SIGNIFICANCE

Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) disinfection systems are contact-lens-patient problem solvers. The current one-step, criterion-standard version has been widely used since the mid-1980s, without any significant improvement. This work identifies a potential next-generation, one-step H2O2, not based on the solution formulation but rather on a case-based peroxide catalyst.

PURPOSE

One-step H2O2 systems are widely used for contact lens disinfection. However, antimicrobial efficacy can be limited because of the rapid neutralization of the peroxide from the catalytic component of the systems. We studied whether the addition of an iron-containing catalyst bound to a nonfunctional propylene:polyacryonitrile fabric matrix could enhance the antimicrobial efficacy of these one-step H2O2 systems.

METHODS

Bausch + Lomb PeroxiClear and AOSept Plus (both based on 3% H2O2 with a platinum-neutralizing disc) were the test systems. These were tested with and without the presence of the catalyst fabric using Acanthamoeba cysts as the challenge organism. After 6 hours' disinfection, the number of viable cysts was determined. In other studies, the experiments were also conducted with biofilm formed by Stenotrophomonas maltophilia and Elizabethkingia meningoseptica bacteria.

RESULTS

Both control systems gave approximately 1-log10 kill of Acanthamoeba cysts compared with 3.0-log10 kill in the presence of the catalyst (P < .001). In the biofilm studies, no viable bacteria were recovered following disinfection in the presence of the catalyst compared with ≥3.0-log10 kill when it was omitted. In 30 rounds' recurrent usage, the experiments, in which the AOSept Plus system was subjected to 30 rounds of H2O2 neutralization with or without the presence of catalytic fabric, showed no loss in enhanced biocidal efficacy of the material. The catalytic fabric was also shown to not retard or increase the rate of H2O2 neutralization.

CONCLUSIONS

We have demonstrated the catalyst significantly increases the efficacy of one-step H2O2 disinfection systems using highly resistant Acanthamoeba cysts and bacterial biofilm. Incorporating the catalyst into the design of these one-step H2O2 disinfection systems could improve the antimicrobial efficacy and provide a greater margin of safety for contact lens users.

Acanthamoeba is a small free-living amoeba characterized by a life cycle of a feeding and dividing trophozoite stage, which, in response to adverse conditions, can transform into a highly resistant cyst stage.1,2 Acanthamoeba claims our attention not only as a fascinating organism about which there is much to be known but also because of its capacity to cause a potentially blinding infection of the cornea.3,4 Acanthamoeba keratitis is rare, but contact lens wearers account for 90% of cases, with numbers being reported with increasing frequency.5,6

Accordingly, safe contact lens use demands effective disinfection to help prevent keratitis from Acanthamoeba and other pathogenic organisms. Hydrogen peroxide 3% wt./vol. is used widely for this purpose, and disinfection is typically performed in a contact lens storage case containing a platinum-coated disc, which gradually catalyzes the decomposition of the hydrogen peroxide to oxygen and water (one-step peroxide disinfection systems).7 Failure to neutralize the hydrogen peroxide before wearing the contact lenses can result in a severe and painful reaction in the eye.8

The disadvantage of such one-step hydrogen peroxide systems is that neutralization can occur too rapidly and result in a failure to achieve adequate disinfection, particularly for resistant organisms such as fungi, bacterial spores, and Acanthamoeba cysts. Once neutralized, there is no residual disinfectant to give continued antimicrobial protection to the lenses during storage. Studies have shown that the efficacy of one-step peroxide disinfection systems can be enhanced significantly through the addition of a halide and peroxidase or acidified nitrite.9,10 However, these approaches may not be suitable as contact lens care systems.

