Salmonella is one of the most common causes of bacterial foodborne infections in the United States, and the Centers for Disease Control consider multidrug-resistant (MDR) Salmonella a “Serious Threat Level pathogen.” Because MDR Salmonella can lead to more severe disease in patients than that caused by antibiotic-sensitive strains, it is important to identify the role that antibiotics may play in enhancing Salmonella virulence. The current study examined several MDR Salmonella isolates and determined the effect that various antibiotics had on Salmonella motility, an important virulence-associated factor. While most antibiotics had a neutral or negative effect on motility, we found that kanamycin actually enhanced MDR Salmonella swarming in some isolates. Subsequent experiments showed this phenotype as being dependent on a combination of several different genetic factors. Understanding the influence that antibiotics have on MDR Salmonella motility is critical to the proper selection and prudent use of antibiotics for efficacious treatment while minimizing potential collateral consequences.

KEYWORDS: DT104, DT193, Salmonella, Typhimurium, antibiotics, motility, multidrug resistant, swarming, swimming

ABSTRACT

Motile bacteria employ one or more methods for movement, including darting, gliding, sliding, swarming, swimming, and twitching. Multidrug-resistant (MDR) Salmonella carries acquired genes that provide resistance to specific antibiotics, and the goal of our study was to determine how antibiotics influence swimming and swarming in such resistant Salmonella isolates. Differences in motility were examined for six MDR Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium isolates grown on swimming and swarming media containing subinhibitory concentrations of chloramphenicol, kanamycin, streptomycin, or tetracycline. Chloramphenicol and tetracycline reduced both swimming and swarming, though the effect was more pronounced for swimming than for swarming at the same antibiotic and concentration. Swimming was limited by kanamycin and streptomycin, but these antibiotics had much less influence on decreasing swarming. Interestingly, kanamycin significantly increased swarming in one of the isolates. Removal of the aphA1 kanamycin resistance gene and complementation with either the aphA1 or aphA2 kanamycin resistance gene revealed that aphA1, along with an unidentified Salmonella genetic factor, was required for the kanamycin-enhanced swarming phenotype. Screening of 25 additional kanamycin-resistant isolates identified two that also had significantly increased swarming motility in the presence of kanamycin. This study demonstrated that many variables influence how antibiotics impact swimming and swarming motility in MDR S. Typhimurium, including antibiotic type, antibiotic concentration, antibiotic resistance gene, and isolate-specific factors. Identifying these isolate-specific factors and how they interact will be important to better understand how antibiotics influence MDR Salmonella motility.

IMPORTANCE Salmonella is one of the most common causes of bacterial foodborne infections in the United States, and the Centers for Disease Control consider multidrug-resistant (MDR) Salmonella a “Serious Threat Level pathogen.” Because MDR Salmonella can lead to more severe disease in patients than that caused by antibiotic-sensitive strains, it is important to identify the role that antibiotics may play in enhancing Salmonella virulence. The current study examined several MDR Salmonella isolates and determined the effect that various antibiotics had on Salmonella motility, an important virulence-associated factor. While most antibiotics had a neutral or negative effect on motility, we found that kanamycin actually enhanced MDR Salmonella swarming in some isolates. Subsequent experiments showed this phenotype as being dependent on a combination of several different genetic factors. Understanding the influence that antibiotics have on MDR Salmonella motility is critical to the proper selection and prudent use of antibiotics for efficacious treatment while minimizing potential collateral consequences.

INTRODUCTION

Multidrug-resistant (MDR) Salmonella strains are characterized by high levels of antibiotic resistance that are often attributed to the acquisition of specific mechanisms (1). MDR Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium phage types DT104 and DT193 have very similar resistance profiles due to their specialized resistance genes, though the same resistance phenotype can be encoded by different genes. In our previous work, invasion of HEp-2 cells was induced in MDR S. Typhimurium DT193 isolates 1434 and 5317 by the addition of either tetracycline or chloramphenicol at subinhibitory concentrations during the typically noninvasive early-log-growth phase (2). Transcriptome sequencing (RNA-Seq) analysis of these two isolates indicated that genes from at least three Salmonella pathogenicity islands (SPI-1, SPI-2, and SPI-3) were upregulated compared to isolates that did not have an antibiotic-induced invasion phenotype. Interestingly, all isolates tested had a significant and comparable decrease in motility gene expression, independent of invasion phenotype. However, these isolates were all grown in liquid cultures with agitation, and significant gene expression differences between Escherichia coli grown in liquid medium and E. coli grown on semisolid motility medium have been reported (3).

Bacterial chemotaxis and motility are associated with virulence as these processes are thought to be necessary for pathogens to reach specific niches within the host (4–8). Many modes of motility among bacteria exist, though Salmonella primarily employs swimming and swarming (9–11). Swimming is the movement of individual bacteria through a medium, while swarming is the movement of a group of bacteria across a surface (5, 9). Salmonella motility is directly linked to invasion as coordinated regulation of the two systems is required for cellular invasion; genes associated with motility are downregulated as the invasion genes are upregulated (12–15). Previous reports that have examined the effect that antibiotics have on Salmonella motility primarily used sensitive isolates and antibiotic gradients to examine the extent to which the motility phenotype affects resistance to antibiotics (7, 16–19). How different antibiotics influence bacterial motility in MDR Salmonella isolates has not been previously examined. Given the high level of antibiotic resistance among Salmonella isolates (20), the clinical relevance of DT104 and DT193 isolates (21–25), and the observation that MDR Salmonella isolates have increased morbidity in patients compared to sensitive isolates (26–28), it is important to establish the potential collateral consequences that antibiotics may have on virulence mechanisms, including motility. The goal of the current project was to assess the effect that subinhibitory levels of antibiotics have on motility for MDR Salmonella isolates grown on semisolid agar that enables swimming and swarming phenotypes.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Three S. Typhimurium DT193 isolates (1434, 5317, and 752) and three S. Typhimurium DT104 isolates (290, 360, and 530) were selected to identify the effect that chloramphenicol, kanamycin, streptomycin, and tetracycline have on swimming and swarming motility. These six isolates are resistant to ampicillin, chloramphenicol, streptomycin, and tetracycline, as previously reported (2). Isolates 1434, 5317, and 290 are also resistant to kanamycin, and PCR was used to identify the specific kanamycin resistance genes present (Table 1). The resistance genes for chloramphenicol, streptomycin, and tetracycline in these isolates have been identified (2). Growth curves with 2-fold dilutions (0 and 2 to 512 µg/ml) of each of the four antibiotics in liquid LB medium were utilized to determine concentrations that inhibited growth (MIC), if within the range tested (Table 1). All MDR isolates resistant to streptomycin and kanamycin exhibited an MIC that exceeded 512 µg/ml. For a given antibiotic, the MIC of resistant isolates was at least 4-fold above the CLSI resistance breakpoint (chloramphenicol, ≥32; kanamycin, ≥64; streptomycin, ≥64; and tetracycline, ≥16 µg/ml). Antibiotic concentrations below the MIC chosen for use in the motility assays were as follows: 4, 32, and 64 µg/ml chloramphenicol; 32, 128, and 512 µg/ml kanamycin; 32, 128, and 512 µg/ml streptomycin; and 4, 16, and 32 µg/ml tetracycline. For each antibiotic, the CLSI resistance breakpoint fell within the concentration range that was used in the motility assays. All isolates were grown on solid agar plates at the highest concentration of each antibiotic tested in the motility assays to verify that growth was not inhibited at these levels.

