Abstract

The extent of heterogeneity of driver gene mutations present in naturally occurring metastases is largely unknown, i.e. treatment-naïve metastatic disease. To address this issue, 60× whole genome sequencing of 26 metastases from 4 patients was carried out. We found that the identical driver gene mutations were present in every metastatic lesion of each patient studied. Passenger gene mutations not known or predicted to have functional consequences accounted for all intratumoral heterogeneity. Even with respect to these passenger gene mutations, the genetic similarity among the founding cells of metastases was markedly higher than that expected for any two cells randomly taken from a normal tissue. The uniformity of driver gene mutations among metastases in the same patient has critical, encouraging implications for the success of future targeted therapies in advanced stage disease.

The advent of next generation sequencing coupled with multi-region sampling has brought heterogeneity to the forefront of cancer genetics1,2. Remarkable examples of this phenomenon have been shown in carcinomas of the breast3, kidney4, lung5,6, prostate7–9, colon10, pancreas11,12, and melanoma13. Subclonal populations within a neoplasm are phylogenetically related and can be traced back to a single ancestral population based on their complement of somatic mutations14. Such heterogeneity has been extensively documented for more than 50 years, and is expected based on the imperfection of DNA replication: every time a normal cell or a cancer cell divides, ~3 new mutations appear15.

There are at least three types of intratumoral genetic heterogeneity: Type 1 – those mutations that distinguish one cell in a primary tumor from another cell of that same primary tumor; Type 2 - those that distinguish one cell in a metastatic lesion from another cell in that same metastatic lesion; and Type 3 - those within the same primary tumor that distinguish the cell that initiates one metastasis from the cell that initiates another distinct metastasis16,17. Each of these types of heterogeneity has distinct and important clinical implications. For example, Type 1 and 2 heterogeneities explain in part how primary tumors and metastatic lesions, respectively, develop resistance to therapies that are initially effective18–20. Type 3 heterogeneity determines whether metastases within the same patient with advanced disease will respond to initial interventions. In the current age of targeted therapeutics, this type of heterogeneity has become of paramount importance: unless nearly every metastatic lesion has the same driver gene mutation that the therapy targets, the therapy will fail. Finally, there also exists interpatient heterogeneity that helps explain why patients with the same histopathologic type of tumor respond so differently to the same drug regimen21.

Despite its importance, there have been few studies that have evaluated Type 3 heterogeneity through genome-wide sequencing. For example, we could find only four recent publications that have evaluated more than two metastases from any explicitly untreated patient11–13,22. Although several other studies have evaluated metastatic lesions after therapy, the genetic alterations in such lesions often reflect the mutagenic influences and strong selective pressures and bottlenecks associated with therapy rather than the natural course of disease. Other studies that evaluated somatic copy number alterations (SCNAs), either through karyotypes or other technologies, have been published but the changes evaluated can generally not be interpreted with respect to driver genes23,24.

In the current study, we evaluated Type 3 heterogeneity in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinomas (PDACs). PDAC is notorious for presenting as metastatic disease at diagnosis and has a dismal five year survival rate (7%); it is projected to become the third most common cause of cancer death by the end of next year25.

RESULTS

Patient and sample cohort

We implemented strict clinical and technical criteria to identify the optimal patients for study from more than 150 autopsied patients for which tissues were available from a Rapid Medical Donation Program (Supplemental Table 1)26. First, we exclusively used samples from untreated patients for the reasons described above. Second, patients with unusual biological variants of PDAC were also excluded because they differ from the more common ductal adenocarcinomas in their pathogenesis, driver gene alterations27–29, and clinical outcomes30,31. Third, we required that all patients have Stage IV disease, that at least two metastases were available for study, and that the metastases available from each patient accurately represented their disease burden at autopsy (Supplemental Table 1).

Based on these criteria, we identified four patients for detailed evaluation. Histologic sections were prepared from snap frozen samples of the primary tumors and metastases from these four patients to estimate tumor cellularity and tissue quality. Samples with low neoplastic cellularity were excluded, as were any tissue samples with confluent necrosis that would yield low quality genomic DNA (gDNA) (Methods). The remaining samples were macrodissected to remove as much normal tissue as possible before purifying gDNA. A similar approach was previously described11, but in that study only a single metastasis from each patient was evaluated by genome-wide Sanger sequencing, precluding quantification of heterogeneity and limiting the ability to discern evolutionary relationships among metastatic lesions. In all, we identified 26 metastatic lesions suitable for study, as well as samples of the primary tumor and normal tissues, from these four patients (Supplemental Tables 2 and 3).

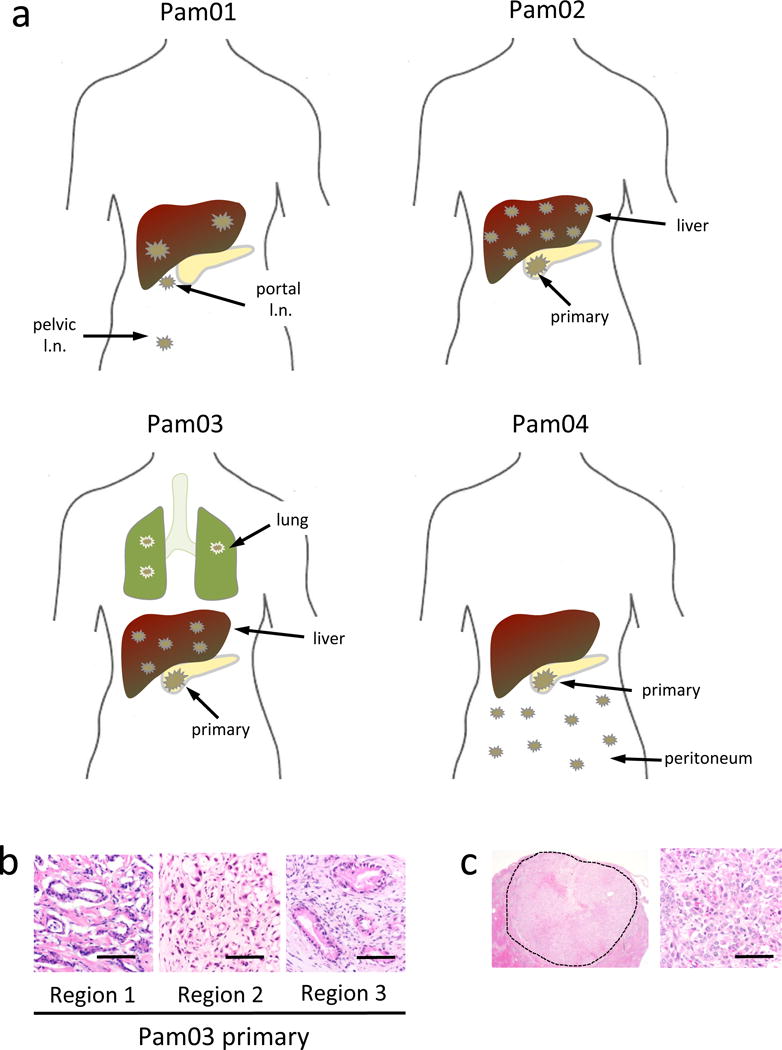

Genomic DNA from 39 samples (26 metastatic lesions, up to three distinct regions of each primary tumor, and normal tissues) were evaluated by 60× whole genome sequencing (WGS) using an Illumina Hi-Seq 2000 platform32 (Figure 1a, 1b). Importantly, all metastases were discrete tumors by both gross examination at autopsy and histologic review, ensuring that each metastasis represented an independent neoplasm at that location (Figure 1c). The metastases were derived from diverse organs including the liver, lung, peritoneum and lymph nodes, all typical secondary sites of pancreatic cancer33. DNA from the normal tissues of each patient was used to facilitate identification of somatic variants.

Figure 1. Distributions of metastatic disease of four pancreatic cancer patients.

a. Anatomic locations of the primary carcinomas (Pam02–Pam04) and discrete metastases (all cases) used for whole genome sequencing. b. Histology of three geographically-independent primary tumor samples from patient Pam03 used for sequencing. c. Low and high power view of a discrete liver metastasis from patient Pam03. The dashed line in the low power view outlines the borders of the metastasis that measured 1.5 cm in diameter. scale bars, 100 μm.

