Abstract

Glutathione-S-transferases (GSTs) are encoded by genes belonging to a wide ubiquitous family in aerobic species and catalyze the conjugation of electrophilic substrates to glutathione (GSH). GSTs are divided in different classes, both in plants and animals. In plants, GSTs function in several pathways, including those related to secondary metabolites biosynthesis, hormone homeostasis, defense from pathogens and allow the prevention and detoxification of damage from heavy metals and herbicides. 1107 GST protein sequences from 20 different plant species with sequenced genomes were analyzed. Our analysis assigns 666 unclassified GSTs proteins to specific classes, remarking the wide heterogeneity of this gene family. Moreover, we highlighted the presence of further subclasses within each class. Regarding the class GST-Tau, one possible subclass appears to be present in all the Tau members of ancestor plant species. Moreover, the results highlight the presence of members of the Tau class in Marchantiophytes and confirm previous observations on the absence of GST-Tau in Bryophytes and green algae. These results support the hypothesis regarding the paraphyletic origin of Bryophytes, but also suggest that Marchantiophytes may be on the same branch leading to superior plants, depicting an alternative model for green plants evolution.

Introduction

Glutathione-S-transferases (GSTs) are enzymes encoded by a ubiquitous gene family in aerobic species, able to conjugate electrophilic xenobiotics and endogenous cell components with glutathione (GSH)1. GSTs in plants are composed of two subunits with a molecular mass of around 25–29 kD2.

Initially, plant GSTs were identified in Zea mays for their involvement in defense mechanisms against damage by herbicide3. The importance of GSTs in herbicide tolerance has been demonstrated expressing maize GSTs in tobacco plants. The treated plants were revealed to have a greater herbicide tolerance compared to untreated tobacco plants4. GSTs can also act as detoxifying agents from endogenous cell components. For example, Bronze 2 in maize has been demonstrated to be involved in anthocyanin transport into cytoplasmic vacuoles5. A similar behavior has been highlighted for An9 in Petunia hybrida 6, TT19 in Arabidopsis thaliana 7, PGSC0003DMG400016722 in Solanum tuberosum 8 and DQ198153 in Citrus sinensis, cultivar Moro nucellare9, suggesting that, probably, GSTs act in the last step of the anthocyanin biosynthetic pathway10, when these molecules are transported to the vacuole.

GSTs are also important for the prevention of heavy metals damage, facilitating their storage in the vacuole. In particular, a truncated isoform of the protein encoded by Bronze 2 in maize has a high affinity for heavy metals11. Moreover, GSTs may take part in the hydrogen peroxide detoxification12.

GSTs have a high affinity for auxins and cytokinins and this suggests that GSTs are important for hormone homeostasis and in plant defense against pathogens2,13. In fact, in Solanum tuberosum, the plants infected with the pathogen fungus Phytophthora infestans revealed a fast increase in the prp 1-1 GST content, accompanied by the increase of intracellular auxin levels, suggesting the association of the phenomena to infection defense13.

Initially, plant GSTs were classified into four categories, type I, II, III and IV, based on amino acids sequence identity and on the conservation of the gene structure14,15. This classification was modified into 7 GST classes: 6 cytoplasmic classes (Tau, Phi, Zeta, Theta, Lambda and Dhar) and a further microsomal class (Mapeg)2,16.

Tau and Phi classes are considered plant specific classes, being the most representative in terms of the number of sequences16. In 2016, Munyampundu et al. demonstrated that the Phi class is also present in bacteria, fungi and protists. Tau and Phi classes link a wide range of xenobiotics16, or endogenous cell components17. These components function as glutathione peroxidases (GPOXs), as flavonoid-binding proteins6–9, and as stress-signaling proteins18. Moreover, the Tau class expansion appears to be associated with plant adaptation to land living19.

The Zeta class is linked to tyrosine degradation, catalyzing the GSH-dependent conversion of malelyacetoacetate to fumarylacetoacetate. The Theta class is similar to the corresponding mammalian class9 and it is present in bacteria, insects, plants, fish, and mammals20.

Lambda and Dhar classes were identified comparing the human Omega GSTs versus the Arabidopsis genome17.

Finally, the Mapeg class includes the microsomal GSTs, with transferase and peroxidase activities21.

Recently more 6 GST classes have been identified in plants: TCHQD, EF1Bγ, URE2p, Omega-like, Iota and Hemerythrin19. Members of the URE2p class were found in Physcomitrella patens, in Selaginella moellendorffii and in bacteria, probably because of horizontal gene transfer events in bacteria, while the Iota GST class was found only in Physcomitrella patens and in Selaginella moellendorffii 19. Hemerythrin GSTs are non-heme iron binding proteins found in metazoans, prokaryotes, protozoans, and fungi22, which acts in detoxification from heavy metals by catalyzing the conjugation of GSH with metal ions19.

A phylogenetic analysis made both in monocots (maize and rice) and in dicots (soya and Arabidopsis) demonstrated that Zeta and Theta classes are monophyletic groups in monocots, dicots and mammals, suggesting that their origin might be anterior to the division between plants and animals23. Zeta and Theta classes have undergone one or two duplication events, presenting at maximum three paralogs in maize, rice, soya and Arabidopsis. Phi and Tau classes show differences between monocots and dicots due to the extensive gene duplication events that monocots and dicots underwent after their divergence. Extensive duplications also resulted in genic clusters sharing high similarity in small genome regions. The reasons of these retained extensive gene duplications are still unknown23.