US patent 8410011B211 describes novel methods for the preparation and use of metal-containing (covalently bound) fibrous catalysts, catalyst systems, and their uses in the treatment of waste (water). Furthermore, US patent 8513303B2 discloses these same catalysts and catalytic system types being used as antimicrobial agents, in the presence of hydrogen peroxide, for use in disinfection systems.12 The inventors disclose that the presence of these types of catalysts can significantly reduce the viability of Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus subtilis (spores and vegetative cells), and mycobacteria when compared with control hydrogen peroxide systems. Descriptions of the catalysts and its enhancement of the antimicrobial efficacy of hydrogen peroxide have also been published.13,14

Initial experiments found that one-step hydrogen peroxide disinfection systems rapidly killed bacteria and fungi, both with and without the catalyst. Therefore, showing any catalyst-attributable improvement to the one-step system was difficult using those species. Further experiments that demonstrated the addition of the catalyst into these commercial one-step hydrogen peroxide disinfection systems that could enhance the killing of Acanthamoeba prompted this report.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

According to US patents 8410011B2 and 8513303B2, creation of the iron-containing catalyst was carried out using a base material of 50:50 nonfunctional propylene:polyacryonitrile, with approximate density of 0.256 g/cm3 with the final catalytic iron content ranging from 0.92 to 1.71% wt./wt.11,12

Acanthamoeba castellanii (ATCC 50370) and Acanthamoeba polyphaga (ATCC 30461) were used in the study. Both strains were isolated from Acanthamoeba keratitis cases but differ in their genetic and morphological characteristics.15 Trophozoites were grown axenically (i.e., without any other life form) in Ac#6 medium, and cysts formed through starvation of trophozoites on nonnutrient agar, as described previously.15

PeroxiClear (3% hydrogen peroxide with a platinum-neutralizing disc; Bausch + Lomb, Rochester, NY) and AOSept Plus (3% hydrogen peroxide with a platinum-neutralizing disc; Alcon, Fort Worth, TX) were the test systems. In studies of peroxide neutralization rates, Oxysept 1 Step (3% hydrogen peroxide with catalase-neutralizing tablet; Abbott Medical Optics, Abbott Laboratories Inc., Abbott Park, IL) was included. One-fourth-strength Ringer's solution was used as a negative control (10 mL of solution added to the platinum disc–containing storage cases and challenged with Acanthamoeba trophozoites of cysts). The disinfectant neutralizer was 500 U/mL catalase in one-fourth-strength Ringer's solution.

Testing was performed as described previously, using a most probable number approach to quantify trophozoite or cyst viability after exposure to the disinfectant solutions for 2, 4, 6, and 24 hours at 25°C.15 All test and control experiments were conducted in the manufacturers' supplied contact lens storage cases using ten milliliters of the commercial hydrogen peroxide systems with or without 0.5 g of the catalyst. When testing with cysts, aliquots were removed at 1-, 2-, 4-, and 6-hour intervals, and the number of surviving organisms determined. With trophozoites, rapid killing occurred in the hydrogen peroxide systems, and the sample time points were reduced to 5, 10, 15, and 30 minutes. In latter experiments, varying weights of catalyst were tested in the AOSept Plus system with A. castellanii cysts as the challenge organism.

Studies were also undertaken to compare the efficacy of a commercial one-step hydrogen peroxide contact lens care system, with and without the presence of the catalyst-enhancing material, against gram-negative bacteria grown as biofilm. The bacteria used were Stenotrophomonas maltophilia (ALC-01) and Elizabethkingia meningoseptica (3AS) isolated in high numbers from the contact lens storage cases of patients with corneal infiltrative events.16 The bacteria were grown in six-well microtiter plates using 0.01% trypticase soya broth overnight at 32°C. The wells were then washed three times with Dulbecco phosphate-buffered saline to leave only the biofilm and then exposed either to the AOSept Plus system alone or with the addition of 0.5 g of catalyst material, AOSept Plus (3% hydrogen peroxide) without neutralizing disc, Dulbecco phosphate-buffered saline + 0.5 g of catalyst material, or Dulbecco phosphate-buffered saline alone (control). After 4 hours' incubation at 25°C, the wells were sonicated (50% amplitude for 3 × 3 seconds) to disrupt the biofilm, and 100-μL volumes were spread over trypticase soy agar plates for incubation at 32°C overnight. Aliquots were also diluted 1:10 into peroxide neutralizer comprising 500 U/mL catalase in one-fourth-strength Ringer's solution and cultured on to trypticase soy agar plates, as described previously.

