Abstract

For youth and parents, frequent family meals have been consistently associated with positive dietary outcomes but less consistently associated with lower body mass index (BMI). Researchers have speculated dinnertime context (dinnertime routines, parent dinnertime media use) may interact with family meal frequency to impact associations with BMI. The present study evaluates the associations and interactions between dinnertime context measures and family dinner frequency with parent and child BMI. This cross-sectional study uses baseline data from the Healthy Home Offerings via the Mealtime Environment (HOME) Plus randomized control trial that aimed to prevent childhood obesity. Participants (160 parent/child dyads) completed psychosocial surveys and were measured for height and weight. General linear models tested associations and interactions between dinnertime context measures and family dinner frequency with parent and child BMI, adjusted for race and economic assistance. Lower parent dinnertime media use and higher dinnertime routines were significantly associated with lower child BMI z-scores but not parent BMI scores. Interaction/moderation findings suggest higher family dinner frequency amplifies the healthful impact of the dinnertime context on child BMI z-scores. Additionally, findings emphasize that promoting frequent family meals and consistent routines and reduction in parent dinnertime media use may be important for the prevention of childhood obesity.

Keywords: Family meals, family mealtime context, obesity, youth, parents

Research has consistently linked higher family meal frequency with more healthful dietary intake (e.g., higher fruit and vegetable intake, less sugar-sweetened beverage intake) in youth (Fulkerson, Larson, Horning, & Neumark-Sztainer, 2014a; Hammons & Fiese, 2011; Martin-Biggers et al., 2014) and parents (Berge, Maclehose, & Loth, 2013; Blake, Wethington, Farrell, Bisogni, & Devine, 2011; Fulkerson et al., 2014a; Welsh, French, & Wall, 2011). However, associations between higher family meal frequency and lower body mass index (BMI) for youth and their parents have not been consistently found in the literature (Berge et al., 2013; Berge et al., 2015; Berge, Wickel, & Doherty, 2012; Chan & Sobal, 2011; Fulkerson et al., 2014a; Hammons & Fiese, 2011; Martin-Biggers et al., 2014; Sobal & Hanson, 2014). Thus, more research is needed to understand if other aspects of family meals, beyond meal frequency, are important for healthful weight outcomes. This research may provide new avenues by which to work with families to promote healthful family meals and healthful weight outcomes.

In light of inconsistent associations between family meal frequency and weight outcomes, researchers have begun to investigate how dinnertime routines may contribute to weight outcomes. Dinnertime routines may promote mindfulness of hunger and satiety cues, comradery, mentoring, monitoring, and modeling of healthful behaviors, which could lead to healthier weight outcomes (Fiese, Hammons, & Grigsby-Toussaint, 2012). Additionally, researchers studying the impact of context have found that having established roles and routines for family mealtimes is inversely associated with youth BMI (Berge, Jin, Hannan, & Neumark-Sztainer, 2013; Berge et al., 2014; Fiese et al., 2012; Jacobs & Fiese, 2007; Wansink & van Kleef, 2014) and parent BMI (Wansink & van Kleef, 2014).

In addition to family dinner routines, another important aspect of family meals that could help explain inconsistent associations between family meal frequency and BMI is dinnertime media use, as less dinnertime media use may also promote family engagement, role-modeling or attention to hunger/satiety cues. Watching television (Feldman, Eisenberg, Neumark-Sztainer, & Story, 2007; FitzPatrick, Edmunds, & Dennison, 2007) and using other forms of electronic media during meals (Fulkerson et al., 2014b) have been associated with serving less healthful foods at family mealtimes (FitzPatrick et al., 2007; Fulkerson et al., 2014b) and less healthful dietary intake among youth (Andaya, Arredondo, Alcaraz, Lindsay, & Elder, 2011; Feldman et al., 2007) and parents (Boutelle, Birnbaum, Lytle, Murray, & Story, 2003). Research has also explored, but not found, significant associations between TV/electronics use during meals and child or parent BMI (Berge et al., 2014; Jacobs & Fiese, 2007; Wansink & van Kleef, 2014); however, the link between poor dietary intake and media use at dinner suggests dinnertime media use may be a concern for long-term weight outcomes.