Somatic and driver gene mutations identified

The raw data were filtered for mapping quality and aligned to the hg19 human reference genome, revealing an average coverage of 68× with 97.6% of bases covered at >10×. (Supplemental Table 4). As KRAS is mutated in PDACs at a high frequency, we used the mutant allele fraction (MAF) of KRAS as an independent metric of neoplastic cellularity of our samples. This is particularly important given the high non-neoplastic stromal content of many PDACs34.

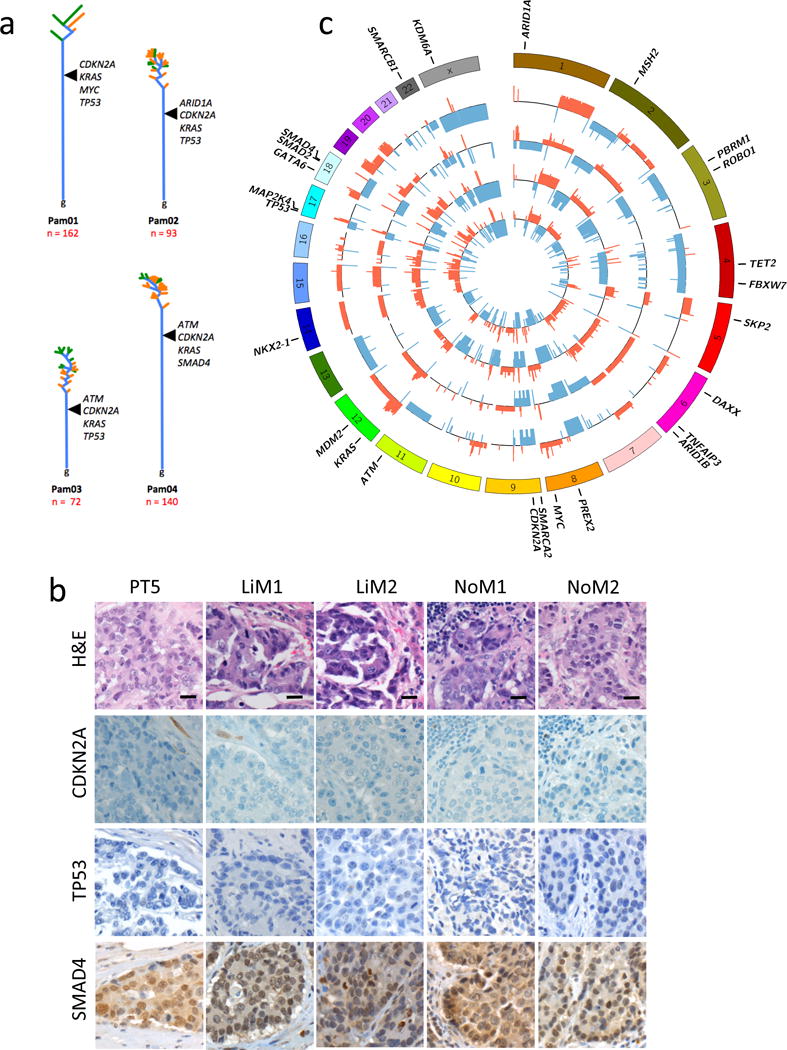

It is well known that massively parallel sequencing yields many artifacts32,35. Moreover, varying estimates of tumor content across samples within an individual complicated identification of parsimony-informative mutations for inferring the genetic relationships among different lesions. We therefore employed filtering criteria to limit potential sequencing artifacts and enrich for true somatic mutations within this sequencing dataset (Methods), resulting in a list of 3811 unique variants among the samples. The vast majority of these mutations were shared among all samples from the same patient (Figure 2a and Supplementary Figure 1). Private (unique) somatic mutations within each primary tumor sample and different metastases were nonetheless identified as expected. KRAS mutations were identified in every sample of all four patients. Mutations in other driver genes, e.g., TP53, SMAD4, ARID1A, and ATM36,37, were also identified in all samples of each patient in which any lesion from that patient contained a mutation (Supplemental Table 5).

Figure 2. Features of Phylogenies and Driver Genes in Pam01, Pam02, Pam03, and Pam04.

a. Time is represented on the vertical axis, divergence is represented on the horizontal axis. Trunks are colored blue, while branches leading to primary tumors are orange and metastases are green. Each tree is rooted at the germline (“g”). Branch and trunk lengths are relative to the number of underlying variants. Driver alterations are labeled where each is inferred to occur during tumor evolution. b. Representative immunolabeling for CDKN2A, TP53, and SMAD4 illustrating the concordance of labeling for each sample analyzed by WGS for Pam01 in the matched available formalin-fixed paraffin embedded tumor tissues for the primary tumor (PT5) and metastases LiM1, LiM2, NoM1 and NoM2. scale bars, 10 μm. c. CIRCOS plots showing statistically significant copy number variants among Pam01 whole genome samples. For each sample ring, the y-axis spans −2 to 2, with 0 representing a normal diploid copy number in unaffected regions, deletions as a −1 or −2, and amplifications as 1 or 2. Copy number variants > 2 are scored as 2. All values were log 2 transformed for visualization. The outermost ring shows the chromosomes in a clock-wise order. Deletions are shown in blue while amplifications are red. Gene names are those described in Supplemental Table 7. From innermost to outermost the samples are PT5, LiM1, LiM2, NoM1 and NoM2.

Homozygous deletions or amplifications that target critical driver genes are not detectable by sequencing of tumor samples that contain contaminating non-neoplastic cells. This is of particular importance for those tumor suppressor gene deletions in PDAC, in which homozygous deletion is a common mechanism of inactivation21. To address this issue, we first immunolabeled each sequenced tissue sample for the proteins encoded by CDKN2A, TP53 and SMAD4, all of which are frequently inactivated in PDACs. Loss of expression for CDKN2A was noted in the primary tumors of all four patients, suggesting that a homozygous deletion or epigenetic silencing was responsible for the inactivation of these tumor suppressor genes38. Importantly, every metastatic lesion of each of these four patients exhibited loss of expression of CDKN2A (Figure 2b). Similarly, loss of expression of TP53 in Pam01 and Pam03 was identified in all samples from these two patients, which were the two not found to exhibit mutations detectable by WGS. Of interest, known homozygous deletions of CDKN2A and TP53 have previously been reported in a cell line derived from Pam01 (PA03C in36). Missense mutations identified in TP53 for Pam02 (p.L344P), in ARID1A for Pam02 (p.Y579X) and in SMAD4 for Pam04 (p.D351G) showed immune-labeling patterns concordant with the predicted effects of these mutations (Supplementary Figure 2), and these labeling patterns were also uniformly present in all samples of each studied patient.

In conjunction with the sequencing and immunohistochemistry results, we reviewed the predicted SCNAs in each sample to further assess genetic amplifications or deletions. We observed many common, partially shared or private copy number variants among the samples within each case, most of which encompassed large numbers (tens to thousands) of genes (Figure 2c, Supplementary Figures 3–7, Supplemental Table 6). In these regions, distinction between a evolutionarily selected low level copy number event versus stochastic aneuploidy is challenging23,24,39. However, some patterns emerged. We noted that the higher the fold of amplification, the fewer genes that were included in that amplicon. This led to identification of candidate somatic target genes with a reasonable level of certainty. Examples of such focal gains were GATA6 and MYC in Pam01 and KRAS in Pam02. These gains were present in every sample in each patient (Supplemental Table 7). Copy number losses of tumor suppressor genes such as ARID1A, CDKN2A, ROBO1, SMAD4, SMARCA2, or TP53 were also identified. Losses followed a similar trend, in that the fewer genes involved in the region of loss, the more likely it involved an undisputed PDAC driver gene, e.g., CDKN2A in Pam04 (Supplemental Table 7)21. In some instances, losses appeared to be heterogeneous across different samples from the same patient, for example SMAD4 in Pam01 and CDKN2A in Pam02. However, as discussed above, immunohistologic evaluation of these two genes showed complete concordance in all sequenced samples for each patient. In samples with relatively low levels of neoplastic cells, these data suggest that immunohistological analysis can add clarity to the interpretation of “negative” sequencing data, i.e., when homozygous losses are not easily identified.

