Abstract

Background

Assessing health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in patients with heart failure (HF) are important goals of clinical care and HF research. We sought to investigate ethnic differences in perceived HRQoL and its association with mortality among patients with HF and left ventricular ejection fraction ≤35%, controlling for demographic characteristics and HF severity.

Methods and results

We compared 5,697 chronic HF patients of Indian (26%), White (23%), Chinese (17%), Japanese/Koreans (12%), Black (12%), and Malay (10%) ethnicities from the HF-ACTION and ASIAN-HF multinational studies using the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ; range 0–100; higher scores reflect better health status). KCCQ scores were lowest in Malay (58±22) and Chinese (60±23), intermediate in Black (64±21) and Indian (65±23), and highest in White (67±20) and Japanese or Korean patients (67±22), after adjusting for age, sex, educational status, HF severity and risk factors. Self-efficacy, which measures confidence in the ability to manage symptoms, was lower in all Asian ethnicities (especially Japanese/Koreans [60±26], Malay [66±23] and Chinese [64±28]) compared to Black (80±21) and White (82±19) patients, even after multivariable adjustment (p<0.001). In all ethnicities, KCCQ strongly predicted 1-year mortality (HR 0.45, 95% CI 0.30–0.67 for highest vs lowest quintile of KCCQ; p for interaction by ethnicity 0.101).

Conclusions

Overall, HRQoL is inversely and independently related to mortality in chronic HF, but is not modified by ethnicity. Nevertheless, ethnic differences exist independent of HF severity and comorbidities. These data may have important implications for future global clinical HF trials that use patient-reported outcomes as endpoints.

Clinical Trial Registration

Keywords: patient-reported outcomes, health status, quality of life, international variation, Asia, ethnic variation

Multinational clinical trials increasingly incorporate patient-reported health status among clinical endpoints.1–3 In heart failure (HF), where patients may experience significant impairments in health status, disease- and health-related quality of life (HRQoL) is an important patient-centered clinical outcome.4 HRQoL as it relates to health encompasses broad concepts of physical and social functioning, mental and general health, as well as overall perceptions of energy or vitality, pain, and cognitive function. Adding to the complexity, these factors can be influenced by varying personal values, preferences, and motivation, as well as available psychological and social support.5 In clinical trials, these endpoints measure outcomes important to patients not otherwise captured by traditional clinical or process outcomes.

In HF, the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ) is one of the most commonly used and rigorously studied instruments for quantifying HRQoL. It has been validated in multiple HF-related disease states, and prior research has also shown that baseline HRQoL measured by the KCCQ predicts HF prognosis. 6–11 However, little is known regarding variation in HRQoL across different ethnic groups, especially among patients from different Asian countries compared to North America and Europe. As such, we aimed to investigate the ethnic differences in perceived health status among patients with chronic HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) in a combined international cohort from Asia, North America, and Europe.

Methods

For the current analysis, we combined the participants from Heart Failure: A Controlled Trial Investigating Outcomes in Exercise Training (HF-ACTION, N=1998) and the Asian Sudden Cardiac Death in Heart Failure (ASIAN-HF) registry (N=3699) with left ventricular ejection fraction (EF) ≤ 35% to form a combined cohort of 5,697 patients. The trial design and results of HF-ACTION have been previously reported.12, 13 This multi-center, randomized controlled trial compared the long-term safety and efficacy of exercise training plus evidence-based HF medical therapy versus medical therapy alone in patients with HFrEF (EF ≤ 35%) and New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class II to IV symptoms. Between April 2003 and February 2007, patients were recruited from 82 centers in the United States, Canada, and France. Patients were excluded if they had comorbidities or limitations that precluded exercise training or major cardiovascular events or procedures within 6 weeks prior to enrollment or planned within 6 months after enrollment. Follow-up occurred over a median of 2.6 years. For the current analysis, patients who did not self-identify as White or Black or African American were excluded (N=121). The protocol was approved by the institutional review board or ethics committee at each institution and the coordinating center. All patients provided written informed consent.

