doi:10.1002/dvdy.22220.

Parsons MJ, Pisharath H, Yusuff S, Moore JC, Siekmann AF, Lawson N et al. Notch-responsive cells initiate the secondary transition in larval zebrafish pancreas. Mech Dev. 2009;126(10):898–912. doi:10.1016/j.mod.2009.07.002.

Wilkins BJ, Gong W, Pack M. A novel keratin18 promoter that drives reporter gene expression in the intrahepatic and extrahepatic biliary system allows isolation of cell-type specific transcripts from zebrafish liver. Gene Expr Patterns. 2014;14(2):62–8. doi:10.1016/j.gep.2013.12.002.

Chi NC, Shaw RM, De Val S, Kang G, Jan LY, Black BL et al. Foxn4 directly regulates tbx2b expression and atrioventricular canal formation. Genes Dev. 2008;22(6):734–9. doi:10.1101/gad.1629408.

Yin C, Evason KJ, Maher JJ, Stainier DY. The basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor, heart and neural crest derivatives expressed transcript 2, marks hepatic stellate cells in zebrafish: analysis of stellate cell entry into the developing liver. Hepatology. 2012;56(5):1958–70. doi:10.1002/hep.25757.

Bollig F, Perner B, Besenbeck B, Kothe S, Ebert C, Taudien S et al. A highly conserved retinoic acid responsive element controls wt1a expression in the zebrafish pronephros. Development. 2009;136(17):2883–92. doi:10.1242/dev.031773.

Dong PD, Munson CA, Norton W, Crosnier C, Pan X, Gong Z et al. Fgf10 regulates hepatopancreatic ductal system patterning and differentiation. Nat Genet. 2007;39(3):397–402. doi:10.1038/ng1961.

Sakaguchi TF, Sadler KC, Crosnier C, Stainier DY. Endothelial signals modulate hepatocyte apicobasal polarization in zebrafish. Curr Biol. 2008;18(20):1565–71. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2008.08.065.

Crosnier C, Vargesson N, Gschmeissner S, Ariza-McNaughton L, Morrison A, Lewis J. Delta-Notch signalling controls commitment to a secretory fate in the zebrafish intestine. Development. 2005;132(5):1093–104. doi:10.1242/dev.01644.

Matthews RP, Lorent K, Russo P, Pack M. The zebrafish onecut gene hnf-6 functions in an evolutionarily conserved genetic pathway that regulates vertebrate biliary development. Dev Biol. 2004;274(2):245–59. doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.06.016.

Gerloff T, Stieger B, Hagenbuch B, Madon J, Landmann L, Roth J et al. The sister of P-glycoprotein represents the canalicular bile salt export pump of mammalian liver. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(16):10046–50.

Sadler KC, Amsterdam A, Soroka C, Boyer J, Hopkins N. A genetic screen in zebrafish identifies the mutants vps18, nf2 and foie gras as models of liver disease. Development. 2005;132(15):3561–72. doi:10.1242/dev.01918.

Yokoi Y, Namihisa T, Kuroda H, Komatsu I, Miyazaki A, Watanabe S et al. Immunocytochemical detection of desmin in fat-storing cells (Ito cells). Hepatology. 1984;4(4):709–14.

Gard AL, White FP, Dutton GR. Extra-neural glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) immunoreactivity in perisinusoidal stellate cells of rat liver. J Neuroimmunol. 1985;8(4–6):359–75.

Pack M, Solnica-Krezel L, Malicki J, Neuhauss SC, Schier AF, Stemple DL et al. Mutations affecting development of zebrafish digestive organs. Development. 1996;123:321–8.

Liu W, Chen JR, Hsu CH, Li YH, Chen YM, Lin CY et al. A zebrafish model of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma by dual expression of hepatitis B virus X and hepatitis C virus core protein in liver. Hepatology. 2012;56(6):2268–76. doi:10.1002/hep.25914.

Passeri MJ, Cinaroglu A, Gao C, Sadler KC. Hepatic steatosis in response to acute alcohol exposure in zebrafish requires sterol regulatory element binding protein activation. Hepatology. 2009;49(2):443–52. doi:10.1002/hep.22667.

Nussbaum JM, Liu LJ, Hasan SA, Schaub M, McClendon A, Stainier DY et al. Homeostatic generation of reactive oxygen species protects the zebrafish liver from steatosis. Hepatology. 2013;58(4):1326–38. doi:10.1002/hep.26551.

Howarth DL, Yin C, Yeh K, Sadler KC. Defining hepatic dysfunction parameters in two models of fatty liver disease in zebrafish larvae. Zebrafish. 2013;10(2):199–210. doi:10.1089/zeb.2012.0821.

Farber SA, Olson ES, Clark JD, Halpern ME. Characterization of Ca2+-dependent phospholipase A2 activity during zebrafish embryogenesis. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(27):19338–46.

Farber SA, Pack M, Ho SY, Johnson ID, Wagner DS, Dosch R et al. Genetic analysis of digestive physiology using fluorescent phospholipid reporters. Science. 2001;292(5520):1385–8. doi:10.1126/science.1060418.

Carten JD, Bradford MK, Farber SA. Visualizing digestive organ morphology and function using differential fatty acid metabolism in live zebrafish. Dev Biol. 2011;360(2):276–85. doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.09.010.

Fig. 1.

Anatomy of zebrafish liver. (A–C) Transmission electron microscopy images of the liver from a 5-month old wildtype adult zebrafish. (A) Low magnification image showing a sinusoidal capillary (S) that is located in the center of the image, and on the basal side of the hepatocytes (Hep). The black square marks an intrahepatic biliary ductule (BD) on the apical side of a hepatocyte. (B) showing a lipid-storing hepatic stellate cell (HSC) that is located in between the hepatocyte (Hep) and sinusoidals (S). (C) is a high magnification view of the black square in (A). The bile canaliculus (Can) is invagination of the hepatocyte apical membrane and contains tightly packed actin-rich microvilli. The bile canaliculus directly associates with the biliary ductule (BD). Tight junctions (arrowheads) form between the hepatocyte and biliary ductule to seal the bile canaliculus. (D) Diagram showing the basic architecture of zebrafish liver. (E–H) Confocal images of the liver in the hepatocyte reporter line Tg(fabp10a:dsRed) (E), the intrahepatic biliary cell reporter line Tg(EPV.Tp1-Mmu.Hbb:EGFP) (F), the endothelial cell reporter line Tg(kdrl:Hsa.HRAS-mCherry) (G), and the hepatic stellate cell reporter line TgBAC(hand2:EGFP) (H) at 5 days post fertilization (dpf). (E–H) Ventral views, anterior is to the top.

Liver development in zebrafish

The zebrafish liver arises from the foregut endoderm, similar to mammals. The first sign of hepatic specification is seen at around 22 hours post fertilization (hpf) when a group of anterior endodermal cells start to express hepatic transcription factors hhex and prox1 [10]. Between 24 and 30 hpf, the gut undergoes left-ward bending, followed by budding of the liver primordium to the left side of the embryo [11]. The liver bud is very prominent at 48 hpf. Soon after, hepatoblasts differentiate into hepatocytes and intrahepatic biliary cells. Development of intrahepatic bile duct in mammals is through ductal plate [12]. At embryonic day 15.5 in mouse embryo, the hepatoblasts surrounding the branches of portal vein form ductal plate. Primary ductal plate structures exhibit an asymmetric composition with cells expressing cholangiocyte markers detected on the portal side and undifferentiated hepatoblasts located on the parenchymal side. Such asymmetry resolves as some of the hepatoblasts on the parenchymal side differentiate into cholangiocytes and join the periportal cholangiocytes to form a mature duct. In zebrafish, there is no evidence of ductal plate structures in the developing liver. Biliary cells first appear in vicinity of extrahepatic bile duct then expand to the rest of the liver [13]. Except for the large bile ducts that are associated with the extrahepatic bile duct, most intrahepatic bile ducts are formed when cellular processes derived from different biliary cells become interconnected. Concomitant with hepatic differentiation, endothelial cells and progenitors of hepatic stellate cells enter the liver [14, 15]. By 72 hpf, zebrafish liver contains a biliary ductal network and a vascular network with hepatocytes localized in between.

