Purpose

Residency poses challenges for residents’ personal relationships. Research suggests residents rely on family and friends for support during their training. The authors explored the impact of residency demands on residents’ personal relationships and the effects changes in those relationships could have on their wellness.

Method

The authors used a constructivist grounded theory approach. In 2012–2014, they conducted semistructured interviews with a purposive and theoretical sample of 16 Canadian residents from various specialties and training levels. Data analysis occurred concurrently with data collection, allowing authors to use a constant comparative approach to explore emergent themes. Transcripts were coded; codes were organized into categories and then themes to develop a substantive theory.

Results

Residents perceived their relationships to be influenced by their evolving professional identity: Although personal relationships were important, being a doctor superseded them. Participants suggested they were forced to adapt their personal relationships, which resulted in the evolution of a hierarchy of relationships that was reinforced by the work–life imbalance imposed by their training. This poor work–life balance seemed to result in relationship issues and diminish residents’ wellness. Participants applied coping mechanisms to manage the conflict arising from the adaptation and protect their relationships. To minimize the effects of identity dissonance, some gravitated toward relationships with others who shared their professional identity or sought social comparison as affirmation.

Conclusions

Erosion of personal relationships could affect resident wellness and lead to burnout. Educators must consider how educational programs impact relationships and the subsequent effects on resident wellness.

The prevalence of depression and anxiety,1,2 as well as burnout and lack of work–life balance,3,4 among residents demonstrates that residents struggle with wellness during their training. A recent systematic review highlighted the need for more rigorous research on wellness during residency.4 Researchers have shown that supportive personal relationships help residents maintain wellness5 and guard against depression,6 and that residents often rely on family and friends for help with mental health problems before they seek professional help.7,8

Residency training poses substantial challenges for residents’ personal relationships (i.e., with family, significant others, friends). The work-scheduling demands (e.g., shift schedules, call nights, rotations) and the geographic separation from family and social networks are two of the many factors that make residency difficult on relationships for some residents.1,9 However, the extent to which and how the demands of residency training affect residents’ personal relationships and, in turn, how changes in those relationships potentially impact resident wellness is not well understood.

In this qualitative study, we explored how residents’ personal relationships changed during residency and how residents responded to those changes. We were interested in the impact of residency demands on residents’ personal relationships and the effects that changes in those relationships could have on their wellness (i.e., work–life balance; sense of mental health, such as presence of depression, anxiety). By gaining a deeper understanding of how personal relationships change during residency, educators and researchers can begin to develop interventions to enhance residents’ relationships as a way to protect against the potential negative effects of training on wellness and foster resilience.10

Method

Building on existing knowledge,5–8 we used a constructivist grounded theory approach11 to develop a substantive theory of how residents’ personal relationships are affected by the demands of residency and how changes in these relationships might impact their wellness. This approach allowed for the discovery or evolution of theory through the analysis of data without a priori assumptions to test and, as such, was ideal for our study. We received ethics approval from the University of Toronto Research Ethics Board.

