Abstract

The uneven representation of frugivorous mammals and birds across tropical regions – high in the New World, low in Madagascar and intermediate in Africa and Asia – represents a long-standing enigma in ecology. Several hypotheses have been proposed to explain these differences but the ultimate drivers remain unclear. Here, we tested the hypothesis that fruits in Madagascar contain insufficient nitrogen to meet primate metabolic requirements, thus constraining the evolution of frugivory. We performed a global analysis of nitrogen in fruits consumed by primates, as collated from 79 studies. Our results showed that average frugivory among lemur communities was lower compared to New World and Asian-African primate communities. Fruits in Madagascar contain lower average nitrogen than those in the New World and Old World. Nitrogen content in the overall diets of primate species did not differ significantly between major taxonomic radiations. There is no relationship between fruit protein and the degree of frugivory among primates either globally or within regions, with the exception of Madagascar. This suggests that low protein availability in fruits influences current lemur communities to select for protein from other sources, whereas in the New World and Old World other factors are more significant in shaping primate communities.

Introduction

The evolution of plant-frugivore interactions is considered to have contributed to the high diversity of tropical mammals and birds1,2. This diversity is the consequence of a long evolutionary history where the radiation of angiosperms triggered the emergence of frugivorous vertebrates2, which in turn are essential for the dispersal of most tropical plant species3,4. Among vertebrates, however, strict frugivory is rare since fruits are distributed patchily in space and time5 and, although easy to digest, are assumed to contain too little proteins to meet species’ metabolic requirements6,7. Nitrogen, the fundamental component of proteins, has been suggested as a limiting factor for the survival of vertebrate communities in general8–10. Thus, most frugivorous mammals and birds supplement their diets with protein-rich foods, such as leaves or invertebrates, to satisfy their nitrogen needs3,11.

Due to the key role of proteins, primate feeding guilds, within which frugivory is widely represented, are hypothesized to have evolved under the constraints of nitrogen availability12. For example, among folivorous primates the ratio between protein and fiber has been found to be a powerful predictor of food choice and population densities13–19, but see20,21. While some primates appear to maximize protein intake22,23, others apparently do not24,25. At least for folivorous species, the strength of this selection depends on the protein availability within the environment26. Maintaining a balanced protein intake is particularly challenging for frugivorous primates, since they lack physiological adaptations to optimize nitrogen extraction from food and thus must increase their total food intake in order to meet their requirements7,27. Recent investigations based on fine-grained analyses of nutrient intake suggest that although protein maximization does not explain spider monkey (Ateles chamek) feeding choices, this frugivorous species maintains a relatively constant protein intake regardless of season, sex, or available food10.

Frugivory seems to have evolved independently numerous times in primates28. The New World has a greater number of frugivorous families and species compared with the Old World radiations of Africa and Asia, while Madagascar appears to have a paucity of taxa in this dietary guild29,30. Recent data indicate that when food intake, rather than feeding time, is used to quantify diet, even the most folivorous of New World primates include a considerable proportion of fruits in their diet31. Unlike the New World, many Malagasy primates are folivorous and only two genera, Varecia and Eulemur, are considered mainly frugivorous32–34. This contrasting representation of frugivores in the New World and Madagascar is mirrored in other groups of mammals and birds2,35, and is considered a long-standing enigma in ecology36,37. There are 117 and 24 genera of fruit-eating birds and bats, respectively, in the New World, whereas there are merely five and three, respectively, in Madagascar1. Three non-mutually exclusive hypotheses have been put forward to explain the observed asymmetry between communities in dietary guild representation.

According to the food availability hypothesis, there should be a significant difference in the costs of frugivory due to temporal patterns of resource availability on different continents. In the New World, the high degree of overlap between periods of young leaf scarcity and low fruit availability would make it difficult for a frugivore to shift to a leafy diet during fruit shortages, thus making year-round frugivory obligatory. Here, during times of food scarcity, irregularly fruiting figs (Ficus spp.) act as keystone species that could allow frugivorous species to survive the lean period5,38,39. Conversely, extended lean periods, low predictability of fruiting, and the high frequency of cyclones have been hypothesized as driving forces that makes year-round frugivory challenging in Madagascar40. It has also been suggested that the contrasting abundance of certain keystone plants, such as figs, between continents contributes to the observed frugivore asymmetry5,35,36. The food availability hypothesis has been challenged by contradictory evidence of comparative studies and long-term phenological datasets in the New World41,42, while it stands as one of the major frameworks explaining lemur community structure in Madagascar40,43.

The historical hypothesis proposes that the lack of folivorous primates in the New World results from the inability of Platyrrhini (i.e., New World primates) ancestors to exploit the folivorous niche already occupied by other mammalian taxa, such as sloths44,45. On the contrary, that lemurs occupy a tremendous diversity of niches would have been possible due to the poor representation of other mammalian competitors in Madagascar. This idea, based on the rationale that primates arrived late in the New World and early in Madagascar relative to other mammals44–46, would be supported by evidence of niche compression in the most diverse New World primate communities45.

According to the nutritional hypothesis, if fruits contain enough nitrogen to meet primate protein requirements during gestation, lactation and weaning, there should be minimal selection to evolve a non-fruit diet and associated metabolic adaptations47. This would be particularly relevant for extant Neotropical and Malagasy primates that tend to be smaller in size relative to other primate radiations and thus should rely more heavily on food quality during key reproductive stages, i.e. income breeders48–52. This hypothesis is supported by a recent work that described higher fruit nitrogen content in the New World compared to Madagascar47. However, this study i) did not include samples from other continental areas occupied by primates; ii) relied on limited sample size and locations; and iii) did not control for factors such as spatial autocorrelation and sampling effort.