TABLE 1 .

Antibiotic resistance genes and MICs for six MDR Salmonella isolates

| Isolate | Chloramphenicol |

Streptomycin |

Kanamycin |

Tetracyclinea |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Presence of resistance gene: |

MIC (µg/ml) | Presence of resistance gene: |

MIC (µg/ml) | Presence of resistance gene: |

MIC (µg/ml) | Presence of resistance gene: |

MIC (µg/ml) | ||||||

| floR | cml | aadA2 | strAB | aphA1 | aphA2 | aadB | tetA | tetG | |||||

| 1434 | + | − | 128 | − | + | >512 | + | − | − | >512 | + | − | 256 |

| 5317 | + | + | 128 | − | + | >512 | + | − | + | >512 | + | − | 256 |

| 752 | + | − | 128 | − | + | >512 | − | − | − | 64b | + | − | 256 |

| 530 | + | − | 128 | + | − | >512 | − | − | − | 64b | − | + | 64 |

| 290 | + | − | 128 | + | − | >512 | + | − | − | >512 | − | + | 64 |

| 360 | + | − | 256 | + | − | >512 | − | − | − | 64b | − | + | 64 |

No isolates had tetB, tetC, or tetD.

Antibiotic sensitive.

Effects of antibiotics on MDR isolate motility. (i) Chloramphenicol.

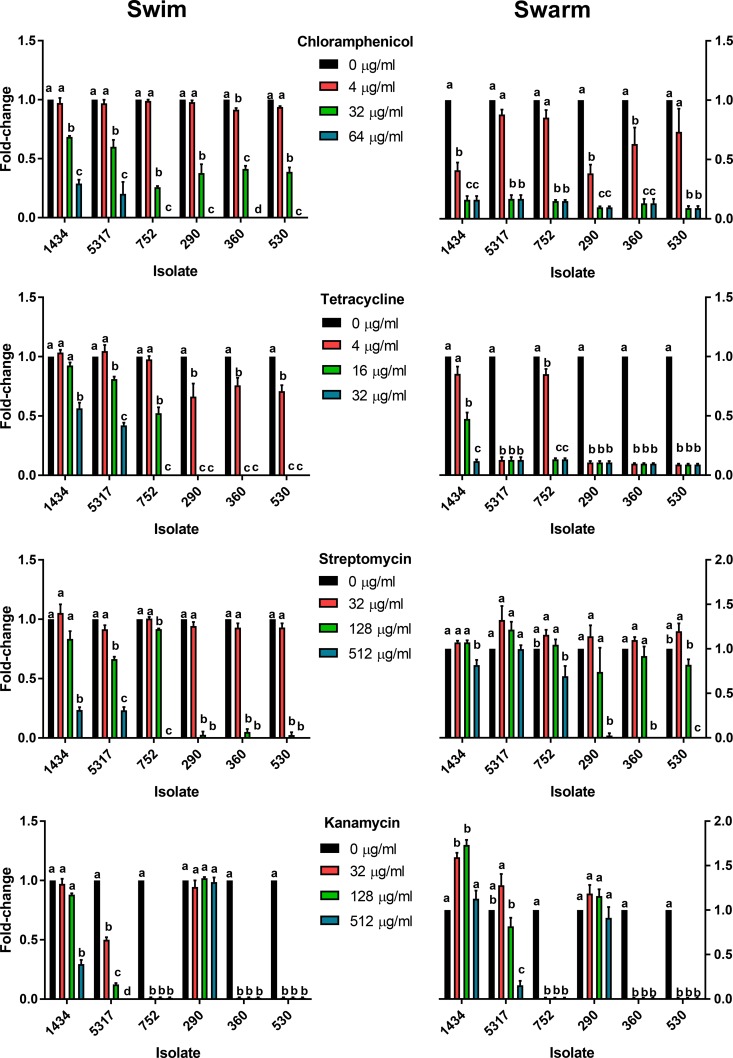

For swimming motility, the lowest level of chloramphenicol tested (4 µg/ml) significantly inhibited swimming of isolate 360 compared to the no-antibiotic control, though the same concentration significantly inhibited swarming for isolates 360, 1434, and 290 (Fig. 1). At 32 and 64 µg/ml, both swimming and swarming were significantly reduced compared to the no-antibiotic control in all isolates tested. A significant difference was observed between 32 and 64 µg/ml for swimming but not for swarming, as there was little to no swarming motility at either of these concentrations. At any given concentration, chloramphenicol had a greater effect on limiting swarming than on limiting swimming; for example, 32 µg/ml substantially reduced swarming and yet only moderately decreased swimming motility.

FIG 1 .

Effect of antibiotics on swimming and swarming motility in MDR Salmonella isolates. Chloramphenicol, tetracycline, streptomycin, and kanamycin at indicated concentrations were added to swimming and swarming agar media to determine their effect on motility in six MDR S. Typhimurium isolates. Growth was normalized to the no-antibiotic control for each isolate, and data were expressed as fold changes for all pairwise comparisons for each antibiotic, isolate, and motility combination. Statistical differences are noted by letters (P < 0.05), where any pairwise combination that shares the same letter is not considered different.

(ii) Tetracycline.

Tetracycline at 4 µg/ml significantly decreased swimming in the DT104 isolates (290, 360, and 530) but not the DT193 isolates (Fig. 1). Compared to the control without tetracycline, swimming motility was significantly decreased due to 16 µg/ml of tetracycline for all isolates except 1434, while 32 µg/ml inhibited all isolates tested. Not including isolate 1434, swarming motility was significantly decreased for all isolates due to 4 µg/ml of tetracycline; at 16 and 32 µg/ml of tetracycline, swarming motility was significantly decreased for all isolates. Similarly to chloramphenicol, tetracycline appeared to have a greater effect on reducing swarming than on reducing swimming at the same antibiotic concentration.

