Abstract

The Erwinia genus comprises species that are plant pathogens, non-pathogen, epiphytes, and opportunistic human pathogens. Within the genus, Erwinia amylovora ranks among the top 10 plant pathogenic bacteria. It causes the fire blight disease and is a global threat to commercial apple and pear production. We analyzed the presence/absence of the E. amylovora genes reported to be important for pathogenicity towards Rosaceae within various Erwinia strains genomes. This simple bottom-up approach, allowed us to correlate the analyzed genes to pathogenicity, host specificity, and make useful considerations to drive targeted studies.

Keywords: Fire blight, Comparative genomics, BLAST, Pathogenesis, Virulence factor

Introduction

Erwinia amylovora is a Gram negative bacterium affiliated to the Enterobacteriaceae family and the first phytopathogenic bacterium ever described (Vanneste 2000). E. amylovora is the aetiological agent of the fire blight disease in Rosaceae and represents a major global threat to commercial apple and pear production (Norelli et al. 2003; Van der Zwet et al. 2012; Vanneste 2000). A fire blight outbreak may cause the loss of the entire annual harvest and lead to a dramatic economic damage (e.g., in the year 2000 Michigan economy lost $42 million) (Norelli et al. 2003). Weather condition markedly influence E. amylovora growth. Therefore, disease-forecasting models have been developed to prevent the disease onset by spraying chemicals when the weather conditions are predicted favorable to E. amylovora proliferation (Shtienberg et al. 2003; Van der Zwet et al. 1994). The infection usually occurs in spring when the temperature increases over 18 °C and it spreads by both insects and rain. The disease starts when the bacteria infect the plant through the flower nectarthodes, or through wounds. Within a few days, the infection diffuse rapidly to the whole blossom and young shoots. In a few months, the disease spreads to the whole plant becoming systemic (Smits et al. 2013; Vanneste 2000). Typical symptoms include flower necrosis, blighted shoots and woody tissues cankers. Besides, a common sign of fire blight is the appearance of bacterial ooze. Currently, the main methods to control fire blight are quarantine, pruning and/or eradication of the plants, the use of biological and chemical pesticides, antibiotics and resistant cultivars obtained by classical breeding, or by genetic engineering (Gusberti et al. 2015). However, antibiotics and genetically modified plants are not allowed in most countries where prevention of infections is still the main control method. Several studies upon E. amylovora physiology and genetics have shed light on its pathogenicity at the molecular level, bringing out the major virulence factors (Piqué et al. 2015; Smits et al. 2011). Aiming to a better understanding of the gene-pathogenicity and gene–host relationships, we have selected the DNA sequences encoding proteins that are reported to be important in the pathogenesis of E. amylovora and we investigated their presence/absence within the strains of Erwinia whose genomes are sequenced and assembled (Ancona et al. 2013, 2015, 2016; Bereswill and Geider 1997; Coyne et al. 2013; Du and Geider 2002; Edmunds et al. 2013; Kube et al. 2008, 2010; Mann et al. 2013; Nissinen et al. 2007; Oh and Beer 2005; Pester et al. 2012; Piqué et al. 2015, Smits et al. 2011; Wang et al. 2009, 2011; Zeng et al. 2013; Zhao and Qi 2011).

Material and methods

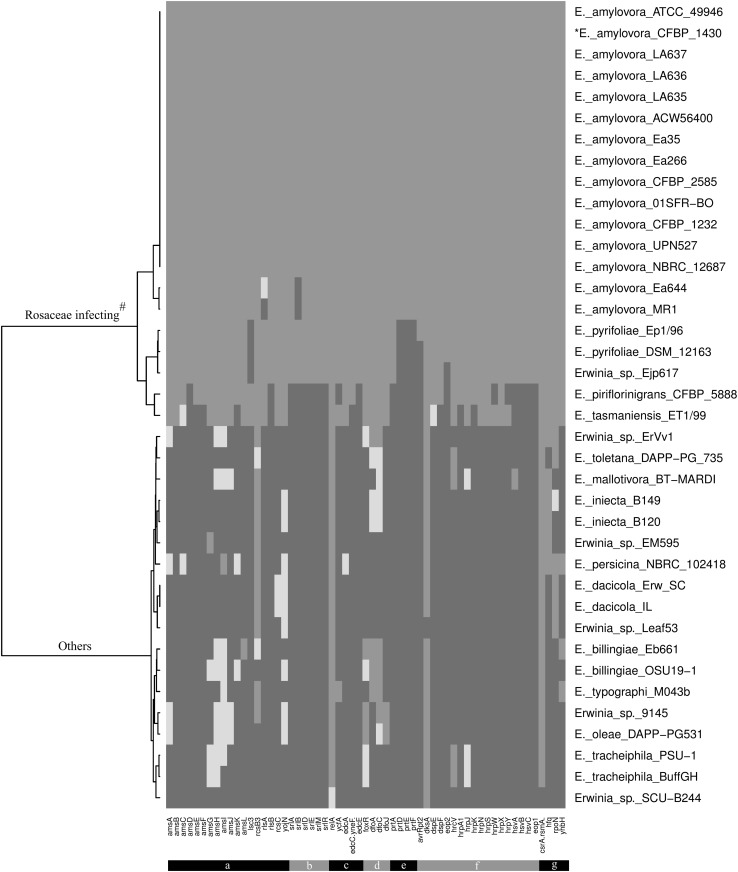

The DNA sequences of 59 genes belonging to Erwinia amylovora CFBP1430 (reference genome) and encoding proteins, reported to be important for pathogenicity in E. amylovora, were extracted from the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA; http://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena). The genomes of the 38 Erwinia strains analyzed in this study derived from the NCBI-Genome database (Table 1). The 59 DNA sequences were BLASTed against the 38 Erwinia genomes DNA via the command-line annotation tool Blast, using default settings. A Heatmap Hierarchical Clustering based on Euclidean Distance method was generated via the R software using the heatmap() function from the R Base Package (Fig. 1) (R Core Team 2012). The identity threshold was set according to the following criteria: (1) DNA sequences with a coverage ≥80% and identity ≥75% were marked in green. (2) Sequences with a coverage ≥80% and identity <75% are marked in yellow. (3) Sequences with a coverage <75% were interpreted as the absence of the paralogue and are marked in red. The sequences were grouped according to the following functional systems: exopolysaccharide metabolism, type 3 secretion system (T3SS), positive regulator of virulence factor, desferrioxamine pathway, guanine derivative regulation, sRNA chaperone, two-component signal transduction system, type 1 secretion system, transcription regulator, sorbitol metabolism.