Researchers have theorized the dinnertime context (i.e., dinnertime routines and dinnertime media use) may play a role in the lack of consistent associations between family meal frequency and youth and parent BMI found across studies (Berge et al., 2015; Fulkerson et al., 2014a; Martin-Biggers et al., 2014). Specifically, recent research has shown family meal frequency measures that include a family dinnertime context component (e.g., sitting and eating with your family rather than just “eat meal together”) are significantly associated with youth BMI outcomes while family meal frequency measures that exclude a context component are not significantly associated with youth BMI outcomes (Horning, Fulkerson, Friend, & Neumark-Sztainer, 2016). Thus, it stands to reason that a positive mealtime context (Berge et al., 2015; Fiese, Foley, & Spagnola, 2006; Fulkerson et al., 2014a; Martin-Biggers et al., 2014; Spagnola & Fiese, 2007), with more consistent family routines and less frequent parent dinnertime media use, provides families more opportunity to engage with one another (e.g., via role modeling or healthful eating mentoring or monitoring), which may be associated with healthier dietary intake and ultimately healthier BMI. If this reasoning is true, the magnitude of the impact of the dinnertime context would depend on the frequency at which meals are occurring. In other words, theoretically it is plausible that family dinner frequency may moderate associations between dinnertime context and BMI of children and parents. Given the negative impact of overweight/obesity on health outcomes (Centers for Disease Control [CDC], 2012 Centers for Disease Control [CDC], 2016), it is important to be able to understand and intervene on important aspects of the family meal that may prevent excess weight gain, whether they are related to mealtime context, meal frequency or both.

Aligned with the developing body of family meal frequency and family dinnertime context research, the aims of this study were two-fold. The first aim of this paper was to examine associations between dinnertime routines and parent dinnertime media use and child and parent BMI outcomes. It was hypothesized that dinnertime routines would be inversely associated, and dinnertime media use would be positively associated, with parent and child BMI. The second aim was to examine whether family dinner frequency moderated the relationship between significant mealtime context measures (from aim one) and child and parent BMI outcomes. It was hypothesized family dinner frequency would amplify the associations hypothesized in aim one, specifically, that greater frequency of family dinners would provide greater opportunity for dinnertime context to influence family behaviors and dynamics, and ultimately, BMI.

Methods

Study Design and Sample

The present cross-sectional study uses baseline data from the Healthy Home Offerings via the Mealtime Environment (HOME) Plus randomized controlled trial (Fulkerson et al., 2015). The HOME Plus study was designed to prevent childhood obesity through a family-focused intervention promoting family meal frequency, the healthfulness of meals and snacks, and reductions in screen time at meals (Fulkerson et al., 2015). The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Minnesota. Parents provided written consent; child participants provided written assent.

The HOME Plus study recruited 160 parent-child dyads (i.e., the primary meal-preparing parent and one of their 8-12 year old children) from the Twin Cities metropolitan area of Minnesota in 2011-2012. Baseline data collection occurred prior to randomization and intervention. Inclusion criteria for trial participation included English fluency, no plans to move within 6 months of the trial start, not having medical conditions that would limit participation (e.g., life-threating food allergies), and the child having BMI for age at or above the 50th percentile. Further details of the trial design, recruitment procedures, and data collection methods are published elsewhere (Fulkerson et al., 2014c; Fulkerson et al., 2015).

Measures

Parents completed a psychosocial survey that included questions related to sociodemographic characteristics, family dinner frequency, and the dinnertime context (i.e., dinnertime routines and parent dinnertime media use).

Sociodemographic Characteristics

Parents reported their gender, race, education level, family receipt of economic assistance (e.g., Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program [SNAP], Women Infants and Children [WIC], free- or reduced- price school lunch) and total number of individuals in the household. Parents reported their child's race; children reported their own gender.

Family Meal Frequency

Consistent with past research (Fulkerson, Story, Neumark-Sztainer, & Rydell, 2008; Larson et al., 2013; Powers, 2005), parents reported family meal frequency by responding to the following question: “During the past 7 days, how many times were you sitting and eating with your child when he/she ate his/her dinner?” with response options from zero to seven days a week.