Participants

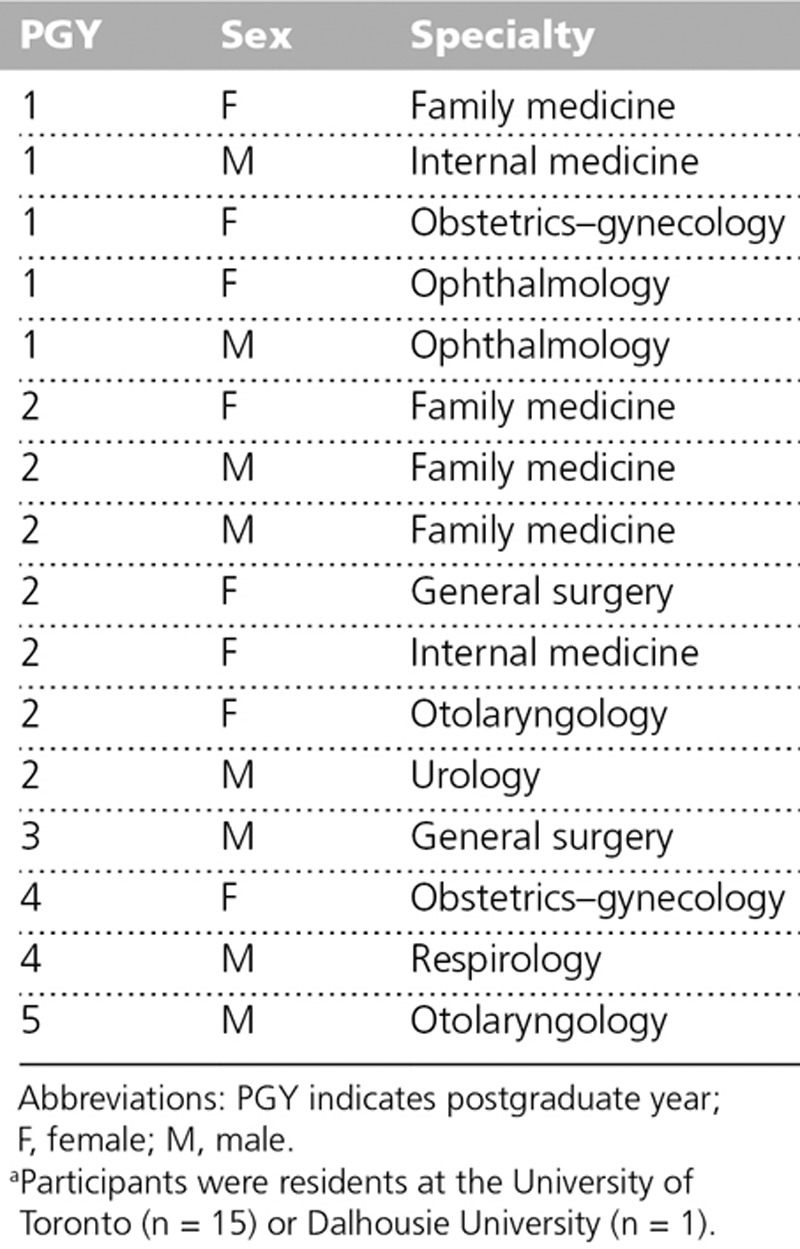

We conducted purposive and theoretical sampling of Canadian residents from various specialties to ensure that we had a diverse group of participants. Participants provided written consent and received a $20 gift card for their participation in the study interviews. Sampling continued until we reached a saturation of themes (i.e., the point in data collection at which no new dominant issues emerge, and all concepts in the substantive theory are well understood),11 resulting in a total of 16 participants. The participants represented a range of training years (postgraduate years 1–5) from eight specialties (see Table 1). Eight of the participants were female. Fifteen participants were residents at the University of Toronto, and one was a resident at Dalhousie University.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the 16 Canadian Residents Participating in Study Interviews, June 2012 to May 2014a

Data collection and analysis

Semistructured interviews with the participating residents were conducted in person or by telephone by three of the authors (M. Lam, D.W., P.V.) from June 2012 to May 2014. The interview guide questions (see Appendix 1) were adjusted to explore emergent themes. Interviews ranged from 25 to 56 minutes. The dialogue was audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Transcripts were deidentified (participant names were removed and labeled with assigned ID numbers) and entered into NVivo 10 (QSR International, Doncaster, Australia) for organization. Consistent with a constructivist grounded theory approach,11 we derived our hypotheses and concepts from the data during the course of the research. Data analysis occurred in tandem with data collection, with analysis beginning as soon as the first interview was conducted and continuing iteratively. Transcripts were coded line-by-line (P.V.), and codes were organized into categories and then themes. Over the course of data collection, we (M. Law., M.M., P.V.) met to discuss and refine the analysis, comparing new data with previously gathered data and existing analytic codes. This comparative and concurrent analysis subsequently resulted in the development of themes.11

