Abstract

It has long been known that pupils—the apertures that allow light into the eyes—dilate and constrict not only in response to changes in ambient light but also in response to emotional changes and arousing stimuli (e.g., Fontana, 1765). Charles Darwin (1872) related changes in pupil diameter to fear and other “emotions” in animals. For decades, pupillometry has been used to study cognitive processing across many domains, including perception, language, visual search, and short-term memory. Historically, such studies have examined the pupillary reflex as a correlate of attentional demands imposed by different tasks or stimuli—pupils typically dilate as cognitive demand increases. Because the neural mechanisms responsible for such task-evoked pupillary reflexes (TEPRs) implicate a role for memory processes, recent studies have examined pupillometry as a tool for investigating the cognitive processes underlying the creation of new episodic memories and their later retrieval. Here, we review the historical antecedents of current pupillometric research and discuss several recent studies linking pupillary dilation to the on-line consumption of cognitive resources in long-term-memory tasks. We conclude by discussing the future role of pupillometry in memory research and several methodological considerations that are important when designing pupillometric studies.

Keywords: pupillometry, recognition memory, attention

The declarative-memory system is often hypothesized to encompass two broad classes of memories, those that help us understand meanings and concepts (semantic memory) and those that help us remember everyday events and experiences. Tulving (1983) famously coined the term “episodic memory” to describe these latter memories, and researchers (e.g., Ebbinghaus, 1885/1962) have long investigated the structures and processes that support their successful encoding and retrieval. Not all episodic memories are created equal; they range from highly detailed recollections (e.g., “flashbulb” memories) to vague feelings of knowing (e.g., when you see someone who looks familiar in the grocery store but you cannot tell why he is familiar). All episodic memories, however, require neural processes—allocation of attention and other cognitive resources—during both encoding and retrieval. On-line measures of neural activity such as functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), event-related potentials (ERP), or single- unit recording can be used to investigate the demands that encoding and retrieval place on the cognitive system. These methods, however, can be expensive and time consuming and have inherent limitations (as does any single approach or measure). Thus, researchers have begun to (re)discover pupillometry, a cheap, efficient method to investigate cognitive effort.

Brief Historical Background

Interest in the pupillary reflex has been around for a long time; Loewenfeld (1958), for instance, cites Fontana (1765) as the earliest documentation of pupil dilation in the absence of changes in illumination (then known as “paradoxical pupil dilation”). Psychologists first began using such pupillary reflexes to systematically index mental activity in the 1960s. For example, Hess and colleagues reported that observers’ pupils dilated in response to positively valenced images, political statements consistent with their beliefs, and sexually arousing images (Hess, 1965; Hess, Seltzer, & Shlien, 1965). Based on this work, Hess concluded that the component of the pupil reflex reflecting mental activity indexed motivation, interest, and “emotionality” (Hess, 1965, p. 46). Hess is also credited with triggering long-lasting interest in the pupillary reflex as an index of cognitive demand when he noted that, during mental arithmetic, pupil diameters were larger during more difficult problems (Hess & Polt, 1964). Since that time, “cognitive” pupil dilation has been shown to be dissociable from “emotional” pupil dilation (Stanners, Coulter, Sweet, & Murphy, 1979).

Pupil Dilation as an Index of Cognitive Processing

The relationship between pupillary reflexes and cognitive processing has led some to suggest the pupil reflex reflects a “summed index” of brain activity during cognitive events (Kahneman & Beatty, 1966). Cognitively relevant pupil dilation occurs following inhibition of the parasympathetic nervous system or Edinger-Westphal nucleus (Steinhauer, Siegle, Condray, & Pless, 2004); these inhibitory processes are controlled by the locus coeruleus–norepinephrine system, which plays a critical role in the regulation of attentional control processes (Gilzenrat, Nieuwenhuis, Jepma, & Cohen, 2010). By carefully considering the reciprocal connections between these systems, researchers have linked pupillary reflexes to cognitive processing (Gianaros, Van der Veen, & Jennings, 2004). For example, in dark-adapted conditions, which inhibit the parasympathetic system, pupils still dilate in response to cognitive demand (Steinhauer & Hakerem, 1992). These task-evoked pupillary reflexes (TEPRs) correspond to phasic (i.e., event-related) activity in the locus coeruleus (Aston-Jones & Cohen, 2005), indicating high levels of attention. TEPRs occur independently of tonic reflexes, which occur following emotional arousal, stress, or changes in lighting (Karatekin, Couperus, & Marcus, 2004).

