Abstract

Background:

Majority of the patients presenting to emergency department (ED) have pain. ED oligoanalgesia remains a challenge.

Aims:

This study aims to study the effect of implementing a protocol-based pain management in the ED on (1) time to analgesia and (2) adequacy of analgesia obtained.

Settings and Design:

Cross-sectional study in the ED.

Methods:

Patients aged 18–65 years of age with pain of numeric rating scale (NRS) ≥4 were included. A series of 100 patients presenting before introduction of the protocol-based pain management were grouped “pre-protocol,” and managed as per existing practice. Following this, a protocol for management of all patients presenting to ED with pain was implemented. Another series of 100 were grouped as “post-protocol” and managed as per the new pain management protocol. The data of patients from both the groups were collected and analyzed.

Statistical Analysis Used:

Descriptive statistical tests such as percentage, mean and standard deviation and inferential statistical tests such as Pearson coefficient, Student's t-test were applied. Differences were interpreted as significant when P < 0.05.

Results:

Mean time to administer analgesic was significantly lesser in the postprotocol group (preprotocol 20.30 min vs. postprotocol 13.05 min; P < 0.001). There was significant difference in the pain relief achieved (change in NRS) between the two groups, with greater pain relief achieved in the postprotocol group (preprotocol group 4.6800 vs. postprotocol group 5.3600; P < 0.001). Patients' rating of pain relief (assessed on E5 scale) was significantly higher in the postprotocol group (preprotocol 3.91 vs. postprotocol 4.27; P = 0.001). Patients' satisfaction (North American Spine Society scale) with the overall treatment was also compared and found to be significantly higher in postprotocol group (mean: preprotocol 1.59 vs. postprotocol 1.39; P = 0.008).

Conclusion:

Protocol-based pain management provided timely and superior pain relief.

Keywords: Emergency department, numeric rating scale, oligoanalgesia, opioids, pain, patient satisfaction, protocol

INTRODUCTION

Pain-related complaints are estimated to represent as many as 70% of presenting concerns for patients in the emergency department (ED) setting.[1] It is regarded as the fifth vital sign.[2] Unrelieved pain is associated with potentially negative physiologic outcomes, including increase in heart rate, blood pressure, respiratory rate and myocardial oxygen demand, hypercoagulability and immune function impairment.

Addressing patient's pain is one of the most important contributions ED providers can make. It leads to earlier mobilization, shortened hospital stay, reduced hospital costs and affects patient satisfaction.[3]

Despite extensive research and guidelines on pain management, oligoanalgesia remains a challenge in most EDs. Recommendations for better pain management include improved acknowledgment, assessment, and documentation of pain, monitored outcome measures, formalized education and training, and implementation of pain management protocols.

Emergency care system is in its infancy in India,[4] and pain is not recognized as an important vital sign due to lack of awareness regarding it. There is a paucity of literature addressing the management of pain in EDs in India and effectiveness of protocol-based pain management in ED.

Hence, we conducted this study to test the hypothesis that implementation of a standard protocol for pain management in the ED would reduce the time taken to deliver analgesia and provide more effective pain relief. For this, we assessed the (1) time to analgesia and (2) change in numeric rating scale (NRS) as the primary outcome. In addition, we attempted to assess the patients' satisfaction with the pain relief obtained using North American Spine Society (NASS) scale and E5 scale (secondary outcome).

METHODS

This was a cross-sectional study among the patients who presented to the ED of a tertiary care hospital in India. The study was done over a period of 2 months. Consecutive sampling technique was used.

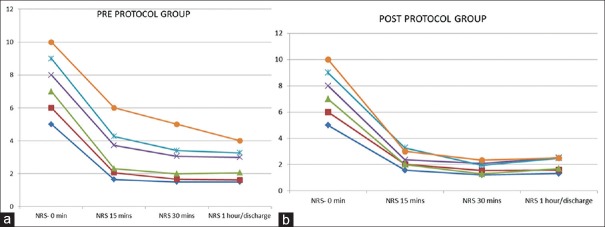

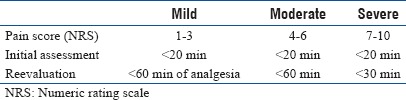

Patients presenting to our ED with complaints of pain were evaluated with NRS[5] [Figure 1] by the researchers.