Family Dinnertime Routines

Family Dinnertime Routines were measured with a six-item scale adapted from the eight-item dinnertime portion of the Family Routines Questionnaire (original α's=0.88, 0.90, Fiese & Kline, 1993; α=0.73, Fiese et al., 2012). The Family Dinnertime Routines Scale used in this analysis (current sample α=0.71) included the following stem/items: “In my family: 1) everyone has a specific role and job to do at dinner time; 2) dinner time is flexible, people eat when they can; 3) everyone is expected to be home for dinner; 4) people feel strongly about eating dinner together; 5) dinner time is just for getting food; and 6) there is little planning around dinner time.” Response options were changed from the original format (i.e., ‘for our family sort of true’ or ‘for our family really true’) to ‘not true,’ ‘sort of true,’ ‘true’ (i.e., 1-3). Items were coded and summed so higher scores represent more regular, predictable family dinner routines.

Parent Dinnertime Media Use

An existing scale (Fulkerson et al., 2014b) measuring adolescent report of their dinnertime media use (2-week test-retest r=0.87) was adapted for this study to measure parent report of their dinnertime media use. Specifically, Parent Dinnertime Media Use was measured with a six-item scale (current sample α=0.74). Items on the scale included: “During the dinner meal how often do you: 1) watch TV or movies? 2) talk on the phone? 3) text message? 4) email? 5) read the mail or newspaper? and 6) use the computer?” The first three items were unchanged, items four and five were adapted from youth activities (replaced ‘playing video games’ and ‘listening to music with headphones’ with activities more common among adults), and item six was added to capture computer use, which was not previously measured. Response options of 1 (never) to 4 (usually/always) were the same as the original 5-item scale. Items were coded so higher scores reflect higher parent dinnertime media use.

Body Mass Index

Trained research staff measured parent and child height and weight using calibrated scales and following standardized protocols (Lohman, Roche, & Martorell, 1988). BMI (weight(kg)/height(m)2) was calculated using parent and child anthropometry data. For children, BMI was standardized for age and gender (BMI z-score) using the Centers for Disease Control guidelines and growth charts (CDC, 2013). Parents who identified as pregnant (n=3) were excluded from analyses.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to describe sample characteristics. Race was dichotomized (i.e., white, nonwhite) for analysis due to small numbers. Control variables of race and economic assistance receipt were chosen because both variables are significantly associated with BMI within our sample and in the research literature. Moderation analyses were used to test the hypotheses (Baron & Kenny, 1986) and main predictor variables (family dinner frequency, Dinnertime Routines, Parent Dinnertime Media Use) were mean centered (Frazier & Barron, 2004). Two separate general linear models were used to assess associations between each dinnertime context measure and the outcome of parent BMI, adjusted for parent race and economic assistance receipt. The same two models were then run for the child BMI z-score outcome, adjusting for child race and economic assistance receipt. If the dinnertime context measure was significantly related to the outcome, then subsequent individual interaction models were run to test for associations between the interaction term and the BMI outcome. These interaction models include race, economic assistance, the dinnertime context measure, family dinner frequency, and the interaction term between the context measure and frequency. For example, Dinnertime Routines Scale scores, family dinner frequency and the interaction term (i.e., family dinner frequency*Dinnertime Routines Scale scores) were regressed on child BMI z-scores while the model was adjusted for race and economic assistance receipt. When interaction terms were significant, predicted values for child BMI z-score were calculated and plotted using moderation model parameters at one standard deviation below the mean, at the mean, and above the mean, for each of the main predictor variables. All analyses were performed using SAS software, version 9.3 (SAS Institute, NC, USA). Interaction plots were made in Microsoft Excel. Statistical significance was set to p≤0.05 for all analyses.

Results

The majority of parent participants were white (77%) and female (95%). Additionally, many parents (59%) reported having received a bachelor's or higher degree and over one-third of families reported receiving economic assistance. Child participants were split almost evenly between male and female with a mean age of 10.4 years. See Table 1 for additional sample details.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of Parent (n=160) and Child (n=160) Participants of the HOME Plus Trial.

| Characteristics | n | (%) | M (SD) | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parent race | ||||