Table 1.

Characteristic of the Erwinia genome strains analyzed in this study

| Strain | Accession number | Habitat/host | Plant pathogenicity |

|---|---|---|---|

| E. amylovora ATCC 49946# | GCA_000027205.1 | Malus sp. (apple tree) | Pathogen of Spiraeoideaea (Mann et al. 2013) |

| E. amylovora CFBP1430*,# | GCA_000091565.1 | Crataegus (hawthorn) | Pathogen of Spiraeoideae (Mann et al. 2013) |

| E. amylovora LA637# | GCA_000513355.1 | Malus sp. (apple tree) | Pathogen of Malus sp. (Smits et al. 2014) |

| E. amylovora LA636# | GCA_000513395.1 | Malus sp. (apple tree) | Pathogen of Malus sp. (Smits et al. 2014) |

| E. amylovora LA635# | GCF_000513415.1 | Malus sp. (apple tree) | Pathogen of Malus sp. (Smits et al. 2014) |

| E. amylovora ACW56400# | GCF_000240705.2 | Pyrus communis (pear tree) | Pathogen of Spiraeoideae (Mann et al. 2013) |

| E. amylovora Ea356# | GCF_000367545.1 | Cotoneaster sp. (garden shrubs) | Pathogen of Spiraeoideae (Mann et al. 2013) |

| E. amylovora Ea266# | GCA_000367565.2 | Malus sp. (apple tree) | Pathogen of Spiraeoideae (Mann et al. 2013) |

| E. amylovora CFBP 2585# | GCF_000367585.2 | Sorbus sp. (rowan) | Pathogen of Spiraeoideae (Mann et al. 2013) |

| E. amylovora 01SFR BO# | GCA_000367605.2 | Sorbus sp. (rowan) | Pathogen of Spiraeoideae (Mann et al. 2013) |

| E. amylovora CFBP 1232# | GCA_000367625.2 | Pyrus communis (pear tree) | Pathogen of Spiraeoideae (Mann et al. 2013) |

| E. amylovora UPN527# | GCA_000367645.1 | Malus sp. (apple tree) | Pathogen of Spiraeoideae (Mann et al. 2013) |

| E. amylovora NBRC 12687b,# | GCA_000696075.1 | Pyrus communis (pear tree)c | – |

| E. amylovora Ea644# | GCA_000696075.1 | Rubus idaeus (raspberry) | Pathogen of Rubus (Mann et al. 2013) |

| E. amylovora MR1# | GCA_000367685.2 | Rubus idaeus (raspberry) | Pathogen of Rubus (Mann et al. 2013) |

| E. pyrifoliae Ep1/96# | GCA_000027265.1 | Pyrus pyrofolia (asian pear tree/nashi) | Pathogen of Pyrus pyrifolia (Kube et al. 2010) |

| E. pyrifoliae DSM-12163# | GCA_000026985.1 | Pyrus pyrifolia (asian pear tree/nashi) | Pathogen of Pyrus pyrifolia (Geider et al. 2009) |

| Erwinia sp. Ejp617# | GCA_000165815.1 | Pyrus pyrifolia (asian pear tree/nashi) | Pathogen of Pyrus pyrifolia (Park et al. 2011) |

| E. piriflorinigrans CFBP-5888# | GCA_001050515.1 | Pyrus communis (pear tree) | Pathogen of Pyrus communis (López et al. 2011) |

| E. tasmaniensis ET1/99 | GCA_000026185.1 | Malus sp. (apple tree) | Non-pathogen (Kube et al. 2008, 2010) |

| E. typographi M043b | GCA_000773975.1 | Ips typographus (bark beetle) | Non-pathogen (Skrodenyte-Arbaciauskiene et al. 2012) |

| E. billingiae OSU19-1 | GCF_001269445.1 | Pyrus communis (pear tree) | Non-pathogen (Klein et al. 2015) |

| E. billingiae Eb661 | GCA_000196615.1 | Malus sp. (apple tree) | Non-pathogen (Kube et al. 2008) |

| E. toletana DAPP-PG-7351 | GCA_000336255.1 | Olea sp. (olive tree) | Pathogen associatedd of Olea sp. (Passos da Silva et al. 2013) |

| Erwinia teleogrylli SCU-B244 | GCF_001484765.1 | Teleogryllus occipitalis (mole cricket) | Non-pathogen (Liu et al. 2016) |

| Erwinia sp. 9145 | GCA_000745075.1 | Facultative endohyphal bacterium | Non-pathogen (Baltrus et al. 2017) |

| E. oleae DAPP-PG531 | GCA_000770305.1 | Olea europaea (olive tree) | Non-pathogen (Moretti et al. 2011, 2014) |

| E. tracheiphila BuffGH | GCA_000975275.1 | Cucurbita pepo ssp. Texana (squash plant) | Pathogen of Cucurbitaceae (Shapiro et al. 2016) |

| E. tracheiphila PSU-1 | GCA_000404125.1 | Cucurbita pepo ssp. Texana (squash plant) | Pathogen of Cucurbitaceae (Shapiro et al. 2016) |

| E. mallotivora BT-MARDI | GCA_000590885.1 | Carica sp. (papaya tree) | Pathogen of Carica sp. (Redzuan et al. 2014) |

| E. persicina NBRC-102418 | GCA_001571305.1 | Piezodorus guildinii (guts of redbanded stink bug) and Leguminosae (legume plants) | Pathogen of Leguminosae (González et al. 2007; Zhang and Nan 2014) |

| Erwinia sp. ErVv1 | GCA_900068895.1 | Vitis vinifera (grapevine) | Non-pathogen (Lopez-Fernandez et al. 2015) |

| Erwinia sp. EM595 | GCA_001517405.1 | Malus sp. (pome fruit trees) | Non-pathogen (Rezzonico et al. 2016) |

