Abstract

Background and Objectives:

Endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage (EUS-BD), first reported as an alternative to percutaneous transhepatic BD in failed endoscopic retrograde cholangiography, is sometimes performed as reintervention for transpapillary stent dysfunction such as in patients with new onset gastric outlet obstruction, but direct conversion to EUS-BD can potentially have a risk of leakage of infected bile. The aim of this study is to evaluate the safety and efficacy of conversion to EUS-BD using a temporary endoscopic nasobiliary drainage (ENBD) tube placement as a reintervention for prior BD.

Patients and Methods:

Sixteen patients with prior BD for malignant biliary obstruction undergoing conversion to EUS-BD using a temporary ENBD tube placement were studied. Technical and clinical success rate and adverse events were evaluated.

Results:

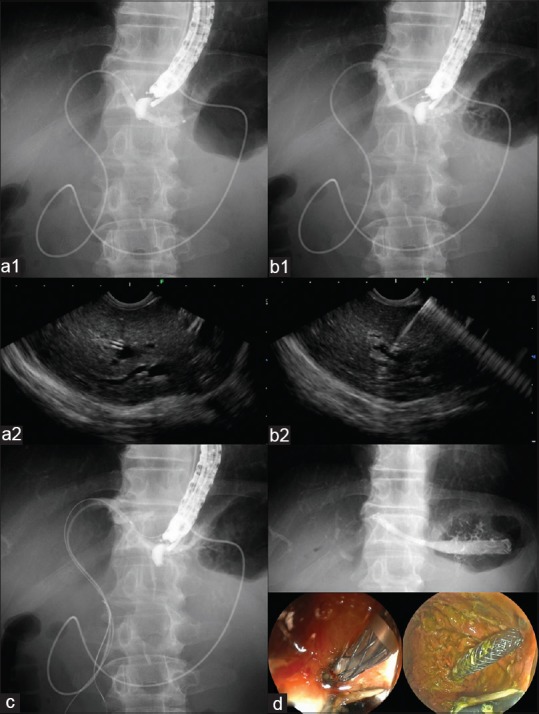

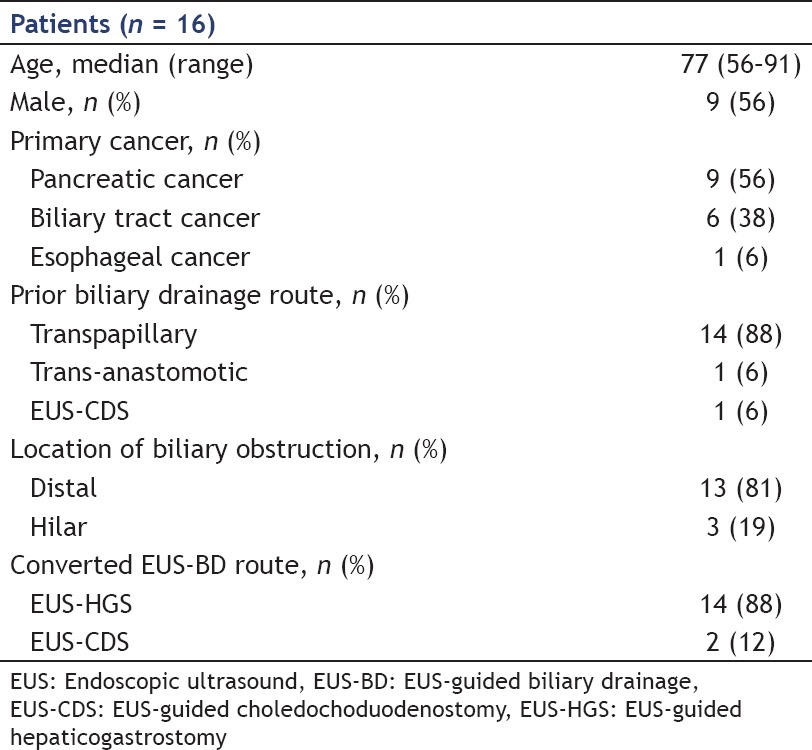

The major reason for conversion to EUS-BD was recurrent cholangitis due to duodenobiliary reflux (n = 13). In 14 patients with an indwelling covered metal or plastic stent, the stents were removed before temporary ENBD placement. After a median duration of 6 days, subsequent conversion to EUS-BD using a covered metal stent was performed, which was technically and clinically successful in all 16 patients (14 hepaticogastrostomy and 2 choledochoduodenostomy). Adverse events were observed in 3 patients (19%): one bleeding, one cholecystitis, and one cholangitis. No bile leak, peritonitis, or sepsis was observed.