| American Indian | 4 | (3) | ||

| Asian | 1 | (1) | ||

| Black / African American | 24 | (15) | ||

| White | 123 | (77) | ||

| More than one race | 8 | (5) | ||

| Parent education | ||||

| Less than high school | 3 | (2) | ||

| High school | 11 | (7) | ||

| Some college | 31 | (20) | ||

| Associates degree | 19 | (12) | ||

| Bachelor's degree or higher | 54 | (35) | ||

| Graduate degree | 37 | (24) | ||

| Parent gender | ||||

| Female | 152 | (95) | ||

| Male | 8 | (5) | ||

| Parent BMIa | 28.5 (7.30) | 17.3-53.1 | ||

| Child race | ||||

| American Indian | 4 | (3) | ||

| Asian | 3 | (2) | ||

| Black / African American | 28 | (18) | ||

| White | 109 | (68) | ||

| More than one race | 16 | (10) | ||

| Child gender | ||||

| Female | 75 | (47) | ||

| Male | 85 | (53) | ||

| Child age | 10.4 (1.41) | 8.0-12.9 | ||

| Child BMI z-scores | 1.0 (0.75) | -0.5-2.7 | ||

| Receipt of economic assistance | ||||

| Yes | 62 | (39) | ||

| No | 98 | (61) | ||

| Total number in household | 4.1 (1.31) | 2-9 | ||

| Family dinner frequency | 4.7 (2.02) | 0-7 | ||

| Dinnertime context measures | ||||

| Family Dinnertime Rituals and Routines | 13.9 (2.70) | 7-18 | ||

| Parent Dinnertime Media Use | 9.3 (2.96) | 6-18 |

Notes. More than one race refers to participants selecting one or more of the racial categories.

BMI = Body Mass Index.

Excludes those that identified as pregnant (n=3).

Dinnertime context measures were significantly associated with child BMI z-scores but not parent BMI. Specifically, Family Dinnertime Routines Scale scores were significantly and inversely associated with child BMI z-scores (β=-0.05, SE=0.02, p=0.02). Parent Dinnertime Media Use scores were significantly and positively associated with child BMI z-scores (β=0.04, SE=0.02, p=0.03). Family Dinnertime Routines Scale scores (β=-0.33, SE=0.21, p=0.14) were not significantly associated with parent BMI. Parent Dinnertime Media Use scores (β=0.15, SE= 0.20, p=0.46) were also not associated with parent BMI.

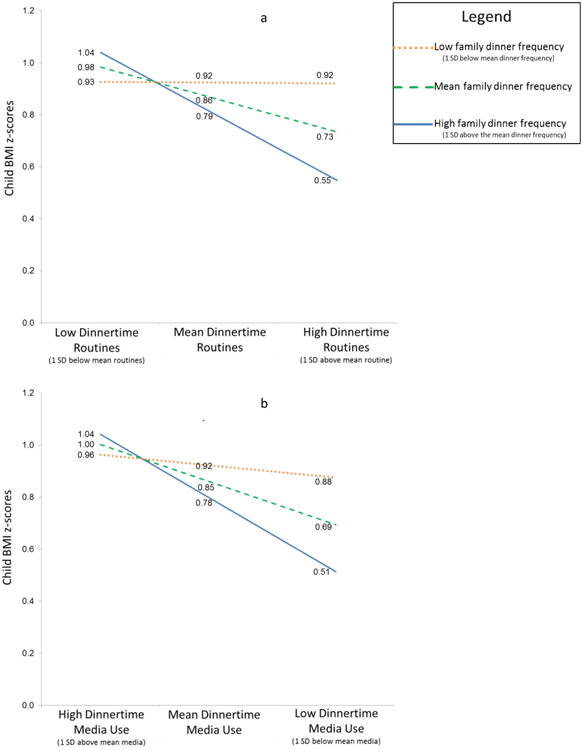

In each of the interaction models testing for moderation, each dinnertime context measure was found to significantly interact with family dinner frequency on child BMI outcomes. Specifically, the interaction term of Family Dinnertime Routines Scale and family dinner frequency was significantly associated with child BMI z-scores (β=-0.02, SE=0.01, p=0.04). The interaction term between Parent Dinnertime Media Use and family dinner frequency was also significantly associated with child BMI z-scores (β=0.02, SE=0.01, p=0.03). See Figure 1 for the plotted predicted child BMI z-scores at specified values for family meal frequency and the dinnertime context variable.

Figure 1.

Interaction plots of predicted child BMI z-scores at specified values of family dinner frequency and Family Dinnertime Routine scores (shown in Figure 1a) or Parent Dinnertime Media Use scores (shown in Figure 1b) from the HOME Plus study (n=160). SD=Standard deviation.

Discussion

The current study examined associations and interactions between dinnertime context measures (i.e., dinnertime routines and parental dinnertime media use) and family dinner frequency that may be protective against obesity. Findings suggest dinnertime context may be an important correlate of child BMI outcomes and that the dinnertime context may interact in important ways with family dinner frequency in relationship to child but not parent BMI.

