Abstract

The basic region/leucine zipper motif (bZIP) transcription factor family is one of the largest families of transcriptional regulators in plants. bZIP genes have been systematically characterized in some plants, but not in rapeseed (Brassica napus). In this study, we identified 247 BnbZIP genes in the rapeseed genome, which we classified into 10 subfamilies based on phylogenetic analysis of their deduced protein sequences. The BnbZIP genes were grouped into functional clades with Arabidopsis genes with similar putative functions, indicating functional conservation. Genome mapping analysis revealed that the BnbZIPs are distributed unevenly across all 19 chromosomes, and that some of these genes arose through whole-genome duplication and dispersed duplication events. All expression profiles of 247 bZIP genes were extracted from RNA-sequencing data obtained from 17 different B. napus ZS11 tissues with 42 various developmental stages. These genes exhibited different expression patterns in various tissues, revealing that these genes are differentially regulated. Our results provide a valuable foundation for functional dissection of the different BnbZIP homologs in B. napus and its parental lines and for molecular breeding studies of bZIP genes in B. napus.

Keywords: Brassica napus, bZIP transcription factors, expression patterns, phylogenetic analysis

1. Introduction

The basic leucine zipper (bZIP) family, one of the largest transcription factor (TF) families in plants, is widely distributed in eukaryotes [1]. The bZIP TFs play a crucial role in various biological processes in plants, including signal transduction, stress responses, and growth and development [2]. During these processes, the expression of bZIP TF genes is primarily induced by abscisic acid (ABA), an important phytohormone that functions in the abiotic stress response that regulates the expression of numerous genes and associated physiological processes [3]. The Arabidopsis thaliana genome encodes 13 bZIP TFs in the A subfamily, including ABI5 (ABA Insensitive 5) and ABFs (ABA-responsive Element Binding Factors), also known as AREBs (ABA-responsive Element Binding Proteins), which play pivotal roles in activating plant ABA signaling [4,5,6,7]. In addition, bZIP TFs are crucial regulators of drought, high salinity, and cold stress responses in many plants, including Arabidopsis [8], Oryza sativa (rice) [9], Triticum aestivum (wheat) [10], Solanum lycopersicum (tomato) [11,12], Glycine max (soybean) [13], and Capsicum annuum (pepper) [14]. Many bZIP TFs also play a crucial role in plant growth and developmental processes, including organ and tissue differentiation [15], cell elongation [16,17], nitrogen/carbon and energy metabolism [18,19,20], the unfolded protein response (UPR) [21,22], seed storage protein gene regulation [23], and somatic embryogenesis [24]. Therefore, bZIP TFs play a crucial role in protecting plants from all types of biological and abiotic stresses.

Brassica napus (AACC, 2n = 38), one of the most important oilseed crops worldwide, originated from hybridization between Brassica rapa (AA, 2n = 20) and Brassica oleracea (CC, 2n = 18), which have a common ancestor [25]. At the most recent, moreover, they have experienced α and β duplication events, and then they have two triplication events during the specific to Brassica clade during the evolutionary process [26]. For these whole-genome duplication (WGD) events, along with the merger of the two progenitor genomes, have resulted in a large number of gene duplications in the B. napus genome, followed by substantial gene loss [27]. Further, the A/C genomic sequences of B. napus had a good collinearity with the A and C genomes of B. rapa and B. oleracea with three sub-genomes showing different levels of fractionation (least fractionized subgenome (LF), moderately fractionized gennome (MF1), and most fractionized genome (MF2)), which were also extrapolated to the B. napus genome [25]. Thus, Brassica is regarded as an ideal model for investigating polyploidy evolution [25]. To date, many bZIP TF genes have been identified and characterized extensively in various plants, including Arabidopsis [7], rice [1], sorghum [28], Zea mays (maize) [2], Vitis vinifera (grapevine) [29], Cucumis sativus (cucumber) [30], Ricinus communis (castor bean) [31], and Hordeum vulgare (barley) [32], for which whole genome sequences are available. However, genome-wide surveys and expression analyses of this gene family have not been performed in B. napus.

In this study, we screened the draft sequence of the B. napus genome (http://www.genoscope.cns.fr/brassicanapus/) for bZIP TF genes. We identified 247 BnbZIP genes and performed a detailed analysis of their duplication and classification, chromosome distribution, and motifs, as well as phylogenetic analysis. Finally, we verified the differential expression profiles of selected BnbZIP genes in 17 different B. napus tissues at various developmental stages. This study provides important information about the origin and evolution of the bZIP family in B. napus, and lays the foundation for further studies of the functions of the bZIP family in this important crop.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Identification of bZIP Family Genes in Brassica napus

Based on the protein sequences of the bZIP family from the The Arabidopsis Information Resource (TAIR) database (ftp://ftp.arabidopsis.org), 247 B. napus bZIP protein sequences were obtained as query sequences through BLASTp searching [33] against the B. napus genome database. The candidate sequences were chosen based on an E-value of ≤1 × 10−20. The candidate sequences were further confirmed using the HMMsearch program (HMMER 3.0, http://hmmer.janelia.org/), and BLAST analysis of the bZIP sequences in the B. napus genome database was performed using Geneious 4.8.5 software (http://www.geneious.com/; Biomatters, Auckland, New Zealand). The candidate genes were named using two-letter abbreviations (italicized) denoting the source organism, the family name, and the positions in the subtribe, e.g., BnbZIP1a. The lengths of the coding sequences (CDSs) were identified by performing BLASTn searches against the B. napus genome database. The physicochemical properties of the deduced proteins, including the molecular weight (MW), isoelectric point (pI), and grand average of hydropathy (GRAVY) value were determined using the ExPASy-ProtParam tool (http://web.expasy.org/protparam/).

2.2. Multiple Sequence Alignment and Phylogenetic Analysis of the bZIP Family Members in Brassica napus

Arabidopsis contains 75 putative bZIP genes [7]. The 73 authenticated Arabidopsis AtbZIP genes were used for multiple protein sequence alignments using ClustalW2 software with default settings (AT2G12980 [AtbZIP32] and AT2G13130 [AtbZIP73] are not available) [34]. The phylogenetic trees were constructed using Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) 6.0 with the neighbor-joining (NJ) method, the JTT+I+G substitution model with 1000 bootstrap replicates [35]. The phylogenetic trees were visualized using FigTree v1.4.2 (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/).

2.3. Analysis of Exon-Intron Structures and Conserved Motifs in BnbZIP Genes

The DNA and complementary DNA (cDNA) sequences of the putative bZIP genes were downloaded from the B. napus genome database, and the exon-intron compositions of the BnbZIP genes were analyzed using Gene Structure Display Server (GSDS) (http://gsds.cbi.pku.edu.cn/index.php). The conserved motifs of BnbZIP family members were determined using Multiple Em for Motif Elicitation (MEME) 4.11.4 (http://meme-suite.org/tools/meme), with the following parameters: number of repetitions, any; maximum number of motifs, 15; and optimum width of each motif, between 6 and 300 residues [36]. Only genes with an E-value of <1 × 10−20 were subjected to further analysis.

2.4. Chromosomal Distribution of BnbZIP Genes in Brassica napus

The detailed chromosomal locations of each BnbZIP gene were mapped to the B. napus chromosomes according to the GFF genome files downloaded from the B. napus genome database. The physical chromosome maps were drafted with MapChart 2.0 [37], and the BnbZIP genes were graphically displayed on the B. napus chromosomes.

2.5. Analysis of BnbZIP Gene Expression Patterns

Transcriptome sequencing datasets were deposited in the BioProject ID PRJNA358784, which were sequenced by RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) from 17 B. napus cultivar Zhongshuang No. 11 (ZS11) tissues (roots, stems, leaves, buds, anthocaulus, sepal, petal, pistils, stamens, anthers, filaments, the top of main inflorescence flowers, seeds, embryos, seedcoat, funiculus, and silique pods) at different developmental stages. Total RNA was isolated using an RNAprep Pure Plant Kit (Tiangen Biotech, Beijing, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA-seq library construction and data analysis were performed as described [38]. All BnbZIP genes expression levels were quantified in terms of FPKM (fragments per kilobase of exon per million mapped fragments) using Cufflinks with default parameters [39], and then extracted from RNA-seq results according to their B. napus code. The heatmaps for the BnbZIP genes were drafted using HemI 1.0 software [40].

2.6. Quantitative Real Time PCR Validation of Transcriptome Data

To confirm the RNA-seq data and to characterize the expression patterns of BnbZIP genes involved in B. napus development, the expression profiles of 13 genes in different ZS11 tissues and different subfamilies (as determined in this study) were evaluated by quantitavite real time PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis. The cDNA was synthesized with the Oligo dT-Adaptor Primer, using an RNA PCR Kit (AMV) Ver. 3.0 (TaKaRa, Dalian, China). qRT-PCR analysis was performed on a Bio-Rad CFX96 Real Time System (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) with the following cycling conditions: pre-incubation at 95 °C for 2 min followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 10 s, annealing at 60 °C for 20 s, and melting curve analysis [38]. BnACTIN7 (EV116054) and BnUBC21 (EV086936) were used as internal controls to evaluate relative gene expression levels [41]. Target genes and internal controls were amplified in single wells in triplicate, and the expression levels were calculated by the 2−ΔΔCt method. The values represent the average ± standard deviation (SD) from three independent biological replicates. All the primers were listed in the Supplementary Materials Table S1.

3. Results

3.1. Identification of bZIP Family Members in Brassica napus

In the model plant Arabidopsis, 75 bZIP members have been identified [7], however, the sequences of AtbZIP32 and AtbZIP73 were not accurately identification in the Arabidopsis genome database. To perform genome-wide identification of bZIP proteins in B. napus, therefore, we used BLAST and the Hidden Markov Model (HMM) profiles of the bZIP domain to screen the B. napus genome database. We identified 247 proteins with bZIP domains in the B. napus genome. A subset of the genes encoding these proteins are homologous to 67 of the 73 Arabidopsis bZIP TF genes, except for AtbZIP6, AtbZIP31, AtbZIP33, AtbZIP43, AtbZIP71, and AtbZIP74. We named these genes BnbZIP1 to BnbZIP75, corresponding to the respective Arabidopsis genes (Figure 1, Table S2). In addition, 2–8 copy members were identified from 67 BnbZIPs, respectively (Table S2). For example, twenty BnbZIP genes only contains two members, BnbZIP3 have 8 members, and fewer than 7 members of the other BnbZIP families were identified (Table S2). These results are consistent with the finding that excessive gene loss typically occurs after polyploidization in eukaryotes [42,43]. These bZIP TF genes encode proteins with deduced amino acid sequences ranging from 82 (BnbZIP16f) to 729 (BnbZIP1c) amino acids in length, with molecular weights of 8.79 kDa (BnbZIP16f) to 79.69 kDa (BnbZIP1c). The isoelectric points of these proteins were predicted to range from 4.74 (BnbZIP60b) to 10.35 (BnbZIP14c). The GRAVY values for all 247 BnbZIP proteins were found to be negative, indicating that they are hydrophilic, which is essential for the functioning of TFs. The gene names and related information are presented in Table S2.