Here, we tested the robustness of the nutritional hypothesis by adding African and Asian sites to the comparison and by correcting previous shortcomings through the use of models accounting for different sampling efforts and non-independence of data. For this, we used a data-set of published and unpublished data on nitrogen content in fruits consumed by primates, as collated from 79 studies at 62 sites distributed across the New World, the Old World (Africa and Asia), and Madagascar. We first tested the expectation that primate communities in Africa and Asia are intermediate in terms of frugivorous guild representation between the New World (highest proportion) and Madagascar (lowest proportion). We used the proportion of frugivorous primate species and the average frugivory at a given site as measures of frugivory. In line with the nutritional hypothesis, we then tested the prediction that fruit nitrogen content will show the highest values at New World sites and the lowest values in Madagascar, while Old World sites will be intermediary. Since the nutritional hypothesis only makes sense if the consumers within different primate radiations have similar protein requirements, we also tested whether or not the overall diet (including all plant items) of species included in the analysis (representing all primate radiations) contained similar concentrations of proteins. Finally, we modelled fruit nitrogen to test whether it can explain geographical patterns of primate frugivory globally and within regions.

Results

Geographical pattern of primate frugivory

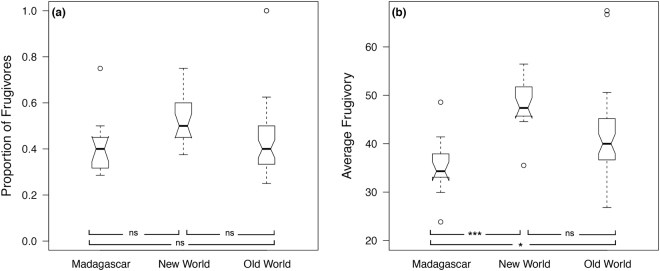

As expected, the degree of primate frugivory was higher in the New World and the Old World, and lower in Madagascar. The proportion of frugivorous species per site (i.e., proportion of species with more than 50% fruits in their diet) is lower in Madagascar but not significantly different from the New World (GLSsp estimate ± SE: 0.07 ± 0.07, p = 0.37; ΔAIC of the null model = 3.15) or the Old World (0.05 ± 0.07, p = 0.48; Fig. 1). The average degree of frugivory (i.e., average proportion of fruits in diet), on the other hand, is significantly higher in the New World (12.04 ± 3.23, p < 0.001; ΔAIC of the null model = 9.69) and in the Old World (6.71 ± 2.97, p = 0.026) compared to Madagascar.

Figure 1.

Notched boxplot representing the comparison in the proportion of frugivorous primates (a) and the average frugivory in primate diets (b) at 62 sites in Madagascar, New World, and Old World (raw data; without correction for autocorrelations). While the boxes encompass the interquartile range, the notches represent the 95% confidence interval of the median (central line). Proportion of frugivorous primates is represented as proportion of primate species with more than 50% fruits in their diet. *p < 0.05; ***p < 0.001; ns = non significant.

Geographical pattern of fruit nitrogen and average nitrogen in primate diets

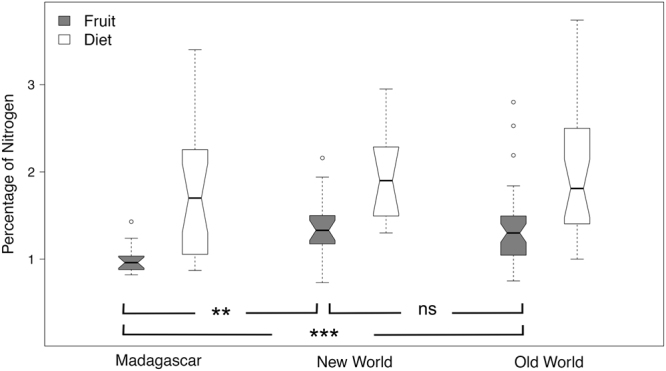

Similar to the pattern of frugivory, fruit nitrogen content was higher in the New World and Old World, and lower in Madagascar. Our model estimated fruit nitrogen content to be higher at sites in the New World (GLSsp estimate ± SE = 1.28% ± 0.10%), followed by the Old World (1.25% ± 0.08%) and Madagascar (0.98% ± 0.06%) (ΔAIC of the null model = 9.68; Fig. 2, Supplementary Table S1). Fruit nitrogen content in both the New World and the Old World was significantly higher than in Madagascar (Tukey post-hoc test: New World – Madagascar = 0.30 ± 0.10, p = 0.006; Old World – Madagascar = 0.28 ± 0.08, p = 0.001), whereas there was no significant difference between the two continental areas (New World – Old World = −0.03 ± 0.09, p = 0.95). These results were consistent with those obtained using the GLS not controlled for spatial autocorrelation (GLSnsp) (Supplementary Tables S2 and S3).

Figure 2.

Notched boxplot representing the comparison in the nitrogen concentration in fruits and primate diet in Madagascar, New World, and Old World (raw data). While the boxes encompass the interquartile range, the notches represent the 95% confidence interval of the median (central line). Nitrogen is represented as percentage of dry matter. **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ns = non significant.

Conversely, nitrogen content in the overall diet of the primate species included in our analysis did not differ between New World, Old World, and Madagascar (Fig. 2, Supplementary Table S4). The Generalized Least Square model had a lower AIC than the corresponding null models that assumed no difference between the three areas (ΔAIC = 0.34). However, the model was not supported due to the higher number of parameters while standing within 2 units of AIC from the null model. Nitrogen content was estimated to be highest in the diet of New World primates (GLS estimate ± SE = 2.17% ± 0.22%), followed by lemurs (1.78% ± 0.12%) and Old World primates (1.75% ± 0.18%). These estimates were not significantly different between the three groups (Tukey post-hoc test: Old World - New World primates = −0.42 ± 0.24, p = 0.18; Old World primates - lemurs = −0.03 ± 0.18, p = 0.98; New World primates - lemurs = 0.39 ± 0.22, p = 0.20).