The design of the ASIAN-HF registry has also been previously reported.14 In brief, the ASIAN-HF is a prospective observational registry of HF patients from 11 Asian regions (China, Hong Kong, India, Indonesia, Japan, Korea, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, Taiwan, and Thailand) that enrolled patients between 2010 and 2015. The registry aims to phenotype HF within Asia and provide unique opportunities to improve care and outcomes. Following informed consent, consecutive patients were recruited at 46 sites with HF with EF ≤ 40% and a history of being hospitalized or treated in an ambulatory setting for decompensated HF in the prior 6 months. Patients were excluded if they had primary cardiac valvular disease or other life-threatening comorbidities with life expectancy of <1 year. The subset of patients with EF ≤ 35% were included in the current analysis. All patients underwent standardized clinical assessment, electrocardiography, and echocardiography by protocol. Outcomes were adjudicated by an independent clinical events committee. Ethics approvals were obtained from the relevant human ethics committees at all sites.

Regional and ethnic groups were defined by participant-reported ethnicity at the time of enrollment and—from HF-ACTION—divided into White (N=1324), Black or African American (N=674), and—from ASIAN-HF (restricted to LVEF ≤35%)—divided into Chinese (N=973), Indian (N=1448), Malay (N=590), and Japanese/Korean (N=688). Ethnic groups may include individuals of differing nationality (Table 1). For example, Chinese ethnicity included patients enrolled from China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Singapore, Malaysia, and Indonesia; Indian ethnicity from India, Singapore, and Malaysia; and Malay ethnicity from Indonesia, Malaysia, and Singapore. Japanese and Korean patients within ASIAN-HF were analyzed together due to limited numbers, regional proximity, and similarities in their clinical characteristics based on our prior work.15

Table 1.

Distribution of Study Cohort Country of Origin and Ethnicity (N=5,697)

| Country of Origin | Patient Identified Ethnicity

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whites | Blacks | Indians | Malays | Chinese | Japanese/Korean | Total | |

| China | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 374 | 0 | 374 |

| Hong Kong | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 39 | 0 | 39 |

| India | 0 | 0 | 1,312 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1,312 |

| Indonesia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 218 | 9 | 0 | 227 |

| Japan | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 429 | 430 |

| Korea | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 259 | 260 |

| Malaysia | 0 | 0 | 78 | 202 | 102 | 0 | 382 |

| Philippines | 0 | 0 | 0 | 31 | 0 | 0 | 31 |

| Singapore | 0 | 0 | 58 | 139 | 255 | 0 | 452 |

| Taiwan | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 192 | 0 | 192 |

| Canada | 160 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 167 |

| France | 70 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 75 |

| United States | 1,094 | 662 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1,756 |

|

| |||||||

| Total | 1,324 | 674 | 1,448 | 590 | 973 | 688 | 5,697 |

Health status was measured using the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ), a 23-item self-administered HF-specific questionnaire validated in multiple HF-related disease states.6–9 This instrument has been widely used in recent international HF clinical trials and has been validated in several languages.16–22 The KCCQ is scored from 0 to 100; higher scores represent better health status. In addition to an overall score, the KCCQ can be divided into sub-scores for physical limitation, symptoms, self-efficacy, quality of life, and social limitations. In both HF-ACTION and ASIAN-HF, the self-administered KCCQ at the baseline clinic visit was used in this analysis. Non-English speaking participants used certified versions of the KCCQ translated into their native languages.

Baseline characteristics of the ethnic groups are presented as frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and as mean (SD) or median (IQR) for continuous variables. We compared differences by ethnic groups using analysis of variance for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables. To test the association of baseline characteristics with KCCQ score, we constructed unadjusted and adjusted general multivariable linear regression models for each characteristic. We used a log-rank test to evaluate differences in survival and Cox proportional hazards analysis to compare survival for patients grouped by KCCQ quintile while adjusting for baseline characteristics (age, sex, ethnicity, NYHA class, education). We performed analyses only on complete cases and omitted those with missing values. For these post-hoc analyses, we considered two-sided p values with significant defined as p<.05 without adjustment for multiplicity of testing. SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc.) was used for all analyses. No extramural funding was used to support this work. The authors are solely responsible for the design and conduct of this study, all study analyses, the drafting and editing of the paper and its final contents.