Conclusions:

Conversion to EUS-BD using temporary ENBD tube placement in patients with prior BD was technically feasible and relatively safe without infectious complications related to bile leakage.

Keywords: Biliary drainage, covered metal stent, endoscopic ultrasound, malignant biliary obstruction

INTRODUCTION

Endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage (EUS-BD) has been increasingly reported as an alternative to percutaneous transhepatic BD (PTBD) in cases with failed endoscopic retrograde cholangiography (ERCP) for malignant biliary obstruction (MBO).[1,2] The reasons for EUS-BD can be failed deep biliary cannulation, altered gastrointestinal (GI) anatomy, or gastric outlet obstruction (GOO), but failed biliary cannulation is rare by an expert in the absence of anatomical reasons and GOO is the major reason for EUS-BD. GOO can adversely affect the outcomes of transpapillary biliary stenting even if ERCP is technically successful. We previously reported that both duodenal invasion[3] and an indwelling duodenal stent[4] are risk factors for dysfunction of transpapillary biliary stenting due to duodenobiliary reflux even if patients have no GOO symptoms. Thus, EUS-BD can be an alternative to repeated transpapillary stenting in those patients with recurrent stent dysfunction due to duodenobiliary reflux.[5] Conversion to EUS-BD is preferable in these cases because even though transpapillary stenting is technically possible, its stent patency can be short and because the ampulla would be soon inaccessible after the progression of GOO. Since GOO is often preceded by MBO,[6] EUS-BD is often performed as conversion from transpapillary stenting rather than as the initial BD in this setting. However, the technique of conversion to EUS-BD in prior BD has not been established. Direct conversion to EUS-BD in patients with prior BD can be potentially complicated by leakage of infected bile and severe peritonitis. Therefore, we tried to insert endoscopic nasobiliary drainage (ENBD) after removal of the indwelling biliary stent, followed by EUS-BD after resolution of cholangitis. Herein, we aimed to evaluate safety and efficacy of this conversion to EUS-BD technique utilizing temporary ENBD placement.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Patients

Consecutive patients with unresectable MBO who underwent conversion to EUS-BD utilizing temporary ENBD tube placement between August 2011 and November 2014 at the University of Tokyo Hospital and three affiliated hospitals were retrospectively studied. This study was approved by the local ethical committee.

Procedure

The decision to convert to EUS-BD was made after at least two episodes of cholangitis with and without stent occlusion due to duodenobiliary reflux. First, ERCP with an ENBD tube placement was performed as reinterventions for transpapillary stenting or EUS-BD. Prior biliary stents including a fully or partially covered metallic stent (CMS) was removed endoscopically if possible. Then, a 5-Fr or 7-Fr ENBD tube was placed in the left intrahepatic bile duct or upper common bile duct.

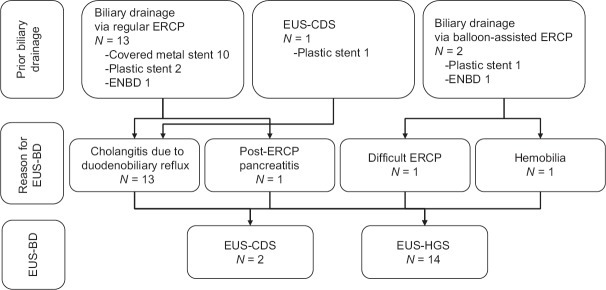

Second, EUS-BD, either hepaticogastrostomy (HGS) or choledochoduodenostomy (CDS), was performed as the second session after resolution of cholangitis [Figure 1] by one of three experienced endoscopists (YN, NY, and HI). All EUS procedures were performed using a linear echoendoscope (GF-UCT 240-AL5 or GF-UCT 260; Olympus Medical Systems, Tokyo, Japan, or EG-530 UT2; Fujifilm Corp., Tokyo, Japan), which was connected to a processor featuring color Doppler function (EU-ME1 or EU-ME2; Olympus Medical Systems, or SU-8000 or SU-1; Fujifilm Corp., Tokyo, Japan) under moderate sedation with intravenous diazepam (10–20 mg) and pethidine hydrochloride (35–70 mg).

Figure 1.