(iii) Streptomycin.

Streptomycin at 128 µg/ml significantly decreased swimming in all isolates compared to the no-antibiotic control except for isolate 1434, while the same concentration had no effect on swarming in any of the isolates (Fig. 1). All isolates had significantly reduced motility at 512 µg/ml of streptomycin, except swarming for isolates 5317 and 752. The level of decreased swarming at 512 µg/ml is noteworthy as DT193 isolates were reduced in swarming by 0 to 31% compared to the control, while at this concentration the three DT104 isolates did not swarm at all. Additionally, isolate 5317 had a nonsignificant increase in swarming at 32 µg/ml compared to the control. The degree to which streptomycin appears to limit swimming was greater than that for swarming at equivalent streptomycin concentrations, which was the converse of the results for chloramphenicol and tetracycline.

(iv) Kanamycin.

Only three of the six isolates were resistant to kanamycin (1434, 5317, and 290), and the three kanamycin-sensitive MDR isolates did not exhibit any motility at any kanamycin concentration tested (Fig. 1). Kanamycin did not influence swimming or swarming in isolate 290. Isolate 1434 had reduced swimming at 512 µg/ml. All tested concentrations decreased swimming for isolate 5317, while swarming was reduced only at 512 µg/ml. Similar to the streptomycin results, isolate 5317 had a nonsignificant increase in swarming at 32 µg/ml compared to the control. Notably, kanamycin significantly increased swarming at 32 and 128 µg/ml for isolate 1434, but not at 512 µg/ml. Isolates 1434, 5317, and 290 all had various motility phenotypes within and between isolates in response to kanamycin, and yet kanamycin resistance in all three isolates was encoded by an aphA1 gene. Genetic factors beyond the presence of the resistance mechanism likely play a role in how kanamycin influences motility between isolates, as well as differences in gene regulation at the various antibiotic concentrations for a specific isolate. Additionally, the highest concentrations of kanamycin may lead to the induction of the SOS response in some isolates, which has been shown to reduce the swarming phenotype (29, 30).

Overall, the effect of different antibiotics on MDR Salmonella swimming and swarming motility was determined by the combination of isolate, antibiotic, and antibiotic concentration. None of the isolates were natively hypermotile, as the motility phenotypes were relatively similar between the isolates. One interesting relationship between chloramphenicol and tetracycline, which have resistance factors encoded by tet and floR efflux pumps, respectively (31, 32), was the greater negative impact on swarming than on swimming at the same antibiotic concentration. This was the opposite of what was observed for kanamycin and streptomycin, as they had more of an inhibitory effect on swimming than on swarming, with swarming being significantly enhanced in one instance. Kanamycin and streptomycin resistance are encoded by genes for aminoglycoside inactivation enzymes (33), and the difference between the effect of these antibiotics on motility and that of chloramphenicol and tetracycline could be due to the difference in the mechanism or regulation of these resistance factors; previous studies have demonstrated a relationship between innate efflux pumps and motility (34–36). However, antibiotic-induced decreases in motility may not necessarily decrease virulence. We previously have found that 16 µg/ml tetracycline and 32 µg/ml chloramphenicol can downregulate genes associated with motility when strains are grown in LB broth but can also induce the invasive phenotype in isolates 1434 and 5317 (2). These tetracycline and chloramphenicol concentrations are at the CLSI resistance breakpoints for Salmonella Typhimurium that are predictive of whether a microorganism will respond to antibiotic therapy.

Role of the kanamycin resistance gene in swarming.

To evaluate the role of the aphA1 gene in the kanamycin-enhanced swarming phenotype observed for isolate 1434, several mutants that removed the kanamycin resistance gene were created and were subsequently complemented with different resistance genes (Table 2). The aphA1 gene was deleted from the 1434-derived BBS1156 mutant to create 1434ΔaphA1 (BBS1182). Also, because motility plays a role in regulating the type III secretion system required for cellular invasion, the SPI-1 gene hilA was deleted from the BBS1182 strain to create 1434ΔaphA1ΔhilA (BBS1211). Kanamycin resistance was restored to both of these mutants by transformation with the E. coli-derived pACYC177 plasmid that carries aphA1 to create 1434ΔaphA1/aphA1pACYC (strain BBS1213) and 1434ΔaphA1ΔhilA/aphA1pACYC (BBS1215). A 1434ΔaphA1 sensitive mutant was also restored using the E. coli-derived pCR plasmid that carries aphA2 to create 1434ΔaphA1/aphA2pCR (BBS1219). While functionally similar, aphA1 and aphA2 share only ~45% nucleotide identity. A Salmonella-derived plasmid from DT104 isolate 745 that carries aphA1 was transduced into 1434ΔaphA1 to create 1434ΔaphA1/aphA1p745 (BBC1501). The same plasmid was also transduced into the kanamycin-sensitive DT193 isolate 752 to create 752/aphA1p745 (BBC1502).

TABLE 2 .

Kanamycin-sensitive isolates and mutants, as well as the plasmids and genes used to restore resistance

| Strain | Parent | aphA1 | hilA | Plasmid | Kan Compa | MIC (µg/ml) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BBS1213 | 1434 | ΔaphA1 | hilAWTb | pACYC177 | aphA1 | >512 |

| BBS1215 | 1434 | ΔaphA1 | ΔhilA | pACYC177 | aphA1 | >512 |

| BBS1219 | 1434 | ΔaphA1 | hilAWT | pCR | aphA2 | >512 |

| BBC1501 | 1434 | ΔaphA1 | hilAWT | p745 | aphA1 | >512 |

| BBC1502 | 752 | —c | hilAWT | p745 | aphA1 | >512 |

Kan Comp, kanamycin complementation.

WT, wild type.

—, not present in wild type.

