Abstract

Aim:

This sudy aims to investigate the association between insomnia or excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) and risk of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD).

Methods:

We searched published studies indexed in MEDLINE and EMBASE database from inception to December 2015. Studies that reported odds ratios (ORs), risk ratios, hazard ratios or standardized incidence ratio with 95% confidence intervals (CI) comparing the risk of NAFLD among participants who had insomnia or EDS versus those without insomnia or EDS were included. Pooled ORs and 95% CI were calculated using a random-effect, generic inverse variance method of DerSimonian and Laird. Cochran's Q test and I2 statistic were used to determine the between-study heterogeneity.

Results:

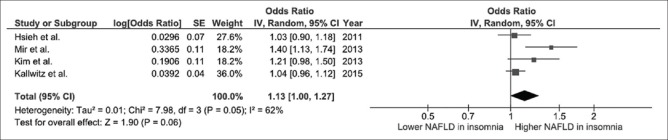

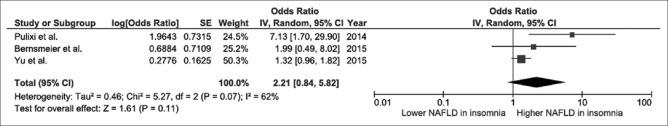

Our search strategy yielded 2117 potentially relevant articles (781 articles from MEDLINE and 1336 articles from EMBASE). After comprehensive review, seven studies (three cross-sectional studies and four case–control studies) were found to be eligible and were included in the meta-analysis. The risk of NAFLD in participants who had insomnia was significantly higher with the pooled OR of 1.13 (95% CI, 1.00–1.27). The statistical heterogeneity was moderate with an I2 of 62%. Elevated risk of NAFLD was also observed among participants with EDS even though the 95% CI was wider and did not reach statistical significance (pooled OR 2.21; 95% CI, 0.84–5.82). The statistical heterogeneity was moderate with an I2 of 62%.

Conclusions:

Our study demonstrated an increased risk of NAFLD among participants who had insomnia or EDS. Whether this association is causal needs further investigations.

KEY WORDS: Insomnia, meta-analysis, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, sleep quality

Introduction

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is one of the leading causes of chronic hepatitis and cirrhosis in Western countries as the prevalence of obesity has been steadily increasing over the past few decades.[1] Pathology of NAFLD ranges from simple steatosis to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) which can ultimately progress to cirrhosis. Metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance are the prime risk factors for NAFLD.[2,3] Other risk factors include hypertension, dyslipidemia, polycystic ovary syndrome, and hypothyroidism.[4,5]

Insomnia and excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS), defined as the inability to maintain wakefulness and alertness during the major waking episodes of the day with sleep occurring unintentionally almost daily for at least 3 months, are ones of the most common sleep-related disorders in adults.[6,7] Many studies have shown an association between both conditions and adverse health outcomes including the increased risk of psychiatric disorders, drug abuses, diabetes, cardiovascular disease as well as increased incidence of motor vehicle accident.[8,9,10,11,12]

Interestingly, insomnia and EDS could also increase the risk of NAFLD as observed in several epidemiologic studies.[13,14,15,16,17,18,19] Nonetheless, the results of those studies were inconsistent. To further investigate this possible association, we conducted this systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies reporting the risk of NAFLD among those who had insomnia or EDS.

Methods

Search strategy

Two investigators (K.W. and P.U.) independently searched published studies indexed in MEDLINE and EMBASE database from inception to December 2015 using the search strategy that included the terms for “sleep” and “NAFLD” as described in [Online Supplementary Data 1 available online (27.5KB, pdf) ]. No language limitation was applied. A manual search for additional studies using references of selected retrieved articles was also performed.

Search Strategy

Inclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) case–control, cross-sectional, or cohort studies evaluating the association between insomnia or EDS and NAFLD, (2) odds ratios (ORs), risk ratios, hazard ratios or standardized incidence ratio with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were provided, and (3) participants without insomnia or EDS were used as comparators in cohort study while participants without NAFLD were used as comparators in case–control and cross-sectional study.

Study eligibility was independently determined by the two investigators noted above. Differences in the determination of study eligibility were resolved by mutual consensus. The quality of each study was also independently evaluated by each investigator using Newcastle–Ottawa quality assessment scale.[20] This scale evaluated each study in three domains including the selection of the participants, the comparability between the groups and the ascertainment of the exposure for case–control study and the outcome of interest for cohort study. The modified Newcastle–Ottawa scale as described by Herzog et al. was used for cross-sectional study.[21]

Data extraction

A standardized data collection form was used to extract the following data from each study: Title of the study, name of the first author, year of study, year of publication, country of origin, number of participants, demographic data of the participants, methods used to identify and verify the insomnia, EDS and NAFLD, adjusted effect estimates with 95% CI and covariates that were adjusted in the multivariate analysis.