Despite the above differences, globally the proportion of frugivorous primate species and the average frugivory were uncorrelated with the protein concentrations in fruits at a given site (Supplementary Table S5). In both cases, the best model includes an interaction term between the three regions and the nitrogen content in fruits. However, considering the relationship separately for the three regions, fruit nitrogen is significantly positively related to the proportion of frugivores (GLSsp estimate ± SE: 0.06 × 10−1 ± 0.05 × 10−1, p < 0.001) and average frugivory (0.23 ± 0.02, p < 0.001) in Madagascar, but shows no relationship in the New World (−0.06 × 10−1 ± 0.01 for the proportion of frugivores and −0.27 ± 0.49 for average frugivory), or in the Old World (−0.06 × 10−1 ± 0.05 × 10−2 for the proportion of frugivores and −0.23 ± 0.02 for average frugivory).

Discussion

Our study supports the prediction of the nutritional hypothesis in explaining the lower proportion of frugivorous species in Madagascar primate communities compared with those on other continents47. The average frugivory of lemur communities was lower compared to New World and Asian-African (combined as Old World) primate communities. This contrasting representation of average frugivory is mirrored by the data on fruit proteins, since fruits at Malagasy sites showed lower average nitrogen content than those at Old World and New World sites. The variation between continents follows a similar pattern when the proportion of primate species that include more than 50% of fruits in their diet is used to estimate frugivory, although these differences do not reach statistical significance. However, contrary to the expectation, the degree of frugivory of the New World primate communities did not differ from Asian/African sites despite the highest representation of frugivorous primates revealed by other studies in the Neotropics29,30. This contrasts with recent analyses on birds indicating that present-day climate and forest productivity correlate with high proportion of frugivorous species in the Neotropics37. In birds, the high diversity of fleshy fruit plant species in both lowland and mountain regions in the Neotropics has been used to explain the high proportion of frugivorous species in habitats of both equatorial latitude regions of South America53. Since primate seed dispersal often co-occurs in plant families exhibiting bird dispersal2, we would expect that similar ecological factors may have also played a role for primates. The observation that this was not the case for our study sites suggests that different ecological constraints operate on primates and contributed to the observed pattern5,36,44. Sampling biases may have also been responsible for the lack of substantial differences in degree of frugivory between primates in the New World and Old World, both in terms of community composition and fruit protein content. For example, some of our New World study sites contain primate communities that are peripheral to the Amazon basin and only include a few species.

The overall lack of correlation between the degree of primate frugivory and fruit nitrogen concentrations indicates that evolutionary processes and contemporary ecological patterns are governed by multiple forces. The local representation of frugivorous species is likely to be profoundly influenced by factors such as population densities, species body mass, social systems and the number of species in a community. These factors might impose different constraints on the proportion of frugivorous primates than the radiation of species numbers over evolutionary time scales. However, the strong positive correlation between fruit protein and degree of frugivory for Madagascar but not for the other continents points to low fruit protein concentrations as a specific constraint on the island that has not become effective in other parts of the world. This echoes recent findings which indicate that folivorous primates select for high protein leaves only in forests where the average protein content in leaves is low26. Similarly, populations of arboreal marsupials do not appear to persist in areas where nutrient/toxin ratios fall below a threshold, while areas above that threshold appear constrained by a range of other factors that seem to play a role in the regulation of populations54.

According to the nutritional hypothesis, the average percentage of fruit nitrogen content in Madagascar (0.96%) is below the minimum nitrogen requirements threshold for primates (1.1%)55. This may have increased the selective pressures to evolve non-frugivorous diets and associated adaptations in lemurs47. The nutritional hypothesis is further corroborated by our control analysis that revealed similar nitrogen content in the overall diet of platyrrhines, catarrhines, and lemuriformes, which indicated compensation from other food categories when fruit nitrogen is scarce.

The main consequence of having to rely on food with relatively low nitrogen is that nutritional intake is limited by the ability to process enough food material, rather than by the scarcity of the nutrient itself56,57. In Madagascar, fruit consumption may also be limited by the availability of fruit trees that seem to be much smaller compared to those in other parts of the world, combined with more erratic fruiting patterns40,43,58. Under these conditions, animals may either shift to more proteinaceous food, such as leaves and/or invertebrates, or increase the amount of food processed. In fact, over-ingestion to meet protein requirements has been observed in frugivorous birds59 and some primates10 but see60, and a loss of body mass may even occur when protein intake is low despite an energy-rich diet6. In line with the nutritional hypothesis, the most frugivorous lemur genera, Varecia and Eulemur (family Lemuridae), are characterized by an “intake” strategy with some of the fastest food passage rates relative to body size recorded in primates61,62. Also, most lemurids are cathemeral, i.e. active over the 24 hours, an adaptation that may have helped to further increase both the amount of food processed and the nitrogen intake in animals lacking a specialized digestive system63.

