Significance

How do ordinary people make sense of mental life? Pioneering work on the dimensions of mind perception has been widely interpreted as evidence that lay people perceive two fundamental components of mental life: experience and agency. However, using a method better suited to addressing this question, we discovered a very different conceptual structure. Our four studies consistently revealed three components of mental life—suites of capacities related to the body, the heart, and the mind—with each component encompassing related aspects of both experience and agency. This body–heart–mind framework distinguishes itself from the experience–agency framework by its clear and importantly different implications for dehumanization, moral reasoning, and other important social phenomena.

Keywords: mind perception, folk theories, animacy, agency, social cognition

Abstract

How do people make sense of the emotions, sensations, and cognitive abilities that make up mental life? Pioneering work on the dimensions of mind perception has been interpreted as evidence that people consider mental life to have two core components—experience (e.g., hunger, joy) and agency (e.g., planning, self-control) [Gray HM, et al. (2007) Science 315:619]. We argue that this conclusion is premature: The experience–agency framework may capture people’s understanding of the differences among different beings (e.g., dogs, humans, robots, God) but not how people parse mental life itself. Inspired by Gray et al.’s bottom-up approach, we conducted four large-scale studies designed to assess people’s conceptions of mental life more directly. This led to the discovery of an organization that differs strikingly from the experience–agency framework: Instead of a broad distinction between experience and agency, our studies consistently revealed three fundamental components of mental life—suites of capacities related to the body, the heart, and the mind—with each component encompassing related aspects of both experience and agency. This body–heart–mind framework distinguishes itself from Gray et al.’s experience–agency framework by its clear and importantly different implications for dehumanization, moral reasoning, and other important social phenomena.

What is the underlying organization of the emotions, sensations, cognitive abilities, and other phenomena that make up our mental lives? Curiosity about the nature of consciousness and subjective experience extends back to antiquity, with Plato arguing for a tripartite distinction between appetite, spirit, and reason, while the Buddha described sentient beings as aggregations of material form, feelings, perceptions, impulses, and consciousness. Beyond philosophical curiosity, the way people represent mental life has major ramifications for their moral judgments, their evaluation of novel social entities, their treatment of fellow humans, and other important social phenomena.

Here we explore how US adults conceive of mental life. The backdrop for this exploration is the theory of “the dimensions of mind perception” advanced by Gray et al. (1) in their pioneering work on how people conceive of different kinds of minds. In their study, participants compared the mental capacities of a variety of characters ranging from people and animals to a fetus, a robot, and God. Two dimensions seemed to organize this conceptual space: “experience,” i.e., the extent to which a character is capable of hunger, fear, pain, pleasure, rage, desire, personality, consciousness, pride, embarrassment, and joy; and “agency,” the extent to which a character is capable of self-control, morality, memory, emotion recognition, planning, communication, and thought [see Study S1: Replication of Gray et al. (2007) for a successful replication of this study.]

One of the most exciting aspects of Gray et al.’s approach was that, rather than imposing theory-driven categories onto participants’ responses, the authors let the data speak for themselves, extracting the experience–agency framework from participants’ responses to relatively simple questions (e.g., “Which is more capable of experiencing joy: Kismet the social robot or Nicholas Gannon the 5-mo-old infant?”). This bottom-up approach has tremendous potential for elucidating the kinds of deep conceptual structures that are difficult for participants to report on directly and for experimenters to anticipate a priori.

In the decade since the publication of Gray et al.’s initial study, the distinction between experience and agency has come to define contemporary work on mind perception. Researchers have invoked the experience–agency framework to inform such diverse topics as the objectification of women, described as an emphasis on a woman’s capacity for experience at the expense of her agency (2); the dynamics of human–robot interaction, in which perceptions of robotic experience are said to drive feelings of discomfort or uncanniness (3); the social–cognitive signatures of autism spectrum disorders, schizotypy, and psychopathy (4); and general theories of moral reasoning, in which experience is linked to moral patiency and agency to moral responsibility (5, 6; cf. ref. 7). Beyond this, experience and agency are now widely taken to be the fundamental components of mental life according to ordinary people (8).

There is good reason to suspect, however, that broad categories of experience and agency might not capture people’s intuitive ontology of mental life. One important source of this skepticism is the long tradition of work on theory of mind (9). In their theories of how people reason about other minds, developmental psychologists make critical distinctions among perception, emotion, and desire (10)—all of which would fall under the umbrella of experience in the experience–agency framework. This suggests that, as a model of people’s intuitive ontology of mental life, the experience–agency framework is (at a minimum) incomplete.

In fact, we would argue that the studies that generated the experience–agency framework did not actually assess people’s intuitions about the structure of mental life. Doing so would require a sensitive measure that encourages participants to think about the connections and divisions among mental capacities: Which capacities “go together,” and which are more distinct? Instead, participants in Gray et al.’s original study were led to focus on the similarities and differences among characters: Each participant engaged in a series of pairwise comparisons of characters (e.g., comparing a robot vs. an infant, a woman vs. God) while considering only one mental capacity throughout the session (e.g., one participant would compare characters’ relative capacities for joy, while another participant would compare their capacities for pain). This approach is well suited to reveal how participants think about the similarities and differences among social beings, i.e., how different characters rank in their capacities for joy, pain, and so forth. However the observation that, in the aggregate, participants who considered characters’ capacities for joy ranked them similarly to those who considered characters’ capacities for pain does not necessarily mean that people consider these two mental capacities to be particularly strongly related. Thus, while concepts of experience and agency seem to capture an important aspect of how people compare different beings, it is unclear whether they correspond to folk conceptions of the fundamental components of mental life.

Our primary goal in the present studies was to directly investigate the conceptual space of mental capacities themselves. Inspired by Gray et al.’s bottom-up approach, we designed an experimental paradigm that would allow this intuitive ontology of mental life to emerge from participants’ responses organically, without top-down hypotheses about which kinds of mental capacities might go together in people’s reasoning. We led participants to focus on the connections and divisions between different aspects of mental life by asking them to evaluate a wide variety of mental capacities for a single character. For example, one participant would be asked to consider the extent to which a robot is capable of experiencing joy, experiencing pain, seeing things, having intentions, and so forth, while another participant would be asked the same questions about an insect, a human, or some other entity. We used patterns of attributions—i.e., when a participant judged some character to be highly capable of some capacity, which other capacities came along with it—to infer which mental capacities were seen as related and which were considered independent. This approach, in which each individual participant compares and contrasts a range of mental capacities, is a more direct and valid way of assessing participants’ intuitions about the organization of these mental capacities than inferring this conceptual structure via Gray et al.’s original study design.

We began by exploring attributions of mental capacities to two carefully selected edge cases in social reasoning: a beetle and a robot. This approach offers several advantages. First, beetles are likely considered much more capable of experience and less capable of agency than robots (1). Moreover, because beetles are animals and robots are artifacts, this pair provides a glimpse into the role of biological life in attributions of mental life. Most importantly for our bottom-up approach, the capacities of these edge cases were expected to be controversial, ensuring that not all participants would endorse all capacities (as they might for, say, a human). This allowed us to address the following question: When people disagree about what some entity is capable of, which mental capacities tend to go together?

In study 1, each participant judged either a beetle (n = 200) or a robot (n = 205) on 40 mental capacities, including various affective, perceptual, physiological, cognitive, agentic, social, and other abilities. Study 2 was a direct replication (n = 406). In study 3 (n = 200), each participant judged both a beetle and a robot side by side, allowing us to examine whether the intuitions revealed by studies 1 and 2 are preserved when individual participants are presented with the salient contrast between the two edge cases. In study 4, we broadened the set of characters to include a wide range of entities: Each participant (n = 431) judged one of 21 entities (adult, child, infant, person in a persistent vegetative state, fetus, chimpanzee, elephant, dolphin, bear, dog, goat, mouse, frog, blue jay, fish, beetle, microbe, robot, computer, car, stapler). This allowed us to assess which aspects of mental life hang together when different entities are considered to have different profiles of mental capacities.

Results

Using a bottom-up approach with the potential to affirm or challenge the experience–agency framework, we discovered a different conceptual organization: a three-way distinction between physiological abilities related to the body, social–emotional abilities related to what we might call the heart, and perceptual–cognitive abilities related to the mind, with each factor encompassing aspects of both experience and agency. In integrating related forms of experience and agency, each of these three factors hints at a coherent and distinct subsystem for making sense of the behavior of other beings. In the case of the body, physiological sensations indicate biological needs, which an animal might address via self-initiated behavior (see ref. 11). In the case of the heart, a person’s emotional life and his or her ability to anticipate others’ emotions bear on the social and moral ramifications of his or her behavior (see refs. 1, 5, and 6). In the case of the mind, perceptual access and cognitive representational abilities combine to influence an agent’s goal-directed actions, as theory of mind researchers have long discussed (9).

Independent exploratory factor analyses for each of our four studies all revealed this same three-factor structure (Table 1; see Figs. S2 and S3 for the mean responses for each mental capacity, by target character.)

Table 1.

