Abstract

3D printing is at the crossroads of printer and materials engineering; non-invasive diagnostic imaging; computer aided design (CAD); and structural heart intervention. Cardiovascular applications of this technology development include the use of patient-specific 3D models for medical teaching, exploration of valve and vessel function, surgical and catheter-based procedural planning, and early work in designing and refining the latest innovations in percutaneous structural devices. In this review we discuss the methods and materials being used for 3D printing today. We discuss the basic principles of clinical image segmentation including co-registration of multiple imaging datasets to create an anatomic model of interest. With applications in congenital heart disease, coronary artery disease, and in surgical and catheter-based structural disease – 3D printing is a new tool that is challenging how we image, plan, and carry out cardiovascular interventions.

Keywords: 3D printed modeling, mitral valve apparatus, aortic valve, congenital heart defects, coronary arteries, 3D print materials

Introduction

Three dimensional (3D) printing is a fabrication technique used to transform digital objects into physical models. Also known as additive manufacturing, the technique builds structures of arbitrary geometry by depositing material in successive layers based on a specific digital design. Several different methods exist to accomplish this type of fabrication and many have recently been used to create specific cardiac structural pathologies. While the use of 3D printing technology in cardiovascular medicine is still a relatively new development, advancement within this discipline is occurring at such a rapid rate that a contemporary review is warranted. In this review we address the 3D printing technologies with relevance to cardiovascular medicine and discuss the principles of clinical image segmentation. We also present several recently reported applications of 3D printing, and discuss the unresolved issues and future directions of this emerging technology.

Printing Technology

The first 3D printing technology was introduced by Charles Hull in 1986(1) and the industry has grown to now encompass many different manufacturing technologies. There are several 3D printing technologies with promising applications in medicine. Stereolithography fabricates a solid object from a photopolymeric resin using digitally guided ultra violet (UV) laser light (some new versions use visible light) to harden the surface layer of the polymer liquid. Fused deposition modeling creates a 3D structure by extruding melted thermoplastic filaments layer by layer along with a physical support material that is later dissolved away. Selective laser melting creates strong parts of fused metal or ceramic powder using a high-power laser beam and is also preferred for building functional prototypes or medical implants such as facial bone or sternal bone replacements.(2, 3) PolyJet technology creates 3D prints through a process of jetting thin layers of liquid photopolymers that are instantly hardened using UV light and can incorporate multiple-materials and colors simultaneously. PolyJet is capable of producing highly complex models with smooth surfaces and thin walls (down to a resolution of 0.016 mm)(4) and is a commonly used technique for the fabrication of flexible, patient-specific anatomical models that combine several different materials. For the creation of cardiovascular models, the 3D printing method of choice is based upon the required complexity, durability, and desired surface quality of the model.

The creation of a patient-specific 3D model begins with clinical imaging. An Imaging dataset must be volumetric which limits the modalities to ECG-gated computer tomography (CT), volumetric 3D echocardiography, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Volumetric 3D echocardiography is an attractive data source because it is abundantly available, relatively low-cost, and lacks ionizing radiation. For models of clearly imaged cardiac structures, such as ventricular chambers and valve leaflets, a 3D transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) data source may be sufficient to create a 3D patient-specific model. However, ultrasound based imaging is subject to artifact and unique limitations such as anatomic data loss within an ultrasound “shadow.” To date, CT has been the principle imaging modality for 3D printing, because CT imaging can provide sub-millimeter tissue resolution, clearly identify bone and pathologic calcium deposition, and is a commonly acquired imaging method before surgical or other structural interventions. In addition to excellent spatial resolution, CT is able to image patients with pacemakers, pacemaker wires, and metal implants that are not compatible with MRI scanning. In contrast, MRI can acquire high-resolution images without ionizing radiation and distinguish tissue composition without iodinated contrast media. MRI images have been used for 3D print modeling of congenital heart chambers and vasculature and for the reconstructive modeling of intra-cardiac tumors. However, the spatial resolution of MRI is generally lower than CT, which limits its use for the evaluation of coronary arteries or the small morphological features within heart valve complexes.

Image Data Segmentation

Image segmentation is the process of converting the 3D anatomical information obtained by CT, MRI or 3D echocardiography volumetric imaging datasets into a 3D patient-specific digital model of the target anatomic structures. Increasing interest in anatomical modeling and the growing need for personalized structural heart interventions has encouraged the evolution of segmentation techniques. Initially, segmentation was based on CT images only,(5-9) however more recently MRI images have been utilized to replicate congenital heart and systemic vasculature disorders.(10-14) The feasibility of reconstructing the mitral leaflets and annulus from 3D TEE images has been demonstrated by multiple investigators,(1, 15-20) and efforts to combine echocardiographic data acquired from multiple views or echocardiographic data combined with CT data have been reported.(19, 21)

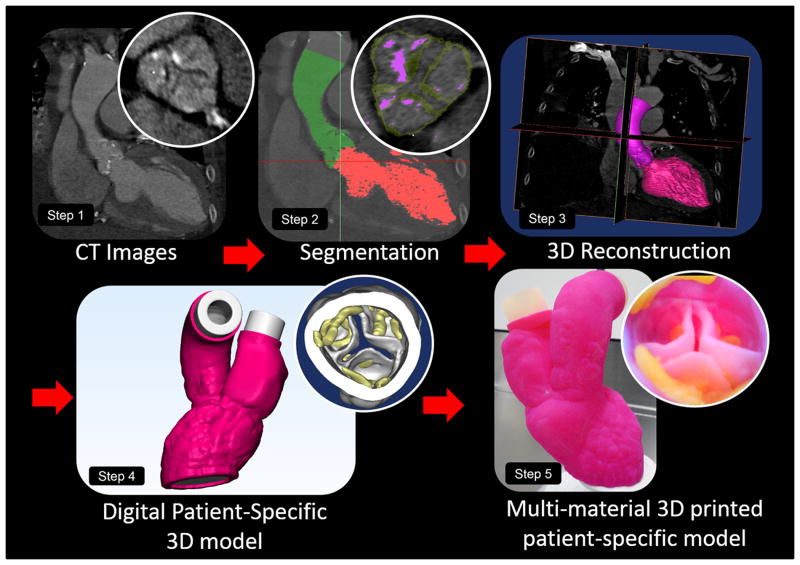

Segmentation involves several steps illustrated in Figure 1. Prior to segmentation, the acquired imaging dataset is exported into a digital imaging and communication in medicine (DICOM) format (3D TEE images are converted into Cartesian DICOM format). From the DICOM dataset, the target anatomic geometry is identified and segmented based on the threshold intensity of pixels in the grey-scale 2D image projections (axial, sagittal and coronal). Segmentation masks are created such that pixels with the same intensity range are grouped and assigned to be printed using a single material (Step 2). Segmentation masks are converted into 3D digital models (Step 3) using rendering techniques, and these patient-specific 3D digital models are saved as a stereolithography (STL) file. Frequently, this 3D digital model may be further modified within computer-aided design (CAD) software where adjustments can be made to reflect the purpose of the 3D printed model (e.g. color coding a region of interest; texturing blended-materials; or adding coupling components for evaluation of the 3D printed model within a flow loop).(19) In general the spatial resolution afforded by TEE is adequate for many 3D modeling purposes, however, the anatomic resolution can be further improved by combining ultrasound datasets acquired from different imaging perspectives. For example, a deep trans-gastric TEE image window of the mitral valve apparatus including the papillary muscles can be digitally combined with data from a mid-esophageal view of the mitral leaflets to create a more complete dataset of the entire mitral valve complex.(19) In addition, segmentation can be enhanced by the digital co-registration of DICOM data from complementary imaging modalities (e.g. TEE visualization of the chordae tendineae combined with CT delineation of the mitral annular calcification). The co-registration is based on discreet anatomy or pathoanatomy that is present in both DICOM datasets such as focal calcification or prosthetic material. In short, the segmentation step describes the identification of the region of interest and may include the addition of anatomic data from more than one imaging source. When segmentation is complete, the final digital model is saved as a STL file within the CAD based software and exported for 3D printing.