It is important to note that the lack of global correlation with available nitrogen and other existing ecological processes may be a consequence of historical factors that could have amplified or hidden those effects. These include the evolutionary history of the fruiting trees, the presence or absence of other vertebrate competitors, the paleo-climate, the presence of dispersal barriers, or even human-induced extinctions1,64,65. For example, the high proportion of fruit-eating primates in the New World might be the result of the post-Pleistocene megafauna extinctions caused by the arrival of humans in Central and South America66. This idea appears to be supported by the reported extirpation of a large woolly monkey, Brachyteles sp., and the recent discovery of a subfossil giant platyrrhine67,68. This might explain the upper truncation in the body mass-diet relationship in New World primates. The hypothesis, however, is bound by the meager fossil record of extinct folivorous primates in the Americas as compared to other continents69. Historical events may have also played a major role in determining the current low diversity of frugivorous lemurs in Madagascar. A recent analysis shows that stem lineages leading to the Indri and Avahi clades (currently both fully folivorous) probably had a frugivorous diet, suggesting that frugivory was previously present in a more diverse array of lemur taxa compared to today70.

As a note of caution, however, we acknowledge that this idea remains exploratory until more data are collected on actual nutrient availability and intake among primates71. Despite the global scale of this analysis and the increased number of field sites over the last decade where primates are studied, sampling efforts on primate food are both taxonomically and geographically biased with efforts concentrated at relatively few sites and specific regions72. Another problem is in the difficulty of sampling the full breadth of the primate diet even for those species that have been longitudinally studied. This is particularly true for areas where fruiting plant patterns show multi-annual cycles and/or where plant diversity is relatively high4,58,73.

In summary, our results provide support to the hypothesis that lower availability of fruit proteins in Madagascar may not have provided an adequate protein intake to allow the evolution of frugivory among the radiations of the island’s endemic primates. Low protein availability in fruits may have also caused a more compelling relationship between the degree of frugivory in current lemur communities and fruit proteins available in their habitats, while other primate radiations appear less constrained by fruit proteins. As food characteristics influence the evolution of traits beyond dietary adaptations74, the deviating nutritional characteristics revealed by our analysis might complement the factors already identified40,43 as having broad implications for the evolution of life history traits of Madagascar’s biota.

Materials and Methods

Data-set

We used published and unpublished data (Supplementary Table S1) to compile mean fruit nitrogen concentrations from 79 studies at 62 forest sites across three continental areas: Madagascar (15 studies), Old World (44 studies), and New World (20 studies) (Fig. 3). Primates comprise several large radiations: the Tarsiiformes (tarsiers) branched off at ~81 Mya, the split between the Catarrhini (Old World monkeys and apes) and the Platyrrhini (New World monkeys) dates back to ~43 Mya, and that between the Lemuriformes (Malagasy lemurs) and Lorisiformes (lorises, galagos, and pottos) has been estimated at ~69 Mya75. Tarsiers and some lorises are almost completely faunivorous. Fruit-eating amongst the remaining Lorisiformes is rare, with the exception of a handful of taxa76. As such, these two radiations of small-bodied primates are excluded from the analysis. We used a broad-scale of biogeographic regions to compare primate radiations at the taxonomic infraorder level. Thus, we combined Asian and African sites as Old World sites to represent the Catarrhini, while sites in Madagascar and in the New World represent the Lemuriformes and Platyrrhini radiations, respectively.

Figure 3.

Map representing the 62 locations for which nitrogen records were available. Point size is proportional to the average nitrogen concentration in fruits per site. Studies are listed in Supplementary Table S1. The figure was created using “maptools” package in R v 3.3.2 (https://cran.r-project.org/).

Given that no primates to our knowledge live in the dry savannas or spiny forests of the Americas, studies conducted in non-forest habitats or sites with more than nine consecutive dry months (defined as months with <100 mm rainfall) in the Old World and Madagascar were excluded from the analysis. This helps to keep the abiotic conditions more comparable amongst the three regions. We used nitrogen concentrations rather than crude protein in our comparison because different conversion factors from nitrogen to crude protein have been suggested77. Only studies reporting total nitrogen measured with the Kjeldahl method were used in the analysis78.

We considered the nitrogen concentration in fruits consumed by primates as representative samples of the nitrogen concentrations for all fruits available at each site. Our assumption is based on the observation that in most studies addressing protein selection in fruits, there were no reported significant differences between fruits eaten and not eaten by primates47,79,80. Thus, to compile fruit data at a given site we used both general sampling of all fruits (both ripe and unripe) and/or fruits eaten by primates.

Analyses

Geographical pattern of primate frugivory

To test the expectation that primate frugivory is higher in the Neotropics than in the Old World and Madagascar, we first compared frugivory between the three regions expressed both as the proportion of frugivores (>50% of fruit in the diet) and as average frugivory (average proportion of fruits in the diet) at the 62 sites present in our data-set. The diets of all primate species at the 62 sites were determined from a comprehensive literature survey using the All The World Primates’ database81. We followed previous authors who define frugivore as an animal whose diet is composed of more than 50% fruits1. We used the average when more than one study was available at a given site for a species. When no information was available about a species at a given site, we used species information from a different study site. Because study sites are unevenly distributed and the similarity in frugivory between two sites can reflect their geographical distance, we controlled for spatial autocorrelation in the models. We first ran a null model (only-intercept models) with the proportion of frugivores and average frugivory as dependent variables, and tested the spatial autocorrelation in the residuals using Moran’s autocorrelation coefficient (often denoted as Moran I). Moran I is an extension of Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient to a univariate series82. Since Moran I was significant in both cases (proportion of frugivores: Moran I = 0.07; Expected value = −0.01; p = 0.046; average frugivory: Moran I = 0.34; Expected value = −0.01; p < 0.001), we ran Generalized Least Square Models (GLS) controlled for spatial autocorrelation (GLSsp)83. We tested the gaussian (corGaus), the exponential (corExp) and the spheric (corSpher) correlation structure, and selected the former as the one giving the lowest Akaike Information Criterion (AIC proportion of frugivores: Gauss = −164.08; Exp = −136.25; Spher = −136.57; AIC average frugivory: Gauss = 442.22; Exp = 461.37; Spher = 461.76). To assess whether the model complexity was justified by an increase in goodness of fit, we compared the two GLSsp with their corresponding null models using AIC. Models were considered supported when ΔAIC < 2 (ΔAIC = difference in AIC from the best model). Following Pinheiro & Bates84 all GLSs that were compared through AIC were fitted using Maximum Likelihood (ML), whereas the final GLSs were fitted using the Restricted Maximum Likelihood (REML).

