Abstract

T-cell lymphoma invasion and metastasis 1 (Tiam1) is a Dbl-family guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) that specifically activates the Rho-family GTPase Rac1 in response to upstream signals, thereby regulating cellular processes including cell adhesion and migration. Tiam1 contains multiple domains, including an N-terminal pleckstrin homology coiled-coiled extension (PHn-CC-Ex) and catalytic Dbl homology and C-terminal pleckstrin homology (DH-PHc) domain. Previous studies indicate that larger fragments of Tiam1, such as the region encompassing the N-terminal to C-terminal pleckstrin homology domains (PHn-PHc), are auto-inhibited. However, the domains in this region responsible for inhibition remain unknown. Here, we show that the PHn-CC-Ex domain inhibits Tiam1 GEF activity by directly interacting with the catalytic DH-PHc domain, preventing Rac1 binding and activation. Enzyme kinetics experiments suggested that Tiam1 is auto-inhibited through occlusion of the catalytic site rather than by allostery. Small angle X-ray scattering and ensemble modeling yielded models of the PHn-PHc fragment that indicate it is in equilibrium between “open” and “closed” conformational states. Finally, single-molecule experiments support a model in which conformational sampling between the open and closed states of Tiam1 contributes to Rac1 dissociation. Our results highlight the role of the PHn-CC-Ex domain in Tiam1 GEF regulation and suggest a combinatorial model for GEF inhibition and activation of the Rac1 signaling pathway.

Keywords: enzyme kinetics, guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF), inhibition mechanism, Ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate 1 (Rac1), small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS), single-molecule total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy, Tiam1, auto-inhibition, in vitro GEF assays

Introduction

Rac1, a Rho family GTPase, functions as a molecular switch cycling between inactive GDP-bound and active GTP-bound states (1). In its active state Rac1 interacts with effector proteins to regulate signaling pathways controlling a variety of cellular processes including cell morphology, adhesion, migration, and invasion (2–5). Because overexpression and hyper-activation of Rac1 activity has been associated with metastasis, Rac1 is a potential therapeutic target for cancer treatment (6). The activation of Rho GTPases requires guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs),3 which catalyze the exchange of GDP to GTP. In general, GEFs are auto-inhibited in the cytosol through intramolecular interactions that occlude the catalytic domain. Relief of auto-inhibition occurs upon translocation to the membrane by protein/protein and/or protein/lipid interactions and phosphorylation (7). Understanding how GEFs are regulated could lead to novel therapeutic avenues for cancer treatment (8, 9).

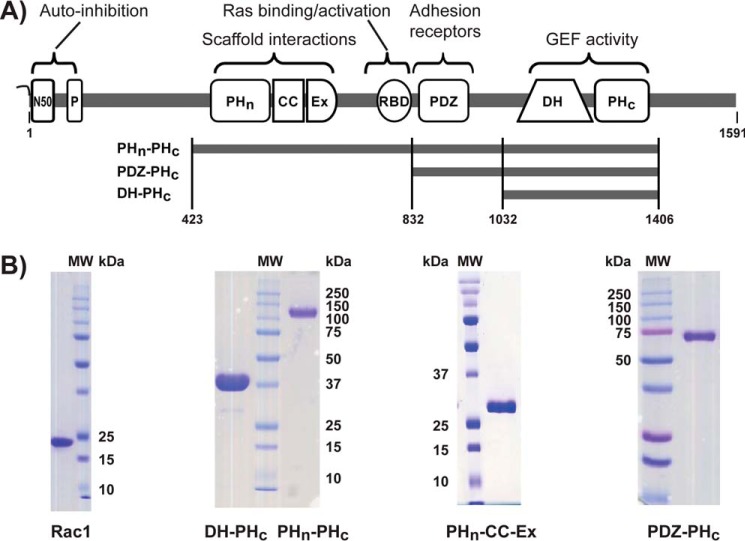

The T-cell lymphoma invasion and metastasis 1 (Tiam1) is a large multidomain Dbl-family GEF protein that specifically activates Rac1 (10, 11) (Fig. 1A). As a key activator of Rac1, the increased or decreased level of protein expression (12, 13) and deregulation of Tiam1 GEF activity has been implicated in oncogenic transformation of cells and several invasive and metastatic forms of cancer, including colorectal (14), colon (15), prostate (16), and breast cancer (17). Tiam1 contains a catalytic Dbl-homology (DH) and adjacent pleckstrin-homology (PH) domain, characteristic of Dbl-family GEFs. The DH-PH domain is the minimal region responsible for catalyzing GTP/GDP exchange by interacting with the canonical switch I and II regions of Rho GTPases, which ejects the bound guanine nucleotide (18). Moreover, the PH subdomain of the DH-PH domain regulates GEF activity through interactions with the DH domain, the Rho GTPase substrate, or phosphoinositides (19, 20). In addition to the catalytic DH-PH domain, Tiam1 contains multiple protein–protein binding domains (Fig. 1) that may provide additional mechanisms for regulating the catalytic activity of the DH-PH domain (7, 18). For instance, Tiam1 has an N-terminal PH subdomain that forms a single, continuous domain together with the coiled-coil extension (CC-Ex) subdomain (21, 22). The PHn-CC-Ex domain binds Par3 (2, 5), CD44 (21), ephrin (23), and JIP2 (24), and these interactions modulate Tiam1 subcellular localization and ultimately increase GEF activity by ∼2–3-fold. Activated (GTP-bound) H-Ras binding to the Tiam1 Ras-binding domain (RBD) has also been shown to activate GEF activity in cells (12, 25, 26).

Figure 1.

A schematic of Tiam1 domain architecture. A, myristoylation site is indicated by the twisting line at the N terminus. P, PEST region; PDZ, PSD-95/DlgA/ZO-1 domain. The N-terminal 50 amino acids (N50) are auto-inhibitory. B, SDS-PAGE gel of purified Rac1 and Tiam1 fragments used in this study.

Like other GEF proteins, phosphorylation plays a key role in Tiam1 regulation. Phosphorylation of tyrosine residue 829 within the RBD/PDZ linker by TrkB (27) and serine/threonine residues throughout Tiam1 increased GEF activity ∼2-fold (28, 29). In addition, serine and tyrosine phosphorylation of residues at the N terminus is associated with Tiam1 degradation (30, 31). These studies and previous observations (10, 32) suggest that the N terminus of Tiam1 is autoinhibitory. Indeed, a recent study by Kaibuchi and co-workers (33) showed that the first 50 residues at the N terminus (N50) inhibited Tiam1 GEF function by binding to the PHn-CC-Ex domain and, to a lesser extent, the catalytic DH-PHc domain. Furthermore, phosphorylation of serine residues within N50 by the aPKCγ kinase relieved auto-inhibition.

The crystal structures of individual domains found in Tiam1, such as the PHn-CC-Ex (21, 22), PDZ (34) and DH-PHc (35), have been determined. However, structures of full-length Tiam1, active or inhibited, have not been elucidated. In addition, the question of whether supplementary suppressive interactions beyond N50 occur in Tiam1 has not been addressed to date. In this study we focused on a large fragment of Tiam1 (PHn-PHc) that contains all of the folded domains. We measured the in vitro GEF activity of several truncated Tiam1 constructs to examine the role of the structured domains in regulating GEF function. We found that the PHn-CC-Ex domain directly inhibited the catalytic function of the DH-PHc domain. In addition, we determined the enzyme kinetics parameters for Tiam1 GEF function and identified the mechanism for auto-inhibition of Tiam1 GEF activity. We used small angle X-ray scattering to generate structural models of the Tiam1 PHn-PHc fragment. The structural models revealed a multilayered, auto-inhibitory mechanism that involves the PHn-CC-Ex domain, the RBD domain, and interdomain linkers. These results show that these regulatory domains occupy the Rac1-binding sites that are crucial for the GEF activity of Tiam1. Taken together, our results provide new insight into the mechanism by which the GEF activity of Tiam1 is auto-inhibited.

Results

Expression and characterization of Tiam1 protein fragments

To investigate the role of structured domains in regulating GEF catalytic activity, we constructed a series of fragments with sequentially deleted domains (Fig. 1A). The designed Tiam1 protein fragments were expressed and purified to homogeneity (Fig. 1B). The Tiam1 fragments were analyzed by a variety of methods to determine their oligomeric state and stability in solution before biochemical and structural experiments. Analytical size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) of the DH-PHc and PHn-PHc fragments indicated an apparent molecular weight of ∼43 and 115 kDa, respectively (supplemental Table S1 and Fig. S1, A and B), consistent with a monomeric state in solution. Moreover, dynamic light scattering (DLS) provided an estimate of the hydrodynamic radius (Rh) and polydispersity (Pd) of the proteins in solution. Comparison of Rh values determined by SEC and DLS suggested that Tiam1 proteins are relatively compact but elongated (supplemental Tables S1 and S2). The low polydispersity value (<11%) of the DH-PHc and PHn-PHc proteins indicated that they were homogeneous (supplemental Table S2 and Fig. S1C). Thus, the Tiam1 fragments were verified to be monomeric, homogeneous, and aggregation-free in solution.