1107 GSTs from 20 different plant species with sequenced genomes were analyzed (Table 1) to reveal the organization of this relevant family in plants. Two green algae genomes, two Bryophytes, one Marchantiophyta, one Lycopodiophyta, one Gymnosperm, three monocots, ten dicots, including the reference plant species Arabidopsis thaliana (family Brassicaceae), were examined.

Table 1.

List of plants considered for this study. Scientific name (name) of the organisms considered, their classification (A (CHL): Algae Chlorophyta, A (CHA): Algae Charophyta, B: Bryophyta, L: Lycophyta, MA: Marchantiophyta, G: Gymnosperms, M: Monocots, D: Dicots), number of chromosomes (Chr), genome size estimation in Mb (Genome), total number of genes currently estimated (Gene), genomics resource, bibliographical reference (Source + Reference) and publication year (Year).

| Name | Type | Chr (n) | Genome (Mb) | Gene (n) | Source + Reference | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vitis vinifera | D | 19 | 475 | 30434 | Cribi (v2) Jaillon et al. | 2007 |

| Solanum tuberosum | D | 12 | 844 | 39031 | Spud db (PGSC_DM_v_3.4) The Potato Genome Sequencing Consortium | 2011 |

| Solanum lycopersicum | D | 12 | 900 | 34727 | SGN (iTAG2.4) The Tomato Genome Consortium | 2012 |

| Populus trichocarpa | D | 19 | 422.9 | 45778 | Phytozome 11 (v3.0) Tuskan et al. | 2006 |

| Glycine max | D | 20 | 1115 | 46430 | Gramene Schmuz et al. | 2010 |

| Coffee canephora | D | 11 | 710 | 25574 | Coffee genome Hub Denoeud et al. | 2014 |

| Citrus sinensis | D | 9 | 367 | 29445 | Licciardello et al. Xu et al. | 2012 |

| Capsicum annum | D | 12 | 3349 | 35336 | SGN (v1.55) Qin et al. | 2014 |

| Arabidopsis thaliana | D | 5 | 125 | 25498 | TAIR10 The Arabidopsis Genome Initiative | 2000 |

| Amborella trichopoda | D | 13 | 870 | 14000 | Phytozome 11 (v1.0) Amborella Genome Project | 2013 |

| Zea mays | M | 10 | 2300 | 32540 | Phytozome 11 (Ensembl-18) Schnable et al. | 2009 |

| Spirodela polyrhiza | M | 20 | 158 | 19623 | Phytozome 11 (v2) Wang et al. | 2013 |

| Oryza sativa | M | 12 | 420 | 29961 | TIGR Goff et al. | 2005 |

| Picea abies | G | 12 | 19600 | 28354 | Congenie (v1) Nystedt et al. | 2013 |

| Selaginella moellendorffii | L | 27 | 212.5 | 22285 | Phytozome 11 (v1.0) | |

| Banks et al. | 2011 | |||||

| Marchantia polymorpha | MA | / | 225.8 | 19287 | Phytozome 11 (v3.1) https://phytozome.jgi.doe.gov | 2016 |

| Sphagnum fallax | B | / | 395 | 26939 | Phytozome 11 (v0.5) https://phytozome.jgi.doe.gov | 2015 |

| Physcomitrella patens | B | 27 | 510 | 35938 | Liu et al. Rensing et al. | 2008 |

| Klebsormidium flaccidum | A (CHA) | 22–26 | 117.1 ± 21.8 | 16215 | CGA Hori et al. | 2014 |

| Micromonas pusilla CCMP1545 | A (CHL) | 17 | 21.95 | 10575 | Phytozome 11 (v3.0) Worden et al. | 2009 |

Results

Class assignment of unclassified GSTs

The collection of 1107 GST protein sequences from the 20 species consisted of 214 Tau, 53 Phi, 41 Theta, 7 Lambda, 23 Dhar, 28 Zeta, 21 Mapeg, 10 Hemerythrin, 15 EF-gamma, 4 URE2p, 9 TCHQD, 2 Iota and 16 Omega-like GSTs. In addition, 666 unclassified GSTs were also included (Table 2, numbers in brackets).

Table 2.

Number of GSTs per species and per class. Type classes as in Table 1.

| Type | Tot | TAU | PHI | THETA | LAMBDA | DHAR | ZETA | MAPEG | HEMERY-THRIN | El-F2 gamma | URE2p | TCHQD | IOTA | Omega-like | Not classified before the analysis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vitis vinifera | D | 132 | 88 (96) | 13 (11) | 2 (2) | 2 (/) | 2 (3) | 16 (10) | 3 (/) | / (/) | 2 (/) | / (/) | 1 (1) | / (/) | 3 (/) | 9 |

| Solanum tuberosum | D | 88 | 58 (/) | 5 (/) | 3 (/) | 6 (1) | 2 (5) | 8 (2) | 1 (1) | / (/) | 1 (/) | / (/) | 1 (1) | / (/) | 2 (/) | 78 |

| Solanum lycopersicum | D | 86 | 68 (4) | 5 (1) | / (10) | 2 (/) | 3 (/) | 3 (/) | 1 (1) | / (/) | 1 (/) | / (/) | 1 (1) | / (/) | 2 (/) | 69 |

| Populus trichocarpa | D | 79 | 66 (/) | 6 (/) | 2 (/) | 1 (/) | / (/) | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | / (/) | 2 (2) | / (/) | / (/) | / (/) | / (/) | 74 |

| Glycine max | D | 15 | 12 (12) | 1 (1) | / (/) | / (/) | / (/) | 2 (2) | / (/) | / (/) | / (/) | / (/) | / (/) | / (/) | / (/) | / |