Factor loadings from exploratory factor analyses for all studies (after varimax rotation)

| Factor 1: Body | Factor 2: Heart | Factor 3: Mind | |||||||||||

| A priori category | Item | Study 1 | Study 2 | Study 3 | Study 4 | Study 1 | Study 2 | Study 3 | Study 4 | Study 1 | Study 2 | Study 3 | Study 4 |

| PHY | Getting hungry* | 0.92 | 0.91 | 0.92 | 0.84 | –0.01 | –0.04 | 0.08 | 0.11 | –0.06 | –0.07 | –0.03 | 0.33 |

| PHY | Experiencing pain* | 0.92 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.86 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.33 |

| PHY | Feeling tired | 0.83 | 0.86 | 0.83 | 0.85 | 0.22 | 0.14 | 0.30 | 0.21 | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.36 |

| EMO | Experiencing fear* | 0.83 | 0.83 | 0.79 | 0.83 | 0.26 | 0.21 | 0.34 | 0.20 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.37 |

| Experiencing pleasure* | 0.75 | 0.73 | 0.71 | 0.79 | 0.41 | 0.41 | 0.48 | 0.35 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.35 | |

| COG | Doing computations | –0.73 | –0.73 | –0.79 | –0.40 | 0.21 | 0.19 | 0.10 | 0.51 | 0.42 | 0.45 | 0.26 | 0.39 |

| AGE | Having free will | 0.71 | 0.72 | 0.70 | 0.60 | 0.35 | 0.17 | 0.39 | 0.42 | 0.09 | 0.14 | 0.17 | 0.38 |

| Being conscious* | 0.71 | 0.75 | 0.70 | 0.65 | 0.36 | 0.22 | 0.40 | 0.35 | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.19 | 0.38 | |

| PHY | Feeling safe | 0.70 | 0.71 | 0.70 | 0.74 | 0.35 | 0.31 | 0.34 | 0.32 | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.36 |

| Having desires* | 0.70 | 0.67 | 0.74 | 0.69 | 0.40 | 0.42 | 0.42 | 0.43 | 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.18 | 0.34 | |

| PHY | Feeling nauseated | 0.67 | 0.62 | 0.66 | 0.70 | 0.48 | 0.39 | 0.47 | 0.40 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.27 |

| EMO | Feeling calm | 0.66 | 0.59 | 0.61 | 0.75 | 0.40 | 0.39 | 0.48 | 0.35 | 0.17 | 0.24 | 0.24 | 0.32 |

| EMO | Getting angry* | 0.60 | 0.62 | 0.56 | 0.68 | 0.55 | 0.47 | 0.60 | 0.46 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.11 | 0.31 |

| AGE | Having intentions | 0.54 | 0.56 | 0.54 | 0.49 | 0.35 | 0.25 | 0.33 | 0.47 | 0.26 | 0.35 | 0.33 | 0.44 |

| Being self-aware | 0.53 | 0.47 | 0.50 | 0.38 | 0.48 | 0.49 | 0.48 | 0.60 | 0.21 | 0.25 | 0.24 | 0.35 | |

| SOC | Feeling embarrassed* | 0.20 | 0.17 | 0.19 | 0.29 | 0.85 | 0.79 | 0.74 | 0.82 | –0.02 | –0.05 | 0.02 | 0.09 |

| Experiencing pride* | 0.29 | 0.27 | 0.25 | 0.43 | 0.84 | 0.80 | 0.77 | 0.74 | 0.05 | –0.01 | 0.07 | 0.20 | |

| SOC | Feeling love | 0.39 | 0.41 | 0.44 | 0.65 | 0.79 | 0.70 | 0.69 | 0.56 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.15 | 0.18 |

| SOC | Experiencing guilt | 0.27 | 0.18 | 0.21 | 0.31 | 0.79 | 0.84 | 0.76 | 0.82 | 0.01 | –0.04 | 0.07 | 0.13 |

| COG | Holding beliefs | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.19 | 0.77 | 0.64 | 0.65 | 0.83 | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.14 |

| SOC | Feeling disrespected | 0.27 | 0.25 | 0.23 | 0.30 | 0.77 | 0.73 | 0.75 | 0.78 | 0.04 | –0.01 | 0.08 | 0.18 |

| EMO | Feeling depressed | 0.39 | 0.41 | 0.37 | 0.52 | 0.76 | 0.73 | 0.73 | 0.62 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.23 |

| SOC | Understanding how others are feeling† | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.33 | 0.72 | 0.69 | 0.64 | 0.72 | 0.28 | 0.31 | 0.34 | 0.30 |

| EMO | Experiencing joy* | 0.53 | 0.58 | 0.52 | 0.72 | 0.68 | 0.59 | 0.67 | 0.51 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.25 |

| Having a personality* | 0.23 | 0.21 | 0.23 | 0.64 | 0.67 | 0.61 | 0.62 | 0.52 | 0.30 | 0.32 | 0.36 | 0.33 | |

| EMO | Feeling happy | 0.57 | 0.57 | 0.54 | 0.74 | 0.63 | 0.63 | 0.66 | 0.48 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.17 | 0.23 |

| Telling right from wrong† | –0.04 | –0.11 | –0.11 | 0.17 | 0.62 | 0.60 | 0.54 | 0.81 | 0.31 | 0.33 | 0.37 | 0.25 | |

| AGE | Exercising self-restraint† | 0.24 | 0.09 | 0.20 | 0.24 | 0.57 | 0.53 | 0.57 | 0.71 | 0.30 | 0.31 | 0.26 | 0.38 |

| COG | Having thoughts† | 0.51 | 0.55 | 0.52 | 0.60 | 0.55 | 0.49 | 0.55 | 0.49 | 0.21 | 0.23 | 0.31 | 0.33 |

| COG | Remembering things† | –0.20 | –0.19 | –0.15 | 0.26 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.20 | 0.41 | 0.71 | 0.70 | 0.65 | 0.71 |

| SOC | Recognizing someone | –0.28 | –0.28 | –0.26 | 0.43 | 0.31 | 0.34 | 0.30 | 0.38 | 0.70 | 0.62 | 0.65 | 0.59 |

| PER | Sensing temperatures | 0.21 | 0.25 | 0.39 | 0.40 | –0.07 | –0.07 | –0.07 | 0.06 | 0.68 | 0.61 | 0.60 | 0.71 |

| SOC | Communicating with others† | –0.03 | 0.09 | –0.12 | 0.35 | 0.21 | 0.12 | 0.17 | 0.30 | 0.64 | 0.71 | 0.60 | 0.71 |

| PER | Seeing things | 0.35 | 0.37 | 0.36 | 0.56 | –0.08 | –0.02 | –0.04 | 0.13 | 0.63 | 0.65 | 0.55 | 0.67 |

| PER | Perceiving depth | 0.10 | 0.03 | 0.19 | 0.29 | 0.11 | 0.08 | 0.11 | 0.32 | 0.62 | 0.58 | 0.59 | 0.68 |

| AGE | Working toward a goal† | 0.09 | 0.16 | 0.15 | 0.23 | 0.17 | 0.13 | 0.22 | 0.41 | 0.62 | 0.67 | 0.57 | 0.57 |

| PER | Detecting sounds | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.20 | 0.45 | –0.05 | –0.06 | –0.04 | 0.08 | 0.61 | 0.71 | 0.65 | 0.75 |

| AGE | Making choices | 0.24 | 0.21 | 0.27 | 0.38 | 0.20 | 0.18 | 0.23 | 0.37 | 0.60 | 0.67 | 0.58 | 0.67 |

| COG | Reasoning about things | –0.07 | –0.11 | –0.13 | 0.17 | 0.49 | 0.44 | 0.43 | 0.66 | 0.56 | 0.52 | 0.57 | 0.48 |

| PER | Detecting odors | 0.45 | 0.45 | 0.53 | 0.58 | –0.02 | –0.01 | 0.03 | 0.22 | 0.45 | 0.51 | 0.43 | 0.58 |

| Total variance explained (after varimax rotation), % | 36 | 35 | 40 | 39 | 31 | 28 | 26 | 29 | 18 | 19 | 16 | 20 | |

Loadings greater than or equal to 0.60 or less than or equal to −0.60 are in boldface type. Items are listed according to their dominant factor loading in study 1. Each item is listed with its a priori category membership: AGE, agentic; EMO, emotional; COG, cognitive; PER, perceptual; PHY, physiological; SOC, social; and other/multiple (unmarked).

Experience dimension from Gray et al. (1).

Agency dimension from Gray et al. (1).

