Abstract

Background

Intracellular pH (pHi) is critical to cardiac excitation and contraction; uncompensated changes in pHi impair cardiac function and trigger arrhythmia. Several ion transporters participate in cardiac pHi regulation. Our previous studies identified several isoforms of a solute carrier Slc26a6 to be highly expressed in cardiomyocytes. We show that Slc26a6 mediates electrogenic Cl−/HCO3− exchange activities in cardiomyocytes, suggesting the potential role of Slc26a6 in regulation of not only pHi, but also cardiac excitability.

Methods and Results

To test the mechanistic role of Slc26a6 in the heart, we took advantage of Slc26a6 knockout (Slc26a6−/−) mice using both in vivo and in vitro analyses. Consistent with our prediction of its electrogenic activities, ablation of Slc26a6 results in action potential (AP) shortening. There are reduced Ca2+ transient and sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ load, together with decreased sarcomere shortening in Slc26a6−/− cardiomyocytes. These abnormalities translate into reduced fractional shortening and cardiac contractility at the in vivo level. Additionally, pHi is elevated in Slc26a6−/− cardiomyocytes with slower recovery kinetics from intracellular alkalization, consistent with the Cl−/HCO3− exchange activities of Slc26a6. Moreover, Slc26a6−/− mice show evidence of sinus bradycardia and fragmented QRS complex, supporting the critical role of Slc26a6 in cardiac conduction system.

Conclusions

Our study provides mechanistic insights into Slc26a6, a unique cardiac electrogenic Cl−/HCO3− transporter in ventricular myocytes, linking the critical roles of Slc26a6 in regulation of pHi, excitability, and contractility. pHi is a critical regulator of other membrane and contractile proteins. Future studies are needed to investigate possible changes in these proteins in Slc26a6−/− mice.

Keywords: Solute carrier, Slc26a6, action potential, cardiac function

Journal Subject Terms: Ion channels/Membrane Transport, Electrophysiology, Arrhythmias, Basic Science Research, Contractile Function, Hemodynamics, Ischemia, Physiology

Introduction

Acid-base balance is critical for maintaining normal cardiac function. An uncompensated shift of intracellular pH (pHi) generates abnormal electrical activities, contractile disorder, and altered intracellular Ca2+ signaling.1, 2 The bicarbonate (HCO3−) / carbon dioxide (CO2) buffering system plays a central role in regulation of pHi. Therefore, transport of HCO3− across the plasma membrane is critical in maintaining cellular pH homeostasis. Several HCO3− transporters have been identified in cardiomyocytes, including Na+/HCO3− (NBC) co-transporter and Cl−/HCO3− exchanger (AE or CBE).1 NBC mediates acid extrusion, while AE mediates acid loading.

Solute carrier Slc26a6 is a versatile anion exchanger, first identified in epithelial cells, with abundant expression in kidneys, pancreas, intestines, and placenta.3–5 It mediates Cl−/oxalate, Cl−/HCO3−, Cl−/OH−, Cl−/SO42−, and Cl−/formate exchange activities. It was previously reported that Slc26a6 is the predominant Cl−/HCO3− and Cl−/OH− exchanger in the mouse heart, based on the transcript levels.6 Our recent functional study identified four cardiac Slc26a6 isoforms, which mediate Cl−/HCO3− exchange in atrial and ventricular myocytes7. Importantly, we found that Cl−/HCO3− exchange by cardiac Slc26a6 is electrogenic. Indeed, cardiac Slc26a6 represents the first electrogenic exchanger with only anionic substrates and provides active transport of Cl− into the cells to regulate intracellular Cl− homeostasis. In addition, activities of Slc26a6 are predicted to alter the pHi by transporting HCO3− or OH−. Therefore, we hypothesize that cardiac Slc26a6 may play a unique role in the regulation of not only pHi, but also cardiac excitability and function.

To directly test the hypothesis, we took advantage of a Slc26a6 knockout (Slc26a6−/−) mouse model8 using in vivo and in vitro analyses. Under physiological conditions, Slc26a6 activities are predicted to coincide with the dynamic range of cardiac action potential (AP), generating mainly inward currents, with outward current beyond ~ +36 mV7. Indeed, our study reveals that ablation of Slc26a6 results in AP shortening, consistent with electrogenic activities of Slc26a6. The shortened AP durations (APDs) result in reduced Ca2+ transient and sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) Ca2+ load, along with decreased sarcomere shortening in Slc26a6−/− cardiomyocytes. These abnormalities translate into reduced fractional shortening and cardiac contractility at the in vivo level. Importantly, pHi is elevated in Slc26a6−/− cardiomyocytes with slower recovery kinetics from intracellular alkalization, consistent with Cl−/HCO3− exchange activities of Slc26a6. Moreover, Slc26a6−/− mice show evidence of sinus bradycardia and fragmented QRS complex, supporting the critical role of Slc26a6 in cardiac conduction system.

Materials and Methods

All animal care and procedures were performed in accordance with the protocols approved by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of California, Davis and in accordance with National Institutes of Health guidelines. De-identified human ventricular specimens were obtained from a commercial source, in accordance with the approved UC Davis Institutional Review Board (IRB) protocol. Please refer to the Online Supplemental Data for additional details.

We used 129S6/SvEv wild type (WT) and Slc26a6−/− mice previously generated and reported8 (a generous gift from Dr. Peter S. Aronson, Yale University) in our study. All experiments described in the study were conducted in a blinded fashion.

Cardiac tissue preparation and cardiomyocyte isolation

Mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of 80 mg/kg of ketamine and 5 mg/kg of xylazine. Cardiomyocytes were isolated as previously described7

Genotyping, western blot, and histological analyses

Histological and western blot analyses of cardiac tissue were performed as we have previously described9. Genotyping analyses of Slc26a6−/− mice are presented in Supplemental Figure 1.

Electrocardiographic Recordings

ECG recordings were performed as previously described10, 11.

Analysis of cardiac function by echocardiography

Echocardiograms to assess systolic function were performed in conscious animals as we have previously described.10

Hemodynamic monitoring

Mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of 80 mg/kg of ketamine and 5 mg/kg of xylazine and maintained at 37 ºC. Recording of pressure and volume was performed by using Millar Pressure-Volume System MPVS-300 (Millar, Inc., Houston, TX), Power Lab, and Lab Chart 6.0 software (AD Instruments, Colorado Springs, CO).

Patch-clamp recordings

Whole-cell current7 and AP recordings10 were performed as we have previously described. For current recordings, the clamped and suspended whole-cell was alternately exposed to two capillary tubes dispensing control and test solutions at a potential of 0 mV.7 For the outward current recording, we used the same solutions as we previously documented7.

For the inward current recording, the pipette solution contained (in mM): 24 NaHCO3, 116 Na Glutamate, 1 EGTA, 1.4 NaCl, and gassed with 5% CO2 and 95% O2. The bath control solution was the same as pipette solution. The bath test solution with 140 mM Cl− contained (in mM): 140 NaCl, 10 HEPEs, 1 EGTA, and pH 7.4; the bath test solution with 14 mM Cl− contained (in mM): 14 NaCl, 126 Na Glutamate, 10 HEPEs, 1 EGTA, and pH 7.4. Current recordings were performed at the room temperature and APs were recorded at 36 °C.

Measurement of sarcomere shortening and Ca2+ transient (CaT)

We used IonOptix sarcomere detection (IonOptix LLC., Westwood, MA) and the fast Fourier transform (FFT) method12. Contraction was measured using a high-speed camera (MyoCam-S, 240 to 1000 frames/s) to record sarcomere movement. The sarcomere pattern was used to calculate the sarcomere length using an FFT algorithm. The fractional shortening was calculated as the percentage change in sarcomere length during contraction. Simultaneous Ca2+ transients (CaT) were recorded using Fura-2 dual-wavelength ratiometric method12, which is more precise than the Fluo-4 single-wavelength method.

