Abstract

Extrapulmonary tuberculosis (EPTB) is frequently a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. It is a common opportunistic infection in people living with HIV/AIDS and other immunocompromised states such as diabetes mellitus and malnutrition. There is a paucity of data from clinical trials in EPTB and most of the information regarding diagnosis and management is extrapolated from pulmonary TB. Further, there are no formal national or international guidelines on EPTB. To address these concerns, Indian EPTB guidelines were developed under the auspices of Central TB Division and Directorate of Health Services, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. The objective was to provide guidance on uniform, evidence-informed practices for suspecting, diagnosing and managing EPTB at all levels of healthcare delivery. The guidelines describe agreed principles relevant to 10 key areas of EPTB which are complementary to the existing country standards of TB care and technical operational guidelines for pulmonary TB. These guidelines provide recommendations on three priority areas for EPTB: (i) use of Xpert MTB/RIF in diagnosis, (ii) use of adjunct corticosteroids in treatment, and (iii) duration of treatment. The guidelines were developed using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) criteria, which were evidence based, and due consideration was given to various healthcare settings across India. Further, for those forms of EPTB in which evidence regarding best practice was lacking, clinical practice points were developed by consensus on accumulated knowledge and experience of specialists who participated in the working groups. This would also reflect the needs of healthcare providers and develop a platform for future research.

Keywords: Diagnosis, extrapulmonary tuberculosis, GRADE guidelines, treatment duration

Introduction

Extrapulmonary tuberculosis (EPTB) describes the various conditions caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection of organs or tissues outside the lungs. There are many forms of EPTB, affecting every organ system in the body. Some forms, such as TB meningitis and TB pericarditis, are life-threatening, while others such as pleural TB and spinal TB can cause significant ill-health and lasting disability. The burden of EPTB is high ranging from 15-20 per cent of all TB cases in HIV-negative patients, while in HIV-positive people, it accounts for 40-50 per cent of new TB cases1. The estimated incidence of TB in India was 2.1 million cases in 2013, 16 per cent of which were new EPTB cases, equating to 336,000 people with EPTB2.

Most of the resources for research, diagnosis and treatment are aimed at pulmonary TB as this form is most common and also most important with regard to TB control and public health. However, EPTB in all its forms has a significant impact on people suffering from the disease, their families, economy and health system. Diagnosis can be difficult, and delay can cause harm, but most people with EPTB can be cured if they have access to diagnosis and treatment with anti-TB drugs in time.

The main objective of these guidelines is to provide guidance on up-to-date, uniform, evidence-informed practices for suspecting, diagnosing and managing various forms of EPTB at all levels of healthcare delivery. These are aimed at clinicians and health workers at every level of care, in the public and private sectors, as well as healthcare providers, TB programme managers and policymakers. These can contribute to the Revised National TB Control Programme (RNTCP) towards improving the detection, care and outcomes in EPTB, further to help the Programme with initiation of treatment, adherence and completion while minimizing drug toxicity and overtreatment and to practices that minimize the development of drug resistance.

In 2014, the leadership of the Central TB Division and Directorate General of Health Services of the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India, recognized the need to develop evidence-informed guidelines for EPTB to sit alongside the guidelines for pulmonary TB from the RNTCP that were already in use. The guidelines development process was initiated by the Department of Medicine at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), New Delhi, which is the World Health Organization (WHO)-Collaborating Centre for Training and Research in TB and also the Centre of Excellence for EPTB. A group of expert clinicians representing different specialties was recruited from various institutions across India, who formed 10 technical advisory committees representing different organ systems affected by EPTB. A methodology support team was also constituted formed of representatives from Cochrane South Asia (Vellore, India) and Cochrane Infectious Diseases Group (Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, UK). The guidelines process was overseen and administered throughout by the core committee.

At the first guidelines meeting in March 2015, the technical advisory subcommittees (TACs) presented scoping reviews prepared for each form of EPTB to the core committee and methodology support team. This raised many potential points of equipoise that could be subject to formal evidence-informed guideline development using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) process. From this process, the core committee identified priority topics cutting across several organ systems in EPTB for guideline development. These were the areas where systematic review of the evidence was feasible given the available study data and time and resource constraints, where there were current important dilemmas in what to recommend and where decisions could improve patient care and patient outcomes or had important resource implications. The committee viewed this guidelines process as an essential step in embedding evidence-based processes and part of a long-term vision for the country. There was also an appreciation that while the nature of the disease and the topics appeared clinical, all the decisions had potentially profound public health expenditure and management implications, as well as public health impacts in terms of improved outcomes.

The methodology support team, along with the members of TACs, prepared the evidence summaries for review by the guidelines panel between March and July 2015. As part of this process, existing systematic reviews were updated, and where no review was available, new systematic reviews were developed and carried out.

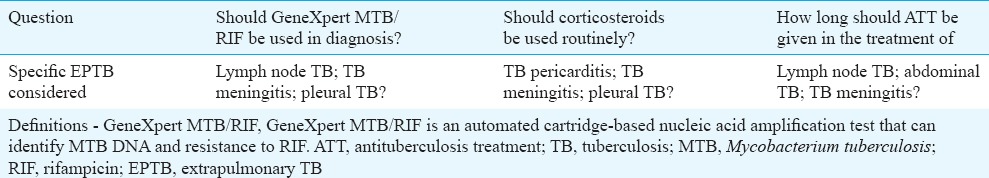

We limited our systematic reviews to areas where substantive evidence was available or there was an urgent priority for evidence-based clinical policy. Hence, the key questions covered in the evidence review were prepared (Table I).

Table I.

The key questions addressed in the guidelines

The Core Committee recognized the need to revisit many of the topic areas identified in the scoping process for systematic evidence review to inform the next iteration of these guidelines.

Details of the methods used in the preparation of each review are laid out in chapter 2 of the main guidelines document3,4,5. The general principles of systematic review followed those set out in the Cochrane Handbook6 (Box 1). Evidence summaries were produced by members of the TAC and the methodology support team and presented to the guidelines panel at the second meeting in July 2015. The guidelines panel considered the evidence in accordance with the GRADE criteria and decided on recommendations by consensus.

Box 1.

Steps in synthesizing the evidence used for the main guidelines

The guidelines process adhered to the GRADE criteria7 to produce a set of recommendations that were explicitly linked to the evidence they were based on, with consideration given to the various healthcare settings across India. The use of GRADE was in line with the WHO Handbook for Guideline Development8.

The GRADE criteria require that:

(i) Quality of evidence, as well as the effect estimate, is clearly defined.

(ii) Risk of bias of the relevant studies, directness of evidence, consistency of results, precision and other sources of bias in the available evidence are considered and reported for each important outcome.

(iii) Evidence summaries are used as the basis for judgments about the quality of the evidence and the strength of recommendations.

(iv) The balance of desirable and undesirable consequences, quality of evidence, values and preferences should be considered and reported when deciding on the strength of a recommendation.

(v) The strength of recommendations should be clearly reported and defined.

After the guidelines panel made the recommendations, the writing committee put together the guidelines document. Part of this process included the collation of expert opinion-based advice for clinicians on aspects of EPTB diagnosis and treatment not covered by the evidence-informed recommendations in a compendium of clinical practice points. These were based on the expert opinion of senior clinicians in medicine and surgery from across India and provided a basis for further refinement in evidence-informed guidelines development in future. This section of the guidelines seeks to address all aspects of diagnosis and treatment of EPTB and should be used as a reference.