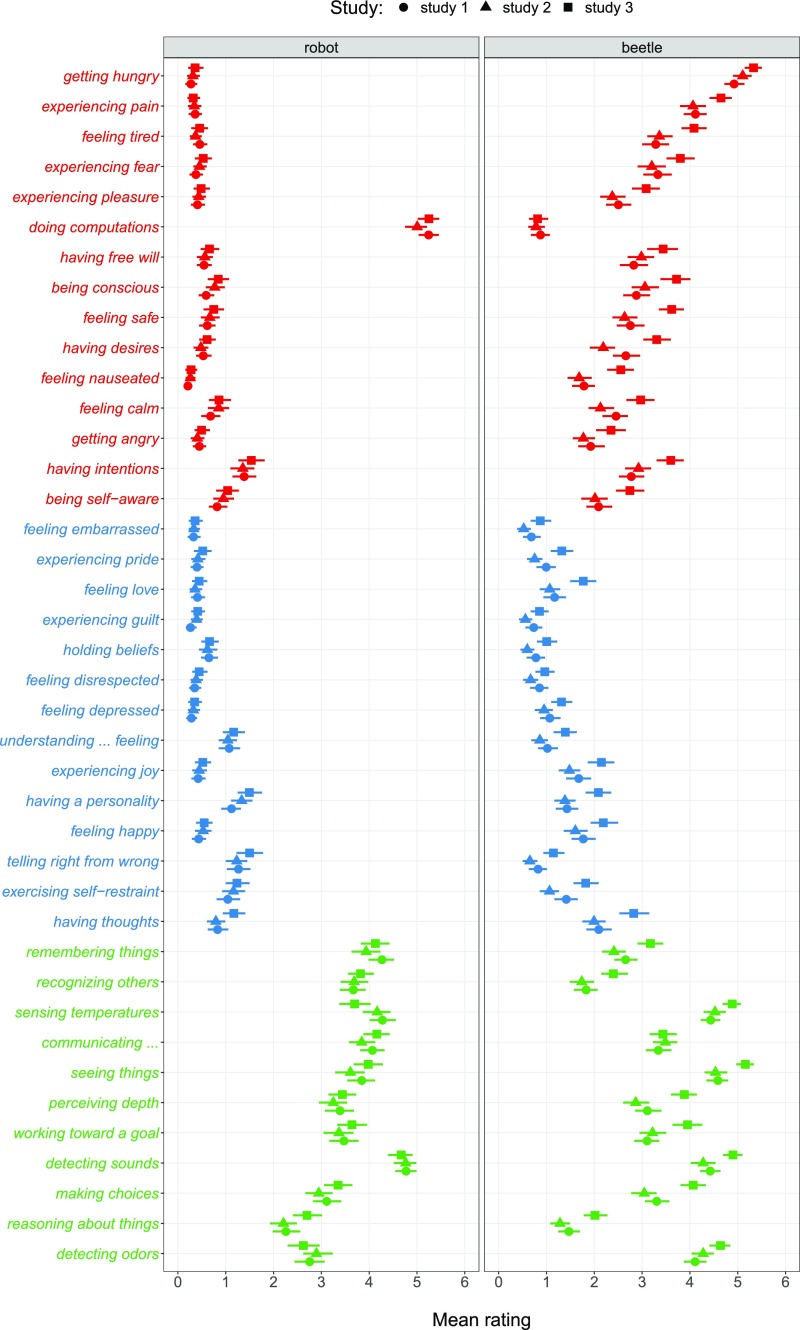

Fig. S2.

Mean ratings of the 40 mental capacities for the two entities in studies 1–3. Participants responded on a scale from 0 (not at all capable) to 6 (highly capable). Error bars are nonparametric bootstrapped 95% CIs. Mental capacities are grouped according to their dominant factor loading in study 1: Items that loaded most strongly on factor 1 (body) are in red, on factor 2 (heart) are in blue, and on factor 3 (mind) are in green.

Fig. S3.

Mean ratings of the 40 mental capacities for all 21 entities in study 4. Participants responded on a scale from 0 (not at all capable) to 6 (highly capable). Error bars are nonparametric bootstrapped 95% CIs. Mental capacities are grouped according to their dominant factor loading in study 4: Items that loaded most strongly on factor 1 (body) are in red, on factor 2 (heart) are in blue, and on factor 3 (mind) are in green.

The first factor corresponded primarily to physiological sensations related to biological needs, as well as the kinds of self-initiated behavior needed to pursue these needs—in other words, abilities related to the physical, biological body. It was the dominant factor for the following items (from greatest to smallest factor loading, according to study 1): getting hungry, experiencing pain, feeling tired, experiencing fear, experiencing pleasure, having free will (see below), being conscious, feeling safe, having desires, feeling nauseated, feeling calm, and having intentions. Across studies, factor 1 accounted for 36–40% of the total variance in the rotated maximal solution.

The second factor corresponded primarily to basic and social emotions, as well as the kinds of social-cognitive and self-regulatory abilities required of a social partner and moral agent. Together, these abilities resonate with the metaphorical sense of heart [and also perhaps with some notions of “spirit” or “soul” (12)]. Across studies, factor 2 was the dominant factor for the items feeling embarrassed, experiencing pride, experiencing guilt, holding beliefs, feeling disrespected, feeling depressed, understanding how others are feeling, telling right from wrong, and exercising self-restraint and accounted for 26–31% of the total variance.

Finally, the third factor corresponded primarily to perceptual–cognitive abilities to detect and use information about the environment, capacities traditionally associated with the mind. Across studies, it was the dominant factor for the items remembering things, recognizing someone, sensing temperatures, communicating with others, seeing things, perceiving depth, working toward a goal, detecting sounds, and making choices and accounted for 16–20% of the total variance.

See Fig. S1 for a 3D representation of this conceptual space (available online at rpubs.com/kgweisman/bodyheartmind_figureS1) and Table 1 for the complete set of factor loadings.

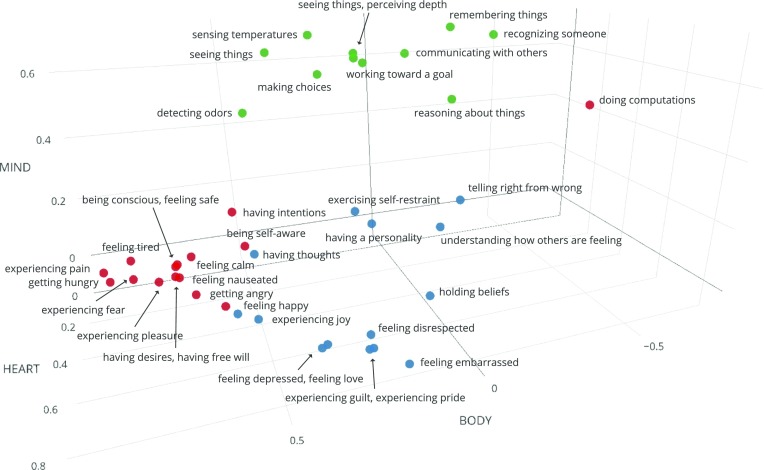

Fig. S1.

Factor loadings for the 40 mental capacities on the three rotated factors in study 1. Items that loaded most strongly on the body factor are in red; items that loaded most strongly on the heart factor are in blue; and items that loaded most strongly on the mind factor are in green. An interactive version is available online at rpubs.com/kgweisman/bodyheartmind_figureS1.

It is worth noting that additional items not listed above loaded equally strongly on more than one factor, in largely sensible ways. Some forms of perception (e.g., detecting odors) were associated with both body and mind. A few basic emotions (e.g., getting angry, feeling happy) and self-awareness (being self-aware, having thoughts) were associated with both body and heart. The capacity for reasoning about things was related to both mind and heart. The capacity for having intentions loaded relatively equally on all three factors. Such cross-loadings might indicate capacities that are considered to be combinations of more basic abilities or capacities that feed into more than one conceptual system.

Two items loaded reliably on a single factor but in ways that surprised us: holding beliefs patterned with the social–emotional items related to the heart much more strongly than the perceptual–cognitive items related to the mind, and having free will tracked the physiological phenomena of the body more closely than the social–emotional capacities of the heart. We suspect that these items reflect dissociations between academic terminology (in which “holding beliefs” is equivalent to thinking that some proposition is true, and “having free will” means something like rational self-determination) and everyday speech [in which “beliefs” might refer to personal or moral convictions (13), and “free will” might connote the ability to initiate behavior without external causes or constraints; see ref. 14 for an extended discussion of folk concepts of free will].

On the whole, however, the general pattern that emerged from these four studies is clear, highly reliable, and quite different from the experience–agency framework that has been widely assumed to characterize folk beliefs about mental life. Given the range of mental capacities included in each study, a number of additional or alternative factors could have emerged, including experience or agency. However, while we were easily able to replicate the experience–agency framework using Gray et al.’s (1) character-comparison paradigm [both with Gray et al.’s original 18 mental capacities and with the 40 mental capacities from our studies 1–4; see Study S1: Replication of Gray et al. (2007) and Study S2: Comparing Characters on 40 Mental Capacities], we saw a very different framework emerge when we asked people to consider the similarities and differences among mental capacities themselves. We observed very similar latent structures across independent analyses, whether participants judged a single edge case in isolation (studies 1 and 2), compared two edge cases that contrasted in biological animacy (study 3), or evaluated a wide range of entities, from inert objects to canonical social partners (study 4). It would be fascinating to explore the cultural and developmental origins of this conceptual system: Are these three ways of reasoning about the behavior of other beings universal, or do they reflect a culturally bounded understanding of the world specific to our US sample? In what ways are intuitions about mental life shaped by culture, religion, education, and personal observation?