Figure 1.

Numeric rating scale

NRS was selected as it has higher compliance rates, better responsiveness and ease of use, and good applicability relative to visual analog scale and verbal rating scale.[6] On the basis of NRS, their pain was classified as mild (NRS 1–3), moderate (NRS 4–6), and severe (NRS 7–10). Patients with NRS ≥4 at presentation in the age group of 18–65 years were included in the study. Patients with altered level of consciousness, pregnant women, and those who had received analgesic 30 min before presentation were excluded. Patients with a history of chronic pain and those with known drug seeking behavior were excluded as well. Analgesia was administered as per treating physician's orders. Using the pro forma [Appendix 1], researchers reassessed the pain using NRS. A series of 100 consecutive patients were taken and their demographics, site of pain, NRS at presentation, time to analgesic administration, analgesic (s)/procedures used to relieve pain were noted. Following the delivery of analgesia, pain NRS at 15 min, 30 min, and at 1 hour/discharge from ED were noted along with E5 scale [Appendix Table 1] and patient satisfaction index-NASS scale [Appendix Table 2]. This series of patients were grouped as “pre-protocol group.”

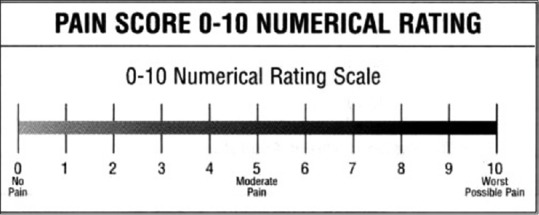

Following this, the Department of Emergency Medicine introduced a protocol for management of acute pain in the ED [Appendix 2]. For the implementation of protocol, all the ED doctors attending to patients in the ED were trained in using protocol for various situations and the contraindications were explained. They were also educated regarding the assessment and reassessment of pain. Pain medications orders were given by these doctors. After the introduction of the protocol, a series of 100 consecutive patients were evaluated and the researchers recorded data using the pro forma. This series of patients were grouped as “post-protocol group.” The data collected was analyzed [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of methodology of the study

ETHICS: Institutional Ethics Committee clearance was obtained for the study.

Statistics

Based on the patient statistics of our ED, the incidence of pain among patients was 50%, with 10% allowable error and α = 5%, sample size to be included in each group was 100. The patients were grouped in the “pre-protocol group” and “post-protocol group” and compared. Data were entered in Microsoft Excel 2010 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 21.0. (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistical tests such as percentage, mean and standard deviation were applied. Inferential statistical tests such as Pearson coefficient, Student's t-test were applied. Differences were interpreted as significant when P < 0.05.