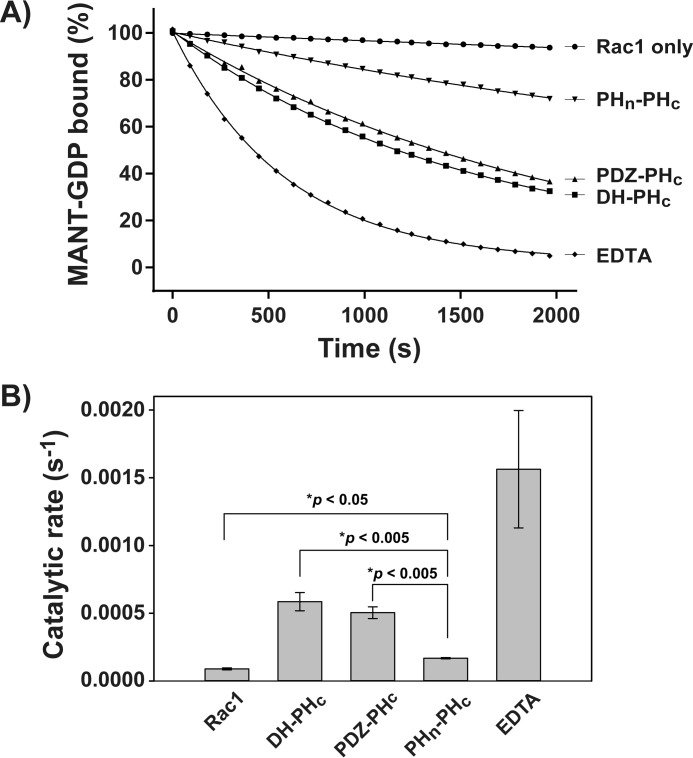

Deletion of Tiam1 structured domains promotes GEF activity

Full-length Tiam1 (residue 1–1591) GEF activity is auto-inhibited (32). The N50 of full-length Tiam1 inhibits its localization and GEF activity through an interaction with the PHn-CC-Ex domain and, to a lesser extent, with the DH-PHc domain (33). However, it is not known whether other structured domains participate in the auto-inhibition of Tiam1. As an initial step toward identifying the potential inhibitory domain(s) in Tiam1, we performed in vitro GEF exchange assays to measure the nucleotide exchange activity of several deletion constructs. In these experiments, the nucleotide exchange reactions were initiated by adding truncated Tiam1 fragments: DH-PHc (residues 1032–1406), PDZ-PHc (residues 832–1406), and PHn-PHc (residues 423–1406) individually (Fig. 1). The measured nucleotide exchange activity of Rac1 without Tiam1 served as a reference for intrinsic exchange activity, whereas EDTA, which chelates the bound magnesium ion in Rac1 leading to maximal exchange of MANT-GDP, served as a positive control. We found that all of the Tiam1 fragments (DH-PHc, PDZ-PHc, and PHn-PHc) stimulated nucleotide exchange activity of Rac1 compared with the intrinsic nucleotide exchange activity of Rac1 alone (Fig. 2A). There was no significant change in stimulated exchange activity between the DH-PHc and PDZ-PHc fragments, indicating that the PDZ domain has no effect on inhibition of Tiam1 GEF activity (Fig. 2B). Further bolstering this conclusion, the addition of the isolated PDZ domain did not change the GEF activity of the catalytic DH-PHc domain (supplemental Fig. S2). In contrast, the observed catalytic activity of the PHn-PHc fragment was 3-fold lower than the DH-PHc fragment, indicating auto-inhibition (Fig. 2B). Taken together, these data indicate that the PHn-CC-Ex and/or the RBD domain, but not the PDZ domain, participate in the inhibition of Tiam1 GEF activity in vitro.

Figure 2.

Tiam1 was auto-inhibited by structured domains located N-terminal of the catalytic DH-PHc domain. A, the exchange of MANT-GDP from Rac1 was measured in the presence of Tiam1 DH-PHc, PDZ-PHc, or PHn-PHc fragments. Rac1 alone and EDTA were negative and positive controls, respectively. Data represent the average of three independent reactions for each trace. B, quantification of Tiam1 catalyzed exchange reactions. *, determined by a pairwise t test assuming equal variances.

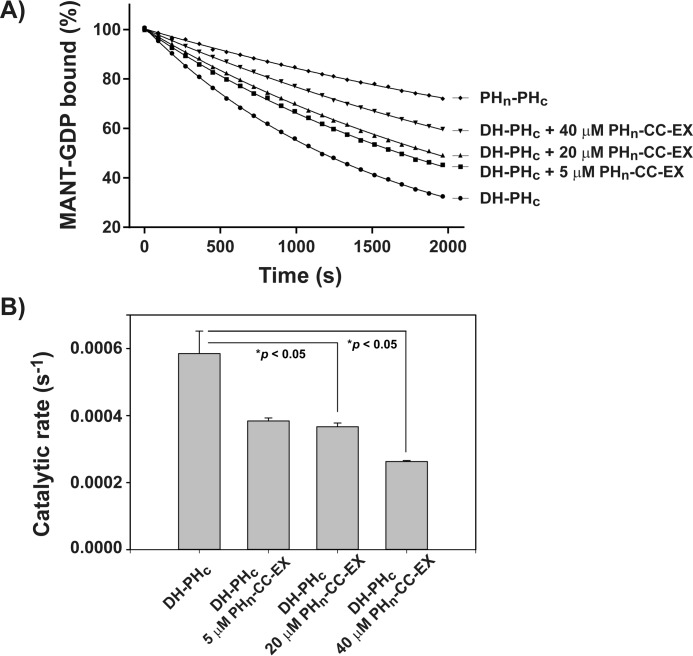

The PHn-CC-Ex domain inhibits Tiam1 GEF activity

To validate the role of the PHn-CC-Ex domain in Tiam1 auto-inhibition, we conducted in vitro GEF exchange assays with the DH-PHc domain in the presence of increasing amounts (5, 20, and 40 μm) of the isolated PHn-CC-Ex fragment (Fig. 3). The results showed that the GEF function of the DH-PHc fragment was decreased ∼2-fold at the highest concentration of the PHn-CC-Ex fragment used in this assay. In contrast, titration of 20 μm BSA did not change the nucleotide exchange activity of Rac1 (supplemental Fig. S3A). In addition, titration of 20 μm concentrations of the PHn-CC-Ex fragment to Rac1 in the absence of the DH-PHc fragment did not show a change of nucleotide exchange activity, indicating that the PHn-CC-Ex domain has no direct effect on Rac1 (supplemental Fig. S3B). We conclude that the PHn-CC-Ex region directly binds to the DH-PHc domain to inhibit its GEF function.

Figure 3.

The Tiam1 PHn-CC-Ex domain directly inhibited the GEF activity of the catalytic DH-PHc domain. A, the exchange of MANT-GDP from Rac1, as monitored by the fluorescence intensity, was measured in the presence of Tiam1 DH-PHc alone or mixed with increasing concentrations of the PHn-CC-Ex fragment. The Tiam1 DH-PHc protein in the presence of the PHn-CC-Ex fragment showed reduced activity compared with Tiam1 DH-PHc domain alone. B, quantification of Tiam1 catalyzed exchange reactions. *, determined by a pairwise t test assuming equal variances.

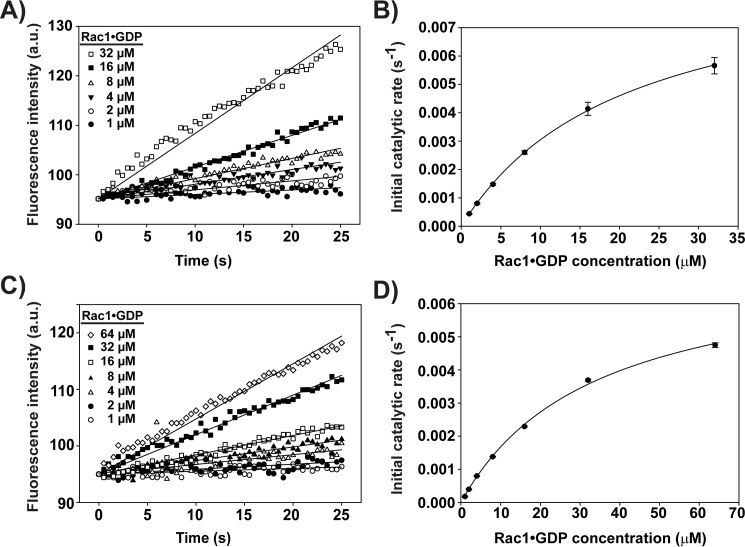

Enzyme kinetics of inhibited and active Tiam1 proteins

As shown above, the structured domains within the PHn-PHc fragment inhibited the GEF activity of the DH-PHc domain through interdomain interactions. We hypothesized that the decrease of GEF activity could be due to a decrease of Rac1-binding affinity (competitive model) and/or the inhibition of catalysis (non-competitive or allosteric model). To clarify which model was pertinent, we determined the kinetics parameters (Km and Vmax) of GEF activity for the Tiam1 DH-PHc or PHn-PHc constructs using a fluorescence-based enzymatic kinetics assay. The general enzymatic mechanism of RhoGEFs has been described previously as “ping-pong bi-bi,” having two substrates (Rac1–GDP complex and free MANT-GDP) and two products (Rac1–MANT-GDP complex and free GDP) (36, 37). Therefore, the initial velocity is dependent on the concentration of two substrates. At a saturating concentration of one substrate, the relationship of initial velocity to the second substrate concentration follows the Michaelis-Menten equation. However, we could not use a saturating concentration of MANT-GDP because of limitations in signal detection over the required concentration range needed for the analysis. Instead, a more robust analysis can be performed by titrating one substrate (e.g. Rac1–GDP) at several subsaturating concentrations of the second substrate (MANT-GDP) (36). Thus, in the fluorescence-based enzymatic assays, a fixed concentration of Tiam1 proteins (DH-PHc or PHn-PHc) was used while varying the concentration of Rac1–GDP performed at two different subsaturating concentrations of MANT-GDP (0.5 or 1 μm). The initial velocity of each reaction was determined by fitting the initial 25 s to a line (Fig. 4, A and C). The initial velocities were plotted against the concentration of Rac1–GDP and fitted to the Michaelis-Menten equation (Equation 1) to determine the apparent Vmax and Km values (Fig. 4, B and D),

| (Eq. 1) |

Figure 4.

Enzyme kinetics of inhibited and active Tiam1 proteins. A and C, progress of Tiam1 DH-PHc or PHn-PHc (0.5 μm) catalyzed exchange reactions in the presence of Rac1 (1–32 μm for DH-PHc or 1–64 μm for PHn-PHc). The changes in fluorescence intensity corresponding to Tiam1-mediated exchange of MANT-GDP were monitored over time. a.u., arbitrary fluorescence units. B and D, plot of specific activity of Tiam1 DH-PHc or PHn-PHc as a function of Rac1 concentration. The data were fit to the Michaelis-Menten equation to determine the apparent Km and Vmax kinetic parameters.

The apparent Michaelis-Menten constants (appKm, (Tiam1-Rac1)) and maximum velocities (appVmax, (Tiam1-Rac1)) at two concentrations (0.5 and 1 μm) of MANT-GDP were used to calculate the true Michaelis-Menten constant (trueKm, (Tiam1-Rac1)) and maximum velocity (trueVmax (Tiam1-Rac1)) using Equations 2 and 3,

| (Eq. 2) |

| (Eq. 3) |

where [MANT-GDP] represents the concentration of MANT-GDP, and Km, MANT-GDP represents the concentration of MANT-GDP at which the catalytic rate is half the true Vmax when [Rac1–GDP] is saturated. Tables 1 and 2 summarize the apparent and true kinetic parameters determined for the Tiam1 catalyzed nucleotide exchange reactions. We found that the trueVmax (and kcat) values for the DH-PHc and PHn-PHc fragments were not statistically different. In contrast, the trueKm value of the PHn-PHc fragment was ∼2.4-fold higher than that of the DH-PHc fragment. These data indicate that the inhibition of Tiam1 GEF function occurs through a competitive model whereby the PHC-CC-Ex and RBD domains inhibit the DH-PHc domain by decreasing Rac1-binding affinity.

Table 1.

Summary of apparent Tiam1 DH-PHc and PHn-PHc guanine nucleotide exchange enzyme parameters

| [MANT-GDP] | appKm | appVmax | appKm | appVmax |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| μm | μm s−1 | μm | μm s−1 | |

| 0.5 μm | 21.4 ± 0.9 | 9.5 ± 0.3 × 10−3 | 35.3 ± 4.4 | 8.6 ± 0.7 × 10−3 |

| 1 μm | 29.4 ± 3.5 | 13.6 ± 0.9 × 10−3 | 53.8 ± 7.1 | 12.8 ± 1.2 × 10−3 |

Table 2.