Neither experience nor agency emerged as a unitary factor in any of these studies. Instead, distinctions among three varieties of experience—physiological sensations (body), emotions (heart), and perceptual abilities (mind)—were particularly prominent in the latent structure underlying participants’ responses. Beyond this, we were particularly interested, and initially rather surprised, to see that agentic capacities were also distributed across these three factors in reliable ways. We now argue that each of these three factors encompasses conceptually related pairings of experiential and agentic capacities.

These conceptual relationships are especially clear for heart and mind. Within the social–emotional capacities that characterized the heart factor we find both experiences of emotions (e.g., happiness, guilt) and four of the seven items that constituted Gray et al.’s (1) original agency dimension: understanding how others are feeling, telling right from wrong, exercising self-restraint, and (in two of four studies) having thoughts. These items reflect a particularly social and moral form of agency. Likewise, within the perceptual–cognitive capacities that characterized the mind factor are both perceptual experiences (e.g., vision, hearing) and the remainder of Gray et al.’s original agency items: remembering things, communicating with others, and working toward a goal (along with one of our additional agentic items, making choices). This might reflect the role of perception and cognition in action-planning and goal pursuit.

Meanwhile, the collection of items related to the body hints at a conceptual relationship worthy of further investigation. Like the other factors, the body factor included a distinct variety of experience: physiological sensations (e.g., hunger, pain). However, it also included two items that represent important aspects of agency: having free will and having intentions. Although this pattern was unexpected—particularly because it contrasts so vividly with academic accounts of free will as rational self-determination—it emerged across all four studies. We speculate that this reflects the importance of self-initiated behaviors and self-propelled motion in lay people’s understanding of biological life and animacy (11).

To recap, we set out to investigate people’s intuitive ontology of mental life: What do people consider to be the fundamental components of the mind? In four studies, we documented a robust and reliable answer to this question (at least for US adults): Participants’ mental capacity judgments were undergirded by a three-part conceptual structure, resonating with notions of body, heart, and mind.

The body–heart–mind framework is a substantially different perspective on people’s beliefs about mental life than Gray et al.’s experience–agency framework. What accounts for these differences, and how do they play out in everyday social reasoning?

Although further research would be required to answer this question in full, we speculate that these two frameworks—body–heart–mind and experience–agency—capture distinct aspects of social reasoning. On the one hand, people are faced with the question of how to organize and make sense of the wide range of mental capacities that one must take into account to represent another mind. Our studies, in which participants were encouraged to consider the similarities and differences among mental capacities, suggest that the body–heart–mind framework serves this function in the population we tested. On the other hand, people are also faced with the question of how to organize and make sense of the wide range of beings in the world, from humans and animals to supernatural beings and social technologies, and the different roles they play in social interactions (5). Gray et al.’s (1) study, in which participants were encouraged to consider the similarities and differences among characters, suggests that the experience–agency framework might serve this function. If these are indeed two different conceptual frameworks serving distinct roles in social reasoning, this raises interesting questions about when one framework takes precedence over the other or how they might operate in tandem.

Consider the domain of morality. One of the most influential applications of the experience–agency framework has been to argue that moral responsibility is critically tied to attributions of agency, while victimhood (moral patiency) is tied to attributions of experience (5, 6; cf. ref. 7). However, if people were to limit themselves to asking, “What did the perpetrator do, and what did the victim feel?,” they would have only a skeletal understanding of the moral significance of any given event. Beyond thinking about the contrast between the two characters involved in this interaction, an observer might also think about the different aspects of mental life that guide their actions. From a bodily perspective, the observer might ask, “What physical actions did they take? Did anyone experience pain?,” but beyond this, the observer might also adopt a more perceptual–cognitive perspective, wondering, “What did each person see, hear, and know? How was each person understanding the situation?” or a more social–emotional perspective, asking, “Did these people demonstrate self-restraint or consideration of each other’s feelings? What emotions did each person experience?” The observer might even violate the division between agency/responsibility and experience/patiency by taking into account the patient’s agency in assessing his or her moral status (e.g., “Did the patient provoke the agent’s actions?”) or by considering the agent’s experience in judging his or her culpability (e.g., “Does the agent feel remorse?”). In the end, this observer would try to integrate information about different aspects of agency (and perhaps experience) to assess moral responsibility; likewise, he or she might weigh the importance of different varieties of experience (and perhaps agency) to assess victimhood. We speculate that this process of moving back and forth between thinking about the roles that different characters are playing (agent vs. patient) as well as the more nuanced analysis of the different aspects of mental life that guide their behavior (body, heart, mind) may more closely approximate moral reasoning in everyday life.

Another compelling case study of mind perception is a natural experiment currently playing out in much of the developed world: the introduction of increasingly sophisticated “intelligent” and “social” technologies. How are we to make sense of a self-driving car, a robotic caregiver, or a virtual personal assistant? When do these kinds of technologies feel useful, interesting, and fun, and when do they feel uncanny (15)? To take one example, Gray et al.’s work suggests that people perceive robots to be very low on experience and middling on agency (1) and that increasing people’s perceptions of robots’ experience (but not agency) elicits feelings of uncanniness (3). However in the current studies, participants actually endorsed some kinds of experience quite strongly for robots (e.g., sensing temperatures, seeing things) and rejected quite a few agentic abilities (e.g., having free will, telling right from wrong) (Fig. 1 and Figs. S2 and S3), suggesting that there might be more to beliefs and feelings about robots than their capacities for experience and agency, broadly writ. In particular, people’s beliefs and attitudes toward robots might be guided by their conceptual understanding of the components of mental life. For example, thinking about robots and other artificial intelligences as having perceptual–cognitive abilities might feel perfectly comfortable to many people, while entertaining the possibility of technological beings having social–emotional or bodily capacities may be more unsettling. Examining human–robot interactions through the lens of body–heart–mind framework could bring some clarity to these complicated and increasingly relevant issues.

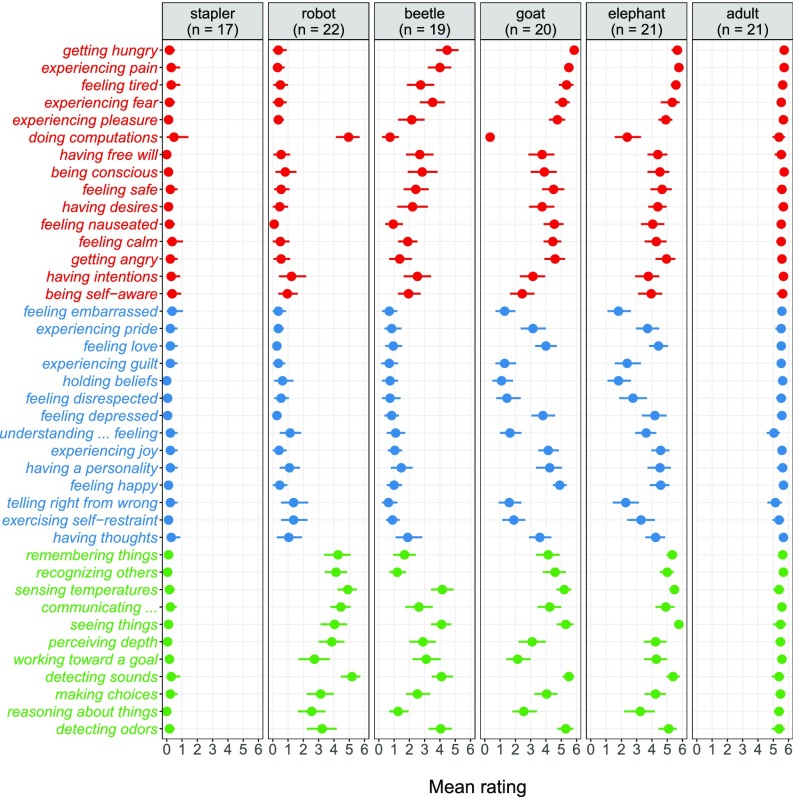

Fig. 1.

Mean ratings of the 40 mental capacities for a subset of the 21 entities in study 4. (Figs. S2 and S3 for mean ratings for the full set of entities in all studies.) Participants responded on a scale from 0 (not at all capable) to 6 (highly capable). Error bars are nonparametric bootstrapped 95% CIs. Mental capacities are grouped according to their dominant factor loading in study 1 (red: body; blue: heart; green: mind). Doing computations was the only item to load negatively on its dominant factor in any study (studies 1–3); in study 4, it loaded positively on its dominant factor (heart).

Just as notions of bodies, hearts, and minds are likely to shape the ways we humanize technological beings, this three-part conceptual structure might also shape the converse processes of dehumanizing and devaluing fellow human beings. Claims that some people are somehow less than human—in particular, that they lack certain mental capacities—have been used to justify oppression throughout history and through the present day (e.g., ref. 16). If experience and agency are understood to be the two components of mental life, as has been widely assumed, it is logical to suppose that there may be two corresponding forms of dehumanization: the denial of experience, and the denial of agency (17). However, current theories of dehumanization are considerably richer and more nuanced than this (18). The body–heart–mind framework might be a more useful framework for making sense of dehumanization, which, from our perspective, might take the form of augmenting or diminishing mental capacities in any of our three domains (body, heart, or mind). This resonates well with most recent work on dehumanization, which has focused on the difference between “mechanistic dehumanization,” in which a person is likened to an unfeeling machine (perhaps by way of emphasizing their mind at the expense of their body and heart), and “animalistic dehumanization,” in which a person is likened to an irrational animal (perhaps by way of emphasizing their body over their heart or mind). Interestingly, this alignment also suggests that there may be additional forms of dehumanization that have yet to be fully explored—in particular, a form of dehumanization that overemphasizes the heart, relative to the body or mind. In this way, the body–heart–mind framework might open new avenues for exploration that would be obscured by the constraints of the experience–agency framework.