Experiments were also conducted to establish whether the catalyst affected the rate of hydrogen peroxide decomposition in the systems. Here, 0.5 g of catalyst was added to the commercial systems containing hydrogen peroxide, and the rate of neutralization was measured by loss in weight using an analytical balance sensitive to four decimal places (Sartorius, Surrey, United Kingdom). The observed weight loss is due to the evolution of oxygen gas while the hydrogen peroxide is being neutralized by the platinum element.

The AOSept Plus system was subjected to 30 rounds of hydrogen peroxide neutralization with or without the presence of 0.5 g of catalyst material. Both systems were then challenged with A. castellanii cysts, and the rate of kill was determined after 4 hours. Statistical analysis of the differences in solution biocidal efficacy was performed using one-way analysis of variance from experimental mean values and SD, with Tukey posttest using GraphPad InStat version 3.06 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

RESULTS

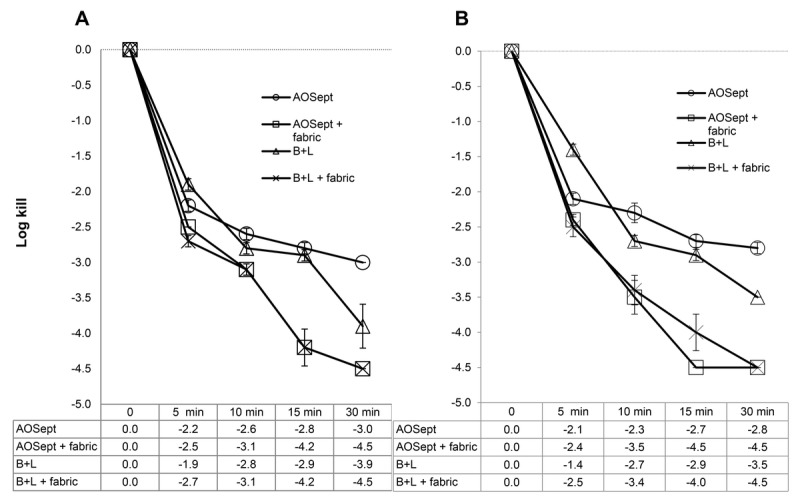

For the trophozoites of A. castellanii (50370), the AOSept Plus system gave a 3.0-log10 kill after 30 minutes' exposure compared with 4.5-log10 kill in the presence of the catalyst material (P < .001; Fig. 1A). Similarly, the Bausch + Lomb system showed a 3.9-log10 kill after 30 minutes compared with 4.5-log10 kill when the catalyst was present (P < .001; Fig. 1A). For the trophozoites of A. polyphaga (30461), the AOSept Plus system gave a 2.8-log10 kill after 30 minutes' exposure compared with 4.5-log10 kill in the presence of the catalyst material (P < .001; Fig. 1B). Similarly, the Bausch + Lomb system showed a 3.5-log10 kill after 30 minutes compared with 4.5-log10 kill when the catalyst was included (P < .001; Fig. 1B).

FIGURE 1.

Killing efficacy of commercial peroxide systems against trophozoites of A. castellanii (ATCC 50370) (A) and A. polyphaga (ATCC 30461) (B). Fabric refers to the iron-containing fabric catalyst. Each data point represents the mean ± SD of three individual tests. In each case, the catalyst enhances reduction of the trophozoites ≥ 2 logs over the controls.