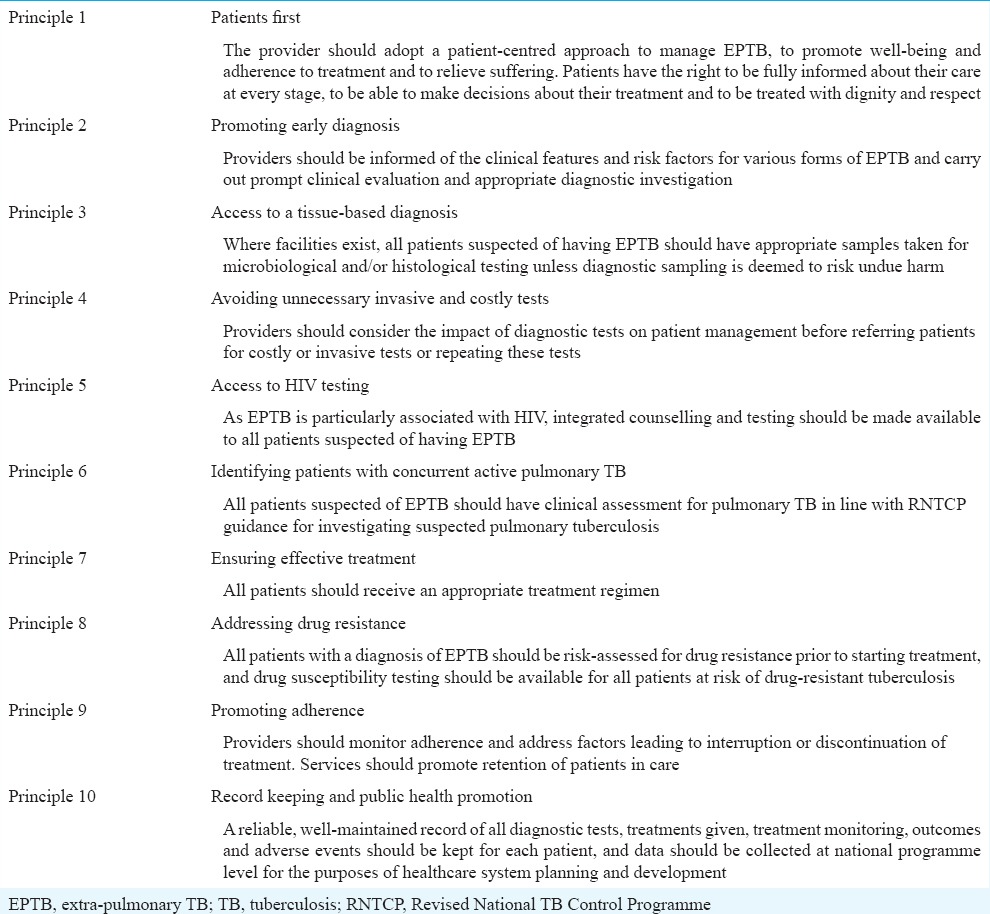

Principles of extrapulmonary tuberculosis (EPTB) care

In line with the International Standards of TB Care9, the guidelines group as a whole agreed on a set of principles about what every EPTB patient in India needs as a basic standard of care. These principles relate to a basic standard of care that all providers should seek to achieve, a complementary set to the Standards for TB Care in India9 and the recently developed technical operational guidelines for pulmonary TB in 201610. The principles are detailed in Table II.

Table II.

Principles of extrapulmonary tuberculosis care

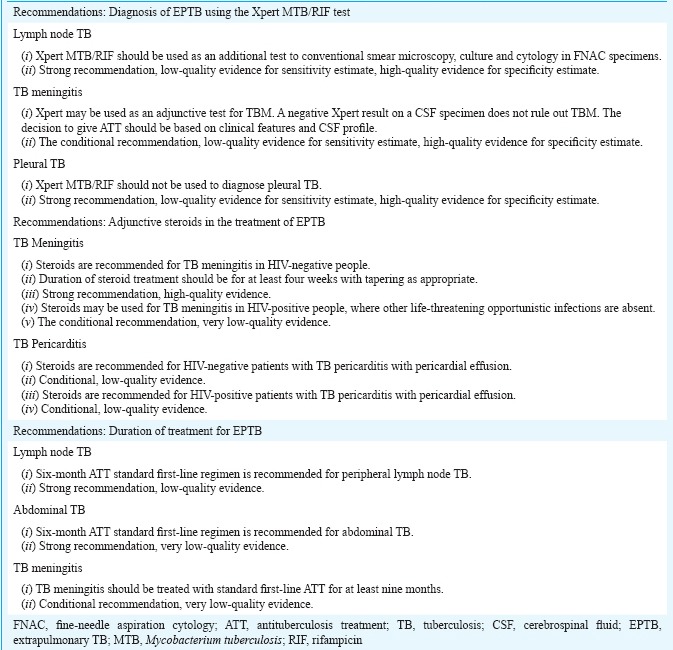

Summary of recommendations

[Box 2] provides the evidence-based recommendations made by the INDEX-TB guidelines panel. Tables III–V contain summaries of the evidence-to-decision process. The evidence summaries considered by the panel are available on the ICMR website11.

Box 2.