Summary of true Tiam1 DH-PHc and PHn-PHc guanine nucleotide exchange enzyme parameters

| Protein | trueKm | trueVmax | truekcat |

|---|---|---|---|

| μm | μm s−1 | s−1 | |

| DH-PHc | 47.0 ± 7.5 | 23.9 ± 2.3 × 10−3 | 47.8 ± 4.6 × 10−3 |

| PHn-PHc | 113.0 ± 29.0 | 25.0 ± 4.4 × 10−3 | 49.9 ± 8.8 × 10−3 |

SAXS analysis of Tiam1 fragments

To uncover the organization of Tiam1 structured domains relative to the DH-PHc domain and their potential regulation of the GEF activity, we conducted SAXS-based structural characterization of three fragments (DH-PHc, PDZ-PHc, and PHn-PHc). SAXS data were collected at two beamlines using different approaches. SAXS data for the three Tiam1 constructs (DH-PHc, PDZ-PHc, and PHn-PHc) were collected at the SIBYLS beamline 12.3.1 (Advanced Light Source, Berkeley, CA) on a static sample (no stirring or flow) at several protein concentrations (1–5 mg/ml) and exposure times (0.5, 1, 2, 4 s; data collected in this order). Except for the highest concentration and exposure time, all datasets were free of radiation damage and did not show any concentration-dependent effects (data not shown). The scattering data were buffer-subtracted, averaged, and merged for further data analysis and model construction. Only the PDZ-PHc dataset was included in subsequent ensemble modeling analyses.

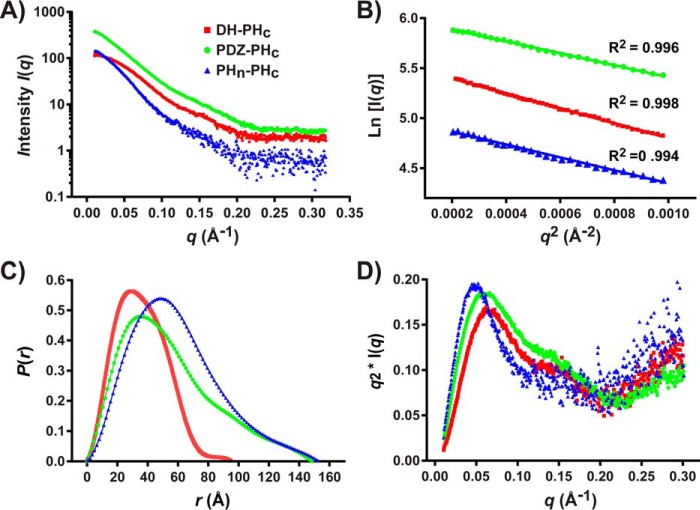

SAXS data for the DH-PHc and PHn-PHc were also collected at the BioCAT beamline 18-ID-D (Advanced Photon Source, Chicago, IL) using an in-line size-exclusion chromatography-SAXS (SEC-SAXS) configuration, which involved elution of the sample from a FPLC system into a quartz capillary flow cell for X-ray scattering. Using this configuration, data from the monomeric peak were averaged and buffer corrected and used for further analysis. Although the data collected at the Advanced Photon Source (APS; Argonne, IL) and Advanced Light Source (ALS; Berkeley, CA) were of high quality and yielded very similar structural parameters, we chose to use the data collected at the APS for the Tiam1 DH-PHc and PHn-PHc fragments for further analysis because SEC-SAXS data ensures optimal sample quality. A summary of the SAXS data collection and the determined structural parameters is shown in Table 3, whereas the experimental scattering profiles used for further analysis are shown in Fig. 5A. The Guinier analysis of the low scattering region (q × Rg < 1.3) was linear for all Tiam1 fragments (Fig. 5B), suggesting that they were free of aggregation. The Guinier analysis also provided an estimate of the radius of gyration (Rg) and forward scattering intensity, I(0) (Table 3). Using the forward scattering intensity and protein concentration along with several standard proteins, we determined the apparent molecular weight of each Tiam1 fragment (supplemental Table S3). Consistent with the analytical SEC, the oligomerization state of all Tiam1 fragments in solution was found to be monomeric. The distance distribution function, P(r), Rg, and maximum particle dimension (Dmax) of all Tiam1 proteins were calculated using the program GNOM (38) (Fig. 5C and Table 3). The Rg values calculated from the Guinier analysis and GNOM were consistent, further demonstrating the high quality of the SAXS data. The Rg/Dmax ratio provides an estimate of the anisotropy of each protein and ranged from 0.301 to 0.285 (39). For reference, a sphere would have a ratio of 0.390 ((3/5)1/2 × R), where R is the radius of the sphere. These data indicate that the three constructs are anisotropic, with the PDZ-PHc fragment being the most elongated. The Kratky analysis of the scattering data indicated that all Tiam1 proteins had folded structure, but the increase of the curve at high q range suggests that they also have regions of flexibility, particularly the PHn-PHc fragment (Fig. 5D). Taken together, the SAXS structural parameters (Rg and Dmax) indicate that the Tiam1 fragments contain structured domains with flexible regions. Importantly, these data also show that the DH-PHc and PHn-PHc fragments are relatively compact.

Table 3.

Analysis of Tiam1 SAXS structural parameters

Mr, Sequence, theoretical molecular mass calculated from amino acid sequence; Mr, SAXS, molecular mass estimated from SAXS using Porod volume; Rg*, radius of gyration, estimated in reciprocal space from the Guinier plot; Rg**, radius of gyration, estimated in real space using the program GNOM; Dmax, the maximum dimension, estimated using the program GNOM; Porod volume, the particle volume calculated from Porod's law.

Figure 5.

SAXS analysis of Tiam1 proteins. A, experimental SAXS profiles (logarithmic scale) for Tiam1 PDZ-PHc was collected at ALS, whereas the Tiam1 DH-PHc and PHn-PHc datasets were collected at the APS (see “Experimental procedures” for details). B, comparison of a Guinier plot at low q-range (q < 1.3/Rg). The intensity is represented by the relationship I(q) = I(0)exp(−(q × Rg)2/3). The curves were arbitrarily scaled for clarity. The calculated reciprocal space Rg values are presented in Table 3. C, normalized pair distribution function, P(r), for Tiam1 DH-PHc, PDZ-PHc, and PHn-PHc calculated in AutoGNOM. D, normalized Kratky plots for Tiam1 DH-PHc, PDZ-PHc, and PHn-PHc.

SAXS-based modeling of Tiam1 proteins

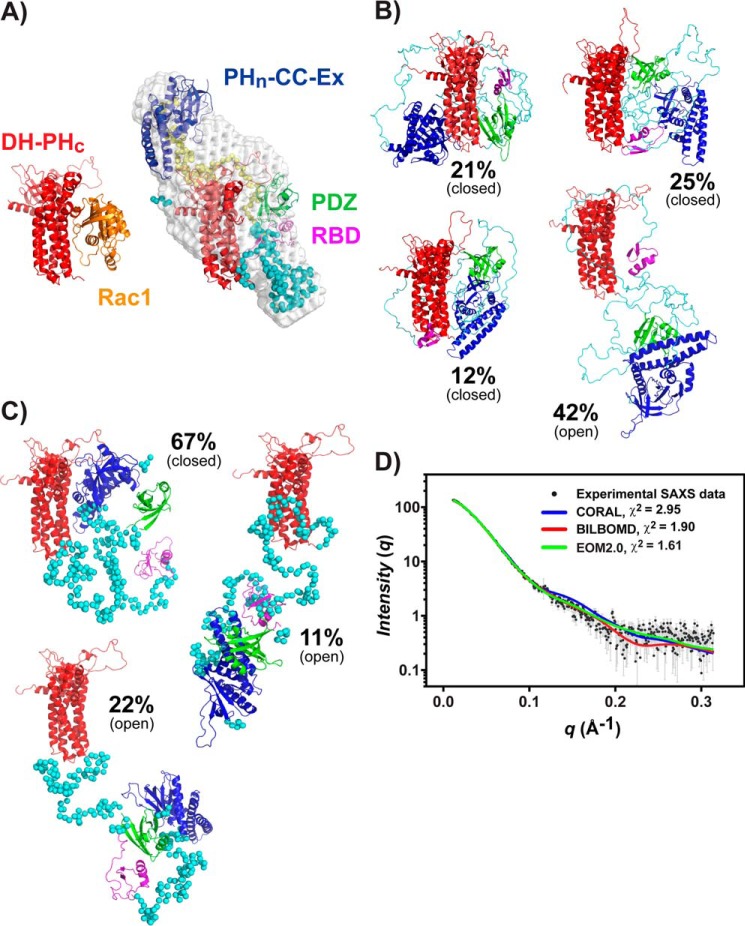

To understand how intramolecular interactions suppress the GEF activity of the Tiam1 PHn-PHc fragment, we created SAXS-based structural models using ab initio and rigid body approaches. The ab initio molecular envelope reconstruction of the three Tiam1 fragments from the experimental data were obtained and averaged using the programs DAMMIN (40) and DAMAVER (41). For simplicity, we will focus on the PHn-PHc fragment. Twenty-four independent runs of DAMMIN with the lowest normalized spatial discrepancy were averaged by DAMAVER to derive a representative molecular envelope of the PHn-PHc fragment (Table 4). The averaged envelope revealed that the Tiam1 PHn-PHc fragment has a compact, but elongated shape in solution (Fig. 6A). To gain further insight into the relative orientation of the domains, we used the program CORAL (42) to generate an atomic model of Tiam1 PHn-PHc fragment based on known crystal structures of individual domains and perform rigid body fitting of this model to the SAXS data. Comparison of the scattering curve of rigid body model derived from CORAL and the experimental SAXS data yielded a χ2 = 2.95 (χ2free = 5.83), indicating only modest agreement (Fig. 6D). Interestingly, visual inspection of the superimposed rigid body model onto the molecular envelope showed that the RBD domain and the linker connecting the RBD and PDZ domains occupy the Rac1-binding site in the DH-PHc domain, occluding Rac1 binding (Fig. 6A).

Table 4.

Summary of Tiam1 SAXS model refinement parameters

NSD, normalized spatial discrepancy; χ2 and χ2free, discrepancy of predicted scattering curve with the experimental data. χ2 was calculated by the program FoXS and χ2free was determined by the program ScÅtter.

| Protein |

Ab initio model |

Rigid body model |

Ensemble model |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BILBOMD |

EOM 2.0 |

||||||

| NSD | χ2 | χ2free | χ2 | χ2free | χ2 | χ2free | |

| DH-PHc | 0.593 ± 0.035 | 2.15 | 2.56 | ||||

| PDZ-PHc | 0.625 ± 0.023 | 13.80 | 16.02 | 1.14 | 1.79 | 1.81 | 2.24 |

| PHn-PHc | 0.631 ± 0.015 | 2.95 | 5.83 | 1.90 | 2.61 | 1.60 | 1.80 |

Figure 6.