Tools to study liver pathophysiology in zebrafish

Zebrafish has emerged as an important model to study liver development and diseases in the past two decade. Its general, strengths include rapid external development, optical translucence, accessibility to genetic and chemical manipulation, ease of collecting hundreds of embryos on a weekly base, and relatively low-cost maintenance. Unlike the laboratory rodent strains, most zebrafish strains are not inbred and genetic background does not impose a significant impact on the phenotype. The zebrafish also offers features that are particularly useful for liver research: the molecular regulation of liver development is largely conserved between zebrafish and mammals. The zebrafish liver becomes functional and develops all main cell types by 4 days post fertilization. Because zebrafish liver cells perform similar function as their mammalian counterparts, histological stains that are routine in mammalian liver research can be easily applied to zebrafish to examine liver pathophysiology (Table 1). Transgenic lines that express fluorescent proteins in hepatocytes, intrahepatic biliary cells, endothelial cells, and hepatic stellate cells are available, facilitating the observation of these cells both in live fish and in fixed livers (Table 1). These transgenic zebrafish also allow isolation of different liver cell types through fluorescence activated cell sorting for downstream transcriptome analyses [16]. Commercially available fluorescent lipid analogs, which are designed for visualizing lipid uptake and processing in live fish, have proven to be extremely sensitive in detecting hepatobiliary injuries (Table 1). For instance, the phosphoethanolamine analog PED6, when added to the water, is absorbed by the intestine and turns on fluorescence when cleaved by intestinal lipases [17]. When the function of the hepatobiliary system is intact, PED6 is processed through the liver and excreted into bile. It is transported through intrahepatic biliary network before becoming concentrated in the gallbladder. The fluorescent gallbladder signal can be easily detected using a low-power epifluoresent microscope. A reduction in PED6 uptake in the gallbladder is a strong indication of impaired hepatobiliary function. More recently, BODIPY-conjugated fatty acids with varying lengths of acyl chain have been used in conjunction with confocal microscopy to visualize the biliary network and the subcellular structures of the hepatocytes in live larvae [18]. BODIPY analogs have proven to be very effective in recognizing fat accumulation in steatosis and obstructions in the biliary tree [19, 20]. In this review, we provide a few examples of how the various tools described above can be applied in gain- and loss-of-function studies to test gene function in liver disease pathogenesis, and how they serve as straightforward readouts in forward genetic screens and chemical screens to identify novel regulators of liver development and diseases.

Zebrafish models of liver diseases

Neonatal cholestasis

Cholestatic jaundice affects 1 in every 2500 infants [21] and often indicates serious hepatobiliary and metabolic dysfunction. Cholestasis may result in significant morbidity and mortality due to pruritus, malnutrition, and complications arising from portal hypertension secondary to biliary fibrosis. Of the many conditions that cause neonatal cholestasis, the most common are biliary atresia (BA) (25–35%), genetic disorders (25%), metabolic diseases, and α1-antitrypsin (A1AT) deficiency (10%) [22, 21]. We discuss the recent progress in using zebrafish to model neonatal cholestasis, with an emphasis on BA.

BA is a leading cause of neonatal cholestasis, and has an incidence of 1 in 10–19,000 in Europe and North America [23]. It is a multifaceted cholangiopathy that mainly destroys the extrahepatic bile duct and blocks bile flow. Even with Kasai portoenterostomy as a surgical intervention to improve biliary drainage, the liver disease progresses to end-stage cirrhosis in most children. BA accounts for nearly 40–50% of children who undergo liver transplantation. The etiology of BA is still unclear, but is likely caused by a combination of morphogenetic abnormalities, environmental factors, and inflammatory dysregulation [24]. The most well established animal model of BA is newborn Balb/C mouse infected with Rhesus rotavirus (RRV) [25–27]. Within a week of infection, these mice exhibit obstruction of the biliary tree and cholestasis that resemble many features of human BA. Whereas the RRV model has demonstrated the contribution of immune cells and inflammation to BA pathogenesis, recent studies using zebrafish have illustrated the involvement of genetic and epigenetic factors as well as environmental toxins in BA. Three groups independently performed genome-wide association studies (GWAS) and found single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNPs) or copy number variants (CNVs) that show strong association with BA susceptibility. They turned to the zebrafish model to validate the biological function of the candidate genes by using the morpholino oligonucleotide knockdown technique. Matthews’ group revealed that knocking down glypican 1 (gpc1), which encodes a cell-surface heparan sulfate proteoglycan, and adducin 3 (add3), which encodes a membrane skeletal protein, both resulted in decreased PED6 uptake in the gallbladder and a less complex intrahepatic biliary network [28, 29]. gpc1 knockdown also led to a smaller gallbladder [28]. In addition, Hedgehog signaling activity was increased in both gpc1 and add3 knockdown larvae. Injection of Sonic Hedgehog protein into the wild-type fish caused biliary abnormalities, whereas treatment with an Hedgehog inhibitor partially rescued the biliary phenotypes in gpc1 and add3 knockdown larvae. Excessive Hedgehog activation has also been observed in children with BA [30], suggesting that Hedgehog signaling has evolutionarily conserved roles in cholangiocyte development. The Sindhi group knocked down a different candidate gene, ADP-ribosylation factor 6 (arf6), which encodes a GTP-binding protein [31]. They observed similar intrahepatic biliary defects to those seen in gpc1 and add3 knockdown larvae. They further linked the ARF6 and EGFR pathways in regulating intrahepatic biliary system development. These findings demonstrate that zebrafish can be used not only to validate GWAS discoveries, but also to identify molecular pathways that are altered by variants.

A recent study using zebrafish has provided strong evidence to support the toxin theory for BA pathogenesis. By conducting the fluorescent lipid analog assay in zebrafish, Lorent et al. screened for compounds in the extracts of Dysphania species that cause BA-like symptoms in herds of sheep and cows in New South Wales, Australia [32]. This approach led to the discovery of a novel isoflavonoid, biliatresone, which specifically obstructs the extrahepatic bile duct in zebrafish larvae. In a subsequent study, the authors showed that genes involved in glutathione (GSH) metabolism were upregulated in biliatresone-treated larval livers, and hepatic GSH was depleted upon biliatresone treatment [33]. Taking advantage of the power of in vivo imaging in zebrafish, the endogenous GSH redox state was assessed by a redox-sensitive fluorescent biosensor, revealing that the extrahepatic biliary cells had a more oxidized GSH pool than the hepatocytes and intrahepatic biliary cells both with and without biliatresone treatment, which may explain why the extrahepatic biliary cells are specifically targeted by the toxin. In support of the contribution of GSH to BA, inhibition of GSH synthesis sensitized both the extrahepatic and intrahepatic biliary cells to the toxin and increasing GSH levels by pharmacological approaches suppressed biliatresone-induced injury. Importantly, the specific damage of biliary cells caused by biliatresone treatment, as well as the link between GSH and biliatresone also holds true in mouse [34, 32]. This study provides an excellent example of using chemical screening approaches in zebrafish to identify novel disease mechanisms.

Studies of mutant zebrafish have indicated that DNA hypomethylation is a potential mechanism to initiate molecular cascades leading to BA. In the ducttrip mutant, a mutation in the gene for S-adenosyl homocysteine hydrolase,ahcy, results in global inhibition of DNA methylation [35]. In both ducttrip mutants and fish treated with an inhibitor of DNA methylation, the intrahepatic bile ducts are disorganized and sparse. Activation of the interferon-γ pathway has been observed in human BA and the mouse RRV model [36, 37]. In zebrafish, inhibition of DNA methylation increased the expression of interferon-γ pathway genes, and injection of interferon-γ into the zebrafish recapitulated the biliary phenotypes. Further demonstrating the relevance of the zebrafish findings to human BA, the authors showed that DNA methylation was greatly reduced in the cholangiocytes in BA patients compared to those in patients with other types of neonatal cholestasis. Cofer et al. conducted methylation microarray analysis in livers of BA patients and showed that Hedgehog pathway genes SHH and GLI2, as well as PDGF pathway gene PDGFA were hypomethylated in BA [38]. Interestingly, injection of PDGF-AA protein dimer induced biliary phenotype in zebrafish larvae and activation of Hedgehog pathway increased PDGFA expression, suggesting a potential link between Hedgehog pathway and PDGFA in BA.