As Gray et al.’s pioneering work highlighted, mind perception is at the core of many of the most interesting and important social phenomena. Our work has demonstrated that the body–heart–mind framework captures people’s intuitions about the fundamental components of mental life and thus has the potential to reorient ongoing investigation of the links between mind perception and social reasoning.

Materials and Methods

The studies reported in this paper were approved by the Stanford Administrative Panel on Human Subjects in Nonmedical Research. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. Stimuli, surveys, data, and analysis code for studies 1–4 are available at https://osf.io/m3gwu/.

In these studies, participants rated target characters on 40 mental capacities. The goal of these studies was to assess lay people’s understanding of the structure of mental life by evaluating which mental capacities tend to hang together in people’s judgments.

Materials.

Surveys.

Studies were administered online. Participants first saw a photograph of the character(s) they were assigned to evaluate and read, “You have been assigned to evaluate the following entity: [target]. On the following page, you will see a list of mental capacities. For each mental capacity, please indicate the extent to which you believe a [target] has this capacity. Please note: We care only about your opinion or best guess—please do not do any external research about these questions.”

Participants then proceeded to a page featuring the same photograph(s), with the following text prominently displayed: “On a scale of 0 (Not at all capable) to 6 (Highly capable), how capable is a [target] of … ?” This was followed by the 40 mental capacities and one attention check (“Please select 4”), presented in a random order for each participant. Participants were required to answer every question.

In studies 1, 2, and 4, each participant evaluated one randomly assigned target character. In study 3, every participant evaluated two target characters presented side by side (left–right position was determined randomly). See Characters, below.

Finally, participants were presented with demographics questions (Table S1).

Table S1.

Demographic information for all participants in studies 1–4, as indicated by self-report

| Question/response options | Study 1 | Study 2 | Study 3 | Study 4 |

| Age, in years, estimated from reported year of birth, range (median) | 19–75 (32) | 20–70 (33) | 20–68 (33) | 18–70 (34) |

| Gender, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 240 (59) | 199 (49) | 202 (50) | 223 (52) |

| Female | 163 (40) | 205 (50) | 198 (50) | 205 (48) |

| Other/prefer not to say | 2 (<1) | 2 (<1) | 0 (0) | 3 (1) |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | ||||

| White or European Am. | 290 (72) | 314 (77) | 290 (73) | 330 (77) |

| East Asian | 36 (9) | 22 (5) | 30 (8) | 26 (6) |

| Black or African Am. | 23 (6) | 26 (6) | 38 (10) | 26 (6) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 18 (4) | 21 (5) | 16 (4) | 20 (5) |

| South Asian | 8 (2) | 8 (2) | 4 (1) | 4 (1) |

| Another Asian ethnicity | 2 (<1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (1) |

| Native Am., Am. Indian, or Alaska Native | 2 (<1) | 2 (<1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| Middle Eastern | 2 (<1) | 1 (<1) | 0 (0) | 1 (<1) |

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 2 (<1) | 1 (<1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Multiple races/ethnicities | 20 (5) | 8 (2) | 22 (6) | 16 (4) |

| Other/prefer not to say | 2 (<1) | 3 (1) | 0 (0) | 3 (1) |

| Religious background, n (%) | ||||

| Not religious | 201 (50) | 200 (49) | 190 (48) | — |

| Christian | 168 (42) | 165 (41) | 176 (44) | — |

| Buddhist | 5 (1) | 9 (2) | 10 (3) | — |

| Jewish | 9 (2) | 7 (2) | 0 (0) | — |

| Muslim | 2 (<1) | 5 (1) | 6 (2) | — |

| Hindu | 2 (<1) | 1 (<1) | 0 (0) | — |

| Another religion | 6 (1) | 10 (2) | 6 (2) | — |

| Multiple religions | 3 (1) | 2 (<1) | 0 (0) | — |

| Prefer not to say | 9 (2) | 7 (2) | 12 (3) | — |

| Education, n (%) | ||||

| Graduate or professional degree | — | — | — | 51 (12) |

| Some amount of graduate school | — | — | — | 23 (5) |

| Bachelor’s degree | — | — | — | 146 (34) |

| Associate’s degree | — | — | — | 51 (12) |

| Some amount of college | — | — | — | 111 (26) |

| High school diploma | — | — | — | 41 (10) |

| Some amount of high school or less | — | — | — | 3 (1) |

| Prefer not to say | — | — | — | 5 (1) |

Dash indicates that the corresponding questions were not asked of the participants in that study. Am., American.

Characters.

For all studies, each target character was accompanied by a brief label (e.g., “a beetle”) and a color photograph of that character. Participants were not provided with any further information about these characters.

For studies 1–3, the list of characters included a beetle and a robot.

For study 4, the list of characters again included a beetle and a robot, as well as a stapler, a car, a computer, a microbe, a fish, a blue jay, a frog, a mouse, a goat, a dog, a bear, a dolphin, an elephant, a chimpanzee, a fetus, a person in a persistent vegetative state, an infant, a child, and an adult. Note that this set of characters included close variants of all 13 characters used in Gray et al.’s (1) dimensions of mind perception study, with the following exceptions: We included only one typical human adult, instead of three, in favor of including a wider range of entities toward the middle of the spectrum from inert objects to humans, and we excluded the recently deceased adult and God, whose mental capacities we anticipated would be difficult or confusing to evaluate exclusively, particularly for nonreligious participants.

See Table S2 for descriptions of these images, links to image sources, and condition randomization for each study.

Table S2.

Information about target characters and condition randomization for studies 1–4

Electronic copies are available at https://osf.io/qnexa/.

Participants in study 3 (n = 200) evaluated both the beetle and the robot simultaneously.

Mental capacities.

The 40 mental capacities included in all studies were generated from an a priori conceptual analysis of candidate ontological categories of mental life, with the constraint that each category should include at least five items of varying valence, complexity, and phrasing:

-

i)

Affective experiences: feeling happy, feeling depressed, experiencing fear, getting angry, feeling calm, experiencing joy

-

ii)

Perceptual abilities: detecting sounds, seeing things, sensing temperatures, detecting odors, perceiving depth

-

iii)

Physiological sensations related to biological needs: getting hungry, feeling tired, experiencing pain, feeling nauseated, feeling safe

-

iv)

Cognitive abilities: doing computations, having thoughts, reasoning about things, remembering things, holding beliefs

-

v)

Agentic capacities: having free will, making choices, exercising self-restraint, having intentions, working toward a goal

-

vi)

Social abilities: feeling love, recognizing someone, communicating with others, experiencing guilt, feeling disrespected, understanding how others are feeling, feeling embarrassed

-

vii)

Additional items that fell into none or more than one of these categories: being conscious, being self-aware, experiencing pleasure, having desires, telling right from wrong, having a personality, experiencing pride

Note that this set of mental capacities included close variants of all 18 mental capacities used in Gray et al.’s (1) original experience–agency study (Table 1).

Methods.

Participants.

Participants in all studies participated via Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk). All participants had gained approval for ≥95% of previous work on MTurk (≥50 assignments), had verified accounts based in the United States, and indicated that they were ≥18 y old. Repeat participation (within each study and across studies) was prevented.

Study 1 (n = 405): Participants were paid $0.30 (median duration: 2.67 min). An additional 48 respondents were excluded for not completing the survey (n = 14), failing the attention check (i.e., failing to select “4” for an item that read “Please select 4”; n = 19), or not providing a year of birth (n = 15).

Study 2 (n = 406): Participants were paid $0.30 (median duration: 2.52 min). An additional 13 respondents were excluded for not providing a year of birth.

Study 3 (n = 400): Participants were paid $0.50 (median duration: 5.46 min). An additional 24 respondents were excluded for not completing the survey (n = 13), failing the attention check (n = 7), or not providing a year of birth (n = 4).

Study 4 (n = 431): Participants were paid $0.30 (median duration: 2.88 min). An additional 40 respondents were excluded for not completing the survey (n = 15), failing the attention check (n = 24), or not providing a year of birth (n = 1).

See Table S1 for demographic information.

Recruitment.

Participants were recruited using the Human Intelligence Task title “Short psychology study judgments of familiar things” along with a time estimate, a description reading, “Complete a very short psychology study,” and the keywords “psychology, survey, study.” Participants were recruited between December 14, 2015, and January 14, 2016.

Statistical analysis.

For each study we conducted exploratory factor analyses using Pearson correlations to find the minimum residual solution. [Note that factor analyses using polychoric correlations and/or oblimin rotation, principal components analyses (PCAs), correspondence analyses, and item response analyses all yielded similar latent structures.]