Results

In the combined cohort of 5,697 participants, the median age was 60 (IQR 51–68) years and 24% were women; baseline characteristics of the cohort by ethnicity are shown in Table 2. In general, disease characteristics and comorbidities varied among the ethnic groups. Black or African American (median age 55) and Malay participants (median age 56) were the youngest, while White (median age 62) and Japanese/Korean (median age 67) participants were the oldest. Malay participants had the highest prevalence of diabetes (48%), chronic kidney disease (57%), and ischemic etiology of HF (69%), despite being younger than other Asian ethnic groups. While use of mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRA) was generally higher among the Asian ethnic groups compared to White and Black or African American participants (56–67% vs. 43–51%, respectively), use of beta-blockers and ACE-inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blockers (ACEI/ARB) were lower in Asian cohorts (Table 2). Ethnic Malay and Indian participants also reported the lowest percentage of ‘any college education’ versus other groups (22–23% vs. 30–61%). Other differences in social history are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Baseline Characteristics of Regional/Ethnic Groups (N=5,697)

| Characteristic | White | Black or African American | Indian | Malay | Chinese | Japanese & Koreans | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=1,324 | N=674 | N=1,448 | N=590 | N=973 | N=688 | ||

| Age, median (IQR),)y | 61.7 (54.3–70.1) | 54.9 (46.8–63.9) | 59 (51–66) | 56 (49–63) | 62 (52–70) | 67 (54.5–75) | <0.001 |

| Men (%) | 79.1 | 60.7 | 76 | 80.5 | 81.0 | 73.7 | <0.001 |

| NYHA classification (%) (N=5692) | <0.001 | ||||||

| * Class I/II | 63.4 | 60.1 | 54.7 | 58.2 | 45.3 | 61.3 | |

| * Class III/IV | 36.6 | 39.9 | 31.9 | 37.4 | 46.9 | 27.5 | |

| * Not assessed | 0 | 0 | 13.5 | 4.4 | 7.8 | 11.2 | |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction, mean (SD), (%) | 24 (6.1) | 24 (6.4) | 27 (5.6) | 24 (6.3) | 26 (6.3) | 26 (6.5) | <0.001 |

| Ischemic etiology (%) (N=5469) | 61.6 | 33.1 | 42.9 | 69.4 | 45.5 | 31.8 | <0.001 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg, mean (SD) (N=5663) | 113 (18) | 116 (19) | 116 (18) | 122 (22) | 120 (20) | 114 (19) | <0.001 |

| Heart rate, bpm, mean (SD) (N=5664) | 71 (11) | 72 (12) | 81 (15) | 83 (18) | 80 (17) | 77 (16) | <0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) (N=5494) | 30.1 (6.2) | 33.1 (8.4) | 25.0 (4.9) | 25.8 (5.8) | 24.6 (4.9) | 23.2 (4.1) | <0.001 |

| Serum creatinine, mg/dL, mean (SD) (N=4668) | 1.36 (0.9) | 1.34 (0.7) | 1.26 (0.8) | 1.59 (1.6) | 1.38 (1.1) | 1.41 (1.4) | <0.001 |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | |||||||

| * Diabetes (N=5684) | 388 (29.3) | 242 (35.9) | 584 (40.3) | 278 (47.7) | 369 (38.0) | 221 (32.4) | <0.001 |

| * Atrial fibrillation/flutter (N=5685) | 327 (24.7) | 96 (14.2) | 64 (4.4) | 78 (13.4) | 238 (24.5) | 249 (35.9) | <0.001 |

| * Hypertension (N=5672) | 668 (50.8) | 510 (76.0) | 586 (40.5) | 342 (58.7) | 529 (54.4) | 328 (48.0) | <0.001 |

| * Stroke (N=5685) | 100 (7.6) | 109 (16.2) | 30 (2.1) | 39 (6.7) | 68 (7.0) | 69 (10.1) | <0.001 |

| * COPD (N=5669) | 161 (12.3) | 54 (8.1) | 73 (5.0) | 51 (8.8) | 102 (10.5) | 62 (9.1) | <0.001 |

| * Chronic kidney disease (N=4656) | 604 (51.7) | 214 (34.6) | 354 (37.3) | 258 (57.2) | 358 (43.1) | 267 (41.8) | <0.001 |

| * Smoking history (N=5677) | 891 (67.5) | 381 (56.9) | 313 (21.6) | 346 (59.3) | 530 (54.5) | 364 (53.4) | <0.001 |

| * Alcohol intake, Yes (N=5652) | 595 (45.5) | 243 (37.0) | 251 (17.3) | 73 (12.4) | 332 (34.1) | 309 (45.3) | <0.001 |

| Educational status, n (%) | <0.001 | ||||||

| * Less than high school | 158 (11.9) | 93 (13.8) | 408 (28.2) | 147 (24.9) | 358 (37.0) | 118 (18.1) | |

| * High school or equivalent | 326 (24.6) | 234 (34.7) | 444 (30.7) | 284 (48.1) | 372 (38.5) | 218 (33.4) | |

