Abstract

Iodotyrosine deiodinase (IYD) is unusual for its reliance on flavin and ability to promote reductive dehalogenation under aerobic conditions. As implied by the name, this enzyme was first discovered to catalyze iodide elimination from iodotyrosine for recycling iodide during synthesis of tetra- and triiodothyronine collectively known as thyroid hormone. However, IYD likely supports many more functions and has been shown to debrominate and dechlorinate bromo- and chlorotyrosines. A specificity for halotyrosines versus halophenols is well preserved from humans to bacteria. In all examples to date, the substrate zwitterion establishes polar contacts with both the protein and the isoalloxazine ring of flavin. Mechanistic data suggest dehalogenation is catalyzed by sequential one electron transfer steps from reduced flavin to substrate despite the initial expectations for a single two electron transfer mechanism. A purported flavin semiquinone intermediate is stabilized by hydrogen bonding between its N5 position and the side chain of a Thr. Mutation of this residue to Ala suppresses dehalogenation and enhances a nitroreductase activity that is reminiscent of other enzymes within the same structural superfamily.

Keywords: Flavin, dehalogenase, thyroid, iodide salvage, reductive dehalogenation

Graphical abstract

I. Introduction to Iodotyrosine Deiodinase

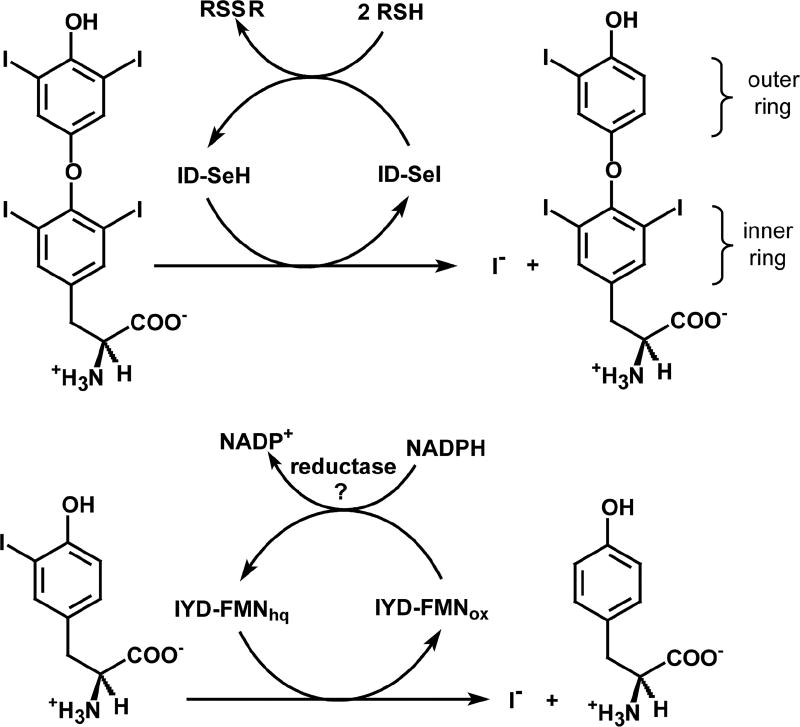

Halogenation is a common process in industry and nature and yet is rarely appreciated as a normal and even necessary event in mammals. Those who suffer from thyroid disease are most likely to be cognizant of the requirement for iodide and its incorporation into the hormones, 3,3',5,5'-tetraiodothyronine (T4) and 3,3',5-triiodothyronine (T3) that are produced in the thyroid. These hormones regulate a number of functions in our body ranging from the basal rate of metabolism to neurodevelopment [1, 2]. T4 is generally considered a prohormone of the more active T3 and consequently deiodination of the outer ring of T4 to form T3 stimulates thyroid-responsive activities (Scheme 1) [3, 4]. Alternative deiodination of the inner ring produces 3,3',5'-triiodothyronine (rT3), a biologically inactive isomer. Further deiodination of T3 and rT3 continues the metabolic degradation of thyroid hormone. These processes are differentially promoted by three isoforms of iodothyronine deiodinase (ID) but all derive from the thioredoxin structural superfamily and all contain an active site selenocysteine [3]. Research interest in these enzymes has been intense [3, 4] and inspired most recently by publication of the first crystal structure of ID [5, 6].

Scheme 1.

Two different types of enzymes promote the unusual process of reductive

Another enzyme promoting an analogous reductive deiodination has received considerably less attention even though its physiological importance was recognized over 60 years ago [7, 8]. This enzyme, entitled iodotyrosine deiodinase (IYD), salvages iodide from mono- and diiodotyrosine (I-Tyr and I2-Tyr, respectively) that are generated in large excess during thyroid hormone biosynthesis (Scheme 1) [9]. Iodide salvage was first suggested as the biological function of IYD after its catalytic activity was detected in thyroid tissue [8] and later supported by the inability of thyroid tissues from some patients with congenital hypothyroidism to catalyze such a deiodination [10, 11]. More recently, specific mutations of IYD have been identified in patients with abnormal iodide metabolism and congenital hypothyroidism [12, 13].

Enzymological studies were initially stymied by difficulties in isolating and purifying IYD. Early studies located IYD in the microsomal fraction of thyroid cells and identified NADPH as the source of reducing equivalents [14, 15]. Further isolation of the membrane-bound IYD proved to be very challenging and required another 20 years before the first protocol for preparing homogenous enzyme was published [16]. This heroic effort yielded only 1 mg of IYD from 1 kg of thyroid tissue but was sufficient to identify IYD as a FMN-dependent enzyme. IYD purification suffered from the additional complication of losing its responsiveness to NADPH after extraction from microsomes [17]. This was best explained by the existence of an independent reductase necessary to shuttle reducing equivalents from NADPH to IYD. The nature and identity of the purported reductase remain unknown and may be substituted by strong reducing agents such as clostridial ferredoxin, methyl viologen and, most commonly, dithionite to drive IYD catalysis IYD [18].

Characterization of IYD was also limited by the inherent difficulties of handling this membrane-bound protein [19–21]. Soon after the gene for IYD was identified [22], the cDNA of porcine IYD was successfully expressed in HEK293 cells [23]. The gene assignment was also confirmed by sequencing peptide fragments of IYD purified from porcine thyroid [24]. Sequence information on IYD provided a range of new topics to explore [25]. First, IYD was identified as a member of the nitro-FMN reductase superfamily with no structural or mechanistic relationship to ID. Second, a short membrane anchor was detected at the N-terminus of IYD [24]. Truncation of this anchor generated a well-behaved and soluble form of mouse IYD from heterologous expression in HEK293 cells [26]. Later expression in insect cells (Sf9) afforded the first large scale isolation of IYD and recent advances now support routine expression of IYD from many organisms in Escherichia coli [27, 28]. Ready access to IYD has inspired a range of new investigations that are summarized in this review. Results on distribution, structure, function and catalytic mechanism of IYD have all defied our expectations and continue to propel our laboratory to pursue the next fascinating result on this system.

II. Signature Residues within the Active Site of IYD Reveal an Unanticipated Distribution in Nature

Signature sequences of IYD

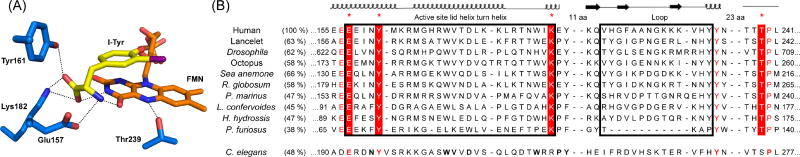

The sequence elements unique to IYD became immediately clear once the first co-crystal structure of I-Tyr and mouse IYD was determined [29]. The zwitterionic portion of I-Tyr acts as a template to stabilize closure of an active site lid by chelating both the flavin and side chains of three residues (Glu, Tyr and Lys) (Figure 1). Additionally, a side chain of a Thr provides hydrogen bonding to the N5 of the flavin. The sequence database of the nitro-FMN reductase superfamily was queried for these residues with the hope of identifying the origins of IYD by phylogenetic analysis [28]. IYD was expected throughout the phylum Chordata that encompasses reptiles, fish and mammals since its members all produce thyroid hormones for regulatory pathways. Surprisingly, the same signature amino acids were apparent in genes of many other organisms (Figure 1). By default many of these enzymes had been annotated as nitroreductases since the general

Figure 1.

Conservation of key residues coordinating substrate, protein and FMN. (A) Active site residues illustrated by human IYD (PDB 4TTC) form polar interactions over distances ranging from architecture of this family is easily detected.

