Abstract

Objective

The US Department of Justice has called for the creation of trauma-informed juvenile justice systems in order to combat the negative impact of trauma on youth offenders and front-line staff. Definitions of trauma-informed care have been proposed for various service systems yet there is not currently a widely accepted definition for juvenile justice. The current systematic review examined published definitions of a trauma-informed juvenile justice system in an effort to identify the most commonly named core elements and specific interventions or policies.

Method

A systematic literature search was conducted in 10 databases to identify publications that defined trauma-informed care or recommended specific practices or policies for the juvenile justice system.

Results

We reviewed 950 unique records, of which 10 met criteria for inclusion. The 10 publications included 71 different recommended interventions or policies that reflected 10 core domains of trauma-informed practice. We found eight specific practice or policy recommendations with relative consensus, including staff training on trauma and trauma-specific treatment, while most recommendations were included in two or less definitions.

Conclusion

The extant literature offers relative consensus around the core domains of a trauma-informed juvenile justice system but much less agreement on the specific practices and policies. A logical next step is a review of the empirical research to determine which practices or policies produce positive impacts on outcomes for youth, staff, and the broader agency environment, which will help refine the core definitional elements that comprise a unified theory of trauma-informed practice for juvenile justice.

Keywords: juvenile justice, adolescents, trauma-informed, trauma responsive, traumatic stress

Childhood exposure to violence and other traumatic events is increasingly recognized as a major public health challenge due to its association with a host of deleterious long-term outcomes (National Prevention Council, 2011). While the majority of Americans will experience at least one traumatic event before the age of 18 (McLaughlin et al., 2012), trauma disproportionately affects youth involved with the juvenile justice system (Miller, Green, Fettes, & Aarons, 2011). An estimated 70–90% of youth offenders have experienced one or more types of trauma, including high rates of physical or sexual abuse, witnessing domestic violence, and exposure to violence in school or the community (Abram et al., 2004; Ford, Hartman, Hawke, & Chapman, 2008). Accumulating evidence suggests that childhood trauma exposure is likely a key risk factor for subsequent juvenile justice involvement (Kerig & Becker, 2010). Juvenile offenders are a particularly vulnerable population but those with histories of trauma exposure and/or symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) have higher rates of recidivism, co-occurring disorders, school drop-out, and suicide attempts (Cauffman, Monahan, & Thomas, 2015; Haynie, Petts, Maimon, & Piquero, 2009; Wasserman & McReynolds, 2011; Wolff, Baglivio, & Piquero, 2015). Multiple investigators have argued persuasively that youth may cope with traumatic stress in ways that increase their risk of arrest, including using drugs to avoid distressing memories, running away from an abusive home, and carrying a weapon or joining a gang to prevent re-victimization (DeHart & Moran, 2015; Ford, Chapman, Mack, & Pearson, 2006; Kerig & Becker, 2010).

Involvement in the justice system itself places youth at risk for exposure to additional trauma as well as harsh practices that may exacerbate their psychological distress and contribute to worse legal outcomes. Potential sources of trauma in the justice system include discriminatory law enforcement practices like “Stop and Frisk,” abusive behavior by correctional staff, and the high rates of physical and sexual victimization in juvenile justice facilities, all of which are associated with an increased risk of PTSD symptoms (Dierkhising, Lane, & Natsuaki, 2014; Geller, Fagan, Tyler, & Link, 2014). Youth with prior trauma exposure may be “triggered” and suffer psychological distress in response to several invasive or coercive practices commonly used in the justice system, including strip searches/pat downs, placement in secure facilities with limited access to loved ones, and use of punitive seclusion or physical restraint in detention or correctional settings. A small retrospective study of young adults (ages 18-20) that had been discharged from a juvenile justice facility in the past year found a significant, positive association between exposure to abuse and/or harsh punishments (i.e., seclusion) while incarcerated and continued criminal behavior post-release (Dierkhising et al., 2014). Thus, the justice system may impede the efforts of trauma survivors to rehabilitate and desist from crime.

The negative impact of trauma within juvenile justice goes beyond youth offenders. It is increasingly recognized that front-line justice system professionals are frequently exposed to traumatic stressors in the line of duty, including witnessing or experiencing violence and hearing details of trauma experienced by crime victims or youth offenders (Chamberlain & Miller, 2008; Kunst, 2011; Rainville, 2015). A growing literature reveals high rates of moderate to severe traumatic stress symptoms in samples of correctional staff, probation officers, law enforcement, and attorneys (Denhof & Spinaris, 2013; Levin et al., 2011; Skogstad et al., 2013). Traumatic stress is associated with impaired job performance among justice system professionals (Denhof & Spinaris, 2013). Taken together, these findings suggest that trauma contributes to worse outcomes for all involved with the juvenile justice system.

Trauma-Informed Care

Increased public awareness of trauma’s pernicious effects and its prevalence among society’s most vulnerable populations has led to calls from a number of key stakeholders for the creation of trauma-informed public service systems (National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors, 2005; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2014). Trauma-informed care (TIC) is an approach to organizing services that integrates an understanding of the impact and consequences of trauma into all interventions and aspects of organizational functioning (American Association of Children’s Residential Centers, 2014). Implementing TIC goes beyond offering mental health interventions designed to treat symptoms of PTSD and requires organizations and service systems to examine how their practices, policies, and environments foster a sense of safety among consumers with histories of trauma exposure (Kusmaul, Wilson, & Nochajski, 2015). According to Elliott, Bjelajac, Fallot, Markoff, and Reed (2005), in a trauma-informed organization, “all staff … from the receptionist to the direct care workers to the board of directors, must understand how violence impacts the lives of people being served, so that every interaction is consistent with the recovery process and reduces the possibility of re-traumatization” (p. 462). For many agencies and service systems, TIC represents a significant shift in thinking and practice.

The concept of trauma-informed service systems was first introduced into the literature over 15 years ago by Harris and Fallot (2001). Since then, several researchers and stakeholder groups have attempted to define a TIC approach. These definitions include broad principles or domains of TIC (e.g., staff education/competence around trauma, physically and psychologically safe environment of care, client-centered service planning) and/or recommendations for specific trauma-informed practices or policies (e.g., eliminating or restricting harsh or coercive practices, mandatory trauma training for all staff, universal screening of clients for trauma exposure and related impairment) (Hopper, Bassuk, & Olivet, 2010; Raja, Hasnain, Hoersch, Gove-Yin, & Rajagopalan, 2015; Wall, Higgins, & Hunter, 2016). Although there is general agreement in the literature that TIC refers to the integration of trauma awareness and understanding throughout an organization or service system, there is currently no consensus-based definition on the particular practices or policies that comprise this approach for any service system (Hopper et al., 2010). Multiple authors have identified the lack of consensus on the definition of TIC as a primary barrier to creating trauma-informed systems (Hanson & Lang, 2016; Hopper et al., 2010; Wall et al., 2016).