To ensure the accuracy, this data extraction process was independently performed by all investigators. Data discrepancy was resolved by referring to the original articles.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using Review Manager 5.3 Software from the Cochrane Collaboration (London, United Kingdom). Adjusted point estimates and standard errors from the individual study were combined using the generic inverse variance method of DerSimonian and Laird, which assigned the weight of each study based on its variance.[22] In light of the high likelihood of between-study variance because of different study designs and populations, we used a random-effect model rather than a fixed-effect model. Cochran's Q test and I2 statistic were used to determine the between-study heterogeneity. A value of I2 of 0%–25% represents insignificant heterogeneity, >25% but <50% represents low heterogeneity, >50% but <75% represents moderate heterogeneity, and >75% represents high heterogeneity.[23]

Results

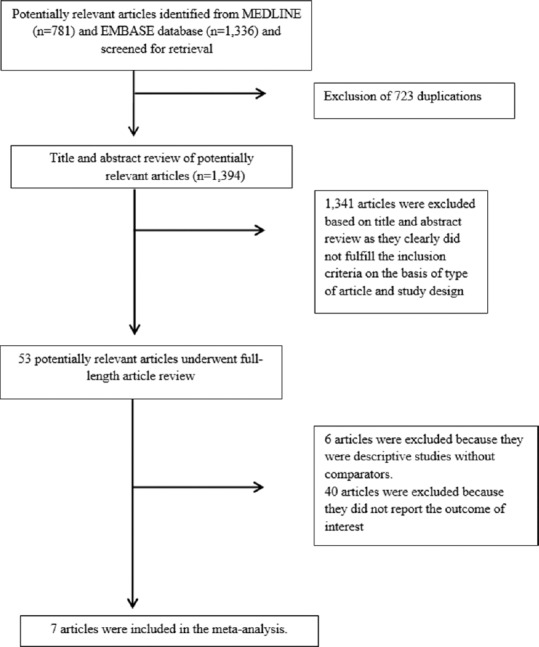

Our search strategy yielded 2117 potentially relevant articles (781 articles from MEDLINE and 1,336 articles from EMBASE). After the exclusion of 723 duplicated articles, 1394 of them underwent title and abstract review. A total of 1341 articles were excluded at this stage since they were case report, letter to editor, review article or interventional study, leaving 53 articles for a full-length article review. Forty of them were excluded since they did not report the outcome of interest while six articles were excluded since they were descriptive studies without comparators. Therefore, seven studies (three cross-sectional studies and four case–control studies) met our eligibility criteria and were included in the meta-analysis.[13,14,15,16,17,18,19] Figure 1 outlines the literature review and study selection process. The characteristics and quality assessment of the included studies of insomnia and EDS are described respectively in Tables 1 and 2. PRISMA (Preferred reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis) is provided as [Online Supplementary Data 2 available online (84.5KB, pdf) ]. It should be noted that the inter-rater agreement for the quality assessment was high with the kappa statistics of 0.75.

Figure 1.

Literature review process

Table 1.

Main characteristics of the studies included in this meta-analysis of the association between insomnia or poor sleep quality and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

| Hsieh et al.[14] | Mir et al.[17] | Kim et al.[16] | Kallwitz et al.[15] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Japan | United States | South Korea | United States |

| Study design | Cross-sectional study | Case-control study | Cross-sectional study | Case-control study |

| Year | 2011 | 2013 | 2013 | 2015 |

| Recruitment of participants | Participants were recruited from Health Management Clinic of the study hospital | Cases with NAFLD were identified from NHANES database between 2005 and 2010. Controls were sex- and age-matched individuals who were randomly selected from the same database. Controls must never have a prior history of NAFLD | Participants were employees of one large company in Korea, and their spouses. The study was conducted during a routine annual health examination for employees of the company | Cases with NAFLD were identified from the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latino database. Controls were the rest of the individuals in the database without NAFLD |

| Number of participants | 8157 | 10,541 (1572 NAFLD; 8969 controls) | 45,293 | 12,133 (2318 NAFLD; 9815 controls) |