Zebrafish have also been used to model inherited cholestatic diseases in children. In Alagille syndrome, mutations in the Notch ligand gene JAGGED1 and receptor gene NOTCH2 cause bile duct paucity [39]. Inhibition of Notch signaling activity in zebrafish also suppresses biliary differentiation and morphogenesis [7]. Knockdown of genes involved in arthrogryposis-renal dysfunction-cholestasis syndrome [40–42] and North American Indian Childhood Cirrhosis [43] leads to intrahepatic biliary defects in zebrafish. Progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis (PFIC) is a group of inherited neonatal cholestatic disorders that primarily injure the hepatocytes [44]. PFIC is characterized by impaired bile secretion due to mutations in the genes encoding the canalicular transporters ATP8B1, ABCB11, and ABCB4, and tight junction protein TJP2. Zebrafish form canaliculi on the apical side of hepatocytes, and the ultrastructure of zebrafish canaliculi is very similar to the mammalian counterparts (Fig. 1). The zebrafish canalicular transporter proteins have high (>60%) homology with the human proteins [45]. The Abcb11 protein is detected in the canaliculus in zebrafish, similar to its localization in the mammalian liver [14]. It will be interesting to generate the canalicular transporter mutants and explore the feasibility of modeling PFIC in zebrafish.

Polycystic liver disease

Polycystic liver diseases (PCLD) are genetic disorders of the biliary epithelium, characterized by progressive formation of fluid-filled cysts throughout the liver parenchyma [46]. They result in massive enlargement of the liver, which compresses the neighboring organs and impair their function. The patients are also at high risk of developing cholangitis, fibrosis, cirrhosis, and even cancer. Mutations in the genes encoding cilia-associated proteins Polycystin1/PKD1, Polycystin2/PKD2, and PKHD1 are found in PCLD patients who also have polycystic kidney [47]. Mutations in SEC63 and PRKCSH are responsible for isolated PCLDs. Both genes encode proteins that are located in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and function in translocation of glycoproteins into the ER. The zZebrafish genome contains orthologs of the genes mutated in PCLD. The LaRusso group showed that knockdown of sec63, prkcsh, and pkd1a in zebrafish by antisense morpholino oligonucleotides caused the formation of hepatic cysts [48]. Similarly, both prkcsh knockdown and overexpression led to pronephric cysts, abnormal body curvature, and situs inversus, but not hepatic cysts [49]. Monk et al. identified a sec63 zebrafish mutant carrying a missense mutation predicted to change a highly conserved amino acid. Interestingly, aside from ER stress and steatosis, the mutant liver does not develop hepatic cysts [50]. Several mechanisms have been shown to cause hepatic cysts in mammals, including ductal plate malformation, disrupted cholangiocyte polarity, increased fluid secretion from the cholangiocytes, as well as defects in primary cilia [51]. Intrahepatic bile duct development in zebrafish does not involve the formation of ductal plate. The intrahepatic biliary cells do not have a typical epithelial appearance with the exception of those composing the large bile ducts. Primary cilia and fluid secretion have not been well characterized in zebrafish biliary cells. The differences in bile duct development and cholangiocyte physiology may explain why perturbing PCLD-related gene function in zebrafish does not fully recapitulate the cystic phenotypes seen in human.

Alcoholic liver disease

Alcoholic liver disease (ALD) results from excessive alcohol intake and is one of the most common causes of liver-related morbidity and mortality [52]. ALD progresses from hepatic steatosis, steatohepatitis, fibrosis, cirrhosis, and eventually hepatocellular carcinoma [53]. Chronic ALD is an adult disease and takes years of alcohol abuse. Whether zebrafish can also be used to model chronic ALD has not been convincingly demonstrated. It has been shown that adult zebrafish develop steatosis, steatohepatitis and fibrosis when being continuously housed in 1% ethanol for a long period of time [54]. However, such treatment may prevent the animal from feeding properly, making it difficult to determine to what extent the liver injuries are induced directly by alcohol.

In recent years, binge drinking is becoming an alarming global health problem [55]. Binge alcohol exposure causes liver inflammation, steatosis, hepatocyte death, and promotes activation of hepatic stellate cells and fibrogenesis [56]. Thus it is crucial to identify therapeutic agents that target multiple aspects of the disease. Oral feeding of alcohol only induces hepatic steatosis in rodent models [57, 58], and development of inflammation and fibrosis requires a second insult [59, 60]. Zebrafish larvae are well suited to study the effects of acute alcohol exposure as alcohol can be added to the water and does not cause lethality [61]. Genes and pathways necessary for alcohol metabolism are highly conserved in zebrafish and they readily take up and metabolize alcohol at as early as 4 days post fertilization [62, 61, 63, 64]. Intriguingly, exposing 4-day-old larvae to 2% ethanol for just 24 hours is sufficient to induce steatosis, angiogenesis, recruitment of macrophages, and activation of hepatic stellate cells [61, 15, 16]. Using this model, the Sadler group showed that the sterol response element binding protein (Srebp) pathway [61] and activation of unfolded protein response (UPR) were required to induce hepatic steatosis in acute ALD liver injury [65, 66]. Blocking ethanol metabolizing enzymes and oxidative stress alleviated UPR activation and reduced ethanol-induced steatosis in the zebrafish larvae [67]. Activating transcription factor 6 (Atf6) [65], one of the three UPR sensors, was both necessary and sufficient to cause hepatic steatosis independent of Srebp activity. Our group, on the other hand, investigated the roles of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) signaling in acute alcoholic liver injury [16]. We showed that blocking VEGF receptor Kdrl activity by either a pharmacological inhibitor or genetic mutation suppressed hepatic steatosis, angiogenesis and fibrogenesis induced by acute ethanol treatment. To understand how these three aspects of ethanol-induced acute live injury were linked to each other and the mechanism of action of VEGF signaling, we performed quantitative PCR on the FACS-sorted liver cells. We found that both hepatic stellate cells and endothelial cells, but not hepatic parenchymal cells, exhibited robust kdrl expression upon ethanol treatment, suggesting that angiogenesis and fibrogenesis are directly targeted by Kdrl inhibition. In cloche mutants that do not form hepatic endothelial cells, acute ethanol treatment still caused steatosis and fibrogenesis and both could be blocked by Kdrl inhibition. We propose that in acute ALD, steatosis and fibrogenesis can be uncoupled from angiogenesis. VEGF signaling regulates activation of hepatic stellate cells, which in turn maintains steatosis in hepatocytes. Although anti-VEGF agents seem to have beneficial effects on multiple aspects of acute ALD, our data showed that blockade of VEGF signaling did not prevent fibrogenesis in the presence of ethanol. In this regard, our zebrafish study has provided insightful assessment for the use of anti-VEGF agents in acute ALD treatment: they may promote liver recovery from alcohol-induced injury upon cessation of alcohol consumption, but may not be useful for individuals with an active alcohol addiction.

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)

NAFLD is characterized by excessive fat accumulation in the liver that is not related to alcohol overconsumption [68]. It also has a broad spectrum of disorders, including steatosis, steatohepatitis, fibrosis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma. NAFLD is closely associated with insulin resistance, fatty diet, drug-induced liver injury, and metabolic syndromes. Due to the increasing prevalence of obesity and type II diabetes, NAFLD has become the fastest rising cause of chronic liver disease worldwide [69]. Similar to human, zebrafish develop hepatic steatosis in response to environmental triggers such as hepatotoxin, fasting, and diet containing high content of fat, cholesterol, or fructose (summarized in Table 2). Through reverse genetics, researchers have generated mutants and transgenic zebrafish to manipulate the function of known genes and investigate the molecular mechanisms underlying hepatic steatosis. The results of these studies have been reviewed by others [19] and are listed in Table 2. Forward genetic screen in zebrafish identified several mutants with hepatic steatosis. foie gras (foigr) mutant was the first genetic zebrafish model of fatty liver disease that was isolated in a screen for hepatomegaly [42]. The foigr gene is the zebrafish ortholog of human trafficking protein particle complex 11/TRAPPC11 that is involved in ER-to-Golgi trafficking [70]. Loss of TRAPPC11 function causes UPR responses and ER stress contributing to steatosis [42, 66, 71]. In other liver morphology-based screens, Thakur et al. reported a mutant of CDP-diacylglycerol-inositol 3-phosphatidyltransferase and connected phosphatidylinositol synthesis with ER stress and steatosis [72]. Nussbaum et al. identified a guanosine monophosphate synthetase mutant in which reduced production of reactive oxygen species resulted in hepatic steatosis [73]. Several groups have incorporated oil-red-o staining into the genetic screens to effectively detect steatosis. The redmoon mutant carries a mutation in the slc16a6a gene that encodes a ketone body β-hydroxybutyrate transporter [74]. Characterization of this mutant revealed a previously unrecognized role of hepatic ketone body transport in fasting-induced steatosis. A recent large-scale forward screen isolated 19 novel mutants displaying hepatomegly and/or steatosis during post-developmental stages [75]. It is anticipated that identification of the underlying mutations and the affected molecular pathways will advance our understanding of NAFLD etiology.