Summary of recommendations by INDEX-TB guidelines panel

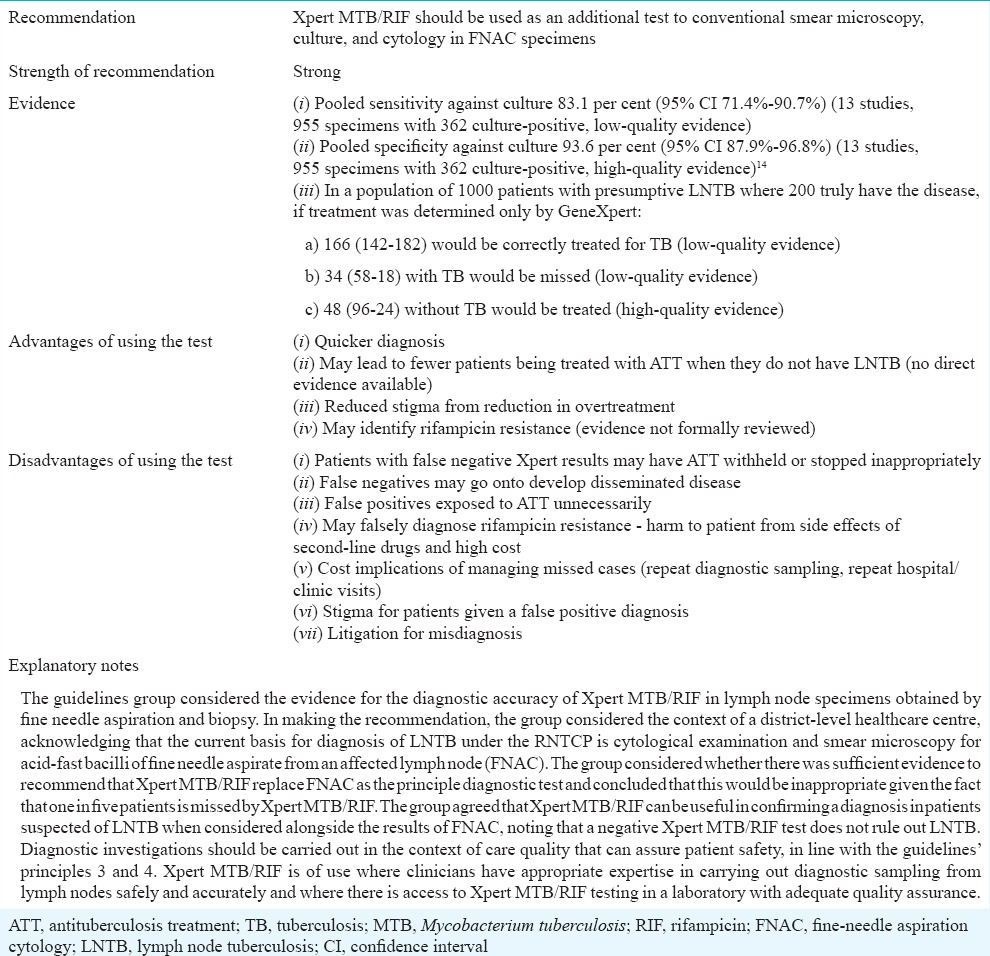

Table IIIA.

Role of Xpert MTB/RIF in diagnosing lymph node tuberculosis

Table VB.

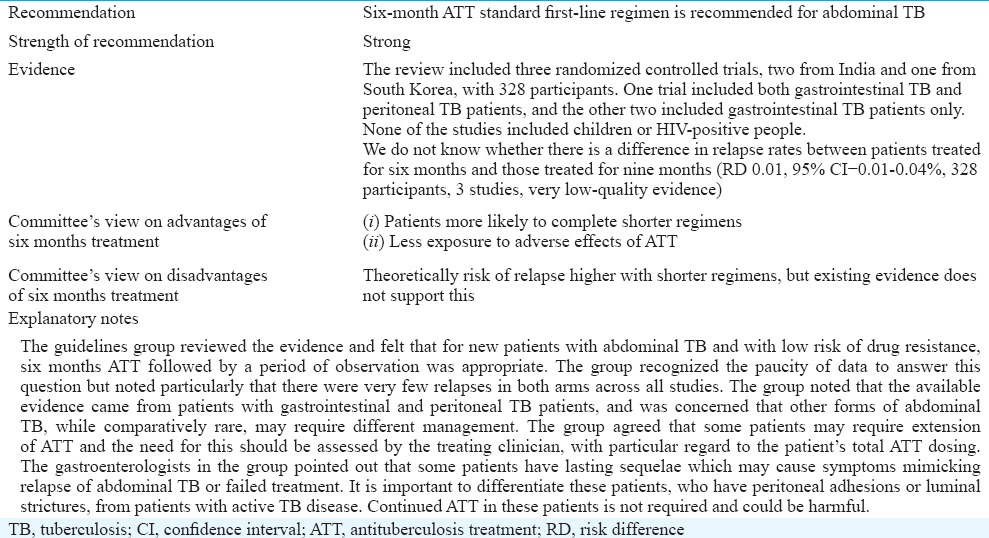

Duration of antituberculosis treatment for abdominal tuberculosis

Table IIIB.

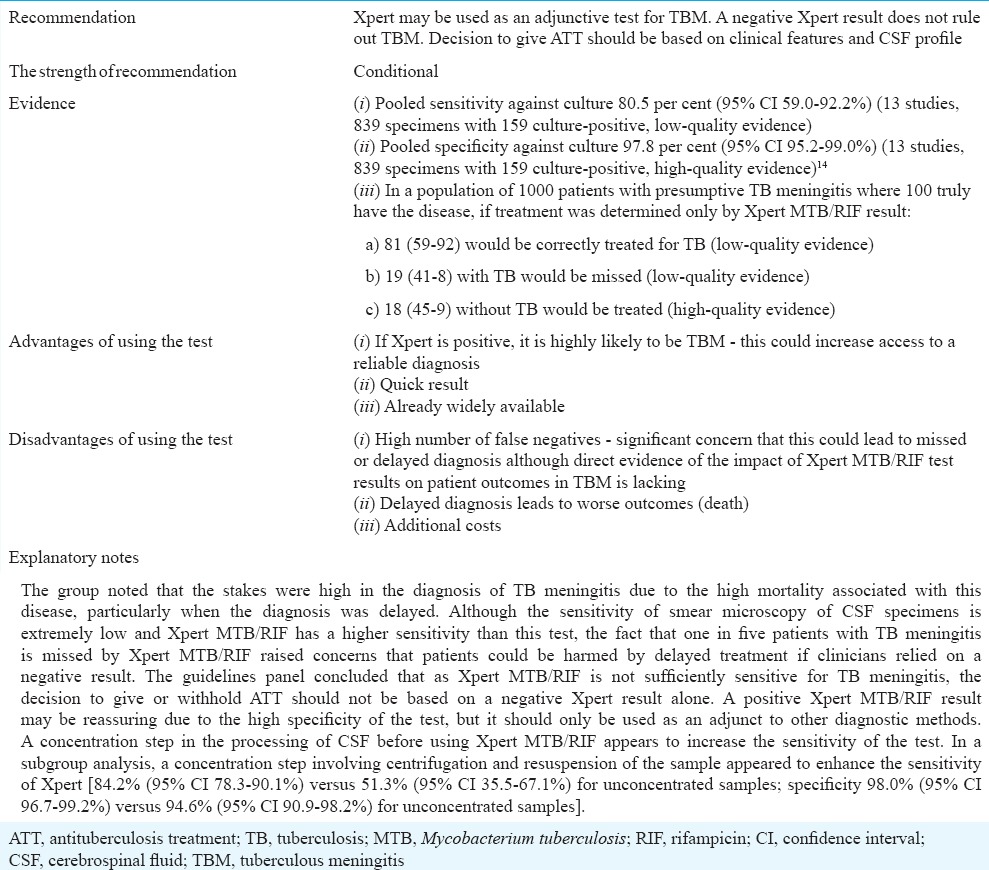

Role of Xpert MTB/RIF in diagnosing tuberculous meningitis

Table IVB.

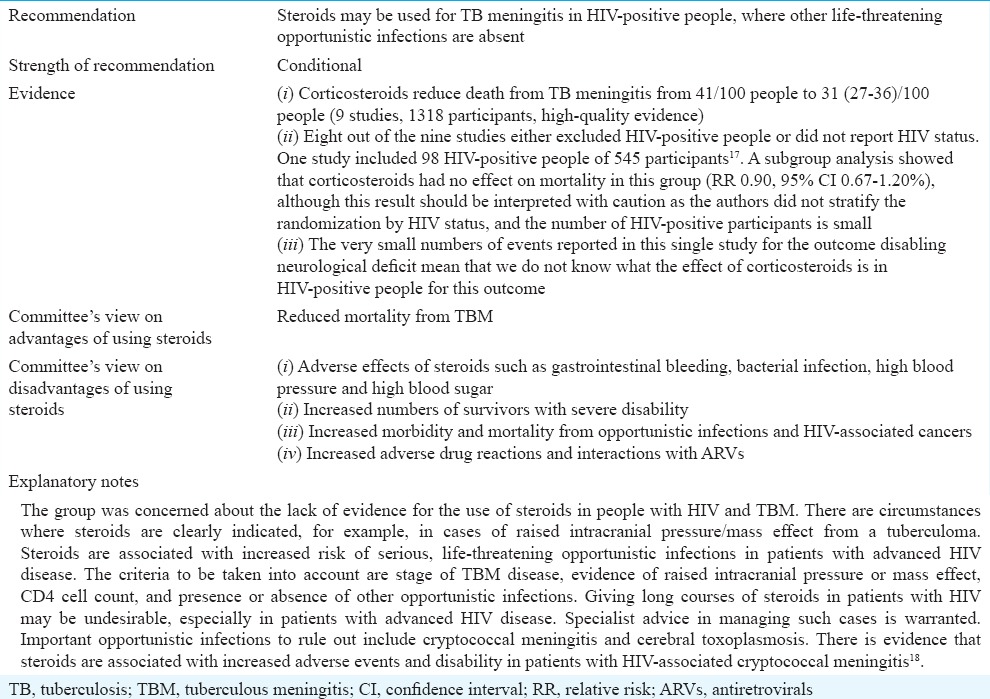

Role of corticosteroids in treating tuberculous meningitis in HIV-positive people

Table IVC.