The Current Study

While the basic definition of TIC cuts across service systems, the particular practices or policies that are implemented should be tailored to fit the unique mission and challenges of each system. There is currently no TIC definition for juvenile justice that has been widely accepted even though several federal agencies and stakeholder organizations have established initiatives to promote the adoption of TIC in the justice system (Federal Partners Committee on Women and Trauma, 2013; National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges, n.d.). This lack of consensus has contributed to confusion among juvenile justice system leaders and front-line providers as to what exactly is meant by TIC (Donisch, Bray, & Gewirtz, 2016). Identifying the specific components (practices, policies) of a trauma-informed juvenile justice system is a prerequisite for developing and evaluating TIC service models. The primary aim of the current study is to review systematically the extant literature on definitions or descriptions of TIC for the juvenile justice system in order to identify the most commonly named core domains and recommended practices or policies. Additionally, we will identify areas of consensus or disagreement and directions for future research.

Method

Study Protocol and Inclusion Criteria

The first author developed the study protocol based on the established guidelines for systematic literature reviews (Shamseer et al., 2015). A copy of the full protocol is available upon request. Our review focused on identifying English-language records published since 2000 that proposed an original definition of trauma-informed care (TIC) specific to the juvenile justice system (whole system or any of the following settings: law enforcement, juvenile courts, diversion programs, probation departments, detention or correctional facilities). For the present review, we operationalized this as publications where a primary focus was identifying core principles or domains of TIC (i.e., promoting a safe environment of care) and/or recommending specific trauma-informed practices, policies, or procedures for the juvenile justice system (i.e., staff training on working with trauma-affected youth, trauma-specific mental health services).

We excluded publications that called for TIC in juvenile justice without defining it, simply cited an existing definition without adding new recommendations, or defined TIC for the adult criminal justice system or for multiple service systems without offering juvenile justice specific definition/recommendations. Because TIC is a system-wide approach, we excluded publications whose definition/recommendations were limited to trauma-informed clinical services (i.e., screening/assessment, treatment). Additionally we limited our search to journal manuscripts, books, white papers, government/stakeholder agency reports or policy statements, articles in trade magazines/newsletters (e.g., American Jails magazine), and web-based resources (i.e., stakeholder agency websites with TIC definitions). We excluded dissertations, conference abstracts/presentations, webinars/online presentations, blog posts, and popular press articles.

Literature Search Strategy

We used a four step process to identify eligible studies. First, literature searches were conducted in 10 databases (EBSCO Criminal Justice, ERIC, National Criminal Justice Reference Service, Ovid PsycINFO, ProQuest Criminal Justice, ProQuest Psychology, ProQuest Published International Literature on Traumatic Stress, ProQuest Social Science, ProQuest Social Services Abstracts, PubMed) using the search terms (“trauma informed” OR “trauma focused” OR “trauma responsive”) AND (“juvenile justice” OR probation OR court* OR “law enforcement” OR “diversion program” OR “juvenile detention”). In May 2016, the first author conducted the literature searches and compiled a list of the complete reference and abstract for every record identified. Two reviewers (Branson & Baetz) independently reviewed all abstracts to determine if they met our inclusion criteria. For each abstract that was selected for further review by either reviewer, we then retrieved the full-text document. Two reviewers independently reviewed the full-text articles to determine if they met inclusion criteria. In cases of disagreement, the two authors discussed the publication until a consensus was reached. The overall level of interrater agreement was adequate (κ = .62).

In the second step, the first author reviewed the reference lists of all publications selected for inclusion to identify other potentially eligible records. Next, we conducted a “cited by” search in Google Scholar of all selected publications. For all new publications identified through these steps, we repeated the two-step process (independent review of abstracts then full-text). The final step consisted of a Google internet search for web-based resources. We made the a priori decision to limit our review to the first 20 pages of hits (i.e., 200 websites). Web-based records that appeared to meet inclusion criteria were saved in PDF format and reviewed by the first and second author.

Data Extraction and Coding

Two reviewers (Branson & Baetz) independently extracted and coded data from all articles selected for inclusion using a data collection form and codebook designed for the current study (available upon request). The following variables were extracted and coded: publication year, publication type (i.e., journal article, agency report), focus of TIC definition (i.e., entire juvenile justice system or particular setting such as probation departments), core elements of TIC (i.e., broad principles or categories of TIC for juvenile justice system), and specific trauma-informed practices/policies/interventions that were recommended.

Data Analysis and Synthesis

We used content analysis to identify and code recurring themes regarding the core principles or domains of trauma-informed care for juvenile justice and the specific strategies or practices recommended for each domain. This approach was guided by the “coding consensus, co-occurrence, and comparison” methodology described by Willms et al. (1990), in which both a priori and emergent themes (i.e., core domains or specific practices) are coded to construct a conceptual framework (Palinkas, 2014). First, a primary coder (first author) extracted and coded data from all the records. A second coder (second author) repeated this for 50% of the records and examined the first coder's work on the other half. Three a priori categories (clinical services, agency context, system-level) provided an initial framework for organizing the data. The coders extracted verbatim anything that appeared to be a recommendation (e.g., agencies/systems should train staff on trauma) or explicitly identified core domains or principles of a trauma-informed juvenile justice system. After reading through all the data, the coders drafted preliminary domains (e.g., creating a safe environment). Next, the coders organized similar recommendations together in a word processing document and assigned them to a domain. Through discussion the two coders came to a consensus on names of the broad domains and the wording and categorization of specific practice or policy recommendations.