Our preliminary analysis revealed theoretical questions requiring clarification and aspects of emerging themes needing further exploration, so we altered the interview guide to address these issues.12 The results of the ongoing data analysis informed subsequent data collection by helping refine the research questions, develop more targeted questioning, and guide purposive sampling of participants who might offer contrasting perspectives. This continued refinement of the research process allowed for the development of a substantive theory consisting of clearly defined concepts related to one another in a cohesive manner.11

Results

We identified four themes: the influence of an evolving professional identity on personal relationships; forced adaptation and a hierarchy of relationships; coping with relationship issues; and mitigating identity dissonance. Our findings demonstrate how participants’ personal relationships were influenced by their evolving professional identity, which led to forced adaptation of relationships by residents, including the development of a relationship hierarchy. Residents subsequently applied coping strategies to protect their relationships and sought to mitigate the identity dissonance they experienced between their personal and professional lives and the negative effects of this dissonance on their wellness.

The influence of an evolving professional identity on personal relationships

Participants perceived their personal relationships as being influenced by their evolving professional identity of becoming and being a doctor. As residents’ professional identity became more ingrained, they had less time for family and friends, and they modified their relationships.

[…] my role with respect to the type of friend or their expectations of me have changed because of how busy I am … I think that a bit of my relationships have suffered, but just because I’m not as available as I once was before I started medicine. (#10)

I think it would be hard for me to explain to someone who wasn’t in medicine. They could be an accountant, an economist, or in any other profession, but maybe if there was a difference in the degree of responsibility. It would be harder for me to explain why I have to do certain things the way that I do it if there was a difference in the degree of responsibility. (#11)

Maintaining personal obligations and relationships, while not compromising one’s professional identity, was important to all the residents. However, many residents explained that being a doctor superseded their personal relationships and suggested that residency was all-consuming (time, emotion, motivation, energy). As their professional identity developed and strengthened, residents seemed to forfeit or relinquish their personal relationships.

But I signed up for this kind of thing, I’m in it to become a doctor and become a competent physician, so I came into it knowing I would have to sacrifice a lot of my life, or my personal life, for it, so it’s frustrating, but you just have to do it. (#16)

I’ve missed lots of birthdays, lots of family gatherings and stuff, because of call. But … I care a lot about what my other fellow residents and what my staff think of me. And it keeps me working, right? (#06)

You have to do the job, and if you don’t want to do the job, then they shouldn’t pay you for the job, so personal life has to be second to that during work hours. (#11)

Yet, while participants reported that their personal relationships were often affected by residency demands, most identified support they received from family and friends. This support allowed residents to focus on their work and, for example, forgo personal responsibilities at home. Emotional support often took the form of understanding and empathy.

So, my wife has been amazing. She is very, very accommodating. She makes all the schedules between the nanny, me, and her. And she also actually works full-time as a physician, as well.… [B]ut because I can’t physically be at the house for long periods of time, I think that really has impacted her the most. (#13)

Life and death decisions are made, mistakes are made, surgical mistakes are made, and I think every doctor takes those home…. I think all doctors keep those in their minds and everybody deals with them in a different way. She helps me deal with those stresses, and they come out periodically and she just helps me get through them in a positive way. (#12)

Forced adaptation and a hierarchy of relationships

Most participants implied that they were forced to adapt their personal relationships and to manage others’ expectations about those relationships. Residents had their own convictions that the individuals in their lives needed to compromise and reconciled these beliefs as representing what these individuals could reasonably expect of them. Residents thought that their families and friends had come to anticipate these adjustments (of social plans and work schedules), particularly with respect to the amount of time they could spend together.