| * Some college/associate degree/diploma | 446 (33.7) | 229 (34.0) | 177 (12.2) | 68 (11.5) | 150 (15.5) | 100 (15.3) | |

| * Degree or higher | 359 (27.1) | 106 (15.7) | 371 (25.6) | 70 (11.9) | 63 (6.5) | 186 (23.5) | |

| * Decline to respond/nil | 35 (2.6) | 12 (1.8) | 48 (3.3) | 21 (3.6) | 24 (2.5) | 30 (4.6) | |

| Medications, n (%)() (N=5543) | |||||||

| * Beta-blockers | 1244 (94.0) | 645 (95.7) | 937 (68.3) | 415 (74.6) | 789 (83.8) | 579 (85.8) | <0.001 |

| * ACE inhibitors/Angiotensin receptor blockers | 1236 (93.4) | 639 (94.8) | 1050 (76.5) | 428 (77.0) | 640 (67.9) | 564 (85.6) | <0.001 |

| * Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists | 575 (43.4) | 340 (50.5) | 833 (60.7) | 310 (55.8) | 627 (66.6) | 390 (57.8) | <0.001 |

| * Diuretics | 998 (75.4) | 565 (83.8) | 1106 (80.6) | 483 (86.9) | 769 (81.6) | 541 (80.2) | <0.001 |

| All-Cause Mortality, n (%) | 57 (4.3) | 42 (6.2) | 107 (8.3) | 70 (17.4) | 116 (13.7) | 27 (4.8) | <0.001 |

Table 3 summarizes the patient-reported KCCQ scores and domain specific sub-scales by ethnic group. Across all ethnicities, lower KCCQ scores were associated with female sex, NYHA class III/IV symptoms, higher pulse rate, chronic kidney disease, prescription of diuretics, lack of ACEI/ARB and beta-blocker use, and lack of college degree (p<0.01). Ethnic Malay and Chinese participants had lower KCCQ overall summary scores (58–60 vs. 63–67; Malay, Chinese vs. all others) and overall quality of life despite experiencing fewer symptoms and social limitation compared to other ethnicities (Table 3). After adjustment for multiple covariates (age, gender, NYHA class, education, marital status, diabetes, atrial fibrillation, ACEI/ARB, beta-blockers, MRAs, and diuretics), ethnic Malay participants maintained an almost 10-point lower overall KCCQ summary score compared to White participants (57 vs. 66, respectively). White and Japanese/Korean participants had the highest adjusted overall scores and highest sub-scores across nearly all of the sub-scales. In multivariable regression, ethnicity predicted KCCQ overall scores, independent of NYHA class (p<0.001).

Table 3.

Baseline Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ) Results (Unadjusted) by Ethnicity (N=5,490)

| Ethnic groups

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whites N= 1324 |

Blacks N=674 |

Indians N=1448 |

Malays N=590 |

Chinese N=973 |

Japanese & Koreans N=688 |

p-value | |

| KCCQ Overall summary score, mean (SD) | 67.4 (19.9) | 63.5 (21.4) | 64.8 (22.5) | 57.6 (22.4) | 60.1 (23.1) | 67.3 (22.4) | <0.001 |

| KCCQ subscales, mean (SD) | |||||||

| Physical limitation | 70.9 (20.6) | 66.3 (23.5) | 65.9 (24.1) | 62.4 (26.2) | 67.0 (26.5) | 71.7 (25.6) | <0.001 |

| Total symptom score | 73.9 (19.9) | 70.9 (22.4) | 70.3 (24.0) | 60.2 (27.6) | 65.7 (25.7) | 76.5 (23.9) | <0.001 |

| Self-efficacy | 82.3 (19.2) | 79.8 (21.1) | 68.1 (29.5) | 65.6 (22.5) | 63.7 (28.0) | 59.9 (26.0) | <0.001 |

| Quality of life | 61.0 (24.3) | 56.9 (25.0) | 59.3 (27.4) | 52.9 (21.6) | 49.9 (24.9) | 58.1 (24.9) | <0.001 |

| Social limitation | 63.7 (26.7) | 59.4 (28.3) | 63.6 (32.4) | 54.5 (30.3) | 56.6 (31.6) | 61.5 (34.1) | <0.001 |

Self-efficacy, which measures confidence in the ability to self-manage symptoms, was highest among White and Black or African American participants (80–82 vs. 60–68, White and Black or African American vs. all others). However, despite having one of the highest overall KCCQ score and the lowest symptom burden and physical limitation, the combined Japanese and Korean cohort reported the lowest self-efficacy score (60 vs. 64–82, Japanese/Korean vs. all others). This trend persisted after adjustment for clinical covariates (p<0.001). In fact, all Asian ethnic groups reported 10–20 point lower self-efficacy scores compared to White and Black or African American participants. In multivariable modeling, ethnicity was the strongest predictor of self-efficacy scores (p<0.001).

