Abstract

This research was part of a larger mixed-methods study examining culture, distress, and help seeking. We surveyed 209 Japanese women living in the United States recruited from clinic and community-based sites, and carried out semi-structured ethnographic interviews with a highly distressed subsample of 25 Japanese. Analytic Ethnography revealed that women described themselves as a “self-in-context,” negotiating situations using protective resources or experiencing risk exposure. Women experienced quality of life (QOL) when they were successful. However, a related goal of achieving Ikigai (or purpose in life) was differentiated from QOL, and was defined as an ongoing process of searching for balance between achieving social and individual fulfillment. Our resulting hypothetical model suggested that symptom level would be related to risk and protective factors (tested for the full sample) and to specific risk and protective phenomenon (tested in the distressed subsample). The t tests in the full sample found that women who were above threshold for depressive symptoms (n = 26) had higher social stressor and lower social support means. Women who were above the threshold for physical symptoms (n = 99) had higher social stressor means. Analysis of the interviewed subsample found that low self-validation and excessive responsibilities were related to high physical symptoms. We conclude that perceived lack of balance between culturally defined, and potentially opposing, markers of success can create a stressful dilemma for first-generation immigrant Japanese women, requiring new skills to achieve balance. Perceptions of health, as well as illness, are part of complex culturally based interpretations that have implications for intervention for immigrant Japanese women living in the United States.

Keywords: mental health, clinical focus, depression, health behavior/symptom focus, ethnography, methods, Asian, population focus

About myself? I think I was like … a zombie. If somebody understood the whole situation, and looked at me, they might say “It’s not too bad.” But I have never felt this down before … (I) got angry with little things that I didn’t have to be angry about. I became easily upset, and when I felt that way, I couldn’t control myself. … I was not a mother at that time. I really don’t think I was a human being.

This narrative is from a young mother of two preschool children explaining her life situation, how bad she felt as a mother, how much she believed she was an immature person, and how terrible she felt about herself. Similar stories about Japanese women’s struggles with distress and depression while living in the United States have been reported elsewhere (Saint Arnault, 2002; Saint Arnault & Shimabukuro, 2012) and may be part of complex processes involving the development of meaning for immigrant and sojourner women. Perceptions about meaning in life, or life satisfaction evaluations, rest on culturally informed evaluations of distress. However, little is known about the meaning of the symptoms women experience or how high symptom burden intersects with other social and psychological evaluations about the quality of one’s life. This research uses mixed methods to explore the meanings of symptoms and overall meaning in life for a sample of Japanese women living in the United States.

The Asian population in the United States grew rapidly between 1990 and 2000, increasing nationally by 3.3 million, which represents a 48% increase. Currently, the Asian population is 11.9 million, which is 4.2% of the total population (U.S. Census Bureau, 2002). More than 235,000 Japanese nationals lived in the United States in 1990 (Ohnishi & Ibrahim, 1999). These Japanese nationals live in the United States with their families, and many migrate for work in manufacturing sectors, with 64% working in automotive-related positions (Japanese Investment Direct Survey [JIDS], 2007). However, in Michigan, the Japanese population doubled between 1990 and 2000. According to the 2003 American census bureau, there were 17,229 Japanese nationals residing in Michigan (U.S. Census Bureau, 2002), and over the past 10 years, the population of Japanese nationals has increased by 31% in Michigan (JIDS, 2007).

Asian immigrant women in general, have gendered mental health risks. Gendered risks are patterns of psychosocial and cultural factors that place members of a gender group at disproportional vulnerability for a given illness. Gendered risk factors for females include separations from extended families that dramatically affect their ability to perform, changes in social roles related to social network changes, dependency due to migration laws, employment problems including gender-based discrimination and occupational options, gender-based violence, income inequality, social status and rank issues that are amplified in new social networks, and unremitting responsibility for the care of others (World Health Organization [WHO], 2000). Gendered rules for proper Asian female behavior may include notions that women should sacrifice their personal needs for the good of their husbands and children, leading to a tendency to ignore or deny their own pain or symptoms (Ro, 2002; Ta & Hayes, 2010; Ta, Juon, Gielen, Steinwachs, & Duggan, 2007; Williams, 2002).

Some estimates find prevalence of depression among Asian women living in the United States ranging from 25% to 40% (Mui & Suk-Young, 2006). After controlling for socioeconomic factors, East Asian immigrant women have 50% to 80% higher risk for depression when compared with Whites (Hwang & Ting, 2008; Takeuchi et al., 1998). The prevalence of depression in Koreans living in the United States is as high as 25% (Cho, Nam, & Suh, 1998; Shibusawa & Mui, 2001). Mui et al. found that 40% of the regional probability sample (n = 407) of Asian elderly immigrants scored 11 or above on the 30-item Geriatric Depression Scale. There were also intergroup differences among the Asian subcultures, and the Japanese mean score was the highest (Mui, Suk-Young, Chen, & Domanski, 2003). Research has also shown that Asian women may be as much as 2 times more likely than men to report a lifetime depressive episode (Takeuchi et al., 1998). Finally, an adjusted analysis of Pregnancy, Risk, Assessment, and Monitoring System (PRAMS) in Hawaii found that Chinese (odds ratio [OR] = 1.8, 95% confidence interval [CI] = [1.3, 2.5]), Korean (OR = 1.8, 95% CI = [1.3, 2.7]), and Japanese (OR = 1.5, 95% CI = [1.1, 2.1]) women were significantly more likely to have postpartum depression compared with White women (Ta & Hayes, 2010).

Purpose, Meaning, and Ikigai

One’s purpose in life has been described as a cognitive life organization that arranges goals, behaviors, cognition, and evaluation about life similar to goal orientation (McKnight & Kashdan, 2009). Life purpose may confer meaning and provide an existential, philosophical, or even spiritual dimension that provides comfort in suffering (Frankl, 1985). Meaning and purpose in life have been described as a sense of coherence, providing a mental representation about why events occur and what these imply about the future (King, Hicks, Krull, & Del Gaiso, 2006). While cross-cultural research linking purpose, meaning, and health outcomes is underdeveloped, some trends can be gleaned for the existing literature. The concept of purpose in life, as a component of psychological well-being, has been associated with reduced mortality, mortality, and cardiovascular events (Cohen, Bavishi, & Rozanski, 2015). Meta-analyses of 10 prospective studies (n = 137,142), with a mean follow-up of 8.5 years, found a significant association between higher purpose in life and reduced all-cause mortality (adjusted Relative Risk [RR] = 0.77, CI = [0.69, 0.86], p <0.00) and cardiovascular events (adjusted RR = 0.81, CI = [0.73, 0.90], p < .001). Some theorists speculate that these associations might be explained by enhanced regulation of physiological systems involved in the stress response for those with higher meaning or purpose in life. Using data from the Midlife in the United States (MIDUS) survey, one longitudinal study of 985 adults examined the relationship between life purpose and allostatic load, while controlling for age, gender, education, ethnicity, and social support. They found that greater life purpose predicted lower levels of allostatic load at the 10-year follow-up (Zilioli, Slatcher, Ong, & Gruenewald, 2015). Purpose in life has also been suggested to be a transcultural protective factor. For example, in a study of Pakistan earthquake survivors (N = 200), purpose in life predicted lower posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depressive symptoms (Feder et al., 2013).