[…] you tend not to make commitments. Or if you do make commitments, you tell the person that there’s a chance you may not be there … I think my friends are used to it. I try to keep in touch with them even though I may not meet with them or see them face to face as often as I’d like. (#04)

Maybe, from medical school to, now, residency, people have gradually adapted to me not being around, anyway. So, yes, it is just a step further. But maybe the change is so gradual that no one really notices. (#13)

If you want to call me up then, I could go for lunch, whereas now it’s very structured. I will have dinner with you two weeks from now on a Tuesday because I know that I have my half-day and I’ll be out early. So it’s much more structured, much more organized and much more planned. Nothing is spontaneous.… I think people have to accept [it] because otherwise they’ll just be disappointed a whole lot. It’s not like I can modify things to accommodate other people. It’s like this is my schedule and if you are unhappy then wait five years until I graduate. (#14)

For many participants, this forced adaptation resulted in the evolution of a hierarchy of relationships, which seemed to be reinforced by the work–life imbalance imposed by residents’ training schedules. This hierarchy was portrayed by residents as a way to preserve the most important relationships: As greater time was consumed by the necessary work of residency, the remaining time could be focused on more valued relationships (i.e., significant other, family, close friends) and then on more-distant or less-cherished relationships and acquaintances.

I mentioned that you have to sort of prioritize your family, your significant other, and other people who you’re much closer with, and after scheduling them in between call and your clinical duties, you may not have as much time to spend with other people.… (#08)

I make time to talk to my boyfriend every night somehow. Obviously you have to prioritize. That’s exactly it; you have to see what is most important to you, and then go from there.… [I]t’s a hierarchy. (#16)

Coping with relationship issues

Poor work–life balance seemed to result in relationship problems. The disproportionate amount of time participants spent on work, compared with the time spent on personal relationships, seemed to diminish residents’ wellness and to manifest in a range of emotions, including anger, anxiety, fear, frustration, guilt, loss, regret, sadness, and self-doubt.

It’s just impossible to be a good friend to anyone, you know, I just don’t have the time or the energy. (#09)

I think the word “resentment” has come up a couple of times through my wife. But she also understands that, really, it is just the way the training is. I try to maximize my time the best that I can. Whenever I am not home, it is not like I am out with my friends or anything like that. I am home, playing with the baby and trying to help out as much as I can. (#13)

The perceived neglect and forced adaptation that eroded relationships was concerning to all participants, given the potential long-term ramifications. Participants applied coping mechanisms (e.g., adjusting social plans and work schedules, compromise, use of technology) to manage the conflict arising from the adaptation and to protect their relationships.

So I kind of have to look forward ahead of time and see what’s happening and fit my schedule around it. But of course, if there was a time when I really couldn’t fit my residency schedule around my activity, I would have to give up my activity for that month. (#07)

Maybe some of the things I have tried to do is explore other ways of maintaining some of those relationships or connections and things like sending things in the mail or talking on the phone more often, writing e-mails … if I was living in the same city, an e-mail or a message would be a very little thing. But here, it seems to amplify because it can still do more in maintaining those relationships a little better, I think. (#15)

Mitigating identity dissonance

Despite using coping strategies to navigate their relationships, residents articulated a strong identity dissonance—a clash between their professional and personal identities—that evoked conflicting emotions.

I never really call my parents. I call them once a week. You know, I don’t think I can say I’m really a contributing family member. I’m just not there. (#09)

But, in one sense, oftentimes there’s nothing you can do. So, with all the support and planning and organization, your work life will still have a significant influence on your personal life. (#15)

One way to minimize this dissonance was to gravitate toward relationships with others who shared their professional identity. Relationships with like-minded individuals helped residents justify or make sense of the negative feelings many were experiencing.