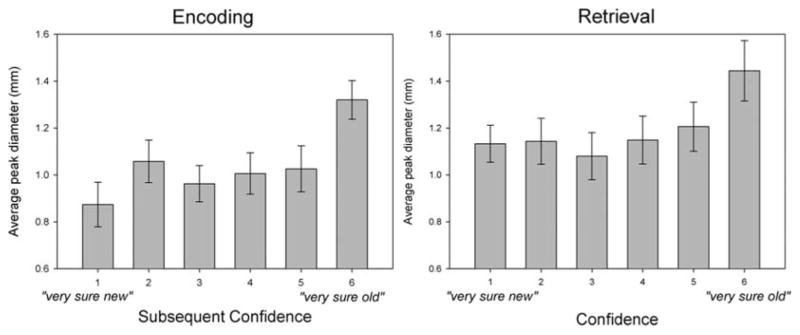

Although initiated by Hess, the best-known research on cognitive TEPRs was conducted by Kahneman and colleagues. In studies on mental processing load, Kahneman and Beatty (1966; Kahneman, Beatty, & Pollack, 1967) used time-locked pupil dilations to examine performance across mental tasks with varying levels of difficulty, observing a consistent pattern that has become a hallmark of TEPRs. In each study, as participants were placed under greater mental processing loads (e.g., more digits to retain in memory), their pupils dilated; as mental processing loads decreased (e.g., during recall periods), their pupils began to constrict (see Fig. 1). Because of their sensitivity to within- and between-task variations in cognitive demand and their ability to accurately reflect individual differences in cognitive ability, Kahneman (1973) used TEPRs as the primary index of processing load in his theory of attention.

Fig. 1.

Average pupil diameter before, during, and after presentation and retrieval of digits strings varying from 3 to 7 numbers. Slash marks are placed just before presentation of the first item and just after recall of the last item. Ticks on the x-axis indicate 1-second intervals. Adapted from “Pupil Diameter and Load on Memory,” by D. Kahneman & J. Beatty, 1966, Science, 154, p. 1584. Copyright 1966, American Association for the Advancement of Science. Adapted with permission.

The pupillary reflex declined in popularity as a dependent measure for some time (e.g., throughout the 1990s, only a handful of studies used pupillometry to investigate cognitive processes). Nevertheless, since the 1960s, it has been used to investigate signal detection (Beatty, 1982), variations in SAT scores (Ahern & Beatty, 1979), Stroop interference (Laeng, Ørbo, Holmlund, & Miozzo, 2011), working memory (Heitz, Schrock, Payne, & Engle, 2008), lexical decision (Kuchinke, Võ, Hofmann, & Jacobs, 2007), and visual search (Porter, Troscianko, & Gilchrist, 2007). In most cases, TEPRs have been used to examine capacity-limited processing in immediate or short-term-memory tasks, as theories of attention and working memory typically emphasize that cognitive processes deplete a limited pool of resources. This depletion is anticorrelated with pupil diameter; as resources are used, pupil diameters progressively increase. To date, however, few studies have investigated long-term-memory processes via pupillometry.

Pupil Dilation in Long-Term Encoding and Retrieval

As an index of brain activity, pupillary waveforms are similar in some respects to ERP waveforms (Beatty, 1982)—TEPRs extracted from the pupil waveform reflect central nervous system activity, just as ERPs reflect electroencephalographic activity. ERPs and other forms of neuroimaging (e.g., fMRI) have been used to compare the recruitment of cognitive and neural resources at encoding and retrieval in long-term-memory tasks, often using the subsequent-memory paradigm (e.g., Cansino & Trejo-Morales, 2008). In this paradigm, researchers record brain activity during a memory-encoding phase and use it to predict subsequent success or failure during a retrieval phase. The logic is that encoding should utilize the same processes and neural substrates that are recruited during successful retrieval. Moreover, the strength of memory should be observable from different patterns of activity during both encoding and retrieval.