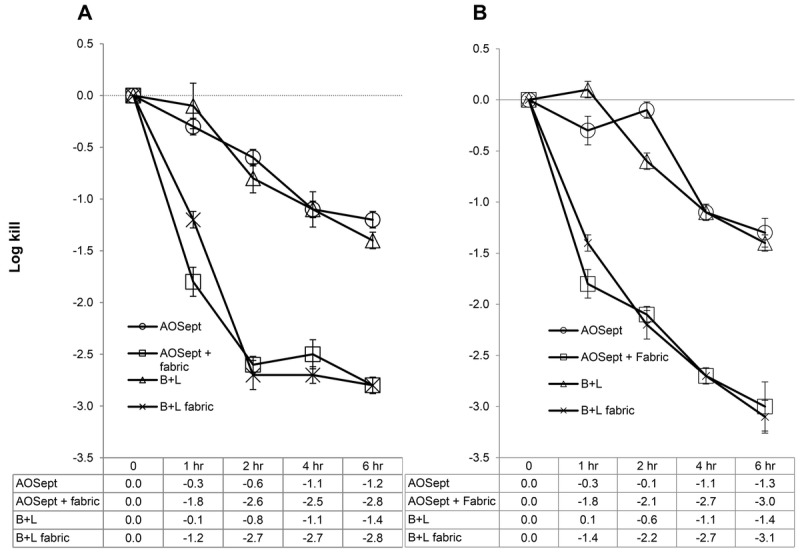

For the cysts of A. castellanii (50370), the AOSept Plus system gave a 1.2-log10 kill after 6 hours' exposure compared with 2.8-log10 kill in the presence of the catalyst (P < .001; Fig. 2A). Similarly, the Bausch + Lomb system showed a 1.4-log10 kill after 6 hours compared with 2.8-log10 kill when the catalyst was included (P < .001; Fig. 2A). For the cysts of A. polyphaga (30461), the AOSept Plus system gave a 1.3-log10 kill after 6 hours' exposure compared with 3.0-log10 kill in the presence of the catalyst (P < .001; Fig. 2B). Similarly, the Bausch + Lomb system showed a 1.4-log10 kill after 6 hours compared with 3.1 log10 kill when the catalyst was included (P < .001; Fig. 2B).

FIGURE 2.

Killing efficacy of commercial peroxide systems against cysts of A. castellanii (ATCC 50370) (A) and A. polyphaga (ATCC 30461) (B). Fabric refers to the iron-containing fabric catalyst. Each data point represents the mean ± SD of three individual tests. In each case, the catalyst enhances reduction of the cysts ≥ 2 logs over the controls.

Incubation of trophozoites or cysts of the Acanthamoeba strains in one-fourth-strength Ringer's solution and 0.5 g of the catalyst for 6 hours showed no significant reduction in viability ( ≤ 0.5-log10 reduction, results not shown).

The efficacy of the test solutions, with various weights of catalyst against the cysts of A. castellanii (50370), after 2 and 4 hours' exposure was addressed. The AOSept system alone gave a 1.3- to 1.6-log10 kill after 2 to 4 hours' exposure. In the presence of the catalyst, a steady increase in cyst kill was observed with 0.1 to 0.4 g of material, giving a 1.8- to 2.2-log10 kill at 2 hours and 2.1- to 3.1-log10 kill by 4 hours. Maximum increased kill occurred with 0.5 g of material with 2.9- and 3.5-log10 kill at 2 and 4 hours, respectively. No additional kill was observed when 0.6 and 0.7 g of catalytic material were tested (results not shown).