Geographical pattern of fruit nitrogen and average nitrogen in primate diets

We compared the mean nitrogen content in fruits between the three regions using individual studies as our unit of analysis. Since large variations in the nutritional content of fruits have been reported by different studies even within the same site85, we considered the mean of each study as a separate datum. However, because this choice may lead to pseudo-replication, as well as spatial autocorrelation, we controlled for their spatial non-independence. As above, we tested the spatial autocorrelation in the residuals using Moran’s autocorrelation coefficient. Since Moran I was almost significant (Moran I = 0.06; Expected value = −0.01; p = 0.057), we ran two Generalized Least Square Models (GLS), one non-controlled for spatial autocorrelation (GLSnsp) and one controlled for spatial autocorrelation (GLSsp)83. For the latter, we tested the gaussian (corGaus), the exponential (corExp) and the spheric (corSpher) correlation structure, and selected the latter as the one giving the lowest Akaike Information Criterion (AIC: Gauss = 61.06; Exp = 60.69; Spher = 59.02). In order to control for the unequal sampling effort at different locations (sample size over which nitrogen was averaged), we weighted the two GLS models by the sample size per site. Because weights expressed as sample size may over-emphasize the importance of certain records, weights were transformed using a parameter Omega86. Omega is an elevation factor that ranges between 1 (the original sample sizes are used as weights) and 1/100 (all records are weighted equally). To estimate the Omega parameter, the GLS were repeatedly fitted using increasing values of Omegas, and used AIC to identify the best fitting model. The Omega corresponding to the lowest AIC was equal to 0.64 in GLSsp and 0.67 in GLSnsp. To assess whether model complexity was justified by an increase in goodness-of-fit, we compared the final GLSnsp and GLSsp with corresponding null models using AIC.

To test whether consumers of different primate radiations have similar protein requirements, we compared the overall dietary nitrogen between the three regions using primate species as the unit of analysis. Because the residuals of statistical models using species as units of analysis can be phylogenetically autocorrelated, we first fitted an ANOVA model and tested its residuals for phylogenetic autocorrelation using Pagel’s lambda87. We used the consensus phylogenetic tree from the 10kTrees phylogenies project based on the taxonomy of Wilson and Reeder88 (version 3; http://10ktrees.nunnlab.org/Primates/downloadTrees.php). Pagel’s lambda was 6.63 × 10−5 and not significantly different from zero (i.e. no autocorrelation), therefore there was no need to correct the model by accounting for phylogenetic autocorrelation. Similar to the previous model, we ran the ANOVA as a GLS weighted by the sample size and selected the Omega by using AIC and ML, and estimated the coefficients using the REML. For this model, Omega was equal to zero (i.e. all studies were weighted equally). The final GLS was compared with a corresponding null model using AIC.

In the models described above, we tested all comparisons between the three regions using the Tukey post-hoc test. All analyses were performed in R 3.3.089 using “nlme” package90 for running the GLS models, “spdep”91 for testing the Moran I, “phytools”92 for testing Pagel’s lambda, “ape”93 for loading the phylogenetic tree, and “multcomp”94 for the Tukey post-hoc comparisons of the GLS models.

Electronic supplementary material

Author Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: G.D., L.S., T.M.E., C.S., P.W., J.U.G. Performed the experiments: G.D., S.J.A.N., M.B., S.B., A.B., L.B., M.C., V.C., M.K.C., A.D., T.M.E., G.H., M.F.K., A.K., M.K., P.L., M.M., I.N., J.O., S.Y.P., O.S., C.S., P.R.S., M.G.T., C.T., I.T., E.R.V., J.U.G. Analyzed the data: G.D., L.S., T.M.E., J.U.G. Contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools: G.D., L.S., S.J.A.N., A.B., V.C., A.D., T.M.E., A.K., M.K., P.L., I.N., S.Y.P., C.S., P.R.S., P.C.W., M.G.T., C.T., E.R.V., J.U.G. Wrote the paper: G.D., L.S., T.M.E., A.K., M.M., A.N., V.N., O.S., J.U.G.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-017-13906-y.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Fleming TH, Breitwisch R, Whitesides GH. Patterns of tropical vertebrate frugivore diversity. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1987;18:91–109. doi: 10.1146/annurev.es.18.110187.000515. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fleming TH, Kress WJ. A brief history of fruits and frugivores. Acta Oecol. 2011;37:521–530. doi: 10.1016/j.actao.2011.01.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jordano, P. Fruits and frugivory. Seeds: The Ecology of Regeneration in Plant Communities, 2ndEdition (ed. Fenner, M.) 125–166 (CABI Publ., 2000).

- 4.Dew, J. L. & Boubli, J. P. T Fruits and Frugivores: The Search for Strong Interactors (Springer, 2005).

- 5.Brockman, D. K. & van Schaik, C. P. 2005 Primate Seasonality: Studies of Living and Extinct Human and Non-Human Primates (Cambridge University Press, 2005).