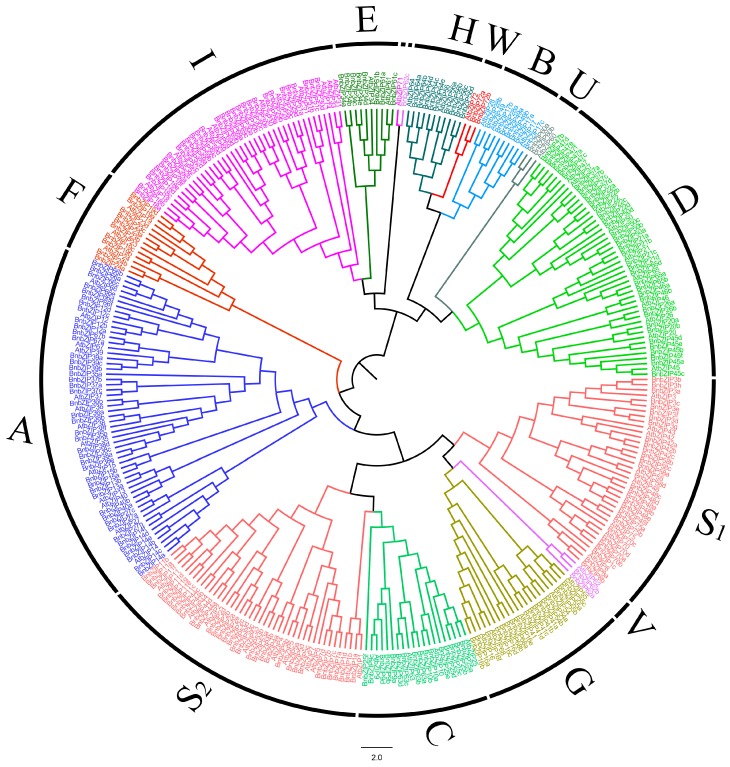

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic analysis of the B. napus and Arabidopsis bZIP proteins. The protein sequences from 247 bZIPs from Brassica napus and 73 bZIPs from Arabidopsis were aligned using ClustalW. The phylogenetic tree was constructed with MEGA 6.0 using the neighbor-joining (NJ) method with 1000 bootstrap replicates. All bZIP TFs were divided into 13 subfamilies, A–I and S–W. The subgroups A-I and S were named according to Jakoby et al. [7], and U, V, and W were the new subgroups, with similar to AtbZIP60, AtbZIP62, and AtbZIP72, respectively.

3.2. Phylogenetic Analysis of the bZIP TFs in Brassica napus

The 75 bZIP TFs identified in Arabidopsis were classified into 10 groups, of which one group contains three bZIP TFs (AtbZIP60, AtbZIP62, and AtbZIP72) [7]. To explore the evolutionary relationships between bZIP TFs from A. thaliana and B. napus, we performed a phylogenetic analysis of the 247 BnbZIP TF protein sequences identified in B. napus. All 247 BnbZIP TFs were classified into 10 groups (Figure 1), which we named A–I and S, as in Arabidopsis, and the genes with high levels of sequence similarity to AtbZIP60, AtbZIP62, and AtbZIP72 were named U, V, and W, respectively. Group S, the largest group, includes 63 BnbZIPs, which were further divided into two subgroups (Group S1 and S2). However, the AtbZIP1-containing clade were grouped as part of C-Group (Figure 1), which were different with the previous research [7]. Groups A and D contain 43 and 37 members, respectively. Group I contains 30 members. Groups C and G contain 16 and 17 members, respectively. Groups B and H contain 7 and 9 members, respectively, and Groups U and W each contain 2 members. Finally, Groups E, F, and V include 8, 10, and 3 BnbZIPs, respectively. However, Groups C, G, and V are contained within Group S, and AtbZIP71 and BnbZIP62c were classified in the same subgroup (Figure 1). These results indicate that the conserved areas have been preserved of these genes share similar evolutionary relationships during evolution between Arabidopsis and B. napus, but several variations have also occurred, enabling the division of some genes into subfamilies, e.g., AtbZIP1, BnbZIP1a, BnbZIP1b, BnbZIP1d, AtbZIP71, and BnbZIP62c (Figure 1).