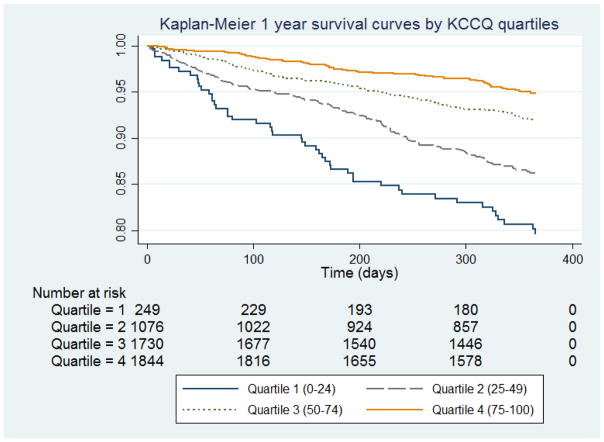

There were 420 (8.2%) participants in the combined cohort that died during the first year of follow up. Ethnic differences in mortality were observed, with mortality at one year approaching 18% in Malay, compared to 4.3% in White participants. In the entire group, mortality increased with decreasing KCCQ score quartile (Figure 1). When compared to those with the lowest KCCQ scores (Quartile 1), those with a score of 75–100 (Quintile 4) were 49% less likely to die in the first year (adjusted HR 0.51, 95% CI 0.34–0.76, p<0.001). The association of KCCQ overall score with 1-year mortality was not modified by ethnicity (pinteraction=0.10). In multivariable proportional hazards analysis, the KCCQ score remained predictive of one-year mortality after adjustment for clinical characteristics (Table 4). Asian ethnicity, older age, NYHA class III/IV HF, lower LVEF, lower systolic blood pressure, peripheral vascular disease, and lack of ACEI/ARB and beta-blockers were also associated with worse mortality (p<0.01).

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier 1-year survival curves by KCCQ quartiles

Table 4.

Association of Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ) score with 1-Year Mortality: Multivariable Adjustment

| Hazard Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 (adjustment for ethnicity) | |||

| KCCQ score (REF 0 – 24 Quartile 1) | |||

| 25–49 (Quartile 2) | 0.72 | 0.51–0.99 | 0.046 |

| 50 – 74 (Quartile 3) | 0.43 | 0.31–0.60 | <0.001 |

| 75 – 100 (Quartile 4) | 0.28 | 0.20–0.40 | <0.001 |

| Ethnicity (REF White participants) | |||

| Black | 1.34 | 0.90–2.00 | 0.147 |

| Indian | 2.16 | 1.56–2.98 | <0.001 |

| Malay | 4.21 | 2.95–6.00 | <0.001 |

| Chinese | 3.31 | 2.40–4.56 | <0.001 |

| Japanese/Koreans | 1.13 | 0.70–1.82 | 0.607 |

| Model 2 (adjustment for ethnicity and clinical variables*) | |||

| KCCQ score (REF 0 – 24 Quartile 1) | |||

| 25 – 49 (Quartile 2) | 0.88 | 0.62–1.25 | 0.479 |

| 50 – 74 (Quartile 3) | 0.65 | 0.46–0.94 | 0.023 |

| 75 – 100 (Quartile 4) | 0.51 | 0.340–0.76 | <0.001 |

| Ethnicity (REF White participants) | |||

| Black | 1.76 | 1.15–2.69 | 0.009 |

| Indian | 2.33 | 1.60–3.38 | <0.001 |

| Malay | 4.27 | 2.83–6.42 | <0.001 |

| Chinese | 3.09 | 2.14–4.46 | <0.001 |

| Japanese/Koreans | 1.12 | 0.67–1.89 | 0.656 |

The following clinical variables were tested and included in the model: age, sex, diabetes, hypertension, systolic blood pressure, ejection fraction, NYHA functional class III/IV vs. I/II, obstructive pulmonary disease, atrial fibrillation or flutter, peripheral vascular disease, coronary artery disease, educational status, ACEI/ARB, beta-blockers, diuretics.