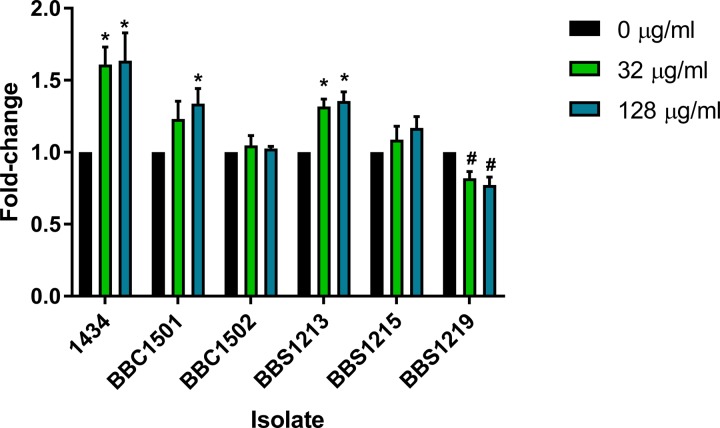

The mutant isolates, along with the 1434 wild-type isolate, were inoculated onto swarming medium containing 0, 32, or 128 µg/ml of kanamycin (Fig. 2). The swarming data indicated that deletion and replacement of the aphA1 gene carried on a Salmonella-derived plasmid restored kanamycin-enhanced swarming at 128 µg/ml in strain 1434ΔaphA1/aphA1p745, though 32 µg/ml had a nonsignificant increase. However, adding the same plasmid to a different DT193 kanamycin-sensitive isolate in strain 752/aphA1p745 did not enhance swarming motility, indicating that more than just the presence of the aphA1 gene is required to observe kanamycin-enhanced swarming. Therefore, genetic factors encoded within 1434, but absent from 752, are necessary for the kanamycin-induced motility phenotype. To assess if a non-Salmonella-derived plasmid carrying aphA1 could restore the kanamycin-enhanced swarming phenotype, strain 1434ΔaphA1/aphA1pACYC was tested and found to have a significantly enhanced swarming phenotype due to kanamycin at both 32 and 128 µg/ml. The genetic factor required for kanamycin enhancement may require the hilA gene, as strain 1434ΔaphA1ΔhilA/aphA1pACYC had a small but nonsignificant increase in swarming in the presence of kanamycin. Finally, restoring resistance to the sensitive 1434 mutant with the aphA2 gene in strain 1434ΔaphA1/aphA2pCR actually led to a significant decrease in swarming in the presence of kanamycin. Despite pCR/aphA2 being a higher-copy-number plasmid than pACYC/aphA1 (~100 copies compared to ~15, respectively), pCR/aphA2 still failed to complement the kanamycin-enhanced swarming phenotype. Together, these data indicate that the aphA1 gene, along with unknown Salmonella genetic factors, was required for the kanamycin-enhanced swarming phenotype.

FIG 2 .

Swarming motility of kanamycin-complemented sensitive isolates and mutants. A kanamycin-sensitive isolate and several sensitive deletion mutants were complemented with plasmids of either Salmonella or E. coli origin containing different kanamycin resistance genes (aphA1 or aphA2). The resulting strains were then tested to determine the role that different combinations of resistance genes and plasmid backgrounds had on enhancing swarming due to the presence of kanamycin in the motility medium (0, 32, and 128 µg/ml). Growth was normalized to the no-antibiotic control for each isolate, and data were expressed as a fold change between the control and each treatment. Statistical increases are noted by asterisks, and decreases are noted by number signs (P < 0.05). BBC1501 = 1434ΔaphA1/aphA1p745; BBC1502 = 752/aphA1p745; BBS1213 = 1434ΔaphA1/aphA1pACYC; BBS1215 = 1434ΔaphA1ΔhilA/aphA1pACYC; BBS1219 = 1434ΔaphA1/aphA2pCR.

Screening additional kanamycin-resistant isolates.

To establish if the kanamycin-enhanced motility phenotype occurred in other MDR isolates similar to 1434, 25 additional kanamycin-resistant DT193 isolates were tested at 128 µg/ml in swarming medium. Out of these 25 isolates, three isolates demonstrated an increase in motility, with two isolates being significantly enhanced (Table 3). Isolates 413, 9853, and 18599 all carry the kanamycin resistance gene aphA1, while 9853 and 18599 also carry aadB. We observed a significant kanamycin-induced motility phenotype in 3 of 28 (~11%) DT193 isolates from our collection, and it would be interesting to identify the presence of this phenotype in a larger and more diverse Salmonella population. It would also be worthwhile to ascertain if this effect is more prevalent in S. Typhimurium isolated from turkeys, as turkeys have a higher level of kanamycin-resistant S. Typhimurium (34%) than do cattle (24%), pigs (10%), chickens (8%), and humans (6%) over a 10-year period (20).

TABLE 3 .

Swarming motility differences and kanamycin resistance gene profiles for three DT193 isolates screened for enhanced-swarming phenotype at 128 µg/ml kanamycin compared to a no-antibiotic control

| Isolate | Fold change ± SEM | P value | Kanamycin |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Presence of resistance gene: |