Results

Literature Search Results

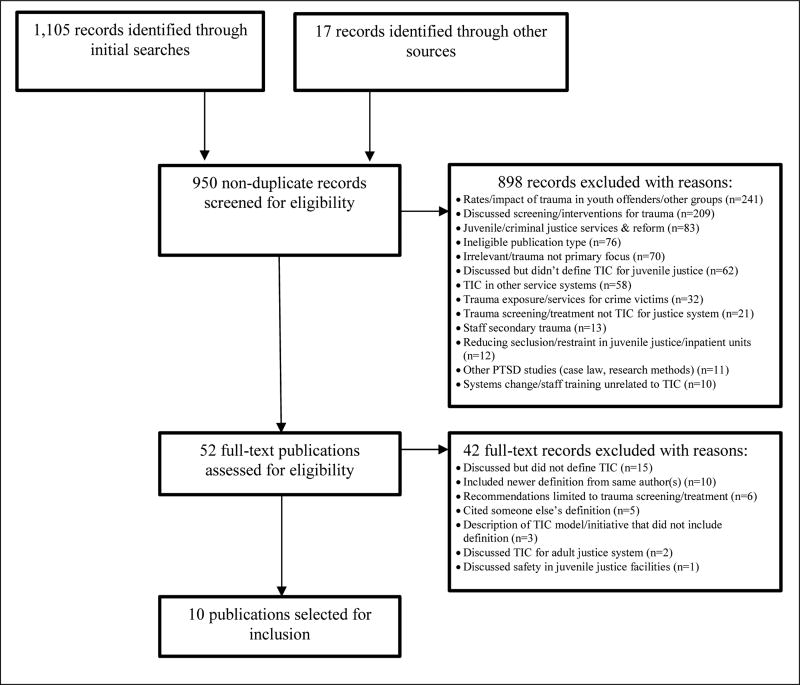

Our literature search identified a total of 950 unique records, of which 898 were excluded during the initial screening. Records excluded at this stage included numerous studies on the prevalence/impact of trauma exposure (e.g., Wolff et al., 2015) and trauma-specific mental health services (e.g., Black, Woodworth, Tremblay, & Carpenter, 2012) for youth offenders and other populations. Fifty-two full-text records were reviewed, of which 42 were excluded, leaving a total of 10 publications selected for inclusion (denoted by an asterisk in the References). The 42 excluded full-text records included 15 publications that called for TIC in juvenile justice but did not provide a definition or detailed recommendations (e.g., Ko et al., 2008), six publications that discussed trauma screening/treatment only (e.g., Igelman, Ryan, Gilbert, Bashant, & North, 2008), and five publications that cited someone else’s definition of TIC (e.g., Crosby, 2016).

There were five instances where we found multiple publications from the same author(s) that met our inclusion criteria. We extracted and coded the data from all of these publications. In four cases, we excluded a second publication that included identical or less complete recommendations (Feierman & Fine, 2014; Ford, 2012; National Center for Mental Health and Juvenile Justice, n.d.; Sickmund, 2016) than another eligible publication from the same author(s) (Feierman & Ford, 2016; National Center for Mental Health and Juvenile Justice & Technical Assistance Collaborative, 2015; National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges, 2015). In the remaining case, we excluded a series of policy briefs from the National Child Traumatic Stress Network (Burrell, 2013; Dierkhising, Ko, & Goldman, 2013; Kerig, 2013; Lacey, 2013; Rozzell, 2013; Stewart, 2013) in favor of a more recent publication (National Child Traumatic Stress Network, 2016) as the former explicitly stated that it was a preliminary attempt to start defining the core elements of TIC for juvenile justice. A complete list of the excluded records is available upon request. Figure 1 provides a detailed summary of our search.

Figure 1.

Summary of the literature search

Publication Characteristics

We reviewed 10 publications that defined TIC and/or recommended specific trauma-informed practices or policies for the juvenile justice system (see Table 1). Four publications gave definitions or recommendations for the entire system and three defined TIC for juvenile or family courts. The remaining three definitions/recommendations included one apiece for juvenile detention/correctional facilities, diversion programs, and law enforcement. Publication dates ranged from 2012 to 2016, with half published in the past two years.

Table 1.

Publications Included in Systematic Review

| Publication | Focus of TIC definition | Broad domains of TIC identified |

|---|---|---|

| American Bar Association (ABA; 2014) | Courts | NA |

| Attorney General’s National Task Force on Children Exposed to Violence (2012) | Whole system | NA |

| Feierman & Ford (2016) | Whole system | NA |

| Griffin et al. (2012) | Juvenile justice facilities | NA |

| International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP; 2014) | Law enforcement | NA |

| National Center for Mental Health and Juvenile Justice & Technical Assistance Collaborative (NCMHJJ; 2015) | Probation/Diversion programs | Leadership; Policy & procedures; Environment; Engagement & involvement; Cross sector collaboration; Intervention continuum; Funding strategies; Workforce development; Quality assurance & evaluation |

| National Child Traumatic Stress Network (NCTSN; 2016) | Whole system | Policies & procedures; Screening; Clinical assessment/Intervention; Programming & staff education; Prevention & management of secondary traumatic stress; Partnering with youth & families; Cross system collaboration; Addressing disparities & diversity |

| National Council of Juvenile & Family Court Judges (NCJFCJ; 2015) | Courts/Judges | NA |

| Pilnik & Kendall (2012) | Courts/Attorneys | NA |

| Rapp (2016) | Whole system | Governing/Leadership; Culture/Mission/Goals; Programming; Staff/Personnel; System collaboration; Policies; Physical environment; Monitoring/Evaluationa |

These domains were adapted from Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (2014)

TIC Definitions & Recommendations

The 10 publications included a total of 71 different practice or policy recommendations representing 10 major principles or domains of trauma-informed practice for juvenile justice. We further organized these 10 domains into three categories based on their level of focus: clinical services, agency context, and system-level (see Table 2). For each of these domains, we identified all of the specific trauma-informed practices or policies that were recommended and how often they were recommended across the 10 definitions (see Table 3). The number of recommendations included in these definitions ranged from four to 37 (M: 19.20, SD: 11.24). On average, publications that defined TIC for the entire system included more recommendations (M: 25.67, SD: 9.50) compared to definitions of TIC intended for particular justice settings like courts or law enforcement (M: 16.43, SD: 11.39).

Table 2.

Core Domains of Trauma-Informed Care for Juvenile Justice

| Area of Focus | Domains within this area |

|---|---|

| Clinical Services | 1. Screening & assessment |

| 2. Services & interventions | |

| 3. Cultural competence | |

| Agency Context | 4. Youth & family engagement/involvement |

| 5. Workforce development & support | |

| 6. Promoting a safe agency environment | |

| 7. Agency policies, procedures, & leadership | |

| System-level | 8. Cross-system collaboration |

| 9. System-level policies & procedures | |

| 10. Quality assurance & evaluation |

Table 3.

Recommended Trauma-Informed Practices and Policies for the Juvenile Justice System

| Domain/Recommendations | Publications with this recommendationa |

nb | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Domain 1: Screening/Assessment | |||

| 1. | Universal screening for trauma-related impairment (trauma exposure, PTSD) and comprehensive, trauma- informed mental health assessments by a qualified clinician for youth who screen positive | 1–4, 6–10 | 9 |

| 2. | Use screening/assessment measures that are validated with diverse populations | 1, 3, 8 | 3 |

| 3. | Utilize screening/assessment measures that are validated with justice-involved youth | 1, 6, 8 | 3 |

| 4. | Use interviews over self-report measures to improve accurate identification of symptoms | 7 | 1 |

| 5. | Assessment should be used to monitor progress and evaluate client outcomes | 7 | 1 |

| 6. | Assessment must be completed without asking youth to repeat trauma stories in multiple interviews | 10 | 1 |

| Recommended areas to screen/assess: | |||

| • Trauma exposure | 2, 4, 7, 8, 10 | 5 | |

| • PTSD symptoms | 4, 7, 8 | 3 | |

| • Relationship between PTSD symptoms and criminogenic risk-needs-responsivity (RNR) factors | 8 | 1 | |

| • Callous-unemotional traits | 2 | 1 | |

| • Commercial sexual exploitation (CSEC) | 1 | 1 | |

| • Family members’ information and history | 10 | 1 | |

| • Co-occurring mental health/SUD problems | 8 | 1 | |

| • Attachment failures | 10 | 1 | |

| Domain 2: Services & Interventions | |||

| 7. | Evidence-based trauma-specific treatment should be widely available/accessible to youth & families | 1–4, 6–10 | 9 |