The Japanese concept of Ikigai is a construct composed of both purpose and meaning in life (Demura, Kobayashi, & Kitabayashi, 2005). Shibata (1998) describes Ikigai as a feeling of achievement afforded when people feel they are doing something useful (Shibata, 1998). Maeda, Asano, and Taniguchi (1979) defined Ikigai as a subjective, happy feeling. Pinquart and Sorensen (2001) said that Ikigai should be understood as a comprehensive concept related to happiness and satisfaction in life, as well as to the cognitive evaluation of the meaning of one’s life, self-esteem, and self-efficacy.

Ikigai may be a culturally sanctioned standard that Japanese people may use to evaluate well-being. Ikigai is influenced by age, gender, social context, social activities, and social networks (Fujimoto et al., 2004; Hasegawa, Hujiwara, Hoshi, & Shinkai, 2003; So, Imu, An, Okada, & Shirasawa, 2004). Ikigai studies across the lifespan have found that it has a protective effect, including prolongation of activity and life expectancy (Honma, Naruse, & Kagamimori, 1999), enhanced quality of life (QOL; Demura et al., 2005), more successful aging (Hoshino, Yamada, Endo, & Nakura, 1996a, 1996b), and higher subjective well-being (Shirai et al., 2006). In general, about 85% of elderly people in Japan had Ikigai (Aoki & Matsumoto, 1994). Yoshida (1994) investigated the relationship among Ikigai, ego development, and internalizing problems in 1,410 Japanese senior high school students, finding that low Ikigai was related to feelings of depression and emptiness. For Japanese women, Ikigai was strongly related to family relations and psychological factors such as depression (Shirai et al., 2006), high life satisfaction (Fujimoto et al., 2004), and negatively related to depressive feelings (Chiba & Saito, 1998). In summary, Ikigai seems to be a part of Japanese culturally based set of values upon which culturally and socially defined behavioral expectations are evaluated (Oishi & Diener, 2001), and against which achievement of a good or successful life is measured (Shirai et al., 2006).

While the relationship between Ikigai and mental and physical health has been suggested in the literature, little is known about the lived experience of distress and purpose in life for immigrants. This mixed-methods study used quantitative data from a survey sample of 209 Japanese immigrant women and qualitative data from a nested subsample of 25 distressed women. We used qualitative methods to understand the personal and social evaluation processes related to the distress experience, examining the interrelationships among distress, meaning, and social context. The model that resulted from these analyses generated hypotheses that were subsequently tested using quantitative data from the larger survey sample as well as the nested distressed subsample.

Method

Study Design and Sample

This mixed-methods study is part of a larger study that examined distress and help seeking in the Japanese immigrant women living in Michigan. This study used a convergent mixed-methods design with a highly distressed nested subsample. All procedures and materials for this study are approved by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board (IRB) and by our Community Advisory Board (CAB; consisting of five women and one man from various sectors of the Japanese community). All communication with women in this study was in the participant’s native language, including all written contacts, consents, surveys, and all research materials (Saint Arnault, 2009; Saint Arnault & Fetters, 2011).

Sample characteristics

This study sampled women of childbearing age who were born in Japan and were living in the United States for reasons other than their own education. We excluded women below 21 because, in Japanese culture, they rely primarily on their parents for their healthcare. We focused on foreign-born women because we were attempting to understand help-seeking processes that are the product of enculturation. To maximize the diversity of symptoms and help-seeking strategies, we sampled from both primary-care sites and the general community. The primary-care recruitment site was the Japanese Family Health Program, and the community-based recruitment sites included Japanese-specific schools and women’s clubs. The staff at both the primary-care clinic and the community-based agencies compiled lists of all of the women for whom they had addresses in the last 6 months. These staff then used random start interval sampling to select the sample and mailed survey packets to the selected women. This research team was blind to these names and addresses.

We sent 1,101 surveys to women in three waves over a 2-year enrollment period, and 133 were returned to sender. The quantitative data from the 209 survey respondents presented here represents a 22% average response rate. Using depressive and physical symptoms, 128 women were deemed highly distressed (60%); however, only 41 provided contact information, and of these, only 25 women agreed to be interviewed.

Instruments and Measures

The survey assessed demographic variables, which included age, length or time abroad, employment, and English fluency. English fluency was measured with the Stanford Foreign Language Oral Skills Evaluation Matrix (FLOSEM; Padilla & Sung, 1999). Depressive symptoms were assessed with a cultural adaptation of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression (CES-D) scale, which is a 20-item scale with a higher score indicating greater impairment (Radloff, 1977). Noh and colleagues reversed the wording of the positive affect items and have substantiated that these modifications improve the performance of the CESD with East Asian populations (Noh, Avison, & Kaspar, 1992), finding Cronbach’s alpha coefficients ranging between .71 and .89, with test–retest reliability of .68 for the revised scale. Cronbach alpha for our study was .90. We used a cutoff of 16 to identify high distress. Physical symptoms were measured with the Pennebaker Inventory of Limbic Languidness (PILL; Pennebaker, 1982), modified for use with Asian samples. The PILL is a self-report checklist designed to measure the frequency of experiencing a variety of common physical symptoms and diseases. We collapsed some items for precise translation and added six items specific to depression in people from some Asian cultures (abdominal cramps, dizziness, lightheadedness, pain in joints, pain in shoulders, weakness, and palpitations), resulting in an instrument with 46 items. Women with a score of 12 or higher on this instrument were deemed highly distressed. Perceived social support was measured with the 15-item Personal Resource Questionnaire (PRQ2000; Weinert & Brandt, 1987). Cronbach alpha for our study was .93. Stressful life events were measured with the Life Events subscale contained within the Ontario Mental Health Epidemiological survey (Lin, Goering, Offord, Campbell, & Boyle, 1996). This scale includes 16 stressful life events, including interpersonal, financial, legal, housing, and family illness problems.