Table 2.

Zebrafish models of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

| A. Chemical treatment. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Chemical | Phenotype and Mechanism | Reference | ||

| Fructose | ER stress, mitochondrial dilation and activation of mTOR pathway. | [1] | ||

| Tunicamycin, Thapsigargin, Brefeldin A | Activation of unfolded protein response (UPR) pathways. | [2] | ||

| γ-hexachloro-cyclohexane | Oxidative stress leading to ER stress and mitochondrial malfunction. | [3, 4] | ||

| Thioacetamide (TAA) | Increased apoptosis, lipogenesis and lipid peroxidation. | [5, 6] | ||

| Perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) | Inhibition of β-oxidation coupled with activation of the nuclear hormone receptors peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPARα) and constitutive androstane receptor/pregnane X receptor (CAR/PXR). | [7, 8] | ||

| Tributyltin (TBT) | Impaired triglyceride accumulation and transcriptional regulation of lipid metabolism. | [9] | ||

| Amiodarone | Altered lipid homeostasis. | [10] | ||

| Bisphenol A (BPA) | Upregulation of the endocannabinoid system that induces steatosis. | [11] | ||

|

| ||||

| B. Dietary treatment. | ||||

|

| ||||

| Diet | Mechanism | Reference | ||

|

| ||||

| High fat diet High fat plus high cholesterol diet | Obesity-related steatosis | [12–16] | ||

|

| ||||

| C. Genetic mutants. | ||||

|

| ||||

| Mutant | Gene Function | Liver phenotype | Reference | |

|

| ||||

|

foie

gras/trappc11 |

ER-to-Golgi trafficking | Hepatic steatosis; impaired hepatic function. | [17–19] | |

| ducttrip/ahcy | Methionine metabolism | Hepatic steatosis; mitochondrial dysfunction; liver degeneration. | [20] | |

| cdipt | Phospholipid synthesis | Hepatic steatosis due to ER stress and defects in de novo phosphatesitol synthesis. | [21] | |

| sec63 | ER-associated protein involved in translocation of glycoproteins | ER stress and hepatic steatosis. | [22] | |

| gmps | Guanosine monophosphate synthetase | Steatosis due to down-regulated activity of the small GTPase Rac1 and ROS production. | [23] | |

| stk11 | Serine/Threonine kinase 11 regulating phosphorylation of the nutritional sensor AMP-kinase | Fasting-induced hepatic steatosis; glycol depletion. | [24] | |

| red moon/ slc16a6a | β-hydroxybutyrate transporter required for hepatocyte secretion of ketone bodies during fasting. | Increased neutral lipids and induction of hepatic lipid biosynthetic genes when fasted. | [25] | |

| slc7a3a | Arginine transporter required for arginine-dependent nitric oxide synthesis. | Fasting-induced steatosis. | [26] | |

| mbtps1 | Membrane-bound transcription factor peptidase site 1 | The mutant is protected from chronic ER stress-induced steatosis. | [27] | |

|

cnr1 cnr2 |

Cannabinoid receptor | Adult cnr2 mutants are susceptible to hepatic steatosis, and show impaired methionine metabolism. cnr1 mutants are protected from steatosis. | [28] | |

| socs1a | Suppressor of cytokine signaling-1a | Hepatic steatosis and insulin resistance linked to elevated Jak- STAT5 signaling | [29] | |

|

| ||||

| D. Transgenic models. | ||||

|

| ||||

| Transgenic line | Transgene expressed | Liver phenotype | Mechanism | Reference |

|

| ||||

| Tg(-2.8fabp10a:HBV.HBx- GFP) | Hepatitis B virus X protein (HBx) | Hepatic steatosis, hepatitis, liver hypoplasia. | Increased lipogenesis, fatty acid synthesis, lobular inflammation. | [30] |

| Tg(fabp10a:GFP-gank) | ankyrin repeat protein (gankyrin) | Hepatic steatosis, increased hepatocyte apoptosis and liver failure. | Alteration of lipid metabolism, increased expression of microRNAs. | [31] |

| Tg(fabp10a:dnfgfr1- EGFP) | dominant-negative fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 (dnfgfr1) | Hepatic steatosis, cholestasis, ballooning degeneration of hepatocytes. | Perturbation of lipid and bile metabolism | [32] |

| Tg(fabp10a:EGFP-YY1) | ubiquitous transcription factor yin yang 1 (yy1) | Hepatic steatosis. | Accumulation of hepatic triglycerides (TGs) by inhibiting CHOP-10 expression | [33] |

| Tg(fabp10a:Tetoff- CB1R:2A:eGFP) | cannabinoid receptor 1 (cb1r) | Hepatic steatosis. | Stimulates Srepb-1c, Acc1 and Fas expression. | [34] |

|

Tg(actb2:EGFP-nr1h3)

Tg(fabp2:EGFP-nr1h3) |

Global (actb2 promoter) or intestinal (fabp2 promoter) expression of Liver X receptor (nrlh3) | Global overexpression of nrlh3 induces steatosis; Intestine- specific overexpression suppresses steatosis caused by high-fat diet. | Overexpression of nrlh3 in the intestine affects transport of lipids to the liver. | [35] |

Reference

Sapp V, Gaffney L, EauClaire SF, Matthews RP. Fructose leads to hepatic steatosis in zebrafish that is reversed by mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibition. Hepatology. 2014;60(5):1581–92. doi:10.1002/hep.27284.

Vacaru AM, Di Narzo AF, Howarth DL, Tsedensodnom O, Imrie D, Cinaroglu A et al. Molecularly defined unfolded protein response subclasses have distinct correlations with fatty liver disease in zebrafish. Dis Model Mech. 2014;7(7):823–35. doi:10.1242/dmm.014472.

Braunbeck T, Gorge G, Storch V, Nagel R. Hepatic steatosis in zebra fish (Brachydanio rerio) induced by long-term exposure to gamma-hexachlorocyclohexane. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 1990;19(3):355–74.

Radosavljevic T, Mladenovic D, Jakovljevic V, Vucvic D, Rasc-Markovic A, Hrncic D et al. Oxidative stress in liver and red blood cells in acute lindane toxicity in rats. Human & experimental toxicology. 2009;28(12):747–57. doi:10.1177/0960327109353055.

Amali AA, Rekha RD, Lin CJ, Wang WL, Gong HY, Her GM et al. Thioacetamide induced liver damage in zebrafish embryo as a disease model for steatohepatitis. Journal of biomedical science. 2006;13(2):225–32. doi:10.1007/s11373-005-9055-5.

Hammes TO, Pedroso GL, Hartmann CR, Escobar TD, Fracasso LB, da Rosa DP et al. The effect of taurine on hepatic steatosis induced by thioacetamide in zebrafish (Danio rerio). Digestive diseases and sciences. 2012;57(3):675–82. doi:10.1007/s10620-011-1931-4.

Fai Tse WK, Li JW, Kwan Tse AC, Chan TF, Hin Ho JC, Sun Wu RS et al. Fatty liver disease induced by perfluorooctane sulfonate: Novel insight from transcriptome analysis. Chemosphere. 2016;159:166–77. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2016.05.060.