| Coffee canephora | D | 54 | 34 (12) | 3 (2) | 7 (7) | / (/) | 2 (2) | 4 (4) | 2 (2) | / (/) | 1 (/) | / (/) | 1 (1) | / (/) | / (/) | 34 |

| Citrus sinensis | D | 25 | 12 (12) | 10 (10) | / (/) | 1 (1) | / (/) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | / (/) | / (/) | / (/) | / (/) | / (/) | / (/) | / |

| Capsicum annum | D | 39 | 30 (3) | 4 (/) | 1 (5) | 2 (1) | / (/) | 1 (/) | 1 (1) | / (/) | / (/) | / (/) | / (1) | / (/) | / (/) | 28 |

| Arabidopsis thaliana | D | 70 | 28 (28) | 15 (15) | 3 (3) | 3 (3) | 3 (3) | 4 (4) | 3 (3) | / (/) | / (/) | / (/) | 2 (2) | / (/) | 9 (9) | / |

| Amborella trichopoda | D | 52 | 36 (/) | 5 (/) | 1 (1) | 3 (/) | 1 (1) | 2 (/) | / (/) | / (/) | 2 (2) | / (/) | / (/) | / (/) | 2 (/) | 48 |

| Zea mays | M | 55 | 30 (1) | 7 (1) | 1 (1) | / (/) | 4 (3) | 5 (/) | 1 (1) | / (/) | 2 (2) | / (/) | / (/) | / (/) | 5 (/) | 46 |

| Spirodela polyrhiza | M | 29 | 11 (/) | 6 (/) | 1 (/) | / (/) | 2 (/) | 4 (1) | 1 (1) | / (/) | 1 (1) | / (/) | 1 (/) | / (/) | 2 (/) | 26 |

| Oryza sativa | M | 80 | 52 (5) | 18 (1) | 1 (/) | / (/) | 2 (/) | 5 (/) | 1 (1) | / (/) | / (/) | / (/) | 1 (/) | / (/) | / (/) | 73 |

| Picea abies | G | 104 | 73 (/) | 9 (/) | 1 (/) | 4 (/) | 2 (/) | 9 (/) | / (/) | 1 (/) | 4 (/) | / (/) | 1 (/) | / (/) | 1 (/) | 104 |

| Selaginella moellendorffii | L | 60 | 39 (40) | 1 (1) | 3 (3) | / (/) | 3 (2) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 3 (3) | / (/) | 1 (1) | 5 (5) | / |

| Marchantia polymorpha | MA | 34 | 2 (1) | 15 (/) | 3 (/) | / (/) | 1 (/) | 3 (/) | 2 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (/) | 2 (1) | 1 (/) | 2 (1) | 28 |

| Sphagnum fallax | B | 38 | / | 1 (/) | 6 (6) | 7 (/) | 1 (1) | 2 (1) | 4 (3) | 5 (/) | 2 (1) | 7 (/) | / (/) | / (/) | 3 (/) | 26 |

| Physcomitrella patens | B | 37 | / | 10 (10) | 3 (3) | 1 (1) | 3 (3) | 1 (1) | / (/) | 8 (8) | 4 (4) | 1 (1) | 5 (5) | 1 (1) | / (/) | / |

| Klebsormidium flaccidum | A (CHA) | 16 | 1 (/) | 3 (/) | 5 (/) | / (/) | / (/) | 1 (/) | 1 (/) | / (/) | / (/) | 2 (/) | 1 (/) | 1 (/) | 1 (/) | 16 |

| Micromonas pusilla CCMP1545 | A (CHL) | 14 | 2 (/) | 1 (/) | / (/) | 1 (/) | / (/) | 4 (/) | / (1) | / (/) | 2 (1) | / (/) | / (/) | 2 (/) | 2 (1) | 10 |

| Total | 1107 | 643 | 138 | 43 | 33 | 31 | 77 | 25 | 16 | 26 | 14 | 17 | 6 | 39 | 666 |

In brackets the number of GSTs per class before the assignment resulting from the reported analyses.

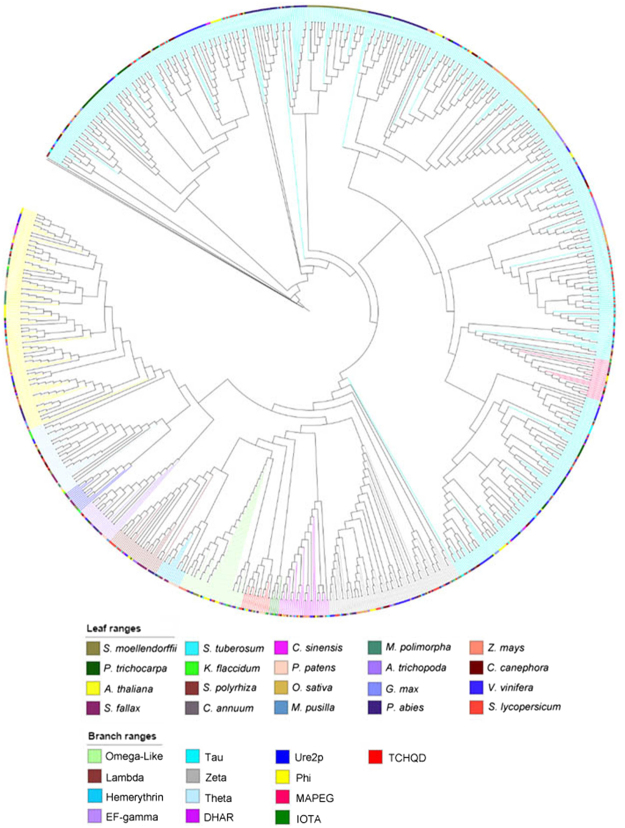

In order to associate the unclassified GSTs with specific classes, the collection was analyzed by a multiple protein sequence alignment using Muscle24 and an associated phylogenetic tree based on the maximum likelihood method25 (Fig. 1). The analysis defined the class association of the 666 unclassified GSTs (Table 2, numbers non in brackets), highlighting the presence of GST-Tau in Chlorophytes, Marchantiophytes and in Klebsormidiales, and confirming results from Liu et al., 2013, concerning their absence in Bryophytes.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree of all the 1107 GSTs. Colors of the leaves indicate the species, while those of the branches indicate the GST class, as reported in the corresponding legends.