The recording solution contained (in mM): 145 NaCl, 4 KCl, 1 CaCl2, 0.33 NaH2PO4, 1 MgCl2, 10 Glucose, 10 HEPES, with pH 7.4. In a separate set of experiments, HCO3− was used as a buffer, and the recording solution contained (in mM): 120 NaCl, 4 KCl, 1 CaCl2, 0.33 NaH2PO4, 1 MgCl2, 10 Glucose, 24 NaHCO3, gassed by 5% CO2 and 95% O2. To reduce the pHi, but keep pHo constant, sodium acetate was applied to clamp the pHi13, 14. Sodium acetate was used to replace an equal concentration of NaCl, and 5 μM 5-(N-Ethyl-N-isopropyl) amiloride (EIPA) was added to inhibit the Na+/H+ exchanger for acetate application.

Intracellular pH (pHi) measurement

The pHi of cardiomyocytes was measured using carboxy-SNARF-1 fluorescent pH indicator. Isolated cardiomyocytes were loaded with 10 μM SNARF-1 AM in Tyrode’s solution. The measurement was performed using Na+-free solutions, buffered by either HEPES or HCO3−. HEPES-buffered solution contained (in mM): 144 NMG-Cl, 4 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 10 Glucose, 10 HEPES, and pH 7.4. HCO3−-buffered solution contained (in mM): 120 NMG-Cl, 4 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 10 Glucose, 24 Choline-HCO3, gassed by 5% CO2 and 95% O2. Sodium acetate was used to clamp pHi, and 5 μM 5-(N-Ethyl-N-isopropyl) amiloride (EIPA) was added to inhibit the Na+/H+ exchanger for acetate application.

The SNARF emission ratio (F580/F640) was converted to pHi using standard calibration15–17. SNARF emission ratios were measured while cells were perfused by calibration solutions with five different pH values. The calibration solutions contained (in mM): 140 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 20 HEPES (or MES at pH 5.5), with pH 5.5, 6.5, 7.0, 7.5, and 8.0. Negericin (10 μM, a K+/H+ antiporter ionophore) was added to the calibration solution before use.

Molecular cloning from human cardiac tissues

De-identified human ventricular specimens were obtained from a commercial source (T Cubed), in accordance with the approved UC Davis Institutional Review Board (IRB) protocol. Total RNA and mRNA were extracted, and similar cloning strategy was used as previously described7.

Heterologous expression in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells

Human cardiac SLC26A6 isoforms were expressed in CHO cells following the protocol we used previously7.

Statistical analyses

Data are presented as mean ± S.E.M. Statistical comparisons were analyzed by student’s t-test. Statistical significance was considered to be achieved when p<0.05.

Results

Ablation of Slc26a6−/− results in cardiac AP shortening

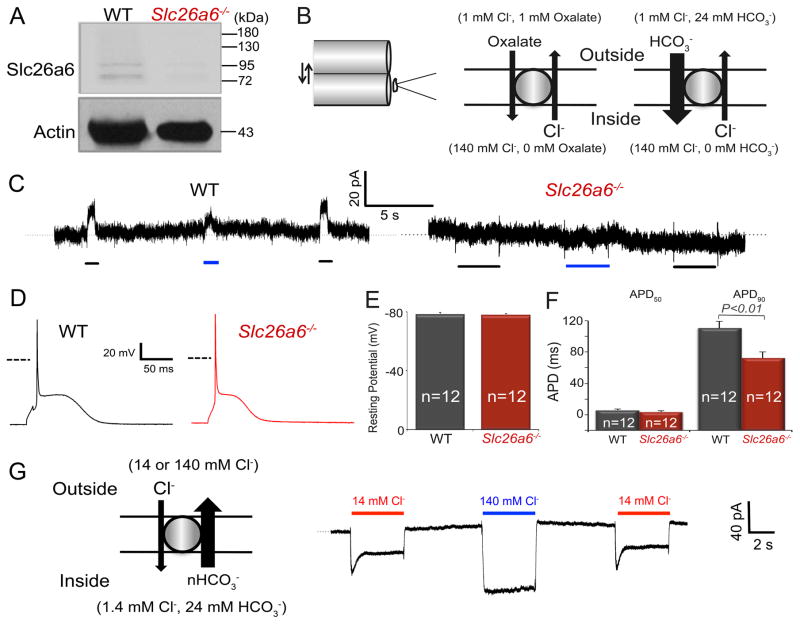

To test the functional roles of Slc26a6, we took advantage of an Slc26a6−/− mouse model.8 We first confirmed the lack of Slc26a6 expression in ventricular myocytes isolated from Slc26a6−/− mice (Fig. 1A), and the two bands in WT lane suggest different mouse cardiac slc26a6 isoforms we reported before7. To test the role of Slc26a6 in Cl−/HCO3− and Cl−/oxalate exchange, we recorded outward currents using fast solution exchange and suspended whole-cell recording methods, as we have previously described.7 Fig. 1B&C show the solution exchange configuration and corresponding currents, respectively, recorded from WT and Slc26a6−/− ventricular myocytes. The outward Cl−/HCO3− and Cl−/oxalate exchange currents were completely abolished in Slc26a6−/− ventricular myocytes (Fig. 1C, right).

Figure 1. Ablation of Slc26a6−/− results in cardiac AP shortening.

A. Western blot analysis confirms the absence of Slc26a6 expression in Slc26a6−/− mouse hearts. B. Schematic diagram of the fast solution exchange of the suspended whole-cell recording (left), and the ionic configuration to activate outward exchange current through Slc26a6. For recordings of the outward Slc26a6 currents, cardiomyocytes were first clamped at 0 mV, suspended, and moved to the outlet of the solution exchange capillary tube dispensing the bath control solution. Then the myocyte was switched to the capillary tube dispensing bath test solution, containing oxalate or HCO3−, for the activation of outward currents. The fast solution switch was performed by SF-77 solution exchanger controlled by pClamp10 software. The compositions of the bath control and test solutions have been described in Methods. C. Representative recording traces of outward currents recorded from WT ventricular myocytes (left) and Slc26a6−/− ventricular myocytes (right). The black and blue bars under the current traces represent the solution exchange to bath test solutions to activate Cl−/Oxalate and Cl−/HCO3− exchange currents, respectively. D. Representative traces of action potentials (APs) from WT and Slc26a6−/− ventricular myocytes. Dashed lines represent 0 mV. E. Comparisons of resting membrane potentials (RMPs). F. Summary data of the action potential durations at 50% (APD50) and 90% repolarization (APD90). The AP and RMP were recorded in HCO3− buffered bath solution. G. Inward Cl−/HCO3− exchange current elicited from WT ventricular myocytes using fast solution exchange, as indicated in the diagram on the left. The red and blue bars above the current traces represent the solution exchange to bath test solutions containing 14 or 140 mM Cl− to activate Cl−/HCO3− exchange currents, respectively.

Since cardiac Slc26a6 is an electrogenic Cl−/HCO3− exchanger, we predict that activities of Slc26a6 will affect cardiac APDs. There were no significant differences in the resting membrane potentials (RMPs), however, APD at 90% repolarization (APD90) was significantly shorter in Slc26a6−/− ventricular myocytes compared to WT (Fig. 1D, E and F). It has previously been reported that the stoichiometry of cardiac Slc26a6 for HCO3−:Cl− is 2 or greater, therefore, the estimated reversal potential of the exchange is ~+36 mV under physiological condition. Our findings are consistent with the prediction that Slc26a6 generates inward currents by electrogenic Cl−/HCO3− exchange through most of the AP, due to the positive reversal potential for Cl−/HCO3− exchange under physiological condition in cardiomyocytes.7 Indeed, a prominent inward current can be generated in cardiomyocytes via Cl−/HCO3− exchange with 24 mM HCO3− inside the cells (Fig. 1G).