Cheng J, Lv S, Nie S, Liu J, Tong S, Kang N et al. Chronic perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) exposure induces hepatic steatosis in zebrafish. Aquat Toxicol. 2016;176:45–52. doi:10.1016/j.aquatox.2016.04.013.

Lyssimachou A, Santos JG, Andre A, Soares J, Lima D, Guimaraes L et al. The Mammalian "Obesogen" Tributyltin Targets Hepatic Triglyceride Accumulation and the Transcriptional Regulation of Lipid Metabolism in the Liver and Brain of Zebrafish. PLoS One. 2015;10(12):e0143911. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0143911.

Driessen M, Vitins AP, Pennings JL, Kienhuis AS, Water B, van der Ven LT. A transcriptomics-based hepatotoxicity comparison between the zebrafish embryo and established human and rodent in vitro and in vivo models using cyclosporine A, amiodarone and acetaminophen. Toxicol Lett. 2015;232(2):403–12. doi:10.1016/j.toxlet.2014.11.020.

Martella A, Silvestri C, Maradonna F, Gioacchini G, Allara M, Radaelli G et al. Bisphenol A Induces Fatty Liver by an Endocannabinoid-Mediated Positive Feedback Loop. Endocrinology. 2016;157(5):1751–63. doi:10.1210/en.2015-1384.

Oka T, Nishimura Y, Zang L, Hirano M, Shimada Y, Wang Z et al. Diet-induced obesity in zebrafish shares common pathophysiological pathways with mammalian obesity. BMC Physiol. 2010;10:21. doi:10.1186/1472-6793-10-21.

Tainaka T, Shimada Y, Kuroyanagi J, Zang L, Oka T, Nishimura Y et al. Transcriptome analysis of anti-fatty liver action by Campari tomato using a zebrafish diet-induced obesity model. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2011;8:88. doi:10.1186/1743-7075-8-88.

Hiramitsu M, Shimada Y, Kuroyanagi J, Inoue T, Katagiri T, Zang L et al. Eriocitrin ameliorates diet-induced hepatic steatosis with activation of mitochondrial biogenesis. Sci Rep. 2014;4:3708. doi:10.1038/srep03708.

Dai W, Wang K, Zheng X, Chen X, Zhang W, Zhang Y et al. High fat plus high cholesterol diet lead to hepatic steatosis in zebrafish larvae: a novel model for screening anti-hepatic steatosis drugs. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2015;12:42. doi:10.1186/s12986-015-0036-z.

Shimada Y, Kuninaga S, Ariyoshi M, Zhang B, Shiina Y, Takahashi Y et al. E2F8 promotes hepatic steatosis through FABP3 expression in diet-induced obesity in zebrafish. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2015;12:17. doi:10.1186/s12986-015-0012-7.

Sadler KC, Amsterdam A, Soroka C, Boyer J, Hopkins N. A genetic screen in zebrafish identifies the mutants vps18, nf2 and foie gras as models of liver disease. Development. 2005;132(15):3561–72. doi:10.1242/dev.01918.

Cinaroglu A, Gao C, Imrie D, Sadler KC. Activating transcription factor 6 plays protective and pathological roles in steatosis due to endoplasmic reticulum stress in zebrafish. Hepatology. 2011;54(2):495–508. doi:10.1002/hep.24396.

DeRossi C, Vacaru A, Rafiq R, Cinaroglu A, Imrie D, Nayar S et al. trappc11 is required for protein glycosylation in zebrafish and humans. Mol Biol Cell. 2016;27(8):1220–34. doi:10.1091/mbc.E15-08-0557.

Matthews RP, Lorent K, Manoral-Mobias R, Huang Y, Gong W, Murray IV et al. TNFalpha-dependent hepatic steatosis and liver degeneration caused by mutation of zebrafish S-adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase. Development. 2009;136(5):865–75. doi:10.1242/dev.027565.

Thakur PC, Stuckenholz C, Rivera MR, Davison JM, Yao JK, Amsterdam A et al. Lack of de novo phosphatidylinositol synthesis leads to endoplasmic reticulum stress and hepatic steatosis in cdipt-deficient zebrafish. Hepatology. 2011;54(2):452–62. doi:10.1002/hep.24349.

Monk KR, Voas MG, Franzini-Armstrong C, Hakkinen IS, Talbot WS. Mutation of sec63 in zebrafish causes defects in myelinated axons and liver pathology. Dis Model Mech. 2013;6(1):135–45. doi:10.1242/dmm.009217.

Nussbaum JM, Liu LJ, Hasan SA, Schaub M, McClendon A, Stainier DY et al. Homeostatic generation of reactive oxygen species protects the zebrafish liver from steatosis. Hepatology. 2013;58(4):1326–38. doi:10.1002/hep.26551.

van der Velden YU, Wang L, Zevenhoven J, van Rooijen E, van Lohuizen M, Giles RH et al. The serine-threonine kinase LKB1 is essential for survival under energetic stress in zebrafish. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2011;108(11):4358–63. doi:10.1073/pnas.1010210108.

Hugo SE, Cruz-Garcia L, Karanth S, Anderson RM, Stainier DY, Schlegel A. A monocarboxylate transporter required for hepatocyte secretion of ketone bodies during fasting. Genes Dev. 2012;26(3):282–93. doi:10.1101/gad.180968.111.

Gu Q, Yang X, Lin L, Li S, Li Q, Zhong S et al. Genetic ablation of solute carrier family 7a3a leads to hepatic steatosis in zebrafish during fasting. Hepatology. 2014;60(6):1929–41. doi:10.1002/hep.27356.

Passeri MJ, Cinaroglu A, Gao C, Sadler KC. Hepatic steatosis in response to acute alcohol exposure in zebrafish requires sterol regulatory element binding protein activation. Hepatology. 2009;49(2):443–52. doi:10.1002/hep.22667.

Liu LY, Alexa K, Cortes M, Schatzman-Bone S, Kim AJ, Mukhopadhyay B et al. Cannabinoid receptor signaling regulates liver development and metabolism. Development. 2016;143(4):609–22. doi:10.1242/dev.121731.

Dai Z, Wang H, Jin X, Wang H, He J, Liu M et al. Depletion of suppressor of cytokine signaling-1a causes hepatic steatosis and insulin resistance in zebrafish. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2015;308(10):E849–59. doi:10.1152/ajpendo.00540.2014.

Shieh YS, Chang YS, Hong JR, Chen LJ, Jou LK, Hsu CC et al. Increase of hepatic fat accumulation by liver specific expression of Hepatitis B virus X protein in zebrafish. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1801(7):721–30. doi:10.1016/j.bbalip.2010.04.008.

Her GM, Hsu CC, Hong JR, Lai CY, Hsu MC, Pang HW et al. Overexpression of gankyrin induces liver steatosis in zebrafish (Danio rerio). Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1811(9):536–48. doi:10.1016/j.bbalip.2011.06.011.

Tsai SM, Liu DW, Wang WP. Fibroblast growth factor (Fgf) signaling pathway regulates liver homeostasis in zebrafish. Transgenic research. 2013;22(2):301–14. doi:10.1007/s11248-012-9636-9.

Her GM, Pai WY, Lai CY, Hsieh YW, Pang HW. Ubiquitous transcription factor YY1 promotes zebrafish liver steatosis and lipotoxicity by inhibiting CHOP-10 expression. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1831(6):1037–51. doi:10.1016/j.bbalip.2013.02.002.

Pai WY, Hsu CC, Lai CY, Chang TZ, Tsai YL, Her GM. Cannabinoid receptor 1 promotes hepatic lipid accumulation and lipotoxicity through the induction of SREBP-1c expression in zebrafish. Transgenic research. 2013;22(4):823–38. doi:10.1007/s11248-012-9685-0.

Cruz-Garcia L, Schlegel A. Lxr-driven enterocyte lipid droplet formation delays transport of ingested lipids. J Lipid Res. 2014;55(9):1944–58. doi:10.1194/jlr.M052845.