Ethnographic interview

The ethnographic interview for this study is the Clinical Ethnographic Interview (Saint Arnault & Shimabukuro, 2012). The interview lasts about 90 min and uses unique, engaging, and interrelated participant activities. We begin with a social network map to frame help seeking within the social context. Then, the participant completes a retrospective overview of distress in a lifeline, linking past and subsequent stressors, symptoms, and actions (Frank, 1984; Gramling & Carr, 2004; Shimomura, 2011; Taguchi, Yamazaki, Takayama, & Saito, 2008). Next, the interviewee completes a card sort to describe her current distress in detail, creating an experiential map of her distress and symptom clusters. The interview is designed to help women identify and interpret their feelings and social context (Borgatti, 1999; Canter, Brown, & Groat, 1985; Fraser, Estabrooks, Allen, & Strang, 2009; Gordon, 2001; Neufeld et al., 2004).

Procedure

All participants signed informed consent for surveys, the interview, and the audiotaping. An incentive payment for the interview of 20 dollars was provided. The second author conducted the interviews in Japanese. Japanese research assistants including the second author transcribed audiotapes of the interviews. In instances where Japanese expressions or idioms were not easily translated into English, the translation team discussed the meaning and intention in the flow of the narratives. The accuracy of the transcription and translation was checked and finalized by the interviewer.

Analysis

For the qualitative portion of this study, we used Analytic Ethnography (AE), which allowed analysis of ethnographic data to test hypotheses as well as exploratory and inductive research analyses simultaneously (Lofland, 1995). The analysis process for this study involved free coding, use of memos on those codes, grouping codes, and carefully analyzing the data for emerging theoretical propositions (Charmaz, 2001; Lofland, 1995; Strauss & Corbin, 1990, 1998). Concepts were grouped into categories and themes with properties and dimensions, allowing “systematic comparison” and “conceptualizing” (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). ATLAS.ti 5.2.21qualitative software was used for data management and analysis. The transcribed Japanese text and translated English texts were used simultaneously throughout analysis. An audit trail was reviewed every other week by the senior author, random coding concepts were selected and discussed regularly by the research team, and emerging hypotheses were discussed at length in team meetings for verification of accuracy. The results reported here are consistent with previously published research by the lead author.

The qualitative analysis yielded a theoretical model that could be tested statistically. Unfortunately, as often true in studies that use nested subsample mixed-methods designs, the variables that emerge from qualitative analysis may not have been measured quantitatively in the entire sample. For example, in this study, the variables of Ikigai balance and QOL emerged in our qualitative analysis, and had not been measured quantitativly. Therefore, hypothesis testing included t tests of derived risk and protective variables to examine for the entire sample, and chi-square analyses of the transformed qualitative variables for the smaller subsample.

Qualitative Analysis Results

Women evaluated their QOL as a fluid and changing state that resulted from the interaction between their ability to use protective factors to mitigate risk factors and the resultant physical and emotional reactions. However, the ability to balance Ikigai (meaning and purpose in life) was perceived by the women as a mitigating or protective state that helped them feel healthy despite distress symptoms. Below, we will present each process separately.

Self-in-Context

Rather than emphasizing how they should directly alter situations, women described adjusting to social situations by using protective factors, or by compromising their physical and emotional freedom. In general, complicated social situations were understood by phrases such as “I cannot change the situation” or “The current situation is something that I cannot help.” Rather than focus on the level of difficulty or inconvenience of a situation, women would focus on how well they utilized the protective factors they possessed in their dealings with their situations to manage the risk factors.

Protective factors

Protective factors consisted of three resources: emotional support, social participation, and sense of social belonging. Using these resources brought women emotional security and social acceptance. Importantly, however, these three resources needed to exist together within reciprocal and trusting relationships, such as with family or friends. The statement below by one of the participants demonstrates these protective factors:

After all, I would have to open myself more to people. I don’t know how I can say it in a better way, but I felt as if they (the community of other Japanese women) did not know me well. And I would like them to know me well. You know, our looks do not necessarily show our true characters, right? If they can understand my true self without being tricked by how I look, I think I can open myself more easily. My family and old friends of mine have known me for a long time, and they understand my character well. So I feel comfortable seeing and talking with them. So I wish that I could be the same with people from fujin-kai (association of company wives). They have only known me for a year, and it takes time for them to get to know me. I feel irritated because I know that it takes time, but at the same time, I would like to be myself.

This example shows how the participant could not comfortably fit into the women’s group because she did not feel like she authentically belonged to the group. Even though she participated in association with other company wives, she was not gaining emotional support from the social relationships, lacked a sense of belonging, and felt irritated and frustrated. In this case, she lacked the three interacting protective factors, and her emotional state suffered. One participant’s narrative described her feelings of emptiness:

Up until I came here, I always belonged to somewhere; I was in school, I worked … I was a member of the company. So … belongingness, I always had a feeling that I belonged to somewhere. But I felt like I lost it, and I feel somewhat lonely since I came here … Like if we look at ourselves from our childhood … we have something … like we always have belonged to somewhere. So I thought I should be belonged to somewhere … like doing nothing but household chores, without working … felt that it was not acceptable for a person.

Risk factors

Risk factors for the participants were described as comprising five themes: uncertainty, uncontrollability, external constraints, self-criticism and excessive responsibility. The primary sources of uncertainty and uncontrollability were around aging, health problems, and their children’s future, which were common sources of anxiety and worry in these women’s lives. Constraints in the environment included limited opportunities, lack of community resources, cultural differences, and distant family connections. Self-criticism was described as a feeling of personal failure in the ability to negotiate problems or mobilize resources. Excessive responsibility was described as a strain or excessive burden, which did not allow time for any other pursuits. One woman expressed it this way:

I often tell my husband, “You and our daughter are contributing to the society, but I am not contributing anything to the society.” Because, I think our dog is the only thing that will be affected by my death. My husband will be affected, too. But it is only our dog and my husband. That’s why I think I am not contributing to the society. I believe it is important for human being to be needed by others.

Self-criticism often took the form of questioning who they were as people, especially when they were with other women. For example,

My core-self felt like it was swinging and it never stayed hold. It is hard to describe, but it was as if I were floating on the air. Because I did not have anything to hold onto, and so I was very easily persuaded.