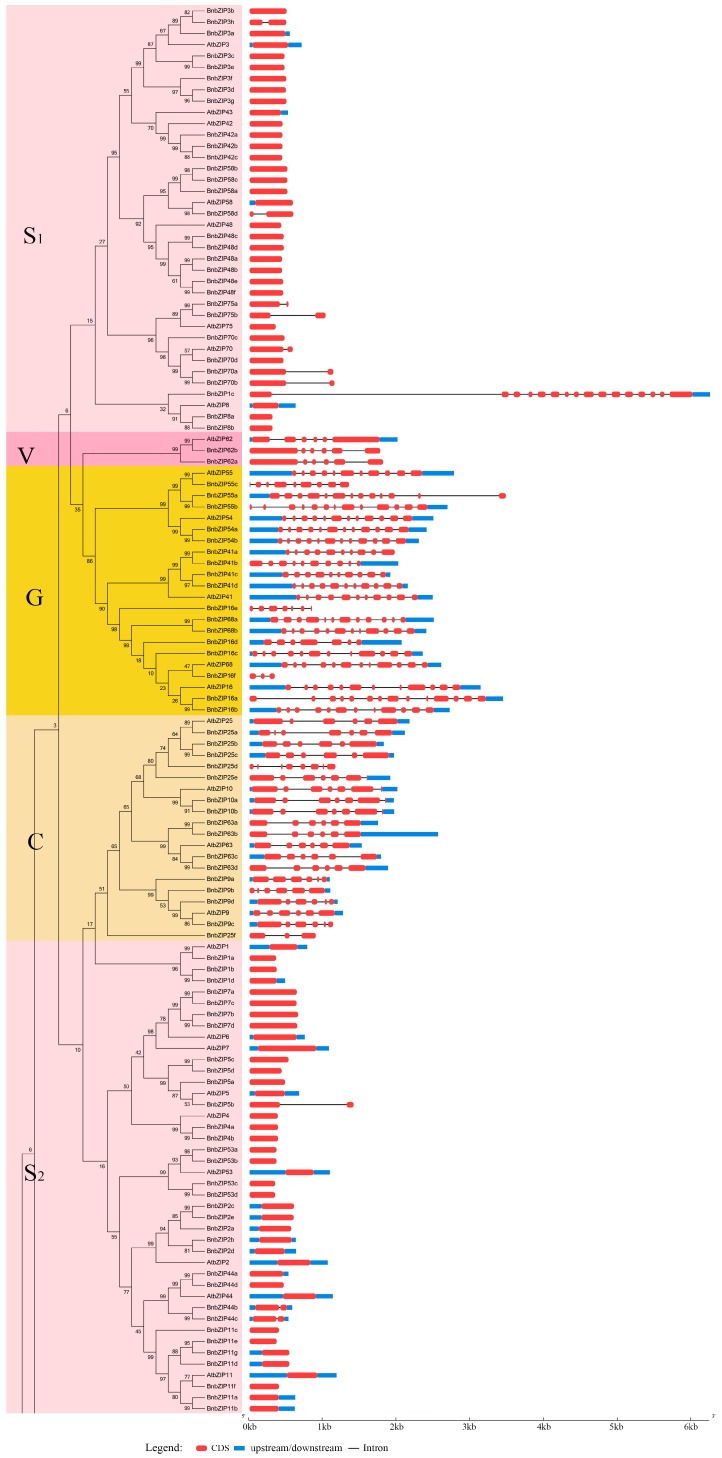

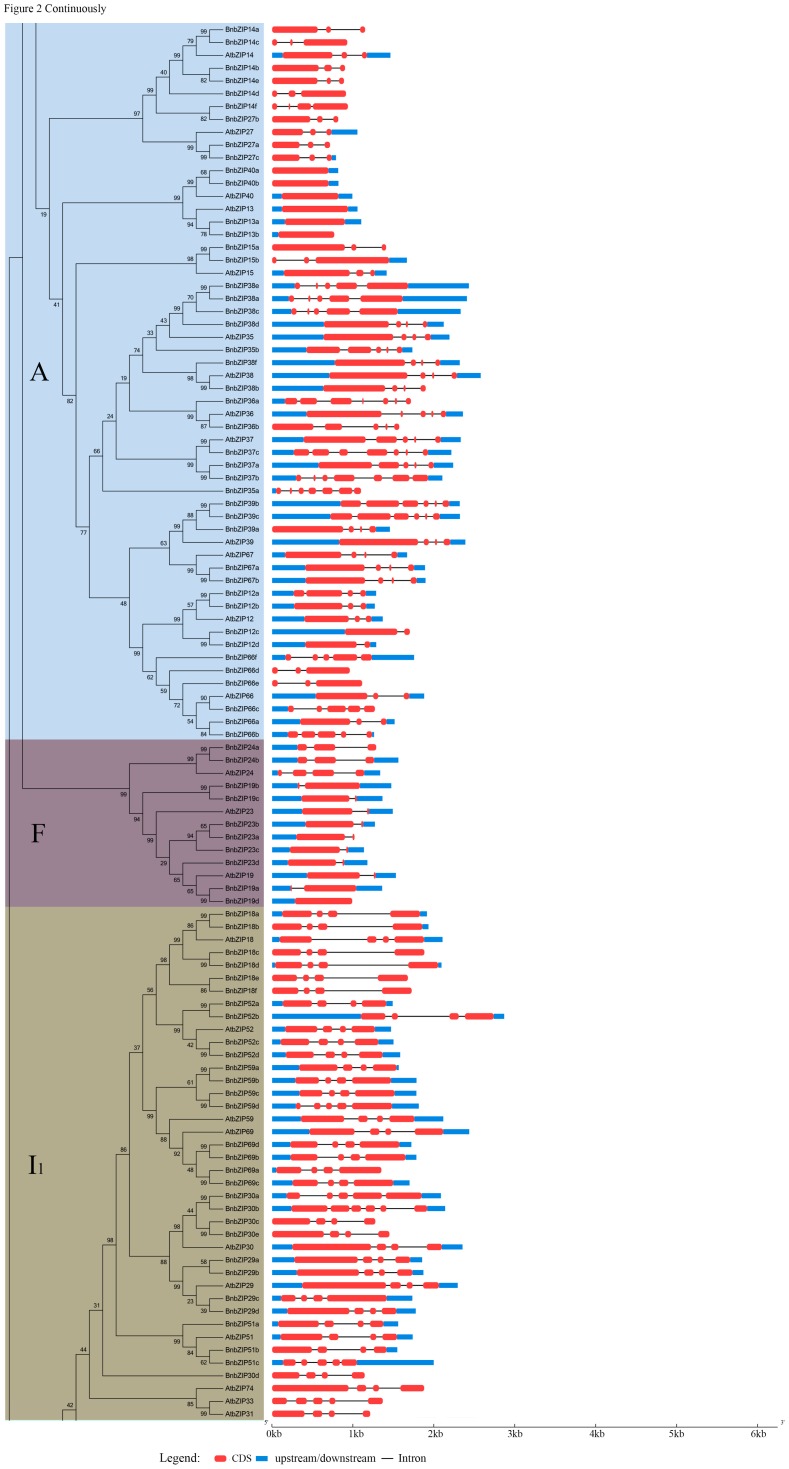

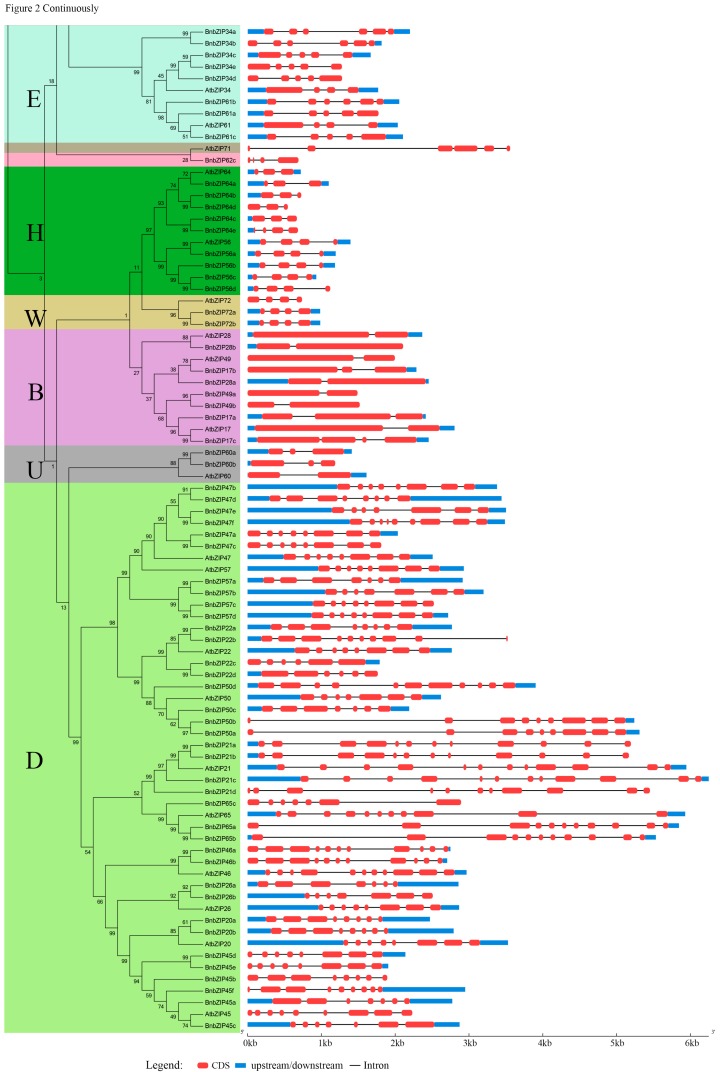

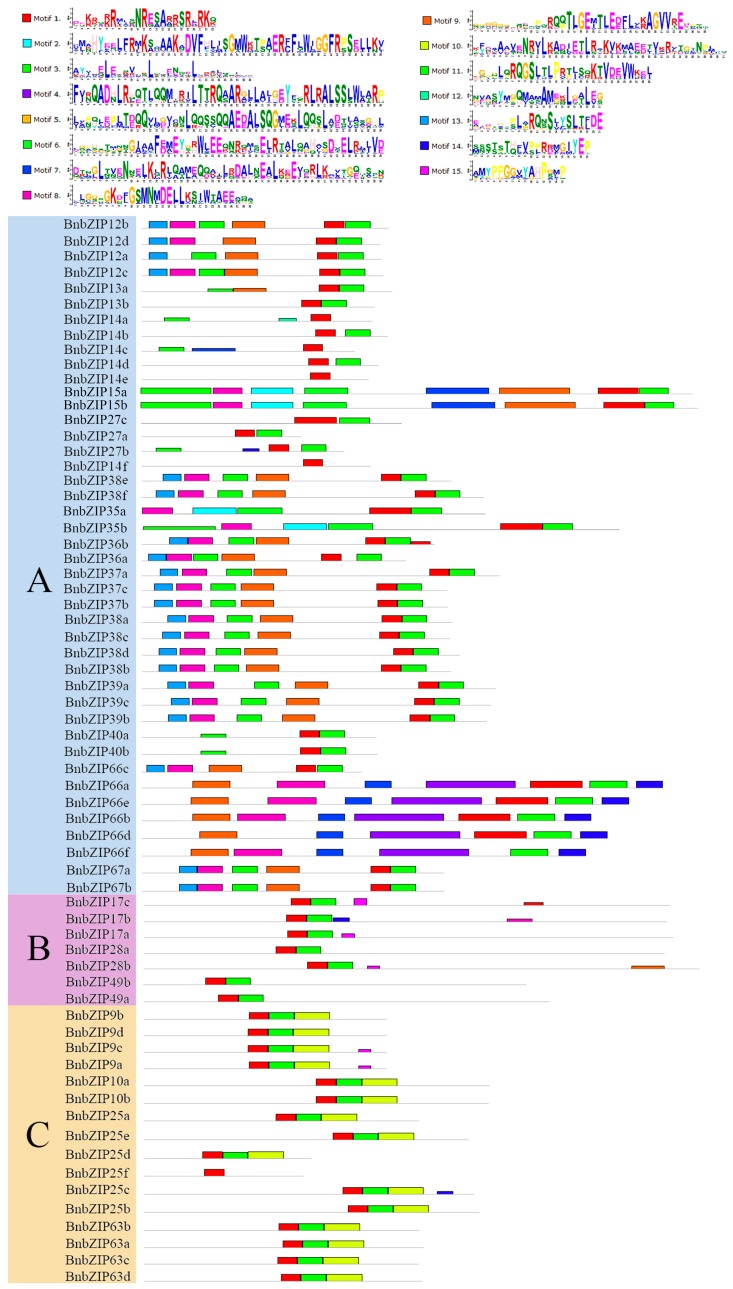

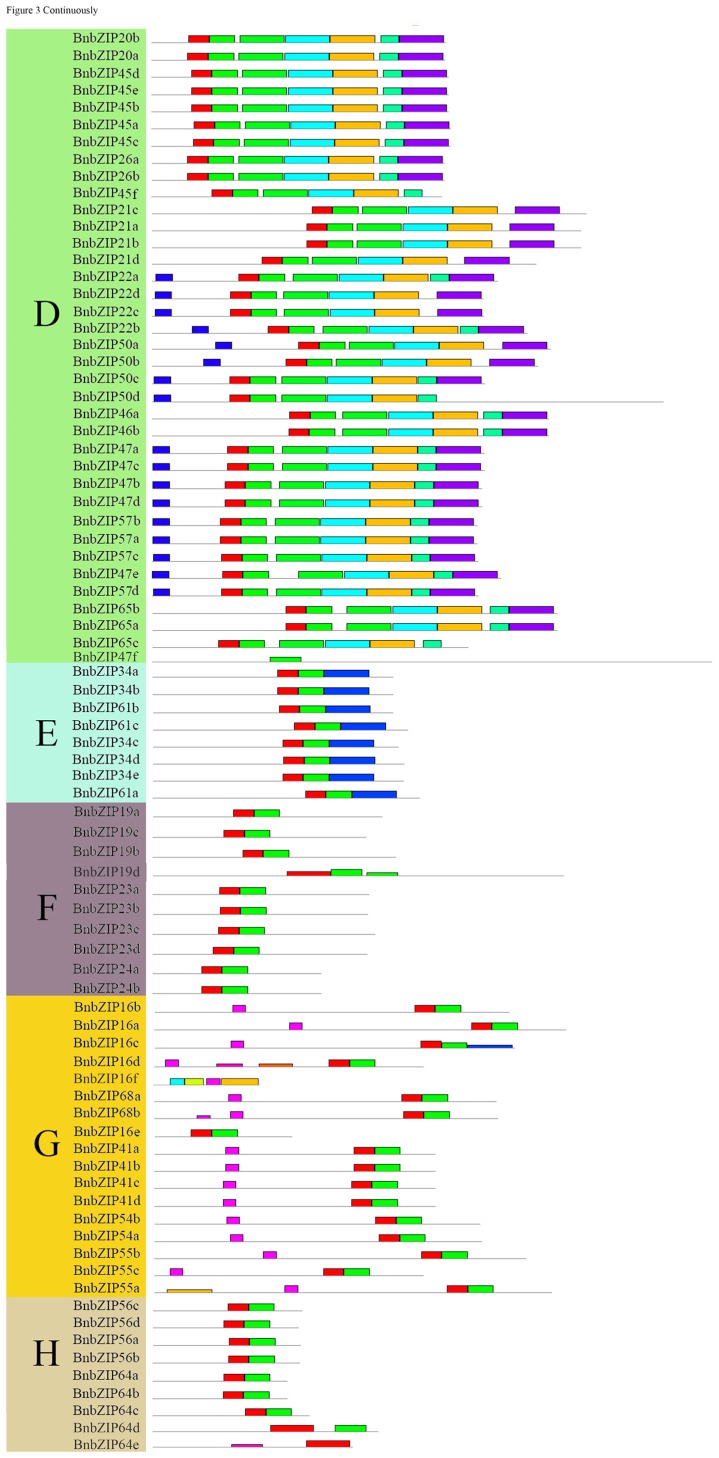

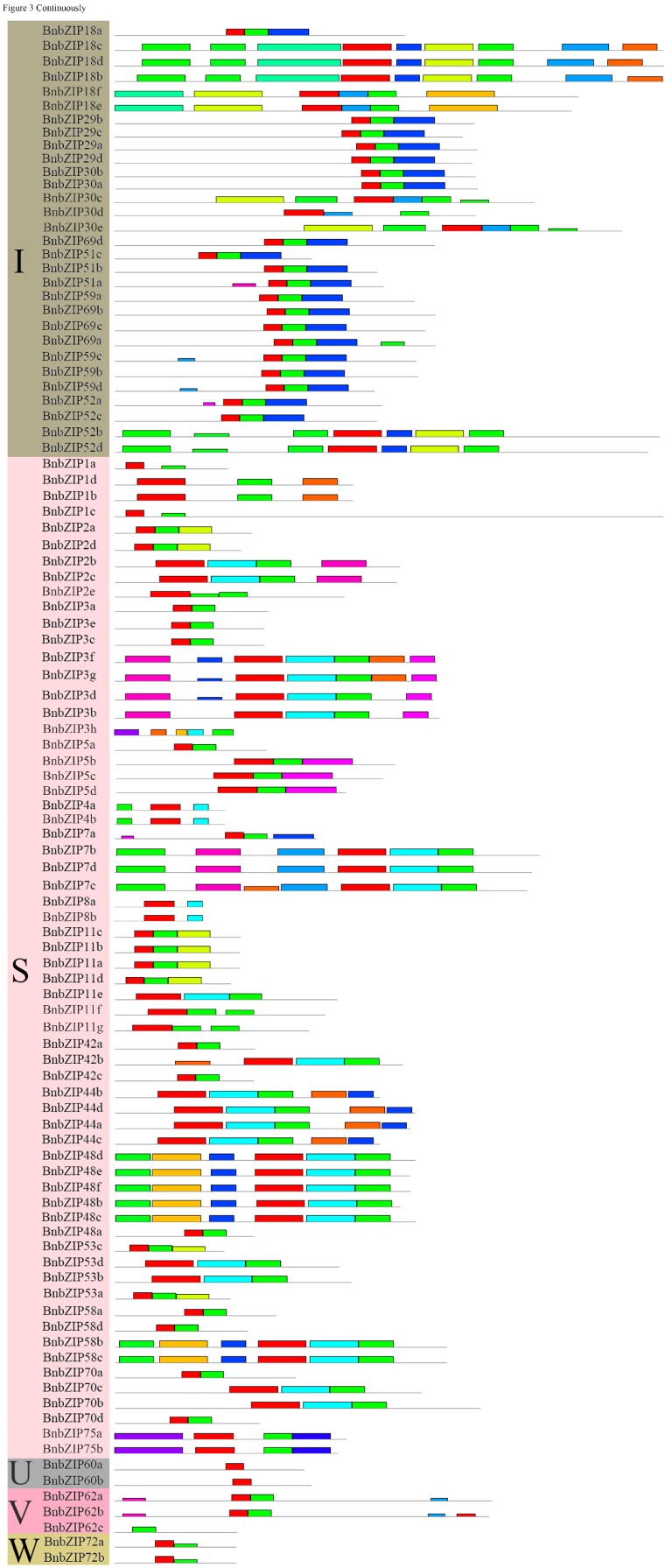

3.3. Gene Structure and Motif Analyses of BnbZIPs

To explore the structural diversity of the BnbZIP genes, we analyzed their intron-exon structures using GSDS. The number of exons varies from 1 to 16, indicating a high degree of divergence among the 247 BnbZIP genes (Figure 2, Table S2). However, the exon-intron structures of the genes are more highly conserved within a single subgroup. For example, most genes with uninterrupted open reading frames (ORFs) are found in Group S (Figure 2, Table S2). However, among the genes in Group S, BnbZIP1c has 16 exons, while BnbZIP3h, BnbZIP5b, BnbZIP75a, BnbZIP75b, BnbZIP44b, BnbZIP44c, BnbZIP58d, BnbZIP70a, and BnbZIP70b each have two exons (Figure 2, Table S2). Additionally, genes in Group D and G have 5–11 and 2–13 introns, respectively, indicating that some subgroups are highly divergent. We also identified highly paralogous pairs among the BnbZIP genes with relatively high bootstrap support (>99%), such as BnbZIP41c–BnbZIP41d, BnbZIP16a–BnbZIP16b, BnbZIP27a–BnbZIP27c, BnbZIP12a–BnbZIP12b, BnbZIP22a–BnbZIP22b, BnbZIP30a–BnbZIP30b, and BnbZIP69a–BnbZIP69c.

Figure 2.

Sequences analysis of exon-intron structures of the BnbZIP genes. The red boxes indicate exons. Solid lines indicate introns (connecting two exons). Untranslated regions (UTRs) are indicated by blue boxes. The length of BnbZIP genes were indicated by horizontal axis (kb).

As shown in Figure 3, one or more identical motifs (motif 1–9) are shared among members of the same family, with major differences detected among groups. For example, motif 1 and motif 3 are widely present in all BnbZIP members; motif 1 encodes the conserved bZIP domain, with a basic region of 16 amino acid residues containing a nuclear localization signal followed by an invariant N-x7-R/K motif [7], which binds to the DNA (Figure 3). We detected widespread variation in the motif pattern among Groups A, D, I and S; for instance, motif 2 was found in Groups A, D, G and S; motif 4 and 5 were found only in Groups I and D; motif 7 was found in Groups D, E, and I; motif 8 was found in Groups A and S; and motif 9 was found in Group A (Figure 3). These results showed that the composition of the structural motifs varies among different bZIP families but is similar within the same families, and that the motifs encoding the bZIP domains are conserved.