IYD homologs from a set of representative organisms across many phyla were expressed and checked for IYD activity to confirm the diagnostic utility of the active site residues noted above [28]. The proteins from Chordata (zebrafish and lancelet) did indeed support catalytic deiodination of I2-Tyr. Remarkably, the putative IYD from insects (honey bee), crustaceans (water flea), hydrozoa (hydra) and anthozoa (sea anemone) all promote the same deiodination reaction as well when reduced by dithionite [28]. The physiological relevance of such a reaction is suggested by the similarity of the kcat/Km values that vary over only a single order of magnitude with an average of 2 × 104 M−1 s−1. If these efficiencies satisfy the needs of Chordata then they should likely satisfy the needs of the additional organisms that were not known to require iodide salvage. More recently, human and Drosophila IYD have also been expressed heterologously and shown to catalyze the same deiodination with kcat/Km values that again fall within the same range (1.6 × 104 M−1s−1 and 1.0 × 104 M−1s−1) [31, 32]. Even certain eubacteria (Haliscomenobacter hydrossis) [28] and archaea (Pyrococcus furiosus) [33] contain an active IYD although its presence is far from universal in these two branches of life [34].

The signature residues remain constant in the active site despite the low identity (47%) of sequence shared by human and H. hydrossis IYD (Figure 1). The identities are even lower between either human and P. furiosus IYD (38%) or H. hydrossis and P. furiosus IYD (36%) and only slightly larger than that shared across functional branches of the nitro-FMN reductase superfamily as illustrated by the 25% identity between mouse IYD and Thermus thermophilus NADH oxidase [24]. The equivalently large drifts in IYD sequence between the three branches of life suggest that this enzyme may have appeared very early in evolution during which iodinated compounds might have been common [35]. Contrary to our initial expectations, IYD did not emerge with the advent of thyroid hormones but instead was co-opted from another function to salvage iodide from I-Tyr and I2-Tyr for thyroxine biosynthesis in Chordata. Recent additions to the IYD family are included in Figure 1 and illustrate the variable presence of IYD in some branches of life. For example, octopus is the only example to date of IYD in the phylum Mollusca. Similarly, IYD from Rhizoclosmatium globosum is the first representative from Fungi and only a limited number have been discovered in cyanobacteria such as Lyngbya confervoides or unicellular protists such as Perkinsus marinus.

An Ala residue that donates a hydrogen bond from its backbone N-H to the phenolic oxygen of substrate was not conserved as originally suggested in an earlier analysis [28]. IYD from Archaea retains the standard deiodinase activity but, in some examples, contains a Met in place of this Ala [33]. The relative importance of the remaining signature residues was tested by site-directed mutagenesis. When the active site Thr that provides a hydrogen bond to the N5 position of flavin was mutated to an Ala, the kcat/Km value decreased by 15-fold although a greater effect was expected as discussed below [36]. The residues, Tyr, Glu and Lys that coordinate to the zwitterion of substrate were mutated respectively to Phe, Gln and Gln [32]. The Tyr to Phe mutation lowered the kcat/Km value by less than 4-fold whereas mutation of either the Lys or the Glu caused a 50-fold and greater than 800-fold decrease in kcat/Km for I2-Tyr deiodination, respectively. Thus, the Tyr residue appears least essential to catalysis and recently was found to be substituted by His in putative IYD from Hyperthermus butylicus and Staphylothermus marinus [32]. In contrast, few exceptions to the conserved Glu and Lys have yet been discovered and suggest that the putative IYDs generally retain specificity for tyrosine derivatives. The distribution of amino acid sequences in a helix-turn-helix of the active site lid reiterates the dominance of the Glu, Tyr and Lys as well as a few other notable residues such as Trp, Leu and Thr (Figure 2). These additional three residues form the top of the substrate binding pocket with respect to the I-Tyr and FMN orientation illustrated in Figure 1A.

Figure 2.

Sequence distribution in the active site lid of IYD responsible for substrate recognition.

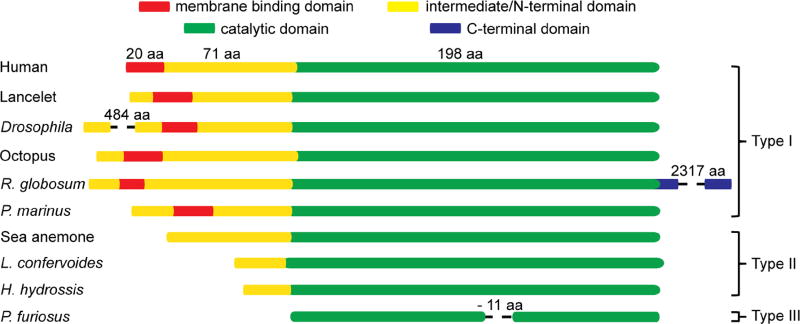

Structural domains of IYD

The primary sequence of mammalian IYDs can be divided into three domains: an N-terminal membrane binding domain that is highly lipophilic, an intermediate domain that is neither homologous to known structural motifs nor characterized by X-ray diffraction to date, and a C-terminal catalytic domain that folds into the common structure of the nitro-FMN reductase superfamily (Figure 3) [24]. IYD was the first member of this superfamily to be identified in mammals but representatives of this superfamily are widespread in eubacteria and promote a variety of reactions including nitro-reduction [39], 5,6-dimethylbenzimidazole biosynthesis [40] and flavin reduction [41]. The N-terminal domains of IYD are quite variable and include a membrane spanning domain as predicted by TMHMM (version 2.0 [42]) for IYD from human, mouse, zebrafish, Drosophila and hydra (Type I). In contrast, IYD from daphnia, sea anemone, and H. hydrossis have truncated N-terminal segments that appear to lack a membrane binding region (Type II). A few examples such as IYD from Drosophila and R. globosum have long extensions on either their N- or C-termini. The functional relevance of these extensions are not yet known and their sequences have no precedence in the databases to date. The minimal length of IYD is defined by sequences in thermophilic eubacteria and archaea (Type III). For example, IYD from P. furiosus contains only 187 amino acids and lacks the loop regions that associates with the active site lid (Figures 1 and 3). Preliminary data indicate this enzyme promotes the standard deiodination of I2-Tyr and thus the intermediate domain and loop are not required for catalysis [33]. Truncation of the loop region may help to improve the thermal stability of IYD since IYD from P. furiosus remains active at 60 °C in contrast to IYD from the mesophile H. hydrossis [33].

Figure 3.

Sequence domains of IYD.

The widespread distribution of IYD

To date, putative homologs of IYD containing the signature residues are present in all three branches of life. IYD of type I is restricted to eukaryotes and type III is restricted to eubacteria and archaea but type II is variably present in all three branches. However, IYD is not universally represented in all branches of life. For example, IYD is notably missing from Rhodophyta (red algae) and Viridiplantae (green algae and land plants) even though there are a few examples of IYD in photosynthetic cyanobacteria. IYD was originally thought to be absent from fungi [28]. A recent release of sequence information on the fungi R. globosum now defies expectations by carrying a gene containing a region that is homologous to IYD. Interestingly, this putatutive type I homolog represents only the N-terminal domain of a ~300 kDa mega-protein [43]. IYD homologs are already widely distributed but more surprises can be expected as additional genomic sequences become available.