We first examined unrotated maximal solutions. To determine the maximum number of factors to extract, we used the following rule of thumb: With p observations per participant, we can extract a maximum of k factors, where (p – k) × 2 > (p + k), i.e., k < p/3. Thus, with 40 mental capacity items, we could extract a maximum of 13 factors.

To determine how many factors to retain, we used the following preset retention criteria, considering the unrotated maximal (13-factor) solution: Each factor must (i) have an eigenvalue >1.0, (ii) individually account for >5% of the total variance, and (iii) be the dominant factor (i.e., the factor with the highest factor loading) for at least one mental capacity item after rotation. In all studies, this yielded exactly three factors.

In the primary analysis for each study, we examined and interpreted varimax-rotated solutions, extracting only the number of factors that meet the retention criteria just described. See Table 1 for factor loadings for all mental capacities on these three rotated factors, for all studies.

See Supporting Information for methods, results, and discussion of two additional studies: Study S1 (results: Table S3) and Study S2 (results: Table S4).

Table S3.

Factor loadings from PCA for study S1 (after varimax rotation)

| Original factor affiliation | Item | Dimension 1: Agency | Dimension 2: Experience |

| Agency | Planning | 0.91 | 0.32 |

| Agency | Thought | 0.85 | 0.49 |

| Agency | Memory | 0.81 | 0.33 |

| Agency | Morality | 0.79 | 0.33 |

| Experience | Pride | 0.76 | 0.52 |

| Agency | Emotion recognition | 0.73 | 0.39 |

| Experience | Embarrassment | 0.72 | 0.68 |

| Agency | Communication | 0.72 | 0.68 |

| Experience | Personality | 0.67 | 0.55 |

| Agency | Self control | 0.64 | 0.24 |

| Experience | Rage | 0.59 | 0.51 |

| Experience | Pain | 0.30 | 0.92 |

| Experience | Fear | 0.38 | 0.89 |

| Experience | Hunger | 0.28 | 0.88 |

| Experience | Pleasure | 0.51 | 0.78 |

| Experience | Joy | 0.51 | 0.72 |

| Experience | Consciousness | 0.51 | 0.68 |

| Experience | Desire | 0.63 | 0.65 |

| Total variance explained (varimax rotation), % | 42 | 39 | |

Loadings greater than or equal to 0.60 or less than or equal to −0.60 are in boldface type. Items are listed according to their dominant factor loading. The first column gives the original factor affiliations from Gray et al. (1).

Table S4.

Factor loadings from PCA for study S2 (after varimax rotation)

| A priori category | Item | Dimension 1: Agency | Dimension 2: Experience |

| Telling right from wrong* | 0.95 | 0.24 | |

| SOC | Recognizing someone | 0.88 | 0.44 |

| SOC | Feeling disrespected | 0.80 | 0.57 |

| SOC | Understanding how others are feeling* | 0.80 | 0.46 |

| AGE | Working toward a goal* | 0.79 | 0.40 |

| COG | Remembering things* | 0.79 | 0.25 |

| AGE | Having intentions | 0.77 | 0.59 |

| COG | Holding beliefs | 0.77 | 0.42 |

| COG | Doing computations | 0.77 | 0.16 |

| COG | Reasoning about things | 0.77 | 0.44 |

| AGE | Making choices | 0.77 | 0.33 |

| Being self-aware | 0.76 | 0.51 | |

| PER | Seeing things | 0.71 | 0.51 |

| PER | Perceiving depth | 0.70 | 0.12 |

| Having a personality† | 0.67 | 0.51 | |

| SOC | Experiencing guilt | 0.67 | 0.50 |

| AGE | Exercising self-restraint* | 0.63 | 0.01 |

| SOC | Feeling embarrassed† | 0.63 | 0.55 |

| SOC | Communicating with others* | 0.62 | 0.38 |

| EMO | Getting angry† | 0.61 | 0.58 |

| Being conscious† | 0.61 | 0.42 | |

| AGE | Having free will | 0.58 | 0.57 |

| Experiencing pride† | 0.55 | 0.51 | |

| PHY | Feeling safe | 0.47 | 0.38 |

| EMO | Feeling calm | 0.31 | 0.25 |

| PHY | Experiencing pain† | 0.18 | 0.87 |

| EMO | Experiencing fear† | 0.39 | 0.87 |

| PHY | Getting hungry† | 0.13 | 0.83 |

| PHY | Feeling tired | 0.08 | 0.82 |

| Having desires† | 0.53 | 0.81 | |

| PHY | Feeling nauseated | 0.21 | 0.81 |

| Experiencing pleasure† | 0.42 | 0.76 | |

| EMO | Feeling happy | 0.49 | 0.74 |

| PER | Sensing temperatures | 0.38 | 0.71 |

| PER | Detecting odors | 0.41 | 0.70 |

| COG | Having thoughts* | 0.54 | 0.65 |

| SOC | Feeling love | 0.58 | 0.64 |

| EMO | Feeling depressed | 0.38 | 0.58 |

| EMO | Experiencing joy† | 0.54 | 0.58 |

| PER | Detecting sounds | 0.48 | 0.49 |

| Total variance explained (varimax rotation), % | 34 | 29 | |

Loadings greater than or equal to 0.60 or less than or equal to −0.60 are in boldface type. Items are listed according to their dominant factor loading. Each item is listed with its a priori category membership (first column): AGE, agentic; COG, cognitive; EMO, emotional; PER, perceptual; PHY, physiological; SOC, social; and other/multiple (unmarked).

Agency dimension from Gray et al. (1).

Experience dimension from Gray et al. (1).

To supplement the analyses and results reported in the main text, we have included the following information in this document:

-

i)

Additional studies: study S1, a direct replication of Gray et al.'s (2007) original dimensions of mind perception study (1), and study S2, a conceptual replication of ref. 1 using Gray et al.’s experimental paradigm with our expanded set of mental capacities

-

ii)

Further details on the exploratory factor analysis results from studies 1–4

-

iii)

Additional figures: Fig. S1, the 3D space of factor loadings for study 1; Fig. S2, mean ratings of all 40 mental capacities for the two entities used in studies 1–3; and Fig. S3, mean ratings of all 40 mental capacities for the 21 entities used in study 4

-

iv)

Additional tables: Table S1, demographic information for participants in studies 1–4; Table S2, information about target characters and condition randomization for studies 1–4; Table S3, factor loadings from a PCA of study S1; and Table S4, factor loadings from a PCA of study S2

Study S1: Replication of Gray et al. (2007)

Before running the studies reported in the main text, we conducted a replication of Gray et al.’s (1) original dimensions of mind perception study.

Study S1 Materials.

We used the characters and mental capacities described in the supplementary materials for the original study (1) and character photographs provided by the first author of the original study. As in the original study, each participant evaluated all 78 possible pairs of 13 characters (within subjects) on one of 18 mental capacities (between subjects).

We note one variation on the original materials: We referred to characters only with brief descriptions (e.g., “green frog,” “Charlie, family dog”). This is in contrast to the original study, which provided more extensive information about the characters [e.g., “The Green Frog can be found throughout eastern North America. This classic ‘pond frog’ is medium-sized and green or bronze in color. Daily life includes seeking out permanent ponds or slow streams with plenty of vegetation”; “Charlie is a 3-y-old Springer spaniel and a beloved member of the Graham family” (1)].

Study S1 Methods.

Participants.

Two hundred forty-eight adults participated via MTurk (n = 10–17 per mental capacity). All participants had gained approval for ≥95% of previous work on MTurk (≥50 assignments), had verified accounts based in the United States, and indicated that they were ≥18 y old. Repeat participation was prevented. Participants were paid $0.75 for about 10 min of their time.

Statistical analyses.

We followed the original analyses as described in the supplementary materials for the original study (1) as exactly as possible: We first computed mean relative ratings for each of the 13 characters, for each of the 18 mental capacities, and then conducted a PCA via singular-value decomposition on these means. (Note that exploratory factor analyses using Pearson correlations yielded very similar results.)

To determine how many dimensions to retain, we used the following retention criteria, considering the unrotated maximal (five-dimension) solution: (i) Each dimension must have an eigenvalue >1.0 and (ii) each dimension must individually account for >5% of the total variance in the maximal solution.

Study S1 Results.

We observed evidence for a two-dimensional structure underlying participants’ judgments, and these two dimensions were very similar to the experience–agency framework reported in the original dimensions of mind perception study (1). See Table S3 for all factor loadings.

In the rotated maximal solution, the first dimension accounted for 42% of the total variance. In the rotated two-dimensional solution, dimension 1 was the dominant dimension for the following mental capacities (from greatest to smallest factor loading): planning, thought, memory, morality, pride, emotion recognition, embarrassment, communication, personality, self-control, and rage. This is similar to the agency dimension originally reported, which accounted for self-control, morality, memory, emotion recognition, planning, communication, and thought (1).

The second rotated dimension accounted for 39% of the total variance in the rotated maximal solution. In the rotated two-dimensional solution, dimension 2 was the dominant dimension for the following mental capacities (from greatest to smallest factor loading): pain, fear, hunger, pleasure, joy, consciousness, and desire. This is similar to the experience dimension originally reported, which accounted for hunger, fear, pain, pleasure, rage, desire, personality, consciousness, pride, embarrassment, and joy (1).