- 6.Izhaki I, Safriel UN. Why are there so few exclusively frugivorous birds? Experiments on fruit digestibility. Oikos. 1989;54:23–32. doi: 10.2307/3565893. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lambert JE, Fellner V, McKenney E, Hartstone-Rose A. Binturong (Arctictis binturong) and kinkajou (Potos flavus) digestive strategy: implications for interpreting frugivory in Carnivora and Primates. PLoS One. 2014;9:e105415. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mattson WJ. Herbivory in relation to plant nitrogen content. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1980;11:119–161. doi: 10.1146/annurev.es.11.110180.001003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.White, T. C. R. The Inadequate Environment: Nitrogen and the Abundance of Animals (Springer-Verlag, 1993).

- 10.Felton AM, et al. Protein content of diets dictates the daily energy intake of a free-ranging primate. Behav. Ecol. 2009;20:685–690. doi: 10.1093/beheco/arp021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Robbins CT, et al. Optimizing protein intake as a foraging strategy to maximize mass gain in an omnivore. Oikos. 2007;116:1675–1682. doi: 10.1111/j.0030-1299.2007.16140.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kay, R. F. On the use of anatomical features to infer foraging behavior in extinct primates. Adaptation for Foraging in Non-Human Primates (eds Rodman, R. S. & Cant, J. G. H.) 21–53 (Columbia University Press, 1984).

- 13.McKey DB, Gartlan JS, Waterman PG, Choo GM. Food selection by black colobus monkeys (Colobus satanas) in relation to plant chemistry. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 1981;16:115–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8312.1981.tb01646.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oates JF, et al. Determinants of variation in tropical forest primate biomass: new evidence from West Africa. Ecology. 1990;71:328–343. doi: 10.2307/1940272. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rogers ME, Maisels F, Williamson EA, Fernandez M, Tutin CEG. Gorilla diet in the Lope Reserve, Gabon. Oecologia. 1990;84:326–339. doi: 10.1007/BF00329756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ganzhorn JU. Leaf chemistry and the biomass of folivorous primates in tropical forests. Oecologia. 1992;91:540–547. doi: 10.1007/BF00650329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yeager CP, Silver SC, Dierenfeld ES. Mineral and phytochemical influences on foliage selection by the proboscis monkey (Nasalis larvatus) Am. J. Primatol. 1997;41:117–128. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2345(1997)41:2<117::AID-AJP4>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chapman CA, Chapman LJ. Foraging challenges of red colobus monkeys: influence of nutrients and secondary compounds. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2002;133:861–875. doi: 10.1016/S1095-6433(02)00209-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simmen B, Tarnaud L, Marez A, Hladik A. Leaf chemistry as a predictor of primate biomass and the mediating role of food selection: a case study in a folivorous lemur (Propithecus verreauxi) Am. J. Primatol. 2014;76:563–575. doi: 10.1002/ajp.22249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wallis IR, et al. Food for folivores: nutritional explanations linking diets to population density. Oecologia. 2012;169:281–291. doi: 10.1007/s00442-011-2212-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DeGabriel JL, et al. Translating nutritional ecology from the laboratory to the field: milestones in linking plant chemistry to population regulation in mammalian browsers. Oikos. 2014;123:298–308. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0706.2013.00727.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Waterman PG, Ross JAM, Bennett EL, Davies AG. A comparison of the floristics and leaf chemistry of the tree flora in two Malaysian rain forests and the influence of leaf chemistry on populations of colobine monkeys in the Old World. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 1988;34:1–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8312.1988.tb01946.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barton RA, Whiten A. Reducing complex diets to simple rules – food selection by olive baboons. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 1994;35:283–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00170709. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gaulin SJC, Gaulin CK. Behavioural ecology of Alouatta seniculus in Andean cloud forest. Int. J. Primatol. 1982;3:1–32. doi: 10.1007/BF02693488. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kool KM. Food selection by the silver leaf monkey, Trachypithecus auratus sondaicus, in relation to plant chemistry. Oecologia. 1992;90:527–533. doi: 10.1007/BF01875446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ganzhorn JU, et al. The importance of protein in leaf selection of folivorous primates. Am. J. Primatol. 2017;79:e22550. doi: 10.1002/ajp.22550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Milton K, Demment M. Digestion and passage kinetics of chimpanzees fed high and low fiber diets and comparison with human data. J. Nutr. 1988;118:1082–1088. doi: 10.1093/jn/118.9.1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gómez JM, Verdú M. Mutualism with plants drives primate diversification. Syst. Biol. 2012;61:567–577. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syr127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kappeler PM, Heymann EW. Nonconvergence in the evolution of primate life history and socio-ecology. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 1996;59:297–326. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8312.1996.tb01468.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reed KE, Fleagle JG. Geographic and climatic control of primate diversity. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:7874–7876. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Garber, P. A., Righini, N. & Kowalewski, M. Evidence of alternative dietary syndromes and nutritional goals in the Genus Alouatta. Howler Monkeys: Behavior, Ecology and Conservation (eds Kowalewski, M., Garber, P. A., Cortés-Ortiz, L., Urbani, B. & Youlatos, D.) 85–109 (Springer, 2015).