We also identified putative structural variants for each case (Supplemental Tables 8–11, Supplementary Figure 8). These included 3516 break-ends (average 101 per sample), 2763 inversions (average 79 per sample), 1291 tandem duplications (average 37 per sample), and 48 insertions (average 2 per sample). Of these, a minor fraction involved known or candidate genes in PDAC, most of which were already identified by immunolabeling or copy number analysis. However, one liver metastasis from each of patients Pam02 and Pam03 exhibited several unique inversions, the significance of which is not clear (Supplementary Figure 8). Similarly, it is at present difficult to determine the importance, if any, of structural variations not adjacent to driver genes12,21,27.

Quantifying Type 3 heterogeneity

To address the extent of Type 3 heterogeneity in a quantitative fashion, we assessed the differences in single base substitutions among the founding cells of metastases with respect to a null model of genetic heterogeneity. The classical null model, genetic identity, assumes that all tumor cells exhibit exactly the same genetic mutations. However, as the tumors we evaluated are composed of exponentially growing populations of billions of cells, a null model of genetic identity seems unsuitable given the known imperfection of DNA replication. We therefore employed the expected genetic differences in normal tissues as an appropriate null model to assess genetic heterogeneity.

To ensure that only the highest quality data were used for these analyses, we used a targeted sequencing approach based on custom-designed capture probes containing ~100 nt surrounding the 3811 variants of interest. Targeted sequencing was performed on the original 39 samples used for WGS plus four additional metastatic lesions from the same four patients. In total, we identified 614 bona fide mutations in the metastases through this targeted approach (Methods, Supplemental Tables 2, 3, and 12). This highly curated list of 614 mutations included those in passenger genes as well as in the drivers of pancreatic cancer described above, with a median distinct depth of sequencing of 255× (Supplemental Table 4).

We investigated two measures of genetic heterogeneity: genetic distances (“divergence”)40 and Jaccard similarity coefficients. Genetic distance is defined by the total number of non-shared genetic variants present between two samples. The Jaccard similarity coefficient is defined as the ratio of shared variants over all variants (shared plus discordant) between two samples (Table 1 and Supplemental Table 13). For example, two metastatic lesions from the same patient sharing zero mutations would result in a Jaccard similarity coefficient of zero while two lesions with completely identical mutations would result in a coefficient of 1. The similarity coefficient is indifferent to the number of base pairs sequenced in the various samples, some of which differed considerably (Supplemental Table 4).

Table 1.

Jaccard similarity coefficients of metastases based on targeted sequencing (including founder mutations)

| Case | Median | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LiM1 | LiM2 | NoM1 | NoM2 | |||||||||||

| Pam 01 | LiM1 | 1 | 0.75 | |||||||||||

| LiM2 | 0.78 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| NoM1 | 0.75 | 0.67 | 1 | |||||||||||

| NoM2 | 0.79 | 0.75 | 0.68 | 1 | ||||||||||

| LiM1 | LiM2 | LiM3 | LiM4 | LiM5 | LiM6 | LiM7 | LiM8 | |||||||

| Pam 02 | LiM1 | 1 | 0.97 | |||||||||||

| LiM2 | 0.99 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| LiM3 | 0.99 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||

| LiM4 | 0.92 | 0.93 | 0.98 | 1 | ||||||||||

| LiM5 | 0.96 | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.91 | 1 | |||||||||

| LiM6 | 0.97 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.92 | 0.98 | 1 | ||||||||

| LiM7 | 0.96 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.94 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 1 | |||||||

| LiM8 | 0.96 | 0.93 | 0.97 | 0.92 | 0.94 | 0.95 | 0.97 | 1 | ||||||

| LiM1 | LiM2 | LiM3 | LiM4 | LiM5 | LiM6 | LiM7 | LiM8 | LiM9 | LuM1 | LuM2 | LuM3 | |||

| Pam 03 | LiM1 | 1 | 0.89 | |||||||||||

| LiM2 | 0.88 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| LiM3 | 0.89 | 0.96 | 1 | |||||||||||

| LiM4 | 0.84 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 1 | ||||||||||

| LiM5 | 0.9 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 1 | |||||||||

| LiM6 | 0.97 | 0.85 | 0.86 | 0.84 | 0.87 | 1 | ||||||||

| LiM7 | 0.88 | 0.91 | 0.93 | 0.85 | 0.94 | 0.9 | 1 | |||||||

| LiM8 | 0.86 | 0.94 | 0.96 | 0.89 | 0.97 | 0.87 | 0.91 | 1 | ||||||

| LiM9 | 0.86 | 0.94 | 0.97 | 0.88 | 0.97 | 0.87 | 0.93 | 0.99 | 1 | |||||

| LuM1 | 0.98 | 0.87 | 0.88 | 0.81 | 0.88 | 0.96 | 0.89 | 0.85 | 0.86 | 1 | ||||

| LuM2 | 0.94 | 0.88 | 0.86 | 0.88 | 0.89 | 0.91 | 0.86 | 0.85 | 0.85 | 0.95 | 1 | |||

| LuM3 | 0.93 | 0.83 | 0.86 | 0.85 | 0.89 | 0.91 | 0.86 | 0.87 | 0.87 | 0.94 | 0.95 | 1 | ||

| PeM1 | PeM2 | PeM3 | PeM4 | PeM5 | PeM6 | |||||||||

| Pam 04 | PeM1 | 1 | 0.86 | |||||||||||

| PeM2 | 0.8 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| PeM3 | 0.85 | 0.89 | 1 | |||||||||||

| PeM4 | 0.82 | 0.88 | 0.89 | 1 | ||||||||||

| PeM5 | 0.87 | 0.84 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 1 | |||||||||

| PeM6 | 0.84 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.87 | 0.87 | 1 |