Liver regeneration

Because specific anti-fibrotic therapies are not yet available, whole organ transplantation remains as the only effective treatment for end-stage liver diseases. Given the overwhelming epidemiology of chronic liver diseases, there is an urgent need for alternative therapeutic strategies. Hepatocyte replacement is a logical option, but hepatocytes do not propagate well in vitro. Obtaining large amount of hepatocytes is very costly and difficult because of the limited availability of donor livers. The growing new knowledge on stem cell biology has provided new avenue of cell therapy for liver diseases. Now it is possible to reprogram differentiated cells to a pluripotent state and convert them into hepatocytes and even mini-liver buds in culture [76, 77]. Studying liver regeneration in animal models has crucial implications for improving the current methodology of differentiating and propagating hepatocyte in vitro.

Liver has exceptional proliferative capacity that is often sufficient to repair itself after acute liver injury. Two-thirds partial hepatectomy (PH) in rodents is one of the most commonly used animal models for studying liver regeneration after acute injury [78, 79]. In PH, the liver regenerates through replication of existing hepatocytes. One-third PH has been performed in adult zebrafish [80]. The liver regains its original volume by 7 days after the surgery via compensatory growth of the remnant hepatocytes [81]. Analyses of genetic mutants and transgenic zebrafish have revealed important mediators of hepatocyte proliferation in PH, including the cell cycle regulator Uhrf1 [80], BMP, FGF [81], and Wnt signaling [82].

In massive or chronic liver injury where the proliferative capability of hepatocytes is severely compromised, facultative hepatic progenitor cells/stem cells may be activated to replenish the lost hepatocytes [83]. It has been proposed that hepatic progenitor cells/stem cells belong to the biliary lineage based on their ductal-like morphology and gene expression. By using an adenoassociated virus (AAV) vector that expresses Cre recombinase and loops out floxed sequences in all hepatocytes, several groups conducted hepatocyte lineage-tracing experiments in classic adult mouse liver injury models, including those that are thought to activate hepatic progenitor cells/stem cells [84–86]. In every model they tested, preexisting hepatocytes were the main source of regenerating hepatocytes. One plausible explanation is that despite the severity of hepatocellular damage in these models, sufficient number of hepatocytes have survived to regenerate the organ. In zebrafish, the nitroreductase-mediated cell ablation system driven by a hepatocyte-specific promoter is capable of eliminating nearly all hepatocytes [87]. Under this condition, Notch-active intrahepatic biliary cells have been shown to convert into hepatocytes to regenerate the liver [88–90]. Biliary-to-hepatocyte conversion is blocked in the mutants with bile duct paucity and liver regeneration is severely perturbed in these animals [89]. Choi et al. showed that the Wnt ligand Wnt2bb was required for the proliferation of biliary-derived new hepatocytes [88]. Luo group, on the other hand, demonstrated that the bile duct transcription factor Sox9b became activated upon hepatocyte ablation and was essential for biliary-to-hepatocyte conversion [89]. They also showed that inhibiting Notch signaling blocked Sox9b activation and biliary-to-hepatocyte conversion. Huang et al. extended the analyses on Notch signaling and revealed that the biliary cells experienced different levels of Notch signaling upon hepatocyte ablation. Low levels of Notch promoted the conversion whereas high levels of Notch inhibited the conversion [90]. It is noteworthy that most of the hepatocyte ablation studies were conducted at the larval stage when the liver was still rapidly developing. Some Notch-active cells might still be hepatoblasts rather than differentiated biliary cells. An increase of Notch-active cell number was seen in the adult zebrafish after hepatocyte ablation and some of them also turned on the hepatocyte marker expression [88, 90]. In mouse hepatocytes can enter an intermediate state in liver injury and express both biliary and hepatocyte markers [91]. It will be important to perform lineage-tracing experiments in adult zebrafish after hepatocyte ablation to distinguish whether the Notch-active cells also expressing hepatocyte markers are the biliary cells that undergo dedifferentiation to give rise to hepatocytes, or they are the surviving hepatocytes that become Notch-active in response to injury.

The ease of ablating hepatocytes and tracking liver regeneration in live zebrafish larvae have inspired researchers to conduct chemical screens to identify regulators of liver regeneration. Huang et al. found that liver regeneration was augmented by Wnt agonists and inhibited by Wnt antagonists and described a negative feedback loop between Notch and canonical Wnt signaling in hepatocyte regeneration. Ko et al. identified bromodomain and extraterminal domain (BET) inhibitors in the screen and showed that they blocked biliary-to-hepatocyte conversion when added during hepatocyte ablation [92]. When BET inhibitors were added after ablation, they suppressed the proliferation of newly formed hepatocytes and delayed their maturation. In human chronic liver diseases, the number of hepatic progenitor cells known as oval cells is correlated with disease severity [93, 94]. However, these cells have poor ability to regenerate liver. In this regard, compounds that promote biliary-to-hepatocyte conversion in zebrafish may have the potential to promote transdifferentiation of hepatic progenitor cells/biliary cells to hepatocytes in humans.

Conclusion and Future Perspectives

Zebrafish has been increasingly recognized as a valuable animal model for studying liver diseases and is complementary to the cell culture and rodent model systems. Further characterization of the zebrafish liver disease models will bring new insights into the molecular and cellular mechanisms underlying disease pathogenesis. Conducting high throughput forward genetic screens and chemical screens in zebrafish offers tremendous opportunity for identifying new therapeutic targets and treatment.

There are still many questions that need to be addressed in order to ensure the proper use of zebrafish in modeling liver diseases. Most zebrafish liver studies focus on the larval stage mainly for the following reasons: 1) zebrafish liver is already functional and contains all cell types at the larval stage. 2) 4- to 5-day old larva remains largely transparent, making it easy to observe the liver in vivo. 3) At this stage, zebrafish obtains nutrients almost exclusively from yolk. 4) Morpholino oligonucleotides can still effectively knockdown gene function during the larval stage. However, the larval phenotypes likely only mimic what occurs during early stages of liver diseases, but offer limited information on disease progression. There may not be enough time for fibrosis to develop in the larvae. The adaptive immune system is not mature at the larval stage [95], thus the hepatobiliary injury does not induce similar immune responses in zebrafish larvae as in patients. Therefore, it will be necessary to follow these models beyond the larval stage and investigate what aspects of the liver damage seen in patients can be recapitulated in zebrafish. Along the same line, although it is clear that environmental insults and genetic mutations can induce steatosis and hepatic stellate cell activation in zebrafish, neither advanced fibrosis nor cirrhosis has been reported. It could be due to the fact that not enough adult studies have been conducted. Differences in hepatocyte and cholangiocyte physiology could also be important contributing factors, but our knowledge on this topic is very limited. Lastly, measuring serum levels of alanine transaminase (ALT) and aspartate transaminase (AST) is the gold standard for evaluating liver function in patients and rodent models, and have been used in a few studies [96, 97]. It is important to further develop these assays in zebrafish so that one can more closely compare the liver phenotypes between species.

In this era of genomic analyses, GWAS has become a routine methodology to uncover genetic loci that are associated with disease phenotypes. The main challenge for the follow-up studies of patient GWAS is to determine which variants are indeed causative. Four groups have used zebrafish to validate GWAS variants in BA patients, as well as in patients with elevated liver enzyme levels [28, 98, 31, 29]. Furthermore, CRISPR/Cas9-mediated targeted mutagenesis can now be applied in zebrafish not only to generate null mutations, but also to precisely recapitulate the same mutations found in patients. It is also possible to mutagenize multiple targets in the same injected fish, allowing rapid testing of multiple candidate genes from GWAS [99]. When generating zebrafish mutants to validate GWAS variants, it is important to examine the liver phenotypes in both larva and adult. A deeper understanding of the zebrafish immune system and liver physiology is also needed to characterize the liver phenotypes that are related to immune responses and liver metabolism, respectively. Nevertheless, zebrafish represent an animal model that is an ideal combination of speed of testing, cost effectiveness, and homology to human. It is highly feasible to establish a pipeline for discoveries of candidate variants from patients, direct testing for biological relevance in zebrafish, and validate the findings in patients’ livers.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant R00AA020514 and a pilot award from Center of Pediatric Genomics in Cincinnati Children’s Hospital.