Figure 3.

Motif patterns and WebLogo plots of the different BnbZIP subfamilies. The 247 B. napus BnbZIP amino acid sequences were aligned (Figure S1). The motifs are indicated by different colored boxes (numbered Motif 1–15).

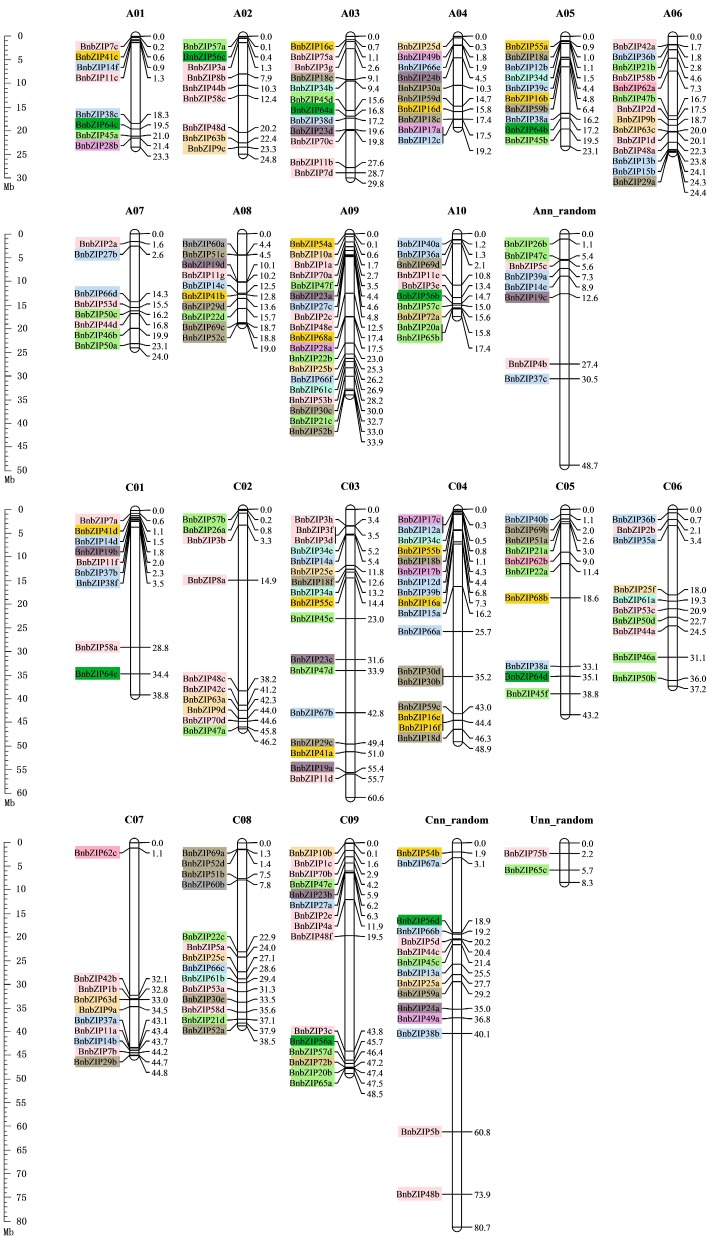

3.4. Genomic Distribution of the 247 BnbZIPs on the 19 Brassica napus Chromosomes

Based on the physical positions of the BnbZIP genes annotated in GFF files, 222 BnbZIP members could be accurately mapped onto the 19 B. napus chromosomes, whereas the others were located on the unmapped scaffolds in the B. napus genome (Figure 4). Furthermore, all BnbZIP members varies considerably among the B. napus chromosomes, with chromosomes harboring from 8 (A01 and A07) to 19 (A09) of these genes (Figure 4, Table S2). BnbZIP genes are mainly localized on chromosomes A06, A09, C03, C04, C08, and C09, which contain 14, 19, 17, 17, 14, and 15 BnbZIP genes, respectively (Figure 4, Table S2). In addition, many BnbZIP genes are distributed near the ends of chromosomes. We detected 15 tandemly duplicated genes (with two or more homologous genes ≤100 kb apart) on eight chromosomes (A04, A05, A08, A09, A10, C03, C04, and C09). Three of the 13 subclusters, including Groups A, D, and S, are widely distributed throughout the B. napus genome (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Distribution of BnbZIP gene family members on the B. napus chromosomes. The 222 BnbZIP genes for which exact chromosomal information is available in the database were mapped to the 19 B. napus chromosomes. Genes from the same subtribe are indicated by the same color, which is consistent with the corresponding family in the evolutionary tree. The scales were indicated the genome size of B. napus genome (Mb). A01-A10 and C01-C09 indicate the chromosomes of B. napus. Ann_random: unmapped A Chromosomes of B. napus genome; Cnn_random: unmapped C Chromosomes of B. napus genome; Unn_random: unmapped Chromosomes of B. napus genome.