| 8. | Offer treatment in community-based settings as well as juvenile detention/correctional facilities | 3, 7, 8, 10 | 4 |

| 9. | Provide a continuum of trauma-informed interventions (brief interventions to intensive treatment) | 7, 8, 10 | 3 |

| 10. | Services that teach youth self-regulation skills | 3, 4, 8 | 3 |

| 11. | Strengths-based framework | 1, 4, 8 | 3 |

| 12. | Develop trauma-informed safety plans (triggers, warning signs, coping strategies) with all youth affected by trauma | 7, 8 | 2 |

| 13. | Integrate TIC principles into all services (mental health, substance use, medical) | 3, 8 | 2 |

| Domain 3: Cultural Competence | |||

| 14. | Practices and policies should address the needs of diverse groups of youth and avoid/reduce disparities related to race/ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, developmental level, and SES | 1–3, 8–10 | 6 |

| 15. | Provide gender-specific/responsive interventions and programs | 2, 3, 8 | 3 |

| 16. | Tailor services for LGBTQ youth | 2, 3, 8 | 3 |

| 17. | Tailor services to the age/developmental level of youth | 7, 8 | 2 |

| 18. | Trauma-informed services for commercially sexually exploited children (CSEC) | 1, 2 | 2 |

| 19. | Create small, family style group living facilities for pregnant and parenting girls | 2 | 1 |

| Domain 4: Youth & Family Engagement/Involvement | |||

| 20. | Prioritize youth and family preferences for services | 3, 6–10 | 6 |

| 21. | Provide youth and families with access to positive social support from people of similar backgrounds (e.g., mentors, peer advocates) | 2, 3, 6–8, 10 | 6 |

| 22. | Provide education/service referrals to address parent/caregiver trauma and its impact on the family system | 1, 3, 7, 8 | 4 |

| 23. | Involve youth & families in agency planning (advisory boards, routinely collecting feedback on services) | 6–8, 10 | 4 |

| 24. | Provide tangible resources to reduce barriers to engagement and partnering (bus pass, child care, etc.) | 8 | 1 |

| Domain 5: Workforce Development & Support | |||

| 25. | Training for all staff to increase their understanding of trauma | 1–10 | 10 |

| 26. | Ongoing supervision to ensure that staff implement new approaches with fidelity | 3, 7 | 2 |

| 27. | Training for new hires and refresher trainings | 8 | 1 |

| Recommended topics for training: | |||

| • Trauma-informed care principles/practices | 1, 4, 7–10 | 6 | |

| • Impact of trauma on youth development & behavior | 1, 5–8 | 5 | |

| • Skills for working with trauma-affected youth (i.e., identifying & responding to youth trauma reactions) | 3, 5, 7, 8, 10 | 5 | |

| • Recognize the signs and triggers for traumatic stress reactions | 6–9 | 4 | |

| • Family engagement/empowerment strategies | 3, 5, 7, 10 | 4 | |

| • Ways that juvenile justice involvement can be triggering or re-traumatizing for youth | 4, 5, 7 | 3 | |

| • Trauma-informed treatments/services available in the local community/justice system | 5, 6, 9 | 3 | |

| • Trauma screening | 6, 9 | 2 | |

| • Making appropriate referrals to services | 3, 5 | 2 | |

| • Impact of trauma on youth delinquency | 7, 8 | 2 | |

| • Adolescent development | 5, 10 | 2 | |

| • Specialized Crisis Intervention Team (CIT) training for law enforcement | 5 | 1 | |

| • Family dynamics | 10 | 1 | |

| • Culturally competent care with special populations | 2 | 1 | |

| • Parenting skills | 10 | 1 | |

| 28. | Address traumatic stress reactions among front-line staff (PTSD, secondary/vicarious trauma) | 1, 6–8, 10 | 5 |

| 29. | Education/training to increase staff awareness of the symptoms and causes of staff traumatic stress | 1, 6–8, 10 | 5 |

| 30. | Discuss staff traumatic stress/wellness in supervision and/or team meetings | 1, 7, 8, 10 | 4 |

| 31. | Employee Assistance Programs or referral to outside therapist for counseling to address traumatic stress | 7, 8, 10 | 3 |

| 32. | Teach staff strategies for preventing traumatic stress (self-care, emotion regulation skills) | 8, 10 | 2 |

| 33. | Develop procedure for de-briefing with staff following work-related events that are potentially traumatic (e.g., youth killed, youth or staff assaulted) | 7, 8 | 2 |

| 34. | Consult with outside expert on addressing staff traumatic stress within the organization | 1 | 1 |

| 35. | Create co-worker support opportunities (e.g., peer support groups onsite in agency) | 1 | 1 |

| 36. | Employee recognition (i.e., reinforce staff success) | 7 | 1 |

| 37. | Create agency climate that says seeking help is a sign of strength, not weakness | 7 | 1 |

| 38. | Routinely collect feedback from staff/involve them in agency decision-making | 10 | 1 |

| 39. | Increase staff salaries to increase staff retention (i.e., to provide stability/consistency for youth) | 10 | 1 |

| Domain 6: Promoting a Safe Agency Environment | |||

| 40. | Policies/procedures promote a physically and psychologically safe environment for youth/families and staff | 3, 4, 6–8, 10 | 6 |

| 41. | Restrict/eliminate harsh or coercive practices (e.g., seclusion, physical restraint, shackling, strip searches) | 1–3, 8–10 | 6 |

| 42. | Promote respectful youth-staff interactions | 3, 4, 6, 7 | 4 |

| 43. | Minimize youth exposure to violence or threats from other youth or staff | 3, 7, 8 | 3 |

| 44. | Physical environment is calming, welcoming, and therapeutic | 6, 7, 10 | 3 |

| 45. | Transparent communication with youth/families about agency rules, their rights, and grievance process | 2, 7, 10 | 3 |

| 46. | Structure and predictability (consistent schedule, youth informed in advance of changes) | 4 | 1 |

| 47. | Ensure adequate security in the agency (lighting, cameras, security staff) | 7 | 1 |

| 48. | Use trauma-informed/positive behavior management strategies or systems | 4 | 1 |

| 49. | Create specialized crisis interventions teams | 5 | 1 |

| 50. | Facilities need private rooms for youth who do not feel safe or comfortable sharing a room at night | 10 | 1 |

| 51. | Eliminate uniforms | 10 | 1 |

| Domain 7: Agency Policies, Procedures, & Leadership | |||

| 52. | Incorporate trauma-informed principles into all aspects of agency operations (mission statement, written policies, protocols, procedures) | 7, 8, 10 | 3 |

| 53. | System/agency leadership must embrace a trauma-informed approach and build it into the organizational value system and operational environment | 6, 7 | 2 |