The APD shortening may also be caused by the remodeling of other major ion channels such as Ca2+ and K+ channels due to the knockout of Slc26a6. We therefore recorded the Ca2+ and total K+ currents from WT and Slc26a6−/− ventricular myocytes. As shown in supplemental Figure 2, we did not find significant differences in the current density between WT and Slc26a6−/− myocytes.

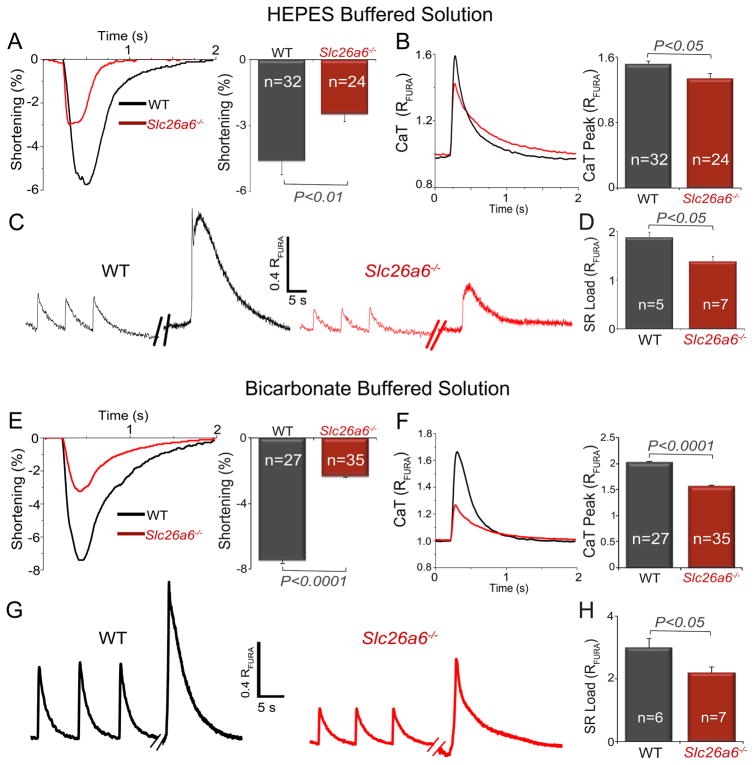

Slc26a6−/− cardiomyocytes show reduced sarcomere shortening, Ca2+ transient, and SR Ca2+ load

The shortening of cardiac APs in Slc26a6−/− is predicted to result in decreased Ca2+ entry and possible impairment of cardiomyocyte contractility. We, therefore, tested the Ca2+ transient (CaT), sarcomere shortening, and SR Ca2+ load in WT and Slc26a6−/− ventricular myocytes using HEPES (Cl−/OH− exchange, Fig 2A–D) or HCO3− (Cl−/HCO3− exchange, Fig. 2E–H) buffered solutions. Compared to WT cardiomyocytes, Slc26a6−/− cardiomyocytes demonstrated significantly reduced fractional shortening and CaT amplitude (Fig. 2A&B). To test whether the decrease in CaT was due to reduced SR Ca2+ content, we measured the SR Ca2+ content in WT and Slc26a6−/− cardiomyocytes (Fig. 2C&D). Indeed, the SR Ca2+ load was significantly reduced in Slc26a6−/− cardiomyocytes. Similar findings are shown for HCO3− buffered solution (Fig. 2E–H).

Figure 2. Slc26a6−/− cardiomyocytes show reduced sarcomere shortening, Ca2+ transient, and SR Ca2+ load.

Experiments were performed using HEPES (panels A–D) or HCO3− (panels E–H) as buffers. A, E. Representative traces and summary data for percentages of sarcomere shortening, and B, F. Ca2+ transient (CaT) measured using Fura-2 ratio (RFURA) from WT and Slc26a6−/− cardiomyocytes. C, G. Representative traces of sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) Ca2+ load measurement of WT and Slc26a6−/− ventricular myocytes. The myocytes were first paced to steady state, and then pacing was stopped for 15 s followed by a rapid application of 20 mM caffeine to induce SR Ca2+ release. D, H. Summary data for SR Ca2+ load from WT and Slc26a6−/− ventricular myocytes. Numbers within the bar graphs represent the sample sizes.

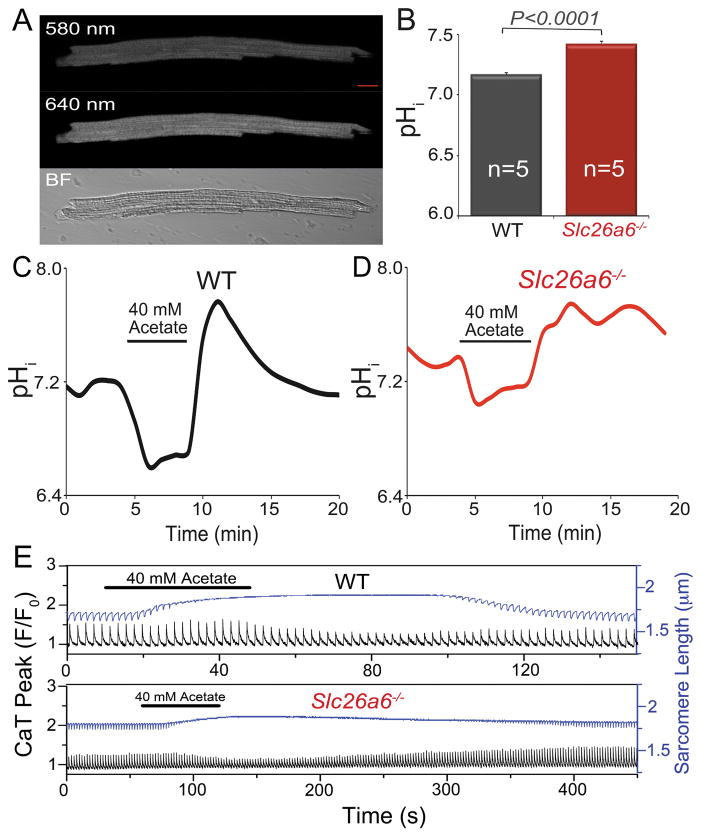

Roles of Slc26a6 in pHi regulation

To test whether the Cl−/HCO3− exchange, mediated by Slc26a6, contributes to pHi regulation in ventricular myocytes, we directly measured the pHi of cardiomyocytes by using SNARF-1 AM pH dye, as shown in Fig. 3A and B. The pHi in resting Slc26a6−/− cardiomyocytes was 7.42 ± 0.02, significantly higher than that of 7.16 ± 0.02 in WT cardiomyocytes (n=5, *p<0.05). To test the function of Slc26a6 in acid loading, we first induced intracellular acidification by wash in of 40 mM acetate followed by an immediate wash out, and monitored the pHi recovery from alkalization. The pHi in WT cardiomyocytes recovered to the baseline level over time (Fig. 3C), whereas there was a delay in the recovery of pHi in Slc26a6−/− cardiomyocytes, over the same period of time (Fig. 3D). The results suggested an impairment of the acidification process in Slc26a6−/− cardiomyocytes and participation of Slc26a6 in the acid loading in cardiomyocytes.

Figure 3. Slc26a6−/− cardiomyocytes show higher intracellular pH (pHi).