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Guidelines

Conflict of Interest: Duc-Hung Pham, Changwen Zhang, and Chunyue Yin declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent: All procedures performed in studies involving animals were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institute at which the studies were conducted.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as:

• Of importance

•• Of major importance

- 1.Pellicoro A, Ramachandran P, Iredale JP, Fallowfield JA. Liver fibrosis and repair: immune regulation of wound healing in a solid organ. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14(3):181–94. doi: 10.1038/nri3623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scaglione S, Kliethermes S, Cao G, Shoham D, Durazo R, Luke A, et al. The Epidemiology of Cirrhosis in the United States: A Population-based Study. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2015;49(8):690–6. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Santoriello C, Zon LI. Hooked! Modeling human disease in zebrafish. J Clin Invest. 2012;122(7):2337–43. doi: 10.1172/JCI60434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lu JW, Ho YJ, Yang YJ, Liao HA, Ciou SC, Lin LI, et al. Zebrafish as a disease model for studying human hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21(42):12042–58. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i42.12042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Si-Tayeb K, Lemaigre FP, Duncan SA. Organogenesis and development of the liver. Dev Cell. 2010;18(2):175–89. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gebhardt R, Matz-Soja M. Liver zonation: Novel aspects of its regulation and its impact on homeostasis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(26):8491–504. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i26.8491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lorent K, Yeo SY, Oda T, Chandrasekharappa S, Chitnis A, Matthews RP, et al. Inhibition of Jagged-mediated Notch signaling disrupts zebrafish biliary development and generates multi-organ defects compatible with an Alagille syndrome phenocopy. Development. 2004;131(22):5753–66. doi: 10.1242/dev.01411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boyer JL. Bile formation and secretion. Compr Physiol. 2013;3(3):1035–78. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c120027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yao Y, Lin J, Yang P, Chen Q, Chu X, Gao C, et al. Fine structure, enzyme histochemistry, and immunohistochemistry of liver in zebrafish. Anat Rec (Hoboken) 2012;295(4):567–76. doi: 10.1002/ar.22416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shin D, Shin CH, Tucker J, Ober EA, Rentzsch F, Poss KD, et al. Bmp and Fgf signaling are essential for liver specification in zebrafish. Development. 2007;134(11):2041–50. doi: 10.1242/dev.000281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Field HA, Ober EA, Roeser T, Stainier DY. Formation of the digestive system in zebrafish. I. Liver morphogenesis. Dev Biol. 2003;253(2):279–90. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(02)00017-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zong Y, Stanger BZ. Molecular mechanisms of bile duct development. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2011;43(2):257–64. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2010.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lorent K, Moore JC, Siekmann AF, Lawson N, Pack M. Reiterative use of the notch signal during zebrafish intrahepatic biliary development. Dev Dyn. 2010;239(3):855–64. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sakaguchi TF, Sadler KC, Crosnier C, Stainier DY. Endothelial signals modulate hepatocyte apicobasal polarization in zebrafish. Curr Biol. 2008;18(20):1565–71. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.08.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yin C, Evason KJ, Maher JJ, Stainier DY. The basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor, heart and neural crest derivatives expressed transcript 2, marks hepatic stellate cells in zebrafish: analysis of stellate cell entry into the developing liver. Hepatology. 2012;56(5):1958–70. doi: 10.1002/hep.25757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16•.Zhang C, Ellis JL, Yin C. Inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor signaling facilitates liver repair from acute ethanol-induced injury in zebrafish. Dis Model Mech. 2016;9(11):1383–96. doi: 10.1242/dmm.024950. This study investigated the molecular mechanisms underlying multiple pathogenic processes occuring during acute alcoholic liver injury and elucidated how steatosis, angiogenesis, and fibrogenesis are linked among each other. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Farber SA, Pack M, Ho SY, Johnson ID, Wagner DS, Dosch R, et al. Genetic analysis of digestive physiology using fluorescent phospholipid reporters. Science. 2001;292(5520):1385–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1060418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carten JD, Bradford MK, Farber SA. Visualizing digestive organ morphology and function using differential fatty acid metabolism in live zebrafish. Dev Biol. 2011;360(2):276–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19•.Asaoka Y, Terai S, Sakaida I, Nishina H. The expanding role of fish models in understanding non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Dis Model Mech. 2013;6(4):905–14. doi: 10.1242/dmm.011981. This is an excellent review of recent advances in using zebrafish to model NAFLD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Delous M, Yin C, Shin D, Ninov N, Debrito Carten J, Pan L, et al. Sox9b is a key regulator of pancreaticobiliary ductal system development. PLoS Genet. 2012;8(6):e1002754. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feldman AG, Sokol RJ. Neonatal Cholestasis. Neoreviews. 2013;14(2) doi: 10.1542/neo.14-2-e63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Balistreri WF, Bezerra JA. Whatever happened to "neonatal hepatitis"? Clin Liver Dis. 2006;10(1):27–53. v. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2005.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Verkade HJ, Bezerra JA, Davenport M, Schreiber RA, Mieli-Vergani G, Hulscher JB, et al. Biliary atresia and other cholestatic childhood diseases: Advances and future challenges. J Hepatol. 2016;65(3):631–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Asai A, Miethke A, Bezerra JA. Pathogenesis of biliary atresia: defining biology to understand clinical phenotypes. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;12(6):342–52. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2015.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Petersen C, Biermanns D, Kuske M, Schakel K, Meyer-Junghanel L, Mildenberger H. New aspects in a murine model for extrahepatic biliary atresia. J Pediatr Surg. 1997;32(8):1190–5. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(97)90680-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Petersen C, Grasshoff S, Luciano L. Diverse morphology of biliary atresia in an animal model. J Hepatol. 1998;28(4):603–7. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(98)80283-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Riepenhoff-Talty M, Schaekel K, Clark HF, Mueller W, Uhnoo I, Rossi T, et al. Group A rotaviruses produce extrahepatic biliary obstruction in orally inoculated newborn mice. Pediatr Res. 1993;33(4 Pt 1):394–9. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199304000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28••.Cui S, Leyva-Vega M, Tsai EA, EauClaire SF, Glessner JT, Hakonarson H, et al. Evidence from human and zebrafish that GPC1 is a biliary atresia susceptibility gene. Gastroenterology. 2013;144(5):1107–15. e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.01.022. This study provides an excellent example of how zebrafish can be used to validate variants from patient GWAS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tang V, Cofer ZC, Cui S, Sapp V, Loomes KM, Matthews RP. Loss of a Candidate Biliary Atresia Susceptibility Gene, add3a, Causes Biliary Developmental Defects in Zebrafish. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2016;63(5):524–30. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000001375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Omenetti A, Bass LM, Anders RA, Clemente MG, Francis H, Guy CD, et al. Hedgehog activity, epithelial-mesenchymal transitions, and biliary dysmorphogenesis in biliary atresia. Hepatology. 2011;53(4):1246–58. doi: 10.1002/hep.24156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ningappa M, So J, Glessner J, Ashokkumar C, Ranganathan S, Min J, et al. The Role of ARF6 in Biliary Atresia. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):e0138381. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32••.Lorent K, Gong W, Koo KA, Waisbourd-Zinman O, Karjoo S, Zhao X, et al. Identification of a plant isoflavonoid that causes biliary atresia. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7(286):286ra67. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa1652. This is the first animal study that confirms the involvement of environmental toxins in the pathogenesis of biliary atresia. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ••33.Zhao X, Lorent K, Wilkins BJ, Marchione DM, Gillespie K, Waisbourd-Zinman O, et al. Glutathione antioxidant pathway activity and reserve determine toxicity and specificity of the biliary toxin biliatresone in zebrafish. Hepatology. 2016;64(3):894–907. doi: 10.1002/hep.28603. This work demonstrated the critical role of glutathione-mediated redox signaling in the pathogenesis of toxin-induced BA. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Waisbourd-Zinman O, Koh H, Tsai S, Lavrut PM, Dang C, Zhao X, et al. The toxin biliatresone causes mouse extrahepatic cholangiocyte damage and fibrosis through decreased glutathione and SOX17. Hepatology. 