Being both in medicine, being really busy, has really helped, as well, because we have that mutual understanding, of you know, schedules. I don’t think if we weren’t both in medicine, I think it’d be a lot more difficult, for sure. (#01)

I think being a resident herself and knowing how busy it is when you’re on call and when you’re studying, and how stressful like our days can be, I think she understands when I get stressed out. Whereas I don’t know, if she wasn’t, if she didn’t know what we were going through, I don’t know if she would be more upset if I couldn’t call her some days or if I couldn’t make it home for a weekend because I’m on call or something. (#07)

Actively seeking out social comparison was a form of appraisal support (affirmation) that was important for some participants, as it supplied a comforting message of “I’m not alone”:

When I talk to my friends who are in Internal [Medicine] residency, they think I have this great life, less than 90 hours a week. And they think they have a good balance but they’re working 90 or 100 hours a week. Um, [laughs] and they still have time to do fun things too, but you know when I hear them talk it sounds like it’s taken over their life too. (#02)

But a lot of my colleagues who were really burdened with debt or had families and kids at that time, they couldn’t really escape, keep up with their hobbies, or things that kept them going, like people’s friends and family.… I didn’t really have that problem, and … I still have a lot more freedom. (#11)

Discussion

Maintaining personal relationships, while not compromising one’s professional identity, was important to residents participating in this study, but they suggested that being a physician superseded their personal relationships. As a result, residents were forced to adapt their relationships and develop a hierarchy, even though those relationships often were a source of support. This poor work–life balance, imposed by the demands of residency training, seemed to compromise residents’ wellness. Despite applying coping mechanisms to navigate their relationships, residents felt strong identity dissonance. One way some residents minimized this dissonance was to gravitate toward relationships with others who shared their professional identity. They also actively sought out social comparison to reinforce their relationship decisions.

Participants in our study described tension between their professional and personal identities and the resulting negative impact on their relationships. This is concerning because our data suggest that having a supportive personal relationship can affect resident wellness. Physician wellness (work–life balance, sense of mental health) is important given its impact on a practitioner’s ability to provide compassionate, patient-centered care.13–16 Ultimately, the erosion of relationships with family and friends could affect residents’ psychological well-being and lead to burnout. Burnout, in turn, could lead to further distress, such as alcohol abuse or dependence, suicidal ideation, higher risk of motor vehicle incidents, and greater relationship stress.3,17 Psychological symptoms of burnout include irritability, cynicism, and decreased concentration.18 Some researchers predict an even higher prevalence of burnout symptoms amongst trainees in the near future as a result of increasing training requirements, such as new competencies and more rigorous assessment.3

While duty hours restrictions have been proposed as a solution to minimize the negative impact of residency training on resident wellness,13 our study suggests that workload is not the only stressor. Our participants described workload intensity as being exacerbated by the strong professional identity associated with being a doctor. Participants’ sense of commitment to their work—part of their professional identity—affected their relationships and caused identity dissonance and negative emotions. Schaufeli and colleagues19 similarly highlighted the connection between burnout and role conflicts. An exaggerated sense of responsibility, guilt, self-doubt, perfectionism, desire for control, and drive to overwork can lead to self-neglect and disintegration of close relationships,20 thereby creating the potential for burnout. The concerning spin-off effect of this burnout is its impact on patient care. For example, junior doctors with burnout are prone to relating to patients in a more callous and cynical way (depersonalization).19 Burnout may also influence the size and specialty distribution of the physician workforce and, consequentially, patients’ access to care3 as trainees may make career choices based on factors such as working hours, job flexibility, and length of training time.21

Our findings suggest that the burdens (e.g., time and scheduling pressures, emotional angst) participants experienced, and to which they were required to adapt, predominantly arose from pressures of the training environment. These demands influenced residents’ professional identity development, their personal relationships, and, in turn, their wellness. The hierarchy of relationships that participants established to address these demands was a way of mitigating the effects of the poor work–life balance imposed by their training. These findings are supported by a narrative review by Dyrbye and Shanafelt,3 which cited factors within the learning and work environment, rather than individual characteristics, as the major determinants of doctors’ well-being and drivers of burnout. Slavin and colleagues22 similarly discussed the training environment as an overlooked component for interventions aimed at improving medical student mental health.