RESULTS

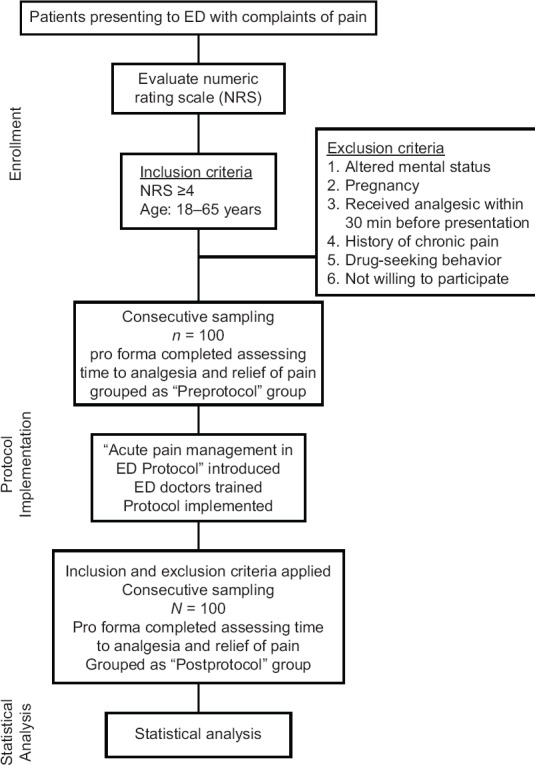

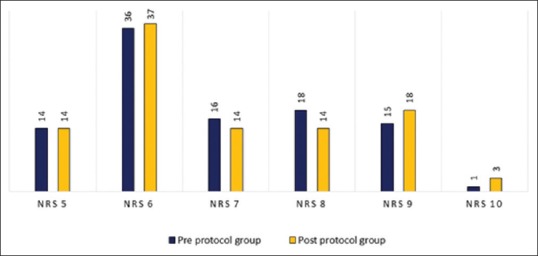

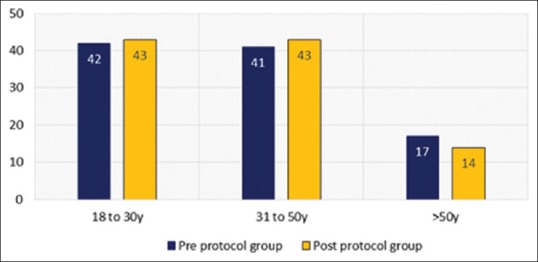

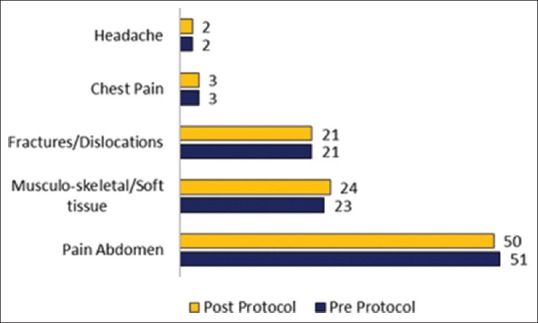

The preprotocol group and the postprotocol group were similar in terms of age, gender distribution, type and severity of pain at presentation [Figures 3–6].

Figure 3.

Gender distribution of study population

Figure 6.

Pain numeric rating scale at presentation in the study population

Figure 4.

Age distribution of the study population

Figure 5.

Distribution of site of pain in the study population

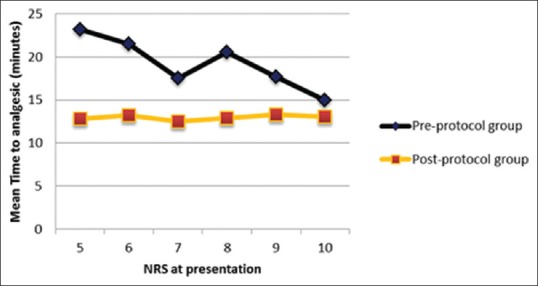

The mean time taken to give the medications/nerve block for pain relief was significantly different in the two groups. (preprotocol group 20.30 min vs. postprotocol group 13.05 min; P < 0.001) [Figure 7].

Figure 7.

Comparison of time to analgesic between the preprotocol group and postprotocol group

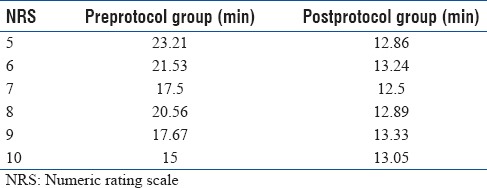

On subgroup analysis, patients presenting with moderate pain (NRS 4–6) received analgesia earlier in the postprotocol group (preprotocol group 22.00 min vs. postprotocol 13.14 min; P < 0.001). Subgroup analysis among patients presenting with severe pain (NRS 7–10) also revealed that analgesia was delivered earlier in the postprotocol group (preprotocol group 18.60 min vs. postprotocol 12.96 min; P < 0.001) [Table 1].

Table 1.