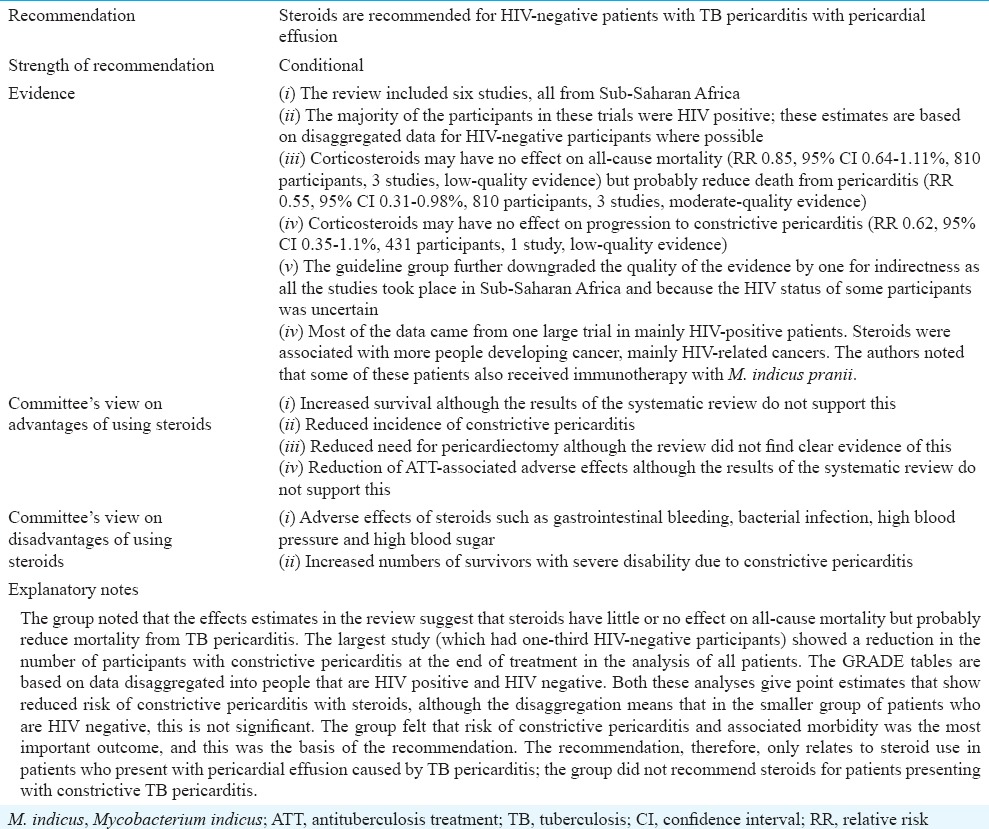

Role of corticosteroids in treating tuberculous pericarditis in HIV-negative people

Table IVD.

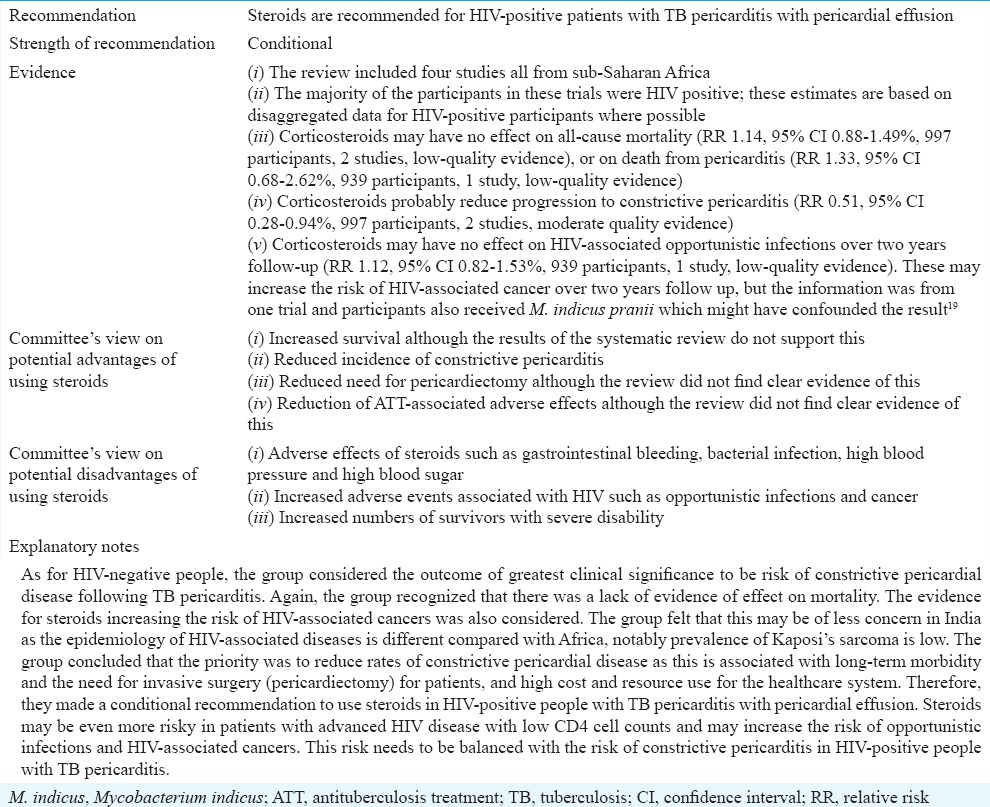

Role of corticosteroids in treating tuberculous pericarditis in HIV-positive people

Evidence to decision

Xpert MTB/RIF for EPTB

Xpert MTB/RIF is a commercially available diagnostic test for M. tuberculosis complex (MTB), which uses polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to test specimens for genetic material specific to MTB, and simultaneously detects a gene which confers resistance to rifampicin, rpoB12. It is manufactured by Cepheid, Sunnyvale, California, USA. Unlike other commercial PCR-based tests, it is a fully automated test using the GeneXpert® platform. The specimen is loaded into a cartridge, and all the steps in the assay are fully automated and contained within the unit. One of the reagents is powerfully tuberculocidal, making the used test cartridges safe to handle outside of a specialist laboratory environment. This allows the test to be brought closer to the clinical setting.