A. Measurement of pHi in ventricular myocytes by SNARF-1 AM using confocal microscopy (scale bar: 10 μm). Loaded cells were excited by 488 nm laser and images were acquired by using two band-pass filters with center wavelengths of 580 nm and 640 nm, respectively. The ratio of the emission signals at 580 nm and 640 nm was calculated and converted to pH value following the standard methods described before15–17. A bright field (BF) image of the cardiomyocyte was also shown at the lower panel. B. Comparisons of pHi between WT and Slc26a6−/− cardiomyocytes. Alternations and recoveries of pHi when 40 mM acetate was applied in WT (C) and Slc26a6−/− (D) ventricular myocytes. EIPA (5 μM) was added to inhibit the Na+/H+ exchanger during acetate application. E. Effects of 40 mM acetate on the CaT and sarcomere length in WT and Slc26a6−/− ventricular myocytes. EIPA (5 μM) was added to inhibit the Na+/H+ exchanger during acetate application. The recovery process after wash out of acetate for Slc26a6−/− myocytes is much slower than that of WT myocytes. The black traces showed the CaT, and the blue traces showed the sarcomere length.

We reason, based on its exchange activities, that Slc26a6 contributes to acid loading in cardiomyocytes under normal physiological condition, and that ablation of Slc26a6 may delay the acid loading process and affect the sarcomere shortening and CaT. We perfused ventricular myocytes with a solution containing 40 mM sodium acetate to acidify the cytosol, and monitored the sarcomere shortening and CaT, as shown in Fig. 3E. Acid loading resulted in marked reduction of sarcomere shortening in both WT and Slc26a6−/−. The CaT was initially enhanced slightly, and then inhibited by acetate-induced intracellular acidification. Moreover, after wash out of acetate, the recovery process of sarcomere shortening and CaT was much slower in Slc26a6−/− cardiomyocytes, consistent with Slc26a6 exchange activities (please note that different scales were used for upper and lower panels). The immediate alkalization during the wash out of acetate also inhibited contraction of the cardiomyocytes.

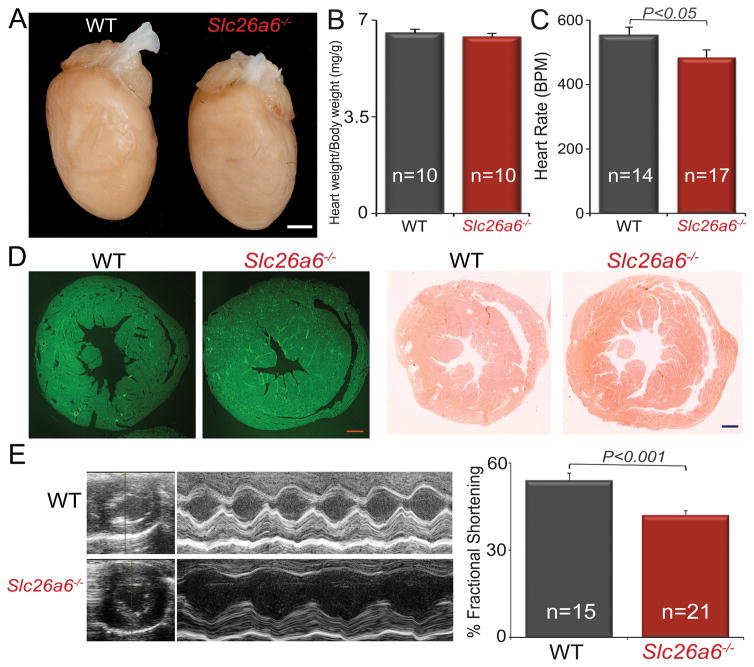

A decrease in fractional shortening in Slc26a6−/− mice

The above cellular data strongly support the contributions of Slc26a6 to cardiac pHi, APD, and contractility. To test the effects of reduced CaT and sarcomere shortening in Slc26a6−/− on in vivo cardiac function, we performed echocardiography in conscious mice. There was no evidence of cardiac hypertrophy or dilation, with no significant differences in heart/body weight ratios between WT and Slc26a6−/− mice (Fig. 4A&B). However, Slc26a6−/− mice showed evidence of sinus bradycardia (Fig. 4C). Histological analyses, using wheat germ agglutinin and Picrosirius Red stain, of cardiac sections demonstrated no evidence of cardiac fibrosis, hypertrophy, or dilation in Slc26a6−/− mice (Fig. 4D). However, there was a significant reduction in the fractional shortening in Slc26a6−/− mice compared to WT controls (Fig. 4E).

Figure 4. Slc26a6−/− mice demonstrate worsening fractional shortening and sinus bradycardia.

A. Photomicrographs of whole heart of WT and Slc26a6−/− mice (Scale bar,1 mm). B. Summary for heart/body weight ratio in mg/g. C. Heart rate. (BPM: beat per minute). D. Wheat germ agglutinin (left two panels) and Picrosirius Red (right two panels) staining of cardiac sections from WT and Slc26a6−/− mice demonstrating no evidence of increase fibrosis in the knockout mice (scale bar, 0.5 mm). E. 2D and M-mode echocardiography from WT and Slc26a6−/− mice. The right panel shows summary data for fractional shortening (%FS), illustrating a significant decrease in %FS in KO mice compared to WT.

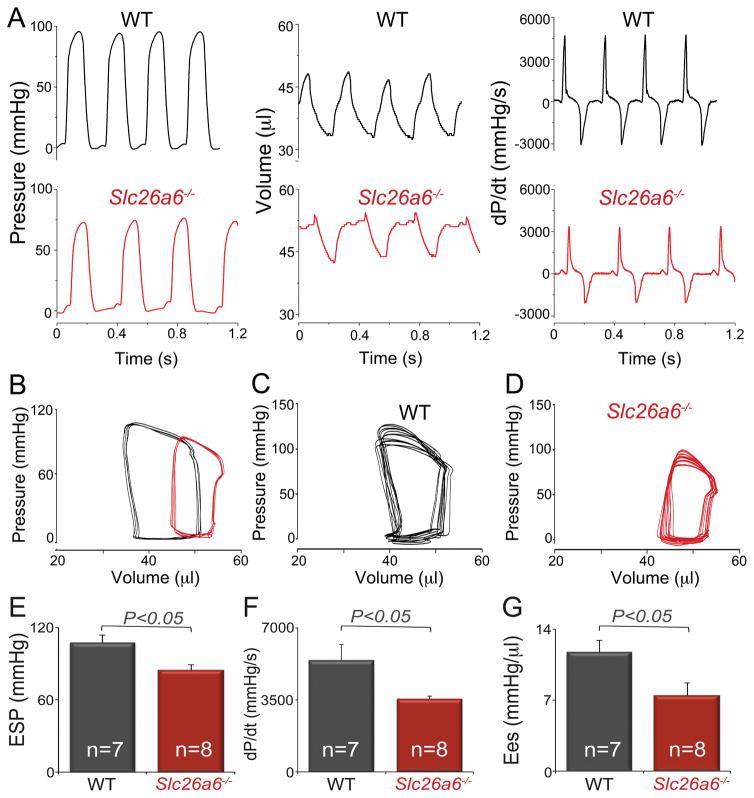

Indeed, hemodynamic monitoring demonstrated a significant decrease in cardiac contractility in Slc26a6−/− mice compared to WT controls. Shown in Fig. 5A are representative recordings of left ventricular pressure, volume, and developed pressure (dP/dt) in WT and Slc26a6−/− mice. There was a significant right and downward shift of the pressure-volume (P-V) loops in Slc26a6−/− mice, indicating reduced end systolic pressure and relatively larger end systolic and diastolic volumes, with reduced stroke volume (Fig. 5B). To determine the end systolic P-V relationship, we obtained a series of P-V loops by altering the preload and derived the slope of the end systolic P-V relationship (Ees), a load independent measure of cardiac contractility (Fig. 5C&D for WT and Slc26a6−/−, respectively). Consistent with the cellular data and echocardiography data, the end systolic pressure (Fig. 5E), maximum dP/dt (Fig. 5F), and Ees (Fig. 5G) in Slc26a6−/− mice were significantly reduced compared to those of WT mice, supporting a decrease in cardiac contractility in Slc26a6−/− mice.