SAXS-based structural models of Tiam1 PHn-PHc. A, ab initio model of Tiam1 PHn-PHc protein from SAXS data using DAMMIN and rigid-body modeling in CORAL. B, ensemble structural models for Tiam1 PHn-PHc determined by the program BILBOMD. C, ensemble structural models for Tiam1 PHn-PHc determined by the program EOM2.0. D, comparison of experimental scattering curve and the fitted scattering curves for Tiam1 PHn-PHc based on the rigid-body model (CORAL) and ensemble models (BILBOMD and EOM2.0).

To characterize the dynamic nature of the linkers and to explore additional conformations of the Tiam1 PHn-PHc fragment, we used the programs BILBOMD (43) and EOM2.0 (44) to identify structural ensembles that best fit the experimental SAXS data. A weighted ensemble of four and three conformations was found for the Tiam1 PHn-PHc fragment by BILBOMD (χ2 = 1.90; χ2free = 2.61) and EOM 2.0 (χ2 = 1.61; χ2free = 1.80), respectively (Table 4 and Fig. 6). The four representative conformations in BILOBOMD can be classified into closed and open states, representing 60 and 40% of the population, respectively (Fig. 6B). Similarly, the conformations identified by EOM2.0 were either closed or open, distributed ∼70 and 30%, respectively (Fig. 6C). Closer inspection of the distribution of Rg and Dmax values from EOM2.0 confirmed two conformations (supplemental Fig. S7). Comparison of the EOM2.0 and BIOBOMD PHn-PHc ensembles showed a common feature where the closed conformation prevents access of Rac1 to the DH-PHc domain, whereas the open conformation allows Rac1 access to the DH-PHc catalytic-binding site. Notably, the models show that Rac1 access to the DH-PHc domain is blocked by the RBD and PHn-CC-Ex domains.

Characterization of Tiam1-Rac1-binding kinetics by single molecule total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy

To assess the interaction kinetics of the Tiam1 DH-PHc and PHn-PHc fragments, we used single-molecule TIRF microscopy. Fig. 7A shows a schematic of the single-molecule TIRF experimental setup. The Tiam1 fragment (DH-PHc or PHn-PHc) was immobilized onto a glass slide by N-terminal biotinylation, and Rac1 was labeled at its C terminus with the Cy3 fluorophore through an aldehyde tag. Control experiments indicated that the biotin label had no effect on GEF exchange activity of the PHn-PHc fragment and a small effect on the DH-PHc domain (supplemental Fig. S8). In addition, the C-terminal aldehyde tag (LCTPSR) had no effect on GEF exchange activity (supplemental Fig. S8).

Figure 7.

Single-molecule TIRF experiments of Tiam1/Rac1 kinetic interactions. A, schematic of the single-molecule TIRF experiment. N-terminally biotinylated Tiam1 DH-PHc (gray) or PHn-PHc constructs were tethered to the PEG-passivated slide surface through a biotin/neutravidin interaction. Cy3-labeled Rac1 was introduced to the chamber, and the Cy3 fluorescence monitored as Rac1-Cy3 entered the evanescent wave. Persistence of the fluorescence signal for at least three frames within a diffraction limited spot was indicative of Rac1 binding to the Tiam1 DH-PHc or PHn-PHc construct. B and C, representative traces of the Tiam1 DH-PHc/Rac1 and Tiam1 PHn-PHc/Rac1 interaction. The raw fluorescence signal is shown as a green line. The black line represents the idealized fit of the data using hidden Markov modeling, from which bound and unbound durations were determined. D and E, histogram of binned data for each Rac1 protein concentration and the global fit of the data to a double exponential decay function. Insets are the residuals of the globally fit data. AU, arbitrary fluorescence units.

Several hundred to thousands of single-molecule–binding events were tracked by TIRF microscopy for multiple concentrations of Rac1-Cy3 (Fig. 7, B and C). Global fitting of the binned binding data yielded relatively short-lived complexes (koff) for both Tiam1 DH-PHc and PHn-PHc fragments (Fig. 7, D and E, and Table 5). Two types of complexes (with fast and slow dwell times) were observed for both the PHn-PHc and DH-PHc constructs. The DHn-PHc construct showed ∼84% of the events corresponded to the fast fraction, whereas 16% were slower events. In contrast, binding events for the PHn-PHc construct were more evenly distributed, with ∼60 and ∼40% of the events corresponding to fast and slow fractions, respectively. Due to the relatively low affinity of the complexes and the necessary use of high concentrations of labeled Rac1 protein, we were not able to reliably measure the association kinetics (kon). Specifically, frequent events of Rac1 diffusion through the diffraction-limited spot around the surface-tethered PHn-PHc (or DH-PHc) prevented reliable assignment of binding events.

Table 5.

Analysis of Tiam1/Rac1 interaction kinetics by single-molecule TIRF

| Protein | koff (fast) | koff (slow) | Fast fraction | Slow fraction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| s−1 | s−1 | |||

| PHn-PHc | 2.947 ± 0.056 | 0.739 ± 0.032 | 59.9 | 40.1 |

| DH-PHc | 8.050 ± 0.025 | 1.400 ± 0.009 | 84.3 | 15.7 |

Discussion

GEF proteins are generally regulated by auto-inhibition through intramolecular interactions that occlude the catalytic domain. However, the mechanistic details of auto-inhibition for individual GEF proteins varies such that detailed investigations are required to elucidate common mechanistic themes. The simplest mechanism of auto-inhibition results from steric occlusion of the GTPase by the PH domain within the DH-PH catalytic domain (45). As the PH subdomain binds phophoinositides, phosphorylation of phophoinositide moieties and membrane association can influence GEF regulation (45). However, the degree to which a PH subdomain regulates nucleotide exchange activity is variable among GEFs (45). Auto-inhibition by intramolecular interactions mediated by phosphorylation is a second common mechanism (45). The Vav RhoGEF is an excellent example. Vav is held in a closed, auto-inhibited state by the interaction of multiple domains within the protein. Phosphorylation of several tyrosine residues within an acidic region of Vav is the first event required for relief of auto-inhibition. Once phosphorylation occurs, displacement of other domain-domain contacts ensues (46–49). This hierarchical mechanism involving tiers of regulation may also be pertinent in other GEFs, including Tiam1 (45).

Like other RhoGEF proteins, Tiam1 is a multidomain protein whose activity is auto-inhibited. Tiam1 is composed of several structured domains and unstructured N and C termini (Fig. 1). The structure of the DH-PHc domain in complex with nucleotide-free Rac1 shows that the PHc subdomain does not contact Rac1, suggesting relatively little regulation by this PH domain (35). However, studies in cells show that the PHc subdomain has an important effect on GEF activity through interactions with the membrane (50, 51). Moreover, the N-terminal most 50 amino acids (N50) of Tiam1 inhibit its GEF activity by directly binding the PHn-CC-Ex domain and to a lesser extent the catalytic DH-PHc domain (33). Nevertheless, observations that Tiam1 can be activated by protein interactions through the PHn-CC-Ex and RBD domains and phosphorylation (Tyr-829) suggest that there may be additional levels of inhibition (21, 25, 27, 32). Here, we explored the possibility that additional regions, beyond N50, are inhibitory to Tiam1's GEF activity.

Tiam1 is inhibited by the PHn-CC-Ex domain

Using in vitro guanine nucleotide exchange assays on several Tiam1 truncation constructs (PHn-PHc, PDZ-PHc, and DH-PHc), we determined that the PHn-CC-Ex and RBD regions are critical for full Tiam1 GEF activity (Fig. 2). This was corroborated by experiments where titration of the isolated PHn-CC-Ex domain directly inhibited the GEF activity of the DH-PHc catalytic domain (Fig. 3). These data indicate that the PHn-PHc construct, which does not contain the N50 region, is auto-inhibited and that the PHn-CC-Ex region directly binds to and inhibits access of Rac1 to the catalytic DH-PHc domain. This finding indicates that Tiam1 is inhibited by multiple suppressive interactions that encompass a large portion of its N terminus that includes both the N50 and PHn-CC-Ex regions.

To address the mechanism of Tiam1 inhibition, we determined the enzyme kinetics of fully active (DH-PHc) and inhibited (PHn-PHc) Tiam1 constructs. We considered two possible mechanisms: allosteric regulation and steric occlusion. The kinetics data revealed that the Vmax values were similar for the DH-PHc and PHn-PHc fragments, whereas the Km values were significantly different (Fig. 4 and Tables 1 and 2). These data support a model where the PHn-CC-Ex and RBD regions sterically occlude Rac1 from the catalytic site in the DH-PHc domain, resulting in auto-inhibition. Consistent with this model, previous studies showed that truncation of the N-terminal 392 residues of Tiam1 (ΔN392) or protein/protein interactions involving the PHn-CC-Ex and RBD domains activate the Tiam1 GEF function in cells (21, 25, 27, 32).

Structural basis for Tiam1 auto-inhibition

We conducted SAXS-based characterization of several Tiam1 fragments to determine the structural basis for GEF auto-inhibition. Analysis of the DH-PHc, PDZ-PHc, and PHn-PHc SAXS data showed that all the fragments possessed regions of structure. The DH-PHc region was compact relative to the PDZ-PHc and PHn-PHc fragments, which were much more extended. Even though the PHn-PHc construct had nearly doubled the molecular weight of the PDZ-PHc construct, the two fragments had similar molecular dimensions (Rg and Dmax). These data suggest that the PHn-PHc construct, although somewhat extended, is more compact than the PDZ-PHc fragment.

Ensemble modeling of Tiam1 PDZ-PHc and PHn-PHc SAXS data provided additional insight. Analysis of the PDZ-PHc SAXS data and structural models showed an elongated conformation in which the PDZ domain is away from the DH-PHc domain and Rac1 is readily accessible for catalysis (supplemental Fig. S9). This structural model is fully consistent with our biochemical data that showed the PDZ domain has no effect on the Tiam1 GEF function compared with the DH-PHc domain. In contrast, ensemble models of the Tiam1 PHn-PHc fragment provide a more complex picture. In particular, the SAXS-based structural ensembles support two general conformations: an elongated, open conformation accessible to Rac1 and a compact, closed conformation inaccessible to Rac1. Inspection of the EOM2.0 and BILBOMD models (Fig. 6) indicates that in the closed conformation, the PHn-CC-Ex and RBD domains combine to occlude the catalytic DH-PHc domain. Interestingly, the distribution of these two states based on Rg or Dmax suggests that the two conformations exist in a relative proportion of ∼58–67% closed and 33–42% open states (Figs. 6 and supplemental Fig. S7). Although the SAXS-based models are of low resolution, they are fully consistent with the biochemical data and suggest a possible mechanism for how the PHn-CC-Ex and the RBD regions inhibit Tiam1 GEF activity.