MIC (µg/ml) | |||||

| aphA1 | aphA2 | aadB | ||||

| 413 | 1.55 ± 0.28 | 0.13 | + | − | − | >512 |

| 9853 | 1.25 ± 0.05 | 0.02 | + | − | + | >512 |

| 18599 | 1.63 ± 0.11 | <0.01 | + | − | + | >512 |

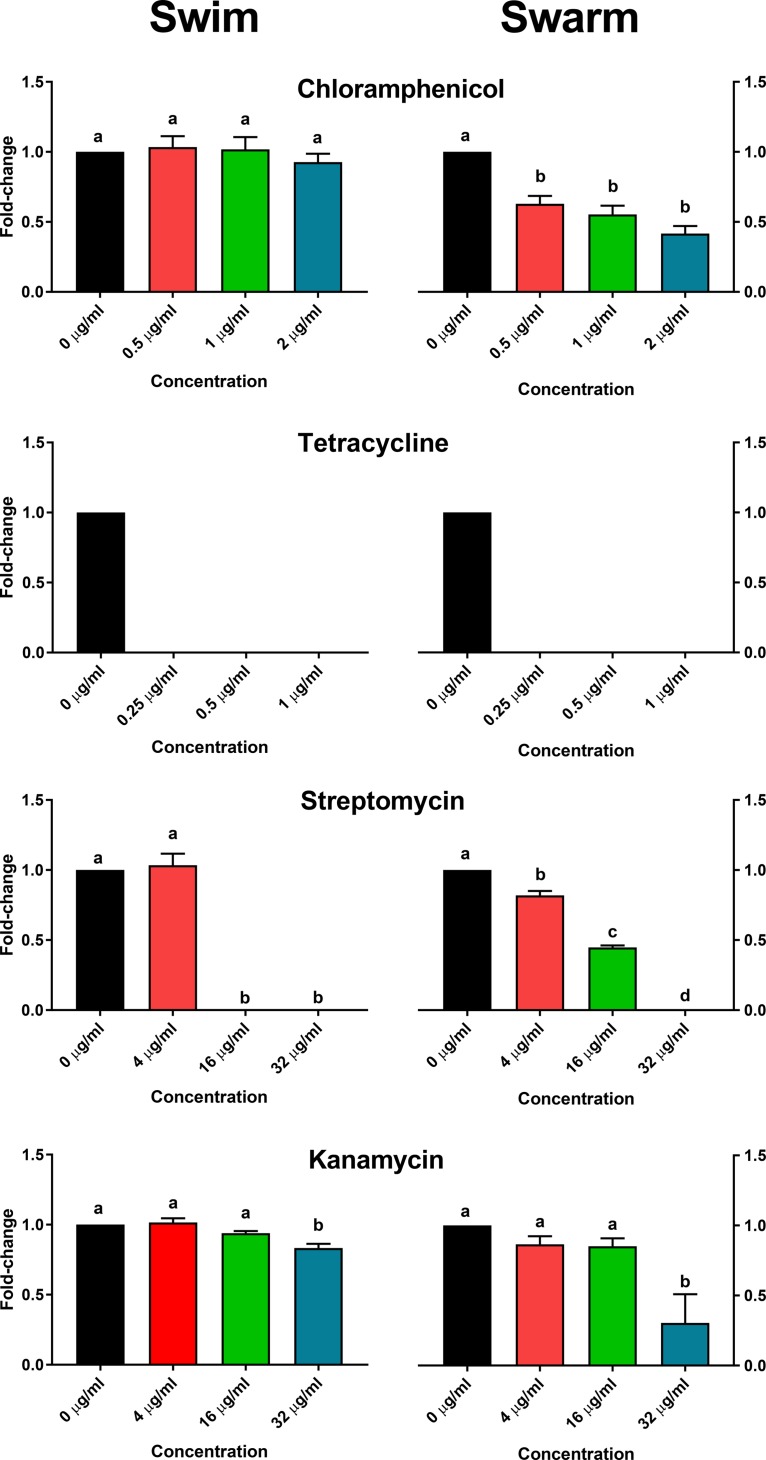

Effect of antibiotics on motility of an antibiotic-sensitive isolate.

S. Typhimurium isolate SARB65 is sensitive to the antibiotics used in this study and was tested to identify similarities and differences between the MDR isolates. As sensitive isolates typically utilize innate resistance mechanisms (i.e., AcrAB-TolC) that have different and lower inhibitory thresholds than those of isolates with specific resistance mechanisms (1), the MIC for SARB65 was determined for chloramphenicol (4 µg/ml), kanamycin (64 µg/ml), streptomycin (64 µg/ml), and tetracycline (2 µg/ml). Based on this, swimming and swarming assays were performed at various subinhibitory concentrations relative to the MIC of each antibiotic (Fig. 3). Chloramphenicol had no effect on swimming but significantly decreased swarming, similar to the trend observed in the MDR isolates. Tetracycline prevented all swimming and swarming motility, which diverges from what was observed in the MDR isolates. At 4 µg/ml, streptomycin did not influence swimming but significantly reduced swarming, while 16 and 32 µg/ml limited or inhibited both motility phenotypes. Finally, kanamycin did not influence motility at 4 or 16 µg/ml but significantly reduced both swimming and swarming at 32 µg/ml. A significantly reduced swarming phenotype for SARB65 in the presence of 32 µg/ml kanamycin is consistent with MDR isolates 752, 360, and 530, which are also kanamycin sensitive, but differs from the kanamycin-resistant MDR isolates containing aphA1 (1434, 5317, and 290) where swarming either remained similar to the no-antibiotic control or was enhanced. While there is some overlap of antibiotic-influenced motility between the sensitive and MDR isolates, it is likely that the different resistance mechanisms and genetics of the isolates influence the observed swimming and swarming phenotypes.

FIG 3 .

Effect of antibiotics on swimming and swarming motility in an antibiotic-sensitive isolate of Salmonella. Chloramphenicol, tetracycline, streptomycin, and kanamycin were added at various subinhibitory concentrations to swimming and swarming agar media to determine their effect on motility in the antibiotic-sensitive S. Typhimurium isolate SARB65. Growth was normalized to the no-antibiotic control for each isolate, and data were expressed as a fold change for all pairwise comparisons for each antibiotic and motility combination. Statistical differences are noted by letters (P < 0.05), where any pairwise combination that shares the same letter is not considered different.

Conclusion.

In this study, we assessed the effect that four different antibiotics had on MDR Salmonella motility when grown on swimming and swarming medium. In general, these antibiotics either decreased or had no effect on motility. A decrease in motility, however, may not always be beneficial for reducing virulence, as our previous work demonstrated that tetracycline and chloramphenicol can downregulate motility gene expression while simultaneously inducing cellular invasion in vitro. Notably, kanamycin significantly enhanced swarming in a subset of isolates. Further analysis indicated that the aphA1 resistance gene and a Salmonella-specific genetic component were both required in order to observe this phenotype. Given the relationship between motility and virulence in Salmonella, it is important to better understand the role that antibiotics may have in promoting potential collateral effects in MDR isolates.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolates and growth conditions.

The isolates and mutants utilized in the study are listed in Table 4. Salmonella DT104 and DT193 isolates were from our archive of clinical samples originally cultured from cattle. The antibiotic-sensitive S. Typhimurium isolate SARB65 is from the Salmonella Reference Collection B (37). Each Salmonella isolate was streaked onto solid LB (Lennox L) agar plates (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). A colony was grown in LB broth at 37°C with agitation for 6 h followed by a 1:1,000 dilution in LB broth that was grown overnight at 37°C with agitation. The overnight culture was diluted 1:200 in LB broth and grown at 37°C with agitation to an approximate optical density at 600 nm (~OD600) of 0.3.

TABLE 4 .