III. The Structural Basis for IYD Catalysis and Selectivity

IYD shares a core structure common to the nitro-FMN reductase superfamily

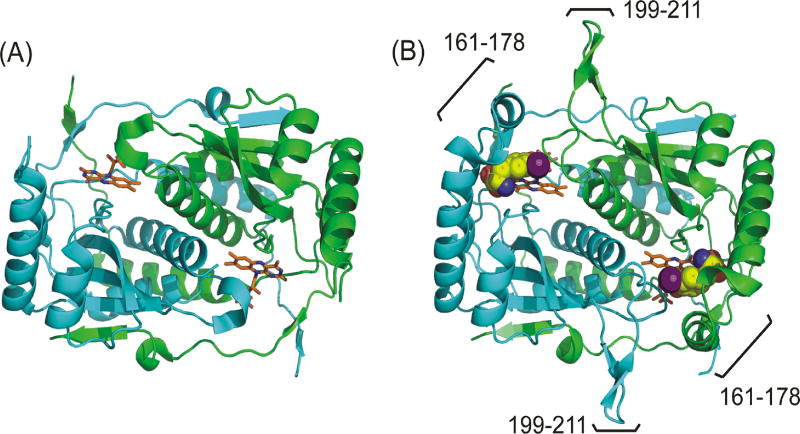

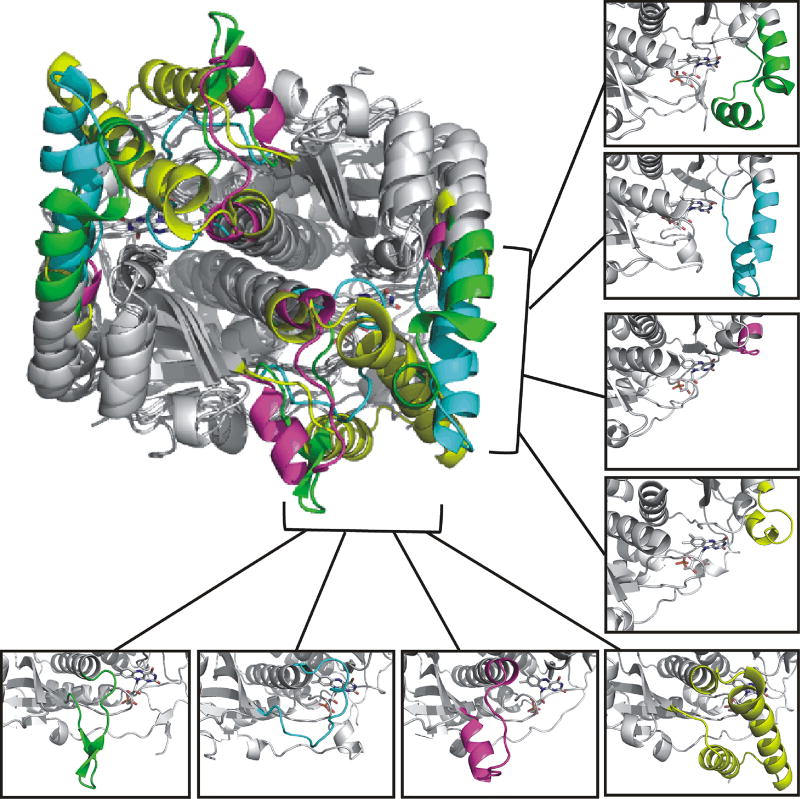

Murine IYD lacking its N-terminal membrane anchor was the first representative to be isolated in significant quantities and also the first to provide a set of crystal structures [29]. As heterologous expression of IYD became routine, access to IYD from many organisms became possible [28]. The crystal structures of human and H. hydrossis IYD in the presence and absence of active site ligands have since been determined (Figure 4) [31, 44]. These latter structures in the absence of ligand are nearly superimposable with an RMSD of 0.77 Å for 321 Cα atoms even though they share only 46% identity and originate from two distinct branches of life [44]. All structures form a homodimer with an α-β fold and domain swaps at the N- and C-termini that are standard for the nitro-FMN superfamily [34]. FMN is bound at the dimer interface and both subunits contribute to each of the two identical active sites. To date, all data suggest that these active sites act independently and do not influence each other during ligand binding and substrate catalysis. In the absence of I-Tyr or I2-Tyr, the helix turn helix of the active site lid and a loop domain (Figures 1 and 2) in mouse and human IYD do not form a stable structure as evident by a lack of their X-ray diffraction (Figure 4) [29, 31]. In contrast, the loop domain is detected in the presence and absence of I-Tyr for H. hydrossis IYD [44].

Figure 4.

Crystal structures of human IYD containing FMNox in the absence and presence of I-Tyr. The green and cyan ribbons represent the two identical polypeptides that assemble into an active dimer. (A) In the absence of substrate, the active site lid (helix turn helix, residues 161–178) and loop (199–211) do not adopt a single stable conformation (PDB 4TTB) [31]. (B) In the presence of I-Tyr, the lid and loop form a stable and detectable structure that surrounds I-Tyr and collapses over the active site (PDB 4TTC) [31]. Carbon atoms of FMN are colored orange and carbons in the I-Tyr are colored yellow (and shown as spheres).

Co-crystallization of IYD with its substrate is possible since the resting enzyme contains oxidized flavin (FMNox) and thus unable to process the bound substrate. Accordingly, these structures represent only models of how IYD and substrate may associate during catalysis but still they offer considerable information on the origins of substrate selectivity and enzyme activation. By stimulating closure of the active site lid, I-Tyr is sequestered adjacent to FMN and helps to modulate its properties for dehalogenation (see below). The active site region in general determines the functional specificity of each branch within the the nitro-FMN reductase superfamily and, not surprisingly, this region contains the greatest diversity in sequence and conformation as evident from an overlay of structures determined for human IYD and representatives of bacterial flavin reductase (FRP), nitroreductase (NfsB) and flavin destructase (BluB) (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Structural diversity in the nitro-FMN superfamily is greatest in the active site domain. The α-β dimeric core regions of IYD (PDB 4TTC) [31], flavin reductase (FRP, PDB 2BKJ [41]), nitroreductase (NfsB, PDB 1YKI [46]) and flavin destructase (BluB, PDB 2ISJ [40]) are shown in gray. The variable active site regions are illustrated in green for IYD, cyan for BluB, magenta for FRP and yellow for NfsB. For simplicity, the C-terminal extension (~ 50 residues) of FRP is omitted and the carbon atoms of FMN of are shown in gray.

Substrate specificity is determined by the active site lid of IYD

I-Tyr stabilizes closure of IYD’s active site lid through an extensive series of interactions with the protein and FMN (Figure 1A). A suggestion of hydrogen bonding between the phenolic oxygen of I-Tyr and both the 2'-hydroxyl group of FMN and a backbone N-H described previously help to rationalize the high selectivity for binding halotyrosines (X-Tyr) versus the parent Tyr [31]. Halogen bonding had the potential to differentiate these ligands but no evidence for this has been obtained to date [29, 44]. All other functional groups are common to both X-Tyr and Tyr and yet X-Tyr binds with Kd values on the order of 1.0 – 0.1 µM and Tyr binds so weakly that only a lower estimate of its Kd (>140 µM) can be determined due to its limited solubility [32, 45]. The pH dependence of I2-Tyr binding indicates that the phenolate form of the ligand preferentially associates with human IYD [31]. Thus, the halogen substituents affect selectivity by lowering the phenol pka and increase the phenolate form under neutral conditions whereas Tyr remains almost exclusively in the protonated form under equivalent conditions The significance of this effect was confirmed by the tight binding of nitrotyrosine (O2N-Tyr, Kd 17 µM) to IYD [36]. The nitro substituent shares little with a halide substituent other than both reduce the phenol pka.

Aromatic stacking between I-Tyr and the isoalloxazine ring of FMN is evident in the co-crystal structures of IYD but does not likely dominant ligand interactions. A co-crystal of 2-iodophenol and IYD from H. hydrossis illustrates that this ligand will bind in an orientation analogous to the aromatic group of I-Tyr [44]. However, 2-iodophenol binding is heterogeneous and electron density is only observed from X-ray diffraction for its oxygen and iodine. This ligand is not capable of inducing closure of the active site lid although its affinty for IYD from H. hydrossis is reduced by only 8-fold in comparison to that of I-Tyr [44]. In contrast, the affinity of 2-iodophenol decreases by more than 15,000-fold relative to I-Tyr for human IYD and in all examples, only the zwitterion of the X-Tyr effectively induces closure of the active site lid [29, 31, 44]. This reorganization of the active site is also important for effective catalysis since the kcat/Km value for 2-iodophenol is 104–105 lower than that for I-Tyr with IYD from either human or H. hydrossis. The residues responsible for recognition of the zwitterion are the same Tyr, Glu and Lys described earlier to query genomic data (Figures 1 and 2). The inability of IYD to recognize thyroid hormone [47] may then originate from the extended distance between its zwitterion and the phenolate component of T4 and T3 relative to that of I-Tyr. Even if the phenolate of the hormones or their iodinated thyroglobulin precursor were to bind similarly to 2-iodophenol, catalysis would still be inefficient due to the lack of lid closure [44]. This selectivity is highly beneficial for Chordata to prevent a futile cycle of iodination and deiodination while simultaneously synthesizing thyroid hormones and salvaging iodide for reuse.