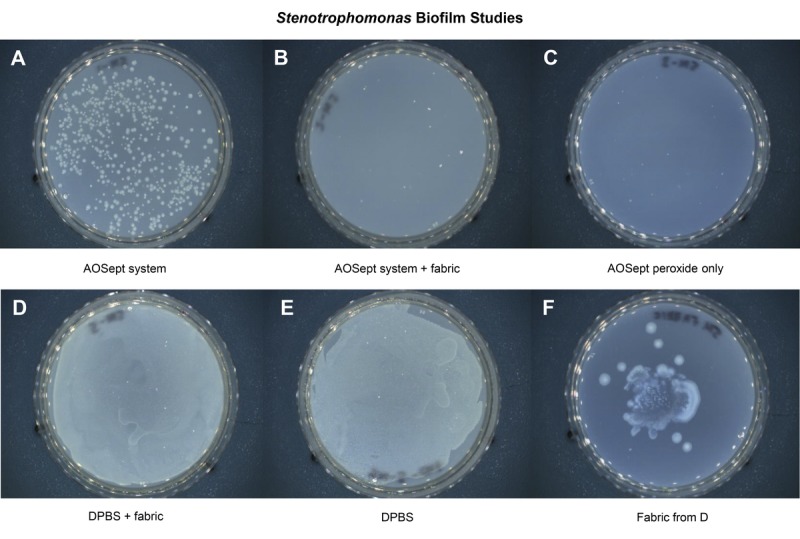

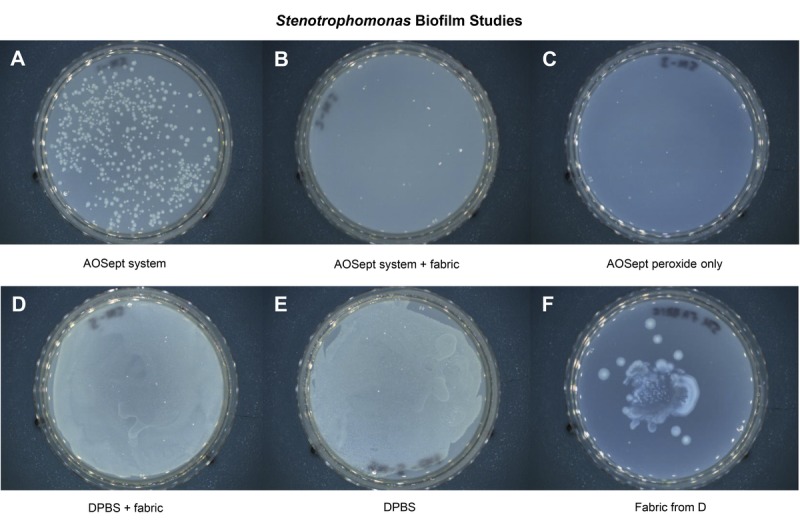

The efficacy of the test systems in inactivating biofilm formed by S. maltophilia and E. meningoseptica is shown in Figs. 3 and 4, which are photographic images of the trypticase soy agar culture plates from the experiments. Previous studies have shown that biofilm formed by S. maltophilia or and E. meningoseptica contains approximately 1 × 107 colony-forming units (unpublished observation from S. Kilvington).

FIGURE 3.

Photographic images of the trypticase soy agar culture plates showing the efficacy of test systems against S. maltophilia biofilm formation. After neutralization control (A), after neutralization with catalyst (B), AOSept solution (C), catalyst with Dulbecco phosphate-buffered saline (D), Dulbecco phosphate-buffered saline control (E), and catalyst fabric from experiment D (F). The fabric catalyst resists biofilm formation and eliminates it in the test systems.

FIGURE 4.

Photographic images of the trypticase soy agar culture plates showing the efficacy of test systems against Elizabethkingia biofilm formation. After neutralization control (A), after neutralization with catalyst (B), AOSept solution (C), catalyst with Dulbecco phosphate-buffered saline (D), Dulbecco phosphate-buffered saline control (E), and catalyst fabric from experiment D (F). The fabric catalyst resists biofilm formation and eliminates it in the test systems.

For S. maltophilia and the AOSept Plus system (Fig. 3), numerous bacteria were recovered after disinfection (Fig. 3A), equivalent to 2000 colony-forming units/mL. No bacteria were recovered with the AOSept Plus system + 0.5 g catalyst fabric (Fig. 3B) or when the AOSept Plus hydrogen peroxide alone was used (Fig. 3C). For the catalyst fabric in Dulbecco phosphate-buffered saline (Fig. 3D), confluent growth of bacteria was observed but was less dense than that observed with the Dulbecco phosphate-buffered saline alone (Fig. 3E). The catalyst fabric from experiment D was also cultured and showed heavy growth on the plate (Fig. 3F).

For E. meningoseptica (Fig. 4), no viable bacteria were recovered from either the AOSept Plus system (Fig. 4A), the AOSept Plus system + 0.5 g catalytic fabric (Fig. 4B), or the AOSept Plus hydrogen peroxide alone (Fig. 4C). For the fabric in Dulbecco phosphate-buffered saline (Fig. 4D), significantly less viable bacteria were recovered compared with that observed from the Dulbecco phosphate-buffered saline alone (Fig. 4E). The catalytic fabric from experiment D was also cultured and showed heavy growth on the plate (Fig. 4F).