Figure 1.

3D printed modeling of patient-specific anatomy. Step 1: CT imaging dataset used for image processing. Step 2: Segmentation process and creation of segmentation mask. Step 3: Converting segmentation mask into 3D digital patient-specific model. Step 4: Adjusted digital 3D patient-specific model suitable for implantation in flow loop and medical imaging acquisition. Step 5: 3D printed multi-material patient-specific model.

There are several commercial software packages, as well as open-source freeware platforms, that can be used for the patient-specific image segmentation.(22-25) The desired features of the model and the type of clinical imaging data used will generally dictate the choice of segmentation software. The source of the DICOM data (CT, MRI, or echo), desired complexity of the patient-specific model, and extent of operator experience with the software may greatly influence the time required for image segmentation. For example, a relatively simple segmentation of a uniform vascular structure, such as a segment of the aorta, might be completed within 20 minutes. However, the complex segmentation of multiple anatomic elements to be printed with a combination of different colors and materials might take up to 12 hours, even by an experienced operator.

Cardiovascular Applications

3D printed patient-specific models can be created for a number of different applications, including: creation of anatomic teaching tools, development of functional models to investigate intracardiac flow; creation of deformable blended material models for complex procedural planning, and increasingly, patient-specific models are being deployed to assist efforts to create or refine intra-cardiac devices.

i) Teaching tools

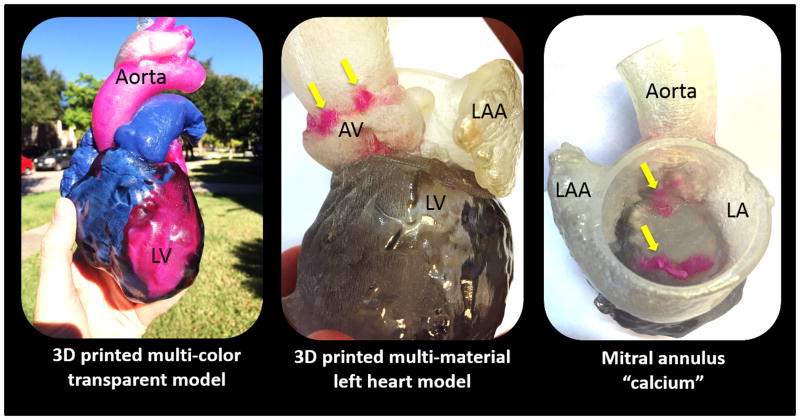

An early application of 3D print modeling was to create models for anatomic teaching or demonstration. Like the plastic heart models familiar to most health care professionals, a 3D printed model can rapidly convey a complex anatomic arrangement, but has the added value of also depicting patient-specific anatomic pathology. Such models can be instructional for the teaching of medical professionals about normal and abnormal structural relationships; and even to help the lay public better understand certain structural heart conditions. Patient-specific models of congenital heart defects have been used for critical-care training of residents, and nurses, and have shown the potential to enhance the communication between cardiologist and patients.(26, 27) Examples include instructional models depicting congenital heart defects, valve stenosis, and catheter-based valve implantation or repair procedures. Increasingly, these 3D models can be constructed with particular colors, variable material hardness, and even layered texturing if needed to convey sophisticated or unusual cardiovascular pathology (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Multi-material and multi-colored patient-specific 3D printed heart for educational purposes and communication with patients. Yellow arrows indicate regions 3D printed (in pink) to replicate calcium depositions within both the aortic valve (center panel) and mitral valve (right panel).

ii) Functional flow models

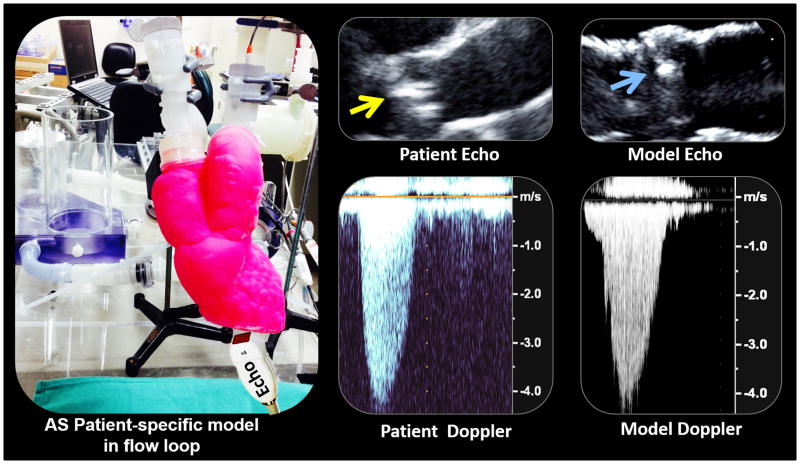

Patient-specific 3D models of aortic valve dysfunction can be readily created by combining the technologies of high-spatial resolution CT, CAD software, and multi-material 3D printing. Aortic valve dysfunction is a spectrum of conditions that have recently been replicated using 3D printing and coupled to a flow phantom. Since severe aortic valve stenosis (AS) represents a relatively static valve configuration, a CT dataset can acquire the patient-specific anatomic detail of the aortic root including the valve orifice area and regional calcium deposition. A recent report described the creation of eight patient-specific multi-material 3D models of severe AS and the performance of a functional assessment of each model under different in vitro flow conditions. Each model replicated well the specific anatomic geometry of degenerative severe AS, with a faithful reproduction of calcium deposition, cusp thickening, and valve orifice shape. The functional evaluation of each model by Doppler and catheter-based methods also replicated the patient-specific AS severity (Figure 3, supplemental Video 1) and suggested that the calculated aortic valve area may not always be a fixed value. For some patients, the valve orifice area of the functional model varied with increasing flow volume. Such patient-specific functional models may provide a controlled and reproducible testing environment with quantitation of flow under pre-specified conditions, with potential applications including the examination of low flow, low gradient AS conditions; or the validation of 4D cardiac MRI methods to quantify trans-valvular flow volume.

Figure 3.