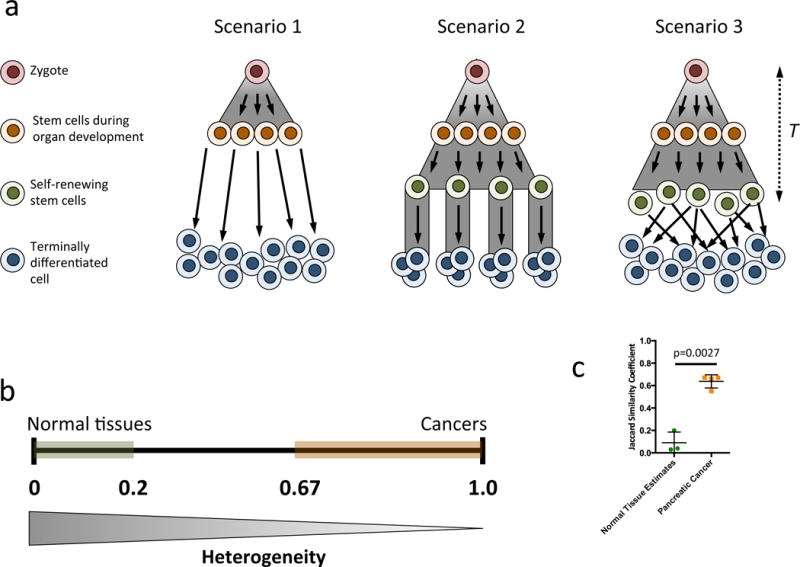

Because mutations present in founder cells of each metastasis are by definition present in all cells of the metastasis once the founder cells clonally expand, all mutations present in the founder cells can be detected by bulk sequencing. The total, measured heterogeneity among metastases thus reflects those of the individual founder cells (Type 3 heterogeneity) plus additional heterogeneity resulting from high frequency mutations subsequently acquired during the growth of the metastasis (Type 2 heterogeneity). The measured Jaccard similarity indices therefore represent an upper bound on Type 3 heterogeneity. In contrast, standard bulk sequencing of DNA from normal tissues is not appropriate for comparison, as this sequencing would not identify differences among individual cells41,42. Likewise, single cell sequencing is currently too error-prone to rely on the data from a single cell, and generally requires identification of the same mutation in more than one cell for accuracy14. Given these challenges, we employed an alternative approach in which the somatic evolution of most types of normal tissues was modeled. The models incorporated stochastic evolutionary processes with differing renewal patterns (Figure 3a; Supplementary Note). In the simplest case (Scenario 1), we modeled an organ that grows via a pure birth branching process to Ncell cells with no further cell divisions (mimicking neuronal cells, for example). For Ncell = 1010, the expected Jaccard similarity coefficient was ~0.03 for two randomly chosen cells from the tissue. For a more complex case (Scenario 2), we derived the similarity coefficient for an organ with Ncrypt cells, where each cell founded a single geographically isolated compartment (such as an intestinal crypt) that continuously replenishes itself, with no mixing or replacement (mimicking intestinal epithelial cells). In this case, the coefficient was less than 0.04 in two randomly chosen cells from the tissue (assuming Ncrypt = 107 cells). Finally, we considered a tissue with Nstem stem cells that not only continuously divides but also exhibits high replacement and mixing (mimicking hematopoietic cells; Scenario 3). For this final scenario, the Jaccard similarity coefficient was <0.2 for relevant time scales and cell population sizes (N >104 cells) and further diminished with the population size of an organ. Thus, for two randomly chosen cells from healthy tissues of various renewal types, the expected similarity coefficients ranged from near zero to no greater than ~0.2 (Figure 3b; Supplementary Note). These theoretical predictions were recently experimentally confirmed by Blokzijl et al. who measured the genetic heterogeneity in organs of 13 healthy individuals by sequencing organoid cultures derived from 38 individual cells42. Using their published mutation data, we found that the mean Jaccard similarity coefficient in two cells from the same colon was 0.075, from the same liver was 0.033 and from the same small intestine was 0.011 (Figure 3b; Supplemental Table 14).

Figure 3. Somatic evolution of normal tissues.

a. Three hypothetical scenarios for normal tissue somatic evolution are considered, T (far right) indicates time. In (1) the organ follows a pure birth process for development with no further cell division. In (2), the organ follows a pure birth process for development of stem cells, each founding a single crypt and dividing over time. The organ in (3) follows the same development as (2) but with substantial mixing and replacement of stem cells. b. The expected Jaccard similarity coefficient, with 0 for no identical mutations and 1 for complete genetic identity among any two cell lineages. The coefficient ranges for normal tissues and metastases are shown in green and red, respectively. The similarity coefficient among the stem-cell-like cells (orange cells in (1); green cells in (2) and (3)) was always below 0.2 in all three scenarios for relevant parameter values. Accounting for possibly additional mutations in short-lived terminally differentiated cells would further increase the heterogeneity within an organ. c. Scatterplot demonstrating that the three types of normal tissue estimates have significantly lower Jaccard similarity coefficients (p=0.0027).

Next, we calculated the Jaccard similarity coefficients of the various pairs of metastases on the basis of their validated mutations. The coefficients averaged 0.89 (Figure 3b and Table 1). The Jaccard similarity coefficients of any metastatic lesion relative to any other metastatic lesion from the same patient was far higher (minimum of 0.67) than that of any modeled normal tissue. Thus, these data demonstrate that the founder cells that seeded these metastatic lesions are more highly related than expected from any two randomly chosen cells from a single normal tissue (p<0.0003, Welch’s t-test). This finding remained valid when using the stringently filtered whole genome data set or when excluding Founder mutations (p<0.0027, Welch’s t-test; Figure 3c, Supplemental Tables 13 and 16).

Pairwise genetic distances40 – defined as the total number of non-shared genetic mutations within the entire exome among two cells - was also calculated in the metatsases based on their validated mutations. We found a maximum of 44, 10, 13, and 36 mutations in Pam01, Pam02, Pam03, and Pam04, respectively (Supplemental Tables 15 and 17, Methods). All measured distances were significantly lower than expected for two randomly chosen cells from a dividing normal tissue (Scenario 2).

Finally, to determine if our findings could be generalized to other patients, we performed 150× whole exome sequencing of 10 primary and metastatic samples from two additional untreated patients that were accrued during the course of this work (Supplementary Figure 9, Supplemental Table 18). We again found that the vast majority of variants were shared among all samples. Critically, there was complete uniformity of driver gene alterations at the single nucleotide in all spatially distinct primary tumor samples and metastases of each patient. The average of the Jaccard similarity coefficients was 0.73, again indicating a high level of genetic similarity of both driver and passenger genes among the founder cells of the metastases.

Phylogenetic analyses of metastases and primary tumor sections

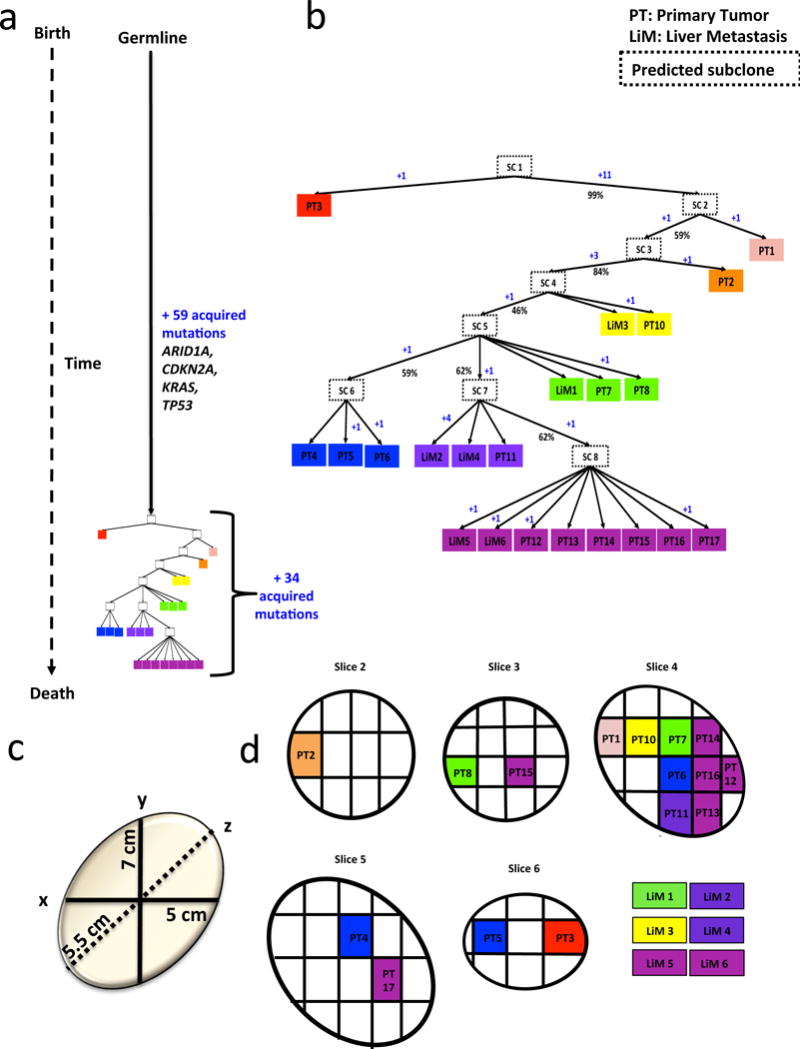

To determine whether the high similarity among metastasis founder cells was consistent with the evolution of these tumors, we first performed targeted sequencing on a total of 59 spatially distinct regions of the four primary tumors from which the metastases emerged (Supplemental Table 2). Because the high similarity coefficients of metastases complicated evolutionary reconstructions, we used Treeomics43 to derive phylogenetic trees (Figure 4a, 4b, Supplementary Figures 10–14). Details of this approach are provided in the Methods. In general, the trees were consistent with the expected generation of metastases from primary tumors. In patients Pam02 and Pam03, we found that metastases within the liver were more likely to be derived from different subclones in the primary tumor than from each other (Figure 4a, 4b and Supplementary Figure 10). This suggested that there were a variety of subclones in the primary tumor that independently gave rise to highly related, but independent metastatic lesions; no single subclone within the primary tumors gave rise to all, or even most of, the metastases (Figure 4a, 4b and Supplementary Figures 10a, 10b, 11a, and 11b). Notably, all of the driver genes identified in the metastases were also identified in all regions of the primary tumors. Phylogenetic analysis also showed that there were no definable geographic regions, based on multiregion sampling and mapping prior to sequencing, among the subclones in the primary tumor nor could their geographic locations be predicted based on their relatedness44 (Figure 4c, 4d, Supplementary Figures 10c, 10d, 11c, and 11d). For example, in the tumors in which the entire phylogeography could be mapped, sections geographically adjacent to each other were observed to be genetically distant (e.g. PT7 and PT14 in Figure 4d). Conversely, tumor sections that were geographically separated by several centimeters were often more genetically similar (e.g. PT2 and PT3 in Figure 4d). These observations can be explained by differential rates of clonal expansion or clonal migration, among other possibilities44,45. We note that the high genetic similarity with no or only a few detected differences between some samples prevented conclusive statements about their evolutionary relationship (indicated by low bootstrapping values in Supplementary Figure 11). We found no evidence to support cross-seeding of metastatic lesions by one another, as expected from a recent study of murine pancreatic cancers46.