Discussion

To our knowledge, these data represent the largest analysis of cross-continental ethnic differences in HRQoL among patients with chronic HF. Despite acknowledgement of the large and growing global public health burden of HF, substantial knowledge and care gaps exist, especially among low- and middle-income regions of Asia, where resources are particularly limited.23, 24 In this study, we show that—independent of clinical covariates—HRQoL as defined by the patient’s KCCQ score is significantly different among White, Black or African American, Indian, Chinese, Malay, or Japanese/Korean patients with HF across Asia, North America, and France. In general, ethnic Malay participants reported the worst health status, with the most physical limitations and highest quantity of symptoms. We also show that lower KCCQ scores are associated with worse one-year mortality, but that ethnicity does not modify this relationship These results extend prior analyses of North American outpatients and international clinical trial participants—describing the association of KCCQ scores with survival and hospitalization and racial differences in KCCQ scores—to HF patients in Asia.10, 11, 25 Our findings increase the generalizability of the inverse association between KCCQ and risk of mortality across ethnicities.

Patient-derived outcomes serve as an important endpoint in HF, a disease where functional status and quality of life remain valuable markers of well-being and an outcome important to patients. As symptom relief remains an important goal of HF therapy—and to support claims in product labeling, clinical trials now increasingly use patient-reported outcomes as study endpoints.1, 2, 10, 26, 27 The trend is mirrored in the recognition from United States regulatory agencies of the importance of patient-centered outcomes.28 Furthermore, patient-reported outcomes are increasingly being assessed in the clinical care setting, to risk stratify patients as well as individualize prognostic information.11 However, as our study demonstrates, different ethnic groups may respond differently to health status questionnaires, independent of routine markers of disease severity. While we cannot make conclusions regarding ethnic differences in HRQoL in response to a specific therapy, future international clinical studies should nevertheless take the baseline differences observed in this study into consideration when designing future studies assessing patient-reported endpoints.

Interestingly, we identified that the self-efficacy scale—a measure of confidence in the ability to self-manage symptoms—was significantly lower in Asians compared to White and Black participants from North America and France. The reasons underlying these differences are not completely understood in our current analysis. Differences in background education may explain some of the variation; ethnic Malay and Chinese participants reported the lowest levels of college education. However, cultural differences in the approach to healthcare or disparities in access to disease-related educational resources may be additional mediators, particularly for the Japanese and Korean participants. They reported almost 40% college education but significantly limited confidence about managing their HF symptoms. Empowering these patients with further tools to understand and treat their disease may improve certain components of their quality of life, but prior research has been limited.29, 30

Alternatively, different cultures may set different priorities for disease self-reliance and self-management. It is important to note that these same Asian patients reported greater quality of life comparable to their North American counterparts. Taken together, these findings may have different interpretations. For ethnicities with the lowest self-efficacy scores (Chinese and combined Japanese/Korean participants), measuring knowledge on self-disease management may not be an important component for overall quality of life. Our analysis cannot explain the cultural relevancy of measures like self-efficacy, and further research will be needed to understand which health status measures represent important components of well-being for all HF patients worldwide. To truly prioritize patient-centered goals of therapy, our study highlights the need for a more nuanced understanding of patient goals in different ethnic and cultural settings.

Our study has several limitations. We combined a clinical trial population with HF patients enrolled in an observational registry. As such, different means of selection bias apply to both groups of patients, and comparisons made between these groups must be interpreted in this context. For example, women represented only 24% of our combined sample. Nevertheless, we believe several factors support the validity of our results. First, our sample is representative of real world HF patients. While the median age in our combined cohort was only 60 years—more than 5 years younger than a contemporary European registry of acute and chronic HF patients—their unadjusted one-year mortality is comparable to that described in the same registry.31 Second, our combined data recapitulates the same inverse relationship between KCCQ and mortality presented in several prior studies.10, 11, 32 Lastly, all KCCQ measurements were taken at baseline, and active trial participation is unlikely to have influenced KCCQ comparisons. Additionally, a large meta-analysis in oncology has disputed the so-called “trial effect”—the widespread belief that patients in clinical trials have better outcomes than those who do not enroll.33

Our analysis is further limited by complex interrelationship of culture, history, race, and geopolitical identity as it relates to ethnicity and health. Ethnicity is self-identified, crossing political and cultural borders that may equally confound risk. While we adjusted for some important covariates of disease and patient risk, there remain unmeasured confounders that could predict an ethnic group’s average KCCQ score. For example, knowledge of a participant’s relative socioeconomic status as it relates to his regional income level may have reduced bias but was not available in our study. Notwithstanding these factors, as the largest trans-continental analysis of HF-specific health status to date, our study provides the foundation to further investigate and understand these differences.