Time to analgesia at various numeric rating scale in pre- and post-protocol group

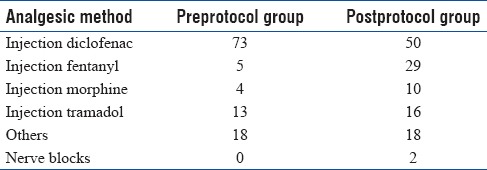

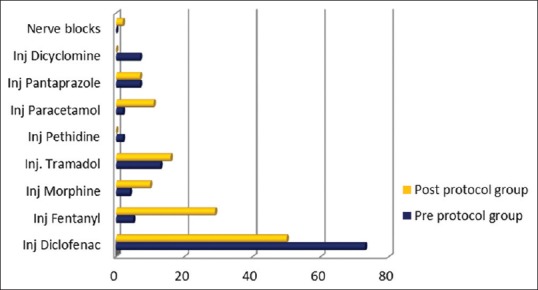

Among the analgesics used, injection diclofenac was most common, but the use was significantly reduced in the postprotocol group [Table 2]. The use of opioid analgesic was more in the postprotocol group, and nerve blocks were included as per the protocol. In the preprotocol group, 86 patients were administered a single drug for analgesia, whereas in the postprotocol group, 73 patients received single drug analgesia and comparatively more drug combinations were used to achieve pain relief [Figure 8].

Table 2.

Choice of analgesia in pre- and post-protocol group

Figure 8.

Comparison of analgesia used in the preprotocol group and postprotocol group

It is to be noted that, despite inadequate relief of pain in the preprotocol group, rescue medications were not used by treating physicians.

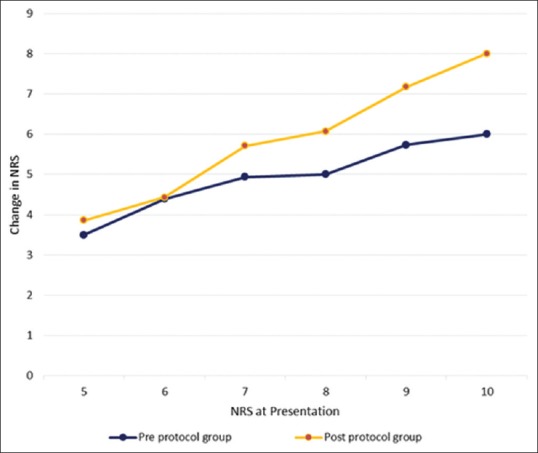

There was a significant difference in the pain relief achieved at 1 h/discharge (estimated as change in NRS) between the two groups, with greater pain relief achieved in the postprotocol group. (preprotocol group 4.6800 vs. postprotocol group 5.3600; P < 0.001) [Figure 9].

Figure 9.

Comparison of change in the numeric rating scale between the preprotocol group and postprotocol group at different initial numeric rating scale at presentation

Subgroup analysis of the patients with moderate pain at presentation showed that there was no significant difference in the pain relief achieved at 1 h/discharge (estimated as change in NRS) (preprotocol group 4.140 vs. postprotocol group 4.275; P = 0.291).

Subgroup analysis of the patients with severe pain at presentation showed that there was a statistically significant difference in the pain relief achieved at 1 h/discharge (estimated as change in NRS) (preprotocol group 5.220 vs. postprotocol group 6.490; P < 0.001).

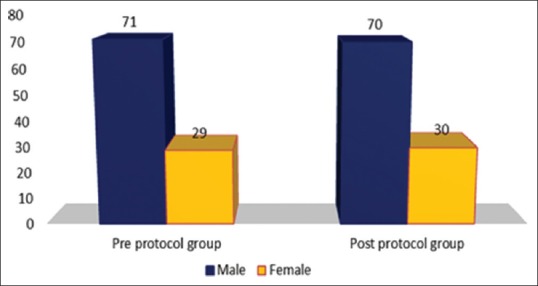

Faster and greater pain relief was noted in the postprotocol group [Figure 10a and b]. In either group, there was not much change in the NRS at 1 h/discharge versus the NRS at 30 min, suggesting that if adequate analgesia is not reached within 30 min, we may need to reevaluate and consider using another analgesic.

Figure 10.