Another stated the impact of this lack of self-confidence, by saying,

I think my feeling was that even if I was told something by others, I shouldn’t be affected, (and I came to believe) I’m weak. I got quite affected by other people. I wonder if this is why I end up thinking this way (negatively about myself). I should have had more self-confidence …

Another woman also focused on how her lack of self-confidence affected, and was accepted by, her relationships, saying,

I was not confident at all about myself. I did not even know if it was okay to make my own judgments. I was always not sure about my judgment, and therefore I always needed somebody to say it was okay to me. In other words, I think I could not live without depending on other people. In that sense, I was not standing on my own feet and I don’t think I was myself because of that.

Ikigai Balance

Ikigai

Ikigai arose from the balance between two core needs for fulfillment: individual fulfillment, which was experienced as personal growth; and social fulfillment, which was experienced as social responsibility or contributions to the family and society.

Individual fulfillment

Individual fulfillment was described as the personal growth as an individual woman, and was contrasted with personal growth that was related to social roles, such as being a mother or wife. This theme of individual fulfillment was evident in two ways: the feeling of independence, and the ability to explore life. Women described searching for an individual interest as a goal or ideal self-image, but one that would also be culturally approved. In their narratives, individual emotional independence, self-confidence, the ability to make autonomous decisions, and personal freedom or self-actualization were strong desires. One woman stated,

When I was really feeling confused and down, I thought that there should be something that I have to think deeply about. Like there are some direct causes, but I thought there is something else that I could do to make a difference. And I thought that I had to find it on my own, otherwise, I will have the same trouble over and over again from now on. So I think that I needed to think about it on my own.

Many participants expressed feelings of confusion, feeling down-hearted, or feeling impatient with themselves related to a reported lack of an inner sense of who they were. Some participants passively complained about a lack of opportunities for self-improvement and change regardless of how much they perceived that they enjoyed spending time in the United States:

I have fun hanging out with friends, and I can find things to enjoy, but I have often questioned what I am doing here … I felt empty. I think it was because I wasn’t working. It is like, I feel like there is nothing I should do, it’s like there is no thrill in life … And if we were staying here for a long time, then I would want to work someday. But I don’t know when. Yes, I sometimes feel anxious when I think about my future.

Individual growth and personal development were made meaningful through working outside of the home as a socially independent individual for many women. These women had feelings of anxiety, emptiness, and a lack of any joy or accomplishment related to the lack of a job. Confusion, jealousy, and anxiety arose from general feelings of a lack of self-growth. Women questioned why they were not independent, confident, and able to make their own decisions. In addition, instead of looking at the external reasons that limited their lives, these women tended to focus on an internal inadequacies and personal failures to actualize individual growth and development.

Social fulfillment

Social fulfillment included a sense of satisfaction with their devotion to their family and children. This theme was evident in three ways: feeling of self-worth, strong desires to be needed, and responsibility to lead their family and children to success. Some participants described desire to be needed by family members, developing closer relationships with family members, and having a feeling of security. The following quotes are from Japanese mothers who had adolescent children. The first excerpt is from the participant whose time was mostly occupied by the needs of her family members:

I know that my daughter is feeling constrained, but my time is also constrained by my children’s needs. In a sense, I do feel that I am needed. If we were in Japan, they could go wherever they needed to go by themselves. So, I didn’t have such a strong sense of being needed in Japan, but (here) I feel like I am contributing something.

This statement demonstrates that even though she had stress arising from a constraint on her time and the need to sacrifice her own desires, she gained some satisfaction about her life. This was because she felt that she had an important contribution to her children’s well-being. A different participant said,

I hope I am giving as much opportunity for my children to experience that which they can only experience here … Well this … is like fulfilling … Even when I find something tough, I can think positively and try to do my best for my child.

Both women gained feelings of self-worth and feeling needed through devoting their time and energy to their families. They also mentioned how much their relationship with their children and husband had become close and intimate since immigration.

Balanced Ikigai

Balanced Ikigai was the goal for the women, and women talked about their difficulties in balancing these two essential fulfillment needs. This difficulty arose when one need related to Ikigai dominated the other. Often, the need to contribute to the family and enact social roles predominated. Women perceived that their social and cultural expectations emphasized the role of the mother and wife rather than self-growth, especially in this immigration context. Some participants disclosed their feelings of selfishness and guilt by not prioritizing family and children but rather spending time for their enjoyment. This dilemma often generated feelings of regret, jealousy, anger, and confusion. One of the participants put it this way:

I thought it was the way it should be. I thought it was selfish if I (were to) behave as I am, so I tried to keep myself as low as possible and try to figure out what other people want of me, and behave accordingly.

Another respondent explained:

I think it is important for me to have a time for myself. But it is difficult for me to have my own time while my children are on summer break. I have to put myself aside, I mean, I think that it is important for me, at this point, to think about what I need to do and what things need to be done, rather than what I want to do … But I can’t think about those important things because of the roles that I need to fulfill. Right now, I am preoccupied with the things that I need to do, rather than what I want to do. Yes, and I cannot think about my life as objectively as I should be … I think that children and husbands have to suffer when mothers refuse some of their duties … It is not because my husband told me to be like that, it is just my nature that I cannot prioritize myself if anybody other than me is around … I think that my stress is a result of this inner conflict.

The first woman mentioned that she had been giving up opportunities for individual desires and the second one was confused about her life and emotionally stressed because of the unbalanced distribution between individual growth and contribution to others. Often, the contribution to others is more like a mission, obligation, or duty that is a culturally based expectation for some women. In an extreme case, one woman believed that the wife’s role is an obligation that has to be fulfilled even if it means sacrificing her health:

When I was (feeling) on the edge, I shouldn’t have pushed myself thinking about other people’s feelings. I really don’t like it, my heart, my body, it’s not something I want to do, but this time, “It can’t be helped, so there’s nothing I can do about it,” or “Well, this is something I have to do as my duty.”