| E. dacicola Erw SC | GCA_001689725.1 | Bactrocera oleae (olive fruit fly) | Non-pathogen (Blow et al. 2016; Estes et al. 2009) |

| E. dacicola IL | GCA_001756855.1 | Bactrocera oleae (olive fruit fly) | Non-pathogene |

| Erwinia sp. Leaf53 | GCA_001422605.1 | Arabidopsis thaliana | Non-pathogen (Bai et al. 2015) |

| E. iniecta B149 | GCA_001267545.1 | Diuraphis noxia (wheat aphid) | Non-pathogen (Campillo et al. 2015) |

| E. iniecta B120 | GCA_001267535.1 | Diuraphis noxia (wheat aphid) | Non-pathogen (Campillo et al. 2015) |

aNomenclature that follows Potter et al., Plant Syst. Evol., 2007 (Potter et al. 2007). However, some authors define the subfamily as Amygdaloideae

bNo reference available

cInformation derived from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/biosample/SAMD00016891/ on February the 15th 2017

dFound on olive knots caused by the plant bacterium Pseudomonas savastanoi pv. savastanoi. The presence of E. toletana is correlated with the virulence of the disease suggesting a possible interactions with P. savastanoi pv. Savastanoi

eHere we assume that this strain is non-pathogenic based on E. dacicola Erw SC

*E. amylovora CFBP1430 is the reference genome where all the DNA gene sequences were extracted

#These strains are Rosaceae-infecting

Fig. 1.

Heatmap hierarchical clustering: on the right, Erwinia strains are listed; on the bottom, genes important for virulence within E. amylovora are reported. Color code: green indicates a coverage ≥80% with an identity between 100% and 80%, yellow indicates a coverage ≥80% with an identity lower than 75%, red indicates a coverage lower than 75% that is interpreted as the absence of the paralogue. The genes are grouped according to the functional system: a exopolysaccharide metabolism, b sorbitol metabolism, c guanine derivative regulation, d desferrioxamine pathway, e type 1 secretion system, f type 3 secretion system, g others (transcription regulator, two-component transduction, positive regulator of virulence factor and sRNA chaperone). #These strains are Rosaceae-infecting apart from E. tasmaniensis ET1/99. The figure was rendered with the Krita software

Results and discussion

Herein, we supply an overview on the conservation of genes important for the pathogenicity of E. amylovora among different amylovora strains and other Erwinia strains with deposited genomes. In Fig. 1, a heatmap shows the absence (red, <80% coverage), or presence (green, ≥80% coverage and ≥75% identity; yellow, ≥80% coverage and <75% identity) of a specific gene (bottom) within a certain Erwinia strain (right), and also the hierarchical relationship between the strains and the analysis outcome (left). Information about the analyzed strains is reported in Table 1, where the habitat/host and the relative plant pathogenicity are specified.

General considerations

It is evident from the heatmap that there is a distinct separation between the group of Rosaceae-infecting strains (upper half of the figure) and the other strains. E. tasmaniensis ET1/99 is epiphytic and not pathogenic to plants and marks the boundary between the two groups (a wider discussion on this strain can be found below in a dedicated paragraph). The separation indicates that the genes involved in the Rosaceae-infecting strains are mostly not present, or present with a low sequence identity, in the strains not pathogenic to Rosaceae. This observation suggests that the proteins reported to be important for Erwinia amylovora pathogenicity are very specific to the fire blight development in Rosaceae.

Erwinia amylovora strains

Most of the analyzed E. amylovora strains look identical to each other. However, the Rubus-infecting strains E. amylovora Ea644 and MR1 make an exception.

First, our results show that these strains lack of the srlB gene. The srlB gene is part of the sorbitol operon and codifies for a protein (SrlB) responsible for sorbitol phosphorylation during translocation into the cell (Aldridge et al. 1997). Sorbitol phosphorylation by SrlB is necessary for its internalization so that it can be exploited in the biosynthesis pathway of the exopolysaccharide (EPS) amylovoran, which is the main protective biofilm component during infection (Aldridge et al. 1997; Langlotz et al. 2011). Interestingly, unless Spiraeoideae, the Rubus plants (e.g., raspberries and blackberries) contain little to no sorbitol (Lee 2015; Wallaart 1980). It has been demonstrated for five tested strains of E. amylovora that the pathogen is able to infect apple plants with the same severity independently of sorbitol concentration (Duffy and Dandekar 2007). Moreover, it has been shown that the inability of the cells to use the sorbitol in apple shoots prevented efficient colonization of host plant tissue (Aldridge et al. 1997). Therefore, the sorbitol operon confers the ability to cope with and take advantage of the high sorbitol concentrations present inside Spiraeoideae. Consequently, the Rubus-infecting strains are not able to deal with one of the main carbohydrate source (i.e., sorbitol) in Spiraeoideae, precluding their ability to infect these hosts.

Second, the rlsA gene is absent in E. amylovora MR1 and has <75% identity in E. amylovora Ea644 when compared to the reference gene of E. amylovora CFBP1430. The rlsA product is a regulator of levan production (Zhang and Geider 1999). Levan is required for the formation of a protective biofilm and its misregulation leads to impaired infectivity in apple (Koczan et al. 2009). Our observations rise the hypothesis about the inability of E. amylovora Ea644 and MR1 to infect Spiraeoideae.

Furthermore, Rezzonico et al. (2012) found differences within the lipopolysaccharide (LPS) gene cluster between a Rubus- and a Spiraeoideae-infecting strains of E amylovora and they suggested that the LPS gene cluster may be used as a molecular marker to distinguish between Rubus- and Spiraeoideae-infecting strains of E. amylovora (Rezzonico et al. 2012). Herein, we suggest that also the differences in the srlB and rlsA genes loci may be used together with the analysis of the LPS gene cluster to distinguish between Rubus- and Spiraeoideae-infecting strains.