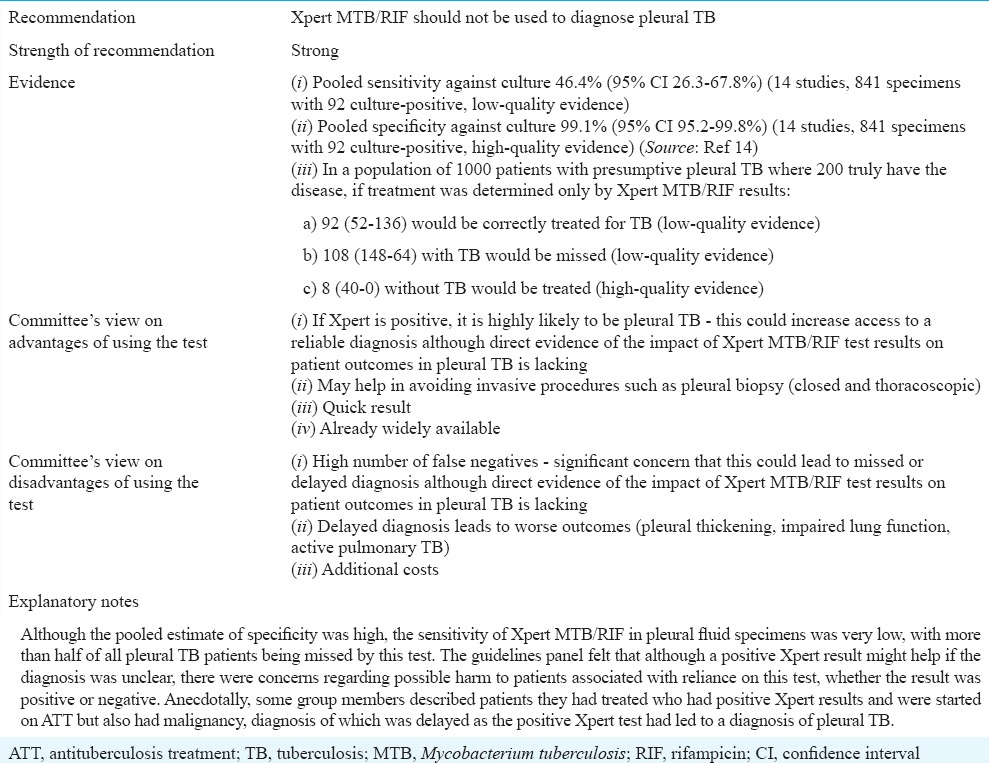

Xpert MTB/RIF was originally designed to test sputum samples from patients with active pulmonary TB and had been shown to have high accuracy for diagnosing TB in these patients13. Several investigators have tested the diagnostic test accuracy of Xpert MTB/RIF in non-respiratory specimens for the diagnosis of various forms of EPTB and have shown that accuracy varies considerably with specimen type and bacillary load. For this evidence summary, a systematic review carried out by Denkinger et al14 was used. In this review, diagnostic test accuracy studies using Xpert MTB/RIF and culture for the diagnosis of M. tuberculosis infection in three forms of EPTB were summarized, with pooled estimates of sensitivity and specificity14. As there was little data on sensitivity and specificity of Xpert MTB/RIF for the diagnosis of rifampicin resistance, this was not addressed in this review and hence has not been addressed within these recommendations. To ensure that the guidelines group was able to make recommendations based on the most up-to-date information, a summary of studies published since this review was undertaken in 2013 was also presented to the guidelines group.

The decision-making process for each of the recommendations on Xpert MTB/RIF is summarized in Tables 3A–3C. The evidence summaries and decision tables used by the guidelines panel are available in the complete guidelines document3.

Table IIIC.

Role of Xpert MTB/RIF in diagnosing pleural tuberculosis

Corticosteroids in EPTB

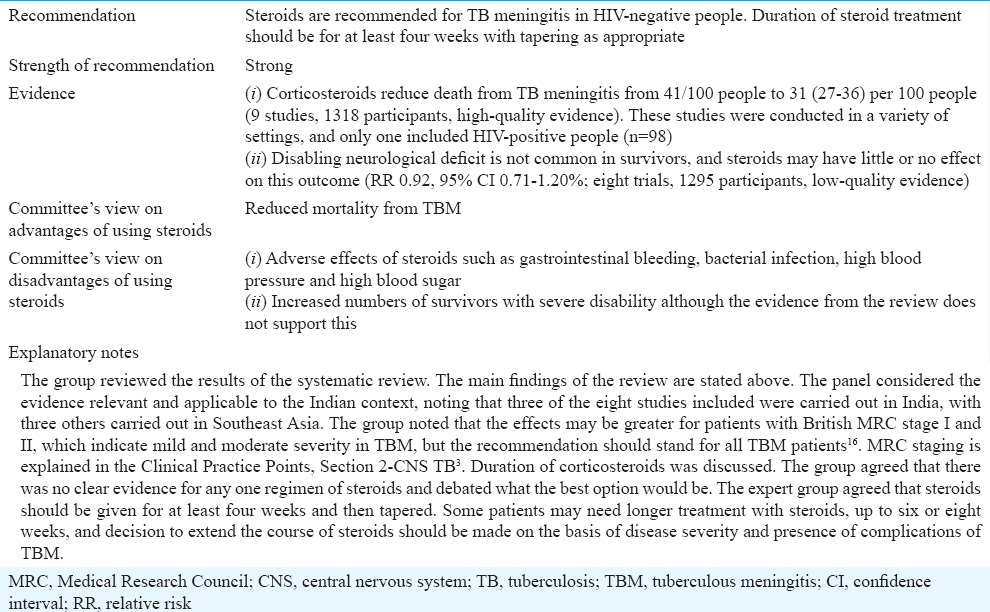

The guidelines panel considered evidence from the updated Cochrane review on corticosteroids for managing tuberculous meningitis (TBM)15. The evidence considered for various decisions on the use of corticosteroids is provided in Tables IVA–E.

Table IVA.

Role of corticosteroids in treating tuberculosis meningitis in HIV-negative people

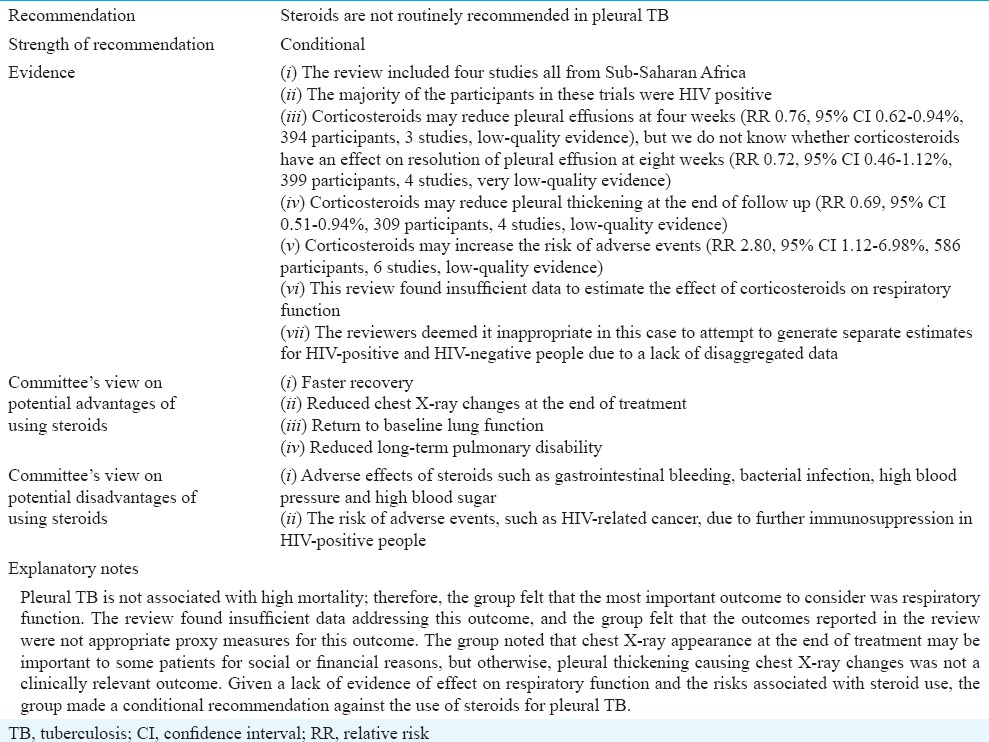

Table IVE.