Early studies of pupil size and memory revealed a surprising pattern. Gardner, Mo, and Borrego (1974) observed that nonsense syllables made familiar through pre-experimental exposure, relative to unfamiliar nonsense syllables, yielded enlarged pupils when they were presented a second time. Interest in this pupil old/new effect then disappeared until surprisingly recently: Võ and colleagues (2008) had participants study emotionally valenced words for a later recognition test. Although they did not observe any differences at encoding based on subsequent memory (i.e., whether the item would later be remembered or forgotten), they observed the pupil old/new effect during retrieval: Pupils were larger during correct “old” judgments, relative to correct “new” judgments.

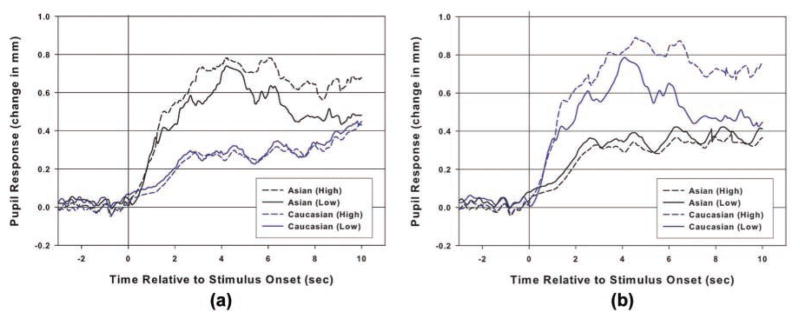

This effect was recently extended to encompass effects related to memory strength (Heaver & Hutton, 2011; Papesh & Goldinger, 2011).1 Otero, Weekes, and Hutton (2011) recently examined memory strength via the classic “remember/know” paradigm, and we (Papesh, Goldinger, & Hout, 2011) coupled overt confidence ratings with the subsequent-memory paradigm often used in ERP investigations. Participants studied spoken items and later discriminated old from new items, giving memory decisions and confidence judgments. In addition to observing the pupillary old/new effect, we found that high-confidence decisions were characterized by large pupils, relative to lower-confidence decisions. This pattern was evident during both encoding and retrieval (see Fig. 2). Note that had pupils only been assessed during the recognition test, the pattern during retrieval might suggest that high-confidence decisions reflect a qualitatively separate recollection process (Yonelinas, 2002). By assessing processing during encoding, we can appreciate that the story is more complicated: It appears that pupils dilate when people are confident in their memories, either as a feeling of strong recollection or as a feeling of future knowing.

Fig. 2.

Average peak pupil diameters during encoding (left panel) and retrieval (right panel) of spoken words, grouped expressed confidence in “old/new” decisions at retrieval. As shown in the illustration, pupils were enlarged when high-confidence memories were created (“very sure old”; left panel) and when they were retrieved (“very sure old”; right panel). Adapted from “Memory Strength and Specificity Revealed by Pupillometry,” by M. H. Papesh, S. D. Goldinger, & M. C. Hout, 2011, International Journal of Psychophysiology, 83, pp. 60–61. Copyright 2011, Elsevier. Adapted with permission.

With respect to the latter point, Kafkas and Montaldi (2011) recently examined incidental long-term memory for visual images in a modified remember/know task. Participants first viewed a series of images without instructions to remember them and were later given a surprise recognition test. Most often, the remember/know procedure is used to distinguish memories based on the contributions of detailed recollections and vague feelings of familiarity (reflecting two putatively separate memory systems that contribute to recognition). To examine both the strength and type of memory, Kafkas and Montaldi had participants use three familiarity responses (F1, F2, and F3), with each incremental increase reflecting an increase in strength, and a recollection response, which was to be used when participants could recall specific encoding details. Although the researchers did not find that pupil size dissociated recollection from familiarity, they observed differences based on memory strength; during incidental encoding, as subsequent memory strength increased, pupil diameter decreased.