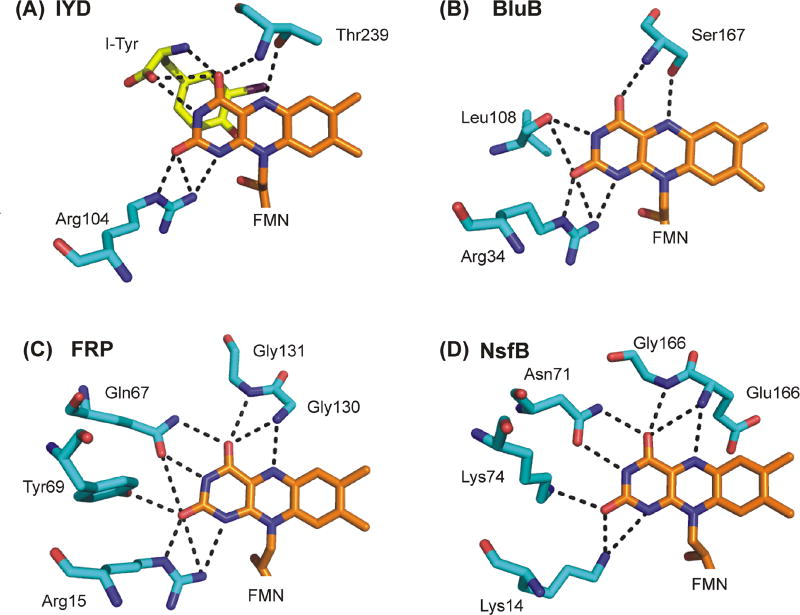

Many of the polar interactions coordinating the isoalloxazine ring of FMN in IYD are provided by substrate rather than protein

Proteins effectively customize the properties of bound flavin to satisfy their specific catalytic and physiological requirements. Both the redox potential and chemical reactivity of flavin can be manipulated by the surrounding environment through possible π-stacking, hydrogen bonding and electrostatic coordination [48–50]. This is primarily established by the polypeptide side chains surrounding the isoalloxazine ring of flavin except in the case of IYD for which substrate provides stacking and the majority of polar contacts. Thus, the specificity of IYD is also related to the ability of substrate to coordinate with the isoalloxazine of FMN. The polypeptide of IYD supports a number of contacts to the phosphoribose component of FMN but in the absence of substrate contributes only one polar contact to the isoalloxazine system through interactions of an Arg to its N1 and C2 carbonyl groups (Figure 6). The significance of this interaction has not yet been explored but is common throughout much of the nitro-FMN reductase superfamily (Arg or Lys) as illustrated in Figure 6 for IYD, flavin destructase BluB, flavin reductase FRP, and nitro-reductase NfsB. A hydrogen bond between a Thr and the N5 of the isoalloxazine system is also evident in IYD but this forms only after substrate coordination and active site lid closure. The significance of this hydrogen bond is discussed below in the section on the catalytic mechanism. The remaining interactions at the N3 and C4 carbonyl of the isoalloxazine are established by the substrate zwitterion bound to IYD. Similar interactions within FRP, NfsB and BluB are created by protein side chains.

Figure 6.

Polar coordination to the isoalloxazine ring of FMN in enzymes of the nitro-FMN reductase superfamily. Carbons of the protein side chains and FMN are illustrated in cyan and orange, respectively. Carbons of I-Tyr are illustrated in yellow. Coordination is illustrated for (A) IYD (PDB 4TTC [31]), (B) flavin destructase BluB (PDB 2ISJ [40]), (C)

IV. The Catalytic Function of IYD

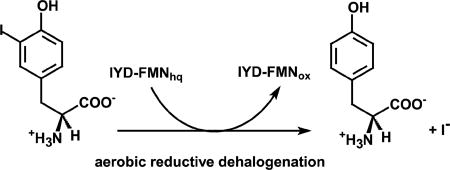

IYD was first detected by its ability to promote deiodination of I-Tyr and I2-Tyr in mammalian thyroid as described in the introduction. The physiological contribution of this reaction to iodide homeostasis was soon recognized when certain forms of hypothyroidism were caused by deficiencies in IYD [10, 11]. Data on substrate selectivity began to emerge after iodohistidine and T4 were shown early to be inert to catalysis [51]. Other analogues such as dibromotyrosine and nitrotyrosine (O2N-Tyr) were examined as inhibitors of IYD and could not be easily checked for turnover since the only assay available relied on the release of a radioactive halide [52]. One laboratory had access to radioactive [82Br]-bromine and was first to report an IYD-dependent debromination of bromotyrosine (Br-Tyr) [8]. More recently, this activity was confirmed by the ability of Br-Tyr to discharge reducing equivalents from IYD containing reduced flavin (FMNhq) and by detecting the product Tyr by reverse-phase (C-18) HPLC [32, 45, 53]. These same methods also revealed the ability of IYD to promote dechlorination of chlorotyrosine (Cl-Tyr) and its inability to promote defluorination of fluorotyrosine (F-Tyr). Both rapid kinetics and steady-state turnover suggest that IYD is equally proficient at deiodination and debromination. Dechlorination of Cl-Tyr is between 4- and 20-fold slower although I-Tyr, Br-Tyr and Cl-Tyr bind to IYD containing oxidized FMN (FMNox) with approximately equal affinity. F-Tyr binds with an affinity that is between 6- to 14-fold weaker than that of I-Tyr [44, 45].

Turnover of IYD requires a substrate containing more than a simple halophenol even though this component represents the minimal chemical unit required for the mechanism of dehalogenation. A series of halophenols bind to H. hydrossis IYD relatively strongly and 4-cyano-2-iodophenol binds with an affinity as great as I-Tyr [44]. Nevertheless, deiodination of 4-cyano-2-iodophenol is not detectable and demonstrates that active site binding is no guarantee of turnover. IYD also exhibits no vestigial or promiscuous activities expressed by other members of its superfamily. Although O2N-Tyr binds to H. hydrossis IYD with an affinity only 5.6-fold weaker than I-Tyr, little nitroreductase activity was evident [36]. O2N-Tyr was only capable of partially oxidizing FMHhq in IYD to form its neutral semiquinone (FMNsq). Some consumption of O2N-Tyr was noted in this case but its origins remains unknown [36]. A similar partial oxidation of FMNhq to FMNsq was evident after addition of O2N-Tyr to human IYD but no consumption of O2N-Tyr was observed in this example [54]. The lack of nitro group reduction was not particularly surprising since nitroreductases seem to promote reduction through hydride transfer [55, 56] whereas IYD promotes reduction through single electron transfers [31, 36, 54]. The ability of the flavin destructase BluB to activate molecular oxygen suggests its ability to promote single electron transfer from its flavin but this enzyme neither promotes a detectable level of I2-Tyr deiodination nor does IYD promote a detectable level of flavin destructase activity [28].

V. Biological Function of IYD

The role of IYD in iodide salvage for thyroid hormone biosynthesis is most obvious but the debromination and dechlorination activities of IYD may also be relevant in mammals. Br-Tyr and Cl-Tyr are formed after stimulation of the innate immune system of mammals and have been correlated to lung disease and asthma in humans [57–59]. These additional halotyrosines are also likely metabolized in vivo through reductive dehalogenation by IYD expressed in the liver and kidney [57, 60]. The natural substrates for IYD expressed in organisms beyond the phylum Chordata are not as apparent although I-Tyr has been predicted to form in a number of organisms lacking the thyroid regulatory system [35, 61]. No information is available on the requirement of iodide for Drosophila and yet the mRNA of its gene for IYD has been detected [62]. However, Drosophila IYD also dehalogenates Br-Tyr and Cl-Tyr [32]. Bromide was recently identified as a micronutrient of Drosophila and found necessary for sulfilimine-based polymerization of collagen IV [63]. Generation of hypobromous acid during this polymerization could likely brominate tyrosyl side chains in proteins that may ultimately yield Br-Tyr. Likewise, halogenated tyrosines are found in invertebrate scleroproteins and also associated with hardening of certain structural tissues [64–66]. A number of marine natural products contain bromotyrosine derivatives [67, 68] and halogenated phenols form spontaneously as a component of disinfection byproducts created during sterilization of municipal drinking water [69, 70]. However, the contribution of IYD to the metabolism of these compounds is not known particularly since IYD is highly selective for X-Tyr and not generally active with halophenols [44].

Iodide uptake in sea urchins seems to be a hydrogen peroxide-dependent process [71] and the combination of iodide and hydrogen peroxide may be sufficient to iodinate Tyr and tyrosyl residues within proteins. A dehalogenase such as IYD may then be necessary to recover iodide or detoxify the ultimate release of I-Tyr. At least for Drosophila, I-Tyr is toxic due to its inhibition of dopamine biosynthesis [72]. IYD could also potentially contribute to natural product biosynthesis in analogy to the reductive dehalogenase from a marine bacteria that catalyzes debromination of tetrabromopyrrole along the path to generate pentabromopseudilin [73]. Perhaps most puzzling is the purported role of an IYD homolog entitled SUP-18 in C. elegans [74]. This protein is linked to the regulation of a potassium channel in muscle cells. Its ability to promote dehalogenation remains to be investigated and some deviations from the signature residues are evident. The conserved Tyr and Glu in the active site lid are present as well as some of the common structural residues such as Trp, Thr, Pro and Tyr (Figures 1 and 2). However, the conserved Lys in the lid region is replaced by Arg. Additionally, a Ser replaces the highly conserved Thr that is responsible for the side chain hydrogen bond to the N5 position of flavin. None of these changes alone necessarily exclude its possible function as a reductive dehalogenase in vivo and further studies will be needed to identify its full catalytic activity and biological function in the life of C. elegans as well as other organisms outside of the phylum Chordata.