| 54. | Create a task force to lead trauma-informed care initiative with staff from different departments and roles | 7 | 1 |

| Domain 8: Cross-System Collaboration | |||

| 55. | Collaborate with other systems/providers to coordinate care for youth with multi-system involvement | 1, 5, 7, 8, 10 | 5 |

| 56. | Work with community stakeholders to ensure that trauma-informed services are available in all child service systems to address the impact of trauma before youth come into contact with justice system | 3, 5, 7, 8 | 4 |

| 57. | Establish information sharing agreements with other systems or providers that serve justice-involved youth | 7, 8 | 2 |

| Domain 9: Systems-level Policies & Procedures | |||

| 58. | Policies/procedures to minimize justice involvement whenever possible (divert youth to community, keep youth in least restrictive environment, and/or limit transfer to adult court) | 2, 3, 5, 8, 9 | 5 |

| 59. | Policies to require that a youths’ trauma history is used to connect them to services or limit juvenile justice involvement and cannot be used against a youth in court (i.e., as aggravating factor, protection against self-incrimination during court-mandated assessments) | 3, 7–9 | 4 |

| 60. | Policy/Legislation to promote the adoption of TIC by juvenile justice agencies/systems | 3, 7, 9 | 3 |

| 61. | Guarantee legal representation for all trauma-exposed youth accused of a crime | 2, 8 | 2 |

| 62. | Policies to prevent youth from entering status offense or juvenile justice system because of abuse or neglect (e.g., ran away from abusive home, assaulted an abusive parent in self-defense) | 3, 9 | 2 |

| 63. | Appoint independent monitors to ensure that youth in facilities are safe and receiving appropriate services | 2, 3 | 2 |

| 64. | Legislation to ensure that commercially sexually exploited children are treated as victims, not criminals | 1, 2 | 1 |

| 65. | School discipline policies to keep kids in school rather than driving them to justice system | 2 | 1 |

| 66. | Revise mission of juvenile justice to focus on rehabilitation/safety rather than a corrections mission | 10 | 1 |

| Domain 10: Quality Assurance & Evaluation | |||

| 67. | Conduct evaluations and focus on quality improvement | 3, 7, 10 | 3 |

| 68. | Assess effectiveness of trauma-informed services/youth outcomes | 3, 7 | 2 |

| 69. | Monitor for racial disparities/cultural disparities in access to and benefit from trauma-informed services | 3, 7 | 2 |

| 70. | Assess fidelity to evidence-based/trauma-informed practices | 7 | 1 |

| 71. | Assess whether juvenile justice services are being used for youth and families who could benefit from voluntary or preventive services and may not need system involvement at all | 3 | 1 |

1-ABA, 2-Attorney General’s Task Force, 3-Feierman & Ford, 4-Griffin et al., 5-IACP, 6-NCJFCJ, 7-NCMHJJ, 8-NCTSN, 9-Pilnik & Kendall, 10-Rapp.

Total number of publications that included this recommendation

Only eight of the 71 recommendations (11%) were included in the majority of definitions (i.e., n ≥ 6). These recommendations were: universal screening/assessment of youth for trauma-related impairment; providing evidence-based, trauma-specific treatment; practices/policies that address the needs of diverse groups of youth; access to social supports for youth and families; prioritizing youth and family preferences for services; staff training; policies/procedures to promote a safe environment; and eliminating or reducing harsh/coercive practices. More than half of the recommendations (n = 39 or 55%) were included in only one or two definitions with the remaining 24 recommendations (34%) included in three to five definitions.

Clinical Services Recommendations

Domain 1: Screening & assessment

All but one of the publications called for universal screening of youth offenders for trauma-related impairment followed by a comprehensive mental health assessment for youth who screen positive. A smaller number of publications included recommendations about what to screen or assess for (e.g., trauma exposure and/or PTSD symptoms). Only three publications called for the use of assessment tools that have been validated with youth in the juvenile justice system.

Domain 2: Services & interventions

All but one of the publications called for justice systems to make evidence-based, trauma-specific mental health interventions widely available to youth and families involved with the system. Seven different recommendations were given regarding specific services, most commonly offering trauma-specific services to youth in both community-based juvenile justice agencies and detention/correctional facilities (n = 4).

Domain 3: Cultural competence

Six publications recommended policies, procedures, and clinical services/programming that address the needs of diverse groups of youth and avoid or reduce disparities related to race/ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, developmental level, and socioeconomic status. Three publications included recommendations for gender-responsive/specific programming to meet the needs of girls involved in the justice system. Three publications called for services to be tailored for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer youth.

Agency Context Recommendations

Domain 4: Youth & family engagement/involvement

Seven publications included recommendations around promoting youth and family engagement with the justice system. Six publications recommended that agencies/systems provide access to social supports for youth and families. Other common recommendations within this area included: prioritizing youth and family preferences during service planning (n = 6), involving youth/family members in systems evaluation or planning efforts (n = 4), and providing education and/or service referrals to address caregiver trauma and its impact on the family system (n = 4).

Domain 5: Workforce development & support

Staff training on trauma was identified as a core element of TIC in all 10 publications, making it the only unanimous recommendation. A total of 15 different training topics were recommended across the 10 publications. The most frequently recommended topics for training were: trauma-informed care principles or practices (n = 6), specific skills for working with trauma survivors (n = 5), and the impact of trauma on youth development/behavior (n = 5). Five publications recommended agency or system-wide efforts to address work-related traumatic stress reactions among front-line staff. Nine different strategies were identified, most commonly staff education on the signs and causes of work-related PTSD (n = 5) and discussion of work stressors in supervision or team meetings (n = 4).

Domain 6: Promoting a safe agency environment

Six of the publications identified policies and procedures to promote a sense of physical and psychological safety among youth, families, and staff as a core component of TIC. The most common recommendations for creating a safe environment were: restricting/eliminating the use of harsh or coercive practices that may trigger or re-traumatize youth (n = 6) and promoting respectful youth-staff interactions (n = 4).

Domain 7: Agency policies, procedures, & leadership

Three publications recommended that juvenile justice agencies or systems institutionalize their commitment to TIC by embedding principles of trauma-informed care into their written policies and procedures. Additionally, two publications recommended that agency leadership embrace a trauma-informed approach and build into the organizational value system.

System-Level Recommendations

Domain 8: Cross-system collaboration

Five publications called for cross-system collaboration in order to coordinate care with other service systems or providers that work with youth offenders. Four of these definitions recommended working with other community stakeholders to ensure that trauma-informed services/care is available throughout all local child service systems. Additionally, two publications recommended that juvenile justice establish information-sharing agreements with other service systems/providers to facilitate coordination of care for youth involved with multiple systems.

Domain 9: System-level policies & procedures

Five publications recommended system-level policies to minimize youth contact with juvenile justice and/or keep them in the least restrictive environment. Four publications recommended policies to ensure that information about a youth’s trauma history is used to connect them with services and is never used against them in court. Three publications called for policies to promote the adoption of TIC within juvenile justice.