Conversion to endoscopic ultrasound-biliary drainage procedure. (a) Contrast injection through an endoscopic nasobiliary drainage tube. (b) Endoscopic ultrasound-guided puncture. (c) Guidewire insertion to the bile duct. (d) Endoscopic ultrasound-biliary drainage stent deployment

After EUS scope insertion, contrast was injected through an ENBD tube to inflate the bile duct and to guide the puncture site. Excessive contrast injection was not performed to avoid bacteremia or sepsis from the increased bile duct pressure. Visualization of the biliary system was then performed both on EUS and fluoroscopy. Then, the targeted bile duct was punctured with a 19-gauge FNA needle (Expect Flex, Boston Scientific, Natick Mass, or SonoTip Pro Control, MediGlobe, Rosenheim, Germany), flushed with contrast material, instead of a stylet. The puncture of the bile duct was confirmed by contrast injection on fluoroscopy or by aspiration of the bile if possible. Contrast was half-diluted to allow visualization of subsequent guidewire manipulation in the bile duct on fluoroscopy. Then, a 0.025 inch guidewire (VisiGlide, Olympus Medial, or Revowave, Piolax Medical, Tokyo, Japan) or a 0.035 inch hydrophilic guidewire (Radifocus, Terumo, Tokyo, Japan) was inserted deeply into the bile duct. Then, fistula dilation was performed using coaxial electric cautery (Cysto-gastro-set, ENDO-FLEX, Voerde, Germany), biliary bougie dilator (Soehendra biliary dilation catheter, Cook Medical, Bloomington, IN, USA), and/or balloon dilation (Hurricane Rx, Boston Scientific Japan, Tokyo, Japan). Then, a CMS was placed through the fistula and ENBD tube was removed. Prophylactic antibiotics were routinely administered for both ENBD tube placement and EUS-BD procedures.

Study outcomes

The primary outcome was technical success. Secondary outcomes were clinical success and procedure-related adverse events. Technical success was defined as placement of EUS-BD stent in an appropriate position. Clinical success was defined as resolution of obstructive jaundice and cholangitis if any. Procedure-related adverse events were defined according to the lexicon.[7]

RESULTS

Patients

Between August 2011 and November 2014, a total of 46 patients underwent EUS-BD using a CMS for MBO. Among them, ENBD placement was temporarily placed before conversion to EUS-BD in 16 patients. Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1 and Figure 2. The reason for conversion to EUS-BD was recurrent cholangitis due to duodenobiliary reflux in 13, altered GI anatomy in 1, hemobilia due to BD across the tumor in 1 and post-ERCP pancreatitis after transpapillary BD due to anomalous pancreaticobiliary junction in 1. In one patient with prior EUS-CDS, a temporary ENBD tube placement through CDS fistula and conversion to EUS-HGS were performed due to new onset GOO and recurrent cholangitis. Prior BD was CMS in 10, plastic stent (PS) in 2, ENBD in 1 for distal MBO (n = 13), and PS through an occluded uncovered metal stent in 2 and ENBD in 1 for hilar MBO (n = 3). Median time to cholangitis in transpapillary stenting was 42 days in patients with recurrent cholangitis due to duodenobiliary reflux.

Table 1.

Patients’ characteristics

Figure 2.

Prior biliary drainage, reasons for conversion to endoscopic ultrasound-biliary drainage procedure. EUS-BD: Endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage, EUS-CDS: Endoscopic ultrasound-guided choledochoduodenostomy, EUS-HGS: Endoscopic ultrasound-guided hepaticogastrostomy

Endoscopic nasobiliary drainage tube placement

All CMS and PS were endoscopically removed, followed by ENBD tube placement. Two patients received ENBD at the initial ERCP because decision of conversion to EUS-BD was made during ERCP. In one case with distal MBO, tight duodenal stricture at the ampulla was diagnosed at the initial ERCP and the patient was considered as unfit for transpapillary biliary stenting. In the other case with altered anatomy, the insertion of double balloon enteroscope was difficult and only a 5-Fr ENBD tube placement for hilar biliary obstruction was technically possible.

Conversion to endoscopic ultrasound-biliary drainage

In cases with concomitant cholangitis, EUS-BD was scheduled after resolution of cholangitis by ENBD tube placement, and the median interval from ENBD placement and EUS-BD was 6 (range, 1–10) days. No ENBD dislocation was observed before EUS-BD. The procedure (visualization and puncture of the bile duct, guidewire passage, fistula dilation, and stent placement) was technically successful in all 16 cases (100%): 14 HGS and 2 CDS. All patients underwent CMS placement: A modified GioBor stent (a partially CMS with 1 cm kept uncovered only at the proximal end, TaeWoong Medical Inc., Gimpo, Korea) in 11, a Supremo stent (TaeWoong Medical Inc., Gimpo, South Korea) in 3 and a covered WallFlex (Boston Scientific) in 2. Clinical success was obtained in 100% (16/16), too, and no further recurrent cholangitis was observed.

