Abstract

Purpose

This study evaluated the potential of 68Ga-citrate positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) for the detection of infectious foci in patients with Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia by comparing it with 2-[18F]fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (18F-FDG) PET/CT.

Methods

Four patients admitted to hospital due to S. aureus bacteraemia underwent both 18F-FDG and 68Ga-citrate whole-body PET/CT scans to detect infectious foci.

Results

The time from hospital admission and the initiation of antibiotic treatment to the first PET/CT was 4–10 days. The time interval between 18F-FDG and 68Ga-citrate PET/CT was 1–4 days. Three patients had vertebral osteomyelitis (spondylodiscitis) and one had osteomyelitis in the toe; these were detected by both 18F-FDG (maximum standardised uptake value [SUVmax] 6.0 ± 1.0) and 68Ga-citrate (SUVmax 6.8 ± 3.5, P = 0.61). Three patients had soft tissue infectious foci, with more intense 18F-FDG uptake (SUVmax 6.5 ± 2.5) than 68Ga-citrate uptake (SUVmax 3.9 ± 1.2, P = 0.0033).

Conclusions

Our small cohort of patients with S. aureus bacteraemia revealed that 68Ga-citrate PET/CT is comparable to 18F-FDG PET/CT for detection of osteomyelitis, whereas 18F-FDG resulted in a higher signal for the detection of soft tissue infectious foci.

1. Introduction

Positron emission tomography (PET) with the radiolabelled glucose analogue 2-[18F]fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (18F-FDG) is a sensitive and widely used method to detect inflammation and infection according to the high glucose uptake of activated inflammatory cells. It has an important role in the diagnosis of fever of unknown origin when conventional imaging has failed [1]. Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia is a life-threatening condition, and detection and eradication of deep infectious foci are crucial for successful treatment [2]. In previous studies, 18F-FDG PET/CT has proven to be a sensitive method for the detection of infectious foci in patients with gram-positive bacteraemia [2, 3].

68Ga-citrate has also been shown to be a sensitive and specific tracer for the detection of infectious lesions [4, 5], although only a few human studies using 68Ga-citrate PET/CT exist. The biological mechanism of 68Ga-citrate accumulation in infectious foci is not fully understood. Once injected the Ga-citrate complex is quickly dissociated into Ga3+ and citrate3− within the blood. Then, 99% of the gallium ions are attached to transferrin [6, 7], which accumulates in inflammatory lesions. In addition, it is assumed that some 68Ga may attach to bacterial siderophores, lactoferrin inside neutrophils, and free lactoferrin at the site of infection [8]. According to previous studies, 68Ga-citrate PET/CT appears to be a sensitive tool for the detection of bone infections [4, 9], although until now it has not been studied in patients with S. aureus bacteraemia.

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the potential of 68Ga-citrate PET/CT for the detection of infectious foci in patients with S. aureus bacteraemia by comparing it with 18F-FDG in a head-to-head setting.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects

This study evaluates four consecutive patients who were admitted to hospital due to S. aureus bacteraemia. All patients underwent both 18F-FDG and 68Ga-citrate whole-body PET/CT to detect infectious foci. The study was approved by the institutional ethical review board and all participants signed informed consent. The study was registered as a clinical trial (NCT01878721).

2.2. PET/CT

The synthesis of 68Ga-citrate was performed with automated synthesis device (Modular Lab, Eckert & Ziegler Eurotope GmbH, Berlin, Germany). 68Ga was obtained from a 68Ge/68Ga generator (IGG-100, 1850 MBq, Eckert & Ziegler Isotope Products, Valencia, CA, USA) by eluting the generator with 6 ml of 0.1 M hydrogen chloride (HCl). 68Ga was prepurified through a cationic exchanger (Strata X-C, Phenomenex Inc., Torrance, CA) by eluting with HCl/acetone-solution (800 μl). Acetone was then evaporated by heating at 110°C for 240 s and after cooling of 68GaCl3, the sterile isotonic sodium citrate solution (4 ml) was added to the reaction vial followed by 240 s reaction time. The product was transferred to the end product vial through a nonpyrogenic 0.22 μm sterile filter and diluted with saline (9 mg/ml, 6 ml). The radiochemical purity of the 68Ga-citrate was evaluated by instant thin layer chromatography-silica-gel technique using methanol/acetic acid (9 : 1) as a mobile phase. pH of the product was tested with indicator strips (pH range 2.0–9.0) and sterile filter integrity was assessed by a bubble point test.