Functional modeling of patient-specific aortic stenosis. When coupled to a flow loop the echocardiographic image and hemodynamic profile of severe stenosis are replicated. Focal calcification within the echocardiographic image of the patient (yellow arrow) and the patient's model (blue arrow) are indicated. Adapted from Maragiannis et al (9) with permission.

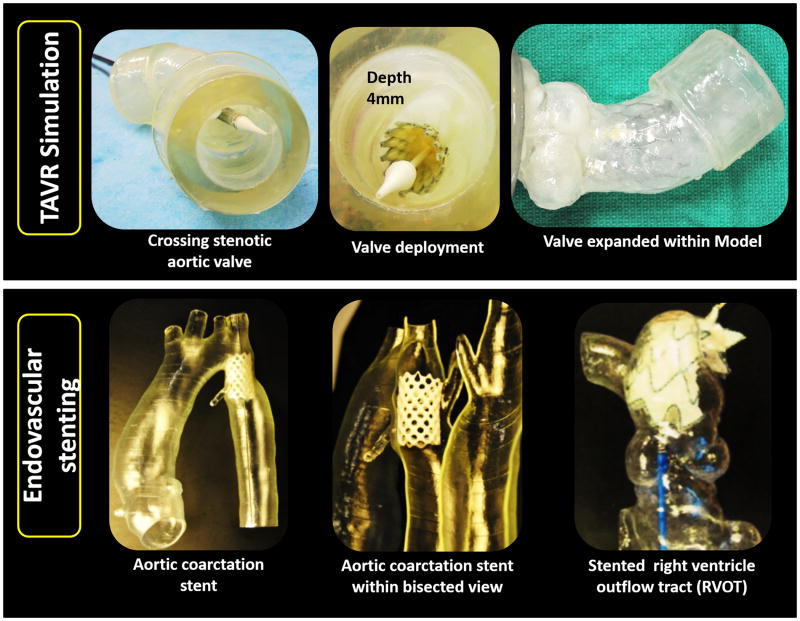

Patient-specific modeling of the aortic valve in diastole has also been used to replicate aortic valve regurgitation and compared to clinical Doppler measures of aortic regurgitation severity replicated in vitro.(28) More recently, patient-specific models of the aortic valve and aortic root complex have been utilized effectively for the performance of in vitro or bench-top trans-catheter aortic valve implantation (TAVR). These constructs allow exploration of the patient-specific features that influence the performance of a trans-catheter deployed prosthetic heart valves. Such models may be especially useful for evaluating clinically challenging situations such as the non-invasive quantification of paravalvular regurgitation severity under controlled flow conditions or for the planned deployment of endovascular stents. (Figure 4).(9)

Figure 4.

Transcatheter valve and stent implantations within patient-specific models. Bench-top TAVR performed within a model of aortic valve stenosis (upper panel). Endovascular stenting within models of aortic coarctation and a pulmonary artery (lower panel – images courtesy of Dr. Giovanni Biglino).

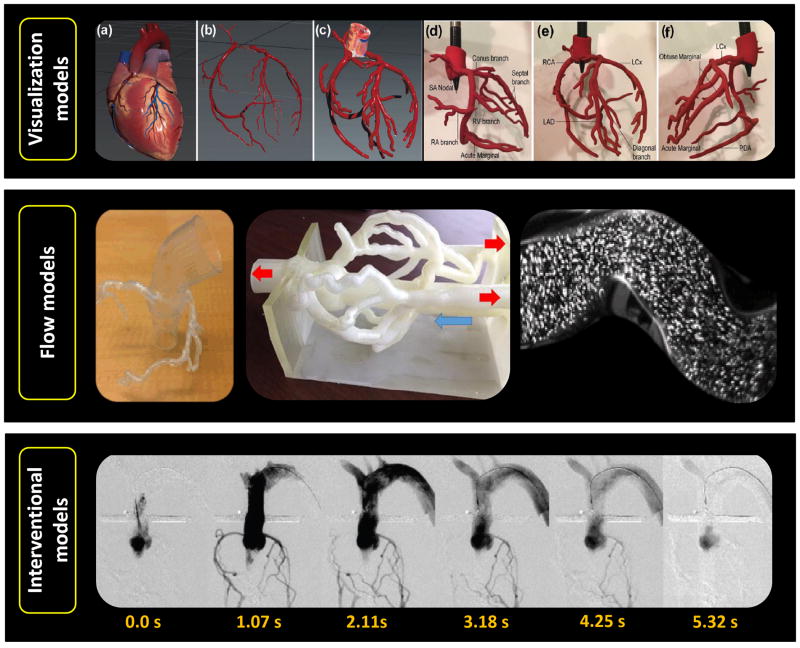

In addition to functional valve replication, the modeling of the coronary artery bed for several different applications has been recently reported. Javan et al. demonstrated that a variety of 3D print models were ideal for coronary visualization (Figure 5).(29) 3D printing of coronary structures can enable visualization of stenotic regions, which may serve as a bench top tool to prepare and/or practice interventional procedures within a pulsatile flow loop environment. The coronary artery tree can be clearly defined by gated-CT methods and when 3D printed in the diastolic phase, these models can be coupled to a flow loop to replicate epicardial coronary perfusion.(30) Such models can provide a reference standard for testing of novel diagnostic measures (e.g. CT-derived fractional flow reserve, FFR) against a controlled in vitro forward flow gold standard.(31) Using 3D printed coronary-like vessels, which were fabricated using a clear rigid material (Veroclear, Stratasys), Kolli et al. showed that FFR decreased as a function of aortic pressure. This relationship was established using a set of idealized 3D printed vessels with systematically placed stenotic regions that varied from 30% to 70%, resulting in absolute decreases in FFR of 0.03 to 0.2, respectively. This work demonstrates how 3D printing can recapitulate aspects of coronary flow in a quantitative and systematic manner, allowing standard diagnostic measures to be evaluated.

Figure 5.

3D printed coronary models. Visualization models - Rigid and solid structures segmented from clinical data used to visualize paths and geometry of epicardial coronary arteries (top panel (adapted from Jovan et al with permission).(29) Flow models - Hollow structures are used to allow flow of liquids and fluorescent particles to quantitatively asses hemodynamics of coronary vessels (mid panel). Interventional models - Hollow structures facilitating interventional procedures (e.g. angiography), (bottom pane, adapted from Russ et al with permission).(32)