Figure 5. Hemodynamics monitoring from Slc26a6−/− and WT mice demonstrates the reduced cardiac contractility in Slc26a6−/− mice.

A. Recording traces of left ventricular pressure, volume, and derivative of pressure with respect to time (dP/dt) from WT and Slc26a6−/− mice. B. P-V loop analysis. The pressure and volume have been calibrated. The volume calibration was performed using cuvette (P/N 910-1049, Millar Inc.) filled with fresh heparinized 37° C mouse blood. A series of P-V loops when the preload was altered in WT (C) and Slc26a6−/− mice (D). E, F, G. Summary data for end systolic pressure (ESP), maximum dP/dt, and the slope of the end systolic P-V relationship (Ees).

Fragmented QRS complex in Slc26a6−/− mice

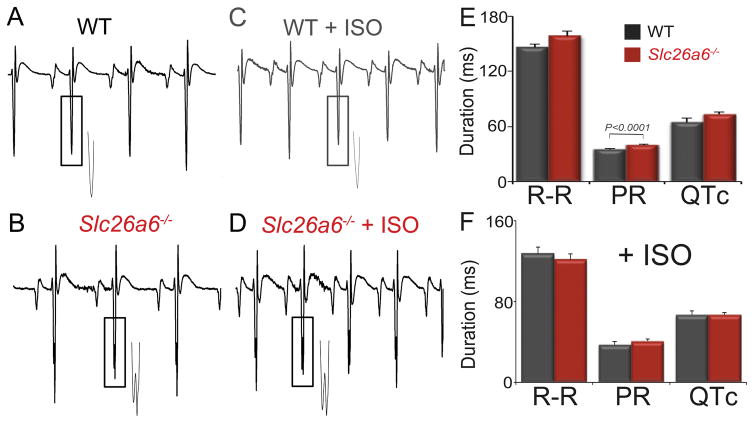

Cellular electrophysiology and pHi measurement of Slc26a6−/− cardiomyocytes demonstrated the shortening of APD90 and an elevated pHi (Fig. 1 & 3). We, therefore, compared the ECG between WT and Slc26a6−/− mice (Fig. 6A&B). Slc26a6−/− mice showed evidence of fragmented QRS complex with prolonged PR interval. The QRS complex duration of Slc26a6−/− mice was significantly prolonged compared to that of WT mice (22.8 ± 0.8 ms vs 20.3 ± 0.5 ms; n=8, p< 0.05). Mice were challenged with subcutaneous isoproterenol (ISO, 25 mg/kg, Fig. 6C&D). ISO injection increased heart rates, but fragmented QRS complexes remained in Slc26a6−/− mice. Summary data are shown in Fig. 6E&F. Of note, even though the heart rate measured by echocardiography was significantly reduced in unanesthesized Slc26a6−/− compared to WT mice (Fig. 4C), only the PR intervals were significantly prolonged in the anesthetized Slc26a6−/− mice during ECG recordings (Fig. 6E). These in vivo findings suggest critical roles of Slc26a6 in cardiac conduction systems that warrant additional future investigations.

Figure 6. ECG recordings from age-matched WT and Slc26a6−/− mice reveal evidence of fragmented QRS complexes in the knockout mice.

A to D. Representative ECG traces. The insets showed the enlarged traces marked by the rectangular boxes demonstrating fragmented QRS complexes observed only in Slc26a6−/− mice. E. ECG parameters in control condition and with isoproterenol (ISO) (F).

Molecular identification of human cardiac SLC26A6 isoforms

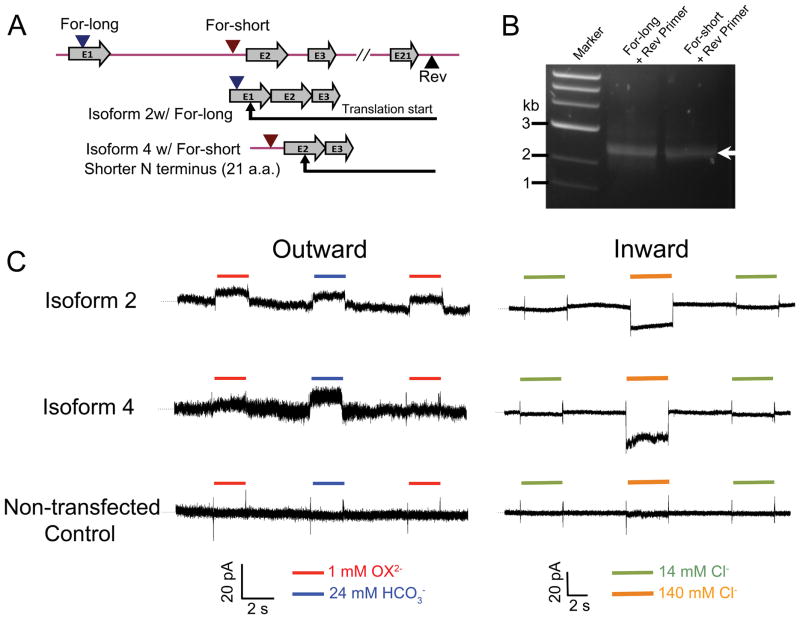

Previous studies suggest that Cl−/oxalate exchange of mouse Slc26a6 is electrogenic, while the human SLC26A6 mediates electroneutral Cl−/oxalate exchange.18, 19 To directly test whether there are indeed species differences, we performed RT-PCR to clone full-length SLC26A6 from human heart (Fig. 7).

Figure 7. Molecular identification and functional analysis of human cardiac SLC26A6 isoforms.

A. The cloning strategy. Two different forward primers, For-long and For-short, were designed, corresponding to the genomic DNA sequence in chromosome 3 (NC_000003.12), one on 5′-UTR of exon 1 and the other on the intron sequence between exon 1 and exon 2, to verify isoforms having distinct 5′-UTR and/or 5′-end of coding sequence. The exon structure of the cloned isoforms was shown below. B. RT–PCR amplification of the full-length cDNA of human cardiac SLC26A6 isoforms (indicated by an arrow) using two sets of primers. C. Patch-clamp recordings and fast solution exchange to activate two heterologously expressed human cardiac SLC26A6 isoforms that we have obtained. The outward current was activated by the solution exchange diagram shown in Fig.1B, and the inward current was activated by the solution exchange diagram shown in Fig.1G. Recordings on non-transfected CHO cells were shown at the bottom. Dotted lines represent zero current.

Six different transcript variants of human SLC26A6 have previously been described. During the cloning of human cardiac SLC26A6, two major transcript variants were repetitively obtained, suggesting the presence of alternatively spliced variants of SLC26A6 in human heart. We used a For-long and Rev primer set, as well as a For-short and Rev primer set (Fig. 7A); the PCR products were shown in Fig. 7B. 12 clones were randomly selected for each primer set, compared by restriction enzyme digestion, and full-length sequence confirmed by sequencing. Sequence analysis revealed that the two identified isoforms correspond to previously described transcript variant 2 (NM_134263.2) and transcript variant 4 (NM_001040454.1) for primer set 1 and 2, respectively. Variant 4 is 21 amino acids shorter in the N-terminus compared to transcript variant 2 (see protein sequence alignment in Supplementary Figure 3).