Plant phylogeny depicted by GSTs

It can be noted (Fig. 1) that one GST (kfl00659_0030) from Klebsormidium flaccidum (Klebsormidiales) and two GSTs (213211, 49816) from Micromonas pusilla (Chlorophyta) resulted in the Tau class, as also summarized in Table 2.

In Liu et al., 2013, the authors suggested that GST-Tau genes were absent in algae and Bryophytes and served in Tracheophytes to colonize lands. Interestingly, our preliminary results show also that two GSTs (Mapoly0031s0032.1, Mapoly0118s0009.1) of Marchantia polymorpha (Marchantiophyta) belong to the Tau class.

In Table 3 the results of further analyses on the assignment of these 5 sequences to a specific GST class are shown. A BLASTp analysis26, versus all the other GST protein sequences here collected and versus the UNIPROTkb27 database, highlighted that the two Marchantia polymorpha (Mapoly0031s0032.1, Mapoly0118s0009.1) GST-Tau sequences are actually significantly similar to other members of the Tau class. This result is also valid for one of the two Micromonas pusilla (213211) sequences, although with lower significance (low score and identity values).

Table 3.

Summary of the two BLASTp results.

| GST Collection | UniProt | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Best hits | GST Class | Organism | Score | E-value | Best hits | GST Class | Organism | Score | E-value |

| Mapoly0031s0032.1 M. polymorpha | Mapoly0031s0032.1 M. polymorpha | ||||||||

| MA_944351p0010 | Tau | P.abies | 144 | 2.00E-44 | A0A176VUP3 | uncharacterized GST | M.polymorpha | 1295 | 1.00E-178 |

| MA_8564957p0010 | Tau | P.abies | 144 | 2.00E-44 | A0A0C9RTV3 | Transcribed RNA | W.nobilis | 357 | 2.30E-37 |

| MA_213889p0010 | Tau | P.abies | 138 | 5.00E-42 | L7S1R3 | Tau | P.tabuliformis | 328 | 4.60E-33 |

| Mapoly0118s0009.1 M. polymorpha | Mapoly0118s0009.1 M. polymorpha | ||||||||

| MA_34977p0010 | Tau | P.abies | 162 | 3.00E-51 | A0A176WNU4 | uncharacterized GST | M.polymorpha | 1140 | 7.40E-155 |

| MA_213889p0010 | Tau | P.abies | 157 | 3.00E-49 | A0A0C9RTV3 | Transcribed RNA | W.nobilis | 414 | 8.30E-46 |

| MA_160708p0010 | Tau | P.abies | 157 | 3.00E-49 | L7S309 | Tau | P.tabuliformis | 395 | 6.30E-43 |

| kfl00659_0030 K. flaccidum | kfl00659_0030 K. flaccidum | ||||||||

| Sphfalx0108s0054.1 | MAPEG | S.fallax | 36.6 | 4.00E-05 | K9TE82 | putative MAPEG | O.acuminata | 203 | 7.20E-17 |

| Sphfalx0011s0245.1 | MAPEG | S.fallax | 32.3 | 0.001 | L8N7J9 | MAPEG | P.biceps | 194 | 1.30E-15 |

| Sphfalx0077s0049.1 | MAPEG | S.fallax | 30.4 | 0.005 | A0A0M1JQ19 | putative MAPEG | Planktothricoides | 185 | 2.50E-14 |

| 213211 M. pusilla | 213211 M. pusilla | ||||||||

| AT1G78370.1 | Tau | A.thaliana | 79 | 4.00E-19 | C1MVD9 | putative OMEGA-like | M.pusilla | 1582 | 0 |

| AT1G78380.1 | Tau | A.thaliana | 78.2 | 7.00E-19 | C1EG60 | putative OMEGA-like | M.commoda | 1182 | 5.80E-160 |

| Cc01_g15350 | Tau | C.canephora | 78.2 | 8.00E-19 | A4SB04 | putative OMEGA-like | O.lucimarinus | 979 | 3.00E-129 |

| 49816 M. pusilla | 49816 M. pusilla | ||||||||

| PGSC0003DMP400034285 | MAPEG | S.tuberosum | 84.3 | 4.00E-23 | C1MGH6 | MAPEG | M.pusilla | 836 | 7.30E-112 |

| LOC_Os03g50130.1 | MAPEG | O.sativa | 83.2 | 9.00E-23 | C1EIA6 | putative MAPEG | M.commoda | 373 | 7.20E-42 |

| Solyc02g081430.2.1 | MAPEG | S.lycopersicum | 82.8 | 1.00E-22 | T1P743 | MAPEG | P.minimum | 317 | 1.50E-33 |

Two sequences from Marchantia polymorpha, one sequence from Klebsormidium flaccidum and two sequences from Micromonas pusilla were compared versus the GST protein sequences here collected and the UniProtkb database.