Figure 4. Inferred phylogeny and three dimensional geography of primary tumor sections and metastases for patient Pam02.

Phylogeny was inferred by Treeomics43. See Supplemental Table 3 for sample identity. a. Time is represented on the left axis, divergence is represented on the horizontal axis. Colors indicate discrete tumor samples and follow the rainbow spectrum, scaling from ancestral to descendant as indicated by the evolutionary relationships. b. Phylogenetic tree relative to time and number of acquired mutations. Primary tumors are labeled at “PT” followed by sequential numbers, the remaining samples are liver mets labeled as LiM and also followed by a sequential number. Hypothetical subclones are indicated by “SC” followed by the subclone number and enclosed by a dashed outline. The numbers of acquired mutations are in blue font with a “+” sign. Percentages denote bootstrapping values. c. The three dimensional size of the original primary tumor in centimeters. d. Primary tumor slices are numbered according to the original sectioning and plane order.

DISCUSSION

In sum, our data show that the driver gene mutations in the metastases of individual PDAC patients are remarkably uniform. This observation is encouraging with respect to the potential to treat advanced cancer patients with therapeutic agents targeted to these mutations. Whether such uniformity among driver gene mutations in different lesions is found in other tumor types in general is not yet known because, as noted in the Introduction, so few metastases from untreated patients with other cancer types have been analyzed at a genome-wide level. However, available evidence indicates that this uniformity is observed in endometrial47, prostate9 and lung cancers6, but perhaps not in kidney cancers.4,48

One caveat of our study is that we did not assess potential Type 3 heterogeneity of epigenetic changes among metastases49. Another potential limitation is that the effects of copy number variations (CNVs) on genetic drivers in PDAC is difficult to determine, even following careful dissection, because of the substantial amounts of non-neoplastic cells that remain in the purified DNA. To partially circumvent this challenge, we used immunohistochemical methods to evaluate metastatic lesions for inactivation of the most commonly altered tumor suppressor genes (Supplementary Figure 2). We were thus able to evaluate the effects of epigenetic silencing and certain types of CNV in these genes. We indeed identified alterations of these genes, and as with the sequencing data, there was complete uniformity among the patterns observed in the metastatic lesions of any individual patient. A third limitation is that we only could evaluate known driver genes, identified through previous genome-wide studies of more than 500 PDACs. It is possible that additional driver genes, not yet discovered, could exhibit Type 3 heterogeneity in the tumors we examined. Similarly, it is currently not possible to reliably assign responsibility to specific driver genes in regions of copy number or loss that extend over large regions of chromosomes23,24. Heterogeneity of putative, or as yet undiscovered genes or combinations of genes in these regions, would not be evident in our analysis.

The absence of Type 3 heterogeneity among PDAC driver gene mutations contrasts with the extent of Type 3 heterogeneity within passenger genes in the same tumors. Indeed, we observed many genetic differences among the various metastases from the same patient. Such heterogeneity is consistent with a large number of other studies, beginning decades ago, that demonstrate genetic heterogeneity among tumor cells. The older, classic studies focused on karyotypic changes, as no driver gene mutations were known and the technology to detect them had not yet been invented. Two recent papers published during the review of this paper found that the growth dynamics after clonal expansions of some cancers are dominated by neutral evolution, resulting in considerable intratumoral heterogeneity of passenger mutations50,51. Our null model builds on these findings and represents a new way to contextualize intratumoral heterogeneity in a meaningful fashion. Moreover, our mathematical framework can also be used to interpret the genetic heterogeneity in other tissues sequenced in the future and thereby help to understand their clonal architecture.

The comparisons between the Jaccard similarity coefficients among metastases and those expected and measured in normal tissues, and the phylogenetic evaluations of a large number of spatially distinct lesions within the primary tumors, lead to additional insights into PDAC tumor evolution. Collectively, they suggest that metastasis is the direct result of at least one major selective sweep that affects the majority of cells within the primary tumor and includes the final genetic event(s) required for these cells to establish distant, lethal lesions.

Materials and Methods

Selection of patient autopsies

The four patients and their respective tissues originated from the Gastrointestinal Cancer Rapid Medical Donation program, a collection of over 150 autopsy cases. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects. This program has been described previously and was deemed in accordance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act and approved by the Johns Hopkins institutional review board26.

Processing of tissue samples

Once the body cavity was opened using standard autopsy techniques, the entire pancreas and primary tumor were removed along with each grossly identified metastasis. All tissues were immediately flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. Each primary tumor was serially sliced into 0.5 cm thick slices followed by sectioning of each slice into 1×1 cm tissue samples as described previously. One half of each tissue sample was fixed in 10% buffered-formalin while the remaining tissue was preserved at −80°C. Each metastasis was macrodissected to remove surrounding non-neoplastic tissue. Each frozen primary tumor sample was embedded and frozen in Tissue-Tek OCT for sectioning using a Leica Cryostat. For each tissue sample, a 5 μm thick section was taken to create a hematoxylin and eosin slide to visualize neoplastic cellularity using a microscope. A different set of lesions from patient Pam01 were evaluated in Ref. 11; the three other patients described in this paper had not been evaluated previously. We estimated that the neoplastic cellularity was >50% for Pam01, Pam02, and Pam03 and >20% for Pam04.

DNA extraction and quantification

Genomic DNA (gDNA) was extracted from each tissue piece using a standard phenol and chloroform extraction followed by precipitation in ethanol. The gDNA was quantified by LINE assay (i.e. counting long interspersed elements (LINE) using real-time PCR), a particularly sensitive method for calculating gDNA concentration for whole genome sequencing. The LINE primers are in Supplemental Table 19. The real-time PCR protocol was 50°C for 2 min, 95°C for 2 min, 40 cycles of 94°C for 10 s, 58°C for 15 s, and 70°C for 30 s, 95°C for 15 s, and 60°C for 30 s. The PCR reactions were carried out using Platinum SYBR Green qPCR mastermix (Invitrogen). Only those tissue samples that were confirmed to be of high quality and suitable concentration (>25 ng/μl of amplifiable gDNA) were used for WGS or WES.

Whole genome sequencing and alignment

For whole genome sequencing (WGS), several metastases were chosen from all four cases along with three geographically distinct sections of the primary tumor from three of the four cases for a total of 35 samples. WGS was performed on an Illumina Hi-Seq 2000 platform for a target coverage of 60×. Following the completion of sequencing, the data were retrieved and analyzed in silico to determine overall coverage and read quality. Reads were aligned to the hg19 human reference genome. All low-quality, poorly aligned, or dbSNP containing reads were removed from further analysis.

To identify potential drivers, we queried the variant lists for mutations through a combination of previously identified oncogenes and tumor suppressors. This included driver genes identified via a ratiometric approach16, documented hotspots28, and significantly mutated genes identified in recent sequencing studies of pancreatic cancer36,52,37,27,28. For a variant to be considered, it had to be non-silent and occur within two or more of the following types of genes: 1) an oncogene or tumor suppressor gene16, 2) a significantly mutated or known driver gene/pathway in PDAC21,27,36,37,52, 3) a key gene or pathway in PDAC21, or 4) a gene known to have bona fide hotspots28 (Supplemental Table 12).