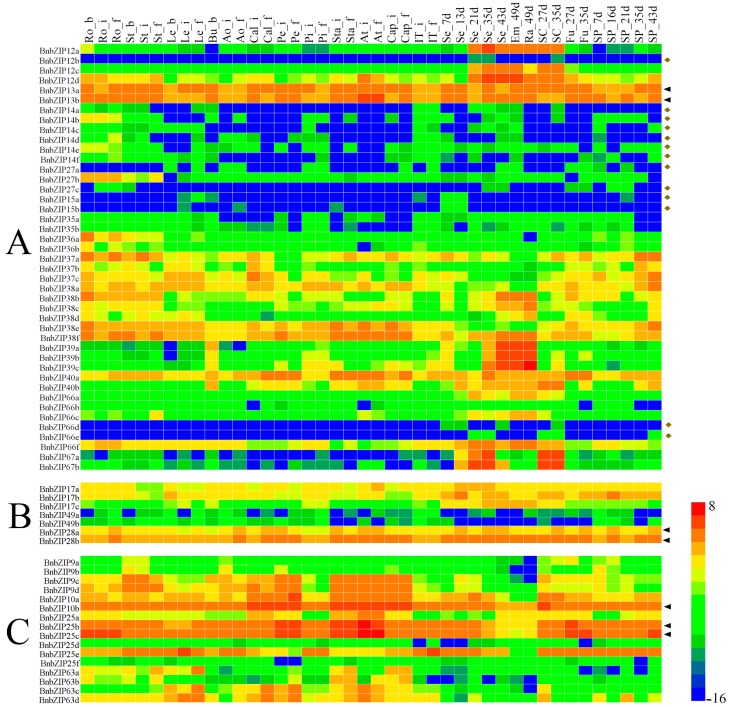

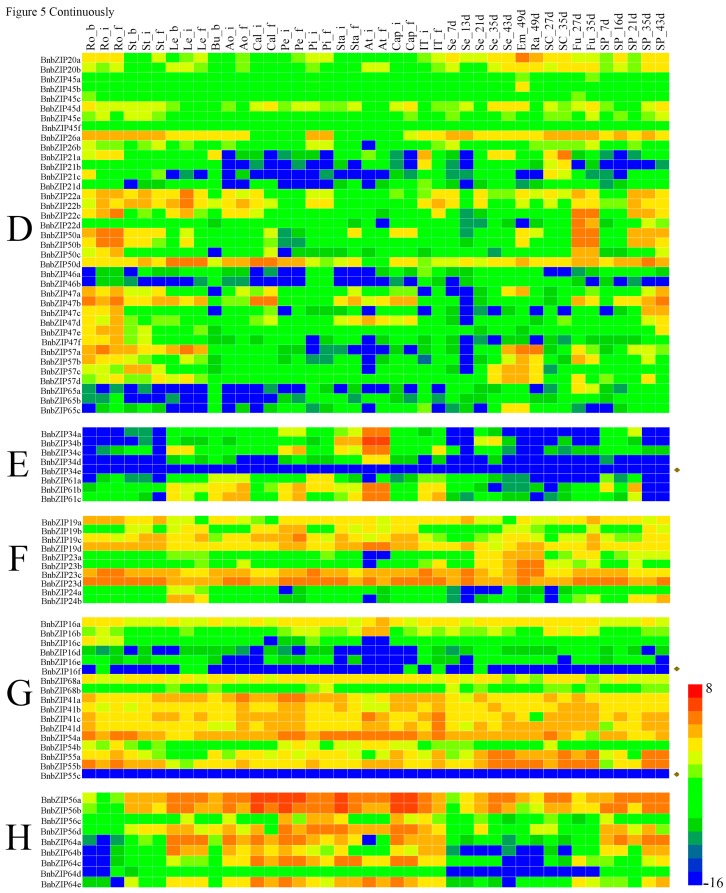

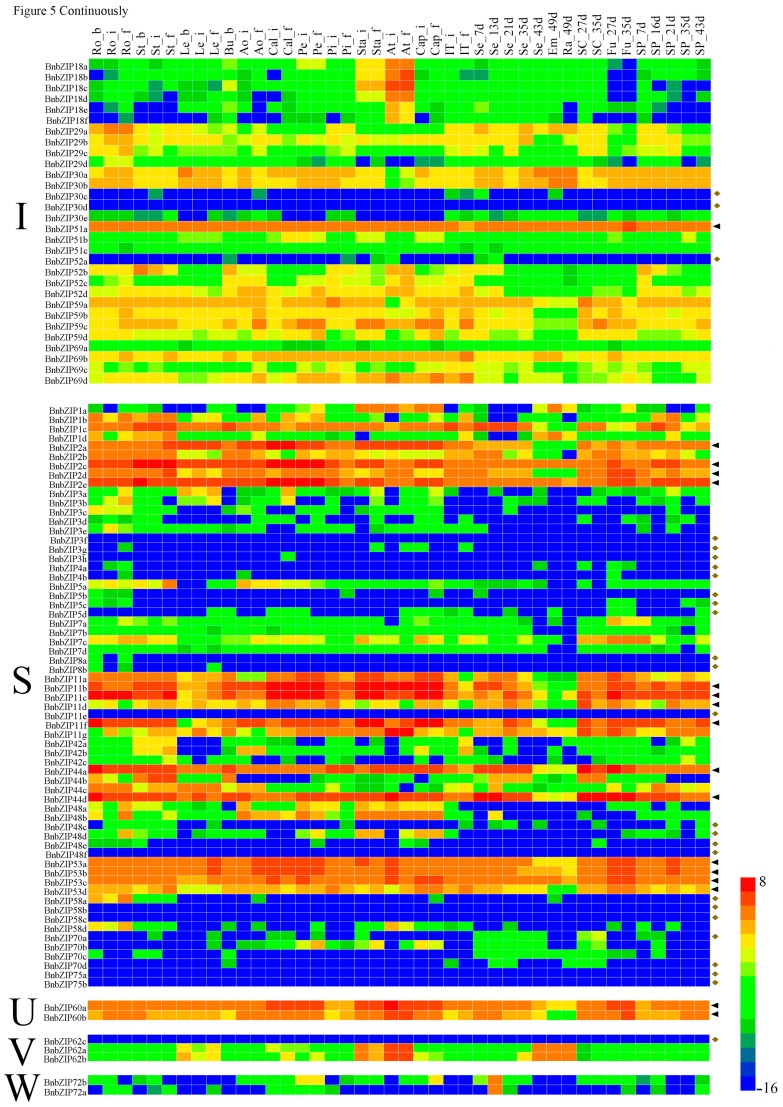

3.5. The Differential Expression Analyses of the BnbZIP Genes in Various Tissues of Brassica napus

We investigated the expression profiles of the 247 BnbZIP TF genes in different tissues at various stages of development based on RNA-seq datasets from B. napus ZS11. In this study, we generated high-quality transcriptome sequencing datasets (BioProject ID PRJNA358784) from 17 B. napus ZS11 tissues at different developmental stages, e.g., roots, hypocotyls, cotyledons, stems, leaves, buds, flowers, and seeds (Table S3). We then calculated the relative expression levels of the 247 BnbZIP genes based on the RNA-seq data, which we used to construct a heatmap. In the present study, the results showed that the expression profiles of BnbZIP genes were associated with different tissues, and the expression patterns also differed among each bZIP gene family (Figure 5). For example, genes in the largest Groups, A, D, and S, had significantly different expression levels in all tissues and organs. Most BnbZIP genes in Groups C, F, G, H, and U were highly expressed in all tissues and organs, whereas most genes in Groups E, V, and W were expressed at low levels or were not expressed in the tissues examined (Figure 5, Table S4). Among the 247 bZIP genes, 22 were highly expressed in all tissues, including BnbZIP13, BnbZIP28, BnbZIP41, BnbZIP2, BnbZIP53, and BnbZIP60. Conversely, 42 BnbZIP genes were not expressed or were expressed at low levels in all tissues. For example, BnbZIP14, BnbZIP15, BnbZIP66, BnbZIP3, BnbZIP4, BnbZIP5, BnbZIP8, BnbZIP58, BnbZIP70, BnbZIP75, and BnbZIP72 were expressed at low levels in all tissues, and BnbZIP34c, BnbZIP55c, BnbZIP30d, BnbZIP3f, BnbZIP11e, BnbZIP48f, BnbZIP58b, BnbZIP58c, BnbZIP75a, BnbZIP75b, and BnbZIP62c exhibited little or no expression in any tissue (Figure 5, Table S4). Furthermore, duplicate copies of some gene pairs showed opposite expression patterns in different tissues, such as BnbZIP55, BnbZIP30, and BnbZIP11 (Figure 5, Table S4).

Figure 5.

Heatmap of the expression levels of B. napus bZIP transcription factor family genes during different periods of development in different tissues and organs. Each subfamily is represented by a different uppercase letter (A–I, S, U–W). The black triangles correspond to higher expression levels in all tissues during the whole development, and the yellow diamonds correspond to lower expression levels in all tissues during the whole development. The abbreviations combinations above the heatmap indicate the different tissues and organs/developmental stages from B. napus ZS11 (listed in Table S3). The “scale” function in R was used to normalize relative expression levels (R = log2/FPKM). The heatmap was generated using Heatmap Illustrator (HemI) [40].

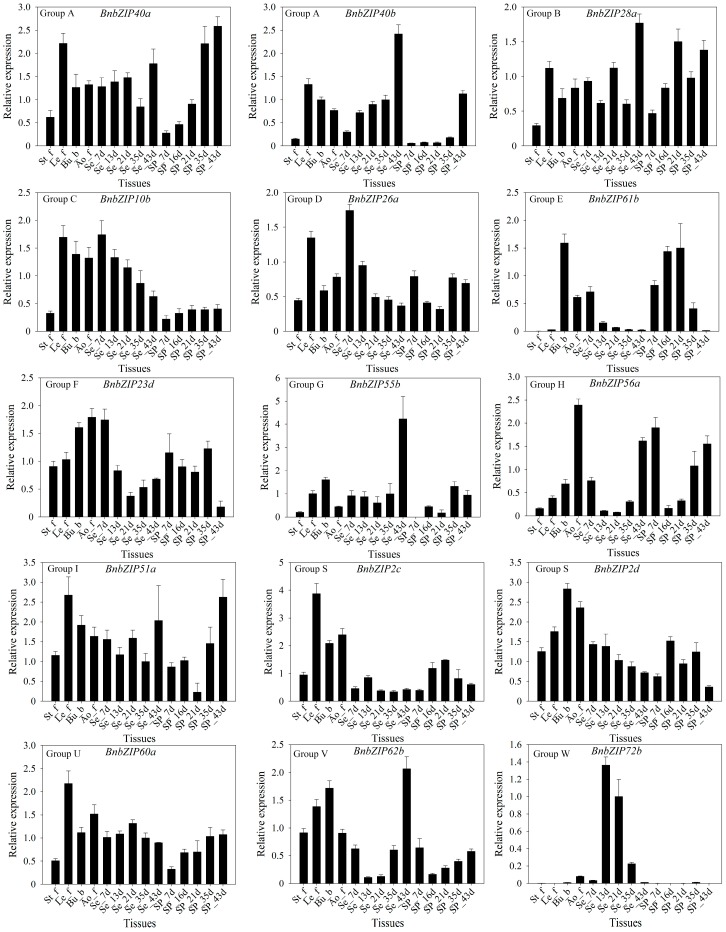

We performed qRT-PCR to confirm the expression patterns of differentially expressed genes identified in our transcriptomic analysis. We investigated the expression patterns of 13 bZIP genes from different subgroups in 14 tissues and organs of ZS11 (Figure 5 and Figure 6). The expression patterns from RNA-seq and qRT-PCR were highly similar, and highly correlated (r = 0.58–0.88; Pearson test, p ≤ 0.05), confirming the reproducibility and reliability of the transcriptome data obtained in this study.