Furthermore, when models are printed from optically transparent materials, techniques such as particle image velocimetry (PIV) allow for direct visualization of complex flow dynamics (Figure 5). In addition to flow studies, these functional models can be used to simulate interventional procedures.(32) Figure 5 shows a simulation angiogram. Beyond this, these models also have the potential to simulate devices such as coronary stents, (e.g. drug-eluting or bioresorbable), which can be readily evaluated within this patient-specific coronary bed. (Figure 5)

iii) Procedural planning

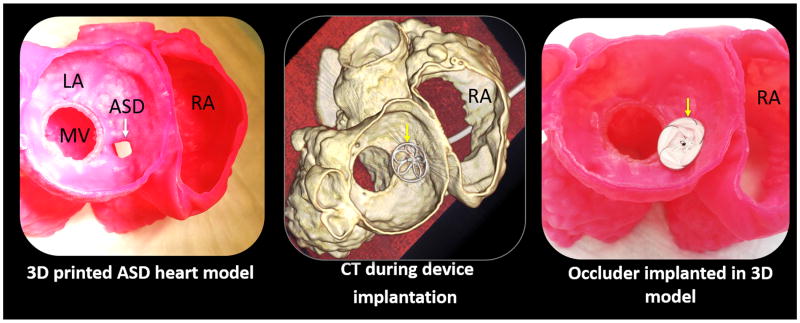

Congenital cardiovascular diseases are often associated with complex and unique geometry that can be very difficult to fully appreciate from 2D CT, MRI or echochardiographic images.(1) As such, 3D printed modeling may play a key role to provide a more comprehensive understanding and functional evaluation of various congenital heart conditions. Recent applications of 3D printed congenital heart models have included; interventional preoperative planning and simulations;(33-38) use of sterilized models during surgical procedures for enhanced structural orientation;(11, 34, 39, 40) functional, patient-specific hemodynamic evaluations; and testing of novel procedural pathways.(10, 41) A broad range of complex congenital heart anatomies have been reconstructed and 3D printed to enhance surgical planning including: double-outlet right ventricle; (26, 42) atrial septal defect (ASD) and ventricular septal defect (VSD);(18, 38, 43, 44) Tetralogy of Fallot(35, 45) as well as hypolastic left heart syndrome.(12, 27, 36) Moreover it has been shown that 3D printed models may assist with the accuracy of ventricular assist device (VAD) cannula placement in patients with congenital heart disease.(42) Detailed reviews of cardiac congenital 3D printed modeling have recently been published. (1, 37, 46) A patient-specific 3D printed model used for pre-procedural planning of a catheter-based ASD closure is shown in figure 6. In this instance, cone-beam CT images were acquired to assist in pre-procedural planning (supplemental Video 2). In this instance such extensive pre-procedural planning was required to ensure that an ASD occluder device would not interfere with the function of previously implanted bioprosthetic aortic and mitral valves. In another example, a previously stented aortic coarctation with an abnormal subclavian artery originating from the stent site was 3D printed prior to a repeat intervention. (figure 4) (36).

Figure 6.

Pre-procedural planning of catheter-based closure of an atrial septal defect (ASD). 3D printed model of an ASD imaged by computer tomorgraphy (CT)(top left); 3D printed model with bench-top implanted septal occluder device (top right); CT scan of septal occluder implantation within the 3D printed model (lower left and right).

In addition to the advanced imaging used for characterization of intracardiac neoplasm (e.g. Echo, MRI and CT), it has been shown that patient-specific 3D printed models are beneficial in the preoperative and intraoperative surgical management of cardiac tumor excisions.(47-49) Since cardiac tumors may extent into myocardial walls or valve structures, their radical and complete resection is rarely possible. Several reports have shown that knowledge gained by 3D printed modeling positively influenced the surgical strategy for intracardiac tumor management.(48, 49) This added value of 3D printed models was based upon the ability to clearly depict tumor interaction with surrounding tissue, while multi-color and multi-material models established clear tissue boundaries in ways that were difficult (or impossible) to appreciate using 2D or 3D imaging displays alone.(34, 47) 3D models that replicate specific static anatomy have been developed to replicate both the form and function of select cardiovascular conditions. Valverde et al showed that most surgeons found the use of 3D models helpful in surgical planning (4 out of 5) and would recommend the use of the technology to others (5 out of 5).(50)

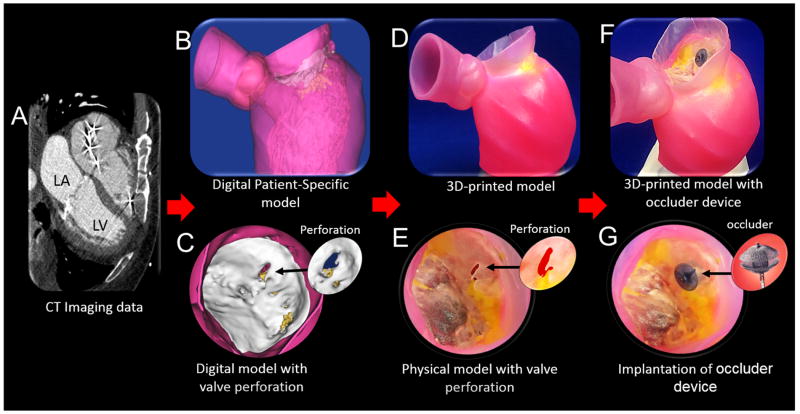

Patient-specific mitral valve models with leaflets have generally been 3D printed from only rigid materials, for the purpose of replicating static leaflet and annular geometry. However, some groups have developed patient-specific functional models of the mitral valve with deformable leaflets. These models have recently been used to plan first-in-man structural heart procedures to repair mitral valve function deploying both a MitraClip (Abbott Vascular, Abbott Park, IL) device, as well as an occluder device to treat severe mitral valve regurgitation.(51) (Figure 7). The percutaneous MitraClip procedure is a well-established method to achieve an edge-to-edge mitral valve repair, but as percutaneous MV replacement devices become available, the best treatment option for a specific patient may not be clear. Clinically, our ability to predict intra-procedural challenges (i.e. difficulty in grasping mitral leaflets) has been hampered by a lack of patient-specific MV models. 3D anatomic modeling may provide a solution to determine the “best-fit” amongst the possible catheter-based therapies available. In addition, such modeling may be valuable for predicting, and potentially avoiding, significant complications such as paravalvular regurgitation, device failure due to local calcification, or even the potentially devastating complication of LV outflow tract obstruction by the device or displaced native valve tissue. Our recent clinical experience has taught us that fused-material 3D modeling can be invaluable for pre-procedural device selection when there are patient-specific concerns about valvular calcification and its impact on the device-landing zone on either surface of mitral valve leaflets.(51) As catheter-based structural heart interventions become increasingly complex, the ability to effectively model patient-specific geometry, as well as the interaction of an implanted device within that geometry, will become even more valuable. Such 3D models are a cheap arena to prevent mistakes and promote innovation, and in some centers a 3D modeling program is already changing how the cardiovascular health professionals practice and prepare for specific structural heart interventions.(8, 34, 36, 37, 51)

Figure 7.

3D printed modeling for patient-specific mitral valve repair with a clip and a plug. CT images (A) are used to create a digital model (B) of the mitral valve with a perforation (C). A multi-material patient-specific 3D model (D) was printed to replicate the mitral valve geometry, regional calcium deposition and pathology (E). Images adapted from Little el al (52) with permission.

iv) Device innovation

The ability to test new or revised structural heart repair devices within a range of cardiac pathologies is particularly appealing. Although other modeling options have been relied upon for many years, device development using cadaveric models cannot be used for specific-patient procedure planning. Likewise, animal models invariably lack either the correct size or the pathologic element (e.g. calcification) of human cardiovascular conditions. The ability to review a clinical cohort of patients with a specific treatment target (e.g. severe degenerative MR with prohibitive surgical risk), perform volumetric clinical imaging, and convert that digital data into a focused 3D model of blended material properties is currently available. An example of this application is the delivery of trans-catheter mitral valve (TMVR) replacement devices.