On the other hand, the sequence from Klebsormidium flaccidum (kfl00659_0030) and the remaining one from Micromonas pusilla (49816) showed a significant alignment with members of the Mapeg class (Table 3).

A domain search using the Interpro tool28 (Figure S1) showed that a GST-Tau from both the phylogenetic tree and the BLASTp analysis in Micromonas pusilla (213211) is actually an Omega-like GST (Figure S1).

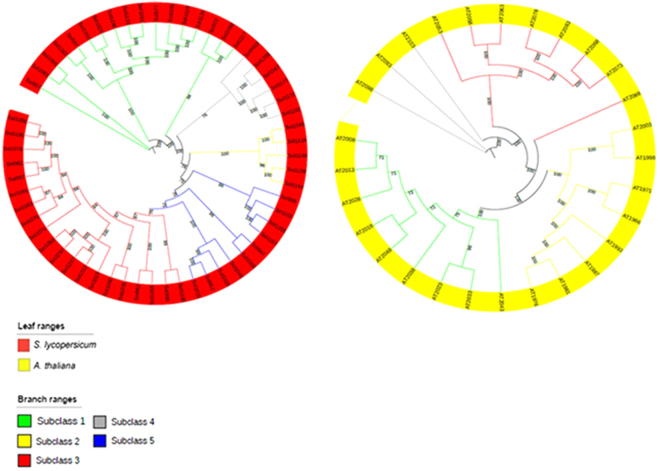

The presence of the GST-Tau class in plants from Lycophytae to higher plants in Liu et al., 2013, suggested that this class of proteins served the plants to colonize lands. The absence of Tau GSTs in all Bryophytes by a multiple sequence alignment and an associated phylogenetic tree of all the available GSTs from this division and the 1107 proteins from our collection (data not shown) was confirmed. This study highlighted the presence of two Tau GSTs in the Marchantiophytes division. This evidence supports the hypothesis of a paraphyletic origin for Bryophytes 29–31 (Fig. 2), in contrast with the general assumption that Bryophytes and Marchantiophytes are a separated clade from the one that gave rise to higher plants, and it also suggests that Marchantiophytes could indeed belong to the branching bringing to higher plants.

Figure 2.

(A) Phylogenetic tree currently proposed for green plants evolution. (B) Green plants evolutionary tree resulting from Cooper 2014. (C) Green plants evolutionary tree proposed herein.

Tau subclasses

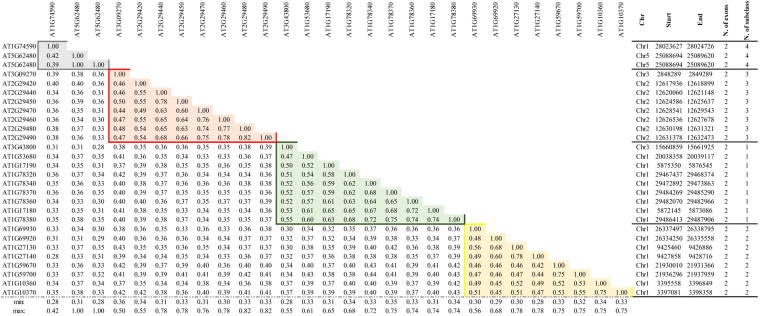

Data collected in this research clearly highlights the amplification of the GST-Tau class when compared to other GST classes8 (Fig. 1). In the work of Wagner32, the authors suggested that GST-Tau in Arabidopsis could be divided into three subclasses. In order to further investigate the expansion of the Tau class, a pairwise similarity of these proteins in Arabidopsis thaliana (Fig. 3) and in Solanum lycopersicum (Table S2), respectively, was carried out. The results highlight the presence of four subclasses in Arabidopsis (Fig. 3), one more than what Wagner32 described. Whereas five subclasses were identified in tomato (Table S2).

Figure 3.

Arabidopsis thaliana GST-Tau similarity matrix. Minimum and maximum values per column are indicated. The last columns indicate annotation of the gene in terms of chromosome (Chr), gene start (Start) and gene end (End), number of exons per gene (N. of exons) and the assignment to the identified subclass (Subclass number).

For further confirmation, two independent phylogenetic trees, one for Arabidopsis and one for tomato (Fig. 4), respectively, were drawn. The trees support our results from the pairwise similarity matrices. Successively, a phylogenetic tree (Fig. 5) with a reduced number of species, when compared to the one in Fig. 1, and including only Arabidopsis, S. lycopersicum, V. vinifera, three monocots (maize, rice and greater duckweed), S. moellendorffii and M. polymorpha was built. The latter two species are considered plants ancestors33. The figure shows the specific grouping into five subclasses, which are indicated from subclass 1 to 5, already detected in the species-specific analysis of tomato Tau GSTs. Subclass 5 does not include GSTs from Arabidopsis.

Figure 4.

Phylogenetic tree of GSTs from the class Tau in tomato (red) and Arabidopsis (yellow). The branches indicate the possible different subclasses, according to their color reported in the legend. Bootstrap values are also indicated.

Figure 5.

Phylogenetic tree of GSTs from class Tau of nine different species (as reported in the leaves legend). The branches indicate the possible different subclasses, according to the color reported in the corresponding legend. Bootstrap values are also indicated.