Domain 10: Quality assurance & evaluation

Three publications called for ongoing data collection to evaluate the process and impact of implementing TIC. Recommended areas of focus for such efforts included youth outcomes (n = 2) and monitoring for racial/ethnic disparities in access to TIC and outcomes (n = 2). Notably, only one publication called for ongoing monitoring of staff fidelity to trauma-informed interventions/practices.

Discussion

The current study, to our knowledge, represents the first systematic review of the literature on existing definitions of the core components and practices or policies that comprise trauma-informed care (TIC) for the juvenile justice system. Findings reveal that the bulk of the extant literature consists of studies examining trauma’s impact on youth offenders and theoretical papers outlining the rationale for trauma-informed juvenile justice systems with a far smaller number of publications (10 of the 950 records reviewed or 1%) that actually define the core components of TIC. The 10 publications included definitions/recommendations for the whole system as well as for all major settings/professions within juvenile justice (law enforcement, courts, probation/diversion, correctional/detention facilities). The overarching theme of our review is that the literature offers relative consensus around the core domains but less agreement on the key practices or policies that comprise a trauma-informed approach for juvenile justice. One clear theme is that further refinement of the definition is necessary.

The 10 publications included in the current review yielded a total of 71 different recommendations. While this is a large number that includes a diverse range of practices and policies, we were able to identify 10 broad domains of TIC (e.g., promoting a safe agency environment, workforce development/support) that encompass all of the recommendations. Furthermore, these domains are largely consistent with those found in definitions of TIC for other service systems (Hopper et al., 2010; Raja et al., 2015). This suggests a reasonable level of conceptual coherence around the core domains of a trauma-informed juvenile justice system. However, we found much less agreement around the specific interventions or policies that were identified as essential components of TIC for juvenile justice. Only 8 of the 71 recommended practices or policies (11%) were included in the majority of publications, while most recommendations (n = 39 or 55%) were included in only one or two publications. This suggests that more work is needed to translate the broader domains of TIC into particular interventions or policies, which is also the case for efforts to define TIC in other child service systems (e.g., Wall et al., 2016).

Another key gap in the extant literature is the limited discussion of how to implement particular practices or policies and the potential barriers at the agency or systems-level. For example, while there is unanimous agreement that all staff should undergo training on trauma, there was much less consensus around the specific areas that training should cover. Fifteen different content areas for training were proposed, ranging from understanding the impact of trauma on youth development to family engagement strategies. Surprisingly, just over half of the publications (6 of 10) recommended training in specific skills for working effectively with traumatized youth. Teaching front-line staff to recognize when youth are experiencing a trauma reaction will have little impact on youth-staff interactions unless it is supplemented with training in specific skills for responding to such situations (e.g., trauma-informed de-escalation or engagement strategies). Additionally, only one of the publications discussed the need for ongoing supervision to assist staff in mastering and applying newly learned knowledge or skills to their work, an important omission given that training alone has been shown ineffective in helping staff achieve fidelity to evidence-based practices (Beidas & Kendall, 2010). The 10 publications that we reviewed represent the most detailed, published recommendations for TIC in juvenile justice, yet they rarely addressed such nuances. One exception is the National Center for Mental Health and Juvenile Justice’s (2015) report on creating trauma-informed juvenile diversion programs, which identified implementation issues in several areas (e.g., interventions, funding, quality assurance) and illustrated with real-world case examples.

Notably, only five publications recommended agency-level efforts to prevent work-related traumatic stress among front-line staff, which is consistently identified as a core component of TIC in definitions for other service systems (Hopper et al., 2010). This is a troubling omission given that work-related traumatic stress symptoms are prevalent and associated with impaired job performance among front-line staff (e.g., attorneys, probation/ correctional officers, law enforcement) in the justice system (Denhof & Spinaris, 2013; Levin et al., 2011; Skogstad et al., 2013). Additionally, several groups of justice system professionals have expressed their desire for greater organizational support around these matters (Donisch et al., 2016; Knowlton, 2015; Severson & Pettus-Davis, 2013).

Future Directions for Research

The final aim of the current review was to propose directions for future research in order to develop a consensus-based definition of TIC for juvenile justice. We identified just 10 publications from a small number of stakeholders and it is unclear whether their views on the core components of TIC are representative of the larger field of juvenile justice professionals. Accordingly, we recommend surveys with nationally-representative samples of front-line staff and system administrators to explore their perceptions of the core components of TIC. It would also be useful to assess how widely each of these practices has been adopted in juvenile justice systems across the country. Hanson and Lang (2016) recently published the findings of a similar survey of providers from multiple service systems, including juvenile justice, and noted the dearth of published research focused on defining or validating the core concepts of TIC.

A key question emanating from this review is which, if any, of these various recommendations will contribute to positive outcomes for the juvenile justice system. The answer requires a careful examination of published empirical studies to determine which practices or policies, currently in use, produce meaningful improvement in outcomes for youth, their families, staff, and the broader agency environment. Additionally, prospective studies are needed to evaluate the comparative effectiveness of different trauma-informed practices or policies. For example, Borckardt et al. (2011) examined the effectiveness of four TIC components (staff training, policy changes, modifications to physical environment, client-centered treatment planning) for reducing the use of seclusion and physical restraint in inpatient psychiatric hospital settings by randomly assigning five inpatient units to implement these components in different order. Such research can help refine the core definitional elements that should comprise a unified theory of TIC for juvenile justice.

Limitations

The primary limitation of the current study was our approach to coding, categorizing, and describing the definitions/recommendations for TIC. Although we followed established guidelines for systematic reviews (Shamseer et al., 2015), there are different approaches we could have taken to our narrative synthesis of the findings. For example, we did not analyze, in detail, the recommendations for particular TIC models, training curriculums, or interventions. Additionally, our decisions around assigning recommendations to one of the 10 broader domains, and even the number and names of these domains, were admittedly subjective. However, this is a minor limitation as we were more interested in identifying specific recommended practices or policies than broader domains or principles of a trauma-informed approach for juvenile justice.

Conclusions

The growth in recognition of the importance of trauma-informed care represents an unprecedented opportunity to improve our nation’s juvenile justice system and dramatically reduce the number of young lives damaged each year through harsh and ineffective responses to youth crime. However, to maximize this opportunity it is necessary to first develop a consensus-based understanding of what constitutes a trauma-informed approach within juvenile justice. This process should be informed by all key stakeholders, as well as empirical evidence on the impact of implementing particular practices and policies within the justice system.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K23MH104697. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The authors wish to thank Ms. Raquel Rose for her contributions to the systematic review as well as two anonymous reviewers for their feedback on an earlier version of this manuscript.

Contributor Information

Christopher Edward Branson, New York University School of Medicine.

Carly Lyn Baetz, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

Sarah McCue Horwitz, New York University School of Medicine.

Kimberly Eaton Hoagwood, New York University School of Medicine.