This apparent contradiction from our findings (Papesh et al., 2011) is, in fact, consistent with the prior literature about papillary reflexes in visual cognition. According to Kafkas and Montaldi (2011), their procedure eliminated TEPRs during encoding, because they did not ask participants to actively encode the material. This, they argue, left only tonic changes free to vary, reflecting overall arousal levels during encoding. In contrast, we (Papesh et al., 2011) instructed participants to study material for an upcoming memory test, intentionally eliciting TEPRs. Because of differences in stimuli and instructions, the studies are difficult to directly compare. For example, it is well established that auditory stimuli elicit larger pupillary reflexes than visual stimuli do (Klinger, Tversky, & Hanrahan, 2011). It has also been argued that incidental and intentional encoding recruit different neural processes (Kapur et al., 1996).

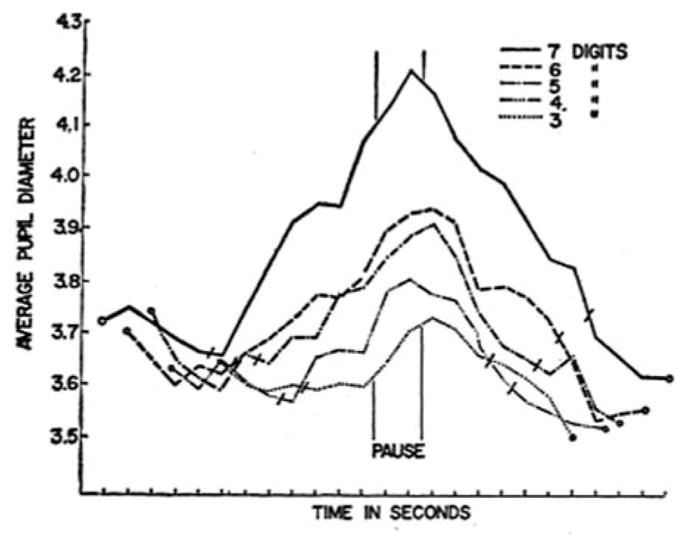

The utility of pupillometry to examine memory encoding is illustrated by a recent study in which we (Goldinger, He, & Papesh, 2009) examined intentional encoding of faces in an investigation of the own-race bias in face recognition. Participants studied own- and other-race faces for a later memory test. Following the test, participants were divided into low and high scorers depending on their cross-race recognition abilities. As shown in Figure 3, participants’ pupils during encoding predicted their subsequent memory performance. Not only did participants need to devote more cognitive resources to encoding the challenging, other-race faces (an effect replicated by Wu, Laeng, & Magnusson, 2011), but low-scoring participants selectively withdrew effort over time. Within and across trials, low-scoring participants’ pupils were less dilated, relative to those participants who successfully encoded most faces. Subjectively, it appeared as though low-scoring participants “gave up” as the trials progressed. Methodologically, pupillometry provided new insight into the relative cognitive demands of creating episodic memories for own- and other-race faces.

Fig. 3.

Average pupil dilation before and during encoding of same- and other-race faces for Caucasian participants (a) and Asian participants (b) as a function of subsequent-memory group (high- vs. low-scoring). Adapted from “Deficits in Cross-Race Face Learning: Insights From Eye-Movements and Pupillometry,” by S. D. Goldinger, Y. He, & M. H. Papesh, 2009, Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, & Cognition, 35, pp. 1113–1118. Copyright 2009, Springer. Adapted with permission.