Single-molecule experiments support two conformations in the Tiam1 PHn-PHc fragment

Single-molecule experiments in principle can provide a wealth of information about the kinetics of molecular processes. Here, we established a simple assay to assess the binding kinetics between the Tiam1 DH-PHc and PHn-PHc fragments and Rac1. The single molecule analysis of “on” dwell times yielded koff rate constants for both the DH-PHc and PHn-PHc fragments. For the PHn-PHc construct, the “on” dwell time distributions best fit two “off” rate constants (koff,fast and koff,slow) where the fast and slow rates had a 0.60 and 0.40 fraction, respectively. These two rate constants are indicative of the presence of two bound species with distinct dwell times. Similarly, the DH-PHc single molecule data were best fit using two “off” rate constants (koff,fast and koff,slow) where the fast process comprised the largest (∼0.84) fraction. Unfortunately, we were unable to reliably determine the association rate constant (kon). However, assuming a typical protein kon between 105 and 106 m−1s−1 (52–54), the Kd range for the fast process is ∼3–30 μm for PHn-PHc and 8–80 μm for DH-PHc. This dissociation constant is on the order seen for other GEF complexes (37) and similar in magnitude to the Kms determined for the PHn-PHc and DH-PHc constructs (Table 2). Thus, for the PHn-PHc construct, the most likely origin of the fast koff kinetic process is dissociation of Rac1 from the open state. Interestingly, the SAXS data indicate that the PHn-PHc is in equilibrium between the open and closed states, roughly in a 60% to 40% distribution, respectively. Therefore, the slow koff kinetic process may reflect the conformational change of the PHn-PHc construct from the open to the closed state with concomitant dissociation of Rac1. A similar explanation could be argued for the DH-PHc construct; however, here dissociation or Rac1 occurs primarily from the open, DH domain-accessible state. The slower koff likely reflects dissociation of Rac1 that occurs due to a more limited conformational change of the PHc subdomain to form a semi-closed state in the DH-PHc domain. Together, the single-molecule binding experiments provide support for two kinetic processes that reflect the conformational equilibrium between open and closed states in the PHn-PHc construct.

Model for Tiam1 auto-inhibition and activation

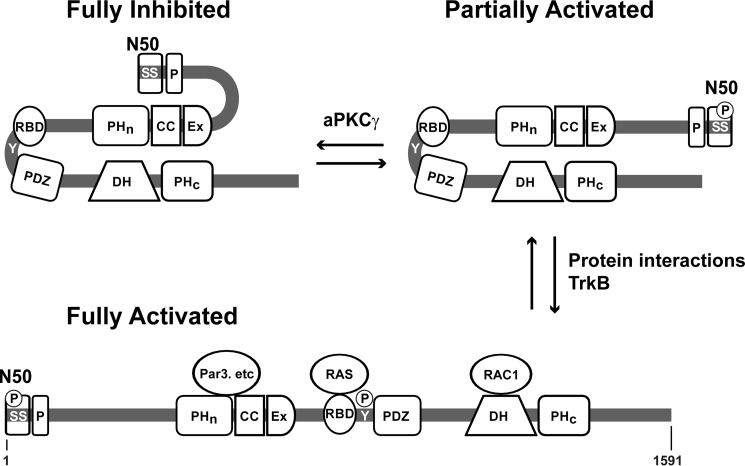

Early cell biological studies of Tiam1 revealed that truncation of ∼400 amino acids of the N terminus promoted GEF activity (10, 32, 55). The origin of this auto-inhibition was recently determined to be the N-terminal 50 amino acids (N50), which contains an aPKCγ phosphorylation site (33). The authors proposed a model whereby Tiam1 is biased in a closed, auto-inhibited state through the interaction of the N50 region and the PHn-CC-Ex domain. Upon phosphorylation of N50 (at Ser-29) by aPKCγ and engagement of the PHn-CC-Ex region with Par3 (or other binding partners), Tiam1 opens to yield an active conformation with an exposed DH-PHc domain. Here, we show that the PHn-CC-Ex also plays a critical role in promoting and stabilizing the closed state by physically interacting with the DH-PHc domain. We propose a combinatorial model for Tiam1 regulation (Fig. 8). This combinatorial model highlights that inhibition and activation are multistep processes with regulation at distinct levels. At present, we presume that the both modes of inhibition, through N50 and PHn-CC-Ex, are compatible. Future work will focus on investigating the activity of full-length Tiam1 to determine the relationship between these two modes of inhibition (i.e. whether or not they are coupled).

Figure 8.

Combinatorial model of Tiam1 auto-inhibition and activation. Full-length Tiam1 is in equilibrium between inactive and fully auto-inhibited forms, where the N50 and the PHn-CC-Ex domain combine to prevent Rac1 from accessing the catalytic DH-PHc domain. Full Tiam1 activation likely follows multiple steps: 1) phosphorylation of Ser-29 and Ser-33 by aPKCγ releases the PHn-CC-Ex/N50 interaction; 2) phosphorylation of Tyr-829 (by protein kinases TrkB etc.) and/or protein/protein interactions between of the PHn-CC-Ex and/or RBD domains with partner proteins (e.g. Par3 and Ras, respectively) relieving the PHn-CC-Ex/DH-PHc interaction. Once fully activated, Tiam1 interacts with Rac1 to promote GDP to GTP nucleotide exchange and downstream signaling.

Conclusion

Here we present a series of novel findings regarding the mechanism and structural basis of Tiam1 GEF auto-inhibition. We determined that the Tiam1 PHn-PHc fragment can be auto-inhibited in the absence of N50 (33). In addition, we showed that the PHn-CC-Ex domain alone inhibits Tiam1 GEF function in vitro. Our results establish a novel mechanism for auto-inhibition of Tiam1 by intramolecular interactions through the PHn-CC-Ex domain. We determined the enzyme kinetics of Tiam1-catalyzed nucleotide exchange reactions on Rac1 and found that inhibition occurs by a competitive model where the auto-inhibition is due to a lower substrate-binding affinity rather than inhibition of catalysis. SAXS-based ensemble structural models suggested that the PHn-PHc fragment exits in an equilibrium between a compact, closed conformation that is auto-inhibited and an open, GEF active conformation. Finally, single-molecule experiments validate this model of conformational equilibrium between two states. Taken together, the work described here supports a novel mechanism for Tiam1 GEF auto-inhibition whereby the PHn-CC-Ex domain blocks the Rac1-binding site on the catalytic DH-PHc domain. Our data also suggest a combinatorial model of regulation, where auto-inhibition and activation of Tiam1 is a multilayered process involving multiple factors, including phosphorylation and protein/protein interactions.

Experimental procedures

Protein expression and purification

Human Rac1 fragment (residues 1–181, C178S), human Tiam1 DH-PHc (residues 1032–1406), PDZ-PHc (residues 832–1046), and PHn-PHc (residues 423–1406) fragments were cloned into the NdeI and XhoI restriction sites of a modified pET21a vector (Novagen) that encodes an N-terminal 6× histidine tag followed by a recombinant tobacco etch virus (rTEV) protease cleavage site (ENLYFQG). The PHn-CC-Ex (residues 423–702) domain was cloned into pQE30-GB1 vector (Qiagen) that encodes an N-terminal 6× histidine tag followed by a GB1 domain and rTEV protease cleavage site (22). Rac1 protein expression was performed in Escherichia coli strain BL21(DE3) (Novagen), whereas Tiam1 proteins (DH-PHc, PDZ-PHc, and PHn-PHc) were expressed in E. coli strain RosettaTM (DE3) (Novagen). Tiam1 PHn-CC-Ex protein expression was achieved in E. coli strain M15 (Qiagen). All protein expression was induced using 0.5 mm isopropyl 1-thio-d-glactopyranoside (IPTG) at 20 °C overnight. All proteins were purified by nickel-affinity chromatography (nickel-Sepharose 6 fast flow media, GE Healthcare) and subsequently treated with recombinant TEV protease at 4 °C overnight to remove the N-terminal 6× histidine tag. Further purification was performed by anion exchange chromatography (Q FF media, GE Healthcare) and size-exclusion chromatography (Superdex 75 for Tiam1 DH-PHc, PHn-CC-Ex, and Rac1, and Superdex 200 for Tiam1 PDZ-PHc and PHn-PHc), which was equilibrated and run in a buffer containing 50 mm Tris (pH 7.5), 150 mm NaCl, 5% glycerol, and 5 mm dithiothreitol (DTT). In addition, 50 mm arginine and 50 mm glutamic acid was included in the buffer to stabilize the Tiam1 PHn-PHc fragment (56–58). The purified proteins were concentrated and stored at −80 °C.

Analytical size-exclusion chromatography

100 μl of Tiam1 DH-PHc and PHn-PHc proteins at 5 mg/ml was loaded onto a Superdex 200 HR 10/300 column running at flow rate of 0.5 ml/min. The elution of protein was monitored by UV absorbance at a wavelength of 280 nm. The column was equilibrated in a buffer consisting of 150 mm NaCl, 20 mm Tris (pH 7.5), 5 mm DTT, and 5% glycerol. The molecular weight and hydrodynamic radius (Rh) of the Tiam1 DH-PHc and PHn-PHc proteins were estimated by comparing their elution volume (Ve) to a standard curve determined from proteins of known hydrodynamic radii and molecular masses ranging between 13.6 and 670 kDa (supplemental Fig. S1 and Table S1).

Dynamic light scattering

DLS measurements of Tiam1 samples were performed using a DynaPro NanoStar instrument (Wyatt Technology). Tiam1 samples at 1–5 mg/ml were filtered using a 0.1-μm filter (Anotop 10; Whatman) to remove large aggregates. Eight microliters of each Tiam1 sample was added to a disposable plastic cuvette (Wyatt Technology) pre-equilibrated in the sample chamber at 25 °C. Light scattering was detected at 658 nm with a fixed detection angle of 90 °, and the data were collected at 25 °C. For each acquisition, scattering was measured every second for 50 s. For each measurement, 10 acquisitions were averaged to determine the mean value. The buffer was set to 5% glycerol in the DYNAMICS (Wyatt Technology) software to match the sample conditions. Changes in the intensity of scattered light over time derived from the random motions of molecules in solution were processed by the autocorrelation function. The autocorrelation function was averaged and analyzed using the software package DYNAMICS (Wyatt Technology). The hydrodynamic radius (Rh) was determined by relating diameter to the translational diffusion coefficient using the Stokes-Einstein relation (Equation 4),

| (Eq. 4) |

where κ is the Boltzmann's constant, T is temperature (K), and η is solvent viscosity (supplemental Table S2). Polydispersity (Pd) was used to estimate the relative size distribution of molecular species in solution. The percent polydispersity (% Pd) is given in Equation 5,

| (Eq. 5) |

where Pd is polydispersity, and R̄h is the mean value of hydrodynamic radius. All %Pd calculations were performed using the software package DYNAMICS (Wyatt Technology).