Whole-body 18F-FDG and 68Ga-citrate PET/CT (Discovery VCT, GE Medical Systems) were performed in all patients within 1–4 days. All patients fasted before the 18F-FDG scan. The injected radioactivity doses of 18F-FDG and 68Ga-citrate were 292 ± 68 MBq (range: 227–387 MBq) and 196 ± 37 MBq (range: 158–245 MBq), respectively. PET scanning started at 58 ± 7 min (range: 52–67 min) after 18F-FDG injection and 81 ± 23 min (range: 48–100 min) after 68Ga-citrate injection. The whole-body PET acquisition (3 min/bed position) was performed following a low dose CT for anatomical reference and attenuation correction. PET images were reconstructed using a 3D maximum-likelihood reconstruction with an ordered-subsets expectation maximization algorithm (VUE Point, GE Healthcare). Visual analysis of the images was performed by an experienced nuclear medicine specialist (J. K.), with the results being reevaluated by the research team for consensus. A positive finding was defined as an abnormal accumulation of 18F-FDG or 68Ga-citrate indicating infectious foci. 18F-FDG and 68Ga-citrate uptake in the volumes of interest were quantified and expressed as maximum standardised uptake values (SUVmax) by normalising the tissue radioactivity concentration for the injected radioactivity dose and the patient's weight. The blood background radioactivity concentration was determined from the left ventricle cavity as SUVmean, and the target-to-background ratio (TBR) was calculated as SUVmax,infection/SUVmean,blood.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Results are expressed as mean ± SD and range. A paired t-test was used to compare 18F-FDG and 68Ga-citrate uptake. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

68Ga-citrate was prepared with high radiochemical purity (≥95%) with pH of 3.0−7.0.

Patient characteristics are presented in Table 1. All patients had a condition predisposing them to infection. In addition, Patient #3 had a cardiac pacemaker. The time interval from hospital admission and initiation of antibiotic treatment to the first PET/CT was 4–10 days, with the second PET/CT scan performed within another 1–4 days. The order of the 18F-FDG and 68Ga-citrate scans depended on the availability of tracers, with both being performed first in two cases. The mean C-reactive protein (CRP) levels were 89 ± 55 mg/l on the day of 18F-FDG PET/CT and 124 ± 118 mg/l on the day of 68Ga-citrate PET/CT (P = 0.56). The blood background (n = 4) SUVmean was 1.4 ± 0.05 for 18F-FDG and 2.9 ± 0.88 for 68Ga-citrate (P = 0.043).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study patients.

| Patient number | Age (years) |

Gender | Comorbidities | Time from starting antibiotics to 18F-FDG PET/CT (days) | Time from starting antibiotics to 68Ga-citrate PET/CT (days) | CRP on 18F-FDG PET/CT (mg/l) |

CRP on 68Ga-citrate PET/CT (mg/l) |

Complications from S. aureus bacteraemia based on routine exams, PET/CTs, and follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | 66 | F | Atopic eczema | 10 | 11 | 92 | 109 | Meningitis, vertebral osteomyelitis, paravertebral abscesses, multiple infectious foci in soft tissues |

| (2) | 70 | F | Liver cirrhosis, type 2 diabetes, generalised atherosclerosis, HTN | 6 | 5 | 14 | 14 | Vertebral osteomyelitis, pneumonia |

| (3) | 66 | M | Cardiomyopathy, HTN, asthma, cardiac pacemaker | 5 | 4 | 105 | 291 | Osteomyelitis in toe and feet |

| (4) | 86 | M | COPD, immunosuppressive medication due to chronic dermatology disease | 8 | 12 | 146 | 83 | Vertebral osteomyelitis, septic arthritis, multiple infectious foci in soft tissues |

F, female; M, male; HTN, hypertension; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CRP, C-reactive protein.