One small difference between our findings and the original findings was that four of the 18 mental capacities that loaded slightly more strongly on the original experience dimension instead loaded slightly more strongly on the agency dimension in our replication: pride, embarrassment, personality, and rage; however, we note that in both the original study and this replication these items had very similar loadings on both dimensions. We also note that our agency and experience dimensions accounted for roughly equal amounts of variance in the rotated maximal solution (in contrast to the original study, which reported that experience and agency accounted for 88% and 8% of the variance, respectively).

Study S1 Discussion.

We consider this to be a very close replication of the findings reported in the original dimensions of mind perception study (1).

Study S2: Comparing Characters on 40 Mental Capacities

Study S2 was designed to illuminate the origin of the differences between the results of studies 1–4 (which revealed a distinction between physiological sensations related to the body, social–emotional capacities related to the heart, and perceptual–cognitive abilities related to the mind) and the results of Gray et al. (1), which revealed a distinction between experience and agency. After running the studies reported in the main text, we conducted an additional study to test the hypothesis that these differences were due primarily to differences in the study paradigm, namely, asking each participant to compare a series of characters while focusing on just one mental capacity (as in ref. 1 and study S1) vs. asking each participant to rate a series of mental capacities while focusing on just one (or two) characters (as in our studies 1–4; see main text). If this hypothesis is true, then substituting our list of 40 mental capacities into Gray et al.’s original paired-comparison paradigm should yield the experience–agency framework. If, instead, the differences in results are due to the relatively wider range of mental capacities used in our studies 1–4, then importing this longer set of mental capacities into Gray et al.’s paradigm might result in something more like our body–heart–mind framework.

Study S2 Materials.

We used the characters and corresponding photographs employed in Gray et al.’s (1) original study with the shorted character descriptions used in our replication (study S1, above). Again, each participant evaluated all 78 possible pairs of 13 characters (within subjects) for one mental capacity. However, instead of using the 18 mental capacities used in Gray et al.’s original study, we included the 40 mental capacities from studies 1–4 (see main text).

Study S2 Methods.

Participants.

Five hundred forty-nine adults participated via MTurk (n = 7–22 per mental capacity). All participants had gained approval for ≥95% of previous work on MTurk (≥50 assignments), had verified accounts based in the United States, and indicated that they were ≥18 y old. Repeat participation was prevented. Participants were paid $0.75 for about 10 min of their time.

Statistical analyses.

As in the direct replication described above (study S1), we followed Gray et al.’s original analyses as exactly as possible: We first computed mean relative ratings for each of the 13 characters, for each of the 40 mental capacities and then conducted a PCA via singular-value decomposition on these means. (Note that exploratory factor analyses using Pearson correlations yielded very similar results.)

To determine how many dimensions to retain, we used the following retention criteria, considering the unrotated maximal solution: (i) Each dimension must have an eigenvalue >1.0 and (ii) each dimension must individually account for >5% of the total variance in the maximal solution.

Study S2 Results.

Study S2, which used Gray et al.’s character-comparison paradigm with our larger set of mental capacities (as used in studies 1–4; see main text), yielded evidence for a two-dimensional structure underlying participants’ judgments. As in both Gray et al.’s (1) original study and our direct replication (study S1), these two dimensions corresponded to something close to agency and experience, respectively. See Table S4 for all factor loadings.

The first dimension accounted for 34% of the total variance in the rotated maximal solution. In the rotated two-dimensional solution, dimension 1 was the dominant dimension for the following mental capacities (from greatest to smallest factor loading): telling right from wrong, recognizing someone, feeling disrespected, understanding how others are feeling, working toward a goal, remembering things, having intentions, holding beliefs, doing computations, reasoning about things, making choices, being self-aware, seeing things, perceiving depth, having a personality, experiencing guilt, exercising self-restraint, feeling embarrassed, communicating with others, getting angry, being conscious, having free will, experiencing pride, feeling safe, and feeling calm.

Viewing these results through the lens of the experience–agency framework, dimension 1 seems to correspond to something close to agency: It is defined primarily by capacities for cognition and action, in the particular sense of goal pursuit and moral agency. Indeed, among the items with the strongest loadings on dimension 1 were close variants of most of Gray et al.’s original agency items, including morality, emotion recognition, planning, memory, self control, and communication (1). However, we note two differences between this dimension and the original agency dimension: (i) In the original study, thought was also associated with the agency dimension (1), while in this study it loaded more strongly on the second dimension than on the first (see below), and (ii) this dimension includes quite a few items that correspond to experience, in the broadest sense of the term (e.g., perceiving depth, being self-aware, feeling disrespected, seeing things, being conscious, experiencing guilt, feeling calm, experiencing pride, feeling embarrassed, getting angry, feeling safe). In some cases, these items also loaded relatively strongly on the second dimension.

In the rotated maximal solution, the second dimension accounted for 29% of the total variance. In the rotated two-dimensional solution, dimension 2 was the dominant dimension for the following mental capacities (from greatest to smallest factor loading): experiencing pain, experiencing fear, getting hungry, feeling tired, having desires, feeling nauseated, experiencing pleasure, feeling happy, sensing temperatures, detecting odors, having thoughts, feeling love, feeling depressed, experiencing joy, and detecting sounds.

Through the lens of the experience–agency framework, dimension 1 seems to correspond to something close to experience: It included almost exclusively capacities for bodily sensations, emotions, and some perceptual experiences. Among these items were close variants of many of the original experience items, including hunger, fear, pain, pleasure, desire, and joy (1). We do note, however, that in the original study rage, personality, consciousness, pride, and embarrassment were also associated with the experience dimension, while in this study similar items loaded slightly more strongly on the first dimension than on the second.

Capacities related to the body, heart, and mind (as defined by studies 1–4; see main text) were distributed across these two dimensions. With regard to the body, capacities for self-initiated action (e.g., having free will, having intentions) were included in dimension 1, while physiological sensations (e.g., getting hungry, experiencing pain) were included in dimension 2. With regard to the heart, capacities related to moral agency 2 (e.g., telling right from wrong, exercising self-restraint) were included in dimension, while emotional experiences were distributed across dimension 1 (e.g., experiencing guilt, experiencing pride) and dimension 2 (e.g., feeling happy, feeling depressed). Finally, with regard to the mind, items related to goal pursuit (e.g., making choices, working toward a goal) were included in dimension 1 while perceptual abilities were distributed across dimension 1 (e.g., perceiving depth, seeing things) and dimension 2 (e.g., sensing temperatures, detecting odors).

Study S2 Discussion.

These results support the hypothesis that the differences between our primary findings (studies 1–4; see main text) and Gray et al.’s (1) original findings were due primarily to differences in the study paradigm: Gray et al.’s approach of asking each participant to compare a series of characters, while focusing on just one mental capacity, produces dimensions similar to experience and agency even when a longer, more diverse range of mental capacities is included in the analysis.

Studies S1 and S2 General Discussion

Taken together, the results of studies S1 and S2 suggest that the experience–agency framework is easily replicable and that differences between the original study and our studies 1–4 are due to the experimental design: In Gray et al.’s original paradigm participants compared many characters while considering only one mental capacity, whereas participants in our studies 1–4 evaluated many mental capacities while considering only one or two characters. The experience–agency framework seems to capture something reliable about how people compare contrast and rank different social beings in terms of their relative mental capacities—but, as it turns out, the dimensions of this conceptual space differ from people’s intuitive ontology of mental capacities themselves.

Studies 1–4: Additional Information on Exploratory Factor Analyses

The goal of studies 1–4 was to assess lay people’s understanding of the structure of mental life by evaluating which mental capacities tend to hang together in people’s judgments. To do this, we conducted independent exploratory factor analyses for each study. These analyses all revealed the same three-factor structure, with each factor encompassing both a particular variety of experience and a related variety of agency. The first factor, which we have characterized as body, tended to include capacities for physiological sensations and self-initiated behavior. The second factor, which we have characterized as heart, tended to include capacities for basic and social emotions and morality. The third factor, which we have characterized as mind, tended to include capacities for perception, cognition, and goal-directed action.

Here we review the details of the individual analyses for each study in more detail. See Table 1 for factor loadings for all mental capacities on these three rotated factors for all studies. See also Figs. S2 and S3 for mean ratings of each mental capacity for all entities in studies 1–4.

Studies 1–4 Results.

As described in the main text, we first examined unrotated maximal (13-factor) solutions, using Pearson correlations to find minimum residual solutions. We used the following preset criteria to determine how many factors to retain: Each factor must (i) have an eigenvalue >1.0, (ii) individually account for >5% of the total variance, and (iii) be the dominant factor (i.e., the factor with the highest factor loading) for at least one mental capacity item after rotation. We then examined and interpreted varimax-rotated solutions, extracting only the number of factors that met these retention criteria.

Study 1: Two edge cases (beetle vs. robot) between subjects.

Three factors met our retention criteria, suggesting that there were three latent constructs underlying participants’ responses. These first three factors accounted for 85% of the total variance in the rotated maximal solution (36, 31, and 18%, respectively).