VI. Catalytic Mechanism of IYD

Early precedence for the mechanism of IYD consistently suggested a polar (simultaneous two electron transfer) mechanism [20]. I-Tyr was notably stable to many one electron-donating reductants such as sulfite, metabisulfite, ferrocyanide and the very strong reducing agent dithionite [17]. In contrast, cysteine alone was observed to dehalogenate I2-Tyr although high temperature was necessary [75]. Later, the enzyme tetrachlorohydroquinone dehalogenase was shown to catalyze an efficient reductive chlorination through participation of an active site Cys and stabilization of a non-aromatic substrate tautomer of enhanced electrophilicity [76, 77]. The enzyme ID that is responsible for reductive dehalogenation of thyroid hormones contains an active site selenocysteine rather than a flavin and was also considered at first to act through a mechanism similar to tetrachlorohydroquinone dehalogenase [78–80]. However, more recent model studies suggest the potential for deiodination promoted by halogen and chalcogen bonding without loss of aromaticity [81, 82]. This later process is particularly appealing since it can be applied to dehalogenation of both the inner (phenoxy) and outer (phenol) rings of T4 (Scheme 1) [6]. An initial proposal of a polar mechanism for IYD based on Cys was also refuted after a mutant lacking all native Cys retained catalytic activity [26].

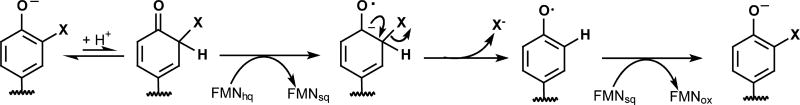

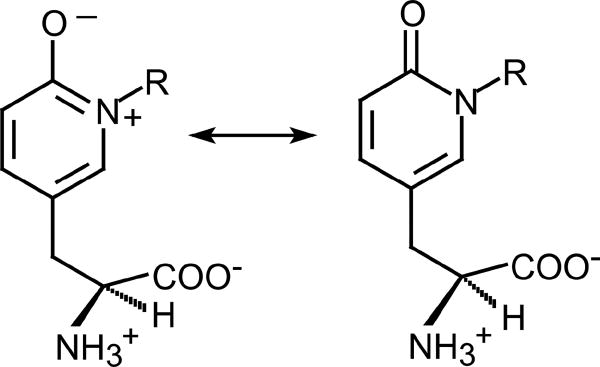

All recent data support an alternative mechanism for IYD that involves single electron transfer from the reduced hydroquinone form of FMN (FMNhq) as summarized in Scheme 2. The phenolate form of X-Tyr is expected to bind preferentially to IYD based on the substituent and pH effects as mentioned above [31, 45]. Coordination of the phenolate to two hydrogen bond donors helps to rationalize this selectivity although stabilization of an electron rich form of the substrate is counter intuitive to the objective of donating additional electrons into the substrate [31]. However, subsequent protonation of the phenolate at its α-carbon that is substituted with the halogen creates a highly electrophilic system. Loss of aromaticity may be compensated by weakening of the C-X bond in an aryl to allylic-like derivative. For example, scission of an aryl C-I bond requires 65 kcal/mol whereas scission of an aliphatic C-I bond in an allylic system requires only 41 kcal/mol [83]. The proposed keto form of the substrate has not yet been observed nor is a proton donor apparent from the co-crystal of human IYD and I-Tyr [31]. However, a pyridone-containing derivative of tyrosine that mimics the keto rather than aromatic enol form is a potent competitive inhibitor of IYD with a Ki of 24 nM (Scheme 3) [20].

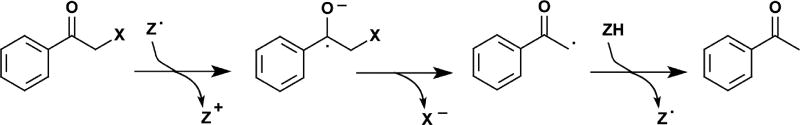

Scheme 2.

Proposed mechanism of dehalogenation involving successive one electron transfers by FMN.

Scheme 3.

A pyridone-based derivative of Tyr mimics the keto form of substrates for IYD.

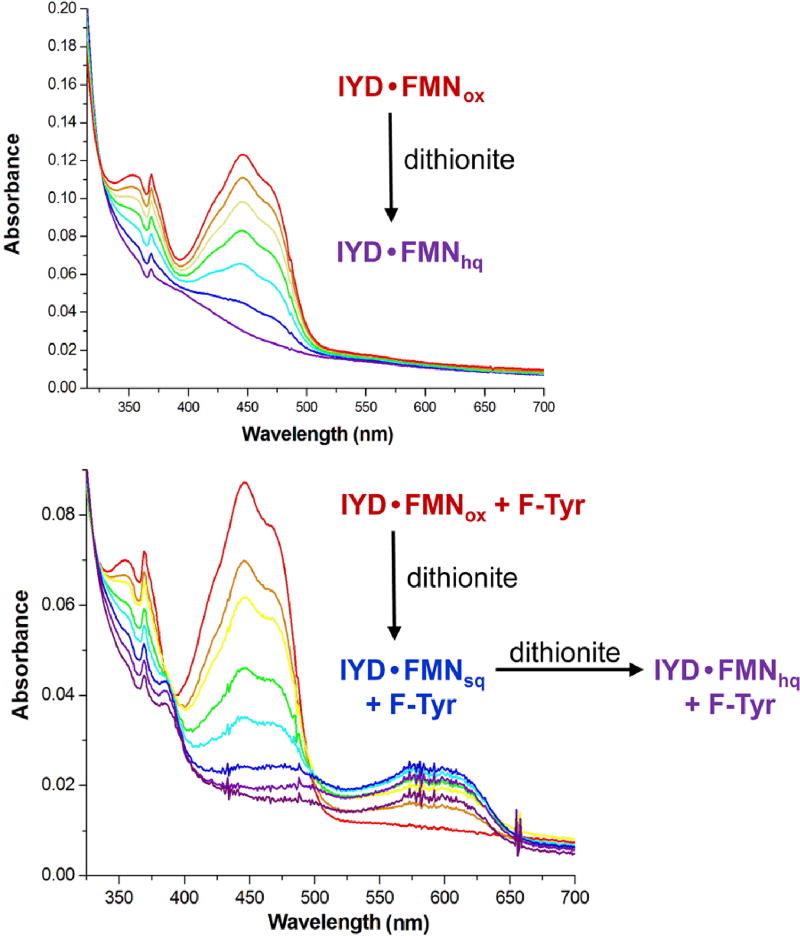

The protonated intermediate is equivalent to an α-halomethyl ketone that is known to undergo reductive dehalogenation through a ketyl anion radical in the presence of one electron reductants (Scheme 4) [84]. A resonance stabilized ketyl anion radical could also form during IYD turnover after electron donation from FMNhq to form a transient FMNsq (Scheme 2). Halide elimination from the radical intermediate would form a relatively stable phenoxy radical that could then accept a final electron from FMNsq to regenerate FMNox and release Tyr. To promote this mechanism, IYD might have been expected to stabilize FMNsq during redox titration but no such result was observed. Instead, the properties of the flavin mimicked free flavin in solution (Figure 7) [31]. This observation is consistent with the dearth of interactions between the protein and the isoalloxazine ring of FMN that is apparent in the crystal structures of IYD lacking substrate [29, 31, 44]. However, a more accurate characterization of the flavin’s properties during catalysis would be in the presence of substrate since this templates closure of the active site lid. In this case, substrate would also induce turnover and likely obscure the transient induction of properties required for efficient catalysis. As an alternative, F-Tyr was expected to mimic the binding of X-Tyr but remain inert to catalysis. Titration of IYD with dithionite or xanthine oxidase and xanthine in the presence of F-Tyr does indeed produce a spectral intermediate with a long wavelength absorption (~ 530 – 640 nm, Figure 7) that is characteristic of the neutral FMNsq [31].

Scheme 4.

One electron donors promote reductive dehalogenation of α-halo ketones [84].

Figure 7.

Redox titration of IYD in the absence and presence of an inert substrate analog F-Tyr [31].