Conclusions

Investigations into the pupillary reflex during encoding and retrieval from episodic memory are still relatively scarce, but recent investigations provide insight into the nature of the pupillary reflex, specifically as it indexes cognitive resources during processing. Just as ERP and fMRI can be used to investigate subsequent memory performance, pupillometry can be used as a cheap and efficient means to accomplish the same goals. Standard recognition-memory paradigms allow researchers to examine the end product of memories, the actual response or decision, the response/decision time, and subjective memory strength. Pupillometry allows researchers to examine populations that are typically challenging to study, including preverbal infants (Jackson & Sirois, 2009) and amnesics (Laeng et al., 2007). Further, one of the primary benefits to utilizing pupillometry to study recognition memory is that it allows researchers to examine information that is typically obscured—the resources devoted to encoding and the objective neurophysiological reflection of subjective memory strength. Such data have the potential to greatly inform our view of recognition memory by widening the “window” of data collection.

Empirical Considerations

Kahneman (1973) identified three criteria that must be met for physiological measures to index cognitive effort: He suggested that (a) the measure must reliably reflect differences in difficulty within a single task (e.g., a digit recall task with 2 vs. 5 numbers), (b) the measure must reliably reflect differences in difficulty between tasks (e.g., digit recall vs. tone detection), and (c) the measure must reliably reflect individual differences in ability. In a subsequent review, Beatty (1982) concluded that the pupil reflex fulfills Kahneman’s three criteria and is thus an adequate measure of cognitive demand.

Standard eye trackers, recording at 50-Hz or more, are capable of recording accurate pupil measurements, providing a rich data source. However, researchers who wish to utilize pupillometry should take precautions to avoid unwanted tonic reflexes. Porter and Troscianko (2003) identified several methodological approaches that minimize unwanted pupillary reflexes, including the use of relatively low stimulus contrast, avoiding colored stimuli, and using relatively long stimulus-exposure durations (TEPRs occur roughly 100 milliseconds after the onset of cognitive demand; Kuchinke et al., 2007). Investigations into long-term memory often use words as stimuli; although the foregoing considerations are less worrisome with spoken material, printed words can be equated for visual features, minimizing differences across old and new words (e.g., few/pew). Trials should also be temporally separated by at least 2 or 3 seconds to allow the pupils to constrict before the next trial.

In terms of analysis, researchers typically analyze baseline-corrected diameters; this is done by subtracting a trial-by-trial average, collected while the participant fixates a cross or blank screen, from the remaining waveform. This procedure eliminates tonic pupillary influences, such as those caused by variations in general arousal and carry-over effects (e.g., if trial n was difficult, the starting diameter in trial n + 1 may be artificially enlarged). Although peak diameter is more commonly analyzed, some researchers (e.g., Klinger et al., 2011) prefer to use mean diameter, because peak diameter is more susceptible to noise. Additional measures can include the length of time (latency) to waveform peak (reflecting the gradual consumption of cognitive resources), the area under the waveform (reflecting overall cognitive demand), and the respective slopes of the waveform rise and fall periods.

By incorporating a handful of stimulus and procedural controls, researchers can use pupillometry to discover a great deal about the creation and retrieval of episodic memories. Long-term memory is ideally suited for pupillometric investigation, as TEPRs can be assessed across different key periods and can be associated with other behavioral indices. Although Kahneman (1973) made the case for pupillometry as a cognitive measure nearly 40 years ago, memory research using this methodology has only just begun: Future work will provide new information about memory creation, complementing the existing literature on memory retrieval.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to Erik Reichle and Bruno Laeng for valuable feedback on this article.

Footnotes

It is interesting to note that the phenomenological experience of memory seems to be required to elicit a pupil old/new effect. Amnesic patients demonstrate the opposite pattern (Laeng et al., 2007): When their pupils are monitored during a recognition test, dilation seems to reflect stimulus novelty rather than memory.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared that they had no conflicts of interest with respect to their authorship or the publication of this article.