Erwinia pyrifoliae Ep1/96, DSM-12163 and Erwinia sp. Ejp617

Erwinia pyrifoliae Ep1/96 and DSM-12163 are pathogens of Pyrus pyrifoliae and responsible of the Asian pear shoot blight (Geider et al. 2009; Park et al. 2011). The main difference with E. amylovora is that these strains have no levansucrase gene lsc3 and no PrtA metalloprotease type 1 secretion pathway genes prtDEF. It was shown that E. amylovora Δlsc3 mutant cells were not detected in the xylem vessels of apple trees and were reduced in moving through apple shoots (Koczan et al. 2009). In fact, the levansucrase allows E. amylovora to cope with the high level of sucrose present in the Rosaceous plants as principal storage and transport carbohydrate together with sorbitol (Bogs and Geider 2000; Geier and Geider 1993; Gross et al. 1992). While, the missing PrtA protease secretion was reported to reduce colonization of E. amylovora in the parenchyma of apple leaves (Zhang et al. 1999). Therefore, the lack of lsc3 and prtDEF genes may be correlated with the limited host-range and decreased virulence of E. pyrifoliae respect the fire blight-causing bacteria. The DSM-12163 strain is also missing the cysteine protease effector-gene avrRpt2, which is believed to have been acquired by E. amylovora after the separation from E. pyrifoliae species (Zhao et al. 2006). However, we found that E. pyrifoliae Ep1/96 harbors the avrRpt2 gene, indicating that the hypothesis about its acquisition should be still considered controversial.

Erwinia sp. Ejp617 is a pathogen of Pyrus pyrifolia and causes the bacterial shoot blight of pear (BSBP) (Park et al. 2011). It shows a heatmap profile similar to E. pyrifoliae DSM-12163, but it also lacks of the eop2 and the hsvC genes. Eop2 codifies for a type 3 secreted effector/helper protein bearing a pectate lyase domain (Asselin et al. 2006), while the missing hsvC (hrp-associated systemic virulence protein C) gene codifies for a carboxylate lyase required for full virulence in apple (Oh et al. 2005). These observations are consistent with the fact that Erwinia sp. Ejp617 is not able to cause fire blight and indicate that the eop2, hsvC, lsc3 and avrRpt2 genes are not necessary to infect Pyrus shoots, but discriminating when it comes to spread the infection to the whole plant.

Erwinia piriflorinigrans CFBP-5888

Erwinia piriflorinigrans is a Pyrus communis pathogen whose infection is limited to the blossoms (López et al. 2011; Roselló et al. 2006). Infected blossoms are similar in appearance to those affected by the fire blight caused by Erwinia amylovora. The E. piriflorinigrans CFBP-5888 strain is lacking of a number of genes present in E. amylovora.

The entire sorbitol operon is missing and can be related to its inability to infect the internal part of the plant. In fact, as already mentioned, the srl operon is important to exploit sorbitol within Spiraeoideae (Aldridge et al. 1997). The missing hrpY gene product is part of an upstream 2-component system regulating the hrp gene cluster together with HrpX (Wei et al. 2000). The latter works as a sensor protein and HrpY works as the response regulator partner. This means that in E. piriflorinigrans CFBP-5888 there is an impaired regulation of the hrp gene cluster.

The hsvABC genes are missing. They are required for full virulence in apple (Oh et al. 2005). Then, the missing hrpW gene codifies for a pectate lyase-like harpin protein and thereby is an effector of infection (Gaudriault et al. 1998). The missing avrRpt2 gene, as already mentioned, codifies for a cysteine protease T3SS effector important for virulence in apple trees (Zhao et al. 2006). Moreover, E. piriflorinigrans CFBP-5888 lacks the prtABCDE gene cluster. As previously discussed, the products of this cluster form a type 1 secretion system where the PrtA protein is a secreted metalloprotease demonstrated to influence the ability to colonize the parenchyma of apple leaves (Zhang et al. 1999). The missing eop1-2 genes encode for type 3 effector proteins, whose role remains unknown (Zhao and Qi 2011). Based on sequence divergence among Rubus or Spiraeoideae-infecting strains and mutational studies, Asselin et al. suggested that the Eop1/YopJ protein is a host-range-limiting factor that could act as a host specificity determinant towards, either Rubus, or Spiraeoideae (Asselin et al. 2011). In fact, sequencing of the orfA-eop1 regions of several strains of E. amylovora revealed that different forms of eop1 are conserved among strains with similar host ranges. In addition, mutational experiments showed that eop1 can otherwise influence virulence when heterologously expressed in Rubus or Spiraeoideae based on the strain it comes from. However, a transposon insertion mutant in the eop1 gene of the Spiraeoideae-infecting strain E. amylovora Ea273/ATCC-49946 (Ea273 eop1::Tn) caused symptoms similar to those of the wild-type strain. Therefore, it is plausible that the lack of eop1 has no effect on the infectivity of E. piriflorinigrans CFBP-5888. The missing edcE gene codifies for a diguanylate cyclase involved in the production of c-di-GMP, which positively regulates the secretion of amylovoran, leading to increase biofilm formation and negatively regulating flagellar swimming motility (Edmunds et al. 2013). The missing rlsB gene product is a positive regulator of levan synthesis and its absence may downregulate levansucrase expression and suppress levan production (Du and Geider 2002). The missing amsD gene codifies for a glycosyltransferase part of the amylovoran biosynthesis machinery. The AmsD protein attaches the second galactose residue to the growing repeating unit of the amylovoran precursor (Langlotz et al. 2011). Overall, the lack of both edcE, rlsB and amsD can lead to a lower or impaired EPS production in the E. piriflorinigrans CFBP-5888 strain that could correlate to the inability of this species to colonize the phloem. The missing ycfA gene codifies for a protein crucial for the 6-thioguanine (6TG) biosynthesis, which is a cytotoxin released from E. amylovora (Coyne et al. 2013). The ΔyfcA mutant revealed the crucial role of 6TG and, therefore, of YfcA in the development of the fire blight disease in apple plants.

Overall, our results on the E. piriflorinigrans CFBP-5888 strain suggest that the lack of the described genes may have drifted the pathogenicity towards Pyrus blossoms infections.

Intriguingly, the common missing genes among the Pyrus-infecting strains are restricted to the metalloprotease PrtA secretion system that, being an important player in the colonization of the parenchyma of apple, might represent one of the principal determinants in host specificity. On the other hand, we showed that the missing genes in E. piriflorinigrans CFBP-5888 are not necessary to infect blossoms.