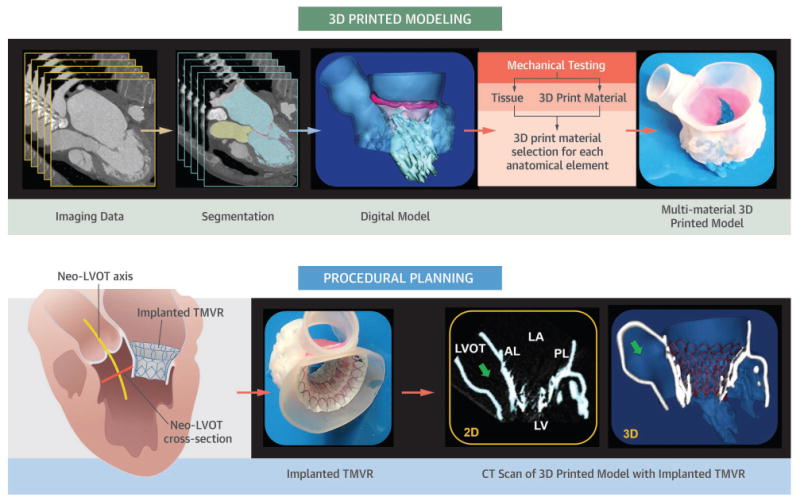

Unlike TAVR or MitraClip technologies, the development of TMVR devices and delivery techniques has been slower and more challenging.(52) Specific anatomic considerations are fundamental for the successful implementation of such devices, yet the principle anatomic features can vary significantly between prospective patients. The mitral annular area, anterior mitral leaflet length, aortic-mitral angle, LVOT area, and specific sub-valvular and annular calcium depositions are just some of the considerations. Although many of these anatomic features can now be clearly delineated and evaluated with increasingly sophisticated 3D visualization software (e.g. 3mensio [PMI, Netherlands]), in general, such tools fail to provide insight about how the device will deform or alter the native anatomy in a physical model (or within the patient). Therefore, the creation of an anatomically accurate, yet deformable patient-specific 3D model has all the attributes of a detailed digital model, but also provides for bench-top evaluation of the deformation of the critical anatomic relations influenced by the implanted TMVR device (e.g. the magnitude of anterior leaflet displacement into the LVOT) (Central Illustration). In fact, if 3D patient-specific models are created with material properties representing diseased human tissue, then two central features of a structural intervention may be assessed a priori, namely: 1) the effect of the device on anatomic configuration of native structures, and 2) the effect of native structures (especially calcium) on the deployed configuration of the implanted device (e.g. failed expansion of a TAVR device within a heavily calcified aortic root).

Central Illustration.

Creation of a patient-specific multi-material 3D model of the mitral valve apparatus. Utilization of the 3D model to perform a bench-top transcatheter mitral valve replacement (TMVR) procedure to evaluate for possible LVOT obstruction.

Development of printing materials

The first 3D printed models were fabricated from only a limited selection of rigid materials,(5, 15, 53) but currently the choice of available 3D print materials is considerably more varied. A relatively simple model can still be constructed using a single rigid material. Such models are generally more cost effective when the purpose is to simply visualize the anatomic relationship of specific structures,(16, 17, 54) as shown in figure 2. Commonly used rigid 3D print materials are from the Vero family of polymers, which are available in a large variety of colors, color blends, opaque, or transparent print formulations. However, an accurate replication of cardiac tissue mechanics requires that patient-specific models be fabricated from more flexible materials. Fortunately, there have been remarkable advances in material engineering that have created increasingly complex material blends that can approximate the mechanical properties of some cardiac tissues. For example, the elastomeric properties of the TangoPlus family of materials are used to create deformable cardiac models within a broad range of stiffness and compliance specifications.(9, 33, 41, 51, 55)

Among the available 3D printing technologies, the PolyJet technology is commonly used to fabricate patient-specific models because they allow for the replication of very complex anatomical structures by combining multiple colors and materials simultaneously. PolyJet machines (Objet 500 Connex 3, Stratasys) print 3D objects by adding high resolution layers (down to 16 microns resolution) and the selection of materials to approximate specific tissue properties, ranging from very soft (TangoPlus) to hard (VeroPlus) materials.

The use of material blends are often necessary for an accurate representation of abnormal features within heart valves, such as the calcific structures within the aortic and mitral valve (figure 7),(8) or to replicate a complex of anatomical elements with different tissue characteristics (central illustration).(19, 51) The choice of materials is particularly important for fabrication of functional models for experiments in pressurized flow loops with tailored hemodynamic conditions.(8, 9, 33, 41) For instance, Maragiannis et al. were able to fabricate a series of fully functional aortic stenosis models implantable in flow loop, replicating the entire aortic valve complex using flexible TangoPlus material, while the calcified aggregates within the valve cusps were 3D printed using a hard VeroPlus material.(9) They also demonstrated the compatibility of TangoPlus materials for echocardiographic imaging acquisition. Recent advancements in multi-material 3D printed modeling was extended to the complex MV apparatus with hard mitral annulus, deformable leaflets and chordae tendineae, and semi-rigid papillary muscles (supplemental Video 3).(19)

Despite the almost infinite possibilities of creating digital material blends, current 3D print materials can only replicate the mechanical properties of cardiovascular tissue to a certain extent.(12, 19, 56) Mechanical testing of a range of TangoPlus materials and comparison to cardiac tissue samples (mitral valve leaflet) showed that TangoPlus materials mimic the cardiac tissue mechanics only under a small range of leaflet deformations. As such, the accurate comparative analysis of human cardiac tissue and 3D print materials is problematic due to several issues, including: i) significant variation in some tissue properties that occurs with aging; ii) substantial difference in mechanical properties of cardiac structures during their functional and static states; and iii) the paucity of published data regarding the mechanical properties of the anatomy being targeted for 3D print replication.

This area of material exploration is new and rapidly progressing. Recent investigations have demonstrated that creating a patterned mixture of materials,(56, 57) or layered material composites within valve leaflets,(19) could approximate the physiological behavior of those anatomical elements. Biglino et al examined a distensible phantoms fabricated of TangoPlus materials and showed that this print material is suitable for manufacturing arterial vessels, while its mechanical characteristic may not be appropriate for modeling more compliant systemic vessels.(12) Accordingly, the ability to model the physiological behavior of certain cardiovascular elements largely depends upon the local flow dynamics as well as the specific anatomic complexity being modeled. For example, coronary artery flow evaluation would require that the coronary vessel wall be fabricated with a compliant 3D print material (or material blend if focal atherosclerotic plaque were also being modeled), whereas the visualization of a ventricular septal defect for catheter-based repair may not necessitate replication of the septal wall compliance.