Whole exome sequencing, alignment, and filtering

The data processing pipeline for detecting variants in Illumina HiSeq data was as follows. First the FASTQ files were processed to remove any adapter sequences at the end of the reads using cutadapt (v1.6). The files were then mapped using the BWA mapper (bwa mem v0.7.12). After mapping the SAM files were sorted and read group tags were added using the PICARD tools. After sorting in coordinate order the BAMs were processed with PICARD MarkDuplicates. The marked BAM files were then processed using the GATK toolkit (v 3.2) according the best practices for tumor-normal pairs. They were first realigned using the InDel realigner and then the base quality values were recalibrated with the BaseQRecalibrator. Somatic variants are then called in the processed BAMs using muTect (v1.1.7).

To identify somatic variants for tumor samples from Pam13 and Pam16, the criteria we used were as follows. Each variant must have been observed in ≥ 3 reads; each mutant must have been observed in at least one read in both directions (i.e., 5′ to 3′ and 3′ to 5′ relative to reference genome); each mutant must not have been observed in >2% of the reads of the matched normal sample; the minimum mutant allele frequency of 5%; the matched normal must have had at least 10 reads total. With manual inspection of the raw data, this approach resulted in a total of 330 putative mutations for phylogenetic analysis. Driver gene mutations were analyzed using the same approach from the WGS data (Supplemental Table 18).

Filtering of whole genome sequencing data and visualization

Whole genome sequencing generated a large list of potential mutations, even after conventional filtering based on quality scores. A total of 54,433 discrete coding and noncoding somatic mutations were identified with an average of 4,759 mutations per sample. We assessed these data with the goal of identifying bona fide mutations and eliminating sequence artifacts. The criteria used to achieve this goal were relaxed compared to what we have previously used16,53 given the variation in neoplastic cell content among the samples (Supplemental Table 3) and our desire to identify somatic mutations (i.e., high sensitivity, intermediate specificity). Furthermore, we planned on experimentally validating each mutation and could thereby tolerate a higher fraction of false positives in this analysis. The criteria we used were as follows. Each mutant must have been observed in > 3 reads (read defined as the output from one cluster on the Illumina instrument); each mutant must have been observed in at least one read in both directions (i.e., 5′ to 3′ and 3′ to 5′ relative to reference genome); each mutant must not have been observed in any reads of the matched normal sample; minimum mutant allele frequency of 10% in samples from patients Pam01, Pam02, & Pam03 and 5% in samples from patient Pam04 given the lower neoplastic cell content of the samples from patient Pam04 (Supplemental Table 3). This analysis yielded a total of 3,811 potential mutations for subsequent validation.

Targeted sequencing design and validation

Strict filtering of the WGS data resulted in a highly conservative and confident list of potential mutations that defined the clonal mutation profile for each tumor sample. This list of 3811 variants was used to design a targeted sequencing effort that incorporated the mutation position +/− 50 base pairs in either direction. Additionally, we aimed to increase our sensitivity of mutation detection by increasing our target coverage to >200×. To do this, we implemented an Illumina chip-based targeted sequencing approach. Once sequencing was completed, the raw data were aligned and processed as described for the WGS data. To filter the chip data for high quality mutations, we removed those that had greater than 2% mutant allele fraction, no distinct coverage in the corresponding normal sample, and did not pass manual review in the WGS raw data.

Evolutionary analysis methods

We leveraged the passenger mutations identified in the WGS of each sample to inferred an overall false positive rate for the mutations of 0.23%, given that two independent cancers were extremely unlikely to harbor identical passenger mutations. In detail, we counted the number of reads in the targeted sequencing data reporting a passenger mutation in samples of different patients than where the mutation was originally identified in the WGS data. The counted number of reads divided by the total number of reads at these positions were used to estimate the false-positive rate. We then used a statistical approach, based on mutant read counts and overall coverage of the targeted sequencing data, to determine whether a variant was present, absent, or unknown in each matched sample by calculating a p-value for each variant via a binomial distribution. The null hypothesis was that the mutation was absent. We used the step-up method of Benjamini and Hochberg54 to control for an average false discovery rate (FDR) of 5% in the combined set of p-values from all samples in a patient. Variants with a rejected null hypothesis were labeled as present. The remaining variants (failed to reject the null hypothesis) were labeled as absent if their coverage was ≥100× and otherwise labeled as unknown. Variants determined to be present or absent were then used for phylogenetic analysis. However, we excluded tumor samples with a median coverage <100× or a median all-mutant allele fraction of <5% based on targeted sequencing data.

Based on the validation and filtering of the variants above that underwent targeted re-sequencing, we derived phylogenies for each patient. The evolutionary trees were “rooted” at the matched patient’s normal sample and the leaves were formed by the tumor samples (i.e. distinct parts of primary tumors or distinct metastatic lesions). We applied Treeomics, a new tool to reconstruct the phylogeny of a cancer with commonly available sequencing technologies43. Treeomics employs a uniquely-designed Bayesian inference model to account for error-prone sequencing and varying low neoplastic cell content to calculate the probability that a specific variant is present or absent in each sequenced lesion. Based on Mixed Integer Linear Programming, we obtained phylogenies consistent with the biological processes underlying cancer evolution55–57. In the case of many samples (>12) per patient, we used a heuristic to efficiently explore the solution space and therefore the acquisition of some variants remained ambiguous. For consistency we assumed a sequencing error rate of 0.5% across all subjects in the phylogenetic analysis.

We found that the large majority of mutations was acquired prior to genetic divergence in our samples. The low extent of genetic heterogeneity among the samples resulted in relatively “low” support (indicated by rather low bootstrapping values) for branching events, a difficulty also observed in sequencing studies of incipient or recently diverged species. Across the four patients, the number of acquired mutations ranged from 92–219. Since we obtained ~50 samples per subject, it seems unlikely that biologically relevant tumor subclones would fail to be detected in all samples of a given patient. However, we cannot completely exclude this possibility.

Evolutionary analysis results

The inferred phylogenetic tree of Pam01 indicates that the pelvic lymph node metastasis 1 (NoM1) was apparently seeded significantly earlier than portal lymph node metastasis (NoM2) and the liver metastasis (LiM1) (Supplementary Figure 1a and 12). The portal lymph node metastasis and the liver metastasis originate from a genetically similar subclone (Supplementary Figure 12).

For Pam02, we found that many of the liver metastases were more closely related to one of the primary tumor sections than they were to each other (Supplementary Figure 1b). This provided strong evidence that coexistent metastases within the liver were more likely to be derived from different subclones (or regions) in the primary tumor than from each other (Figure 4). Interestingly, we also noted that these regions were not obviously related to adjacent regions, and were often more related to distant subclones within the primary tumor (Figure 4d).

In Pam03, we evaluated four additional metastases (LiM6–9) to assist our phylogenetic analysis. Our inferred phylogenetic tree showed that the two liver metastases (LiM2 and 4) were closely related (Supplementary Figure 1c, and 10). The analyses also indicate that the lung metastasis diverged earlier in the evolution of this tumor than the liver metastases (Supplementary Figure 10).

For Pam04, the low neoplastic cell content hindered the derivation of robust phylogenies (Supplementary Figure 11). Interestingly, the primary tumor for this case demonstrated a similar mixed pattern without evidence for strictly spatially distinct subclones (Supplementary Figure 11). It was notable that this patient was the only one with a peritoneal pattern of metastasis, a form of metastasis unrelated to hematogenous spread58. Exchange of cells within the peritoneum could in theory explain the difficult tree reconstructions.

We also inferred phylogenies for the two patients for which we had whole exome sequencing. For Pam13 (Supplementary Figure 13), two liver mets (LiM1 and LiM3) evolved from the same subclone. The third liver met (LiM2) was inferred to be more closely related to the primary tumor (PT1) than to the other two liver mets. For Pam16 (Supplementary Figure 14), the lymph node and liver met more closely relate to one primary tumor section (PT2) than the other (PT1).