Figure 6.

The expression levels of B. napus bZIP transcription factor family genes at different developmental stages in different tissues and organs, as determined by quantitative real time PCR (qRT-PCR). The subfamily is indicated in the upper-left corner of each graph. The x axis corresponds to the different tissues and organs/developmental stages of B. napus ZS11 (listed in Table S3). BnACTIN7 (EV116054) and BnUBC21 (EV086936) were used as the reference gene [41]. Values represent the average ± standard deviation (SD) of three biological replicates with three technical replicates at each developmental stage. Error bars denote SD among three experiments.

4. Discussion

4.1. Characterization of bZIP Gene Families in Brassica napus

In this study, 247 BnbZIP TF family members were predicted to be present in the B. napus genome database. bZIP TF genes have been extensively characterized in other plants, including 75 bZIP genes in Arabidopsis, 89 in rice, 92 in Sorghum, 125 members in maize, and 64 in cucumber [29,30,44]. Compared with these plants, B. napus contains many more bZIP genes, which is not surprising, since B. napus is an allotetraploid with a complex genome with the larger assembled genome size than that of B. oleracea (540 Mb) and B. rapa (312 Mb) [25]. In this study, we identified 247 bZIP genes in 67 gene families in B. napus, with two to eight members per family (Table S2). In addition, 75 putative bZIP genes were classified into 10 groups in Arabidopsis [7]. Based on phylogenetic analysis, all BnbZIP members were divided into the same 10 groups as bZIP genes from Arabidopsis (Figure 1), suggesting similar evolutionary trajectories in Arabidopsis and B. napus. However, Group S was divided into two subgroups (S1 and S2, Figure 1), and AtbZIP1-containing clades were classified into the Group C, indicating that they have not only similar structural features with highly conserved areas, but are consistent with the assumption that the originated as the sister groups before the emergence of land plants [45]. In addition, Groups U, V, and W might represent new groups based on the single group including three bZIP members (AtbZIP60, AtbZIP62, and AtbZIP72) in Arabidopsis [7]. Like the bZIP genes of other plants (cassava, grapevine, apple, and Brachypodium distachyon) [44,46], similar gene structures were found in this study, ranging from 0 to 15. Further, 106 of the BnbZIP genes have no more than two introns, confirming the hypothesis that the lower intron numbers might be associated with the stress-response [1,28,47,48,49]. However, some BnbZIP gene family contains more than 6 introns, such as group C, D, and G (Figure 2, Table S2), which were consistent with the results in rice, indicating that they might contain the original BnbZIP genes in these groups [50]. In addition, the motif numbers and composition of were varied in each bZIP family, but the motif 1, a basic region of 16 amino acid residues containing an invariant N-x7-R/K motif [7], were widely detected in all bZIP family (Figure 3 and Figure S1), indicating that they have a highly conserved in protein structures. In all, the phylogeny analysis of BnbZIP genes is consistent with the gene structures and sharing the similar motifs in each group (Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3), which has also been reported in grape and apple [49,51].

B. napus, an ideal model for studying the role of polyploidy in the expansion and evolution of gene families, is an allotetraploid species that has undergone widespread genome duplications and merging events [25]. Some other gene superfamilies in the allotetraploid species B. napus have been described, including the SnRK2, ERF, VOC, ACBP, and MAPKKK superfamilies [52,53,54,55,56]. In the current study, we found that the copy number of bZIP genes varied from two to eight, which is consistent with the finding that two or more copies of homologous genes have been detected in B. napus [57]. Excessive gene loss is also typical after polyploidization in eukaryotes [39,40]. The complete and accurate annotation of genes is an essential starting point for further evolutionary and functional analyses of gene superfamilies. In this study, 89.88% (222/247) BnbZIP genes were accurately mapped onto the 19 B. napus chromosomes (Figure 4), suggesting that WGD events indeed took place during the evolution of Brassica species [58,59]. In addition, while 67 bZIP genes were identified in the Arabidopsis genome and we identified 136 and 130 bZIP genes in the B. oleracea and B. rapa genomes (Table S5), respectively, 247 BnbZIP genes were detected in B. napus (Table S5), implying that more than most of duplicated bZIP genes were lost after WGT. Certainly, the similar deletions or losses of genes after WGT have been observed in the nucleotide-binding site (NBS)-encoding genes or Late embryogenesis abundant (LEA) genes of Brassica species [48,60]. Furthermore, a few tandemly duplicated genes were detected, most of which were found on chromosomes A04, A05, A08, A09, A10, C03, C04, and C09 (Figure 4). Our results further support the notion that these events may have been the result of chromosomal rearrangement during their evolution of Brassica [58]. These results increase our understanding of segmental duplication and WGD for bZIP genes expansion in B. napus.

4.2. Expression Profile Analysis Reveals the Potential Roles of bZIP Genes in Brassica napus

The bZIP TFs play crucial roles in various biological processes, such as signal transduction, stress responses, and plant growth and development [2]. In Arabidopsis, Group A bZIPs, such as AtbZIP39, AtbZIP36, AtbZIP38, AtbZIP66, AtbZIP40, AtbZIP35, and AtbZIP37, are involved in the abiotic stress response or ABA signaling [6,7,24,61]. Numerous bZIP proteins are involved in the drought/osmotic stress response [28,29,30,44], growth and development, organ and tissue differentiation [15], cell elongation [16,17], seed storage protein gene regulation [23], and somatic embryogenesis [24]. In our current study, the 247 bZIP proteins were classified into the same 10 groups as bZIP genes from Arabidopsis (Figure 1). Our results indicate that the encoding bZIP genes, which are homologous to Arabidopsis genes, might play similar roles in specific biological processes.

To investigate the functions of these bZIP genes in more detail, we investigated their transcriptional patterns, which can provide important clues as to their functions in B. napus. We constructed heatmap based on the relative expression levels of the bZIP genes in 17 tissues at different developmental stages (for a total of 42 samples) in ZS11, including roots, hypocotyls, cotyledons, stems, leaves, buds, flowers, and seeds (Table S3). A strong correlation was found between the results of RNA-seq and qRT-PCR, pointing to the reproducibility and reliability of our results. On the whole, although most bZIP genes displayed similar expression patterns among all tissues, these BnbZIP genes exhibited significant variations in expression during development, with different copies of the same gene sometimes exhibiting different expression patterns, suggesting that these BnbZIP TFs might be involved in different biological processes in rapeseed. Of the bZIP TF genes examined, six (BnbZIP13, BnbZIP28, BnbZIP41, BnbZIP2, BnbZIP53, and BnbZIP60) were highly expressed throughout development, suggesting that they might be regulatory genes that function throughout plant development.

The bZIP genes bZIP28, bZIP2, bZIP53, and bZIP60 play positive roles in abiotic stress signaling and responses [62,63], as well as growth and development [23,64]. However, little is known about the roles of BnbZIP13 and BnbZIP41. Conversely, some BnbZIP genes (BnbZIP14, BnbZIP15, BnbZIP66, BnbZIP3, BnbZIP4, BnbZIP5, BnbZIP8, BnbZIP58, BnbZIP70, BnbZIP75, and BnbZIP72) were expressed at relatively low levels throughout development, and we did not detect the expression of some BnbZIP genes, such as BnbZIP34c, BnbZIP55c, BnbZIP30d, BnbZIP3f, BnbZIP11e, BnbZIP48f, BnbZIP58b, BnbZIP58c, BnbZIP75a, BnbZIP75b, and BnbZIP62c. Furthermore, numerous studies indicate that ABA and stress are likely involved in both the transcriptional and post-translational regulation of several Group A bZIPs [3,7,65]. Therefore, the latter BnbZIP proteins might not be involved in plant differentiation and development in rapeseed under normal growth conditions. Moreover, Group S bZIPs are transcriptionally activated after stress treatment (e.g., cold, drought, anaerobic stress, wounding) or are specifically expressed in the flowers of monocot and dicot plants [66,67,68]. The transcript profiles of the Group S genes BnbZIP11 and BnbZIP53 suggest that they might play widespread regulatory roles in the development of B. napus, as do their homologs in Arabidopsis [69,70]. In addition, BnbZIP28 and BnbZIP60 were both highly expressed in B. napus. Interestingly, their homologs in Arabidopsis encode endoplasmic reticulum stress sensors [71] that play key roles in UPR signaling [72,73]. The latest results showed that F-bZIP genes associated with zinc deficiency and salt stress response in A. thaliana [74,75,76] were divided into two subgroups in land plants [77], in accordance the with the present results. In addition, BnbZIP24 have two members, and lower than BnbZIP19 and BnbZIP23, indicating that BnbZIP24 have more prone to gene loss and expansion events. And the expression of BnbZIP24 have lower levels during the whole development stages, but BnbZIP19 and BnbZIP23 have higher levels (Figure 5). Thus, the regulatory mechanisms need much more additional studies. Finally, the high transcript levels of many BnbZIP genes in specific organs suggest that they primarily function during development. Together, our results suggest that bZIP TFs play crucial roles in protecting plants from all types of biological and abiotic stresses, sometimes under specific conditions, laying the foundation for further analysis of the functions of BnbZIPs in B. napus.