Preparation of MANT-GDP–bound Rac1

Rac1 preloaded with fluorescent GDP analogue 2′(3′)-O-(N-methylanthraniloyl) guanosine diphosphate (MANT-GDP) (Sigma) was prepared as described previously (59, 60). One hundred nanomoles of purified Rac1 was incubated at room temperature for 30 min with 3-fold molar excess of MANT-GDP in 1 ml buffer (20 mm Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm DTT, 5 mm EDTA, and 5% glycerol). Next, the nucleotide exchange reaction was terminated by adding 30 μl of 0.5 m MgCl2 (final concentration of 15 mm) to the Rac1/MANT-GDP mixture and incubated for 10 min at room temperature. Size-exclusion chromatography (PD-10 column, GE Healthcare) was used to separate free MANT-GDP from the Rac1–MANT-GDP complex while simultaneously exchanging the buffer into 20 mm Tris (pH 7.5), 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm DTT, 5 mm MgCl2, and 5% glycerol. The fractions containing the Rac1–MANT-GDP complex were identified and quantified using the bicinchoninic acid assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and SDS-PAGE analysis. The pooled Rac1–MANT-GDP complex was stored at 4 °C covered in foil and used within 2 weeks.

In vitro quantitative guanine nucleotide exchange assays

All guanine nucleotide exchange experiments were performed on a spectrofluorimeter (Fluorolog-3, Horiba) using a buffer containing 20 mm Tris (pH 7.5), 150 mm NaCl, 5 mm MgCl2, 5% glycerol, and 1 mm DTT at 25 °C. Solutions of Rac1–MANT-GDP complex (final concentration of 2 μm) were equilibrated in a 2-ml cuvette (quartz SUPRASIL, Hellma Analytics) for 5 min at 25 °C before kinetics assays. The nucleotide exchange reaction was triggered by adding the Tiam1 construct (final concentration of 1 μm) in the presence of excess (20 μm) unlabeled GDP. The MANT fluorescence signal was monitored using an excitation and emission wavelength of 360 and 450 nm, respectively. All nucleotide exchange experiments were performed using two independent protein preparations with at least duplicate measurements. The observed decrease of the fluorescence signal due to the release of MANT-GDP from Rac1 was fitted to a single exponential decay function to determine the exchange reaction rate (λ = 1/t) and half-time (t½) of GEF activity using Equations 6 and 7,

| (Eq. 6) |

| (Eq. 7) |

where Nt is the fluorescence intensity at time t, and N0 is the initial intensity at time t = 0, τ is the exponential time constant, λ is the catalytic rate, and t½ is the half-life, which is the time required for the amplitude to be one-half of its initial value (59).

Fluorescence-based enzyme kinetics assay

Enzyme kinetics parameters for Tiam1-catalyzed nucleotide exchange reactions were determined using fluorescence-based experiments that measure the increase in fluorescence signal following the incorporation of MANT-GDP into Rac1 over time (36, 37). The kinetics values measured for Tiam1 acting on the Rac1–GDP substrate in these experiments include the Michaelis-Menten constant (Km(Tiam1-Rac1–GDP)), the maximum velocity (Vmax(Tiam1-Rac1–GDP)), and the rate-limiting rate constant (kcat). Experiments were performed at 25 °C on a spectrofluorimeter (Fluorolog3, Horiba) using an excitation wavelength of 360 nm and an emission wavelength of 450 nm for MANT-GDP in a buffer containing 20 mm Tris (pH 7.5), 150 mm NaCl, 5 mm MgCl2, 5% glycerol, and 1 mm DTT. A catalytic amount (0.5 μm) of Tiam1 protein (enzyme) was added to trigger the guanine nucleotide exchange reaction as a function Rac1–GDP complex (substrate) concentration (1–32 μm for DH-PHc and 1–64 μm for PHn-PHc) in the presence of a fixed concentration of MANT-GDP (0.5 μm or 1 μm). The total amount of exchanged MANT-GDP-bound Rac1 in solution was directly proportional to the total fluorescence intensity change (supplemental Fig. S4). The factor for converting fluorescence intensity change to the amount of MANT-GDP bound Rac1 is expressed in Equation 8,

| (Eq. 8) |

where [MANT-GDP]ex is the amount of exchanged MANT-GDP, and ΔFL is the change of fluorescence intensity. The conversion factor in this study was determined to be 146.2 ± 2.2 arbitrary fluorescence units/μm MANT-GDP. The exchange of MANT-GDP over the first 25 s of the reaction was fitted by the slope (ΔFL/time) to determine the initial reaction rate.

| (Eq. 9) |

The plot of initial reaction rates versus Rac1–GDP concentration was fitted to the Michaelis-Menten kinetics equation to determine the apparent Km and Vmax values. The “true” kinetic values were determined using the apparent kinetic values determined at two MANT-GDP concentrations (see below).

Analysis of Tiam1 nucleotide exchange enzyme kinetics experiments

Tiam1-catalyzed nucleotide exchange reaction follows a “ping-pong bi-bi” mechanism having two substrates (Rac1–GDP and free MANT-GDP) and two products (Rac1–MANT-GDP and free GDP). The initial catalytic rate for a two-substrate reaction is shown in Equation 10,

| (Eq. 10) |

where A = Km(Rac1–GDP)[MANT-GDP], B = Km(MANT-GDP)[Rac1–GDP], C = [Rac1–GDP][MANT-GDP], ν is the initial catalytic rate, Vmax is the maximum velocity, [Rac1–GDP] and [MANT-GDP] are the concentrations of the two substrates, and Km(Rac1–GDP) and Km(MANT-GDP) are the Michaelis-Menten constants for the two substrates (36, 37). If the concentration of MANT-GDP is held constant at a subsaturated concentration, then the concentration of the Rac1–GDP complex can be varied. Under these conditions, the catalytic rate for Tiam1 can be expressed in terms of the apparent Vmax and apparent Km(Rac1–GDP) (Equation 11),

| (Eq. 11) |

Rearranging Equation 11 in terms of the true Vmax and true Km(Rac1–GDP) yields equations 12 and 13.

| (Eq. 12) |

| (Eq. 13) |

Because only the Km(MANT-GDP) is unknown, the true Vmax and Km(Rac1–GDP) values can be calculated by obtaining the apparent Vmax and Km values at two different concentrations of MANT-GDP (36, 37). Finally, the calculated true Vmax value and concentration of Tiam1 can be used to determine the rate-limiting rate constant (kcat) of Tiam1 for Rac1–GDP using Equation 14,

| (Eq. 14) |

where [Tiam1] is the concentration of Tiam1, and Vmax is the maximum velocity of Tiam1-catalyzed nucleotide exchange of Rac1–GDP.

Statistical analysis

Unless indicated, all data are representative of at least three independent experiments. Results are expressed as the means ± S.E. from multiple experiments. Student's t test was used to determine the statistical significance (two-tailed p value < 0.05).

SAXS data collection

All Tiam1 proteins were dialyzed extensively into SAXS buffer (20 mm Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mm NaCl, 5 mm Tris(2-carboxyethyl) phosphine (TCEP), 5% glycerol) before data collection. The buffer for the Tiam1 PHn-PHc fragment also contained 50 mm arginine and 50 mm glutamic acid to stabilize the protein (56–58). SAXS data were collected at the SIBYLS beamline 12.3.1 at the ALS and BioCAT beamline 18-ID-D at the APS). All SAXS samples were examined by DLS before data collection at the ALS SIBYLS beamline (supplemental Fig. S1). SAXS data collection at the ALS (SIBYLS beamline) was performed at 10 °C on a static sample using a protein concentration range of 1–5 mg/ml. Data were recorded using a MAR 165 area detector (Rayonix) covering a q-range of 0.004 < q < 0.35 Å−1 (q = 4π/λ sinθ, where 2θ is the scattering angle). Several exposure times (0.5–4 s) were used for data collection for all samples. The data reduction was performed automatically using custom scripts to generate radially averaged scattering curves of normalized intensity versus q value. The SAXS data obtained at the APS (BioCAT beamline 18-ID-D) were collected at room temperature using an in-line SEC-SAXS configuration (61) with a Superdex 200 10/300 GL Increase column (GE Healthcare). A volume of 250 μl containing a 10 mg/ml sample was loaded onto the column at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min. The elution trajectory was redirected after the UV monitor into the SAXS sample flow cell. Scattering data were collected every 3 s using a 1-s exposure on a Pilatus 3 1 m pixel detector (DECTRIS) covering a q-range of 0.004 < q < 0.33 Å−1. For each protein, the buffer scattering before the eluted peak was recorded and used for background correction. Data from the main peak were averaged and corrected for buffer scattering to obtain the final protein scattering curves (supplemental Fig. S5).

SAXS data processing and modeling

After data reduction and buffer subtraction, the SAXS data were further analyzed using the ATSAS software package (42, 62). The buffer-corrected data obtained at different protein concentrations were analyzed separately to determine concentration-dependent effects on structural parameters. The forward scattering intensity, I(0), and the radius of gyration (Rg) were calculated from the Guinier plot using the program PRIMUS (63), part of the ATSAS software package. PRIMUS was also used to compute the Kratky plot and pair distribution function, P(r). The Porod volume was computed using the Porod invariant in the program PRIMUS and GNOM (44). The molecular weight (Mr) of each Tiam1 fragment was estimated using the forward scattering intensity and known concentration by comparison to a protein standard using Equation 15,

| (Eq. 15) |

where Mr, p is the molecular weight of the Tiam1 protein of interest, Mr, st is the theoretical molecular weight of the standard protein, I(0) is the forward scattering intensity at zero scattering angle, and C is protein concentration (mg/ml) (64). The standard proteins used for the determination of molecular mass were xylanase (21 kDa), BSA (66.4 kDa), and glucose isomerase (173 kDa) (supplemental Fig. S6).

The low resolution ab initio models of Tiam1 proteins were constructed from the experimental SAXS data using the program DAMMIN (40). To assess the stability of the models, 24 independent modeling runs were performed in the program DAMMIN, and the results were averaged in DAMAVER (41). The rigid body model for the PHn-PHc fragment was constructed in the program CORAL (42) using the high resolution crystal structures of individual domains (PHn-CC-Ex, PDB 3A8N (21); PDZ, PDB 3KZD (34); DH-PHc, PDB 1FOE (35) and a homology model of the RBD domain generated using the program Phyre2 (65) with the Raf RBD domain (PDB 4G3X) (65) as a template). The missing linkers between domains were modeled as “dummy residues.”