In the work of Dixon and Edwards34, all Arabidopsis GSTs were assigned with a specific role. Considering these functional assignments, subclass 1 includes nine Arabidopsis GSTs (AT3G43800.1, AT1G78370.1, AT1G78340.1, AT1G78380.1, AT1G78320.1, AT1G78360.1, AT1G17180.1, AT1G17190.1 and AT1G53680.1) that are reported to be expressed under abiotic and biotic stresses, since they bind herbicides (AT1G17190.1), 1-chloro-2,4-dinitrobenzene (AT1G78380.1, AT1G17180.1, AT1G53680.1), and salicylic (AT3G43800.1) or jasmonic acid (AT1G78370.1).

Subclass 2 includes eight Arabidopsis GSTs (AT1G59700.1, AT1G59670.1, AT1G69930.1, AT1G69920.1, AT1G27130.1, AT1G27140.1, AT1G10370.1 and AT1G10360.1) all reported to have a low capability of binding glutathione. These GSTs result to be abundant in the nucleus and also bind RNA.

Arabidopsis Tau GSTs preferentially expressed in root (AT3G09270.1, AT2G29480.1, AT2G29470.1, AT2G29490.1, AT2G29460.1, AT2G29440.1, AT2G29450.1 and AT2G29420.1) when the concentration of auxin and/or abscisic acid increase are all located in the subclass 3. Finally, the three GSTs (AT1G74590.1, AT5G62480.1 and AT5G62480.2), which result to be highly expressed in seed under stress condition, are all included in subclass 4.

Subclass 5 includes S. lycopersicum, V. vinifera and O. sativa members while Arabidopsis GSTs are all absent. This aspect was further investigated also considering Tau GSTs from B. oleracea, another Brassicaceae in which 28 Tau GSTs were also characterized35. The phylogenetic tree, including Tau GSTs from B. oleracea, V. vinifera, S. lycopersicum and A. thaliana (Figure S2), shows that GSTs from B. oleracea are not included in the subclass 5, and suggests that the absence of members of subclass 5 could be a common feature in Brassicaceae.

47 GSTs are included in subclass 5 (Fig. 5). LOC_Os12g02960.1, from O. sativa 36, and Solyc01g081250.2.1 and Solyc09g063150.2.1, from S. lycopersicum 37 result to be expressed under abiotic stress. Moreover, six V. vinifera GSTs in the subclass were characterized as each one is able to bind and transport flavonoids in the berry’s skin (VIT_201s0026g01340.1, VIT_207s0005g04890.1, VIT_215s0024g01630.1, VIT_215s0024g01650.1 and VIT_215s0107g00150.1, in the work of Costantini38, and VIT_215s0024g01540.1 in the work of Malacarne39). Interestingly, four V. vinifera GSTs (VIT_205s0051g00240.1, VIT_207s0005g04880.1, VIT_205s0049g01090.1, VIT_205s0049g01120.1)40 and one S. lycopersicum GST (Solyc01g081270.2.1)41 result to be expressed during the abscission. This could suggest a functional divergence of members of subclass 5 and a possible association with abscission mechanisms thus explain its absence in Brassicaceae in contrast with their presence in grapevine and tomato42.

GST-Tau from M. polymorpha (Marchantiophyta) and S. moellendorffii (Lycopodium) are all grouped in subclass 1. This may suggest that this Tau subclass could be the group of ancestral GSTs sequences.

Discussion

This analysis of 1107 GSTs from plants with sequenced genomes results in a wide phylogenetic tree providing insights on the organization of the different GST classes and highlights the presence of subclasses in the major classes currently described.

Beyond the assignment to specific GST classes for 666 unclassified proteins, the main aspect presented in this study is the possible confirmation of the paraphyletic origin of Bryophytes in contrast with the general assumption that Bryophytes and Marchantiophytes are a separated clade from the one that gave rise to higher plants. Moreover, the results indicate that Marchantiophytes could indeed belong to the branching bringing to higher plants.

The study includes the analysis of GST-Tau class, resulting in the discovery of the presence of at least 5 subclasses. The study tried to define the function of these subclasses. The results highlight the presence of a GST-Tau subclass including all the GST sequences from ancestor species, suggesting a primordial functionality for the members of this subclass. Finally a possible subclass, including genes associated with abscission, appears to be absent in Brassicaceae.

Materials and Methods

Genomic resources

GST protein sequences were searched by keyword. For Amborella trichopoda (v1.0), Selaginella moellendorffii (v1.0), Sphagnum fallax (v0.5), Spirodela polyrhiza (v2), Zea mays (Ensembl-18), Micromonas pusilla CCMP1545 (v3.0), Marchantia polymorpha (v3.1) and Populus trichocarpa (v3.0) the sequences were downloaded from Phytozome 1143 (https://phytozome.jgi.doe.gov/pz/portal.html); GSTs from Picea abies (v1.0) were downloaded from Congenie (http://congenie.org/); GSTs Klebsormidium flaccidum were downloaded from CGA (http://genome.microbedb.jp/Klebsormidium) while the ones from Oryza sativa were downloaded from TIGR44 (http://rice.plantbiology.msu.edu/); GST sequences from Coffea canephora were obtained searching in the Coffee genome Hub database45 (http://coffee-genome.org/coffeacanephora); Glicine max’s GSTs protein sequence were downloaded from Gramene46 (http://www.gramene.org/); GST sequences of Solanum lycopersicum (iTAG2.4) and Capsicum annuum (v1.55) were downloaded from SGN47 (https://solgenomics.net/), while the ones of Solanum tuberosum (PGSC_DM_v_3.4) were obtained from Spud db48 (http://solanaceae.plantbiology.msu.edu/); GST sequences of Arabidopsis thaliana were downloaded from TAIR10 (https://www.arabidopsis.org/). Vitis vinifera GST sequences (v2) were obtained from Cribi (http://genomes.cribi.unipd.it/grape/). GST sequences of Physcomitrella patens were obtained from19 and the ones from Citrus sinensis were obtained from9.