Model of the Interactions Among Self-in-Context, Symptoms, Ikigai, and QOL

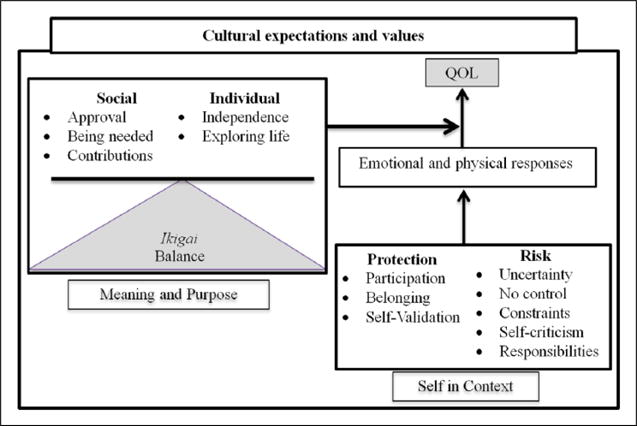

Figure 1 shows that cultural expectations and values, such as goals, standards, and rules of propriety, affect women’s ability access resources, mitigate exposure to risks, to balance fulfillments, and guide the evaluation of one’s success in negotiating the environment.

Figure 1.

Generic proposition.

For the women in this study, a person is a “self in context,” negotiating any situation using protective resources and/or being exposed to risks. This dynamic interaction fluctuates over time and in various situations. When women are successful, they experience positive emotions and a feeling of capacity. However, when women are unsuccessful, they may experience painful emotional or physical reactions. Ikigai is the result of balancing culturally and individually defined social and individual needs. Evaluation of QOL is not only based on both the success and failure of the self-in-context but also based on the overall success in balancing Ikigai fulfillments, and therefore mitigates the influence of physical and emotional reactions on QOL. This model provides hypotheses that can be tested quantitatively. Therefore, we tested the hypotheses that symptom level would be related to general risk and protective factors (for the full sample) and would be related to specific risk and protective phenomenon (in the subsample).

Quantitative Analysis Results

Entire Survey Sample

The mean age of participants was 39.61 ± 7.59 years (range = 21–57). The length of time participants have spent in the United States was 6.67 ± 7.55 years. The mean English fluency score was 14.22 ± 5.39 (range = 5–30). The perceived social support mean was 51.63 ± 10.59 (range = 0–64). The mean score of the CESD was 6.99 ± 8.06 (range = 0–41). The mean physical symptoms was 19.18 ± 18.65. There was a weak, significant inverse relationship between CESD and age (r = −.15, p = .05), CESD and social support (r = −.26, p= .01), and physical symptoms and social support (r = −.20, p = .01). There were no relationships among English fluency or length of time in the United States with CESD scores. Length of time abroad, age of children, income, and education did not show any significant relationships.

We operationalized the risk dimension described in the interviews as social stressors, using life event stressors involving family, friends, and community. We operationalized the protective factors described by the women in the interviews as perceived social support. We used t tests to examine the hypotheses that risks (operationalized as social stressors) would be related to higher symptoms and that protective factors (operationalized as perceived social support) would be related to lower symptoms. Twenty-six women (12.4%) were above the threshold for depressive symptoms and had higher social stressor means (M = 2.4, SD = 1.1) than those with below threshold means (M = 1.6, SD = 1.3), t(194) = −2.9, p = .00. The t tests also revealed that women who were above threshold for depressive symptoms had lower perceived social support means (M = 44.8, SD = 9.6) than those with below threshold means (M = 52.7, SD = 10.3), t(204) = 3.7, p = .00. Ninety-nine women (47.3%) were above threshold for physical symptoms and had higher social stressor means (M = 2.1, SD = 1.4) than those with below threshold means (M = 1.4, SD = 1.2), t(196) = −3.5, p = .00. There were no differences in mean social support for women above and below threshold for physical symptoms.

Interviewed Subsample

Analysis of the demographic data for the 25 women in the nested subsample revealed that age, length of time in the United States, or English fluency were not significantly different between the interviewed sample and rest of the survey sample. Only the CESD mean was significantly higher for the interviewed sample (M = 13.6, SD = 10.5) when compared with the rest of the survey sample (M = 6.1, SD = 7.2), t(203) = −4.5, p = .00.

To test the generic proposition for the interviewed subsample, we imported the qualitative code frequencies into the quantitative dataset, which transformed them from qualitative data into quantitative data. This transformation allowed us to look at associations among specific risk and protective factors and symptom level. Correlational analysis revealed that self-validation (protective factor) was highly and negatively correlated with physical symptoms (r = −.52, p = .02). There were no other significant associations among the risk and protective factors and symptoms.

We also used chi-square analyses to test whether risks were related to higher depressive and physical symptoms, and whether protective factors were associated with lower depressive and physical symptoms. There were no associations between depressive symptoms and any specific risk or protective factor. Only one risk factor (excessive responsibilities) was associated with higher physical symptoms (χ2 = 6.5, p = .02). Only one protective factor (self-validation) was related to lower physical symptoms (χ2 = 3.9, p = .05).

Discussion

The high levels of distress in Japanese samples we surveyed prompted this mixed-methods study. Our analyses found that a large proportion of the women in our study had high symptom burden and did not seek help. However, our CAB warned us not to make generalizations about the meaning of suffering in this population. They had counseled us that Japanese women evaluated their QOL in terms of their overall life goals. This prompted us to do this focused analysis of the meaning of symptoms in the women’s lives. The analyses presented here confirmed what we were told by the CAB: When a woman feels that she is fulfilling both her personal needs and her social responsibilities, her distress does not make her feel unwell.

The purpose of this study was to understand the meaning of distress. We found that meaning of life, or life purpose (Ikigai), was influenced by the cultural worldview, and that this meaning influenced QOL evaluation. This finding is consistent with the definition of QOL espoused by the WHO (1997), which states that QOL is an “individuals’ perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards, and concerns” (p. 1). This finding has implications for assessment of QOL and well-being, because these terms are often used interchangeably. For instance, well-being instruments are often used to measure “QOL” but examine concepts such as spiritual health, meaning, or life purpose, thus making it unclear whether QOL is the same as spiritual well-being, or whether they are related but distinct concepts. Our finding supports the latter, which is consistent with meta-analyses of this same question (Sawatzky, Ratner, & Chiu, 2005). Our participants helped us understand that cultural goals, life purpose, and meaning in life, mitigated their responses to their struggles and affected their overall health evaluation. QOL was framed within overall cultural learning, and was the successful engagement of a cultural self within a culturally construed context. This understanding has implications for counseling, nursing education, and intervention aimed at health promotion.