The programs BILBOMD (43) and Ensemble Optimization Method (EOM2.0) (44) were used to generate ensemble models of the PDZ-PHc and PHn-PHc fragment. The input for BILBOMD was a full-atomic model of the PDZ-PHc and PHn-PHc fragment built using the known crystal structures (see above) connected by loops and linkers modeled in the program Loopy (Dr. Adrian Elcock, University of Iowa; Refs. 66 and 67). The input for EOM2.0 was the crystal structures of individual domains (see above) alone, as the software generates all loops and linkers. Both programs use an ensemble approach to generate a large pool (∼10,000) of candidate conformations and select a small group of representative conformations consistent with the SAXS data. A representative ensemble was chosen by identifying multi-conformational SAXS profiles that produce a minimal χ value when compared with the experimental scattering curve. The χ value is the goodness-of-fit between the experimental data and the calculated theoretical SAXS curves (Equation 16),

| (Eq. 16) |

where M, σ, and c are the number of data points, the standard deviations of data points, and the scaling factor, respectively. The calculation of theoretical scattering curves for the rigid body models was performed by the program FoXS (48), which also determines the discrepancy (χ value) between the simulated and experimental scattering curves. In addition, the χfree parameter (68), which assesses the model/data agreement, was calculated in the program ScÅtter (R. P. Rambo; www.bioisis.net).4

Protein expression and purification of Rac1-aldehyde tag and biotinylated Tiam1 proteins

Rac1 was labeled with the Cy3 fluorophore by the addition of an “aldehyde tag” (LCTPSR) and generation of an aldehyde via the action of formylglycine-generating enzyme (FGE) (69). In cells, FGE efficiently recognizes the aldehyde tag and catalyzes the enzymatic conversion of the cysteine residue within the tag to an aldehyde-containing formylglycine, fGly (69, 70). The Rac1-aldehyde tag plasmid (mpET21a Rac1-aldehyde) was generated using PCR with a 3′-primer that included the six-residue aldehyde tag into the C terminus of Rac1 (1–181, C178S). This plasmid also contained an N-terminal rTEV-cleavable 6× histidine tag. E. coli RosettaTM (DE3) (Novagen) cells containing the Rac1-aldehyde and FGE plasmids (69, 70) were incubated in LB media at 37 °C until the absorbance at 600-nm wavelength reached 0.3, at which time FGE expression was induced with 0.02% (w/v) arabinose. After 30 min, the temperature was lowered to 18 °C, and expression of the Rac1-aldehyde protein was induced using 0.1 mm IPTG overnight. Biotinylated Tiam1 DH-PHc and PHn-PHc plasmids were generated by introducing an E. coli BirA ligase recognition sequence (GLNDIFEAQKIEWHE) (71) between an N-terminal 6× histidine tag cleavable with rTEV and Tiam1 DH-PHc and PHn-PHc fragments in a modified pET21 vector (Novagen). The Tiam1 plasmids were transformed in E. coli RosettaTM (DE3) (Novagen) cells and grown in LB media supplemented with 0.1 mm biotin (Sigma). Protein expression was induced with 0.5 mm IPTG at 20 °C overnight. All forms of Rac1-aldehyde tag and biotinylated Tiam1 proteins were purified as described above.

Guanine nucleotide exchange assays on aldehyde-tagged Rac1 and biotinylated Tiam1 fragments

We performed control experiments to assess the effect of tags (biotin and aldehyde) on Tiam1/Rac1 GEF exchange activity. Intrinsic nucleotide exchange activity of Rac1 was not affected by the aldehyde tag (supplemental Fig. S8A). Moreover, exchange activity assays using the PHn-PHc fragment showed no difference between Rac1 and aldehyde-tagged Rac1 (supplemental Fig. S8B). The biotin-tagged DH-PHc domain had a small decrease in the rate of exchange activity (4.0 × 10−4 s−1 compared with 5.8 × 10–4 s−1 unlabeled DH-PH domain; p value = 0.10) (supplemental Fig. S8C). Finally, GEF exchange assays for the DH-PHc domain showed that the addition of 50 mm arginine and glutamic acid had no effect on exchange activity (supplemental Fig. S8D). These experiments indicate that that the aldehyde-tagged Rac1 behaves identically to the untagged Rac1 and that the biotin has a small effect on nucleotide exchange activity of the DH-PHc domain but not the PHn-PHc fragment.

Rac1 labeling with Cy3 in vitro

Purified, aldehyde-tagged Rac1 protein was specifically and covalently labeled at the resulting formyl-glycine residue with Cy3-hydrazide (GE Healthcare) in vitro as described previously (72). Rac1-aldehyde tag was exchanged into labeling buffer that contained 250 mm potassium phosphate pH 7.0, 500 mm KCl, and 5 mm DTT using an Amicon Ultra-0.5 centrifugal filter (Millipore). Next, the Rac1 protein solution (30 μl at 15 μm concentration) was slowly mixed with 1 mg of dried Cy3-hydrazide (3 μl of protein with 0.1 mg Cy3-hydrazide) and incubated in the dark at 4 °C for 24 h. Free, unreacted dye was removed, and the buffer was exchanged using a PD SpinTrap G-25 (GE Healthcare) size-exclusion column run in storage buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 150 mm NaCl, and 1 mm DTT). The labeling efficiency (molar ratio of Rac1:Cy3) was quantified spectroscopically by determining the concentration of Rac1 at 280-nm wavelength (ϵ280 = 0.21 μm−1cm−1) and at 552-nm wavelength for Cy3 fluorophore (ϵ552 = 0.15 μm−1cm−1). Typically, the labeling efficiency was ∼80%. Cy3-labeled Rac1 was aliquoted, flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C.

Single-molecule TIRF microscopy imaging

TIRF imaging was performed using a prism-type TIRF microscope. The microscope was assembled on an Olympus IX-71 chassis (Olympus America). A diode-pumped solid-state laser with excitation wavelength of 532 nm (Coherent Inc.) was aligned along the optics table and passed through a Pellin-Broca prism (Eksma Optics) to generate an evanescent field for excitation of the Cy3 fluorophore. A water immersion 60× objective (Olympus America) was used to observe the fluorescence signal. The signal-to-noise ratio was enhanced through use of an emission filter to remove excitation light from the path to the IXON EMCCD (Andor Technology) camera, where fluorescence was recorded at 10 or 30 frames per second with amplification of 290× without image binning or averaging. A laser power of 45 milliwatts was used for all single-molecule experiments.

The microscope sample chamber was passivated using a 250:1 molar ratio polyethylene glycol (PEG) and biotinylated PEG (MPEG-SVA-5000 and Biotin-PEG-SVA-5000, Laysan Bio) followed by incubation with neutravidin (100 pm; Pierce) (73). N-terminally biotinylated Tiam1 DH-PHc or PHn-PHc proteins (150 pm) were immobilized onto the passivated glass surface in the sample chamber. The slide chamber was washed with reaction buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 150 mm NaCl, 5 mm MgCl2, 0.1 mg/ml BSA, 1 mm DTT, 0.8% glucose, and 50 μm GDP). Indicated concentrations of Cy3-labeled Rac1 were introduced to the slide chamber, and movies were recorded for 600 s at 100-ms intervals for the Tiam1 DH-PHc fragment and 424 s at 33-ms intervals for the Tiam1 PHn-PHc fragment. Initially, the 33-ms interval was used in anticipation of very weak binding and short events. Subsequent analysis showed that the 100-ms interval was adequate. Experiments were performed at 1, 3, and 5 nm concentrations of fluorescently labeled Rac1 for the DH-PHc and 0.5, 1, 3, and 5 nm concentrations of fluorescently labeled Rac1 for the PHn-PHc construct in the reaction buffer supplemented with a Trolox-based oxygen scavenging system. The Trolox system contained 0.04 mg/ml catalase and 1 mg/ml glucose oxidase (70, 74). The 12 mm Trolox (6-hydroxy-2,5,7,8-tetramethylchromane-2-carboxylic acid, Sigma) solution was prepared as previously described (70, 74).

Analysis of single-molecule TIRF imaging data

Analysis of the single-molecule data were carried out as outlined previously (75). Briefly, single-molecule trajectories were extracted using IDL software and selected for analysis based upon the presence of stable fluorescent signal intensity over time (76, 77). QuB software was used to generate idealized Cy3 trajectories and identify bound and free (unbound) states (78, 79). To ensure analysis of binding did not include diffusion events of labeled protein, bound states that lasted fewer than three frames were excluded from the analysis. Events were extracted from QuB and sorted into bound and unbound events (79). Bound events were binned, plotted as frequency histograms, and globally fit using all concentrations to single or double exponential functions to determine the koff rate constant (GraphPad Prism 7.0). Statistical analyses (F-test) determined that a double exponential fit was more appropriate for fitting the DH-PHc and PHn-PHc datasets. Filtering and re-binning the 33 ms data to a 99-ms interval gave a distribution whose fitted kinetic parameters were identical within error to those of the original 33-ms framed data.

Author contributions

Z. X. and E. J. F. conceived the project. Z. X. and L. G. designed, performed, and analyzed the SAXS experiments. F. E. B. and M. S. performed and analyzed the single-molecule fluorescence experiments. Z. X. designed, performed, and analyzed all the other experiments. Z. X. and E. J. F. wrote the paper and prepared the figures. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank members in the Fuentes laboratory for discussions and technical assistance. We thank the staff at the University of Iowa Protein Crystallography Core, BioCAT beamline 18-ID-D at the Argonne National Laboratory and the SIBYLS beamline 12.3.1 at the Berkeley National Laboratory for assistance with SAXS data collection. We thank Dr. Casey Andrews and Shuxiang Li for assistance in the construction of atomic models. We thank Dr. Elizabeth Boehm and Dr. Todd Washington for preliminary single-molecule experiments. We acknowledge that this research used the resources of the Advanced Light Source, which is a DOE Office of Science User Facility under Contract DE-AC02-05CH11231. In addition, this research used the resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a United States Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract DE-AC02-06CH11357.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant R01 GM108617 (to M. S.). This work was also supported by National Science Foundation Grant MCB-0953080 and by the American Heart Association (0835261N) (to E. J. F.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

This article contains supplemental Tables S1–S3 and Figs. S1–S9.

Please note that the JBC is not responsible for the long-term archiving and maintenance of this site or any other third party hosted site.

- GEF

- guanine nucleotide exchange factor

- DH

- Dbl homology

- PH

- Pleckstrin homology

- MANT-GDP

- 2′(3′)-O-(N-methylanthraniloyl) guanosine diphosphate

- TIRF

- total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy

- IPTG

- isopropyl 1-thio-d-glactopyranoside

- SEC

- size-exclusion chromatography

- SAXS

- small angle X-ray scattering

- DLS

- dynamic light scattering

- FGE

- formylglycine-generating enzyme

- CC-Ex

- coiled-coil extension

- RBD

- Ras-binding domain

- N50

- N-terminal 50 amino acid residues

- Rh

- hydrodynamic radius

- Pd

- polydispersity

- APS

- Advanced Photon Source

- ALS

- Advanced Light Source

- Rg

- radius of gyration

- rTEV

- recombinant tobacco etch virus

- PDZ

- PSD-95/DlgA/ZO-1 domain.