Electrogenic Cl−/oxalate and Cl−/HCO3− exchange activities mediated by human cardiac SLC26A6 isoforms

To test the function of the human cardiac SLC26A6, we expressed the human cardiac SLC26A6 isoforms in CHO cells and recorded the current generated by the anion exchanger, using patch-clamp coupled with a fast solution exchange technique, as described in Fig. 1B &G. Membrane potential was held at 0 mV. Fig. 7C shows the outward currents generated by electrogenic Cl−/oxalate and Cl−/HCO3− exchanges, and the inward currents generated by Cl−/HCO3− exchanges. Both variants identified in human hearts are functional electrogenic Cl−/oxalate and Cl−/HCO3− exchangers.

Discussion

Slc26a6 has been proposed to be the predominant Cl−/HCO3− exchanger and a specific Cl−/OH− exchanger in the mouse heart, based on transcript levels.6 Our group has since identified four cardiac Slc26a6 isoforms in the mouse heart, and importantly, we demonstrated that mouse cardiac Slc26a6 mediates eletrogenic Cl−/HCO3− exchange activities in cardiac myocytes.7 We predict, based on its electrogenic activities, that Slc26a6 may participate not only in the regulation of pHi, but also in cardiac excitability. To directly test this hypothesis, we took advantage of Slc26a6−/− mice. Consistent with our prediction, ablation of Slc26a6 significantly shortens APD, resulting in reduced sarcomere shortening, CaT, and SR Ca2+ load, in addition to an elevated pHi. Moreover, our in vivo studies demonstrate decreased fractional shortening and cardiac contractility, as well as sinus bradycardia in the knockout mice. For the first time, our results uncover new insights into the critical roles of cardiac electrogenic anion transporter—linking the regulation of not only pHi, but also cardiac excitability and contractility.

Roles of bicarbonate in cardiac pH regulation

HCO3−/CO2 buffer is the major component of the cellular pH buffering system. Bicarbonate is the byproduct of mitochondrial respiration; therefore, its concentration is highly affected by physiological and pathological conditions. HCO3− is critical for pH regulation, acid/base secretion, and body fluid secretion.20, 21 Although CO2 can diffuse across the plasma membrane, HCO3− transport across the plasma membrane requires facilitation by HCO3− transporters and anion channels. HCO3− transporters are encoded by 14 genes belonging to SLC4A and SLC26A gene families.20

The heart is an organ with a high metabolic rate, due to its continuous mechanical activities. Therefore, HCO3− is a critical anion in the regulation of cardiac function1, 2. Unlike Na+, K+ and Ca2+ ions, which directly affect the excitability and contractility of the heart, HCO3− participates in the regulation of cardiac function through its coupled transport with other cations and anions, as well as its direct control of cardiac pH. Therefore, it is a unique anion in the heart with dynamic regulation and a wide range of function. HCO3− participates in acid extruding and acid loading processes in cardiomyocytes, which are coupled with Na+ and Cl− transport, respectively.1 Our studies provided strong evidence to support the role of Slc26a6 as an acid loader contributing to the acid loading process in cardiomyocytes. Since cardiac Slc26a6 mediates Cl−/HCO3− and Cl−/OH− exchange, our study also demonstrated the critical roles of Cl− in regulation of cardiac function through Slc26a6.

Electrogenic properties of human SLC26A6

In contrast to our current findings, previous studies suggest that human SLC26A6 may not be electrogenic.18, 19 These studies, however, used an oocyte expression system and indirect measurement of changes in reversal potentials, wherein intracellular ion concentrations were unknown and could not be precisely controlled during the recordings. In contrast, we used patch-clamp recordings with fast solution exchange to precisely set the ion gradient across the plasma membrane and monitor the dynamic changes of the currents. We observed electrogenic Cl−/HCO3− and Cl−/oxalate exchange activities of both mouse and human cardiac SLC26A6 (Fig. 7).

Critical roles of electrogenic transporters in cardiac excitability

Electrogenic transporters contribute significantly to cardiac excitability. The well described Na+/K+ pump contributes to the generation of resting membrane potentials and repolarization of cardiac action potentials.22 Another electrogenic transporter, Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (NCX), is not only important in intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis and cardiac contractility, but also in the regulation of cardiac excitability and arrhythmogenesis. Similar to Slc26a6−/−, cardiac-specific NCX knockout mice show an abbreviated APD in cardiomyocytes.23–25 Additionally, the electrogenic Na+/HCO3− cotransporter was reported to modulate resting membrane potentials and cardiac APs.26

Slc26a6 mediates eletrogenic Cl−/HCO3− exchange in the heart, thus regulating cardiac APD, as we demonstrate for the first time in this study. Based on the predicted stoichiometry of Slc26a6, at least two HCO3− are exchanged for one Cl− ion, with estimated reversal potential of the exchange of ~+36 mV. Under physiological condition, the activation of Slc26a6 generates inward currents, which depolarize the membrane potential.7 Consistently, Slc26a6−/− cardiomyocytes show shortened cardiac APs.

Functional roles of Slc26a6 in acid loading process in cardiomyocytes

The elevated pHi in Slc26a6−/− cardiomyocytes supports the essential role of Slc26a6 in the acid loading process.1, 2, 6, 7 Under physiological conditions, Slc26a6 mediates Cl−/HCO3− or Cl−/OH− exchange, maintaining a relatively lower pHi and higher intracellular Cl− concentration in cardiomyocytes. Here, we directly monitored the acidification process during the application and wash out of acetate. Slc26a6−/− cardiomyocytes show delayed acidification, supporting the role of Slc26a6 in cellular acid loading (Fig. 3).

In addition to Slc26a6, it has been reported that Slc4a families are expressed in cardiomyocytes, including AE1 (Slc4a1), AE2 (Slc4a2), and AE3 (Slc4a3), which are acid loaders. Other Slc4a members are mostly Na+/HCO3− cotransporters, mediating acid extrusion. However, the expression levels of AE1, AE2, AE3, as well as Slc26a3 are relatively low compared to Slc26a6.6 Nonetheless, it is possible that there is compensation from AE and other Slc26a families during the pHi recovery process. The dominant molecule for acid loading is Slc26a6 because its expression level is nearly one hundred fold higher than that of AEs and Slc26a3.

Decreased cardiac contractility in Slc26a6−/− mice

The shortened cardiac APs are predicted to decrease Ca2+ influx through L-type Ca2+ channels, leading to reduced CaT and sarcomere fractional shortening in Slc26a6−/− cardiomyocytes. Additionally, the elevated pHi may contribute to changes in CaT and contractility. Indeed, pHi is a critical regulator of cardiac ion channels and transporters, as well as other membrane and contractile proteins, and, therefore, exerts significant influences on cardiac Ca2+ signaling, contractility, and excitability.1, 2 Effects of acidosis on cardiac function have been extensively investigated due to its pathological significance during ischemia-reperfusion.27–34 Cellular acidification reduces CaT and contraction in cardiomyocytes.1, 27, 29, 31, 35 Our results showed that CaT was initially enhanced and later inhibited by cellular acidification, induced by wash in of acetate (Fig. 3E) when Na+/H+ exchanger was inhibited, similar to that observed by Vaughan-Jones et al.1 The reduced sarcomere shortening observed in our study from acidification (Fig. 3E), agrees with previously reported findings.

On the other hand, effects of intracellular alkalization on cardiac contractility and CaT are less understood. Our findings in Fig. 3E demonstrate that acid loading had a relatively small influence on CaT compared to cell shortening in both WT and Slc26a6−/− myocytes, however, alkalization during wash out dramatically decreased CaT and cell shortening. The findings suggest that lower pHi had a minor effect on CaT, but may affect the Ca2+ affinity of troponin C.1 Taken together, the impairment of cardiac contractility in Slc26a6−/− mice is likely due to multiple mechanisms, including alterations in pHi, in addition to reduced APDs, CaT, and SR Ca2+ load.