Erwinia tasmaniensis ET1/99 strain

Erwinia tasmaniensis ET1/99 strain marks the border between the Rosaceae pathogens and the other strains. It is evident that E. tasmaniensis ET1/99 presents many similarities to the pear tree pathogen E. piriflorinigrans CFBP-5888. However, the ycfA, hrpW and hrpY genes are missing in E. piriflorinigrans CFBP-5888 and present in E. tasmaniensis ET1/99. Conversely, several genes that are present in the piriflorinigrans strain are missing in the tasmaniensis strain: dspF, hrpA, hrpK, amsE, amsK and edcC. Besides, the dspE gene in E. tasmaniensis ET1/99 has a <75% sequence identity compared to the reference sequence. Hence, the further absences of E. tasmaniensis ET1/99 may correlate to its inability to be infective. The disease specific (dsp) Hrp-associated pathogenicity-avirulence proteins DspE/A and DspF/B are among the principal effector in the fire blight disease and required for pathogenesis in Maloideae (Bogdanove et al. 1998; Gaudriault et al. 1997). The hrpA gene is part of the hrp operon, which is required for secretion of harpins and/or effectors and predicted to be an ATP-dependent helicase (Choi et al. 2013; Kim et al. 1997). The hrpK gene is part of the E. amylovora pathogenicity island. The codified protein HrpK is secreted and was suggested to be a translocator able to create channels in the plasma membrane of plant cells, although its actual function in fire blight remains to be determined (Oh et al. 2005). The amsE and amsK genes are part of the amylovoran-synthesis operon. The encoded AmsE and AmsK proteins are glucoside transferases that transfer the third and the last galactose residues, respectively, on the amylovoran precursor (Langlotz et al. 2011). Hence, their importance in proper amylovoran production and thereafter biofilm formations are clear. Eventually, as the edcE gene, the missing ecdC gene codifies for a diguanylate cyclase that positively regulates the secretion of amylovoran. Thereafter, the lack of genes whose products are considered to be critical for Rosaceae infection, well explain why the E. tasmaniensis ET1/99 strain is non-pathogenic respect the E. piriflorinigrans CFBP-5888 strain.

Non-Rosaceae pathogens and non-pathogens

Four strains, E. tracheiphila BuffGH, E. tracheiphila PSU-1, E. mallotivora BT-MARDI and E. persicina NBRC-102418, are reported to be pathogens of Cucurbitaceae (the first two), papaya tree and Leguminosae, respectively. However, they show no evident difference from the non-pathogenic strains in respect the heatmap outcome, again suggesting that most of the analyzed genes are not necessary for general pathogenesis, but they are host-specific. Only three genes (relA, dskA, csrA) have been found in most of the analyzed strains, pointing towards an important role besides pathogenesis. The relA gene codifies for a ribosome-associated protein engaged in the synthesis of ppGpp (Zhang and Geider 1999) and is present in all analyzed strains of Erwinia. The ppGpp interacts with the RNA polymerase (RNAP) to inhibit, or activate genes. The dskA gene product modulates the ppGpp-RNAP interaction enhancing the ppGpp effect (Ancona et al. 2015). The dksA gene is missing only in Erwinia sp. Leaf53. The csrA gene product is a post-transcriptional regulator of motility, amylovoran production, T3SS and virulence (Ancona et al. 2016). The csrA is not present in Erwinia sp. SCU-B244.

Conclusion

The Erwinia amylovora species can be divided into two host-specific groupings: the Spiraeoideae-infecting (e.g., Malus, Pyrus, Crataegus, Sorbus) and the Rubus-infecting strains such as E. amylovora Ea644 and MR1 (Mann et al. 2013). We suggest that the difference in host specificity could be correlated with the lack in the Rubus-infecting bacteria of a complete sorbitol operon. Thus, restricting the infectivity of E. amylovora Ea644 and MR1 to Rubus plants, which have little to no sugar alcohols, respect to other Rosaceae such as Malus and Pyrus (Lee 2015). Then, we suggested that the analysis of the srlB and rlsA loci may be used together with the analysis of the LPS gene cluster to distinguish between Rubus- and Spiraeoideae-infecting strains.

We hint that the host specificity of the Pyrus-infecting strains may be guided by the lack of genes involved in biofilm formation and virulence in apple. Intriguingly, all the Pyrus-infecting strains are impaired in the PrtA secretion system and, therefore, it would be interesting to investigate the virulence variation of E. amylovora apple infecting strains when mutated in the prt operon. Then, under the light of our observations, we advise that the hypothesis of the avrRpt2 acquisition after the phylogenetic separation of E. amylovora from E. pyrifoliae should be reconsidered. We discovered that the eop2, hsvC, lsc3 and avrRpt2 genes are not necessary to infect Pyrus shoots, but they are required for the whole plant infection. We proposed that the lack of both edcE, rlsB and amsD in E. piriflorinigrans CFBP-5888 might have drifted the pathogenicity towards Pyrus blossoms infections. Then, we suggest that the PrtA type 1 secretion system might represent one of the principal determinants in the host specificity towards the pear plants., Considering that the virulence of the Pyrus-infecting strains is lower than the virulence of the fire blight-causing bacteria (Smits et al. 2011; Zhao et al. 2006), we propose that their pathogenicity towards pear trees could be addressed to the loss of ability to infect apple trees due to the described gene loss, rather than to a spontaneous evolutionary drift towards a different host. However, more studies are needed to clarify this interesting issue.

Our observations on E. tasmaniensis ET1/99, which is an epiphytic bacterium marking the boundary with the Rosaceae-infecting and non-infecting bacteria, hint that the lack of genes whose products are considered to be crucial for Rosaceae infection, well explain why the E. tasmaniensis ET1/99 strain is non-pathogenic.

The most conserved genes among all the considered Erwinia strains are relA, dksA and csrA/rsmA. However, they are not always present, indicating that they are not necessary for survival, but important in Erwinia amylovora pathogenicity for their general role in regulating transcription and translation.

In conclusion, our results indicate that most of the analyzed genes are not necessary for general pathogenesis, but they are specific for the infection of Rosaceae plants. Future studies should aim to clarify the correlations highlighted within the presented work to increase our knowledge about host specificity and pathogenesis within the Erwinia genus.