Role of corticosteroids in pleural tuberculosis

The guideline group considered the evidence separately for HIV-negative and HIV-positive individuals because HIV co-infection is associated with particular complications of TBM disease and particular adverse events associated with steroid use. The guidelines group reviewed evidence summarized from the updated Cochrane review15.

Interventions for treating tuberculous pericarditis20

The group considered the evidence for HIV-positive people with TB pericarditis separately, principally because there was a concern about corticosteroids leading to increased risk of HIV-associated adverse events.

Corticosteroids in treating pleural TB

Pleural TB is one of the most common forms of EPTB. Characterized by pleural effusion, it usually resolves without treatment of any kind, but untreated patients may experience longer duration of the acute symptoms and risk recurrence of active TB at a later point in time21. Pleural TB can be complicated by massive effusion leading to respiratory compromise in the short term and pleural thickening, fibrosis and pleural adhesions causing impaired respiratory function in the medium to long term.

Pleural TB is thought to be caused by a delayed-type (type IV) hypersensitivity reaction, following mycobacterial infection of the pleura22. This explains the tendency towards resolution of the effusion and associated symptoms with or without treatment of the TB infection. There appears to be a spectrum of disease in pleural TB in terms of the extent of the underlying lung infection, which could be important in terms of patient outcomes and the potential for corticosteroids to be effective. The extent of underlying lung infection seems to be an important determinant of outcome23.

This review was conducted because there was uncertainty about the efficacy of corticosteroids in reducing the short-term and long-term effects on the acute symptoms of pleural TB and the long-term sequelae. Steroids are associated with several adverse effects, especially in people with HIV, and administering them in the absence of evidence of efficacy may be exposing patients to unnecessary risk.

Duration of treatment in EPTB

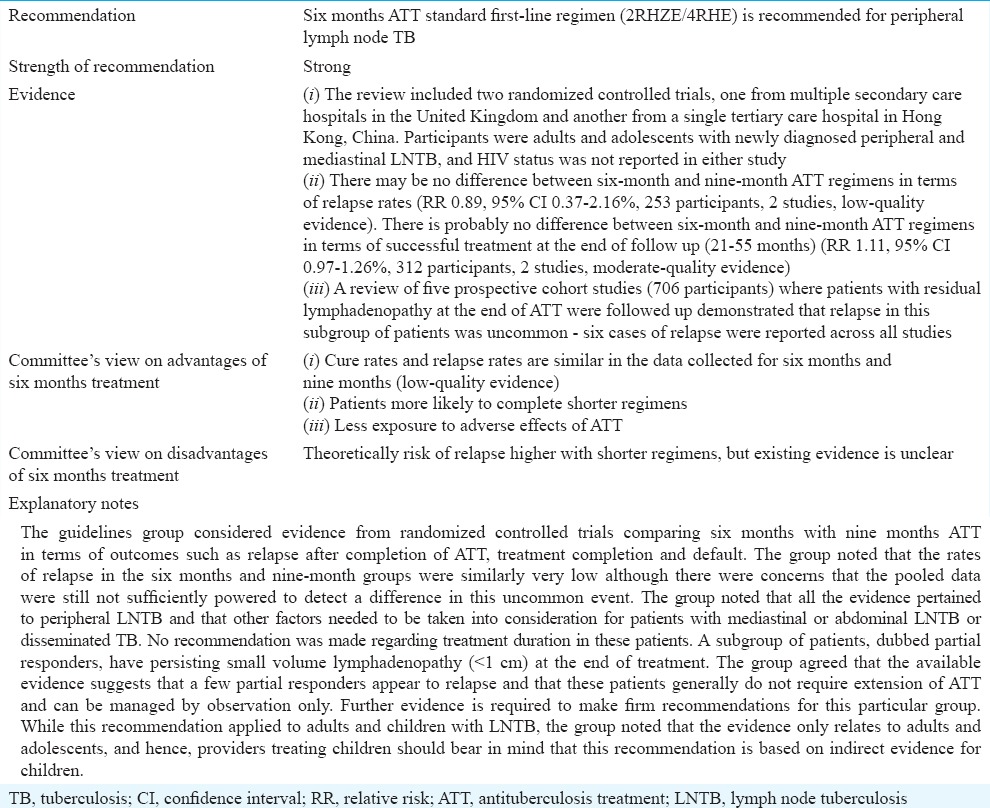

Duration of treatment in peripheral lymph node tuberculosis (LNTB)

Lymph node tuberculosis can present with the involvement of peripheral, mediastinal and/or abdominal lymph nodes as well as enlarged lymph nodes perceivable clinically or visualized on chest X-ray, abdominal ultrasound scan or computed tomography, and clinical features sometimes include weight loss, fever and night sweats. The problem of persistently enlarged lymph nodes at the end of treatment has vexed clinicians and some practitioners extend treatment duration in such patients, fearing relapse of active TB disease in this group. The evidence for the decisions are provided in Tables VA–C.

Table VA.

Duration of antituberculosis treatment for lymph node tuberculosis

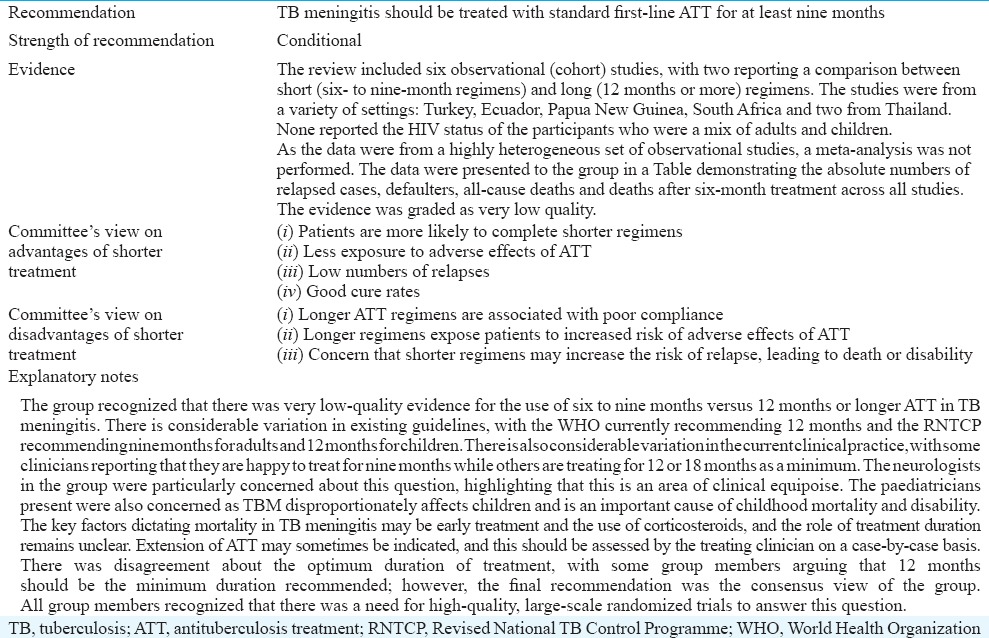

Table VC.