Immunohistochemistry for driver gene expression

Although we restricted our evolutionary analyses to point mutations, we sought to determine the extent to which alternative genetic events may be affecting common PDAC drivers. Briefly, slides bearing tissue were heated at 60°C for 10 minutes, deparaffinized, and rehydrated using a ethanol gradient to water. Slides were exposed to DAKO Target Retrieval solution for 25 minutes in steam conditions and allowed to cool for 30 minutes. Tissue slides were subsequently washed. Each antibody was diluted as per manufacturer protocol in DAKO antibody diluent. Slides were treated with antibody dilution for one hour at room temperature and subsequently washed. DAKO Labeled Polymer HRP was used as a secondary antibody exposed to slides for 10 minutes followed by slide washing. Each slide was treated with DAB for 2.5 minutes, washed in deionized water, then stained with Hematoxylin and washed. Any other antibody specific procedures were implemented as needed. Tissue slides were subsequently dehydrated through an increasing gradient of ethanol, dried, and visualized. We implemented immunohistochemistry for CDKN2A (Ventana 725-4713), TP53 (Dako M700101-2), SMAD4 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology sc-7966), and ARID1A (Santa Cruz Biotechnology sc-32761) on matched tumor sections from each of the four cases (Supplementary Figure 2). In all examples the expression patterns of each driver (whether abnormal or not) remained unchanged among the primary tumor subclones and metastases within each case and do not change our conclusions or interpretations of the genetic data for each patient (Supplementary Figure 2). We also used this approach to determine the expression patterns in the primary tumor and metastasis samples for Pam01. The presence of nuclear labeling observed for both SMAD4 and ARID1A are consistent across all samples, indicating that these genes were not affected by copy number alterations (i.e. homozygous deletions) that may have been missed by our method (Figure 2b).

The expression patterns among all samples from individual patients were identical, consistent with previous results59. The expression patterns of the driver genes were also concordant with expectations from the sequencing data. For CDKN2A, we observed a loss of expression in all four patients among all tumor cells: this is an example of a driver gene with no point mutations detected by sequencing but with loss of expression, indicating either methylation or a homozygous deletion. For TP53, Pam02 demonstrated p53 at stabilized, high nuclear levels as expected from the p. L344P missense mutation identified by WGS. By contrast Pam01 and Pam03 showed loss of p53 expression in the cancer cells (internal control normal cells were positive) despite not finding a mutation by sequencing, also indicating a homozygous deletion in these two tumors. This is consistent with our prior observation of a homozygous deletion of exons 1–3 in Pam01, (known as Pa04C in that study)36. Pam04 p53 expression patterns showed weak positive labeling of tumor nuclei, and no mutation was identified by sequencing, consistent with the presence of a wild type TP53 gene. Interestingly, SMAD4 expression was retained in Pam01, Pam02, and Pam03, consistent with the fact that SMAD4 loss is not a requirement for metastasis formation in pancreatic cancer. Pam04, the only tumor with a SMAD4 p.D351G missense mutation detected by sequencing, showed scattered positive nuclear labeling. This expression pattern is consistent with prior observations of retention of low levels of mutant nuclear SMAD4 protein expression when the missense mutation is located in the mutation cluster region of the gene (codons 330–370 within the MH2 domain)60. For ARID1A, a p.Y579X nonsense mutation was identified in Pam02 and immunolabeling for the ARID1A gene project indicated loss of protein expression. Arid1A expression was retained in Pam01, Pam02 and Pam03 that were wild type per sequencing.

Analyses of SCNAs and B-allele frequencies

For tumors that underwent whole genome sequencing, we used Control-FREEC package to call CNVs. All read counts in BAM files of tumor samples were first corrected for read counts in the matched normal BAM file and then normalized for GC-content bias given the hg19 reference genome61. Ploidy was assumed 2 for all cases. Contamination ratio by normal cells estimated by targeted resequencing was also provided for each individual tumor sample. Window and step sizes were set 50000 and 10000, respectively. Threshold for segmentation of normalized profiles was set 0.6 that is lower than default in order to get more predicted CNV segments. We finally selected significant CNVs that have passed both Wilcoxon and Kolmogorov-Smirnov test (p-values <0.05)61,62.

Additionally, more than 3000 SNPs were used to estimate B-allele frequencies at the chromosomal level in two cases, Pam01 and Pam02. Major copy number alterations and loss of heterozygosity events were observable in all primary tumor sections and metastases (Supplementary Figures 2–5).

To identify putative driver genes involved in SCNAs (Supplemental Table 7), the SCNA had to be an amplification with a CN = ≥5 or a deletion with a CN = 0 in at least one tumor sample within each case, involving 1) an oncogene or tumor suppressor gene16, or 2) a key gene or pathway in PDAC21. For identifying recurrent chromosomal losses or gains, at least one SCNA had to be an amplification with a CN = ≥5 or a deletion with a CN = 0 in at least one tumor sample within each case while occurring in a recurrently altered chromosome band in PDAC27.

Structural variant analysis

To identify structural variants in the WGS data, the GROUPER module in CASAVA (version 1.1a1) was used with standard settings. Structural variants present in the patient-matched normal were filtered from subsequent analysis. Driver genes were identified using the same references as the SCNAs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center Molecular Cytology core facility for immunohistochemistry staining.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants CA179991 (C.A.I-D., I.B.), F31CA180682 (A.M-M.), CA43460 (B.V.), P50 CA62924, The Monastra Foundation, The Virginia and D.K. Ludwig Fund for Cancer Research, Lustgarten Foundation for Pancreatic Cancer Research, and The Sol Goldman Center for Pancreatic Cancer Research, The Sol Goldman Sequencing Center, ERC Start grant 279307: Graph Games (J.G.R, D.K., C.K.), Austrian Science Fund (FWF) grant no P23499-N23 (J.G.R, D.K., C.K.), FWF NFN grant no S11407-N23 RiSE/SHiNE (J.G.R, D.K., C.K.).

Footnotes

Accession Codes. Sequencing data have been deposited at the European Genome-phenome Archive (EGA) under accession EGAS00001002186. Further information about the EGA can be found at https://ega-archive.org/.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

C.I.D. and A.M.M. performed the autopsies, C.I.D., A.M.M., B.V., K.K., N.P., M.Z., F.W., and Y.J. designed experiments, A.M.M, J.R., I.B., F.W., J.H, and M.A. performed biostatistical analyses, A.M.M., M.Z., B.M., and Z.K. performed the experiments, J.R., I.B., J.H., D.K., and K.C. performed computational analysis, J.R., I.B., B.A., and M.N. performed modeling, all authors interpreted the data, C.I.D. A.M.M. and B.V. wrote the manuscript, J.R., I.B., and M.N. provided input to the manuscript, and all authors read and approved the final manuscript.

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Code availability

The code for Treeomics43 is freely available at https://github.com/johannesreiter/treeomics.

Data availability

Sequencing data files can be found using the above mentioned accession codes. Reprints and permissions information is available.