5. Conclusions

In total, 247 putative bZIP transcription factors were identified in B. napus, one of the most important oilseed crops and is broadly used for edible vegetable oil and protein-rich meal, and these genes are located in 19 chromosomes, respectively. Further, the 247 bZIP transcription factors were classified in 10 key-clades and three minor-clades based on the phylogenetic analysis. Chromosomal/segmental duplication, and tandem gene duplication, as well as the WGD might have contributed to the major mechanisms contributing to the expansion of the bZIP gene superfamily in eukaryotes. In addition, RNA-Seq based analysis qRT-PCR identification revealed tissue specific expression of these bZIPs. six (BnbZIP13, BnbZIP28, BnbZIP41, BnbZIP2, BnbZIP53, and BnbZIP60) were always highly expressed throughout development, whereas others exhibited significant variations in expression during development, with different copies of the same gene sometimes exhibiting different expression patterns, suggesting that these BnbZIP TFs might be involved in different biological processes in rapeseed. Our results suggest that bZIP TFs play crucial roles in protecting plants from all types of biological and abiotic stresses, sometimes under specific conditions. In all, these genes could be utilized to characterize them and laying the foundation for further elucidating their specific response mechanisms and ultimate integration into B. napus improvement programs.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the utilization of heterosis and selection of strong advantage of hybrid (2016YFD0101300), the Chongqing Natural Science Foundation (cstc2017jcyjAX0321); the 973 Project (2015CB150201), the National Science Foundation of China (31401412, U1302266, 31571701), Projects in the National Science and Technology Pillar Program (2013BAD01B03-12), the 111 Project (B12006); the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (XDJK2016B030). We would also like to thank Kathy Farquharson for critical reading of this manuscript.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at www.mdpi.com/2073-4425/8/10/288/s1. Figure S1: The 247 B. napus BnbZIP amino acid sequences were aligned. Table S1: Primers of the bZIP genes and housekeeping genes used for qRT-PCR. Table S2: List of the identified bZIP genes in B. napus genome. Table S3: The tissues and organs from B. napus ZS11 used in this study. Table S4: Heat map of expression levels of B. napus bZIP transcription factor family genes at different growth periods in different tissues and organs. Table S5: Syntenic gene analysis of bZIP genes in A. thaliana, B. rapa, B. oleracea and B. napus.