Introduction of F-Tyr into the active site of IYD is expected to dramatically change the environment surrounding FMN (Figures 1, 4 and 6). The zwitterion of F-Tyr should coordinate directly to the pyrimidine portion of the isoalloxazine ring and the phenol group of F-Tyr should stack directly over the flavin in analogy to the orientation observed in the co-crystal structures of I-Tyr and IYD containing FMNox. Closure of the active site lid also induces a shift of a Thr side chain by almost 2 Å into a position for donating a hydrogen bond to the N5 position of FMN [31]. The environment surrounding this N5 position is known to exert a particularly strong influence on the overall chemistry of this cofactor [48]. Mutation of this Thr to Ala abolished the stabilization of the FMNsq intermediate afforded by F-Tyr as evident by a lack of its accumulation during redox titration [36]. This result is not likely due to a loss of affinity for F-Tyr since the Kd for I2-Tyr and O2N-Tyr did not increase by mutation of the Thr to Ala. Interestingly, the mutant also did not preclude deiodination of I2-Tyr as might have been expected based on the alleged importance of FMNsq in catalysis. The kcat/Km value for the Ala mutant decreased by only 15-fold [36]. This is similar to the 30-fold decrease for a comparable Ser to Gly mutation in the flavin destructase BluB that may also stabilize a FMNsq intermediate through hydrogen bonding between the FMN N5 and a side chain hydroxyl group [40]. For IYD, a backbone hydrogen bond may still be available for the FMN N5 based on the distance of 3.4 Å in the parent enzyme containing FMNox and I-Tyr [31]. Thus, the side chain hydrogen bond to FMN N5 is significant but not imperative for stabilizing FMNsq. Loss of this interaction may suppress accumulation and detection of FMNsq but does not preclude its transient formation during catalysis. Single electron transfer is still the favored mechanism of dehalogenation since substitution of FMN with 5-deazaFMN decreases the kcat of native IYD by greater than 105-fold [54]. This deazaFMN is well known to support the two electron chemistry of FMN but incapable of participating in its one electron chemistry [85, 86].

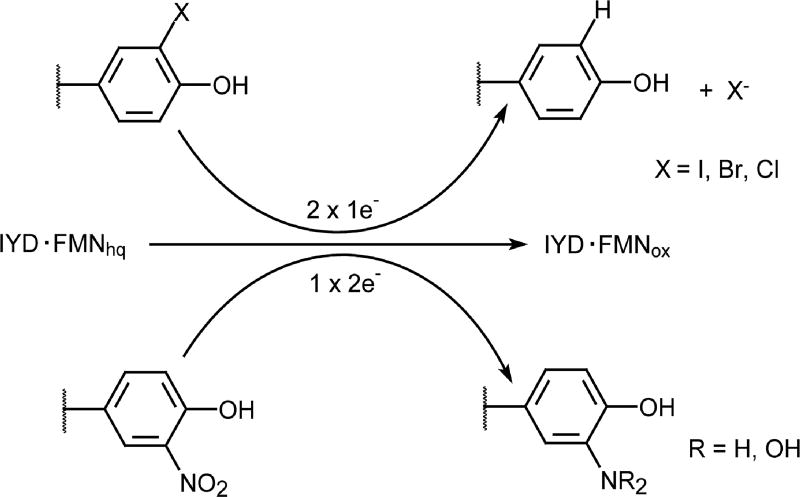

The ability of IYD and likely BluB to promote one electron transfer mechanisms are unusual in the nitro-FMN reductase superfamily that is primarily known to promote two electron transfer mechanisms. Nitroreductases even appear to actively suppress FMNsq formation [55, 56]. A survey of a few representatives of this superfamily reveals a correlation with the nature of hydrogen bonding to the N5 position of FMN (Table 1). Hydrogen bonding between this position and a side chain hydroxyl group seems indicative of reduction through one electron chemistry and analogous hydrogen bonding to an amide backbone N-H indicates reduction by two electron chemistry. This is rather simplistic but begged the question of whether catalytic activities could be switched by changing only the single residue responsible for this hydrogen bonding. The remarkable influence of this residue was confirmed by a Thr to Ala mutant of IYD. As mentioned, this mutant IYD expressed a diminished capacity for promoting reductive dehalogenation and concurrently demonstrated a greatly enhanced capacity to promote reduction of O2N-Tyr to hydroxylaminotyrosine as typical for turnover of a nitroreductase (Scheme 5) [36]. Thus, a very minimal change in sequence has the potential to create a significant change in activity and suggests that evolution of these enzyme families required only a slight variation to start them on their unique paths of development. Consistent with the dichotomy of dehalogenase versus nitroreductase and one versus two electron transfer, reconstitution of IYD with 5-deazaFMN also acts as a nitroreductase and promotes full reduction of O2N-Tyr to H2N-Tyr [54].

Table 1.

Hydrogen bonding between proteins and the N5 position of their bound flavin cofactor in representatives of the nitro-FMN reductase superfamily.

| protein | PDB code | protein function |

H-Bond To FMN N5 |

electron transfer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IYD | 4TTC | dehalogenase | side chain OH | 2 × 1e− |

| BluB | 2ISJ | destructase | side chain OH | 2 × 1e− |

|

| ||||

| NTR | 1DS7 | nitroreductase | backbone NH | 1 × 2e− |

| Frase I | 1VFR | flavin reductase | backbone NH | 1 × 2e− |

| FRP | 2BKJ | flavin reductase | backbone NH | 1 × 2e− |

| NOX | 1NOX | NADH oxidase | backbone NH | 1 × 2e− |

| NfsA | 1F5V | nitroreductase | backbone NH | 1 × 2e− |

| RdxA | 2QDL | nitroreductase | backbone NH | 1 × 2e− |

Scheme 5.

The redox characteristics of FMN control dehalogenation versus nitroaromatic reduction [36].

VII. Conclusion

Many surprises were encountered during investigations on the substrate specificity, distribution and mechanism of IYD. This enzyme is highly selective for halotyrosines and capable of catalyzing deiodination, debromination and dechlorination. Early expectations assumed that IYD might have been restricted to Chordata since only this phylum is known to require iodide salvage to sustain thyroid hormone biosynthesis. On the contrary, the gene for IYD is found in most metazoa and a number of eubacteria and archaea. The specificity of X-Tyr persists from human to archaea but the biological function likely differs since iodide may not be required for unicellular organisms. In these cases, Br-Tyr or Cl-Tyr may be most physiologically relevant. Although reductive dehalogenation under aerobic conditions is relatively rare in nature, its evolutionary development is now easily envisioned. Only a single amino acid substitution is needed to convert a IYD to a nitroreductase. This key residue helps to control the one and two electron chemistry of flavin by interaction with its N5 position. We look forward to many more surprises as investigations continue on mechanistic and functional properties of IYD and its homologs.

Acknowledgments

We thank all of the members of the Rokita laboratory and collaborators who have contributed to investigations on iodotyrosine deiodinase. The investigations summarized in this review would not be possible without their dedication, perseverance and creativity.