Specifically, having more routines around dinnertime or less parental dinnertime media use was associated with lower child BMI z-scores. Additionally, the interaction model findings and subsequent interaction plots indicate how family dinner frequency amplifies the association between each dinnertime context variable and child BMI z-scores. For example, as visible within Figure 1a, low Family Dinnertime Routine scores and any level of family meal frequency (low, average, high) results in child BMI z-scores that are very similar across three family dinner frequency levels. In contrast, when Family Dinnertime Routine scale scores are at average or high levels and family meal frequency is average or high, child BMI z-scores are in lower ranges. A similar moderation effect was also found between parent dinnertime media use and family dinner frequency (with low levels of media use considered more healthful; Figure 1b) on child BMI z-scores. Overall, the moderation effects found in this research are logical, as a positive context around family meals (e.g., more routines, less media use allowing for role modeling, connections, and attention to cues of hunger and satiety) would be likely to have more impact on child BMI z-scores, if meals are occurring more frequently.

Although needing further validation in future studies, the moderation effects found in the present research between family dinnertime context variables and family meal frequency could play a role in and/or explain the inconsistent findings between family meal frequency and youth BMI in the research literature. However, it is also possible that positive meal contexts and consuming frequent family meals together are proxies for other family characteristics, such as higher levels of family functioning, interest in health promoting behaviors, ability to have family meals, and priority on having meals together that are known to lead to healthier child outcomes (Fiese, Winter, & Botti, 2011; Fiese et al., 2012; Neumark-Sztainer, Eisenberg, Fulkerson, Story & Larson, 2008). Regardless, results suggest promoting both family meals and positive dinnertime contexts may be important to facilitate healthful BMI of children.

In particular, creatively promoting both family meal frequency and positive dinnertime contexts may be important for families facing both structural and social challenges (e.g., rotating work shifts may disrupt the creation of regular dinnertime routines and also influence ability to have frequent family meals). For example, working with families to develop routines around the mealtime even if the mealtime is varied from the norm may facilitate development of mealtime routines. Alternatively, promoting family meals at times other than dinner (e.g., breakfast, weekend lunches) may also help families to overcome scheduling barriers. Regardless of barriers, it may be especially beneficial to use a tailored approach to help families identify whether meal frequency or mealtime context would be easiest and most important for them to address first (e.g., meals without media/cellphones/TV use). Based on study findings, family psychologists and other professionals promoting family health may find that encouragement of frequent family meals, dinnertime routines, and decreased dinnertime media use enhances family togetherness, which is already a part of their practice goals.

Strengths and Limitations

The present research adds to the research literature by including both family dinner frequency and dinnertime context measures in analyses with BMI outcomes, as most studies do not. The present study also goes beyond testing direct associations between BMI outcomes and dinner frequency or dinnertime context measures. More specifically, this study also tested and found family dinner frequency and the dinnertime context measures interact in relation to child BMI outcomes. These findings provide novel insight for future research and additional avenues to consider in supporting healthful BMI outcomes for families.

The present study is not without limitations. In particular, this study is cross-sectional, so findings noted are correlational and do not provide directionality of effect, highlighting the need for future longitudinal research to assess associations over time. Additionally, parents self-reported survey responses (versus direct observation), specific data on which family members were present at the meals were not collected, and children's report of their dinnertime media use was not included in this study. Key constructs in this study were measured with adapted scales from the literature and results should be interpreted with caution until they are validated in future studies. The family meal frequency measure only captures the frequency of dinner rather than all meals (i.e., breakfast, lunch, dinner); however, research has found dinner frequency to be strongly correlated with overall family meal frequency (Larson et al., 2013). Finally, parents and children in this study are not representative of all families with 8-12 year old children, as children had to be at or above the 50th percentile for BMI z-scores for inclusion, parents were highly educated and were less racially/ethnically diverse than national averages, and families voluntarily enrolled in research on family meals and healthful eating. As a result of these sample characteristics, generalizing findings is cautioned as families who enroll in studies are inherently different than families who do not enroll and families with children with BMI at or above the 50th percentile may approach dinnertime context and family meals differently than families with children below the 50th percentile for BMI. Future research is needed in samples with more diversity to corroborate findings. Additionally, household composition, in all of its complexity (e.g., multi-generational households; step-families where children have two families) should be explored as a potential covariate in future dinnertime context research, as household composition could influence the overall dinnertime context.