In a rotated three-factor solution, factor 1 was the dominant factor for the following capacities (listed from greatest to smallest factor loading): getting hungry, experiencing pain, feeling tired, experiencing fear, experiencing pleasure, doing computations (negative loading), having free will, being conscious, feeling safe, having desires, feeling nauseated, feeling calm, getting angry, having intentions, and being self-aware.

Factor 2 was the dominant factor for the following capacities: feeling embarrassed, experiencing pride, feeling love, experiencing guilt, holding beliefs, feeling disrespected, feeling depressed, understanding how others are feeling, experiencing joy, having a personality, feeling happy, telling right from wrong, exercising self-restraint, and having thoughts.

Finally, factor 3 was the dominant factor for the following capacities: remembering things, recognizing someone, sensing temperatures, communicating with others, seeing things, perceiving depth, working toward a goal, detecting sounds, making choices, reasoning about things, and detecting odors.

Study 2: Direct replication of study 1.

Three factors met our retention criteria, suggesting that there were three latent constructs underlying participants’ responses. These first three factors accounted for 81% of the total variance in the rotated maximal solution (35, 28, and 19%, respectively).

In a rotated three-factor solution, factor 1 was the dominant factor for the following capacities (listed from greatest to smallest factor loading): getting hungry, experiencing pain, feeling tired, experiencing fear, being conscious, experiencing pleasure, doing computations (negative loading), having free will, feeling safe, having desires, feeling nauseated, getting angry, feeling calm, having intentions, and having thoughts.

Factor 2 was the dominant factor for experiencing guilt, experiencing pride, feeling embarrassed, feeling disrespected, feeling depressed, feeling love, understanding how others are feeling, holding beliefs, feeling happy, having a personality, telling right from wrong, experiencing joy, exercising self-restraint, and being self-aware.

Finally, factor 3 was the dominant factor for communicating with others, detecting sounds, remembering things, working toward a goal, making choices, seeing things, recognizing someone, sensing temperatures, perceiving depth, reasoning about things, and detecting odors.

Study 3: Two edge cases (beetle vs. robot) within subjects.

Three factors met our retention criteria, suggesting that there were three latent constructs underlying participants’ responses. These first three factors accounted for 82% of the total variance in the rotated maximal solution (40, 26, and 16%, respectively).

In a rotated three-factor, solution factor 1 was the dominant factor for the following capacities (listed from greatest to smallest factor loading): getting hungry, experiencing pain, feeling tired, experiencing fear, doing computations (negative loading), having desires, experiencing pleasure, feeling safe, being conscious, having free will, feeling nauseated, feeling calm, having intentions, detecting odors, and being self-aware.

Factor 2 was the dominant factor for experiencing pride, experiencing guilt, feeling disrespected, feeling embarrassed, feeling depressed, feeling love, experiencing joy, feeling happy, holding beliefs, understanding how others are feeling, having a personality, getting angry, exercising self-restraint, having thoughts, and telling right from wrong.

Finally, factor 3 was the dominant factor for detecting sounds, remembering things, recognizing someone, communicating with others, sensing temperatures, perceiving depth, making choices, reasoning about things, working toward a goal, and seeing things.

Study 4: 21 characters between subjects.

Three factors met our retention criteria, suggesting that there were three latent constructs underlying participants’ responses. These first three factors accounted for 88% of the total variance in the rotated maximal solution (39, 29, and 20%, respectively).

In a rotated three-factor solution factor 1 was the dominant factor for the following capacities (listed from greatest to smallest factor loading): experiencing pain, feeling tired, getting hungry, experiencing fear, experiencing pleasure, feeling calm, feeling happy, feeling safe, experiencing joy, feeling nauseated, having desires, getting angry, feeling love, being conscious, having a personality, having thoughts, having free will, detecting odors, and having intentions (equal factor loadings on factor 1 and factor 2).

Factor 2 was the dominant factor for holding beliefs, experiencing guilt, feeling embarrassed, telling right from wrong, feeling disrespected, experiencing pride, understanding how others are feeling, exercising self-restraint, reasoning about things, feeling depressed, being self-aware, and doing computations.

Finally, factor 3 was the dominant factor for detecting sounds, sensing temperatures, communicating with others, remembering things, perceiving depth, seeing things, making choices, recognizing someone, and working toward a goal.

Studies 1–4 Summary.

Across all studies, the first rotated factor corresponded primarily to physiological sensations related to biological needs (e.g., hunger, pain) and also included capacities for self-initiated behavior (e.g., free will, intentions). The second rotated factor corresponded primarily to social-emotional experiences of basic and social emotions (e.g., pride, guilt) and also included moral agency (e.g., emotion recognition, telling right from wrong). The third rotated factor corresponded primarily to perceptual-cognitive abilities to detect and use information about the environment (e.g., vision, memory) and also included goal pursuit (e.g., choices, goals). As we argue in the main text, these factors resonate with traditional notions of body, heart, and mind, respectively.

Studies 1 and 2 Preregistered Analysis Plan.

When we designed studies 1 and 2, we initially planned to conduct dimension reduction analyses for each condition (beetle vs. robot) separately. However, we now consider this analysis plan to be fundamentally flawed: Each of these separate analyses is only capable of surfacing factors that highlight substantial disagreement among participants within that condition, thus failing to capture key differences in attributions of mental capacities to the different target characters. This analysis plan also would have precluded examining multiple characters within subjects (study 3) or expanding the range of characters beyond these two edge cases (study 4).

Nonetheless, when we analyze studies 1 and 2 in this way the results are generally consistent with the findings reported here: The most reliable finding within each condition is that participants distinguish between emotional and perceptual varieties of experience. See https://osf.io/zd3mu for preregistered analyses and analysis scripts for study 2 (a direct replication of study 1, which was preregistered before conducting studies 3 and 4).

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Susan Gelman and Paul Bloom, whose challenging and insightful reviews truly pushed our thinking forward. We also thank Sophie Bridgers, Eleanor Chestnut, and David McClure for feedback on the manuscript; Heather Gray for providing information and materials for the replication study; and Michael Frank for guidance in conducting the replication. This material is based on work supported by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program under Grant DGE-114747 (to K.W.), and by a William R. and Sara Hart Kimball Stanford Graduate Fellowship (to K.W.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data deposition: The data for studies 1-4 have been deposited in an Open Science Framework (OSF) project, https://osf.io/m3gwu/.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1704347114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Gray HM, Gray K, Wegner DM. Dimensions of mind perception. Science. 2007;315:619. doi: 10.1126/science.1134475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gray K, Knobe J, Sheskin M, Bloom P, Barrett LF. More than a body: Mind perception and the nature of objectification. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2011;101:1207–1220. doi: 10.1037/a0025883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gray K, Wegner DM. Feeling robots and human zombies: Mind perception and the uncanny valley. Cognition. 2012;125:125–130. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2012.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gray K, Jenkins AC, Heberlein AS, Wegner DM. Distortions of mind perception in psychopathology. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:477–479. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015493108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gray K, Waytz A, Young L. The moral dyad: A fundamental template unifying moral judgment. Psychol Inq. 2012;23:206–215. doi: 10.1080/1047840X.2012.686247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gray K, Young L, Waytz A. Mind perception is the essence of morality. Psychol Inq. 2012;23:101–124. doi: 10.1080/1047840X.2012.651387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sytsma J, Machery E. The two sources of moral standing. Rev Philos Psychol. 2012;3:303–324. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Epley N, Waytz A. Mind perception. In: Fiske ST, Gilbert DT, Lindzey G, editors. Handbook of Social Psychology. Wiley; Hoboken, NJ: 2010. pp. 498–541. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wellman HM, Gelman SA. Cognitive development: Foundational theories of core domains. Annu Rev Psychol. 1992;43:337–375. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ps.43.020192.002005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wellman HM, Phillips AT, Rodriguez T. Young children’s understanding of perception, desire, and emotion. Child Dev. 2000;71(4):895–912. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gelman R, Spelke E. The development of thoughts about animate and inanimate objects: Implications for research on social cognition. In: Flavell JH, Ross L, editors. Social Cognitive Development: Frontiers and Possible Futures. Cambridge Univ Press; Cambridge, UK: 1981. pp. 43–66. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Richert R, Harris P. Dualism revisited: Body vs. mind vs. soul. J Cogn Cult. 2008;8:99–115. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Leeuwen N. Religious credence is not factual belief. Cognition. 2014;133:698–715. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2014.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Monroe AE, Malle BF. From uncaused will to conscious choice: The need to study, not speculate about people’s folk concept of free will. Rev Philos Psychol. 2010;1:211–224. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mori M. The uncanny valley. Energy. 1970;7:33–35. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goff PA, Eberhardt JL, Williams MJ, Jackson MC. Not yet human: Implicit knowledge, historical dehumanization, and contemporary consequences. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2008;94:292–306. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.94.2.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haslam N. Dehumanization: An integrative review. Pers Soc Psychol Rev. 2006;10:252–264. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr1003_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haslam N. Morality, mind, and humanness. Psychol Inq. 2012;23:172–174. [Google Scholar]