Phylogenetic Analysis

Multiple alignments were obtained using Muscle24 with default parameter (gap open penalty -2,9, gap extension penalty 0). The Phylogenetic tree was built with RaxML25, using the maximum likelihood method, considering PROTCATBLOSUM62 as similarity matrix with the Bootstrap option. Finally the editing tool iTOL v349 was used.

In order to obtain the pairwise distances of GST-Tau protein sequences we used “protdist” from PHYLIP, using the JTT matrix50. All the alignments, trees and matrices were built using shorter identifiers to indicate each gene. The conversion table between the original gene IDs and the code here used is reported in the supplemental Table 1.

Class assignation for ambiguous cases

In order to understand the class of the three putative GST-Tau of the two algae and the class of the two putative Tau GSTs of the Marchantiophyta we performed a BLASTp26 with default parameters versus the entire GSTs collection here considered. A Uniprot BLASTp was also performed using default parameters versus UNIPROTkb27. The M. pusilla putative GST-Tau was further investigated by an InterProScan28 analysis with default parameters.

Electronic supplementary material

Author Contributions

F.M.: performed all the analyses and wrote the manuscript. C.C.: supervised the analyses and contributed to manuscript. M.L.C.: planned, organized and supervised the entire effort and wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the organization and the writing of the manuscript and approved the final version.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-017-14316-w.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Dixon DP, Cummins L, Cole DJ, Edwards R. Glutathione-mediated detoxification systems in plants. Current opinion in plant biology. 1998;1:258–266. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5266(98)80114-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Edwards R, Dixon DP, Walbot V. Plant glutathione S-transferases: enzymes with multiple functions in sickness and in health. Trends in plant science. 2000;5:193–198. doi: 10.1016/S1360-1385(00)01601-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frear DS, Swanson HR. Biosynthesis of S-(4-ethylamino-6-isopropylamino- 2-s-triazino) glutathione: Partial purification and properties of a glutathione S-transferase from corn. Phytochemistry. 1970;9:2123–2132. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(00)85377-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roxas VP, Lodhi SA, Garrett DK, Mahan JR, Allen RD. Stress tolerance in transgenic tobacco seedlings that overexpress glutathione S-transferase/glutathione peroxidase. Plant & cell physiology. 2000;41:1229–1234. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcd051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marrs KA, Alfenito MR, Lloyd AM, Walbot V. A glutathione S-transferase involved in vacuolar transfer encoded by the maize gene Bronze-2. Nature. 1995;375:397–400. doi: 10.1038/375397a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mueller LA, Goodman CD, Silady RA, Walbot V. AN9, a petunia glutathione S-transferase required for anthocyanin sequestration, is a flavonoid-binding protein. Plant physiology. 2000;123:1561–1570. doi: 10.1104/pp.123.4.1561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sun Y, Li H, Huang JR. Arabidopsis TT19 functions as a carrier to transport anthocyanin from the cytosol to tonoplasts. Molecular plant. 2012;5:387–400. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssr110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu Y, et al. Comparative Transcriptome Analysis of White and Purple Potato to Identify Genes Involved in Anthocyanin Biosynthesis. PloS one. 2015;10:e0129148. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Licciardello C, et al. Characterization of the glutathione S-transferase gene family through ESTs and expression analyses within common and pigmented cultivars of Citrus sinensis (L.) Osbeck. BMC plant biology. 2014;14:39. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-14-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alfenito MR, et al. Functional complementation of anthocyanin sequestration in the vacuole by widely divergent glutathione S-transferases. The Plant cell. 1998;10:1135–1149. doi: 10.1105/tpc.10.7.1135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marrs KA, Walbot V. Expression and RNA splicing of the maize glutathione S-transferase Bronze2 gene is regulated by cadmium and other stresses. Plant physiology. 1997;113:93–102. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.1.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marrs KA. THE FUNCTIONS AND REGULATION OF GLUTATHIONE S-TRANSFERASES IN PLANTS. Annual review of plant physiology and plant molecular biology. 1996;47:127–158. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.47.1.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hahn K, Strittmatter G. Pathogen-defence gene prp1-1 from potato encodes an auxin-responsive glutathione S-transferase. European journal of biochemistry / FEBS. 1994;226:619–626. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.tb20088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Droog F. Plant Glutathione S-Transferases, a Tale of Theta and Tau. Journal of Plant Growth Regulation. 1997;16:95–107. doi: 10.1007/PL00006984. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Droog F, Hooykaas P, Van Der Zaal BJ. 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic Acid and Related Chlorinated Compounds Inhibit Two Auxin-Regulated Type-III Tobacco Glutathione S-Transferases. Plant physiology. 1995;107:1139–1146. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.4.1139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Edwards R, Dixon DP. Plant glutathione transferases. Methods in enzymology. 2005;401:169–186. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)01011-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dixon DP, Davis BG, Edwards R. Functional divergence in the glutathione transferase superfamily in plants. Identification of two classes with putative functions in redox homeostasis in Arabidopsis thaliana. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2002;277:30859–30869. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202919200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Loyall L, Uchida K, Braun S, Furuya M, Frohnmeyer H. Glutathione and a UV light-induced glutathione S-transferase are involved in signaling to chalcone synthase in cell cultures. The Plant cell. 2000;12:1939–1950. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.10.1939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu YJ, Han XM, Ren LL, Yang HL, Zeng QY. Functional divergence of the glutathione S-transferase supergene family in Physcomitrella patens reveals complex patterns of large gene family evolution in land plants. Plant physiology. 2013;161:773–786. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.205815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim YJ, Lee OR, Lee S, Kim KT, Yang DC. Isolation and Characterization of a Theta Glutathione S-transferase Gene from Panax ginseng Meyer. Journal of ginseng research. 2012;36:449–460. doi: 10.5142/jgr.2012.36.4.449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jakobsson PJ, Morgenstern R, Mancini J, Ford-Hutchinson A, Persson B. Common structural features of MAPEG–a widespread superfamily of membrane associated proteins with highly divergent functions in eicosanoid and glutathione metabolism. Protein science: a publication of the Protein Society. 1999;8:689–692. doi: 10.1110/ps.8.3.689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bailly X, Vanin S, Chabasse C, Mizuguchi K, Vinogradov SN. A phylogenomic profile of hemerythrins, the nonheme diiron binding respiratory proteins. BMC evolutionary biology. 2008;8:244. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-8-244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Soranzo N, Sari Gorla M, Mizzi L, De Toma G, Frova C. Organisation and structural evolution of the rice glutathione S-transferase gene family. Molecular genetics and genomics: MGG. 2004;271:511–521. doi: 10.1007/s00438-004-1006-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Edgar RC. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic acids research. 2004;32:1792–1797. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stamatakis A. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 2014;30:1312–1313. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. Journal of molecular biology. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Apweiler R, et al. UniProt: the universal protein knowledgebase. Nucleic acids research. 2004;32:D115–D119. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hunter S, et al. InterPro: the integrative protein signature database. Nucleic acids research. 2009;37:D211–D215. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Qiu Y-L, et al. A nonflowering land plant phylogeny inferred from nucleotide sequences of seven chloroplast, mitochondrial, and nuclear genes. International Journal of Plant Sciences. 2007;168:691–708. doi: 10.1086/513474. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qiu Y-L, et al. The deepest divergences in land plants inferred from phylogenomic evidence. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2006;103:15511–15516. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603335103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cooper ED. Overly simplistic substitution models obscure green plant phylogeny. Trends in plant science. 2014;19:576–582. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2014.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wagner U, Edwards R, Dixon DP, Mauch F. Probing the diversity of the Arabidopsis glutathione S-transferase gene family. Plant molecular biology. 2002;49:515–532. doi: 10.1023/A:1015557300450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Anderberg HI, Kjellbom P, Johanson U. Annotation of Selaginella moellendorffii Major Intrinsic Proteins and the Evolution of the Protein Family in Terrestrial Plants. Frontiers in Plant Science. 2012;3:33. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2012.00033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dixon, D. P. & Edwards, R. Glutathione transferases. The Arabidopsis Book, e0131 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Vijayakumar H, et al. Glutathione Transferases Superfamily: Cold-Inducible Expression of Distinct GST Genes in Brassica oleracea. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2016;17:1211. doi: 10.3390/ijms17081211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fu, X., Li, C., Zhou, X., Liu, S. & Wu, F. Physiological response and sulfur metabolism of the V. dahliae-infected tomato plants in tomato/potato onion companion cropping. Scientific reports6 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Bodanapu, R., Gupta, S. K., Basha, P. O. & Sakthivel, K. Nitric oxide overproduction in tomato shr mutant shifts metabolic profiles and suppresses fruit growth and ripening. Frontiers in Plant Science7 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Costantini L, et al. New candidate genes for the fine regulation of the colour of grapes. Journal of experimental botany. 2015;66:4427–4440. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erv159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Malacarne, G. et al. Regulation of flavonol content and composition in (Syrah × Pinot Noir) mature grapes: integration of transcriptional profiling and metabolic quantitative trait locus analyses. Journal of experimental botany, erv243 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Domingos S, et al. Shared and divergent pathways for flower abscission are triggered by gibberellic acid and carbon starvation in seedless Vitis vinifera L. BMC plant biology. 2016;16:38. doi: 10.1186/s12870-016-0722-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nakano T, Fujisawa M, Shima Y, Ito Y. Expression profiling of tomato pre-abscission pedicels provides insights into abscission zone properties including competence to respond to abscission signals. BMC plant biology. 2013;13:40. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-13-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Patterson SE. Cutting loose. Abscission and dehiscence in Arabidopsis. Plant physiology. 2001;126:494–500. doi: 10.1104/pp.126.2.494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Goodstein DM, et al. Phytozome: a comparative platform for green plant genomics. Nucleic acids research. 2012;40:D1178–1186. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ouyang S, et al. The TIGR Rice Genome Annotation Resource: improvements and new features. Nucleic acids research. 2007;35:D883–887. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dereeper A, et al. The coffee genome hub: a resource for coffee genomes. Nucleic acids research. 2015;43:D1028–1035. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ware D, et al. Gramene: a resource for comparative grass genomics. Nucleic acids research. 2002;30:103–105. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mueller LA, et al. TheSOL Genomics Network: a comparative resource for Solanaceae biology and beyond. Plant physiology. 2005;138:1310–1317. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.060707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hirsch, C. D. et al. Spud DB: A Resource for Mining Sequences, Genotypes, and Phenotypes to Accelerate Potato Breeding. The Plant Genome7, 10.3835/plantgenome2013.12.0042 (2014).

- 49.Letunic I, Bork P. Interactive tree of life (iTOL)v3: an online tool for the display and annotation of phylogenetic and other trees. Nucleic acids research. 2016;44:W242–w245. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Felsenstein, J. PHYLIP: Phylogenetic inference program, version 3.6. University of Washington, Seattle (2005).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.