References

- Ahern S, Beatty J. Pupillary responses during information processing vary with scholastic aptitude test scores. Science. 1979;205:1289–1292. doi: 10.1126/science.472746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aston-Jones G, Cohen JD. Adaptive gain and the role of the locus coeruleus–norepinephrine system in optimal performance. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 2005;493:99–110. doi: 10.1002/cne.20723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beatty J. Task-evoked pupillary responses, processing load, and the structure of processing resources. Psychological Bulletin. 1982;91:276–292. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.91.2.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cansino S, Trejo-Morales P. Neurophysiology of successful encoding and retrieval of source memory. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience. 2008;8:85–98. doi: 10.3758/CABN.8.1.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darwin C. The expression of emotion in animals and man. London, England: Murray; 1872. [Google Scholar]

- Ebbinghaus H. Memory: A contribution to experimental psychology. New York, NY: Dover; 1962. (Original work published 1885) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontana F. Dei moti dell’iride [Motions of the Iris] Lucca, Italy: J. Giusti; 1765. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner RM, Mo SS, Borrego R. Inhibition of pupillary orienting reflex by novelty in conjunction with recognition memory. Bulletin of the Psychonomic Society. 1974;3:237–238. [Google Scholar]

- Gianaros PJ, Van Der Veen FM, Jennings JR. Regional cerebral blood flow correlates with heart period and high-frequency heart period variability during working-memory tasks: Implications for the cortical and subcortical regulation of cardiac autonomic activity. Psychophysiology. 2004;41:521–530. doi: 10.1111/1469-8986.2004.00179.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilzenrat MS, Nieuwenhuis S, Jepma M, Cohen JD. Pupil diameter tracks changes in control state predicted by the adaptive gain theory of locus coeruleus function. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience. 2010;10:252–269. doi: 10.3758/CABN.10.2.252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldinger SD, He Y, Papesh MH. Deficits in cross-race face learning: Insights from eye-movements and pupillometry. Memory & Cognition. 2009;35:1105–1122. doi: 10.1037/a0016548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaver B, Hutton SB. Keeping an eye on the truth? Pupil size changes associated with recognition memory. Memory. 2011;19:398–405. doi: 10.1080/09658211.2011.575788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heitz RP, Schrock JC, Payne TW, Engle RW. Effect of incentive on working memory capacity: Behavioral and pupillometric data. Psychophysiology. 2008;45:119–129. doi: 10.111/j.1469-8986.2007.00605.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess EH. Attitude and pupil size. Scientific American. 1965;212:46–54. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0465-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess EH, Polt JM. Pupil size in relation to mental activity during simple problem-solving. Science. 1964;143:1190–1192. doi: 10.1126/science.143.3611.1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess EH, Seltzer AL, Shlien JM. Pupil response of hetero- and homosexual males to pictures of men and women: A pilot study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1965;70:165–168. doi: 10.1037/h0021978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson I, Sirois S. Infant cognition: Going full factorial with pupil dilation. Developmental Science. 2009;12:670–679. doi: 10.111/j.1467-7687.2008.00805.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kafkas A, Montaldi D. Recognition memory strength is predicted by pupillary responses at encoding while fixation patterns distinguish recollection from familiarity. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 2011;64:1971–1989. doi: 10.1080/17470218.2011.588335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman D. Attention and effort. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman D, Beatty J. Pupil diameter and load on memory. Science. 1966;154:1583–1585. doi: 10.1126/science.154.3756.1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman D, Beatty J, Pollack I. Perceptual deficit during a mental task. Science. 1967;157:218–219. doi: 10.1126/science.157.3785.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapur S, Tulving E, Cabeza R, McIntosh AR, Houle S, Craik FIM. The neural correlates of intentional learning of verbal materials: A PET study. Cognitive Brain Research. 1996;4:243–249. doi: 10.1016/S0926-6410(96)00058-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karatekin C, Couperus JW, Marcus DJ. Attention allocation on the dual task paradigm as measured through behavioral and psychophysiological responses. Psychophysiology. 2004;41:175–185. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2004.00147.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klinger J, Tversky B, Hanrahan P. Effects of visual and verbal presentation on cognitive load in vigilance, memory, and arithmetic tasks. Psychophysiology. 2011;48:323–332. doi: 10.111/j.1469-8986.2010.01069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuchinke L, Võ ML, Hofmann M, Jacobs AM. Pupillary responses during lexical decisions vary with word frequency but not emotional valence. International Journal of Psychophysiology. 2007;65:132–140. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laeng B, Ørbo M, Holmlund T, Miozzo M. Pupillary Stroop effects. Cognitive Processes. 2011;12:13–21. doi: 10.1007/s10339-010-0370-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laeng B, Waterloo K, Johnson SH, Bakke SJ, Låg T, Simonsen SS, Høgsæt J. The eyes remember it: Oculography and pupillometry during recollection in three amnesic patients. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2007;19:1888–1904. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2007.19.11.1888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loewenfeld IE. Mechanisms of reflex dilation of the pupil: Historical review and experimental analysis. Documenta Ophthalmologica. 1958;12:185–448. doi: 10.1007/BF00913471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otero SC, Weekes BS, Hutton SB. Pupil size changes during recognition memory. Psychophysiology. 2011;48:1346–1353. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2011.01217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papesh MH, Goldinger SD. Your effort is showing! Pupil dilation reveals memory heuristics. In: Higham P, Leboe J, editors. Constructions of remembering and metacognition. London, England: Palgrave Macmillan; 2011. pp. 215–224. [Google Scholar]