Acknowledgements

The work was supported by the Fondazione Libera Università di Bolzano under the projects GenSelEa (Genomic Selection in Erwinia amylovora; Grant TN2052) and BioInfEa (BioInformatic analysis of Erwinia amylovora strains genome sequences; Grant TN2055). The authors thank Samuel Senoner (eurac/unibz) for IT technical support. The computational results presented have been achieved [in part] using the Vienna Scientific Cluster (VSC).

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Luigimaria Borruso and Marco Salomone-Stagni equally contributed.

References

- Aldridge P, Metzger M, Geider K. Genetics of sorbitol metabolism in Erwinia amylovora and its influence on bacterial virulence. Mol Gen Genet. 1997;2566:611–619. doi: 10.1007/s004380050609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ancona V, Li W, Zhao Y. Alternative sigma factor RpoN and its modulation protein YhbH are indispensable for Erwinia amylovora virulence. Mol Plant Pathol. 2013;15(1):58–66. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ancona V, Lee JH, Chatnaparat T, Oh J, Hong JI, Zhao Y. The bacterial alarmone (p)ppGpp activates the type III secretion system in Erwinia amylovora. J Bacteriol. 2015;1978:1433–1443. doi: 10.1128/JB.02551-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ancona V, Lee JH, Zhao Y. The RNA-binding protein CsrA plays a central role in positively regulating virulence factors in Erwinia amylovora. Sci Rep. 2016;6:37195. doi: 10.1038/srep37195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asselin JE, Oh CS, Nissinen RM, Beer SV. The Secretion of EopB from Erwinia amylovora. ISHS Acta Horticult. 2006;704:409–416. doi: 10.17660/ActaHortic.2006.704.65. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Asselin J, Bonasera J, Kim J, Oh C, Beer S. Eop1 from a Rubus strain of Erwinia amylovora functions as a host-range limiting factor. Phytopathology. 2011;1018:935–944. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-12-10-0339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai Y, Muller DB, Srinivas G, Garrido-Oter R, Potthoff E, Rott M, Dombrowski N, Munch PC, Spaepen S, Remus-Emsermann M, Huttel B, McHardy AC, Vorholt JA, Schulze-Lefert P. Functional overlap of the Arabidopsis leaf and root microbiota. Nature. 2015;5287582:364–369. doi: 10.1038/nature16192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baltrus DA, Dougherty K, Arendt KR, Huntemann M, Clum A, Pillay M, Palaniappan K, Varghese N, Mikhailova N, Stamatis D (2017) Absence of genome reduction in diverse, facultative endohyphal bacteria. Microb Genom 3(2):e000101. doi:10.1099/mgen.0.000101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bereswill S, Geider K. Characterization of the rcsB gene from Erwinia amylovora and its influence on exopolysaccharide synthesis and virulence of the fire blight pathogen. J Bacteriol. 1997;1794:1354–1361. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.4.1354-1361.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blow F, Gioti A, Starns D, Ben-Yosef M, Pasternak Z, Jurkevitch E, Vontas J, Darby AC. Draft genome sequence of the bactrocera oleae symbiont “Candidatus Erwinia dacicola”. Genome Announc. 2016;4(5):e00896-16. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00896-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogdanove AJ, Kim JF, Wei Z, Kolchinsky P, Charkowski AO, Conlin AK, Collmer A, Beer SV. Homology and functional similarity of an hrp-linked pathogenicity locus, dspEF, of Erwinia amylovora and the avirulence locus avrE of Pseudomonas syringae pathovar tomato. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;953:1325–1330. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.3.1325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogs J, Geider K. Molecular analysis of sucrose metabolism of Erwinia amylovora and influence on bacterial virulence. J Bacteriol. 2000;18219:5351–5358. doi: 10.1128/JB.182.19.5351-5358.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campillo T, Luna E, Portier P, Fischer-Le Saux M, Lapitan N, Tisserat NA, Leach JE. Erwinia iniecta sp. nov., isolated from Russian wheat aphid (Diuraphis noxia) Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2015;6510:3625–3633. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.000466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi M, Kim W, Lee C, Oh C. Harpins, multifunctional proteins secreted by Gram-negative plant-pathogenic bacteria. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 2013;2610:1115–1122. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-02-13-0050-CR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne S, Chizzali C, Khalil MN, Litomska A, Richter K, Beerhues L, Hertweck C. Biosynthesis of the antimetabolite 6-Thioguanine in Erwinia amylovora plays a key role in fire blight pathogenesis. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2013;125(40):10758–10762. doi: 10.1002/ange.201305595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Z, Geider K. Characterization of an activator gene upstream of lsc, involved in levan synthesis of Erwinia amylovora. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol. 2002;601:9–17. doi: 10.1006/pmpp.2001.0372. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy B, Dandekar A (2007) Sorbitol has no role in fire blight as demonstrated using transgenic apple with constitutively altered content. In: ISHS Acta Horticulturae 793: XI International Workshop on Fire Blight, pp 279–283