- 32.Britt A. Diet and feeding behaviour of the black-and-white ruffed lemur (Varecia variegata variegata) in the Betampona Reserve, eastern Madagascar. Folia Primatol. 2000;71:133–141. doi: 10.1159/000021741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fleagle JG, Reed KE. Comparing primate communities: a multivariate approach. J. Hum. Evol. 1996;30:489–510. doi: 10.1006/jhev.1996.0039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sato H, et al. Dietary flexibility and feeding strategies of Eulemur: a comparison with. Propithecus. Int. J. Primatol. 2016;37:109–129. doi: 10.1007/s10764-015-9877-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goodman SM, Ganzhorn JU. Rarity of figs (Ficus) on Madagascar and its relationship to a depauperate frugivore community. Rev. Ecol. (Terre Vie) 1997;52:321–329. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kissling WD, Rahbek C, Böhning-Gaese K. Food plant diversity as broad-scale determinant of avian frugivore richness. Proc. Biol. Sc. 2007;274:799–808. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2006.0311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kissling WD, Böhning-Gaese K, Jetz W. The global distribution of frugivory in birds. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2009;18:150–162. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-8238.2008.00431.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Terborgh, J. & van Schaik, C. P. Convergence vs. non-convergence in primate communities. In Organization of communities (eds Gee J. H. R. & Giller, P. S.) 205–226 (Blackwell, 1987).

- 39.Heymann EW. Can phenology explain the scarcity of folivory in New World primates? Am. J. Primatol. 2001;55:171–175. doi: 10.1002/ajp.1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wright PC. Lemur traits and Madagascar ecology: Coping with an island environment. Yrbk. Phys. Anthropol. 1999;42:31–72. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8644(1999)110:29+<31::AID-AJPA3>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stevenson PR. The relationship between fruit production and primate abundance in Neotropical communities. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 2001;72:161–178. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8312.2001.tb01307.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stevenson, P. Potential keystone plant species for the frugivore community at Tinigua Park, Colombia. Tropical Fruits and Frugivores: The Search for Strong Interactors (eds Dew, J. L. & Boubli, J. P.) 37–57 (Springer, 2005).

- 43.Dewar RE, Richard AF. Evolution in the hypervariable environment of Madagascar. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:13723–13727. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704346104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wright, P. C. Behavioral and ecological comparisons of Neotropical and Malagasy primates. New World Primates: Ecology, Evolution, and Behavior (ed. Kinzey, W. G.), 127–141 (Aldine de Gruiter, 1997).

- 45.Ganzhorn, J. U. Body mass, competition and the structure of primate communities. Primate Communities (eds Fleagle, J. F., Janson, C. & Reed, K.) 141–157 (Cambridge University Press, 1999).

- 46.Houle A. The origin of platyrrhines: an evaluation of the Antarctic scenario and the floating island model. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 1999;109:541–559. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8644(199908)109:4<541::AID-AJPA9>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ganzhorn JU, et al. Possible fruit protein effects on primate communities in Madagascar and the Neotropics. PLoS One. 2009;4:e8253. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ganas, J. Foraging strategies of mountain gorillas (Gorilla beringei beringei) in Bwindi Impenetrable National Park, Uganda. PhD Thesis, Universität Leipzig (2007).

- 49.Hladik, C. M. Chimpanzees of Gabon and chimpanzees of Gombe: some comparative data on the diet. Primate Ecology: Studies of Feeding and Ranging Behaviour in Lemurs, Monkeys and Apes (ed. Clutton-Brock, T. H.) 481–501 (Academic Press, 1977).

- 50.Mowry CB, Decker BS, Shure DJ. The role of phytochemistry in dietary choices of Tana River red colobus monkeys (Procolobus badius rufomitratus) Int. J. Primatol. 1996;17:63–84. doi: 10.1007/BF02696159. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dasilva GL. Diet of Colobus polykomos on Tiwai Island: selection of food in relation to its seasonal abundance and nutritional quality. Int. J. Primatol. 1994;15:655–680. doi: 10.1007/BF02737426. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lawler RR, et al. Demography of Verreaux’s sifaka in a stochastic rainfall environment. Oecologia. 2009;161:491–504. doi: 10.1007/s00442-009-1382-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gentry, A. H. Patterns of neotropical plant species diversity. Evolutionary Biology (eds Hecht, M. K., Wallace, B. & Prance, G. T.) 1–84 (Springer, 1982).

- 54.Cork SJ, Catling PC. Modelling distributions of arboreal and ground-dwelling mammals in relation to climate, nutrients, plant chemical defences and vegetation structure in eucalypt forests of Southeastern Australia. Forest Ecol Manag. 1996;85:163–175. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1127(96)03757-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.National Research Council. Nutrient Requirement of Nonhuman Primates (National Academies Press, 2003).

- 56.Kenward RE, Sibly RM. A woodpigeon (Columba palumbus) feeding preference explained by a digestive bottle-neck. J. Appl. Ecol. 1977;14:815–826. doi: 10.2307/2402813. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sibly, R. M. Strategies in digestion and defecation. Physiological Ecology: An Evolutionary Approach to Resource Use (eds Townsend, C. R. & Calow, P.) 109–139 (Sinauer Associates 1981).

- 58.Bollen A, Donati G. Phenology of the littoral forest of Sainte Luce, Southeastern Madagascar. Biotropica. 2005;37:32–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7429.2005.04094.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Foster MS. Ecological and nutritional effects of food scarcity on a tropical frugivorous bird and its fruit source. Ecology. 1977;58:73–85. doi: 10.2307/1935109. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rothman JM, Raubenheimer D, Chapman CA. Nutritional geometry: gorillas prioritize non-protein energy while consuming surplus protein. Biol. Lett. 2011;7:847–849. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2011.0321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Clauss M, et al. The influence of natural diet composition, food intake level, and body size on ingesta passage in primates. Comp. Biochem. Phys. A. 2008;150:274–281. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2008.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lambert JE. Primate digestion: interactions among anatomy, physiology, and feeding ecology. Evol. Anthropol. 1998;7:8–20. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6505(1998)7:1<8::AID-EVAN3>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Donati G, Bollen A, Borgognini-Tarli SM, Ganzhorn JU. Feeding over the 24-h cycle: dietary flexibility of cathemeral collared lemurs (Eulemur collaris) Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2007;61:1237–1251. doi: 10.1007/s00265-007-0354-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Snow DW. Tropical frugivorous birds and their food plants: a world survey. Biotropica. 1981;13:1–14. doi: 10.2307/2387865. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Primack, R. B. & Corlett, R. Tropical Rain Forests: An Ecological and Biogeographical Comparison (Blackwell Publishing, 2005).