Three patients had vertebral osteomyelitis (spondylodiscitis) and one patient had osteomyelitis of the toe. The osteomyelitic foci were detected by both PET/CT methods (Table 2, Figures 1 and 2) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in the cases of vertebral osteomyelitis and X-ray in the case of osteomyelitis of the toe. In the areas of osteomyelitis (n = 4), the SUVmax of 18F-FDG was 6.0 ± 1.0 (range: 5.3–7.4) and the SUVmax of 68Ga-citrate was 6.8 ± 3.5 (range: 2.7–11.1, P = 0.61). The corresponding TBRs of 18F-FDG and 68Ga-citrate were 4.4 ± 0.90 and 2.5 ± 1.4, respectively (P = 0.015). Three patients had multiple infectious lesions and abscesses in soft tissue (Patients #1, #3, and #4). In these soft tissue infectious foci and abscesses (n = 8), the SUVmax of 18F-FDG (6.5 ± 2.5, range: 3.7–10.6) was significantly higher than that of 68Ga-citrate (3.9 ± 1.2, range: 2.1–6.1, P = 0.0033; Figure 1). The corresponding TBRs of 18F-FDG and 68Ga-citrate were 4.6 ± 1.8 and 1.7 ± 0.7, respectively (P = 0.00021).

Table 2.

Quantitative 18F-FDG and 68Ga-citrate PET/CT findings.

| Patient number | Visually active findings | 18F-FDG | 68Ga-citrate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SUVmax | TBR | SUVmax | TBR | ||

| Infectious foci | |||||

| (1) | Blood backgrounda | 1.4 | — | 2.1 | — |

| Vertebral osteomyelitis | 6.1 | 4.4 | 7.3 | 3.5 | |

| Psoas/paravertebral abscess | 10.6 | 7.6 | 6.1 | 2.9 | |

| Left elbow abscess | 9.4 | 6.7 | 4.0 | 1.9 | |

| Three soft tissue infectious foci in left arm | 7.3; 6.3; 5.4 | 5.2; 4.5; 3.9 | 5.0; 3.6; 3.5 | 2.4; 1.7; 1.7 | |

| Soft tissue infectious focus in left gluteus | 3.7 | 2.6 | 2.1 | 0.8 | |

| (2) | Blood backgrounda | 1.3 | — | 2.9 | — |

| Vertebral osteomyelitis | 7.4 | 5.7 | 11.1 | 3.8 | |

| Pneumonia, right lung | 2.7 | 2.1 | 3.7 | 1.3 | |

| Pneumonia, left lung | 3.9 | 3.0 | 3.1 | 1.1 | |

| (3) | Blood backgrounda | 1.4 | — | 2.4 | — |

| Septic arthritis and osteomyelitis, I toe | 5.3 | 3.8 | 2.7 | 1.1 | |

| Soft tissue infectious focus, I toe | 4.6 | 3.3 | 2.9 | 1.2 | |

| (4) | Blood backgrounda | 1.4 | — | 4.1 | — |

| Vertebral osteomyelitis | 5.3 | 3.8 | 5.9 | 1.4 | |

| Shoulder abscess | 4.5 | 3.2 | 4.2 | 1.0 | |

| Septic arthritis, glenohumeral joint | 5.0 | 3.6 | 2.5 | 0.6 | |

| Septic arthritis, sternoclavicular joint | 7.7 | 5.5 | 6.2 | 1.5 | |

|

| |||||

| Other metabolic findings | |||||

| (1) | Active spleen | 2.9 | 2.1 | 2.7 | 1.3 |

| Ascending aorta | 1.6 | 1.1 | 2.0 | 1.0 | |

| (2) | Parotid, unexplained | 1.8 | 1.4 | 9.4 | 3.2 |

| Reactive lymph nodes, neck right side | 2.5 | 1.9 | 5.6 | 1.9 | |

| Inferior vena cava, thrombosis | 2.5 | 1.9 | 8.6 | 3.0 | |

| Ascending aorta | 1.6 | 1.2 | 6.6 | 2.3 | |

| (3) | Caecum, unspecific uptake | 12.6 | 9.0 | 1.7 | 0.7 |

| Descending colon, tubular adenoma | 9.7 | 6.9 | 7.8 | 3.3 | |

| Ascending aorta | 2.1 | 1.5 | 5.4 | 2.3 | |

| (4) | Reactive lymph nodes, neck right side | 6.8 | 4.9 | 4.6 | 1.1 |

| Reactive lymph nodes, neck left side | 6.6 | 4.7 | 3.7 | 0.9 | |

| Ascending aorta | 1.2 | 0.9 | 4.6 | 1.1 | |

aDetermined from heart left ventricle cavity, SUVmean; TBR, target-to-background ratio (SUVmax,infection/SUVmean,blood).