References

- 1. Hodge R. G., and Ridley A. J. (2016) Regulating Rho GTPases and their regulators. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 17, 496–510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chen X., and Macara I. G. (2005) Par-3 controls tight junction assembly through the Rac exchange factor Tiam1. Nat. Cell Biol. 7, 262–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jaffe A. B., and Hall A. (2005) Rho GTPases: biochemistry and biology. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 21, 247–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mertens A. E., Rygiel T. P., Olivo C., van der Kammen R., and Collard J. G. (2005) The Rac activator Tiam1 controls tight junction biogenesis in keratinocytes through binding to and activation of the Par polarity complex. J. Cell Biol. 170, 1029–1037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nishimura T., Yamaguchi T., Kato K., Yoshizawa M., Nabeshima Y., Ohno S., Hoshino M., and Kaibuchi K. (2005) PAR-6-PAR-3 mediates Cdc42-induced Rac activation through the Rac GEFs STEF/Tiam1. Nat. Cell Biol. 7, 270–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bid H. K., Roberts R. D., Manchanda P. K., and Houghton P. J. (2013) RAC1: an emerging therapeutic option for targeting cancer angiogenesis and metastasis. Mol. Cancer Ther. 12, 1925–1934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bos J. L., Rehmann H., and Wittinghofer A. (2007) GEFs and GAPs: critical elements in the control of small G proteins. Cell 129, 865–877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cook D. R., Rossman K. L., and Der C. J. (2014) Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factors: regulators of Rho GTPase activity in development and disease. Oncogene 33, 4021–4035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Erickson J. W., and Cerione R. A. (2004) Structural elements, mechanism, and evolutionary convergence of Rho protein-guanine nucleotide exchange factor complexes. Biochemistry 43, 837–842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mertens A. E., Roovers R. C., and Collard J. G. (2003) Regulation of Tiam1-Rac signalling. FEBS Lett. 546, 11–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Boissier P., and Huynh-Do U. (2014) The guanine nucleotide exchange factor Tiam1: a Janus-faced molecule in cellular signaling. Cell. Signal. 26, 483–491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Malliri A., van der Kammen R. A., Clark K., van der Valk M., Michiels F., and Collard J. G. (2002) Mice deficient in the Rac activator Tiam1 are resistant to Ras-induced skin tumours. Nature 417, 867–871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Stebel A., Brachetti C., Kunkel M., Schmidt M., and Fritz G. (2009) Progression of breast tumors is accompanied by a decrease in expression of the Rho guanine exchange factor Tiam1. Oncol. Rep. 21, 217–222 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Buongiorno P., Pethe V. V., Charames G. S., Esufali S., and Bapat B. (2008) Rac1 GTPase and the Rac1 exchange factor Tiam1 associate with Wnt-responsive promoters to enhance β-catenin/TCF-dependent transcription in colorectal cancer cells. Mol. Cancer 7, 73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Minard M. E., Ellis L. M., and Gallick G. E. (2006) Tiam1 regulates cell adhesion, migration and apoptosis in colon tumor cells. Clin. Exp. Metastasis 23, 301–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Engers R., Mueller M., Walter A., Collard J. G., Willers R., and Gabbert H. E. (2006) Prognostic relevance of Tiam1 protein expression in prostate carcinomas. Br. J. Cancer 95, 1081–1086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Adam L., Vadlamudi R. K., McCrea P., and Kumar R. (2001) Tiam1 overexpression potentiates heregulin-induced lymphoid enhancer factor-1/β-catenin nuclear signaling in breast cancer cells by modulating the intercellular stability. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 28443–28450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rossman K. L., Der C. J., and Sondek J. (2005) GEF means go: turning on RHO GTPases with guanine nucleotide-exchange factors. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6, 167–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Baumeister M. A., Martinu L., Rossman K. L., Sondek J., Lemmon M. A., and Chou M. M. (2003) Loss of phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate binding by the C-terminal Tiam-1 pleckstrin homology domain prevents in vivo Rac1 activation without affecting membrane targeting. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 11457–11464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Viaud J., Lagarrigue F., Ramel D., Allart S., Chicanne G., Ceccato L., Courilleau D., Xuereb J. M., Pertz O., Payrastre B., and Gaits-Iacovoni F. (2014) Phosphatidylinositol 5-phosphate regulates invasion through binding and activation of Tiam1. Nat. Commun. 5, 4080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Terawaki S., Kitano K., Mori T., Zhai Y., Higuchi Y., Itoh N., Watanabe T., Kaibuchi K., and Hakoshima T. (2010) The PHCCEx domain of Tiam1/2 is a novel protein- and membrane-binding module. EMBO J. 29, 236–250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Joshi M., Gakhar L., and Fuentes E. J. (2013) High-resolution structure of the Tiam1 PHn-CC-Ex domain. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. F. Struct. Biol. Cryst Commun. 69, 744–752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tanaka M., Ohashi R., Nakamura R., Shinmura K., Kamo T., Sakai R., and Sugimura H. (2004) Tiam1 mediates neurite outgrowth induced by ephrin-B1 and EphA2. EMBO J. 23, 1075–1088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Buchsbaum R. J., Connolly B. A., and Feig L. A. (2002) Interaction of Rac exchange factors Tiam1 and Ras-GRF1 with a scaffold for the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 4073–4085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yamauchi J., Miyamoto Y., Tanoue A., Shooter E. M., and Chan J. R. (2005) Ras activation of a Rac1 exchange factor, Tiam1, mediates neurotrophin-3-induced Schwann cell migration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 14889–14894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lambert J. M., Lambert Q. T., Reuther G. W., Malliri A., Siderovski D. P., Sondek J., Collard J. G., and Der C. J. (2002) Tiam1 mediates Ras activation of Rac by a PI(3)K-independent mechanism. Nat. Cell Biol. 4, 621–625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Miyamoto Y., Yamauchi J., Tanoue A., Wu C., and Mobley W. C. (2006) TrkB binds and tyrosine-phosphorylates Tiam1, leading to activation of Rac1 and induction of changes in cellular morphology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 10444–10449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fleming I. N., Elliott C. M., Buchanan F. G., Downes C. P., and Exton J. H. (1999) Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II regulates Tiam1 by reversible protein phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 12753–12758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Fleming I. N., Elliott C. M., Collard J. G., and Exton J. H. (1997) Lysophosphatidic acid induces threonine phosphorylation of Tiam1 in Swiss 3T3 fibroblasts via activation of protein kinase C. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 33105–33110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Woodcock S. A., Jones R. C., Edmondson R. D., and Malliri A. (2009) A modified tandem affinity purification technique identifies that 14-3-3 proteins interact with Tiam1, an interaction which controls Tiam1 stability. J. Proteome Res. 8, 5629–5641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Woodcock S. A., Rooney C., Liontos M., Connolly Y., Zoumpourlis V., Whetton A. D., Gorgoulis V. G., and Malliri A. (2009) SRC-induced disassembly of adherens junctions requires localized phosphorylation and degradation of the rac activator tiam1. Mol. Cell 33, 639–653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Michiels F., Stam J. C., Hordijk P. L., van der Kammen R. A., Ruuls-Van Stalle L., Feltkamp C. A., and Collard J. G. (1997) Regulated membrane localization of Tiam1, mediated by the NH2-terminal pleckstrin homology domain, is required for Rac-dependent membrane ruffling and C-Jun NH2-terminal kinase activation. J. Cell Biol. 137, 387–398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Matsuzawa K., Akita H., Watanabe T., Kakeno M., Matsui T., Wang S., and Kaibuchi K. (2016) PAR3-aPKC regulates Tiam1 by modulating suppressive internal interactions. Mol. Biol. Cell 27, 1511–1523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Shepherd T. R., Klaus S. M., Liu X., Ramaswamy S., DeMali K. A., and Fuentes E. J. (2010) The Tiam1 PDZ domain couples to Syndecan1 and promotes cell-matrix adhesion. J. Mol. Biol. 398, 730–746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Worthylake D. K., Rossman K. L., and Sondek J. (2000) Crystal structure of Rac1 in complex with the guanine nucleotide exchange region of Tiam1. Nature 408, 682–688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Randazzo P. A., Jian X., Chen P. W., Zhai P., Soubias O., and Northup J. K. (2013) Quantitative analysis of guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) as enzymes. Cell. Logist. 3, e27609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Heo J., Thapar R., and Campbell S. L. (2005) Recognition and activation of Rho GTPases by Vav1 and Vav2 guanine nucleotide exchange factors. Biochemistry 44, 6573–6585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Svergun D. I. (1992) Determination of the regularization parameter in indirect-transform methods using perceptual criteria. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 25, 495–503 [Google Scholar]

- 39. Durand E., Waksman G., and Receveur-Brechot V. (2011) Structural insights into the membrane-extracted dimeric form of the ATPase TraB from the Escherichia coli pKM101 conjugation system. BMC Struct. Biol. 11, 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Svergun D. I. (1999) Restoring low resolution structure of biological macromolecules from solution scattering using simulated annealing. Biophys. J. 76, 2879–2886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Volkov V. V., and Svergun D. I. (2003) Uniqueness of ab initio shape determination in small-angle scattering. J. Appl Crystallogr. 36, 860–864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Petoukhov M. V., Franke D., Shkumatov A. V., Tria G., Kikhney A. G., Gajda M., Gorba C., Mertens H. D., Konarev P. V., and Svergun D. I. (2012) New developments in the ATSAS program package for small-angle scattering data analysis. J. Appl Crystallogr. 45, 342–350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Pelikan M., Hura G. L., and Hammel M. (2009) Structure and flexibility within proteins as identified through small angle X-ray scattering. Gen. Physiol. Biophys. 28, 174–189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Tria G., Mertens H. D., Kachala M., and Svergun D. I. (2015) Advanced ensemble modelling of flexible macromolecules using X-ray solution scattering. IUCrJ 2, 207–217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Cherfils J., and Zeghouf M. (2013) Regulation of small GTPases by GEFs, GAPs, and GDIs. Physiol. Rev. 93, 269–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Barreira M., Fabbiano S., Couceiro J. R., Torreira E., Martínez-Torrecuadrada J. L., Montoya G., Llorca O., and Bustelo X. R. (2014) The C-terminal SH3 domain contributes to the intramolecular inhibition of Vav family proteins. Sci. Signal. 7, ra35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Bustelo X. R. (2014) Vav family exchange factors: an integrated regulatory and functional view. Small GTPases 5, 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Aghazadeh B., Lowry W. E., Huang X. Y., and Rosen M. K. (2000) Structural basis for relief of autoinhibition of the Dbl homology domain of proto-oncogene Vav by tyrosine phosphorylation. Cell 102, 625–633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]