- Edmunds AC, Castiblanco LF, Sundin GW, Waters CM. Cyclic di-GMP modulates the disease progression of Erwinia amylovora. J Bacteriol. 2013;195(10):2155–2165. doi: 10.1128/JB.02068-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estes AM, Hearn DJ, Bronstein JL, Pierson EA. The olive fly endosymbiont, “Candidatus Erwinia dacicola,” switches from an intracellular existence to an extracellular existence during host insect development. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;7522:7097–7106. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00778-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaudriault S, Malandrin L, Paulin JP, Barny MA. DspA, an essential pathogenicity factor of Erwinia amylovora showing homology with AvrE of Pseudomonas syringae, is secreted via the Hrp secretion pathway in a DspB-dependent way. Mol Microbiol. 1997;265:1057–1069. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.6442015.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaudriault S, Brisset M, Barny M. HrpW of Erwinia amylovora, a new Hrp-secreted protein. FEBS Lett. 1998;4283:224–228. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(98)00534-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geider K, Auling G, Jakovljevic V, Völksch B. A polyphasic approach assigns the pathogenic Erwinia strains from diseased pear trees in Japan to Erwinia pyrifoliae. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2009;483:324–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2008.02535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geier G, Geider K. Characterization and influence on virulence of the levansucrase gene from the fireblight pathogen Erwinia-amylovora. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol. 1993;42:387–404. doi: 10.1006/pmpp.1993.1029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- González A, Tello J, Rodicio M. Erwinia persicina causing chlorosis and necrotic spots in leaves and tendrils of Pisum sativum in southeastern Spain. Plant Dis. 2007;914:460. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-91-4-0460A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross M, Geier G, Rudolph K, Geider K. Levan and levansucrase synthesized by the fireblight pathogen Erwinia-amylovora. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol. 1992;406:371–381. doi: 10.1016/0885-5765(92)90029-U. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gusberti M, Klemm U, Meier MS, Maurhofer M, Hunger-Glaser I. Fire blight control: the struggle goes on. A comparison of different fire blight control methods in Switzerland with respect to biosafety, efficacy and durability. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015;129:11422–11447. doi: 10.3390/ijerph120911422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JF, Wei ZM, Beer SV. The hrpA and hrpC operons of Erwinia amylovora encode components of a type III pathway that secretes harpin. J Bacteriol. 1997;1795:1690–1697. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.5.1690-1697.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein JM, Bennett RW, MacFarland L, Abranches Da Silva ME, Meza-Turner BM, Dark PM, Frey ME, Wellappili DP, Beugli AD, Jue HJ, Mellander JM, Wei W, Ream W. Draft genome sequence of Erwinia billingiae OSU19-1, isolated from a pear tree canker. Genome Announc. 2015;3(5):e1119-15. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.01119-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koczan JM, McGrath MJ, Zhao Y, Sundin GW. Contribution of Erwinia amylovora exopolysaccharides amylovoran and levan to biofilm formation: implications in pathogenicity. Phytopathology. 2009;9911:1237–1244. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-99-11-1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kube M, Migdoll AM, Muller I, Kuhl H, Beck A, Reinhardt R, Geider K. The genome of Erwinia tasmaniensis strain Et1/99, a non-pathogenic bacterium in the genus Erwinia. Environ Microbiol. 2008;109:2211–2222. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2008.01639.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kube M, Migdoll AM, Gehring I, Heitmann K, Mayer Y, Kuhl H, Knaust F, Geider K, Reinhardt R. Genome comparison of the epiphytic bacteria Erwinia billingiae and E. tasmaniensis with the pear pathogen E. pyrifoliae. BMC Genom. 2010 doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langlotz C, Schollmeyer M, Coplin DL, Nimtz M, Geider K. Biosynthesis of the repeating units of the exopolysaccharides amylovoran from Erwinia amylovora and stewartan from Pantoea stewartii. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol. 2011;754:163–169. doi: 10.1016/j.pmpp.2011.04.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. Sorbitol, Rubus fruit, and misconception. Food Chem. 2015;166:616–622. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.06.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B, Luo J, Li W, Long X, Zhang Y, Zeng Z, Tian Y. Erwinia teleogrylli sp. nov., a bacterial isolate associated with a Chinese cricket. PLoS One. 2016;11(1):e0146596. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0146596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López MM, Rosello M, Llop P, Ferrer S, Christen R, Gardan L. Erwinia piriflorinigrans sp. nov., a novel pathogen that causes necrosis of pear blossoms. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2011;613:561–567. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.020479-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Fernandez S, Sonego P, Moretto M, Pancher M, Engelen K, Pertot I, Campisano A. Whole-genome comparative analysis of virulence genes unveils similarities and differences between endophytes and other symbiotic bacteria. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:419. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann RA, Smits TH, Buhlmann A, Blom J, Goesmann A, Frey JE, Plummer KM, Beer SV, Luck J, Duffy B, Rodoni B. Comparative genomics of 12 strains of Erwinia amylovora identifies a pan-genome with a large conserved core. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e55644. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moretti C, Hosni T, Vandemeulebroecke K, Brady C, De Vos P, Buonaurio R, Cleenwerck I. Erwinia oleae sp. nov., isolated from olive knots caused by Pseudomonas savastanoi pv. savastanoi. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2011;6111:2745–2752. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.026336-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moretti C, Cortese C, Passos da Silva D, Venturi V, Firrao G, Buonaurio R (2014) Draft genome sequence of Erwinia oleae, a bacterium associated with olive knots caused by Pseudomonas savastanoi pv. savastanoi. Genome Announc 2(6):e 01308-14. doi:10.1128/genomeA.01308-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Nissinen RM, Ytterberg AJ, Bogdanove AJ, Van Wijk KJ, Beer SV. Analyses of the secretomes of Erwinia amylovora and selected hrp mutants reveal novel type III secreted proteins and an effect of HrpJ on extracellular harpin levels. Mol plant Pathol. 2007;81:55–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2006.00370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norelli JL, Jones AL, Aldwinckle HS. Fire blight management in the twenty-first century: using new technologies that enhance host resistance in apple|plant disease. Plant Dis. 2003;87(7):756–765. doi: 10.1094/PDIS.2003.87.7.756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh CS, Beer SV. Molecular genetics of Erwinia amylovora involved in the development of fire blight. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2005;2532:185–192. doi: 10.1016/j.femsle.2005.09.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh CS, Kim JF, Beer SV. The Hrp pathogenicity island of Erwinia amylovora and identification of three novel genes required for systemic infection. Mol Plant Pathol. 2005;62:125–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2005.00269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park DH, Thapa SP, Choi BS, Kim WS, Hur JH, Cho JM, Lim JS, Choi IY, Lim CK. Complete genome sequence of Japanese Erwinia strain ejp617, a bacterial shoot blight pathogen of pear. J Bacteriol. 2011;1932:586–587. doi: 10.1128/JB.01246-10. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Passos da Silva D, Devescovi G, Paszkiewicz K, Moretti C, Buonaurio R, Studholme DJ, Venturi V. Draft genome sequence of Erwinia toletana, a bacterium associated with olive knots caused by Pseudomonas savastanoi pv. Savastanoi. Genome Announc. 2013;1(3):e00205–e00213. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00205-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pester D, Milcevicova R, Schaffer J, Wilhelm E, Blumel S. Erwinia amylovora expresses fast and simultaneously hrp/dsp virulence genes during flower infection on apple trees. PLoS One. 2012;7(3):e32583. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piqué N, Miñana-Galbis D, Merino S, Tomás J. Virulence factors of Erwinia amylovora: a review. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;166:12836–12854. doi: 10.3390/ijms160612836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter D, Eriksson T, Evans RC, Oh S, Smedmark J, Morgan DR, Kerr M, Robertson KR, Arsenault M, Dickinson TA. Phylogeny and classification of Rosaceae. Plant Syst Evol. 2007;266(1/2):5–43. doi: 10.1007/s00606-007-0539-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team (2012) R: a language and environment for statistical computing. In: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. http://www.R-project.org/