(a) Change in the numeric rating scale at different initial numeric rating scale at various time intervals between the preprotocol group. (b) Change in the numeric rating scale at different initial numeric rating scale at various time intervals between the postprotocol group

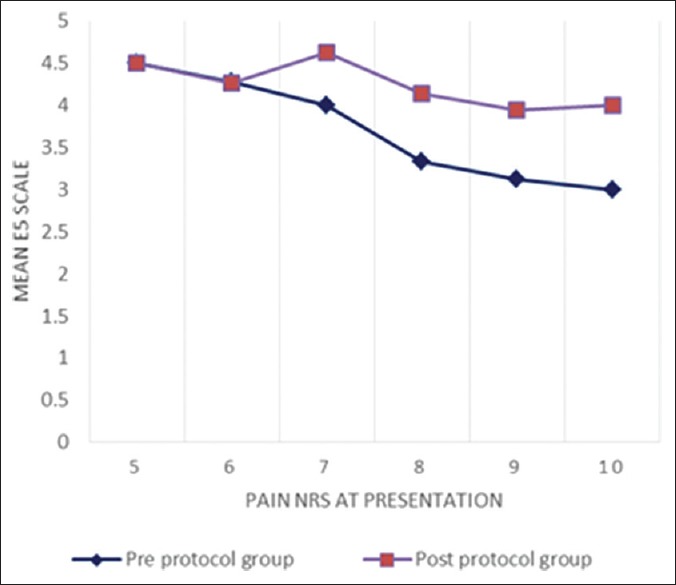

The patients' rating of E5 scale was significantly higher in the postprotocol group (preprotocol 3.91 vs. postprotocol 4.27; P = 0.001) [Figure 11].

Figure 11.

Comparison of E5 scale between the preprotocol group and postprotocol group at different initial numeric rating scale

The patients' satisfaction with the overall treatment (NASS scale) was also compared and found to be significantly higher in postprotocol group (mean: preprotocol 1.59 vs. postprotocol 1.39; P = 0.008).

DISCUSSION

We found that the mean time taken among the preprotocol group was 20.30 min. For a patient with pain of NRS ≥4, efforts should be made to shorten this wait. A multicenter study done by Todd et al.[7] also found that pain in the ED continues to be poorly treated with lengthy delays between ED arrival and analgesic delivery. The reason for the delay in the ED continues to be due to inattention to pain as a vital part of the assessment and lack of reassessment of pain.

The mean time interval to administer analgesic was significantly shorter in the postprotocol group.

In subgroup analysis, in patients presenting with moderate pain (NRS 4–6), analgesia was delivered earlier in postprotocol group. Subgroup analysis among patients presenting with severe pain (NRS 7–10) also revealed that analgesia was delivered earlier in the postprotocol group.

Patrick et al.[8] found that after implementation of a pain management policy, the proportion of patients with severe pain receiving analgesics within 30 min actually declined in their study. They attributed this paradoxical result possibly to the increased patient volume during “after” period.

A study done by Fosnocht and Swanson[9] found that implementation of a triage pain protocol in the ED decreased time to pain medication administration from 76 to 40 min. This finding was consistent with finding in our study that protocol decreases time taken to deliver analgesia.

Fosnocht and Swanson[9] also found that the number of patients who received pain medication increased after implementation of triage pain protocol. This study also supports our finding of the requirement of protocol-based pain management in ED as a solution to the problem of ED oligoanalgesia.

Similarly, the assessment of pain relief done through NRS scale showed that the postprotocol group had greater pain relief (estimated as difference between initial NRS and NRS at 1 hour/discharge from ED).

Subgroup analysis of the patients with moderate pain at presentation showed that there was no significant difference in the pain relief achieved at 1 h/discharge.

Subgroup analysis of the patients with severe pain at presentation showed that there was a statistically significant increase in the pain relief achieved at 1 h/discharge.

This can be explained by the increased and appropriate use of opioid analgesics in patients presenting with severe pain (higher initial NRS) in the postprotocol group, which was lacking in the preprotocol group.

A study done by Bijur et al.[10] also found that recommendations for administration of intravenous (IV) opioids in the treatment of severe pain in the ED were not being followed.

There is a hesitation to use opioid analgesics, largely due to misconceptions regarding adverse effects, likelihood of opioid dependency, lack of experience, and unavailability of opioids in ED.