Funding: Research on iodotyrosine deiodinase by the Rokita laboratory was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (DK045783, DK084186 and AI1195400).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Liu Y-Y, Brent GA. Thyroid hormone crosstalk with nuclear receptor signaling in metabolic regulation. Trends Endocrin. Met. 2009;21:166–173. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williams GR. Neurodevelopmental and neurophysiological actions of thyroid hormone. J. Neuroendocrin. 2008;20:784–794. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2008.01733.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bianco AC, Salvatore D, Gereben B, Berry MJ, Larsen PR. Biochemistry, cellular and molecular biology and physiological roles of the iodothyronine selenodeiodinases. Endocrine Rev. 2002;23:38–89. doi: 10.1210/edrv.23.1.0455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.St. Germain DL, Galton VA, Hernandez A. Defining the roles of the iodothyronine deiodinases: current concepts and challenges. Endocrinol. 2009;150:1097–1107. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-1588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schweizer U, Schlicker C, Braun D, Kohrle J, Steegborn C. Crystal structure of mammalian selenocysteine-dependent iodothyronine deiodinase suggests a peroxiredoxin-like catalytic mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. (USA) 2014;111:10526–10531. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1323873111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schweizer U, Steegborn C. New insights into the structure and mechanism of iodothyronine deiodinases. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2015;55:R37–R52. doi: 10.1530/JME-15-0156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hartmann N. Über den Abbau von Dijotyrosin im Gewebe. Z. Physiol. Chem. 1950;285:1–17. doi: 10.1515/bchm2.1950.285.1-3.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roche J, Michel O, Michel R, Gorbman A, Lissitzky S. Sur la deshalogénation enzymatique des iodotyrosines par le corps thyroïde et sur son rôle physiologique. II. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1953;12:570–576. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(53)90189-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeGroot LJ, Laarse PR, Refetoff S, Stanbury JB. The Thyroid and Its Diseases. 5. Wiley & Sons; New York: 1984. Ch. 1. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stanbury JB, Meijer JWA, Kassenaar AAH. The metabolism of iodotyrosines. II. The metabolism of mono and diiodotyrosine in certain patients with familial goiter. J. Clin. Endocinol. Met. 1956;16:848–868. doi: 10.1210/jcem-16-7-848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Querido A, Stanbury JB, Kassenaar AAH, Meijer JWA. The metabolism of iodotyrosines. III. Diiodotyrosine deshalogenating activity of human thyroid tissue. J. Clin. Endocrinol. and Metab. 1956;16:1096–1101. doi: 10.1210/jcem-16-8-1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moreno JC, Klootwijk W, van Toor H, Pinto G, D'Alessandro M, Lèger A, Goudie D, Polak M, Grüters A, Visser TJ. Mutations in the iodotryosine deiodinase gene and hypothyroidism. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008;358:1811–1818. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Afink G, Kulik W, Overmars H, de Randamie J, Veenboer T, van Cruchten A, Craen M, Ris-Stalpers C. Molecular characterization of iodotyrosine dehalogenase deficiency in patients with hypothyroidism. J. Clin. Endocinol. Metab. 2008;93:4894–4901. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-0865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stanbury JB. The requirement of monoiodotyrosine deiodinase for triphosphopyridine nucleotide. J. Biol. Chem. 1957;228:801–811. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stanbury JB, Morris ML. Deiodination of diiodotyrosine by cell-free systems. J. Biol. Chem. 1958;233:106–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosenberg IN, Goswami A. Purification and characterization of a flavoprotein from bovine thyroid with iodotyrosine deiodinase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 1979;254:12318–12325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goswami A, Rosenberg IN. Studies on a soluble thyroid iodotyrosine deiodinase: activation by NADPH and electron carriers. Endocrinol. 1977;101:331–341. doi: 10.1210/endo-101-2-331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goswami A, Rosenberg IN. Ferredoxin and ferredoxin reductase activities in bovine thyroid. Possible relationship to iodotyrosine deiodinase. J. Biol. Chem. 1981;256:893–899. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosenberg IN, Goswami A. Iodotyrosine deiodinase from bovine thyroid. Methods Enzymol. 1984;107:488–500. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(84)07033-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kunishima M, Friedman JE, Rokita SE. Transition-state stabilization by a mammalian reductive dehalogenase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:4722–4723. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Valverde-R C, Orozco A, Becerra A, Jeziorski MC, Villalobos P, Solis-S JC. Halometabolites and cellular dehalogenase systems: an evolutionary perspective. Int. Rev. Cytology. 2004;234:143–199. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7696(04)34004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moreno JC. Identification of novel genes involved in congenital hypothyroidism using serial analysis of gene expression. Horm. Res. 2003;3:96–102. doi: 10.1159/000074509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gnidehou S, Caillou B, Talbot M, Ohayon R, Kaniewski J, Noël-Hudson M-S, Morand S, Agnangji D, Sezan A, Courtin F, Virion A, Dupuy C. Iodotyrosine dehalogenase 1 (DEHAL1) is a transmembrane protein involved in the recycling of iodide close to the thyroglobulin iodination site. FASEB J. 2004;18:1574–1576. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2023fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Friedman JE, Watson JA, Jr, Lam DW-H, Rokita SE. Iodotyrosine deiodinase is the first mammalian member of the NADH oxidase / flavin reductase superfamily. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:2812–2819. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510365200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rokita SE, Adler JM, McTamney PM, Watson JA., Jr Efficient use and recycling of the micronutrient iodide in mammals. Biochimie. 2010;92:1227–1235. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2010.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Watson JA, Jr, McTamney PM, Adler JM, Rokita SE. The flavoprotein iodotyrosine deiodinase functions without cysteine residues. ChemBioChem. 2008;9:504–506. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200700562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Buss JM, McTamney PM, Rokita SE. Expression of a soluble form of iodotyrosine deiodinase for active site characterization by engineering the native membrane protein from Mus musculus. Protein. Sci. 2012;21:351–361. doi: 10.1002/pro.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Phatarphekar A, Buss JM, Rokita SE. Iodotyrosine deiodinase: a unique flavoprotein present in organisms of diverse phyla. Mol. BioSyst. 2014;10:86–92. doi: 10.1039/c3mb70398c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thomas SR, McTamney PM, Adler JM, LaRonde-LeBlanc N, Rokita SE. Crystal structure of iodotyrosine deiodinase, a novel flavoprotein responsible for iodide salvage in thyroid glands. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:19659–19667. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.013458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sievers F, Wilm A, Dineen DG, Gibson TJ, Karplus K, Li W, Lopez R, McWilliam H, Remmert M, Söding J, Thompson JD, Higgins DG. Fast, scalable generation of high-quality protein multiple sequence alignments using Clustal Omega. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2011;7:539. doi: 10.1038/msb.2011.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hu J, Chuenchor W, Rokita SE. A switch between one- and two-electron chemistry of the human flavoprotein iodotyrosine deiodinase is controlled by substrate. J. Biol. Chem. 2015;290:590–600. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.605964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Phatarphekar A, Rokita SE. Functional analysis of iodotyrosine deiodinase from Drosophila melanogaster. Protein. Sci. 2016;25:2187–2195. doi: 10.1002/pro.3044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Phatarphekar A, Ingavat N, Rokita SE. Unpublished observations. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Akiva E, Copp JN, Tokuriki N, Babbitt PC. http://sfld.rbvi.ucsf.edu/django/superfamily/122/

- 35.Crockford SJ. Evolutionary roots of iodine and thyroid hormones in cell-cell signaling. Integr. Comp. Biol. 2009;49:155–166. doi: 10.1093/icb/icp053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mukherjee A, Rokita SE. Single amino acid switch between a flavin-dependent dehalogenase and nitroreductase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:15342–15345. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b07540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Akiva E, Brown S, Almonacid DE, Barber AE, 2nd, Custer AF, Hicks MA, Huang CC, Lauck F, Mashiyama ST, Meng EC, Mischel D, Morris JH, Ojha S, Schnoes AM, Stryke d, Yunes JM, Ferrin TE, Holliday GL, Babbitt PC. The Structure-Function Linkage Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D521–D530. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Crooks GE, Hon G, Chandonia JM, Brenner SE. WebLogo: A sequence logo generator. Genome Res. 2004;14:1188–1190. doi: 10.1101/gr.849004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roldán MD, Pérez-Reinado E, Castillo F, Moreno-Vivián C. Reduction of polynitroaromatic compounds: the bacterial nitroreductases. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2008;32:474–500. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2008.00107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Taga ME, Larsen NA, Howard-Jones AR, Walsh CT, Walker GC. BluB cannibalizes flavin to form the lower ligand of vitamin B12. Nature. 2007;446:449–453. doi: 10.1038/nature05611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tanner JJ, Lei B, Tu SC, Krause KL. Flavin reductase P: structure of a dimeric enzyme that reduces flavin. Biochemistry. 1996;35:13531–13539. doi: 10.1021/bi961400v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Krogh A, Larsson B, von Heijne G, Sonnhammer ELL. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: Application to complete genomes. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;303:567–580. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mondo SJ, Dannebaum RO, Kuo RC, Louie KB, Bewick AJ, LaButti K, Haridas S, Kuo A, Salamov A, Ahrendt SR, Lau R, Bowen BP, Lipzen A, Sullivan W, Andreopoulos BB, Clum A, Lindquist E, Daum C, Northen TR, Kunde-Ramamoorthy G, Schmitz RJ, Gryganskyi A, Culley D, Magnuson J, James TY, O'Malley MA, Stajich JE, Spatafora JW, Visel A, Grigoriev IV. Widespread adenine N6-methylation of active genes in fungi. Nat. Genet. 2017;49:964–968. doi: 10.1038/ng.3859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ingavat N, Kavran JM, Sun Z, Rokita SE. Active site binding is not sufficient for reductive deiodination by iodotyrosine deiodinase. Biochemistry. 2017;56:1130–1139. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.6b01308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McTamney PM, Rokita SE. A mammalian reductive deiodinase has broad power to dehalogenate chlorinated and brominated substrates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:14212–14213. doi: 10.1021/ja906642n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Race PR, Lovering AL, Green RM, Ossor A, White SA, Searle PF, Wrighton CJ, Hyde EI. Structural and mechanistic studies of Escherichia coli nitroreductase with the antibiotic nitrofurazone. Reversed binding orientations in different redox states of the enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:13256–13264. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409652200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Solis-S JC, Villalobos P, Valverde-R C. Comparative kinetic characterization of rat thyroid iodotyrosine dehalogenase and iodothyronine deiodinase type 1. J. Endocrinol. 2004;181:385–392. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1810385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fraaije MW, Mattevi A. Flavoenzymes: diverse catalysts with recurrent features. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2000;25:126–132. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(99)01533-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fagan RL, Palfey BA. Flavin-Dependent Enzymes. In: Begley TP, editor. Ch. 3 in Comprehensive Natural Products II. Elsevier; Oxford: 2010. pp. 37–114. [Google Scholar]