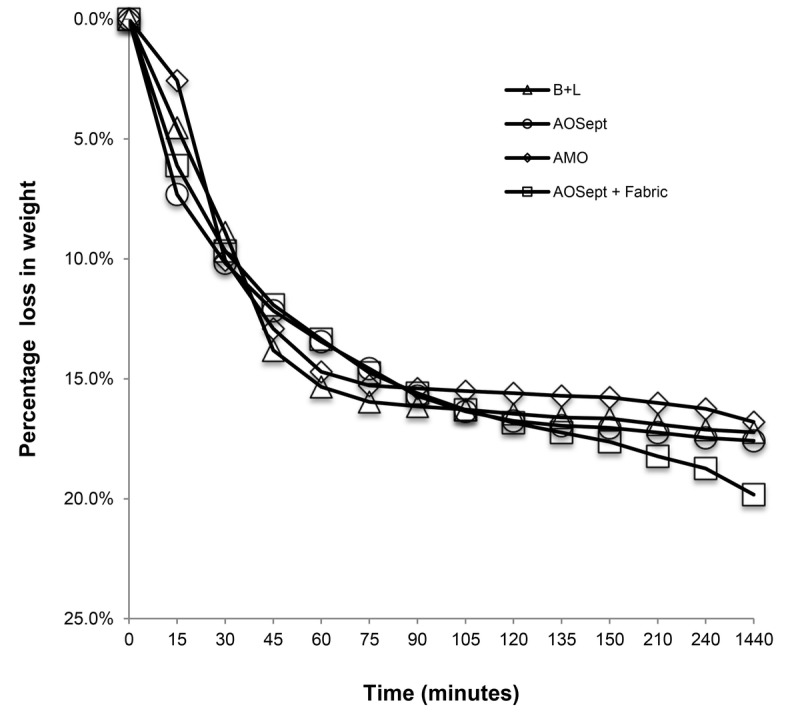

The percent loss in weight of the hydrogen peroxide systems is shown in Fig. 5, as this is a measure of the rate of hydrogen peroxide decomposition in the cases as the oxygen is released. Oxysept (Abbott Medical Optics) was also included in these studies. It is a 3% hydrogen peroxide–based system but uses a separate catalase-neutralizing tablet to be added for disinfection use. This demonstrates that the catalyst does not affect the rate of hydrogen peroxide decomposition in the platinum disc or catalase tablet–based systems.

FIGURE 5.

Rate of hydrogen peroxide decomposition of three different commercial contact lens hydrogen peroxide care systems compared to that of AOSept with the fabric catalyst. No significant differences appear. Revealing that the fabric catalyst does not enhance nor delay the neutralization of the hydrogen peroxide systems, but only enhances the biocidal effect of the hydrogen peroxide.

In the experiments in which the AOSept Plus system was subjected to 30 rounds of hydrogen peroxide neutralization with or without the presence of 0.5 g of catalytic fabric, both systems were then challenged with A. castellanii cysts, and the rate of kill was determined after 6 hours. The AOSept Plus system without the catalytic fabric gave a 1.2-log10 kill of cysts by 6 hours. In the presence of the catalytic fabric, a 2.7-log10 kill was achieved, indicating the material did not lose efficacy after at least 30 repeated cycles.

DISCUSSION

As has been reported previously, the antimicrobial activity of hydrogen peroxide can be enhanced by the presence of a heterogeneous modified polyacrylonitrile catalyst impregnated with ferric chloride or ferric sulphate.13,14 This is based on the observation that transition metal salts can activate hydrogen peroxide to form hydroxyl radicals (OH·), which are powerful antioxidants and as such capable of causing rapid microbial death.17,18 As the hydroxyl radical has a very short in vivo half-life of approximately 10−9 seconds, there will be negligible, if any, remaining radicals after the hydrogen peroxide has been neutralized by the platinum element, thus posing no risk to mammalian cells. Hydrogen peroxide (3% wt./vol.) is widely used as a contact lens disinfectant but must be neutralized prior to insertion of the lenses to avoid severe and potentially injurious damage to the eye.8,19 Therefore, neutralization is achieved through the presence of a platinum disc in the lens storage case or the addition of a catalase tablet.7 Although such systems show good activity to most corneal pathogens, the rapid neutralization of the hydrogen peroxide significantly reduces their efficacy against resistant organisms and their life forms such as Acanthamoeba cysts.7,20 Previous studies have shown that hydrogen peroxide antimicrobial efficacy, including Acanthamoeba cysts, can be significantly enhanced through the generation of free radicals from the addition of a halide (KI) and the use of plant catalase for neutralization or by using acidified nitrite.9,10 However, such modifications are not easily combined into conventional one-step, hydrogen peroxide–based contact lens disinfection systems.