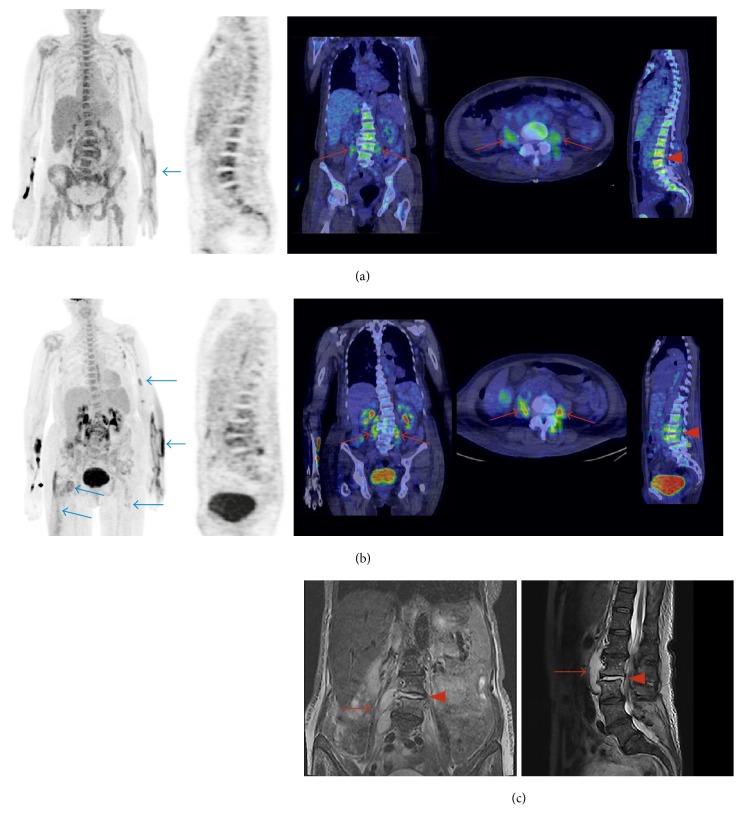

Figure 1.

Patient #1 was a 66-year-old woman (weight: 65 kg) who presented at the hospital because of back pain and general symptoms. Both 68Ga-citrate (a) and 18F-FDG PET/CT (b) showed vertebral osteomyelitis (spondylodiscitis; red arrowheads) and abscesses in the iliopsoas and paravertebral area (red arrows). These were confirmed by MRI (c). 18F-FDG PET/CT also showed other multiple soft tissue infectious foci ((b), blue arrows), some of which were not detectable on 68Ga-citrate PET/CT ((a), blue arrow). The injected radioactivity dose of 18F-FDG was 227 MBq and the PET acquisition started 54 min after injection. The injected radioactivity dose of 68Ga-citrate was 245 MBq and the PET acquisition started 88 min after injection. MRI sequences were as follows: T2-weighted short inversion time inversion recovery (STIR) on the coronal view image (left) and T2-weighted on the sagittal view image (right).

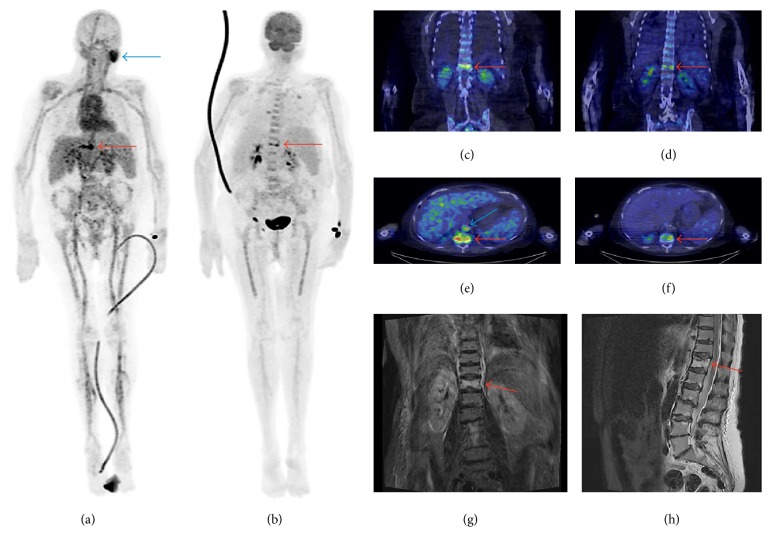

Figure 2.