- 50.McDonald CA, Fagan RL, Collard F, Monnier VM, Palfey BA. Oxgen reactivity in flavoenzymes: context matters. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:16809–16811. doi: 10.1021/ja2081873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Matsuzaki S, Suzuki M. Deiodination of iodinated amino acids by pig thyroid microsomes. J. Biochem. (Toyko) 1967;62:746–755. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a128731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Green WL. Inhibition of thyroidal iodotyrosine deiodination by tyrosine analogues. Endocrinol. 1968;83:336–346. doi: 10.1210/endo-83-2-336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bobyk KD, Ballou DP, Rokita SE. Rapid kinetics of dehalogenation promoted by iodotyrosine deiodinase from human thyroid. Biochemistry. 2015;54:4487–4494. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.5b00410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Su Q, Boucher PA, Rokita SE. Conversion of a dehalogenase to a nitroreductase by swapping its flavin cofactor with a 5-deazaflavin analog. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017 doi: 10.1002/anie.201703628. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Haynes CA, Koder RL, Miller A-F, Rodgers DW. Structures of nitroreductase in three states. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:11513–11520. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111334200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Koder RL, Haynes CA, Rodgers ME, Rodgers DW, Miller A-F. Flavin thermodynamics explain the oxygen insensitivity of enteric nitroreductase. Biochemistry. 2002;41:14197–14205. doi: 10.1021/bi025805t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mani AR, Ippolito S, Moreno JC, Visser TJ, Moore KP. The metabolism and dechlorination of chlorotyrosine in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:29114–29121. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704270200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wu W, Samoszuk MK, Comhair SA, Thomassen MJ, Farver CF, Dweik RA, Kavuru MS, Erzurum SC, Hazen SL. Eosinophils generate brominating oxidants in allergen-induced asthma. J. Clin. Invest. 2000;105:1455–1463. doi: 10.1172/JCI9702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Buss IH, Senthilmohan R, Darlow BA, Mogridge N, Kettle AJ, Winterbourn CC. 3-Chlorotyrosine as a marker of protein damage by myeloperoxidase in tracheal aspirates from preterm infants: association with adverse respiratory outcome. Pediatr. Res. 2003;53:455–462. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000050655.25689.CE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mani AR, Moreno JC, Visser TJ, Moore KP. The metabolism and debromination of bromotyrosine in vivo. Free Rad. Biol. Med. 2016;90:243–251. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.11.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Heyland A, Moroz LL. Cross-kingdom hormonal signaling: an insight from thyroid hormone functions in marine larvae. J. Exp. Biol. 2005;208:4355–4361. doi: 10.1242/jeb.01877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Attrill H, Falls K, Goodman JL, Millburn GH, Antonazzo G, Rey AJ, Marygold SJ. FlyBase: establishing a gene group resource for Drosophila melanogaster. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:D786–D792. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.McCall AS, Cummings CF, Bhave G, Vanacore R, Page-McCaw A, Hudson BG. Bromine is an essential trace element for assembly of collagen IV scaffolds in tissue development and architecture. Cell. 2014;157:1380–1392. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hunt S. Halogenated tyrosine derivatives in invertebrate scleroproteins: Isolation and identification. Methods in Enz. 1984;107:413–438. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(84)07029-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hall HG. Hardening of the Sea Urchin fertilization envelope by peroxidase-catalyzed phenolic couping of tyrosines. Cell. 1978;15:343–355. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(78)90003-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Birkedal H, Khan RK, Slack N, Broomell C, Lichtenegger HC, Zok F, Stucky GD, Waite JH. Halogenated veneers: protein cross-linking and halogenation in the jaws of Nereis a marine polychaete worm. ChemBioChem. 2006;7:1392–1399. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200600160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kijjoa A, Watanadilok R, Sonchaeng P, Sawangwong P, Pedro M, Nascimento MSJ, Silva AMS, Eaton G, Herz W. Further halotyrosine derivatives from the maring sponge Suberea aff. praetensa. Z. Naturforsch. C. 2002;57:732–738. doi: 10.1515/znc-2002-7-831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Niemann H, Marmann A, Lin W, Proksch P. Sponge derived bromotyrosines: structural diversity through natural combinatorial chemistry. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2015;10:219–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Coleman WE, Melton RG, Kopfier FC, Barone KA, Aurand TA, Jellison MG. Identification of organic compounds in a mutagenic extract of a surface drinking water by a computerized gas chromatography / mass spectrometry system. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1980;14:576–588. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhai H, Zhang X, Zhu X, Liu J, Ji M. Formation of brominated disinfection by products during chloramination of drinking water: new polar species and overall kinetics. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014;48:2579–2588. doi: 10.1021/es4034765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Miller AEM, Heyland A. Iodine accumulation in sea urchin larvae is dependent on peroxide. J. Exp. Biol. 2013;216:915–926. doi: 10.1242/jeb.077958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Neckameyer WS. Multiple roles for dopamine in Drosophila development. Develop. Biol. 1996;176:209–219. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.El Gamal A, Agarwal V, Rahman I, Moore BS. Enzymatic reductive dehalogenation controls biosynthesis of marine bacterial pyrroles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:13167–13179. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b08512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.de la Cruz IP, Ma L, Horvitz HR. The Caenorhabditis elegans iodotyrosine deiodinase ortholog SUP-18 functions through a conserved channel SC-Box to regulate the muscle two-pore domain potassium channel SUP-9. PLoS Genetics. 2014;10:1004175. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hartmann K, Hartmann N. Untersuchungen zum reaktionsablauf der dejodierung von 3-5-dijod-tyrosin durch cystein. Z. Chem. 1971;11:344–345. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Warner JR, Lawson SL, Copley SD. A mechanistic investigation of the thiol-disulfide exchange step in the reductive dehalogenation catalyzed by tetrachlorohydroquinone dehalogenase. Biochemistry. 2005;44:10360–10368. doi: 10.1021/bi050666b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Warner JR, Copley SD. Pre-steady-state kinetic studies of the reductive dehalogenation catalyzed by tetrachlorohydroquinone dehalogenase. Biochemistry. 2007;46:13211–13222. doi: 10.1021/bi701069n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Vasil'ev AA, Engman L. Iodothyronine deiodinase mimics. Deiodination of o,o'-diiodophenols by selenium and tellurium reagents. J. Org. Chem. 1998;63:3911–3917. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kuiper GGJM, Kester MHA, Peeters RP, Visser TJ. Biochemical mechanisms of thyroid hormone deiodination. Thyroid. 2005;15:787–798. doi: 10.1089/thy.2005.15.787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Goto K, Sonoda D, Shimada K, Sase S, Kawashima T. Modeling of the 5'-deiodination of thyroxine by iodothyronine deiodinase: chemcial corroboration of a selenenyl iodide intermediate. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010;49:545–547. doi: 10.1002/anie.200905796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bayse CA, Rafferty ER. Is halogen bonding the basis for iodothyronine deiodinase activity? Inorg. Chem. 2010;49:5365–5367. doi: 10.1021/ic100711n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Manna D, Mugesh G. Regioselective deiodination of thyroxine by iodothyronine deiodinase mimics: an unusual mechanistic pathway involving cooperative chalcogen and halogen bonding. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:4269–4270. doi: 10.1021/ja210478k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Fox MA, Whitesell JK. Organic Chemistry. 2. Jones and Bartlett Sudbury; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Tanner DD, Chen JJ, Chen L, Luelo C. Fragmentation of substituted acetophenone and halobenzophenone ketyls. Calibration of a mechanistic probe. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113:8074–8081. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hemmerich P, Massey V, Fenner H. Flavin and 5-deazaflavin: a chemical evaluation of ‘modified’ flavoproteins with respect to the mechanisms of redox biocatalysis. FEBS Lett. 1977;84:5–21. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(77)81047-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hersh LB, Walsh C. Preparation, characterization and coenzymic properties of 5-carba-5-deaza and 1-carba-1-deaza analogs of riboflavin, FMN and FAD. Methods Enzymol. 1980;66:277–287. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(80)66469-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]