Author Contributions

J.N.L. and C.M.Q. conceived and designed the experiments; X.H.H., G.Q.M., M.C.Z. and S.X.W. performed the RNA extraction; L.D.J., A.X.Z. and R.W. performed qPCR experiments and analyzed them; M.W.G., Y.Z. and D.X.X. downloaded the sequences and analyzed the data; X.F.X. and K.L. contributed reagents/materials; J.N.L., C.M.Q. and Y.Z. wrote the paper. We would also like to thank Kathy Farquharson for critical reading of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Nijhawan A., Jain M., Tyagi A.K., Khurana J.P. Genomic survey and gene expression analysis of the basic leucine zipper transcription factor family in rice. Plant Physiol. 2008;146:333–350. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.112821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wei K., Chen J., Wang Y., Chen Y., Chen S., Lin Y., Pan S., Zhong X., Xie D. Genome-Wide Analysis of bZIP-Encoding Genes in Maize. DNA Res. 2012;19:463–476. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dss026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Finkelstein R.R., Lynch T.J. The Arabidopsis Abscisic Acid Response Gene ABI5 Encodes a Basic Leucine Zipper Transcription Factor. Plant Cell. 2000;12:599–609. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.4.599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bensmihen S., Rippa S., Lambert G., Jublot D., Pautot V., Granier F., Giraudat J., Parcy F. The Homologous ABI5 and EEL Transcription Factors Function Antagonistically to Fine-Tune Gene Expression during Late Embryogenesis. Plant Cell. 2002;14:1391–1403. doi: 10.1105/tpc.000869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Casaretto J., Ho T.H. The transcription factors HvABI5 and HvVP1 are required for the abscisic acid induction of gene expression in barley aleurone cells. Plant Cell. 2003;15:271–284. doi: 10.1105/tpc.007096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hossain M.A., Jungil C., Han M., Chulhyun A., Jongseong J., An G., Park P.B. The ABRE-binding bZIP transcription factor OsABF2 is a positive regulator of abiotic stress and ABA signaling in rice. J. Plant Physiol. 2010;167:1512–1520. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2010.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jakoby M., Weisshaar B., Drögelaser W., Vicente-Carbajosa J., Tiedemann J., Kroj T., Parcy F. bZIP transcription factors in Arabidopsis. Trends Plant Sci. 2002;7:106–111. doi: 10.1016/S1360-1385(01)02223-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weltmeier F., Rahmani F., Ehlert A., Dietrich K., Schütze K., Wang X., Chaban C., Hanson J., Teige M., Harter K. Expression patterns within the Arabidopsis C/S1 bZIP transcription factor network: Availability of heterodimerization partners controls gene expression during stress response and development. Plant Mol. Biol. 2009;69:107–119. doi: 10.1007/s11103-008-9410-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gupta S., Chattopadhyay M.K., Chatterjee P., Ghosh B., Sengupta D.N. Expression of abscisic acid-responsive element-binding protein in salt-tolerant Indica rice (Oryza sativa L. cv. Pokkali) Plant Mol. Biol. 1998;37:629–637. doi: 10.1023/A:1005934200545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kobayashi F., Maeta E., Terashima A., Takumi S. Positive role of a wheat HvABI5 ortholog in abiotic stress response of seedlings. Physiol. Plant. 2008;134:74–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2008.01107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hsieh T.H., Li C.W., Su R.C., Cheng C.P., Sanjaya, Tsai Y.C., Chan M.T. A tomato bZIP transcription factor, SlAREB, is involved in water deficit and salt stress response. Planta. 2010;231:1459–1473. doi: 10.1007/s00425-010-1147-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yáñez M., Cáceres S., Orellana S., Bastías A., Verdugo I., Ruizlara S., Casaretto J.A. An abiotic stress-responsive bZIP transcription factor from wild and cultivated tomatoes regulates stress-related genes. Plant Cell Rep. 2009;28:1497–1507. doi: 10.1007/s00299-009-0749-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liao Y., Zhang J.S., Chen S.Y., Zhang W.K. Role of Soybean GmbZIP132 under Abscisic Acid and Salt Stresses. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2008;50:221–230. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2007.00593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee S.C., Choi H.W., Hwang I.S., Du S.C., Hwang B.K. Functional roles of the pepper pathogen-induced bZIP transcription factor, CAbZIP1, in enhanced resistance to pathogen infection and environmental stresses. Planta. 2006;224:1209–1225. doi: 10.1007/s00425-006-0302-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chuang C.F., Running M.P., Williams R.W., Meyerowitz E.M. The PERIANTHIA gene encodes a bZIP protein involved in the determination of floral organ number in Arabidopsis thaliana. Gene Dev. 1999;13:334–344. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.3.334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fukazawa J., Sakai T., Ishida S., Yamaguchi I., Kamiya Y., Takahashi Y. Repression of shoot growth, a bZIP transcriptional activator, regulates cell elongation by controlling the level of gibberellins. Plant Cell. 2000;12:901–915. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.6.901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yin Y., Zhu Q., Dai S., Lamb C., Beachy R.N. RF2a, a bZIP transcriptional activator of the phloem-specific rice tungro bacilliform virus promoter, functions in vascular development. Embo J. 1997;16:5247–5259. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.17.5247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baena-González E., Rolland F., Thevelein J.M., Sheen J. A central integrator of transcription networks in plant stress and energy signalling. Nature. 2007;448:938–942. doi: 10.1038/nature06069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ciceri P., Locatelli F., Genga A., Viotti A., Schmidt R.J. The Activity of the Maize Opaque2 Transcriptional Activator Is Regulated Diurnally. Plant Physiol. 1999;121:1321–1328. doi: 10.1104/pp.121.4.1321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weltmeier F., Ehlert A., Mayer C.S., Dietrich K., Wang X., Schütze K., Alonso R., Harter K., Vicente-Carbajosa J., Dröge-Laser W. Combinatorial control of Arabidopsis proline dehydrogenase transcription by specific heterodimerisation of bZIP transcription factors. Embo J. 2006;25:3133–3143. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iwata Y., Koizumi N. An Arabidopsis transcription factor, AtbZIP60, regulates the endoplasmic reticulum stress response in a manner unique to plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:5280–5285. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408941102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu J.X., Srivastava R., Che P., Howell S.H. Salt stress responses in Arabidopsis utilize a signal transduction pathway related to endoplasmic reticulum stress signaling. Plant J. 2007;51:897–909. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03195.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lara P., Oñate-Sánchez L., Abraham Z., Ferrándiz C., Díaz I., Carbonero P., Vicente-Carbajosa J. Synergistic Activation of Seed Storage Protein Gene Expression in Arabidopsis by ABI3 and Two bZIPs Related to OPAQUE2. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:21003–21011. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210538200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guan Y.C., Ren H.B., He X., Ma Z.Y., Fan C. Identification and characterization of bZIP-type transcription factors involved in carrot (Daucus carota L.) somatic embryogenesis. Plant J. 2009;60:207–217. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.03948.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chalhoub B., Denoeud F., Liu S., Parkin I.A., Tang H., Wang X., Chiquet J., Belcram H., Tong C., Samans B., et al. Early allopolyploid evolution in the post-Neolithic Brassica napus oilseed genome. Science. 2014;345:950–953. doi: 10.1126/science.1253435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jenczewski E., Chèvre A., Alix K. Chromosomal and gene expression changes in Brassica Allopolyploids. In: Chen J., Birchle J., editors. Polyploid and Hybrid Genomics. John Wiley and Sons, Inc.; Oxford, IA, USA: 2013. pp. 171–186. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee T.H., Tang H., Wang X., Paterson A.H. PGDD: A database of gene and genome duplication in plants. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D1152–D1158. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang J., Zhou J., Zhang B., Vanitha J., Ramachandran S., Jiang S.Y. Genome-wide Expansion and Expression Divergence of the Basic Leucine Zipper Transcription Factors in Higher Plants with an Emphasis on Sorghum. J. Plant Ecol. 2011;53:212–231. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2010.01017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu J., Chen N., Chen F., Cai B., Santo S.D., Tornielli G.B., Pezzotti M., Cheng Z.M. Genome-wide analysis and expression profile of the bZIP transcription factor gene family in grapevine (Vitis vinifera) BMC Genom. 2014;15:281. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baloglu M.C., Eldem V., Hajyzadeh M., Unver T. Genome-wide analysis of the bZIP transcription factors in cucumber. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e96014. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jin Z., Xu W., Liu A. Genomic surveys and expression analysis of bZIP gene family in castor bean (Ricinus communis L.) Planta. 2014;239:299–312. doi: 10.1007/s00425-013-1979-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pourabed E., Ghane G.F., Soleymani M.P., Razavi S.M., Shobbar Z.S. Basic Leucine Zipper Family in Barley: Genome-Wide Characterization of Members and Expression Analysis. Mol. Biotechnol. 2015;57:1–15. doi: 10.1007/s12033-014-9797-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Altschul S.F., Madden T.L., Schäffer A.A., Zhang J., Zhang Z., Miller W., Lipman D.J. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Larkin M.A., Blackshields G., Brown N., Chenna R., McGettigan P.A., McWilliam H., Valentin F., Wallace I.M., Wilm A., Lopez R. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2947–2948. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tamura K., Stecher G., Peterson D., Filipski A., Kumar S. MEGA6: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013;30:2725–2729. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bailey T.L., Boden M., Buske F.A., Frith M., Grant C.E., Clementi L., Ren J., Li W.W., Noble W.S. MEME SUITE: Tools for motif discovery and searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:W202–W208. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Voorrips R.E. MapChart: Software for the graphical presentation of linkage maps and QTLs. J. Hered. 2002;93:77–78. doi: 10.1093/jhered/93.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Qu C., Fu F., Liu M., Zhao H., Liu C., Li J., Tang Z., Xu X., Qiu X., Wang R. Comparative Transcriptome Analysis of Recessive Male Sterility (RGMS) in Sterile and Fertile Brassica napus Lines. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0144118. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0144118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Trapnell C., Roberts A., Goff L., Pertea G., Kim D., Kelley D.R., Pimentel H., Salzberg S.L., Rinn J.L., Pachter L. Differential gene and transcript expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with TopHat and Cufflinks. Nat. Protoc. 2012;7:562–578. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Deng W., Wang Y., Liu Z., Cheng H., Xue Y. HemI: A Toolkit for Illustrating Heatmaps. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e111988. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0111988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu G., Zhang L., Wu Y.H., Cao Y.L., Lu C.M. Comparison of Five Endogenous Reference Genes for Specific PCR Detection and Quantification of Brassica napus. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010;58:2812–2817. doi: 10.1021/jf904255b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sankoff D., Zheng C., Zhu Q. The collapse of gene complement following whole genome duplication. BMC Genom. 2010;11:1–11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang J., Lydiate D.J., Parkin I.A., Falentin C., Delourme R., Carion P.W., King G.J. Integration of linkage maps for the Amphidiploid Brassica napus and comparative mapping with Arabidopsis and Brassica rapa. BMC Genom. 2011;12:101. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu X., Chu Z. Genome-wide evolutionary characterization and analysis of bZIP transcription factors and their expression profiles in response to multiple abiotic stresses in Brachypodium distachyon. BMC Genom. 2015;16:227. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1457-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Peviani A., Lastdrager J., Hanson J., Snel B. The phylogeny of C/S1 bZIP transcription factors reveals a shared algal ancestry and the pre-angiosperm translational regulation of S1 transcripts. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:30444. doi: 10.1038/srep30444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hu W., Yang H., Yan Y., Wei Y., Tie W., Ding Z., Jiao Z., Peng M., Li K. Genome-wide characterization and analysis of bZIP transcription factor gene family related to abiotic stress in cassava. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:22783. doi: 10.1038/srep22783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lan T., Gao J., Zeng Q.Y. Genome-wide analysis of the LEA (late embryogenesis abundant) protein gene family in Populus trichocarpa. Tree Genet. Genomes. 2013;9:253–264. doi: 10.1007/s11295-012-0551-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liang Y., Xiong Z., Zheng J., Xu D., Zhu Z., Xiang J., Gan J., Raboanatahiry N., Yin Y., Li M. Genome-wide identification, structural analysis and new insights into late embryogenesis abundant (LEA) gene family formation pattern in Brassica napus. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:24265. doi: 10.1038/srep24265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhao J., Guo R., Guo C., Hou H., Wang X., Gao H. Evolutionary and Expression Analyses of the Apple Basic Leucine Zipper Transcription Factor Family. Front. Plant Sci. 2016;7 doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nuruzzaman M., Manimekalai R., Sharoni A.M., Satoh K., Kondoh H., Ooka H., Kikuchi S. Genome-wide analysis of NAC transcription factor family in rice. Gene. 2010;465:30–44. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2010.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gao M., Zhang H., Guo C., Cheng C., Guo R., Mao L., Fei Z., Wang X. Evolutionary and Expression Analyses of Basic Zipper Transcription Factors in the Highly Homozygous Model Grape PN40024 (Vitis vinifera L.) Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 2014;32:1085–1102. doi: 10.1007/s11105-014-0723-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liang Y., Wan N., Cheng Z., Mo Y., Liu B., Liu H., Raboanatahiry N., Yin Y., Li M. Whole-Genome Identification and Expression Pattern of the Vicinal Oxygen Chelate Family in Rapeseed (Brassica napus L.) Front. Plant Sci. 2017;8:745. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ma J.Q., Jian H.J., Yang B., Lu K., Zhang A.X., Liu P., Li J.N. Genome-wide analysis and expression profiling of the GRF gene family in oilseed rape (Brassica napus L.) Gene. 2017;620:36–45. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2017.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Raboanatahiry N.H., Yin Y., Li C., Li M. Genome-wide identification and Phylogenic analysis of kelch motif containing ACBP in Brassica napus. BMC Genom. 2015;16:512. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1735-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sun Y., Wang C., Yang B., Wu F., Hao X., Liang W., Niu F., Yan J., Zhang H., Wang B. Identification and functional analysis of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase (MAPKKK) genes in canola (Brassica napus L.) J. Exp. Bot. 2014;65:2171–2188. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eru092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yoo M.J., Ma T., Zhu N., Liu L., Harmon A.C., Wang Q., Chen S. Genome-wide identification and homeolog-specific expression analysis of the SnRK2 genes in Brassica napus guard cells. Plant Mol. Biol. 2016;91:211–227. doi: 10.1007/s11103-016-0456-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cavell A.C., Lydiate D.J., Parkin I.A., Dean C., Trick M. Collinearity between a 30-centimorgan segment of Arabidopsis thaliana chromosome 4 and duplicated regions within the Brassica napus genome. Genome. 1998;41:62–69. doi: 10.1139/g97-097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cheng F., Wu J., Wang X. Genome triplication drove the diversification of Brassica plants. Hortic. Res. 2014;1:14024. doi: 10.1038/hortres.2014.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rana D., Boogaart T., O’neill C.M., Hynes L., Bent E., Macpherson L., Park J.Y., Lim Y.P., Bancroft I. Conservation of the microstructure of genome segments in Brassica napus and its diploid relatives. Plant J. 2004;40:725–733. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yu J., Tehrim S., Zhang F., Tong C., Huang J., Cheng X., Dong C., Zhou Y.V., Qin R., Hua W., et al. Genome-wide comparative analysis of NBS-encoding genes between Brassica species and Arabidopsis thaliana. BMC Genom. 2014;15:3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nakashima K., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K., Shinozaki K. The transcriptional regulatory network in the drought response and its crosstalk in abiotic stress responses including drought, cold, and heat. Front. Plant Sci. 2014;5:170. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2014.00170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Li L.M., Lü S.Y., Li R.J. The Arabidopsis endoplasmic reticulum associated degradation pathways are involved in the regulation of heat stress response. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017;487:362–367. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.04.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhu J.K. Abiotic stress signaling and responses in plants. Cell. 2016;167:313–324. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.08.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Restovic F., Espinoza-Corral R., Gómez I., Vicente-Carbajosa J., Jordana X. An active Mitochondrial Complex II Present in Mature Seeds Contains an Embryo-Specific Iron—Sulfur Subunit Regulated by ABA and bZIP53 and Is Involved in Germination and Seedling Establishment. Front. Plant Sci. 2017;8:277. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Uno Y., Furihata T., Abe H., Yoshida R., Shinozaki K., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K. Arabidopsis basic leucine zipper transcription factors involved in an abscisic acid-dependent signal transduction pathway under drought and high-salinity conditions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:11632–11637. doi: 10.1073/pnas.190309197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Martínez-García J.F., Moyano E., Alcocer M.J., Martin C. Two bZIP proteins from Antirrhinum flowers preferentially bind a hybrid C-box/G-box motif and help to define a new sub-family of bZIP transcription factors. Plant J. 1998;13:489–505. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1998.00050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Seong E.S., Kwon S.U., Ghimire B.K., Yu C.Y., Cho D.H., Lim J.D., Kim K.S., Heo K., Lim E.S., Chung I.M. LebZIP2 induced by salt and drought stress and transient overexpression by Agrobacterium. BMB Rep. 2008;41:693–698. doi: 10.5483/BMBRep.2008.41.10.693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Strathmann A., Kuhlmann M., Heinekamp T., Drögelaser W. BZI-1 specifically heterodimerises with the tobacco bZIP transcription factors BZI-2, BZI-3/TBZF and BZI-4, and is functionally involved in flower development. Plant J. 2001;28:397–408. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2001.01164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Weiste C., Pedrotti L., Selvanayagam J., Muralidhara P., Fröschel C., Novák O., Ljung K., Hanson J., Dröge-Laser W. The Arabidopsis bZIP11 transcription factor links low-energy signalling to auxin-mediated control of primary root growth. PLoS Genet. 2017;13:e1006607. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhang L., Becker D.F. Connecting proline metabolism and signaling pathways in plant senescence. Front. Plant Sci. 2015;6:552. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.00552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shen L., Li F., Dong W., Liu W., Qian Y., Yang J., Wang F., Wu Y. Nicotiana benthamiana NbbZIP28, a possible regulator of unfolded protein response, plays a negative role in viral infection. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2017:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s10658-017-1231-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Angelos E., Ruberti C., Kim S.J., Brandizzi F. Maintaining the factory: The roles of the unfolded protein response in cellular homeostasis in plants. Plant J. 2017;90:671–682. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Liu J.X., Srivastava R., Che P., Howell S.H. An endoplasmic reticulum stress response in Arabidopsis is mediated by proteolytic processing and nuclear relocation of a membrane-associated transcription factor, bZIP28. Plant Cell. 2007;19:4111. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.050021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Popova O.V., Yang O., Dietz K.-J., Golldack D. Differential transcript regulation in Arabidopsis thaliana and the halotolerant Lobularia maritima indicates genes with potential function in plant salt adaptation. Gene. 2008;423:142–148. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2008.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yang O., Popova O.V., Süthoff U., Lüking I., Dietz K.J., Golldack D. The Arabidopsis basic leucine zipper transcription factor AtbZIP24 regulates complex transcriptional networks involved in abiotic stress resistance. Gene. 2009;436:45–55. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2009.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Assunção A., Herrero E., Lin Y.-F., Huettel B., Talukdar S., Smaczniak C., Immink R., van Eldik M., Fiers M., Schat H., et al. Arabidopsis thaliana transcription factors bZIP19 and bZIP23 regulate the adaptation to zinc deficiency. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:10296–10301. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004788107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Castro P.H., Lilay G.H., Muñoz-Mérida A., Schjoerring J.K., Azevedo H., Assunção A.G.L. Phylogenetic analysis of F-bZIP transcription factors indicates conservation of the zinc deficiency response across land plants. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:3806. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-03903-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.