Patient #2 was a 70-year-old woman (weight: 69 kg), with multiple background diseases, who was admitted to hospital because of back pain and high fever. Both 68Ga-citrate (a, c, e) and 18F-FDG PET/CT (b, d, f) showed vertebral osteomyelitis (spondylodiscitis) in Th12 (red arrows) and pneumonia in both lungs. MRI showed oedema in Th12 (g, h). 68Ga-citrate PET/CT also revealed uptake in the left parotid gland (unspecific; (a), blue arrow), neck lymph nodes (reactive), and inferior vena cava (thrombosis; (e), blue arrow). There was no 18F-FDG uptake in these areas. The injected radioactivity dose of 18F-FDG was 279 MBq and the PET acquisition started 50 min after injection. The injected radioactivity dose of 68Ga-citrate was 199 MBq and the PET acquisition started 100 min after injection. MRI sequences were as follows: T2-weighted short inversion time inversion recovery (STIR) on the coronal view image (left) and T2-weighted on the sagittal view image (right).

In addition to infectious foci, all of the patients also had other metabolic findings. Three patients (Patients #2, #3, and #4) demonstrated strong uptake of 68Ga-citrate in the larger arteries, coincidental to visible atherosclerosis on CT. In the ascending aorta (n = 4), the SUVmax of 68Ga-citrate was 4.7 ± 1.9 (range: 2.0–6.6), whereas the SUVmax of 18F-FDG was 1.6 ± 0.37 (range: 1.2–2.1, P = 0.051). The corresponding TBRs were 1.7 ± 0.72 for 68Ga-citrate and 1.2 ± 0.25 for 18F-FDG (P = 0.17). Patient #1 showed increased splenic uptake of both tracers, which was interpreted as a normal reaction in a septic condition. Patient #2 demonstrated high uptake of 68Ga-citrate in an enlarged parotid gland and lymph nodes in the neck (Figure 2(a)), which were not detected on 18F-FDG PET/CT. In the absence of clinical symptoms, the enlarged parotid gland was not further studied by MRI or ultrasound, so the observed 68Ga-citrate uptake remained unexplained. Patient #2 also demonstrated 68Ga-citrate uptake in the inferior vena cava, but not 18F-FDG uptake, with thrombosis being confirmed by ultrasonography. Patient #3 had a clear focal accumulation of both 68Ga-citrate and 18F-FDG in the descending colon, which was subsequently confirmed as a tubular adenoma in a colonoscopy with biopsies. The same patient also demonstrated 18F-FDG but not 68Ga-citrate accumulation in the caecum without specific findings on colonoscopy or biopsy. Patient #4 had reactive lymph nodes in the neck, which were indicated as being metabolically active by both imaging methods.

4. Discussion

We believe that this is the first study to compare 68Ga-citrate and 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging of infectious foci in patients with S. aureus bacteraemia. Our results revealed that 68Ga-citrate and 18F-FDG are comparable PET tracers for the detection of osteomyelitis. However, the soft tissue infectious foci were clearly better visualized with 18F-FDG than 68Ga-citrate.

In general, two different tracers must be compared with caution and taking into account their potentially different properties, such as uptake mechanisms and flow/diffusion dependency. In animal models, both 18F-FDG and 68Ga-chloride have shown increased accumulation in S. aureus osteomyelitis, whereas, in healing bones without infection, only 18F-FDG accumulation was observed [9]. Our results are in line with the animal studies, in that accumulation of these tracers in patients with osteomyelitis does not differ in the acute phase of S. aureus infection. Further studies are warranted to clarify whether 68Ga-citrate PET/CT can confirm the healing of osteomyelitis and whether it is superior to 18F-FDG for the differentiation of infection from sterile bone inflammation.