2016;64(3):880–93. doi: 10.1002/hep.28599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matthews RP, Eauclaire SF, Mugnier M, Lorent K, Cui S, Ross MM, et al. DNA hypomethylation causes bile duct defects in zebrafish and is a distinguishing feature of infantile biliary atresia. Hepatology. 2011;53(3):905–14. doi: 10.1002/hep.24106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bezerra JA, Tiao G, Ryckman FC, Alonso M, Sabla GE, Shneider B, et al. Genetic induction of proinflammatory immunity in children with biliary atresia. Lancet. 2002;360(9346):1653–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11603-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shivakumar P, Campbell KM, Sabla GE, Miethke A, Tiao G, McNeal MM, et al. Obstruction of extrahepatic bile ducts by lymphocytes is regulated by IFN-gamma in experimental biliary atresia. J Clin Invest. 2004;114(3):322–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI21153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cofer ZC, Cui S, EauClaire SF, Kim C, Tobias JW, Hakonarson H, et al. Methylation Microarray Studies Highlight PDGFA Expression as a Factor in Biliary Atresia. PLoS One. 2016;11(3):e0151521. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0151521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Penton AL, Leonard LD, Spinner NB. Notch signaling in human development and disease. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2012;23(4):450–7. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2012.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cullinane AR, Straatman-Iwanowska A, Zaucker A, Wakabayashi Y, Bruce CK, Luo G, et al. Mutations in VIPAR cause an arthrogryposis, renal dysfunction and cholestasis syndrome phenotype with defects in epithelial polarization. Nat Genet. 2010;42(4):303–12. doi: 10.1038/ng.538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Matthews RP, Plumb-Rudewiez N, Lorent K, Gissen P, Johnson CA, Lemaigre F, et al. Zebrafish vps33b, an ortholog of the gene responsible for human arthrogryposis-renal dysfunction-cholestasis syndrome, regulates biliary development downstream of the onecut transcription factor hnf6. Development. 2005;132(23):5295–306. doi: 10.1242/dev.02140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sadler KC, Amsterdam A, Soroka C, Boyer J, Hopkins N. A genetic screen in zebrafish identifies the mutants vps18, nf2 and foie gras as models of liver disease. Development. 2005;132(15):3561–72. doi: 10.1242/dev.01918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wilkins BJ, Lorent K, Matthews RP, Pack M. p53-mediated biliary defects caused by knockdown of cirh1a, the zebrafish homolog of the gene responsible for North American Indian Childhood Cirrhosis. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e77670. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Srivastava A. Progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2014;4(1):25–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jceh.2013.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Annilo T, Chen ZQ, Shulenin S, Costantino J, Thomas L, Lou H, et al. Evolution of the vertebrate ABC gene family: analysis of gene birth and death. Genomics. 2006;88(1):1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2006.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Everson GT, Taylor MR, Doctor RB. Polycystic disease of the liver. Hepatology. 2004;40(4):774–82. doi: 10.1002/hep.20431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Masyuk T, Masyuk A, LaRusso N. Cholangiociliopathies: genetics, molecular mechanisms and potential therapies. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2009;25(3):265–71. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e328328f4ff. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tietz Bogert PS, Huang BQ, Gradilone SA, Masyuk TV, Moulder GL, Ekker SC, et al. The zebrafish as a model to study polycystic liver disease. Zebrafish. 2013;10(2):211–7. doi: 10.1089/zeb.2012.0825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gao H, Wang Y, Wegierski T, Skouloudaki K, Putz M, Fu X, et al. PRKCSH/80K-H, the protein mutated in polycystic liver disease, protects polycystin-2/TRPP2 against HERP-mediated degradation. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19(1):16–24. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Monk KR, Voas MG, Franzini-Armstrong C, Hakkinen IS, Talbot WS. Mutation of sec63 in zebrafish causes defects in myelinated axons and liver pathology. Dis Model Mech. 2013;6(1):135–45. doi: 10.1242/dmm.009217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Strazzabosco M, Somlo S. Polycystic liver diseases: congenital disorders of cholangiocyte signaling. Gastroenterology. 2011;140(7):1855–9. 9 e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.04.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cohen JI, Nagy LE. Pathogenesis of alcoholic liver disease: interactions between parenchymal and non-parenchymal cells. J Dig Dis. 2011;12(1):3–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-2980.2010.00468.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Louvet A, Mathurin P. Alcoholic liver disease: mechanisms of injury and targeted treatment. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;12(4):231–42. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2015.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lin JN, Chang LL, Lai CH, Lin KJ, Lin MF, Yang CH, et al. Development of an Animal Model for Alcoholic Liver Disease in Zebrafish. Zebrafish. 2015;12(4):271–80. doi: 10.1089/zeb.2014.1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Llerena S, Arias-Loste MT, Puente A, Cabezas J, Crespo J, Fabrega E. Binge drinking: Burden of liver disease and beyond. World J Hepatol. 2015;7(27):2703–15. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v7.i27.2703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bukong TN, Iracheta-Vellve A, Gyongyosi B, Ambade A, Catalano D, Kodys K, et al. Therapeutic Benefits of Spleen Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor Administration on Binge Drinking-Induced Alcoholic Liver Injury, Steatosis, and Inflammation in Mice. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2016;40(7):1524–30. doi: 10.1111/acer.13096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ki SH, Park O, Zheng M, Morales-Ibanez O, Kolls JK, Bataller R, et al. Interleukin-22 treatment ameliorates alcoholic liver injury in a murine model of chronic-binge ethanol feeding: role of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3. Hepatology. 2010;52(4):1291–300. doi: 10.1002/hep.23837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tsuchiya M, Ji C, Kosyk O, Shymonyak S, Melnyk S, Kono H, et al. Interstrain differences in liver injury and one-carbon metabolism in alcohol-fed mice. Hepatology. 2012;56(1):130–9. doi: 10.1002/hep.25641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chang B, Xu MJ, Zhou Z, Cai Y, Li M, Wang W, et al. Short- or long-term high-fat diet feeding plus acute ethanol binge synergistically induce acute liver injury in mice: an important role for CXCL1. Hepatology. 2015;62(4):1070–85. doi: 10.1002/hep.27921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gabele E, Dostert K, Dorn C, Patsenker E, Stickel F, Hellerbrand C. A new model of interactive effects of alcohol and high-fat diet on hepatic fibrosis. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2011;35(7):1361–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01472.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Passeri MJ, Cinaroglu A, Gao C, Sadler KC. Hepatic steatosis in response to acute alcohol exposure in zebrafish requires sterol regulatory element binding protein activation. Hepatology. 2009;49(2):443–52. doi: 10.1002/hep.22667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lassen N, Estey T, Tanguay RL, Pappa A, Reimers MJ, Vasiliou V. Molecular cloning, baculovirus expression, and tissue distribution of the zebrafish aldehyde dehydrogenase 2. Drug Metab Dispos. 2005;33(5):649–56. doi: 10.1124/dmd.104.002964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Reimers MJ, Flockton AR, Tanguay RL. Ethanol- and acetaldehyde-mediated developmental toxicity in zebrafish. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2004;26(6):769–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2004.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Reimers MJ, Hahn ME, Tanguay RL. Two zebrafish alcohol dehydrogenases share common ancestry with mammalian class I, II, IV, and V alcohol dehydrogenase genes but have distinct functional characteristics. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(37):38303–12. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401165200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65••.Howarth DL, Lindtner C, Vacaru AM, Sachidanandam R, Tsedensodnom O, Vasilkova T, et al. Activating transcription factor 6 is necessary and sufficient for alcoholic fatty liver disease in zebrafish. PLoS Genet. 2014;10(5):e1004335. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004335. This study provides systematic analyses on the contributions of unfolded protein responses to acute alcoholic liver disease. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cinaroglu A, Gao C, Imrie D, Sadler KC. Activating transcription factor 6 plays protective and pathological roles in steatosis due to endoplasmic reticulum stress in zebrafish. Hepatology. 2011;54(2):495–508. doi: 10.1002/hep.24396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tsedensodnom O, Vacaru AM, Howarth DL, Yin C, Sadler KC. Ethanol metabolism and oxidative stress are required for unfolded protein response activation and steatosis in zebrafish with alcoholic liver disease. Dis Model Mech. 2013;6(5):1213–26. doi: 10.1242/dmm.012195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Willebrords J, Pereira IV, Maes M, Crespo Yanguas S, Colle I, Van Den Bossche B, et al. Strategies, models and biomarkers in experimental non-alcoholic fatty liver disease research. Prog Lipid Res. 2015;59:106–25. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2015.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]