Conclusions

Although associations between BMI outcomes and family dinner frequency and dinnertime context have not been consistently significant in the literature, the present study extends previous research findings by suggesting family dinner frequency may amplify the impact of the dinnertime context measures on child BMI z-scores. Therefore, promotion of frequent family meals in conjunction with consistent routines and reduction in parent dinnertime media use may be important for the prevention of childhood obesity.

Acknowledgments

The HOME Plus trial is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01538615. The research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under award number R01DK08400 (PI: Fulkerson). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the views of the NIH. Software support was also provided by the University of Minnesota's Clinical and Translational Science Institute (Grant Number UL1TR000114 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the NIH).

Footnotes

The ideas and analyses presented in this secondary analysis manuscript have not been previously disseminated. The general demographic data used to describe the study samples' demographic characteristics have been disseminated in other HOME Plus trial publications.

Contributor Information

Melissa L. Horning, School of Nursing, University of Minnesota

Robin Schow, Healthy Foods, Healthy Lives Institute, University of Minnesota.

Sarah E. Friend, School of Nursing, University of Minnesota

Katie Loth, Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, University of Minnesota.

Dianne Neumark-Sztainer, Division of Epidemiology and Community Health, School of Public Health, University of Minnesota.

Jayne A. Fulkerson, School of Nursing, University of Minnesota

References

- Andaya A, Arredondo E, Alcaraz J, Lindsay S, Elder J. The association between family meals, TV viewing during meals, and fruit, vegetables, soda, and chips intake among Latino children. Journal of Nutrition Education Behavior. 2011;43:308–315. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51(6):1173–1182. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berge JM, Jin SW, Hannan P, Neumark-Sztainer D. Structural and interpersonal characteristics of family meals: Associations with adolescent body mass index and dietary patterns. Journal of Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. 2013;113(6):816–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2013.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berge JM, Maclehose RF, Loth KA. Family meals: Associations with weight and eating behaviors among mothers and fathers. Appetite. 2013;58(3):1128–1135. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2012.03.008.Family. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berge JM, Rowley S, Trofholz A, Hanson C, Rueter M, MacLehose RF, Neumark-Sztainer D. Childhood obesity and interpersonal dynamics during family meals. Pediatrics. 2014;134(5):923–932. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-1936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berge JM, Wall M, Hsueh TF, Fulkerson JA, Larson N, Neumark-Sztainer D. The protective role of family meals for youth obesity: 10-year longitudinal associations. Journal of Pediatrics. 2015;166(2):296–301. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.08.030. doi:S0022-3476(14)00777-X [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berge JM, Wickel K, Doherty WJ. The individual and combined influence of the “quality” and “quantity” of family meals on adult body mass index. Families, Systems, & Health. 2012;30(4):344–351. doi: 10.1037/a0030660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake CE, Wethington E, Farrell TJ, Bisogni CA, Devine CM. Behavioral contexts, food-choice coping strategies, and dietary quality of a multiethnic sample of employed parents. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2011;111(3):401–407. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2010.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutelle KN, Birnbaum AS, Lytle LA, Murray DM, Story M. Associations between perceived family meal environment and parent intake of fruit, vegetables, and fat. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior. 2003;35(1):24–29. doi: 10.1016/s1499-4046(06)60323-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Overweight and obesity: Causes and consequences. 2012 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/obesity/adult/causes/index.html.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. A growing problem: What causes childhood obesity? 2016 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/obesity/childhood/problem.html.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Growth chart training: A SAS program. 2013 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dnpao/growthcharts/resources/sas.htm.