We found a difference between 18F-FDG and 68Ga-citrate PET/CT in the detection of soft tissue infection. Contrary to the clear findings of multiple small infectious foci without abscess formation in 18F-FDG PET/CT, such lesions were only slightly visible or not visible at all on 68Ga-citrate PET/CT (Patient #1). The difference in SUVmax between 18F-FDG and 68Ga-citrate was also statistically significant. These findings were not controlled by other imaging modalities, but some were also detectable in clinical status (e.g., multiple infectious foci in Patient #1's arm). In this study we used 196 ± 37 MBq for 68Ga-citrate PET and started imaging after 81 ± 23 minutes. The observed blood background SUVmean 2.9 + 0.88 may be a strong contributing factor for not visualizing soft tissue infections with 68Ga-citrate. It can be hypothesized that lowering of injected radioactivity dose to 100 MBq would reduce blood pool radioactivity and cause less background noise. In order to confirm the effect of a lower 68Ga-citrate dose, further studies are warranted. A recent study comparing 18F-FDG, 68Ga-citrate, and other tracers in a pig-model of hematogenously disseminated S. aureus infection reported slightly different results [10]. These findings may be due to the higher blood background radioactivity of 68Ga-citrate (Table 2). The slight differences in the production of 68Ga-citrate might reflect different results, too.

Owing to its high sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy in the detection of osteomyelitis, MRI is the recommended imaging modality when spondylodiscitis is suspected [11]. MRI provides higher spatial resolution of the spinal cord than PET/CT, which is important if an operation is considered. However, sometimes MRI cannot be obtained because of patient-related reasons (e.g., implanted cardiac devices, claustrophobia). In such cases, 18F-FDG PET/CT is the recommended imaging modality [11]. Traditionally, MRI is targeted to the part of the body where the patient has signs or symptoms; however, a previous study [12] showed that around one-third of infectious foci in S. aureus bacteraemia are asymptomatic. Thus, these silent infectious foci may pass unnoticed with traditional imaging, while PET/CT scanning provides information on the whole body, and as demonstrated in our cases, multiple infectious foci can be detected simultaneously.

In addition to infectious foci, both 18F-FDG and 68Ga-citrate PET/CT also revealed other clinically significant findings. In Patient #3, PET/CT findings in the colon led to colonoscopy and the finding of a tubular adenoma. Patient #2 demonstrated an uptake of 68Ga-citrate (but not 18F-FDG) in the inferior vena cava where thrombosis was later confirmed by ultrasound. This can be related to pooling tracer just proximal to the narrowing caused by the thrombus. More comprehensive studies are needed to explain the differences in the findings of 68Ga-citrate and 18F-FDG, for example, whether they are ascribed due to infection versus sterile inflammation.

The accumulation of 68Ga-citrate in atherosclerotic arteries warrants further studies to determine its importance. Previously, 68Ga-chloride uptake has been demonstrated in atherosclerotic lesions in mice [13]. Instead, in the papers presented by Nanni and coworkers [4] as well as Vorster and coworkers [14], the relatively high vascular radioactivity was regarded as a normal biodistribution of 68Ga-citrate. The identification of atherosclerosis in 3 patients by 68Ga-citrate may be coincidental. One advantage of 68Ga-citrate over 18F-FDG is that patients are not required to fast before the scan. However, for detection of metastatic endovascular infection the accumulation of 68Ga-citrate in atherosclerotic arteries can be regarded as a limitation of 68Ga-citrate PET/CT in patients with S. aureus bacteraemia.

In the current study, the time intervals between 18F-FDG and 68Ga-citrate scans were short (1–4 days), and CRP remained at the same levels over these intervals. Neither surgical procedures nor changes to the antimicrobial treatment were made between the two scans. We thus consider that the infectious status of the patients did not differ markedly between 18F-FDG and 68Ga-citrate studies. However, time interval from commencement of antibiotic treatment to the first PET/CT was 4–10 days and we are not able to exclude the possibility that due to this delay some of the infectious lesions were not detected. We also determined the TBRs, which revealed that the blood radioactivity concentration of 68Ga-citrate was higher than that of 18F-FDG. Thus, in many foci, the TBRs of 68Ga-citrate PET/CT were lower than in 18F-FDG PET/CT. In general, the number of patients is small, which can be regarded as a limitation of this study.