Adverse events were observed in 3 patients (19%): Moderate bleeding (n = 1), moderate cholecystitis (n = 1), and moderate cholangitis (n = 1). No bile leak, peritonitis, or sepsis was observed. The cause of cholangitis was due to obstruction of peripheral side branch of intrahepatic bile duct by the covering membrane of CMS.

DISCUSSION

In our retrospective analysis, conversion to EUS-BD using a temporary ENBD tube placement in patients with prior biliary stent placement for MBO was technically and clinically successful in all attempted cases. Temporary ENBD placement, rather than direct conversion to EUS-BD, can potentially prevent infectious complications such as bile peritonitis or sepsis in cases undergoing EUS-BD for recurrent biliary obstruction due to prior stent occlusion.

There are some advantages of EUS-BD over conventional transpapillary stenting, especially in patients with duodenobiliary reflux, which was the major reason for EUS-BD in our cohort. We reported an association of GOO with poor outcomes of transpapillary BD.[3,4] Khashab et al. reported comparable efficacy of EUS-guided rendezvous technique and transmural stent placement after failed ERCP.[8,9] However, in patients with an indwelling duodenal stent, EUS-BD was superior to transpapillary biliary stenting in terms of stent patency in our analysis,[5] probably due to decreased duodenal motility and increased duodenal pressure in these cases. The other advantage of EUS-BD is drainage without crossing the tumor or the orifice of pancreatic duct. BD across the hypervascular tumor can cause recurrent stent occlusion by hemobilia. Patients with high risk for post-ERCP pancreatitis such as patients with anomalous pancreaticobiliary junction in our cohort can potentially benefit from conversion to EUS-BD from transpapillary BD, too.

Bile leak with subsequent peritonitis is one of the major complications in EUS-BD.[10,11,12,13,14] In cases with prior biliary interventions, bile is infected or contaminated by microorganisms, and bacterial biofilm exists on an indwelling biliary stent.[15] Our conversion technique to EUS-BD consists of two parts: Removal of the indwelling stent and insertion of ENBD. The aim of removal of the indwelling CMS or PS is to reduce the amount of bacterial biofilm and sludge attached to the stents. In addition to improving cholangitis due to prior stent occlusion, ENBD tube can both facilitate EUS-BD procedure and work as a safety net. Although EUS-BD was successful in all cases in our cohort, the presence of ENBD can prevent severe bile leak and peritonitis even if EUS-BD fails. Park et al.[16] reported a small case series of EUS-HGS after failed ERCP for transpapillary biliary metal stent occlusion. They performed direct EUS-HGS, as opposed to our 2-step EUS-BD, without any complications such as bile leak or peritonitis, but the procedure was performed by a single endoscopist with EUS-BD expertise. In multicenter studies,[10,11,12,13,14] the incidence of adverse events in EUS-BD varies from 8% to 35% and bile leak and/or peritonitis was reported in 2.8–11.1%. In addition, the incidence of adverse events of the intrahepatic approach was as high as 30% in most of studies. The overall incidence of adverse events of 19% without any bile leak or peritonitis seemed to be relative low, given the high rate of EUS-HGS performed in our study cohort. The absence of bile leak or peritonitis might be attributable to the use of ENBD.

Although EUS-BD is increasingly reported, its learning curve is still unclear due to the limited number of cases and its training system will be an important issue to generalize this procedure without increasing complications. Recently, an ex vivo training system for interventional EUS[17] is reported, but our technique of temporary ENBD placement before EUS-BD might be useful for trainees to learn EUS-BD under supervisions of experienced endosonographers in the clinical practice.

The possible drawback of ENBD placement is shrinkage of the biliary system, which hinders EUS-guided puncture. However, contrast injection at the time of EUS-BD could redilate the biliary system in all cases. In addition, the combination of cholangiogram and EUS image helps endoscopists as a roadmap to determine the appropriate puncture site and needle angle, making subsequent guidewire passage and device insertion easier. The other technical aspect we should notice at the time of conversion to EUS-BD is the needle puncture of the bile duct. Due to the chronic inflammation from the prior BD, the bile duct wall gets thickened and hard and there is more resistance at the needle puncture compared with EUS-BD as the initial drainage. As we experience at PTBD, we must confirm the EUS image of the needle tip going through the bile duct wall as well as the aspiration of the bile through the needle if possible.