| Definition of sleep problems | Poor sleep quality, complaints of difficulty of falling asleep or awakening easily | Insomnia defined by a positive response to the questions “Have you ever been told by a doctor that you have sleep disorder?” and “Do you have difficulty falling or staying asleep?” | Poor sleep quality defined as>5 points of Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index | Sleep disturbance |

| Sleep problems measurement | Self-administered questionnaire | Interviewer-administered questionnaire | Self-administered Pittsburgh sleep quality index questionnaire | Self-administered questionnaire |

| Definition of NAFLD | A diffuse hyperechoic echo texture, bright liver compared to kidneys, vascular blurring and deep attenuation in the absence of any known causes of chronic liver disease | Elevation of serum aminotransferases (men, AST >37 U/L or ALT >40 U/L; women, AST or ALT >31 U/L) in the absence of any known causes of chronic liver disease | A diffuse hyperechoic echo texture, bright liver compared to kidneys, vascular blurring and deep attenuation in the absence of any known causes of chronic liver disease | Elevation of serum aminotransferases (men, AST >37 U/L or ALT >40 U/L; women, AST or ALT >31 U/L) in the absence of any known causes of chronic liver disease |

| NAFLD ascertainment | Liver ultrasonography | Review of clinical and laboratory information from NHANES database | Liver ultrasonography | Review of clinical and laboratory information from Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latino database |

| Cases (n) | 300 | 25 | 1694 | 2318 |

| Controls (n) | 397 | 71 | 1873 | 9815 |

| Confounder adjustment | Metabolic and behavioral risk factors | Age, gender, ethnicity | Age, alcohol intake, smoking, physical activity, systolic blood pressure, educational level, marital status, presence of job, sleep apnea, loud snoring | Age, sex, ethnic, waist circumference, triglycerides, HDL, blood pressure, fasting glucose, acculturation, healthcare use, total carbohydrates, physical activity, education, income |

| Quality assessment (Newcastle-Ottawa scale) | Selection: 2 Comparability: 1 Outcome: 2 |

Selection: 3 Comparability: 1 Outcome: 2 |

Selection: 4 Comparability: 2 Outcome: 3 |

Selection: 4 Comparability: 2 Outcome: 3 |

NHANES: National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys, BMI: Body mass index, HDL: High-density lipoprotein, NAFLD: Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, HDL: High-density lipoprotein, AST: Aspartate transaminase, ALT: Alanine transaminase

Table 2.

Main characteristics of the studies included in this meta-analysis of the association between excessive daytime sleepiness and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

| Pulixi et al.[18] | Yu et al.[19] | Bernsmeier et al.[13] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Italy | South Korea | Switzerland |

| Study design | Case-control study | Cross-sectional study | Case-control study |

| Year | 2014 | 2015 | 2015 |

| Recruitment of participants | Cases were consecutively recruited from metabolic liver disease clinic of the study hospital from 2009 to 2013. Controls were sex- and age-matched individuals randomly selected from the same area. Controls must never have a prior history of NAFLD |

Participants were recruited from the cohort of the Korean Genome and Epidemiology Study, from March 2009 to February 2011 | Cases were recruited from the basel NAFLD cohort study. All cases had biopsy-confirmed NAFLD. Controls were sex- and age-matched individuals randomly selected from the same area. Controls must never have a prior history of NAFLD |

| Number of participants | 239 (159 NAFLD; 80 controls) | 335 | 88 (46 NAFLD; 22 controls) |

| Definition of Excessive daytime sleepiness | ≥10 points of Sleepiness Epworth Scale | Excessive daytime sleepiness: ≥11 points of Sleepiness Epworth Scale | Excessive daytime sleepiness: ≥11 points of Sleepiness Epworth Scale |

| Excessive daytime sleepiness measurement | Self-administered Sleepiness Epworth Scale questionnaire | Interviewer-administered Sleepiness Epworth Scale questionnaire | Self-administered Sleepiness Epworth Scale questionnaire |

| Definition of NAFLD | Liver histology showed hepatic steatosis in the absence of any known causes of chronic liver disease | Liver attenuation index value <5 Hounsfield units without evidence of other known causes of chronic liver disease | Liver histology showed hepatic steatosis in the absence of any known causes of chronic liver disease |

| NAFLD ascertainment | Liver biopsy | Liver MRI | Liver biopsy |

| Confounder adjustment | None | Age, sex, exercise, alcohol, smoking, diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and BMI | None |

| Quality assessment (Newcastle-Ottawa scale) | Selection: 2 Comparability: 0 Outcome: 3 |