5. Conclusion

68Ga-citrate and 18F-FDG are comparable PET tracers for the imaging of osteomyelitis in patients with S. aureus bacteraemia. Further studies are warranted to clarify whether 68Ga-citrate PET/CT can detect osteomyelitis caused by other pathogens and whether it can assess the healing of infectious osteomyelitis. For the detection of soft tissue infectious foci, 18F-FDG PET/CT shows higher intensity than 68Ga-citrate PET/CT but the effect of lower 68Ga-citrate dose should be verified by further studies.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mia Koutu and Laura Kontto for helping with PET/CT imaging and Timo Kattelus for helping with the images. This study was conducted in the Finnish Centre of Excellence in Cardiovascular and Metabolic Diseases supported by the Academy of Finland, University of Turku, Turku University Hospital, and Åbo Akademi University. This study was also funded by Turku University Foundation and the Foundation of Rauno and Anne Puolimatka.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Ergül N., Halac M., Cermik TF., et al. The diagnostic role of FDG PET/CT in patients with fever of unknown origin. Molecular Imaging and Radionuclide Therapy. 2011;20:19–25. doi: 10.4274/MIRT.20.04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vos F. J., Kullberg B. J., Sturm P. D., et al. Metastatic infectious disease and clinical outcome in Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus species bacteremia. Medicine. 2012;91(2):86–94. doi: 10.1097/MD.0b013e31824d7ed2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vos F. J., Bleeker-Rovers C. P., Sturm P. D. 18F-FDG PET/CT for detection of metastatic infection in gram-positive bacteremia. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2010;51(8):1234–1240. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.072371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nanni C., Errani C., Boriani L. 68Ga-citrate PET/CT for evaluating patients with infections of the bone: preliminary results. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2010;51(12):1932–1936. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.110.080184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kumar V., Boddeti D. K., Evans S. G., Angelides S. 68Ga-citrate-PET for diagnostic imaging of infection in rats and for intra-abdominal infection in a patient. Current Radiopharmaceuticals. 2012;5(1):71–75. doi: 10.2174/1874471011205010071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsan M-F. Mechanism of gallium-67 accumulation in inflammatory lesions. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 1985;26:88–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kumar V., Boddeti D. K., Evans S. G., Roesch F., Howman-Giles R. Potential use of 68Ga-apo-transferrin as a PET imaging agent for detecting Staphylococcus aureus infection. Nuclear Medicine and Biology. 2011;38(3):393–398. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2010.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoffer P. Gallium Mechanisms. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 1980;21:282–285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mäkinen T. J., Lankinen P., Pöyhönen T., Jalava J., Aro H. T., Roivainen A. Comparison of 18F-FDG and 68Ga PET imaging in the assessment of experimental osteomyelitis due to Staphylococcus aureus. European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging. 2005;32(11):1259–1268. doi: 10.1007/s00259-005-1841-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nielsen O. L., Afzelius P., Bender D., et al. Comparison of autologous 111In-leukocytes, 18F-FDG, 11C-methionine, 11C-PK11195 and 68Ga-citrate for diagnostic nuclear imaging in a juvenile porcine haematogenous staphylococcus aureus osteomyelitis model. American Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging. 2015;5:169–182. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berbari E. F., Kanj S. S., Kowalski T. J., et al. 2015 Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) Clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of native vertebral osteomyelitis in adults. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2015;61(6):e26–e46. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cuijpers M. L., Vos F. J., Bleeker-Rovers C. P., et al. Complicating infectious foci in patients with Staphylococcus aureus or Streptococcus species bacteraemia. European Journal of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Disease. 2007;26:105–113. doi: 10.1007/s10096-006-0238-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Silvola J. M. U., Laitinen I., Sipilä H. J., et al. Uptake of 68gallium in atherosclerotic plaques in LDLR−/−ApoB100/100mice. EJNMMI Research. 2011;1(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/2191-219X-1-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vorster M., Maes A., Jacobs A., et al. Evaluating the possible role of 68Ga-citrate PET/CT in the characterization of indeterminate lung lesions. Annals of Nuclear Medicine. 2014;28:523–530. doi: 10.1007/s12149-014-0842-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]