Strains used in the study

| Strain no |

S. Typhimurium strain background |

Genotype | Resistance phenotype |

|---|---|---|---|

| DT193 1434 | 1434 | Wild type | Apr Camr Strepr Tetr Knr |

| DT193 5317 | 5317 | Wild type | Apr Camr Strepr Tetr Knr |

| DT193 752 | 752 | Wild type | Apr Camr Strepr Tetr |

| DT104 530 | 530 | Wild type | Apr Camr Strepr Tetr |

| DT104 290 | 290 | Wild type | Apr Camr Strepr Tetr Knr |

| DT104 360 | 360 | Wild type | Apr Camr Strepr Tetr |

| DT193 413 | 413 | Wild type | Apr Camr Strepr Tetr Knr |

| DT193 18599 | 18599 | Wild type | Apr Camr Strepr Tetr Knr |

| DT193 9853 | 9853 | Wild type | Apr Camr Strepr Tetr Knr |

| BBS996 | 1434 | pKD46-Gm | Apr Camr Strepr Tetr Knr Gmr 30°Ca |

| BBS1156 | 1434 | aphA1::zeo | Apr Camr Strepr Tetr Zeor |

| BBS1182 | 1434 | ΔaphA1 | Apr Camr Strepr Tetr |

| BBS1206 | 1434 | ΔaphA1/pKD46-Gm | Apr Camr Strepr Tetr Gmr 30°Ca |

| BBS1208 | 1434 | ΔaphA1 hilA::neo | Apr Camr Strepr Tetr Knr |

| BBS1211 | 1434 | ΔaphA1 ΔhilA | Apr Camr Strepr Tetr |

| BBS1213 | 1434 | ΔaphA1/pACYC177 | Apr Camr Strepr Tetr Knr |

| BBS1215 | 1434 | ΔaphA1ΔhilA/pACYC177 | Apr Camr Strepr Tetr Knr |

| BBS1219 | 1434 | ΔaphA1/pCR | Apr Camr Strepr Tetr Knr Zeor |

| BBC1501 | 1434 | ΔaphA1/p745-aphA1 | Apr Camr Strepr Tetr Knr |

| BBC1502 | 752 | p745-aphA1 | Apr Camr Strepr Tetr Knr |

| SARB65 | SARB65 | Wild type | Sensitive |

Temperature-sensitive phenotype.

Antibiotic resistance characterization.

Selected isolates were tested for resistance to kanamycin by streaking on solid LB agar plates with 50 µg/ml kanamycin. The inhibitory concentrations for kanamycin were evaluated by growth with serial 2-fold dilutions of the antibiotic (0 and 2 to 512 µg/ml) using a Bioscreen C instrument (Growth Curves Ltd., Raisio, Finland), where optical density measurements were taken once an hour for 24 h to establish a growth curve for each isolate and antibiotic concentration. The inhibitory concentrations for chloramphenicol, streptomycin, and tetracycline were determined previously using the same methodology for the MDR isolates (2). For the antibiotic-sensitive SARB65 isolate, the inhibitory concentrations were determined by growth with serial 2-fold dilutions of chloramphenicol (0 and 0.125 to 32 µg/ml), streptomycin (0 and 2 to 512 µg/ml), and tetracycline (0 and 0.125 to 32 µg/ml). Isolates were streaked onto solid LB agar containing antibiotics at the concentrations selected for use in the motility assays to confirm normal growth on nonmotility medium. Genes associated with kanamycin resistance were assessed in all resistant isolates by PCR (Table 5). MDR isolates were previously screened for the following resistance genes: cat, cml, and floR (chloramphenicol); aadA2, strA, and strB (streptomycin); tetA, -B, -C, -D, and -G (tetracycline) (2).

TABLE 5 .

Primers used in the study

| Primer purpose | Gene (GenBank accession no.) | Primer name | Sequence (5′ to 3′) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Detection of kanamycin resistance genes | aphA1 (AF093572) | aphA1-F | CGTCAGCCAGTTTAGTCTG |

| aphA1-R | CAATCAGGTGCGACAATC | ||

| aphA2 (U66885) | aphA2-F | GGCTATTCGGCTATGACTG | |

| aphA2-R | GGACAGGTCGGTCTTGAC | ||

| aadB (JN119852) | aadB-F | TACTATGCCGATGAAGTACC | |

| aadB-R | CAAGACCTCAACCTTTTCC | ||

| Amplification of zeo in pCR-Blunt | zeo | oBBI 465 | CGATAGCTGAATGAGTGACGTGCTGAAGTTCCTATACTTTCTAGAGAATAGGAACTTCGCTTACAATTTCCTGATGCa |

| oBBI 466 | GCATAGAGCAGTGACGTAGTCGCGAAGTTCCTATTCTCTAGAAAGTATAGGAACTTCACGTGTCAGTCCTGCTCCa | ||

| Synthesis of an aphA1 knockout fragment by amplification of oBBI 465/466-zeo | aphA1 | oBBI 467 | CAAGATAAAAATATATCATCATGAACAATAAAACTGTCTGCTTACGATAGCTGAATGAGTGACGTGCb |

| oBBI 468 | GGATACTGCCAGATATCGGCGTCCAGGGAGATGTCCTGAAGCATAGAGCAGTGACGTAGTCGCb | ||

| Synthesis of a hilA knockout fragment by amplification of oBBI 92/93-neo | hilA | oBBI 490 | GAATACACTATTATCATGCCACATTTTAATCCTGTTCCTGTATCGATAGCTGAATGAGTGACGTGCc |

| oBBI 491 | CAAATATTGTCTTCGTTTTTAAATTTATTCCACATTTTCTCGGCATAGAGCAGTGACGTAGTCGCc |

The 5′ end contains a universal binding region and FRT sites. The underlined sequences bind pCR-Blunt to amplify zeo.

Boldface indicates homology to aphA1 for gene knockout. Underlined sequences bind oBBI 465/466-zeo.

Boldface indicates homology to hilA for gene knockout. Underlined sequences bind oBBI 92/93-neo.

Motility assays.

Based on the growth curve data, motility assays were performed in swimming and swarming media containing antibiotics at the indicated subinhibitory concentrations for the MDR isolates: chloramphenicol, 0, 4, 32, and 64 µg/ml; kanamycin, 0, 32, 128, and 512 µg/ml; streptomycin, 0, 32, 128, and 512 µg/ml; and tetracycline, 0, 4, 16, and 32 µg/ml. The following antibiotics and concentrations were used for the antibiotic-sensitive SARB65 isolate: chloramphenicol, 0, 0.5, 1, and 2 µg/ml; kanamycin, 0, 4, 16, and 32 µg/ml; streptomycin, 0, 4, 16, and 32 µg/ml; and tetracycline, 0, 0.25, 0.5, and 1 µg/ml. The 0.3% agar LB swim medium contained 10 g Bacto tryptone, 5 g Bacto yeast extract, 5 g NaCl, and 3 g Bacto agar in 1 liter deionized water. The 0.5% agar LB swarm medium contained 10 g Bacto tryptone, 5 g Bacto yeast extract, 5 g NaCl, and 5 g Bacto agar in 975 ml deionized water (3, 38). Motility medium was autoclaved and placed in a 56°C water bath. After the medium reached 56°C, antibiotics at the appropriate concentrations were added. For the swarming medium, 25 ml of a 20% stock glucose solution per liter was added (for a final glucose concentration of 0.5%). Twenty-five milliliters of medium was pipetted into 100- by 15-mm culture plates, which were covered and allowed to cool and solidify for 30 min.

A 5-µl aliquot of Salmonella culture at an OD600 of 0.3 (as described above) was placed in the center of each plate, covered, and allowed to rest for 5 to 10 min. The plates were placed in a 37°C humid incubator for ~5 h (swimming) or ~10 h (swarming). Two technical replicates were performed for each condition. Diameters of bacterial swimming and swarming were measured and normalized to the no-antibiotic control. Each condition was tested three or more separate times and analyzed for differences using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a Tukey posttest for all pairwise comparisons for each antibiotic and isolate combination.