References

- 1.Greaves M, Maley CC. Clonal evolution in cancer. Nature. 2012;481:306–13. doi: 10.1038/nature10762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alizadeh AA, et al. Toward understanding and exploiting tumor heterogeneity. Nat Med. 2015;21:846–853. doi: 10.1038/nm.3915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yates LR, et al. Subclonal diversification of primary breast cancer revealed by multiregion sequencing. Nat Med. 2015;21:751–9. doi: 10.1038/nm.3886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gerlinger M, et al. Genomic architecture and evolution of clear cell renal cell carcinomas defined by multiregion sequencing. Nat Genet. 2014;46:225–33. doi: 10.1038/ng.2891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Bruin EC, et al. Spatial and temporal diversity in genomic instability processes defines lung cancer evolution. Science (80-) 2014;346:251–256. doi: 10.1126/science.1253462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang J, et al. Intratumor heterogeneity in localized lung adenocarcinomas delineated by multiregion sequencing. Science. 2014;346:256–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1256930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gundem G, et al. The evolutionary history of lethal metastatic prostate cancer. Nature. 2015;520:353–7. doi: 10.1038/nature14347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hong MKH, et al. Tracking the origins and drivers of subclonal metastatic expansion in prostate cancer. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6605. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kumar A, et al. Substantial interindividual and limited intraindividual genomic diversity among tumors from men with metastatic prostate cancer. Nat Med. 2016;22:369–78. doi: 10.1038/nm.4053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jones S, et al. Comparative lesion sequencing provides insights into tumor evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:4283–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712345105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yachida S, et al. Distant metastasis occurs late during the genetic evolution of pancreatic cancer. Nature. 2010;467:1114–7. doi: 10.1038/nature09515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Campbell PJ, et al. The patterns and dynamics of genomic instability in metastatic pancreatic cancer. Nature. 2010;467:1109–13. doi: 10.1038/nature09460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sanborn JZ, et al. Phylogenetic analyses of melanoma reveal complex patterns of metastatic dissemination. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1508074112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Navin N, et al. Tumour evolution inferred by single-cell sequencing. Nature. 2011;472:90–4. doi: 10.1038/nature09807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tomasetti C, Vogelstein B, Parmigiani G. Half or more of the somatic mutations in cancers of self-renewing tissues originate prior to tumor initiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:1999–2004. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1221068110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vogelstein B, et al. Cancer genome landscapes. Science. 2013;339:1546–58. doi: 10.1126/science.1235122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Makohon-Moore A, Iacobuzio-Donahue CA. Pancreatic cancer biology and genetics from an evolutionary perspective. Nat Rev Cancer. 2016;16:553–65. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barber LJ, et al. Secondary mutations in BRCA2 associated with clinical resistance to a PARP inhibitor. J Pathol. 2013;229:422–9. doi: 10.1002/path.4140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Diaz LA, et al. The molecular evolution of acquired resistance to targeted EGFR blockade in colorectal cancers. Nature. 2012;486:537–40. doi: 10.1038/nature11219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Misale S, et al. Emergence of KRAS mutations and acquired resistance to anti-EGFR therapy in colorectal cancer. Nature. 2012;486:532–6. doi: 10.1038/nature11156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Waddell N, et al. Whole genomes redefine the mutational landscape of pancreatic cancer. Nature. 2015;518:495–501. doi: 10.1038/nature14169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoogstraat M, et al. Genomic and transcriptomic plasticity in treatment-naive ovarian cancer. Genome Res. 2014;24:200–11. doi: 10.1101/gr.161026.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krasnitz A, Sun G, Andrews P, Wigler M. Target inference from collections of genomic intervals. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:E2271–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1306909110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davoli T, et al. Cumulative haploinsufficiency and triplosensitivity drive aneuploidy patterns and shape the cancer genome. Cell. 2013;155:948–62. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;66:n/a–n/a. doi: 10.3322/caac.21332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Embuscado E, et al. Immortalizing the Complexity of Cancer Metastasis. Cancer Biol Ther. 2005:548–554. doi: 10.4161/cbt.4.5.1663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bailey P, et al. Genomic analyses identify molecular subtypes of pancreatic cancer. Nature. 2016;531:47–52. doi: 10.1038/nature16965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chang MT, et al. Identifying recurrent mutations in cancer reveals widespread lineage diversity and mutational specificity. Nat Biotechnol. 2016;34:155–63. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Douville C, et al. CRAVAT: cancer-related analysis of variants toolkit. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:647–8. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iacobuzio-Donahue CA, Velculescu VE, Wolfgang CL, Hruban RH. Genetic basis of pancreas cancer development and progression: insights from whole-exome and whole-genome sequencing. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:4257–65. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-0315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Borazanci E, et al. Adenosquamous carcinoma of the pancreas: Molecular characterization of 23 patients along with a literature review. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2015;7:132–40. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v7.i9.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kinde I, Wu J, Papadopoulos N, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Detection and quantification of rare mutations with massively parallel sequencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:9530–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105422108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yachida S, Iacobuzio-Donahue CA. The pathology and genetics of metastatic pancreatic cancer. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:413–22. doi: 10.5858/133.3.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Olive KP, et al. Inhibition of Hedgehog signaling enhances delivery of chemotherapy in a mouse model of pancreatic cancer. Science. 2009;324:1457–61. doi: 10.1126/science.1171362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Campbell PJ, et al. Subclonal phylogenetic structures in cancer revealed by ultra-deep sequencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:13081–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801523105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jones S, et al. Core signaling pathways in human pancreatic cancers revealed by global genomic analyses. Science. 2008;321:1801–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1164368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Biankin AV, et al. Pancreatic cancer genomes reveal aberrations in axon guidance pathway genes. Nature. 2012;491:399–405. doi: 10.1038/nature11547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schutte M, et al. Abrogation of the Rb/p16 tumor-suppressive pathway in virtually all pancreatic carcinomas. Cancer Res. 1997;57:3126–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Santarius T, Shipley J, Brewer D, Stratton MR, Cooper CS. A census of amplified and overexpressed human cancer genes. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:59–64. doi: 10.1038/nrc2771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maley CC, et al. Genetic clonal diversity predicts progression to esophageal adenocarcinoma. Nat Genet. 2006;38:468–73. doi: 10.1038/ng1768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fernández LC, Torres M, Real FX. Somatic mosaicism: on the road to cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2015;16:43–55. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2015.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Blokzijl F, et al. Tissue-specific mutation accumulation in human adult stem cells during life. Nature. 2016;538:260–264. doi: 10.1038/nature19768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reiter JG, et al. Reconstructing the evolutionary history of metastatic cancers (accepted) doi: 10.1101/048157. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sottoriva A, et al. A Big Bang model of human colorectal tumor growth. Nat Genet. 2015;47:209–16. doi: 10.1038/ng.3214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Waclaw B, et al. A spatial model predicts that dispersal and cell turnover limit intratumour heterogeneity. Nature. 2015;525:261–264. doi: 10.1038/nature14971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Maddipati R, Stanger BZ. Pancreatic Cancer Metastases Harbor Evidence of Polyclonality. Cancer Discov. 2015;5:1086–97. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-0120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gibson WJ, et al. The genomic landscape and evolution of endometrial carcinoma progression and abdominopelvic metastasis. Nat Genet. 2016;48:848–55. doi: 10.1038/ng.3602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gerlinger M, et al. Intratumor heterogeneity and branched evolution revealed by multiregion sequencing. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:883–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1113205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jones PA, Baylin SB. The epigenomics of cancer. Cell. 2007;128:683–92. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Williams MJ, Werner B, Barnes CP, Graham TA, Sottoriva A. Identification of neutral tumor evolution across cancer types. Nat Genet. 2016 doi: 10.1038/ng.3489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bozic I, Gerold JM, Nowak MA. Quantifying Clonal and Subclonal Passenger Mutations in Cancer Evolution. PLoS Comput Biol. 2016;12:e1004731. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Witkiewicz AK, et al. Whole-exome sequencing of pancreatic cancer defines genetic diversity and therapeutic targets. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6744. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jiao Y, et al. Exome sequencing identifies frequent inactivating mutations in BAP1, ARID1A and PBRM1 in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas. Nat Genet. 2013;45:1470–3. doi: 10.1038/ng.2813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. J R Stat Soc. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Salari R, et al. Inference of tumor phylogenies with improved somatic mutation discovery. J Comput Biol. 2013;20:933–44. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2013.0106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.El-Kebir M, Oesper L, Acheson-Field H, Raphael BJ. Reconstruction of clonal trees and tumor composition from multi-sample sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:i62–70. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Popic V, et al. Fast and scalable inference of multi-sample cancer lineages. Genome Biol. 2015;16:91. doi: 10.1186/s13059-015-0647-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nguyen DX, Bos PD, Massagué J. Metastasis: from dissemination to organ-specific colonization. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:274–84. doi: 10.1038/nrc2622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yachida S, et al. Clinical significance of the genetic landscape of pancreatic cancer and implications for identification of potential long-term survivors. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:6339–47. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Iacobuzio-Donahue CA, et al. Missense mutations of MADH4: characterization of the mutational hot spot and functional consequences in human tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:1597–604. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-1121-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Boeva V, et al. Control-FREEC: a tool for assessing copy number and allelic content using next-generation sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:423–5. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Krzywinski M, et al. Circos: an information aesthetic for comparative genomics. Genome Res. 2009;19:1639–45. doi: 10.1101/gr.092759.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.