Our study found significant heterogeneity in HRQoL among patients with HF of different ethnic groups in Asia, North America, and France, even after accounting for severity of HF and clinical comorbidities. In all ethnic groups, a low KCCQ score was independently associated with increased mortality at 1 year. These data may have important implications for the design of future global clinical HF trials that administer and interpret patient-reported outcomes as endpoints.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Health-related quality of life differs significantly among different ethnic groups.

A low KCCQ score was independently associated with increased mortality at 1 year.

These data should inform how we administer and interpret patient-reported outcomes.

Acknowledgments

We thank all investigators and participants of HF-ACTION and ASIAN-HF for their contribution.

Sources of Funding: The ASIAN-HF study is supported by grants from Boston Scientific Investigator Sponsored Research Program, National Medical Research Council of Singapore, A*STAR Biomedical Research Council ATTRaCT program, and Bayer. The HF-ACTION trial was supported by grants from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (USA); NCT00047437)

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors report no relevant disclosures.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Konstam MA, Gheorghiade M, Burnett JC, Jr, Grinfeld L, Maggioni AP, Swedberg K, et al. Effects of oral tolvaptan in patients hospitalized for worsening heart failure: the EVEREST Outcome Trial. JAMA. 2007;297(12):1319–31. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.12.1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Flynn KE, Pina IL, Whellan DJ, Lin L, Blumenthal JA, Ellis SJ, et al. Effects of exercise training on health status in patients with chronic heart failure: HF-ACTION randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;301(14):1451–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Food Drug Administration Center for Drugs Evaluation Research. Guidance for Industry: Patient-Reported Outcome Measures: Use in Medical Product Development to Support Labeling Claims. FDA; Maryland: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kelkar AA, Spertus J, Pang P, Pierson RF, Cody RJ, Pina IL, et al. Utility of Patient-Reported Outcome Instruments in Heart Failure. JACC Heart Fail. 2016;4(3):165–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2015.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilson IB, Cleary PD. Linking clinical variables with health-related quality of life. A conceptual model of patient outcomes. JAMA. 1995;273(1):59–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Green CP, Porter CB, Bresnahan DR, Spertus JA. Development and evaluation of the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire: a new health status measure for heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35(5):1245–55. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00531-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pettersen KI, Reikvam A, Rollag A, Stavem K. Reliability and validity of the Kansas City cardiomyopathy questionnaire in patients with previous myocardial infarction. Eur J Heart Fail. 2005;7(2):235–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2004.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ortega T, Diaz-Molina B, Montoliu MA, Ortega F, Valdes C, Rebollo P, et al. The utility of a specific measure for heart transplant patients: reliability and validity of the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire. Transplantation. 2008;86(6):804–10. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e318183eda4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joseph SM, Novak E, Arnold SV, Jones PG, Khattak H, Platts AE, et al. Comparable performance of the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire in patients with heart failure with preserved and reduced ejection fraction. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6(6):1139–46. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.113.000359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Soto GE, Jones P, Weintraub WS, Krumholz HM, Spertus JA. Prognostic value of health status in patients with heart failure after acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2004;110(5):546–51. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000136991.85540.A9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heidenreich PA, Spertus JA, Jones PG, Weintraub WS, Rumsfeld JS, Rathore SS, et al. Health status identifies heart failure outpatients at risk for hospitalization or death. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47(4):752–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O’Connor CM, Whellan DJ, Lee KL, Keteyian SJ, Cooper LS, Ellis SJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of exercise training in patients with chronic heart failure: HF-ACTION randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;301(14):1439–50. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Whellan DJ, O’Connor CM, Lee KL, Keteyian SJ, Cooper LS, Ellis SJ, et al. Heart failure and a controlled trial investigating outcomes of exercise training (HF-ACTION): design and rationale. Am Heart J. 2007;153(2):201–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2006.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lam CS, Anand I, Zhang S, Shimizu W, Narasimhan C, Park SW, et al. Asian Sudden Cardiac Death in Heart Failure (ASIAN-HF) registry. Eur J Heart Fail. 2013;15(8):928–36. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hft045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lam CS, Teng TK, Tay WT, Anand I, Zhang S, Shimizu W, et al. Regional and ethnic differences among patients with heart failure in Asia: the Asian sudden cardiac death in heart failure registry. Eur Heart J. 2016 doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pieske B, Maggioni AP, Lam CSP, Pieske-Kraigher E, Filippatos G, Butler J, et al. Vericiguat in patients with worsening chronic heart failure and preserved ejection fraction: results of the SOluble guanylate Cyclase stimulatoR in heArT failurE patientS with PRESERVED EF (SOCRATES-PRESERVED) study. Eur Heart J. 2017;38(15):1119–1127. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McMurray JJ, Packer M, Desai AS, Gong J, Lefkowitz MP, Rizkala AR, et al. Angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition versus enalapril in heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(11):993–1004. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1409077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Comin-Colet J, Garin O, Lupon J, Manito N, Crespo-Leiro MG, Gomez-Bueno M, et al. Validation of the Spanish version of the Kansas city cardiomyopathy questionnaire. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2011;64(1):51–8. doi: 10.1016/j.recesp.2010.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shih ML, Chen HM, Chou FH, Huang YF, Lu CH, Chien HC. Quality of life and associated factors in patients with heart failure. Hu Li Za Zhi. 2010;57(6):61–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patidar AB, Andrews GR, Seth S. Prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea, associated risk factors, and quality of life among Indian congestive heart failure patients: a cross-sectional survey. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2011;26(6):452–9. doi: 10.1097/JCN.0b013e31820a048e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen HM, Clark AP, Tsai LM, Lin CC. Self-reported health-related quality of life and sleep disturbances in Taiwanese people with heart failure. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2010;25(6):503–13. doi: 10.1097/JCN.0b013e3181e15c37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen HM, Clark AP, Tsai LM, Chao YC, Spertus J. Validation of the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire in Taiwan. Circulation. 2007;115(21):e567. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Callender T, Woodward M, Roth G, Farzadfar F, Lemarie JC, Gicquel S, et al. Heart failure care in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2014;11(8):e1001699. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mentz RJ, Roessig L, Greenberg BH, Sato N, Shinagawa K, Yeo D, et al. Heart Failure Clinical Trials in East and Southeast Asia: Understanding the Importance and Defining the Next Steps. JACC Heart Fail. 2016;4(6):419–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2016.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Qian F, Parzynski CS, Chaudhry SI, Hannan EL, Shaw BA, Spertus JA, et al. Racial Differences in Heart Failure Outcomes: Evidence From the Tele-HF Trial (Telemonitoring to Improve Heart Failure Outcomes) JACC Heart Fail. 2015;3(7):531–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2015.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abraham WT, Adamson PB, Bourge RC, Aaron MF, Costanzo MR, Stevenson LW, et al. Wireless pulmonary artery haemodynamic monitoring in chronic heart failure: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2011;377(9766):658–66. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60101-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Young JB, Abraham WT, Smith AL, Leon AR, Lieberman R, Wilkoff B, et al. Combined cardiac resynchronization and implantable cardioversion defibrillation in advanced chronic heart failure: the MIRACLE ICD Trial. JAMA. 2003;289(20):2685–94. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.20.2685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Committee P-CORIM. PCORI Methodology Standards. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jaarsma T, Halfens R, Tan F, Abu-Saad HH, Dracup K, Diederiks J. Self-care and quality of life in patients with advanced heart failure: the effect of a supportive educational intervention. Heart Lung. 2000;29(5):319–30. doi: 10.1067/mhl.2000.108323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martensson J, Stromberg A, Dahlstrom U, Karlsson JE, Fridlund B. Patients with heart failure in primary health care: effects of a nurse-led intervention on health-related quality of life and depression. Eur J Heart Fail. 2005;7(3):393–403. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2004.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Crespo-Leiro MG, Anker SD, Maggioni AP, Coats AJ, Filippatos G, Ruschitzka F, et al. European Society of Cardiology Heart Failure Long-Term Registry (ESC-HF-LT): 1-year follow-up outcomes and differences across regions. Eur J Heart Fail. 2016;18(6):613–25. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spertus J, Peterson E, Conard MW, Heidenreich PA, Krumholz HM, Jones P, et al. Monitoring clinical changes in patients with heart failure: a comparison of methods. Am Heart J. 2005;150(4):707–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peppercorn JM, Weeks JC, Cook EF, Joffe S. Comparison of outcomes in cancer patients treated within and outside clinical trials: conceptual framework and structured review. Lancet. 2004;363(9405):263–70. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15383-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.