Mutants.

Due to the MDR genotype of S. Typhimurium 1434, we were unable to utilize gene knockout cassettes that relied on chloramphenicol or kanamycin antibiotic selection that we have previously designed and constructed for generating numerous recombineering mutants. Instead, we modified our previous universal FLP recombination target (FRT) primers to incorporate nucleotide sequences for the amplification of the zeo gene encoding resistance to zeomycin as a substitution for cat or neo (Table 5). The first 58 nucleotides of the oBBI 465 primer were identical to oBBI 88 and contained a universal primer binding region for cassette amplification and an FRT site for FLP recombinase (39). The oBBI 466 primer had a similar design as oBBI 465 with the first 58 nucleotides being identical to oBBI 89 and containing a universal primer binding region and an FRT site. The universal primer binding sites had stop codons in all three translational reading frames to truncate protein synthesis of the target gene. The 3′ end of oBBI 465 had 20 nucleotides that bind ~197 to 178 bp upstream of the start codon for the zeo gene in pCR-Blunt (Invitrogen). Likewise, the 3′ end of oBBI 466 contained 19 nucleotides of pCR-Blunt sequence that overlaps the zeo stop codon. The zeo gene in pCR-Blunt was amplified by PCR to synthesize an oBBI 465/466-zeo template. To construct an aphA1 mutant of S. Typhimurium 1434, primers oBBI 467 and oBBI 468 were used to PCR amplify the oBBI 465/466-zeo template, and the knockout fragment was gel purified and transformed into arabinose-induced BBS996 containing pKD46-Gm (40). A zeomycin-resistant derivative of 1434 was selected and named BBS1156. The zeo gene was deleted from BBS1156 by transformation with pCP20-Gm and screening for a zeomycin-sensitive derivative which was subsequently named BBS1182 (40). The 1434ΔaphA1ΔhilA mutant (BBS1211) was constructed using similar methods except that an oBBI 490/491-neo gene knockout fragment was constructed by amplifying oBBI 92/93-neo (41), followed by transformation and selection for kanamycin. Complementation of the kanamycin-sensitive phenotypes for BBS1182 and BBS1211 was performed using one of several plasmids that carried either aphA1 or aphA2 kanamycin resistance genes from pACYC177 (New England Biolabs [42]) and a derivative of pCR-Blunt (Invitrogen), respectively. A plasmid native to S. Typhimurium DT104 isolate 745 carrying aphA1 and conferring kanamycin resistance was previously described (43). The kanamycin resistance plasmid from 745 (p745) was isolated and transformed into BBS1182 and a kanamycin-sensitive DT193 isolate, 752, to construct strains BBC1501 and BBC1502. The mutant isolates were inoculated on swarm medium, as described above, that contained 0, 32, or 128 µg/ml kanamycin. A one-way ANOVA with the Dunnett posttest was used to determine differences in motility compared to the no-antibiotic control for each isolate.

Screening of additional DT193 isolates for kanamycin-enhanced swarming.

Thirty-one additional DT193 isolates from our collection were streaked on LB plates containing 50 µg/ml kanamycin to screen for resistance. Twenty-five isolates were identified as resistant, and these were inoculated on swarm medium (as described above) containing either 0 or 128 µg/ml kanamycin. Isolates that demonstrated a potential for enhanced swarm motility were tested at least two additional times. The Student t test was used to determine significant differences between the control and antibiotic-treated isolates.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Briony Atkinson and Kellie Winter for their extraordinary technical assistance. The pKD46-Gm and pCP20-Gm plasmids were kindly provided by Benoît Doublet.

This research was supported by USDA ARS funds.