We found that achieving Ikigai is a meaning-level set of processes that have to do with culturally derived role expectations. This concept of Ikigai balance is similar to the idea of jiritsu, or socially sensitive independence, which is a maturation process developed in Japanese women that requires skillful negotiation of the expectations for the self and from others (Kamitani, 1996). As Kamitani notes, the achievement of balance between personal and social role expectation is likely to be a gendered phenomenon. It is possible that immigrant women (and men) face specific opportunities and challenges to achieve Ikigai balance depending on a variety of issues (i.e. visa status, regionality, immigrant community characteristics, age of children, income, and length of their time abroad). In our sample, critical immigration issues that interacted together included the community organization, visa restrictions, and the developmental phases of the women, as we have described elsewhere (Saint Arnault, 2002; Saint Arnault & Roels, 2012). However, in this study, we also identified that women needed skills to balance self and community expectations. Required skills included abilities to hold onto goals in the face of competing demands, to maintain self-identity in the face of community pressures, and to communicate needs and personal strengths effectively. Counseling for immigrant women can explore how women understand their distress and what aspects of their lives create risks or provide protections. Examination of risk factors such as uncertainty, uncontrollability, environmental constraints, excessive responsibilities and self-criticism may help women develop clarity, purpose, and a realistic attitude toward their ability to navigate the complexities immigrant life may pose. Next, helping women understand their overall meaning or purpose in their lives can have a protective impact.

The relationships among distress, meaning, QOL, and help seeking are beyond the scope of this study. We do know that Japanese women are less likely than White women to seek help for high levels of physical and emotional distress (Abe-Kim et al., 2007; Saint Arnault, 2002; Saint Arnault & Roels, 2012; Takeuchi, Hong, Gile, & Alegría, 2007; Takeuchi, Zane, et al., 2007; Williams, 2002). Previous research has shown that there are cultural and social factors besides distress level that can explain help seeking, such as emotional expression rules, fears about burdening others, and stigma related to emotional distress (Saint Arnault, 2009; Saint Arnault & Roels, 2012). This research adds to this science by illuminating how Japanese women view their symptoms as a reflection of a personal inability to mobilize resources or minimize risks in their daily lives, and they therefore find that they need to work harder to negotiate those factors. Therefore, women see the symptoms as a temporary condition that reflects their lack of skills, not something that requires professional help. This is a hypothesis that warrants further study; however, and if supported, has implications for interventions aimed at fostering help seeking among Japanese, Asian, and other immigrant women and men.

Ikigai seems to help Japanese women maintain their motivation during rough times, and frame their difficulties and successes related to either or both core themes of Ikigai, instead of the physical and emotional reactions. Ikigai was characterized by ongoing efforts to negotiate roles and relationships with the self, and was characterized by learning, a positive mental attitude, and being active in their lives. In this way, Ikigai, life purpose, or meaning in life may be a kind of lens or filter through which persons understand their lives and stresses at any given time, or make sense of what is happening to them. This finding is consistent with the suggestion from Hong regarding the moderating effects of meaning of life on the psychological well-being and stress (Hong, 2008). It is also consistent with research about Sense of Coherence, in which meaning is one component (Albertsen, Nielsen, & Borg, 2001; Antonovsky, 1987; Eriksson & Lindstrom, 2005). Purpose and meaning in life appears to be a transcultural protective factor.

This study may not be generalizable to all Japanese women for four reasons. First, Ikigai includes different themes, which depend on social contexts, life development, value, and age (Fujimoto et al., 2004; Hasegawa et al., 2003; So et al., 2004). More than a half of the participants in this study came to Michigan with their husbands who are working in automobile industries. These families spend about 5 years in Michigan and then go back to Japan. Most of the women also had similar social contexts such as social expectations of roles as a wife, living conditions, and the purpose of coming to the United States. These women may be different from Japanese people who live in Japan or Japanese people who immigrate. However, the results drawn from this study might be applicable to Japanese women who live in other areas in the United States for similar reasons. Therefore, the findings are descriptions, notions, or theories that may be applicable within specific contexts (Malterud, 2001). Second, we analyzed the Ikigai of the Japanese women who were highly distressed. It might be that non-distressed Japanese women have different Ikigai themes because they might be in dissimilar contexts, values, and life development. Third, this study mainly focused on Ikigai and health; thus, this article does not explain the details of the whole process displayed in Figure 1, such as the content of the Japanese cultural worldview, coping strategies, or perceptions of their role within the social networks. Finally, the women who engaged in the interviews self-selected based on unknown factors. Our research is well known within this Japanese community, and it is possible that some women who were highly distressed engaged in these interviews because they needed the self-understanding that women say they gain from the interviews. It is also possible, however, that some highly distressed women were unable to engage in the interview. We know that discussing mental health is highly stigmatized in this community, so we expect that much of our low interview agreement rate was related to that cultural dynamic. The issues with the stigma of mental health research and the difficulties in gaining large samples of Asians for research are consistent with other studies (Lee, Lei, & Sue, 2000).

Research on how immigrants understand and navigate changing social and economic circumstances has often focused on children or acculturation processes. This study examined the first-generation experience, which lays the foundation for subsequent acculturative processes. Cultural research also tends to emphasize interactions among immigrants with the host culture. This research demonstrates that intracultural relationships are also important. More research is needed to understand how immigrants experience distress, navigate hardships and identify culturally relevant strategies that can be used to help them mitigate stress and distress. For example, understanding the balance between social and self-fulfillments will help researchers develop interventions based within the cultural worldview, which may be superior to Western interventions developed for Western cultural goals, such as assertiveness, self-esteem, and self-actualization. This is in concert with the recommendation of Yoshihama and others that culturally relevant coping is the best approach. She found that battered Japanese women who used “active” coping (a preferred coping strategy in Western cultures) were more distressed than women who used “passive” strategies (Yoshihama, 2002).

This study contributes to the science of mixed-methods research, providing examples of how mixed research methods are complementary and can support new research models in nursing (Mendlinger & Cwikel, 2008). Specifically, the qualitative portion of this study helped clarify the findings from the survey data. For instance, our survey data revealed that 12% had high CESD and almost half had high physical symptoms, but asking them about the meaning of distress revealed that their understanding of distress relied on a culturally based analysis of their ability to navigate social context and meet life goals. Carrying out mixed-methods research has challenges, however, because the themes that emerged did not all have a quantitative equivalent, making hypothesis testing difficult. We were able to test general risk and protective factors; however, relationships among stress, social support, and distress are known. The hypothesis that Ikigai mediates the relationship between symptoms and QOL will be tested in future studies. We can also operationalize more culturally specific risk and protective variables such as perceived constraints, self-criticism, and control. For example, Sense of Coherence scale has both meaning and manageability dimensions (Albertsen et al., 2001; Antonovsky, 1987; Eriksson & Lindstrom, 2005) and could be measured along with QOL in subsequent studies.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was funded by the NIH Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences, the Office of Women’s Health, and the National Institute of Mental Health under grant number RO1MH071307.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Abe-Kim J, Takeuchi DT, Hong S, Zane N, Sue S, Spencer MS, Alegría M. Use of mental health-related services among immigrant and US-born Asian Americans: Results from the National Latino and Asian American Study. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97:91–98. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.098541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albertsen K, Nielsen ML, Borg V. The Danish psychosocial work environment and symptoms of stress: The main, mediating and moderating role of sense of coherence. Work & Stress. 2001;15:241–253. [Google Scholar]