Duration of antituberculosis treatment for tubercular meningitis

Duration of treatment in abdominal TB

Abdominal TB can present with isolated involvement of any of the following sites: peritoneal, intestinal, upper gastrointestinal (oesophageal, gastroduodenal), hepatobiliary, pancreatic and perianal. The clinical features as well as diagnostic modalities depend on the site of involvement. Internationally, most guidelines recommend treating all types of abdominal TB with the same regimen as for pulmonary TB – a two-month intensive phase with four drugs (isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide and ethambutol) followed by a four-month continuation phase with isoniazid and rifampicin. However, the evidence base for this practice is extrapolated from the studies of pulmonary TB cases, and direct evidence for the optimum duration of treatment in abdominal TB has been lacking.

Shorter duration of treatment may increase compliance, leading to reduced numbers of relapses as well as the emergence of drug resistance strains. Furthermore, shorter regimens decrease the risk of anti-tubercular drug toxicity. Whether six-month regimen achieves successful treatment rates as good as with nine-month regimen without significantly increasing the number of relapses is the key concern for accepting a shorter antitubercular treatment (ATT) regimen. The present review aims to evaluate the effects of treatment with the six-month regimen as compared to the nine-month regimen for abdominal TB.

Duration of treatment in tuberculous meningitis

TBM constitutes a medical emergency, and it is essential to start ATT as soon as it is suspected to reduce rapidly progressing, life-threatening outcomes. In contrast to pulmonary TB, there is a lack of standardized international recommendations for treating TBM. This is partly due to the limited existing evidence regarding the optimal choice and dose of antitubercular drugs, as well as the most appropriate duration of treatment for this form of EPTB.

Two main arguments have led to the perception that longer treatment (than for pulmonary TB) is needed for TBM to bring about microbiological cure and prevent relapse. The first one is that the blood–brain barrier hinders the penetration of antitubercular drugs to reach adequate drug concentration in the infected site. The second one concerns relapse rates. When assessing pulmonary TB regimens, relapse rates of 5 per cent are generally considered acceptable24. However, relapse of TBM is fearsome as it is a life-threatening condition and can lead to severe neurodisability. Thus, whether any risk of relapse is tolerable for TBM is to be considered when establishing TBM regimens. However, longer ATTs reduce compliance and increase drug toxicity and costs25.

The standard first-line regimen for drug-sensitive TBM, according to the WHO guidelines26, is a two-month intensive phase with isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide and ethambutol or streptomycin followed by a 10-month continuation phase with isoniazid and rifampicin (2HRZE or S/10HR). Several different regimens are used in the current practice, with variations regarding doses, selection of the fourth drug and duration of treatment from six to more than 24 months. There are variations in practice regarding the number of drugs used in both the intensive and continuation phases. As an example, the South African regimen consists of a six-month intensive course with four drugs (isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide and ethambutol) with no continuation phase. A study reviewing the duration of treatment for TBM by comparing case series of both adults and children showed similar completion and relapse rates between six-month treatment regimens including at least isoniazid, rifampicin and pyrazinamide and longer treatment25.

Given the potentially devastating outcomes of relapse on one hand, and the disadvantages of long therapy on the other hand, we performed a systematic review of literature in an attempt to establish the most appropriate duration of treatment for TBM.

Research priorities and future update of the guidelines

The scoping process that informed the choice of priority topics for these guidelines also highlighted many other areas of uncertainty and variation in practice which could benefit from further research. The main guidelines document contains a list of topics identified by the guidelines panel as priority areas for further research3. In addition, the process highlighted the need for standardized case definitions and outcome definitions in all forms of EPTB.

The core committee and Government of India recognized that these guidelines represented the start of a process of developing evidence-informed EPTB guidelines in India and this would be further developed over time. There was a commitment to updating aspects of these guidelines in the next three to six years, by which time these topics would be revisited and additional priority topics considered.

Acknowledgment

The guidelines development process was made possible by the financial support from Global Health Advocates, India. Dr M.C. Misra (Director, AIIMS, New Delhi) provided the venue and administrative support for the meetings. Drs Neeraj Nischal, Bharati Kalottee and Sapna Naveen facilitated meetings of the Guidelines Group. Dr Bobby John (Global Health Advocates, India) arranged for the financial support for the meetings. Publication and dissemination of the guidelines was supported in part by a financial contribution from WHO in India with efforts of Dr Achuthan Nair Sreenivas, National Professional Officer (TB), at WHO. Dr S.K. Sharma was supported by the JC Bose Fellowship (No. SB/SB2/JCB-04/2013) of the Ministry of Science & Technology, Government of India.

Footnotes

Other Contributors (names listed alphabetically):