Selection: 3 Comparability: 2 Outcome: 3 |

Selection: 2 Comparability: 0 Outcome: 3 |

BMI: Body mass index, ALT: Alanine aminotransferase, HOMA-IR: Homeostasis model assessment for insulin resistance, WHR: Waist-to-hip ratio, NAFLD: Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging

PRISMA 2009 Checklist

We found a significantly increased risk of NAFLD among participants with insomnia with the pooled OR of 1.13 (95% CI, 1.00–1.27), as shown in Figure 2. The statistical heterogeneity was moderate with an I2 of 62%. We also found an increased risk of NAFLD among participants with EDS with the pooled OR of 2.21 even though the 95% CI was wider and did not reach statistical significance (95% CI, 0.84–5.82), as shown in Figure 3. The statistical heterogeneity was moderate with an I2 of 62%.

Figure 2.

Forest plot of all included studies of the association between insomnia or poor sleep quality and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

Figure 3.

Forest plot of all included studies of the association between excessive daytime sleepiness and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

Evaluation for publication bias

We did not perform an evaluation for publication bias as the number of studies included in the meta-analyses was too small.

Discussion

The association between insomnia/EDS and risk of NAFLD has been observed in epidemiologic studies even though the results were inconsistent. This meta-analysis was conducted with the aims to summarize all available data. We found a small but significantly increased risk of NAFLD among participants who had insomnia compared to those with good sleeping. We also found an increased risk of NAFLD among participants with EDS even though the result did not reach statistical significance due to a smaller number of included studies. The mechanism behind this association remains unknown, but there are some potential explanations.

First, it has been shown that several inflammatory cytokines essential for the pathogenesis of NAFLD, such as interleukin-6 and tumor necrotic factor alpha, are inducible by lack of sleep.[24,25,26] These cytokines can increase adipocyte lipolysis, resulting in hepatic overflow of free fatty acid, and impaired insulin signaling.[27] Second, insomnia may increase appetite as a result of hormonal changes such as increased ghrelin level and decreased leptin level, leading to more calories intake and obesity, the major risk factor for NAFLD.[28,29] Third, insomnia and EDS are associated with fatigue. Therefore, those with insomnia or EDS might be less physically active and are at higher risk of obesity and metabolic syndrome.[13]

Although the quality of included studies was high as reflected by the high Newcastle–Ottawa scores, we acknowledged that there were some limitations.

First, data on insomnia and EDS may be less reliable as most included studies used self-administered questionnaires. Second, the statistical heterogeneity was moderate in this meta-analysis. We suspect that the differences in study designs, populations, and methods used to verify NAFLD were responsible for this inter-study variability. Third, about half of the included studies were cross-sectional studies that would not allow us to establish a temporal relationship between NAFLD and sleep disturbance. It is possible that NAFLD might have negative effects on physiology of sleep and the insomnia/EDS are a consequence of NAFLD, not risk factors for NAFLD. In fact, this study is a meta-analysis of observational studies that, at best, could only demonstrate an association but cannot prove causality as unknown confounders could play a certain role behind the association.

In summary, an increased risk of NAFLD was observed among participants who had insomnia or EDS. Whether this association is causal remains unclear. Further investigations are required to establish the role of sleep for the prevention of NAFLD.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Data