- Antonovsky A. Unraveling the mystery of health How people manage stress and stay well. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Aoki K, Matsumoto K. Study of self-evaluation of health in elderly. Journal of Home Economics of Japan. 1994;45:105–114. [Google Scholar]

- Borgatti SP. Elicitation techniques for cultural domain analysis. In: Schensul JJ, LeCompte MD, Nastasi BK, Borgatti SP, editors. Enhanced ethnographic methods. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira; 1999. pp. 115–151. [Google Scholar]

- Canter D, Brown J, Groat L. A multiple sorting procedure for studying conceptual systems. In: Brenner M, Brown J, Canter D, editors. The research interview: Uses and approaches. London, England: Academic Press; 1985. pp. 79–114. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. Grounded theory. In: Emerson R, editor. Contemporary field research: Perspectives and formulations. Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland Press; 2001. pp. 335–352. [Google Scholar]

- Chiba M, Saito S. A research on the relationship between the Purpose in Life test (PIL) and Self-rating Depression Scale (SDS) Job Stress Research. 1998;5:154–159. [Google Scholar]

- Cho M, Nam J, Suh G. Prevalence of symptoms of depression in a nationwide sample of Korean adults. Psychiatry Research. 1998;81:341–352. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(98)00122-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen R, Bavishi C, Rozanski A. Purpose in life and its relationship to all-cause mortality and cardiovascular events: A meta-analysis. Circulation. 2015;131(Suppl 1):A52. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demura S, Kobayashi H, Kitabayashi T. QOL models constructed for the community-dwelling elderly with Ikigai (purpose in life) as a composition factor, and the effect of habitual exercise. Journal of Physiological Anthropology and Applied Human Science. 2005;24:525–533. doi: 10.2114/jpa.24.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson M, Lindstrom B. Validity of Antonovsky’s sense of coherence scale: A systematic review. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health. 2005;59:460–466. doi: 10.1136/jech.2003.018085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feder A, Ahmad S, Lee EJ, Morgan JE, Singh R, Smith BW, Charney DS. Coping and PTSD symptoms in Pakistani earthquake survivors: Purpose in life, religious coping and social support. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2013;147:156–163. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank G. Life history model of adaptation to disability: The case of a “congenital amputee”. Social Science & Medicine. 1984;19:639–645. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(84)90231-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankl VE. Man’s search for meaning. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser KD, Estabrooks C, Allen M, Strang V. Factors that influence case managers’ resource allocation decisions in pediatric home care: An ethnographic study. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2009;46:337–349. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto K, Okada K, Izumi T, Mori K, Yano E, Konishi M. Factors defining Ikigai of older adults who are living at home. Journal of Health and Welfare Statistics. 2004;51:24–32. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon EJ. Patients’ decisions for treatment of end-stage renal disease and their implications for access to transplantation. Social Science & Medicine. 2001;53:971–987. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00397-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gramling LF, Carr RL. Lifelines: A life history methodology. Nursing Research. 2004;53:207–210. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200405000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa A, Hujiwara Y, Hoshi T, Shinkai S. Regional differences in Ikigai in elderly people: Relationship between Ikigai and family structure, physiological situation and functional capacity. Nihon Rounen-igaku Zasshi. 2003;40:390–396. doi: 10.3143/geriatrics.40.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong L. College stress and psychological well-being: Self-transcendence meaning of life as a moderator. College Student Journal. 2008;42:531–541. [Google Scholar]

- Honma Y, Naruse Y, Kagamimori S. Physio-social activities and active life expectancy in Japanese elderly. Journal of Public Health. 1999;46:380–390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshino K, Yamada H, Endo T, Nakura E. Physio-social activities and active life expectancy, life expectancy in Japanese elderly. Japan Journal of Public Health. 1996a;46:380–390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshino K, Yamada H, Endo T, Nakura E. A preliminary study on Quality of Life Scale for elderly: An examination in terms of psychological satisfaction. Japanese Journal of Psychology. 1996b;67:134–140. doi: 10.4992/jjpsy.67.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang WC, Ting JY. Disaggregating the effects of acculturation and acculturative stress on the mental health of Asian Americans. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2008;14:147–154. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.14.2.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Japanese Investment Direct Survey. Japanese Direct Investment Survey: Summary of Michigan results. Detroit, MI: Consulate General of Japan in Detroit; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kamitani Y. The structure of jiritsu (socially sensitive independence) in middle-aged Japanese women. Psychological Reports. 1996;78:1355–1362. [Google Scholar]

- King LA, Hicks JA, Krull JL, Del Gaiso AK. Positive affect and the experience of meaning in life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2006;90:179–196. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.90.1.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Lei A, Sue S. The current state of mental health research on Asian Americans. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment. 2000;3:159–178. [Google Scholar]

- Lin E, Goering P, Offord DR, Campbell D, Boyle MH. Use of mental health services in Ontario: Epidemiological findings. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 1996;41:572–577. doi: 10.1177/070674379604100905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lofland J. Analytic ethnography: Features, failing, and futures. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography. 1995;24:30–67. [Google Scholar]

- Maeda D, Asano H, Taniguchi K. The subjective well-being of Japanese old people. Social Gerontology. 1979;11:15–31. [Google Scholar]

- Malterud K. Qualitative research: Standards, challenges, and guidelines. The Lancet. 2001;358:483–488. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05627-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKnight PE, Kashdan TB. Purpose in life as a system that creates and sustains health and well-being: An integrative, testable theory. Review of General Psychology. 2009;13:242–251. [Google Scholar]