Future Directions

By combining the technologies of high-spatial resolution cardiac imaging, image processing software, and fused dual-material 3D printing, several hospital centers have recently demonstrated that patient-specific models of various cardiovascular pathologies may offer an important additional perspective on the condition.(34, 36, 37, 42, 51) Patient-specific 3D MV models may directly impact our ability to select appropriate patients for structural heart therapy, anticipate procedural complications, and potentially revise and improve the flood of intra-cardiac devices that are rapidly becoming available for therapeutic use.

Before these technologies can have an even broader impact, there are several issues that still need to be resolved. The accuracy of replication of the cardiac structural geometry must be validated across a wide range of source imaging modalities, 3D print methods, and cardiovascular modeling scenarios. The negative consequence of any modeling error may be very different if the model is created to teach or convey anatomy, as compared to if the model is created for the detailed planning and device sizing of a catheter-based repair procedure. For example, the potential impact of variable loading conditions has yet to be determined. Efforts to replicate cardiac material properties with 3D print materials must show continued progress. Within a limited range of physiologic performance, the native cardiac elements (e.g. vessel wall, chamber wall, valve leaflet) can be modeled from a wide spectrum of 3D print material blends. The material properties of both normal and pathologic native cardiac structures must be considered (if known) before 3D printing can even begin to approximate a similar static performance. Progress must continue towards the development of implantable 3D printed patient-specific cardiac prostheses. Like the 3D printed titanium devices now used for maxillofacial and other orthopedic repair procedures,(58-61) the near-term future for cardiac 3D printing may include custom manufacturing of repair devices, conduits, or occluders. This notion of a personalized 3D printed cardiovascular prosthesis is not here today, but is now clearly visible on the horizon.

With applications in congenital heart disease, coronary artery disease, and in surgical and catheter-based structural disease – 3D printing is a new tool that is challenging how we image, plan, and carry out cardiovascular interventions.

Supplementary Material

Video 1. A patient-specific aortic stenosis model coupled to an in vitro flow circuit demonstrates the pulsatile elastomeric properties of a blend of 3D printed materials.

Video 2. Cone-beam computed tomography of a 3D printed model of an atrial septal defect (ASD) before and after catheter-based repair with a helical occluder. A bench-top catheter-based ASD repair was performed to evaluate for potential interaction between the ASD occulder device and a bioprosthetic mitral valve prosthesis. The frame of the ASD occluder device is clearly depicted to contact the 3D printed sewing ring of the mitral valve prosthesis but interference with the function of the bioprosthetic leaflets (not printed) was unlikely. The clinical procedure was performed with success.

Video 3. A patient-specific digital model of the entire mitral valve apparatus depicting prolapse of the posterior leaflet. A multi-material 3D printed model was created to evaluate potential repair using the MitraClip device (Abbott, USA).

Table 1.

Applications of 3D printed modeling in cardiovascular diseases.

| Study | Clinical condition | Printing method | Findings | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Computed tomography | Sodian et al. (11) | Aortic arch pseudoaneurysm | Stereolithography; rigid models | Creation of custom-made occluder for aortic pseudo-aneurysm |

| Jacobs et al.(47) | LV with aneurysm; RV tumor | Binder jetting; multi-color plaster based material | 3D model facilitated surgical resection | |

| Schmauss et al.(48) | RV tumor | Stereolithography; multi-color rigid material | 3D model facilitated surgical resection | |

| Maragiannis et al.(8,9) | Severe AS | PolyJet; rigid and flexible materials | Evaluation of AS models under patient-specific flow conditions | |

| Yang et al.(55) | Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy | PloyJet; multiple materials | Septal myomectomy guidance and procedural planning | |

| Russ et al.(32) | Circle of Willis, cardiac arteries and femoral artery | PolyJet; TangoPlus flexible material | Pre- interventional procedural practice in flow loop | |

| Little et al.(51) | Severe MR | PolyJet; multiple materials | MV model used for selection of repair devices in catheter-based clip and plug repair procedure | |

| Chawu et al.(38) | ASD | Not specified; Rigid model | Pre-procedural planning of trans-catheter occlusion of ASD | |

| Al Jabbari et al.(49) | LA and RA tumor | PolyJet; multiple materials | 3D model facilitated surgical resection | |

| Echocardiography | Binder et al.(15) | Normal and dysfunctional MV | Stereolithography; rigid models | Demonstrated feasibility of MV models based on 3D TEE |

| Kapur et al.(20) | MV annulus | Fused deposition molding; rigid plastic | Generated MV annulus models to facilitate MV repair | |

| Olivieri et al.(18) | VSD; paravalvular regurgitation | PolyJet; rigid material | Demonstrated feasibility and accuracy of 3D TEE based models | |

| Mahmood et al.(16) | Normal and dysfunctional MV | PolyJet; rigid annulus, flexible leaflets | Demonstrated feasibility of 3D TEE based MV models creation | |

| Vukicevic et al.(19) | LV and calcified MV apparatus | PolyJet; multiple-materials, differentiated tissue stiffness | 3D TEE and CT datasets combined to model for pre-procedural planning | |

| Witschey et al.(17) | Normal and dysfunctional MV | Fused deposition molding; plastic | MV models created using automated image segmentation | |

| Cardiac MRI | Markl et al.(14) | Thoracic aortic vasculature | PolyJet; TangoPlus material | Conversion of patients MRI data into physical vessels replica |

| Schivano et al.(10) | Dysfunctional PV | PolyJet; rigid material | Demonstrated accuracy of MRI based models for percutaneous valve implantation | |

| Greil et al.(12) | Normal and congenital heart | Laser sintering; rigid material | Demonstrated accuracy of MRI based models | |

| Biglino et al.(13) | Hypoplastic aortic arch and RVOT | PolyJet; flexible, TangoPlus | Evaluation of TangoPlus materials for arterial vessels replication | |

| Valverde et al.(50) | Aortic coarctation | Fused polymer filament; rigid and flexible | Demonstrated utility of models for interventional planning | |

| Costello et al.(43) | VSD | PolyJet; rigid materials | Demonstrated utility of heart models for medical student teaching |

AS = Aortic stenosis; ASD= atrial septal defect, LV = left ventricle; AV, aortic valve; CT = computed tomography; MR = mitral regurgitation; MRI = magnetic resonance imaging; MV = Mitral valve; PV = pulmonary valve; RA = right atrium; RV = right ventricle, LA = left atrium; RVOT = right ventricle outflow tract; TEE = transesophageal echocardiography; VSD = ventricular septal defect.