Agarwal Manisha, Agarwal Ritesh, Aggarwal Aditya, Aggarwal Anil K, Agrawal Smriti, Aneja Satinder, Anupama, Anuradha S, Arora Ankur, Arora Reema, Babu BM, Bakshi Jaimanti, Balamugesh T, Bansal Reema, Basu Soumyava, Bhargava Rakesh, Bhari Neetu, Bhatia Rajesh, Billangadi Reeta, Binit Kumar Singh, Biswas Jyotirmaya, Bobby John, Borthakur Bipul, Chana Sarat, Chandhiok Nomita, Chauhan LS, Chauhan Vipin, Chawla Rohan, D Ramesh, Das Chandan J, Das Dipankar, Das Vinita, Deepti Vibha, Dewan RK, Dhaliwal Lakhbir, Dhar Anita, Dhooria Sahajal, Dhorepatil Bharati, Dinesh M, Dogra PN, Fernandes Lalita, Garg Ajay, Garg Ravina Kumar, Gautam VK, Gulati Shefali, Gupta Gaurav, Gupta Vaishali, Handique Akash, Hari Krishna J, Hari Smriti, Hyder Md Khurshid Alam, Jaikishan, Jain BK, Jain Deepali, Jain Sanjay, Jain Siddharth, Janmeja Ashok K, Jat KR, Jayaswal Arvind, Jena AN, Jha Saket, Jorwal Pankaj, Joshi Mohit, Kairo Arvind, Kalottee Bharati, Kamath S, Karthikeyan G, Kashyap Surinder, Kedia Saurabh, Khanna Ashwani, Kirubakaran Richard, Kohli Mikashmi, Kriplani Alka, Kulshrestha Vidushi, Kumar Arvind, Kumar Raj, Kumar S, Kumar Sunesh, Kwang Rim, Lodha R, Mahajan Rahul, Mahendradas Padmamalini, Makharia Govind K, Malik Sonia, Manjunath, Maru Yashwant Kumar, Mathai Annie, Mathur Sandeep, Memon Saba Samad, Mian Agrima, Mittal Abhenil, Modi Manish, Mohan Kameswaran, Mohapatra PR, Mohindra Sandeep, Mohnish Grover, Mukharjee Aparna, Mukharjee MK, Mukherji Subeer, Munjal YP, Munje Radha, Murthy Kalpana Babu, Murthy Somasheila, Nair AS, Narain JP, Narain Shishir, Narasimhan Calambur, Padmapriyadarsini C, Pal Raj, Paliwal Vimal Kumar, Parakh Ankit, Parihar Anit, Patnaik Jyoti, Prasad Kameshwar, Prasad Rajendra, Puri Amarender Singh, Puri Poonam, Ragesh R, Rai Praveer, Rajasekaran S, Ramam M, Ramachandran Ranjani, Rathinam S, Ravindran C, Reddy D Ramachandra, Rout Saurabh, Sachdev Atul, Saikia Rabin, Sandeep Kumar, Saraf SK, Sehgal Inderpaul Singh, Seth Sandeep, Sethi GR, Sharma Abhishek, Sharma Raju, Sharma Rohini, Sharma Sangeeta, Sharma Vineet, Sharma Vishal, Shivanand Ramachana, Shukla HS, Shunyu NB, Sikka Kapil, Singh Anup, Singh Manmohan, Singh Meenu, Singh Navjeevan, Singh Prabhjot, Singhal Kamal K, Singla Rupak, Sinha Sanjeev, Soneja Manish, Sophie Jullien, Sreenivasan Ravi, Srivastava Anshu, Srivastava Anurag, Sudarshan S, Sudha Ganesh, Suri Tejas M, Swaminathan Soumya, Thapa Pranjit, Thomas Monica, Thomas Iype, Tripathi Madhavi, Tripathi Manjari, Tripathi Suryakant, Tripathy Devjyoti, Tuli SM, Varghese Mathew, Varma Subhash, Vashishta Bhagirath Kumar, Vengamma B, Venkata Karthikeyan C, Venkatesh Pradeep, Verma Ashok, Vidyasagar Sudha, Vikraman Sumit Sural, Vaish Atul, Yadav CS, Yadav Siddharth, Yewale Vijay

Conflicts of Interest: None.

References

- 1.Sharma SK, Mohan A. Extrapulmonary tuberculosis. Indian J Med Res. 2004;120:316–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.New Delhi: World Health Organization, Regional Office for South-East Asia; 2014. World Health Organization. Tuberculosis control in the south-east Asia region annual TB report 2015; p. 61. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Index TB Guidelines. Guidelines on extra-pulmonary tuberculosis for India. World Health Organization. 2016. [accessed on January 3, 2017]. Available from: http://www.icmr.nic.in/guidelines/TB/Index-TB%20Guidelines%20-%20green%20colour%202594164.pdf .

- 4.Guidelines: Central TB Division. [accessed on January 3, 2017]. Available from: http://www.tbcindia.nic.in/index1.php?lang=1&level=1&sublinkid= 4571&lid=3176 .

- 5.New Delhi: All India Institute of Medical Sciences; 2017. [accessed on January 3, 2017]. Index-TB Guidelines. Available from: http://www.aiims.edu/en/notices/notices.html?id=5662 . [Google Scholar]

- 6.Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Sterne JEC. Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Assessing risk of bias in included studies. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0. The Cochrane Collaboration. 2011. [accessed on December 22, 2016]. Available from: http://www.handbook.cochrane.org/chapter_8/8_16_chapter_information.htm .

- 7.GRADE Home. [accessed on January 24, 2017]. Available from: http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/

- 8.Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2012. World Health Organization. WHO handbook for guideline development. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nair SA, Sachdeva KS, Malik P, Chandra S, Ramachandran R, Kulshrestha N, et al. Standards for TB care in India: A tool for universal access to TB care. Indian J Tuberc. 2015;62:200–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijtb.2015.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Central TB Division. Technical and operational guidelines for TB control in India 2016. New Delhi, India: Central TB Division. 2016. [accessed on December 26, 2016]. Available from: http://www.tbcindia.gov.in/index1.php?lang=1&level=2&sublinkid=4573&lid=3177 .

- 11.INDEX-TB Guidelines. Evidence Summaries and Guideline Panel Decision Tables Core Group Guideline Meeting, 14-18 July 2015, August 16. 2016. [accessed on January 3, 2017]. Available from: http://www.icmr.nic.in/guidelines/TB/INDEX-TB%20Evidence%20Summaries%20FINAL%2016%20Aug%202016.pdf .

- 12.Blakemore R, Story E, Helb D, Kop J, Banada P, Owens MR, et al. Evaluation of the analytical performance of the Xpert MTB/RIF assay. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:2495–501. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00128-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steingart KR, Schiller I, Horne DJ, Pai M, Boehme CC, Dendukuri N. Xpert® MTB/RIF assay for pulmonary tuberculosis and rifampicin resistance in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;1:CD009593. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009593.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Denkinger CM, Schumacher SG, Boehme CC, Dendukuri N, Pai M, Steingart KR. Xpert MTB/RIF assay for the diagnosis of extrapulmonary tuberculosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir J. 2014;44:435–46. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00007814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prasad K, Singh MB, Ryan H. Corticosteroids for managing tuberculous meningitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;4:CD002244. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002244.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Medical Research Council. Medical Research Council Report (1948). Streptomycin treatment of tuberculous meningitis. Lancet. 1948;1:582–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thwaites GE, Nguyen DB, Nguyen HD, Hoang TQ, Do TT, Nguyen TC, et al. Dexamethasone for the treatment of tuberculous meningitis in adolescents and adults. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1741–51. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beardsley J, Wolbers M, Kibengo FM, Ggayi AB, Kamali A, Cuc NT, et al. Adjunctive dexamethasone in HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:542–54. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1509024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mayosi BM. Cochrane database of systematic reviews. Chichester, UK: John Wiley and Sons, Ltd; 2002. [accessed on December 22, 2016]. Interventions for treating tuberculous pericarditis. Available from: http://www.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD000526/abstract . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mayosi BM, Ntsekhe M, Bosch J, Pandie S, Jung H, Gumedze F, et al. Prednisolone and Mycobacterium indicus pranii in tuberculous pericarditis. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1121–30. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1407380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Light RW. Update on tuberculous pleural effusion. Respirology. 2010;15:451–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2010.01723.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rossi GA, Balbi B, Manca F. Tuberculous pleural effusions. Evidence for selective presence of PPD-specific T-lymphocytes at site of inflammation in the early phase of the infection. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1987;136:575–9. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/136.3.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shu CC, Wang JT, Wang JY, Lee LN, Yu CJ. In-hospital outcome of patients with culture-confirmed tuberculous pleurisy: Clinical impact of pulmonary involvement. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11:46. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-11-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Donald PR. The chemotherapy of tuberculous meningitis in children and adults. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2010;90:375–92. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2010.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Loenhout-Rooyackers JH, Keyser A, Laheij RJ, Verbeek AL, van der Meer JW. Tuberculous meningitis: Is a 6-month treatment regimen sufficient? Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2001;5:1028–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.2nd ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014. [accessed on December 22, 2016]. World Health Organization. Guidance for national tuberculosis programmes on the management of tuberculosis in children. (WHO Guidelines Approved by the Guidelines Review Committee) Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK214448/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]