- Papesh MH, Goldinger SD, Hout MC. Memory strength and specificity revealed by pupillometry. International Journal of Psychophysiology. 2011;83:56–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter G, Troscianko T. Pupillary response to grating stimuli. Perception. 2003;32:156. doi: 10.1068/p5438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter G, Troscianko T, Gilchrist ID. Effort during visual search and counting: Insights from pupillometry. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 2007;60:211–229. doi: 10.1080/17470210600673818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanners RF, Coulter M, Sweet AW, Murphy P. The pupillary response as an indicator of arousal and cognition. Motivation and Emotion. 1979;3:319–340. doi: 10.1007/BF00994048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Steinhauer SR, Hakerem G. The pupillary response in cognitive psychophysiology and schizophrenia. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1992;658:182–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1992.tb22845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinhauer SR, Siegle GJ, Condray R, Pless M. Sympathetic and parasympathetic innervations of pupillary dilation during sustained processing. International Journal of Psychophysiology. 2004;52:77–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2003.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tulving E. Elements of episodic memory. Oxford, England: Clarendon; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Võ ML, Jacobs AM, Kuchinke L, Hofmann M, Conrad M, Schacht A, Hutzler F. The coupling of emotion and cognition in the eye: Introducing the pupil old/new effect. Psychophysiology. 2008;45:30–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2008.00745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu EXW, Laeng B, Magnusson S. Through the eyes of the own-race bias: Eye-tracking and pupillometry during face recognition. Social Neuroscience. 2011:1–15. doi: 10.1080/17470919.2011.596946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yonelinas AP. The nature of recollection and familiarity: A review of 30 years of research. Journal of Memory and Language. 2002;46:441–517. doi: 10.1006/jmla.2002.2864. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Recommended Reading

- Beatty J. Provides a comprehensive discussion of TEPRs and the manner by which they represent cognitive demand/processing load in psychological tasks 1982 (See References) [Google Scholar]

- Goldwater BC. Psychological significance of pupillary movements. Psychological Bulletin. 1975;77:340–355. doi: 10.1037/h0032456. Provides a nice overview of the mechanisms involved in tonic and phasic pupil dilations, as well as some inherent limitations in the use of pupillometry. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kafkas A, Montaldi D. Provides a nice overview of the neurophysiology of the pupillary reflex, as well as evidence from an implicit long-term recognition memory paradigm using visual stimuli 2011 (See References) [Google Scholar]

- Laeng B, Sirois S, Gredebäck G. Pupillometry: A window to the preconscious? Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2012;7:18–27. doi: 10.1177/1745691611427305. Provides a brief but thorough review of the neurophysiological findings relevant to TEPRs, focusing extensively on the role of the locus coeruleus–norepinephrine system. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papesh MH, Goldinger SD, Hout MC. (See References). Provides an overview of TEPRs and evidence from a long-term recognition memory paradigm using intentional encoding of spoken words 2011 [Google Scholar]