On the basis of these findings, we posit that curriculum structures—formal, informal, and hidden23—gave rise to and reinforced the poor work–life balance that residents experienced. Given these structural influences on residents’ wellness, interventions aimed at the individual (e.g., wellness seminars) may have less impact than broader solutions that focus on the root causes of burnout. Interventions with an emphasis on systems factors, such as the medical culture and the hidden curriculum, may be more likely to promote wellness and a healthy professional identity23,24 and may have a positive impact on residents’ personal relationships. As noted above, improving resident quality of life and preventing burnout will not be achieved by residents simply working fewer hours.18 A humanistic approach to residency reform will involve reframing the physician’s professional role as that of an integral member of a team for whole person care.25 Martimianakis and colleagues24 suggest that educators adopt a position that acknowledges that it is both necessary and valuable for humanism and the hidden curriculum to coexist within medical education, rather than seeing the hidden curriculum as something that is inherently bad. Doing so may provide insight into how the hidden curriculum contributes to resident wellness and provide educators with opportunities to develop broad, proactive interventions.

Limitations

Our study had some limitations. First, all of the participants were Canadian residents, primarily at one medical school. Second, our findings represent the experiences of a limited number of specialties. However, our aim was to provide a deeper understanding of the effects of residency on residents’ personal relationships rather than to generalize our findings to all residents. Given the importance of the training environment, we recommend that future research explore the relationships of residents from different training contexts to further understand the impact of curricula on wellness. In addition, as causation is not the goal of qualitative research, our study did not seek to establish such.

Conclusion

Our findings add to the debate regarding how best to promote and maintain resident wellness by highlighting that stressors go beyond workload; rather, professional identity plays a contributory role in resident wellness. We have offered some understanding of the tension between professional identity and personal relationships that is derived from the demands of the training environment. As educators, we must reflect on the impact of the design of educational programs on residents’ personal relationships and wellness. We must consider the roles of the formal, informal, and hidden curricula in educating our medical trainees, to foster healthy and humanistic physicians who will deliver good patient care.

Appendix 1

Final Semi-structured Interview Guide Used in Study: Interviews to Explore Changes in Residents’ Personal Relationships During Residency and the Effects of Those Changes on Residents’ Wellness, June 2012 to May 2014a

Questions

-

Demographics

-

•

Postgraduate year of training?

-

•

Specialty?

-

•

What does being a professional mean to you?

Have your personal relationships (family, friends, significant others) influenced your identity as a doctor? If so, how? Have your relationships influenced your choice of speciality? If so, how?

-

Tell me about your relationships.

Probe: What do your relationships look like? Nature of relationships—Serendipitous formation? Proximity formation with people you work with? How stable are these relationships?

How has it been for your families, significant other, or close friends dealing with you being a resident?

-

Have your personal relationships been affected/shaped by your residency training—and vice versa? If so, how?

Probe: How have your relationships changed since you’ve been a resident?

-

How do you feel about these changes in relationships?

Probes: How do you feel about the loss of relationships? Do you mourn the loss of relationships? Are you future looking? Are you resigned? Do you perceive this as a temporary feature?

-

How do you deal with the demands of residency versus those of your personal relationships? How do you deal with them when they are in direct conflict?

Probes: What strategies have you adopted to be able to maintain relationships? How do you prioritize? To what extent do you take your relationships for granted? Which ones?

Has your professional training thus far affected how you handle conflicting responsibilities/roles/demands professionally versus personally? If so, how?

Do you have any other comments?

End of interview

aQuestions were adjusted during the study to explore emergent themes.

Footnotes

An AM Rounds blog post on this article is available at academicmedicineblog.org.

Funding/Support: None reported.

Other disclosures: None reported.

Ethical approval: This project received ethics approval from the University of Toronto Research Ethics Board (protocol reference no. 27575).

Previous presentations: Portions of this study were presented at the Canadian Conference on Medical Education (CCME), Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, April 2015, and the International Conference on Residency Education, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, September 2013.