- Redzuan RA, Abu Bakar N, Rozano L, Badrun R, Mat Amin N, Mohd Raih MF. Draft genome sequence of Erwinia mallotivora BT-MARDI, causative agent of papaya dieback disease. Genome Announc. 2014;2(3):e00375-14. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00375-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rezzonico F, Braun-Kiewnick A, Mann RA, Rodoni B, Goesmann A, Duffy B, Smits TH. Lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis genes discriminate between Rubus- and Spiraeoideae-infective genotypes of Erwinia amylovora. Mol Plant Pathol. 2012;138:975–984. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2012.00807.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rezzonico F, Smits TH, Born Y, Blom J, Frey JE, Goesmann A, Cleenwerck I, de Vos P, Bonaterra A, Duffy B. Erwinia gerundensis sp. nov., a cosmopolitan epiphyte originally isolated from pome fruit trees. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2016;663:1583–1592. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.000920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roselló M, Peñalver J, Llop P, Gorris M, Cambra M, López M, Chartier R, García F, Montón C. Identification of an Erwinia sp. different from Erwinia amylovora and responsible for necrosis on pear blossoms. Can J Plant Path. 2006;281:30–41. doi: 10.1080/07060660609507268. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro LR, Scully ED, Straub TJ, Park J, Stephenson AG, Beattie GA, Gleason ML, Kolter R, Coelho MC, De Moraes CM, Mescher MC, Zhaxybayeva O. Horizontal gene acquisitions, mobile element proliferation, and genome decay in the host-restricted plant pathogen Erwinia tracheiphila. Genome Biol Evol. 2016;83:649–664. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evw016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shtienberg D, Shwartz H, Oppenheim D, Zilberstaine M, Herzog Z, Manulis S, Kritzman G. Evaluation of local and imported fire blight warning systems in Israel. Phytopathology. 2003;933:356–363. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO.2003.93.3.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skrodenyte-Arbaciauskiene V, Radziute S, Stunzenas V, Buda V (2012) Erwinia typographi sp. nov., isolated from bark beetle (Ips typographus) gut. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 62(Pt 4):942–948. doi:10.1099/ijs.0.030304-0 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Smits TH, Rezzonico F, Duffy B. Evolutionary insights from Erwinia amylovora genomics. J Biotechnol. 2011;1551:34–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2010.10.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smits TH, Rezzonico F, Lopez MM, Blom J, Goesmann A, Frey JE, Duffy B. Phylogenetic position and virulence apparatus of the pear flower necrosis pathogen Erwinia piriflorinigrans CFBP 5888 as assessed by comparative genomics. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2013;36(7):449–456. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2013.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smits TH, Guerrero-Prieto VM, Hernandez-Escarcega G, Blom J, Goesmann A, Rezzonico F, Duffy B, Stockwell VO. Whole-genome sequencing of Erwinia amylovora strains from Mexico detects single nucleotide polymorphisms in rpsL conferring streptomycin resistance and in the avrRpt2 effector altering host interactions. Genome Announc. 2014;2(1):e01229-13. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.01229-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Zwet T, Biggs A, Heflebower R, Lightner G. Evaluation of the MARYBLYT computer model for predicting blossom blight on apple in West Virginia and Maryland. Plant Dis. 1994;783:225–230. doi: 10.1094/PD-78-0225. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Zwet T, Orolaza-Halbrendt N, Zeller W. Fire blight: history, biology, and management. St. Paul: APS Press/American Phytopathological Society; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Vanneste JL. Fire blight. New York: CABI; 2000. p. 10016. [Google Scholar]

- Wallaart RA. Distribution of sorbitol in Rosaceae. Phytochemistry. 1980;1912:2603–2610. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(00)83927-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D, Korban SS, Zhao Y. The Rcs phosphorelay system is essential for pathogenicity in Erwinia amylovora. Mol Plant Pathol. 2009;102:277–290. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2008.00531.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D, Korban SS, Pusey PL, Zhao Y. Characterization of the RcsC sensor kinase from Erwinia amylovora and other Enterobacteria. Phytopathology. 2011;1016:710–717. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-09-10-0258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Z, Kim JF, Beer SV. Regulation of hrp genes and type III protein secretion in Erwinia amylovora by HrpX/HrpY, a novel two-component system, and HrpS. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2000;1311:1251–1262. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2000.13.11.1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Q, McNally RR, Sundin GW. Global small RNA chaperone Hfq and regulatory small RNAs are important virulence regulators in Erwinia amylovora. J Bacteriol. 2013;1958:1706–1717. doi: 10.1128/JB.02056-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Geider K. Molecular analysis of the rlsA gene regulating levan production by the fireblight pathogen Erwinia amylovora. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol. 1999;54:187–201. doi: 10.1006/pmpp.1999.0198. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Nan Z. Erwinia persicina, a possible new necrosis and wilt threat to forage or grain legumes production. Eur J Plant Pathol. 2014;1392:349–358. doi: 10.1007/s10658-014-0390-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Bak DD, Heid H, Geider K. Molecular characterization of a protease secreted by Erwinia amylovora. J Mol Biol. 1999;2895:1239–1251. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Qi M. Comparative genomics of Erwinia amylovora and related Erwinia Species-what do we learn? Genes (Basel) 2011;23:627–639. doi: 10.3390/genes2030627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, He S, Sundin GW. The Erwinia amylovoraavrRpt2EA gene contributes to virulence on pear and AvrRpt2EA is recognized by Arabidopsis RPS2 when expressed in Pseudomonas syringae. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 2006;196:644–654. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-19-0644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]