Future studies

One previous study using a different strain of Slc26a6−/− mice reported normal body weight, heart rate, and blood pressure in Slc26a6−/− mice.36 Our studies demonstrate comparable heart/body weight ratio between WT and Slc26a6−/− mice, however, there is evidence of sinus bradycardia and fragmented QRS complex in Slc26a6−/− mice with prolonged PR interval. Fragmented QRS complexes have been shown to be common in patients post myocardial infarction; they may represent a marker for cardiovascular diseases37–39, and predict arrhythmic events and mortality in patients with cardiomyopathy.40, 41 Fragmented QRS was also reported to be associated with prognosis in patients with Brugada syndrome, supporting the association of fragmented QRS and arrhythmia substrate.42 Slc26a6−/− mice showed sinus bradycardia and fragmented QRS, however, there is no significant cardiac fibrosis in Slc26a6−/− mice. Our findings of fragmented QRS complexes and prolonged PR interval in Slc26a6−/− mice support the critical role of Slc26a6 not only in ventricular myocytes, but also in the cardiac conduction system. Sinus bradycardia in Slc26a6−/− mice further suggests functional roles of Slc26a6 in pacemaking cells.

In addition, the elevated pHi may result in changes in gene expression profiles, as well as the function of other membrane and cytosolic proteins. For example, pHi may affect APDs of rabbit and guinea pig ventricular myocytes by H+-induced changes in late Ca2+ entry through the L-type Ca2+ channel.43 Therefore, we expect a spectrum of cellular proteins which need to be further evaluated. However, these extensive investigations will be performed in our future experiments.

The global knockout of Slc26a6 was reported to affect the kidney and duodenum epithelial transport36 and induce Ca2+ oxalate urolithiasis.8 The alteration in metabolic profiles in Slc26a6−/− may affect the observed in vivo cardiac function. Therefore, we took advantage of not only in vivo physiological measurement, but also in vitro analyses in our studies to circumvent these possible confounding factors. Indeed, our in vivo findings are consistent with in vitro analyses.

In conclusion, the in vivo and in vitro studies unravel novel mechanistic insights into the newly described and unique cardiac electrogenic Cl−/HCO3− transporter in ventricular myocytes. Activities of Slc26a6 contribute not only to the regulation of pHi, but also cardiac AP and contractility. Ablation of Slc26a6 shortens the APDs, impairs cardiac function, and results in fragmented QRS complexes and elevated pHi. Additional studies are required to further understand the functional roles of Slc26a6 not only in ventricular myocytes, but also in pacemaking cells and the cardiac conduction system.

Supplementary Material

WHAT IS KNOWN?

Intracellular pH (pHi) is critical to cardiac excitation and contraction. Uncompensated changes in pHi impair cardiac function and trigger arrhythmias, however, cardiac pHi regulation mechanisms are not completely understood.

Our previous studies identified several isoforms of a solute carrier, Slc26a6, to be highly expressed in mouse cardiomyocytes. We demonstrated that Slc26a6 mediates electrogenic Cl−/HCO3− exchange activities in cardiomyocytes supporting the role of Slc26a6 in the regulation of pHi and cardiac function.

WHAT THE STUDY ADDS?

Ablation of Slc26a6 resulted in action potential (AP) shortening, reduced Ca2+ transient and sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ load, decreased sarcomere shortening, and elevated pHi in mouse cardiomyocytes.

At in vivo level, Slc26a6 knockout mice showed reduced fractional shortening and cardiac contractility, as well as fragmented QRS complexes, supporting the critical roles of Slc26a6 in the regulation of cardiac excitability and contractility.

For the first time, we identified human cardiac SLC26A6 isoforms and demonstrated their electrogenic Cl−/HCO3− exchange activities.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Peter S. Aronson (Yale University) for his kind gift of Slc26a6 knockout mice and reading of our manuscript.

Sources of Funding: This study was supported, in part, by American Heart Association Beginning Grant-in-Aid 14BGIA18870087 (Dr Zhang), National Institutes of Health (NIH) R01 DC015135, NIH R01 DC015252, NIH R01 DC016099, and NIH P01 AG051443 (Dr Yamoah), NIH R01 HL123526 (Dr Chen-Izu), NIH R01 HL085727, NIH R01 HL085844, NIH R01 HL137228, and S10 RR033106 (Dr Chiamvimonvat), VA Merit Review Grant I01 BX000576 and I01 CX001490 (Dr Chiamvimonvat), and American Heart Association Postdoctoral Fellowship Award (Dr Sirish). Dr Sirish received Postdoctoral Fellowship from California Institute for Regenerative Medicine Training Grant to UC Davis and NIH/National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) Institutional Training Grant in Basic and Translational Cardiovascular Science (T32 NIH HL086350). H.A. Ledford and R. Shimkunas received Predoctoral Fellowship from NIH/NHLBI Institutional Training Grant in Basic and Translational Cardiovascular Science (T32 NIH HL086350) and NIH F31 Predoctoral Awards. M. Moshref received Predoctoral Fellowship from the Training Core of the NIH/National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) UC Davis Superfund Program (P42 NIH ES004699). Dr Chiamvimonvat is the holder of the Roger Tatarian Endowed Professorship in Cardiovascular Medicine, University of California, Davis and a Staff Cardiologist, VA Medical Center, Mather, CA.

Footnotes

Disclosures: None.