References

- 1.Mata DA, Ramos MA, Bansal N, et al. Prevalence of depression and depressive symptoms among resident physicians: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2015;314:2373–2383.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murphy JM, Laird NM, Monson RR, Sobol AM, Leighton AH. A 40-year perspective on the prevalence of depression: The Stirling County Study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:209–215.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dyrbye L, Shanafelt T. A narrative review on burnout experienced by medical students and residents. Med Educ. 2016;50:132–149.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raj KS. Well-being in residency: A systematic review. J Grad Med Educ. 2016;8:674–684.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weiner EL, Swain GR, Wolf B, Gottlieb M. A qualitative study of physicians’ own wellness-promotion practices. West J Med. 2001;174:19–23.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ozbay F, Johnson DC, Dimoulas E, Morgan CA, Charney D, Southwick S. Social support and resilience to stress: From neurobiology to clinical practice. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2007;4:35–40.. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen JS, Patten S. Well-being in residency training: A survey examining resident physician satisfaction both within and outside of residency training and mental health in Alberta. BMC Med Educ. 2005;5:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Earle L, Kelly L. Coping strategies, depression, and anxiety among Ontario family medicine residents. Can Fam Physician. 2005;51:242–243.. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tweed MJ, Bagg W, Child S, Wilkinson TJ, Weller JM. How the trainee intern (TI) year can ease the transition from undergraduate education to postgraduate practice. NZ Med J. 2010;123:81–91.. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bird A, Pincavage A. A curriculum to foster resident resilience. MedEdPORTAL. 2016;12:10439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Charmaz K. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide Through Qualitative Analysis. 2006London, UK: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kennedy TJ, Lingard LA. Making sense of grounded theory in medical education. Med Educ. 2006;40:101–108.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gaufberg E. Time to care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2008;27:845–849.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shanafelt TD. Enhancing meaning in work: A prescription for preventing physician burnout and promoting patient-centered care. JAMA. 2009;302:1338–1340.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shanafelt TD, Sloan JA, Habermann TM. The well-being of physicians. Am J Med. 2003;114:513–519.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Edwards S; members of the Future of Medical Education in Canada Postgraduate Project consortium Resident wellness and work/life balance in postgraduate medical education. https://www.afmc.ca/pdf/fmec/23_Edwards_Resident%20Wellness.pdf. Published 2011. Accessed February 28, 2017.

- 17.Slavin SJ, Chibnall JT. Finding the why, changing the how: Improving the mental health of medical students, residents, and physicians. Acad Med. 2016;91:1194–1196.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fralick M, Flegel K. Physician burnout: Who will protect us from ourselves? CMAJ. 2014;186:731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schaufeli WB, Bakker AB, van der Heijden FMMA, Prins JT. Workaholism, burnout and well-being among junior doctors: The mediating role of role conflict. Work Stress. 2009;23:155–172.. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Puddester D, Flynn L, Cohen J. CanMEDS Physician Health Guide: A Practical Handbook for Physician Health and Well-Being. 2009. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada; https://medicine.usask.ca/documents/pgme/CanMEDSPHG.pdf. Accessed February 28, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Skinner CA. Re-inventing medical work and training: A view from Generation X. Med J Aust. 2006;185:35–36.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Slavin SJ, Schindler DL, Chibnall JT. Medical student mental health 3.0: Improving student wellness through curricular changes. Acad Med. 2014;89:573–577.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hafferty FW, Franks R. The hidden curriculum, ethics teaching, and the structure of medical education. Acad Med. 1994;69:861–871.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martimianakis MA, Michalec B, Lam J, Cartmill C, Taylor JS, Hafferty FW. Humanism, the hidden curriculum, and educational reform: A scoping review and thematic analysis. Acad Med. 2015;90(11 suppl):S5–S13.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wald HS, Anthony D, Hutchinson TA, Liben S, Smilovitch M, Donato AA. Professional identity formation in medical education for humanistic, resilient physicians: Pedagogic strategies for bridging theory to practice. Acad Med. 2015;90:753–760.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]