For this reason, we developed an assay method using Acanthamoeba cysts that reliably and reproducibly demonstrated that commercial one-step, hydrogen peroxide–based contact lens disinfectant systems (using a platinum-neutralizing disc), in the presence of the novel catalyst, resulted in significance enhancement of cytocidal efficacy. Furthermore, the novel catalyst enhanced the efficacy of the one-step system to kill bacteria under biofilm conditions. Biofilm is an important consideration in contact lens care as bacteria under such conditions are significantly more resistant to disinfection.21,22 Furthermore, the authors' own unpublished observation that biofilm-formed bacteria provide a suitable source of food for Acanthamoeba and also increase adherence of the organism to contact lenses is corroborated elsewhere.23

In conclusion, we have shown that the catalyst significantly increases the efficacy against highly resistant Acanthamoeba cysts and bacterial biofilm. It is estimated that there are 140 million contact lens wearers worldwide, and their use represents a risk factor for microbial keratitis of approximately 40 cases per 100,000 users and other adverse events.24–27 This is particularly evident in Acanthamoeba keratitis, in which contact lens wearers account for 90% of reported cases and can lead to severe and painful permanent blindness.28–32 It is hoped that the findings of this study can be developed to include the catalyst into the design of one-step hydrogen peroxide contact lens disinfection systems and in so doing improve overall antimicrobial efficacy and thus provide a greater margin of safety for contact lens users.

Footnotes

Funding/Support: None of the authors have reported funding/support.

Conflict of Interest Disclosure: The catalytic technology shown herein is owned by DeMontfort University and was studied independent of any financial interest. Following the completion of this study, Better Vision Solutions (Lynn Winterton) has since optioned the technology from DeMontfort University.

Author Contributions: Methodology and Resources: SK; Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Funding Acquisition, Investigation, and Writing — Original Draft: LW; Project Administration, Supervision, and Writing — Review & Editing: SK, LW.

REFERENCES

- 1. Marciano-Cabral F, Cabral G. Acanthamoeba spp. as Agents of Disease in Humans. Clin Microbiol Rev 2003;16:273–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kilvington S, White DG. Acanthamoeba: Biology, Ecology and Human Disease. Rev Med Microbiol 1994;5:12–20. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Radford CF, Bacon AS, Dart JK, et al. Risk Factors for Acanthamoeba Keratitis in Contact Lens Users: A Case-Control Study. BMJ 1995;310:1567–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Radford CF, Minassian DC, Dart JK. Acanthamoeba Keratitis in England and Wales: Incidence, Outcome, and Risk Factors. Br J Ophthalmol 2002;86:536–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Verani JR, Lorick SA, Yoder JS, et al. National Outbreak of Acanthamoeba Keratitis Associated with Use of a Contact Lens Solution, United States. Emerg Infect Dis 2009;15:1236–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jasim H, Knox-Cartwright N, Cook S, et al. Increase in Acanthamoeba Keratitis May Be Associated with Use of Multipurpose Contact Lens Solution. BMJ 2012;344:e1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hughes R, Kilvington S. Comparison of Hydrogen Peroxide Contact Lens Disinfection Systems and Solutions Against Acanthamoeba polyphaga . Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2001;45:2038–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Holden B. A Report Card on Hydrogen Peroxide for Contact Lens Disinfection. CLAO J 1990;16:S61–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hughes R, Andrew PW, Kilvington S. Enhanced Killing of Acanthamoeba Cysts with a Plant Peroxidase–Hydrogen Peroxide–Halide Antimicrobial System. Appl Environ Microbiol 2003;69:2563–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Heaselgrave W, Andrew PW, Kilvington S. Acidified Nitrite Enhances Hydrogen Peroxide Disinfection of Acanthamoeba, Bacteria and Fungi. J Antimicrob Chemother 2010;65:1207–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Huddersman K, Ischtchenko V. Fibrous Catalyst, Its Preparation and Use Thereof. Patent # US8410011 B2, published April 2, 2013.