- Mendlinger S, Cwikel J. Spiraling between qualitative and quantitative data on women’s health behaviors: A double helix model for mixed methods. Qualitative Health Research. 2008;18:280–293. doi: 10.1177/1049732307312392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mui AC, Suk-Young K. Acculturation stress and depression among Asian immigrant elders. Social Work. 2006;51:243–255. doi: 10.1093/sw/51.3.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mui AC, Suk-Young K, Chen LM, Domanski MD. Reliability of the Geriatric Depression Scale for use among elderly Asian Immigrants in the USA. International Psychogeriatrics. 2003;15:253–271. doi: 10.1017/s1041610203009517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neufeld A, Harrison MJ, Rempel GR, Larocque S, Dublin S, Stewart M, Hughes K. Practical issues in using a card sort in a study of nonsupport and family caregiving. Qualitative Health Research. 2004;14:1418–1423. doi: 10.1177/1049732304271228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noh S, Avison WR, Kaspar V. Depressive symptoms among Korean immigrants: Assessment of a translation of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies– Depression Scale. Psychological Assessment. 1992;4:84–91. [Google Scholar]

- Ohnishi H, Ibrahim FA. Cultural-specific counseling strategies for Japanese nationals in the United States of America. International Journal for the Advancement of Counseling. 1999;21:189–206. [Google Scholar]

- Oishi S, Diener E. Goals, culture, and subjective well-being. Personality Social Psychological Bulletin. 2001;27:1674–1682. [Google Scholar]

- Padilla AM, Sung H. The Stanford Foreign Language Oral Skills Evaluation Matrix (FLOSEM): A rating scale for assessing communicative proficiency. 1999 Retrieved from ERIC database. (ED445538) [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker JW. The psychology of physical symptoms. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart M, Sorensen S. Gender difference in self-concept and psychological well-being in old age: A meta-analysis. Journal of Gerontological Behavioral Psychological Science & Social Science. 2001;56:195–213. doi: 10.1093/geronb/56.4.p195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Ro M. Moving forward: Addressing the health of Asian American and Pacific Islander women. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92:516–519. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.4.516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saint Arnault DM. Help-seeking and social support in Japan Sojourners. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 2002;24:295–306. doi: 10.1177/01939450222045914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saint Arnault DM. The Japanese. In: Ember CR, Ember M, editors. Encyclopedia of medical anthropology. Vol. 1. New Haven, CT: Yale University; 2004. pp. 765–776. [Google Scholar]

- Saint Arnault DM. Cultural determinants of help seeking. Research and Theory for Nursing Practice. 2009;23:259–278. doi: 10.1891/1541-6577.23.4.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saint Arnault DM, Fetters MD. R01 funding for mixed methods research: Lessons learned from the mixed-method analysis of Japanese depression project. Journal of Mixed Methods Research. 2011;5:309–329. doi: 10.1177/1558689811416481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saint Arnault DM, Roels DJ. Social networks and the maintenance of conformity: Japanese sojourner women. International Journal of Culture and Mental Health. 2012;5:77–93. doi: 10.1080/17542863.2011.554030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saint Arnault DM, Shimabukuro S. The clinical ethnographic interview: A user-friendly guide to the cultural formulation of distress and help seeking. Transcultural Psychiatry. 2012;49:302–322. doi: 10.1177/1363461511425877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawatzky R, Ratner PA, Chiu L. A meta-analysis of the relationship between spirituality and quality of life. Social Indicators Research. 2005;72:153–188. [Google Scholar]

- Shibata H. Required to the elderly. Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Gerontology- Successful Aging. 1998;12:47–52. [Google Scholar]

- Shibusawa T, Mui A. Stress, coping, and depression among Japanese elders. Journal of Gerontological Social Work. 2001;36:63–81. [Google Scholar]

- Shimomura H. The career pictures of workers in their 50s: Considering adult career development using the life-line method. Japan Labor Review. 2011;8:89–104. [Google Scholar]

- Shirai K, Iso H, Fukuda H, Toyoda Y, Takatorige T, Tatara K. Factors associated with “Ikigai” among members of a public temporary employment agency for seniors (Silver human resources center) in Japan; gender differences. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2006;4:12. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-4-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- So J, Imu H, An S, Okada S, Shirasawa M. Factors associated with Ikigai among big-city dwelling older population who are living at home. Journal of Health and Welfare Statistics. 2004;51:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research. 1st. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ta VM, Hayes D. Racial differences in the association between partner abuse and barriers to prenatal health care among Asian and Native Hawaiian/other Pacific Islander women. Maternal Child Health Journal. 2010;14:350–359. doi: 10.1007/s10995-009-0463-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ta VM, Juon H, Gielen AC, Steinwachs DM, Duggan A. Disparities in use of mental health and substance abuse services by Asian and Native Hawaiian/other Pacific Islander women. Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research. 2007;35:20–36. doi: 10.1007/s11414-007-9078-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taguchi R, Yamazaki Y, Takayama T, Saito M. Life-lines of relapsed breast cancer patients: A study of post-recurrence distress and coping strategies. Japanese Journal of Health and Human Ecology. 2008;74:217–235. [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi D, Chung RCY, Lin KM, Shen H, Kurasaki K, Chun CA, Sue S. Lifetime and twelve-month prevalence rates of major depressive episodes and dysthymia among Chinese Americans in Los Angeles. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1998;155:1407–1414. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.10.1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi D, Hong S, Gile K, Alegría M. Developmental contexts and mental disorders among Asian Americans. Research in Human Development. 2007;4:49–69. doi: 10.1080/15427600701480998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi D, Zane N, Hong S, Chae DH, Gong F, Gee GC, Alegría M. Immigration-related factors and mental disorders among Asian Americans. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97:84–90. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.088401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. The Asian population: 2000. Washington, DC: Author; 2002. Feb, Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/prod/2002pubs/c2kbr01-16.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Weinert C, Brandt PA. Measuring social support with the Personal Resource Questionnaire. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 1987;9:589–602. doi: 10.1177/019394598700900411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR. Racial/ethnic variations in women’s health: The social embeddedness of health. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92:588–597. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.4.588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. WHOQOL: Measuring quality of life. Geneva, Switzerland: Programme on Mental Health, Division of Mental Health and Prevention of Substance Abuse; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Women’s mental health: An evidence based review in mental health determinants and populations. Geneva, Switzerland: Department of Mental Health and Substance Dependence; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida K. The significance and characteristics of an IKIGAI scale in senior high school students. Japan Society of Psychosomatic Medicine (Shinshin-Igaku) 1994;34:481–487. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshihama M. Battered women’s coping strategies and psychological distress: Differences by immigration status. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2002;30:429–452. doi: 10.1023/A:1015393204820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zilioli S, Slatcher RB, Ong AD, Gruenewald T. Purpose in life predicts allostatic load ten years later. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2015;79:451–457. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2015.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]