Abbreviations

- AS

aortic stenosis

- AV

aortic valve

- CAD

computer aided design

- DICOM

digital Image and Communication in Medicine

- LVOT

left ventricle outflow tract

- MR

mitral regurgitation

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- MV

mitral valve

- TAVR

transcatheter aortic valve replacement

- TMVR

transcatheter mitral valve replacement

Reference List

- 1.Farooqi KM, Sengupta PP. Echocardiography and three-dimensional printing: sound ideas to touch a heart. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2015;28:398–403. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2015.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sumida T, Otawa N, Kamata YU, et al. Custom-made titanium devices as membranes for bone augmentation in implant treatment: Clinical application and the comparison with conventional titanium mesh. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2015;43:2183–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2015.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aranda JL, Jimenez MF, Rodriguez M, Varela G. Tridimensional titanium-printed custom-made prosthesis for sternocostal reconstruction. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2015;48:e92–e94. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezv265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ibrahim D, Broilo TL, Heitz C, et al. Dimensional error of selective laser sintering, three-dimensional printing and PolyJet models in the reproduction of mandibular anatomy. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2009;37:167–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2008.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kato K, Ishiguchi T, Maruyama K, Naganawa S, Ishigaki T. Accuracy of plastic replica of aortic aneurysm using 3D-CT data for transluminal stent-grafting: experimental and clinical evaluation. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2001;25:300–4. doi: 10.1097/00004728-200103000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Knox K, Kerber CW, Singel SA, Bailey MJ, Imbesi SG. Rapid prototyping to create vascular replicas from CT scan data: making tools to teach, rehearse, and choose treatment strategies. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2005;65:47–53. doi: 10.1002/ccd.20333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim MS, Hansgen AR, Wink O, Quaife RA, Carroll JD. Rapid prototyping: a new tool in understanding and treating structural heart disease. Circulation. 2008;117:2388–94. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.740977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maragiannis D, Jackson MS, Igo SR, Chang SM, Zoghbi WA, Little SH. Functional 3D printed patient-specific modeling of severe aortic stenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:1066–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.05.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maragiannis D, Jackson MS, Igo SR, et al. Replicating Patient-Specific Severe Aortic Valve Stenosis With Functional 3D Modeling. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;8:e003626. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.115.003626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schievano S, Migliavacca F, Coats L, et al. Percutaneous pulmonary valve implantation based on rapid prototyping of right ventricular outflow tract and pulmonary trunk from MR data. Radiology. 2007;242:490–7. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2422051994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sodian R, Weber S, Markert M, et al. Stereolithographic models for surgical planning in congenital heart surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;83:1854–7. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Biglino G, Verschueren P, Zegels R, Taylor AM, Schievano S. Rapid prototyping compliant arterial phantoms for in-vitro studies and device testing. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2013;15:2. doi: 10.1186/1532-429X-15-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greil GF, Wolf I, Kuettner A, et al. Stereolithographic reproduction of complex cardiac morphology based on high spatial resolution imaging. Clin Res Cardiol. 2007;96:176–85. doi: 10.1007/s00392-007-0482-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Markl M, Schumacher R, Kuffer J, Bley TA, Hennig J. Rapid vessel prototyping: vascular modeling using 3t magnetic resonance angiography and rapid prototyping technology. MAGMA. 2005;18:288–92. doi: 10.1007/s10334-005-0019-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Binder TM, Moertl D, Mundigler G, et al. Stereolithographic biomodeling to create tangible hard copies of cardiac structures from echocardiographic data: in vitro and in vivo validation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35:230–7. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00498-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mahmood F, Owais K, Taylor C, et al. Three-dimensional printing of mitral valve using echocardiographic data. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;8:227–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2014.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Witschey WR, Pouch AM, McGarvey JR, et al. Three-dimensional ultrasound-derived physical mitral valve modeling. Ann Thorac Surg. 2014;98:691–4. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2014.04.094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Olivieri LJ, Krieger A, Loke YH, Nath DS, Kim PC, Sable CA. Three-dimensional printing of intracardiac defects from three-dimensional echocardiographic images: feasibility and relative accuracy. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2015;28:392–7. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2014.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vukicevic M, Puperi DS, Jane Grande-Allen K, Little SH. 3D Printed Modeling of the Mitral Valve for Catheter-Based Structural Interventions. Ann Biomed Eng. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s10439-016-1676-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kapur KK, Garg N. Echocardiography derived three- dimensional printing of normal and abnormal mitral annuli. Ann Card Anaesth. 2014;17:283–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gosnell J, Pietila T, Samuel BP, Kurup HK, Haw MP, Vettukattil JJ. Integration of Computed Tomography and Three-Dimensional Echocardiography for Hybrid Three-Dimensional Printing in Congenital Heart Disease. J Digit Imaging. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s10278-016-9879-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oyama R, Jakab M, Kikuchi A, Sugiyama T, Kikinis R, Pujol S. Towards improved ultrasound-based analysis and 3D visualization of the fetal brain using the 3D Slicer. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2013;42:609–10. doi: 10.1002/uog.12484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bauch T, Vijayaraman P, Dandamudi G, Ellenbogen K. Three-Dimensional Printing for In Vivo Visualization of His Bundle Pacing Leads. Am J Cardiol. 2015;116:485–6. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.04.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Firouzian A, Manniesging R, Flach ZH, Risselada R, Kooten F, Sturkenboom M. Intracranial aneurysm segmentation in 3D CT angiography: method and quantitative validation with and without prior noise filtering. European Journal of Radiology. 2016;79:299–304. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2010.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Byrne N, Velasco FM, Tandon A, Valverde I, Hussain T. A systematic review of image segmentation methodology, used in the additive manufacture of patient-specific 3D printed models of the cardiovascular system. JRSM Cardiovasc Dis. 2016;5 doi: 10.1177/2048004016645467. 2048004016645467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garekar S, Bharati A, Chokhandre M, et al. Clinical Application and Multidisciplinary Assessment of Three Dimensional Printing in Double Outlet Right Ventricle With Remote Ventricular Septal Defect. World J Pediatr Congenit Heart Surg. 2016;7:344–50. doi: 10.1177/2150135116645604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kiraly L, Tofeig M, Jha NK, Talo H. Three-dimensional printed prototypes refine the anatomy of post-modified Norwood-1 complex aortic arch obstruction and allow presurgical simulation of the repair. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2016;22:238–40. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivv320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vukicevic M, Maragiannis D, Jackson M, Little SH. Functional Evaluation of a Patient-Specific 3D Printed Model of Aortic Regurgitation (abstr) Circulation. 2015;132 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Javan R, Herrin D, Tangestanipoor A. Understanding Spatially Complex Segmental and Branch Anatomy Using 3D Printing: Liver, Lung, Prostate, Coronary Arteries, and Circle of Willis. Acad Radiol. 2016;23:1183–9. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2016.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xiong G, Kolli K, Soohoo HA, Min JK. In-Vitro Assessment of Coronary Hemodynamics in 3D Printed Patient-Specific Geometry (abstr) Circulation. 2015;132 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kolli KK, Min JK, Ha S, Soohoo H, Xiong G. Effect of Varying Hemodynamic and Vascular Conditions on Fractional Flow Reserve: An In Vitro Study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.116.003634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Russ M, O'Hara R, Setlur Nagesh SV, et al. Treatment Planning for Image-Guided Neuro-Vascular Interventions Using Patient-Specific 3D Printed Phantoms. Proc SPIE Int Soc Opt Eng. 2015;9417 doi: 10.1117/12.2081997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Biglino G, Capelli C, Binazzi A, et al. Virtual and real bench testing of a new percutaneous valve device: a case study. EuroIntervention. 