- 12. Huddersman K, Walsh SE. Antimicrobial Agent. Patent #US8513303 B2, published August 20, 2013.

- 13. Boateng MK, Price SL, Huddersman KD, et al. Antimicrobial Activities of Hydrogen Peroxide and Its Activation by a Novel Heterogeneous Fenton's-Like Modified PAN Catalyst. J Appl Microbiol 2011;111:1533–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Price SL, Huddersman KD, Shen J, et al. Mycobactericidal Activity of Hydrogen Peroxide Activated by a Novel Heterogeneous Fentons-Like Catalyst System. Lett Appl Microbiol 2013;56:83–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kilvington S, Lam A. Development of Standardised Methods for Assessing Biocidal Efficacy of Contact Lens Care Solutions Against Acanthamoeba Trophozoites and Cysts. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2013;54:4527–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kilvington S, Shovlin J, Nikolic M. Identification and Susceptibility to Multipurpose Disinfectant Solutions of Bacteria Isolated from Contact Lens Storage Cases of Patients with Corneal Infiltrative Events. Cont Lens Anterior Eye 2013;36:294–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Neyens E, Baeyens J. A Review of Classic Fenton's Peroxidation as an Advanced Oxidation Technique. J Hazard Mater 2003;98:33–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Russell AD. Similarities and Differences in the Responses of Microorganisms to Biocides. J Antimicrob Chemother 2003;52:750–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tripathi BJ, Tripathi RC, Millard CB, et al. Cytotoxicity of Hydrogen Peroxide to Human Corneal Epithelium In Vitro and Its Clinical Implications. Lens Eye Toxic Res 1990;7:385–401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kilvington S. Antimicrobial Efficacy of a Povidone Iodine (PI) and a One-step Hydrogen Peroxide Contact Lens Disinfection System. Contact Lens Anterior Eye 2004;27:209–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Donlan RM, Costerton JW. Biofilms: Survival Mechanisms of Clinically Relevant Microorganisms. Clin Microbiol Rev 2002;15:167–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lynch AS, Robertson GT. Bacterial and Fungal Biofilm Infections. Annu Rev Med 2008;59:415–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kahn NA. Acanthamoeba: Biology and Pathogenesis. Norfolk, UK: Caister Academic Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dart JK, Radford CF, Minassian D, et al. Risk Factors for Microbial Keratitis with Contemporary Contact Lenses: A Case-Control Study. Ophthalmology 2008;115:1647–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Keay L, Edwards K, Naduvilath T, et al. Factors Affecting the Morbidity of Contact Lens–Related Microbial Keratitis: A Population Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2006;47:4302–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Stapleton F, Carnt N. Contact Lens–Related Microbial Keratitis: How Have Epidemiology and Genetics Helped Us with Pathogenesis and Prophylaxis. Eye (Lond) 2012;26:185–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Stapleton F, Keay L, Jalbert I, et al. The Epidemiology of Contact Lens Related Infiltrates. Optom Vis Sci 2007;84:257–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Joslin CE, Tu EY, Shoff ME, et al. The Association of Contact Lens Solution Use and Acanthamoeba Keratitis. Am J Ophthalmol 2007;144:169–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kilvington S, Gray T, Dart J, et al. Acanthamoeba Keratitis: The Role of Domestic Tap Water Contamination in the United Kingdom. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2004;45:165–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dart JK, Saw VP, Kilvington S. Acanthamoeba Keratitis: Diagnosis and Treatment Update 2009. Am J Ophthalmol 2009;148:487–99, e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Radford CF, Bacon AS, Dart JK, et al. Risk Factors for Acanthamoeba Keratitis in Contact Lens Users: A Case Control Study. BMJ 1995;10:1567–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Radford CF, Lehmann OJ, Dart JK. Acanthamoeba Keratitis: Multicentre Survey in England 1992–6. National Acanthamoeba Keratitis Study Group. Br J Ophthalmol 1998;82:1387–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]