References

- Abram KM, Teplin LA, Charles DR, Longworth SL, McClelland GM, Dulcan MK. Posttraumatic stress disorder and trauma in youth in juvenile detention. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2004;61:403–410. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.4.403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Association of Children’s Residential Centers. Trauma-informed care in residential treatment. Residential Treatment for Children & Youth. 2014;31:97–104. [Google Scholar]

- *.American Bar Association. ABA policy on trauma-informed advocacy for children and youth. Chicago: Author; 2014. Retrieved from http://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/administrative/child_law/ABA Policy on Trauma-Informed Advocacy.authcheckdam.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- *.Attorney General’s National Task Force on Children Exposed to Violence. Defending childhood: Report of the Attorney General’s National Task Force on Children Exposed to Violence. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice; 2012. Retrieved from https://www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/defendingchildhood/cev-rpt-full.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Beidas RS, Kendall PC. Training therapists in evidence-based practice: A critical review of studies from a systems-contextual perspective. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2010;17:1–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.2009.01187.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black PJ, Woodworth M, Tremblay M, Carpenter T. A review of trauma-informed treatment for adolescents. Canadian Psychology. 2012;53:192–203. [Google Scholar]

- Borckardt JJ, Madan A, Grubaugh AL, Danielson CK, Pelic CG, Hardesty SJ, Frueh BC. Systematic investigation of initiatives to reduce seclusion and restraint in a state psychiatric hospital. Psychiatric Services. 2011;62:477–483. doi: 10.1176/ps.62.5.pss6205_0477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burrell S. Trauma and the environment of care in juvenile institutions. Los Angeles, CA and Durham, NC: National Center for Child Traumatic Stress; 2013. Retrieved from http://www.nctsn.org/resources/topics/juvenile-justice-system. [Google Scholar]

- Cauffman E, Monahan KC, Thomas AG. Pathways to persistence: Female offending from 14 to 25. Journal of Developmental and Life-Course Criminology. 2015;1:236–268. [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain J, Miller MK. Stress in the courtroom: Call for research. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law. 2008;15:237–250. [Google Scholar]

- Crosby SD. Trauma-informed approaches to juvenile justice: A critical race perspective. Juvenile & Family Court Journal. 2016;67:5–18. [Google Scholar]

- DeHart D, Moran R. Poly-victimization among girls in the justice system: Trajectories of risk and associations to juvenile offending. Violence Against Women. 2015;21:291–312. doi: 10.1177/1077801214568355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denhof MD, Spinaris CG. Depression, PTSD, and comorbidity in United States corrections professionals: Prevalence and impact on health. Florence, CO: Desert Waters Correctional Outreach; 2013. Retrieved from http://desertwaters.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/Comorbidity_Study_6-18-13.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Dierkhising CB, Ko S, Goldman JH. Trauma-informed juvenile justice roundtable: Current issues and new directions in creating trauma-informed juvenile justice systems. Los Angeles, CA and Durham, NC: National Center for Child Traumatic Stress; 2013. Retrieved from http://www.nctsn.org/resources/topics/juvenile-justice-system. [Google Scholar]

- Dierkhising CB, Lane A, Natsuaki MN. Victims behind bars: A preliminary study of abuse during juvenile incarceration and post-release social and emotional functioning. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law. 2014;20:181–190. [Google Scholar]

- Donisch K, Bray C, Gewirtz A. Child welfare, juvenile justice, mental health, and education providers’ conceptualizations of trauma-informed practice. Child Maltreatment. 2016;21:125–134. doi: 10.1177/1077559516633304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott DE, Bjelajac P, Fallot RD, Markoff LS, Reed BG. Trauma-informed or trauma-denied: Principles and implementation of trauma-informed services for women. Journal of Community Psychology. 2005;33:461–477. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Partners Committee on Women and Trauma. Trauma-informed approaches: Federal activities and initiatives. Washington, DC: Author; 2013. Retrieved from http://static.nicic.gov/Library/027657.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Feierman J, Fine L. Trauma and resilience: A new look at legal advocacy for youth in the juvenile justice and child welfare systems. Philadelphia, PA: Juvenile Law Center; 2014. Retrieved from http://www.jlc.org/resources/publications/trauma-and-resilience. [Google Scholar]

- *.Feierman J, Ford JD. Trauma-informed juvenile justice systems and approaches. In: Heilbrun K, editor. APA handbook of psychology and juvenile justice. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2016. pp. 545–573. [Google Scholar]

- Ford JD. Posttraumatic stress disorder among youth involved in juvenile justice. In: Grigorenko EL, editor. Handbook of juvenile forensic psychology and psychiatry. Boston, MA: Springer US; 2012. pp. 485–501. [Google Scholar]

- Ford JD, Chapman J, Mack JM, Pearson G. Pathways from traumatic child victimization to delinquency: Implications for juvenile and permanency court proceedings and decisions. Juvenile & Family Court Journal. 2006;57:13–26. [Google Scholar]

- Ford JD, Hartman K, Hawke J, Chapman JF. Traumatic victimization, posttraumatic stress disorder, suicidal ideation, and substance abuse risk among juvenile justice-involved youth. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma. 2008;1:75–92. [Google Scholar]

- Geller A, Fagan J, Tyler T, Link BG. Aggressive policing and the mental health of young urban men. American Journal of Public Health. 2014;104:2321–2327. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Griffin G, Germain EJ, Wilkerson RG. Using a trauma-informed approach in juvenile justice institutions. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma. 2012;5:271–283. [Google Scholar]

- Hanson RF, Lang J. A critical look at trauma-informed care among agencies and systems serving maltreated youth and their families. Child Maltreatment. 2016;21:95–100. doi: 10.1177/1077559516635274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris M, Fallot RD. Envisioning a trauma-informed service system: A vital paradigm shift. New Directions for Mental Health Services. 2001;2001:3–22. doi: 10.1002/yd.23320018903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynie DL, Petts RJ, Maimon D, Piquero AR. Exposure to violence in adolescence and precocious role exits. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2009;38:269–286. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9343-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopper EK, Bassuk EL, Olivet J. Shelter from the storm: Trauma-informed care in homelessness services settings. The Open Health Services and Policy Journal. 2010;3:80–100. [Google Scholar]

- Igelman RS, Ryan BE, Gilbert AM, Bashant JC, North K. Best practices for serving traumatized children and families. Juvenile & Family Court Journal. 2008;59:35–48. [Google Scholar]

- *.International Association of Chiefs of Police. Law enforcement’s leadership role in juvenile justice reform: Actionable recommendations for practice & policy. Alexandria, VA: Author; 2014. Retrieved from http://www.theiacp.org/jjsummitreport. [Google Scholar]

- Kerig PK. Trauma-informed assessment and intervention. Los Angeles, CA and Durham, NC: National Center for Child Traumatic Stress; 2013. Retrieved from http://www.nctsn.org/resources/topics/juvenile-justice-system. [Google Scholar]