2012;8:120–8. doi: 10.4244/EIJV8I1A19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schmauss D, Haeberle S, Hagl C, Sodian R. Three-dimensional printing in cardiac surgery and interventional cardiology: a single-centre experience. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2015;47:1044–52. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezu310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ryan JR, Moe TG, Richardson R, Frakes DH, Nigro JJ, Pophal S. A novel approach to neonatal management of tetralogy of Fallot, with pulmonary atresia, and multiple aortopulmonary collaterals. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;8:103–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2014.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Biglino G, Capelli C, Taylor AM, Schivano S. 3D printing cardiovascular anatomy: a single-center experience. New Trends in 3D Printing. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Farooqi KM, Saeed O, Zaidi A, et al. 3D Printing to Guide Ventricular Assist Device Placement in Adults With Congenital Heart Disease and Heart Failure. JACC Heart Fail. 2016;4:301–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2016.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chaowu Y, Hua L, Xin S. Three-Dimensional Printing as an Aid in Transcatheter Closure of Secundum Atrial Septal Defect With Rim Deficiency: In Vitro Trial Occlusion Based on a Personalized Heart Model. Circulation. 2016;133:e608–e610. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.020735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Noecker AM, Chen JF, Zhou Q, et al. Development of patient-specific three-dimensional pediatric cardiac models. ASAIO J. 2006;52:349–53. doi: 10.1097/01.mat.0000217962.98619.ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vranicar M, Gregory W, Douglas WI, Di SP, Di Sessa TG. The use of stereolithographic hand held models for evaluation of congenital anomalies of the great arteries. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2008;132:538–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vukicevic M, Conover T, Jaeggli M, et al. Control of respiration-driven retrograde flow in the subdiaphragmatic venous return of the Fontan circulation. ASAIO J. 2014;60:391–9. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0000000000000093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Farooqi KM, Nielsen JC, Uppu SC, et al. Use of 3-dimensional printing to demonstrate complex intracardiac relationships in double-outlet right ventricle for surgical planning. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;8 doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.114.003043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Costello JP, Olivieri LJ, Su L, et al. Incorporating three-dimensional printing into a simulation-based congenital heart disease and critical care training curriculum for resident physicians. Congenit Heart Dis. 2015;10:185–90. doi: 10.1111/chd.12238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Anwar S, Singh GK, Varughese J, et al. 3D Printing in Complex Congenital Heart Disease: Across a Spectrum of Age, Pathology, and Imaging Techniques. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2016.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Deferm S, Meyns B, Vlasselaers D, Budts W. 3D-Printing in Congenital Cardiology: From Flatland to Spaceland. J Clin Imaging Sci. 2016;6:8. doi: 10.4103/2156-7514.179408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cantinotti M, Giordano R, Volpicelli G, et al. Lung ultrasound in adult and paediatric cardiac surgery: is it time for routine use? Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2016;22:208–15. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivv315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jacobs S, Grunert R, Mohr FW, Falk V. 3D-Imaging of cardiac structures using 3D heart models for planning in heart surgery: a preliminary study. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2008;7:6–9. doi: 10.1510/icvts.2007.156588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schmauss D, Gerber N, Sodian R. Three-dimensional printing of models for surgical planning in patients with primary cardiac tumors. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013;145:1407–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Al Jabbari O, Abu Saleh WK, Patel AP, Igo SR, Reardon MJ. Use of three-dimensional models to assist in the resection of malignant cardiac tumors. J Card Surg. 2016;31:581–3. doi: 10.1111/jocs.12812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Valverde I, Gomez G, Suarez-Mejias C, et al. 3D printed cardiovascular models for surgical planning in complex congenital heart diseases. Journal of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. 2015;17:196. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Little SH, Vukicevic M, Avenatti E, Ramchandani M, Barker CM. 3D Printed Modeling for Patient-Specific Mitral Valve Intervention: Repair With a Clip and a Plug. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;9:973–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2016.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kheradvar A, Groves EM, Simmons CA, et al. Emerging trends in heart valve engineering: Part III. Novel technologies for mitral valve repair and replacement. Ann Biomed Eng. 2015;43:858–70. doi: 10.1007/s10439-014-1129-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kim H, Lu J, Sacks MS, Chandran KB. Dynamic simulation of bioprosthetic heart valves using a stress resultant shell model. Ann Biomed Eng. 2008;36:262–75. doi: 10.1007/s10439-007-9409-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mahmood F, Owais K, Montealegre-Gallegos M, et al. Echocardiography derived three-dimensional printing of normal and abnormal mitral annuli. Ann Card Anaesth. 2014;17:279–83. doi: 10.4103/0971-9784.142062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yang DH, Kang JW, Kim N, Song JK, Lee JW, Lim TH. Myocardial 3-Dimensional Printing for Septal Myectomy Guidance in a Patient With Obstructive Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2015;132:300–1. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.015842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang K, Zhao Y, Chang Y, et al. Controlling the mechancial behavior of dual-material 3D printed meta-materials for patient-specific tissue-mimicking phantoms. Materials & Design. 2016;90:704–12. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang K, Wu C, Qian Z, Zhang C, Wang B. Dual-material 3D printed metamaterials with turnable mechancial properties for patient-specific tissue-mimicking phantoms. Additive Manufacturing 16 AD. 12:31–7. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shah FA, Snis A, Matic A, Thomsen P, Palmquist A. 3D printed Ti6Al4V implant surface promotes bone maturation and retains a higher density of less aged osteocytes at the bone-implant interface. Acta Biomater. 2016;30:357–67. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2015.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Xu N, Wei F, Liu X, et al. Reconstruction of the Upper Cervical Spine Using a Personalized 3D-Printed Vertebral Body in an Adolescent With Ewing Sarcoma. Spine (Phila Pa 1976 ) 2016;41:E50–E54. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000001179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chen J, Zhang Z, Chen X, Zhang C, Zhang G, Xu Z. Design and manufacture of customized dental implants by using reverse engineering and selective laser melting technology. The Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry. 2014;112:1088–95 e1. doi: 10.1016/j.prosdent.2014.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sodian R, Schmauss D, Schmitz C, et al. 3-dimensional printing of models to create custom-made devices for coil embolization of an anastomotic leak after aortic arch replacement. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;88:974–8. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Blanke P, Naoum C, Webb J, et al. Multimodality Imaging in the Context of Transcatheter Mitral Valve Replacement: Establishing Consensus Among Modalities and Disciplines. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;8:1191–208. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2015.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Video 1. A patient-specific aortic stenosis model coupled to an in vitro flow circuit demonstrates the pulsatile elastomeric properties of a blend of 3D printed materials.

Video 2. Cone-beam computed tomography of a 3D printed model of an atrial septal defect (ASD) before and after catheter-based repair with a helical occluder. A bench-top catheter-based ASD repair was performed to evaluate for potential interaction between the ASD occulder device and a bioprosthetic mitral valve prosthesis. The frame of the ASD occluder device is clearly depicted to contact the 3D printed sewing ring of the mitral valve prosthesis but interference with the function of the bioprosthetic leaflets (not printed) was unlikely. The clinical procedure was performed with success.

Video 3. A patient-specific digital model of the entire mitral valve apparatus depicting prolapse of the posterior leaflet. A multi-material 3D printed model was created to evaluate potential repair using the MitraClip device (Abbott, USA).