All guidelines suggest appropriate opioid analgesics to be used for severe pain (NRS 7–10), and application of the protocol helped us to improve our practice in pain management. Protocol emphasized the use of multimodal analgesia, where we simultaneously administer ≥2 analgesic agents with different mechanisms of action. Combination therapy using drugs with distinct mechanisms of action may add analgesia or have a synergistic effect and allow for better analgesia with the use of lower doses of a given medication. Nerve block technique used as part of multimodal analgesia has shown encouraging results.

It is to be noted that, despite inadequate relief of pain in the preprotocol group, rescue medications were not used by treating physicians. This shows a lack of importance given to reassessment of pain by treating physicians, and this is an area which needs improvement in EDs.

The patients' rating of E5 scale was significantly higher in the postprotocol group. This difference in patients' own rating of pain relief on E5 scale was more pronounced at higher initial NRS.

The patients' satisfaction with the overall treatment (NASS scale) was found to be significantly higher in postprotocol group. Patient satisfaction depends on a number of variables, and management of pain in a timely manner is an important contributing factor.

Limitations

Training of nurses to assess pain using NRS and satisfaction of pain relief using various scales was not done. By training nurses, we can further shorten time to the assessment of pain, and therefore, time to analgesia will further decrease. Furthermore, nurses will play a pivotal role in reassessment of pain in ED.

Our center has high input of surgical and trauma emergencies. This is the reason why our study showed a smaller proportion of medical emergencies. Therefore, further studies including a larger proportion of painful medical conditions such as myocardial infarctions are warranted.

Future directions

There is inattention toward pain in ED setting due to lack of good emergency care system in India. There is also deficiency of training among ED caregivers regarding pain management. Hence, implementation of pain assessment and management protocol is important among the emergency caregivers. We also need to train nurses and EMS caregivers in implementing pain protocols in ER so that we can tackle this issue of oligoanalgesia at all tiers of emergency care system.

CONCLUSIONS

Protocol-based pain management shortened the time taken to administer analgesics and provided more effective pain relief.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

APPENDIX 1: PAIN QUESTIONNAIRE

OP/IP Number: .................................... Age: .......................................... Sex: .....................

DIAGNOSIS:

......................................

HISTORY

Chief Complaints:

Duration of pain:

Type of pain:

Site of pain:

Pain Numeric rating scale:

Medical history:

ON EXAMINATION

Blood Pressure: ........................... Respiratory Rate: ................................ Pulse Rate: .......................

spO2:

Systemic Examination Findings:

INVESTIGATIONS:

MEDICATIONS/PROCEDURE DONE FOR PAIN RELIEF:

Time to analgesia from arrival to EMD:

POSTMEDICATION/PROCEDURE:

At the time of disposition from red zone:

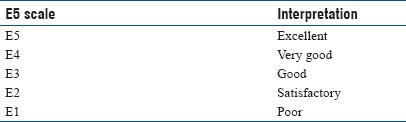

Appendix Table 1.

E5 scale

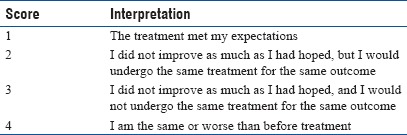

Appendix Table 2.

Patient satisfaction index – North American Spine Society scale

APPENDIX 2: PROTOCOL FOR MANAGEMENT OF ACUTE PAIN IN THE EMERGENCY DEPARTMENT

PAIN ABDOMEN

Severe: Injection morphine 2.5.5 mg IV. initial dose.

If contraindicated: Injection Fentanyl 25.50 mcg IV.

Moderate: Injection paracetamol 1 g IV ± injection tramadol 100 mg IM/slow IV.

RENAL/URETERIC COLIC

Severe

-

Injection morphine 2.5.5 mg IV. initial dose

If contraindicated: Injection Fentanyl 25.50 mcg IV

and

-

Injection diclofenac 75 mg IM.

Moderate: Injection diclofenac 75 mg IM ± injection tramadol 100 mg IM/slow IV.

FRACTURES AND DISLOCATIONS

Nerve blocks (wherever applicable) with

Severe: Injection morphine 2.5-5 mg IV- initial dose.

If contraindications: Injection fentanyl 25-50 mcg IV.