- Kerig PK, Becker SP. From internalizing to externalizing: Theoretical models of the processes linking PTSD to juvenile delinquency. In: Egan SJ, editor. Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD): Causes, symptoms and treatment. Hauppauge, NY: Nova Science Publishers; 2010. pp. 33–78. [Google Scholar]

- Knowlton NA. The modern family court judge: Knowledge, qualities, and skills for success. Family Court Review. 2015;53:203–216. [Google Scholar]

- Ko SJ, Ford JD, Kassam-Adams N, Berkowitz SJ, Wilson C, Wong M, Layne CM. Creating trauma-informed systems: Child welfare, education, first responders, health care, juvenile justice. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2008;39:396–404. [Google Scholar]

- Kunst MJJ. Working in prisons: A critical review of stress in the occupation of correctional officers. In: Langan-Fox J, Cooper CL, editors. Handbook of stress in the occupations. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar; 2011. pp. 241–283. [Google Scholar]

- Lacey C. Racial disparities and the juvenile justice system: A legacy of trauma. Los Angeles, CA and Durham, NC: National Center for Child Traumatic Stress; 2013. Retrieved from http://www.nctsn.org/resources/topics/juvenile-justice-system. [Google Scholar]

- Levin AP, Albert L, Besser A, Smith D, Zelenski A, Rosenkranz S, Neria Y. Secondary traumatic stress in attorneys and their administrative support staff working with trauma-exposed clients. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2011;199:946–955. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3182392c26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Green JG, Gruber MJ, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, Kessler RC. Childhood adversities and first onset of psychiatric disorders in a national sample of US adolescents. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2012;69:1151–1160. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.2277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller EA, Green AE, Fettes DL, Aarons GA. Prevalence of maltreatment among youths in public sectors of care. Child Maltreatment. 2011;16:196–204. doi: 10.1177/1077559511415091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors. NASMHPD position statement on services and supports to trauma survivors. Alexandria, VA: Author; 2005. Retrieved from http://www.nasmhpd.org/sites/default/files/NASMHPD TRAUMA Positon statementFinal.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Mental Health and Juvenile Justice. What constitutes trauma-informed services within juvenile justice systems? Retrieved from http://cfc.ncmhjj.com/resources/trauma-among-youth-in-the-juvenile-justice-system/what-constitutes-trauma-informed-services-within-juvenile-justice-systems/ (n.d.)

- *.National Center for Mental Health and Juvenile Justice, & Technical Assistance Collaborative. Strengthening our future: Key elements to developing a trauma-informed juvenile justice diversion program for youth with behavioral health conditions. Delmar, NY: Policy Research Associates, Inc; 2015. Retrieved from http://www.ncmhjj.com/strengthening-our-future/ [Google Scholar]

- *.National Child Traumatic Stress Network. Essential elements of a trauma-informed juvenile justice system. Los Angeles, CA and Durham, NC: National Center for Child Traumatic Stress; 2016. Retrieved from http://www.nctsn.org/sites/default/files/assets/pdfs/jj_ee_final.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges. Trauma informed system of care. Retrieved from http://www.ncjfcj.org/our-work/trauma-informed-system-care (n.d.)

- *.National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges. Trauma-informed juvenile and family courts. NCJFCJ Resolution. Reno, NV: Author; 2015. Retrieved from http://www.ncjfcj.org/sites/default/files/Resolution Trauma Informed Courts_July2015.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- National Prevention Council. National prevention strategy. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General; 2011. Retrieved from http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/priorities/prevention/strategy/report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Palinkas LA. Qualitative and mixed methods in mental health services and implementation research. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2014;43:851–861. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2014.910791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Pilnik L, Kendall JR. Victimization and trauma experienced by children and youth: Implications for legal advocates (Issue Brief No. 7) North Bethesda, MD: U.S. Department of Justice; 2012. Retrieved from http://www.ojjdp.gov/programs/safestart/IB7_VictimizationTrauma_LegalAdvocates.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Rainville C. Understanding secondary trauma: A guide for lawyers working with child victims. ABA Child Law Practice. 2015;34:133–136. Retrieved from www.childlawpractice.org. [Google Scholar]

- Raja S, Hasnain M, Hoersch M, Gove-Yin S, Rajagopalan C. Trauma informed care in medicine: Current knowledge and future research directions. Family & Community Health. 2015;38:216–226. doi: 10.1097/FCH.0000000000000071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Rapp L. Delinquent-victim youth—Adapting a trauma-informed approach for the juvenile justice system. Journal of Evidence-Informed Social Work. Advance online publication. 2016 doi: 10.1080/23761407.2016.1166844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozzell L. The role of family engagement in creating trauma-informed juvenile justice systems. Los Angeles, CA and Durham, NC: National Center for Child Traumatic Stress; 2013. Retrieved from http://www.nctsn.org/resources/topics/juvenile-justice-system. [Google Scholar]

- Severson M, Pettus-Davis C. Parole officers’ experiences of the symptoms of secondary trauma in the supervision of sex offenders. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology. 2013;57:5–24. doi: 10.1177/0306624X11422696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M. The PRISMA-P GroupPreferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: Elaboration and explanation. British Medical Journal. 2015;350:7647. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g7647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sickmund M. NCJFCJ resolution regarding trauma-informed juvenile and family courts. Juvenile & Family Court Journal. 2016;67:49–52. [Google Scholar]

- Skogstad M, Skorstad M, Lie A, Conradi HS, Heir T, Weisæth L. Work-related post-traumatic stress disorder. Occupational Medicine. 2013;63:175–182. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqt003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart M. Cross-system collaboration. Los Angeles, CA and Durham, NC: National Center for Child Traumatic Stress; 2013. Retrieved from http://www.nctsn.org/resources/topics/juvenile-justice-system. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. SAMHSA’s concept of trauma and guidance for a trauma-informed approach. HHS Publication No. (SMA) Rockville, MD: Author; 2014. pp. 14–4884. Retrieved from http://store.samhsa.gov/shin/content/SMA14-4884/SMA14-4884.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Wall L, Higgins D, Hunter C. Trauma-informed care in child/family welfare services. Melbourne, VIC Australia: Australian Institute of Family Studies; 2016. Retrieved from https://aifs.gov.au/cfca/publications/trauma-informed-care-child-family-welfare-services. [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman GA, McReynolds LS. Contributors to traumatic exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder in juvenile justice youths. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2011;24:422–429. doi: 10.1002/jts.20664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willms DG, Best JA, Taylor DW, Gilbert JR, Wilson MC, Lindsay EA, Singer J. A systematic approach for using qualitative methods in primary prevention research. Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 1990;4:391–409. [Google Scholar]

- Wolff KT, Baglivio MT, Piquero AR. The relationship between adverse childhood experiences and recidivism in a sample of juvenile offenders in community-based treatment. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology. 2015;43:1–33. doi: 10.1177/0306624X15613992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]