Mention of trade names or commercial products in this article is solely for the purpose of providing specific information and does not imply recommendations or endorsement by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. USDA is an equal opportunity employer.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brunelle BW, Bearson BL, Allen HK. 2017. Prevalence, evolution, and dissemination of antibiotic-resistance in Salmonella, p 331–348. In Singh OV (ed), Foodborne pathogens and antibiotic resistance. John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, NJ. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brunelle BW, Bearson BL, Bearson SM. 2014. Chloramphenicol and tetracycline decrease motility and increase invasion and attachment gene expression in specific isolates of multidrug-resistant Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Front Microbiol 5:801. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lippolis JD, Brunelle BW, Reinhardt TA, Sacco RE, Thacker TC, Looft TP, Casey TA. 2016. Differential gene expression of three mastitis-causing Escherichia coli strains grown under planktonic, swimming, and swarming culture conditions. mSystems 1:e00064-16. doi: 10.1128/mSystems.00064-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Josenhans C, Suerbaum S. 2002. The role of motility as a virulence factor in bacteria. Int J Med Microbiol 291:605–614. doi: 10.1078/1438-4221-00173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kearns DB. 2010. A field guide to bacterial swarming motility. Nat Rev Microbiol 8:634–644. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Verstraeten N, Braeken K, Debkumari B, Fauvart M, Fransaer J, Vermant J, Michiels J. 2008. Living on a surface: swarming and biofilm formation. Trends Microbiol 16:496–506. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harshey RM, Partridge JD. 2015. Shelter in a swarm. J Mol Biol 427:3683–3694. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2015.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Partridge JD, Harshey RM. 2013. Swarming: flexible roaming plans. J Bacteriol 195:909–918. doi: 10.1128/JB.02063-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harshey RM. 2003. Bacterial motility on a surface: many ways to a common goal. Annu Rev Microbiol 57:249–273. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.57.030502.091014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Park SY, Pontes MH, Groisman EA. 2015. Flagella-independent surface motility in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112:1850–1855. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1422938112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jarrell KF, McBride MJ. 2008. The surprisingly diverse ways that prokaryotes move. Nat Rev Microbiol 6:466–476. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iyoda S, Kamidoi T, Hirose K, Kutsukake K, Watanabe H. 2001. A flagellar gene fliZ regulates the expression of invasion genes and virulence phenotype in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Microb Pathog 30:81–90. doi: 10.1006/mpat.2000.0409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lucas RL, Lostroh CP, DiRusso CC, Spector MP, Wanner BL, Lee CA. 2000. Multiple factors independently regulate hilA and invasion gene expression in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J Bacteriol 182:1872–1882. doi: 10.1128/JB.182.7.1872-1882.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hébrard M, Kröger C, Sivasankaran SK, Händler K, Hinton JC. 2011. The challenge of relating gene expression to the virulence of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Curr Opin Biotechnol 22:200–210. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2011.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saini S, Slauch JM, Aldridge PD, Rao CV. 2010. Role of cross talk in regulating the dynamic expression of the flagellar Salmonella pathogenicity island 1 and type 1 fimbrial genes. J Bacteriol 192:5767–5777. doi: 10.1128/JB.00624-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Butler MT, Wang Q, Harshey RM. 2010. Cell density and mobility protect swarming bacteria against antibiotics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:3776–3781. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910934107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hol FJ, Hubert B, Dekker C, Keymer JE. 2016. Density-dependent adaptive resistance allows swimming bacteria to colonize an antibiotic gradient. ISME J 10:30–38. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2015.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim W, Killam T, Sood V, Surette MG. 2003. Swarm-cell differentiation in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium results in elevated resistance to multiple antibiotics. J Bacteriol 185:3111–3117. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.10.3111-3117.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lai S, Tremblay J, Déziel E. 2009. Swarming motility: a multicellular behaviour conferring antimicrobial resistance. Environ Microbiol 11:126–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2008.01747.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Food and Drug Administration 2013. National antimicrobial resistance monitoring system—enteric bacteria (NARMS): 2011 executive report. Food and Drug Administration, US Department of Health and Human Services, Rockville, MD. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adaska JM, Silva AJ, Berge AC, Sischo WM. 2006. Genetic and phenotypic variability among Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium isolates from California dairy cattle and humans. Appl Environ Microbiol 72:6632–6637. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01038-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bergeron N, Corriveau J, Letellier A, Daigle F, Quessy S. 2010. Characterization of Salmonella Typhimurium isolates associated with septicemia in swine. Can J Vet Res 74:11–17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dechet AM, Scallan E, Gensheimer K, Hoekstra R, Gunderman-King J, Lockett J, Wrigley D, Chege W, Sobel J, Multistate Working Group . 2006. Outbreak of multidrug-resistant Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium definitive type 104 infection linked to commercial ground beef, northeastern United States, 2003–2004. Clin Infect Dis 42:747–752. doi: 10.1086/500320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gebreyes WA, Altier C. 2002. Molecular characterization of multidrug-resistant Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhimurium isolates from swine. J Clin Microbiol 40:2813–2822. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.8.2813-2822.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gebreyes WA, Thakur S, Davies PR, Funk JA, Altier C. 2004. Trends in antimicrobial resistance, phage types and integrons among Salmonella serotypes from pigs, 1997–2000. J Antimicrob Chemother 53:997–1003. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkh247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mølbak K. 2005. Human health consequences of antimicrobial drug-resistant Salmonella and other foodborne pathogens. Clin Infect Dis 41:1613–1620. doi: 10.1086/497599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Varma JK, Greene KD, Ovitt J, Barrett TJ, Medalla F, Angulo FJ. 2005. Hospitalization and antimicrobial resistance in Salmonella outbreaks, 1984–2002. Emerg Infect Dis 11:943–946. doi: 10.3201/eid1106.041231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Helms M, Vastrup P, Gerner-Smidt P, Mølbak K. 2002. Excess mortality associated with antimicrobial drug-resistant Salmonella typhimurium. Emerg Infect Dis 8:490–495. doi: 10.3201/eid0805.010267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Irazoki O, Aranda J, Zimmermann T, Campoy S, Barbé J. 2016. Molecular interaction and cellular location of RecA and CheW proteins in Salmonella enterica during SOS response and their implication in swarming. Front Microbiol 7:1560. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Irazoki O, Mayola A, Campoy S, Barbé J. 2016. SOS system induction inhibits the assembly of chemoreceptor signaling clusters in Salmonella enterica. PLoS One 11:e0146685. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0146685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chopra I, Roberts M. 2001. Tetracycline antibiotics: mode of action, applications, molecular biology, and epidemiology of bacterial resistance. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 65:232–260. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.65.2.232-260.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schwarz S, Kehrenberg C, Doublet B, Cloeckaert A. 2004. Molecular basis of bacterial resistance to chloramphenicol and florfenicol. FEMS Microbiol Rev 28:519–542. doi: 10.1016/j.femsre.2004.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ramirez MS, Tolmasky ME. 2010. Aminoglycoside modifying enzymes. Drug Resist Updat 13:151–171. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2010.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Houry A, Gohar M, Deschamps J, Tischenko E, Aymerich S, Gruss A, Briandet R. 2012. Bacterial swimmers that infiltrate and take over the biofilm matrix. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109:13088–13093. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200791109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Duan Q, Zhou M, Zhu L, Zhu G. 2013. Flagella and bacterial pathogenicity. J Basic Microbiol 53:1–8. doi: 10.1002/jobm.201100335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alcalde-Rico M, Hernando-Amado S, Blanco P, Martínez JL. 2016. Multidrug efflux pumps at the crossroad between antibiotic resistance and bacterial virulence. Front Microbiol 7:1483. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boyd EF, Wang FS, Beltran P, Plock SA, Nelson K, Selander RK. 1993. Salmonella reference collection B (SARB): strains of 37 serovars of subspecies I. J Gen Microbiol 139:1125–1132. doi: 10.1099/00221287-139-6-1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wozniak CE, Chevance FF, Hughes KT. 2010. Multiple promoters contribute to swarming and the coordination of transcription with flagellar assembly in Salmonella. J Bacteriol 192:4752–4762. doi: 10.1128/JB.00093-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bearson BL, Bearson SM. 2008. The role of the QseC quorum-sensing sensor kinase in colonization and norepinephrine-enhanced motility of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Microb Pathog 44:271–278. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Doublet B, Douard G, Targant H, Meunier D, Madec JY, Cloeckaert A. 2008. Antibiotic marker modifications of lambda red and FLP helper plasmids, pKD46 and pCP20, for inactivation of chromosomal genes using PCR products in multidrug-resistant strains. J Microbiol Methods 75:359–361. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2008.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bearson BL, Bearson SM, Uthe JJ, Dowd SE, Houghton JO, Lee I, Toscano MJ, Lay DC Jr. 2008. Iron regulated genes of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium in response to norepinephrine and the requirement of fepDGC for norepinephrine-enhanced growth. Microbes Infect 10:807–816. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2008.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chang AC, Cohen SN. 1978. Construction and characterization of amplifiable multicopy DNA cloning vehicles derived from the P15A cryptic miniplasmid. J Bacteriol 134:1141–1156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bearson BL, Allen HK, Brunelle BW, Lee IS, Casjens SR, Stanton TB. 2014. The agricultural antibiotic carbadox induces phage-mediated gene transfer in Salmonella. Front Microbiol 5:52. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]