- 66.Hawes JE, Peres CA. Ecological correlates of trophic status and frugivory in neotropical primates. Oikos. 2014;123:365–377. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0706.2013.00745.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Peres CA. Effects of hunting on western Amazonian primate communities. Biol. Cons. 1990;54:47–59. doi: 10.1016/0006-3207(90)90041-M. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Halenar LB. Reconstructing the locomotor repertoire of Protopithecus brasiliensis. I. Body size. Anat. Rec. 2011;294:2024–2047. doi: 10.1002/ar.21501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fleagle, J. G. Primate Adaptation and Evolution: 3rd Edition (Academic Press, 2013).

- 70.Federman S, et al. Implications of lemuriform extinctions for the Malagasy flora. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:5041–5046. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1523825113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Felton AM, Felton A, Lindenmayer DB, Foley WJ. Nutritional goals of wild primates. Func. Ecol. 2009;23:70–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2435.2008.01526.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hawes JE, Calouro AM, Peres CA. Sampling effort in Neotropical primate diet studies: collective gains and underlying geographic and taxonomic biases. Int. J. Primatol. 2013;34:1081–1104. doi: 10.1007/s10764-013-9738-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wright, P. C., Razafindratsita, V. R., Pochron, S. T. & Jernvall, J. The key to Madagascar frugivores. Tropical Fruits and Frugivores: The Search for Strong Interactors (eds Dew, J. L. & Boubli, J. P.) 121–138 (Springer, 2005).

- 74.Kappeler PM. Lemur behaviour informs the evolution of social monogamy. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2014;29:591–593. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2014.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Perelman P, et al. A molecular phylogeny of living primates. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1001342. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Nekaris, K. A. I. Mammals of the World 3 – Family Lorisidae (angwantibos, pottos and lorises) (eds Mittermeier, R. A., Rylands, A. B. & Wilson, D. E.) 210–235 (Lynx Editions, 2013).

- 77.Levey DJ, Bissell HA, O’Keefe SF. Conversion of nitrogen to protein and amino acids in wild fruits. J. Chem. Ecol. 2000;26:1749–1763. doi: 10.1023/A:1005503316406. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Helrich, K. Official Methods of the Association of Official Analytical Chemists (AOAC). Association of Official Analytical Chemists (1990).

- 79.Janson, C. H., Stiles, E. W. & White, D. W. Selection of plant fruiting traits by brown capuchin monkeys: a multivariate approach. Frugivores and Seed Dispersal (eds Estrada, A. & Fleming, T. H.) 83–92 (Dr. W. Junk Publishers, 1986).

- 80.Stevenson PR. Fruit choice by woolly monkeys in Tinigua National Park, Colombia. Int. J. Primatol. 2004;25:367–381. doi: 10.1023/B:IJOP.0000019157.35464.a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rowe, N. & Myers, M. All the World’s Primates. Charlestown, RI: Primate Conservation, Inc. Retrieved from http://www.alltheworldsprimates.org (2017).

- 82.Fortin, M. J. & Dale, M. R. Spatial Analysis: A Guide for Ecologists (Cambridge University Press, 2005).

- 83.Beguería S, Pueyo Y. A comparison of simultaneous autoregressive and generalized least squares models for dealing with spatial autocorrelation. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2009;18:273–279. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-8238.2009.00446.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Pinheiro, J. C. & Bates, D. M. Mixed-Effects Models in S and S-Plus (Springer Science & Business Media, 2000).

- 85.Worman COD, Chapman CA. Seasonal variation in the quality of a tropical ripe fruit and the response of three frugivores. J. Trop. Ecol. 2005;21:689–697. doi: 10.1017/S0266467405002725. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Garamszegi, L. Z. Uncertainties due to within-species variation in comparative studies: measurement errors and statistical weights. Modern Phylogenetic Comparative Methods and Their Application in Evolutionary Biology (ed. Garamszegi, L. Z.) 157–199 (Springer, 2014).

- 87.Freckleton RP, Harvey PH, Pagel M. Phylogenetic analysis and comparative data: a test and review of evidence. Am. Nat. 2002;160:712–726. doi: 10.1086/343873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wilson, D. E. & Reeder D. M. Mammal Species of the World (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005).

- 89.R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Retrieved from http://www.R-project.org (2016).

- 90.Pinheiro J, Bates D, DebRoy S, Sarkar DR. Core Team. nlme: linear and nonlinear mixed effects models; 2015. R package version. 2016;3:1–120. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Bivand R, Hauke J, Kossowski T. Computing the Jacobian in Gaussian spatial autoregressive models: an illustrated comparison of available methods. Geogr. Anal. 2013;45:150–179. doi: 10.1111/gean.12008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Revell L. J. phytools: an R package for phylogenetic comparative biology (and other things) Methods Ecol. Evol. 2012;3:217–223. doi: 10.1111/j.2041-210X.2011.00169.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Paradis E, Claude J, Strimmer K. APE: analyses of phylogenetics and evolution in R language. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:289–290. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hothorn T, Bretz F, Westfall P, Heiberger R. M. multcomp: simultaneous inference for general linear hypotheses, 2008. R package version. 2008;0:993–1. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.