Moderate: Injection diclofenac 75 mg IM ± injection tramadol 100 mg IM/slow IV.

SOFT TISSUE/ACUTE MUSCULOSKELETAL PAIN

Severe: Injection tramadol 100 mg IM/slow IV and injection paracetamol 1 g IV.

Moderate: Injection paracetamol 1 g IV and/or injection diclofenac 75 mg IM.

BACK PAIN

Severe: Injection tramadol 100 mg IM/slow IV and injection paracetamol 1 g IV.

Moderate: Injection paracetamol 1 g IV ± injection Diclofenac 75 mg IM.

DENTAL PAIN

Severe: Morphine 2.5.5 mg IV. initial dose.

If contraindicated: Injection fentanyl 25.50 mcg IV ± injection diclofenac 75 mg IM.

Moderate: Injection tramadol 100 mg IM/slow IV + injection paracetamol 1 g or injection diclofenac 75 mg IM.

CARDIAC PAIN

Aspirin 325 mg oral

Isosorbide dinitrate 5 mg (contraindicated in right wall MI, Systolic BP<90 mm Hg or recent use of phosphodiesterase – 5 inhibitor).

Injection morphine 2.5-5 mg IV- initial dose. Titrate: increase 2.5-5 mg every 5-10 min.

If contraindicated (Bradycardia, inferior wall MI, Hypotension): Injection fentanyl 25-50 mcg IV/Pethidine 50 mg IV.

BURNS

Severe: Injection morphine 2.5-5 mg IV- initial dose.

If contraindicated: Injection fentanyl 25-50 mcg IV.

Moderate: Injection paracetamol 1 g IV ± injection tramadol 100 mg IM/slow IV.

MIGRAINE HEADACHE Injection paracetamol 1 g IV/injection tramadol 100 mg IM/injection diclofenac 75 mg IM/injection metaclopramide10 mg IV/injection Haloperidol 5 mg IV.

CONTRAINDICATIONS TO MORPHINE: Hypersensitivity, respiratory depression, acute severe asthma/hypercarbia, paralytic ileus, head injury, hypotension, pancreatic/biliary disease.

CONTRAINDICATIONS TO DICLOFENAC: Hypersensitivity, pregnancy 3rd trimester, peptic ulcer disease, GI bleed, IBD, Severe liver insufficiency, renal disease.

REFERENCES

- 1.Marx J, Hockberger R, Walls R. Rosen's Emergency Medicine-Concepts and Clinical Practice. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organisations. Standards, Intents, Examples and Scoring Questions for Pain Assessment and Management Oakbrook Terrace, Illinois. 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Downey LV, Zun LS. Pain management in the emergency department and its relationship to patient satisfaction. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2010;3:326–30. doi: 10.4103/0974-2700.70749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Das AK, Gupta SB, Joshi SR, Aggarwal P, Murmu LR, Bhoi S, et al. White paper on academic emergency medicine in India: INDO-US Joint Working Group (JWG) J Assoc Physicians India. 2008;56:789–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCaffery M, Beebe A. Pain: Clinical Manual for Nursing Practice. Baltimore: V.V. Mosby Company; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hjermstad MJ, Fayers PM, Haugen DF, Caraceni A, Hanks GW, Loge JH, et al. Studies comparing Numerical Rating Scales, Verbal Rating Scales, and Visual Analogue Scales for assessment of pain intensity in adults: A systematic literature review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;41:1073–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Todd KH, Ducharme J, Choiniere M, Crandall CS, Fosnocht DE, Homel P, et al. Pain in the emergency department: Results of the pain and emergency medicine initiative (PEMI) multicenter study. J Pain. 2007;8:460–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2006.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patrick PA, Rosenthal BM, Iezzi CA, Brand DA. Timely pain management in the emergency department. J Emerg Med. 2015;48:267–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2014.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fosnocht DE, Swanson ER. Use of a triage pain protocol in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2007;25:791–3. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2006.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bijur PE, Esses D, Chang AK, Gallagher EJ. Dosing and titration of intravenous opioid analgesics administered to ED patients in acute severe pain. Am J Emerg Med. 2012;30:1241–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2011.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]