Online Supplementary Data 1 (27.5KB, pdf) : Search strategy

Online Supplementary Data 2 (84.5KB, pdf) : PRISMA checklist

References

- 1.Vernon G, Baranova A, Younossi ZM. Systematic review: The epidemiology and natural history of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in adults. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34:274–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04724.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saponaro C, Gaggini M, Gastaldelli A. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and type 2 diabetes: Common pathophysiologic mechanisms. Curr Diab Rep. 2015;15:607. doi: 10.1007/s11892-015-0607-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wijarnpreecha K, Thongprayoon C, Edmonds PJ, Cheungpasitporn W. Associations of sugar- and artificially sweetened soda with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. QJM. 2016;109:461–6. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcv172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Byrne CD, Targher G. NAFLD: A multisystem disease. J Hepatol. 2015;62(1 Suppl):S47–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chalasani N, Younossi Z, Lavine JE, Diehl AM, Brunt EM, Cusi K, et al. The diagnosis and management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: Practice guideline by the American Gastroenterological Association, American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, and American College of Gastroenterology. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:1592–609. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kiejna A, Wojtyniak B, Rymaszewska J, Stokwiszewski J. Prevalence of insomnia in Poland-results of the National Health Interview Survey. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2003;15:68–73. doi: 10.1034/j.1601-5215.2003.00011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kronholm E, Partonen T, Härmä M, Hublin C, Lallukka T, Peltonen M, et al. Prevalence of insomnia-related symptoms continues to increase in the Finnish working-age population. J Sleep Res. 2016;25:454–7. doi: 10.1111/jsr.12398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bonnet MH, Arand DL. Heart rate variability in insomniacs and matched normal sleepers. Psychosom Med. 1998;60:610–5. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199809000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Breslau N, Roth T, Rosenthal L, Andreski P. Sleep disturbance and psychiatric disorders: A longitudinal epidemiological study of young adults. Biol Psychiatry. 1996;39:411–8. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(95)00188-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fernandez-Mendoza J, Vgontzas AN, Liao D, Shaffer ML, Vela-Bueno A, Basta M, et al. Insomnia with objective short sleep duration and incident hypertension: The Penn State Cohort. Hypertension. 2012;60:929–35. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.112.193268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vgontzas AN, Liao D, Pejovic S, Calhoun S, Karataraki M, Bixler EO. Insomnia with objective short sleep duration is associated with type 2 diabetes: A population-based study. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1980–5. doi: 10.2337/dc09-0284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Young TB. Epidemiology of daytime sleepiness: Definitions, symptomatology, and prevalence. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(Suppl 16):12–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bernsmeier C, Weisskopf DM, Pflueger MO, Mosimann J, Campana B, Terracciano L, et al. Sleep disruption and daytime sleepiness correlating with disease severity and insulin resistance in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A comparison with healthy controls. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0143293. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hsieh SD, Muto T, Murase T, Tsuji H, Arase Y. Association of short sleep duration with obesity, diabetes, fatty liver and behavioral factors in Japanese men. Intern Med. 2011;50:2499–502. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.50.5844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kallwitz ER, Daviglus ML, Allison MA, Emory KT, Zhao L, Kuniholm MH, et al. Prevalence of suspected nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in Hispanic/Latino individuals differs by heritage. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:569–76. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.08.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim CW, Yun KE, Jung HS, Chang Y, Choi ES, Kwon MJ, et al. Sleep duration and quality in relation to non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in middle-aged workers and their spouses. J Hepatol. 2013;59:351–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mir HM, Stepanova M, Afendy H, Cable R, Younossi ZM. Association of Sleep Disorders with Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD): A population-based study. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2013;3:181–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jceh.2013.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pulixi EA, Tobaldini E, Battezzati PM, D’Ingianna P, Borroni V, Fracanzani AL, et al. Risk of obstructive sleep apnea with daytime sleepiness is associated with liver damage in non-morbidly obese patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. PLoS One. 2014;9:e96349. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu JH, Ahn JH, Yoo HJ, Seo JA, Kim SG, Choi KM, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea with excessive daytime sleepiness is associated with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease regardless of visceral fat. Korean J Intern Med. 2015;30:846–55. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2015.30.6.846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25:603–5. doi: 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Herzog R, Álvarez-Pasquin MJ, Díaz C, Del Barrio JL, Estrada JM, Gil Á. Are healthcare workers’ intentions to vaccinate related to their knowledge, beliefs and attitudes? A systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:154. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–88. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–60. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jarrar MH, Baranova A, Collantes R, Ranard B, Stepanova M, Bennett C, et al. Adipokines and cytokines in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:412–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Prather AA, Marsland AL, Hall M, Neumann SA, Muldoon MF, Manuck SB. Normative variation in self-reported sleep quality and sleep debt is associated with stimulated pro-inflammatory cytokine production. Biol Psychol. 2009;82:12–7. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2009.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wieckowska A, Papouchado BG, Li Z, Lopez R, Zein NN, Feldstein AE. Increased hepatic and circulating interleukin-6 levels in human nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:1372–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01774.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Langin D, Arner P. Importance of TNFalpha and neutral lipases in human adipose tissue lipolysis. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2006;17:314–20. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spiegel K, Leproult R, L’hermite-Balériaux M, Copinschi G, Penev PD, Van Cauter E. Leptin levels are dependent on sleep duration: Relationships with sympathovagal balance, carbohydrate regulation, cortisol, and thyrotropin. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:5762–71. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spiegel K, Tasali E, Leproult R, Scherberg N, Van Cauter E. Twenty-four-hour profiles of acylated and total ghrelin: Relationship with glucose levels and impact of time of day and sleep. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:486–93. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Search Strategy

PRISMA 2009 Checklist