- Chan JC, Sobal J. Family meals and body weight. analysis of multiple family members in family units. Appetite. 2011;57(2):517–524. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2011.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman S, Eisenberg ME, Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M. Associations between watching TV during family meals and dietary intake among adolescents. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior. 2007;39:257–263. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2007.04.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiese BH, Foley K, Spagnola M. Routine and ritual elements in family mealtimes: Contexts for child well-being and family identity. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development. 2006;111:67–89. doi: 10.1002/cd.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiese BH, Hammons A, Grigsby-Toussaint D. Family mealtimes: A contextual approach to understanding childhood obesity. Economics & Human Biology. 2012;10(4):365–374. doi: 10.1016/j.ehb.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiese BH, Jones BL. Food and family: A socio-ecological perspective for child development. Advances in Child Development and Behavior. 2012;42:307–337. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-12-394388-0.00009-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiese BH, Kline CA. Development of the family ritual questionnaire: Initial reliability and validation studies. Journal of Family Psychology. 1993;6(3):290–299. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.6.3.290. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fiese BH, Winter MA, Botti JC. The ABCs of family mealtimes: Observational lessons for promoting healthy outcomes for children with persistent asthma. Child Development. 2011;82(1):133–145. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01545.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FitzPatrick E, Edmunds LS, Dennison BA. Positive effects of family dinner are undone by television viewing. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2007;107(4):666–671. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2007.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frazier P, Barron KE. Testing moderator and mediator effects in counseling psychology research. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2004;51(2):115–134. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.51.1.115. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fulkerson JA, Friend S, Flattum C, Horning M, Draxten M, Neumark-Sztainer D, et al. Kubik MY. Promoting healthful family meals to prevent obesity: HOME plus, a randomized controlled trial. The International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2015;12 doi: 10.1186/s12966-015-0320-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulkerson JA, Larson N, Horning M, Neumark-Sztainer D. A review of associations between family or shared meal frequency and dietary and weight status outcomes across the lifespan. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior. 2014a;46(1):2–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2013.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulkerson JA, Loth K, Bruening M, Berge J, Eisenberg ME, Neumark-Sztainer D. Time 2 tlk 2nite: Use of electronic media by adolescents during family meals and associations with demographic characteristics, family characteristics, and foods served. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. 2014b;114(7):1053–1058. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2013.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulkerson JA, Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, Gurvich O, Kubik MY, Garwick A, Dudovitz B. The Healthy Home Offerings via the Mealtime Environment (HOME) Plus study: Design and methods. Contemporary Clinical Trials. 2014c;38(1):59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2014.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulkerson J, Story M, Neumark-Sztainer D, Rydell S. Family meals: Perceptions of benefits and challenges among parents of 8- to 10-year-old children. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2008;108(4):706–709. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammons AJ, Fiese BH. Is frequency of shared family meals related to the nutritional health of children and adolescents? Pediatrics. 2011;127(6):e1565–1574. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-1440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horning ML, Fulkerson JA, Friend SE, Neumark-Sztainer D. Associations among nine family dinner frequency measures and child weight, dietary, and psychosocial outcomes. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. 2016;116(6):991–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2015.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs MP, Fiese BH. Family mealtime interactions and overweight children with asthma: Potential for compounded risks? Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2007;32(1):64–68. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsl026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson N, MacLehose R, Fulkerson J, Berge J, Story M, Neumark-Sztainer D. Eating breakfast and dinner together as a family: Associations with sociodemographic characteristics and implication for diet quality and weight status. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. 2013;113(12):1601–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2013.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohman T, Roche A, Martorell R. Anthropometric standardization reference manual. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics Books; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Biggers J, Spaccarotella K, Berhaupt-Glickstein A, Hongu N, Worobey J, Byrd-Bredbenner C. Come and get it! A discussion of family mealtime literature and factors affecting obesity risk. Advances in Nutrition: An International Review Journal. 2014;5(3):235–247. doi: 10.3945/an.113.005116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumark-Sztainer D, Eisenberg M, Fulkerson J, Story M, Larson N. Family meals and disordered eating in adolescents: Longitudinal findings from project EAT. Archives of Pediatric Adolescent Medicine. 2008;162:17–22. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2007.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers SW. Parenting practices and obesity in low-income African-American preschoolers. 3. Cincinnati, OH: Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center, University of Cincinnati College of Medicine; 2005. Retrieved from http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED486144.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Sobal J, Hanson K. Family dinner frequency, settings and sources, and body weight in US adults. Appetite. 2014;78:81–88. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2014.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spagnola M, Fiese BH. Family routines and rituals: A context for development in the lives of young children. Infants & Young Children. 2007;20(4):284–299. doi: 10.1097/01.IYC.0000290352.32170.5a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wansink B, van Kleef E. Dinner rituals that correlate with child and adult BMI. Obesity. 2014;22(5):E91–5. doi: 10.1002/oby.20629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsh EM, French SA, Wall M. Examining the relationship between family meal frequency and individual dietary intake: Does family cohesion play a role? Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior. 2011;43(4):229–235. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]