A retrospective design of this analysis without a comparative group is the major limitation of this study. Theoretically, the presence of ENBD can be a safety net but the success rate of EUS-BD in this cohort was 100%, and prevention of bile leak or peritonitis by ENBD placement cannot be confirmed when EUS-BD fails.

CONCLUSION

Conversion to EUS-BD using a temporary ENBD tube placement in patients with prior biliary stent placement was technically feasible and relatively safe without complications related to the leak of contaminated bile.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank Drs. Hiroshi Yagioka, Suguru Mizuno, Rie Uchino, Dai Akiyama, Tomotaka Saito, Kaoru Takagi, Ryunosuke Hakuta, Kazunaga Ishigaki, Kei Saito, Tsuyoshi Takeda for taking care of the patients.

REFERENCES

- 1.Park do H, Jeong SU, Lee BU, et al. Prospective evaluation of a treatment algorithm with enhanced guidewire manipulation protocol for EUS-guided biliary drainage after failed ERCP (with video) Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;78:91–101. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2013.01.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khashab MA, Valeshabad AK, Afghani E, et al. Acomparative evaluation of EUS-guided biliary drainage and percutaneous drainage in patients with distal malignant biliary obstruction and failed ERCP. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60:557–65. doi: 10.1007/s10620-014-3300-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hamada T, Isayama H, Nakai Y, et al. Duodenal invasion is a risk factor for the early dysfunction of biliary metal stents in unresectable pancreatic cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:548–55. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.04.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hamada T, Nakai Y, Isayama H, et al. Duodenal metal stent placement is a risk factor for biliary metal stent dysfunction: An analysis using a time-dependent covariate. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:1243–8. doi: 10.1007/s00464-012-2585-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hamada T, Isayama H, Nakai Y, et al. Transmural biliary drainage can be an alternative to transpapillary drainage in patients with an indwelling duodenal stent. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59:1931–8. doi: 10.1007/s10620-014-3062-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mutignani M, Tringali A, Shah SG, et al. Combined endoscopic stent insertion in malignant biliary and duodenal obstruction. Endoscopy. 2007;39:440–7. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-966327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cotton PB, Eisen GM, Aabakken L, et al. Alexicon for endoscopic adverse events: Report of an ASGE workshop. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:446–54. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khashab MA, Fujii LL, Baron TH, et al. EUS-guided biliary drainage for patients with malignant biliary obstruction with an indwelling duodenal stent (with videos) Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76:209–13. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.03.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khashab MA, Valeshabad AK, Modayil R, et al. EUS-guided biliary drainage by using a standardized approach for malignant biliary obstruction: Rendezvous versus direct transluminal techniques (with videos) Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;78:734–41. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2013.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vila JJ, Pérez-Miranda M, Vazquez-Sequeiros E, et al. Initial experience with EUS-guided cholangiopancreatography for biliary and pancreatic duct drainage: A Spanish national survey. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76:1133–41. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dhir V, Artifon EL, Gupta K, et al. Multicenter study on endoscopic ultrasound-guided expandable biliary metal stent placement: Choice of access route, direction of stent insertion, and drainage route. Dig Endosc. 2014;26:430–5. doi: 10.1111/den.12153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gupta K, Perez-Miranda M, Kahaleh M, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-assisted bile duct access and drainage: Multicenter, long-term analysis of approach, outcomes, and complications of a technique in evolution. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;48:80–7. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31828c6822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kawakubo K, Isayama H, Kato H, et al. Multicenter retrospective study of endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage for malignant biliary obstruction in Japan. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2014;21:328–34. doi: 10.1002/jhbp.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dhir V, Itoi T, Khashab MA, et al. Multicenter comparative evaluation of endoscopic placement of expandable metal stents for malignant distal common bile duct obstruction by ERCP or EUS-guided approach. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:913–23. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.09.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Berkel AM, van Marle J, Groen AK, et al. Mechanisms of biliary stent clogging: Confocal laser scanning and scanning electron microscopy. Endoscopy. 2005;37:729–34. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-870131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park DH, Song TJ, Eum J, et al. EUS-guided hepaticogastrostomy with a fully covered metal stent as the biliary diversion technique for an occluded biliary metal stent after a failed ERCP (with videos) Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:413–9. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dhir V, Itoi T, Fockens P, et al. Novel ex vivo model for hands-on teaching of and training in EUS-guided biliary drainage: Creation of “Mumbai EUS” stereolithography/3D printing bile duct prototype (with videos) Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:440–6. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]