References

- 1.Vaughan-Jones RD, Spitzer KW, Swietach P. Intracellular pH regulation in heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2009;46:318–331. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang HS, Chen Y, Vairamani K, Shull GE. Critical role of bicarbonate and bicarbonate transporters in cardiac function. World journal of biological chemistry. 2014;5:334–345. doi: 10.4331/wjbc.v5.i3.334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mount DB, Romero MF. The slc26 gene family of multifunctional anion exchangers. Pflugers Arch. 2004;447:710–721. doi: 10.1007/s00424-003-1090-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dorwart MR, Shcheynikov N, Yang D, Muallem S. The solute carrier 26 family of proteins in epithelial ion transport. Physiology (Bethesda) 2008;23:104–114. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00037.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alper SL, Sharma AK. The slc26 gene family of anion transporters and channels. Molecular aspects of medicine. 2013;34:494–515. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2012.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alvarez BV, Kieller DM, Quon AL, Markovich D, Casey JR. Slc26a6: A cardiac chloride-hydroxyl exchanger and predominant chloride-bicarbonate exchanger of the mouse heart. J Physiol. 2004;561:721–734. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.077339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim HJ, Myers R, Sihn CR, Rafizadeh S, Zhang XD. Slc26a6 functions as an electrogenic Cl−/HCO3− exchanger in cardiac myocytes. Cardiovascular Research. 2013;100:383–391. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvt195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jiang Z, Asplin JR, Evan AP, Rajendran VM, Velazquez H, Nottoli TP, Binder HJ, Aronson PS. Calcium oxalate urolithiasis in mice lacking anion transporter slc26a6. Nat Genet. 2006;38:474–478. doi: 10.1038/ng1762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sirish P, Li N, Timofeyev V, Zhang XD, Wang L, Yang J, Lee KS, Bettaieb A, Ma SM, Lee JH, Su D, Lau VC, Myers RE, Lieu DK, Lopez JE, Young JN, Yamoah EN, Haj F, Ripplinger CM, Hammock BD, Chiamvimonvat N. Molecular mechanisms and new treatment paradigm for atrial fibrillation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2016:9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.115.003721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang XD, Timofeyev V, Li N, Myers RE, Zhang DM, Singapuri A, Lau VC, Bond CT, Adelman J, Lieu DK, Chiamvimonvat N. Critical roles of a small conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel (SK3) in the repolarization process of atrial myocytes. Cardiovascular Research. 2014;101:317–325. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvt262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mitchell GF, Jeron A, Koren G. Measurement of heart rate and Q-T interval in the conscious mouse. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:H747–751. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.274.3.H747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jian Z, Han H, Zhang T, Puglisi J, Izu LT, Shaw JA, Onofiok E, Erickson JR, Chen YJ, Horvath B, Shimkunas R, Xiao W, Li Y, Pan T, Chan J, Banyasz T, Tardiff JC, Chiamvimonvat N, Bers DM, Lam KS, Chen-Izu Y. Mechanochemotransduction during cardiomyocyte contraction is mediated by localized nitric oxide signaling. Science signaling. 2014;7:ra27. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2005046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thomas RC. Experimental displacement of intracellular pH and the mechanism of its subsequent recovery. J Physiol. 1984;354:3P–22P. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roos A, Boron WF. Intracellular pH. Physiol Rev. 1981;61:296–434. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1981.61.2.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buckler KJ, Vaughan-Jones RD. Application of a new pH-sensitive fluoroprobe (carboxy-snarf-1) for intracellular pH measurement in small, isolated cells. Pflugers Arch. 1990;417:234–239. doi: 10.1007/BF00370705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blank PS, Silverman HS, Chung OY, Hogue BA, Stern MD, Hansford RG, Lakatta EG, Capogrossi MC. Cytosolic pH measurements in single cardiac myocytes using carboxy-seminaphthorhodafluor-1. Am J Physiol. 1992;263:H276–284. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1992.263.1.H276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Niederer SA, Swietach P, Wilson DA, Smith NP, Vaughan-Jones RD. Measuring and modeling chloride-hydroxyl exchange in the guinea-pig ventricular myocyte. Biophys J. 2008;94:2385–2403. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.118885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chernova MN, Jiang L, Friedman DJ, Darman RB, Lohi H, Kere J, Vandorpe DH, Alper SL. Functional comparison of mouse slc26a6 anion exchanger with human SLC26A6 polypeptide variants: Differences in anion selectivity, regulation, and electrogenicity. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:8564–8580. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411703200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clark JS, Vandorpe DH, Chernova MN, Heneghan JF, Stewart AK, Alper SL. Species differences in Cl− affinity and in electrogenicity of slc26a6-mediated oxalate/Cl− exchange correlate with the distinct human and mouse susceptibilities to nephrolithiasis. J Physiol. 2008;586:1291–1306. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.143222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cordat E, Casey JR. Bicarbonate transport in cell physiology and disease. Biochem J. 2009;417:423–439. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Casey JR, Grinstein S, Orlowski J. Sensors and regulators of intracellular pH. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:50–61. doi: 10.1038/nrm2820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bueno-Orovio A, Sanchez C, Pueyo E, Rodriguez B. Na+/K+ pump regulation of cardiac repolarization: Insights from a systems biology approach. Pflugers Arch. 2014;466:183–193. doi: 10.1007/s00424-013-1293-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pott C, Henderson SA, Goldhaber JI, Philipson KD. Na+/Ca2+ exchanger knockout mice: Plasticity of cardiac excitation-contraction coupling. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1099:270–275. doi: 10.1196/annals.1387.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pott C, Ren X, Tran DX, Yang MJ, Henderson S, Jordan MC, Roos KP, Garfinkel A, Philipson KD, Goldhaber JI. Mechanism of shortened action potential duration in Na+-Ca2+ exchanger knockout mice. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;292:C968–973. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00177.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pott C, Philipson KD, Goldhaber JI. Excitation-contraction coupling in Na+-Ca2+ exchanger knockout mice: Reduced transsarcolemmal Ca2+ flux. Circ Res. 2005;97:1288–1295. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000196563.84231.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Villa-Abrille MC, Petroff MG, Aiello EA. The electrogenic Na+/HCO3− cotransport modulates resting membrane potential and action potential duration in cat ventricular myocytes. J Physiol. 2007;578:819–829. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.120170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bountra C, Vaughan-Jones RD. Effect of intracellular and extracellular pH on contraction in isolated, mammalian cardiac muscle. J Physiol. 1989;418:163–187. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1989.sp017833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vaughan-Jones RD, Wu ML, Bountra C. Sodium-hydrogen exchange and its role in controlling contractility during acidosis in cardiac muscle. Mol Cell Biochem. 1989;89:157–162. doi: 10.1007/BF00220769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Orchard CH, Kentish JC. Effects of changes of pH on the contractile function of cardiac muscle. Am J Physiol. 1990;258:C967–981. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1990.258.6.C967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harrison SM, Frampton JE, McCall E, Boyett MR, Orchard CH. Contraction and intracellular Ca2+, Na+, and H+ during acidosis in rat ventricular myocytes. Am J Physiol. 1992;262:C348–357. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1992.262.2.C348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fabiato A, Fabiato F. Effects of pH on the myofilaments and the sarcoplasmic reticulum of skinned cells from cardiace and skeletal muscles. J Physiol. 1978;276:233–255. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1978.sp012231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Steenbergen C, Deleeuw G, Rich T, Williamson JR. Effects of acidosis and ischemia on contractility and intracellular pH of rat heart. Circ Res. 1977;41:849–858. doi: 10.1161/01.res.41.6.849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Garlick PB, Radda GK, Seeley PJ. Studies of acidosis in the ischaemic heart by phosphorus nuclear magnetic resonance. Biochem J. 1979;184:547–554. doi: 10.1042/bj1840547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yan GX, Kleber AG. Changes in extracellular and intracellular pH in ischemic rabbit papillary muscle. Circ Res. 1992;71:460–470. doi: 10.1161/01.res.71.2.460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Choi HS, Trafford AW, Orchard CH, Eisner DA. The effect of acidosis on systolic Ca2+ and sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium content in isolated rat ventricular myocytes. J Physiol. 2000;529(Pt 3):661–668. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00661.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang Z, Wang T, Petrovic S, Tuo B, Riederer B, Barone S, Lorenz JN, Seidler U, Aronson PS, Soleimani M. Renal and intestinal transport defects in slc26a6-null mice. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2005;288:C957–965. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00505.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Flowers NC, Horan LG, Thomas JR, Tolleson WJ. The anatomic basis for high-frequency components in the electrocardiogram. Circulation. 1969;39:531–539. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.39.4.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chatterjee S, Changawala N. Fragmented QRS complex: A novel marker of cardiovascular disease. Clinical cardiology. 2010;33:68–71. doi: 10.1002/clc.20709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pietrasik G, Zareba W. QRS fragmentation: Diagnostic and prognostic significance. Cardiology journal. 2012;19:114–121. doi: 10.5603/cj.2012.0022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Das MK, Maskoun W, Shen C, Michael MA, Suradi H, Desai M, Subbarao R, Bhakta D. Fragmented QRS on twelve-lead electrocardiogram predicts arrhythmic events in patients with ischemic and nonischemic cardiomyopathy. Heart Rhythm. 2010;7:74–80. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2009.09.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Das MK, Saha C, El Masry H, Peng J, Dandamudi G, Mahenthiran J, McHenry P, Zipes DP. Fragmented QRS on a 12-lead ECG: A predictor of mortality and cardiac events in patients with coronary artery disease. Heart Rhythm. 2007;4:1385–1392. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2007.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Morita H, Watanabe A, Morimoto Y, Kawada S, Tachibana M, Nakagawa K, Nishii N, Ito H. Distribution and prognostic significance of fragmented QRS in patients with brugada syndrome. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2017:10. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.116.004765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saegusa N, Moorhouse E, Vaughan-Jones RD, Spitzer KW. Influence of pH on Ca2+ current and its control of electrical and Ca2+ signaling in ventricular myocytes. J Gen Physiol. 2011;138:537–559. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201110658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.